BUESO-INCHAUSTI & REIN ARQUITECTOS 1983-2011

DISEÑO Y MAQUETACION • DESING AND LAYOUT BUESO-INCHAUSTI & REIN ARQUITECTOS

GONZALO NIETO

FABRICIO CORDIDO ANDRÉS F. MARTÍNEZ

FOTOGRAFÍA • PHOTOGRAPHY BUESO-INCHAUSTI & REIN ARQUITECTOS ARCHFRAME.NET RADUGROZESCU.COM

IMPRESIÓN • PRINTED ARTES GRÁFICAS PUNTO VERDE

ISBN: 978-84-615-2993-3

DEPOSITO LEGAL: M-37059-2011

© BUESO-INCHAUSTI & REIN ARQUITECTOS S.L.P.

Apolonio Morales 23, 28036, Madrid. España. www.buesoinchausti-rein.com

estudio@buesoinchausti-rein.com

T: +34 91 345 85 40

F: +34 91 345 55 94

BUESO-INCHAUSTI & REIN ARQUITECTOS 1983-2011

Apolonio Morales 23, 28036 Madrid. Spain www.buesoinchausti-rein.com estudio@buesoinchausti-rein.com

INDICE CONTENTS PRÓLOGO • PREFACE 5 RAFAEL DE LA-HOZ 6 CARLOS LAMELA 10 ENRIQUE SOBEJANO EQUIPO • TEAM 12 14 PROYECTOS • WORKS 17 ESTUDIO BUESO-INCHAUSTI & REIN ARQUITECTOS, MADRID 18 VIVIENDAS PASEO DE LA HABANA 187-189, MADRID 26 CASA BUESO. I - G. AGEA, LAS ROZAS 32 VIVIENDAS BARÓN DE LA TORRE, MADRID 40 EDIFICIO DE OFICINAS MENÉNDEZ PIDAL, MADRID 50 CASA VILLALÓN, SANTANDER 54 VIVIENDAS UNIFAMILIARES LÍGULA, MADRID 60 CASA REIN-SOLA, TORRELODONES 72 EDIFICIOS ESADE, MADRID 76 RESIDENCIAL PASEO DE LA HABANA 173-177, MADRID 84 EDIFICIO BALUARTE, MADRID 98 RESIDENCIAL FRANCISCO SUÁREZ, MADRID 102 RESIDENCIAL CONDES DEL VAL, MADRID 112 RESIDENCIAL CASTELLANA-PINAR, MADRID 122 EDIFICIO ALIUS, LAS ROZAS 138 EDIFICIO RESIDENCIAL AVERESCU, BUCAREST 154 EDIFICIO M-50, LEGANÉS 162 EDIFICIO AAYLEX, BUCAREST 170 EDIFICIO V.B. LANDTRADE, SANTANDER 176 EDIFICIO TAMBRE, MADRID 184 TORRES FLOREASCA, BUCAREST 188 EDIFICIO FLOREASCA 210, BUCAREST 198 EDIFICIO RESIDENCIAL DANTE, BUCAREST 204 EDIFICIO RESIDENCIAL NUEVA ZELANDA, MADRID 208 EDIFICIO RESIDENCIAL SANTOS, MADRID 216 CONCURSO COLEGIO ALEMÁN, MADRID 222 CONCURSO CENTRO CULINARIO, SAN SEBASTIÁN 230 EDIFICIO RESIDENCIAL ARAVACA, MADRID 238 CONCURSO NUEVA SEDE IBERIA, MADRID 244 EDIFICIO RESIDENCIAL PRADILLO, MADRID 252 CONCURSO GOLF LA MORALEJA 260 APÉNDICE CRONOLÓGICO • CHRONOLOGICAL APPENDIX 267

PREFACE PRÓLOGO

EL

ARQUITECTO TOTAL

RAFAEL DE LA-HOZ ARQUITECTO

Para llegar hasta el castillo hay que ascender por las empinadas callejuelas de un pueblo tan griego que recuerda a los de Andalucía y que la guía que llevo conmigo, describe como mediterráneo y cubista. Me detengo a descansar un rato y pienso que un arquitecto diría otra cosa, pero no le entendería nadie, porque cuando un arquitecto describe también pontifica. Es evidente que hay muchas diferencias entre las casas con patio de la campiña andaluza y las casas con terrazas de una ladera griega y también que lo de mediterráneo y cubismo es un lío de estilos y cosa de Perogrullo, pero hay que ver lo bien que lo entienden los turistas.

Este prólogo a la obra de Bueso-Inchausti & Rein, comienza como ven con el firme propósito de seguir el ejemplo de las guías turísticas, pero como la “cabra tira al monte”, me temo que tarde o temprano terminaré por caer en la tentación de pontificar, por lo que es más que posible que no se entienda nada. La culpa no será mía porque el que pide prólogos debe saber donde “pone la Era”. Mientras desvarío con estas cosas, los turistas que “pasan” del pueblo y su arquitectura me adelantan veloces a la búsqueda de postales y refrescos. Por mi parte voy buscando las cuestas abajo y la sombra como aprendí de chico en esos pueblos de Andalucía que al parecer tanto se parecen a éste. Aquí también toman el fresco a la puerta de sus casas, pero no porque sean mediterráneos y cubistas, sino porque dentro no hay quien viva y prefieren disfrutar de la terraza del vecino a soportar la casa propia.

Hace siglos algún General veneciano, decidió que este monte era el lugar militarmente idóneo para colocar un castillo y aquí sigue, pero en ruinas. También están las casas que crecieron a su sombra. Minúsculas, porque una ladera deja poco sitio, y sofocantes porque empotradas contra esa ladera, no pueden tener tampoco ventilación cruzada. Su interior está electrodomesticado con neveras y televisiones, y son de un tamaño tan desproporcionado que no queda sitio para nadie. Pienso en el General veneciano y en su decisión de poner aquí el castillo y supongo que los del pueblo también se acuerdan de él, y de toda su familia. Hace mucho que ya no hay razón alguna ni siquiera militar para vivir parapetados en esta ladera, y sin embargo, aquí siguen sus habitantes, pagando cada día la hipoteca del lugar. Claro que tampoco a los venecianos les ha ido mucho mejor en esto de las hipotecas. Siempre que estoy en Venecia, me pregunto cómo debe de sentar por las mañanas tener que coger la góndola para ir al bar de la esquina en lugar de dar tres pasos como todo el mundo. Tal vez los venecianos no piensen mucho en ello, ni en el que inventó los canales. Tampoco los madrileños, a los que conozco mejor y que habitan resignadamente la capital y sus errores fundacionales, se acuerdan casi nunca de Felipe ni de su familia, en este caso Real. La arquitectura debería ser el arte, o el oficio o la habilidad o lo que sea, para que esto no ocurriera y que los griegos del Egeo no vivieran asfixiados en la terraza ajena, los venecianos pudieran caminar y los madrileños pasear, pero la realidad es que no sucede así. La arquitectura no garantiza la felicidad, pero puede amargarte un poco la vida. A los arquitectos nos encanta decir y a veces creer, que la buena arquitectura es una cosa estupenda y que todo el mundo debería saber apreciarla. Los seres humanos, por el contrario, piensan que la arquitectura puede ser bella o fea, pero que eso cambia poco sus vidas. La cosa no está tan clara y si no que se lo pregunten a los griegos del pueblo “mediterráneo y cubista” que viven colgados en una sofocante ladera. O a los que viven sin bajarse de un coche o una góndola.

Estoy seguro que ya habrán empezado a pensar que pontifico, advertidos estaban y posiblemente también pensarán que exagero, pero la arquitectura, efectivamente condiciona y mucho, la vida de los seres humanos, tanto cuando se elige donde poner la casa, como cuando se piensa donde poner la ciudad. Se ha repetido mucho –sobre todo en las escuelas de Arquitectura- que la primera acción arquitectónica de la humanidad al abandonar las cuevas prehistóricas fue la creación del plano horizontal, es decir construir una plataforma. Un plano sobre el horizonte que permitía caminar sin tropezar y sobre el que se podía edificar. Hace tanto tiempo que dejamos los arquitectos de tomar la decisión de dónde y sobretodo cómo debía ser ese plano que hemos llegado a creer que no es competencia nuestra. Cuando el arquitecto D. Juan de Villanueva recibió el encargo del que hoy es el Museo del Prado de Madrid, dejó escrito en la memoria del proyecto que “La sorpresa y desconfianza no dejó lugar alguno al gozo natural que todo profesor recibe en la comisión de asuntos de tales circunstancias poco comunes”.

¿Y cuál era esa sorpresa que no dejaba a D. Juan disfrutar de la alegría de un encargo de tanta importancia? Él mismo nos lo aclara:

“Aumentose mi confusión al saber que mis ideas debían ceñirse al sitio ya elegido y comprado, en que ninguna acción había tenido y en cuya adquisición no dudo ocurriesen razones que no es correspondiente a mi alcance el medirlas ni considerarlas pero sí debí inmediatamente hacerme cargo de su extensión y posición, midiendo y proporcionando a ella mis ideas”. Cuanta frustración se percibe en las palabras del Maestro, al saber que sus ideas debían ceñirse al sitio que ya había sido elegido y como se lamenta de que “el plano horizontal”, el plano con su “extensión y posición” no fuese competencia suya. La decisión de dónde y cómo construir no antecede a la arquitectura, sino que es parte indisociable de la propia arquitectura. El olvido, la ignorancia y la negligencia a lo largo de un tiempo secular de esta evidencia sustrajo de la práctica arquitectónica, competencias y responsabilidades. Tantas y hace tanto, que los propios arquitectos han llegado a la conclusión de que no son de nuestra incumbencia o los más descuidados de que nunca fueron propias.

Cuando Frank Gehry fue invitado a Bilbao para realizar su exitoso proyecto del Museo Guggenheim que transformó la ciudad en un referente mundial, el lugar elegido era un almacén en el centro urbano conocido como La Alhóndiga. Tras una rápida inspección Gehry concluyó que Bilbao era una “ciudad ría” y que el edificio no debería estar donde se había planificado sino junto a esa ría que definía el carácter de la ciudad. Consiguió cambiar el emplazamiento y ya conocen el resultado. Hace falta mucha credibilidad, tesón y seguridad para lograr algo así, pero sólo los más inteligentes son conscientes de la transcendencia de traspasar los límites, y superar las imposiciones.

6

Asesores, gerentes, promotores, políticos, planificadores, agentes, urbanizadores y un largo etc. suplantan al arquitecto para tomar las decisiones más relevantes y que más condicionan el modo de vida. Solo los más dotados, visionarios y valientes arquitectos tienen el talento y capacidad necesarios para romper el cerco y crear una arquitectura con huella. Para mí Sacha Bueso es uno de esos arquitectos totales. Ya sé que muchos piensan que ser arquitecto al mismo tiempo que financiero, planificador, gestor y constructor, entraña unos riesgos extraordinarios y no sólo en lo económico, sino que la necesaria libertad creativa –la imaginación- del arquitecto resulta incompatible con tan pragmáticas actividades y que prosistas que sean poetas hay muy pocos. No les falta razón. En su fantástica obra “La personalidad creadora” Maslow mantiene que es muy difícil encontrar personas capaces de acceder simultáneamente a los dos registros básicos del cerebro, la intuición y la razón. Cerebros capaces de compatibilizar sueño y realidad. Ocuparse de las cosas de palacio como Aposentador Real por las mañanas y por las tardes pintar “Las Meninas”, está al alcance sólo de los genios duales como Velázquez. Los que en arquitectura están capacitados para hacer tal cosa – y son pocos – pueden acceder a campos de acción únicos y exclusivos que les permite “romper el molde” hacia una arquitectura más libre e innovadora. Una arquitectura cuyos escasos ejemplos han transformado por ejemplo la ciudad de Madrid, lo que demuestra que bastan unos pocos si se sabe seguir su ejemplo.

Hacia 1920 Madrid no había superado los límites de su ensanche del siglo XIX cuando dos jóvenes arquitectos, Luis Blanco Soler y Rafael Bergamín decidieron “elegir plano horizontal”. Encontrándose en la situación natural del joven arquitecto, es decir sin trabajo, estudiaron, eligieron y arriesgaron por si solos. Tras obtener los terrenos en aportación y los créditos avalados, levantaron lo que hoy es posiblemente la zona de la ciudad de mayor prestigio y calidad residencial: La Colonia de El Viso. Setenta años después, Madrid acometió un nuevo proceso de crecimiento pero esta vez quienes estudiaron, eligieron y arriesgaron fueron los agentes urbanizadores anteriormente mencionados. El resultado de un tamaño mucho mayor que la Colonia del Viso pasó a ser conocido como los PAUS. Les invito a que comparen la calidad de planeamiento, arquitectura y vida de lo que fue hace casi un siglo una modesta colonia para profesionales con uno de estos deslumbrantes nuevos planteamientos realizados con un gran equipo y ni un solo arquitecto total. Confío en no molestar a nadie ni que la comparación resulte impertinente.

Entre El Viso y los PAUS, Madrid tuvo de nuevo la suerte de contar con otro de estos superdotados de Maslow y cuando a mediados del siglo XX, J.M. Ruiz de la Prada comprendió que sometido a las directrices de los agentes, su arquitectura o su idea no sería capaz de adaptarse, reunió a un grupo de amigos y tomó la iniciativa. Libre de consejeros y ataduras planificó, financió, dibujó y construyó la serie de edificios que llevan su nombre y supusieron la creación de un nuevo tipo residencial de tan altísima calidad que pasó a ser paradigma del bloque entre medianeras del barrio de Salamanca, contraviniendo de paso el postulado moderno de que sólo en la tipología de vivienda social puede realizarse procesos de investigación e innovación arquitectónica. Hoy ambos ejemplos pasan desapercibidos y parecen evidentes, casi como una consecuencia de su tiempo, pero sin la autonomía conquistada su obra habría sido inviable.

Ejerciendo un control de proceso que está en la tradición y origen de la arquitectura como disciplina y en la de colegas que le antecedieron, Bueso-Inchausti & Rein ha creado un nuevo tipo de arquitectura residencial de un gran valor y calidad en Madrid. Tanto que constituye un nuevo ejemplo y referente como heredero único y legítimo de los Blanco Soler y Ruíz de la Prada. Decía antes que no basta saber elegir y que son muchos los prosistas y pocos los poetas y me gusta pensar que también en esto la arquitectura de Bueso-Inchausti & Rein establece una continuidad en la tradición madrileña. La tradición como concepto recibe un trato desigual por parte de arquitectos y críticos. Para algunos constituye el referente del que emana su teoría arquitectónica, para otros simplemente representa un pasado que hay que superar y en ocasiones mejor olvidar. No queda más remedio, me temo, que volver al famoso aforismo de D’Ors de que “todo lo que no es tradición es plagio”. Paradoja maravillosa que sin duda envidiarían Chesterton y Wilde y expresa insuperablemente la evidencia de que todos los que presumen de creaciones originales y que nada les antecede, en realidad lo que están haciendo es plagiar. No citaré ejemplos porque éste es un prólogo cordial y mi lista de enemigos suficientemente amplia. Toda creación emana de la tradición y los que la utilizan como refugio para legitimar su obra simplemente plagian. Sólo los que la utilizan como origen de un nuevo principio lo evitan.

La arquitectura de Bueso-Inchausti & Rein tiene su origen en la de Blanco Soler o Ruiz de la Prada en lo que se refiere al modo de hacer, o proceso y una continuidad que se origina en la de Javier Carvajal o en la de Eleuterio Población en lo que resulta más formal y material.

Dicen los entendidos que cuando la idea arquitectónica es poderosa e innovadora, cuando su fuerza supera lo convencional, resulta un tanto irrelevante que esté mal construida. Como si la imperfección material pusiera por contraste más en evidencia el insólito valor de la idea.

Tal vez suceda así en alguna ocasión, pero la obra que recoge este libro confía más en los procesos manufacturados y la calidad constructiva, que en la mitificación de la imperfección o, lo que es peor, la chapuza. La imperfección material es patrimonio de los arquitectos artistas, pero no forma parte de los atributos del arquitecto total. Es imposible encontrar en la obra de Bueso-Inchausti & Rein un encuentro, un detalle, una solución que resulte descuidada, olvidada, falta de criterio e integración en el concepto total del proyecto. En realidad se podría afirmar que Bueso-Inchausti & Rein hace sinécdoques arquitectónicas y que no utiliza la tradición como excusa para legitimar lo que hace sino como referente de un nuevo principio.

Termino mi paseo y también este prólogo sin haber subido al castillo ni aportado mucho a la introducción de una obra que deslumbra tanto como el “talento total” de sus autores y que no precisa de introducciones. Me queda la preocupación de cuál será el futuro de esta arquitectura tan mediterránea y cubista como mal situada y muy poco por la de Bueso-Inchausti & Rein que no sólo ha dejado ya su huella indeleble sobre el plano de Madrid sino que tiene además perfectamente planificado un prometedor futuro que este libro anuncia.

7

THE TOTAL ARCHITECT

RAFAEL DE LA-HOZ ARCHITECT

To reach the castle, I have to climb up the steep alleyways of a town so Greek, it calls to mind those of Andalusia and which the guide I have describes as Mediterranean and Cubist. I stop to rest a while and think that an architect would say otherwise, but nobody would understand him, because when an architect describes, he also pontificates. There are obviously many differences between the houses with courtyards in the Andalusian countryside and the terraced houses on a Greek mountainside. Equally obvious is that this talk of the Mediterranean and Cubism is a hodgepodge of styles and a truism, but oh how well tourists understand it!

As you can see, this preface to the work of Bueso-Inchausti & Rein starts out determined to follow the example of a tourist guide, but since old habits die hard, I’m afraid that sooner or later I’ll end up succumbing to temptation and pontificating, meaning it’s quite likely you won’t understand anything. I won’t be to blame because anyone asking for a preface knows what he’s in for. While I ramble on about these things, tourists who skip the town and its architecture rush past me in search of postcards and refreshments. Me, I search for downhills and shade, something I learned as a child in those Andalusian towns that are apparently so similar to this one. People here also sit in the shade on their stoops, but not because they’re Mediterranean or Cubists, but because inside it’s unbearable and they’d rather enjoy their neighbor’s terrace than put up with the house itself.

Centuries ago some Venetian general decided that this hill was an ideal location, from a military standpoint, for a castle, and it’s still here, albeit in ruins. The houses that were built in its shade are also here, tiny though they are, since a hillside leaves little room, and stifling, as being lodged into the mountain rules out any cross breeze. Their interiors are outfitted with refrigerators and televisions, though their size is so disproportionate that there’s no room for any people. I think about the Venetian general and his decision to build a castle here, and I suppose that the townsfolk also remember him, and his entire family. There have been no good reasons, military or otherwise, to live perched on this hillside in ages, and yet here remain its inhabitants, paying their mortgages on the place every day. Of course, Venetians haven’t fared much better with this whole mortgage business. Whenever I’m in Venice, I ask myself what it must be like to have to catch a gondola in the morning to go to the corner bar instead of walking a few steps, like everybody else. Maybe Venetians don’t think about it much, or about the guy who invented the canals. Nor do the residents of Madrid, whom I know better and who resign themselves to living in the capital with its foundational mistakes, hardly ever remember Philip or his family, in this case, a royal one. Architecture should be the art, or the trade or skill or whatever, that keeps this from happening so that Aegean Greeks don’t have to live crammed against their neighbor’s terrace, Venetians can walk, and madrileños can go for a stroll, but the reality is otherwise. Architecture doesn’t guarantee happiness, but it can sour life a bit. We architects love to say, and sometimes believe, that good architecture is a wonderful thing and that everyone should learn to appreciate it. Human beings, on the other hand, think that while architecture can be beautiful or ugly, it does little to change their lives. But it’s not that simple, and if you don’t believe me ask the Greeks in the “Mediterranean and Cubist” town who live perched on a suffocating hillside. Or those who live without getting out of a car or gondola.

You’ve undoubtedly started to think that I’m pontificating, but you were forewarned. You’re possibly also thinking that I’m exaggerating, but architecture does in fact condition people’s lives, and a great deal, both when choosing where to build a house and where to found a city. It’s been said many times, especially in architecture schools, that mankind’s first architectural activity upon leaving the prehistoric caves was to create a horizontal plane, that is, to build a platform. A plane on the horizon that allowed them to walk without tripping and on which to build. We’ve been letting architects decide for so long where, and especially, how that plane should be, that we’ve concluded that it’s not our domain. When the architect Juan de Villanueva was commissioned to build what is now the Prado Museum in Madrid, he wrote in the project’s report that “the surprise and mistrust left no room for the natural joy that every teacher feels when undertaking affairs under such unusual circumstances.”

And what was the surprise that kept Don Juan from taking pleasure in the joy of such an important responsibility? He himself explains:

“My confusion grew upon realizing that my ideas were bound by the site already chosen and purchased, in whose acquisition no doubt there were factors at play that it is not my place to measure or consider, though I immediately had to take charge of its extension and position, adapting to it and providing my ideas.” The sense of frustration in the Master’s words is evident, knowing that his ideas had to conform to the already chosen site and lamenting how the “horizontal plane,” the plane with its “extension and position,” was not his responsibility. The decision regarding where and how to build does not predate architecture; rather, it is inseparable from architecture itself. The forgetting, ignorance and negligence of this evidence over time sapped competencies and responsibilities from the practice of architecture. So many and so long ago that architects themselves have reached the conclusion that they are not our concern, with the most careless thinking that they never were.

When Frank Gehry was invited to Bilbao to carry out his successful Guggenheim Museum project, which transformed the city into a global landmark, the site chosen was a downtown warehouse, La Alhóndiga. After a quick inspection, Gehry concluded that Bilbao was an “inlet city” and that the building should not be where it had been planned, but next to that inlet that defined the city’s character. He succeeded in changing the location, and we all know the result. Achieving something like that requires a lot of credibility, tenacity and assuredness, but only the smartest people are aware of the importance of surpassing boundaries and exceeding requirements.

8

Advisors, managers, developers, politicians, agents, urban planners and many others supplant the architect in order to make the most relevant decisions, those that most condition our way of life. Only the most gifted, visionary and brave architects have the talent and skill needed to break the mold and create unique architecture. For me, Sacha Bueso is one of those total architects. I know that many think being an architect while doubling as a financier, planner, manager and builder entails extraordinary risks, not only in financial terms, but in having the architect’s creative freedom – their imagination – be incompatible with such pragmatic endeavors, and that masters of all trades are scarce. And they couldn’t be more right. In his marvelous piece The Farther Reaches of Human Nature Maslow maintains that finding people who can simultaneously access the brain’s two basic registers, intuition and reason, is very difficult. Brains capable of harmonizing dream and reality. Taking care of palace business as Royal Chamberlain in the morning and painting Las Meninas in the evening is within the reach of only dual geniuses like Velázquez.

Those in architecture who are skilled enough to do this – and there are few – have access to unique and exclusive areas of activity that allow them to “break the mold” toward freer and more innovative architecture. An architecture whose few examples have transformed, for example, the city of Madrid, proof that a few people will suffice if their example is followed.

In 1920, with Madrid still firmly entrenched within its 19th century boundaries, two young architects, Luis Blanco Soler and Rafael Bergamín, decided to “choose a horizontal plane.” Finding themselves in a situation typical of young architects, that is, unemployed, they studied, chose and risked by themselves. After obtaining contributed properties and securing bank credit, they built what is today quite possibly the city’s most prestigious residential area: La Colonia del Viso. Seventy years later, Madrid underwent a new growth process, though this time the people studying, choosing and risking were the aforementioned urban planners. The result, much larger in area than La Colonia del Viso, came to be known as the PAUS. I invite you to compare the quality of the planning, architecture and life of what was a modest colony for professionals almost a century ago, with that of one of these shining new layouts conceived by a huge team without a single total architect. I trust I won’t step on any toes with this, or that the comparison will not be considered uncivil.

Between El Viso and the PAUS, Madrid was fortunate to have available another of Maslow’s geniuses when, in the mid20th century, J.M. Ruiz de la Prada, realizing that his architecture or ideas would be unable to adapt to the directives of planners, gathered a group of friends and seized the initiative. Free from advisors and constraints, he planned, financed, drew and built a series of buildings that bear his name and that represented the creation of a new residential unit so high in quality that it became the paradigm for infill sites in the neighborhood of Salamanca, in the process transgressing the modern belief that only social dwellings lend themselves to architectural research and innovation projects. Today both examples go unnoticed and seem obvious, almost a consequence of their time, but without the resulting autonomy, his work would have been unviable.

By exerting control over a process that is part of the tradition and origins of architecture as a discipline, and of the colleagues that preceded them, Bueso-Inchausti & Rein have created a new kind of residential architecture in Madrid, one of great value and quality. So much so that it constitutes a new example and reference as the sole and legitimate heir of Blanco Soler and Ruiz de la Prada. I mentioned earlier that knowing how to choose isn’t enough, and that masters of all trades are few and far between. I like to think that in architecture, Bueso-Inchausti & Rein gives continuity to a Madrid tradition.

Tradition as a concept is treated differently by architects and critics. For some, it constitutes the reference from which architectural theory emerges. For others, it simply represents a past that must be overcome, if not entirely forgotten. We have no choice, I’m afraid, but to return to D’Ors’s famous aphorism that “whatever is not tradition is plagiarism.” A wonderful paradox no doubt studied by Chesterton and Wilde, and which expresses like no other the proof that all those who boast of original creations never before seen are in fact copying. I won’t cite examples because this is a cordial preface and my list of enemies is sufficiently ample. Every creation stems from tradition, and those who use it as a refuge to legitimize their work are simply copying. Only those who use it as the start of a new principle can avoid it.

The architecture of Bueso-Inchausti & Rein has its origins in that of Blanco Soler and Ruiz de la Prada in terms of its execution, or process, and a continuity that stems from that of Javier Carvajal or Eleuterio Población in its more formal and material aspects.

Connoisseurs say that when an architectural idea is powerful and innovative, when its strength exceeds the conventional, it’s somewhat irrelevant if it’s badly built. As if, in its contrast, the material imperfection spotlighted the idea’s exceptional merit.

It may happen like that on occasion, but the work described in this book relies more on manufactured processes and on quality construction than on mythicizing imperfection or, even worse, a botched job. Material imperfection is the stock in trade of artist architects, but it is not among the attributes of a total architect. You will not find in the work of Bueso-Inchausti & Rein one encounter, one detail, one solution that is careless, forgotten, lacking in judgment or in integration into the total project concept.

In reality, one might say that Bueso-Inchausti & Rein make architectural synecdoches and that they don’t use tradition as an excuse to legitimize what they make, but rather as a standard for a new beginning. Thus do I finish my walk, and this preface as well, without having either climbed to the castle or added much to the introduction of a work that dazzles as much as the “total talent” of its authors, and which needs no introduction. I remain concerned about the future of this architecture that is as Mediterranean and Cubist as it is badly situated, and not at all by that of Bueso-Inchausti & Rein, which has not only left its indelible mark on Madrid’s landscape, but whose promising future, as presented in this book, is perfectly laid out.

9

CARLOS LAMELA ARQUITECTO

Mi relación con el estudio Bueso-Inchausti & Rein, empieza mucho antes de que conociese a los hermanos Jorge y Sacha Bueso-Inchausti aprendiendo a esquiar en Francia, cuando yo estaba empezando Arquitectura. Hablamos de hace mucho tiempo. Corría el año 75 del siglo pasado y éramos todavía adolescentes…

Su tío, el arquitecto Julio Inchausti había sido compañero de ingreso en la Escuela de Arquitectura de mi padre, y conservaron gran amistad durante toda la carrera y su vida. Por ese motivo, mis padres conocían a Cristina, hermana de Julio y madre de Jorge y Sacha.

Cristina regentaba la librería de la Escuela de Arquitectura, cuando era únicamente un precioso mueble de madera muy moderno e ingenioso diseñado por el arquitecto Javier Carvajal, y que situado en pleno vestíbulo principal, permitía exponer libros durante el día, y cerrarse por la noche.

Creo que Cristina fue la primera persona que conocí en la Escuela, ya que nada más ojear el primer libro en plan novato, y decirle mi nombre, exclamó: ¡hijo de Antonio! A partir de ese momento, nuestra relación fue entrañable durante toda la carrera… Cristina era una mujer muy simpática y abierta, de enorme cultura, apasionada por la arquitectura y con un extraordinario sentido del humor, y mientras yo utilizaba su stand para curiosear libros, me hablaba de sus hijos, que pronto entrarían en la Escuela para forjarse como futuros arquitectos, al igual que su hermano Julio y mi padre Antonio lo habían hecho treinta años antes. Posteriormente, durante muchos años, he tenido la fortuna de disfrutar de la amistad de Jorge, Sacha y su esposa Gisela Toro. Pero vamos a hablar de arquitectura que es para lo que me han invitado generosamente.

Cuando en la década de los noventa, empezaron a aparecer unos edificios residenciales en Madrid, de magnífico diseño y muy bien construidos, y preguntaba quién eran los arquitectos o veía la placa, siempre eran de Bueso-Inchausti & Rein. Cada vez veía mejores edificios, y cada vez me gustaban más.

Las últimas realizaciones, tuve la suerte de conocerlas en detalle, desde dentro, y apreciar su excepcional calidad constructiva y arquitectónica centímetro a centímetro. Antes de ser invitado a escribir estas pocas líneas, ya he declarado públicamente, que han realizado la mejor arquitectura residencial española de las últimas décadas. Por su concepción, por su diseño y por su impecable ejecución.

Además, la visión de estos grandes arquitectos no se limita a ser simplemente arquitectónica, sino que el gran conocimiento que tienen de todo el proceso económico e inmobiliario, hace que el producto sea extraordinariamente relevante. Conocen la realidad como promotores, como constructores y como arquitectos, y son sobresalientes en todos los aspectos.

He disfrutado mucho con sus magníficos edificios y confío en seguir haciéndolo durante mucho tiempo.

10

LA EXCELENCIA DE UNA ARQUITECTURA IMPECABLE

THE EXCELLENCE OF AN IMPECCABLE ARCHITECTURE

CARLOS LAMELA ARCHITECT

My relationship with the Bueso-Inchausti & Rein studio goes back to long before I met brothers Jorge and Sacha BuesoInchausti learning to ski in France when I was beginning my studies in Architecture. We’re talking about a long time ago. That was back in ’75 and we were still teenagers…

Their uncle, the architect Julio Inchausti, had been a classmate at my father’s Architectural School, and they enjoyed a great friendship throughout their studies and their lives. This is how my parents knew Cristina, Julio’s sister and Jorge and Sacha’s mother.

Cristina was in charge of the book section at the Architectural School, when it was composed of nothing more than a beautiful piece of wooden furniture, modern and ingenious, designed by architect Javier Carvajal. Located right in the main hall, it exhibited books during the day and was closed up at night.

I think that Cristina was the first person I met at the School. I had no sooner begun to flip through the first book, like the neophyte that I was, when she exclaimed: “Antonio’s son!” From that very moment on we had a warm relationship throughout my studies. Cristina was a friendly and open woman who was very cultured, passionate about architecture, and had an extraordinary sense of humor. While I used her stand to browse through books, she told me about her sons, who would soon enter the school to be trained as future architects, just like her brother Julio and my father Antonio had done thirty years before. Later, for many years, I’ve had the good fortune of enjoying friendships with Jorge, Sacha and his wife, Gisela Toro. But what we are going to talk about architecture, which is what I have been so generously invited to speak of.

When in the decade of the 90s a series of residential buildings began to appear in Madrid, well-built structures featuring magnificent designs and, I asked who the architects were, or I read their plaques, and they were always by BuesoInchausti & Rein. I saw better and better buildings, which I liked more and more.

I was lucky enough to see their latest creations in detail, on the inside, and to be able to appreciate the exceptional quality of their construction and architecture, inch by inch. Before being invited to write these few lines I had already declared publicly that they have produced the finest Spanish residential architecture in recent decades. The finest in their designs and in their impeccable execution.

In addition, the vision of these great architects is not limited to the strictly architectonic sphere, but is an ample one which includes in-depth knowledge of the entire economic and real estate process, making their work especially noteworthy. They know the realities as developers, as builders, and as architects, and they are outstanding in all these aspects.

I have greatly enjoyed their wonderful buildings, and I trust that I will be able to continue to do so for a long time to come.

11

ELEGANCIA Y PRAGMATISMO

ENRIQUE SOBEJANO ARQUITECTO

La obra de Bueso-Inchausti & Rein constituye hasta cierto punto una singularidad en el panorama español reciente: es una arquitectura cuya razón de origen funcional o comercial no ha renunciado a la búsqueda de una calidad arquitectónica traducida en edificios que se distinguen por su elegancia y pragmatismo, conscientes siempre de su pertenencia a un tiempo y un lugar. No es muy común encontrar propuestas de vivienda privada realizadas en los últimos años poseedoras de la riqueza volumétrica, diversidad espacial y precisión constructiva que manifiestan sus proyectos. Sin duda la personalidad de Alejandro Bueso-Inchausti, caracterizada por una permanente curiosidad intelectual y voluntad de perfeccionamiento, está en el origen del afán de precisión formal y técnica que acaba reflejándose, como en un espejo, en sus propios edificios. Una primera lectura permite reconocer la coherencia y continuidad de una trayectoria apoyada en una confianza sin fisuras en los registros de la arquitectura moderna, caracterizada por la depuración de un lenguaje expresivo que ha ido generando lo que podríamos definir como un estilo propio, algo que no muchos arquitectos pueden, quieren o saben producir. La función como origen de la estructura formal, la nítida descomposición volumétrica de los distintos elementos, la contención en la paleta de materiales, son todos ellos invariantes que derivan de la tradición moderna internacional, filtrada en nuestro país a través de los maestros de la segunda mitad del siglo pasado. Contemplada en conjunto, su obra refleja la persistente reelaboración de un código de propuestas espaciales, soluciones constructivas y materiales paulatinamente transformadas en un lenguaje personal consolidado proyecto a proyecto, con el paso del tiempo.

Tras una ya extensa carrera basada en edificios de diversas escalas, en su mayor parte vinculados al uso residencial, su trabajo ha demostrado una madurez y calidad que destaca significativamente por encima de la inmensa mayoría de las obras que en los recientes años de bonanza económica han sido construidas por encargo de clientes o promotores privados. Conscientes de que la calidad arquitectónica y el pragmatismo no son conceptos contradictorios, sus modelos se remontan a la arquitectura norteamericana de los años 50, 60 y 70, que inspiró también a sus maestros en la Escuela de Madrid. En efecto, la obra de Mies van der Rohe, Richard Neutra, Gordon Bunshaft o Paul Rudolph encontraría eco en la generación de arquitectos como Sáenz de Oíza o Javier Carvajal, para los que aquellas experiencias americanas fueron referentes, no solo formales, como más bien técnicos, espaciales y constructivos, que en aquellos años suponían un reto a lograr con medios limitados en España. Bueso-Inchausti & Rein son herederos en cierto modo de esa misma tradición moderna: su obra - realizada en un contexto histórico, social y económico muy distinto- es portadora de una precisión formal y constructiva, una continuidad espacial entre el interior y el exterior y una expresividad material, que remiten tanto a los modelos norteamericanos originales como a la interpretación de las generaciones precedentes en nuestro país. Estos conceptos, que podríamos asociar a la obra de Mies, de Neutra y de Rudolph respectivamente, son reconocibles también en arquitectos admirados por Bueso-Inchausti & Rein -como Javier Carvajal- cuyos proyectos de vivienda se habrían de convertir en referencia consciente de la expresividad, el empleo de los materiales y el juego espacial de oposición entre elementos verticales y horizontales que configuran el lenguaje arquitectónico de muchas de sus obras.

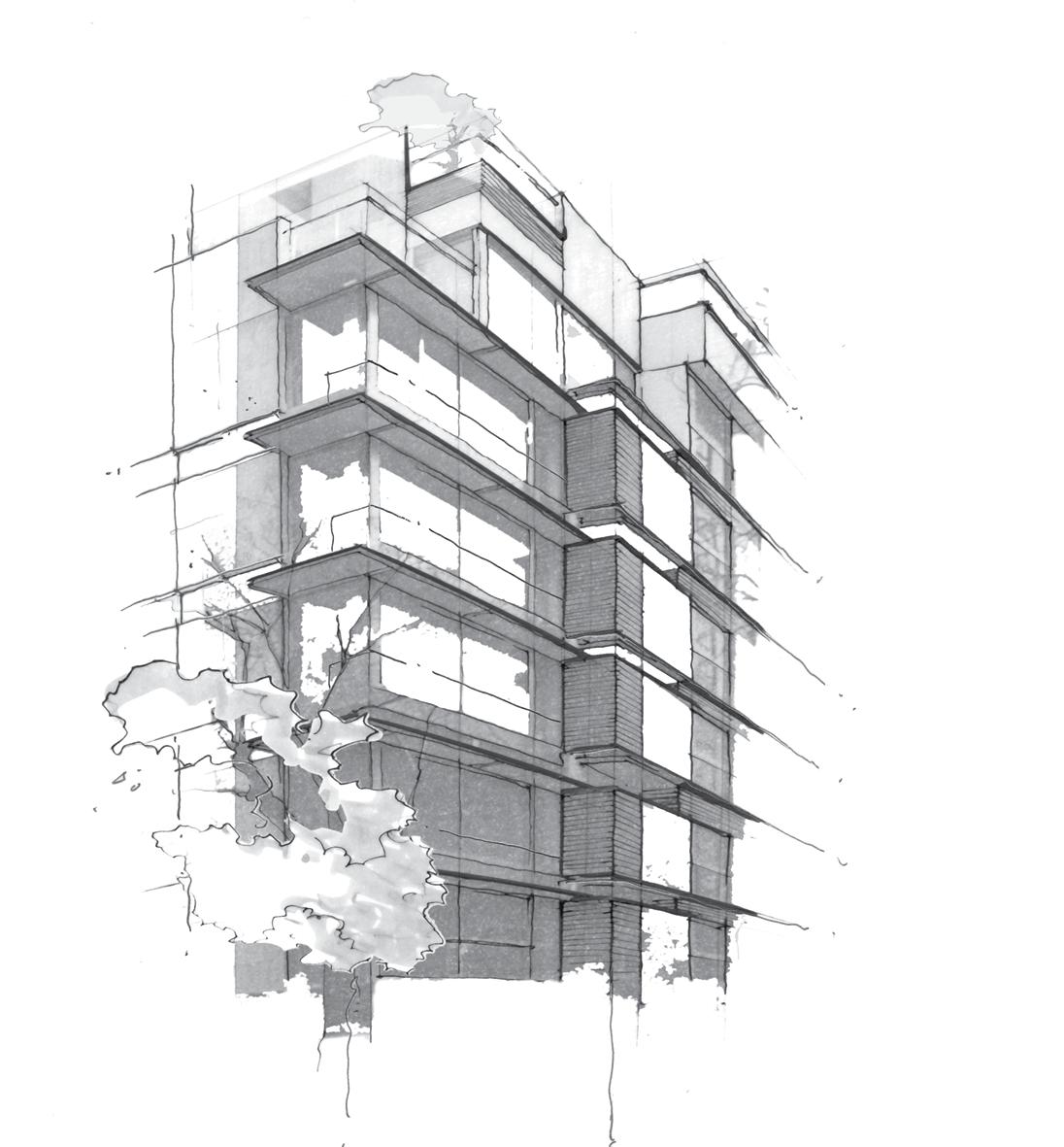

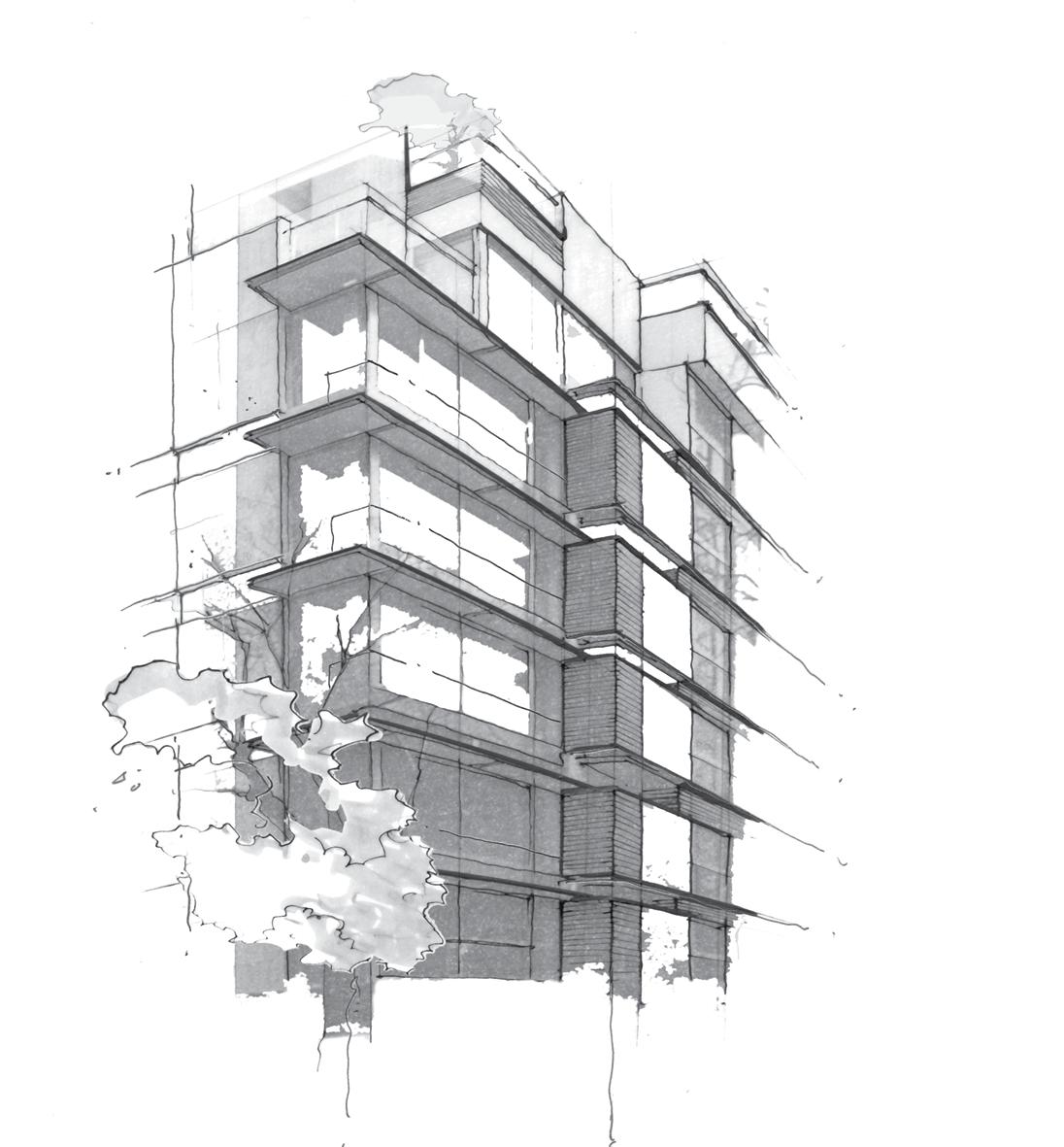

El pragmatismo y la elegancia que transmiten sus edificios, poco dados a experimentalismos o excesos formales, se transforman en una arquitectura consciente de su función y de sus usuarios a un tiempo que de su pertenencia a una herencia moderna compartida. En su obra más reciente coexisten proyectos de voluntad innovadora en la tipología residencial -sucesora en cierto modo del papel que Gutiérrez Soto o Ruiz de la Prada representaron en la evolución de la vivienda burguesa madrileña de las décadas precedentes- con recientes propuestas realizadas fuera de España que quizá hagan presagiar un salto de escala y contexto en la obra del estudio. Entre sus proyectos más personales, el edificio de Paseo de La Habana, que incluye la propia vivienda Bueso Inchausti-Toro, refleja tal vez mejor que ningún otro el carácter innovador de su arquitectura. Un edificio generado a partir de la adición y apilamiento de unidades de vivienda conectadas en distintos niveles, autónomas y diferentes entre sí, como complejo juego geométrico espacial donde el interior y el exterior se entrelazan constantemente, donde se materializa el espíritu optimista de la arquitectura del estudio. Por encima de otros compromisos o condiciones externas, las viviendas madrileñas son la expresión de una obra segura de sí misma, que domina las limitaciones que los programas funcionales y las necesidades del mercado parecen imponer a tantos otros arquitectos. En las obras de Bueso-Inchausti & Rein la arquitectura parece fácil y directa, transmite una confianza recobrada en la modernidad que hace tiempo que muchos otros olvidaron y que no hace sino confirmar que la buena arquitectura forma parte siempre de un proceso continuo, inseparable de su pertenencia a un tiempo y a un lugar.

12

ELEGANCE AND PRAGMATISM

ENRIQUE SOBEJANO ARCHITECT

The work of Bueso-Inchausti & Rein represents, to a certain extent, a unique phenomenon on the recent Spanish architectural scene: it is a body of work whose functional and commercial aspects have not led to the sacrifice of a search for quality, leading to buildings which stand out for their elegance and pragmatism, reflecting at all times a consciousness of their connection to their place and time. It is not common to find private residential projects completed in recent years with the volumetric richness, spatial diversity and constructive precision which their projects display. Without any doubt the personality of Alejandro Bueso-Inchausti, characterized by a permanent intellectual curiosity and desire for perfection, is the wellspring behind this drive for formal and technical precision which ends up being reflected, like a mirror in their buildings. A first examination allows one to recognize the coherence and continuity of a career grounded in a solid confidence in the principles of modern architecture, defined by the depuration of an expressive language which has gradually generated what we could define as a signature style, something which not many architects can, want or are able to produce. Function as the source of formal structure; a clean volumetric breakdown of the different elements; restraint in the range of materials employed…all of these are constants derived from the modern international tradition, filtered in our country through the masters of the second half of the past century. Viewed all together, their work reflects a persistent reelaboration of a series of special ideas, constructive solutions and materials gradually transformed into a personal language, consolidated project after project over time.

After an already extensive career based on buildings of different dimensions, mainly in the area of residential use, their work has demonstrated a maturity and quality markedly superior than the vast majority of projects which, during the recent years of the economic boom, were constructed by private clients and developers. Conscious of the fact that architectural quality and pragmatism are not incompatible concepts, their models go back to the American architecture of the 50s, 60s and 70s, which also inspired the masters of the Madrid School. Indeed, the work of Mies van der Rohe, Richard Neutra, Paul Rudolph and Gordon Bunshaft would be echoed in the generation of architects such as Sáenz de Oíza and Javier Carvajal, for whom those American experiences were reference points, not just formally but technically, spatially and in terms of construction, which during those years represented a challenge to achieve with Spain’s limited means. Bueso-Inchausti & Rein are heirs, in a certain way, to that same modern tradition: their work – carried out in a very different historical, social and economic context – reflects a formal and constructive precision, a spatial continuity between the interior and exterior, and a material expressiveness which harks back to both the American originals and to the preceding generation’s interpretations of them in our country. These concepts, which we could associate with the work of Mies, Neutra and Rudolph, respectively, are also recognizable in architects admired by Bueso-Inchausti & Rein, such as Javier Carvajal, whose residential projects would become model works, standing out for their expressiveness, their use of materials, and the way they play with space, creating contrasts between the vertical and horizontal elements making up many of their works’ architectural language.

The pragmatism and elegance which their buildings transmit, largely devoid of experimentation or formal excesses, lead to an architecture which is conscious of its function and its users, and its connection to a shared modern heritage. Their most recent work combines innovative residential projects (to an extent heirs to the roles which Gutiérrez Soto and Ruiz de la Prada played in the progression of bourgeoisie Madrid homes in the preceding decades) with recent work completed outside Spain which perhaps portends a shift in the scale and context of the studio’s work. Among their most personal creations, their building on the Paseo de la Habana, which includes the Bueso-Inchausti-Toro home, perhaps reflects better than any other the innovative nature of their architecture. The building is generated by the addition and stacking of residential units interconnected on different levels, autonomous and different from one another, a complex geometric and spatial exercise where interior and exterior are constantly interwoven, and where the optimistic spirit of the office. Above other commitments and external conditions, the Madrid homes are the expression of a body of work that is sure of itself and which transcends the functional programs and market needs which seem to hamper so many other architects. In the works of Bueso-Inchausti & Rein architecture seems easy and direct and transmits a newfound confidence in modernity which many lost some time ago,. Their work confirms the proposition that good architecture always forms part of a continuous process, inseparable from its connection to a time and place.

13

14

1983-2011

BUESO-INCHAUSTI & REIN ARQUITECTOS

ALEJANDRO BUESO-INCHAUSTI INCHAUSTI

Nace en Madrid en 1960.

Graduado en la E.T.S.A.M como Arquitecto en 1982. Master en Real Estate por la U. Politécnica de Madrid.

Alejandro Bueso - Inchausti born in Madrid in 1960. Graduated at E.T.S.A.M as an Architect in 1982. Master in Real Estate at the U. Politécnica de Madrid.

HISTORIA

PABLO REIN REDONDO

Nace en Madrid en 1960. Graduado en la E.T.S.A.M como Arquitecto en 1983.

Pablo Rein Redondo born in Madrid in 1960. Graduated at E.T.S.A.M as Architect in 1983.

El estudio de arquitectura Bueso-Inchausti & Rein fue fundado en 1983 por los arquitectos Alejandro Bueso-Inchausti, Pablo Rein y Jorge Bueso-Inchausti, socio hasta 2004. Desde entonces, el estudio ha venido desarrollando su actividad profesional de manera ininterrumpida tanto en España como internacionalmente. La actividad en España ha estado siempre muy vinculada a Inmobiliaria Tiuna, de la que desde 1989 es socio mayoritario.

HISTORY

The firm of Bueso-Inchausti & Rein Architects was founded in 1983 by Alejandro Bueso-Inchausti, Pablo Rein and Jorge Bueso-Inchausti, a member until 2004. Since then, the firm has consistently developed projects in Spain and abroad. The activity of the studio has always been linked to Inmobiliaria Tiuna, becoming its main partner in 1989.

EQUIPO ∙ TEAM

Alejandro Bueso-Inchausti ∙ Pablo Rein

Jorge Bueso-Inchausti ∙ Gisela Toro ∙ Kerstin Paessens ∙ Gonzalo Nieto ∙ Fabricio Cordido

Maximino Ramos ∙ Andrés F Martínez ∙ Elisa Iglesias ∙ Edgar Bueso-Inchausti ∙ Ignacio Larracoechea

Guillermo Fernández-Castañeda ∙ Paula Bueso-Inchausti ∙ Carmen Jorge ∙ Raúl Mariñez ∙ Patricia Reverte

Carlos Ruiz ∙ María Herranz ∙ Elizabeth Goncálves ∙ Yunes Mansilla ∙ Marius Trusca

Jaime Ingram ∙ Jesús Peinado ∙ J. Alberto Morasso ∙ J. Ignacio Morasso ∙ Irvis González

15

WORKS

PROYECTOS

BUESO-INCHAUSTI & REIN ARQUITECTOS 1983

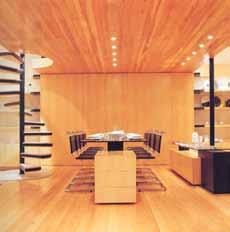

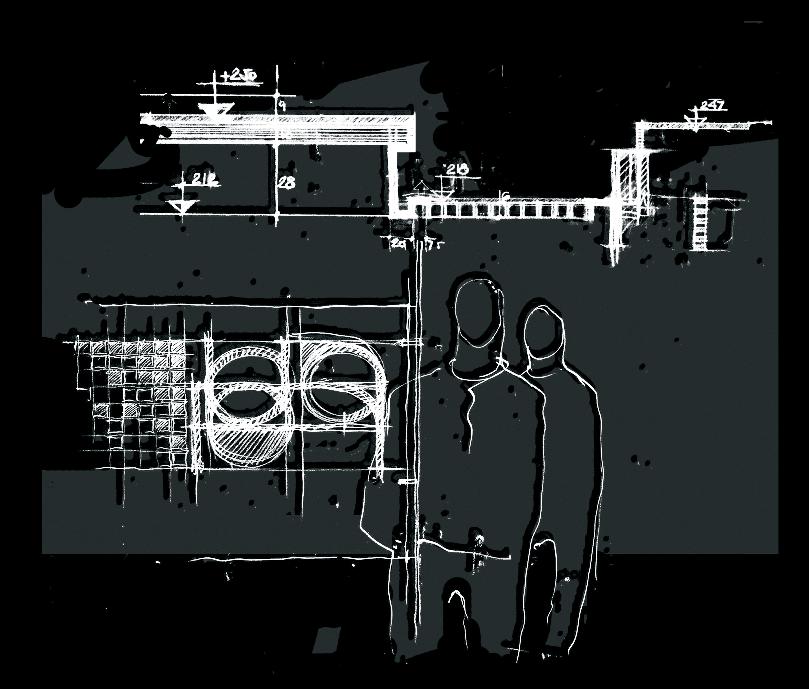

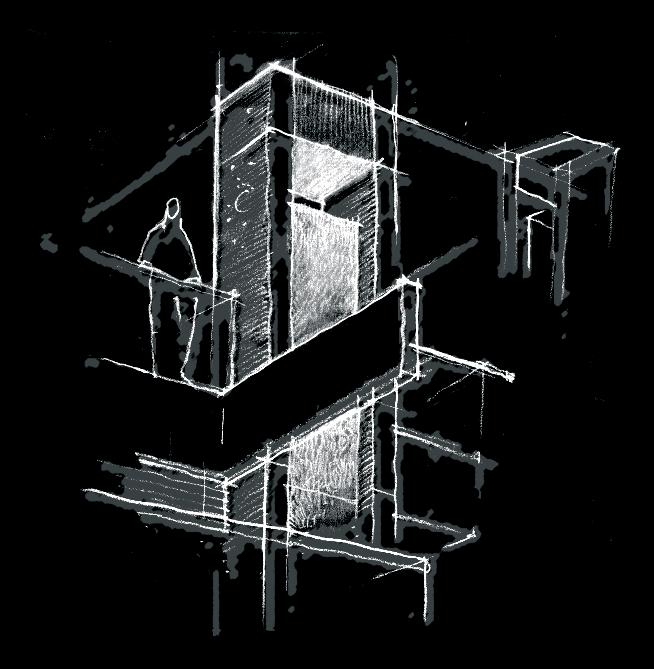

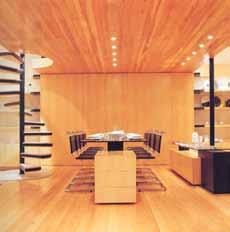

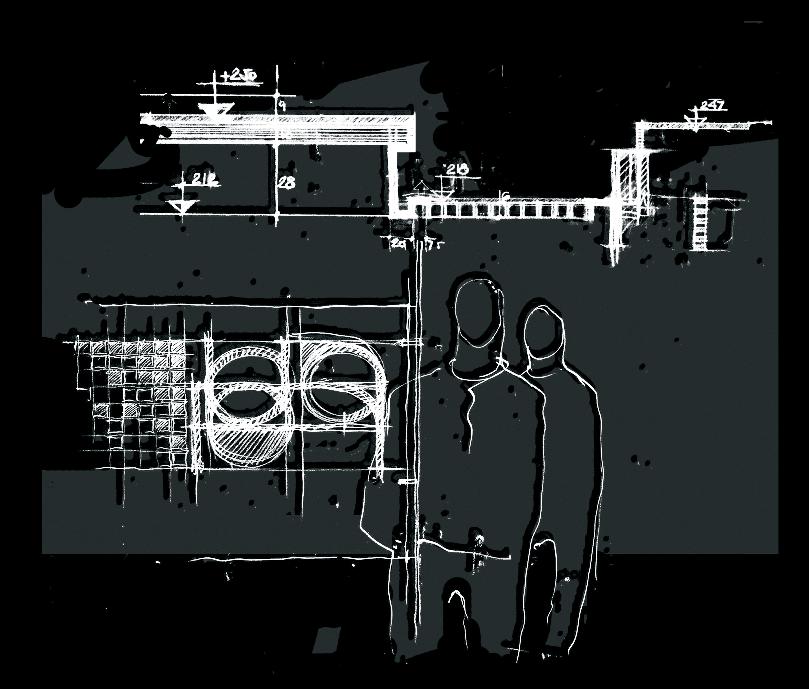

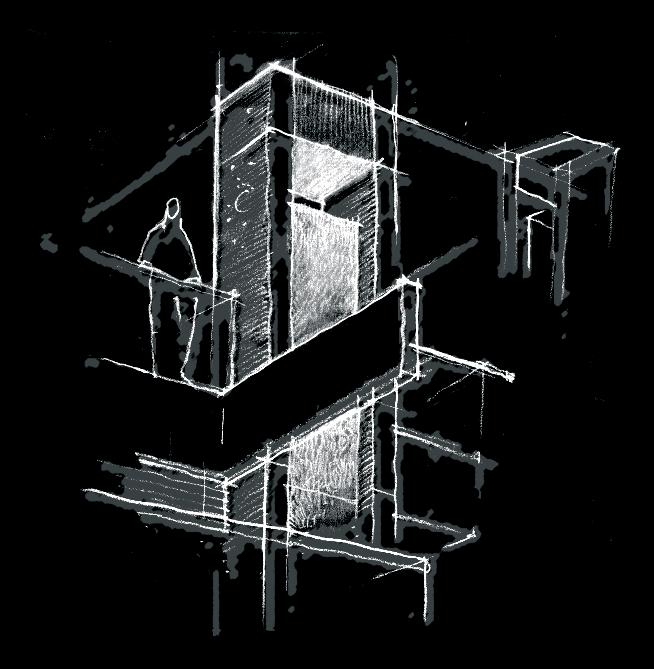

Incluir en un libro sobre obras del estudio el propio espacio de trabajo no tiene más finalidad que intentar trasmitir el ambiente en que se gestan los distintos proyectos. Entendiendo que por fuerza ha de haber una estrecha relación entre el ambiente de trabajo, el espacio que lo alberga y el fruto de ese trabajo.

El local del estudio, en su estado actual, se diseñó inicialmente en el año 1990 con objeto de vincularlo con las oficinas de la promotora que trabaja en exclusiva con el estudio. Si bien ha sufrido durante dos décadas varias adaptaciones hasta llegar a su configuración actual.

Se buscó crear un espacio abarcable visualmente en su totalidad, de acuerdo con el funcionamiento bastante “horizontal” e indiferenciado en sus funciones en que desemboca casi siempre el proceso creativo del trabajo en un estudio de arquitectura.

BUESO-INCHAUSTI & REIN ARCHITECTURAL 1983

Including the studio’s own working space in a book on its projects is only intended to transmit the atmosphere in which its different projects are born and nurtured, with the understanding that there must be a close relationship between work environments, the spaces they occupy and the work produced in them.

The current studio’s space was initially designed in the year 1990 in order to link it to the offices of the developer working exclusively with the studio, though over the past two decades it has seen various changes before adopting the design it features today.

It was sought to create an area that could be totally taken in visually as one space, with its uses undifferentiated, in accord with the integrated nature of the creative work undertaken in an architectural studio.

18

1983

MADRID

22

23

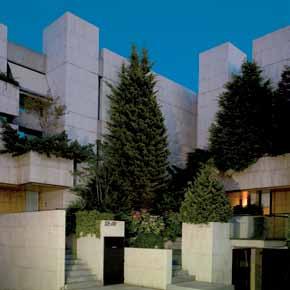

VIVIENDAS PASEO DE LA HABANA

187-189

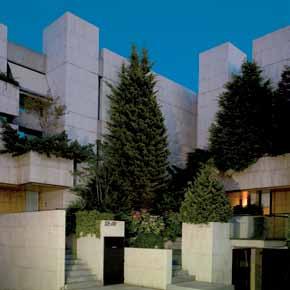

Fue para el estudio una obra muy importante por tratarse de la primera construida dentro del núcleo urbano de Madrid, y por lo tanto una obra de juventud de enorme valor sentimental.

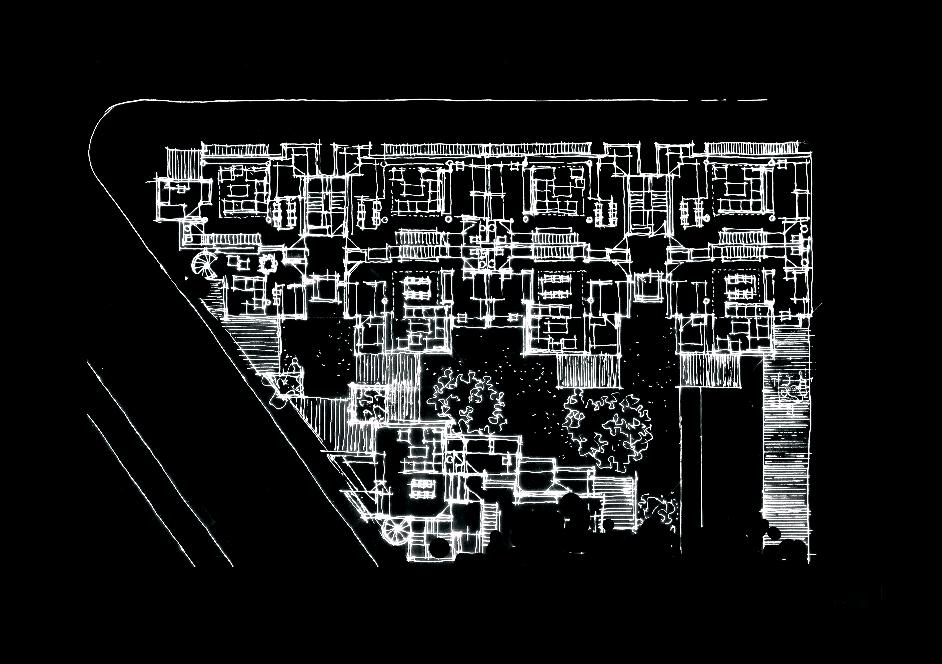

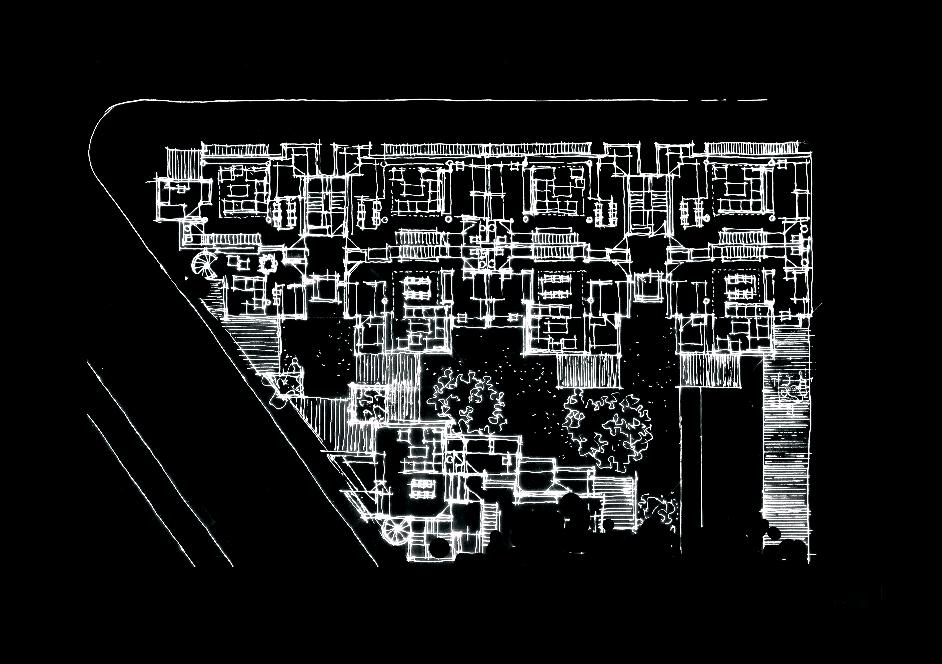

El conjunto es el resultado de dos proyectos distintos, que arquitectónicamente se trataron con carácter unitario. El primero cronológicamente se desarrolla en una franja estrecha de suelo que discurre paralela a la calle Mateo Inurria, vía de tráfico muy intenso. Para ello se negoció con el Ayuntamiento la creación de un espacio de circulación a dos niveles con un acceso único por Paseo de la Habana. El nivel inferior, de circulación rodada, se ilumina a través de huecos ajardinados que conectan con el nivel superior de circulación peatonal. De esta manera se protege del ruido la fachada norte, volcándose las viviendas sobre los jardines orientados a mediodía.

La segunda fase obedece a un planteamiento diferente, aunque con el mismo lenguaje arquitectónico. El escaso frente del terreno a la vía Pública, obligó a crear una calle de uso privado, desde la que se accede a las viviendas. La necesidad de diseñar varias alineaciones con distintas orientaciones nos llevó a tratar cada una de las viviendas, en contraste con el ritmo modular de las viviendas de la primera fase.

Los incrementos de volumetría ejecutados desordenadamente, han desvirtuado la obra, y a pesar de que consideramos la tipología impuesta por las ordenanzas poco acorde con el barrio, está bien integrada en el entorno y mantiene el espíritu con el que se construyó.

PASEO DE LA HABANA 187-189 TOWN HOUSES

This project represented a very important one for the studio, as it was the first completed in downtown Madrid and, as such, a job carried out an early stage and charged with enormous sentimental value.

The overall project is the result of two different ones, which from an architectural perspective, were dealt with as one entity. The first chronologically was developed on a narrow swath of land running parallel to Mateo Inurria Street, which features heavy traffic. Negotiations were carried out with City Hall to create a two-tiered space for traffic, with sole access from the Paseo de la Habana. The lower level, of traffic movement, is lit up through landscaped gaps connecting with the upper level, featuring pedestrian circulation. In this way the northern facade was shielded from noise, with the homes located over the southward-facing landscaped area.

The second phase was based on a different approach, although employing the same architectural elements. The limited amount of land near the street made it necessary to create a public access through which residents could reach their homes. The need to design various alignments with different orientations led us to address each one of the homes separately, in contrast with the modular approach employed on the homes in the first phase.

A series of volumetric increases have detracted the work. Even though we consider the typology imposed by city ordinances to be quite discordant in the neighborhood, it is well-integrated in the area and maintains the spirit in which it was built.

26 MADRID 1984 - 1988

28

PLANTA BAJA · GROUND FLOOR ALZADO · ELEVATION

30

MADRID 1986 - 1987

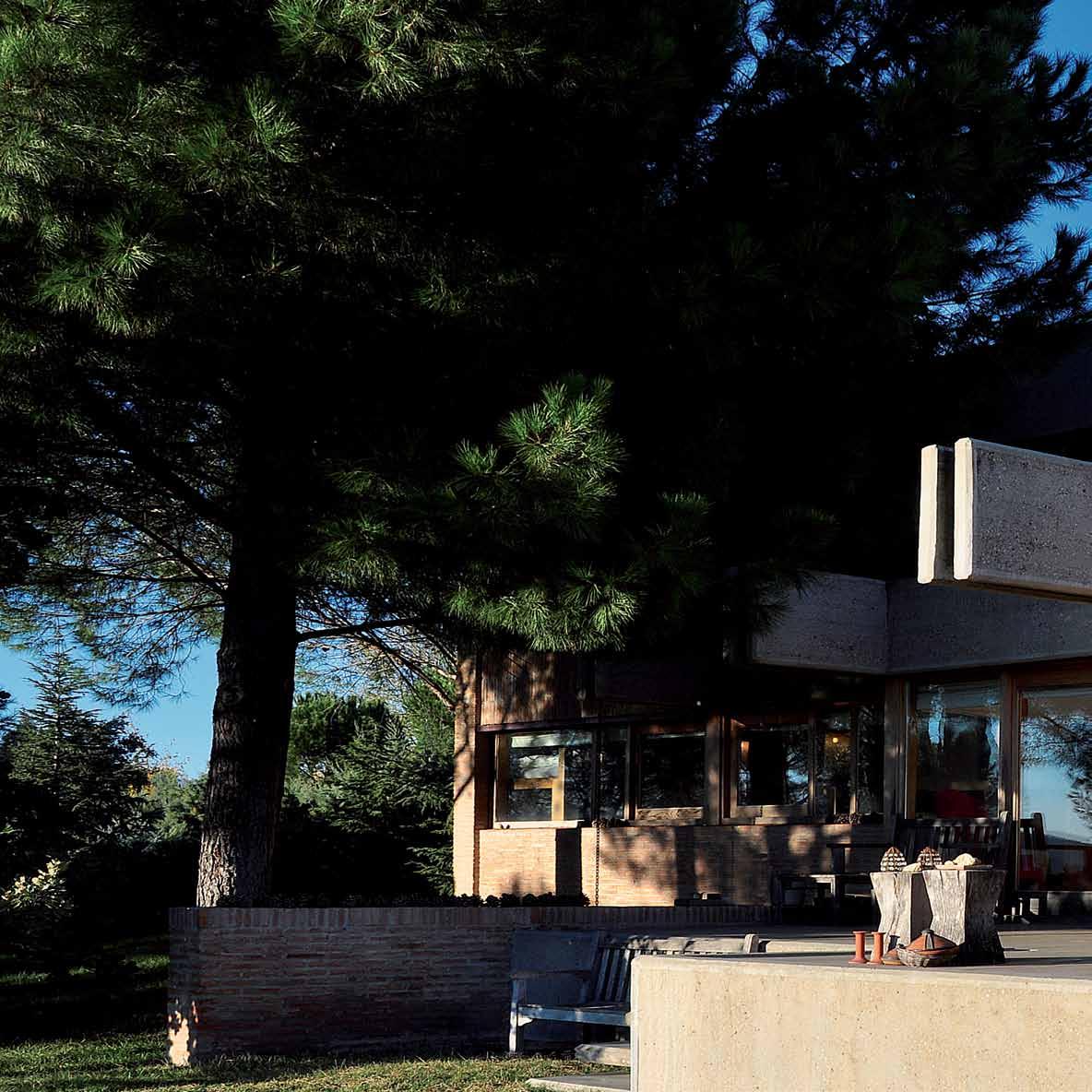

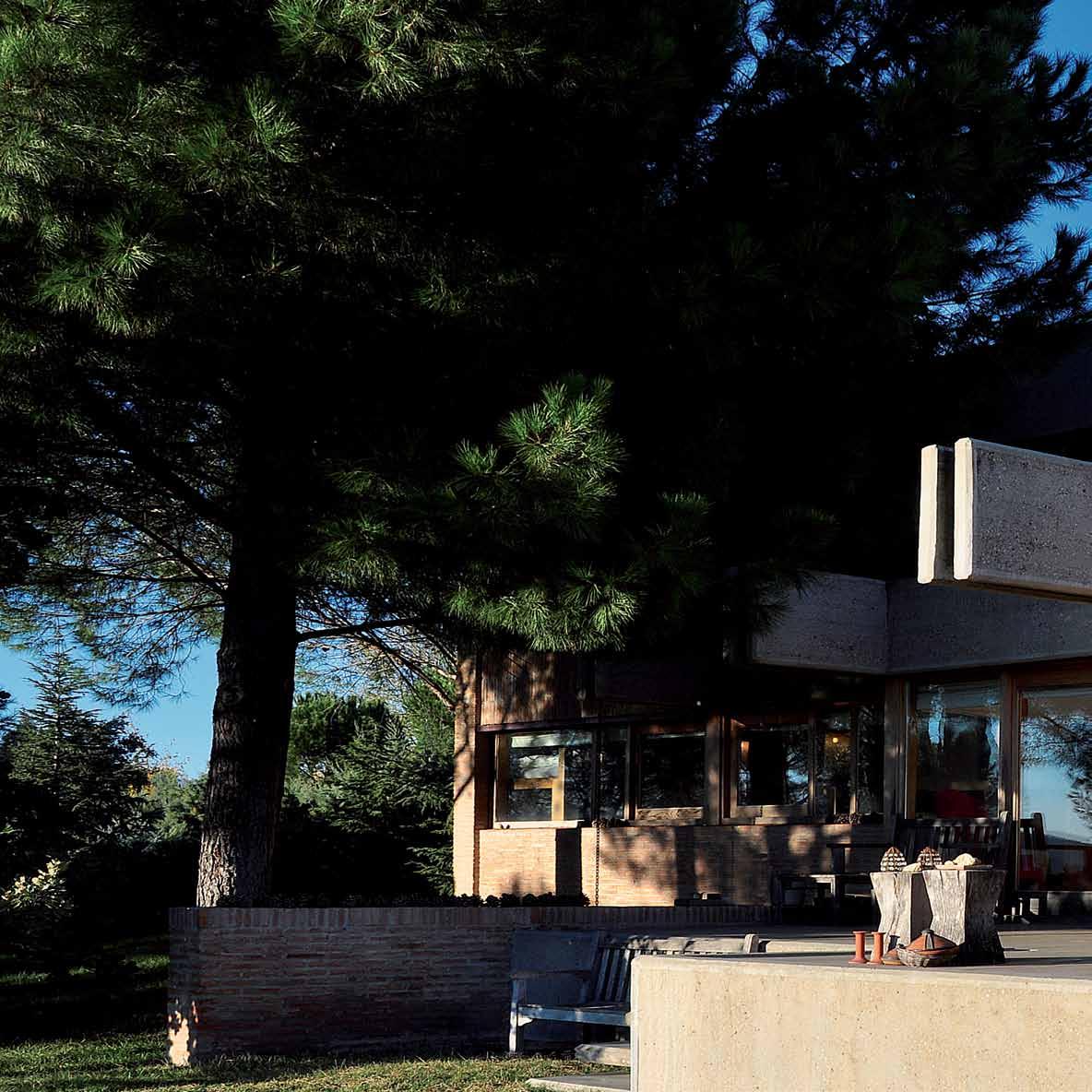

CASA BUESO. I - G. AGEA

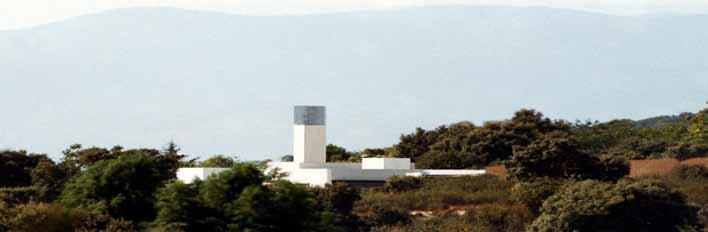

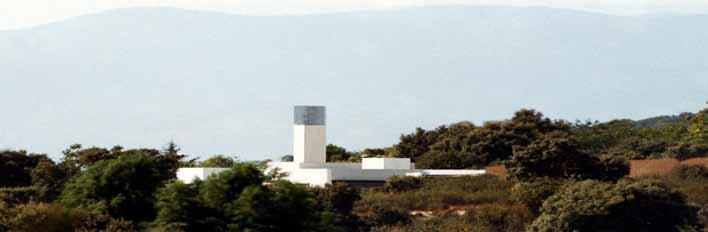

Vistas, soleamiento, acceso y topografía se conjugaron favorablemente en el terreno. Todo ello, unido a un programa sencillo y coherente, tuvo como resultado una casa bien vivida y muy disfrutada por sus propietarios, que han sabido ir adaptándola a una situación familiar cambiante durante más de dos décadas.

La estructura ordenada de muros de carga dispuestos paralelamente, hechos con ladrillo de tejar, soporta bandejas horizontales a distintos niveles que relacionan unos espacios con otros, articulados en torno a un patio, a la vez que potencian las magníficas vistas sobre la sierra de Gredos.

La propia vivienda protegida del rigor del norte, hace de pantalla confiriendo privacidad al jardín, sin necesidad de cerrarse al espacio público.

Hormigón abujardado en los elementos estructurales del cerramiento, madera, y hormigones pulidos en los suelos, acompañan al ladrillo con sobriedad y con un noble envejecimiento que han hecho que la casa conserve el espíritu con el que fue construida.

BUESO. I - G. AGEA HOUSE

Views, sun exposure, access and terrain all happily came together on the site, together with a simple and coherent plan yielding a home which its owners have truly made use of and enjoyed, gradually adapting it to their changing family situations over the last two decades.

The structure of parallel, load-bearing brick walls sustains horizontal levels resting on different tiers connecting different spaces centered around a patio, while at the same time taking advantage of the magnificent views of the Gredos mountain range.

The home itself, serving as a buffer against the harsh northern wind, acts as a shield providing the garden with privacy.

Bushhammered concrete in the structural elements and wood and polished concrete on the floors, complement the brick with a sober air and noble aging which have allowed the house to conserve the spirit in which it was built.

32

34

PLANTA BAJA · GROUND FLOOR

35

ALZADO SUR · SOUTH ELEVATION

ALZADO NORTE · NORTH ELEVATION

ALZADO OESTE · WEST ELEVATION

36

SECCIÓN TRANSVERSAL · CROSS SECTION

37

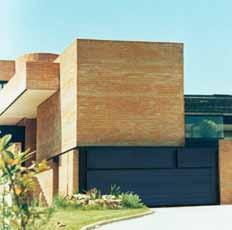

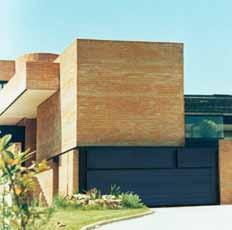

VIVIENDAS BARÓN DE LA TORRE

Este encargo tiene su origen en una modificación de la normativa urbanística, que pasó a autorizar viviendas adosadas en parcelas pequeñas en un entorno de viviendas unifamiliares. Esto originó la construcción de pequeños grupos de cuatro casas en hilera en parcelas de mil metros cuadrados, previamente ocupadas por una sola vivienda.

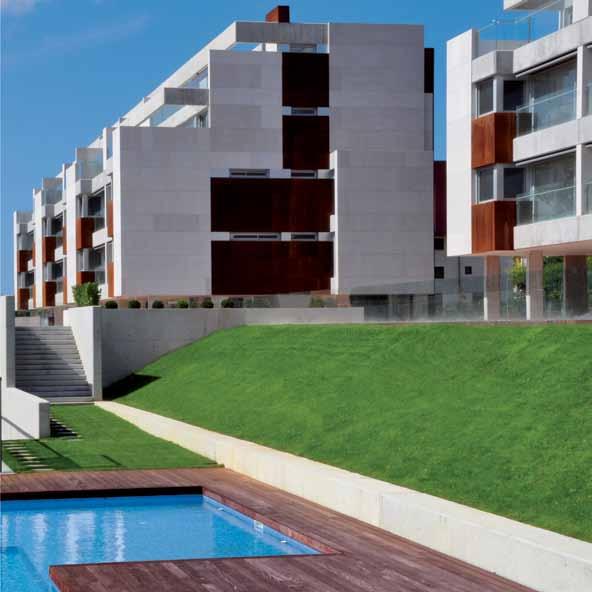

La solución adoptada trata de integrar plástica y funcionalmente las casas. La composición volumétrica extiende las posibilidades de ajardinamiento y los materiales utilizados realzan la vegetación, contrastándola con el color claro de la piedra caliza y buscando la reflexión del vidrio. Cada casa, a pesar del poco espacio disponible, tiene piscina y jardín privados y el programa de una vivienda unifamiliar asimilable a las del entorno, exprimiendo las posibilidades edificatorias.

El concepto resultó exitoso y fue imitado en promociones análogas posteriores. En el conjunto de la urbanización estos grupos de casas en hilera quedaron como anécdotas, pues el sentido común se impuso, y la normativa revirtió a su tipología original.

BARÓN DE LA TORRE TOWN HOUSES

This job stemmed from a modification of urban building laws which began to authorize townhouse-style constructions on small lots in a single family dwelling environment. This gave rise to the construction of small groups of four homes in a row on lots of 1000 square meters previously occupied by just one home.

The solution adopted sought to integrate the homes both plastically and functionally. The volumetric composition extended the landscaping possibilities, and the materials used enhanced the greenery, which contrasted well with the brightness of the sandstone, while the glass provided reflections. Each home, despite the limited space available, boasts a private pool and garden area, and the features of a single family home integrated with those around it, thus making the very most of the building possibilities present.

The concept turned out to be a success, and was imitated in similar, subsequent developments. In the urban area these groups of row house-style homes ended up as mere anecdotal anomalies, as common sense prevailed and the building code reverted to its previous requirements.

40

MADRID · 1988 - 1990

44

PLANTA PRIMERA · FIRST FLOOR

PLANTA BAJA · GROUND FLOOR

ALZADO NORTE · NORTH ELEVATION

ALZADO SUR · SOUTH ELEVATION

46

SECCIÓN A-AI · SECTION A-AI

SECCIÓN B-BI · SECTION B-B

47

48

49

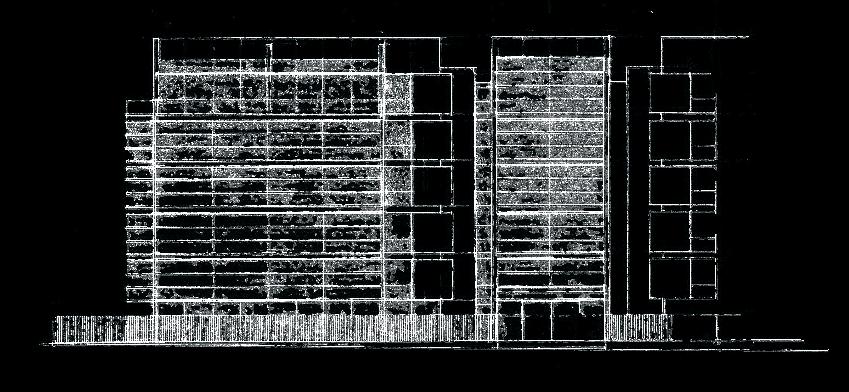

EDIFICIO MENÉNDEZ PIDAL 43

El proyecto comprende dos edificios longitudinales y prismáticos en una parcela con un frente muy estrecho. El acceso se produce en ambos por un testero creándose un espacio de acceso y recepción que comprende los dos primeros niveles, hasta el núcleo de comunicaciones situado en el centro de la planta.

El cerramiento es un muro cortina reflectante con ritmos horizontales que, en las fachadas de acceso, se apoya en paños de piedra que identifican visualmente el acceso.

El aparcamiento es abierto y porticado, resolviendo conjuntamente las circulaciones rodadas y peatonales soladas en piedra y flanqueadas perimetralmente por jardineras colgadas de los muros de contención.

Estos edificios fueron una de las primeras experiencias del estudio en el uso de muros cortina, de la que se extrajeron conclusiones que se trasladarían a otros proyectos. Se optó por un vidrio que reflejase la vegetación del entorno y no se templaron los vidrios, que no fueron necesarios, para no perder planimetría. De esta manera el proyecto visualmente se integra bien en un entorno de ciudad jardín con predominio residencial.

MENÉNDEZ PIDAL 43 BUILDING

The project consists of two longitudinal prismatic buildings on a narrow lot. Access to both is through a main facade, creating an access and reception area encompassing the first two levels before reaching the core at the facility’s center.

The enclosure is a reflective curtain wall with a horizontal pattern which, on the access facades, lies on stone supports visually identifying the entrance.

The parking area is open and porticoed, resolving both the vehicular and pedestrian traffic, crafted of stone and flanked on the perimeter by planters hanging from the retaining walls.

These buildings represented one of the studio’s first experiences with the use of curtain walls, which yielded lessons that would be applied to other projects. A glass reflecting the surrounding greenery was chosen, and to the greatest extent possible it was not tempered, in order not to lose the planimetric effect desired. In this way the project was visually well-integrated within a predominantly residential landscaped urban setting.

50

MADRID · 1989 - 1992

52

PLANTA BAJA · GROUND FLOOR

ALZADO ESTE · EAST ELEVATION

53

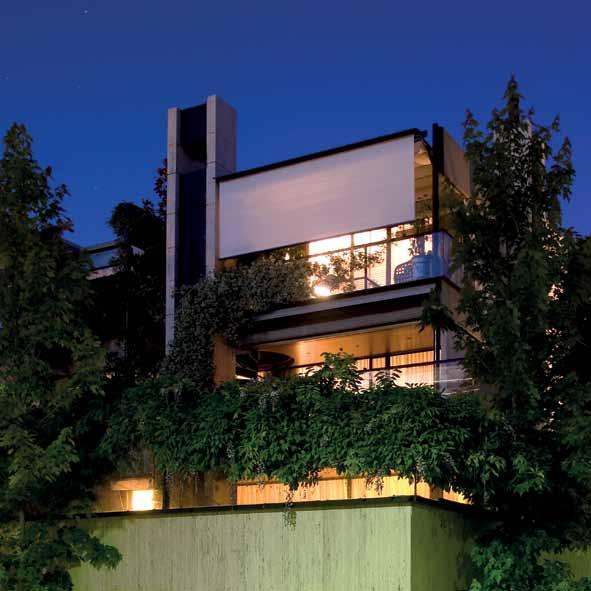

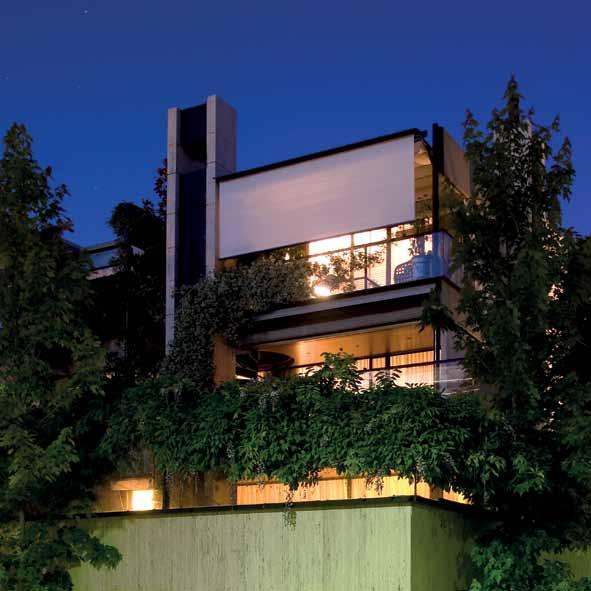

CASA VILLALÓN

Esta casa es el encargo de un buen amigo. Hacer la casa de un amigo y su familia tiene la ventaja y el inconveniente de que el encargo continúa vivo como tal indefinidamente, y es por tanto una buena lección para el estudio poder seguir a lo largo de los años el comportamiento de un edificio y su relación con el cliente.

La casa se sitúa en una ladera orientada al sur con una vista magnífica sobre la vega del Río Pas, cerca de Santander. Todas las estancias se orientan hacia el valle bajo un esquema longitudinal, en cuyo eje se produce el acceso por el norte a través de un gran zaguán, tras el que un patio interior acristalado relaciona y separa las circulaciones y las áreas de acceso y estancia. La escalera se contrapone al patio como un volumen cerrado entre pantallas de hormigón. El dormitorio principal y el estar que le sirve se abren hacia una doble altura sobre el salón, creando un espacio único de interrelación que se cierra al sur con una fachada acristalada poniendo en valor las vistas que motivan la situación de la casa.

Exteriormente se crea un volumen compacto con un buen factor de forma, donde el tratamiento de las texturas de vidrio, piedra y hormigón compone la geometría de la fachada.

VILLALÓN HOUSE

This house was a job for a good friend. Making a home for a friend and his family carries with it both the advantage and disadvantage that the project’s presence lingers indefinitely. As such, it has served as a good opportunity for the studio to follow over the years how a building holds up and the client’s relationship to it.

The house is located on a southward-facing slope with magnificent views over the Pas River near Santander. All of the rooms give towards the valley, observing a longitudinal scheme, its centerpiece featuring northern access via a hallway behind which an interior, glassed-in patio relates and separates the corridors, access areas and rooms. The stairway serves as a counterpoint to the patio as a closed space between concrete sheets. The master bedroom and the adjacent living room open towards a two-tiered design over the parlor, creating a unique interrelating space, closed to the south by a glassed facade which highlights and takes advantage of the views around which the home’s design is based.

Outside a compact space is created where the use of glass, stone and concrete textures contributes to the facade’s design.

54

SANTANDER 1989 - 1991

56

PLANTA BAJA · GROUND FLOOR

57

VIVIENDAS UNIFAMILIARES LÍGULA

Situado en el corazón del distrito de Chamartín en Madrid, el proyecto surge como continuación de experiencias anteriores siguiendo la línea racionalista en la que siempre había trabajado el estudio. Tiene especial interés la integración del conjunto en la trama urbana, resolviéndose la disposición de las parcelas dando frente a una T de uso privado. Solución ya utilizada por el estudio anteriormente, que ha demostrado con el tiempo ser una propuesta acertada.

La tipología de las viviendas en hilera está tratada conjuntamente, entendiendo el proyecto en su conjunto y no como la yuxtaposición de elementos repetidos. Para ello la composición es tan libre y orgánica como lo permite la tipología.

Las viviendas se vuelcan sobre jardines privados a mediodía, hacia los que se proyectaron grandes paños de vidrio en todos los niveles, incluido el semisótano, conectado con el jardín a través de un patio inglés.

La nobleza de los materiales con los que se trataron, tanto las viviendas como el vial de acceso a las mismas, han tenido como resultado un noble envejecimiento.

El diseño del conjunto permitió particularizar cada una de las viviendas, modificando el proyecto original en aspectos puntuales, enriqueciendo y dando espontaneidad al resultado final.

PREMIO AYUNTAMIENTO DE MADRID 1996

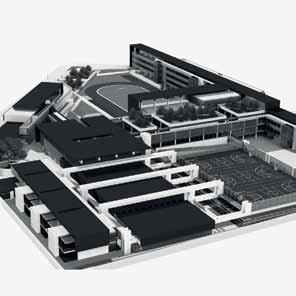

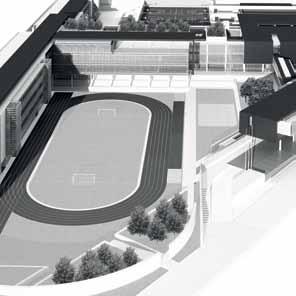

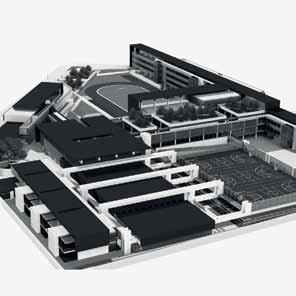

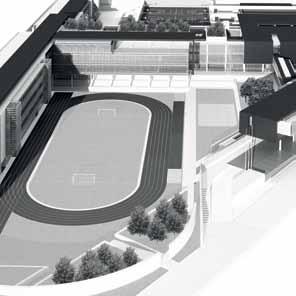

LÍGULA TOWN HOUSES

Located right in the heart of Madrid’s Chamartín district, the project came about as a continuation of previous experiences, following a rationalist line in which the studio had always worked. Worthy of special note is the integration of the buildings within their urban surroundings, and how the layout of the lots was dealt with by creating a “T” for private use, a solution previously employed by the studio, and which has proven to be a wise decision.

The typology of the houses, arranged in rows, was addressed globally, with the entire project conceived of within its setting, and not just as a mere juxtaposition of repeated elements. To this end the composition is as free and organic as the typology would allow.

The homes rest over private gardens and face southward, featuring great glass panels on all the levels, including the semi basement, connected to the garden through an areaway.

The quality of the materials used, in the houses as well as in the access to them, have allowed both to age well.

The design of the overall project made it possible to customize each one of the houses, modifying some points in the original plans, enriching and infusing the final result with spontaneity.

AYUNTAMIENTO DE MADRID AWARD 1996

MADRID 1993 - 1996

64

PLANTA BAJA · GROUND FLOOR

66

SECCIÓN 1 · SECTION 1

SECCIÓN 2 · SECTION 2

SECCIÓN 3 · SECTION 3

67

68 DETALLE DE CHIMENEA

DETAIL

· CHIMNEY

70

71

TORRELODONES 1986 - 1987

CASA REIN · SOLA

Siempre hemos pensado que es responsabilidad del arquitecto calibrar las posibilidades reales del cliente para materializar el encargo. Si el proyecto no se ajusta a éstas el resultado no se ajusta al proyecto. Esta casa fue concebida para construirse con pocos medios y se previó la ejecución de posteriores ampliaciones a medida que se ampliara la familia.

Tanto el sistema constructivo como los materiales elegidos tratan de optimizar la relación entre calidad, costo y mantenimiento. Funcionalmente se minimizaron las circulaciones, en los cerramientos se ajustó la proporción entre macizo y vano y se redujo el volumen construido mejorando el factor de forma.

Los aplacados de fachada son de piedra caliza con partición irregular buscando el contraste con las rocas de granito del entorno, y los planos de los huecos se completan con palastros de acero para acentuar la limpieza geométrica de de los paños de piedra.

REIN · SOLA HOUSE

We have always thought that it was the architect’s responsibility to gauge the viability of executing clients’ wishes and to decide whether plans are actually feasible or need to be revised. This house needed to be built with limited resources, and plans were drawn up accommodating subsequent expansion to respond to the family’s growth.

Both in the construction system as well as the materials employed, it was sought to optimize the relationship between quality, cost and maintenance. Functionally, the circulations were minimized, and in the enclosures, a balance was struck between solid materials and spans, while the volume constructed was adjusted by improving the shape factor.

The veneer on the facades is of limestone, with an irregular partition seeking a contrast with the granite rocks, while the apertures are rounded out with painted steel trim in order to accentuate the stark and clean geometric lines traced by the stone.

72

ALZADO SUR · SOUTH ELEVATION

ALZADO OESTE · WEST ELEVATION

74 PLANTA BAJA · GROUND FLOOR

75

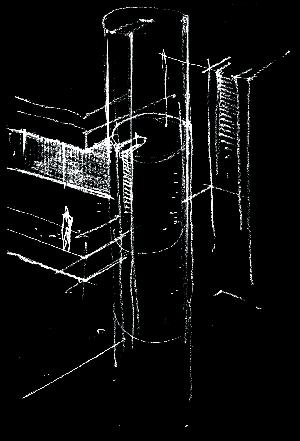

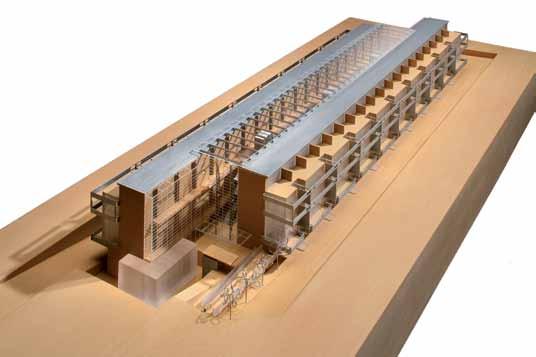

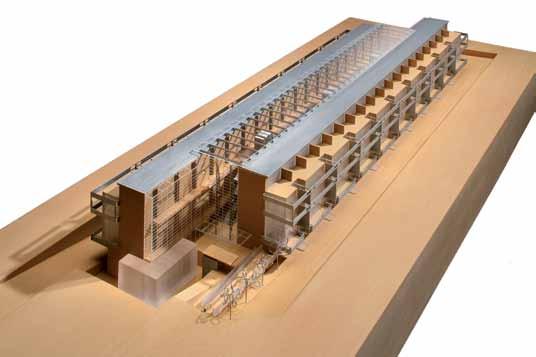

EDIFICIOS ESADE

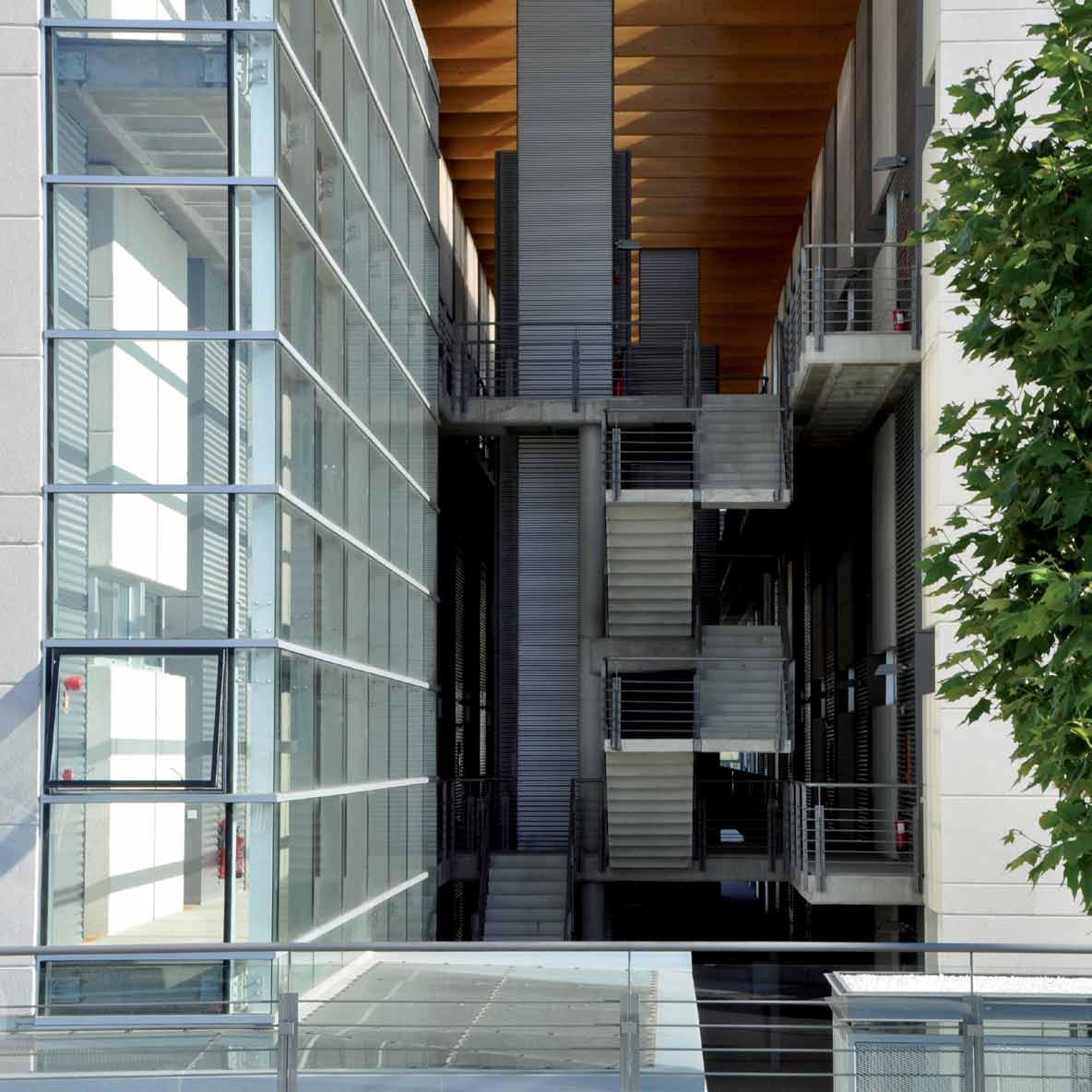

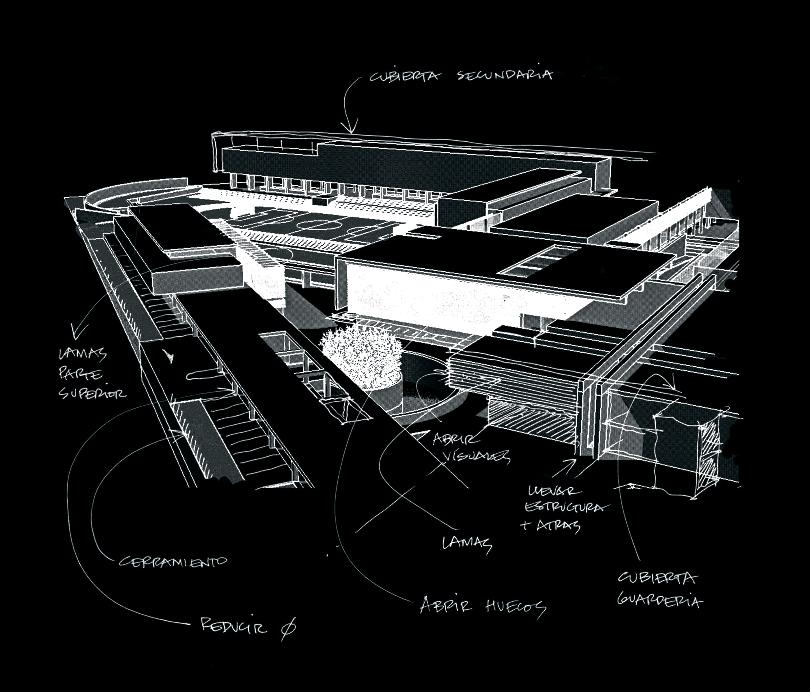

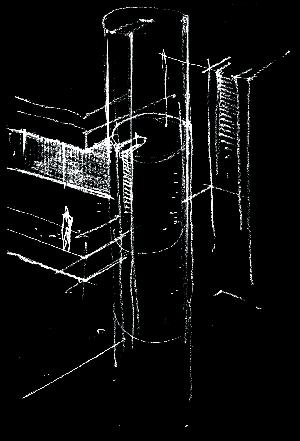

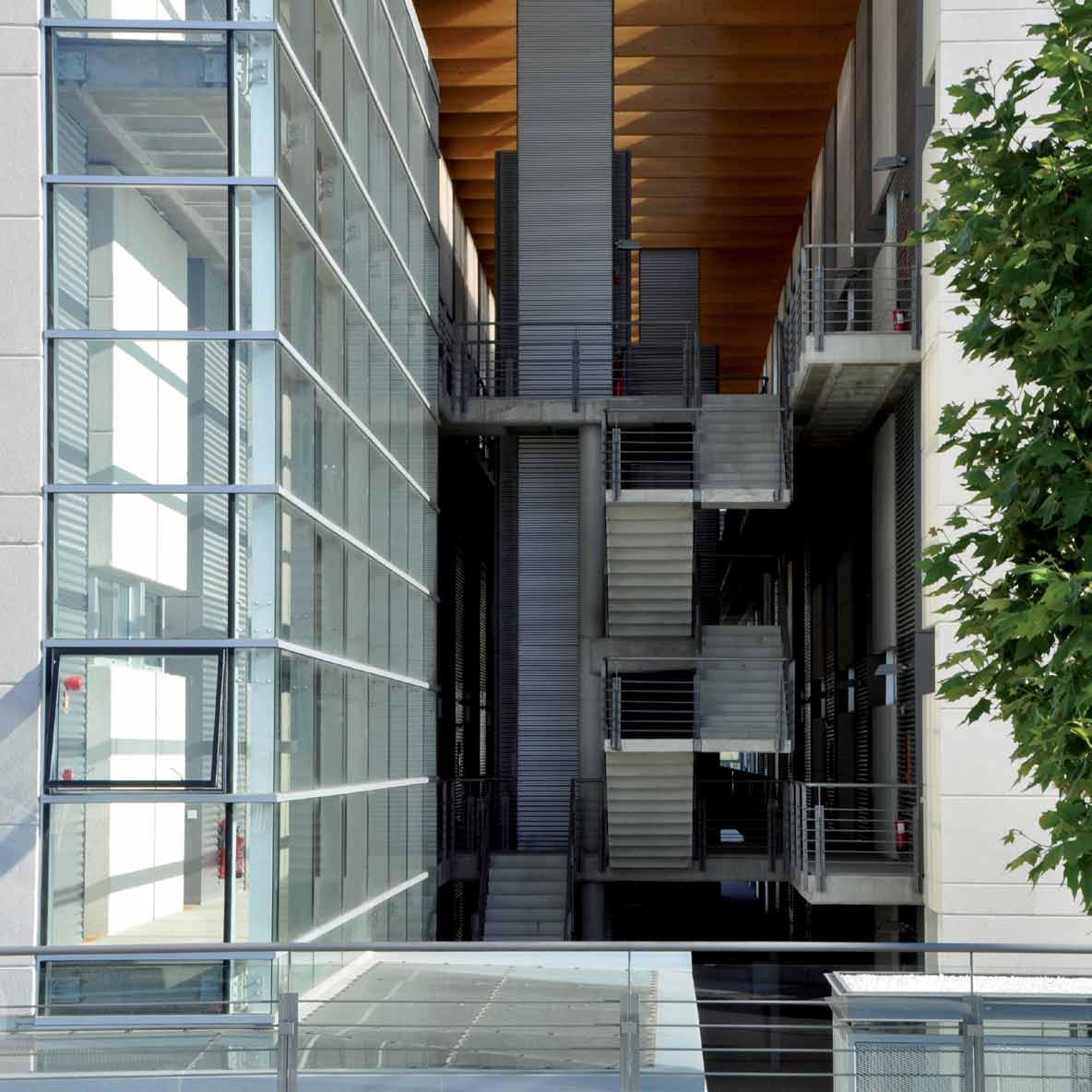

El proyecto se gestó sin saber cuál iba a ser su uso definitivo. Se trataba por tanto de conseguir espacios polivalentes que pudiesen adaptarse con facilidad a distintas exigencias funcionales. Para ello se proyectó cerrar el máximo volumen que permitiesen los parámetros urbanísticos, con espacios interiores vacíos en toda su altura interconectando las plantas.

Todo el cerramiento perimetral, excepto en los núcleos de comunicación vertical, es un muro cortina compuesto por módulos de vidrio apoyados en ménsulas de acero, que vuelan sobre el plano de piedra que cierra los pasos de forjado. No existen montantes verticales, con lo que se consigue un plano interior continuo de vidrio que permite cualquier modulación interior e incrementa el espacio disponible.

Cada edificio tiene un hito sobre el que se articula visualmente el prisma que lo conforma. En el edificio este el ascensor discurre por el interior de un cilindro de hormigón que se construyó con un encofrado deslizante. En el edificio oeste, el espacio vacío que interconecta las plantas, es un cubo de vidrio montado sobre una estructura etérea de acero.

Los materiales utilizados, piedra, vidrio y acero inoxidable, conforman también los cerramientos de parcela, que se hacen permeables mediante unos grandes paneles deslizantes de vidrio montados sobre un bastidor de acero y carril de deslizamiento oculto.

ESADE BUILDINGS

The project was born even as the building’s final use was as yet undetermined. Thus, the aim was to create flexible, multi-use spaces which could be easily adapted to satisfy different functional demands. To this end the plans called for closing off the maximum volume which urban parameters would allow and creating empty interior spaces connecting the floors.

The entire perimeter enclosure, except at the centers of vertical connection, is a curtain wall made up of units of glass supported by steel brackets located over the sheet of stone closing the forged entryway. There are no vertical stanchions, yielding a continuous glass interior which allows for interior or exterior variations and increases the space available.

Each building features a highlight upon which the structure conforming it is visually expressed. In the eastern building the elevator runs through the interior of a concrete cylinder, which was built with a sliding formwork structure. In the western building the empty space connecting the floors is a glass cube resting upon a steel space frame.

The materials used – stone, glass and stainless steel – were also employed in the enclosure to the property, in which openings were introduced featuring sliding glass panels resting on steel frames in which the slots upon which they slide are concealed.

76 MADRID · 1996 - 2000

78

PLANTA BAJA · GROUND FLOOR

ALZADO SUR · SOUTH ELEVATION

ALZADO ESTE · EAST ELEVATION

80

81

82

83

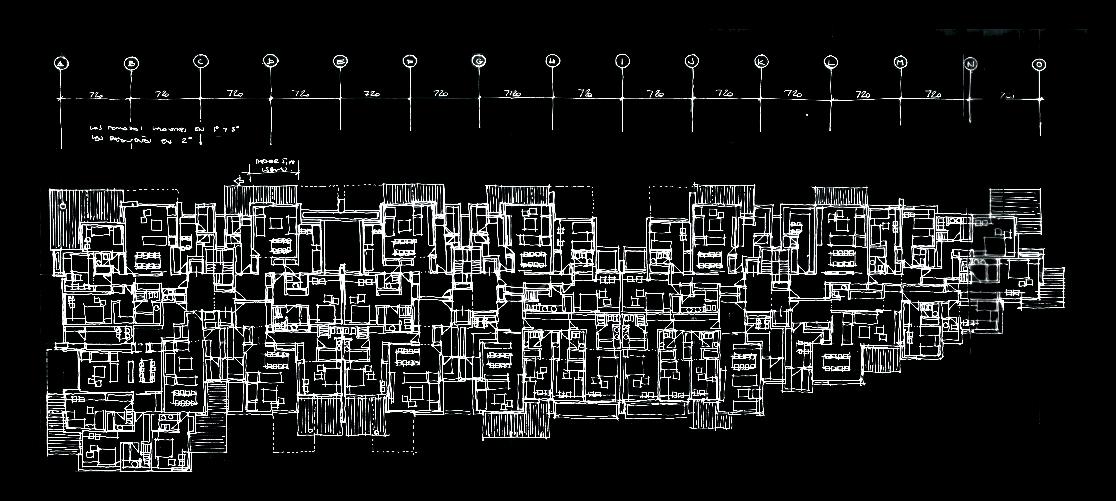

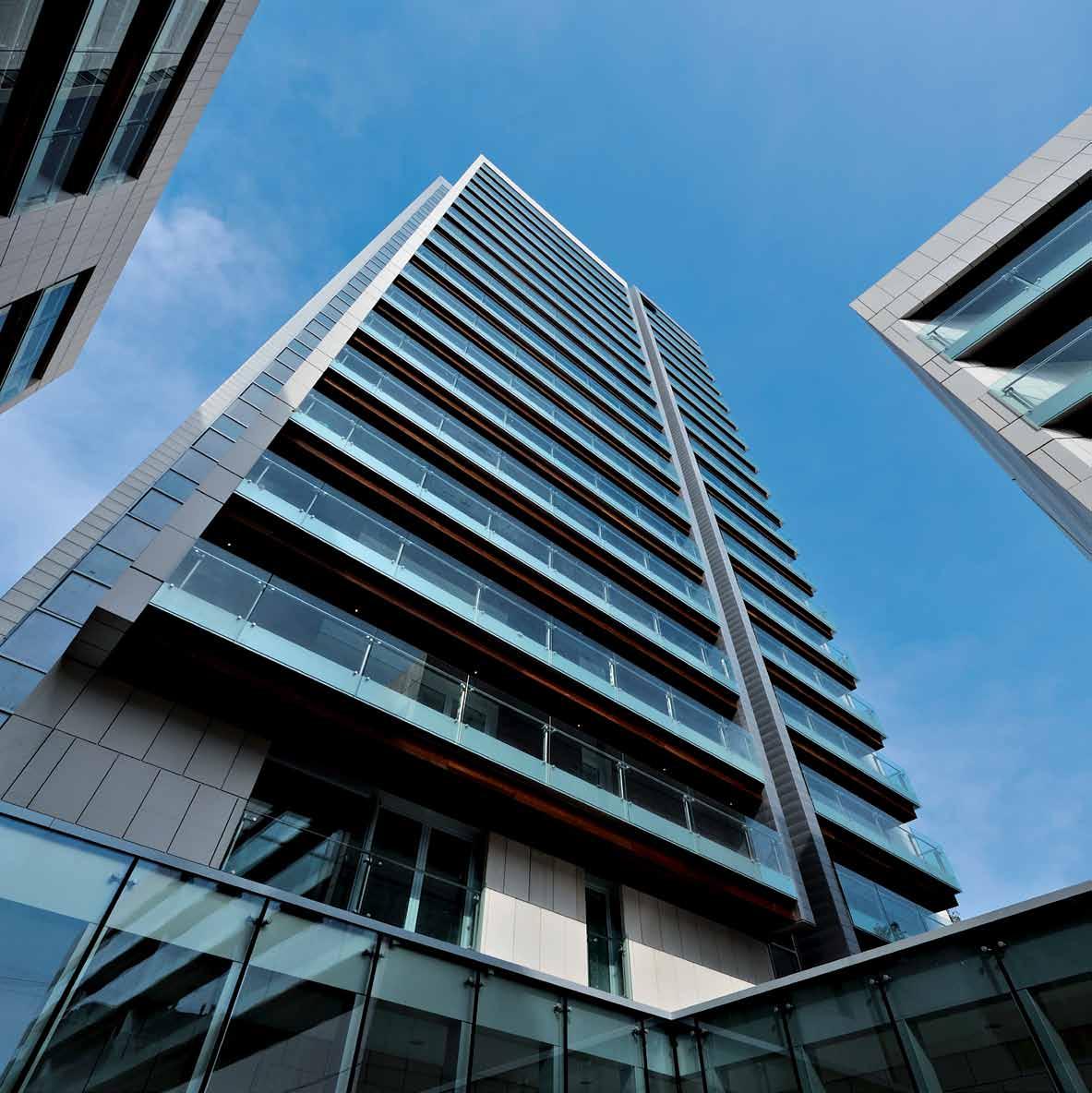

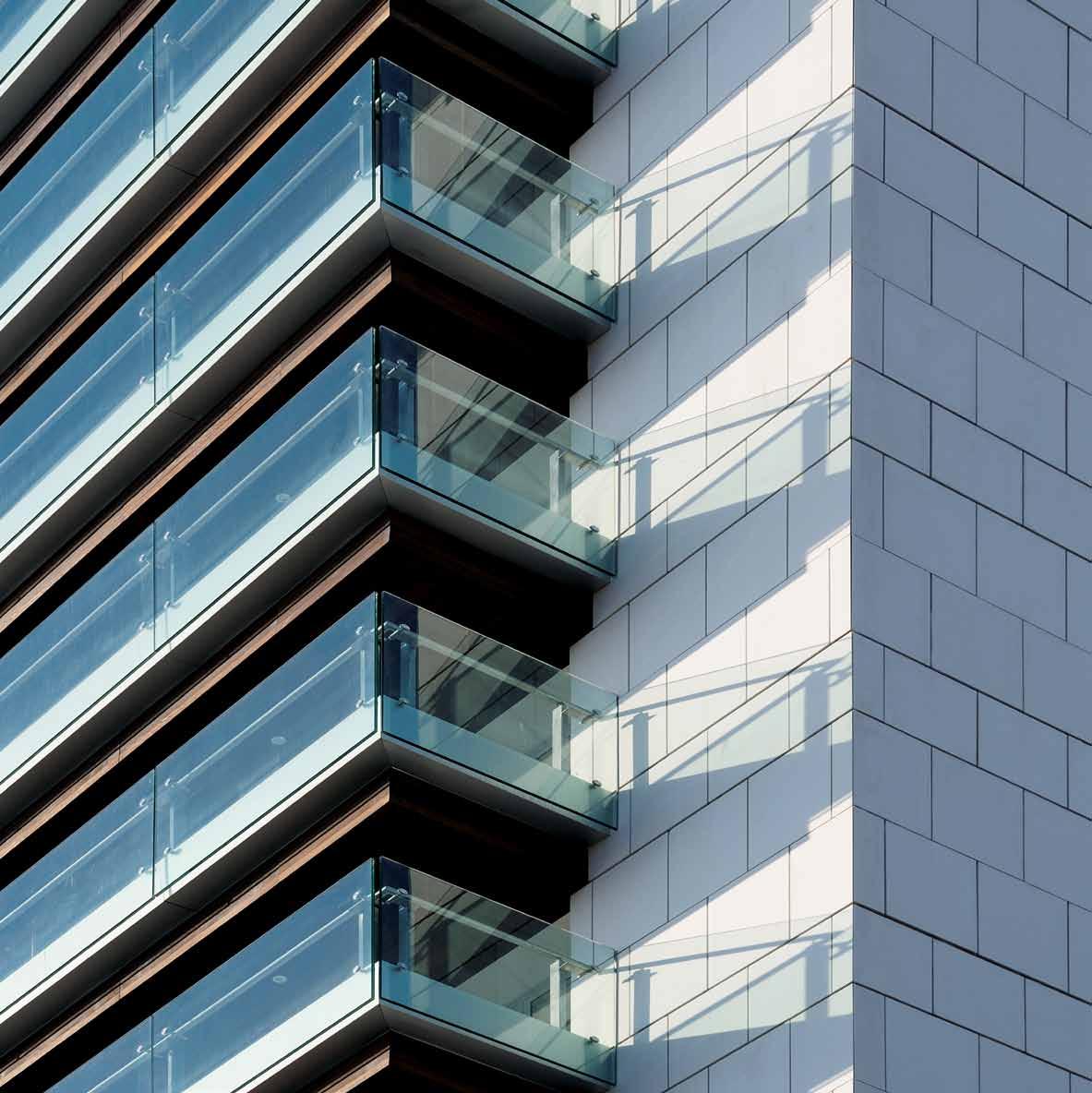

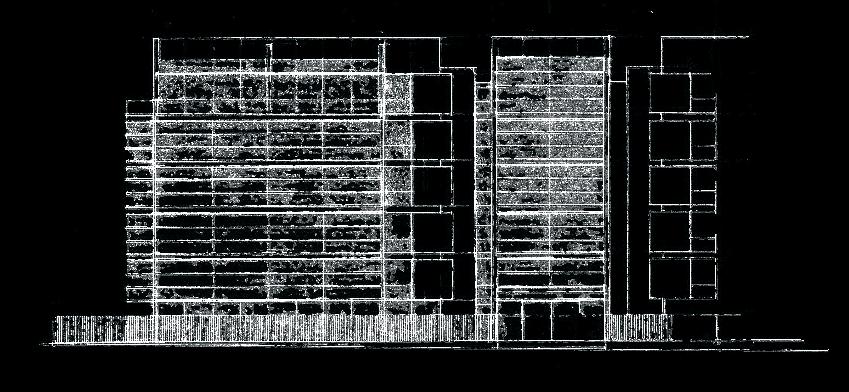

RESIDENCIAL PASEO LA HABANA

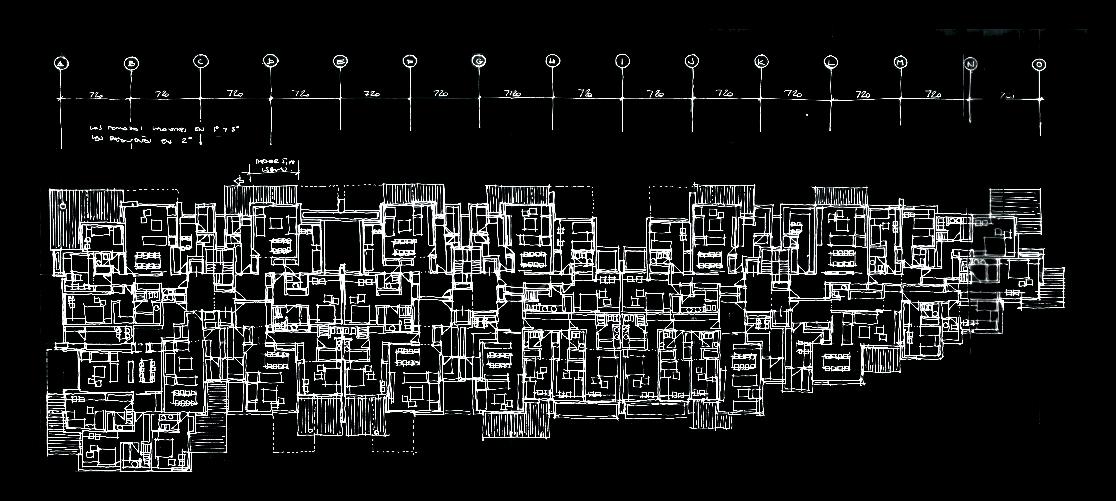

173-177

Se trata de un edificio residencial de viviendas con estudios en planta baja vinculados a las mismas, situado en un barrio residencial de Madrid en un entorno ajardinado, pero no ajeno a la agresión de las arterias urbanas de tráfico rodado intenso.

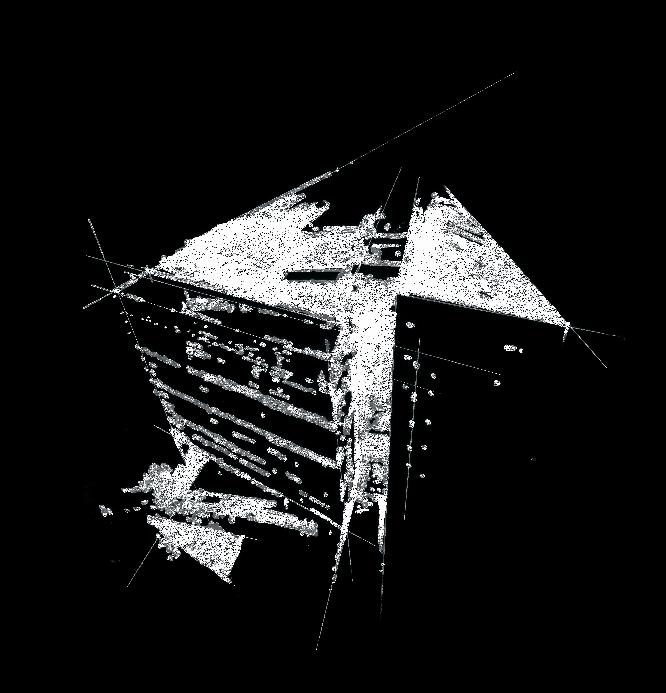

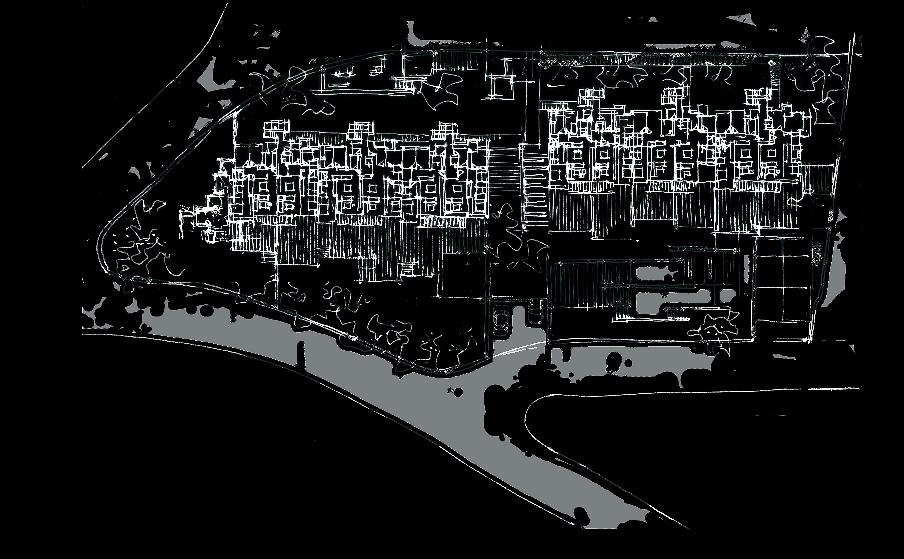

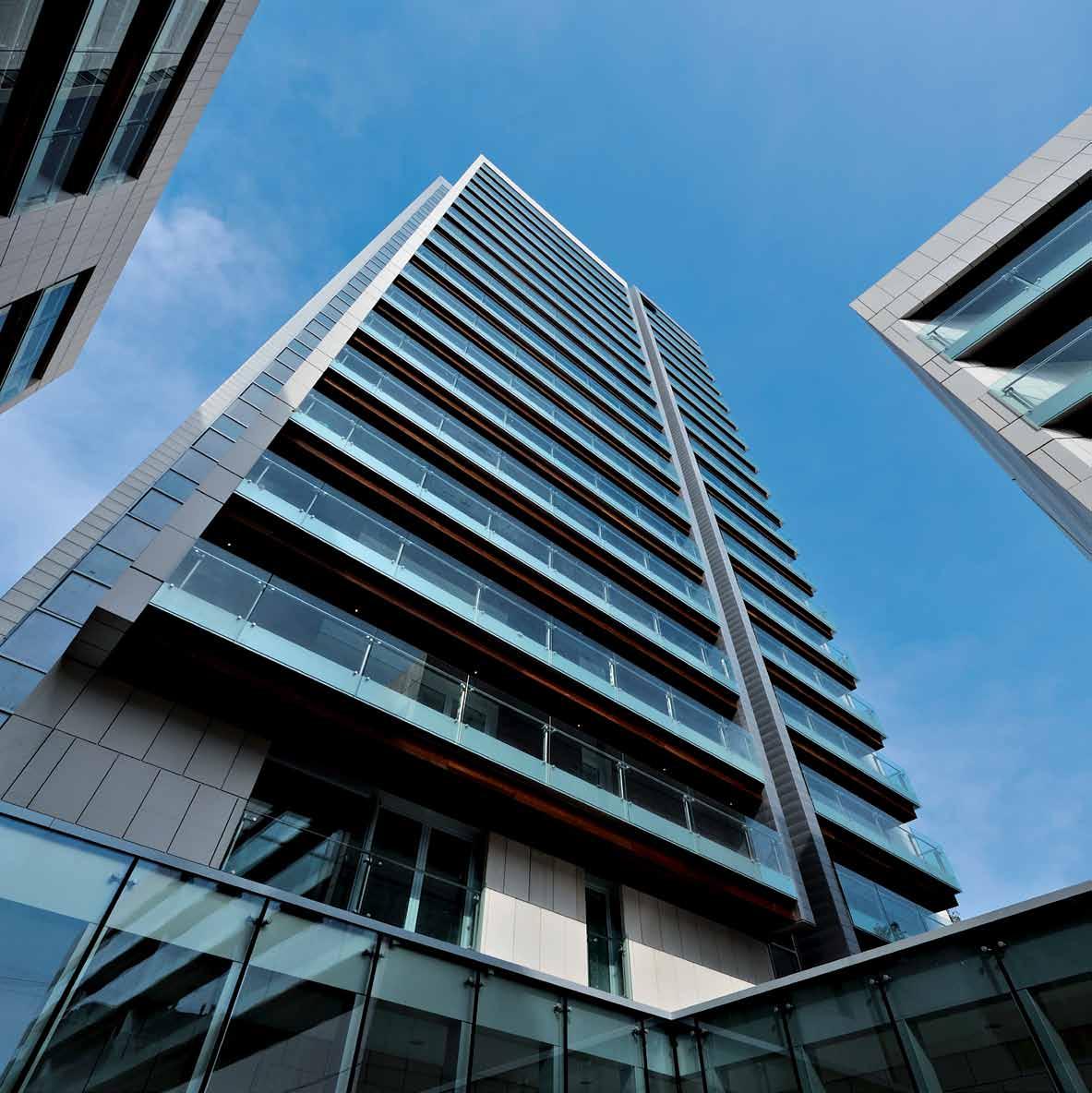

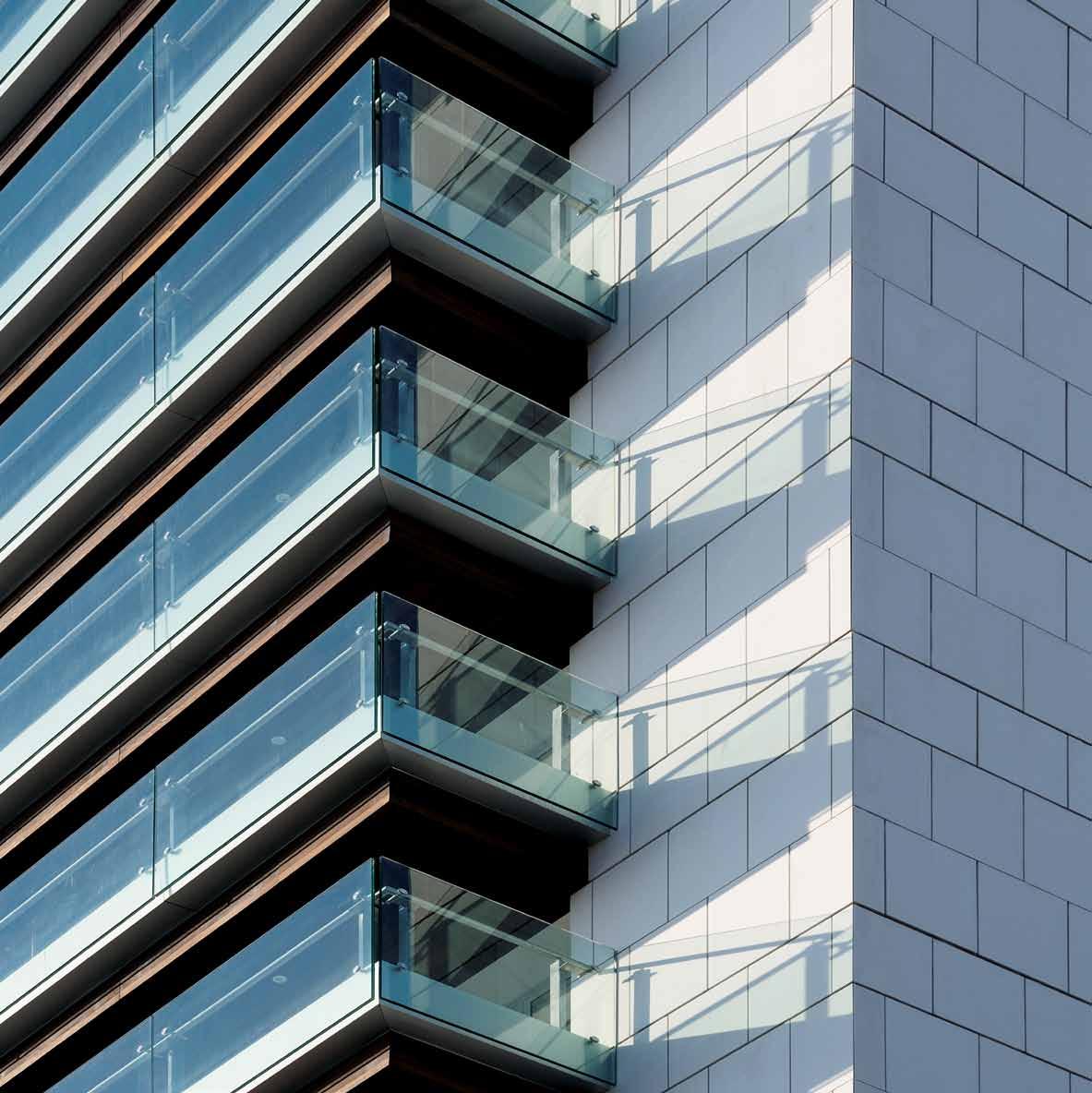

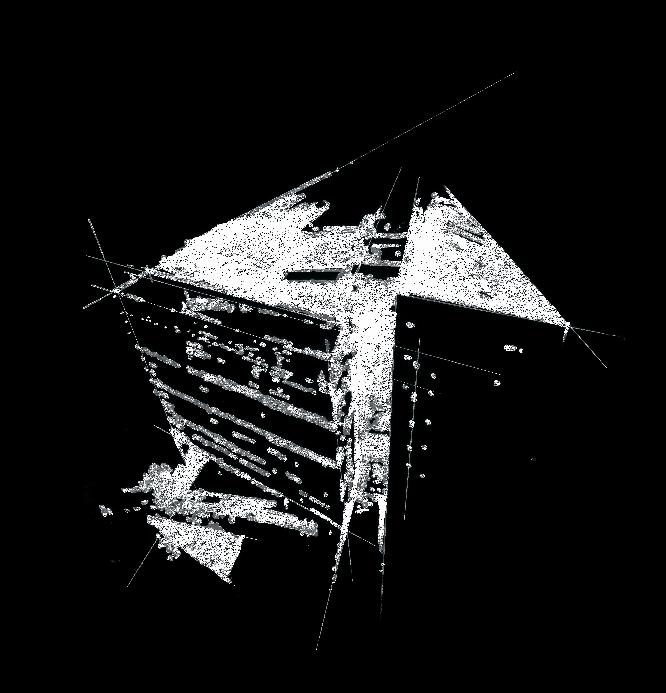

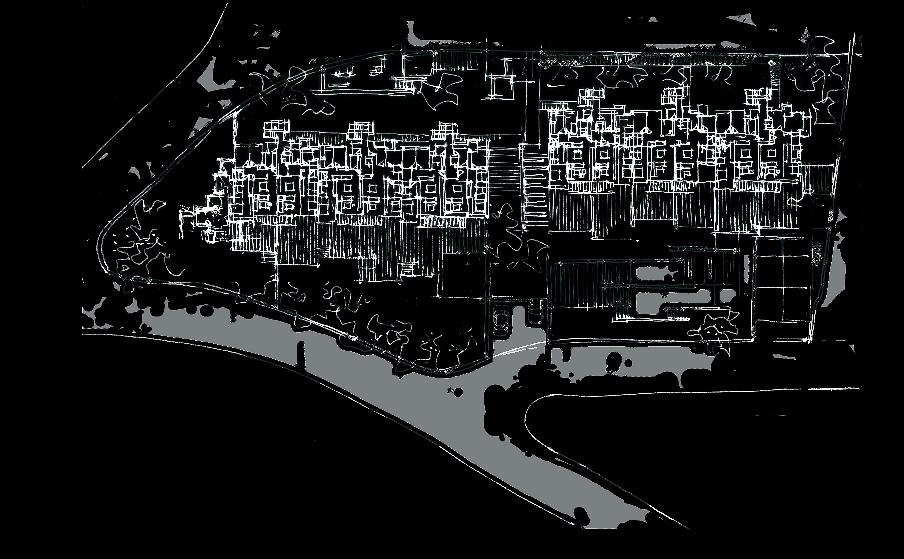

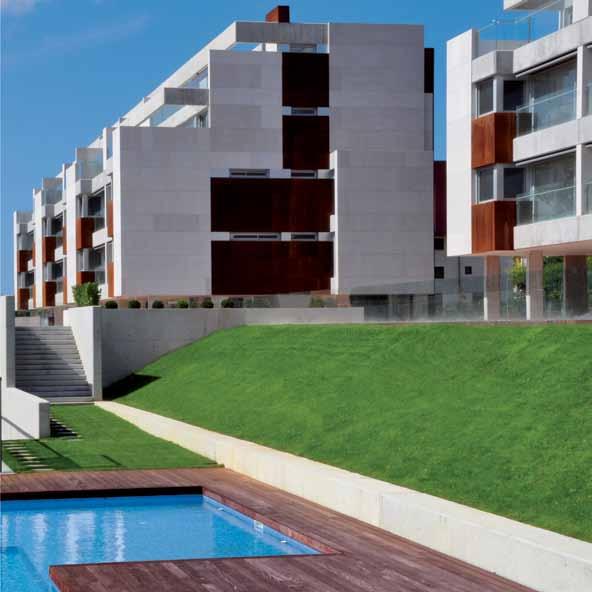

Se buscó deliberadamente escalonar el edificio creando plataformas verdes integradas en las viviendas, trasladando conceptos desarrollados en proyectos anteriores en el estudio a un edificio exento, con la intención de recrear el ambiente que confieren los espacios cóncavos, y proporcionando una protección visual que hiciera viable el uso privativo de las zonas exteriores en los distintos niveles.

Se proyectaron dos núcleos verticales de comunicación, que otorgan una gran independencia a las viviendas, y que resuelven satisfactoriamente los accesos y circulaciones interiores.

Por su visibilidad en el mercado residencial madrileño, fue un proyecto que originó una sucesión de encargos con vocación de réplica por parte de distintas propiedades.

Visto retrospectivamente, el mayor acierto ha sido el alto nivel de satisfacción de los usuarios, que no sólo han contribuido con enorme ilusión al mantenimiento del edificio, sino que se sienten identificados con un lenguaje arquitectónico que han adoptado como suyo.

PREMIO AYUNTAMIENTO

PASEO LA HABANA

RESIDENTIAL

173-177

This a residential building with studios on the lower floor linked to the homes, located in a residential, landscaped Madrid neighborhood not entirely shielded from the impact of the city’s busy traffic arteries.

It was deliberately sought to approach the project in stages, creating landscaped platforms integrated into the homes, bringing to bear concepts developed in previous projects by the studio for a free-standing building, with the intention of recreating the atmosphere generated by concave spaces while supplying visual protection which would make possible the private use of the exterior areas on the different levels involved.

Two cores were conceived, granting the homes a pronounced degree of independence while satisfactorily resolving the issues of interior access and movement.

Due to its high-profile nature in the Madrid residential market, it was a project which led to a series of jobs based on requests for replicas by different entities.

Looking back on it now, the project’s greatest success has been the high levels of satisfaction reported by residents, who not only enthusiastically contributed to the building’s maintenance, but also feel identified with an architectural style which they have adopted as their very own.

84

1998 - 2001

MADRID

DE MADRID 2001

PREMIO ASPRIMA 2004

-

AYUNTAMIENTO DE MADRID AWARD 2001 - ASPRIMA AWARD 2004

88 PLANTA BAJA · GROUND FLOOR

90

PLANTA ÁTICO · PENTHOUSE FLOOR

PLANTA CUARTA · FOURTH FLOOR

PLANTA TERCERA · THIRD FLOOR

ALZADO NORTE · NORTH ELEVATION

ALZADO SUR 1 · SOUTH ELEVATION 1

ALZADO SUR 2 · SOUTH ELEVATION 2

ALZADO ESTE · EAST ELEVATION

92

SECCIÓN · SECTION

94

ESCALERA DE CARACOL · SPIRAL STAIR

96

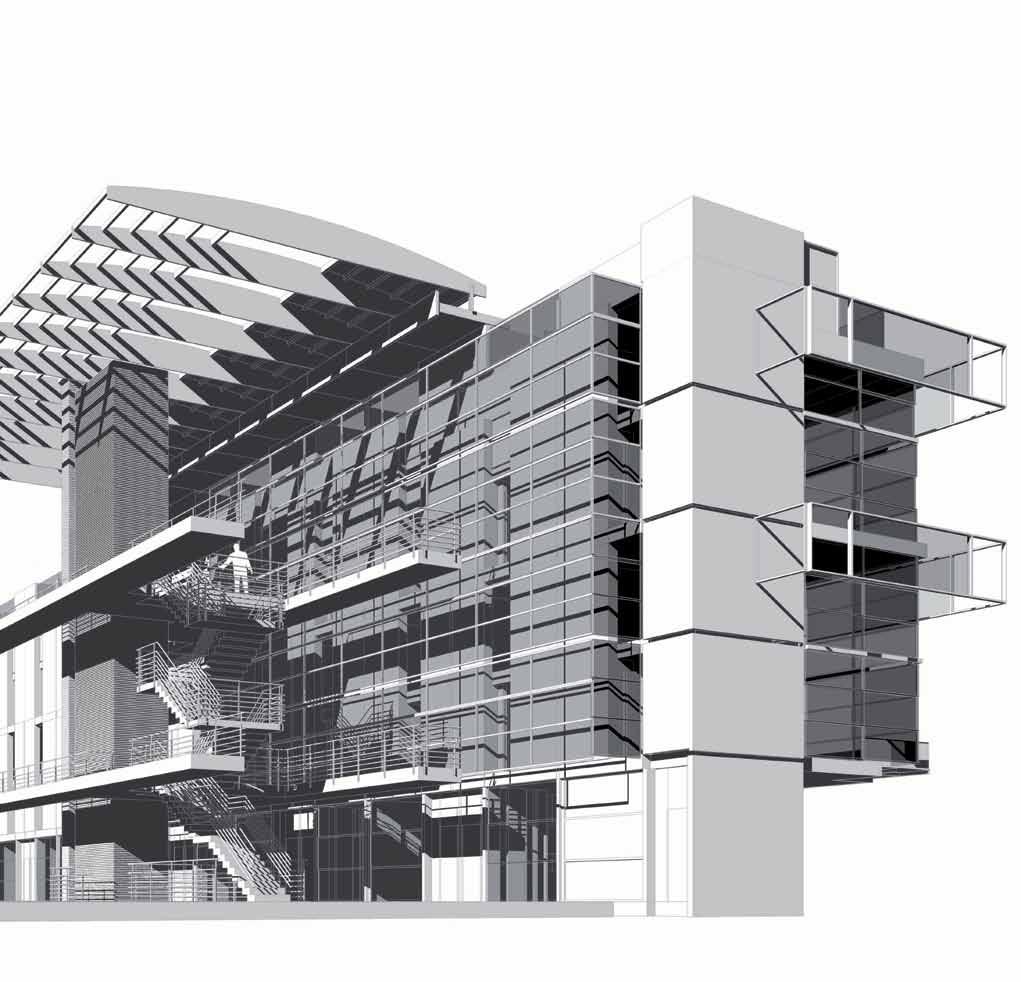

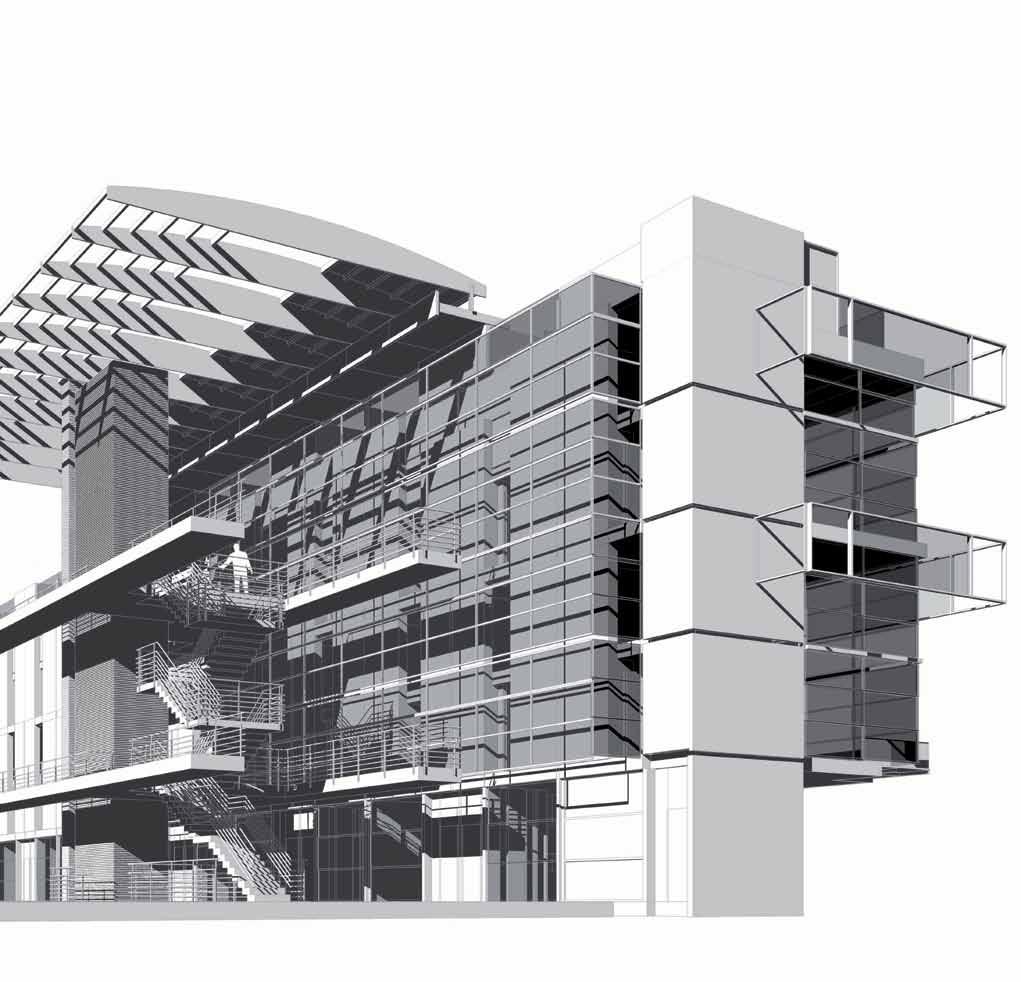

EDIFICIO BALUARTE

Este proyecto se comenzó en el estudio cuando todavía era socio Jorge BuesoInchausti. Tras su marcha desarrolló el proyecto y construyó el edificio. Hemos querido incluirlo como homenaje a los muchos años durante los que Jorge formó parte del estudio.

El proyecto es un ejercicio de síntesis de lo que formal y funcionalmente es un edificio de oficinas. Está formado por dos semiplantas completamente diáfanas, ya que la estructura vertical se dispuso en el exterior para no interferir ni en la planta ni en el cerramiento. Las semiplantas se conectan con un elemento central que aloja comunicaciones y servicios y que, exteriormente, es más másico para articular los volúmenes en torno a él e identificar el acceso.

Compositivamente se dio predominio a los ritmos horizontales del muro cortina buscando el contraste con los pilares de hormigón que, uniéndose por grandes vigas de canto sobre el volumen acristalado, soportan y enriquecen la geometría prismática del los volúmenes cerrados.

BALUARTE BUILDING

This project was undertaken by the studio when Jorge Bueso-Inchausti was still a partner. After his departure, he carried out the project and the completed building. We wanted to include it as a tribute to Jorge and the many years during which he formed part of the studio.

The project is an exercise in synthesis of what formally and functionally is an office building. Made up of two completely diaphanous half floors, as the vertical structure was arranged outside not to interfere either with the floor or the enclosure. The half floors are connected via a central element, housing communications and services which, outside,is of greater mass in order to articulate the volumes around it and to identify the entrance.

In terms of composition, horizontal patterns predominate on the curtain wall in search of a contrast with the concrete pillars which, connected by massive edge beams over the glassed area, support and enrich the multi-faceted geometry of the closed-in spaces.

98

MADRID 2002 - 2004

100

PLANTA BAJA · GROUND FLOOR

ALZADO NORTE · NORTH ELEVATION

101

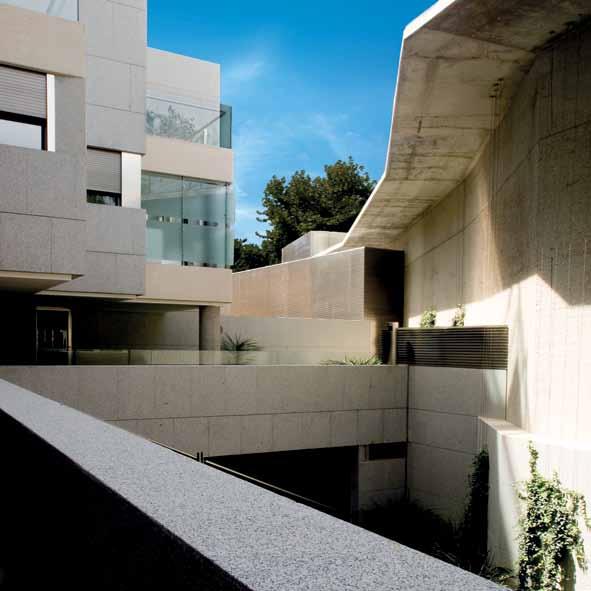

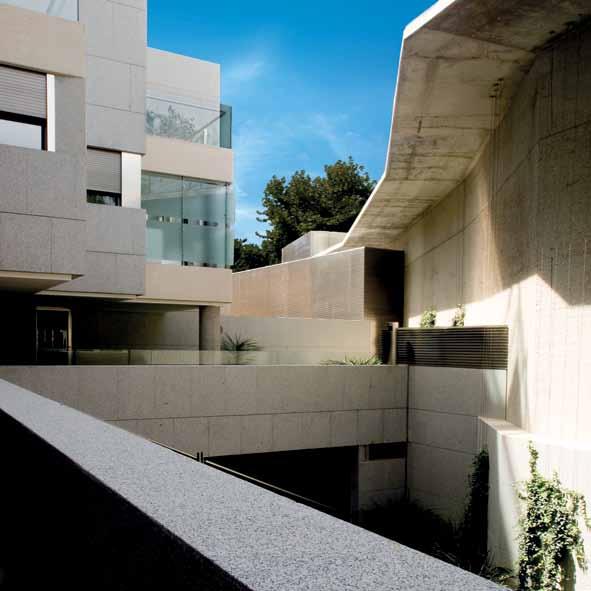

EDIFICIO FRANCISCO SUÁREZ

El encargo de este edificio pedía específicamente, a solicitud del cliente y por razones comerciales, utilizar el mismo lenguaje arquitectónico usado por el estudio en dos edificios cercanos, por lo que el desarrollo del proyecto se centró en la volumetría, ligada sobre todo al buen funcionamiento del complejo programa de viviendas que tenía que albergar.

El solar, alargado, tiene la particularidad de estar atravesado longitudinalmente por un túnel del ferrocarril que discurre a escasa profundidad. Por ello para cimentar el edificio hubo que disponer un sistema de vigas pretensadas de gran canto, apoyadas en pilotes en sus extremos a ambos lados del túnel sobre las que nacen los soportes.

En planta baja se disponen viviendas con jardines hacia el interior y un área porticada, recorrida longitudinalmente por una marquesina que articula la circulación entre portales. Las plantas primera, segunda y tercera contrapean sus terrazas dando movimiento a las fachadas. En planta ático se ajardinan los retranqueos, accediendo estas viviendas al sobreático donde disponen de piscina y jardín.

Consideramos este proyecto como el último de una línea de trabajo en edificación residencial en la que, tanto formal como conceptual y funcionalmente, el estudio ha trabajado entre 1997 y 2004, motivado por la coincidencia en el tiempo de varios encargos de características similares.

FRANCISCO SUÁREZ BUILDING

The specific instructions received by the client for this project, for commercial reasons, were to employ the same architectural style used by the study in two nearby buildings. Thus, the development of the project centered on volumes, linked above all to the sound functioning of the complex series of dwellings which it was to house.

The elongated plot was peculiar in that it was longitudinally crossed by a train tunnel running at a shallow depth. As a result, in order to reinforce the building, it was necessary to employ a system of deep prestressed beams, resting on piles at their ends on both sides of the tunnel, with the supports arising from the beams.

On the lower level are homes with landscaped areas towards the interior and a porticoed area, with an awning running lengthwise, framing the space lying between entrances. The terraces of the first, second and third floors are staggered, infusing the facades with a sense of movement. On the top floor setback zones lays gardens, with these homes featuring access to a penthouse area offering a pool and garden.

We consider this job to be the last in a line of residential building projects upon which formally, conceptually and functionally the studio worked between 1997 and 2004, as a result of the convergence of various jobs with similar characteristics.

102

MADRID 2004 - 2009

ALZADO SUR · SOUTH ELEVATION

ALZADO NORTE · NORTH ELEVATION

ALZADO ESTE · EAST ELEVATION

ALZADO OESTE · WEST ELEVATION

104

106 PLANTA ÁTICO · ATTIC LEVEL PLANTA PRIMERA · FIRST FLOOR

108

SECCIÓN TRANSVERAL · CROSS SECTION

109

RESIDENCIAL

CONDES DEL VAL

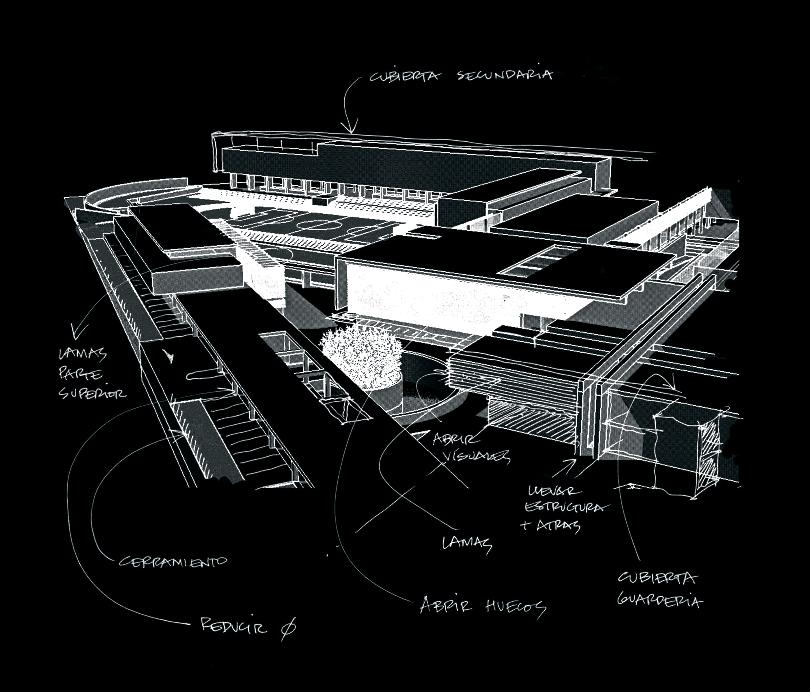

Este edificio planteaba un reto ciertamente difícil al tener que conjugar múltiples factores: