CONSERVE

Message from the President

In this issue of Conserve, we highlight the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy’s work to protect and restore native species and their habitats in Western Pennsylvania. Our native species provide essential ecological benefits that support wildlife, biodiversity and rare ecosystems across the region.

The Conservancy’s preserves offer wonderful places to see our region’s native species. For example, at Wolf Creek Narrows Natural Area in Butler County, spring ephemerals offer stunning wildflower displays in the shaded, moist woodlands. The species that thrive there include the two most common native trillium species, large-flowered trillium and red trillium. At another preserve, Dutch Hill Forest, along the banks of the Clarion River, visitors can see a native forest of oaks, sassafras and black gum, and white pine and eastern hemlock.

In our restoration work on Conservancy-owned preserves, along streambanks of creeks and streams, and in our urban forestry work, we use native shrubs and trees, such as eastern redbud. Planting and stewarding native trees and other plants is important in the face of habitat loss, climate change and threats from invasive species. We work in partnership with state and federal agencies and conservation partners, conducting surveys and assessments of native species and collaborating with partners on their protection and regulation.

In this issue, you’ll learn more about how native species and their habitats inform our watershed, community greening, land stewardship and protection, and conservation science work.

You will also learn about some of the partners, from conservation agencies to neighborhood groups to businesses, that help advance our work in urban and rural areas across Western Pennsylvania, and how our programs help make a difference in people’s lives and in communities across our region.

Thank you for your support of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy. It means so much to our staff, and for the conservation work we do. Thank you for continuing to make our work possible.

Thomas D. Saunders PRESIDENT AND CEO

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

PRESIDENT AND CEO

Thomas D. Saunders OFFICERS

Debra H. Dermody Chair

Geoffrey P. Dunn Vice Chair

Thomas Kavanaugh Treasurer

Bala Kumar Secretary

Alfred Barbour

David Barensfeld

Franklin Blackstone, Jr.*

Barbara H. Bott

E. Michael Boyle

Cynthia Carrow

Marie Cosgrove-Davies

Beverlynn Elliott

Donna J. Fisher

Susan Fitzsimmons

Paula A. Foradora

Dan B. Frankel

Dennis Fredericks

Felix G. Fukui

Caryle R. Glosser

Carolyn Hendricks

Thomas F. Hoffman

Gregory M. Hyziewicz

Sanjeeb Manandhar

Justin McCann

Robert T. McDowell

Daniel S. Nydick

Stephen G. Robinson

Samuel H. Smith

Alexander C. Speyer III

K. William Stout

Megan Turnbull

Joshua C. Whetzel III

Gina Winstead

*Director Emeritus

The Western Pennsylvania Conservancy protects and restores exceptional places to provide our region with clean waters and healthy forests, wildlife and natural areas for the benefit of present and future generations. To date, the Conservancy has permanently protected more than 290,000 acres of natural lands. The Conservancy also creates green spaces and gardens, contributing to the vitality of our cities and towns, and preserves Fallingwater, a symbol of people living in harmony with nature.

NATIVE SPECIES: Critical to Pennsylvania’s Natural Heritage and Environment

Home to an abundance of scenic rivers, mountain streams, wetlands, farmland and forestland, Western Pennsylvania has a beautiful and diverse landscape. Equally picturesque and distinct are the native plants and animals, and their habitats, that make our region ecologically important and unique. They are among the many reasons why we work to protect and restore this special region.

Organisms that have evolved over a long period of time in a specific place, native species are adapted to the local ecosystem (e.g.: climate, soils, as well as other plant and animal species that are fundamentally linked). Our region is home to thousands of native plant and animal species that have evolved over thousands of years and flourish in Western Pennsylvania’s land, wetland and aquatic ecosystems.

Native species play a crucial role in maintaining and supporting the complex interactions of naturally occurring healthy ecosystems by providing food and habitat, contributing to cleaner air and water, and helping maintain the biodiversity that makes Pennsylvania unique.

Native wildlife species, such as pollinators, birds and other organisms, have evolved over time along with native plants, and sometimes feed exclusively on their host plants with which they co-evolved.

“There are many examples of these complex relationships in nature,” says Ephraim Zimmerman, Western Pennsylvania Conservancy’s senior director of conservation science for the natural heritage program. “Most of us are familiar with the monarch butterfly, whose caterpillars feed exclusively on milkweed species.”

Other examples include our freshwater mussels, a major focus of our natural heritage and watershed conservation staff. Found in our region’s streams and rivers, native freshwater mussels are sedentary filter-feeders that have evolved “lures” to mimic specific types of fish and salamanders so that their larvae can “catch a ride” as they attach to fishes’ gills and move greater distances. The nature-based services provided by plants and animals are called “ecosystem services,” such as how plants convert carbon-dioxide to oxygen. Plants remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store the carbon in their trunks, branches and roots.

Home to Fallingwater, Bear Run Nature Reserve and Ohiopyle State Park, among other significant recreational interests, the Laurel Highlands owes its name to the mountain laurel, whose bright white and pink blossoms cover the mountainsides beneath the canopy of oaks and hickories each spring. The Laurel Highlands wouldn’t be the same without this native plant!

Protecting Land, Habitat for Native Species

Ephraim adds that protecting land that supports the habitats of native species safeguards important natural areas, ecosystem services and interdependence, all invaluable for conservation and recreation.

“Across the Conservancy, when we conserve and restore land and headwater streams, assess rare species and conduct aquatic habitat surveys, we are prioritizing our native species and protecting and managing their habitats so that they can sustain or thrive in the face of climate change and biodiversity uncertainty,” says Ephraim.

Supporting Native Trees and Perennials

The dense, extensive root systems of native floodplain trees such as American elm, silver maple and American sycamore, and shrubs, such as ninebark, silky dogwood and many native species of willow, filter pollutants before they enter waterways. They also help to stabilize eroding streambanks, thus making effective native vegetation buffers with these and other native trees and shrubs along the edges of rivers, streams, creeks and wetlands. These native plants also provide other benefits, such as a habitat for native wildlife and insects that are essential food sources for songbirds.

Many native plants, such as common milkweed, eastern redbud and white oak, which are regularly planted in our community flower gardens, are perfectly

Left: This emergent wetland bordering the Pymatuning Reservoir in Crawford County is filled with native species, such as pickerelweed, arrow-arum and wapato.

Below: This Ohio River floodplain meadow is composed of a dense herbaceous layer of tall, native, soft-stemmed flowering plants, grasses and sedges.

adapted to Pennsylvania’s environment and support a greater number of native invertebrate species than non-natives. For example, white oak is known to support more than 500 native species of butterflies and moths, whereas the nonnative invasive tree-of-heaven is known to support only two. It’s not just native trees and shrubs, but also flowering plants, and others like grasses and sedges. Native species often require less water, fertilizer and maintenance than non-native plants.

Helping Native Species: What You Can Do

Ephraim shares that you don’t have to be a conservation professional to help native species thrive, but learning more about native species in the region is a great way to start.

“A good first step is learning how to identify native plant and wildlife species, which will foster a sense of place and love for the region by learning about the natural world,” he adds. “Penn State Extension’s master gardener, watershed steward or naturalist programs are excellent in this regard.”

Homeowners can use native plant species instead of non-native species in backyards and gardens. While not all non-natives are invasive, native plants will support a greater number of native wildlife species.

“There are many native alternatives to some of the more aggressive non-native invasive plant species that can be found at

garden centers and greenhouses,” Ephraim explains. “So, look for native alternatives to common non-native garden plants for your landscaping. Be sure to ask for native plants by their Latin name, too.”

He recommends, for example, considering native low sedges such as Pennsylvania sedge (Carex pensylvanica) or plantain-leaf sedge (Carex plantaginea), in place of nonnative daylilies, lily of the valley or grasses, which can be invasive. Another example is blazing star (Liatris), with its pinkishpurple flowers, which is a wonderful native alternative to purple loosestrife, a non-native species that invades wetlands.

There are also many opportunities to get involved to help native species by volunteering with the Conservancy to plant trees, riparian buffers and pollinator-friendly perennials, and to help rid Conservancy-owned nature preserves of invasive, unwanted species.

“While I’m encouraged by the work the Conservancy and other conservationminded people and organizations are doing in creating a healthier Pennsylvania for native species,” adds Ephraim, “we all still have work to do for the long-term ecological benefit of current and future generations of humans and native wildlife.”

To learn more about native species and get a list of information and resources on how you can help native species thrive in Pennsylvania, visit WaterLandLife.org/HelpNativeSpecies.

Beaucoup Bees

WPC member’s

Pgarden hums with happy pollinators

rior to 2022, Tom Hoffman’s front yard resembled most lawns in the attractive suburban community in Pittsburgh’s South Hills: well-manicured grass, dotted by shrubs, shaded by stately oak and maple trees where chipmunks played and robins tweeted good morning.

Yet Tom thought the space lacked something. Missing was the low hum of bees and the delicate flutter of butterfly wings. No colorful blooms existed on which insects could alight to sip nectar and return aloft frosted in pollen.

A Western Pennsylvania Conservancy member and current board member, Tom had read articles in Conserve, e-newsletters and on WaterLandLife.org about native plants’ important role in the ecosystem and how they support native wildlife and pollinating insects. His “great green desert,” as he called it, needed new life.

interesting-looking the garden has become as it's in the fourth growing season,” Tom says. “Strangers stop to look. Several regular walkers have said my front yard pollinator garden is one of the most interesting they've ever seen.”

And the butterflies, birds and bees? “I've seen lots more birds,” Tom confirms. “Finches of all kinds, sparrows, cardinals.” He notes that the maturing flowering shrubs and evergreens provide insect food, shelter and nesting places.

AFTER BEFORE

After giving careful thought to design, soil composition and which plants would survive not only southwestern Pennsylvania’s hot summers and cold winters, but the hungry deer that relentlessly prowl yards nibbling plants to nubs, he ripped up 1,500 square feet of sod and began to install native plants.

A self-proclaimed rookie both then and now, Tom says, “Anyone can do this.” But advance planning, research and extra attention while plants get established are key. He says things such as a WPC webinar titled “Pollinator Habitat: Plant It and They Will Come” inspired him to stay committed.

Fast forward to 2025.

“People are amazed at how full and

“I've got beaucoup bees, attracted by bee balm, coneflowers and more,” he continues. “The bee balm actually 'hum' with all the bees.” Agastache, yarrow, daisies and zinnia attract four or five species of Pennsylvania butterflies. Because he designed the garden so something is in bloom from spring through fall, “a lot of the pollinators are like permanent residents.” To provide shelter for insects, seeds for birds and wildlife and visual interest for the hearty walkers, Tom leaves the plants through winter, cutting them back only in spring.

Even the chipmunks gained playground space…and protective cover. “I think the hiding places in the garden keep them from being picked off by red-tailed hawks,” he says.

It comes as no surprise to any Western Pennsylvania gardener that deer remain a constant challenge. “I've only used plants thought to be deer resistant, although, if hungry enough, deer will eat the chrome off your trailer hitch,” Tom says wryly.

“That's the challenge of a front yard pollinator garden...you can't really fence it off.”

On behalf of the garden’s many admirers—from the two-legged to the six-legged—we’re happy that’s the case.

WPC Member and Board Member Tom Hoffman’s yard in 2022 and three years after planting native perennial beds.

Bee balm hosts clear-winged hummingbird moths. “They remind me of small flying lobsters,” says Tom. A variety of birds, bees, butterflies and other pollinators visit the many native flower species in Tom’s garden.

Near the native Kentucky coffeetrees and swamp white oaks in Renziehausen Park, City of McKeesport residents enjoy picnics and afternoon strolls. In nearby downtown, yellowwoods, black tupelos and flowering cherries line the streets, soaking up excess stormwater, providing greenery and supporting birds and small wildlife with habitat.

RIGHT PLACE RIGHT TREE

as a “slender silhouette” American sweetgum or a “frans fontaine” European hornbeam makes sense. Oak trees often do well in parks, where roots have space to spread.

Those species represent just some of the 41,000 trees planted through the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy’s community forestry program since 2008 in 82 City of Pittsburgh neighborhoods; in business districts, parks and public spaces in 59 municipalities across Allegheny County; and in towns including Erie, Ford City, Ligonier, New Kensington, Jeannette, McKeesport, Monessen and Johnstown. The program includes community greening, the Pittsburgh Redbud Project and TreeVitalize Pittsburgh, of which WPC is managing partner.

“Where possible, we plant native trees,” says WPC Urban Forestry Manager Brian

Crooks, who is a certified arborist with the International Society of Arboriculture and holds a tree risk assessment qualification.

However, not all species thrive in every location; in some instances, noninvasive non-native trees such as gingkoes and London planetrees better tolerate harsh or space-challenged urban conditions. In no circumstances does the Conservancy plant invasive trees.

When choosing trees to plant for certain conditions, the Conservancy’s urban and community forestry team must consider several factors.

“We have a saying: ‘Right tree, right place,’” Brian says. “We thoroughly assess every spot and consider the environs.” For example, intersections require visibility, so a more columnar tree such

By choosing the highest quality plants, engaging community volunteers and building relationships with municipalities, WPC works to ensure each tree’s longterm health.

Other things to consider include, but are not limited to:

• Are there overhead lines?

• Where are underground lines, such as gas lines?

• Will trees be planted on a high-traffic street that gets a lot of salt in winter?

• What type of planting site preparation is needed?

• What tree species are already there?

When it comes to street trees, size matters. The City of Pittsburgh mandates a twoinch trunk diameter minimum. “Smaller trees are vandalized more easily, or are not easily seen by drivers parking cars and delivery trucks,” Brian explains. “They

succumb more quickly to winter salting and dog urine. Bigger trees are less likely to be damaged.”

Residents often express dismay when trees get cut away from power lines. However, Brian notes, “We only plant utility-compatible trees under electric lines, such as redbud, flowering cherry and crabapple. The trees we plant will not grow tall enough to be topped by the power company.” In 2019, foresters from WPC, Pittsburgh City Forestry, Tree Pittsburgh and Penn State Extension met with Duquesne Light’s utility arborists to update lists of utilitycompatible tree species.

“As we plant more and more compatible species, the frequency of tree topping for line clearance will decline over time,” Brian says.

Sidewalk damage is another consideration. “Trees can lift sidewalks, especially certain species and if infrastructure is not built in a tree-friendly way,” he says. “But we can choose trees with less aggressive root systems. The trees we now plant tend to have slower-growing roots, such as native hophornbeam and non-fruiting

Eastern redbuds support pollinators, especially in early spring before many other flowers bloom. And solitary leaf cutter bees often use pieces of the leaves for nests.

ginkgoes.” Although non-native, ginkgoes are pollution- and salt-tolerant, and make great shade trees for city streets thanks to their large leaves.

Aesthetics matter, too. Who doesn’t love pretty trees, especially those that pop with color on the heels of a dreary Western Pennsylvania winter? In 2026, the Pittsburgh Redbud Project will celebrate 10 years of “pinking” Pittsburgh. During mid-April each year, more than 1,531 native eastern redbud trees planted in downtown Pittsburgh and along the riverfronts burst forth with pink blossoms.

“Redbuds are good, small flowering trees,” Brian notes. They do best when planted in yards, pollinator gardens, the wide planting strip between a sidewalk and a street, or where vertical growing space is reduced, such as beneath overhead wires. “They’re not always compatible for streetscape infrastructure

Above: Kentucky coffeetrees planted in 2019 at Railroad Park in Verona have matured and are providing shade.

At left, top: TreeVitalize chose to plant utility-compatible red jewel crabapple trees beneath power lines on this Johnstown street.

At left, bottom: These enthusiastic volunteers helped plant this maple tree and other trees in downtown McKeesport.

because they grow pretty wide,” and they don’t tolerate excess salt. In nature, redbuds typically grow in more alkaline soils. Urban soils tend to be alkaline, thanks to lots of residual limestone from past industry, so redbuds can often tolerate urban settings.

Still, Brian cautions against creating a tree monoculture in urban settings. A mix of trees is best. The Conservancy, partners and volunteers have planted 3,770 trees, 1,804 shrubs and 9,442 perennials and grasses through the Pittsburgh Redbud Project. In addition to redbuds, complementary trees include cherry, birch, white pine, hophornbeam and hawthorn.

“Too much of one species can lead to pests and disease,” Brian explains, noting that TreeVitalize plants very few dogwoods, pin oaks and red maples, because the public plants so many of them. “Tree diversity is the single best resistance.”

Fallingwater’s “Living Collection”

Stroll Fallingwater’s grounds during each season and note the evolving palette of a native Pennsylvania forest. In spring, flowering dogwoods burst forth with white blossoms. As summer begins, clusters of pink mountain laurel blooms dot the understory. In autumn, winged sumac leaves turn fiery red. And against a wintery landscape, eastern hemlock trees provide evergreen interest.

Staff and volunteers balance managing this native forest’s ecology and biodiversity with maintaining native and nonnative plants. Fallingwater Horticulturist Emily Sachs says, “Visitors might notice patches of non-native plants that depict the site’s historical accuracy and help to tell Fallingwater’s story.”

Part of the magical Fallingwater experience comes from

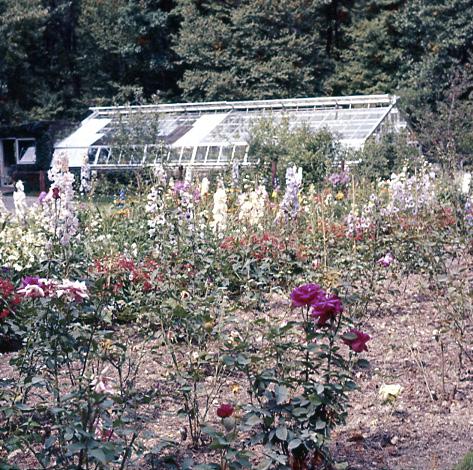

A portion of the cutting garden today. Inset: The cutting garden at Fallingwater, ca. 1950s, Fallingwater Archive, 2014.035, the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

visitors’ ability to explore the site as the Kaufmanns did and experience the art and furnishings, known as the Fallingwater Collection. The plants, trees and flowers that grow near and inside the house, called the Living Collection, accentuate that sensory-filled experience.

Although consisting primarily of native species, the collection includes invasive and non-native species introduced by the Kaufmanns or the area’s earlier residents. “The Kaufmanns cared about the site and the plants,” Emily explains. “They also

At the Guest House and Pool, Japanese wisteria is kept historically accurate to the Kaufmanns’ planting preferences. “We would not choose to plant wisteria now, but we manage it as carefully as we can,” says Fallingwater Horticulturist Emily Sachs.

came to Fallingwater for enjoyment, and wanted interesting, eclectic, beautiful things around them.”

As visitors move from the Visitor Center to the house, “They’ll see more plants that the Kaufmanns chose to plant or that predated them,” she says. Near the Gardener’s Cottage, some non-native ornamental plants, such as Chinese chestnut trees in the orchard, remain part of the site’s historic structure.

Site designs now focus on planting and maintaining native species, she says. The cutting garden is an exception.

“The gardener planted many things with the Kaufmanns, including plants for Liliane to use in floral design,” Emily notes. To lend to historic accuracy and to provide bouquets for the site, the garden features native and noninvasive, nonnative plants such as cosmos and zinnias.

Landscape maintenance includes protecting the site’s native plants by controlling aggressive invasive species such as burning bush, Japanese barberry, stiltgrass and more on the grounds, along pathways and at the forest’s edges.

Kyle Catanzarite, a 20-year Fallingwater volunteer, removes invasive plants with staff and other volunteers, in addition to other duties.

Landscape volunteering “is like attending a class where nature provides instruction on how native proliferation and invasive aggression impact the health and survival of the landscape,” she says.

Balancing Fallingwater’s story with horticulturists’ current knowledge of non-native and invasive plants can be tricky. However, native species are the focus moving forward at Fallingwater, Bear Run Nature Reserve and other Western Pennsylvania Conservancy-owned preserves.

“Mindsets have changed from when this was a camp and then a vacation house to its present-day status as a museum,” says Emily. “Today, we focus on ecological planting practices and the value and importance of native species.”

Year-Round

Our community gardens are creating a buzz! Although installing perennial beds in community gardens was a goal of the Conservancy for years, budgetary restraints delayed the project. After community members requested native plants to support the gardens’ winged residents, generous funders stepped up, enabling us to install native perennial plants in 26 gardens.

Tom Chandley, our volunteer garden steward in Erie, requested milkweed to attract monarch butterflies. Volunteers from the Franklin Garden Club asked for more flower species in the WPC garden they tend at the Franklin Volunteer Fire Company. Students at Pittsburgh Public Schools’ Concord Elementary wanted to learn about native plants and pollinating insects, and Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (PA DCNR) wanted more native plants in its state parks, including Point State Park in downtown Pittsburgh.

Recent funding from KeyBank and TCEnergy, as well as a Community Conservation Partnerships Program (C2P2) grant from PA DCNR enabled the Conservancy to grant such wishes and more. Beginning in 2024 and ending this fall, we will have installed perennial beds in another 26 of our community flower gardens

Then and Now: WPC’s community garden at Route 68 and Hansen Avenue in Butler, Butler County highlights Pennsylvania American Water’s commitment to supporting our community garden work. The company has continuously sponsored this and other gardens since 2000, and currently sponsors 12 gardens across the region.

In this photo of our garden at the Point in downtown Pittsburgh, Fifth Avenue Place and other structures appear to nest in native sedum and coreopsis.

Above:

across Allegheny, Butler, Clarion, Crawford, Erie, Fayette, Indiana, Mercer and Venango counties. A few of our community gardens, such as the 22/30/60 interchange on Pittsburgh’s Parkway West, have been fully perennial for several years.

“We really wanted more native perennial plants in more gardens,” says Marah Fielden, WPC director of community greening projects, “and so did the bees, butterflies, birds and other wildlife.” Perennial plants grow back each year; annuals live just one planting season. Native plants and native insects have co-evolved over long periods, with the plants offering specific nutrients and habitat to which the insects have adapted.

“When gardening with only annuals, you miss three seasons to provide color, as well as habitat for pollinators and wildlife,” Marah says. “Perennials add seasonal, year-round interest.” During winter, stems of native plants can host beneficial insects, and spent seedheads create interest. Marah notes that the Conservancy would like to have a perennial component at every garden. However, installing perennials incurs extra expense and maintenance, so funding and volunteer commitment must be considered.

Annuals, though, “will always be a piece of the program,” Marah says, noting that even the Conservancy’s predominantly perennial gardens feature annuals, including rain gardens in Pittsburgh’s Hill District and Larimer communities. “Annuals make a space dynamic. And they allow volunteers to get involved in the community, to come out every spring to plant and get their hands in the dirt.”

Another component of our community greening program, the downtown hanging baskets and street planters, feature seasonal annuals. People sometimes ask, "Why not plant native perennials in those?" The goal of the street planter program, sponsored by Colcom Foundation since 2008, and the hanging basket program, sponsored by the Laurel Foundation since 2005, is to provide seasonal color and beauty to downtown Pittsburgh where other greening options are not achievable. Annuals provide beauty while being able to survive the harsh urban environment. Although also beautiful, most native perennials would not survive in the baskets and planters, making temporary installation cost prohibitive.

When conditions, finances and time allow, investing in native perennials pays off. Tom Chandley, the volunteer garden steward in our Erie garden, agrees that installing perennials keeps the maintenance low and weeding to a minimum.

“With perennials, you get a nice variety and you can stage them to get at least a three-season bloom,” Tom notes, adding that even during winter, plants host insects and provide roosting places for birds, and dried seed heads feed the wildlife. Plus, and perhaps most important, “Perennials are great for the pollinators!”

Want to help our gardens thrive? Become a garden steward! Please contact Shawn Terrell at sterrell@paconserve.org or 412-586-2327 to learn more.

Clockwise from left: A whimsical gazebo provides an interesting backdrop for blackeyed Susan, coneflower and bee balm in our garden at the Birmingham Bridge on Pittsburgh’s South Side.

Dippy the Dinosaur admires the salvia, iris and peony in bloom at our garden on Forbes Avenue at the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh’s Oakland neighborhood.

Cheerful blanket flower highlights a memorial garden and hosts pollinators at Laurel Valley Elementary in New Florence, Westmoreland County.

During winter, a variety of shrubs and flowers provide aesthetic interest, seeds for wildlife and nesting places for insects.

Columbine and coreopsis line a new perennial sidewalk garden, a complement to an existing perennial garden, in our garden in Franklin, Venango County.

Funding, Partnerships Vital to Invasive Species Management

It’s no surprise to nature lovers and conservation-minded people like you: Our native species and their habitats are under attack by invasive species.

Invasive plants are species of plants that cause harm when growing in environments and regions where they are not native. Once introduced, either intentionally or accidentally, they spread aggressively and outcompete native vegetation.

Unfortunately, many well-known and long-established invasive plants such as bush honeysuckle, Japanese knotweed, multiflora rose, garlic mustard, mugwort and tree-of-heaven have taken hold in Pennsylvania’s forests, streambanks, natural areas and roadside habitats.

Because invasive plants lack natural enemies in their invaded environment, they often form dense monocultures that crowd out native species, preventing them from flourishing or even killing them. This results in reduced biodiversity and provides

little to no value to local wildlife, including native birds, bees and other pollinators. Of the 3,586 species of plants currently found (outside of cultivation) in Pennsylvania, 1,444 are introduced non-native species. The PA iMapInvasives Program tracks 324 of those introduced plants as invasive or potentially invasive species across the state.

“We know the problem of invasive species is widespread, so now we must continue sharing invasive species data and work proactively to track, manage and raise awareness of the threats these unwanted species pose to our natural ecosystems,” says Amy Jewitt, the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy’s iMapInvasives coordinator for the Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program.

Thanks to grant funding from the Richard King Mellon Foundation, Conservancy and PNHP staff made strides towards reducing invasive species threats locally and statewide. These efforts, which started in 2023, were

a plant ecologist at WPC and PNHP, collects data on invasive species in a rare serpentine grassland ecosystem in Chester County.

made possible through key partnerships with conservation organizations such as NatureServe, the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, the Pennsylvania Game Commission and several local land trusts in the state.

Through monitoring and field assessments, staff focused on 10 sites within natural heritage areas, which are ecologically significant areas that host rare species and special habitats such as wetlands or vernal pools, to establish baselines for invasive species monitoring, management and treatment. One of the 10 sites, the Conservancy’s Plain Grove Fens Natural Area in Lawrence County, hosts a mixture of floodplain and upland forests and other special habitats.

Staff identified areas within the sites that are best suited for early conservation actions and detected places where invasive species could be most effectively managed to reduce and/or prevent them from establishing or spreading.

Brian Daggs, the Conservancy’s invasive plant ecologist with PNHP, led the majority of the field work and analyses, and said that proactive stewardship is an effective investment to prevent invasives from propagating.

“Invasive species can degrade habitats critical for native species, especially for rare and endangered plants. So, if we can keep them from encroaching on certain areas, we can keep the ecological balance of those important areas,” he says.

In addition to the field work, staff developed an invasive species prioritization tool in collaboration with NatureServe and the New York Natural Heritage Program, based on a similar species management tool recently created in New York. The tool informs management decisions for invasive species at these sites and provides a color-coded grid of areas across the state rated according to the level of threat from invasive species to native species.

Invasive species records from the sites were also added to the Pennsylvania iMapInvasives database, both to record new observations obtained from field assessments and for use in the development of the prioritization tool.

Working in partnership with DCNR to help inform statewide conservation planning and development decisions, invasive species presence records from the iMapInvasives database information are now included in the Pennsylvania Conservation Explorer, the planning and environmental review data source for the state.

Brian says although the project officially concluded in summer 2024, work is ongoing to engage landowners, conservation organizations, land trusts and other agencies through information, training and webinars about the importance of new tools and resources for invasive species management.

“Thanks to the Richard King Mellon Foundation funding, and through strategic and community partnerships on many levels,” Brian says, “we were able to advance this important project, which will continue informing statewide conservation planning and management efforts for invasive and native species for years to come.”

“The invasive species data collected from the sites went into the iMapInvasives database and was shared with the sites’ landowners, who were critical partners in this project.”

- Brian Daggs, WPC invasive plant ecologist with PNHP

For more information about this project or to learn how to track invasive species with iMapInvasives, contact Brian at bdaggs@paconserve.org or visit WaterLandLife.org.

This extensive invasive species infestation of bishop’s goutweed (Aegopodium podagraria) at WPC’s Plain Grove Fens Natural Area is now under active management by WPC and PNHP staff.

Claire Ciafre,

A New Plan for MUSSELS in Pennsylvania

Burrowing bivalves with catchy, interesting names such as plain pocketbook, fatmucket, fluted shell and pink heelsplitter, freshwater mussels are the small, yet mighty unsung heroes of Pennsylvania’s aquatic ecosystems.

Found at the bottom of most medium and large rivers and streams, freshwater mussels, known also as nature’s water filters, are a large and diverse group of mollusks that play a significant role in the health of freshwater ecosystems. As mussels breathe and feed, they clean rivers and streams by removing sediments, bacteria and pollutants from the water. Depending upon species, a single adult mussel can filter approximately 10 gallons of water per day. The presence of large numbers of native mussels in a river or stream indicates good water quality and a healthy, functioning waterbody. However, their absence could signal potentially serious environmental issues.

The Ohio River watershed has the highest mussel species diversity of any watershed in Pennsylvania, while French Creek in Erie, Crawford, Mercer and Venango counties provides habitat for numerous rare and endangered species, including six species of federally listed mussels. Long-lived and sedentary, mussels are one of nature’s early warning systems of water quality and conditions, as many cannot survive high levels of pollution.

Even with their ecological importance, says Eric Chapman, senior director of aquatic science at the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy, freshwater mussels are among the most imperiled groups of animals, with their populations rapidly declining in North America.

“This is one of the most important projects I’ve worked on in my career,” says Eric, who has been working at the Conservancy for 19 years. “This work is critical in the protection of this important group of species, ultimately in an effort to prevent their further decline and extinction.”

The surveys and data collection have informed a new, first-ofits-kind statewide strategic management plan for protecting and restoring mussel populations in the Commonwealth. The Pennsylvania Freshwater Mussel Conservation Plan will recommend strategies and actions that conservationists, scientists and resource managers should prioritize and implement to benefit and protect freshwater mussel populations across the Commonwealth.

The plan, which will be completed and released to the public in late fall 2025, will offer proactive management strategies for habitat protection, watershed restoration best practices such as streambank restoration, riparian tree plantings and dam removals, and for pollution and sediment control. It will also identify areas for potential mussel reintroduction.

There are more than 300 native freshwater mussel species in North America, but nearly 70 percent of the continent’s mussel species are considered endangered, threatened or vulnerable due to a number of factors, including industrial pollution, acid mine drainage, dredging, dam construction, invasive species and climate change. Those environmental stressors are also true for Pennsylvania’s 67 mussel species, of which 12 are considered state or federally endangered or threatened.

To address these challenges, Eric, along with other Conservancy aquatic scientists and conservation partners, including the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission, waded in several miles of the state’s rivers and streams over the past four years to conduct comprehensive mussel surveys. These field studies involve detailed mapping, cataloging, tagging and species identification to assess and collect data on mussels by species, habitat conditions, age and abundance.

Eric says this plan is critical for the survival of these little-known, resilient animals.

“This plan is also a critical call to action and roadmap for how we can naturally maintain and improve water quality in Pennsylvania. When we protect and improve habitat for freshwater mussels, other organisms including fish, crayfish and damselflies benefit, too,” Eric adds.

Through this plan, funded by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, he says, the Conservancy and its partners are providing guidance on how to manage our river systems in a way that supports mussel health to minimize ecological imbalance to help this important group of species thrive.

“We also hope this plan helps raise awareness about the role mussels play in our ecosystem—and the threats they face—to build support for these essential conservation efforts and inspire a sense of shared responsibility for stewarding for nature’s smallest aquatic filters,” Eric adds.

The plan, along with detailed maps and other information about mussels’ lifecycle, reproduction and their ecosystem services, will be posted to the Conservancy’s website, WaterLandLife.org, by the end of 2025.

Left: WPC’s Senior Director of Aquatic Science Eric Chapman (right, in tan wader pants) and with other WPC staff and partners, assess mussels in the Chesapeake Bay watershed in York County. Above: The yellow lampmussel (Lampsilis cariosa) is native to Pennsylvania’s rivers and can filter nearly 20 gallons of water each day.

Penn Hills Volunteers Rid Invasives, Add Native Plants Along Plum Creek

There isn’t a native, flowering tree that Kathy Raborn, president of the Penn Hills Shade Tree Commission, doesn’t like. “It’s too hard to say which is my favorite, but a native black gum ranks high on my list!”

For the past eight years, Kathy has led a group of dedicated Penn Hills residents, including six PHSTC board members, with a mission of restoring and beautifying community parks, streets and front yards with native trees, shrubs and perennials in the Allegheny County municipality located 10 miles from downtown Pittsburgh. She founded the commission while working as a landscape designer at Raborn Landscape Design, where she designed numerous outdoor landscapes for schoolyards and private residences.

Members of the Penn Hills Shade Tree Commission enjoy the native perennial buffer of wild bergamot and black-eyed Susan they planted with other volunteers along Plum Creek, which is a tributary to the Allegheny River, in Allegheny County.

Kathy Raborn, seated in the light blue T-shirt, talks with several PHSTC members amid native plants along Plum Creek.

“It was a ‘natural’ fit for me to start the commission, but moreover, there was definitely a need to transform overgrown, ecologically poor and low-tree canopy areas in Penn Hills with native trees and shrubs,” says Kathy. After months of strategic planning and a vote from the Penn Hills Council, the PHSTC was established in 2017. Since then, more than 450 trees have been planted throughout Penn Hills, many with funding and trees through TreeVitalize Pittsburgh, for which the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy is the managing partner.

Over the past six years, Penn Hills has been named a Tree City USA, and over the past five years, it has received the Tree City USA Growth Award. Both national programs of the Arbor Day Foundation recognize communities for their commitment to urban forestry and community engagement efforts with trees.

One of the PHSTC's large-scale initiatives was an invasive plant and streambank restoration project that began in 2018 at the popular Penn Hills Community Park on Plum Creek, a tributary of the Allegheny River that flows through several municipalities, including Penn Hills, Plum, Oakmont and Verona boroughs.

Overgrown with invasive Japanese knotweed that outcompeted native plants, Plum Creek’s streambank had poor, mostly nonnative vegetation, contributing to the creek’s poor water quality due to runoff and sedimentation. Kathy says the PHSTC recognized the need for action and made it a priority to reduce the knotweed, stabilize the soil to prevent erosion, and bring more fish, native pollinators and wildlife back to the park.

“The park attracts walkers, hikers and athletes from around the surrounding communities. Ultimately, we just wanted this to be a beautiful, thriving natural space filled with native plants and trees that the community, bees and butterflies could enjoy,” says Kathy.

After a few less-than-successful attempts to remove invasives plants, the PHSTC applied for a Conservancy Watershed Mini Grant in 2019 through the Conservancy. The grant provided funding for the application of an herbicide that effectively eliminates unwanted plants on land and in aquatic areas without harming the water quality. The grant also paid for 43 trees and shrubs, deer fencing, tree stakes and the application of a native wildflower seed mix.

A year later, the PHSTC applied for another Watershed Mini Grant that helped with additional knotweed management, and funding for 33 more trees and shrubs and wildflower seed. Grants from the Sierra Club also supported the project.

The project, which began as an effort to replant 2,000 feet of streambank and its surrounding habitat to improve the health of the creek, Kathy says, grew into a powerful example of community-led environmental stewardship with more than 160 volunteers who participated over a four-year period.

Today, native tree species such as sycamore, tulip tree, burr oak, hackberry, redbud, pawpaw and American hornbeam, and native

perennial plant species such as wild bergamot and black-eyed Susan all adorn the creek buffer.

Another one of Kathy’s favorite native flowers, swamp milkweed, which is a crucial host plant for monarch butterflies and provides nectar for various other pollinators, is also a predominant native species along the creek.

With the help of volunteers, the PHSTC continues regular stewardship of the riparian buffer by pulling invasive plants such as mugwort and wineberry, and pruning trees. Educational signs have been installed along the creek to help park visitors learn more about the importance of native plants and healthy waterways.

“It's great to see all of the native vegetation and more pollinators, birds and aquatic life as a result of this project,” she shares. “This project also shows how incredible Penn Hills is and what can happen when people come together for a common goal.”

The PHSTC is one of the sponsors of this pollinator-friendly WPC community flower garden, known locally as the Penn Hills Welcome Garden, located on Rodi Road near I-376E.

wild flower power

At Fallen Aspen Farm, which leases land on the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy’s Plain Grove Fens Natural Area in Lawrence County, Jake Kristophel and Desiree Sirois keep bees in addition to raising cows and sheep. The bees help to pollinate their 150-tree pear and apple orchard and other shrubs and trees. Abutting the farm, a six-acre native wildflower meadow planted by WPC in 2019 blooms each spring, summer and fall with native pollinator-supporting flowers including marsh blazing star, boneset and ironweed…flowers that Fallen Aspen’s bees likely visit in addition to wildflowers Jake and Desiree have planted on the farm.

“There are also wild hives in hollow trees that I'm sure benefit from the wildflowers,” Jake says. “Come fall, when the goldenrod blooms, it is quite the show to see the katydids, praying mantis and thousands of other bees, flies and different insects flitting around in the golden light of sunset.”

In addition to the meadow at Plain Grove Fens, wildflower plantings over the last several years support restoration work

at four other Conservancy preserves where there had been agricultural fields or other areas that were regularly mowed: Bear Run Nature Reserve in Fayette County, Helen B. Katz Natural Area in Crawford County, Miller Esker Natural Area in Butler County and Sideling Hill Creek Conservation Area in Bedford County.

“Different species of wildflowers bloom at different times, providing showy displays and food for pollinators for a good portion of the growing season,” explains Tyson Johnston, a WPC land stewardship manager. Although the meadows provide beautiful scenery—Jake even cut a path near the WPC-planted meadow so visitors to the farm can enjoy it up close—they exist primarily to provide biodiversity and habitat for native species.

“Meadows of native wildflowers and grasses provide important habitat for birds, insects and other wildlife. In particular, pollinators are crucial in advancing our food supply, but the habitat they require is diminishing,” Tyson says. “Meadows can also serve to rebuild soils, manage stormwater and store carbon.”

Three-quarters of an acre next to a parking area at our Helen B. Katz Natural Area in Crawford County bloom with native flowers and grasses including black-eyed Susan, butterfly milkweed, New York ironweed and more. Inset: WPC Land Stewardship Assistant Isaiah Brooks used a tractor-mounted seeder to spread the seeds.

Native perennials also build resiliency against climate change and invasive species.

Retired, lower-quality agricultural fields or old lawns are great candidates for conversion to meadows, Tyson explains. “In areas that were largely monocultures, introducing a diverse pollinator species mix helps to promote biodiversity and resilience.” Once the meadow is established—and it can take a couple of years to really take off, he notes—“one can hear the buzzing of insects, watch the flitter of butterflies and birds and just ‘feel’ the life that abounds.”

“Funding for the 2019 planting at Plain Grove was provided through the Conservation Stewardship Program administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which provides funding to private landowners to help address specific conservation needs,” says Andy Zadnik, the Conservancy’s senior director of land stewardship. Plantings at Sideling Hill, Katz and Miller Esker were funded through a generous private donation.

A large planting project at Bear Run Nature Reserve in 2008 (funded through another USDA program) helped staff assess which species thrived and how to replicate transitioning areas on other preserves into native meadows. Species in the mix included butterfly milkweed, two types of aster and little bluestem.

Our land stewardship staff and conservation science staff worked with a local seed producer to establish appropriate seed mixes for site conditions and so as to not introduce non-native species.

A wildflower meadow may be planted as part of a larger restoration effort, such as at Katz Natural Area where we’ve planted native wildflowers and trees, as well as restored wetland conditions across approximately 40 acres.

The Conservancy follows a specific planting process to cover large areas. Over the course of several months, our land stewardship staff:

• mows existing vegetation as low as possible, then rakes off the loose debris.

• applies an herbicide to remove the remaining vegetation. Or, small areas can be covered with a tarp, a technique called solarization. This important step ensures the seed makes adequate contact with bare soil.

• uses a tractor-mounted seeder to plant wildflower seeds and a cover crop, typically oats, in late fall or mid-spring. In one pass, the seeder lightly cuts and fluffs the soil (using disks attached to the seeder), drops the seed and presses the seed into the soil (using a cultipacker, or spiked roller).

“We hope for light rain within a day or two after planting. Then we wait for the next growing season to see some species start to appear!” Tyson says. “It may take two to three years before the meadow ‘peaks.’”

By protecting and conserving these valuable habitats, “We can help safeguard biodiversity, mitigate climate change and maintain the health of our preserves, and planet, for future generations,” Andy says. “The benefits of these plantings can only get better over time.”

Thanks to USDA funding, we transitioned former agricultural fields at Bear Run Nature Reserve into more than 70 acres of native wildflower and grass meadows, including species such as goldenrod, purple coneflower, marsh blazing star and butterfly weed. Some of these meadows are now transitioning to native forest.

Left: Pollinator plantings can be small strips or sections integrated into landscaping, such as this one around the parking lot at our Toms Run Nature Reserve in Allegheny County, which features wild bergamot, black-eyed Susan and more.

Right: A monarch butterfly feeds on ironweed at our Miller Esker Natural Area in Butler County, where a small meadow of wildflowers adjacent to the parking lot features black-eyed Susan, beardtongue and more.

800 Waterfront Drive

Pittsburgh, PA 15222

412-288-2777

info@paconserve.org

WaterLandLife.org

Fallingwater.org

Create a Legacy for FUTURE GENERATIONS

You can create a long-lasting impact in Western Pennsylvania by including the Conservancy in your estate plans. Your legacy will contribute to our financial strength and ability to conserve Western Pennsylvania’s most spectacular land, water and wildlife and to care for Fallingwater, Frank Lloyd Wright’s masterpiece. There are a variety of options, but bequests in a will or trust are one of the most common ways of making a legacy gift, and they are simple to establish!

If you would like more information about planned giving options or if you have already included WPC, or one of its programs such as Fallingwater, in your estate plans, please contact Julie Holmes, senior director of development, at 412-586-2312 or jholmes@paconserve.org