we needed some young blood in there—thus his

GOLD: Do you think that even though the Pyramid

invitation for me to join. I was then twenty-six,

Club wasn’t an arts institution, it was nonetheless

going on twenty-seven.

significant for artists to have shown their work

GOLD: So there weren’t as many opportunities for

those kinds of activities when the Pyramid Club was flourishing. SUMPTER: Absolutely not, and you’ve got to

remember too that Philadelphia was under the blue laws then, you know? Nothing was open on Sundays. If you wanted recreation that included music, booze, and dancing, you had to go over to New Jersey, to Lawnside! GOLD: Or have a private club.

there—in a place that you describe as being associated with so much pride? Do you think that having had such experiences and associations helped them as they moved forward in their artistic careers? SUMPTER: Oh, gosh yes. I do, because when the

exhibitions opened, they were by invitation, and the invitations went far and wide in the community of Philadelphia. And they were not limited to the art community—political people of importance would attend. The club was the place to be. These exhibitions were nights to socialize and interact. There were artists you didn’t know two days ago.

Samuel L. Evans (second from left), Dox Thrash (right), and others at the Pyramid Club, 1940s. (John W. Mosley Photograph Collection, Charles L. Blockson Afro-American Collection, Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, PA) Photograph by John W. Mosley

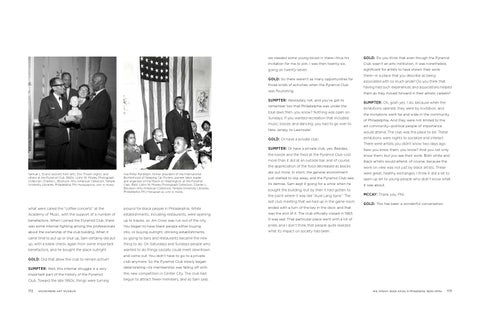

Asa Philip Randolph, former president of the International Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, pioneer labor leader and organizer of the March on Washington, at the Pyramid Club, 1944. (John W. Mosley Photograph Collection, Charles L. Blockson Afro-American Collection, Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, PA) Photograph by John W. Mosley

SUMPTER: Or have a private club, yes. Besides,

Now you know them, you know? And you not only

the booze and the food at the Pyramid Club cost

know them, but you see their work. Both white and

more than it did at an outside bar, and of course,

black artists would attend, of course, because the

the appreciation of the food decreased as blacks

work on view was not just by black artists. These

ate out more. In short, the general environment

were great, healthy exchanges. I think it did a lot to

just started to slip away, and the Pyramid Club saw

open up art to young people who didn’t know what

its demise. Sam kept it going for a while when he

it was about.

bought the building, but by then it had gotten to the point where it was like “Auld Lang Syne.” The last club meeting that we had up in the game room

what were called the “coffee concerts” at the

around for black people in Philadelphia. White

ended with a turn of the key in the door, and that

Academy of Music, with the support of a number of

establishments, including restaurants, were opening

was the end of it. The club officially closed in 1963.

benefactors. When I joined the Pyramid Club, there

up to blacks, so Jim Crow was run out of the city.

It was sad. That particular place went with a lot of

was some internal fighting among the professionals

You began to have black people either buying

pride, and I don’t think that people quite realized

about the ownership of the club building. When it

into, or buying outright, drinking establishments,

what its impact on society had been.

came time to put up or shut up, Sam certainly did put

so going to bars and restaurants became the new

up, with a blank check, again from some important

thing to do. On Saturdays and Sundays people who

benefactors, and he bought the place outright

wanted to do things socially could meet downtown

GOLD: Did that allow the club to remain active?

club anymore. So the Pyramid Club slowly began deteriorating—its membership was falling off with

important part of the history of the Pyramid

this new competition in Center City. The club had

Club. Toward the late 1950s, things were turning

begun to attract fewer members, and as Sam said,

WOODMERE ART MUSEUM

GOLD: This has been a wonderful conversation.

and come out. You didn’t have to go to a private

SUMPTER: Well, this internal struggle is a very

172

MCCAY: Thank you, Phil.

WE SPEAK: Black Artists in Philadelphia, 1920s–1970s

173