Earthlings: Moss In The City

Polytrichum commune - one of our largest mosses

Fontinalis antipyretica - the waving fronds are a common sight in rivers and lochs

Andreaea blyttiia very rare species of flat rocks in areas where the snow lies very late

Tortella tortuosa - a common species of lime-rich rocks

Ctenidium molluscuma - a moss of mountain limestone on Ben Lawers and in Glen Feshie

Sphagnum pulchrum - an uncommon bog- moss of wet areas in undisturbed mire

Robert Klips

Dave Genney

Tucker County

Sharon Pilkington

Mike Ball

In every hidden corner of Scotland, moss silently weaves a lush green carpet. These tiny yet resilient plants reproduce through spores, flourishing without the need for flowers or seeds. Scotland, a paradise for mosses, is home to around 1,000 species of bryophytes, including mosses, liverworts, and hornworts, accounting for 87% of the UK's total and over 60% of Europe's bryophyte flora. In this land, 5% of the world's moss species quietly thrive, showcasing the marvels of life.

The diverse landscapes of Scotland, combined with a climate heavily influenced by the Atlantic Ocean, create the perfect conditions for mosses. Warm winters and cool, wet summers, especially along the west coast, provide an ideal environment for these green gems. Nestled in damp, shaded spots, adorning soil, rocks, and tree trunks, mosses write a silent poem of nature with their lush presence.

Mosses are not only integral to Scotland's ecosystems but also provide valuable peat fuel for Highland communities. These peatlands, formed from the remains of dead sphagnum mosses, have brought warmth to countless homes during the cold winters.

Scotland's mosses are a sparkling gem in the natural heritage of our planet. They contribute not only to the rich biodiversity of ecosystems but also play an indispensable role in human history. The presence of mosses is a generous gift from nature, deserving of our reverence and celebration.

Takakia, the world's oldest moss living in the Himalayas, has thrived in extreme environments for 390 million years. However, human-induced global warming is now posing a serious threat to them.

470 million years ago, when the earth's land was still barren and nearly devoid of life, mosses evolved from green algae to become among the first pioneers to venture onto land, heralding the dawn of terrestrial ecosystems. Their arrival paved the way for future life forms. Mosses took root on the desolate rocks, quietly accumulating minerals and organic matter, eventually giving rise to the earliest soils. These primordial soils set the stage for the growth of other plants and the blossoming of complex terrestrial ecosystems. The presence of mosses transformed this once desolate planet into a thriving, verdant world.

Compared to the brief history of humankind, the journey of mosses is one of enduring resilience. They have witnessed countless cycles of climate change, species evolution, and mass extinctions on Earth. Whether on the ice-covered rocks of polar regions or the humid floors of tropical rainforests, mosses have found ways to survive. It is this remarkable adaptability that has allowed mosses to persist for hundreds of millions of years, making them one of the most ancient and enduring life forms on Earth.

3.8 billion years ago

Microbes

A billion years ago

Green algae

470 million years ago

Mosses

230 million years ago

Dinosaur

25 million years ago

Ape

300,000 years ago

Human

What is left if we aren’t the world? Intimacy. We have lost the world but gained a soul—the entities that coexist with us obtrude on our awareness with greater and greater urgency. Three cheers for the so-called end of the world, then, since this moment is the beginning of history, the end of the human dream that reality is significant for them alone. We now have the prospect of forging new alliances between humans and nonhumans alike, now that we have stepped out of the cocoon of world.

Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World

In the concrete jungles of cities, moss— a tiny plant—often goes unnoticed and is even considered an unwelcome intruder. Many people view moss as merely an unsightly plant that can damage roofs and lawns, leading to its prompt removal. However, throughout history, moss has served many purposes and provided significant benefits to humanity. For example, moss was used as a building material; in Northern Europe, it was often employed to fill gaps between wooden houses, offering natural insulation.

Moss possesses antibacterial properties, and in the past, it was used as a wound dressing to aid healing. It was even used as bandage material during World War I and World War II, as it could keep wounds clean and absorb blood. For centuries, Indigenous peoples have used moss bags to keep babies snugly wrapped. These bags create a warm, womb-like environment that helps the baby feel safe and sleep better.

As time flows, mosses have quietly migrated from the distant wilderness, seamlessly integrating into the embrace of urban landscapes. These green spirits, once confined to the wild, have now found new homes in the crevices of the city. In the concrete jungles of urban environments, mosses not only survive but also gradually evolve into species uniquely adapted to city life.

They silently cling to the cracks of pavement stones, the walls of buildings, rooftops, and even the edges of sidewalks, flourishing in the cool, damp corners of the city. Ingeniously, they exploit the microclimates and structures unique to urban areas, carving out a niche for themselves in these modern oases.

Though often overlooked or even removed as "weeds," urban mosses play a vital role in the ecological tapestry of cities. Mosses are not only an important part of urban ecosystems, they are a refuge for many organisms in cities. As the foundation of ecosystems, mosses provide habitat for tiny animals, insects and microorganisms.

In addition, mosses play a key role in purifying the air, keeping the soil healthy, and regulating humidity. Mosses are able to absorb moisture and pollutants from the air, storing these harmful substances in their own bodies and helping to purify the air quality of cities. Their resilient adaptability and ecological functions make them the silent guardians of the city, providing a healthier and more sustainable living environment for city dwellers.

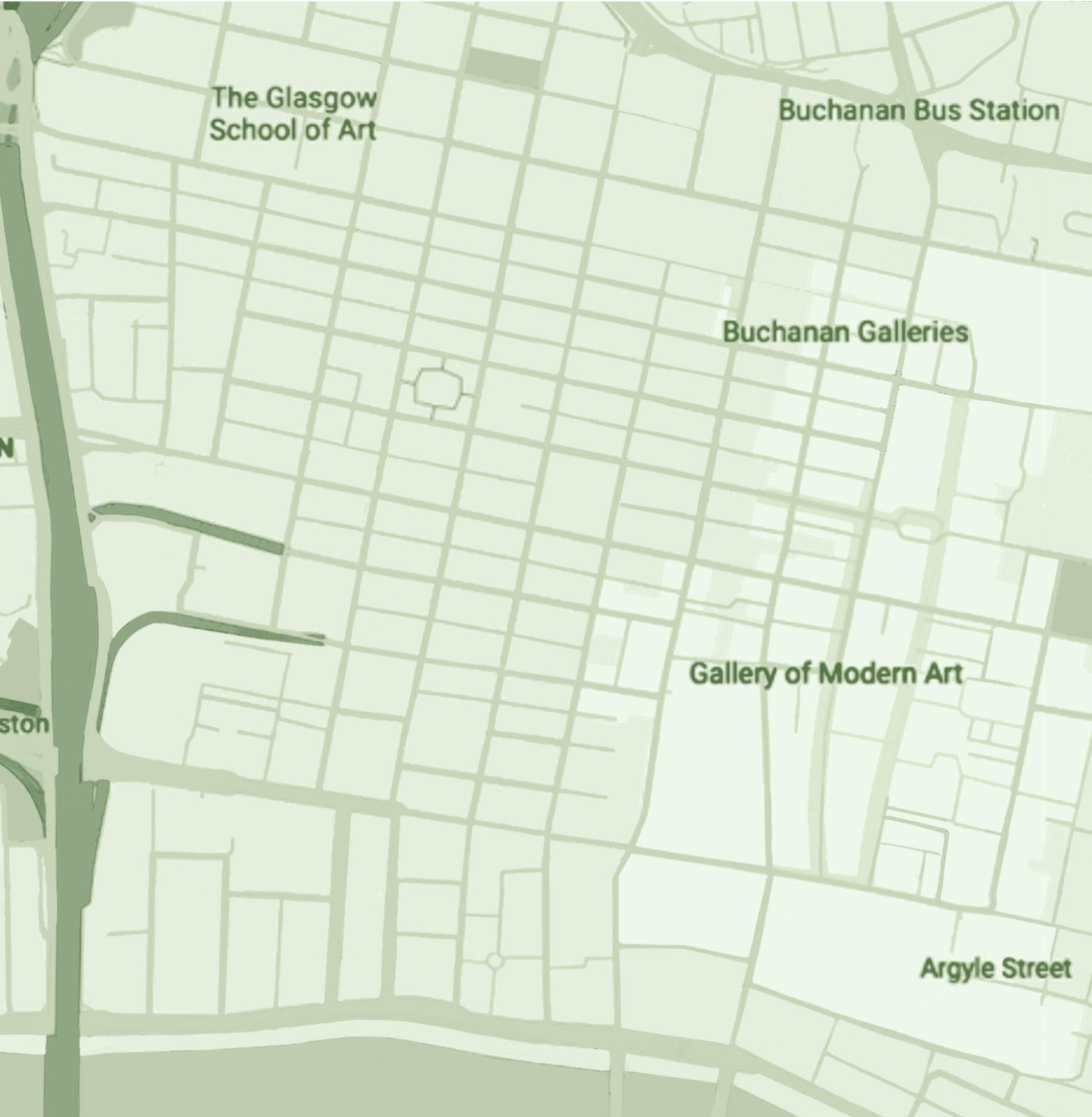

1.Brown Street

2.Bromielaw

3.Anderston Quay

4. Lancefield Quay

5. Elliot Street

6.Finnieston Street

7.Finnieston Street

8.Finnieston Square

9.Washington Street

10.William Street

11.Saint Vincent Street

12.Elmbank Street

13.Renfrew Street

14. Aloysius Church

15.Garnethill Park

16. Haldane Building

3 4 5 6 7 8

I took a walking field trip around Glasgow's city centre area to observe where the mosses were growing. This investigation also aims to find out if mosses are living in large and thriving numbers in the city and how close they really are to us. I took a lot of photographs to document where I found the mosses and created a map to show where I walked and where I found the mosses. I have categorised the main places where moss grows and you can find it on pavements, roadsides, parks and many other places in the city. Besides that, rooftops, gardens, and trees are also places where they often appear.

1 2 3 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

Even though mosses are very adaptable, they are rarely found in high-traffic central areas. Perhaps because people trample and pollute too much, the majority of plants are planted artificially.often appear.

1.Brown Street

3.Anderston Quay

2.Bromielaw

10.William Street

11.Saint Vincent Street

13.Renfrew Street

14. Aloysius Church

15.Garnethill Park

15.Garnethill Park

16. Haldane Building

You’re an earthling with other earthlings, and our job is to figure out how to live and die well, with other earthlings. “Nature,” for Westerners and people who have been influenced by Western histories, tends to mean “that which is separable from human activity,” and you might add in a few indigenous people, but only insofar as they are more natural than you are.

Tools for Multispecies Futures Donna Haraway

Haraway use ‘earthlings’ to refers to all beings living on Earth, emphasizing a collective identity that includes humans, animals, plants, and other forms of life. It highlights the interconnectedness of all life forms and the shared responsibility to live and die well together on the planet.

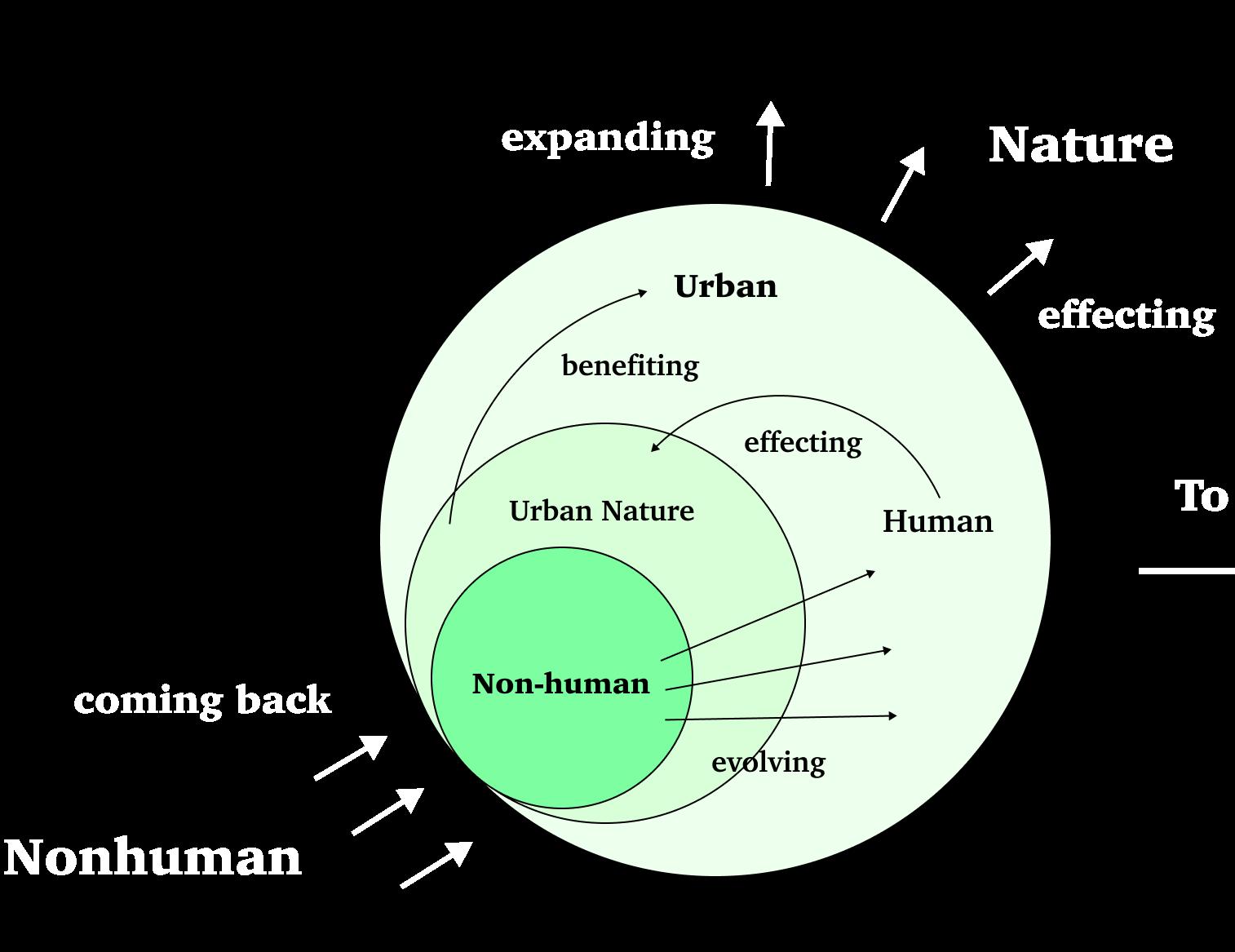

In the project, ‘earthlings’ earthlings stands for the fact that all forms of life on Earth are the Earth citizens that all forms of life have rights to live on this planet and we have a responsibility to take care about all of them . This care requires a recognition of the intimate relationship we have with non-humans, and the need to establish deep communion with them.

To reach a harmony with all non-human beings, we need a collective identity to build relationships with each other. We need a language that goes beyond binary to break down anthropocentrism and move towards an ecocentric, multispecies world

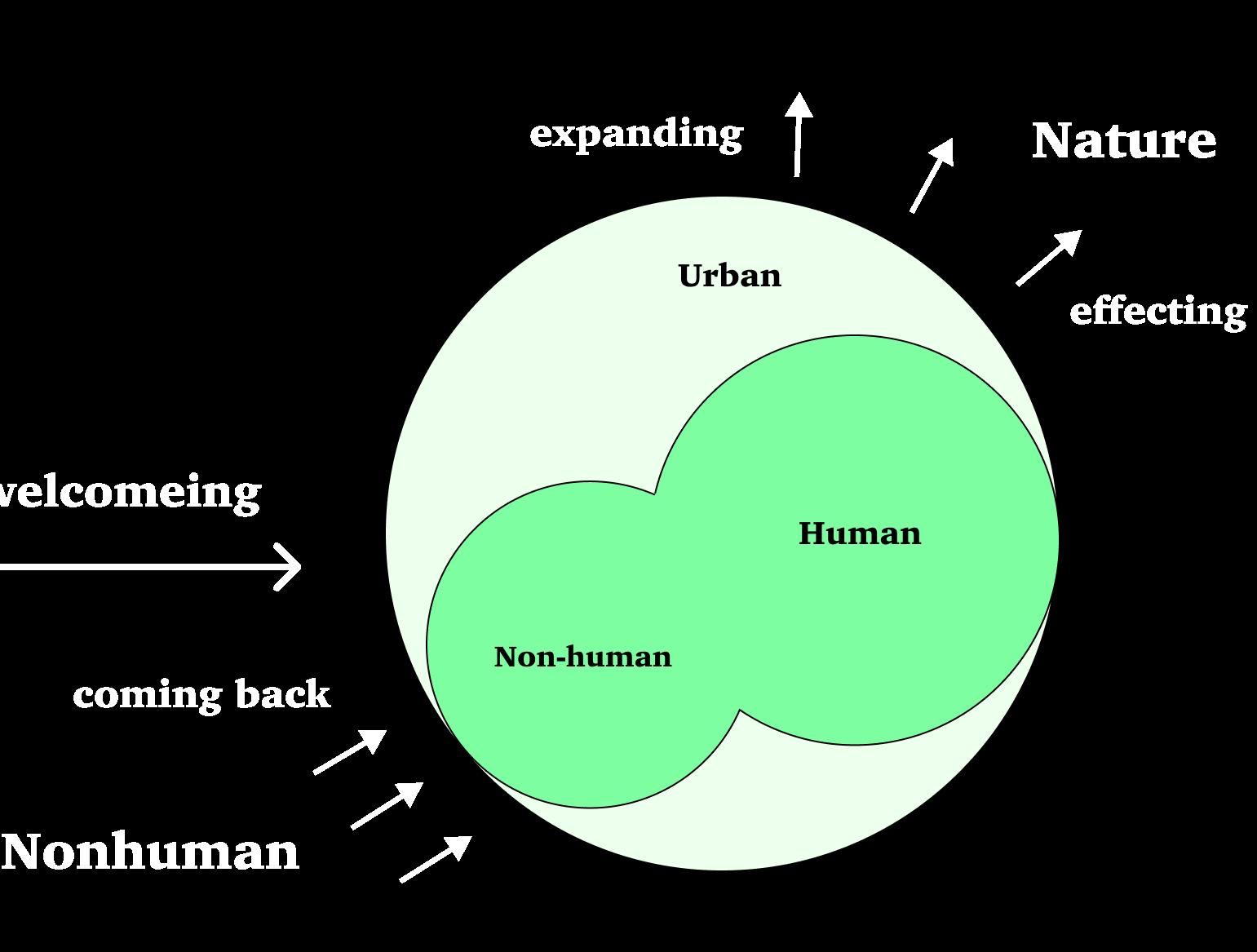

As urban continues to expand and the Anthropocene impacts on nature, non-humans will increasingly evolve and return to places that were once part of nature. In humandominated cities, the binary of human and non-human will keep increasing the conflict between the two —— people want nonhuman nature under control, but nonhumans are independent and free.

Future

Wherever humans gather, there will be cities. The border between urban and nature will not disappear. But the dominance of cities may be pluralistic. Humans have created cities out of nature using nature, and it is time to let nature take over a part of the city to be inhabited by non-human beings. We need to accept that non-humans share the city as they originally belonged here.

“They think of it as the only way they can possibly address the ongoing extractivism of capitalism and commodity consumerism and militarism, the world they are part of, is through figuring out how their skill sets can enhance caring for each other as earthlings and open up opportunities that are not about yet more capitalist growth, which is killing us dead.”

Making Kin: An Interview with Donna Haraway