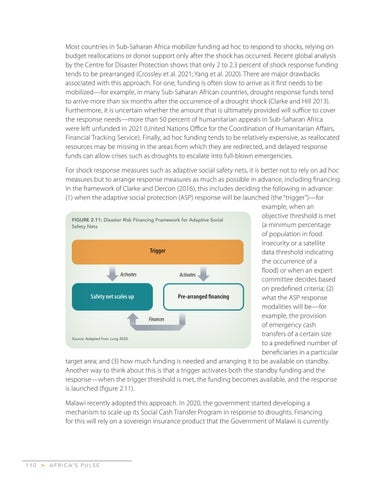

Most countries in Sub-Saharan Africa mobilize funding ad hoc to respond to shocks, relying on budget reallocations or donor support only after the shock has occurred. Recent global analysis by the Centre for Disaster Protection shows that only 2 to 2.3 percent of shock response funding tends to be prearranged (Crossley et al. 2021; Yang et al. 2020). There are major drawbacks associated with this approach. For one, funding is often slow to arrive as it first needs to be mobilized—for example, in many Sub-Saharan African countries, drought response funds tend to arrive more than six months after the occurrence of a drought shock (Clarke and Hill 2013). Furthermore, it is uncertain whether the amount that is ultimately provided will suffice to cover the response needs—more than 50 percent of humanitarian appeals in Sub-Saharan Africa were left unfunded in 2021 (United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, Financial Tracking Service). Finally, ad hoc funding tends to be relatively expensive, as reallocated resources may be missing in the areas from which they are redirected, and delayed response funds can allow crises such as droughts to escalate into full-blown emergencies. For shock response measures such as adaptive social safety nets, it is better not to rely on ad hoc measures but to arrange response measures as much as possible in advance, including financing. In the framework of Clarke and Dercon (2016), this includes deciding the following in advance: (1) when the adaptive social protection (ASP) response will be launched (the “trigger”)—for example, when an objective threshold is met FIGURE 2.11: Disaster Risk Financing Framework for Adaptive Social (a minimum percentage Safety Nets of population in food insecurity or a satellite Trigger data threshold indicating the occurrence of a flood) or when an expert Activates Activates committee decides based on predefined criteria; (2) Safety net scales up Pre-arranged financing what the ASP response modalities will be—for example, the provision Finances of emergency cash transfers of a certain size Source: Adapted from Lung 2020. to a predefined number of beneficiaries in a particular target area; and (3) how much funding is needed and arranging it to be available on standby. Another way to think about this is that a trigger activates both the standby funding and the response—when the trigger threshold is met, the funding becomes available, and the response is launched (figure 2.11). Malawi recently adopted this approach. In 2020, the government started developing a mechanism to scale up its Social Cash Transfer Program in response to droughts. Financing for this will rely on a sovereign insurance product that the Government of Malawi is currently

110

>

A F R I C A’ S P U L S E