Editorial Can You Taste Design?

Explore multi-sensory designs surrounding food

Comic Plants

Hiller Goodspeed on hydrating your plants and yourself

Jack Wagner of Otherworld

Wagner researches the paranormal through story-telling

Editorial Can You Taste Design?

Explore multi-sensory designs surrounding food

Comic Plants

Hiller Goodspeed on hydrating your plants and yourself

Jack Wagner of Otherworld

Wagner researches the paranormal through story-telling

I have been a collector for as long as I can remember. Ticket stubs, postcards, stickers – the material value did not matter to me, I wanted it. I treasured the memories the ephemera held. They were a way for me to keep track of the experiences I never wanted to forget. As a child, I stored them all in an empty cookie tin with baby blue flowers on the lid. Even at a young age, every time I sifted through my collection, I was in awe of the days I was lucky enough to live and the items I had chosen to remember them by.

How we interact with the world is quite similar. We encounter, learn, and grow day after day. We are shaped by every droplet of culture in our communities: the faces we meet, the stories we hear, the food we eat, and so much more. Los Angeles is an ocean overflowing with a myriad of interests. We are on an unsatiable search for captivating pockets of life in our sunny home of LA. Honestly, I am

happy it never ends. It is in our nature to curate. We see. We collect. We share. ODDS & ENDS is our cookie tin with baby blue flowers.

For this issue, we gathered a mix of voices and ideas that cannot help but pop up in conversation. They have been on our minds and now on our pages. They question givens and push for what they plan to be true. We celebrate their inquisitive spirit and the connections they have fosters. We hope this issue inspires you to chase after fascination, or, if nothing else, finds a spot in your collection.

With warmth & curiosity,

SHEINA GALGANI Editor in Chief

CONTRIBUTORS

Editor in Chief

JAYNE HAUGEN OLSEN

Creative Director

BRIAN JOHNSON

Executive Editor

SARA ELBERT

Deputy Editor

JENNIFER BUEGE

Senior Editor

SYDNEY BERRY

Contributing Editor ANDREW ZIMMERN

Contributing Bookings Editors

ALISON OLESKEY

CHELSEA YIN

SHO & COMPANY, INC.

Senior Copy Editor

JEAN MARIE HAMILTON

Spanish Editor/Translator

EDGAR ROJAS

Art Directors

AMY BALLINGER

TED ROSSITER

Digital Prepress Group

STEVE MATHEWSON

BILL SYMPSON

Director of Project Management

FRANK SISSER

Director of Circulation

BEA JAEGAR

Circulation Manager

CARIN RUSSELL

Circulation Assistant

ANNA BURESH

Chief Marketing Officer

TIM MAPES

Director, U.S. Marketing Communications

JULIETA MCDURRY

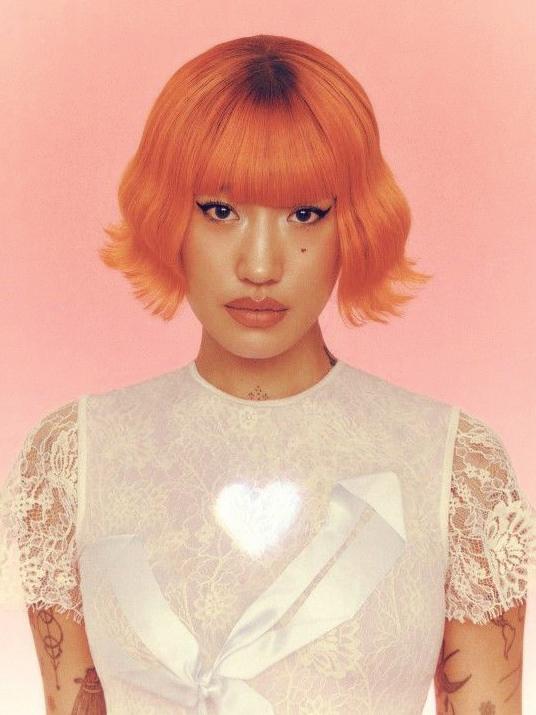

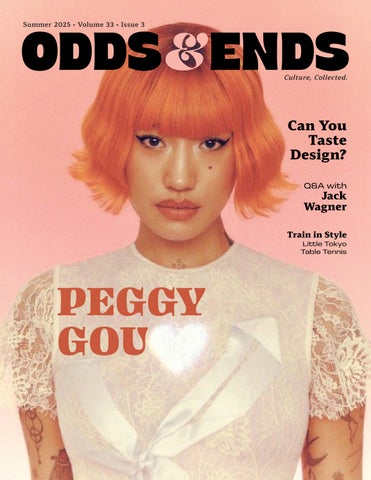

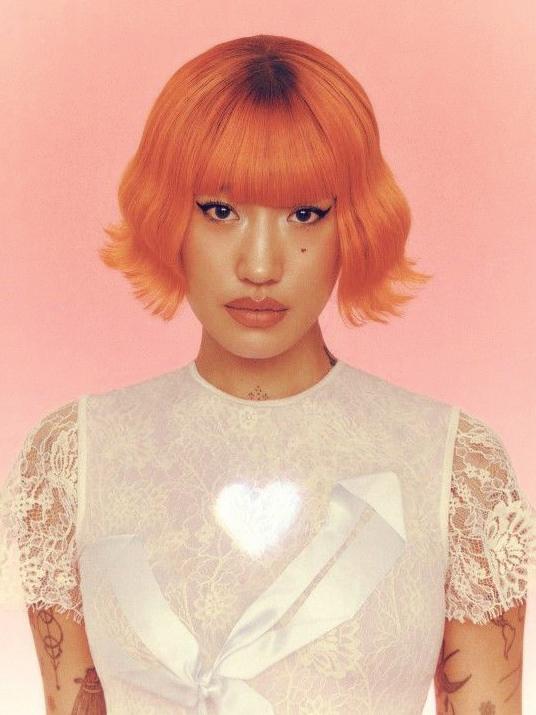

The self-possessed South Korea-born, Berlin-based electronic artist is building a booming business with her uncompromising vision.

By Katie Bain

n a hulking gray building on a wide boulevard once bisected by the Berlin Wall, a silver call button grants access to an expansive, shadowy, unfurnished foyer. Ascend a winding set of stairs and open the door at the top, and you’ll find the office of the CEO: South Koreaborn Peggy Gou, who has swiftly become the world’s most in-demand female DJ-producer working in dance music today.

Inside Gou HQ, the bright overhead lights contrast with the early-April rain outside. The sprawling room — which has a vibe that’s more “friend’s apartment” than sterile corporate sanctum — is outfitted with a wooden meeting table, full bookshelves and a plush green velvet couch from which Gou’s touring manager arises to serve Gou and me black coffee in terra cotta mugs on peace sign-shaped coasters. Gou wears baggy jeans, a black sweater that covers her many tattoos and sunglasses with silver reflective lenses that offer only occasional glimpses of her eyes. Her hair is piled in a loose bun, her skin is flawless, and even in casual mode, she’s giving cool-girl glamour. She offers a quick handshake, closes the window to make sure the room is quiet, then sits down to attend to business. In the last 12 days, her slick brand of house has taken her to Miami, Mexico City and Buenos Aires. Of course, it’s not unusual for DJs to party hop across continents — what’s less typical for a DJ is having an office. But Gou’s story is defined by a business acumen that could be characterized as corporate hustle if it didn’t also happen inside dark techno clubs.

A Korean woman in a scene dominated by white men, Gou, 32, has orchestrated her own dizzying rise, immersing herself in Berlin’s electronic scene upon moving here 10 years ago, then ascending to white-hot producer/fashion tastemaker thanks to last summer’s viral single, and her first Billboard

chart hit, “It Goes Like (Nanana).” This new ubiquity — ever-higher billing at the world’s major music festivals, a German Vogue cover, a 2024 BRIT Award nomination for international song of the year — has neatly teed up Gou’s debut album, I Hear You, coming June 7 through eminent indie label XL Recordings. The rare self-managed marquee artist, Gou has achieved much of her success on her own, and the room we’re sitting in functions as an extension of the command center in her mind.

“I remember meeting managers who told me, ‘I can make your life easier,’ ” Gou recalls. “I was like, ‘How? Tell me.’ Even if you take care of all these emails, you still have to come back to me because no one can make decisions for me. Every decision has to come from me.”

These decisions have produced an expansive business that includes heavy touring; A-list brand deals; her label, Gudu Records; and a merchandise line, Peggy Goods. With strong fan bases across continents, Gou will next be raising her profile even more in the United States ahead and beyond I Hear You’s release.

“Because Peggy has such an incredible touring footprint globally,” XL Recordings head of U.S. campaigns Laura Lyons says, “in the U.S., we’re in a position where, because we haven’t historically had her in the market as much, we need to build on the moments when she’s here in person and also translate the excitement of a globe-trotting DJ to the local market.”

“Gou listened to ‘sh-t,’ ‘good music’ and ‘everything.’ ”

Growing up in South Korea’s third-most populous city, Incheon — where she was born Kim Min-ji — Gou listened to “sh-t,” “good music” and “everything.” She lived in the shadow of her older brother, who’s “like super genius.” Meanwhile, “Study wasn’t my thing. I was kind of rebel. So if you tell me to stay here, I will not stay there. If you tell me to go, I will stay. I didn’t like people telling me what to do even from when I was a kid.”

Her parents, recognizing that their 14-year-old was not “doing well” in South Korea, asked if she wanted to study English in London; she did. In the United Kingdom, Gou lived with guardians but snuck out to parties, fostering a clubbing habit that matriculated with her into the London College of Fashion. She began DJ’ing, booked her own residency at a club in Shoreditch, finished school, moved to

“ If you want to do certain things, do it and fail at it properly.”

— Peggy Gou

Berlin and worked at a record store by day while she was indoctrinated into techno by night. “After one month, I’m like, ‘OK,’ ” she says flatly of her first trips to the city’s notoriously exclusive techno institution, Berghain. “Three months later” — her voice grows louder and more forceful — “ ‘OK.’ Five months later, I was like, ‘I finally get it.’”

Countless eyes fixed upon you can be daunting for an artist, but for Peggy, she sees the scrutiny as a challenge. “I always tell people that if you want to do certain things, do it and fail at it properly. Don’t blame anything, and don’t make an excuse. You have to learn your lesson by doing it.” While the music industry boasts innumerable lessons to learn, sometimes the most important thing is finding a place to rest one’s head, if even for a moment. This is a feeling Peggy follows outside of music as well, finding solace and regeneration in her home and with her family in South Korea. “That’s why I like spending time in Korea,” she shares, “because this is where my family is; they give me peace. And you know, they will accept you for any kind of form you are at. So it makes me feel like I can be whoever I want, or I can show them any kind of shape of me, and they will always love me and support me, no matter what.”

One of the biggest early critiques Gou experienced side-eyed her interest in

fashion, which made her fear “that people would never take me seriously.” So during her early years in Berlin, she sported the de facto DJ uniform of black (and sometimes, maybe, white) T-shirts — a fit that never felt authentic. Around this time, a mentor told her to turn her perceived weaknesses into strengths, so she ditched the tees for couture.

Dressing in bright sets and racing gear helped her catch the attention of top fashion houses like Louis Vuitton. She was good friends with late DJ-designer Virgil Abloh. Her own Peggy Goods line creates custom merch for each of her live shows.

Now other DJs ask her how they can expand their own brands into the fashion world. It’s speculative, but the most obvious answer seems to be to work as hard as she has. “People see that I’m riding in a Rolls-Royce now, but I used to take a f–king bus,” she says. “I did an interview in Korea recently, and the first [comment] was, ‘I smell old money.’ No. My dad was poor. My mom was average. I’m not from a rich family. I worked hard to have a glamorous life.”

Like most anyone who has achieved major success and its attendant visibility, people still give Gou sh-t. But in a true boss move, she has come to enjoy it. “Now when I hear criticism, it means I’m doing super well,” she says. “So go ahead: Say my name.”&

Peggy Gou on finding inspiration in Salvador Dalí.

“ I have always loved Dalí. He was living in a future that only he could see and he was the very essence of what we consider to be ‘not normal’. I find that very attractive. The title of one of his sculpture pieces is Lobster Telephone and as soon as I saw it, I made a mental note that it could be an incredible track title. In the song, I’m singing in Korean, but even Koreans won’t understand what I’m saying –it’s more of a message that says, ‘I know you don’t understand me, but everything is just the same.’ I think that’s a good fit with Dalí’s surrealist ethos. ”

EMOTIONAL PADDLE COVER $42

Fits all regulation Shakehand and C-Pen grip paddles. Spacer mesh with full emotional sublimated expressions. 6.75” across, 6.5” wide. green concern

KAITEN TOP V.4 $62

Women’s sleeveless top. Sublimated prints from a mid 00’s photo of commemorative tournament doll. Available in XS, S, M, L, & XL. egg

COTTON BANDANA $36

Full color print cotton bandana. You can sweat in it and wash it – it will get softer. 24x24 inches.

LTTT CLUB CAP $43

100% cotton cap. Embroidered eternal LTTT logo. Will increase table tennis capabilities. Poche woven tab label. One size & adjustable. o2

LTTT shorts for playful behavior on and off the table. Printed label inside waistband and LTTT broken logo woven label on right leg. Available in S, M, L, & XL.

Play at Little Tokyo Table Tennis (LTTT) every Tuesday from 6-9pm at Terasaki Budokan in Downtown Los Angeles.

Shop: lttt.life Store: 309 1st St, Los Angeles, CA 90012 Updates: @littletokyotabletennis

Eating is a multi-sensory experience, and the design surrounding food from restaurant interiors to menu typefaces can have a tangible impact on that. But with gentrification tearing out eateries with an ounce of individuality, is this distinctive visual experience now being forfeited?

Olivia Hingley

or many, eating out is one of life’s greatest pleasures, but it’s never just about the food, is it? A few weeks ago my flatmate posed a question when we were sitting around our table having dinner. “You’re out for a meal. You’ve got food, service and ambiance, one has to completely flop—what are you picking?,” she asked. Obviously not food, right? But imagine eating the best food you’ve ever tasted, but you’re sitting in a sterile white box and the food was practically thrown on your lap. It doesn’t sound too tempting.

While we may not have come to a unanimous conclusion (do these things ever?), the question did raise some interesting points, mainly that ambiance matters—a lot. Many of our memories of great meals were intertwined with how the setting looked and made us feel. The sign that welcomes you in, the menu you hold in your hands, the decorations on the walls, even the website you’ve likely trawled (the day before) to decide what you want; arguably, they all add to—and enhance—the way you taste the food.

Though, right now, it seems we’re at risk of losing this multi-sensory experience. For years, the gentrification and commercialisation of UK cities has been pushing out independent, grassroots eating spaces with unique visual legacies, only to be replaced with cookie-cutter chains that visually rely on the ease of brand recognition as opposed to providing a well-rounded and distinct dining experience. This has only been exacerbated by food design trends that put homogeneity, minimalism, and ‘refined’ design above all else. It begs the question, could these changes not just be ruining our high streets, but the very way we taste and enjoy food?

Since 2013, the designer, researcher and author of Why Fonts Matter Sarah Hyndman has been conducting experiments into how our eyes and other senses “sway our perception”. In particular, Sarah focuses on how typography influences and impacts our senses—she even coined a term for it: typosensory.

“Rounded typefaces will evoke feelings of creaminess, and sweetness…while jagged, spiky type is associated with strong, aversive flavours, like sourness.”

— Sarah Hyndman

Sarah’s typosensory research is mainly compiled through mass participation experiences which she takes to conventions and talks across the UK, and sometimes conducts online. Past experiments have involved testing how the taste of a jelly bean changes when paired with a different font, or asking audience members to vote on what type of coffee they’d be ordering if they were just going off the font being used to present the word ‘coffee’—the same with wine.

Over the years, Sarah’s developed a few general findings that often ring true when accounting for our limbic responses—“your completely intuitive responses to letter shapes”, she explains. In this instance, very rounded typefaces like your Vag Rounded will evoke feelings of creaminess, and sweetness—in her coffee experiment the most common answer to the rounded, curving type is a frappuccino—while spiky, pointed type like Albertus is commonly associated with strong, aversive flavours,

Designer Jingqi Fan crafted the identity for the New York-based Chinese eatery MáLà Project emulating the key flavours of their trademark dish— Sichuan dry pot.

“Design isn’t just about what you see—it’s about what you feel, taste, and experience,” says Jingqi. “The onus is on the designer to extract the most representative aspect of a particular taste and translate it into something tangible, because it will then set the stage for how we experience taste.”

Colour was one of the main means by which Jingqi recreated the flavour combinations of dry pot—spicy, mouth tingling and numbing. Jingqi opted for chilli red—the colour of “chilli peppers and fire”—but also a central colour to Chinese culture, often being used to reference luck and joy.

like sourness. In the same coffee experiment the most jagged type is always chosen for americano, or espresso.

Though what begins to make things really interesting for Sarah, is when context kicks in, “when you get the social meanings, the next layer which you’ve been learning your whole life”; a few months ago, this tweet highlighted how even just a preliminary glance at the Papyrus-filled menu screams “country pub”. At this trajectory in Sarah’s experiments, it’s clear that in general rounded typefaces are often associated with cheapness, and lacking in depth of flavour, whereas more pointed typefaces are associated with depth of flavour, a more refined palette. It’s interesting to deliberate on why the latter has come to represent higher end, more expensive restaurants—have they been playing on a combination of our limbic and contextual associations; welcoming in those ‘in the know’ with enough cash to splash?

Playing on associations of the audience is irrefutably a part of the consumer design process, but another facet of Sarah’s work is helping us to understand these associations,

and how doing so might help us hold onto our autonomy. In these instances, one typographic choice that Sarah often sees used to promote the idea of “organic” or “craft” is distressed textures—think dark chocolate and small-brew beer. So much so that a few years ago, Sarah recalls a friend of hers saying how much better McDonald’s organic burger tasted than the original. In reality, there had been no changes to the recipe whatsoever. What had duped Sarah’s friend was the distressed M logo on the packaging, which was in fact rolled out to represent that the chain was using recycled packaging. Now, here’s a clear instance of those contextual associations kicking in. “I was really intrigued,” Sarah says. “It signalled that if you assume something is organic, it’s going to taste better—your confirmation bias kicks in and you look for proof.”

After years of research, if Sarah were to give any piece of advice to a designer creating the visual identity for a restaurant, it would be to actually try the food on offer. “I’d first go and sit there and eat the food, sit in the space, soak up the atmosphere, see how people are responding to it,” she says. “Don’t try and foist this idea of what good taste is. What is authentic to that place?”

“If you’re interested in these places, dedicate your spare time to actually going into them and spending your money in them.”

— Isaac Rangaswami

If you’re on Instagram and you like your food, there’s a good chance you’ve come across the account Caffs not Cafes. Run by the freelance copywriter and restaurant writer Isaac Rangaswami, it shines a light on vernacular food spots across London—the sort of places that you likely won’t see celebrated in mainstream food journalism. At first Isaac created the page to spotlight (you guessed it) caffs; for the uninitiated, think £5 fry-ups, thick-breaded ham sandwiches and vinegary chips. Then, later, he broadened his remit outside of caffs to include other spots with some “commonalities” or a “similar spirit”, perhaps an Indian-cuisine canteen one week, and a family-run Chinese restaurant the next.

What feels so special about Isaac’s in-caption reviews is how much attention they pay to the atmosphere, the smells, sensations, and the physical space of the eateries: their old signage, hand-painted menus, to the more specific features, like a Coca-Cola lampshade, for example. Woven together with drool-inducing descriptions of food, his words prove that the visual aspects of an eatery are not just a byproduct, far from it—they are an integral part of the eating experience.

One thing Issac is keen to impress is that he doesn’t believe himself to be ‘discovering’ these places—he’s not really a fan of the term “hidden gem”. Many of these eateries have a longstanding legacy in their local area, with clientele that have been walking through their doors for years. Isaac’s trying to bring such spots to a new audience, doing his bit to ensure their legacy lives on against the tides of gentrification.

Since starting Caffs not Cafe’s Isaac’s developed nostalgia for a time he never experienced, nursing the ever-increasing feeling that he missed a “golden age” in London. Moving to the capital ten years ago, many of the iconic spots that Isaac’s read about have now shut up shop. “I get this impression that central London in particular has become a lot less interesting,” says Isaac. “There are much fewer choices for inexpensive places to eat that aren’t chains. And even the chains aren’t particularly cheap, are they?”

Now, to truly find “distinctive” eating spots you’ve more often than not got to travel to the outskirts of London. Isaac reiterates a point he’s made many times before: “if you’re interested in these places, dedicate your spare time to actually going into them and spending your money in them”. He makes a good point. It’s easy enough

to complain that there are no local restaurants or places to eat for under a tenner left, but if we’re really going to to keep these spots alive the simplest way of doing so is actually going and enjoying them— putting your money where it matters.

So whether you believe design can actually be tasted—or not—it’s hard to refute that the visual aspects attached to our culture of dining are irrevocably tied to the way we experience and enjoy food. Greater attention to the nuances and connections between our senses will not only help to create the interesting eateries of the future, but help to maintain those that already exist. &

hen Wagner started his podcast Otherworld in October 2022, his mission was to create “the most normal paranormal podcast.” For Wagner, his career has always been about giving people a space to tell

their stories. Now those stories range from encounters with mysterious creatures to the very real study of the depths of human consciousness. Close to 100 episodes later, his show about people’s real encounters with unexplained phenomena has developed a cultlike following. Here Wagner shares where he stands on the paranormal and why this summer almost brought him to his professional breaking point.

O&E: How do you like to source your stories for the podcast?

WAGNER: We have a lot of emails. Sometimes it’s a lot of backand-forth with a person. Sometimes we vibe them out on the phone and then oftentimes a lot of the work gets done in the interview. For some of the bigger stories, it’s a prolonged process of getting to know them and editing and hitting them up after. I get to know these people really well. This stuff is happening to people who just don’t know who to tell. And people who also don’t even really feel like having it be a part of their life. This stuff is really jarring when it happens to people and can really screw up their head sometimes. I think most people just wanna get back on track and they’re really not trying to dwell on it. They’ll chalk it up to something—“Oh, it must have been the wind.” I even do that myself.

I imagine there are people listening and engaging because they believe, and there are people listening and engaging because they’re skeptical. Is there ever a time when you’re like, “Oh, this person’s f*cking with me,” or do you approach everything in good faith?

I try to approach everything in good faith. It’s not like I’m putting these people through the wringer. This is their subjective experience, no matter what anyone thinks of it. But I think most people assume that there’s a lot of stuff just being made up whole cloth. I guess maybe that’s nice to think, but in practice, it’s just not the case. I’ve definitely encountered some stories that for various reasons I didn’t think were right for the show. I’m sure there are people who make sh*t up for attention. I’m pretty good at spotting that. But usually this stuff is complicated and has had a major impact on this person’s life.

The episodes aren’t just based on anecdotes, but include a lot of research that contextualizes the experiences.

Research is difficult with this stuff because nobody knows the answers to this. I was really interested early on in ethnographic filmmaking. You’re filming a group of people living in isolation, they don’t even know what a camera is. And a major part of ethnographic film making is that you’re not trying to tell a story. You’re just recording for people to use later, because in the future anthropologists need to be able to look at actual footage of these people living, doing their thing. That’s how I look at what I’m doing. All I need to do is help these people tell their stories the best they can.

How does researching and interviewing and talking about the paranormal 24/7 affect your headspace?

I was gonna do this show as a miniseries. My hope was like, I’ll put out eight episodes in October and then maybe somebody will give me money to make eight more. And I’ll work on them through the year and then next October I’ll make more. And I got an agent and I remember my agent laughing at me. He’s like, “You’re not allowed to stop.” I’m like, “Dude, I don’t even know if I can physically make the episodes weekly.” And he’s like, “You better figure it out.” So I walked out of there and I’m like, I’m going to fail, but let’s see how long I go before failing. And I just haven’t stopped. It does have a big impact, but not the paranormal aspect. Sometimes these stories are a person’s entire life. It can be all-consuming, and put me in a place that’s not been good. This summer I got pushed to the brink. I found where the brink was.

It’s funny that you’re like “Demons are whatever, but the deadlines…” Have you found that you’ve become numb to the subject matter?

“

It’s about balance. When it becomes work, you can become numb to the magic of it.

”

But what I found is that the opposite can happen where you can accidentally go too far in. I do find that belief is a drug in some sense. But as interesting as ghosts and demons and the afterlife is, I’m really more interested in life. What keeps me going is some of these stories are bigger that a podcast. Otherworld, I don’t like to think of it as a podcast. I never did. I always hoped it would be a larger home for covering these topics in a certain way. &

by Hiller Goodspeed

saturday august 9 2025 doors 7 pm show 8 pm all ages