+ NICKY CAMPBELL + AFUA HIRSCH + JOSH WIDDICOMBE

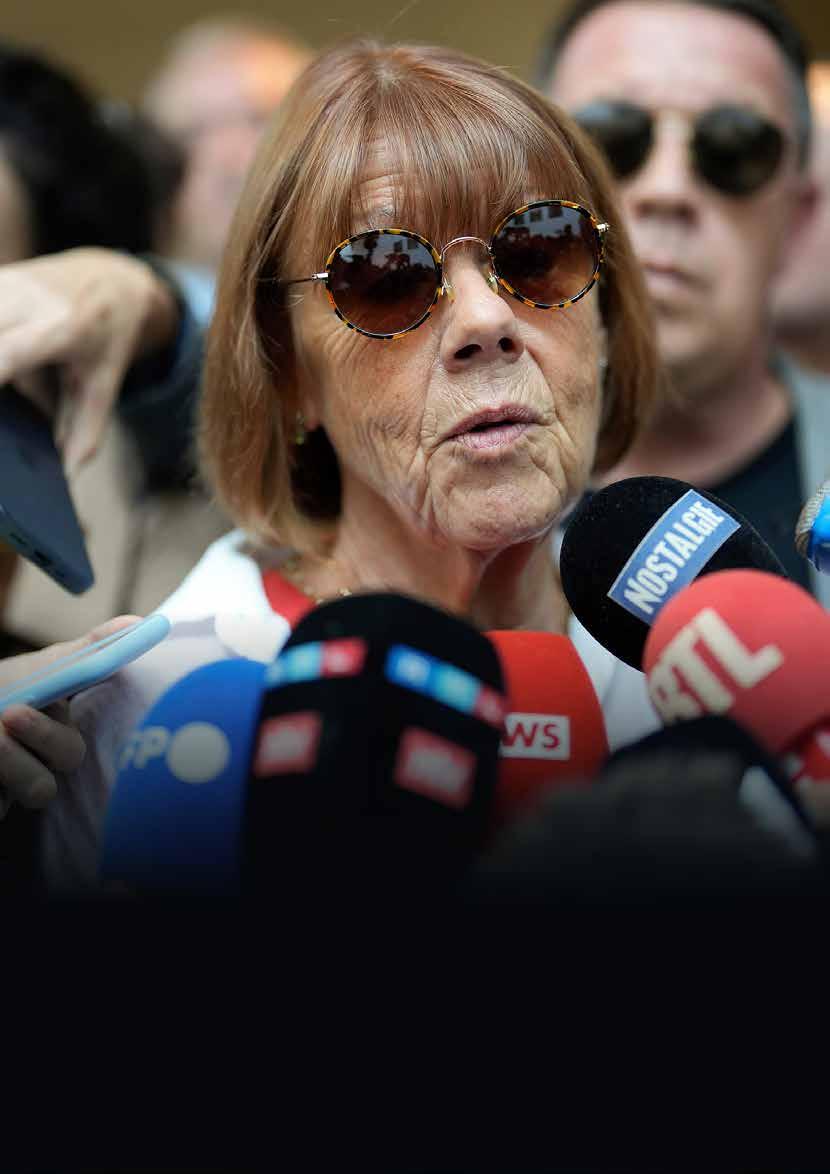

THE PELICOT FILES

The inside story of France’s trial of the century

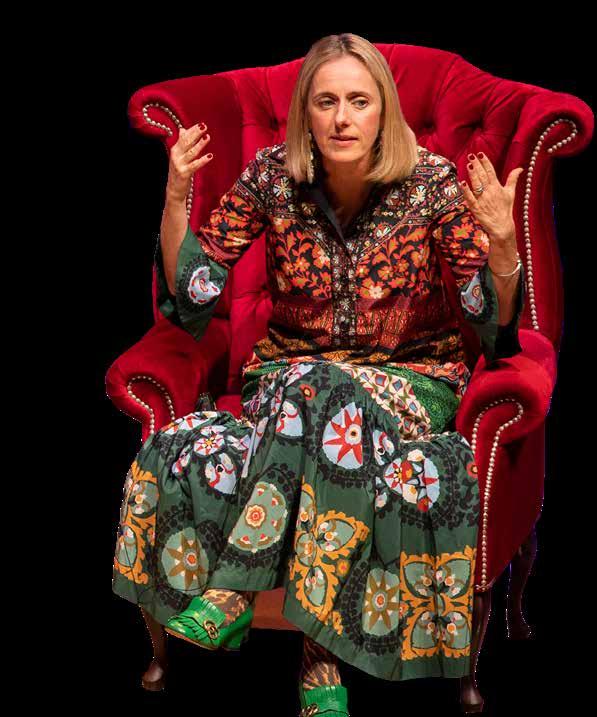

You wouldn’t ask a man that

TURNING TABLES ON MALE JOURNOS

Marina

“Did I really say that?” is appalled. Or is she? Hyde

+ NICKY CAMPBELL + AFUA HIRSCH + JOSH WIDDICOMBE

The inside story of France’s trial of the century

You wouldn’t ask a man that

TURNING TABLES ON MALE JOURNOS

Marina

“Did I really say that?” is appalled. Or is she? Hyde

When I was asked why I wanted to be editor of XCity, I knew I wanted to be involved in the creation of a magazine that captures the diverse interests and talents of its writers. The result is a magazine that delves deep into stories – from fashion, to politics, to photojournalism – and reflects the insightful reporting of a cohort dedicated to carving out their own voice in a broad and colourful industry. However, I, like my peers, can sometimes find myself suiting my voice to fit what I think people want to hear, rather than having the confidence to always speak my own mind. With this in mind, we look to seasoned journalists for inspiration on how to navigate this predicament.

Our cover star, Marina Hyde, exemplifies this with her incisive satirical commentary. She reminds us, as young journalists, that while authenticity is crucial, we must not shy away from making our voices heard, and also not fear how they will be received (p.84).

Finding this voice can be challenging in an industry that continuously faces pressures to write without fear of restriction. Trump’s latest executive order to dismantle the federally funded Voice of America casts a dark cloud over the future of press freedom (p.44), and the recent resignation of Ann Telnaes, former cartoonist for The Washington Post, raises concerns regarding the role of political satire in publications owned by billionaires (p.46). The continued need for sharp, balanced political commentary is more important than ever, as echoed by Lewis Goodall (p.103) and by the persistent effort to voice the realities faced in Ukraine by Olga Rudenko, whilst witnessing her work crumble before her eyes as Trump redefines his worldview, should be acknowledged and duly praised (p.26).

The sacrifices made by those who fight to document truth in the face of conflict must be commemorated. We recognise the perseverance and bravery of citizen journalists in Gaza (p.61) and Sudan (p.128) who have remained dutiful in their commitment to report in conflict zones,

which has led to many lives lost in the process. We remain acutely aware of the responsibility we have to continue to support and raise up the voices of those who risk their lives to share truth with the world.

While there are many positives within the media, we still must use our platform to look inwards at our internal biases. From a lack of Muslim voices in fashion journalism (p.75) to frustrations felt by disabled journalists facing accessibility issues (p.116), we must remain vigilant in both reporting and questioning the industry itself. Afua Hirsch echoes this sentiment and stresses the need to think laterally, using unconventional means to reach wider audiences (p.34).

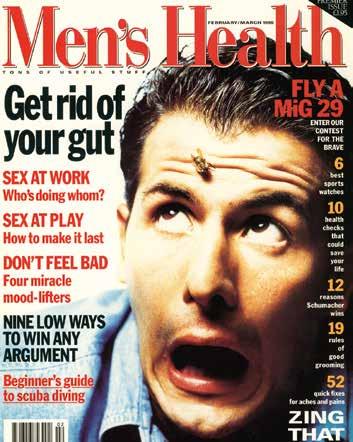

This year also marks significant milestones that highlight success in the magazine industry. The iconic New Yorker celebrates its centenary (p.66), the leading UK men’s magazine Men’s Health turns 30 (p.108), and the feminist punk zine Polyester reaches its 10th anniversary (p.32), each a testament to the enduring impact of print and digital media – a legacy we ourselves are excited to contribute to.

I am very proud of everything achieved by us all during production fortnight, and we have created a magazine that captures the great writing talent of this cohort. While InDesign may have felt like an alien concept to us in January, the past two weeks struggling together to figure things out has led to the creation of a fantastically visual publication, one that we will all look back on with pride.

Hattie Birchinall, Flore Boitel, Vipin Chimrani, Isabel Dempsey, Hebe Hancock, Phoebe Hennell, Lara Iqbal Gilling, Lucy Keitley, Mallory Legg, Anna Mahtani, Yasmine Medjdoub, Declan Ryder, Orla Sheridan, Maria Vieira, Emily Warner, and Eliza Winter.

With special thanks to our creative consultant William Jack, our cartoonist Ian Baker, and to our printers Sterling Solutions.

Cover image by Suki Dhanda.

For any queries, please email Ben Falk at ben.falk@citystgeorges.ac.uk

@xcitymagazine

JOSH WIDDICOMBE

INSIDE WESTMINSTER

MARINA HYDE

MANOSPHERE

EXTREME REPORTING

FLEET STREET TO DOWNING STREET

DAY IN THE LIFE OF GRAZIA’S EDITOR

BRAZILIAN DICTATORSHIP

LEWIS GOODALL

WE’RE NOT GONNA RETIRE

30 YEARS OF MEN’S HEALTH

WHAT’S REPLACING TWITTER?

ETHICS OF PERSONAL ESSAYS

JOURNALISTS DRAWN BY AI

LETTERBOXD FOUR

ACCESSIBILITY DENIED

AN ODE TO MAGAZINE FREEBIES

GEMMA CAIRNEY

DRAWING THE SHORT STRAW

THE BIRMINGHAM SIX

DIGITAL NOMADS

REPORTING ON SUDAN

YOUSRA ELBAGIR

WHAT PUBLICATION ARE YOU?

Anew United Nations (UN) project will study the phenomenon of online violence against women human rights defenders (WHRDs).

Dr Julie Posetti, Professor of Journalism at City St George’s, was part of initial discussions this March, at the annual Commission on the Status of Women in New York.

The new project brings together women editors and journalists, international human rights lawyer Caoilfhionn Gallagher, and representatives from UNESCO, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), and Reporters Without Borders.

The UN greenlit the project following Dr Posetti’s work on the UNESCO research paper “The Chilling”, which revealed alarming levels of online violence targeting women journalists globally. Published in 2020, “The Chilling” surveyed over 700 women journalists and analysed over 2.5 million social media posts in 15 countries.

Dr Posetti said: “It’s work that looks at the trajectory from digital threats to offline harm. [It understands] online violence as a problem which is leading to potential physical consequences, alongside psychological injury.”

“The Chilling” has caused a significant shift in action against addressing the issues of online violence. Dr Posetti said: “Never in my career as a journalist or an academic have I experienced this kind of impact.”

The survey results of the new UN project for WHRDs will be published in

March 2026, coinciding with International Women’s Day. Some data insights will be revealed before this date.

Since 2021, as part of the reaction to “The Chilling”, a new “online violence alert and response” system has been developed through funding from the Foreign Office and Luminate, a philanthropic organisation. It uses a partly AI-enabled system to analyse social media posts attacking women journalists.

Dr Posetti explained: “It is a system built with a human rights core. The system has identified 15 indicators for the escalation of online violence against

To celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Department of Journalism at City St George’s in 2026, we need YOU.

For the “City Gold Nuggets” initiative, alumni are encouraged to nominate outstanding stories that originated from City St George’s alumni. The selected pieces will be showcased in a special celebratory event.

A panel of experts will select 50 standout stories, which will then be put to a public vote to determine a final shortlist. The selected journalists will collaborate with current students to create profiles, films, and podcasts celebrating their work.

Head of Podcasting, Sandy Warr, is

women journalists, which are baked into the detection algorithms.” If funding becomes available, the UN project hopes to create a similar system to detect online violence aimed at WHRDs.

Dr Posetti noted the importance of her work in helping women in danger outside the world of journalism.

“This work has ultimately allowed us to see women journalists as proxies for [other] women in public life being targeted in online contexts, as a way of trying to shut them down, shut them up.”

By Alice Lambert

among those spearheading the project. Ms Warr said: “I have been [part of the Department of Journalism at] City St George’s for just over half of these 50 years, and it is an immensely proud moment when I read a headline or see a news story reported by a former student.

“This anniversary is an opportunity to reflect on our legacy and reaffirm our commitment to the next 50 years.”

To participate, alumni are encouraged to submit a short summary of their nominated story, along with their contact details, to Sandy.Warr.1@citystgeorges.ac.uk, using the subject line “50 at 50”.

By Hannah Bentley

Glenda Cooper joined City St George’s as the new Head of the Department of Journalism in September 2024. However, she is not a stranger to the university. Dr Cooper completed a postgraduate diploma in Newspaper Journalism in 1994 and a PhD in Journalism in 2016, both at City St George’s.

When asked what had motivated her to make this career shift, she said “who wouldn’t?

“To have responsibility for a department, to think about what we should be teaching, and to talk to so many journalists is an incredible privilege.”

Dr Cooper was previously a senior staff writer and editor at The Independent, Daily Mail, The Sunday Times, and The Daily Telegraph, and a health reporter for BBC News.

Now that she has returned to City St George’s, she has revealed some of her favourite things.

Favourite local restaurant:

“Santoré, an Italian restaurant. I’m an Exmouth Market devotee. If you’re a student who hasn’t got much money, and you want to eat a lot of food, then go to Santoré.”

Favourite book:

“Rivals by Jilly Cooper.”

Favourite thing about her new office:

“I love the natural light, and I walk out my door and I see students everywhere, so you really feel like you’re part of the community.”

Favourite thing about City St George’s:

“It’s really cheesy, but it’s the staff and the students. [There are] such amazing staff here with a wide variety of experience and [they’re] just really nice people.”

By Tiago Ventura and Hannah Bentley

The

meet

All journalism MAs and pathways will have AI skills embedded into their courses under proposals being considered by the department.

A separate enhanced AI news reporting module is also being considered for postgraduate students at City St George’s after implementing a successful module with third year undergraduates.

Dr Glenda Cooper, the new Head of the Journalism Department, said: “We are planning to make that part of the PGT [Postgraduate Taught] studies and embed AI across all degrees.”

She added: “It’s clear that AI is part of the tool kit for journalists. It’s about students using it responsibly and where it’s to their advantage. At the same time keeping to the high ethical standards City, St George’s is famed for.”

This represents a shift in the department towards further enhancing journalist’s ability to use AI to refine their journalism and aim to keep pace with the rapid progression of the media landscape.

“AI is not going away. What I think is really important for us as journalists is to see where it can be used as a tool and where it shouldn’t be,” said Dr Cooper.

Dr Cooper likens these rapid digital transformations to what past journalists saw occurring around them when other technological developments happened.

“I’m sure when telephones came in, people said that was cheating. When the web came in, people wedded to cutting libraries said, ‘You shouldn’t look online.’ Now, all of these can be tools. It’s just where do you draw the line? And that’s something we need to think about.”

Yet, the Head of Department remains optimistic that artificial intelligence cannot match journalistic ability. She said: “Journalism is about telling a story accurately. It’s about going to sources and finding out information. It’s about resilience and teamwork, and ChatGPT cannot do that.”

Looking at the future, Dr Cooper believes there is a significant appetite for not only other forms of journalism, but also a return to local journalism.

“Local journalism is one of the most important journalisms you can do. We see what happens when local journalism doesn’t happen – the classic case is Grenfell. There hadn’t been enough local journalism for the concerns raised before that tragedy happened.”

To keep pace with industry trends, the department is also considering introducing a newsletter elective, recognising its rapid growth within independent journalism.

Dr Cooper said: “Recently, people on Substack are creating small local outlets, either as newsletters or blogs. So there is an appetite for what’s going on locally.”

The current conflict between Russia and the west had its origins in the 1990s with the breakdown of relations between Presidents Bill Clinton and Boris Yeltsin, according to a new book by City St George’s lecturer Dr James Rodgers.

The Return of Russia: From Yeltsin to Putin, the Story of a Vengeful Kremlin, due to be published later this year, charts the relationship between Russia and the west since the end of the cold war and asks an essential question: how did we get here?

The Return of Russia refers to a range of issues which arose in the 1990s: western policy on the former Yugoslavia, NATO enlargement, the failure of democracy, and the rise of the free market economy. Rodgers concludes that, by the end of the decade, renewed conflict was inevitable.

Since Vladimir Putin invaded Ukraine, tens of thousands of people have been killed. Dr Rodgers said: “There’s a tendency to see the 1990s as a time when relations were warm – Yeltsin and Clinton got on so well that people called it the

“Bill and Boris Show”. Actually, I think that’s where the relationship went wrong.” He pitched his idea for The Return of Russia in January 2022, and had to revise the proposal to reflect Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February of that year. He interviewed two NATO secretary generals for the book, as well as Russian advisors to both Downing Street and the White House.

During his two decades as an international journalist, Dr Rodgers has reported on the fall of the Soviet Union, the wars in Chechnya, and Putin’s meteoric rise to power. He has been stationed in Moscow, Brussels, and Gaza as a foreign correspondent with the BBC.

Rodgers added: “Journalism is the first draft of history.”

By Emily Warner

Arts and culture critics fear giving opinions due to online trolling, according to a City St George’s lecturer. Social media has expanded access to arts criticism, but has also made professional reviewing riskier.

Kat Lister, the tutor for the Arts and Culture elective, said: “Critics can feel anxious about being trolled online after a review. I didn’t have to think about that when I started in journalism.”

Despite the democratisation of arts criticism, the notion that reviewing is reserved for an exclusive few persists. Ms Lister, a freelance arts and lifestyle writer, sees this hesitation in her students.

“We aim to break things down so the industry is less intimidating,” she said.

The course blends academic understanding with practical skills, such as

navigating relationships with editors and publicists. The curriculum evolves each year, with pitching identified as a recurring source of student anxiety.

“I focus quite a bit on that, but each year is fluid,” said Ms Lister. “We aim to build confidence in writing without losing the passion for culture.”

Students gain hands-on experience through an annual field trip. This year, they reviewed Citra Sasmita’s Into Eternal Land at the Barbican.

Ms Lister said: “I pick an exhibition where there’s a lot to tap into. It’s an opportunity to put everything into practice and build confidence.”

Students’ enthusiasm for the elective remains strong, as it had to expand to two classes this year.

By Romy Journee

Abandoning the safety of her desk, Naomi George is hiking to Everest Base Camp to film footage for her final project

By Isabel Dempsey

Student journalists are often unwilling to pick up the phone or stop someone in the street, preferring the safety of an email or social media DM.

So, it may come as a surprise that Broadcast MA student Naomi George is travelling to Nepal for her final project, where she will hike around 80 miles to Everest Base Camp.

While she doesn’t yet know the exact details of her project, Ms George, 31, is “a bit of an adrenaline junkie” and “intrigued” by what a day walking on the world’s highest peak looks like.

She said: “More and more people are climbing [Everest] every year. I’ve seen YouTube clips of people queuing to get the picture at the top. It’s wild.

“I’m so excited to hear the stories of other people on the trek [and to] share that journey with others who have their own ‘why’ for being there.”

Ms George will leave the UK on 6 April. Her trek will last two weeks, with an average daily distance of eight miles.

She said: “It doesn’t sound far, but it’s very steep. It feels more like 12 miles because of the altitude. I think [the altitude] is my biggest anxiety because you can’t really prepare your body for that.”

Ms George has organised a strict training schedule in preparation for these harsh conditions: “I’ve been hitting the gym five, six days a week, [doing] work on the Stairmaster, lunges, [and] squats to

prepare my body for those steep ascents.

“In London it’s quite hard to prepare. There’s no mountains to march up.”

Ms George grew up on a farm in Wales and has been hiking since she was a child. To prepare for the altitude, she will do a few climbs in Wales before the trip. She said: “This has been a lifelong dream. I like things that test your limits.”

She travelled to Nepal in 2017, around the time when British student Charlotte Fullerton was killed by a landslide in the country’s Mustang region. “I remember my mum calling me up and saying ‘You’re not going up any mountains’.”

When Ms George’s now-husband asked

An investigative journalist and senior lecturer at City St George’s has turned his research on former Conservative MP Richard Drax’s ancestral links to slavery into a new book.

Dr Paul Lashmar’s Drax of Drax Hall, which was released on 20 March, explores the history of the Drax dynasty and its connections to the transatlantic slave trade.

The ancestral Drax family built a

fortune through the enslavement of Africans on sugar plantations. Richard Drax inherited the Drax Hall plantation in Saint George, Barbados in 2017.

Dr Lashmar said: “Pretending that slavery is in the distant past and has no consequences in the present is foolish.

“Despite pressure from reparation campaigners, Richard Drax has stood firm in refusing to make a public apology or gesture of recompense to Barbados.”

By Phoebe Hennell

her on Hinge what she would do with a hypothetical lottery win, she responded with ideas which included an Everest Base Camp trek. Five years later, this trip is doubling as their honeymoon.

The next big hurdle for Ms George is the risk assessment element of her final project, which may impede her from going. Joe Michalczuk, director of the Broadcast MA, said he was “excited but also slightly daunted” by this assessment.

“Few students push it as far as Naomi, but I’m looking forward to seeing her progress, and I’m confident we’ll see a City St George’s flag planted on Everest in a couple of months’ time.”

Mystery surrounds the future of The Peasant, once a pub popular with journalism staff and students.

The pub, formerly The George and Dragon, closed in May 2023. It was cleared of squatters after a possession claim was filed with the Central London County Court the following year.

According to an employee at neighbouring architecture business Cartlidge Levene, there has been no sign of the squatters since the end of last year.

The lives of five pioneering women, who defied societal norms to engage with and protect the natural world, are the subject of a new book by a journalism lecturer at City St George’s.

Wildly Different: How Five Women Reclaimed Nature in a Man’s World by Sarah Lonsdale draws on extensive research and interviews, including with Sir David Attenborough and Wangarĩ Maathai’s daughter, to bring these women’s stories to life.

The book, Dr Lonsdale’s third, will be released by Manchester University Press on 4 March. Wildly Different highlights the struggles women have historically faced in accessing wild spaces, and their impact on conservation.

By Hannah Bentley

“There was one occasion where there was a load of furniture on the side of the street. They’d obviously been turned out and now they’ve got all the shutters up.”

The pub is now completely boarded up, with metal barriers in each window obscuring the view inside, and all entrances blocked.

The Peasant was built around 1890 on the site of an earlier pub, with some modifications made in the late 20th century. Its interiors featured a mosaic

floor and a pipe system around the bar, used to warm patrons’ feet in winter.

The Peasant has long been a popular boozer among the City St George’s community. Jason Bennetto, who graduated with a diploma from the Department of Journalism in 1987 and now lectures for the department, said: “It had a great atmosphere, I remember evenings as a student, we would prop up the bar and get sloshed. I hope it re-opens, as it’s part of the department’s history.”

By Hanna McNeila and Lucy Keitley

An Emmy Award-winning lecturer’s Spanish skills have been key in a new initiative to increase postgraduate journalism applications from Latin America.

Last November, a recruitment talk for City St George’s was conducted in Spanish for the first time. The talk was given by broadcast lecturer Fernando Pizarro, in collaboration with his alma mater, the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, as well as the Universidad del Desarrollo in Chile, and the Universidad Panamericana in Mexico.

Mr Pizarro said: “I proposed we did it in Spanish, to make it more attractive and so that the potential students would feel more comfortable asking questions.

“We just tested the waters with three universities, I intend that to grow this year.”

A former Washington correspondent, Mr Pizarro has worked as senior editor for The New York Times and NPR. He began

teaching at City St Georges in 2022. This was the second scheme aimed at encouraging students from the American continent to apply to City St George’s. In a separate initiative, nearly 50 universities in the United States and Canada were contacted by Mr Pizarro.

Mr Pizarro said: “The Department of Journalism is always very interested in recruiting [students from abroad].”

Latin American students have traditionally looked at Europe as a prime location for studying abroad. This initiative attempts to encourage them to consider City St George’s.

Mr Pizarro said: “They look at Spain for the obvious reason of language, and Spain also has very good journalism graduate schools. But I also know that many students in Latin America look at London as a great place to come and study.”

By Marissa Goursard

provided by Kathryn Vann

The “kind, generous, and loyal” City St George’s lecturer is remembered following his death at the age of 77

By Declan Ryder

Peter Gould, a much respected City St George’s lecturer and former BBC reporter, was described as ‘kind, generous and loyal’ following his death at the age of 77.

Mr Gould, who died from an undiagnosed heart condition on 11 February, built a broadcast career in commercial radio and as a news correspondent at the BBC. Following his retirement from City St George’s in 2019,

he co-founded the Ealing Film Festival, which showcases emerging film-making talent, the following year.

His journalism career spanned nearly four decades, in which time he covered events at home and abroad, from the hunger strikes in Northern Ireland and the Hungerford massacre to the Gulf war and aftermath of 9/11.

Mr Gould taught broadcast modules on the International Journalism MA at City St George’s between 2009 and 2019. Dr Zahera Harb, director of postgraduate studies, said: “Students loved him because he cared. He always made them feel good about the work they were producing.”

His wife, Julie Hadwin, who also teaches journalism at City St George’s, said: “He just had that curiosity about stories and people. He loved the excitement of it. He was one of these people who seemed able to become increasingly calm in relation to the general chaos and panic that was going on around him.”

Mr Gould began his career as a newspaper reporter in Stockport, before moving to Bolton and then Liverpool. There he came into contact with Nick Pollard, as part of a group of young journalists launching the Radio City station in Liverpool.

Mr Pollard, the former head of Sky News, said: “He was a smart, persistent and stylish reporter who got the story by quiet persuasion rather than shouting the odds. In a notoriously cut-throat and unsentimental

business, Peter was a model of kindness, generosity and loyalty. In all the different newsrooms I worked in, I never heard anyone say a bad word about him. He was pretty much unique in that respect.”

Paul Davies OBE, a veteran ITN journalist who also worked alongside Mr Gould at Radio City, echoed Mr Pollard’s thoughts. He said: “He was a great journalist and an even nicer man.”

Outside of journalism, Mr Gould enjoyed writing plays, holding a master’s degree in writing for screen and stage, and studying theatre directing at the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama. Ms Hadwin said: “He really enjoyed being able to take what he had learnt as a reporter and then use it in more creative ways with the plays that he wrote. I think he was a born writer.”

He was also a self-professed steam train enthusiast, and an avid photographer.

“He had many interests throughout his life. He would immerse himself in each one, researching until he became really knowledgeable,” said Ms Hadwin.

He had a knack for passing on his interests to his loved ones, having transferred his support for Liverpool FC to the entire family after his time spent as a reporter in the city. Ms Hadwin also noted that their son, Jamie, pursued photography in part because of his father, and their daughter, Ellen, bonded with him over her comedy sketch writing.

In recent years, much of his focus was on the Ealing Film Festival, which he cofounded with Annmarie Flanagan and Alan Granley in 2020, and of which he was the director. “Ealing is originally the home of British cinema and Peter had always felt there should be something that celebrated that fact,” said Ms Hadwin.

The UNFPA, the UN’s sexual and reproductive health agency, has partnered with City St George’s Podcasting MA to deliver a five-part podcast series.

The key tenets of women’s equality, from medicine to finance, are at the heart of the podcast series.

BBC veteran and podcasting MA course director, Brett Spencer said: “I was introduced to the Head of Innovation at the UN because they were interested in launching a podcast. As City is the first university to globally offer a dedicated podcasting MA, it was a natural fit.”

Spencer added: “I joke to the students

that I went on holiday to New York and came back with a podcast.”

Students are working on each episode in the series as part of their final portfolio and are responsible for producing, interviewing guests, and editing the podcast.

The news comes as the podcasting MA continues to expand in size. The MA launched in 2023 with only six students, and has since tripled in size.

Graduates have gone to secure jobs at major podcasting studios such as Spotify, Goalhanger, Loftus, and more.

The series will be available later this year on all streaming platforms.

By Clara Taylor

The “Europe Press Freedom Report 2024: Confronting Political Pressure, Disinformation and the Erosion of Media Independence” was released at the inaugural UK Media Freedom Forum.

The report’s findings highlighted threats to journalists covering the Russia-Ukraine war, the detention of 159 journalists across Europe, and the misuse of legal actions against the press.

The report urged member states of the Council of Europe (CoE), including the UK, to implement reforms that guarantee both media independence and pluralism.

The Safety of Journalists Platform, which conducted the report, have recorded around 2,000 alerts concerning threats to media freedom and journalist safety since its inception in 2015.

Mel Bunce, Professor of International Journalism and Politics at City St George’s, said: “We hope the report pressures European representatives to do more domestically to support journalism. This forum shifted the conversation to underline the urgency of press freedom.”

The forum was organised with City St George’s, University of London, and supported by the CoE’s Safety of Journalists Platform, UNESCO’s Global Media Defence Fund, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), and law firm RPC.

The event covered strategic

lawsuits against public participation (SLAPPs), transnational repression, economic pressures, misinformation and disinformation, and the impact of artificial intelligence on journalism.

Susan Coughtrie, Director of the Foreign Policy Centre and the UK Anti-SLAPP Co-Chair, said: “With the attacks on press freedom we are witnessing worldwide, this discussion is urgent. Many attendees have faced funding freezes and other pressures targeting independent media.”

The Centre for Journalism and Democracy will launch in early September at City St George’s as a benchmark initiative to address threats to media freedom.

Mel Bunce, Professor of International Journalism and Politics, is leading the creation of the Centre, alongside Professor Julie Posetti

The Centre will serve as a bridge between research and real-world media practice, helping academics share critical studies with policymakers and newsrooms

“We have a huge critical mass of amazing scholars working on these issues,” said Prof Bunce. “The goal of the centre is to amplify the research we’re doing and share our insights with editors and journalists to help them stay safe and uphold democracy.”

By Tiago Ventura and Hannah Bentley

The USAID budget cut earlier this year slashed over £216m pledged for independent journalism.

“There are levers we can pull, and practical support we can mobilise — what’s needed now is the political will to act,” Ms Coughtrie said. “Defending media freedom is not just about journalists — it’s about democracy itself.”

By Hannah Bentley and Tiago Ventura

provided by

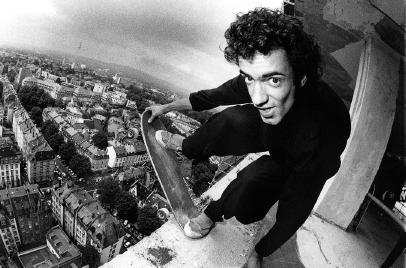

Investigative journalist Nick Davies on ITV’s new drama, as the show sidelines the scandal’s wider implications

By Tiago Ventura

Anew TV drama about the phone hacking scandal has been described by the reporter behind the expose as “disappointing” for failing to focus on the criminality of the journalists.

Nick Davies, the renowned investigative journalist, said The Hack, which stars David Tennant as himself, “really misses the target”.

The seven-hour ITV drama was filmed in 2024 and is due to air later this year. Set between 2002 and 2012, it follows Mr Davies, played by Tennant, as he uncovers the phone-hacking scandal.

This was a collection of stories, written by Mr Davies for The Guardian, about the illegal activities carried out by journalists and private investigators at News of the World to obtain private information from people’s phones.

Mr Davies, who spoke to students at City St George’s about his investigation, said: “I think it’s disappointing because it’s very much focused on me as a character.

“It doesn’t tell you anything about Murdoch or his power, or his journalists or their criminality. It’s a very odd piece of work.”

Between 2009 and 2011, Mr Davies wrote nearly a hundred investigative pieces for The Guardian exposing the phonehacking activities of Rupert Murdoch’s News of the World and the failures of politicians, police, and press regulators to hold Murdoch to account.

Mr Davies said that while he was “consulted” by ITV, he wasn’t given “any kind of control of it”.

“If I had been in charge of a drama about Murdoch, I would show the Murdoch journalists hacking phones, bribing public officials, cheating their sources, and Murdoch’s people in the corridors of power bullying politicians. But this drama is very different.”

Mr Davies’ visit and the drama’s announcement coincided with news of Prince Harry settling with News Group Newspapers (NGN). According to the BBC, NGN has spent over £1 billion on damages and legal costs linked to phonehacking claims against News of the World and The Sun

The lack of nuance in the new series comes at a particularly precarious time for

journalists in the digital age, as Mr Davies highlighted in his talk at City St George’s.

“I think there’s a danger that profit-seeking organisations who own newspapers are going to use AI as a substitute for reporters,” he said.

“Local newspaper reporters are in great jeopardy because they already spend too much time recycling press releases from the Press Association that can easily be done by AI. There is a risk that understaffed newspapers will be stripped of even more staff.”

The veteran reporter highlighted the threat to specialist journalism in an era where “consumers of information treat factual statements like chocolate cookies”.

“[They] like the taste of this factual statement, so [they] decide to believe it, [they’re] not interested in the evidence. That’s a huge problem. But I don’t think it changes the way that we should work or the importance of what we do.”

Despite the pessimistic undertones of the discussion, Mr Davies remained hopeful for the future of journalism.

“I can see another generation of young reporters coming through, some of them working on national titles, who are really good, clever, brave, and energetic. So, it ain’t over yet,” he said.

Anew course aimed at reporting stories about culture, identity, and underrepresented communities has been launched at City St George’s. The ten-week elective module ‘Reporting on Identity and Underrepresented Communities’ covers reporting on race, gender, LGBTQ+ communities, class, and disabilities, and began in January 2025. It is run by Suyin Haynes, former Head of Editorial at gal-dem magazine, who joined City St George’s this year as a lecturer.

Open to all postgraduate journalism students, Ms Haynes proposed the module in 2024 after noticing a gap in the curriculum. She said: “When I looked at the list of specialisms, I didn’t see [topics related to identity and underrepresented communities] covered in any of them. And while this module might contradict some of the others, I don’t think that’s bad.”

In the first session of the module, Ms Haynes told her students she strongly believed reporting on identities should not be considered a “niche” topic. She said: “People are now more aware and cognisant of identities, how they shape us, and how they shape the world. It’s because of that growth and public consciousness that these issues need to be explored and reported.”

On why she thinks it took until 2025 for the creation of this course, she said: “I think the combination of broader changes and a demand from students. I noticed while teaching on the Magazine course, questions around how to report these kinds of stories kept coming up.”

The course covers techniques and tools essential to reporting underrepresented stories. Classes include discussions about trauma-informed reporting, co-creational media, and includsive language.

Ms Haynes said: “We have 10 weeks so it’s limited, but it’s about having a taster of what it means to report on identity and underrepresented communities. What that looks like and how that shows up in other aspects of reporting that you might do.”

The course involves interactive elements, with various speakers attending sessions throughout the module. Aamna Mohdin, community affairs correspondent for The Guardian, Vic Parsons, freelance reporter on LGBTQ+ issues, and Lucy Webster, the author of The View from Down Here: Life As a Young Disabled Woman are among this year’s guests. Students also visited the Migration Museum in Lewisham, with a guided tour from one of the directors.

A freelance journalist covering identity, culture, and underrepresented communities, Ms Haynes said she hopes to make the class as enriching as possible. “In putting this module together, I have also been reflecting on my own career – in particular, the mistakes I have made, or what I could have done differently or better in my reporting. Early on in my career, there were times when I recognised bad practice, but felt unable or ill-equipped to be able to challenge it, which was difficult. I hope this module can help prepare and provide students with the tools, techniques

and language to navigate similar issues.

“It’s heartening for me to be able to play a small role in working with students to think about the future and what kind of impact they want to have.”

Students in the module also echo Ms Haynes’s sentiment, with many expressing their excitement with the course content in the first session. India Horner, an MA International student, said the module has given her a powerful toolbox of skills for interviewing different communities. “I think that the module should be compulsory for all students studying journalism right now. The module is a safe space that encourages us to ask questions, so we know the important questions to ask when we work in newsrooms.”

By Cyna Mirzai

Biased social media attacks on women are part of what inspired film journalist Jane Crowther to write her debut novel – a gender-flipped take on F. Scott Fitzgerald’s TheGreatGatsby

She said: “The original is a timeless book [but] is more poignant with a female perspective as it happens to women all the time. Public opinion is incredibly cruel to women.”

Crowther’s version features a female social media influencer. She got the idea during Covid while “looking at other people’s lives on social media”.

Gatsby tells the story of Nic Caraway, who finds herself in “a mess of betrayal and social scandal” when she befriends her famous neighbour, it-girl Jay Gatsby.

The main challenge for the City St George’s alum was trying to balance her day job as a journalist with writing the novel. She said: “I sacrificed things I wanted to do in order to write.”

Her career as editor-in-chief of entertainment magazine Hollywood Authentic has helped her “enormously”.

“As a journalist, you can approach writing fiction in a more pragmatic way because you have the skills to condense ideas into words.”

The book will be published by The Borough Press on 10 April 2025, exactly 100 years after the original novel hit the shelves and became a cult classic.

By Flore Boitel

A spacious and newly equipped tech room has replaced the journalism department’s cramped IT office

By Kathryn Vann

The Information Technology (IT) department has moved from their byte-sized office in AG12 to AG18, which is located next to The Pool in the College Building.

AG12’s ancillary room, used for charging batteries and storing tripods, was an awkward wedge-shape and difficult to use. AG18 comprises two rooms, with one converted into storage for camera kits and equipment and an additional cupboard for battery storage.

The spacious AG18 has allowed the IT team to expand from five to seven staff. David Goodfellow, Head of IT, said: “The previous room was only suitable for three people to comfortably work in.”

“The shared space is better in terms of communication and collaboration,” said Mr Goodfellow.

With a counter to establish an office space for staff, and a lobby for students to queue, the room is more organised. Mr Goodfellow said: “In AG12 the students would walk in bringing equipment back en masse, creating trip hazards.”

Staff also have enough space to show students how to use the equipment appropriately. “We would show students how to set up cameras on tripods in front of the fire exit, which was not ideal,” Mr Goodfellow added.

Aside from physical expansion, staff skill-sets are growing too. Mr. Goodfellow and Maria Martinez-Ugartechea now teach classes on how to use the equipment and support Media, Culture, and Creative Industry modules.

This merited the purchase of more equipment, now available for use by journalism students, including more Canon EOS 4000D cameras, bluetooth

An MA Broadcast student has credited a disability event held at Sky as inspiring her to continue with her journalism career.

Roisin Clear, 24, a student at City St George’s, said that attending the Disability Journalism Forum (DJF) at Sky Headquarters in London on 14 March encouraged her to keep going.

The event brought together some of the country’s most successful disabled journalists with the aim of improving representation of underrepresented groups in newsrooms. Some 300 people attended the event, the DJF’s largest conference.

Ms Clear, who is on the forum’s social media committee, said: “I had a blip the other day, for various personal reasons, where I didn’t know if I could keep going [with journalism].

“With journalism, also as a disabled person, it can feel like a dead end and you need to be tenacious to keep going but this event reinstated the push that everyone, but especially disabled journalists, need.”

The theme of this year’s event was ‘Impact’ and Dr Shani Dhana, the chair of the DJF, said that even if change “isn’t shiny and immediately obvious from the outside” it’s important disabled people are “changing and shaping excluded and underrepresented identities”.

Sky presenter Saima Mohsin, who delivered the keynote speech said just increasing “visual representation [of disabled people] was not enough” and that more had to be done in editorial positions.

The presenter was left with a hidden disability after a car crushed her foot whilst she was reporting for CNN from the Gaza strip in 2014.

Other speakers throughout the day included Aidy Smith, the only Global TV host with Tourette’s syndrome and Max Preston, a digital producer at Sky who is also wheelchair user with quadriplegic cerebral palsy.

By Will Lewallen

This March, City St George’s alum Anna Foster was announced as a presenter for BBC Radio 4’s Today. She will be replacing Mishal Hussein as one of the show’s hosts.

With over 25 years of experience at the BBC, Mrs Foster has presented for Radio 1 Newsbeat, Radio 5 Live Drive, as well as working as a Middle East Correspondent for BBC News for three years in Beirut. Now, she will be joining the Today programme, which averages 5.9 million listeners.

Mrs Foster studied Broadcast at City St George’s and joined the BBC training scheme on graduation.

By Anna Mahtani

TikTok is reshaping journalism and traditional media can learn from the short form video platform, a leading City St George’s academic has argued.

The advantages and disadvantages of the social media app were explored by Dr Rana Arafat, an assistant professor in digital journalism at City St George’s, in her latest research paper, ‘Unveiling the Online Dynamics Influencing the Success and Virality of TikTok Social Movements’.

Dr Arafat said: “Traditional media can learn a lot from TikTok, especially [when] amplifying underrepresented voices and making journalism more accessible.”

Her paper examines the popularity of social movements on TikTok, focusing on feminist campaigns resisting hijab bans like #Handsoffmyhijab and #WomanLifeFreedom in France and Iran.

Dr Arafat said: “TikTok is reshaping journalism by prioritising visual user generated content that is

interactive for audiences.”

She considers this format valuable in making journalism more engaging and accessible to younger people .“It has enabled younger generations to democratise information dissemination, allowing underrepresented voices to share news and perspectives outside traditional media outlets.”

She added that TikTok has also allowed younger generations “to discover and engage with social movements, such as the feminist movement, more easily”.

While acknowledging that journalists and news publications have started incorporating short-form journalism, infographics, and visuals to engage younger people, Dr Arafat argued more needs to be done.

“Journalists should learn how to use the right keywords and connect with viral hashtags to better reach younger generations,” she said.

Dr Arafat also warned about the risks TikTok presents for the future of journalism.“The emphasis on short-form engaging videos can sometimes sacrifice accuracy and depth.”

She said that due to the prevalence of misinformation and fake news, “fact-checking is essential and should be done before videos are posted on social media platforms to ensure accurate reporting”.

By Maria Vieira

provided by AP

By Clementine Scott

Ofcom has moved to clarify rules on dating app age verification to protect children from grooming and sexual abuse following an investigation by an MA alumnus.

Billy Stockwell’s piece, published in January in The i Paper, used FOIs, police forces, and interviewee testimony to explore widespread alleged sexual abuse of boys as young as 12 on the LGBTQ+ app Grindr. The investigation began as a second term project at City St George’s in 2023 as a short documentary.

Mr Stockwell said: “When I was talking to Ofcom as part of the investigation, they weren’t committing either way,” on whether or not dating apps fell under the Online Safety Act 2023.

The ambiguities in Ofcom’s previous guidance was one of many challenges Mr Stockwell faced in the course of his investigation. He also sent FOI requests to over 50 UK police forces about instances of alleged underage sexual offences reported where Grindr played a role. Many of these police forces, including the Metropolitan Police Force, did not provide data in response to the requests.

“I think the major challenge was the time [the investigation] took, and the perseverance, without knowing if it would lead to anything, as well as it being a

sensitive and emotional topic,” he said.

A roadmap published in October 2023 set out that Ofcom was planning on regulating “child safety, pornography and the protection of women and girls” in line with the Online Safety Act before Stockwell’s piece was published. However, the roadmap did not specifically mention dating apps, and instead mainly focused on pornography websites.

Now, the regulator has published specific guidance stating that “user-touser services” (including Grindr and all similar dating apps) likely to be accessed by children must conduct a children’s risk assessment, and implement more robust age verification methods. This guidance must be implemented by July 2025.

Mr Stockwell said: “Some people looked at the investigation and wondered why it focused on Grindr, but our pieces hopefully showed that LGBTQ+ children can be affected in a different way to straight children. It showed that we need age appropriate spaces for people coming to terms with their sexuality.

“There’s something powerful about

knowing that [the piece] was the front page in supermarkets and corner shops across the country. It might lead parents to ask their child questions that they wouldn’t have done before, and might give validation to LGBTQ+ children.”

Mr Stockwell credits his time at City St George’s with providing him with the crucial self-belief he needed to carry the investigation over the line. He said: “Our tutors instilled the confidence in each of us that if you have an idea and you put in the effort and the time, you will be able to carry it through.”

Richard Danbury, the MA Investigative Journalism course director, added: “I always tell students on my pathway not to think of themselves as students. It’s like being on a work placement and instead of asking to shadow someone, asking yourself what you’re able to contribute to the organisation.

“I love it when they then go on and do well. It makes the whole job and its frustrations worthwhile.”

Mr Stockwell is now freelancing at CNN, focusing on human rights stories, and recent projects have included reporting on the Israel-Gaza war and on LGBTQ+ issues in Afghanistan. He is keen, however, to continue with more work closer to home.

“These stories need to be told so we don’t get apathetic, even if they are already known about in the background. It’s about ensuring that people know these stories don’t just happen abroad or in wartorn countries, they happen on our doorstep,” he said.

Islington Guided Walks have teamed up with Podcasting MA students at City St George’s to create a four-part podcast that aims to revive passion for local history in young people.

“When someone says, ‘Let’s go on a tour,’ a lot of younger people aren’t interested in it [and] think it sounds really boring,” said Jane Parker, tour guide and co-ordinator at Islington Guided Walks.

“We’re looking at making something more appealing to young people and widen our audience,” she added.

Clerkenwell and Islington Guided Walks have been operating for 37 years, but it’s the first time they’ve collaborated with students. The podcast will aim to bring a modern take to local history, focusing on themes of food and drink, diversity, women, and literature.

Jane Parker added: “A lot of what we do as guides is research. It’s like climbing up a tree, you go up one branch and find another. So I threw this idea to the students about sleuthing, and acting as an investigator.

“I’ve lived here for 35 years and find

something new every day. It’s all there; it’s just waiting to be found out.”

Melusi Ncala, one of the students involved in the collaboration, shared what he’d learned about Islington as an international student: “It’s got a long, illustrious history, and is now quite a transformed space.

“The creative process of making podcasts is really what fuels me. It’s been both fun and challenging, especially because I’m working on something that will be used.”

By Zahra Onsori

Toxic beauty standards and the pressures of online perfection are the focus of journalist Ellen Atlanta’s bestselling book, recently released in paperback form.

then we end up in four-hour conversations where everyone is crying. Beauty is linked to our relationships with food, family, sex, and pleasure – it’s not trivial.”

The book dives into the complex

provided by Kathryn Vann

Pixel Flesh has received praise, with activist Gina Martin calling it ‘a brilliant clarion call for better’ and author Chloé Cooper Jones describing it as ‘an essential mirror reflecting the profound impact of

The University’s ‘Wall of Fame,’ which showcases journalism alumni, has been given a rebrand to mark the department’s 50th anniversary. The wall, opposite AG35 in the journalism department, will honour some of City St George’s’ alumni for their achievements in the industry.

Dr Glenda Cooper, Head of the Journalism Department, said: “I want our students to look at the wall and see people from different backgrounds, different times at City, who’ve gone to be successful in a variety of careers – and feel inspired to know they can do the same.”

The wall’s revamp, which is being coordinated by Jo Payton, Associate Dean of Student Experience, will reflect the diversity of the University’s alumni.

Dr Cooper added: “The journalism industry still has a long way to go when

it comes to diversity and we’ve already discussed how this issue will be key to our 50th birthday commemorations. We want to challenge the industry and address what needs to be done, and what our role can be in this.” More than 6,000 City St George’s alumni now work in newsrooms worldwide; the university ranks first in the UK for journalism, according to the Guardian University Guide in 2023.

Dr Cooper shared that they have already inducted some recent alumni into the new ‘Wall of Fame.’ These include Kira Richards, BA Journalism class of 2023, now Assistant Project Editor at National Geographic Traveller (UK), and Mariam Amini, MA Magazine Journalism class of 2024, a freelance journalist who has written for publications like Middle East Eye and The Guardian

By Kathryn Vann

Astudent from the MA Magazine course won this year’s Student Journalist of the Year prize at the prestigious PPA Next Gen Awards. This is the 16th time in the last 17 years that a student from the MA Magazine course at City St George’s has been awarded the title.

Ceci Browning, who is now Assistant Literary Editor at The Times, said: “It was so nice to be recognised by the PPA for the writing I did during my time at City.

“The investigative piece I wrote as my final project was on a topic totally alien to me – a worrying increase in the popularity of direct cremations – but I think that including it in the portfolio I submitted was a good way of proving journalistic curiosity to the judges.”

Other stories in Ms Browning’s portfolio included an interview with actor Callum Turner and a lifestyle piece for The Times

The award ceremony champions ‘30 of the most exciting rising stars in the UK publishing and specialist media sector’. The Student Journalist award celebrates journalists who ‘showcased exceptional work during their studies’.

At the last ceremony, the prestigious achievement went to alumnus Daniella Clarke, now a sub-editor at Hearst UK.

The ceremony was held on 17 October at the Mondrian Shoreditch hotel. The highly anticipated guest speaker of the event was Kenya Hunt, Editor-in-Chief of ELLE UK.

Other alumni that received awards included James Riding (Chief Reporter, Inside Housing) and Georgia Aspinall (previously Senior Editor, now Acting Assistant Editor at Grazia)

By Marissa Goursaud

Two former students from City St George’s return to teach at the university where they started their journalism careers.

Kath Melandri, who was formerly a programme director at University of the Arts London, has taken over as the new head of undergraduate journalism.

Ms Melandri, who is a cover presenter for BBC Radio London, said the role of Programme Director for BA Journalism at City St George’s, was “a wonderful

opportunity” she could not turn down. An alum of the Broadcast Journalism Diploma course at City St George’s in 1996, she added: “This September it would be 30 years since I studied here, so it felt like a really big circle closing.

“I’m very driven by talking to people. One of the things I enjoy the most is finding a stranger and discovering what makes them tick.”

She aims to inspire her students with her

Data journalism, how to pitch stories, and podcasting are among a new series of journalism courses currently in development at City St George’s.

Structured to equip journalists with in-demand skills, the courses will range from single-day workshops to full-term programmes. They will be open to a broad audience, from aspiring journalists to working professionals looking to upskill, and will be taught by a mixture of journalism staff and visiting lecturers.

Holly Shiflett, Director of Educational Enterprise, said: “The journalism department is wanting to be responsive all the time. We’re constantly asking, ‘What does the industry need? What do students need?’ Short courses can be built quickly and made very topical, based on what’s happening in the industry.”

Unlike traditional degree programmes, most short courses are ungraded and do not require formal assessments. Participants will receive expert-led instructions and feedback without the pressure of exams.

They will also offer prospective journalism degree students the chance to experience the department at City before committing to longer programmes of study.

As part of the University’s commitment to lifelong learning, the School of Communication & Creativity plans to expand these offerings in response to industry and student needs.

“We want to be part of students’ lives before they arrive, while they study, and after they graduate,” said Ms Shiflett. “Whether you’re looking to build a career or simply develop new skills, there’s something here for everyone.”

By Romy Journee

love for storytelling and help them understand the joy of broadcasting. “Working with the next generations of the best broadcasters and journalists around the country is wonderful,” she said.

Additionally, Ms Melandri is currently guiding third-year students through their final multimedia news day. “Their dedication and growth has been incredible,” she said. “I might cry when I say goodbye to them.”

Another former alum from the Newspaper Diploma, Raekha Prasad, has begun supervising the MA Magazine final year projects. The former foreign correspondent for The Times and feature writer for The Guardian joined the journalism department in 2024 teaching news writing, UK media, journalism history and culture, and journalism ethics for undergraduates.

Previously teaching at Goldsmiths, University of London for five years, Ms Prasad said, “It’s important to be clear about what story you’re telling, before you start writing.”

By Isha Khan and Yasmine Medjdoub

Over £3.7m has been allocated to the merger of City, University of London with medical school St George’s, a Freedom of Information request has revealed.

Between February 2024 and February 2025, £3,709,659 has been set aside to cover a variety of merger-related expenses. Of the sum, just under 45 per cent has been spent on the creation of a Merger Office. Other high expenses have included over £500,000 on estates and nearly £350,000 on branding.

Merger-related costs are still ongoing as City St George’s continues to implement changes, including the university’s marketing, student/staff email addresses, and replacing signs.

By Romy Journee

Historic pub’s licence reviewed after noise disturbances and anti-social behaviour complaints

By Hannah Bentley

The Sekforde, a beloved 196-yearold pub popular with journalism students and staff, has won its latest licensing battle, securing its future with new restrictions amid ongoing disputes over noise and outdoor drinking.

The Victorian Grade II listed drinking establishment, located on Sekforde Street in Clerkenwell, faced potential closure after neighbours complained of customers blocking pavements, loud music, intimidation and egg throwing.

During a meeting with Islington

that could be opened, leading to poor ventilation inside the venue during summer months.

In the latest licensing meeting, chaired by councillor Heather Staff, the open window ban was lifted, but an acoustic curtain, a roped-off outdoor area, a 9pm door closure, and a door supervisor on busy nights were imposed.

After the five-hour session at Islington Town Hall, the landlord, Harry Smith, said he was “pretty happy” with the outcome.

He added: “I’m glad we’re still allowed to have people outside, and that the licensing board agrees with us about the windows. The demarcated area will reduce outdoor space and it’s unclear whether our chair licence will change, but we were expecting a compromise.”

Mr Smith defended the pub alongside The Sekforde’s licensee David Lonsdale, and architect Chris Dyson, who restored the building in 2018.

Complainants testified anonymously from a separate room – an unusual move that former barrister, Mr Lonsdale, called “highly irregular”. Their accusations, broadcast via video call to the main town hall, ranged from persistent noise disturbances to incidents of harassment that required police involvement.

Testimonies in support of the pub came from local office workers, couples who had booked the venue for wedding receptions, and Sekforde employees. Each speech was met with applause.

One supporter, a resident of Sekforde Street for over 30 years, said: “What’s this obsession with vertical drinking?

From bushtucker trials to camp fall outs, Loose Women’s Jane Moore chats with Clara Taylor about her time surviving the jungle

The prospect of a one-month paid holiday in Australia would, for many, be the trip of a lifetime. With the added complication of some bushtucker trials where you may have to snack on a kangaroo’s unmentionables or be locked in a chamber filled with creepy crawlies, you might see some resistance. But not for Loose Women’s Jane Moore.

After over four decades working in journalism, holding positions at The Sun, This Morning, The Andrew Marr Show, and now as anchor on ITV1’s Loose Women, in December Moore agreed to compete in the 24th series of I’m a Celebrity Get Me Out of Here. Despite a bustup about the washing up, Moore greatly enjoyed the experience. She speaks to XCity about her time in the jungle.

C: What made you agree to I’m a Celeb?

J: They’ve asked me before, but the timing has never been right – I was either working full time or with young children. This year everything just aligned, so I went for it!

C: How did you find it adapting from the pace of journalism to a remote jungle?

J: It was one of my favourite parts of the experience. I slept like a baby. It was like living in a meditation app with the sound of the creek and the trees. You literally have nothing to worry about other than keeping the fire alight.

C: Did you find the other contestants were willing to open up to you as a journalist?

J: I was wary of people thinking “she’s a journalist, she’ll stitch us up”. After three or four days, we started to have little chats and got on really well. I think quite quickly people realised that I’m just a normal person.

C: Do you think your curiosity as a journalist played a role in helping the public understand the group better?

J: I think that’s the reason they asked me on the show. Production can get frustrated when there are great stories to tell but they don’t come out because no one is asking the right questions.

[N.B. the reported £100k appearance fee may have also been persuasive].

C: Were you worried about the transition from presenting on TV to being a reality TV contestant?

I’m used to live television and having my wits about me, but I’m more wary of prerecorded shows. You have to be careful either way, but it’s so much easier for things to be taken out of context or edited when they’re pre-recorded.

As a journalist, you’re inherently interested in other people but you need to be a good listener. Like the conversation I instigated with Danny Jones from McFly about his anxiety. He said that he’d never really talked about it and that I’d got him to open up.

C: Did it ever feel strange learning things about your campmates that you’d typically be encouraged to report on?

J: I’m not that kind of journalist. I’d never betray someone’s trust. If it hasn’t appeared on the show, there’s a reason for that. To everybody’s credit, they never once said to me “I hope you don’t write about that”.

It’s not new to me either. Dame Barbara Windsor, for example, was a great friend of mine, and I was one of the very few people who knew she had Alzheimer’s before it was made public. In the end she actually asked me to write the story because I could control the story. But I would have never betrayed her trust and reported on it without her express permission or wishes.

C: Were you able to switch off the part of your brain that is thinking about how you’d report on what was being said in the jungle?

J: I was aware of what would make the newspapers but I know the others felt similarly because there are cameras everywhere. That said, I still managed to switch off and be present.

Although Moore was the first to leave, she has no regrets about her time in the jungle. “I’m at a time in my life where I’m just trying to say yes to as much as possible”, she says. Perhaps it’ll be Dancing on Ice next.

Bossy boots? Crybaby? A narcissist who spent too much on a suit? Hattie Birchinall flips the gendered cultural dialogue by asking male-identifying journalists life’s most important questions – the ones they’re never asked

When you look at your body, how does it make you feel?

I have concerns over body image. I always have been a large man but I’m in the gym four times a week. I don’t always like what I see in the mirror. But I think I’ve made an accommodation with who I am. That said, there are certain TV jobs I don’t want to do because I don’t want to have to watch myself.

Can you think of an example when someone might have made you feel guilty or ashamed about how or what you’re eating? No, because I refuse to feel guilty about food; I think guilt is insidious. I have been raised to laugh in the face of it. I’m regularly asked what my guilty pleasure is around food and I refuse to answer that. You can try your bloody hardest, but it will tell me more about you than it does about me.

Would you describe yourself as bossy?

I am a control freak of my own working life. The idea of being late is utterly appalling to me. I remember taking a train to Yorkshire once, I got off without taking my suitcase with me and it undermined my very sense of self.

Can you tell me what your most expensive pair of trousers is? I got a pair of boring formal black trousers made for me by a great tailor; they cost £420. The trousers are extremely uncomfortable. He made exactly what I asked him to make. The fact is, I was an idiot. I thought I needed a formal pair of black slacks, because sometimes I think, “God, you’re a man of 58 still wearing jeans, shouldn’t you grow up? But I just don’t like wearing those kinds of trousers.”

How do you balance having such a successful career and a family?

I deliberately went freelance when my first child was born 11 years ago. It involved taking a horrific pay cut and surrendering all stability in my life, economic and otherwise. But it felt like this invaluable thing would be missed if I didn’t.

My partner is also a freelancer, and between us, there is this weird juggle of parenting kids who have social lives and activities with deadlines and multiple projects on the go at once.

I think if one of us was in a more traditional job, this would be really difficult.

Have you ever felt a sense of guilt when you travel for work?

Definitely. I followed a decommissioned oil rig around the world – I visited it in a scrapping yard in Eastern Turkey about eight weeks after my son was born and I was in Scotland trying to get on board right before he was due.

That was a real period of fear and guilt that I was going to miss the birth. And then afterwards, guilt that I wasn’t there to help at one of the most demanding moments in all of parenting, which is when a second newborn comes into the mix. My wife had to handle that (not especially cool).

Have you ever cried at work?

Yeah. I’ve had visible displays of emotion that wouldn’t be strictly professional. But it was honest in the moment, it was real.

Interviewing can be very intense, especially faceto-face. You try and hold yourself together because it’s important that you do, but it’s not always possible. Sometimes, it’s good for everyone if you are honest about how you’re responding to someone’s story.

Have you ever felt pressured to look a certain way?

Sometimes, working for glossy magazines, I feel I’m expected to look a certain way. There is enormous value in coming into things casually dressed because you don’t want to put your interviewee on edge. You want them to trust you in some way – you’re asking them to let you into their lives.

Channel 4 sports correspondent

What is your skincare routine before you go on camera?

I don’t want to sound arrogant… I don’t have many great qualities, but I do have good natural skin so I don’t actually require that much of a routine.

I wash my face at least twice a day. I try to cream my face every morning and night. Something that people don’t understand about having good skin, especially with your face, is that you need to look after your hair – your hair needs to be cleaned and well-oiled, especially black hair. If you look after your hair, your skin will look good as well.

What’s your go-to wardrobe choice when you need to look confident but approachable?

I’m a confident person, and I think that comes from how I carry myself and how I talk to people as opposed to, “he’s wearing that, so therefore he’s in a confident mood today”.

When you look at your body, how do you feel?

Not great. But whether you’re skinny or fat, it’s not going to define your day-to-day. What’s more important is your respect for people and your generosity. I’m trying not to let it consume me but it’s really difficult.

Channel 4 presenter

How do you balance having a successful career and a family?

As a typical bloke, I didn’t really think about what it would be like when my first daughter was born. From the moment I saw her curly black mop of hair popping out, I didn’t want to be the same person I had been before, who was always putting work first.

But I had two stingy weeks off which was the allocation before shared parental leave.

The unspoken reality is that there are a gazillion broken relationships in broadcast journalism because there is a direct conflict between getting exclusives and having a family life.

Do you ever worry that being too passionate about a story might make people think you’re too emotional for this job?

That gets beaten out of you as a news journalist. I’m making a film at the moment about the upsetting revelation that both sides of my ancestry - Nigerian and American - were involved in enslavement. I don’t want to do that story as a journalist, I want to do that as myself, which makes it not a news story. It has become a good outlet for me to explore my emotions in a world of storytelling where I’m not allowed to let my emotions play a role.

Have you ever cried at work?

Watching films, I’m a blubbering wreck. But I don’t at work.

I’ve been deeply moved and affected. I’ve interviewed people who’ve experienced the most awful things – their children being murdered, survivors of abuse – but there is a shield, a veneer of professionalism.

If you’re a regular person who absorbs the news, what do you do with that negative energy? Where does it go? There is something about the processing of emotion that happens when it is your job to tell a story.

Tiago Ventura interviews Olga Rudenko, editor of The Kyiv Independent, as she reports on the tumultuous first one hundred days of Donald Trump’s presidency

November 5: Donald Trump is re-elected as President of the United States

I remember waking up and checking The New York Times, seeing the headline: “Trump heads for the win”. I wasn’t surprised – this was the outcome I had expected.

At this point, I still saw Donald Trump as a wild card. His statements were not pro-Ukraine and sometimes even leaned pro-Russia. However, many people believed he could benefit Ukraine, as his arch-enemy was China. The thinking was that in trying to weaken China, he would also weaken Russia.

Every day at 10am, we hold a team check-in meeting

in our newsroom. Most people were in the office, some joined online. The team is made up of Ukrainians though we have several Americans working with us.

I knew the mood of the meeting would be sour. Some would be disappointed, others anxious about what this meant for Ukraine. That morning, my focus was not on what this meant for Ukraine, but how to talk to my team about it.

As a Ukrainian, after the past three years, I have learned to handle everything with a dark, sarcastic, often dry humour. It has helped us cope to this point. So, I opened the meeting with one of my many variations of “Well, this is the end of the world” jokes. The Ukrainians on my team smiled; the Americans did not.

The day after the election, we received a flood of emails from readers, especially Americans, concerned about what Trump’s re-election meant for Ukraine. Our newsletter has over 16,000 subscribers, and our community management team suggested we send a special update. The message was straightforward: based on Trump’s past statements, we had concerns, but we would report on his presidency as fairly as we would any other. We would not jump to conclusions, nor would we engage in activism – we would remain journalists, watching closely what he said and did in relation to Ukraine and Russia. At the same time, we acknowledged our readers’ concerns and stood in solidarity with them. It was one of the hardest things I’ve had to write.

December 18: Keith Kellogg appointed as Trump’s envoy to Ukraine

In the newsroom, there was some disappointment, but nothing too strong. By this point, you become somewhat numb to news coming from America. I commissioned an in-depth analysis of what Kellogg’s appointment meant for Ukraine.

At the time, the outlook seemed optimistic. The administration appeared to be moving towards providing security guarantees, which was, seemingly, a positive sign for Ukraine.

January 27: United States Agency for International Development (USAID) is shut down

February 18: Trump says Ukraine “should have never started” the war

It was the start of

an insane sequence of events. I was baffled by Trump’s continued “bromance” with Putin. What was he getting out of publicly fawning over him?

This all unfolded in the evening for us. Our news team worked frantically, updating statements and coverage. Because of the intensity, even one of our deputy editors jumped in to assist the news team.

Trump said Ukraine “should have never started” the war and called Zelensky a “dictator”.

“AS A UKRAINIAN, AFTER THE PAST THREE YEARS, I HAVE LEARNED TO HANDLE EVERYTHING WITH DARK, SARCASTIC, OFTEN DRY HUMOUR”

hit Ukrainian media hard. We are lucky to be one of the only independentlyfunded media outlets in the country, but others were devastated. Some lost 90 per cent of their funding overnight. All projects stopped immediately. Even if funds had already been transferred to bank accounts, they could not access them. Outlets couldn’t pay salaries; they couldn’t do anything.

We had planned a screening of a documentary on Russian war crimes at the American House in Kyiv, a cultural space funded by the US government. It was cancelled due to the shutdown of the entire system.

That day, we published a major piece focusing on the aid freeze’s impact on Ukrainian NGOs, covering war relief efforts, bomb shelters, schools, and the media.

I wrote an op-ed explaining how foreign aid works. There is a misconception that US-funded media isn’t independent, but that isn’t true. These grants come with no editorial control. They fund free journalism, allowing independent media to function in a country where selfsustainability is nearly impossible due to the war. Foreign aid was their lifeline.

Some accused me of being too harsh on Trump. Ironically, the op-ed begins by acknowledging his claims that he would end the war immediately upon taking office.

I remember that day vividly – a facepalm moment. The President of the United States spreading blatant lies about my country. I have criticised Zelensky, and I will continue to do so, but he is not a dictator, and Ukraine did not start this war.

The question was: how do we respond? A fact-checking piece? A broader analysis? We debated how to cover Trump without allowing him to dictate the news cycle. His strategy is to throw out so many statements that he dominates the agenda. So, we had to think carefully.

The next morning, our audience development manager checked Google Trends. The top search in the US was: “Who started the war in Ukraine?”

You think, “How can they be asking that?” But then you realise, if people are searching for it, they don’t know the answer. A team member suggested we replicate those words in our headline, “Who started the war in Ukraine?” Then, when you open the piece, the whole story is: “Russia”.

It was one of my favourite pieces. It became our mostread piece of the week. Thousands of people subscribed to our site after reading it. The story was picked up by European and Canadian media.

As a journalist, I will not advocate for a person or ideology. Yet, starting to doubt who began the war in Ukraine is an assault on truth and facts. I will advocate for my country and for the truth.

February 28: Zelensky nightmare press conference at the White House

This took everything to another level. It was a Friday night, and we were all still in the office.

As the meeting between Zelensky and Trump unfolded, I turned to my team and said, “Oh my God, they are fighting live in the Oval Office.” Everyone gathered to watch. We were sitting there with our hands in our heads in disbelief.

It was really shocking. We know Trump is not a fan of Zelensky or Ukraine, still watching this was insane. Berating a president like that, with the cameras at the Oval Office, was unthinkable. When people say this meeting changed global diplomacy forever, I think they’re right.

“MY WORK FROM THE PAST THREE YEARS WAS CRUMBLING IN FRONT OF MY EYES”

We had access to a Ukrainian TV station’s live YouTube stream before major networks picked it up. This meant we could publish our coverage 30 minutes ahead of major outlets.

At 8pm we published a main piece covering the argument.

That week, we had already drafted an editorial, directed at the American public, urging them to support Ukraine. But with the Oval Office confrontation, it became irrelevant. That night, I poured myself a glass of whisky and rewrote it, focusing on the meeting. The new version, published at midnight, was read by over 100,000 people.

I remember thinking, “what does this mean for Ukraine?”