60 minute read

Yoshi Takata Exhibition

Advertisement

In 1916, Aleksander Rodchenko, born in St. Petersburg three years before the coronation of

Nicholas II and artistically .trained in Kazan as the Russian Revolution exploded, presented his work at a Moscow exhibition organized by Vladimir Tatlin.

It was the first time the young artist had appeared prominently in the Russian art scene. While this scene was undergoing a period of violent upheaval (the country was on the verge of launching a culture war against the very “bourgeoisie ” that had redefined art by superseding the tradition-steeped pre-impressionist French salons decades earlier), the reception to the newcomer was still frosty. The foremost artist in Moscow at the time, Kazmir Malevich, mocked Rodchenko ’ s geometrically-inclined work as rigid, derisively labeling it constructivist. Malevich was no stranger to geometry himself, having exhibited his iconic “Black Square ” just two years earlier and founded the Suprematist movement that, presuming we classify Vasily Kandinsky ’ s Der Blaue Reiter group according to its primarily German composition, marked the introduction of abstraction to popular Russian art. However, Malevich found Rodchenko ’ s pieces to be overly industrial; rugged. They were a reflection of the materials, textures, and man-made contraptions that filled everyday life rather than the ideologicallydriven “blank canvas, ” to be filled with pure shape and color, that was envisioned with “Black Square.

The term

“ constructivism ” quickly lost its negative connotations. Indeed, it was the perfect word to describe this radical fin-de-siecle movement that saw empire, society, and centuries of cultural and artistic Constructivism, the art form, rapidly surpassed suprematism, classicism, Peredvizhniki (the Russian form of realism), and everything else to become the predominant artistic style in the newly-formed Soviet Union. Indeed, constructivism became the only state-sanctioned form of artistic expression. The outsiders were now insiders. Rodchenko, dismissed by the art establishment three years earlier, was appointed by Lenin ’ s Bolshevik government as the Director of the Museum Bureau and Purchasing Fund in 1920. This gave him nearuninhibited control over the reorganization and future direction of the USSR’ s entire museum system; the power to fundamentally change the way art was collected and the way collections were presented to the public. As founder of the Fine Arts division of the People ’ s Commissariat for Education, Rodchenko was also able to sculpt the first generation of Soviet-raised artists and, given the vice-like state control over all cultural activities of the time, define their style of production. Just as Russia ’ s society, labor force, education system, and economy had been revolutionized and were being constructed from scratch, so too was its art industry. Block by block, cube by cube, from scratch...using means thought inconceivable just two decades before. Tatlin ’ s symbolic Monument to the Third International may never have been constructed physically, but it was just as tangible, and just as legitimate a representation of society and art as anything else at the time. (seen at right) But while the movement of the 1920’ s was unique to Russia and Eastern Europe, the technologically advanced and seamlessly interconnected society of the new millenium means that the entire world is implicated in this new revolution. First contemplated by Americans, brought to fruition by (allegedly) the Japanese, and then further refined and diversified by a Belarusian, blockchain technology has permanently changed the way we transact and assign value. Furthermore, just as communism a hundred years ago, blockchain threatens to completely overturn long-entrenched systems of state governance and the mechanisms of economic control they perpetrate. The exact future of cryptocurrency is uncertain, and, as many have said, its true impact may not be known for 40 years or more. However, blockchain and the currencies anchored in them have proven to be far more than a fleeting phenomenon. For established players in industries either seemingly in direct opposition to this development, or that simply have not engaged with it on a substantial level, the future is quickly being defined by the choice of “ adapt or become obsolete. ”

For art, just as in the Soviet Union a century ago, it is a time of change and exciting opportunity. There is great potential for increased equality and democratization in the art world…to the benefit of both its consumers and those at its creative core. Ironically, while the USSR provided this potential through the establishment of centralized state control, blockchain technology provides it through a polar opposite mechanism: complete decentralization and the ensuing limits on state control. To analogize, picture a Soviet artist in the 1930’ s; completely subsidized by the state government, she is allowed to make a comfortable living while producing art, yet has little agency over the subject matter of such creations. Now, imagine an artist in the 2030’ s who does not require subsidization from the government, gallerists, or any other “ patrons ” ...she has complete agency over what she creates, an equity stake in many of her works, and, through smart contracts, the right to receive additional royalties any time her work is sold on the open market. Furthermore, consumers with limited liquidity who wish to invest in and support the art industry can attain fractional ownership of their favorite works as easily (and, given some studies, with as much financial security), as they can purchase a stock.

The financial fortunes of the aforementioned 2030’ s artist would be linked to the appreciation value of her works. This facilitates the avoidance of the infamous paradigm in which a creative only achieves public recognition late in life or posthumously…and thus neither her nor her family derives significant financial benefit from her success. Furthermore, the 2030’ s artist has the opportunity to collaborate on joint digital works with contemporaries around the world. Blockchain technology has made all of these scenarios possible; the “ second Constructivist revolution ” is here. Indeed, it is changing three primary sectors of the art industry: provenance verification, commodification and sales, and the creation of art itself. Dealers, galleries, and aspiring artists themselves should take note if they hope to position themselves well economically over the coming decades. Thus far their reception to innovation has been varied; however, they are powerless to stop technology and art’ s growing convergence.

The first sector of the art industry that blockchain made a tangible impact on, and indeed the one in which it has continued to make the most significant inroads, is provenance verification. This field is typically driven by museums, galleries, and auction houses and is crucial to their survival. Art derives value from its provenance, and the art market (whether one considers a museum attempting to attract the general public or a gallery making a multi-million dollar sale) depends on consumer trust in the authenticity of the works being viewed or purchased. Authenticity verification has a high transaction cost both financially and vis-a-vis time, a problem which blockchain can mitigate by creating a permanent decentralized record of ownership and ultimately serving as a public library. Provided that the provenance of artworks is originally inputted correctly, it can also serve as a shield against the human error that allows fraud and counterfeiting to go undetected. Many blockchain companies, some led by established art industry insiders such as Robert Norton, have been marketing these art-specific registry services for years and have already carved out a sizable niche in the market. The sector of the art industry that I believe blockchain could ultimately alter most drastically and fundamentally is sales. Through offering the potential to digitally tokenize physical artwork, cryptocurrency has facilitated fractional art investment. This is revolutionary for a number of reasons. From a collector ’ s standpoint, it a) diversifies and increases investment opportunities in the art market, and b) significantly increases the dynamism and liquidity of that market by facilitating equity purchases that can lead to high returns as pieces appreciate. Art generally outperforms blue-chip stocks; it is one of the world’ s most stable and lucrative fields of investment. Now tokenization has streamlined access to the industry.

From an artist’ s perspective, blockchain ’ s primary effect on sales is that it allows one to maintain equity in their own work and thus continue deriving financial benefit long after a piece is first sold. The ultimate result is the potential for rapid democratization in one of the world’ s most elitist industries. By lowering the financial bar for entrance, blockchain has widened the field of potential collectors, increased the amount of capital available to artists, and generated more interest and fluidity in the market worldwide. Whether it is prospective collectors being given the opportunity to purchase equity in one of their favorite Picassos or emerging artists retaining a stake in their initial works as they gain popularity, blockchain should provide new options and agency for those on both sides of the traditional artist-patron relationship.

Blockchain, and more specifically Ethereum, can also be the artist’ s medium in and of itself.

More than just a means by which art can be shared with the world, blockchain can be the cornerstone of the creative process. "Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, ” and all art (indeed even the answer to the question: “ what is art?”) is subjective. Digital art has increasingly complicated the “ what is art” issue, with the meteoric and polarizing rise of NFT’ s marking the culmination of the paradigm. There are engaging arguments on each side of the NFT art spectrum. Some people (likely those expressing the most vigorous support of the theory that crypto is as a democratizing force) argue that each minted token is inherently a form of digital art. Others (many of whom view NFT’ s as a bubble with no staying power) argue tokens are a parody of art at best…a way to “dilute ” and “tarnish” the industry and its “ real artists ” if viewed as anything but satire. I think that the truth lies somewhere in the middle; we should neither dismiss tokenized art out-of-hand nor take all tokens to be “ art. ”

We should also be careful to separate “blockchain as artist’ s medium ” from the NFT phenomenon and CryptoPunk-style tokens. The latter, in my opinion, long ago transcended their art/graphics roots to form an independent industry existing outside the influence of the art world and determinative of its own trajectory. Now the NFT community is controlled by actors who primarily see the manufacturing of an image as a necessary means to the end of a profitable token. I’ ve set this industry aside for the purposes of my research, which instead has focused on the perspectives of those who primarily see blockchain as a medium for artistic expression. Some such digital artists have seized a unique opportunity to share their message with a widespread and engaged audience not limited by geographic locale and that can provide monetary support with minimal transaction cost. Even more importantly, digital artists have been able to instantaneously connect and collaborate with their contemporaries.

Of the hundreds of popular modern art groups and movements formed in the past century, most have been united at least partially by geographical proximity (as a random selection, the American abstract expressionists, the Danish/Dutch/Belgian surrealists [COBRA], the Italian futurists). Blockchain has eliminated this physical barrier and created new ways to collaborate that extend far beyond simply exhibiting similarlyinspired works. Now, for example, a group of four artists, one from South Africa, one from Kazakhstan, one from France, and one from Brazil, can combine their perspectives to produce a unitary or serial piece within an hour...all without leaving the comfort of their own continents. Even more than so than your typical new artistic medium, collaborative blockchain art has the potential to significantly bolster cross-culture exchange, lead to the germination of new perspectives, and give rise to “ postmodern ” waves of art that challenge a global viewership not necessarily limited by nationality or background.

Curate. Collect. Create. Blockchain can drastically shift how the art world engages with all three words. In these early years of the technology, the pioneers doing so have had varying degrees of success. To structure this piece chronologically, according to the sectors that blockchain has impacted, I’ll begin with the “ curation ” element: considering provenance verification and how it affects the way investors and industry professionals amass art. Modern art from Bangkok, Thailand (above) and Phoenix, USA (below).

What if artists fourteen time zones apart could simulataneously collaborate on a digital work?

A shocking 2014 study completed by the Fine Arts Expert Institute in Geneva, Switzerland found that over half the works circulating in the art market are not authentic. This paradigm has a devastating impact on the worth of individual pieces and the art industry as a whole; without trust in provenance, value is greatly diminished. Small galleries and museums often do not have the financial resources to obtain reliable provenance verification services (a prime example being the Terrus Museum in France, which admitted in 2018 that 82 of its 140 works were fake). Meanwhile, larger galleries and auction houses perpetually expend extensive temporal and financial resources competing with each other and against fraudulent actors to verify the authenticity of their collections. The landscape of this battle changed at approximately the same time as the Geneva Institute released its study. In 2016, exSotheby ’ s salesman Nanne Dekking founded the public digital art registry Artory...essentially a public library of industry-leading provenance data accessible to anyone who desires it.

In a recent interview, Dekking described Artory as a “trusted, neutral resource bringing a new level of confidence to the art market. ” With all data secured in the blockchain, Artory is, according to Dekking. “built with the same security standards as the banking industry. ” It is a trust-inducing mechanism meant to fight fraud, enhance transparency, and hopefully make the market more lucrative as a result. ‘“The art market has not grown in ten years, ” lamented Dekking in a 2020 interview. “Many new buyers find the milieu of the art world alienating...they want to buy with absolute confidence or not buy at all...Most potential buyers want the same reassurance that they expect when they buy other valuable goods--such as a car or house. ” That level of reassurance was previously unattainable in the art market, a paradigm exacerbated by the fact that many new buyers struggle to navigate the highpressure world of houses such as Sotheby ’ s and Christie ’ s. After all, in a previously growth-limiting paradigm, “the art world is based on trust, not on facts. ”

Dekking values both factors. Artory, ironically a disruptor despite the fact that it is reinforcing the security of the feedback loop essential to any artrelated transaction, enhances trust through enhancing the accessibility of facts. It takes the previously private registries of auction houses and museums, inputs them into the blockchain, and then makes this database publicly available to prospective buyers. The system is directly analogous to a municipal or state registry that allows potential real estate investors to see the construction date, valuation, and other relevant details about a property they are considering.

Artory has been met with some opposition from those in its industry. Trust is a currency, and some galleries stand to surrender a significant financial advantage by openly sharing their information and thus leveling the playing field. It’ s a leap, however, that the majority have been willing to take, based in no small part on shrewd financial calculations that see present losses offset by future gains. A large registry saves both buyers and sellers significant cost in researching and verifying the provenance of works. Thus this blockchain data storage system, by most predictions, should increase both the volume of transactions and the amount that purchasers are willing to spend. It will be fascinating to see how fiercely and quickly competition in this blockchain registry sector develops. It will also be worth tracking Artory, the “ zero-to-one ” leader that popularized the concept, to see if the brand can demonstrate the long-term sustainability of their business model or even become the de facto “ registry of record. ” I’ m optimistic about the company ’ s outlook; in building its core digital infrastructure Artory showed foresight and market knowledge through anticipating common collector concerns and addressing them in ways uniquely adapted to the virtual space. Despite the vast amount of information on each artwork publicly available on the blockchain, the piece ’ s owners remain completely anonymous to viewers. Furthermore, art owners are given a digital “ collector ’ s vault” where they can store relevant information inaccessible even to Artory management. It is unclear how long and to what extent such privacy protections can remain in place given an increasingly regulatory environment. However, the policy illustrates that Artory is committed to providing a secure platform for collectors who choose to access its registry while remaining discreet.

Museum of Modern Art, Baku, Azerbaijan

While established art houses and high net worth collectors will doubtless financially benefit from Artory and its peers, the Artory concept is nonetheless a democratizing force with power to radically disrupt the traditionally insular art industry. It deftly rectifies the information asymmetry that proves a massive barrier to new collectors regardless of their liquidity. Purchasing art can be an intimidating process no matter how much one is willing to spend. With information held very closely, ascertaining the true value of the work or the most relevant factors for its appraisal can be challenging even for insiders. A blockchain-based database almost entirely eliminates that problem, creating a system in which there is less fraud and those who can best perform basic due diligence can be rewarded just as much as those with an “ art pedigree. ”

In recent years Artory has enjoyed a number of watershed moments that represent both its potential and staying power. In 2018, Christie ’ s trusted Artory to record its auction of the Ebsworth Collection, the first such major blockchain auction in history. Each purchaser in the >$300 million dollar sale received an encrypted certificate verifying their new work’ s provenance. Several other companies (for example Maecanus, which I’ll touch on momentarily), have since profitably leveraged cryptocurrency and blockchain technology in the auction space.

In 2019, Artory earned a respectable $7.3 million in Series A funding, garnering investments from figures such as David Williams, a stakeholder in other “ zero-to-one ” companies (such as Spotify, Postmates, and the RealReal) that have revolutionized their fields. These funds were used to acquire a staggering 22 million artistic records, a figure made more impressive because they were obtained (through the acquisition of AuctionWorld) from 4,000 different auction houses. Artory is not just being tolerated by the established art world but embraced by it….as a result it is collecting data in wide swaths that could lead to industry dominance. Christie ’ s, Sotheby ’ s, and Winston Art Group (a veritable who ’ s who of art auctions) have all collaborated with Artory to verify and register art that is listed on the platform.

What if, instead of just recording provenance, blockchain was used to tokenize valuable works into fractional shares? That question was originally tackled by Singapore-based Maecenas three years ago…the result is a new investment trend that has steadily gained traction and could ultimately be the art industry ’ s most exciting frontier. “Tokenization of assets is the most prominent and exciting use of blockchain technology, and we ’ re proud to be pioneers in this space...We are looking forward to seeing and leading the financial revolution, ” Maecanas ’ s CEO Marcelo Garcia Casil recently said. Casil and Maecanas made headlines in 2018 when they tokenized a million-dollar painting (Warhol’ s 14 Small Electric Chairs) and quickly sold shares equivalent to an aggregate 31.5% stake. This was the first multi-million dollar art tokenization/sale in history. Maecanas ’ s philosophy, which generally prohibits it from buying any work expected to earn below $500,000, reflects great ambitions for both profit and prestige. “ asset tokens ” that can be sold instantaneously on the open market as easily as any other crypto-based asset or stock. Ethereum-based, Maecanas “ art tokens ” can be purchased with any typical payment method on an exchange open 24-7. The platform makes art investment straightforward in a way never previously seen; it also significantly undercuts typical gallery costs by increasing the efficiency of the sales process and decreasing the number of people involved. Maecanas proudly advertises fees as low as 1% for buyers and 8% for sellers. A former investor confirmed to me that buying premiums typically hover around 4 or 5%; the 1% only applies to those paying with Maecenas ’ s “house ” token. Regardless, this fee is still lower than anything one would expect to see at an auction house or gallery.

Importantly, despite this apparent market advantage, Maecenas has been building its brand not in direct opposition to the current gallery scene but in enthusiastic partnership with it. One major supporter is the London gallery Dadiani Syndicate, a forwardthinking institution which already accepts cryptocurrency for payment. Eleesa Dadiani offered a poignant take on Maecenas ’ s initial auction and its implications, stating “this auction was unchartered territory; a new model in an age-old market. The unprecedented demand, and speed with which the first fraction has been sold, has gone a long way to validating our vision of a more democratic and open art investment market.

Maecenas is transparent about this “disruptor ” vision; its mission statement is

In a 2018 interview explaining the company ’ s origins, Casil said “ we believe that by lowering the threshold of entry we can make art investment available to a much wider audience who can collectively co-own art all around the globe, effectively democratizing fine art. ” Unfortunately, three years after its founding, it seems that Maecenas has yet to find the grassroots following it anticipated. The Warhol piece remains the most famous work Maecanas has auctioned while the company ’ s value has exponentially dropped. The Maecanas crypto, ART, is currently trading at $0.005 (down from a high of $2.58 in January 20!8). At the time this paragraph was written, the previous 24-hour trading volume was just $337.

Maecanas may be struggling but it is not the only player in the industry. Masterworks, Feral Horses, and ArtSquare are three other companies who have entered the market with varying degrees of success. Feral Horses ’ model demonstrates where Maecanas may have failed. Limiting itself to auctioning high-value works by well-known artists and priced in the $1 million range, Maecanas failed to generate volume sales or steady income. In contrast, Feral Horses has sought to democratize the market for both investors and artists. The company works with modern artists who upload their works to the platform and then, provided a minimum threshold of interest is met, sell equity in it. Returns are relatively modest; in one six-week period, for example, the company earned about $150,000 USD through the sale of 17 works. However, Feral Horses seems to have struck a good balance in prioritizing artists who have little name recognition but a reputable history interacting with established institutions. The company has diversified its income (and that of its investors) by renting the physical artworks listed on the platform to hotels and paying out some of the proceeds as dividends. Finally, it has established a solid market niche through a “ artist-first” reputation; when shares in a work are sold artists receive 80% of the proceeds (as opposed to an industry standard of 50%).

Meanwhile, US-based Masterworks, unique in that it is registered with the SEC, buys what it refers to as “blue-chip ” paintings and then sells a certain percentage of shares in them. The Masterworks collection includes such names as Monet, Picasso, and Warhol (with a Monet and Warhol recently selling for $6.23 million and $1.85 million respectively) but the company keeps a lower profile than some of its contemporaries. It is designed as a haven for stable long-term investment (like a more lucrative version of a government bond) rather than a flashy disruptor or a “buy-and-flip ” mechanism for increasing art market liquidity. In a poignant statement given the current financial climate, Masterworks refers to art as a “hedge against inflation. ” Perhaps the ideal foil to Feral Horses, Masterworks downplays the “ art” element of its business: it brands itself as an excellent investment (that just happens to involve art) rather than a means to get involved in the art industry (that just happens to provide returns). If one visits the company ’ s online database/marketplace, projected investment returns over a given amount of time are listed prominently alongside each piece of art. For example, a Picasso drawing currently selling for just under $24,000 is projected to appreciate to $623,000 (a 26x rate of return) in the next 7 years. Meanwhile, a Renoir selling for around $8,000 is expected to appreciate to over $750,000 (a staggering 105x rate of return) in the next 53 years. Masterworks currently holds a larger and more diverse collection than many of its competitors; it seems that its practical marketing strategy is resonating with investors.

Fractional ownership in a Picasso? As good an investment as blue-chip stock?

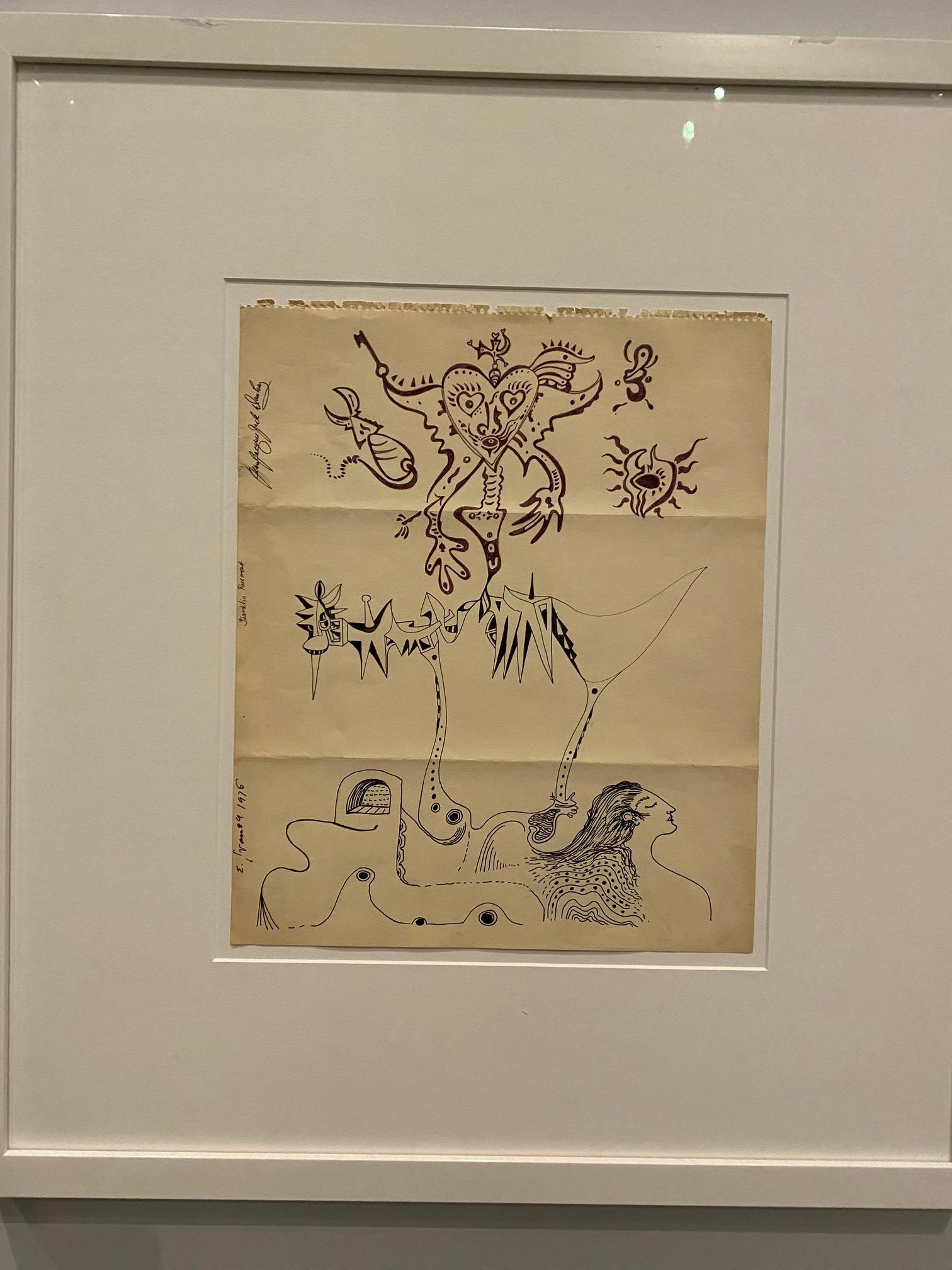

Blockchain ’ s third and final major impact on the art industry thus far involves changing the mediums with which art is created. This movement was originally perpetrated by the aptly-named Dada Collective, whose moniker references an artistic movement that, like constructivism, was born a century ago. The original Dadaists, inspired yet traumatized by the chaos of World War I, were better known by what they opposed than what they supported. They were anti-war, anti-state, antibourgeois, and most famously, antiart. The new company Dada Collective can also be described as anti-art, or at least anti-art as we have always known it. Based on and existing in the blockchain, it takes a step beyond the typical digital art which has gained popularity in recent years. It is dependent on collaboration; the premise is that individuals use the company ’ s drawing software app to create a token on the blockchain and then allow other individuals to build off their work. This echoes a technique patented by some of the original Dada group ’ s contemporaries, the surrealists. Surrealist groups around the world held events at which a piece of folded paper was passed around a table; each artist would create a drawing on one portion of the paper then conceal their work and pass the sheet to the next artist. The end result was a unique and intentionally incoherent composition called an “ exquisite corpse. ” (One such exquisite corpse, created in by the Belgrade Surrealist Circle, its at left). Dada ’ s crypto art collections are essentially exquisite corpses without any of the natural limits imposed on the surrealists; there is no cap for how large the tokenized collections can grow nor any restrictions on who can contribute. Dada proudly claims to be a “ virtual home to people from all around the world—from a bodybuilder in Argentina to an evangelical pastor in the US, a farmer in Kenya, and a former punk in England. ")

Dada has branded itself and its product as a hybrid of “ crypto collectibles and rare digital artworks. ” Aggressively “ artistfirst, ” it describes itself as a place where strangers make art together without expecting remuneration, motivated not by extrinsic rewards like money and status but by internal rewards like the joy of making art, self-development, belonging, and a sense of higher purpose. ” Of course, this space can only exist because it is profitable, an irony that Dada ’ s publicity campaign seems to either wryly embrace or remain completely oblivious to. “The democratization of art is just a euphemism for its commodification, ” we are told by a company that achieved fame through the commodification of its own anti-Democratization (capital D) philosophy of democratization. Confused yet? The Dada-ist salons of last century would be pleased.

How exactly does the Dada Art Collective define and seek to execute its democratizing mission? To answer this question you must study the company ’ s initial efforts to condition the market for its product and provide the public with a compelling From its emergence in 2017 Dada branded itself as anti-establishment and presented the art industry as an “ elitist and unsustainable ” institution that needed to be broken to be built back up. Most problematic, Dada posited, was the relative helplessness of artists within the industry; it claimed that “less than 1% of artists make a living from their own work: ” Flirting with anti-capitalist rhetoric through statements like “free markets prevent art from thriving, ” Dada patented itself as the creator of a new “Invisible Economy ” poised to radically separate art and market. The statement and concept seem both hyberbolic and oxymoronic. Dada purports to differentiate its “invisible economy ” from existing systems through “ organizing economic activity based on interdependence, creativity, and altruism ” In doing so, Dada is simply restating the mission statement of innumerable recent start-ups, not to mention aligning with the rhetoric of established industry titans suddenly trying to rebrand themselves for a younger and more socially-conscious audience. “Anti-establishment” is the new establishment. “Leveraging the wisdom of the crowd without the pernicious effects on the market” is a quote and nothing more; ironically an attempt to capitalize on an increasingly anticapitalist demographic by spinning its own words into a capitalist business strategy.

Dada is at best a new market that is more artist-driven than traditional ones. However, this is still significant. What it does do is to create a more transparent market; one in which anyone can enter and one in which all information can be tracked through the ethereum blockchain. It eliminates information asymmetry in a way similar to Artory.

For young and technologically savvy artists, it provides a nonintimidating and empowering way to connect while making a profit off of creative work.

Dada released its first major collection, Creeps and Weirdos, in 2017. “Creeps and Weirdos ” were NFT’ s before the NFT marker exploded: a collection of 108 drawings split up into over 16,000 digital prints. The tokens were embedded with smart contracts ensuring the artists would continue to receive royalties each time their work was sold. Smart contracts are crucial to establishing artist-first markets both for those selling digital/NFT art (like Dada), and those tokenizing physical art (like Feral Horses). Their implementation made the release of “Creeps and Weirdos ” particularly exciting and generated a substantial amount of press interest at the time.

However, Dada made no subsequent NFT release to build off the momentum. Following the 2018 crypto crash, the company decided to retire the original collection and cut the “Creeps & Weirdos ” supply to just 8300. Then, in 2021, when trying to relaunch the original “Creeps and Weirdos, ” Dada was beaten out by NFT sleuths who found a hidden link allowing them to buy the Weirdos. The ethereum market may be decentralized but there are still security issues and, contrary to Dada ’ s lofty egalitarian motto, major winners and losers. Dada has been largely dormant through the NFT boom as new more blatantly commercialized forms of digital art have dominated the market share. However, some of the company ’ s initial ideas are embodied by the fact that innumerable artists of all nationalities have been minting and selling smart-contract embedded work through platforms like Mintable, Nifty, and OpenSea. One wonders if a main factor behind Dada ’ s struggles is its branding. It’ s difficult to succeed in a booming market when espousing an anti-market ideology. Some of Dada ’ s “ egalitarian ” selling points were that artists couldn ’t set prices for their work and that artists ’ basic income was not tied to their sales. These are hardly tantalizing terms for ambitious artists who, with a little industry knowledge and capital, could release NFT’ s independently of any Collective and increase their ceiling for profit.

Additionally, in the months following the 2017 Creeps & Weirdos release, Dada didn ’t do enough to capitalize on an infant industry with proven upside and extensive room for maneuvering. In the warp-speed blockchain world, “ adapt or become obsolete ” is truly an excellent motto. In this way, Dada ’ s recent fortunes are a warning for those currently establishing themselves in the NFT art space. However, Dada should not be seen as a warning against “ exquisite corpse ” collaborative NFT art. From a cultural and technological perspective, one of Dada ’ s biggest strengths was its facilitation of rapid open collaboration. I believe that new players in the market could have great success channeling Dada ’ s manifestation of this idea. However they should do so in a more business-oriented and less ideological way. By focusing on the “ digital exquisite corpse ’ s ” profitability and generating a stable revenue stream from this dynamic new art form, an emerging company could conceivably establish a foothold in both the NFT and more traditional art communities. The butterfly effect of such a platform would be that artists from around the world could connect, inspire each other, and collect uncapped earnings to an extent never afforded them by Dada.

Ultimately the integration of blockchain into the provenance verification, sales, and creative sectors of the established art industry is at three very different stages. The level of integration is connected to where the pertinent blockchain-based companies fall on the spectrum between “ optimizing and modernizing the current art industry ” to “ opposing the current art industry and representing themselves as an alternative.

Artory and its peers in the provenance verification industry have intentionally developed excellent relationships with powerful auction houses, museums, and collectors. Rather than staging a market disruption around a contentious ideology, their goal appears to be creating alliances with its established players for the benefit of those on all sides of a transaction. By enhancing transparency, they create more trust in sellers, protect buyers, and (as the neutral “ middleman ”) carve out a lucrative niche for themselves. Their success can also be attributed to the fact that they are filling a need rather than attempting to create one. All galleries, auction houses, and highlevel collectors need provenance verification services (in contrast, many would need convincing to invest in fractional tokens or digital art collectives). As a result, companies like Artory have experienced a relatively warm welcome in the market and, despite their rapid emergence, are on a sustainable trajectory to long-term entrenchment. Artory ’ s rise can be analogized to Uber. Uber filled a major market need for private transportation through creating a significantly better, more efficient, and customer-friendly service than any currently available. By using a comparatively decentralized system to do so, it, perhaps incidentally, also democratized an industry. Artory did the same thing in the, albeit much more niche, art market. Similar analogies can be drawn to companies such as AirBnB and Spotify.

Over the next few years it will be fascinating to watch how competition between blockchainbased provenance verification companies unfolds, both in the United States and abroad. Uber, Air BnB, and Spotify, as Artory arguably does today, originally stood almost uncontested as a singular dominant market forces. However, from Lyft to VRBO to Apple Music (among many others), they soon faced intense competition from other opportunistic companies. In particular, Uber ’ s attempt to dominate internationally was thwarted; from Careem in the UAE and India to Yandex in Russia to Bolt in Eastern Europe to Grab in Southeast Asia, locally-based brands started offering the exact same service as their American counterpart and achieved supremacy in their respective regions. Will the same paradigm unfold in provenance verification? How many other companies will arise in Artory ’ s footsteps? Will Artory dominate the United States and Western European art markets while Asian and CIS art markets get taken over by comparable companies? This could be to the detriment of the art market as a whole. Surely a “ centralized decentralized” registry of art that spans the globe would be most helpful at remedying information asymmetry and decreasing the transaction cost for increasingly internationally-focused and crossculturally sensitive collectors.

The concept of tokenizing art and selling it on the blockchain is not in direct opposition to the current art industry; however it does represent a significant disruption in the stream of commerce and adds a new layer of competition to the way art is transferred. The demographic for whom tokenized art investment has the biggest effect is that of collectors/potential collectors. By lowering the bar for investment, fractional art sales allows for both more diversified portfolios and a deluge of new market entrants. Meanwhile, for galleries and auction houses, sales of art tokens could create a valuable new income outlet and a means to create maximal profits from a finite number of works. Furthermore, using blockchain is an excellent way for them to project a cuttingedge modem image, coincidentally ideal for the type of new investors that fractionalized art is designed to attract.

Tokenized art and art as a common means of equity investment are two rapidly developing paradigms that should remain in the industry for many years to come. Companies like Maecanas and Feral Horses, however, have yet to achieve the stable level of success nor demonstrate the long-term staying power of provenance verification companies like Artory. This is easily explainable. Changing how we conceive art ownership, while simultaneously changing the platform on which art is bought, marks a much bigger shift than simply switching the vendor we use to verify our collection ’ s authenticity. It also involves a much larger risk factor, one that gives a deeply traditional and riskaverse industry pause. Will some people, encouraged by the idea that art often appreciates more reliably than blue chip stocks, begin viewing “ art equity ” as an equivalent or superior alternative to many investments currently available in the stock market?

Will buyers be chilled by the idea of never physically possessing the art in which they have partial ownership? The fractional ownership paradigm is still too young for us to fully answer either of those questions. However, it has great promise, especially for emerging artists. If young artists with moderate degrees of success begin tokenizing their work with built-in smart contracts now, it could pay major dividends. Meanwhile, more auctions involving the tokenization of well-known pieces (such as Eleven Broken Chairs) would help crypto-based companies promoting fractional investment gain a larger institutional audience.

Finally, blockchain as a collaborative medium of artistic creation, as tantalizing a concept as it is, was a general failure as envisioned by Dada. An upstart company, Dada not only placed itself in direct competition with the art establishment but also actively disparaged that establishment as broken and publicly expressed a desire to utterly overturn it. This inability to compromise or engage with the rest of the industry likely contributed to why Dada never gained momentum, or major allies, after the Creeps and Weirdos launch. Another probable major factor in the company ’ s decline was that its stated democratization mission was undermined by its many anti-capitalist stances. A supposedly artist-first system that limits artist income has failed to resonate with artists or even aspiring crypto experts…after all, individually-launched NFT’ s have been greatly successful and, to borrow a cringe-worthy but in this case apt colloquialism, have a ceiling of “the moon. ” Dada-type companies still have an opportunity to be successful. However, they would be well-served to forego idealistic hyperboles, advertise themselves as complimenting the art world rather than destroying it, and take a profit-oriented approach to maximize income for artists using the platform.

To return to the Russian constructivists, their glory days were short-lived. By 1930 abstract act was seen as dangerous by the Soviet government; art, the theory went, should not be left open to the viewer ’ s interpretation but instead should present a clear message in alignment with state ideology. Constructivism, once construed as serving the revolution, now ostensibly threatened to destabilize the regime said revolution created; thus it was almost entirely eschewed in favor of social realism. As for the constructivists like Rodchenko? They were faced with a choice; adapt to create statesupported art or attempt to emigrate and continue their careers abroad. Rodchenko did the former, switching his primary medium to photography and depicting Soviet glory through his captures of sporting events and national celebrations. However, his 15 years of constructivist works, and the legacy of his movement, lived on. Constructivist-style artistic groups were formed from England to Germany and beyond; what was suppressed in Russia thrived internationally. A century later, contemporary artists continue to cite the Constructivists as an influence while historians consider Rodchenko and his peers to be seminal leaders in the development of modern art.

Cryptocurrencies and blockchain technology continue to develop at unprecedented speed while the art world, forever tied to the social movements of the day, remains as volatile as ever. The fate of blockchain is uncertain. The trajectory of art is unknown, The two fields could continue to sharply converge or suddenly diverge depending on where the global flashpoint of 2021 leads us. It’ s possible that strict regulatory regimes could spell the end of the cryptocurrency boom, either in the US or worldwide. It’ s possible that the NFT bubble bursts, once again limiting the ways in which creators can promote and sell their work and leading to greater caution about buying tokenized art. However, whatever happens, blockchain technology, just like Rodchenko ’ s constructivists, has left an indelible and as-of-yet unquantifiable impact on art.

Rodchenko and his peers were forced to adopt state-sancitoned artistic styles.

It has revolutionized the way we conceive art and contract around it; in doing so, it has expanded our collective strategic mindset and opened pathways to new innovations thought inconceivable ten years ago. We have learned to harness the power of technology to fight fraud and verify the authenticity of art–even if it is centuries or millennia old. We have learned that there are more ways to invest in art than buying a physical work in a traditional two-party transaction. We have learned that a more transparent market can be profitable for all players, and that a more globally connected market can create unprecedented collaborative opportunities. One common thread extends through all of these blockchain-based revelations: the art world can be for everyone. Most importantly, we have learned that this statement is valid in our current reality: we do not need to revolt against an entire industry (see Dada Collective) or create a Communist dystopia (see the Constructivist age) to make it so. Blockchain technology has inspired a major philosophical shift; it has demonstrated the potential to simultaneously democratize art and maximize profit. With this mission elucidated, and the meteoric rise of new technologies to help execute it, one can expect the coming years to yield major revitalization and growth in the art world.

Want a full transcript of the article? A list of resources?

Just to continue the conversation on crypto, blockchain, and art? Reach out to to us on Instagram @worldofelysium or hit us @ elysiumcocktailclub@gmail.com Above: A collection of NFT' s from Dada ' s Creeps & Weirdos. Below: Van Gogh self-portrait. The most promising space for blockchain and art is in the world of provenance verification. Bllockcahin allows galleries with significantly fewer resources than the Musee D'Orsay and its peers to verify the authenticity of their works.

PORTRAIT OF TUNISIA

My Journey from Hospitable Hammamet to the Scorching Sahara

Ihave often spoken about how Egypt is the ideal two to three-week vacation destination.

Cosmopolitan and chaotic Cairo is an intense culturally immersive experience that blends the finest modern luxuries in hotels and dining with mesmerizing markets and historical heavy-hitters. Aswan and Luxor offer the rugged desert adventure and romance recently brought to theaters by “Death on the Nile. ” The glamor and grandeur epitomized by this masterpiece in cinematography is not far from the truth…from the majestic Abu Simbel to the five-star Oberoi “houseboat” Upper Egypt feels like a time capsule that can take you back 100 or 4000 years. Finally, the Red Sea resorts of Hurghada and Sharm el-Sheikh are my favorite places in the world for a luxurious scuba-diving holiday; the powder-soft beaches, turquoise waters, and unforgettable sunsets are made even more appealing by the fact that they remain largely undiscovered by the “big box ” travel hordes that flock to the Caribbean and Southeast Asia.

Travel in Egypt, of course, has been cursed (or blessed) by the events of the past twenty years. Once a highly touristic country it suddenly became an “ off the beaten track” destination due to terrorism fears and the Arab Spring; one friend who visits the region regularly cited that the amount of vendors outside Valley of the Kings decreased tenfold between his visits in 2010 and 2014. When Covid hit, Egypt’ s resorts, like the country still open, were virtually untouched by foreigners save a selection of wealthy Russians or Kazakhs. My eighteen-day trip to the country in early 2021 remains one of the best of my life. While in Aswan I arranged three days of private temple tours with a longtime member of Zahi Hawass ’ s Egyptology team...on just a couple days ’ notice. In Cairo I had the Coptic Christian Museum to myself. I spent nine days in Sharm el-Sheikh without hearing a word of English…in Alexandria I got lost in ports of pastelcolored boats and ate incredible fish saadiyeh at dockside stalls where I could only communicate by pointing at images on the menu. It was a special flashpoint, and one that will get harder to relive as travel increases post-Covid and Egypt’ s tourism industry rebounds (especially with the Grand Egyptian Museum finally set to open this November)!

Correction…hard to relive in Egypt. This past April I made my first foray into its North African neighbor Tunisia and immediately fell in love. Tunisia has been blessed with Egypt’ s ’ same triple threat combination of vibrant cities, pristine beaches, and desert adventure. Unlike Egypt, however, Tunisia does not have a rich centurieslong history of tourist infrastructure and luxury developments. Tunis, despite sitting on the ruins of one of the greatest cities of the ancient world, lacks the bucket list attractions that inevitably bring the accoutrements of mass tourism. Like Cairo, it inspires the sense that you can discovery something new around every corner; however, with a much smaller population and area than the Egyptian capital it also possesses a distinct charm. I mean all this as a compliment; it’ s a magical city where you can alternately unwind, explore, and immerse yourself in Islamic culture at a relaxing pace. Seaside Hammamet, just an hour and a half away, is a sun-soaked Med resort that international hotel brands have yet to touch…and boutique hotels have made their own. Finally, Tozeur, in the south of the country, is nestled in the Sahara…no river valley here, just an oasis surrounded by sand dunes. Ever in search of remote locations and open desert skies, I initially “discovered” Tunisia through Tozeur; the lynchpin and highlight of my trip, it is the natural beginning for my portrait of the country.

Lost on a desert highway near Tozeur

Had I chosen, I could have arrived in Tozeur via overnight drive in a matroshka (shared van). Not in the hypothetical sense, aka it was an available option for those who ventured to their local Tunis bus station, but in the form of a serious offer that I would have been dumb not to consider. One Thursday, as the afternoon sun descended over Tunis Airport’ s tiny domestic terminal, I was left stranded without a flight and no imminent promise of one. One TunisAir flight leaves Tunis for Tozeur on three or four days of the week; it’ s the only easy means of transportation to the oasis, but, as one might expect when flying into the Sahara, not particularly reliable. On this afternoon ferocious winds had created sandstorm conditions in the Tozeur area; with gusts up to 39 miles an hour we were well beyond the acceptable boundaries of “ conditions in which to fly a stable plane. ” Two and a half hours after our intended departure time our flight was canceled; passengers were told that new boarding passes could not be issued at the moment but that there was another scheduled flight the ensuing day and we could show up at the airport then to obtain a seat. I don ’t trust anything I hear at airports, especially when it sounds like passing the buck. As far as I knew, Tozeur, the inspiration for what turned into a ten-day trip, might not happen at all.

English speakers stand out on domestic North African flights. There were two others in the terminal, one an NGO-type from Germany on holiday with her Tunisian boyfriend and one a 60-year-old New York expat en route to visit his Tozeur-born wife ’ s family. The gregarious New Yorker, for even after building a life in Tunisia he unquestionably was one, had seen this situation many times before and shared my pessimism. He also was a veteran of the Tunis-Tozeur overnight matroshka, was resigned to taking one, and invited me to join him. I considered, played the odds, strongarmed my way into a guaranteed seat on the next day ’ s flight, and demurred. I’ ve never been on an overnight bus before, and didn ’t fancy bumping my way into Tozeur, after three years of anticipating the trip, worse for wear from such an experience. I made the right call. With the weather clear I was in Tozeur by 5 p.m. the next day, and with no checked bags, I was from airstrip to car to resort in less than 20 minutes.

I’ m a connoisseur of desert resorts and when Anantara (owners of eastern Oman ’ s Jabal al Akhdar and Abu Dhabi’ s Qasr al Sarab) announced plans to open one in Tunisia it was immediately on my radar.

Sunset camel trek near Tozeur, during which I met several Berber families The property, like Anantara ’ s similar ones, is built not just to fit its landscape but, like the jungle taking over a Cambodian temple, become a natural part of it. There are no rugged mountains around Tozeur oasis; those are an hour ’ s drive away through flat but ever-changing desert. Thus the allsuite resort, ten minutes out from the oasis and main town, is placed on a nondescript expanse of flat sand. It’ s sand-colored architecture, all squares and right angles, feels indigenous and understated without being austere. Form follows function, but in the stylish and meticulously crafted way that has defined Anantara since the brand, under the direction of architect Bill Bensley, landscaped its initial Hua Hin property.

“terrace. ” It was more of a tiled rectangle…a tiled rectangle that became a gate to the Sahara with a single step. Nights on this terrace were unforgettable; due to the complete lack of light pollution the stars were among the most spectacular I’ ve ever seen. And that’ s not to mention sunsets. One evening I took my fresh mango juice (no cocktails, it was Ramadan), walked out a couple hundred meters into the desert, and sat in the sand in silence just watching the golden sky. I could have continued a couple hundred kilometers, it seemed, without encountering a soul.

On another evening my

“terrace ” became a theater for The English Patient, which was famously filmed in Tozeur. For those who can ’t make it to Tunisia, the romantic tragedy, set during the British war effort against Rommel, offers a vivid glimpse of the local scenery. It’ s not the only time Hollywood’ s taken notice of the area; several Star Wars filming locations can be seen within a comfortable half-day ’ s tour from the Anantara.

For me, the main natural attraction in the area was Chott el-Djerid, a massive salt lake that is today almost entirely dry. One long highway serves as a causeway along the eastern side of the lake; driving down this road without encountering another car I felt like I was in an extraterrestrial landscape. The lake, at over 7,000 km. the largest salt basin in the Sahara, is hot even by Tunisian standards. In the summers temperatures frequently rise above 50 Celsius; in the winter they cool down to a more manageable 35. During these colder months the lake partially fills, hence the skeletal sun-bleached boats that dotted the seemingly abandoned landscape. It’ s a sight that likely would have pleased Jules Verne, whose final novel Invasion of the Sea, a powerful reminder of the powerlessness of humans against nature, was set at the lake.

In Verne ’ s novel, European explorers ambitiously attempt to create an inland sea linking the Sahara to the Mediterranean and facilitating more efficient trade. It’ s an example of an inevitably doomed attempt to reshape our planet. In contrast, the local Berber people have proven that when you work with nature instead of against it you can find prosperity even in the harshest of environments. Tozeur ’ s primary industry is in dates which are the pride and joy of Tunisia and also one of the country ’ s biggest exports. Over 30,000 tons are produced each year, irrigated en masse thanks to impressive wells that, in modern times, stretch over 600 meters down to the water tables. But while the technology may be modern, the distribution system is not; water reaches land plots from the wells through a centuries-old network of streams and channels known as

Hanging out in the middle of now-dry Chott el-Djerid “ seguias. ” The dates lived up to my expectations, whether beautifully plated with a welcome coffee at my hotel or eaten directly off the back of a truck that my driver passed while in town.

Exploring one area of “date oasis ” provided insight into Tozeur ’ s untapped tourism potential. Nestled among the palms on a secluded road that was as much reminiscent of jungle as desert, one entrpeneurial property owner has set up “Sahara Lounge, ” a type of “desert club” that includes a restaurant, a shisha bar, and a variety of outdoor adventures including zip lining and a “ mission impossible ” obstacle course. It’ s the sort of place that bridges the gap between trendy and rustic and could become a tourist gold mine with more resources and a larger market. Indeed, transplant the concept to a place like Oman or Morocco, significantly increase the budget, and you ’ ve got an Instagram magnet. Sahara Lounge is not that, and I wouldn ’t want it to be. But, for the benefit of its owners, visitors to Tunisia, and the country itself, I do want it to succeed.

I cannot, with a straight face, label the Anantara rustic. However, it does have a strong sense of place and does an exquisite job interpreting International luxury through a local lens. For example, the bar area contains an extensive library with more coffee table books on Tunisia and its history than I saw during the rest of the trip combined. One such book, a photo essay on the Tozeur desert, welcomed me to my room. Locally crafted furniture and cushions woven in traditional patterns dotted the property; meanwhile the restaurants emphasized Tunisian flavors and the Iftar spread was as impressive and authentic as any I had.

The highlight of my stay was a sunset camel trek from the hotel. Far from your touristic camel photo op, the experience broke the bubble that often separates visitors from locals and provided a window (not manufactured or choreographed) into how the community surrounding me operates.

Many people I’ ve spoken to conceive Berbers as more inaccessible myth than current social group; my own experiences meeting Berbers in Morocco have felt scripted and stilted according to someone ’ s idea of a tourist comfort zone. In the deserts of Tozeur, though, without expecting it, I met several groups of nomads temporarily decamped in the area. A couple were large multi-generational families complete with the camels, chicken, goats and sheep, essential for eggs, milk, meat, and wool. Seeing the rhythm of their life unfold, if only for a few minutes, was a valuable glimpse into Tunisia ’ s heritage, present, and future. The beat of the desert goes on.

TUNIS: The Metropolis

Perhaps no country I’ ve been to underestimates or undersells its own cultural and historic value more than Tunisia. This is best exemplified by the world-famous Bardo Museum. It’ s Tunisia ’ s most marketable cultural treasure. But, since the dissolution of the Parliament and the closure of the buildings it was housed in, the museum has also been inexplicably closed, with no seeming plans to reopen, for two years.

The paradigm is also evidenced in the ruins of Carthage, located in the north of modern-day metropolitan Tunis. Now just a series of crumbling pillars, 2400 years ago this was the home of the ancient civilization that came the closest to bringing the Roman Empire to its knees. During the second Punic War the great general Hannibal, in a risky yet brilliant strategy, marched his troops from Carthage ’ s Iberian territories over the Alps to strike at the heart of Rome. Moving down the Italian peninsula, elephants and all, the Carthaginians handed Rome a series of major defeats, only stopping their rampage when the Romans invaded Africa as a desperate diversion tactic. This necessitated Hannibal’ s recall, and the tide of the war changed. Largely due to incompetent government, and its inability to pay its own soldiers, Carthage was put on the defensive and ultimately ceded most of its European territories. A furious Rome was not content with treaties. Sixty years after Hannibal’ s death, the third and final Punic War saw general Scipio lead the Romans to Carthage and enact a razed-earth campaign of astonishing brutality. The city was destroyed, all civilians in the streets were killed, and anyone left surviving was sold into slavery. Scipio vowed that anyone attempting to rebuild on the ruins would be cursed; as a result, they remained untouched for over a century. It was not until the late Roman period that people settled Carthage once again, with the city once again becoming a large trading center by the 3rd century AD.

Today the ruins of Carthage are split into seven sites fully integrated among residences, businesses, and parks. They are in a remarkable state of disrepair, with many interpretive signs being sunbaked beyond belief and little security to protect the remaining artifacts. One could easily imagine tourists strolling in with backpacks and out with timeless treasures, a paradigm which used to plague Greece and Egypt but would be unthinkable in those countries today. A certain apathy seems to surround all endeavors from Tunisia ’ s under-funded Ministry of Culture and it trickles down to those staffing Carthage ’ s sites and living the area. I saw only a handful of tourist touts all day and even people who offered guide services seemed confused as to why I would take interest in the ruins at all. This is not to downplay their significance. The Roman bathhouses, the largest in North Africa, looked over a beautiful stretch of the Med. The nearby Roman amphitheater has been incorporated into a modern concert “bowl, ” perhaps losing some historical integrity but definitely gaining in atmosphere. As for the Punic city, the foundations of a great temple and some government buildings can be seen. Most moving, although disturbing, was a cemetery containing the funerary urns of over 20,000 Carthaginian children. The pre-Roman Carthaginians used children for ritual sacrifice and the site at which they were buried, away from the main city and spared the Roman destruction, has remained largely unchanged for over two thousand years.

After the Roman decay, it was Islam that left the next indelible imprint on Tunis. The Medina of Tunis, built in its current iteration between the 12th and 16ch centuries, was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site to honor its position as a major center of Islamic civilization. One can easily get lost in the Medina for hours…though not too lost, as someone who ’ s been to Khan elKhalili several times can attest. You ’ll also have the opportunity to have meaningful interactions with locals and spend time browsing in addition to haggling. The Medina is not a “tourist” market; you ’ re less susceptible to scams here than in a place like Marrakech, and, in fitting with Tunisia ’ s personality, the environment is, for a souk, relatively non-aggressive.

The Roman bathhhouses in Carthage You 'd never guess that the ruins of an ancient civilization were

just steps away.

I also stayed in the Medina, in one of the exquisitely-decorated ancient homes that have now been turned into boutique family-run properties. Dar ben Gacem describes itself as a social enterprise as much as a hotel, seeking to preserve Tunisian heritage while introducing guests to a taste of local life. The property was built in the 17th century by a family of master artisan perfumers and passed down generation by generation for over 300 years until 2006. That’ s when it was purchased by the Ben Gacems, who left the interior largely intact while adapting the rooms for their hotel. My room was notable for its stunning bathroom tile work as well as an ornately decorated bed frame. I turned up onto a set of staircases headed for a rooftop courtyard, which in turn provided 360 views of Tunis. Sitting here at sunset during Ramadan, I found myself surrounded by a cacophony of evening prayers, the loudspeakers of dozens of mosques only interrupted by the shrieks of the many seagulls circling the city. It was in these moments that I got the best sense of Tunis ’ s character: of what is in many ways a pure “ north Africa ” with most alleys and properties completely untouched by Western infiltration.

After sunset, it was off to Iftar through streets packed with jubilant revelers. The vast majority of Tunis restaurants, if not all of them, close for lunch during Ramadan and forego their usual a la carte menu for a Iftar “dinner set. ” Thus I became well acquainted with all of Tunisia ’ s festive classics… and their absolutely massive portion size.

Iftar would typically begin with dates and a plate of pickled anchovies or similar fish. Next up would be a hearty sorba soup (generally with lamb or beef) and a selection of salads including mechouia (grilled vegetables garnished with hard boiled eggs and tuna), eggplant paste, and an octopus salad with olive oil and a complex blend of spices. The highlight of the meal for many locals is the Brik, or “L’Irremplacable Brik” as it was proudly listed on many menus. The Brik is a very thin fried pastry, golden brown and delightfully crispy.

Inside a Dar ben Gacem suite

It contains a rich filling of cheese, egg, herbs, and either tuna or beef. I preferred mine with a generous side of harissa paste, omnipresent in Tunisia and served with almost every dish.

The main course, by this point unnecessary due to the variety of food already consumed, was generally either a meat couscous, makrouna (a tomatosauce based pasta served with chicken, chickpeas, and harissa), fish in saffron sauce, or mloukhia (made with tomato paste, beef, and mallow). Mloukhia is now generally associated with Tunisian cuisine but it originated in Ancient Egypt when part of Egypt was under Hyksos dominion. The Hyksos attempted to torment the Egyptians by fundamentally changing their diet; thus when they realized that no one ate the abundant mallow by the Nile they demanded the the Egyptians cook it. The Hyksos thought it might be poisonous; instead, it became the source of a local favorite that still exists 3500 years later. Dessert was a generous fruit plate and a selection of puddings, with Tunisian mhlabiya (geranium, vanilla, and pistachio) usually being my favorite. Afterwards, it was time for shisha with the locals at one of the jam-packed local bars. Tables poured into the streets to the point where passerby could easily knock over your hookah, and the atmosphere, despite everyone ’ s complete sobriety, was more raucous than at many clubs. The age range at these establishments ranged from 5 to 85; everyone from small children to groups of teens to young families to old couples was clapping and dancing along to the music.

One night I heard a commotion from my hotel room, and, heading up the rooftop, discovered a massive celebration taking place in the courtyard of the next building. Sipping a Turkish coffee I watched the festivities with a couple of other hotel guests; we saw everything from a fashion show to what could best be described as a Tunisian mosh pit.

HAMMAMET: The Seaside

My trip ended in seaside Hammamet, around 100 km. Southeast of Tunis and originally known as a royal resort. There my destination was La Badira, a sleek boutique hotel with monochrome interiors of glistening white. Most rooms have balconies overlooking over the Med; the rooftop indoor/outdoor pool has the same view. Meanwhile the service is the best I experienced in Tunisia; this is the type of white-glove property where the entire staff knows your name within a few hours of check-in. Breakfast was truly above and beyond, starting with a selection of freshly squeezed juices (I typically had a blend of date, lemon, cucumber, and mint) and starring oija, the Tunisian version of shaskhuka. The highlight of my stay was an afternoon of horseback riding with a stable located just behind the hotel; my guide, a proper Tunisian cowboy, gave me free reign to gallop on the beach before taking me out to a couple local Hammamet bars.

Perhaps the place that best encapsulates the essence of a Tunisia experience, however, is Sidi bou Said. Located near the Carthage ruins on the northern tip of the peninsula, this picturesque village, resplendent in white and blue, is nearly a carbon copy of Santorini. Unlike Santorini, it has not been overrun with tourists and does not fill up Instagram story boards. Cobblestone streets wind down past houses that have stayed in the same family for generations, all the way down to a rugged stretch of beach where surfers and kite-surfers come from all over Tunisia to try their luck on the waves. Higher up in the hills a selection of modern art galleries have recently opened, emphasizing local talent and Arabic content. I was particularly struck by a multi-medium exhibition showcasing the work of Yozid Oulab, who draws links between middleeastern heritage and modern Islamic culture. For example, his piece the “Alif” is based on the first letter of the Arabic alphabet but references it in the form of the nail, the first instrument of writing when cuneiform was created back in Mesopotamia. There ’ s also a grand estate and gardens, the Ennejma Ezzahra (or "Star of Venus ") palace. Built at the behest of Baron Rodolphe d'E'langer. a French painter, it is a relic of colonial rule. However, there ' s nothign colonial about its style; the Baron, an avid lover of North African music and architecture, had the estate designed by local craftsmen in traditional Tunisian style.

Inside a Dar ben Gacem suite

Today his estate is where you ’ll find the best viewpoints in Sidi bou Said as well as exquisite examples of traditionall Islamic landscaping.

In researching Sidi bou Said I found several stories of elopements there: couples who ran to this slice of paradise and get away from it all and have returned many times since. I understand the allure; Tunisia is a place where time stands still, and yet at the same time it’ s one that can transport you between milleniums. Some countries enchant with extravagance, others with ingenuity, natural beauty. Tunisia drew me in with its cultural authenticity. An authenticity that, when you want to slide off the hamster wheel of wherever you live, you may find yourself returning to again and again.

ELYSIUM'S TUNISIA BUCKET LIST

WHERE TO STAY:

Tunis: Dar ben Gacem

Tozeur: Anantara Suites

Hammamet: La Badira

WHERE TO DINE:

Tunis: Dar Slah, Fonduk el Attarine, Dar el Jeld Roof, El Dar at the Residence Hotel

Tozeur: Sarab

Hammamet: Kamila, Adra

WHAT TO SEE: Carthage ruins, Chott El-Djerib, Zaytouna Mosque, Ennejma Ezzahra Palace, Galerie Saladin, Bourghuiba Ave.

version of shaskhuka. The highlight of my stay was afternoon of horseback riding with a stables located just behind the hotel; my guide, a proper Tunisian cowboy, gave me free reign to gallop on the beach before taking me out to a couple local Hammamet bars.

Perhaps the place that best encapsulates the essence of a Tunisia experience, however, is Sidi you Said. Located near the Carthage ruins on the northern tip of the peninsula, this picturesque village, resplendent in white and blue, is nearly a carbon copy of Santorini. Unlike Santorini, it has not been overrun with tourists and does not fill up Instagram story boards. Cobblestone streets wind down past houses that have stayed in the same family for generations, all the way down to a rugged stretch of beach where surfers and kite-surfers come from all over Tunisia to try their luck on the waves. Higher up in the hills a selection of modern art galleries have recently opened, emphasizing local talent and Arabic content. I was particularly struck by a multi-miedum exhibition showcasing the work of Yozid Oulab, who draws links between middleeastern heritage and modern Islamic culture. For example, his piece the “Alif” is based on the first letter of the Arabic alphabet but references it in the form of the nail, the first instrument of writing when cuneiform was created back in Mesopotamia. There ’ s also a grand estate and gardens, the Ennejma Ezzahra (or "Star of Venus ") palace.B Built at the behest of Baron Rodolphe d'E'langer. a French painter, it is a relic of colonial rule. However, there ' s nothign colonial about its style; the Baron, an avid lover of North African music and architecture, had the estate designed by local craftsmen in traditional Tunisian style.

The famous Brik