The Story of Surtsey's Life

An Island Disappears, A Landscape Remains

Rui Ye s2553812

Landscape architecture design exploration: Part 2 (2024-2025)[SEM2]

Norman Villeroux Nikolaos Kourampas

An Island Disappears, A Landscape Remains

Rui Ye s2553812

Landscape architecture design exploration: Part 2 (2024-2025)[SEM2]

Norman Villeroux Nikolaos Kourampas

This portfolio is structured in three chapters, unfolding the story of Surtsey across time and scales:

Chapter 1 – Explore the lost island /1

The portfolio opens with a speculative vision 100 years from now, where visitors arrive by boat to explore a disappearing island. They move between ecological columns and altered landforms, witnessing a site shaped by erosion, memory, and more-than-human collaboration.

Chapter 2 – The story of Surtsey’s Life /9

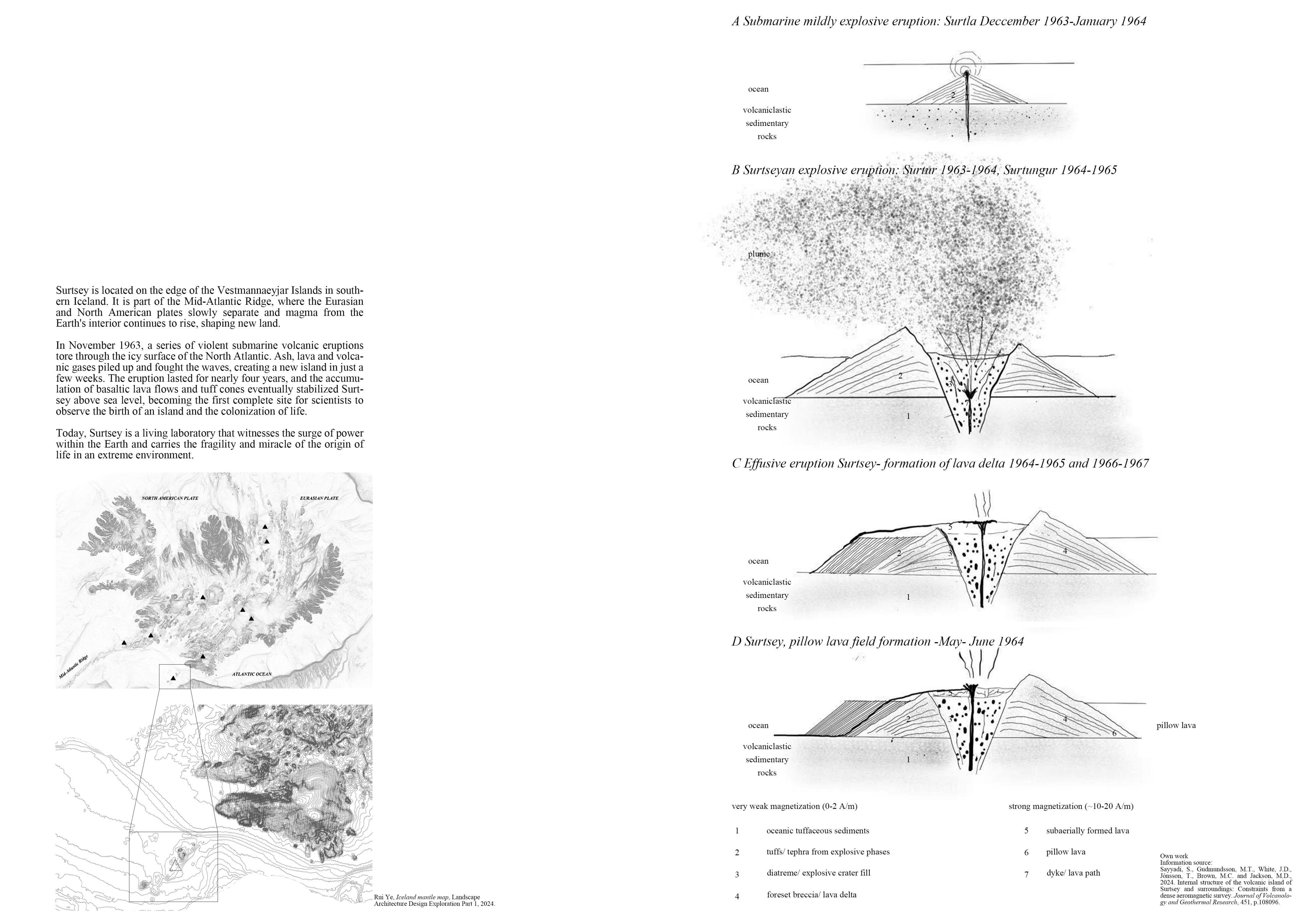

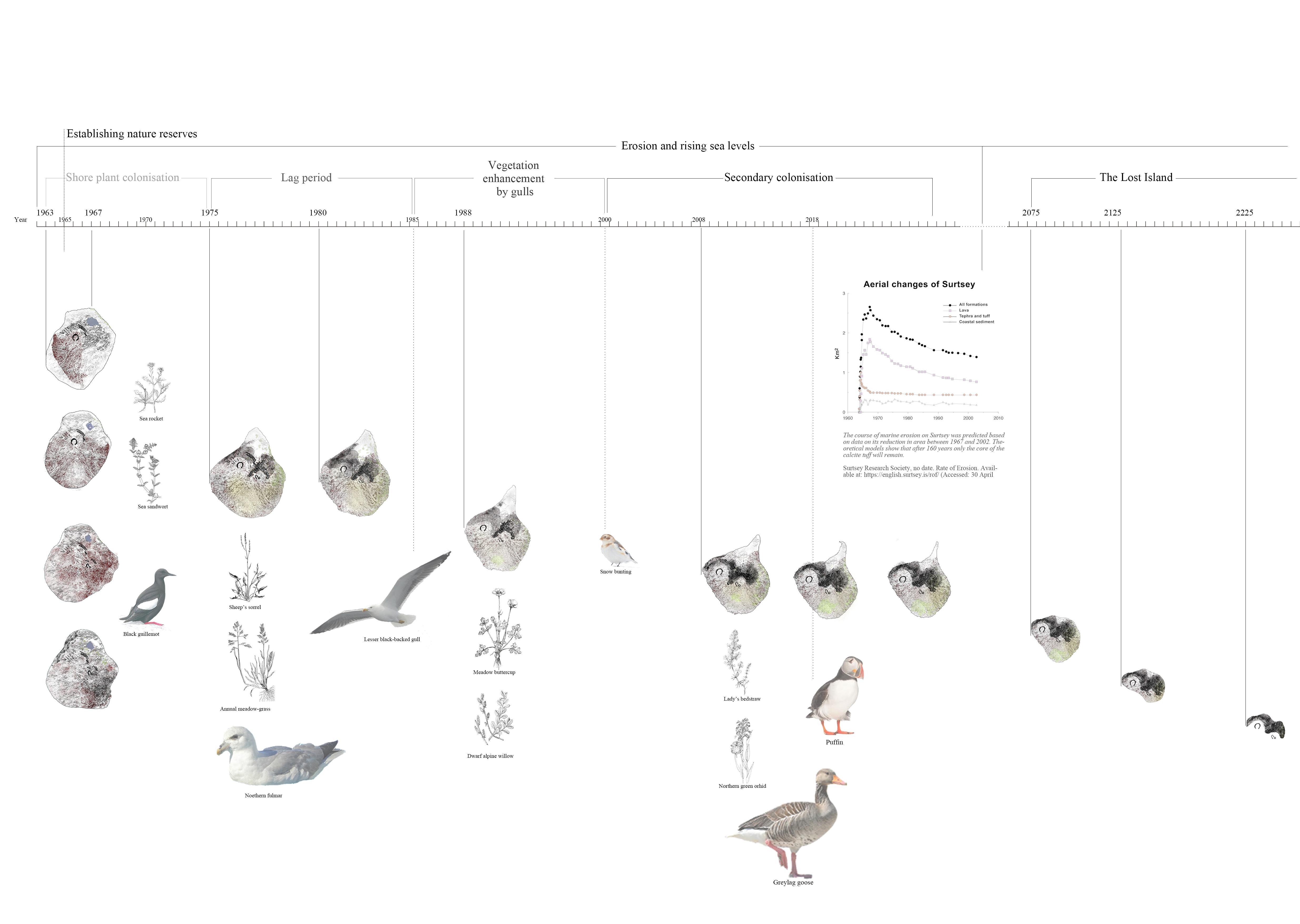

This chapter traces the geological and ecological history of Surtsey, from its volcanic birth in 1963 to its gradual erosion. It analyzes the site’s materials, environmental conditions, and the theories of plant colonization and island ecology that inform the design.

Chapter 3 – Remember Surtsey /31

The final chapter presents the proposal: a series of ecological interventions placed across four key zones of the island. Drawings, diagrams, material explorations and perspective views demonstrate how design becomes a collaborator in the island’s evolving future.

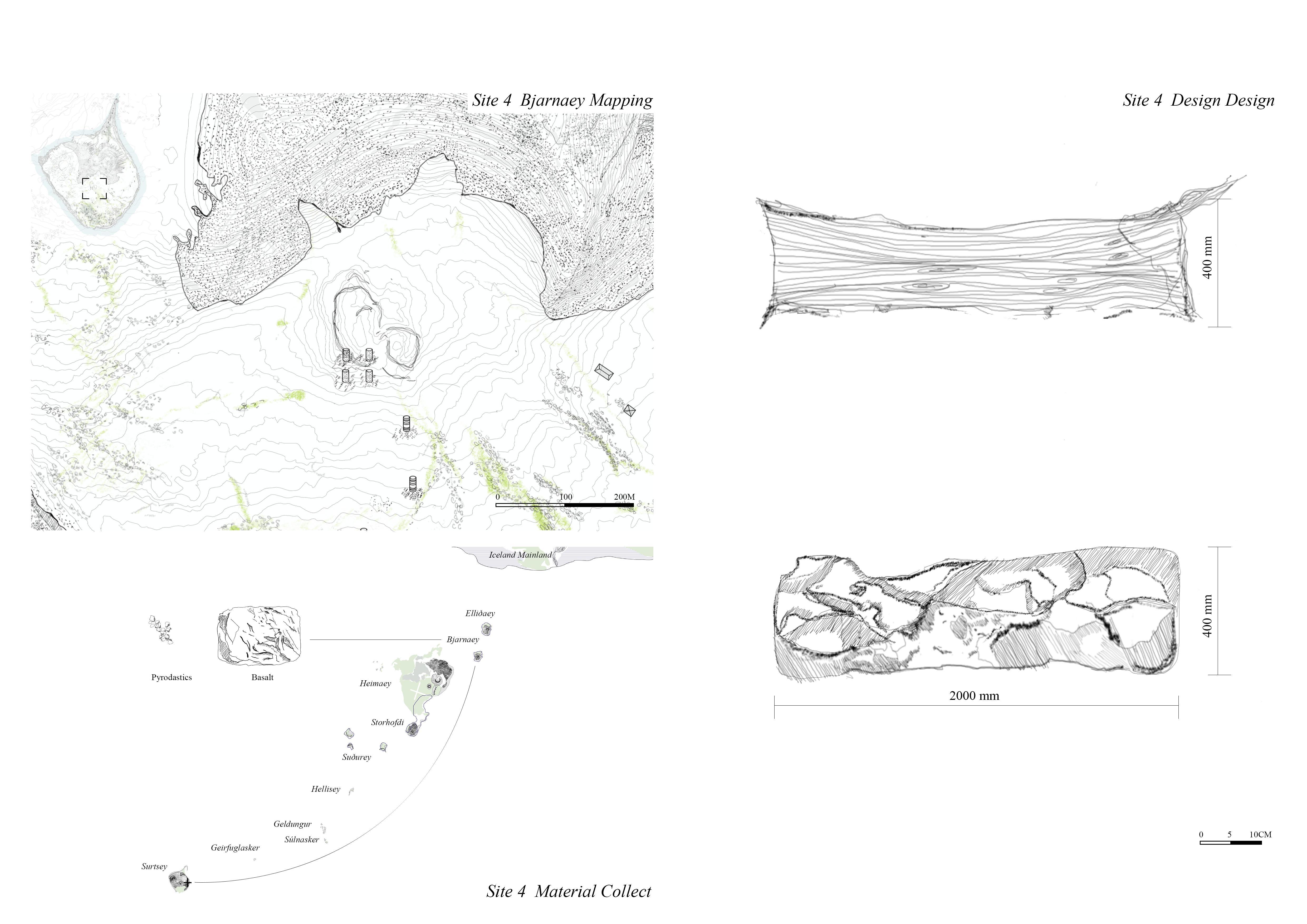

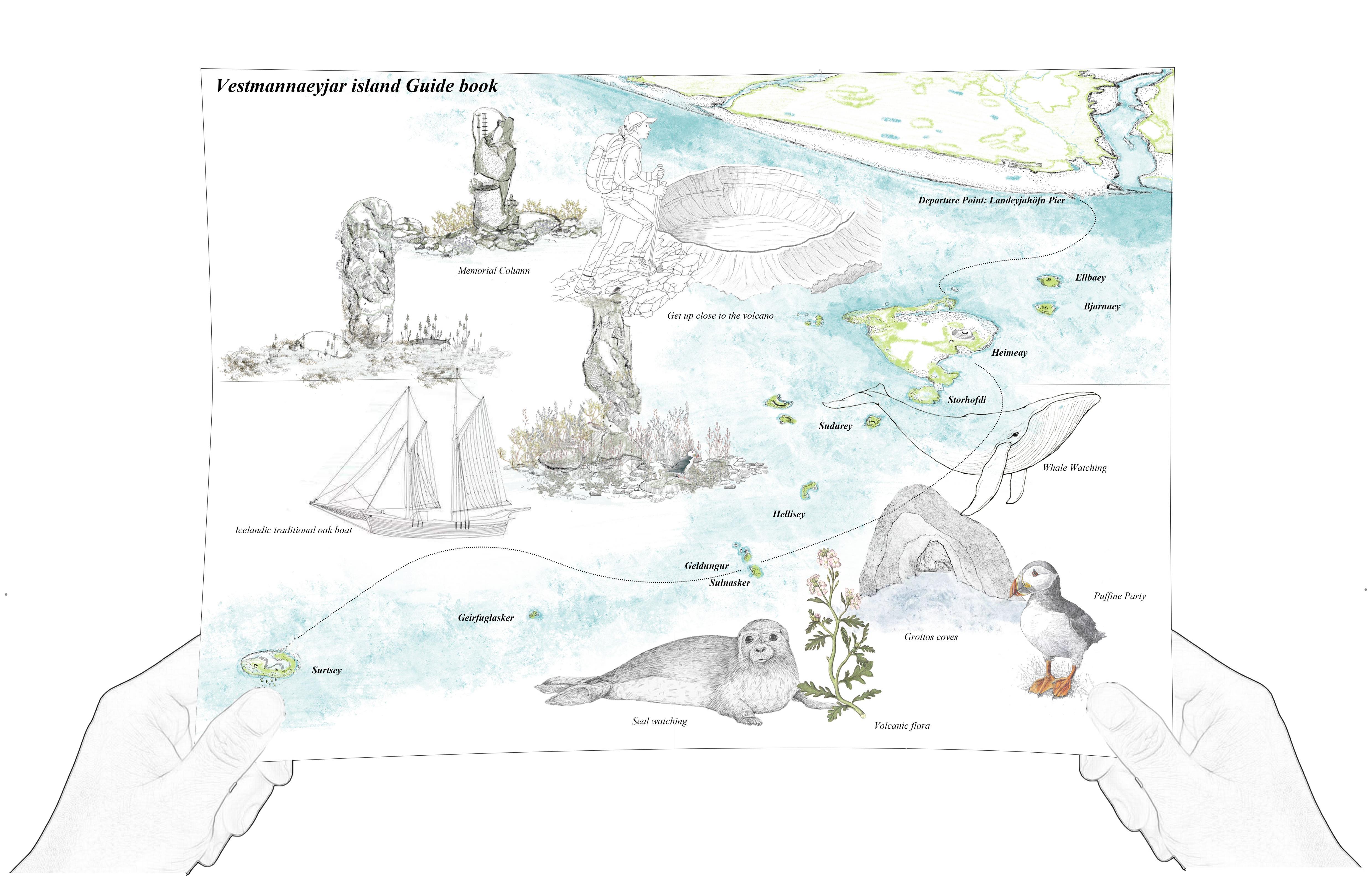

The project is based on Surtsey, a volcanic island that erupted from beneath the sea in 1963, was protected by law the following year and only accessible to scientists, and is now gradually melting into the ocean due to sea erosion and rising sea levels. Surtsey is located in the Vestmannaeyjar Islands in southern Iceland. The active volcanic belt allows Surtsey to witness primitive geological ages and ecological succession. It is both a living ecological experiment and a disappearing landscape.

My interest in dynamic landscapes and ecological succession prompted me to make working models and animated images, and I had a clearer vision for the dynamic life of Surtsey: a design that can both record the natural evolution of the island and become part of the life cycle.

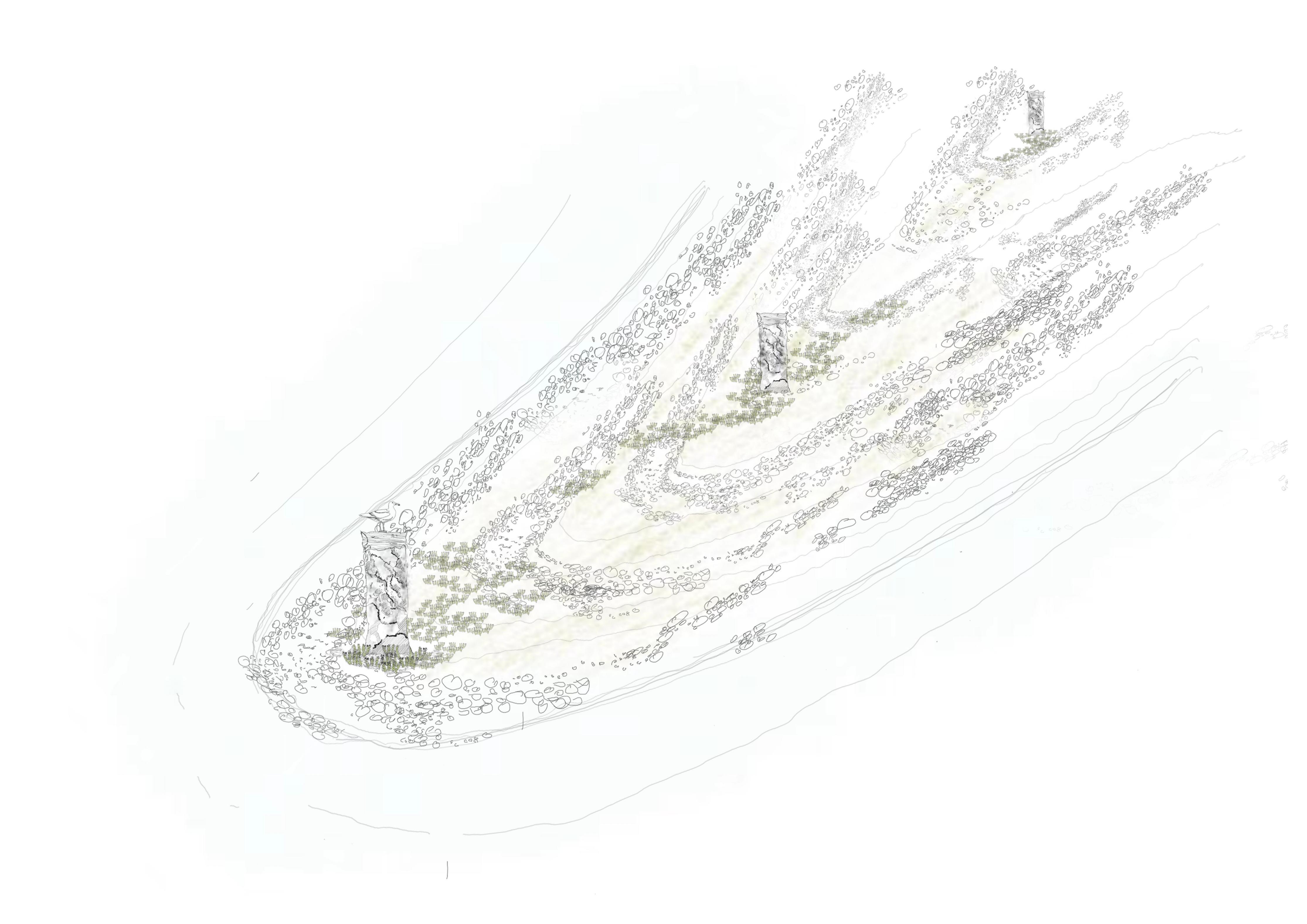

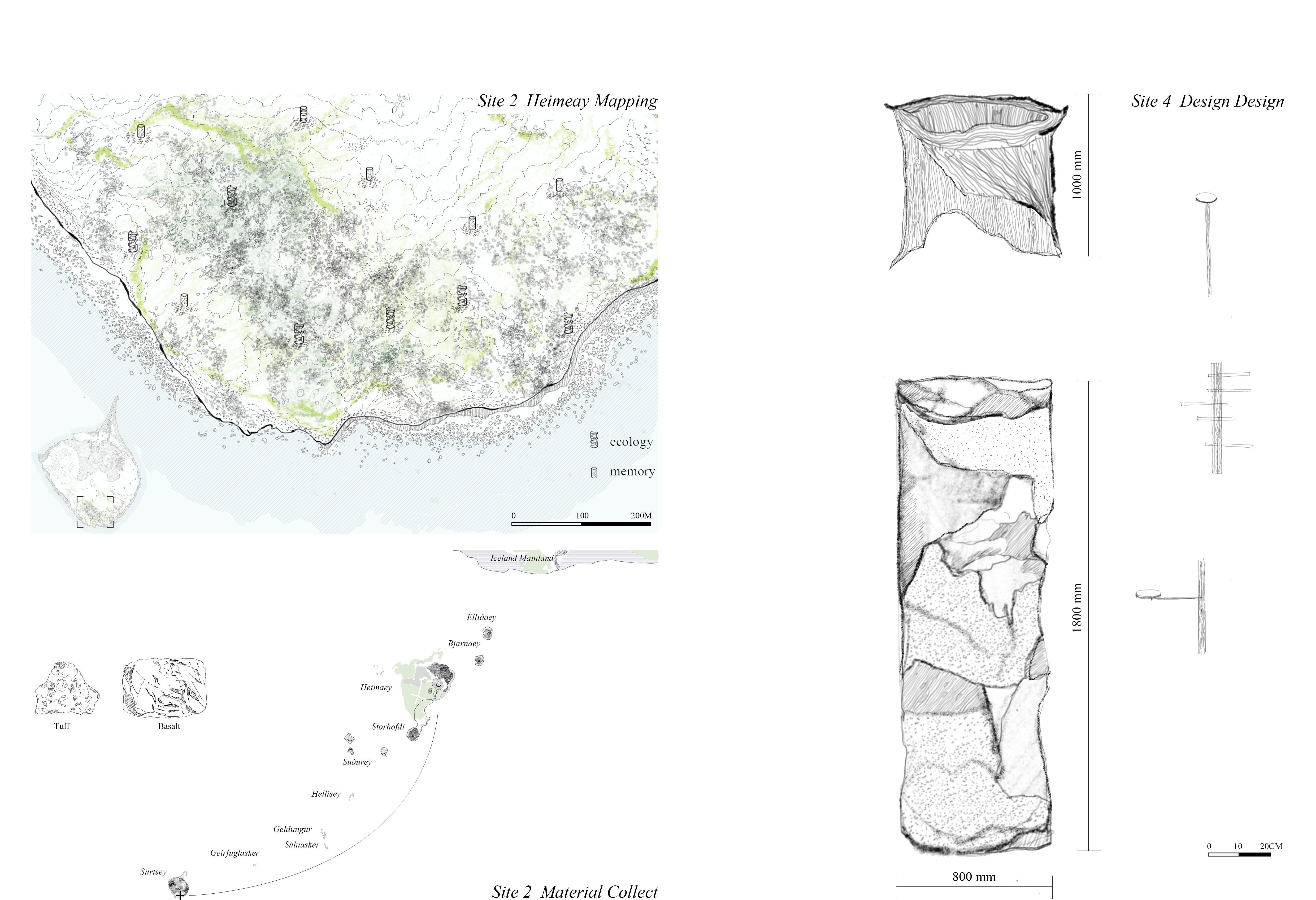

Design is not about resisting extinction, but taking erosion and ecological succession as the core theme. The project is guided by theories of plant colonization and island ecology, and the materials come from various volcanic islands in the Vestmannaeyjar Islands. Each element reflects the geological and ecological memory of other islands. The project uses tuff, basalt, volcanic sediments and driftwood, arranged along the island's northern sand spit, eastern flora, southern nesting area and western crater. It is both an ecological monument and a time marker, breeding mosses, accumulating sediments, decaying, collapsing, and giving birth to new life, becoming part of the island's life cycle.

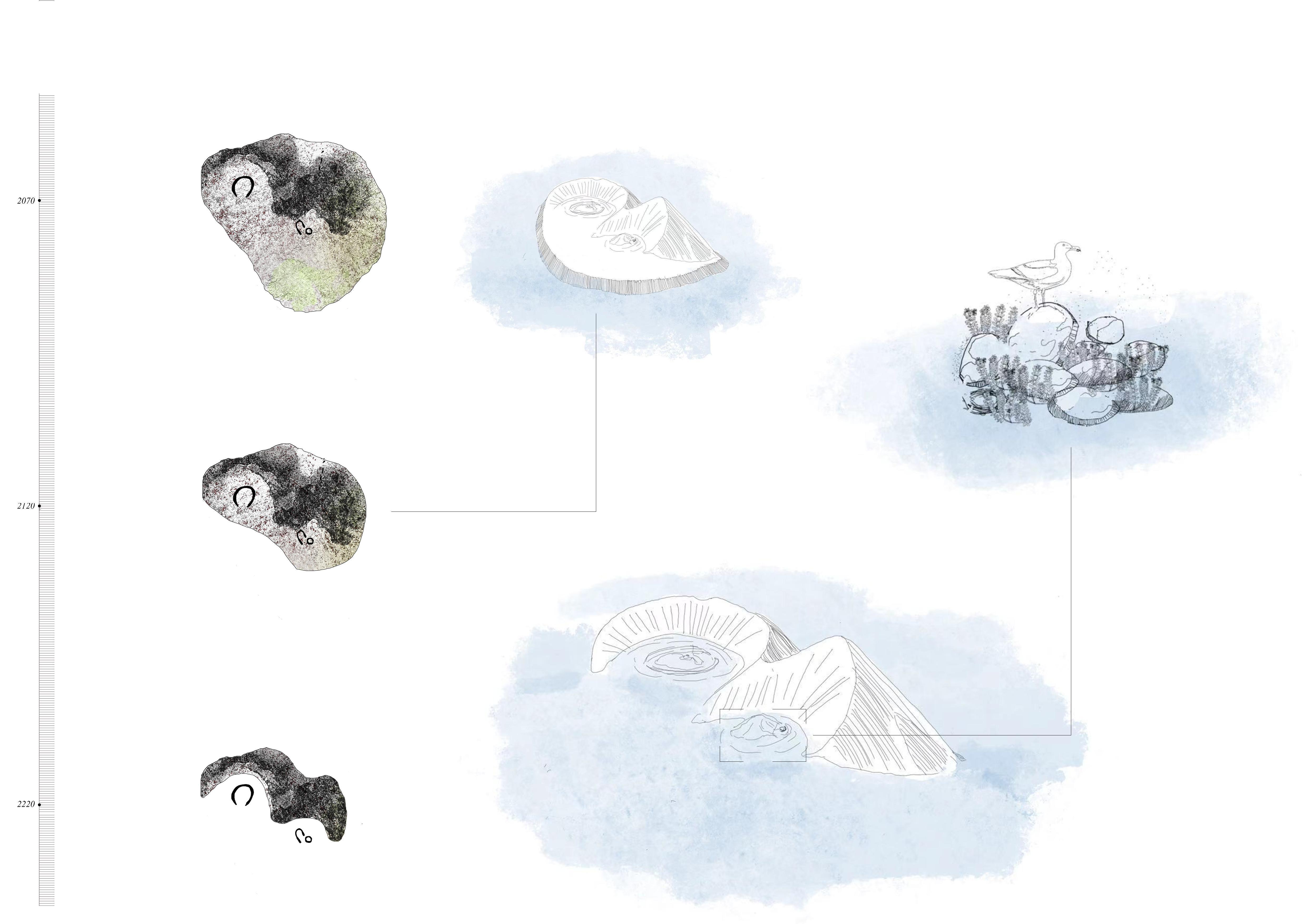

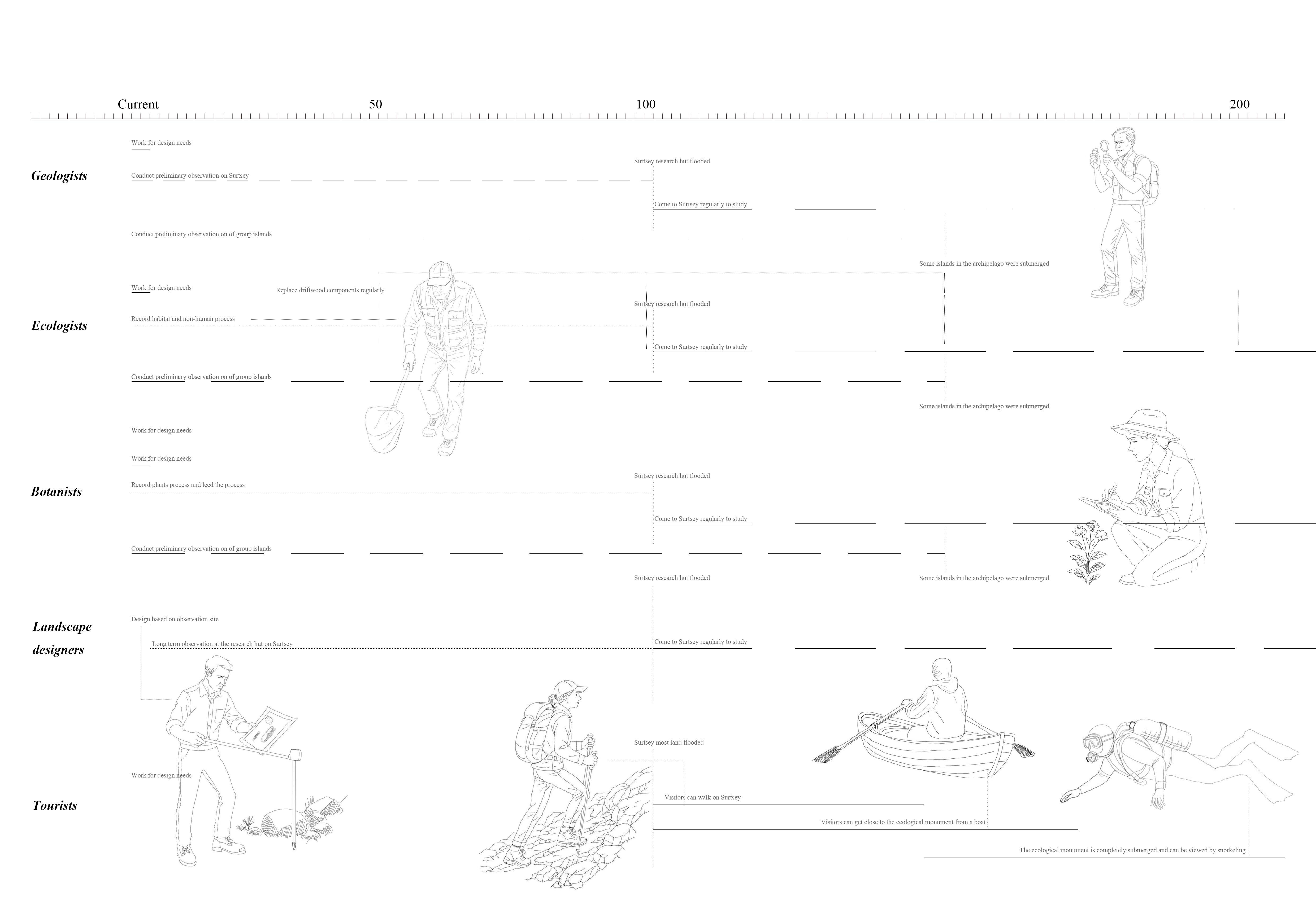

The design envisions a two-century time frame: in the first 100 years, scientists and experts work together to collect volcanic materials from all over the Westman Islands, install the ecological monument, and conduct trials and management; in the next 100 years, as the sea reoccupies the land and Surtsey's ecology stabilizes, visitors are allowed to enter Surtsey to witness the changing interactions between humans, plants, animals and materials. This long-term collaboration between human and non-human factors is at the heart of the landscape transformation. Two hundred years later, when only the volcanic cone remains on the island, the ecological monument and the stack will remain - the plants evolve and the shapes are reshaped - as a new habitat for non-humans, and when visitors come here, they can witness the evidence that life once touched this place and remember the story of Surtsey.

Scene in 2125

Scene display of four venues

Live material and plant colonization at the territorial scale

Rebirth after a volcanic eruption- Surtsey

Initial colonization of the north

Successful colonization of the East

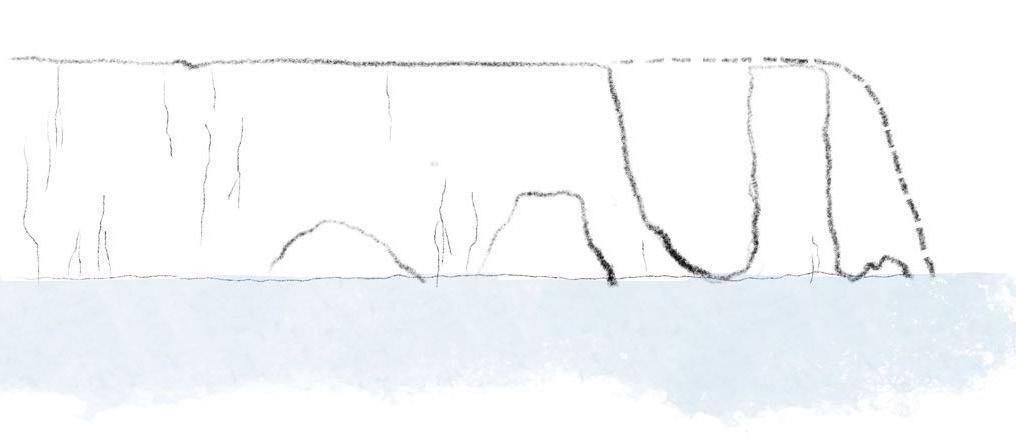

Vegetation establishment on the eastern sea cliffs

Vegetation establishment on the eastern sea cliffs

A future destined to disappear

Different material combinations lead different ecosystems

Predicted Future of Vestmannaeyjar group island

All volcanic islands share a similar fate to Surtsey

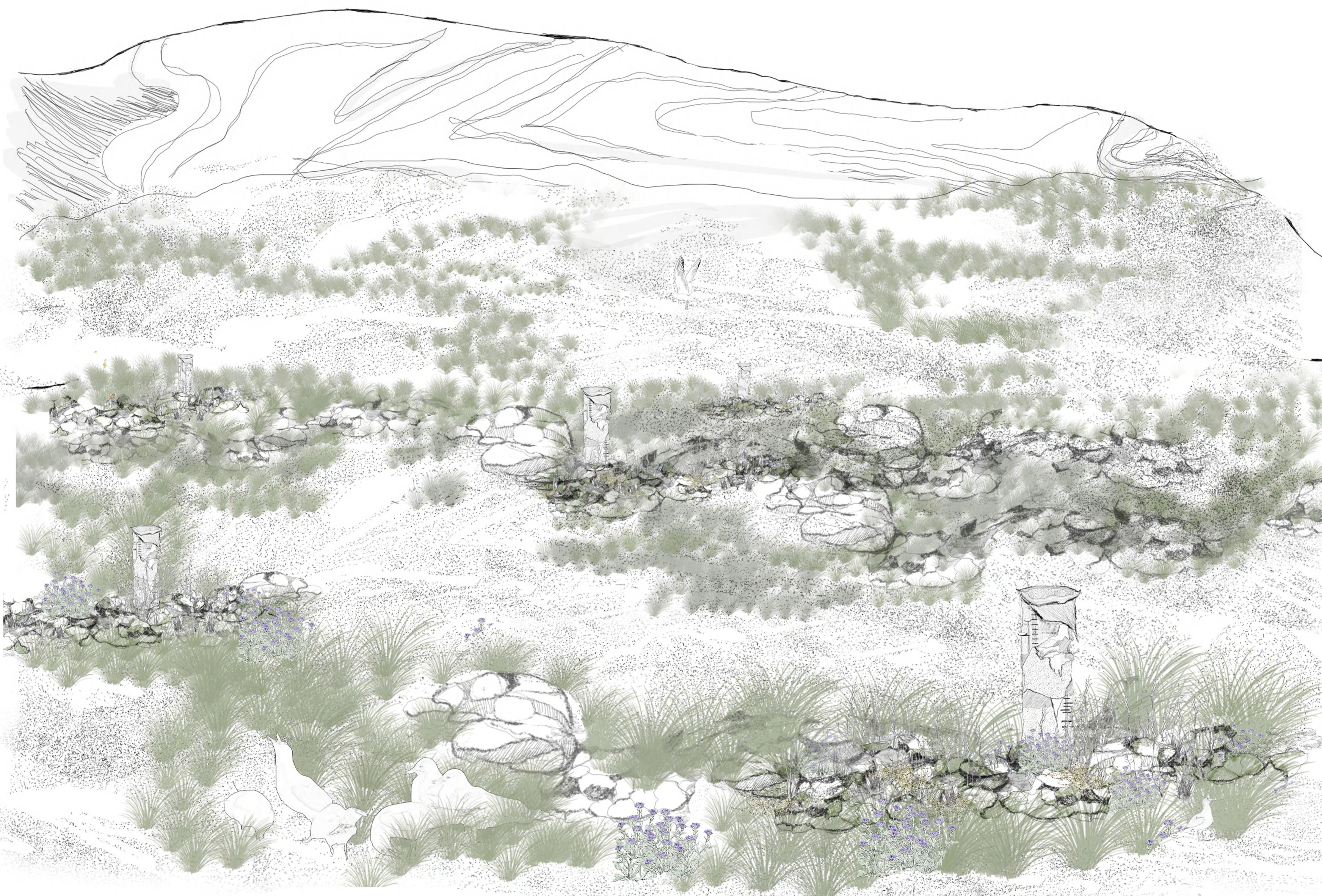

The ecological monuments are first installed by a group of scientists and ecologists.

Each basalt and driftwood structure is placed with care— embedded into the sand spit, crater rim, nesting zone, and rocky plant bed.

At this stage, the island remains closed to the public. Only researchers traverse the landscape, monitoring wind, birds, and spores.

Early signs of life begin to appear: mosses cling to porous rock, seeds settle into softened driftwood, and lichen spreads in fine silver webs.

Time begins to write itself into the material.

The islands are shrinking due to erosion and rising sea levels

The islands are opening to tourists. They arrive by boat, carefully following the eroded coastline and the sunken sandspit.

Today, the remains of ecological relics are integrated into the landscape - weathered basalt columns stand at an angle, softened driftwood crumbles into mud, and wild mosses cover the surface.

Birds nest in the empty crevices and seeds grow in forgotten joints.

This landscape no longer remembers its creator, only its changes.

Most of the island has disappeared, leaving only the volcanic cone and the dense basalt bedrock nearby.

Some of the pillars are covered with salt mosses and seabird nests, while others are submerged in the water, providing shelter for fish and soft corals.

Humans can only travel by boat, quietly shuttle between the pillars, or dive to see the ecological monument.

Only life continues in the place once designed.

In the first few years, the northern spit appeared and disappeared with the changing of seasons.Winter storms eroded its fragile form, submerging low-lying paths under the sea. In summer, sediments slowly returned, driven by currents, winds, and waves, reshaping the narrow landscape. During this phase, a team of researchers began placing ecological monuments

The spit was flooded and turned into a shallow beach, and some of the driftwood had softened, hollowed out, or collapsed into the sediment. Mosses began to grow in the

where water had gathered. The columns are no longer pristine devices; they have become part of the dynamic system they once measured, an ecological monument arranged to record the encroaching seawater,

In the early days, the East Shore remained stable—a vast rocky plain of solidified lava and ash. It was here that the first seeds took root. Mosses clung to tiny cracks in the basalt; tiny flowering plants began to grow Scientists see this area as the island’s ecological threshold—the first evidence of life.

The land was eroded, leaving only fingers of land exposed above the sea. On top of it, an ecological monument still stands. Grass and moss bent by the wind cling to its cracks. Birds roost here, rest, and leave traces. Lighter seeds fall, caught in the grooves on the east side of the monument, and germinate in the shallow humus.

The monument is no longer part of the ground - it is part of the sea, part of memory.

It no longer exists as a building, but as evidence of something growing, even on this land that has disappeared.

The southern edge of the island is high and open, with abundant nesting space.

More and more seabirds arrived here - first gulls, then puffins and Arctic terns. They began to nest between rocks, around basalt columns, and even on driftwood embedded in ecological monuments. Their presence transformed the land: feces nourished the soil, seeds from other islands floated in feathers, and algae and mosses followed.

This was no longer just a lava field. It was a habitat in the making - noisy, layered, and full of life.

The flocks grew denser.

Bird wings beat against the grass, leaving marks, and the soil darkened under the weight of guano and time. Small shrubs that tolerated salt and wind began to take root among the monuments. Their roots stabilized the soil. Insects followed, and the food web grew thicker.

Today, the columns are embedded in a thriving, self-regulating system. Some serve as windbreaks, others as habitats or territory markers. The line between design and ecology blurs—the monuments become invisible under the shadow of life.

This was no longer just a lava field. It was a habitat in the making - noisy, layered, and full of life.

The land began to sink.

As the seasons changed, the southern region gradually dropped below sea level, becoming a tidal wetland. By the end of the second century AD, it was no longer land, but a shallow seabird reef that emerged only at low tide.

Most of these remains are gone—buried, submerged, covered in seaweed. But the birds still come back. They circle overhead, alight on exposed rocks, and nest on seasonal sandbanks.The line between design and ecology blurs—the monuments become invisible under the shadow of life.

This was no longer just a lava field. It was a habitat in the making - noisy, layered, and full of life.