Editorial

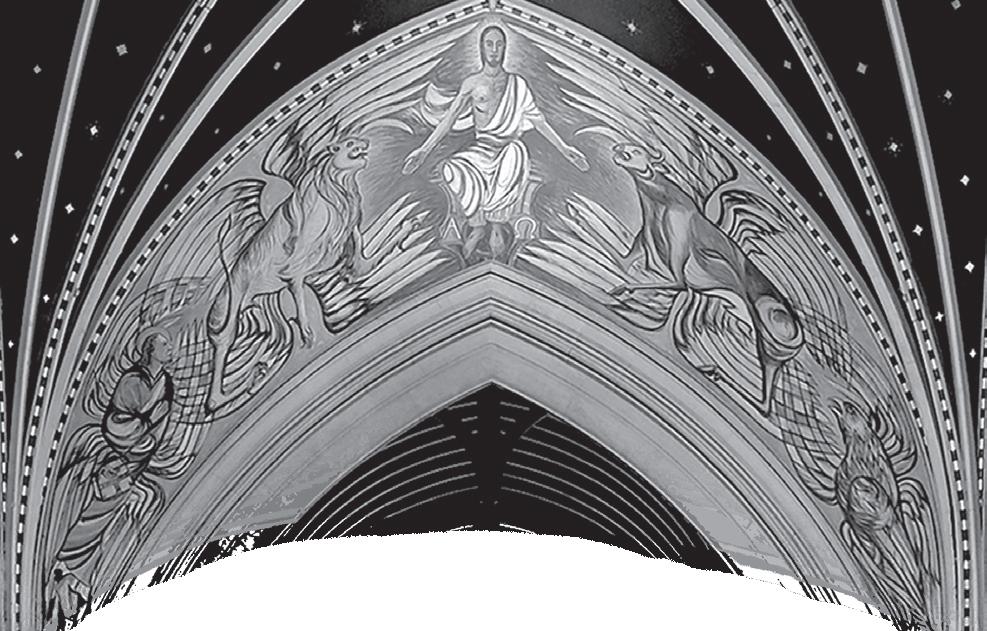

“After this I looked, and there was a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, from all tribes and peoples and languages, standing before the throne and before the Lamb, robed in white, with palm branches in their hands. They cried out in a loud voice, saying, ‘Salvation belongs to our God who is seated on the throne, and to the Lamb!’” Revelation 7.9-10

As WSCF we are privileged to be a part of a global community that is called to prophetic witness and nurtured by a radical hope for God’s reign in history. We share this vision with the Jesus movement of the New Testament who through their worship and service were aware of participating in the angelic chorus and in a diverse global community that witnessed to a just life and to the one who makes “all things new.”

Globalisation and the structures of a global market and politics were already immanent in the 1st Century AD with an empire that dominated and exploited the Mediterranean world. Yet the company that hymns the Lamb know themselves to be freed from the mechanisms and propaganda of empire to participate in a global community that witnesses to the givenness of creation and the equality of humanity, to the diversity and exchange of all peoples and the celebration of human maturity and creativity – to a just life. To practically engage and critique globalisation in a way that is hopeful and liberating is to share in this vision.

As Michael Taylor said at the thematic conference in Budapest in April 2008, “Christians, above all, wherever they work, play and live, should be interested in finding new solutions to old problems.”

The contributors to this edition of Mozaik have taken up this task in different ways. We are all invited to participate in this discussion and examine its implications. To continue this dialogue or contribute to Mozaik, email wscfmozaik@yahoo.co.uk.

It has been my privilege to facilitate this discussion as Mozaik editor-in-chief and I would like to thank the European Regional Committee for this appointment. I would also like to honour Angharad Parry Jones for her work as editor-in-chief between 20072008 and would like to begin as she did, by stressing that for Mozaik to flourish it needs your thoughts, ideas, contributions and feedback. You can do this by emailing wscfmozaik@yahoo.co.uk or by joining the Mozaik Facebook group (just search for “Mozaik” on www.facebook.com).

That we all may be one!

Andrew

Andrew Scott

Narcolepsy

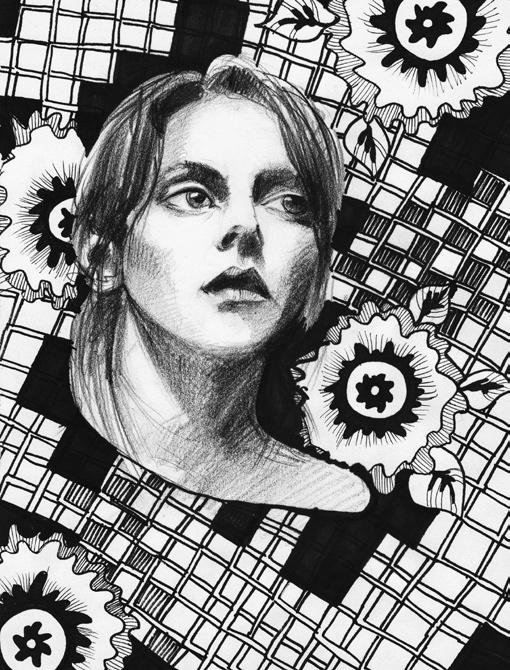

Rachael WEBER

a steady throbbing in the temple hinting some forgotten action or dream secured beyond boundaries of perception and I’m still standing still

what would have happened if he had not awaken to the cry of his disciples to the pleas of desperation to still wrestling wind to calm wrecking waters

it’s tiring – the impertinence of choice, there’s no proof, excuses playing hide and seek, words caught in the inhale –exhale of silent indecision

listlessly roaming parallel roads of REM, editing around reality, signing blurred agreements, neutralising language, to speak without opinion, the lack of meaning recycled into mindless rotations of slurred daily news

but my body’s in warm cocoon window shade blocking day or moon, the only horizon glares dusty white above and simply, I only want to push snooze...

hidden under bed or babel, who has ears to hear distant echoing cries amidst the lilting limericks cloaked in regular rhythmic rhymes

and the alarm bleats in numbing repetition screaming to drowsy mind but there isn’t time to think about what I don’t have time to do...

“I don’t care if you’re dead! Jesus is here and he wants to resurrect somebody!”

RumI, 13th Century Persian Sufi poet

4

Rachael WEBER, from Virginia, USA, works in the WSCF-E office in Budapest.

MOZAIK 22

I don’t care if you’re dead! Jesus is here and he wants to resurrect somebody!

szalamiki

Approaching Globalisation

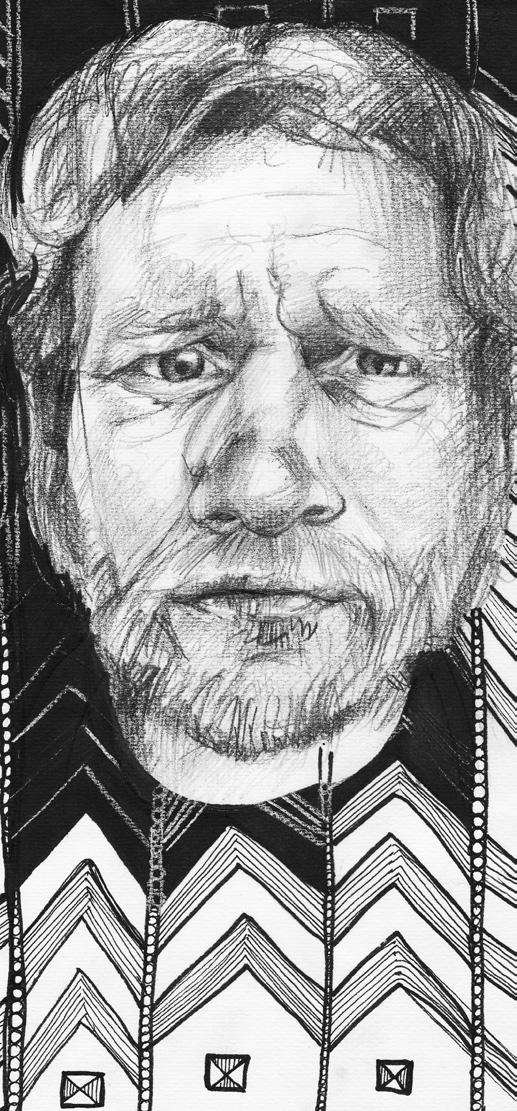

Markus SIDOROFF

Markus SIDOROFF, the Solidarity Coordinator of WSCF Europe, reflects on a lecture given by Michael TAYLOR at the 2008 Solidarity conference in Budapest

Though we have all heard of globalisation and experience it at some level, it is not easy to define - nor is it easy to evaluate our response.

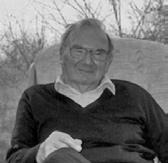

Michael TAYLOR, an emeritus professor of social theology at the University of Birmingham, has made an academic investigation of globalisation. As an ordained minister and former director of Christian Aid, he keenly appreciates the religious convictions and development issues that affect an understanding of globalisation. Having worked for the World Bank on development issues, he is also familiar with the institutions and systems of the international market. With this insight, he insists that, “globalisation is not a new phenomenon but has become intensified in recent times.”

Though the topic of globalisation is complex, at the WSCF Europe solidarity conference, ‘A Just Life or just life?’ in Budapest in April 2008, Michael TAYLOR introduced participants to methods of approaching and understanding globalisation.

Approaching Globalisation

“Firstly, globalisation has to do with the increasing movement and interconnectedness of people (as they travel), goods, services, ideas and the mobility of capital across national borders, all greatly helped by advanced information technology and the media.”

Few would see this mobility as negative in itself. Globalisation has made international exchange and co-operation possible in a way that it never was before. International NGOs such as WSCF experience the benefit of this: simply, the internet has made it easier to communicate with people throughout the world.

Globalisation also allows greater cultural exchange and the ability of people to move about. Members of western welfare societies are able to see and enjoy the fruits of this globalisation on the High Street. Not only is the laptop I am writing this article on made in China but we can buy crafts from Africa and India. Later, I might choose between eating Mexican or Thai food. I might also contemplate taking a Yoga class or an AfroCaribbean dance lesson. As mobility has increased, western societies have become more multicultural than ever and western culture has been enriched by influences from other continents.

Yet, we must consider whether the ‘west’ is benefiting more than other parts of the world from these ‘exotic spices’ that enrich our lives. In return we do not just export western products or aspects of popular culture but a dominant culture governed by the mechanisms of the global market which originate with and centre on western interests. This dominant culture is hard to resist and overwhelms ways of living and structuring society in the developing world where peoples are in danger of losing their own cultural identities. This is what Michael TAYLOR calls the spread of western culture or ‘cultural imperialism.’ This is the second way of approaching an understanding of globalisation. Western culture comes to determine how the culture in the developing world evolves and is exported.

Markus SIDOROFF (born 1982) is the Solidarity Coordinator of WSCF Europe. Currently he is completing his masters degree in music education and works as a choir conductor and music teacher in Helsinki. In his free time Markus enjoys jogging, literature and the company of good friends.

Michael TaylOR was a member of SCM as a student. He has taught social ethics in the University of Manchester UK and was Principal of a theological college there for 15 years, he was Director of Chirstian aid in london UK for 12 years, president of the Jubilee 2000 Debt Campaign, member of two commissions of the WCC, and he is a patron of SCM UK and now Emeritus Professor of Social Theology in the University of Birmingham. Michael TaylOR has written books on theology, worship, ethics and development.

5

5

Even Buddhism has in places been imported as a consumer good and lifestyle choice. There is an irony here; many in Europe now look to Asian and African cultures and religions to give deeper meaning to their lives, which have already been cut off from our own cultural roots and Christian heritage. We have become so infected by the staleness of the market and Hollywood films, junk

food and mass-produced popular culture, that we look abroad for new answers, while continuing to export this pop culture.

Where there is resistance to this process and reaction against alienation, “globalisation”, as Michael TAYLOR said, “may affect most parts of the world but is not necessarily a unifying force, provoking the reassertion of identities and cultures, the so-called ‘clash of civilisations’ and a widening gap between rich and poor between and within countries.”

We have already referred to the third feature that “has to do with the rise of a global economy which, since the collapse of socialism, is characterised as (free) market capitalism.” The rise of the global economy is indeed the most common association of globalisation and for many of us ‘market capitalism’ has connotations of greed and selfishness, especially in the current financial climate. Michael TAYLOR, however, spoke first of its benefits:

“Market capitalism has led to a spectacular improvement in living standards in some parts of the world (notably Western Europe) though often at the expense of others. It is now benefiting millions most obviously in India and China. By opening up to the market instead of relying on aid and charity, poor countries can trade their way out of poverty however painful it may be at first. The ‘market’ is an effective mechanism for matching supply and demand and a democratic one as well.”

It is interesting to note that according to western thinking even democracy (of which we are rightly proud) is something we can export. Democracies in their modern form grew out of Christian soil on the one hand and from the

6

A Just Life or just life? – Markus SIDOROFF: Approaching Globalisation

Globalisation may affect most parts of the world but is not necessarily a unifying force, provoking the reassertion of identities and cultures, the so-called ‘clash of civilisations’.

tradition of Western philosophy on the other. We have to question the appropriateness of democracy (at least as we currently understand it now) for Islamic societies.

Criticism of Market Capitalism

Michael TAYLOR reports that some Christians regard market capitalism as a “heresy, because it inevitably benefits the rich at the expense of the poor, which is fundamentally against Gospel values: so you can’t be a Christian and a capitalist (even though many have and western Christianity and the Protestant work ethic have been supportive of it). The Reformist position would say that capitalism is not wholly bad though there is a great deal wrong with it. There may not be any obvious alternative but there is a lot of room for reform.”

Elaborating on this, Michael TAYLOR led us through five significant problems with market capitalism that call for reform:

1) “Although poor countries are encouraged to trade their way out of poverty, the trading system is unfair. Lowering of trade barriers gives the advantage to strong trading nations and companies. The demand for low prices (for clothing for example) means low wages and sweat shops. Poor countries are forbidden to subsidise their industries or protect them as a condition of aid, whilst the US and the EU do both. Rich nations dictate economic policies to poor countries which should be free to decide for themselves. Big companies moving in can destroy the local economy and local markets. These and other problems have given rise to the Fair Trade movement.”

Not everybody in the global north benefits from this tendency either. In Finland, for example, big companies in the paper industry have downsized their factories and moved to countries where there is a cheaper labour force, thus increasing the problem of unemployment. This is interpreted as the sign of a dynamic company but many

of these companies make profit from the relocation, while firing workers, etc. They were simply seeking greater returns for their shareholders.

2) “The investment of surplus earnings is at the heart of capitalism but all too often it is short-term speculation to make money quickly rather than long-term investment involving sharing risks and creating stability. Too much money making has little to do with providing goods and services, and too much irresponsible lending and borrowing has produced the international debt crisis where poor countries have to choose between servicing their loans and providing schools and health care for their people. Those who organised the loans were not the ones who suffered when things went wrong, hence the Jubilee campaign to cancel the debts of the poorest countries.”

Again, irresponsible lending and borrowing has had severe consequences in the global north as well. In the United States hundreds of thousands of Americans have lost their homes because they have not been able to pay unreasonable interest on sub prime loans. This then led to

7

the global financial crisis that we are currently experiencing. We do not know how deep this depression will be yet, but confidence in the banks and economic system is already breaking down and the economy of a well known welfare society, Iceland, has collapsed.

Yet, because global financial systems are so interdependent, those suffering the most from the financial crisis are from the world’s poorest countries. They have depended on aid and investment from developed countries and made themselves vulnerable by opening to global markets. Now the danger is that they will lose the level of development they have achieved and be set back into poverty. Whilst welfare systems in the north will support those set back by the global financial crisis, aid budgets for the southern world are tightening and at risk of failing.

3) “Capitalism is all about economic growth and creating wealth which is supposed to ‘trickle down’ and benefit everyone eventually. It is not however very good at distributing the wealth it creates, thus widening the gap between rich and poor and achieving growth at unacceptable cost to the world’s limited resources, to the environment and to society, its cohesion and its values.”

4) “Capitalism prefers the free market and private enterprise to governments which it regards as inefficient and likes to shrink. This leads to problems when privatising public services like the water supply, which become subject to commercial pressures instead of meeting basic needs. Markets need regulating by governments so that large companies and monopolies are kept under control, and markets cannot do everything including providing roads, education, social security and care for the environment.”

It seems that the biggest problem of market capitalism is that the only value that counts is money. In order to flourish, or at least to fulfil basic human needs, we need strong government and an active civil society. Churches can play their part, not just through campaigning but by being centres of civil society and encouraging a set of alternative values.

5) “Behind many of these problems are issues of power, and where there is an imbalance of power (between rich and poor countries and people, at global institutions like the WTO and the World Bank, between the movement of capital and restrictions on the movement of labour, where international companies have more influence than governments) there tends to be injustice.”

What is to be done?

“One obvious suggestion is to change the people who run the global economy, but there is little evidence that they do change despite the efforts of religious and moral movements. This approach is certainly not enough by itself.

“A second suggestion is to change the structures that keep and make people poor, such as working for fairer trade agreements, keeping countries out of unmanageable debts and introducing measures to combat climate change. These changes require good policy work plus effective advocacy and mobilisation of people to persuade governments to act. These changes also take time and meanwhile people suffer and need support, and thus aid programmes have their place.

“A third suggestion (and these suggestions are not mutually exclusive) is to try to change the culture or the inner spirit or the values of the global economy away from a narrow concern with growth and consumerism towards sustainability, a more rounded view of human development and, some would say, ‘happiness’.

“A fourth suggestion may be the most fundamental and that is to redress imbalances of power wherever we can.”

The global economy, as powerful as it seems, is fully dependent on human well-being and on our ecosystem. We need to acknowledge that both wealth and growth have their limits because we are finite human beings with finite resources at our disposal. The ideology of market

8 A Just Life or just life? – Markus SIDOROFF: Approaching Globalisation

www.sxc.hu

capitalism promises unfettered growth that is just not possible and the mechanisms of the market treat human beings as controllable units in economic calculations. To be realistic about all of this is one way to begin to redress the balance of power. This also includes issues of sustainability: sustainability can only be realised when people are empowered to play a democratic part in the market, not only by decision making but also by setting the agenda and participating in deliberation.

Due to efficient campaigning and advocacy work, awareness about the global economy and its negative effects has risen tremendously in the west. Consumers today are more aware than before and many want to buy ethically produced goods. Workers and producers, taking charge of their own work and eliminating the middleman, form one of the most important parts of the Fair Trade movement. Therefore international companies are slowly facing pressure to reform their exploitive practices. So there are at least some signs of things going in the right direction.

Where does Christianity come in?

Michael TAYLOR has a considered response: “Even those who strongly disagree and believe Christianity is highly committed, for example, to social justice, have to acknowledge that it doesn’t have all the answers. Christian insights have to engage with the insights of other disciplines like economics if sensible policies are to emerge.

“Whilst it is important to love our neighbours, Christian compassion cannot stop at charity and personal kindness. If compassion is not willing to change structures then it is little more than self-preservation (keeping things the way they are) and not compassion at all.

“Christians should draw on the insights of their tradition such as the Jubilee idea, the realism which recognises how incorrigibly self-interested human beings can be, the priority given to the poor in the Gospel and ideas of justice,

as long as they don’t ‘apply’ them in simple and naive ways without engaging with more factual information and other relevant disciplines.

“Human beings may be `sinners` but they are also made in the image of God which means they are essentially creative beings, so that Christians above all, wherever they work and play and live, should be interested in finding new solutions to old problems, not just mending the world but ‘making all things new’, including the economic order with its tensions between competition and co-operation, growth and sustainability, public and private enterprises, freedom and regulation, fair distribution and rewards, etc.

“Finally Christians should be hopeful people which does not mean they are superficial optimists or believers in endless progress. They are not utopians but they do believe that any situation is open and not closed (hopeless) where more good can be done and more justice and happiness achieved. If things can never be perfect they can always be better.”

Being a Christian means a call for action. Christ did not only give us beautiful images and an ideology about loving our neighbour. He concretely showed us how to do it by healing the ill, dining with sinners, by taking the side of the rejected. He even took it to extreme by giving up all his glory and becoming one of the rejected and poor himself. We are given an opportunity to follow his example and do our share. This should make Christianity a practical way of life, following Christ in meeting the disempowered and excluded and being part of an agenda for change. Michael TAYLOR left all with a resonating challenge: to not be afraid when offered influential positions with power and responsibility - good people are needed.

Michael TAYLOR’s thorough presentation set a precedent for the rest of the conference, in which participants learned more about globalisation and justice, individual and collective responsibility from different perspectives. Some of the inputs can be read elsewhere in this journal.

9

Being a Christian means a call for action. Christ did not only give us beautiful images and an ideology about loving our neighbour.

Globalisation and Justice: Contradictory Forces?

Peter PAVLOVIC

I. What is Globalisation? Raising the Gap between Rich and Poor

The current understanding of globalisation has economic connotations. Globalisation is thought of as a process characterised by the elimination of tariffs and customs barriers, instantaneous movement of capital and the rapid creation of new investment opportunities. Free movement of capital and goods are the core signs of globalisation as we know it today. The questions that provoke most interest relate to the consequences of this process. The issues of who benefits from it, the expected outcomes and how shortcomings can be addressed are all questioned. One of the often discussed negative sides of present globalisation is its imbalance. On the one hand there are the reported positive effects of the process – growing exports, increased possibilities for exchanging goods and capital and expanding the GDP of individual countries. On the other hand, we have to ask, are the benefits of the process equally distributed? Who are winners and who are losers of this development?

The average per capita income in high-income countries in 2001 was sixty times higher than low-income countries. Precise figures on the development of the worldwide income gap however show a more complex picture. In recent years the income gap between the richest and poorest 10% of the world’s population has increased considerably. The income gap between

the richest and poorest 20% has only grown slightly and if one compares the richest and poorest 25% (33% of the world population) there is by contrast a slight closing of the prosperity gap. This is caused above all by rapid economic growth in China and India, where together approximately one-third of the world’s population live.

A similar picture emerges from a countryrelated comparison of the annual growth rates in per capita income. The developing nations have achieved somewhat higher average growth rates in the last 25 years than the industrialised nations, whilst the poorest countries show much lower growth rates. More than anything else, this shows that there is a growing income gap among the developing nations themselves.

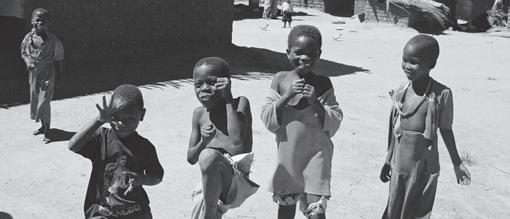

A number of reports demonstrate that globalisation can help overcome poverty, and examples from all over the globe demonstrate this. Unfortunately this is not a universal happening. Equally, there are many examples proving that globalisation makes the rich richer and the poor poorer. This is the case particularly, but not only, in sub-Saharan Africa. These findings reflect the concerns of a great number of people globally, not just those in affected regions.

Most of the gains of globalisation in terms of poverty reduction have benefited only two countries, China and India. Whilst in South America, it seems that trade openness has led to a rise in income inequalities and one entire continent, Africa, has actually become even more marginalized than before.

MOZAIK 22 10

Rev.Dr.Peter Pavlovic is the Study Secretary of the church and Society commission of the conference of European churches, working on a dialogue between churches in Europe and European political institutions with particular focus on the themes of European integration, globalisation and environment. as the Secretary of the European christian Environmental Network, he works to promote care for creation in the agendas of churches in Europe.

II. Globalisation beyond Economy

Globalisation, as we know it, is a process of increasing economic relations. This does not necessarily mean the same thing today as it did in the nineties. Globalisation began as an economic issue and was particularly made possible by technological changes. The phenomenon of globalisation later took on additional characteristics, ones that cannot be overlooked today. These characteristics include:

Whatever else, this means that globalisation is most likely an unstoppable phenomenon. It can be shaped; but in what direction and what is wrong with the current shape of globalisation?

»

Full mobility of capital and goods

» Spread of information technology

A drive for uniformity around the

» values steering the process of continued globalisation

In 2004 the International Labour Organisation (ILO) created a high-ranking commission of internationally respected personalities called the World Commission on the Social Dimension of Globalisation. The Commission produced a report entitled A fair globalisation – creating opportunities for all. The document offers thorough analyses and very specific proposals that address the crucial deficiencies of current globalisation. It emphasises the following points as significant issues for shaping globalisation:

Greater inequalities

» An erosion of nation states

» Increasing impact on culture and/or

» national identity

Increasing impact on democracy,

» raising the question of whether global corporations have too much power over national governments.

It would be a mistake to limit our understanding of globalisation to finance and economics; globalisation has social and cultural dimensions also. One of the greatest problems of globalisation is the phenomenon of migration and the unavoidable problem of the greater mobility of persons compared to the mobility of goods and capital. Equally, globalisation has become a spiritual phenomenon. At the conceptual level, barriers of time and distance that previously existed have been eliminated. Time and distance no longer hinder immediate worldwide relations. Important decisions can now be announced simultaneously all over the world.

A focus on people: Just globalisation means respecting » the rights of all people to fair working standards and self-determination and the protection of their cultural identity and autonomy. Gender equality is essential. The role of a democratic and effective state: The » government of a country must be able and free to manage the integration of the national economy into the global market, and to provide social and economic opportunities and security to its citizens.

Sustainable development: Just globalisation requires » sustainable development and interdependent and mutually reinforcing pillars of economic development, social development and environmental protection.

Productive and equitable markets with fair rules:

» Equal opportunity and enterprise need to be promoted by sound institutions for a well-functioning market economy. This must be represented in the rules of the global economy in a way that can be accessed by all countries. The rules also need to recognise the diversity in national capacities and developmental needs.

Globalisation with solidarity: There is a »

11

In recent years the income gap between the richest and poorest 10% of the world’s population has increased considerably.

shared responsibility to assist countries and people excluded from or disadvantaged by globalisation. Globalisation must help to overcome inequality both within and between countries and contribute to the elimination of poverty.

The call for solidarity is the core message. It has been formulated not only by the ILO but also by many churches and church-related organisations all over Europe and the globe. Alongside documents produced by individual churches in Europe, which formulate their respective responses to the challenge of globalisation, there are also documents by ecumenical organisations such as the WCC and CEC.

The Conference of European Churches has focused its attention on the impact of globalisation on the European context and have elaborated on this in the document ‘European Churches: Living their faith in the context of globalisation.’ Several points give the discussion on the impacts of globalisation in Europe a certain significance, differing from the situation in other continents. This difference is the existence of the European Union with its influential political structure that is able to shape the development on the continent. Its influence extends even beyond the continent’s borders and the sphere of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). The impact of globalisation in CEE differs from that of Western Europe. A careful examination of the rapid transformation of economy and society in CEE over the last two decades would aid in understanding many of the questions linked to globalisation. The key term for understanding this rapid transformation from the churches’ perspective is justice.

12 A Just Life or just life?

– Peter PAVLOVIC: Globalisation and Justice – Contradictory Forces?

III. Globalisation and Justice

One of the most influential contemporary accounts of justice is the work of John Rawls. In his book Theory of Justice (1971) Rawls defines justice simply as fairness. There are two steps involved in supporting this definition. First, he establishes what is called a neutral starting point, i.e. a position which is removed from all external influences and prejudices. Justice can then be defined without any conflicting influences and is allowed to follow the fundamental principles of equality and liberty. His definition is then based on two fundamental principles:

1. Each person is to have an equal right to the most extensive basic liberties compatible with liberties for others.

2. a. offices and positions must be open for everyone under conditions of fair equality of opportunity (equality principle)

b. they are to be of the greatest benefit to the least-advantaged members of society (the difference principle)

To broadly define justice as fairness is certainly appealing; the question, however, is whether it is sufficient. Many are critical of such an approach and turn their attention to the basic presupposition of the definition – a neutral starting point. These critics argue that we do not have a neutral starting point and that this is an unachievable goal. Every theory of justice arises within and expresses a particular moral and political ideal. It is not possible to define justice in objective terms. It is always necessary to ask about the circumstances and context in which the justice we seek can be practiced. We find this in the way that the Bible approaches justice. Justice is a key concept in biblical tradition and Christian social ethics. In the Bible it is connected with peace, freedom, redemption, grace and salvation. In ancient philosophical and theological discussions the idea of justice

was interpreted as a fundamental principle of social order. It was considered that everyone has a right to be recognised as a person and to lead a fulfilling life. This individual right found respect in a society where all members played their part and received their due. So at the same time, each individual must respect the rights of others and those of the social body. Only in this way can justice safeguard peace in society and in the world.

The relevance of Christian theology to the real world is grounded in the recognition of the relationship between justice and other basic values in the Bible. Respect for these basic values is at the heart of Christian teaching and their promotion and application should guide Christian lifestyles.

These values are all interdependent in a way that gives rise to a vision for human life in all its fullness. It is a vision that discourages the extremes that happen when some of these values lose their relationship to others.

The experience of Central and Eastern Europe with globalisation provides a relevant example. Countries in this region have painfully endeavoured to overcome a globalisation of another kind – that of a totalitarian ideology. The experience of CEE countries with communist ideology and real life socialism helps us to understand what it means to talk about a ‘just’ society. In communism justice was reduced to its distributive function, justice without freedom; it was a society of equality, but without social responsibility. Serious consideration is called for in order to learn from this experience. The relevance of this experience is not merely historical, concerning only our past, but it is also significant for understanding the nature and future of global capitalism. It acts as a kind of mirror, exposing globalisation’s negative side. This is especially important for people who once lived in countries behind the Iron Curtain and who are now experiencing the positive effects of opening their borders to globalisation.

Biblical justice is not a reality separate from secular justice.

13

It is not possible to define justice in objective terms. It is always necessary to ask about the circumstances and context in which the justice we seek can be practiced.

The core of biblical understanding is that freedom from sin is a necessary part of every human activity and area. What we say about justice in the area of biblical thought has to remain meaningful and connected with everyday reality. Talk about justice cannot be superficial. This means that justice can only be understood as a historical reality and in this sense justice is not just about legal process but is also about ethical maturity.

IV. Criteria of Justice

Justice is a practical, not abstract, term. Whatever we mean by justice, the final criterion concerns its implementation. Justice is often limited to the question of law and legal proceedings. Although this dimension of justice must not be underestimated, neither ought it to be considered as the only significant dimension. Limiting justice to its legal form is neither adequate, nor satisfactory, nor reflecting a biblical approach. Limiting justice to the legal and formal matters, as well as narrowing it to distributive equality is very often a frame in which justice is discussed in the current context of globalisation. It is right to talk about distributive justice but this alone is far from sufficient; in order to unpack the full implications of justice much more needs to be said. Inseparable from any meaningful talk of justice is its personal dimension, as well as a dimension which speaks about ex ante justice (justice before the event). Social balance and social justice are integral parts of the concept of the social market economy. They are often considered ex–post (justice after the event), through the system of redistribution. Efforts to create ex ante justice are equally important and probably more effective. Ex ante justice means creating equal access to the means of production, equality of opportunities, and requires acting on a vision of the future that will fairly benefit everyone. Ex ante justice includes a just limit to economic competition

and a widening of opportunities. There are strong ethical arguments in support of “positive discrimination” in favour of countries, peoples and groups who have been excluded in order to strengthen their economics. Economic potential that has long been latent should be released by improving access to training, savings and loans and legal assistance in order to enable them to contribute towards development.

The principle of gender equality is linked to this question of opportunity, since women are frequently subject to the multiple disadvantages of poverty, gender restrictions and gender based violence; to which are often added the disadvantages of being part of an ethnic or religious minority. Women often have less access to economic resources, education or legal protection, and in many world situations they are excluded from making decisions that directly affect them.

There is also a time-related dimension. The question of justice between generations means that policy must also calculate to provide resources and institutions for future

14 A Just Life or just life? – Peter PAVLOVIC: Globalisation and Justice – Contradictory Forces?

generations. Most importantly, states and corporations have a responsibility to save environmental assets for future generations; this includes conserving the diversity of the social and cultural environment.

We might now come to the conclusion that a deficient understanding of justice is one that is limited to the law and stripped of its ethical and spiritual aspects. This leads to two significant consequences that can be seen all around us. Reduced understanding of justice is a cause of:

- an imbalance between the economy and the society. Where the benefits of globalisation have been unequally distributed, both within and between countries, there is growing polarisation between winners and losers. This is made worse when global trade rules and institutions prevail over social rules and social institutions. Goods and capital move much more freely across borders than people do. In times of crisis, developed countries have wider options for macroeconomic policy, while developing countries are constrained by demands for adjustment. International policies are too often implemented without regard for national differences. There are urgent consequences following from all this and reinforcing inequalities. The rules of world trade today often favour the rich and powerful and work against the poor and the weak, whether these are countries, companies or communities.

- an imbalance of power between the global economy and national governments. Institutions of governance today – whether national or international – do not adequately meet the new demands of people and countries for representation and advocacy. The lack of public trust in global decision-making creates new tensions between representative and participative democracy. International organizations, in particular the United Nations and the World Trade Organization (WTO), have come under increasing pressure to implement fair decision-making and greater public accountability. Global markets lack the supervision of public institutions, which in many countries

provide national markets with legitimacy and stability. The present process of globalisation has no means to maintain a balance between democracy and the market. These two imbalances lead to the subversion of social justice and are consequences accompanying current globalisation.1

V. Conclusion

Globalisation, because of its link to poverty and the concept of justice, is undoubtedly an issue of serious concern. The long-standing wealth inequality, widened by the current shape of globalisation, cannot be ignored. Aware of the biblical commandments that call all to stewardship, it is important for the churches to affirm the importance of mutual responsibility, trust and accountability. The economy has to serve life for all. The economy must not work to bring benefits for only a small elite.

In order to do so, the relationship between politics and the economy has to be clarified. The role of ethical judgment in this process has to be restored on both national and international levels. In the current stage of globalisation there is a critical need for an ethical orientation. Economic policies alone cannot create values; the market alone cannot create solidarity between peoples.

It is clear that further work needs to be done to ensure democratic control over administrative and economic players. Ethical behaviour at personal and organisational levels is essential to ensure improvement. The church has a substantial role in identifying and analysing the economic and social processes around us, in opening the way for ethical behaviour and finally in being the voice of the victims of the political, social and economic systems that surround us.

15

In the current stage of globalisation there is a critical need for an ethical orientation. Economic policies alone cannot create values; the market alone cannot create solidarity between peoples.

1 These imbalances are noted in a number of documents undertaking an effort to analyse globalisation and its consequences. See e.g. A fair globalisation – creating opportunities for all. ILO, 2004, as well as European Churches living their faith in the context of globalisation, CEC/CSC, 2006.

Connections with the Natural World

Sarah PILLAR

Kevin lived as a hermit in the south of Ireland in the early 7th century. In his vocation to seek God, Kevin chose to live fully dependent upon and engaged with his environment. Nature was to be embraced as the place to experience God. Once, whilst praying in stillness and silence, a blackbird settled upon the palm of his hand. She began to build her nest. Kevin faced a choice: to withdraw his offer of openness before this availability became too costly or to value the fragility of this encounter above his own comfort, to hold his exact posture … for a long time! For Kevin, as this beautiful story recounts, the initial, humbling thrill gave way to endurance, pain and sustained commitment. Through what had now become an extended prayertime, Kevin’s aching open hand mirrored his open heart to God. He held the nest until the chicks learnt to fly.

Kevin’s costly hospitality speaks to us in a way facts and figures cannot. As God reveals to us the treasures of His creation should we simply catalogue them that we might ‘own’ them, to marvel and move on? Rather, here is a challenge to hold an open hand to the increasingly fragile world of which we are a part. We learn to value God’s creation, glimpsing His value of us.

In the words of a traditional Irish blessing, we draw together both the challenge of Kevin’s costly nurturing care and God’s tender care for us:

May God hold you in the hollow of God’s hand.

MOZAIK 22 16

Sarah PILLAR is from the Northumbria Community. Visit the Northumbria Community online at: www.northumbriacommunity.org/

The Discourse of Debt: Who owes who?

Rosie VenneR

A man is standing by a running tap. It flows rapidly, pooling in great puddles around him. He spots a woman walking by. This woman is in debt to him. Ten years ago she borrowed a bucket of water to grow some seeds that he had sold to her (the seeds were faulty and the harvest failed). With interest, she now owes him ten large containers of water. The woman is on her way to her own tap, two hours walk away, to fetch water for her children. He waits. The sun rises overhead and begins to fall again. The woman returns. He takes the full bucket from her and she goes home to her children, empty-handed. The same will happen again tomorrow. The man is standing by a running tap. It flows rapidly, pooling in great puddles around him.

Introduction

The world’s poorest countries pay almost $100 million every day to the rich world.

Jubilee Debt campaign1

Debt is a word on everyone’s lips. We are particularly conscious of individual debt and of the global debt crisis affecting the world’s financial markets. However, in the midst of this, let us not lose sight of the $400 billion worth of unpayable debt that keeps some of the poorest countries of the world in poverty, and robs the world’s poorest people of basic healthcare and education. The majority of this debt is left over from reckless lending by the rich world in the 1960s and 1970s, and although some progress has been made in terms of debt cancellation,

thanks to impassioned campaigning both in the global South and North, there is still a long way to go. The Jubilee Debt Campaign is calling for full cancellation of all unjust and unpayable debts, an end to the harmful conditions attached to debt cancellation, and transparency in all future discussions and negotiations.

I’m not an economist. What interests me most is the discourse of debt, the stories we construct, the questions we should ask, and the new narratives that we need to unearth to get to the heart of who owes who?

The Language of Debt

Language might seem like a strange place to start, but I think it is central to how we think about the issues surrounding debt. Words and phrases in campaigning become commonplace and we forget to interrogate them for what they might be hiding. Environmental campaigners are abandoning the term ‘climate change’ because it is either ignored as something innocuous or it is increasingly hijacked by conservative climatesceptics as something natural, not caused by our overconsumption of resources. Instead we find new phrases like ‘climate chaos’ and ‘climate crisis’, which better emphasise the potential catastrophic impact of global warming if it is not averted, particularly on the world’s poorest communities. If ‘climate change’ has been deconstructed in the world of environmental campaigning, than phrases like ‘debt relief’ certainly need some careful attention. Debt relief is at best a euphemism; at worst it is masking the true picture of past and present injustices.

17

Rosie is Links Worker for British SCM. She lives in Birmingham, a city where ten years ago 70,000 people gathered for a peaceful demonstration urging the G7 leaders to cancel unpayable and unjust poor country debt.

The language of debt ‘forgiveness’ paints a simplistic picture of the North as beneficial donor and the South as guilty debtor and in doing so is perpetuating a myth. What we need to talk about and uncover is unpayable debt, unjust debt and illegitimate debt. These phrases were first used by campaigners in the South but I’m pleased to see that they are increasingly entering the rhetoric of all debt campaigners. Debts on loans that were knowingly and irresponsibly given by the North to dictators and oppressive regimes thirty years ago are illegitimate and should be cancelled in full. We should also include under the umbrella term of unjust debts those incurred when projects failed due to bad advice by lenders and those which built up when money was lent on unfair terms at excessively high interest rates. Language matters a great deal; it needs to more accurately reflect and reveal the power structures involved in international debt.

Turning the Tables

Who is aiding who, and who owes who a debt? That is the question we have to ask today.

Kumi NaiDoo2

Who is aiding who? It’s a good question and one that doesn’t get asked often enough. The $100 million a day that the poorest countries are paying as debt to the rich world, scandal though that is, is a mere trickle compared to the torrent of wealth they are losing to the North in terms of people and resources. Think of the so-called ‘brain drain’ – the migration of highly skilled people from the South to the North – and the benefits we reap in the rich world from doctors, nurses and technicians, who were trained at no cost to our economy and yet sustain our health services, while children die in countries like Malawi for want of adequate

healthcare. Italy has one doctor for every 238 people. Malawi has one doctor for every 25,000 people. That’s before we begin to add up the mineral wealth of poor countries that is siphoned off every day by multinational companies with very little profit invested in the communities it came from. There is a continual accumulation of wealth in the North at the cost of the South. Who is aiding who? Let us keep asking the question.

Who owes who a debt? Another important question. To answer it we need the oral stories of slavery and the transatlantic slave trade, the stories of colonialism and the stripping of resources that has occurred over generations. We also need to acknowledge the legacy that these injustices have left behind. We need the stories of the earth itself – of deforestation, pollution and loss of bio-diversity – and of people displaced from ancestral land in the name of profit and development. Who owes who a debt? It’s an uncomfortable question, but let us listen carefully to the answers.

Climate – a new Narrative

Unless the carbon debt is tackled, we will all be environmentally bankrupt. andrew SimmS (New Economics Foundation)3

There is a growing awareness of the concept of ecological debt and this calls for a new narrative of global debt. Industrialised countries in the North have built up huge carbon debts in recent generations. We are not only using up more than our fair share of fossil fuels but in doing so we are altering the climate itself, a burden which will be felt most by the world’s poorest countries, as floods, the rising sea-level and temperature changes make vast areas

18 A Just Life or just life? –

Rosie VENNER: The Discourse of Debt: Who owes who?

Italy has one doctor for every 238 people. Malawi has one doctor for every 25,000 people.

of land in the global South uninhabitable. The Jubilee Debt Campaign estimates that the rich world owes an annual carbon debt of more than $1 trillion. With the serious consequences of this debt in mind, we can no longer characterise the global South as indebted; the poorest countries are in carbon credit.

Earlier this year the UK government announced a new scheme (the international Environmental Transformation Fund) to help the poorest countries in the world respond to climate change. The hidden, and worrying, detail was that the help will be offered mainly in the form of loans, which will need to be paid back with interest. The incongruity of further indebting poor countries to enable them to respond to a crisis that we have made is something that needs to be challenged. Ecological debt needs to be the central narrative of international conversations around finance and development in the years to come.

Theologies of Debt

if the debtor is in a difficulty, grant him time till it is easy for him to repay. But if ye remit it by way of charity, that is best for you if ye only knew.

Qur’an 2:280

We don’t need to look far for spiritual narratives around debt. We are steeped in the language and stories of debt, bondage, freedom and justice, throughout the Old and New Testament. The Jubilee Debt Campaign takes its name from the biblical year of Jubilee which speaks of release from debts, re-ordering and redistribution of wealth. In our interconnected world, we can also look to our Muslim brothers and sisters for alternatives to unjust debt. One of the pillars of Islam, zakar or almsgiving, prevents accumulation of money in the hands of the wealthy, continually moving

it from the rich to the poor. The Qur’an also condemns the practice of interest (riba in Arabic):4

Those who devour interest will not stand except as he stands who has been driven to madness by the touch of Satan … allah has permitted trade and forbidden interest … allah will deprive interest of all blessing (2:275-6)

That phrase ‘devour interest’ stands out. To devour something implies greed and over consumption. We fool ourselves if we think that overindulgence will bring us blessing and life in all its fullness. It will always be at the expense of the poorest. We are not created as creditors and debtors; we are created as connected people. Fullness of life does not come from uninhibited growth and consumption – but from an equal sharing of risk and responsibility. We need ears to hear and learn from the unjust stories of the past and present, and we need new storytellers who will speak truth to power and deliver us all from unjust debts.

Take Action

Go to www.jubileedebtcampaign.org.uk for up to date campaign details and resources from the UK based Jubilee Debt Campaign. The website also lists contact details for Jubilee Debt movements in other countries.

(endnotes)

1 http://www.jubileedebtcampaign.org.uk

2 Speaking at the Journey to Justice event in Birmingham 18 May 2008. Watch the speech on Youtube here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o3jXGDV5avo

19

3 Andrew SIMMS, 2001. an Environmental War Economy: The lessons of ecological debt and global warming. New Economics Foundation.

www.flora.kommune.no/archive http://www.barynya.com

4 Ajaz Ahmed KHAN and Helen MOULD, 2008. islam and Debt, Islamic Relief.

James Trewby works for the bosco Volunteer Action (www. boscovolunteeraction. co.uk), the overseas volunteering organisation of the Salesians of Don bosco in the UK. The Salesians are a Catholic religious Order whose mission is to the young and the poor. He has just begun a part-time PhD in Development education at the Institute of education in London. This article is an edited chapter of James Trewby’s MSc dissertation. For additional references please contact him at bova@ salesianyouthministry. com.

Campaigning and Development Education

James Trewby

Introduction

For a number of years it has been my intention to work for and with the poor in a developing country. However, I have begun to question this vision due to a growing awareness that the progress of developing countries is impeded by various ‘root causes’ of poverty, some of which can be traced back to developed countries. These include trade rules which favour richer countries over poorer ones, debt from loans which were sometimes of questionable legitimacy, corruption and poor governance. Campaigning in developed countries is therefore an important and useful role. Development education can be seen as a ‘multiplier’ of campaigners; making people aware of the issues and possible actions in the hope that they too will begin to campaign (and tell others, thus becoming development educators themselves). These thoughts are crystallised in a story told by MaCeDo in the Foreword to FreIre’s ‘Pedagogy of Freedom: ethics, Democracy and Civic Courage’. In the story a white middle-class female has given up a successful business career in order to work with battered mothers from under-privileged communities in an american inner-city area, but the twist in the story lays the basis instead for the case of campaigning and development education:

“enthusiastic in her altruism, she went into a community centre where she explained to one of the centre staff how much more rewarding it would be to work helping people in need than it would be to work just to make money. The

african-american staff member responded: “Ma’am, if you really want to help us, go back to your white folks and tell them to keep the wall of racism from crushing us”.1

Campaigning

“The poorer must help themselves” (CHaMbers 1983, 3). The process of development, despite all the contested meanings of the concept, must largely be driven by the peoples concerned. This does not mean that they must develop on their own but rather that their development will not be developed by external actors with external interests but by their own efforts with support from outside. This is reflected in the development industry’s frequent use of the word ‘empowerment’. True there is a distinct “lack of clarity” (sen 1997, 1) around this word, sometimes used as a “fashionable buzzword” (Page and Czuba 1999) to provide “warm and nice” connotations (Cornwall and broCk 2005, p4), yet there is little doubt that for development to take place developing countries need to be empowered, both as nations and individuals. FreIre and others have argued that this empowerment is blocked, intentionally or otherwise, by the actions (or inaction) of more powerful countries. This serves dependency and exploitation and leads to underdevelopment.2 realities such as debt, unfair trade rules, climate change, corruption and the arms trade that benefit the developed world have consequences in the developing world. Hence FreIre calls for “conscientisation”, a process which would “embrace a critical demystifying moment in which structures of domination are laid bare and political engagement is imperative” (wesT 1993, xiii). He

MOZAIK 22 20

also observes that development interventions themselves can be disempowering if they follow policies of financial or social assistance which only attack the symptoms, but not the causes, of social ills. FreIre characterises such policies as violent because the lack of dialogue imposes “silence and passivity” and robs them of responsibility for their own future.3

Two arguments will now be made: firstly, that it is possible for ordinary people to act to remove some of the barriers to development; and secondly, that they have a responsibility to do so. references will mostly relate to the experience of campaigning and development education in the uk but the lessons are relevant throughout europe.

It is important to note that while “it would be misleading to suggest that human beings can control all the external forces that may shape their future… many of the major problems currently facing us are human-created”.4 The question is then: what can be done about these? This article suggests that part of the answer can be found in campaigning (sometimes referred to as activism). Campaigning is “part of the discourse and practice of democratic politics and social change”; it offers opportunities for citizens to “have their views heard and to influence the decisions and practices of larger institutions that affect their lives”.5 Campaigners, individuals and groups make use of many methods including protests, boycotts, ‘shareholder activism’, direct action, petitioning and public shaming in order to advocate change to decision makers and to hold politicians, corporations, opinion leaders and power structures to account.6

There is no doubt that campaigning, and civil society in general, plays a large role in the world today; “from human rights to landmines, sustainable development, and democratization, global problem solving is increasingly being left to an agglomeration of unelected, often unaccountable transnational civil society actors” (FlorInI 2001, 29). In the uk many campaigns have reached large sectors of the population and have showed that the british

21

If we are persuaded to accept that ‘something can be done’, we have then to talk about what should be done?

public has “both the capacity and the desire to engage in shaping foreign policy” (HaMPson 2006, 8). whilst charity organisations are often involved, campaigning is seen as representing a call “not for charity but for justice” (benn 2005, 1). This statement was made by Hilary benn, then secretary of state for International Development, and reflects campaigning’s closeness to politics; campaigning is indeed a form of political action.

some campaigners are motivated by principle alone but others are fixed on success. To reward them, there have been many victories. There is the legislation regarding landmines (TussIe and Tuzzo 2001) and one of the most widely acknowledged is the success of the Jubilee Debt Campaign. “who would have thought back in the late 90s when the Jubilee 2000 debt cancellation was launched that many countries like Tanzania and Mozambique would achieve liberation from debt bondage?” (HowleTT 2007).

If we are persuaded to accept that ‘something can be done’, we have then to talk about what should be done? First one must recognise the responsibility to be informed about the issues and the possibilities for action. Claire sHorT, then secretary of state for Development, wrote that it is “important to understand something of our responsibilities, from local to national and international level, and how individuals, governments and others respond to these” (cited in sMITH and raInbow 2000, 6). It is a duty not only to understand our responsibility in the world, but we also have a right to be taught about our global citizenship.

It can be argued that the citizens of developed counties have a moral responsibility to campaign on development issues. This is especially true for the citizens of the uk whose on-going history of exploitation (through trade and otherwise) allowed their country to maintain a dominant position. british citizens have more direct access to the major stakeholders and creditors in the international corporations and organisations which control access to

both economic and political power. The greater wealth of developed countries along with their technological advances gives them great opportunity and power to influence the course of development and exploit new possibilities for campaigning. CHaMbers comments on this and suggests that “since our scope for action is greater, so, too, is our responsibility”.7

Development Education

The importance of development education lies not only in our shared responsibility to act and be informed but in the need for a democratic movement for change. Democratic ideals are relied upon in campaigns targeted at both political and corporate figures. Those in power answer to their voters, shareholders or customers and a campaign is most successful when it can claim to represent a large proportion of voters, shareholders or customers; “when the people lead, the leaders will follow”.8 It is therefore important to attempt to increase the number of campaigners; “the political will to develop and implement the broad policies necessary to generate lasting global change can only be found if a critical mass of public opinion is engaged to influence decision makers”.4

whilst creating access to information is only a first step, it is vital. It is “widely conceded that the public [in northern countries] knows little about international development or about the connections between development there and life here” (sMIllIe 1998, 26). Images of the developing world presented by the media are often shallow and simplistic, leaving a need for more thorough development education. CHaMbers makes an intriguing proposal, calling for a curriculum “for the non-oppressed” which would enable “those with more wealth and power to welcome having less”.5 something more radical is perhaps needed, that is a system of education for developing countries which is “painful yet empowering” (wesT 1993, xiii) – an education

22 A Just Life or just life? –

Development Education

James TREWBY: Campaigning and

www.sxc.hu

that awakens and equips the conscience, drawing attention to the reasons why one country is more wealthy and powerful than another, questioning whether this is fair and suggesting and supporting actions such as campaigning. This is one understanding of ‘development education’.

Development education formally began in the uk in 1966 when oxfam appointed a staff member to develop an education programme (sTarkey 1994, 13). It is important to distinguish development education from simply learning about developing countries. Development education learns from and with, to encourage understanding and to foster a sense of solidarity. according to oxfam, development education aims “to develop existing concerns, challenge poverty and injustice, and take real effective action for change” (oxfam 2004, 2).

The following are key elements:

“knowledge and understanding:

» Diversity

social justice and equality

» globalisation and interdependence

cation but go beyond this by crowning the education process with action; “the process of education for development can be thought of as a three-step cycle, consisting of an exploration stage, followed by a responding phase, and leading ultimately to an action phase” (FounTaIn, 16). given the reality and urgency of the subject, this final step is simply justified; “action is needed because analysis and understanding are not enough. nor is empathy. nor, even, is feeling empowered, without some hope of action and change” (grIFFITHs 2003, 113). It also serves an educational purpose, reinforcing and making concrete the issues and skills that have been taught.

»

» sustainable development

Peace and conflict skills:

» ability to argue effectively

Critical thinking

» respect for people and things

»

» Co-operation and conflict resolution

Values and attitudes:

» empathy

sense of identity and self-esteem

»

Development education, as it exists in the uk today, owes a debt to the brazilian educator Paulo FreIre. FreIre strongly emphasised the need for action. For him, it was important to avoid the pitfalls of verbalism, meaning words without actions, but just as important to avoid are the pitfalls of action without theory, action for action’s sake. Instead he called for ‘praxis’, “the action and reflection of men upon their world in order to transform it”. FreIre’s many insights are crucial: “no pedagogy is neutral”; “the kind of education that does not recognise the right to express appropriate anger against injustice, against disloyalty, against the negation of love, against exploitation, and against violence fails to see the educational role implicit in the expression of these feelings”; “histories of oppression and suffering must be recounted… Memories of hope, too, must be offered… These should include the voices of the oppressed and respect for their integrity and subjugated knowledge.”3

»

Commitment to social justice and equality

»

Value and respect for diversity

» sustainable development belief that people can make a difference”

Concern for the environment and commitment to

»

(oxfam 2004, 3).

others use similar elements to explain development edu-

wherever it takes place, and there are calls to include development education in national curricula, development education is necessary to inform everyone of the world they live in and of their responsibility. where it leads people to action, it enables people to truly engage with the issues and to campaign effectively. Campaigning itself should reflect this education and include elements of it when seeking supporters and lobbying decision makers.

23

It is important to distinguish development education from simply learning about developing countries.

Challenges

so far we have pursued a positive and idealistic view of development education but in many ways it opposes the dominant ideology and, as FreIre writes, this type of education is “swimming against the current...and those who swim against the current are first being punished by the current and cannot expect to have a gift of weekends on tropical beaches.”9

Development education does not take place in a vacuum; many people already have a certain amount of knowledge, be it perceived or actual. generally speaking “the mass of the general public has little notion of the conditions of life for the people of the world’s poorest regions” (sTarkey 1994, 13), or indeed of poverty in the uk. a minority are more aware due to the increased inclusion of development education within the national curriculum. while such knowledge can be built upon, other preconceived ideas can impede development education and stereotypes abound. The majority of these stereotypes are negative without recognising positive elements. Development education faces a challenge to reverse these stereotypes. If “all students need to be able to deconstruct their own cultural baggage of inherited knowledge” (nICHolson 1996, 80), it is the job of campaigners and educators to enable this process. a related difficulty comes from the mixed messages sometimes transmitted by development ngos. Their efforts to provide development education sometimes conflict with their desire for fundraisers; for example whilst work in schools is attractive to supporters “there is an ongoing debate within most of the ngos about the importance of providing resources for schools, compared with the rest of their work. when funds are short, it can sometimes be seen by some in the agencies as a luxury they cannot afford” (Drake 1996, 65). Clark argues that many northern ngos are so preoccupied with finding financial support that they miss the campaigning potential of their

supporters; “they view their citizens as merely donors, neglecting their potential to act as educators (of their children and peers), advocates (for example through local newspapers or societies), voters, consumers (boycotting or favouring certain products), investors (making ethical choices)” (Clark 2001, 27).

sadly we cannot assume that development education will always lead people to action; “even if participants have high levels of knowledge about the problem and the community has invested in changing their attitudes through advertising or educational campaigns, behaviour is often unaltered” (MCkenzIe-MoHr 2000). It must be recognised that there will be a spectrum of outcomes; for some it will result in life-long campaigning, others may care but give priority to other issues, interests or responsibilities, while in some cases strong opposing beliefs may remain unaffected and may make behaviour change extremely unlikely.

reflecting today’s “sound-bite culture”,4 issues are

24 A Just Life or just life? – James TREWBY: Campaigning and Development Education

sometimes over-simplified as development narratives and lead to simplistic and often ineffective campaigning solutions. Claire sHorT, then uk Minister for International Development, claimed that “single issue campaigning can lead to a kind of irresponsibility – organisations say ridiculous things to raise their profile and money” (quoted in HarPer 2001, 251). Issues chosen for campaigns are necessarily those which attract campaigners’ attention; “in invoking the public interest, ngos will have to respond directly to the concern of a broad base within society” (newell 2001, 1999). Issues that attract interest, such as those involving children, receive attention, while other less popular ones, such as land reform, can be sidelined. The large number of different ‘causes’ could also be a problem, potentially leading to “feelings of helplessness and pessimism” or numbness (osler 1994, ix), especially as concern for some threatening issues like terrorism may block out other urgent issues like climate change. still it is preferable that campaigning and development education happen separately around different issues; this allows individuals to focus on particular areas and avoid the danger of presenting a ‘theory of everything’ or presenting an unchallengeable ‘truth.’

another criticism which can be made of campaigning and development education is that they may disempower the poor; it is not always easy to see how campaigners in britain “link their own voice as advocates with the knowledge and voices of local people on whose behalf they sometimes claim to speak” (gaVenTa 2001, 283). This is a particular problem when the question of inequality is raised; there is no doubt that “northern campaigns have significantly greater access to funding, equipment, technical skills, global policymakers, and international meetings, realities which mirror the historic inequalities between north and south” (CollIns et al 2001, 143). It is also necessary to acknowledge the failings and responsibilities of developing countries themselves; the responsibility does not lie entirely in developed countries.

Finally it is important to challenge the extent of the impact of campaigning in the uk. It is important that other countries join the campaign and demonstrate an emerging democratic call for change across national borders; “it is no good just mobilising ourselves. we need to mobilise the world. what 1% of the world does will be lost if 20% (China in terms of population) or 25% (the us, in terms of gnP) is doing the opposite” (CooPer 2006, 21).

Conclusion

This article has made the case for campaigning and development education, before considering various challenges they face. The challenges are important; they must be listened to and learnt from. However, we might conclude that they should not prevent people from attempting to bring positive change; campaigners must keep on campaigning, while development education should be utilised to enhance the possibility of more people choosing to take action. It is not easy, but is worth the attempt; individuals must recognise that they have an impact on the world and that “to change things is difficult but possible.”1

(endnotes)

1 FreIre P, Pedagogy of Freedom: Ethics, Democracy and Civic Courage. lanham: rowman and littlefield. 1997. Xxix, 74.

2 “underdevelopment, which cannot be understood apart from the relationship of dependency, represents a limit-situation characteristic of societies of the Third world” FreIre Paulo (Translated by Myra bergman ramos), Pedagogy of the Oppressed. london: sheed and ward. 1972. 75.

3 FreIre Paulo (Translated by Myra bergman ramos), Pedagogy of the Oppressed london: sheed and ward. 1972. 15, 60, 66.

4 DoCwra richard, Why is it so hard to change people’s behaviour? 2006. available online from www.changestar.co.uk

5 eDwarDs M and gaVenTa J (editors), Global Citizen Action. Colorado: lynne rienner Publications. 2001. 17-28, 275.

6 Hilder, Paul with Coulier-grice, Julie and lalor, kate (2007). Contentious Citizens: Civil society’s role in Campaigning for social Change. The young Foundation and Carnegie uk Trust.

7 CHaMbers robert, Ideas for Development london: earthscan. 2005. 203-204.

8 Moser s, DIllIng l (editors), Creating a climate for change: Communicating climate change and Facilitating Social Change. Cambridge: Cambridge university Press. 2007. 14.

9 FreIre, Paulo and shor, Ira (1987). a Pedagogy for liberation: Dialogues on Transforming education london: Macmillan education. 37.

25

It is also necessary to acknowledge the failings and responsibilities of developing countries themselves; the responsibility does not lie entirely in developed countries.

Professor John HICK is a Fellow of the Institute for Advanced Research in Arts and Social Sciences at the University of Birmingham, and a Vice-President of the British Society for the Philosophy of Religion and of the World Congress of Faiths. For more on the Global Ethic see: http://www. johnhick.org.uk/article17. html

The Global Ethic

Prof. John HICK

Prof. John HICK

The idea of a global ethic is variously understood, but for me it means basic moral principles that are common to all the main religions and cultures of the world. Is there such a global ethic?

I only have space here to refer to one aspect. All the long-lived cultures have so far been religiously based. Within the world religions there is the universality of the Golden Rule, in either its positive or its negative form.

We find this in the Hindu Mahabharata, ‘One should never do that to another which one would regard as injurious if done to one’s self’; in the Jain Kritanga Sutra, where we are told that one should go about ‘treating all creatures as one would oneself be treated’; in the Buddhist Sutta Nipata, ‘As a mother cares for her son, all her days, so towards all living things a man’s mind should be all-embracing’; a Zoroastrian scripture declares, ‘That nature only is good when it shall not do to another whatever is not good for its own self’; Confucius taught, ‘Do not do to others what you would not like yourself’; Jesus taught ‘As ye would that men should do to you, do ye likewise to them’; the Jewish Talmud says, ‘What is hateful to yourself do not do to your fellow man’; and Muhammad taught, ‘No man is a true believer unless he desires for his brother that which he desired for himself’.

MOZAIK 22 26

The Agape Document (2005) and the Development of an Ecumenical Doctrine of Economy

Nagypál Szabolcs

“I was hungry and you fed me.”

(Matthew 25,35)

“He gave the poor a fair trial, and all went well with them. This is what it means to know the lord.”

(Jeremiah 22,16)

The 2005 background document of the Justice, Peace and the Integrity of Creation (JPIC) working group of the World Council of Churches (WCC), entitled Alternative Globalization Addressing People and Earth (Agape), as well as A Call to Love and Action, based on the previous text and accepted in the Porto Alegre assembly in 2006, are both part of the rich tradition of economic teaching in the ecumenical movement. Here we will try and survey the development of this teaching tradition.

I. Peace, Work and International Cooperation (1895–1937)

The establishment of the World Student Christian Federation (WSCF) in 1895 in Vadstena, Sweden was a founding event in the ecumenical movement. In the economic field the attention of the first period was directed primarily towards peace and international cooperation.

A good example of this is the World Alliance for Promoting International Friendship through the Churches (WA), which was active between 1914 and 1946. It aimed to apply Christian moral and ethical principles to international relations and politics, as well as to promote mutual understanding and dialogue between states and nations.

In the peace conferences organised by the WA, they called for moral and mental disarmament, the use of arbitration and mediation to solve conflicts, and at the same time to strengthen and develop international law and legal solutions.

Almost at the same time the Roman Catholic Church started to pay attention to similar questions: the two pioneering and exemplary Roman Catholic texts of this era are Rerum Novarum (RN, 1891) and Quadragesimo Anno (QA, 1931).

Economic questions and our responsibility towards them were not, of course, brought into the fore in the context the WCC movements of Faith and Order, or Mission and Evangelisation, but rather in the Life and Work movement.

Already the founding conference of the Life and Work movement in Stockholm in 1925 dealt with the ecumenical significance of unemployment, property, work and labour. It was, however, Joseph Houldsworth OLdHAM (1874–1969), the first general secretary of the International Missionary Council (IMC, established in 1921), who first wrote at length on these topics.