We’ve missed you. After returning from quarters abroad (we won’t mention it again, we promise) and being thrown into a harsh, frigid Evanston winter quarter, Wavelength was our only reprieve.

Lucky for you all, our many treks through the snow to meetings in Parkes Hall have produced an issue that has something for everyone’s full range of musical emotions. Whether you’re looking to scream Mo Bamba in a frat basement, scream SZA lyrics in a man’s face or impress no one with a list of artists whose names begin with “baby,” our writers have got you covered.

In this issue, we’ll teach you how to find new music or, if you’re sick of everything out there, start a band and make music of your own, and bring you into conversation with Big Star legend Jody Stephens.

Of course, Wavelength could not be made without our incredible staff. We had so many fresh faces in the room this year, and we appreciate the endless excitement, energy and patience you brought to the magazine. Another big thank you to WNUR for your continued support.

We’ve both been in and dearly loved Wavelength since the beginning of our time at Northwestern, and it’s an honor to take the helm as Editors-in-Chief. This magazine has undoubtedly shaped our time at Northwestern and we are so ecstatic to have the opportunity to shape it back.

This issue is our fun, playful attempt at bringing the whole staff’s diverse ideas off the table and into print. Creating it brought us unbridled joy and comfort — we hope you feel the same way while reading. But enough from us. Here’s Wavelength Volume 7: Organized Chaos.

readers, dear catherine maddy

Sincerely, and

thelineup

Editors-in-chief

Catherine Duncan

Maddy Rubin

Design Editor

Ryan Murphy

Doors

Section Editor

Rosie Newark

Main Act

Section Editor

Jocelyn Mintz

Encore

Section Editor

Lu Poteshman

Assistant Section Editors

Darya Tadlaoui

Ava Levinson

Audrey Hettleman

Copy Editor

Kelly Rappaport

Contributors

Payton DiSario

Andrew Kim

Jack Ding

Jason Boue

Timia Mccoade

Blake Parker

Brooke Fein

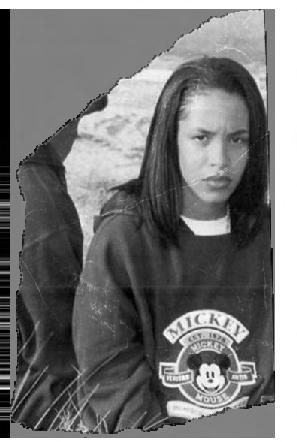

Alex Neuser

Luke Jordan

Annabelle Sole

Eva Putnam

Iris Ingelfinger

Esther Lim

Designers

Annie Xia

Esther Lim

Audrey Hettleman

Alena Baker

Atarah Israel

Doors Main Act

Lineup 06 The beginner’s guide to finding new music 08 Settling the score: Best movie soundtracks 09 The secret concert series for adventure seekers 10 How to start a band 12 Sampling as musical storytelling 13 Staff Playlists 15 A new wave rocks Lil Boat 18 A conversation with Jodie Stephens 22 Feminine rage in popular music 25 The problem with posthumous albums 28 Niteskool is in session 29 Frat bros love Sosa 33 DJs are people, too 34 My Baby Fever 36 Private listening in a public place 37 The Aaliyah I used to know 38 Outside the limelight 40 Pitchfork: Who scored better?

ENCORE

The Beginner’s Guide to Finding New Music

By Blake Parker | Designed By Ryan Murphy

By Blake Parker | Designed By Ryan Murphy

As students, we’re faced with decisions every day: attending or ditching class, prioritizing certain assignments, making our next meal. Music streaming services like Spotify have caught on and devote a large sector of their companies to creating algorithms that eliminate the need to decide.

Excluding your Discover Weekly, Spotify’s personalized playlists don’t provide much new music. Rather, they link your current taste by artist and style to the tracks provided for you. While it’s great to feel your taste is understood, the passive decision to listen to a Phoebe Bridgers album may result in weeks of her melancholic sound permeating the mixes Spotify creates for you. So, we inevitably engage in a universal struggle: How can I find new music?

Browse Spotify Mixes

The more variation you’re searching for, the less you’ll want to rely on Spotify’s personal algorithms. If you’re looking for new artists whose songs have similar moods to your current favorites, Spotify’s suggestions are a great place to start. The “Discover” tab is a center for new artists and records you haven’t heard, based on what you already enjoy.

Personalized playlists can help you find new music based on your current taste, but public playlists made by Spotify are the best tools for finding music beyond your current library. Spotify’s home page features playlists like “Pollen”

and “Lorem,” which are helpful for finding tracks from multiple genres.

Take Recommendations

We’re collectively boxed in by our listening habits on streaming services. Since these listening histories are distinct, we have a lot to gain from trading favorite tracks and artists. Features like “Spotify Blend” allow users to combine their tastes by creating playlists together. Blending with a friend who has a starkly different taste is an efficient way to acquire a new list of tracks to check out.

Explore Artists’ Work

When you find a song you enjoy, listen to the album. If you enjoy an artist’s vocals, songwriting techniques or melodies, exploring their other albums is the best step to finding new music with different forms and feel. Beyoncé recently traded her pop sound for house music in “Renaissance,” and Alvvays ditched their simple indie-pop sound and experimented with a dense shoegaze mix in “Blue Rev.” While both artists created each record themselves, the albums progress through drastically different sound worlds. If you enjoy the instrumentation of the music, start your search by scrolling down midway through the artist’s profile and browsing “fans also like,” where you’ll see a list of artists who make similar music.

Get Creative

Platform extensions like Moodify and Magic Playlist expand on Spotify’s algorithms and automate more playlists for you based on a general mood or a single song. For those looking to branch out entirely, extensions like “Shuffle Spotify” and “Playlist Miner” provide you with an automated playlist or a list of pre-existing playlists on Spotify. These offer greater customization, but won’t consider your listening habits like the previous few.

For those who find new songs out and about, Shazam can be connected to spotify to automatically create a playlist of all the new songs you find working at a cafe or shopping at a mall.

Look Local

Because streaming services are selling products, the music they suggest is influenced by its popularity. This phenomenon can skew your library and leave you to unknowingly neglect a selection of local artists.

To reduce this popularity effect, attend local shows! Supporting a local musician at a concert means so much more to them than the few cents larger artists get when you stream their records. If you don’t have the time or money to go to shows, search for artists playing in the area and check out their work on streaming platforms.

And Finally, Keep an Open Mind

Just like our palette for taste, the ear acclimates to foreign sounds. So if you don’t like a track, ask yourself why and give it another try. There was surely a time when your current favorite artists sounded new to you.

SETTLING

THE SCORE

by Kelly Rappaport

Designed by Atarah Israel

MUSIC IN A FILM CAN MAKE OR BREAK IT; there’s a reason there are four different Oscars categories dedicated to sound. Some music becomes iconic, paired forever with the movie from which it came — think “Don’t You (Forget About Me)” by Simple Minds at the end of The Breakfast Club (1985), or “You’ve Got a Friend in Me” by Randy Newman for Pixar’s Toy Story (1995). Other songs, like “The Shark Theme” from Jaws (1975), are tied to an original score, which is an album of original compositions made specifically to accompany a film. While this list is by no means exhaustive, it contains 7 of some of the best movie soundtracks that come to mind, in no particular order. Honorable mentions who were mostly cut for length include The Royal Tenenbaums (2001), Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009), Forrest Gump (1994), 8 Mile (2002), and The Social Network (2010).

THE

Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse

Between the beautiful original score by Daniel Pemberton and the star-studded soundtrack, it’s hard not to include Spider-Verse in the list. The film opens with the iconic “Sunflower” by Post Malone and Swae Lee, and the choice of artists and genre most certainly reflects the Black culture and comic-like style of the film, as well as its New York City setting. And who can forget the incredible moment when Miles Morales takes his first leap off the building to the heavy thrum of “What’s Up Danger” by Blackway and Black Caviar? If you haven’t seen (or heard) this movie yet, what are you doing?

Baby Driver

How could we possibly leave out the film whose fight choreography and blocking was coordinated to the beat of its soundtrack? Baby’s constant need for music playing in his earbuds means every crime and heist is committed to unexpectedly funky songs like “Egyptian Reggae” by Jonathan Richman & the Modern Lovers, rock classics like “Brighton Rock” by Queen, and old school sounds like “B-A-B-Y” by Carla Thomas. It feels like the music truly drives the action in this movie, so even if you don’t check out the soundtrack, the movie itself is worth a listen.

Juno (2007)

Juno is a cute coming-of-age movie starring Elliott Page, the delightfully awkward Michael Cera, his Arrested Development co-star Jason Bateman, and Jennifer Garner, among others. Its soundtrack is full of equally cute indie songs reminiscent of a high school band, like the indie classic “Anyone Else but You” by The Moldy Peaches. The charmingly clumsy music perfectly reflects the embarrassing and gawky moments of growing up in the film, but there’s a tinge of sweetness that makes it all worth it. Definitely a super nostalgic and underrated soundtrack in my opinion.

Scott Pilgrim Vs. The World

How could we possibly leave out the film whose fight choreography and blocking was coordinated to the beat of its soundtrack? Baby’s constant need for music playing in his earbuds means every crime and heist is committed to unexpectedly funky songs like “Egyptian Reggae” by Jonathan Richman & the Modern Lovers, rock classics like “Brighton Rock” by Queen, and old school sounds like “B-A-B-Y” by Carla Thomas. It feels like the music truly drives the action in this movie, so even if you don’t check out the soundtrack, the movie itself is worth a listen.

“People were really engaging with the artists which is super exciting. We were all sitting on the floor, and it felt so intimate. It felt like we were in relationship with the artists,” first-year Maggie Munday Odom said about attending a Sofar Sounds show in Fulton Market featuring artists Cassius Tae and Andie.

According to Sofar Sounds’ website, in 2009, Raye Offer, the founder of Sofar Sounds, invited a few friends to attentively listen to live music in his house. Since then, Sofar Sounds has become a global enterprise, with the mission to unite and hold space for artists and engaged audiences through close-knit music performances in 400 cities worldwide, including Chicago and Evanston. Audience members are informed of the exact location of the show 36 hours prior, and the artist remains unknown until they take the stage.

“It was fun because there are often times artists where you listen to one song and it’s not like of there other ones, so even once they started singing, you didn’t know what the next song was going to be like,” said first-year Makena Carnahan, who attended a Sofar Sounds concert in the W Hotel, featuring the artists FURY, Danny Cronson, and Liam Taylor.

The artists selected are typically smaller, less well-known local acts from the city the concert is in. Each concert varies in genre; one act typically falls under the category of Hip Hop or Rap, one act is a singer-songwriter, and one is a band. Many alumni of the series go on to do bigger things; past Sofar acts include Billie Eilish, Bastille, and Yebba.

Venues for Sofar Sounds shows in Chicago include both residential and commercial spaces. The W Hotel venue was one of the most surprising aspects of her Sofar experience, Carnahan said.

“Everyone there was in suits, and I was like ‘Are they going to judge us for walking into this fancy hotel and bar,’ but no one did,” she said.

Shows take place in 400 cities worldwide and in Chicago neighborhoods such as Lakeview, Pilsen, and River North, according to the Sofar Sounds website. Discovering new neighborhoods in the city is another perk of going to Sofar Sounds shows, and would be one of her main motivations to attend another, said Odom.

“I’m really excited to not only push myself outside of what I normally listen to but push myself outside of the areas that I normally explore,” said Odom.

How to Start a Band By Ava DesignedLevinson by Alena Baker

Since coming to campus, I’ve witnessed the start of several student bands. Suddenly they’re playing shows, making merch and starring in campus media. But how did it all happen? I was curious about the behind the scenes and the ups and downs of the making of a student band, so I sat down with Safety Scissors — third-year guitarist Judy Lawrence, third-year lead singer Maddie Farr, third-year bass guitarist Hope McKnight and second-year drummer Anika Wilsnack.

How did you find each other?

Maddie and Hope met and became friends through living in Sargent Hall freshman year. They started Safety Scissors together, and eventually put posters up around the school for new members.

Judy: Yeah, it was around a year ago that I responded to the flier.

Maddie: The vibes were pretty immediately good. To be quite honest, not that many people responded to us. But it was pretty perfect.

Judy: Beggars can’t be choosers.

Maddie: But there is a shortage of drummers and of drum sets and places to practice. Even people who were interested, I’d be like, “Great, can we come to you? Do you have a set you can play on?” And the answer would be, “No.” So we played with several drummers before we just recently met Anika, and she’s the very newest member. We’re excited to have her.

Anika: A lot of times, I feel like the first rehearsal is really stressful, trying to assess the vibe and how you fit into a band’s dynamics. But I got there the first day and everything just fell into place.

Who writes your music?

Judy: Maddie will write the song, like the lyrics. But then Hope will write her bass part and I’ll write my guitar part. In the beginning it was not that way.

Maddie: It’s become more of a collaborative thing, and Hope writes lyrics now too, which actually is one of my favorite things about the band we’ve become. I didn’t want it to be like, “Maddie and the Safety Scissors.” I hate that, and that’s not what it is.

Judy: I think the closer we got and the more we got to know each other, we just naturally were able to be like, “Oh, what if we do this? How about this?”

Maddie: I think a lot of the songwriting that goes on happens outside of formal band practice when we’re hanging out as friends and we’re just messing around.

Do you ever get into disagreements?

Maddie: I kind of think we need more drama.

Hope: We do. Something needs to happen.

Judy: No, I don’t want any drama! It is a hard thing to be honest with each other and know that things are never coming from a negative place while keeping the band’s best interest in mind. Like when you’re writing music… It’s hard.

Maddie: I think the thing we argue about most is putting together a set list.

Hope: I think we have more constructive conversations. We’ll discuss it in depth and I think that’s good for us.

What has been the biggest challenge in starting a band?

Maddie: Finding a place to practice.*

*Editor’s note: We sat outside for the first 15 minutes of this interview, because the band members had to hope a student would walk into the music sorority and scan them in. Once we were inside, we had to wait for another student to let us into the basement.

Judy: Bienen doesn’t let non-Bienen students practice there. It’s really restricted.

Maddie: We even reached out to Bienen and sent an email saying who we were, and they emailed back and it was, “No.” They don’t care.

Judy: You’d think they’d want students to do things.

Where do you get your inspiration?

Maddie: When I’m writing, I draw a lot of inspiration from the music I grew up listening to, which was what my dad listened to. So a lot of dad rock, to be honest. But I also went through this huge emo phase, so I think a lot of the melodic stuff as well comes from bands like Fall Out Boy, Blink-182, My Chemical Romance and that whole scene, which is a little embarrassing to say. Sometimes when we’re writing lyrics, it’s about personal experiences and sometimes we’re just writing lyrics because we think they sound cool.

What’s the story behind the name of the band?

Maddie: We’re all queer women, which I think is really special and unique. All our lyrics are really personal to us, and so they’re often about girls and women. A lot of times, those are shared experiences with all members of the band, and I think with other queer people. But also I think a lot of bands in the world are a whole bunch of dudes, so I think the fact that our band is exclusively queer women is cool – not that we intended that.

Hope: We didn’t write on the flier, “You have to be gay.”

Judy: When we were looking for a drummer, so many people were like, “I know somebody who plays drums, but they’re not lesbian.” We were like, “Uh, they don’t have to be.” But it is cool, especially in a male dominated [field]. It’s fun to do covers of dad rock band songs like “Jessie’s Girl” and “Stacy’s mom.” Suddenly when we’re singing them, it just feels better. So much more interesting, are you kidding?

BY ROSIE NEWMARK

DESIGNED BY ANNIE XIA

Although musical artists strive for creativity and originality, every artist uses musical influences as inspiration for their songs and albums. It’s in the nature of music; the industry would not progress without help from other artists’ work.

Whether it’s the opening guitar riff in “Last Nite” by The Strokes based off of (or ripping off) the intro to “American Girl” by Tom Petty, or Vanilla Ice using parts of Queen and David Bowie’s “Under Pressure” on his track “Ice Ice Baby” without permission, artists often use the melodies and lyrics of those before them to enhance the quality of their own music.

This is a part of the idea of sampling, a process in which an artist gets the copyright to borrow a musical element from another artist’s work, whether that be a melody, conversation or monologue to enhance their own. Sampling has become an important tool for preserving and celebrating cultural heritage. By sampling traditional music from different parts of the world, musicians can incorporate diverse sounds into their work and introduce audiences to new cultural traditions. Sampling is especially popular in the hip-hop community in a variety of mediums. The music of Ms. Lauryn Hill, an influential singer-songwriter and rapper, is widely sampled by hip-hop artists, featured in songs by Kanye West, A$AP Rocky and Drake, among others.

Artists also often sample conversations or monologues within their songs.

“Temptations” by Joey Bada$$ comes to mind, where he samples a speech by a young Black girl expressing frustration with the racism and discrimination she often experiences. Sampling politicians’ speeches’ is also popular in hip-hop and numerous other genres — on “No Role Modelz,” J. Cole famously samples former President George W. Bush botching the phrase “Fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me” during a speech.

While some people think sampling is a creative act, others argue that it lacks creativity because the artists are using sounds that have already been created

Perhaps because of this controversy, some artists instead use interpolations to honor another artist by taking part of an existing work and revamping it to make it their own. A recent song that utilizes this tactic is “Flowers” by Miley Cyrus, which interpolates the structure of “When I Was Your Man” by Bruno Mars (allegedly as an attempt to diss her ex-boyfriend Liam Hemsworth, who once dedicated Mars’ song to Miley).

Sampling is a unique form of storytelling that can also be used to pay homage to music of the past. By sampling classic songs or sounds from different eras, musicians can create a connection between past and present and introduce new audiences to music that may have otherwise been forgotten.

STAFF PLAYLISTS STAFF PLAYLISTS

Songs we’re pissed got popular on TikTok:

Space Song - Beach House

Homage - Mild High Club

Sparky Deathcap - September

Mariners Apartment Complex - Lana Del Rey

Freaks - Surf Curse

Where’d All the Time Go? - Dr. Dog

Evergreen - Omar Apollo

Right Down the Line - Gerry Rafferty

Little Dark Age - MGMT

Mary - Alex G

Best Duets:

Don’t Go Breaking My Heart - Elton John & Kiki Dee

My Boo - Usher & Alicia Keys

My Favorite Part - Mac Miller feat. Ariana

Grande

Nothing Even Matters - Lauryn Hill feat.

D’Angelo

Summer Bummer - Lana Del Rey feat. A$AP

Rocky

Girl - The Internet feat. KAYTRANADA

Save Your Tears - The Weeknd feat. Ariana

Grande

drive ME crazy! - Lil Yachty

Our House - Graham Nash & Joni Mitchell

Songs that remind us of our childhood:

Upside Down - Jack Johnson

8 Days a Week - The Beatles

Landslide - Fleetwood Mac

Waterloo - ABBA

Yellow - Coldplay

Drops of Jupiter - Train

Jessie’s Girl - Rick Springfield

Me and Julio Down By the SchoolyardPaul Simon

Waitin’ on a Sunny Day - Bruce Springsteen

Mona Lisas and Mad Matters -

Elton John

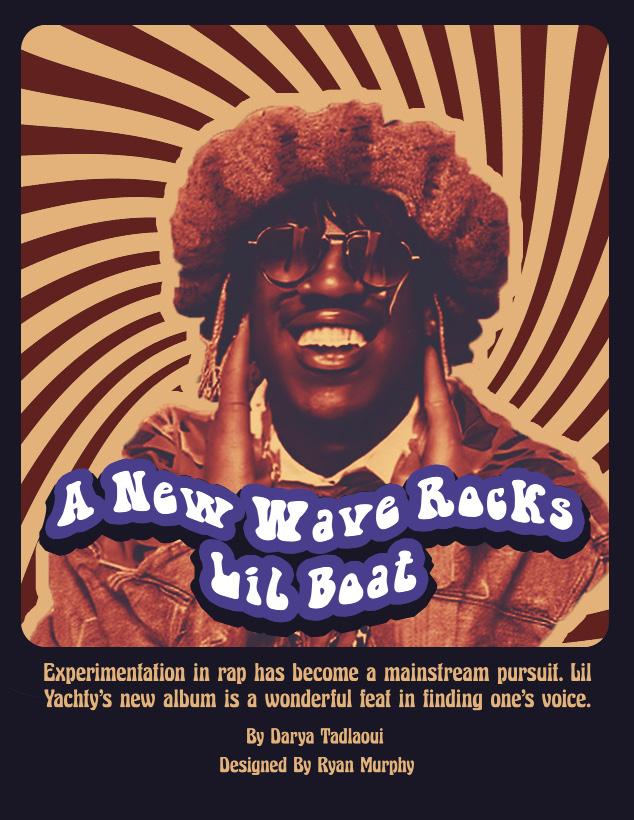

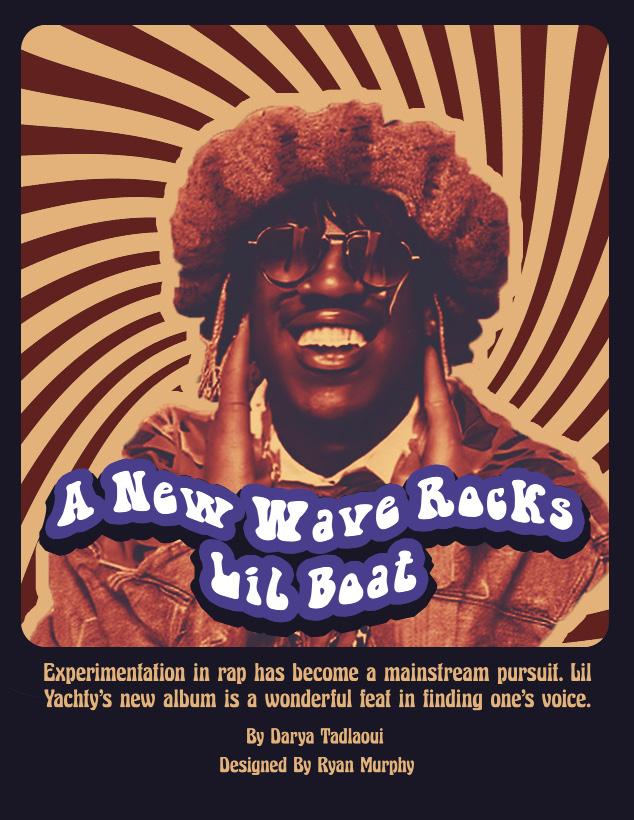

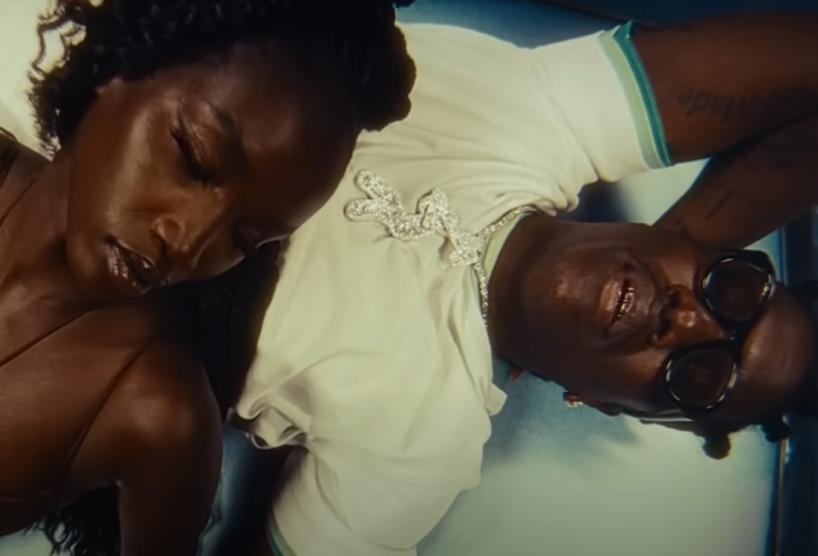

Hitting shuffle play on my Spotify Release Radar, I walked to class with a blissfully psychedelic tune blasting in my AirPods.

This new Tame Impala song is really good.

Turns out I was actually listening to “drive ME crazy!” — the eighth track off of Lil Yachty’s newest album, Let’s Start Here.

Just a year after putting out a single in his iconic “candy rap” style, the Atlanta-based artist surprised fans and critics with the release of a refreshing indie rock collection, becoming the latest in a growing trend of rappers branching out from traditional hip-hop and redefining their sound.

Yachty — Miles Parks McCollum off-stage — has long remained a symbol of the 2016 explosion in SoundCloud mumble rap; his songs are off-kilter and almost comical, emulating a childlike melodic simplicity. Oftentimes, McCollum crafts his tracks in conjunction with skits, such as “1 Night,” the nursery-rhyme-adjacent tune that arguably put him on the map, and “iSpy,” his collaboration with backpack rapper KYLE. His young age – he entered the public sphere at just 19 – combined with his signature bright red hair, rainbow-colored grillz and high register cemented McCollum as a juvenile, larger-than-life, decidedly not self-serious character.

Outside of his music, too, McCollum has maintained his eccentric persona in a hodge-podge of acting credits — he voice-starred in Teen Titans Go! To the Movies, acted in drama On the Come Up and teamed up with LeBron James in an iconic Sprite commercial. McCollum’s portfolio is as expansive as it is, well, bizarre.

The artist’s offbeat character and untraditional career have a larger context in his outspoken indifference to rap legends from the “golden age” of the ‘90s. In an interview with Billboard, McCollum admitted he “honestly couldn’t name five songs” by trailblazers 2Pac or The Notorious B.I.G; in an interview with Pitchfork months later, he went so far as to call Biggie “overrated.” As the self-proclaimed “King of Teens,” he’s received a litany of criticism from industry giants like Joe Budden and Anderson .Paak, who claim he lacks respect for the rich hip-hop culture that shaped his artistry. It seems an entire community had dubbed McCollum a mumble rapper whose warbled verses are blasphemous to the genre.

Perhaps, then, his decisive shift away from rap in Let’s Start Here. is a response to “old-heads” who wouldn’t or couldn’t take him seriously as an artist. Or perhaps it’s merely keeping in line with his inclination to break from tradition and shamelessly represent a generation untethered to the wellestablished. Regardless, as he revealed to friends and fans gathered at The Liberty Center in Jersey City for a listening party the night before the album’s release, McCollum wants to prove he’s “not just some SoundCloud rapper, not some mumble rapper. Not some guy that just made one hit.”

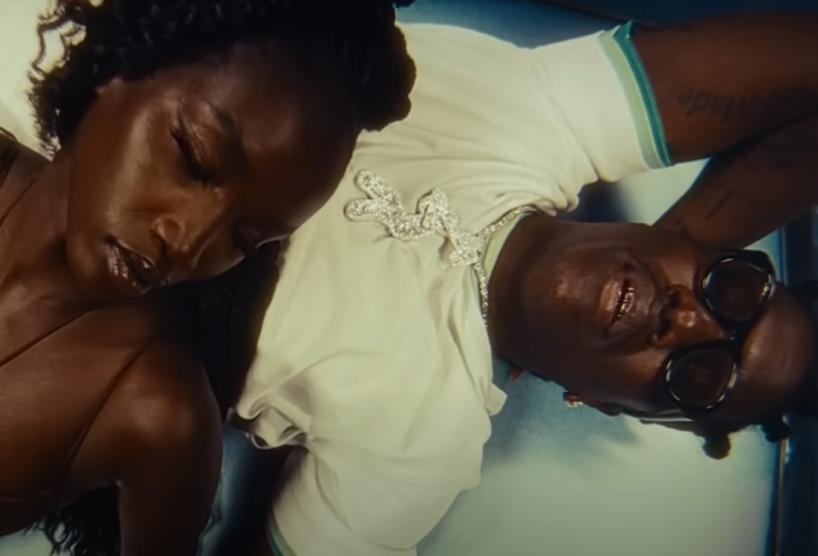

Let’s Start Here. is a far cry from his previous work and simultaneously an extension of his distinct, familiar sound. Boasting writing and production from alternative legends Mac DeMarco, Alex G and Benjamin Goldwasser of MGMT, among others, and features from R&B artists like Daniel Caesar, Justine Skye, Fousheé and Diana Gordon, it emulates a quasiindie, quasi-psychedelic rock feel. Synth chords and heavy-

handed drum solos course through the album, interrupted by the occasional Pink Floyd-esque scream sequence — “the BLACK seminole” is even rumored to sample the band’s “One of These Days.” Each track flows seamlessly into the next, so that the album feels like a bite-sized listening experience. By the end, McCollum has told the story of his journey to enlightenment — to “the sun,” the album’s primary thematic element.

On Lets Start Here., McCollum wrestles with love, vulnerability and belonging, an apparent foray into poetic lyricism that starkly contrasts his previous work. In the album’s self-titled track, the same artist who rapped about smuggling cough syrup into the country on his 2022 track “Poland” delivers a monologue on failure: “failure to me isn’t, like, always a negative thing, but more so…just a way to relook at things. You know, you never know how close you are to success.” McCollum’s crooning, impressive attempts at falsetto are complemented by beautiful production, thanks to the album’s diverse cast of collaborators.

Critics have (mostly) agreed. GQ lauds McCollum’s coproduction credits on every track and has christened it “his first great album.” Rolling Stone echoes this praise: “the quality that once made it hard for detractors to take him seriously has become Lil Yachty’s greatest strength,” it contends.

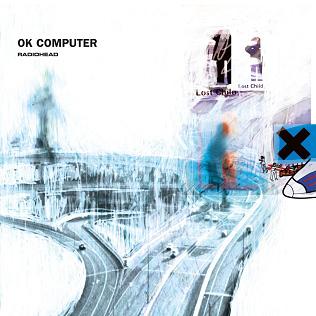

Other major outlets seemed to take the album less seriously than perhaps McCollum hoped for. Vulture bluntly calls it a journey back in time, into space and “sometimes up its own ass.” Pitchfork somewhat agrees, characterizing the album as a tired attempt at an already-mastered genre that “badly wants to be hanging up on those dorm room walls with Currents and Blonde and Igor.”

These critics’ main gripe with the album is its apparent lack of novelty — Pitchfork claims it “doesn’t feel experimental at all.” But does it have to be? Sure, McCollum isn’t breaking boundaries within the expansive alternative genre in which almost everything once considered “experimental” has become mainstream. But he certainly ventures far beyond the sickly sweet “candy-rap” he was known for and does so in a way that feels genuine and well-researched. McCollum clearly did not round up such acclaimed collaborators overnight, nor did he learn to produce so seamlessly from halfhearted observation. To me, the album is as meaningful

as it is groovy and delightful. It’s the perfect accompaniment to a warm day — maybe even the soundtrack of my summer.

My affinity for the album isn’t based on any internal bias I have toward McCollum — in fact, I’ve never particularly been a fan of his music for anything other than evoking a sense of nostalgia for 2016. Meanwhile, I’ve been a fan of Kid Cudi for years — I spent my life savings on front-row seats for his To The Moon tour last summer. But even I have the capacity to admit Speeding Bullet 2 Heaven, a similar rap-to-rock transitional album as Let’s Start Here, was a massive failure.

Kid Cudi, or Scott Mescudi, has found an unfulfilled niche within the larger hip-hop genre and, for the most part, stuck to it. He’s redefined melodic rap, in many ways contributing to its invention; he infuses his raps with upbeat electric guitar solos — think “Erase Me” or “love.” — and litters his verses with drawn-out hums. His Man on the Moon trilogy is as lyrically complex as it is a source of crowd-pleasers; Mescudi’s lines are raw and honest, depicting feelings of loneliness, paranoia and insecurity against a backdrop of synthetic, reverberative beats. He has pioneered the industry in this way, paving the way for artists like Trippie Redd and Joey Bada$$ — and now, it seems, Lil Yachty — to experiment with their raps and bare their hearts to their fans.

In part, I think McCollum’s voice is simply better suited to work within alternative genres. Rappers like Mescudi also use heavy autotune in their alternative projects, but McCollum’s silvery, sotto voice and high range give his album a truly psychedelic feel, while others’ deep monotone registers limit their artistic expression and creative license. Though McCollum doesn’t rap on Let’s Start Here., his voice is recognizable, cloaked in the same vibrato that he brings to songs like “Poland.”

And yet his attempt at entering the world of rock with Speeding Bullet 2 Heaven was, by most accounts, a colossal faceplant. So bad, in fact, that Pitchfork’s 4.0 review of the album opened with “Is Kid Cudi serious?”

Released at a time when fans were expecting the final leg of Man on the Moon, it’s possible that reception was so poor because of this disappointment and growing impatience. Or maybe it is just that bad. The album blends together into one unhinged, Nirvana-wannabe lament of life, depression, mania and trauma, to the point where every song sounds the same — unstructured, comically simple, the unending repetition of guitar chords and choruses like “everything, everyone sucks,” almost an incantation. And all of this is interrupted by “Beavis and Butthead” skits provided by Mike Judge, the show’s creator.

It is clear Mescudi is struggling in this album. And yet it somehow feels simultaneously self-indulgent and ironic. It’s hard to take Mescudi’s grief seriously when it is cut short by Butthead telling Beavis to “take some of these mushrooms that Cudi gave us.” Maybe we are supposed to feel the delirium he does, but it mostly has the effect of making listeners want to turn his music off.

And Mescudi is not the only rapper to have ventured outside of the confines of the genre and failed. Lil’ Wayne’s rock album Rebirth was largely denounced as “unqualified,” a project that only die-hard fans could appreciate. Supermarket, Logic’s attempted emulation of artists like Thom Yorke and the Red Hot Chili Peppers — featuring a cover of A Tribe Called Quest’s “Can I Kick It” that Pitchfork calls “soulless” — similarly fell flat.

The failure of scores of rappers before him begs the question: what did McCollum do differently? How did McCollum’s rap-to-rock transition find a receptive audience?

But more than that, McCollum carefully distills his eccentricity to work to his advantage. He is not afraid to push boundaries, but he’s not gratuitous in this experimentation either. His apprenticeship with a variety of indie and R&B masters equips him with the tools he needs to be successful in such an ambitious undertaking. McCollum’s album tells a story; there is a clear narrative at play, a rise and fall the listener can follow, and while there are experimental elements at play – a sequence of heavy breathing and footsteps, a monologue from Bob Ross — they are grounded in the plot structure and feel intentional. Rappers before McCollum with experimental failures largely did not attempt to situate their tracks within a larger context; Mescudi, for example, jumps erratically from topic to topic on each song, inputting attempts at experimentation seemingly on a whim. McCollum’s work might be “institutional,” but it follows the general rules of music-making while still maintaining the rapper’s authenticity.

This is not to say that McCollum is the only rapper who has “done experimentation right.” Drake’s recent refreshing exploration of house music in Honestly, Nevermind comes to mind, as does Tyler, the Creator’s gradual shift away from the hard rap of Odd Future Wolf Gang Kill Them All, better known as Odd Future, and decisive break toward the alternative world in the heartfelt masterpiece of IGOR. Mac Miller’s jazzy, soulful The Divine Feminine and mellow ballads on Circles are hailed as some of his finest work even as they lose the angsty rap of the Pittsburgh artist’s high school passion project, K.I.D.S.

As the golden age of hip-hop becomes ever-farther away; as we move temporally and spatially toward inclusivity, maximalism and versatility; as more and more people refuse to be boxed in and defined in one way or another, artists have the freedom to reinvent themselves to the delight of a more accepting audience. This phenomenon perhaps could only have arisen alongside Gen Z’s own maturation as young artists like McCollum continue to grow up and find their footing.

At the time of writing, McCollum has released another single, “Strike (Holster),” in which he appears to have transposed his new sound on a more traditionally hip-hop beat, marrying the melodies of his rock idols with the music that has defined his persona for so many years. It is a wonderful juxtaposition, yet another stride made in the endless artistic pursuit of finding one’s voice.

“On Lets Start Here., McCollum wrestles with love, vulnerability and belonging, an apparent foray into poetic lyricism that starkly contrasts his previous work.”

The drummer said:

A

conversation with

JO Dy sTePHEnS

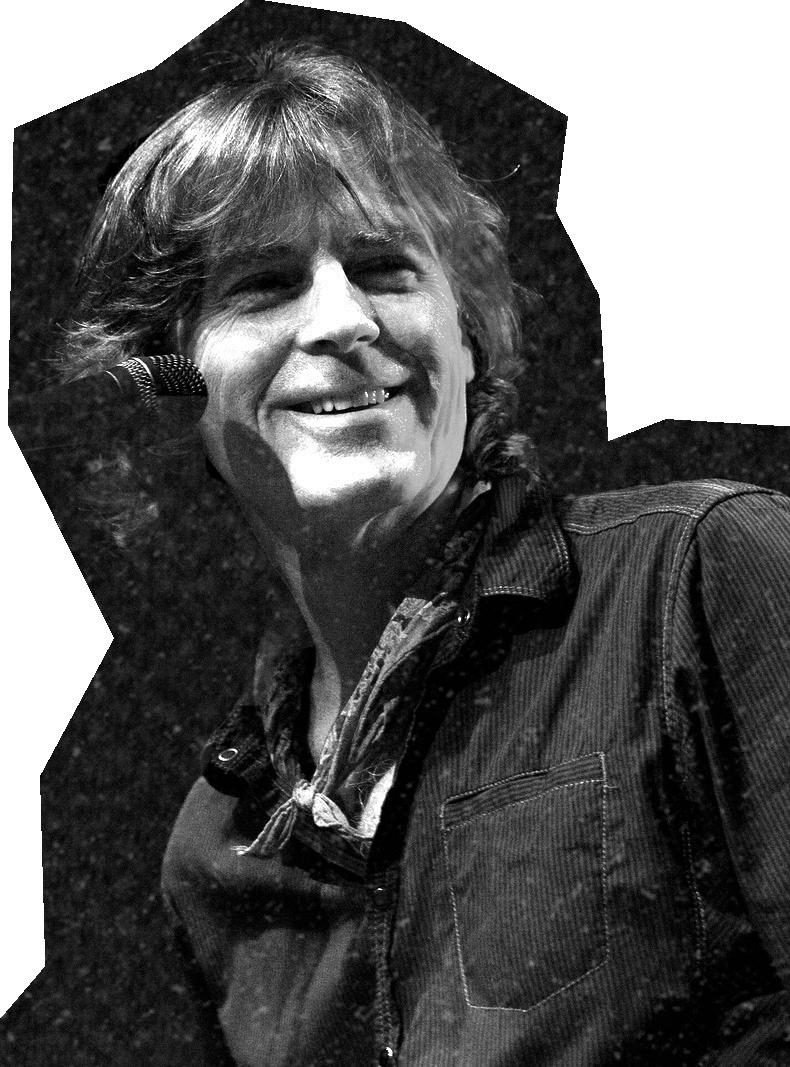

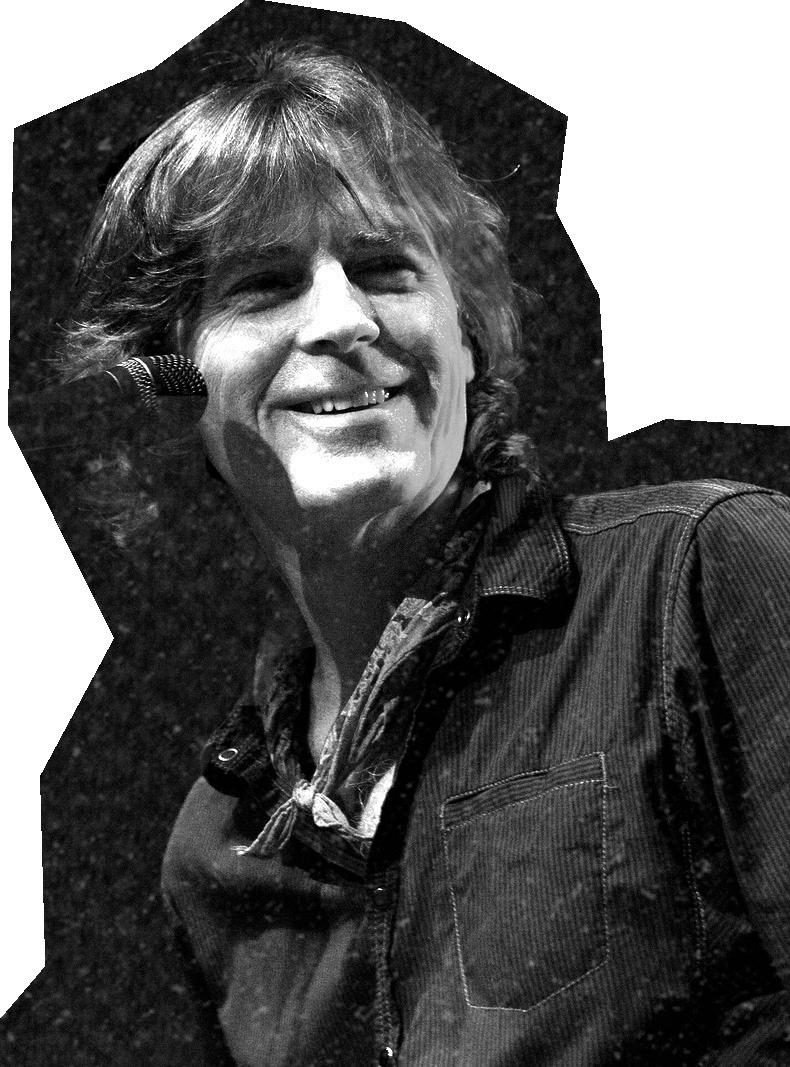

By Zeki Hirsch

Iwas nine when I first heard Big Star. My dad played their acoustic opus, “Thirteen,” on guitar for me. I didn’t like it. Adolescence changed emotions and tastes, and Big Star became a high school favorite. Maybe I was maturing; maybe I just needed another defunct band to hyperfixate on. Big Star has since provided a personal soundtrack for everything from breakups to hangovers. Fifty years after their conception, drummer Jody Stephens is Big Star’s only surviving founder. He’s too humble to admit it, but his drumming formed the backbone for a band whose influence spans from Wilco to Dean Blunt. I was lucky enough to speak with Stephens by phone — doing my best not to fanboy too hard — and publish our conversation. We’ll get to that later, but first, some context.

Big Star was formed in 1971 by four young visionaries in Memphis, Tennessee. On vocals and guitar was Alex Chilton, who recorded a chart-topping hit at 16 — the Box Tops’ 1967 “The Letter” — that propelled him into stardom and spat him back into reality just as quickly. Now 21, Chilton’s premature misanthropy was already seeping into his songwriting. Sharing vocals and guitar was Chris Bell, whose infatuation with the Beatles and Led Zeppelin guided Big Star’s early sound. Resident heartthrob Andy Hummel took on bass, backing vocals, and dabbled in songwriting. Jody Stephens rounded out the lineup on drums,

also contributing backing vocals and some songwriting.

Big Star’s three albums were all recorded at Ardent Studios and produced by the band’s champion, John Fry. 1972’s “#1 Record” combines the Byrds’ cosmic folk harmonies; Beatlesy pop structures; and flirtations with Zeppelin-esque cock rock into a genre now called power pop. Critics gushed over “#1 Record,” but distribution issues with Ardent’s label quashed any commercial momentum beyond scant airplay. 1974’s “Radio City” reimagined the band as a three-piece after Bell quit. It’s still poppy as hell, but captivatingly venomous in a way “#1 Record” isn’t. “Radio City” also flopped, and Big Star dwindled to Chilton and Stephens. The duo’s swan song, Third, follows Chilton into a vortex of downers, alcohol, and toxic relationships. Pop vignettes degenerate into bleak soundscapes, culminating in the gut-wrenching “Holocaust.” Stephens’ dedication is unwavering on Third, but when recording ended, Big Star ended too.

By 1976, Alex Chilton had rejected power pop and fled to New York’s emerging punk scene. Chris Bell, once profoundly tortured, found solace in Christianity and kept making music until a tragic car accident killed him in 1978. His solo oeuvre, posthumously released in 1992 as I Am the Cosmos, picks up where “#1 Record” left off. Andy Hummel ditched music altogether, instead finishing college and working for Lockheed Martin. Jody Stephens ended up somewhere in between, waiting tables, meeting his soulmate, and eventually returning to Ardent full-time in 1987. He often describes his musical aspirations as a “pie in the sky,” but he never abandoned them.

In the 80s, Big Star’s bad luck ended. Thanks to a persistent cult fanbase, they were suddenly inescapable — superstars like R.E.M. and the Bangles and underground favorites like Game Theory and the Replacements crafted Big Star-inspired power pop and cited the band in interviews. Psych-folk pioneer Robyn Hitchcock summarized Big Star’s journey best: “a letter posted in 1971 that arrived in 1985.”

Big Star’s unlikely renaissance transformed their discography from ‘70s footnotes to the proto-alternative Holy Trinity. In the ‘90s, their legacy endured through Elliott Smith and Teenage Fanclub, and Big Star itself reunited in 1993. Chilton and Stephens were the only original members (accompanied by the Posies’ Jon Auer and Ken Stringfellow), but they finally filled concert halls and absorbed the love they’d so long been denied.

Chilton remained apathetic: “People say Big Star made some of the best rock ’n’ roll albums ever. And I say they’re wrong,” he kvetched in 1992. Nevertheless, Chilton led Big Star until his death in 2010. Hummel’s passing a few months later made Jody Stephens the band’s final torchbearer. In 2022, he toured for “#1 Record’s” 50th anniversary with some old friends: R.E.M.’s Mike Mills, Wilco’s Pat Sansone, Chris Stamey of the dB’s and Jon Auer. His new group, Those Pretty Wrongs, just released their third album: “Holiday Camp.” I spoke with Stephens about all of it.

Designed by Esther Lim

Zeki Hirsch : How has it felt touring for Big Star’s 50th?

Jody Stephens: There’s a certain set of emotions that come with just playing music, and that’s the kind of pursuit of happiness of the five members of the quintet. It’s also a pursuit of playing this music that we all really love and appreciate. It’s giving life to music created by Alex and Chris and Andy. It can be pretty heavy emotionally, both with us and audience members, but at the end of the day it’s been a real joy.

ZH: It’s been a long, rough road for Big Star from 1972 to 2023. Were there any particular moments on tour where you felt some of that bittersweetness?

JS: No. It was just a good time! We have a great appreciation of our relationships with each other, so there’s none of those feelings related to anything that far in the past with Big Star. Big Star did a tiny bit of touring, if you can call it that. We played Max’s Kansas City a couple of times in New York City. The first time, Andy was still in the band, and we swapped sets with Ed Begley Jr. We went back after Andy had left and played a few nights with John Lightman on bass. Big Star never rehearsed much, so that’s probably the only discomfort I felt. I just love to sit down with material and go over and over it until, when we hit the stage, we can just experience the song instead of having to think about the performance. You can relate and respond better to the other musicians on stage with the bearings that come from rehearsal. It’s not to say there haven’t been moments with the quintet. I know in Memphis it was “O My Soul.” At some point, we just stopped because I think we were all lost. We laughed it off, it wasn’t a big deal, and the audience thought it was funny. I just counted off again and we launched back into it.

I guess the bad thing about rehearsing along with the record is, my cues are musical cues from Alex, or something Andy does, or a lyric. I don’t count measures; it’s all musical signposts. Sometimes in a live performance, you may not get that, and it can throw you off a bit. In the 70s, if I made a mistake, I would’ve been really uncomfortable with it. But now I’m just having fun, and I’m comfortable enough with the song that most of the time, nobody hears the mistake but me.

ZH: Are there any plans for a 50th anniversary celebration for “Radio City?”

JS: We’re thinking about it! There’s a pretty grand plan afloat. I think “Radio City” came out in January of ‘74, so performing towards the tail end of next year is close enough. It’s funny, anniversaries become reasons to do a performance, but I think we can fudge it a little bit.

ZH: College students generally listen to the poppiest stuff possible, but a surprisingly large amount of people

know Big Star. I’m curious to know why you might think your music continues to resonate with young people fifty years after it was recorded.

JS: It was created by young people. Those little musical nuances and lyrics all express a certain period in everybody’s lives. Whatever melancholy emotions are in Alex’s voice, or edge to his or Chris’ guitar performances, I think lots of people can relate to. Certain things come and go, but emotions kind of stay the same. That’s what it is for me, that and the connection to their voices and guitar parts. Chris and Alex were brilliant at guitar tones and sounds. Together, they could orchestrate performances where they weren’t doing the same thing on the same kind of guitar. A lot of music, you have three guitars playing the same line, and there’s very little arrangement. But with Big Star, there was always an orchestration and an independence of parts that created a pretty cohesive sound picture.

ZH: What do you think is the best starting point for a 20-year-old student who’s never listened to Big Star?

JS: “The Ballad of El Goodo.” There’s a wide range of emotions and feelings, so that would be like a little piece out of the whole picture.

ZH: What do you think is your best moment as a band?

JS: Ooh… There is no best moment. It would be like looking at a Van Gogh painting, like Starry Night. It would be like taking a slice out of that painting and saying “this is the best moment.” It’s just kind of impossible, because in order for it to have any impact, you have to see the whole painting. There’s a beginning, a middle, and an end to Big Star; beginning with “#1 Record”, the middle “Radio City.” There’s a bit of innocence with #1 Record and a bit of sophistication with Radio City, and maybe a bit of cynicism, but expressed in a pretty beautiful way. Each one of those shows a different side of the band, and you really need to know all three to understand who we were and our life cycle.

ZH: What’s your desert island album?

JS: “Sweet Baby James” by James Taylor. There’s something settling and comforting about his voice to me. It’s not loaded down with drama. It’s more of a lilting, sweet, almost reassuring kind of voice. If you’re stuck on a desert island, you need something reassuring for sure.

ZH: Moving on to more recently, what music have you been listening to lately?

JS: I love the Lemon Twigs. I actually sat in with them on a song for one of their records. I was just listening to “Phantom Limb” by the Shins. That song is like crack to me. If I want to get inspired, I’d listen to that, because it opens some sort of creative portal. It’s just one of those things you really can’t explain.

ZH: Talk to me about recording the new single for Those Pretty Wrongs, “Always the Rainbow” and what else you have in store for the upcoming album.

JS: The album is called “Holiday Camp.” Our first single was called “Paper Cup.” We’re just releasing our second single, “Always the Rainbow,” where Pat Sansone joins us on Moog synthesizer. It’s a stunning part! God, he manages to strike up an emotional march of some sort with that thing, and he does it as well with another song called “Scream.” He creates this backdrop that’s just so eerie, but beautifully so.

When the pandemic hit, Luther said: “Hey, we should be productive during this time.” We’ve always written long-distance where I would record lyrics and a melody line and send it to Luther, and then he’d write the music and arrange it. From time to time, I’d need a lyric here and there, and he would come up with those. Then he would massage the melody a little, but we work back and forth. I think we’re perfect complements for each other. We can come up with ideas, share them, and then we can go away and let those things mull around in our minds, and something pops up eventually. I think it’s a killer way to write.

ZH: One of my favorite parts of “Radio City” is William Eggleston’s cover, The Red Ceiling. I have to spend a lot of time with it to get any semblance of an interpretation. What’s your personal interpretation of the Red Ceiling and how do you see it connecting to the music on “Radio City?”

JS: It’s a holocaust. It just seems desolate, barren, and burned out. That lightbulb looks like it’s burned out to me. If you want to relate that to life, it would be a desolate life. The photo can express what we can’t, and it’s not a happy thought. Alex was going through Bill’s pictures and [found The Red Ceiling] before the MoMA bought it. I asked Bill if I could buy a copy, and he said “I’m glad to give you one. Just pay the cost of the print.” He used dye transfer to get those rich colors, and said it cost him 250 dollars a print. This is late 1972 or early ‘73, and I was living pretty frugally. I couldn’t afford the 250 for the front and back. Now, dye transfer copies are like fifty to sixty thousand dollars each.

Bill also took the back cover and some other photos. The back cover was taken in TGI Friday’s in Overton Square, where all the baby boomers gathered on the weekends after they lowered the drinking age to 18. That was at a rock ‘n’ roll night. We were just kind of walking through, and Bill was taking pictures, so we all turned and looked at the camera and did silly things. There was no shortage of really good photographers around. My favorite is one by Michael O’Brien where John Fry’s holding a light to light us up. There’s something about that photo that’s so relative to his part in the creation of Big Star’s records and music. As an engineer, he certainly made it sparkle and shine.

“Radio City” is probably my favorite drum sound. I bought a new kit, which was the first oversized kit Ludwig put together. I had this new supraphonic snare, bigger toms, and a 24-inch bass drum. The way John captured it in things like “Life is White” and “Back of a Car,” with Alex’s guitar sound, damn. And Andy Hummel’s bass parts – he’s such a unique player and steps out of just providing a low-end foundation to providing a bit of energy and movement and feel. He made my job easier.

ZH: A lot of people — particularly John Fry — felt Chris’ presence very heavily in their lives after he died. How have you felt Chris’ presence in the years since his passing?

JS: Oh, Chris is always around. As we play “#1 Record” live, we also play some of Chris’ songs, “I Got Kinda Lost” and “There Was a Light.” We do “Fight at the Table,” too. In the studio, I have Chris’ acoustic Yamaha guitar. We use that on Those Pretty

Wrongs’ records, and we also use Chris’ Gibson ES-330. Luther plugged it into a Marshall and said “God, it just kinda plays itself and it determines what it’s gonna be.” I can see that, because even when you first pick up a set of drumsticks and sit down at a drum kit, you’re informed by the way it sounds. So, two of Chris’ guitars are present. Chris is always around.

RAGE (PATRIARCHAL)AGAINST

FEMININE RAGE IN

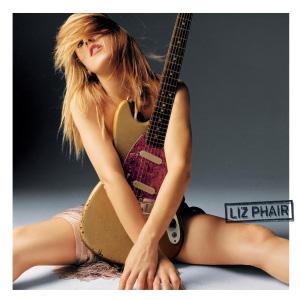

By Audrey Hettleman

Designed by Audrey Hettleman

It is difficult to find a succinct definition of feminine rage online. Perhaps that is because it’s a feeling that one can scarcely put into words, given its visceral and experiential nature.

As Alannis Morrisette said on Watch What Happens Live! in 2019, “For women sometimes, we’re told we can’t be angry; we can’t be sad and we can’t be …17 other feelings. You can’t be anything. So just sublimate it all. Just squish it all down.”

Morrisette is one of many artists who express feminine rage in their music. She and artists like Beyoncé, Fiona Apple, Mitski and many more feature themes in their music that any woman can relate to. Simply put, it’s frustration: being fed up with power structures that delegitimize, devalue or otherwise negate the feminine experience.

While not a new topic of discussion, feminine rage has cropped up recently in online spaces, particularly in creative media. From Fiona Apple’s 2020 album Fetch the Bolt Cutters to SZA’s 2022 hit “Kill Bill,” it seems many people today identify with women expressing a carnal anger at injustice.

Bienen junior Skye Tarshis is the vocalist for indie-rock band parkhopper. They described feminine rage as “both the feeling and action of frustration of systems of domination, particularly patriarchy.”

“It has historically been suppressed or redeemed as madness. And it’s difficult for a lot of women to express the feeling of pure rage because of the way it is understood and suppressed and complicated,” Tarshis said. “Because we don’t have that language, turning to forms of art to create that language is so valuable.”

As a poet and vocalist, Tarshis has written about feminine rage in the past, often drawing on artists like Apple and Mitski for inspiration. She said the feeling of performing music that deals with feminine rage is a very guttural, cathartic experience, helping her to feel empowered in emotions that are difficult to put into words.

Bienen musicology professor Inna Naroditskaya, who focuses much of her research on gender and music, pointed to Diamanda Galás as an example of someone who excelled at performing with rage, saying she made her body a “performance object.” Galas’s music concentrates on issues like the AIDS epidemic, mental illness and political injustice, and her avant-garde style uses screams and other vocal techniques to create an unsettling, emotional soundscape.

WHAT’S WORST, LOOKIN’ JEALOUS OR CRAZY? JEALOUS OR CRAZY MAN, THIS SHIT BUT I’M NOT AND IF YOU WONDERED IF I HATE YOU (I DO) SHITTY OF YOU TO MAKE ME FEEL JUST LIKE THIS STAND SIX FOOT TWO DOES SHE SMILE? OR DOES SHE MOUTH, “FUCK YOU FOREVER”? YOU DON’T OWN ME DON’T TIE ME DOWN ‘CAUSE I’D NEVER AN’ I DON’T GIVE A DAMN ‘BOUT MY REPUTATION NEVER SAID I WANTED THEY SAY SHE’S A SLUT, BUT I KNOW SHE IS MY BEST NO, I DON’T WANT YOUR NUMBER NO, I DON’T WANNA GIVE YOU MINE

YOU WANT I WON’T SHUT UP I WON’T SHUT UP

AGAINST THE (PATRIARCHAL) MACHINE:

POPULAR MUSIC

Tarshis found the same kind of resonance in the sounds Apple used on her latest project. Produced using sounds around her home (banging on walls or floors, dog barks), Apple’s 2020 album utilized screaming and “feverish repetition,” Skye said.

Medill junior Samantha Anderer was first introduced to the idea of feminine rage when TikToks on the subject began popping up on her “For You” page about six months ago. She realized that many of the songs and artists she gravitates toward use these themes in their music.

Anderer said she prefers artists who express feminine rage through their lyrics and messaging rather than in the tone of the music. For her, artists like Phoebe Bridgers, SZA and Lana Del Rey exemplify this type of expression.

“Even if it is called feminine rage, it works counter to a lot of our ideas about what femininity is because it’s allowing women to be angry and to break rules and express themselves in a way that they’ve been taught to repress,” Anderer said. “While recognizing the limits of femininity and language, I think the idea behind it is inherently feminist.”

Tarshis turned to feminine rage in music when she found that “angry midwest/coastal emo,” which she listened to growing up, no longer resonated with her. They turned to artists like Apple and Mitski to find music that reflected “the real sources of [their] anger.”

Communication junior Rivers Leche found a similar comfort in the validation she received when listening to artists that address feminine rage. She found it particularly appealing last summer, when this genre of music allowed her to tap into repressed anger after the reversal of landmark abortion case Roe v. Wade.

“Spoken language is never going to fully be able to communicate the exact emotional experience you’re having,” Leche said. “There’s something about music in particular…where we get to transmit some of those feelings that you can’t exactly put into words.”

At the same time, Leche said that in current feminine rage music, Black musicians such as Beyoncé or Solange may not always fit the typical indie or folk sound that many associate with the genre (think Apple or Bridgers). This exclusion is part of a larger pattern throughout the history of feminism in which the actions or feelings of women of color are not looked at in the same way they are for white women.

SHIT IS DRAINING NOT REALLY RIPPING THE HEADS KICK ME UNDER THE TABLE ALL

YOU BETTER THINK (THINK)

TO

WHY DON’T YOU LAY DOWN AIN’T IT DARK WRAPPED

THINK ABOUT WHAT YOU’RE TRYING

DO

IN

Author bell hooks similarly discussed the way Black Americans are judged differently for their anger in her 1995 book “Killing Rage: Ending Racism.”

“To perpetuate and maintain white supremacy, white folks have colonized black Americans, and a part of that colonizing process has been teaching us to repress our rage, to never make them the targets of any anger we feel about racism,” hooks said.

Leche encouraged music fans to expand their view of what feminine rage in music sounds like, particularly with artists that may be outside of the typical look of this genre. She said one of the most empowering parts of hearing feminine rage in music is that it doesn’t sit within the confines of what patriarchy wants music to sound like. Being able to provide familiarity to marginalized listeners, she said, is one of feminine rage’s greatest assets.

“Often as people of color, as women, as queer people, disabled people, whatever ‘other’ you want to inhabit, you’re forced in mainstream capitalist art to assimilate with … whoever is seen as ‘the mass market,’ and that’s usually a white, middle class audience,” Leche said. “[Feminine rage musicians] are brilliant artists, and to have them be considered on so many different levels and what they can do, who they reach and who they’re speaking to. I think that’s part of why [they’re] so powerful for me.”

Naroditskaya similarly finds fault with feminine rage in music. Because Naroditskaya believes anger is always a negative force, she said she would rather hear women use “communication; strong, positional communication.”

“If rage is going against men, where does it lead? I think it becomes a weakness. The pure, white rage is debilitating. I think that women, strangled as they were — and musical history is good evidence of this — [learned] a lot of tools to go around, to defy,” she said. “Now we don’t live in the

world of the 19th century, even the first half of the 20th century. Women have rights. They have agency. Rage by itself is proving a masculine stance for centuries that women are overwhelmed with … emotions. How about discontent? How about standing strong?”

Naroditskaya said she sees a difference in the feminism of today when compared to the feminism of her day.

“I belong to the generation of feminists who deal with issues. Voting was an issue. Equal rights was an issue. #MeToo is an issue. When you talk about rage, it’s about feelings. And to me this is a little passé,” she said. “If we are just motivated by rage, what happens for me as a musician? Where is it leading to?”

While Tarshis said she understands how feminine rage could be viewed as a way to create apathy, they defended music as a way to communicate and politicize these feelings and inspire change.

“While it can be an expression of unbridled anger, I also think that it can be used to locate what is making you so angry,” they said. “I think anger can be a conduit for recognizing things and challenging them. If you’re not leading with anger, with emotion, what do you do?”

YOU ARE EMBARRASSED OF ME ‘COS I USE MY TONGUE FREELY BET FUCK YOU FUCK YOU VERY VERY MUCH ‘CAUSE YOUR WORDS WHY YOU BOTHER ME WHEN YOU KNOW YOU DON’T WANT ME? WHY YOU BOTHER ME FOR I’M STARTING TO LEARN I MAY NEVER BE FREE BUT THOUGH I MAY NEVER BE FREE DON’T COME AROUND I GOT MY OWN HELL TO RAISE AND ALL THE TIMES THEY WILL

THE PROBLEM WITH POSTHUMOUS ALBUMS

By Eva Putnam

Designed by Alena Baker

In August 2021, the genre-bending musician, Anderson .Paak, posted an Instagram photo of a new tattoo on his forearm. Unlike his other tattoos of doves and a woman praying under a cross, this one reads: “When I’m gone please don’t release any posthumous albums or songs with my name attached. Those were just demos and never intended to be heard by the public.” .Paak didn’t simply write this wish in his will or tell his label to leave his music be — he made this wish permanent and indisputable.

Posthumous records — albums and songs released after an artist has passed away — are a norm. In the past three years, various record labels have released over 27 posthumous albums on behalf of major artists, including Prince’s “4ever,” Pop Smoke’s “Shoot for the Stars, Aim for the Moon,” and Mac Miller’s “Circles.” For over a year leading up to .Paak’s post, posthumous albums had been charting in the top 10 nearly every week.

Despite their prevalence, however, the entire concept of post-death albums has been a point of contention within the music community for decades. What are the labels’ intentions? Are they doing it for the fans? Would artists want unfinished tracks finished for them? Many have landed on a mix of all of these options, maintaining that in an attempt to squeeze the remaining dollars from a dead artist’s career, labels will throw posthumous albums together, and market it as the last connection fans can have to the artist.

“In the past few years, labels have proven themselves to be absolutely unscrupulous in their desperation to capitalize off of and suck the last drops of blood out of any artist’s career or discography the moment they die,” said music critic Anthony Fantano in a 2022 Youtube video.

From Chess Records gifting their artists Cadillacs instead of paying them royalties in the 1950s to Prince’s infamous battle with Warner Brothers Records over his inability to release projects and their contractual owning of his name, record labels have a long history of artist exploitation.

Time and time again, artists, producers and music aficionados have accused major labels of participating in corrupt practices that funnel cash into their pockets while stripping artists of their rights and autonomy. Even today, this behavior is considered a tried-and-true tradition. While label exploitation ranges in severity, much of it boils down to the percentage that labels take from artists’ profits. According to Jason Bazinet, a Citigroup media researcher, artists — or in the case of posthumous albums, their estate — only capture around 10 percent of the profits they bring in through albums. “That’s amazingly low,” he told Rolling Stone.

As for the remaining 90 percent — the label takes it.

“At some level it is a grimy business, but it’s all driven by capitalism,” said Samuel Fifer, a media and entertainment lawyer and partner at Dentons US LLP. “In for a penny, in for a pound.”

From the label’s perspective, an artist’s death means the death of future profit. Posthumous albums opened up a new door. While the artist may not be able to put another record together themselves, the label can do it for them and continue to get their 90 percent.

“Everything becomes a fire sale,” said Fifer. “They monetize anything and everything they can.”

Although artists like .Paak were able to tell the world not to touch his music after passing, some artists didn’t get a chance to make that decision. Certain posthumous projects from young creatives, like The Notorious B.I.G’s “Life After Death,” are renowned for their sound production and honoring of the artist’s legacy — however, many are nothing more than a haphazard patchwork of demos and features that misrepresent the artists’ style and sound.

“It’s like they take a little scrap or shred of a verse and they put it on a totally different beat and then put a bunch of other people on it,” said Bryce Beverlin II, the owner and curator of the Insides Music record label. “I often cringe at those things. It always seems cheap.”

To many people, cheap was the best way to describe the second posthumous album of New York drill rapper Pop Smoke.

In February of 2020, Bashar Jackson, better known as Pop Smoke, was murdered during a home invasion at a Los Angeles rental house. At just 20, not even two weeks after he released his second mixtape, “Meet The Woo 2,” his career ended abruptly. After this tragedy, Pop Smoke’s labels Victor Victor Worldwide and Republic Records began working on the artist’s debut — and first posthumous album — “Shoot For The Stars, Aim For The Moon,” with the help of executive producer 50 Cent and Pop Smoke’s close friends and family.

50 Cent told Complex that when they began compiling the debut, they had a total of 50-60 tracks to choose from, and Steven Victor, Pop Smoke’s manager and owner of Victor Victor Worldwide, said that 80% of these archived songs “were finished the way he wanted them finished.” This would mean that only 40 to 50 of these options were finalized while Pop Smoke was still alive. “Shoot For The Stars Aim For The Moon (Deluxe)” consisted of 34 of these finalized tracks.

Some simply thought that the tracks were poorly mixed and produced, leaving the album sounding rushed and unfinished — something Pop Smoke would never let happen. Others were bothered that 50 Cent and those close to Pop Smoke were not a part of the production process.

And one of the biggest complaints was that fans felt there was a lack of Pop Smoke’s voice on a Pop Smoke album.

“When Pop does have the song to himself, he rarely raps for more than 90 seconds,” said culture writer Keith Nelson Jr. in a Mic article. “It’s clear there was not much Pop music to make a full-length album anchored largely by the Canarsie icon, resulting in Pop sounding like a guest on his own album.”

Given that when Pop Smoke died he had 40 to 50 tracks loosely finalized, and his debut used 34 of those, it’s not surprising that there’s an absence of Pop Smoke, himself, on “Faith.”

When the album came out in July of 2020, both fans and critics adored it. It sold over 251,000 units within its first week and charted at No. 1 on Billboard’s Top Rap Albums for 20 weeks, breaking the record held by Eminem’s “Recovery.” Fans remarked that it was the “album of the year” and that the songs showed them a different side to Pop Smoke’s voice. The album was a massive success.

However, when Pop Smoke’s labels released his second posthumous album, “Faith,” fans had a much different reaction.

“Nobody wants new Pop Smoke music because it ain’t even Pop Smoke music,” wrote one Twitter user. “This posthumous music thing is really becoming a market of garbage in the name of artists who had high standards when they were alive and it’s annoying.”

The list of criticisms “Faith” received was long. Many fans were upset with the number of seemingly random features the album had, given that Pop Smoke often stated he prefers not to have featured artists on his music.

After all, there were only 6 to 14 finished songs to include. Since the deluxe version of “Faith” contained 30 tracks, not even half of the album’s songs could have been completed while the artist was alive. With this, the label turned to fragmented demos and unfitting features, patchworking scraps together. It was the label’s album, not his.

“If Pop was alive he would not [have] approved 99 percent of the stuff they put out,” said Rico Beats, one of Pop Smoke’s producers.

Chasing a profit, these labels end up damaging artist’s legacies by putting together records that many artists wouldn’t want the world to hear. Their death becomes a new way to make money.

Record labels’ exploitation of artists doesn’t just occur while they’re alive — it’s posthumous.

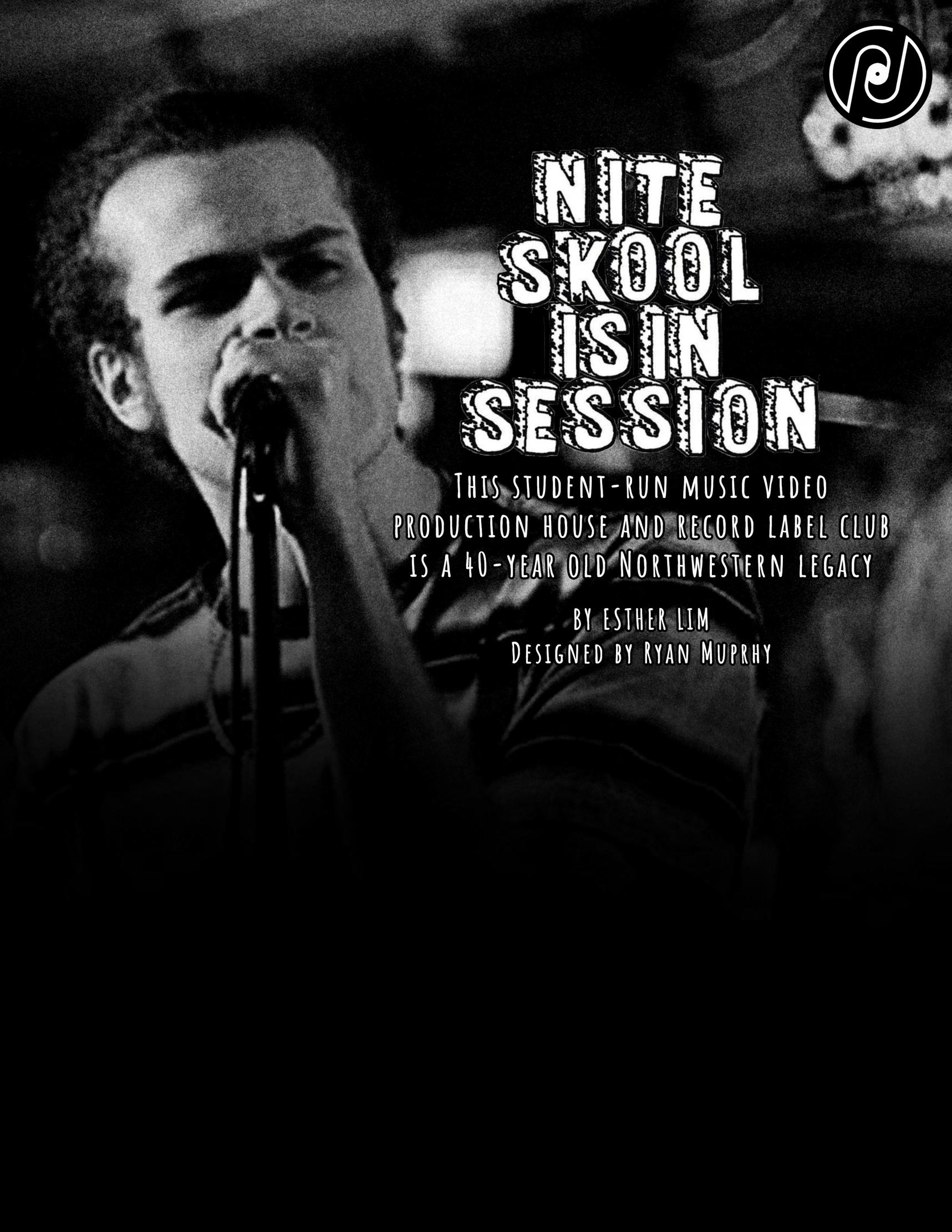

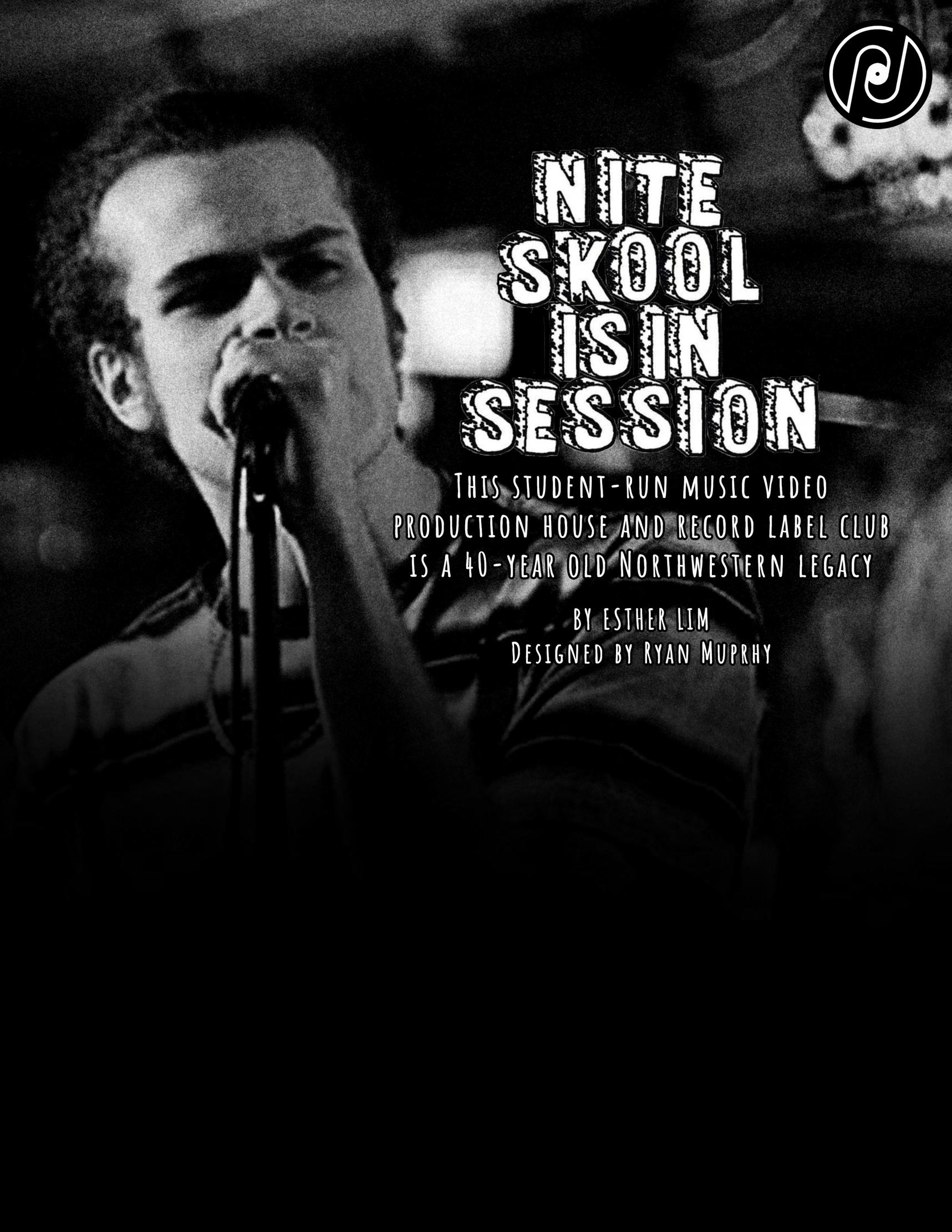

While the rest of Northwestern was fast asleep, members of the Niteskool Project spent sleepless nights in rented recording studios and post-production facilities to complete albums and music videos in the ‘80s. They formed their own personal “Niteskool,” where they got real-world experience. Forty years later, the club is still in session.

While the rest of Northwestern was fast asleep, members of the Niteskool Project spent sleepless nights in rented recording studios and post-production facilities to complete albums and music videos in the ‘80s. They formed their own personal “Niteskool,” where they got real-world experience. Forty years later, the club is still in session.

While Niteskool was originally centered around producing music videos for records written, performed, recorded and distributed by Northwestern students, it’s now broadening its horizons. This year, Niteskool launched a record label, Niteskool Records. Inspired by hip hop magazine XXL’s annual “Freshman Class,” a list of up-and-coming rappers, it’s now focusing on highlighting Northwestern artists.

While Niteskool was originally centered around producing music videos for records written, performed, recorded and distributed by Northwestern students, it’s now broadening its horizons. This year, Niteskool launched a record label, Niteskool Records. Inspired by hip hop magazine XXL’s annual “Freshman Class,” a list of up-and-coming rappers, it’s now focusing on highlighting Northwestern artists.

The idea came about when co-presidents Kay Cui and Mihir Rajwade were looking for a project to incorporate all three of Niteskool’s subcommittees — production, promotion and artists and repertoire (talent scouting). Every week, these teams meet in these groups to work on their respective duties and bounce ideas off each other, which then gets conveyed between the committees during exec board meetings.

The idea came about when co-presidents Kay Cui and Mihir Rajwade were looking for a project to incorporate all three of Niteskool’s sub-committees — production, promotion and artists and repertoire (talent scouting). Every week, these teams meet in these groups to work on their respective duties and bounce ideas off each other, which then gets conveyed between the committees during exec board meetings.

“We have so many talented people on this campus,” said Kay Cui, a School of Communication third-year. “While they’re really talented,

“We have so many talented people on this campus,” said Kay Cui, a School of Communication third-year. “While they’re

they’re also our peers. You could literally be sitting next to them in psych class and then see them perform live original music on the weekend. Our focus was kind of shifting toward supporting them and helping them build their brand and career as an artist.”

really talented, they’re also our peers. You could literally be sitting next to them in psych class and then see them perform live original music on the weekend. Our focus was kind of shifting toward supporting them and helping them build their brand and career as an artist.”

Micheal Ewarawon, a rapper and third-year in the School of Professional Studies who goes by the name TiggyBouf, is one of this year’s class of artists. The Niteskool partnership helped him establish his presence on campus, he said.

Micheal Ewarawon, a rapper and third-year in the School of Professional Studies who goes by the name TiggyBouf, is one of this year’s class of artists. The Niteskool partnership helped him establish his presence on campus, he said.

“I know that doing my studies should be my No. 1 focus, but I also want to have a good time,” Tiggy said. “So what can I do to make myself stand out, to give me a presence and to be somebody that’s consequential to the community? That’s what music did for me.”

“I know that doing my studies should be my No. 1 focus, but I also want to have a good time,” Tiggy said. “So what can I do to make myself stand out, to give me a presence and to be somebody that’s consequential to the community? That’s what music did for me.”

But before the label launched this year, the organization’s presence on campus fizzled out from overspending on largescale music videos and entered a financial deficit around 2015. Now, Niteskool is running on momentum that then-sophomore Erica Bank (Bienen ‘20) and School of Communication

But before the label launched this year, the organization’s presence on campus fizzled out from overspending on large-scale music videos and entered a financial deficit around 2015. Now, Niteskool is running on momentum that then-sophomore Erica Bank (Bienen ‘20) and School of Communication Professor Jake Smith initiated to bring Niteskool back to Northwestern in 2017.

Professor Jake Smith initiated to bring Niteskool back to Northwestern in 2017.

“There were a lot of meetings with Northwestern organizations and faculty who had kind of soured on Niteskool because of financial issues,

“There were a lot of meetings with Northwestern

so they had to be convinced that Niteskool should be relaunched,” Smith said. “It was a lot of work to clear the path, but once they had opened the freeway, they went 60 miles per hour.”

While considering different directions that the revived club could take, Bank had a lightbulb moment at 3 a.m. after binging NPR Tiny Desk videos one sleepless night during her sophomore year.

“How cool would it be if we kind of mimicked this concept and filmed these intimate performances in unconventional settings in and around Evanston and on campus?” Bank said.

Bank’s idea soon grew into Niteskool sessions, a video concert series featuring Northwestern, Evanston and Chicago talent. In addition to Niteskool Sessions, Bank also took on the Niteskool Alumni Reunion in 2019, bridging current and previous generations. She received Northwestern’s Purple Pride Award for her leadership.

During the reunion, co-founder of Niteskool Eric Bernt (SoC ‘86) said he recognized the same determination and persistence in Bank.

“I said to her, ‘I recognize the exhaustion in your eyes, I hope you wear it proudly,’” Bernt said. “And she looked at me with these knowing eyes and said something to the effect of, ‘Only you know how hard this really is.’ She kind of nodded and said it was the hardest best thing she’d ever done.”

In 1983, Bernt had just transferred out of Medill and into the School of Communication, where he developed an interest in music videos. When he met Jon Shapiro (SoC ‘87), the two formed a friendship that was “seemingly meant to happen” and filled in each other’s gaps of experience and expertise to bring their dream of making music videos to reality.

Combining Shapiro’s experience in the music studio and Bernt’s tenacity and financial know-how, their vision for a student-run music video production club became a reality through negotiated discounts for studio time and even a corporate sponsorship with Miller Brewing Co. for its first year.

“We would go to these big post production facilities and rental houses that had really high end commercial gear — better than the school had at the time,” Shapiro said. “But we did it at night from midnight to 4 a.m. I didn’t sleep well during college, but I’m very proud of what we did.”

The two continue their work in the media industry today, with Bernt as an author and screenwriter and Shapiro as a producer and president of his company, Ideal Entertainment Inc. As starry-eyed college students, they were around for the exciting era of MTV and its role in shaping the music videos into the medium it is today. In fact, their 1986 video “Next to You” was featured on The MTV Basement Tapes, a series highlighting unsigned artists and groups.

“Because music videos were exclusively the domain of MTV and major labels and stars, there was definitely a little bit of, ‘What? At

Northwestern? How could that be?’” Shapiro said. “It was beyond our wildest dreams.”

Yet the process of launching the club came with challenges. Even with a grant from the School of Communication (then called the School of Speech) and a loan from ASG, it wasn’t enough to budget their visions. But rejection after rejection, Bernt didn’t bat an eye, as per Niteskool’s first ever record, “Ambition.”

Bernt borrowed a car, drove up to Milwaukee in his one suit and tie and sat before a room of Miller Brewing Co. board members to pitch the Niteskool Project.

“I said, ‘Look, we’re the kind of young people that you want associated with your brand.’ Now, I left out the fact that most of us can’t legally drink in the state of Illinois,” Bernt said. “The affiliation with Northwestern was what I sold them on. And they bought it, to my amazement. It was one college kid on one side of a boardroom and about six grownups on the other side. I was so intimidated. I think they thought it was funny that I was undeterred.”

They received more money than the School of Speech and ASG’s loan combined through that sponsorship. Bernt still remembers how packed Annie May Swift Hall was on the night of their first premiere in the spring quarter of ‘84. Every square inch of the auditorium was filled — every seat, even the aisles. They even had to host a second screening for those who couldn’t make it.

“The response was really positive,” Bernt said. “It wasn’t just because students loved the video as a final product. They loved what it represented and that we had delivered: being proud of our school, having something that students weren’t doing anywhere else. There was that feeling of ownership that we had created.”

These days, the two continue their work in the media industry today. Bernt is an author and screenwriter and Shapiro is a producer and president of his company, Ideal Entertainment Inc.

Continuing the legacy that Bank inherited from Bernt and Shapiro, Niteskool is balancing its longevity while tackling new projects and goals like videos featuring orchestral ensembles to accompany their rappers’ performances and more live performances for the community, said Rajwade, a Weinberg third-year.

And though Niteskool has evolved and grown in its focus since its founding, it’s sticking to its original mission: offering Northwestern students a space to invest in their joy and passion for the music industry.

“I just don’t know what my four years at Northwestern would have been without Niteskool,” Shapiro said. “In some ways, I did Niteskool with an occasional secondary school part…When you find something that speaks to you and gives you purpose, you want to hold on to it and give it your all.”

BLACK FOLKS HAVE BEEN POINTING OUT THE

And two, because it’s cool. The American conception of coolness and what is popular has long been determined by Black urban youth, yet simultaneously, there has been a historical, conservative pushback against this “coolness,” rebranding it as a sense of “corruption” of youth. The concept of cool stems from the Yoruba term Itutu, which describes the characteristic of being calm and collected under pressure. Upon being placed on slave ships and landing in the New World, the notion of Itutu gained even greater significance for African Americans. Some Black scholars consider remaining cool in the face of systemic racism and infinite external pressure a form of survival and resistance.

These scholars also argue that to accept and validate an exceptional black coolness is to validate a sense of racial otherness and white normalcy. Others, however, see Black coolness as empowering. Corporate America doesn’t care. All they know is that this coolness sells, as there is nothing better to sell than social status. This realization and incorporation of the pursuit of cool into marketing campaigns would drive coolness into two distinct camps, those of coolness lived and coolness purchased.

Under this theory of coolness, we can analyze drill music what originally was true to drill artists was packaged and purchased by white audiences. Drill music began in Chicago’s South Side as a response to the poverty and gang violence that plagued the poorest area in one of the most redlined states in America. Within South Side neighborhoods, teenage boys began to process and chronicle their lives growing up in the area, which would come to be known as “Chiraq.” One of these boys was Keith Cozart, otherwise known as Chief Keef. At age sixteen, while on house arrest at his grandma’s house, he made and released the video “I Don’t Like.” The song bears resemblance to Atlanta trap, but it’s darker. Its lyrics are violent and gritty, complemented by a beat, produced by seminal producer Young Chop, that features stuttering, almost frantic high-hats, heavy hitting 808 bass outlining the root notes of dark synth chords, and a haunting chyme melody. This was trap music, and it was going to take over the world.

Drill sound was developing before Chief Keef started recording in his grandma’s house. Two years prior, an artist named Pac Man released a mixtape, featuring a song titled “It’s a Drill” which

referenced shooting at members of rival gangs. Keef, however, was the first person to reach an audience outside of the South Side. The song went viral, reaching number 73 on the Billboard Hot 100. Several months later, he followed his success up with the seminal “Love Sosa,” this time peaking at number 56. His music got the attention of the industry, with Drake and Kanye shouting praise, and the young rapper was soon swept up by Interscope records. Seeing the success of their comrade, other members of the community such as Lil Durk and G Herbo soon began making music of their own. And it worked.