62 B o o s t i n g

P r o d u c t i v i t y i n S u b - Sa h a r a n A f r i ca

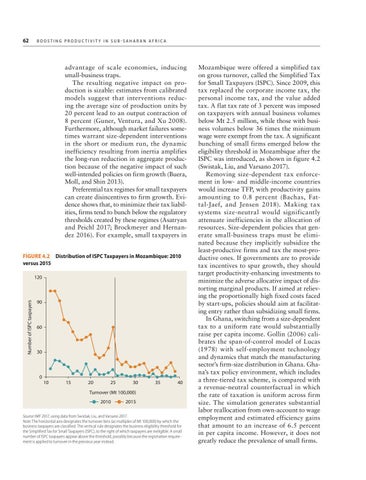

advantage of scale economies, inducing small-business traps. The resulting negative impact on production is sizable: estimates from calibrated models suggest that interventions reducing the average size of production units by 20 percent lead to an output contraction of 8 percent (Guner, Ventura, and Xu 2008). Furthermore, although market failures sometimes warrant size-dependent interventions in the short or medium run, the dynamic inefficiency resulting from inertia amplifies the long-run reduction in aggregate production because of the negative impact of such well-intended policies on firm growth (Buera, Moll, and Shin 2013). Preferential tax regimes for small taxpayers can create disincentives to firm growth. Evidence shows that, to minimize their tax liabilities, firms tend to bunch below the regulatory thresholds created by these regimes (Asatryan and Peichl 2017; Brockmeyer and Hernandez 2016). For example, small taxpayers in FIGURE 4.2 Distribution of ISPC Taxpayers in Mozambique: 2010 versus 2015

Number of ISPC taxpayers

120

90

60

30

0

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

Turnover (Mt 100,000) 2010

2015

Source: IMF 2017, using data from Swistak, Liu, and Varsano 2017. Note: The horizontal axis designates the turnover bins (as multiples of Mt 100,000) by which the business taxpayers are classified. The vertical rule designates the business eligibility threshold for the Simplified Tax for Small Taxpayers (ISPC), to the right of which taxpayers are ineligible. A small number of ISPC taxpayers appear above the threshold, possibly because the registration requirement is applied to turnover in the previous year instead.

Mozambique were offered a simplified tax on gross turnover, called the Simplified Tax for Small Taxpayers (ISPC). Since 2009, this tax replaced the corporate income tax, the personal income tax, and the value added tax. A flat tax rate of 3 percent was imposed on taxpayers with annual business volumes below Mt 2.5 million, while those with business volumes below 36 times the minimum wage were exempt from the tax. A significant bunching of small firms emerged below the eligibility threshold in Mozambique after the ISPC was introduced, as shown in figure 4.2 (Swistak, Liu, and Varsano 2017). Removing size-dependent tax enforcement in low- and middle-income countries would increase TFP, with productivity gains amounting to 0.8 percent (Bachas, Fattal-Jaef, and Jensen 2018). Making tax systems size-neutral would significantly attenuate inefficiencies in the allocation of resources. Size-dependent policies that generate small-business traps must be eliminated because they implicitly subsidize the least-productive firms and tax the most-productive ones. If governments are to provide tax incentives to spur growth, they should target productivity-enhancing investments to minimize the adverse allocative impact of distorting marginal products. If aimed at relieving the proportionally high fixed costs faced by start-ups, policies should aim at facilitating entry rather than subsidizing small firms. In Ghana, switching from a size-dependent tax to a uniform rate would substantially raise per capita income. Gollin (2006) calibrates the span-of-control model of Lucas (1978) with self-employment technology and dynamics that match the manufacturing sector’s firm-size distribution in Ghana. Ghana’s tax policy environment, which includes a three-tiered tax scheme, is compared with a revenue-neutral counterfactual in which the rate of taxation is uniform across firm size. The simulation generates substantial labor reallocation from own-account to wage employment and estimated efficiency gains that amount to an increase of 6.5 percent in per capita income. However, it does not greatly reduce the prevalence of small firms.