A rising star in Cleveland’s art scene, Newell’s emotional, figurative sculpture is instantly compelling and leaves one wanting to know more. We first found her work in the window of our framer’s shop and found our way back to her studio in an old industrial building. There we met the brilliant, hard-working artist amidst a gaggle of other captivating work, leading to WOLFS’ first exhibition of work by a younger-living artist.

Kristen is a trained, talented, highly motivated artist with an emotional sensitivity to our ever more tumultuous world. She doesn’t need to search for subjects, she has more to say than she can physically create. Her primary medium of clay really suits the strong softness of her mostly figural compositions.

Sometimes you see things for which you can’t reconcile your attraction. Even though, over the past few years, Kristen has become an important part of the gallery, there still remains a beautiful mystery in her work that we all revere.

Sculpture, the most tangible of mediums, seems an odd choice for the evocation of dreams. But Kristen Newell’s sculpture seems to give voice to ancient myths, mysteries, and archetypes.

Her sculptures have a feeling of very long ago, as if they were made in a time of ancient religions or classical myths, by artists who gave voice to deep messages which we only half understand and whose individual names have been erased over the passage of time. Her sculptures bring to mind folk art; Eskimo sculpture; the pottery dogs and other creatures of Pre-Columbian Mexico; the archaic sculpture of the Cyclades; the early Kouros of ancient Greece, before such sculptures became highly realistic, from the period when they still had a monumental, somewhat Egyptian quality. At times her work has a modern quality as well, in particular with reference to modern artists whose work conjures up mythic, archetypal feelings: for example, the sculpture of Hans Arp, Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore, and the Surrealist paintings of Picasso.

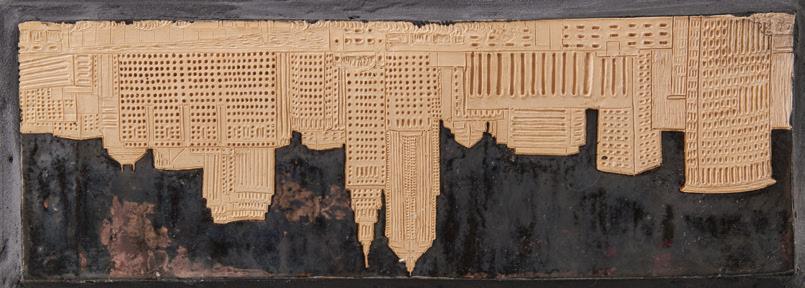

At the same time, her work gives a voice to issues that are very contemporary: feminism; fearfulness about Global Warming and the survival of our planet; a concern for the plight and rights of animals. It feels at home with our anxious present: with jazz music; with punk rock; with the bombardments of television news; with the crumbling buildings and sidewalks of our decaying cities; and with the beauty of the damage all around us. There’s even a touch of political messaging in her work. As she confesses: “Growing up by the ocean and by Lake Erie, I’m very stressed out about the fate of humanity and what we’re doing to the planet.”

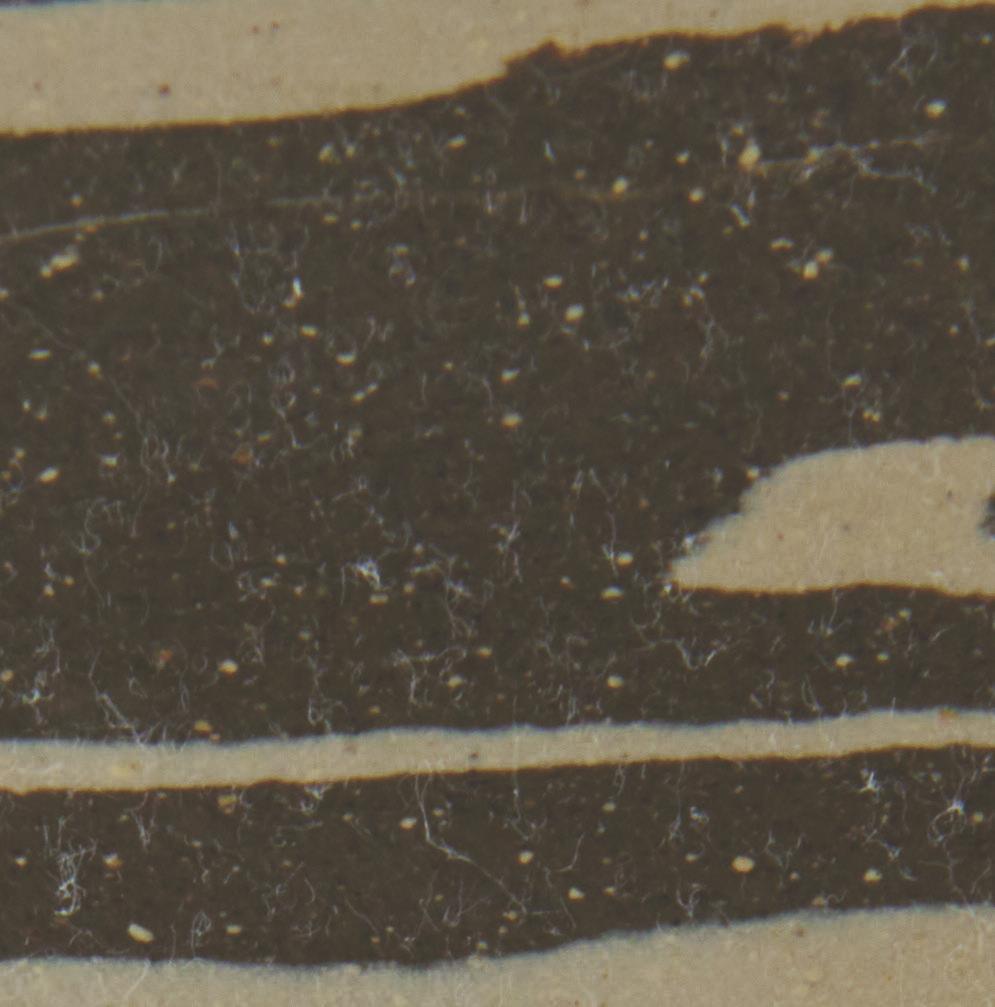

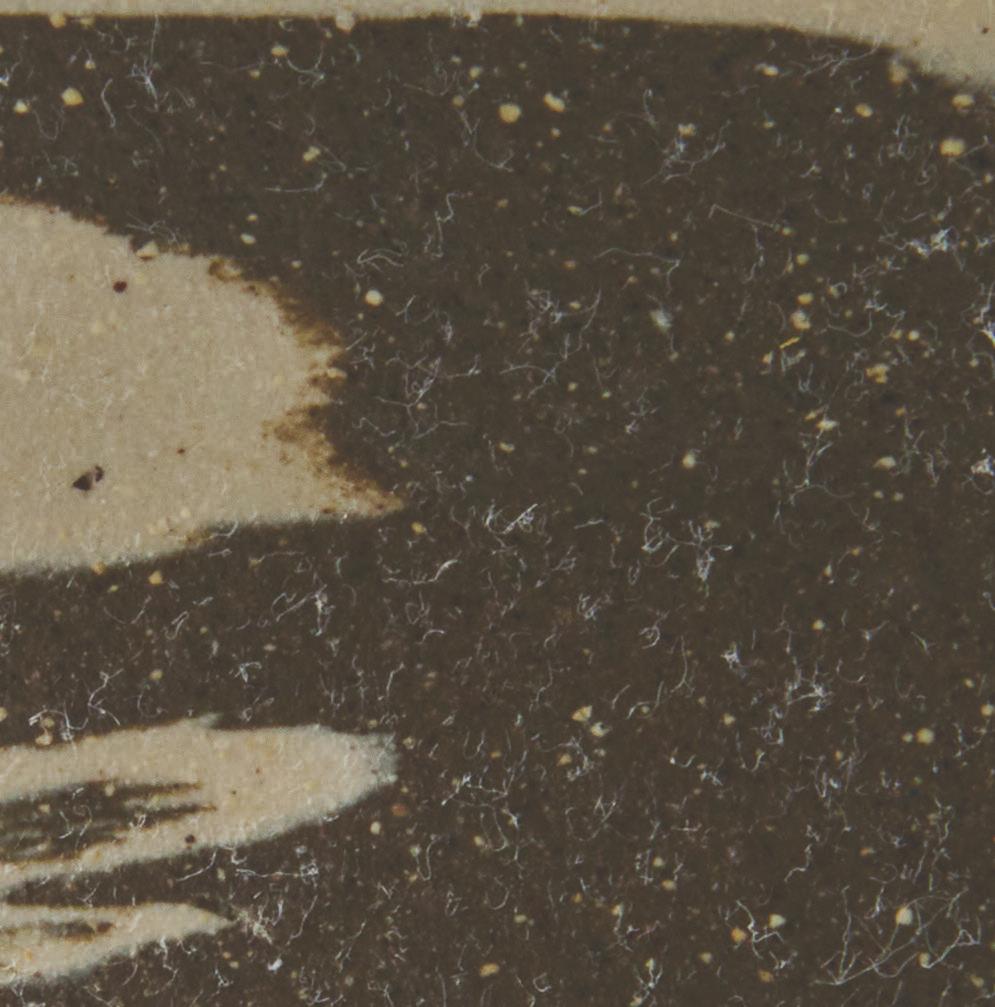

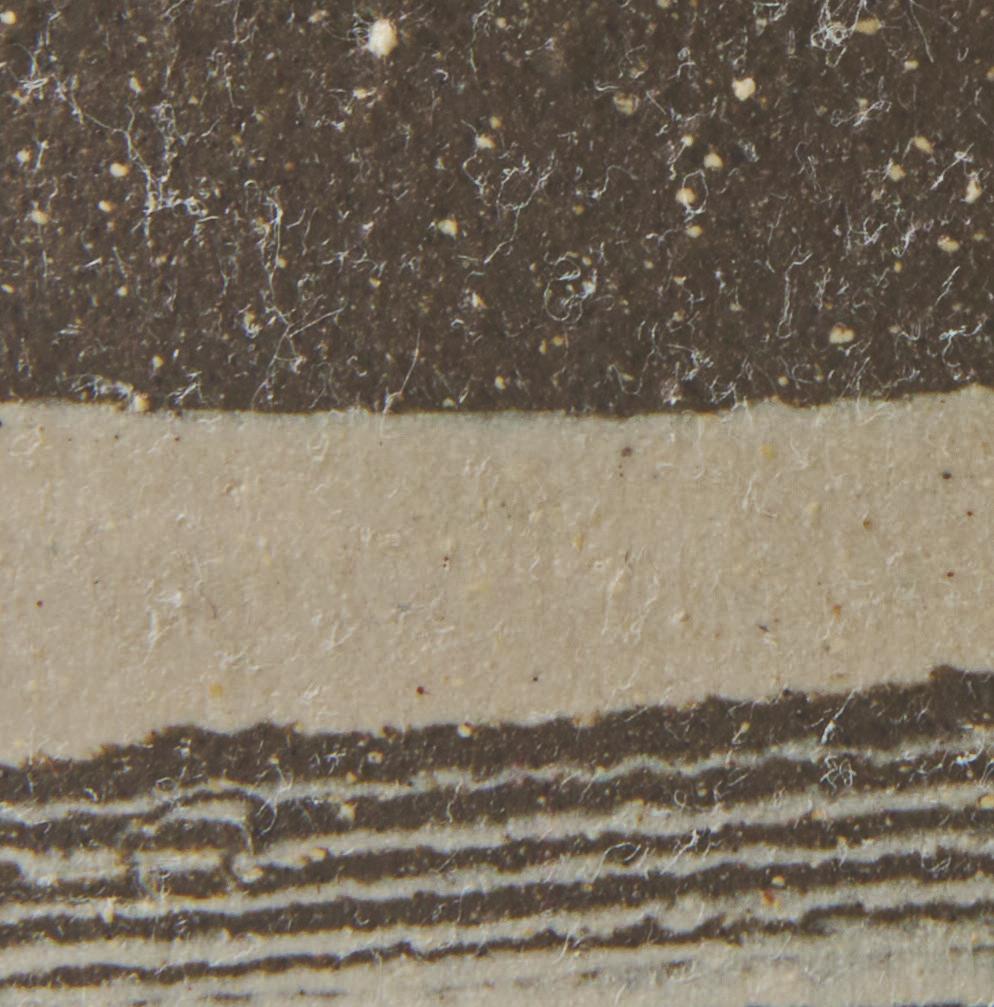

While not exactly self-taught, one of the odd things about Kristen’s art training is that she didn’t particularly focus in school on pottery or sculpture, which have become her principal modes of expression. Her skills with clay and modeling were largely developed on her own, working from primal instinct rather than what she learned in school, as were the technical challenges she has confronted in making her work—operating a kiln, firing large clay vessels and sculptures, which have a tendency to warp and bend from the heat, and often can explode. Rather than seeking to hide this lack of rigorous technical training, and her struggles to get things to turn out right, she often glues back together pieces of sculpture that have broken off or shattered, leaving the seams clearly visible. For her, the breakage so openly revealed is part of the expressive statement. And she also observes that, somewhat paradoxically, the seams from breakage are the strongest part of the finished piece.

Her knowledge of the human figure comes not from training in sculpture but from life-drawing, including drawing figures in movement performing ballet. But for the most part she does not make sketches but develops her ideas while actually working in clay. The concept evolves while the work is being made, and she remarks that: “I’m not done with a piece until there’s something I find out while making it that’s brought into it.”

“I often start with a feeling and the imagery that goes with that feeling comes to me and gets incorporated in different ways.”

At this point let me interject a bit of biography. Kristen grew up in Ipswich, Massachusetts and from early childhood her parents encouraged her and her sisters to pursue artistic activities, and always had paint and clay on hand for them to work with. She started making art at an early age and just never stopped.

As a child, she was surrounded by artwork; she was taught by a gifted sculptor Sherri Brown in preschool; and in kindergarten became close friends with the granddaughter of Paul Manship, at whose home she became enamored with his sculptures, and with sculpture as an art form. While in high school she was inspired by a gifted art teacher, Brian Carman, who encouraged her to work with a variety of different media and who exposed her to cutting edge art by figures as diverse as Dave McKean, and that master of subversion, Marcel Duchamp.

Newell continued her studies at the University of Vermont, where she did painting, photography and a little bit of ceramics. To get more intensive art training, she then did one important semester at the Cleveland Institute of Art. She then returned to Vermont to rejoin her community of peers, studying a broad scope of subjects.

Indeed, the mysterious qualities of her art are clearly related to the variety of things that catch her attention, which are mysteriously woven into what she creates. For example, here’s a brief summary of what she’s interested in right now:

“I read, listen to music, and see friends. I like to amateur dabble in philosophy. Lately I’ve been reading some of Ocatavio Butler’s sci fi, and also ecology books about mycelium, an underground network intermingling with plant roots, whose fruiting bodies are mushrooms. One of my heroes remains Jane Goodall, and the way she went out into the wild to understand chimpanzee culture. There’s more to animal societies and expression than people acknowledge.”

She moved out to Cleveland just after graduating from college, arriving in 2012—which as it happens, is the last year of the Mayan calendar. To survive, she has taken on a variety of odd jobs, from teaching to picture framing, and she has had a number of shows, starting with group shows at the River Gallery and at the Ohio State Fair. In 2019 she had her first solo exhibition at Brick Ceramics, and has had exhibitions at a variety of venues here and there in Cleveland, including Waterloo Arts Fest, Waterloo Arts Gallery, Abattoir Gallery, and Gallery U.

Let’s look at a few examples of her work. Through most of recorded history, sculpture of women has been made by men, who have objectified women. In a fashion that might alternately be described as beautiful, inspiring, and also, at times, more than a little bit disturbing, Kristen presents a different point of view. As she declares:

“I’m frustrated that a lot of female figures that exist were made by men and I want there to be more representation from a woman’s perspective.”

In Husk (2020), for example, the focus is not on the female body’s layer of skin but on what’s happening inside. In this case, she started from the ground. As she recalls:

“I formed the feet of Husk around my feet as an exercise to soothe myself after a traumatic loss. In the beginning of my grief I had to keep moving to gain enough distance to find perspective, it felt like trudging up an endless staircase.”

From the ground, a stairway leads up to the genital area, and from there in Kristen’s words:

“A tree representing life force, natural and rough, grows through temple forms in the abdomen, breaking apart a linear grid in the chest. The grid is a metaphor for my human constructions, barriers, and projections that could not contain the realities of nature.”

The staircase also continues upward to the head, and at that point, in an expression that brings to mind the double-faced women of Picasso:

“The face swings open to let the energy free, the real substance of the work is no longer in the sculpture, husk refers to the figure left behind, like an exoskeleton, cocoon, shell, or an abandoned city. The figure looks outward, with arms above its shoulders, hands clasped on the head; if light threw a shadow, the arms and head would create an eye shape.”

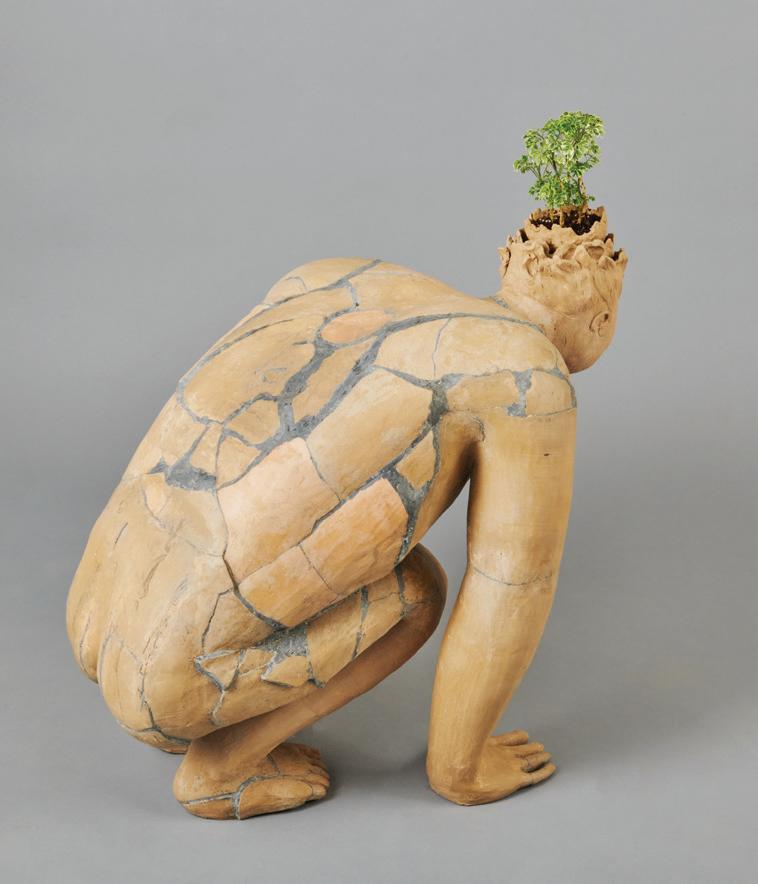

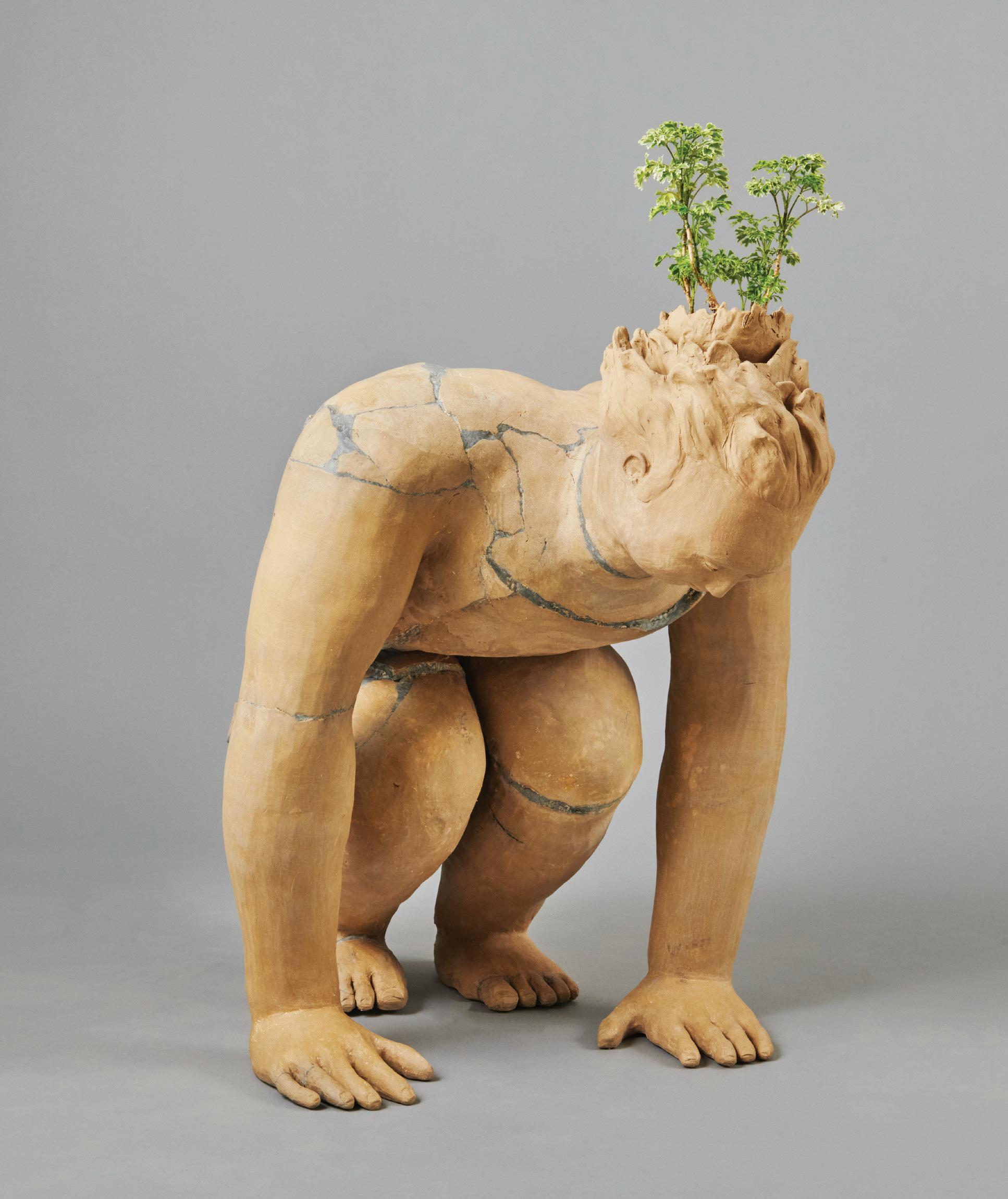

Like Husk, Bather with Flowers (2023) also contains echoes of emotional trauma. The bent pose of the figure developed as she worked on it, and has a quality that’s not strictly realistic, but surreal, and that feels like an expression of inner forces, inner emotions, and of things twisting and pulling in strange ways. “I’ve been doing these elongated, wavy figures that give motion to the static object,” she remarks, and then adds:

“I constructed the figure first. And then the tub. Water and baths and showers are all very calming things to me. I had just broken up with someone and the subject is a bit like the Rodgers and Hammerstein song in South Pacific: “I’m going to wash this man out of my hair.” It’s just kind of letting go.

The flowers were ones that my former lover gave me. I had dried them out and was going to send them back to them, as a sort of statement of heartbreak, but then I decided to add them to the piece.

I was transporting the whole thing in my car, left it in my freezing car overnight, and the clay and resin cooled at a different rate, creating cracks and breakage. So I epoxied it back together. I don’t try to hide breakage of this sort, whether caused by freezing or uneven temperatures in the kiln. The damage makes interesting patterns and the places where it’s been glued together are actually the strongest parts of the piece.”

The piece has striking formal visual qualities, but also explores metaphors in a thought-provoking way, and this is a recurrent undercurrent of her work, as is the emphasis on plants and nature as a source of healing.

The notion that plants provide healing, for example, is expressed very directly in River (2020)-made with ceramic, glaze, beeswax and dirt--in which rippling blue and green waves wrap around the figure up to the neck, and the head is hollow, with a plant growing out of it. As Kristen writes:

“Rivers feed life, carry news, forge paths, swell and flood the landscape; they are peaceful, violent, and essential. There are rivers of the underworld, Tao, flow, lineage. I was feeling chaotic with news, loss, and the pandemic, I wanted to put those feelings into a grounded figure, allow them some physical weight. The color scheme is intended to suggest a stone figure sitting in a river up to their armpits. The river flowing around them represents the chaos and the salve. The gesture is of still observation, the plant is the fruit, the growth; it brings life to the piece and requires water.”

Somewhat similar in its symbolism is PersephoneRising (2021), in which a female goddess fuses with a tree. The deeper message is that of female power, and its harmonic connection with the natural growth and the animating life force of plants and trees. Kristen recalls:

“We’re familiar with the story of how Persephone was raped by the God of the underworld, but I was reading about an earlier version of the myth in which she isn’t kidnapped. Instead she persuades her mother to let her take care of the underground and her mother shows her the way down. She’s not a victim but the embodiment of deep spiritual powers. The sculpture started as the base of a tree growing out of the earth. When I had completed the base of the tree I put a piece of glass over it to provide support as it rose, and then I did the upper part of the tree with the branches and the figure of Persephone intertwined with them. I did the figure from imagination, building it into the tree as I was building the branches as well. Persephone and the tree took form together, almost as one thing. The woman fuses with the growth forces of the tree.”

Somewhat more obscure in its symbolism is 200 Million Years (2022), which features a nude woman on all fours covered by the shell of a horseshoe crab and placed upon a medicine cabinet mirror. Because the figure is covered by the shell it’s largely invisible; what you see instead is the figure’s reflection in the mirror, which features her most private parts in a disturbingly voyeuristic fashion. When she was a child in Ipswich, Kristen often encountered horseshoe crabs while wading by the shore. Now they’ve become quite rare because it turns out that the blood of horseshoe crabs is used to test pharmaceutical products and has become one of the most expensive liquids on the planet. The crabs are drained of most of their blood and then returned to the ocean, but many are so depleted of blood that they die—hence their dwindling population.

There are many metaphors here, and not-quite logical but compelling associations, similar to those we find in poetry. The woman and the horseshoe crab both embody the life force; the woman is sheltered by the horseshoe crab but because the crabs are endangered, she is endangered as well; the mirror at once evokes a medicine cabinet, where we find medicine for

healing; but its cold surface and the invasive view it provides are also threatening. As is the case with the best art, there’s no single message conveyed. We can view the piece in many ways, although surely it evokes the healing power of nature and at once the primal forcefulness and the fragility of human existence.

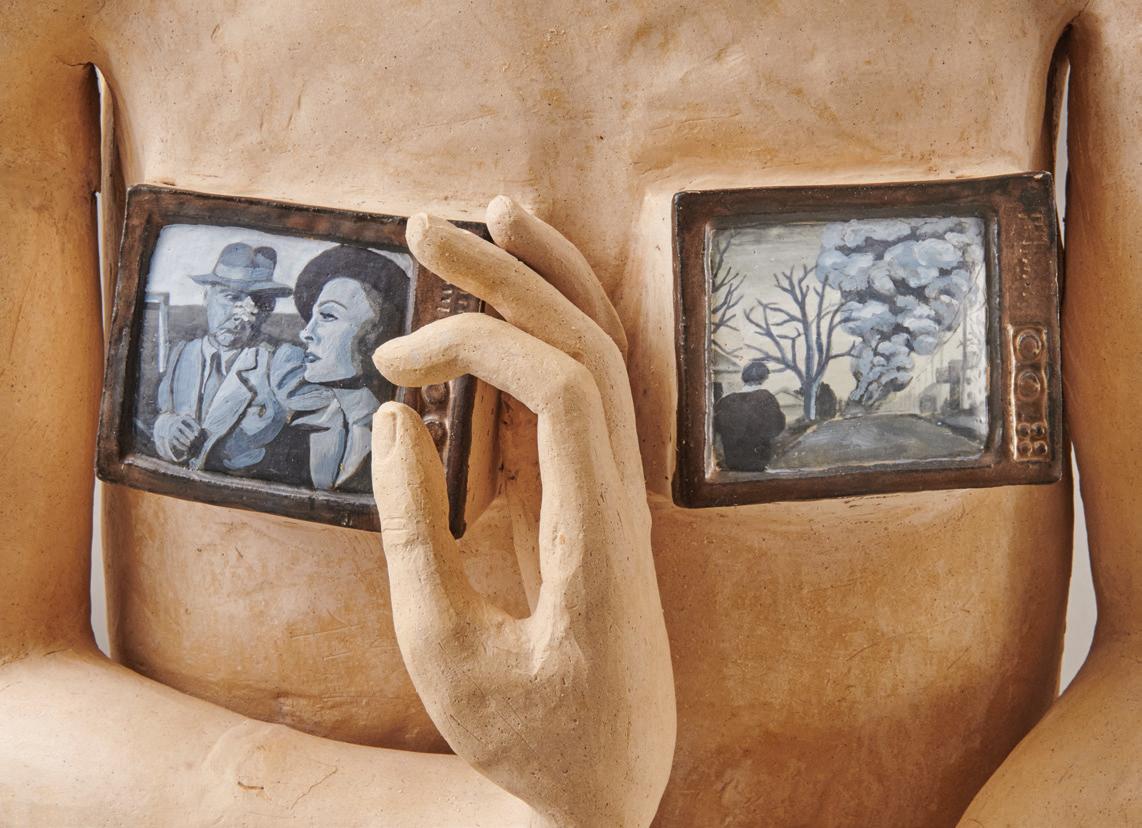

I’ll leave it to the reader to figure out the symbolism of Ken’s Girlfriend’s Neck (2023). Much of the fun of Kristen’s work consists in trying to figure out what it’s saying, and in the process doing something akin to creating a work of art one’s self. Here are a few clues to get started.

“The piece gets its name from the work of Ken Nevadomi, the Cleveland painter, who did chaotic, mysterious, semi-abstract animal, figure and genre paintings. Her breasts are two TVs, one with a scene from Chinatown and the other with an image of East Palestine, where there was recently a train derailment and a chemical spill. The film Chinatown is all about greedy people getting rich from the control of water. It was also the famous director Roman Polanski’s last film before he was charged with raping a thirteen-year-old girl. The woman’s hair is blue and cascades like water.”

Surely there’s something serious going on here—as in the other works in this exhibition, which I will also leave it to the reader to interpret. But to give Kristen a few last words:

“Even though I’m often dealing with death and heavy subjects, it is a joyful process. I get lost in the creation of things. There’s often dancing involved.”

Dancing and death. The two things seem to stand at opposite poles. By the same token, there’s a deep paradox to the feelings Kristen’s work stirs up in me. I’ve mentioned that Kristen’s work often evokes the work of artists from long ago, who are now anonymous, whose work evokes myths and archetypes and connects with the underlying human dream state for which Jung devised the catch-phrase, “The collective unconscious.” For me, Kristen’s work has deep connections with anonymous, almost impersonal work of this sort. Yet paradoxically, at the same time, I’ve encountered few works by an emerging artist that so clearly express a distinctive personal mythology and inner vision, and make such an up-to-date, contemporary artistic statement.

That said, I hope that the viewers of her work will not try to pigeonhole her creations with some sort of historical or art historical label. It’s more important to connect with the free-ranging metaphors in her work, and to lose one’s self in their poetic meanings and associations.

Glazed stoneware and plant

Signed and dated on bottom

14 x 9 x 8 inches

Four Three Two One, 2015

Stoneware, porcelain and acrylic

Signed and dated on bottom 16 x 15 x 14 inches

Friends, 2016

Stoneware, porcelain and gold

Signed and dated on bottom

9 x 7 x 4.5 inches

AmericanSpirit, 2016

Glazed stoneware, gold and acrylic

Signed and dated on bottom

14 x 7 x 7 inches

Grounding, 2018

Glazed stoneware

Signed and dated on bottom

19 x 17 x 6 inches

Alpaca, 2019

Stoneware and glazed porcelain

Signed and dated on bottom

18.75 x 13 x 14 inches

Lamb, 2019

Glazed stoneware

Signed and dated on bottom

17 x 28 x 15 inches

Glazed stoneware, acrylic, epoxy and mirror

Signed and dated on bottom

43 x 16 x 15 inches

BeastsoftheApocalypse, 2019

Glazed stoneware, epoxy and acrylic

Signed and dated on bottom

24 x 28 x 10 inches

Glazed stoneware

Signed and dated on bottom

11.5 x 12 x 12 inches

River, 2020

Glazed stoneware and beeswax

Signed and dated 48 x 25.5 x 19.5 inches

Husk, 2020

Glazed stoneware, epoxy and wood

Signed and dated 95 x 31 x 35 inches

ManDescending, 2020

Glazed stoneware, epoxy and wax

Signed and dated on bottom

29 x 14 x 8 inches

Glazed stoneware and acrylic

Signed and dated on bottom

14 x 12 x 7 inches

In collaboration with Nikki Ilkanich

Glazed stoneware and porcelain

Signed and dated on bottom

15 x 28 x 17 inches

Glazed stoneware

Signed and dated on bottom 18 x 10 x 8 inches

Sanctuary, 2021

Acrylic on matboard

Signed verso

38.5 x 19.5 inches

Glazed stoneware and light fixture

Signed and dated on bottom 10 x 12 x 12 inches

PersephoneAmputated, 2021

Glazed stoneware

Signed and dated on bottom

11 x 16 x 7 inches

Glazed stoneware

Signed and dated on bottom

24 x 15 x 9 inches

Tempering, 2021

Glazed stoneware

Signed and dated on bottom

24 x 12 x 13.5 inches

PersephoneDescending, 2021

Stoneware, epoxy, wax and glaze

Signed and dated on bottom

36 x 10 x 17 inches

Glazed stoneware, epoxy and plant

Signed and dated on bottom

41 x 17 x 10.5 inches

Glazed stoneware

Signed and dated on bottom

35 x 10 x 9 inches

Glazed stoneware

Signed and dated on bottom

9.5 x 7.5 inches

Glazed stoneware and metal leaf

Signed and dated on bottom

15 x 26 x 11 inches, each

Jupiter, 2021

Stoneware and porcelain

Signed and dated on bottom

9 x 8 x 7.5 inches

Glazed stoneware and epoxy

Signed and dated on bottom

21 x 6 x 7 inches

200 Million Years, 2022

Stoneware, glaze and found object

Signed and dated 15 x 28.5 x 18 inches

Exhibited: CAN Triennial 2022

Earthenware

Signed and dated on bottom

11 x 6.5 x 11.5 inches

Enigma, 2022

Stoneware and porcelain

Signed and dated on bottom of head

11 x 5 x 6 inches

Exhibited: CAN Triennial 2022

Rabbit, 2022

Stoneware and porcelain

Signed and dated on bottom

17 x 6 x 10 inches

Vessel, 2022

Ceramic 6 x 6 x 6 inches

Stoneware, porcelain and glaze

Signed and dated on bottom

14 x 14 x 8 inches

Charcuterie, 2023

Glazed stoneware

Signed and dated on bottom

21 x 13 x 4 inches

Bather with Flowers, 2023

Earthenware, stoneware,glaze, epoxy, resin and dried flowers

Signed and dated on bottom

22.5 x 25 x 14 inches

Ken’s Girlfriend’s Neck, 2023

Glazed stoneware and epoxy

Signed and dated on bottom

26 x 17 x 17 inches

EmergentCat, 2023

In collaboration with Clara Wolverton

Stoneware, porcelain, epoxy and acrylic

Signed and dated on front paw

14 x 28 x 12 inches

Glazed stoneware

Signed and dated on bottom 13 x 11 x 4 inches

Stoneware and epoxy

Signed and dated on bottom

30.5 x 28 x 24 inches

Bather with Sandcastles, 2023

Stoneware, epoxy, glaze and wood

Signed and dated on bottom

36 x 24 x 24 inches

Kristen Newell was born in 1989 in a small town on the coast of Massachusetts, where from a very early age, she demonstrated a strong propensity for the arts. Important additional inspiration came from her family and from the family of a childhood friend, where Kristen found herself surrounded by the work of Paul Manship, her friend’s grandfather and one of America’s greatest sculptors.

With increased focus on her art, along with winning numerous awards throughout high school, Newell eagerly enrolled in the arts program at University of Vermont and augmented her studies with a valuable year at the Cleveland Institute of Art.

Upon graduation, Newell moved back to Cleveland to begin her art career and started participating in group shows, including River Gallery and the Ohio State Fair. In 2016, she began an internship at BRICK Ceramic + Design Studio, a well-known hub for Cleveland ceramicists. In 2019, she had her first solo exhibition at BRICK, and has since shown work at Gallery U, Abattoir Gallery, Waterloo Arts and WOLFS.

In the spring of 2021, Newell worked with artist Anna Chapman, creating an immersivethemed show at Waterloo Arts, and in 2022, participated in the CAN Triennial of Northeast Ohio, where a work of hers was purchased by the Cleveland Art Association (Carta).

Today, Newell’s primary medium is clay, creating dimensional sculptures and relief tiles, while continuing to paint and work with mixed media. She recently added the art of creating large-scale parade puppets to her bailiwick. Of late, Newell draws inspiration and perspective from a broad swath of subject matter, including biological systems, philosophy, history, psychology, literature, and architecture. As a process artist, her works unfold as conversation between form and content, playing with scale, color, and material to tell stories and convey feeling. Newell also teaches, working within underserved neighborhoods, offering classes in local artistic spaces, as well as working with individuals to facilitate custom ceramics projects.

WOLFS staff:

Megan Arner

Arianne Flick

Kristen Newell

Dr. Henry Adams, Professor of Art History, Case Western Reserve University

Christopher Richards, Context Fine Art

Josiah Hall, Photographer

Clara Wolverton, Cerulean Conservation, LLC

Larry Sisson, Sisson Fine Art Services

To all those, anonymous and otherwise, who have selflessly contributed to this worthy endeavor – thank you.