Origin of Juneteenth

Juneteenth, also known as Freedom Day or Emancipation Day, commemorates the emancipation of enslaved African Americans in the United States. Its origin can be traced back to June 19, 1865, when General Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston, Texas, and announced the end of slavery in accordance with President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, which had been issued more than two years earlier.

The delay in the news reaching Texas was primarily due to the limited presence of Union troops in the state during the Civil War. Slavery persisted there until Granger’s arrival, making Juneteenth a significant date in the state’s history. The newly freed people in Texas celebrated their newfound freedom with jubilation, embracing this day as a symbol of liberation and hope for a better future.

Over the years, Juneteenth gained momentum as an annual celebration within African American communities. Initially, it was predominantly observed in Texas, but later spread to other states and regions across the country. African Americans organized parades and gatherings to commemorate the day and reflect on the struggles and achievements of their ancestors.

Juneteenth’s significance has continued to grow, and it has gained national recognition as a day of remembrance and reflection on the African American experience. Efforts to recognize Juneteenth as a federal holiday intensified, and on June 17, 2021, President Joe Biden signed the Juneteenth National Independence Day Act, establishing Juneteenth as a federal holiday, marking a milestone in the recognition of the historical importance of this day.

Today, Juneteenth serves as a reminder of the long journey towards freedom, the resilience of the African American community, and the ongoing pursuit of equality and justice for all. It stands as a testament to the power of freedom and the enduring spirit of those who fought for their liberation.

Emancipation Proclamation

President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, declaring “that all persons held as slaves” within the rebellious states “are, and henceforward shall be free.”

Despite this expansive wording, the scope of the Emancipation Proclamation was limited. It applied only to states that had seceded from the United States, leaving slavery untouched in the loyal border states. It also expressly exempted parts of the Confederacy (the Southern secessionist states) that had already come under Northern control. Most important, the freedom it promised depended upon Union (United States) military victory.

Although the Emancipation Proclamation did not end slavery in the nation, it captured the hearts and imagination of millions of Americans and fundamentally transformed the character of the war. After January 1, 1863, every advance of federal troops expanded the domain of freedom. Moreover, the Proclamation announced the acceptance of black men into the Union Army and Navy, enabling the liberated to become liberators. By the end of the war, almost 200,000 black soldiers and sailors had fought for the Union and freedom.

From the first days of the Civil War, enslaved people had acted to secure their own liberty. The Emancipation Proclamation confirmed their insistence that the war for the Union must become a war for freedom. It added moral force to the Union cause and strengthened the Union both militarily and politically. As a milestone along the road to slavery’s final destruction, the Emancipation Proclamation has assumed a place among the great documents of human freedom.

Source: U.S. National Archives

General Order No. 3

On June 19, 1865, two and a half years after President Abraham Lincoln’s historic Emancipation Proclamation, U.S. Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger issued General Order No. 3, which informed the people of Texas that all enslaved people were now free. Granger commanded the Headquarters District of Texas, and his troops had arrived in Galveston the previous day.

While the order was critical to expanding freedom to enslaved people, the racist language used in the last sentences foreshadowed that the fight for equal rights would continue.

The text of General Order No. 3 follows

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.”

Source: U.S. National Archives

Wisconsin Veterans Who Served with Union Troops

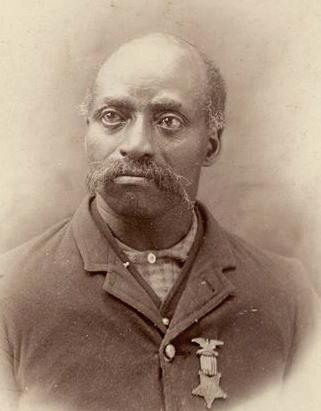

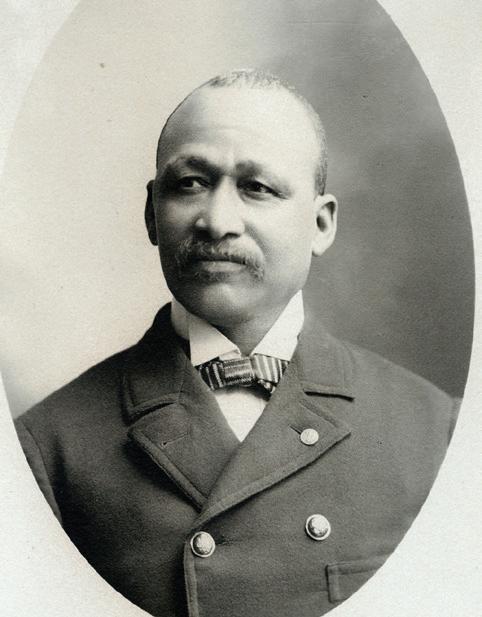

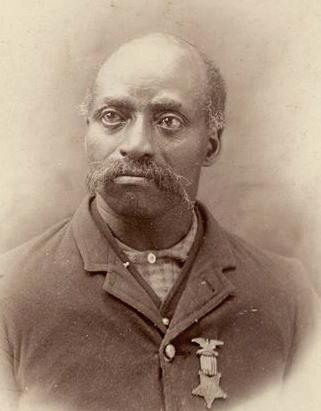

Henry Ashby, 6th Wisconsin Light Artillery Eagle River, Wisconsin

Henry Ashby, an enslaved person born in Missouri in 1832, sought his freedom within Union lines near New Madrid, Missouri before joining up with the 6th Wisconsin Light Artillery near Huntsville, Tennessee in July 1862. While with the battery, Ashby worked for Lt. Samuel Clark as a cook, sometimes joined the battery during battles carrying a musket, and was wounded during the Battle of Corinth. Though Ashby served over two years, he was never officially listed on the unit roster.

When Clark returned to Wisconsin in 1864, Ashby came with him and lived in Stevens Point and Eagle River, Wisconsin. After the war, he was accepted by his fellow veterans as a member of the local GAR (Grand Army of the Republic) post. However, when Ashby applied for an invalid veteran pension with support from his comrades, his application was denied because his name never appeared on the official unit rosters.

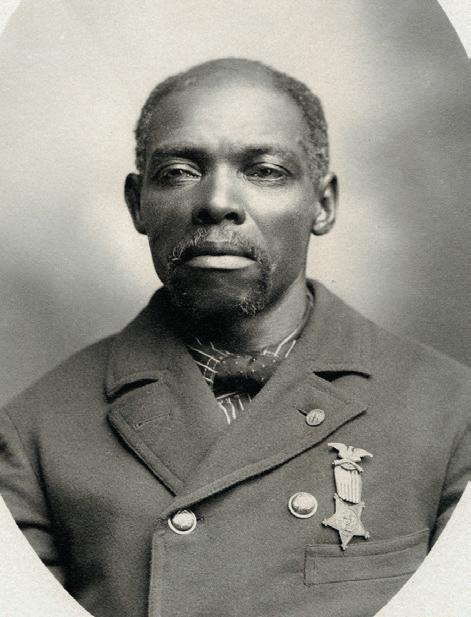

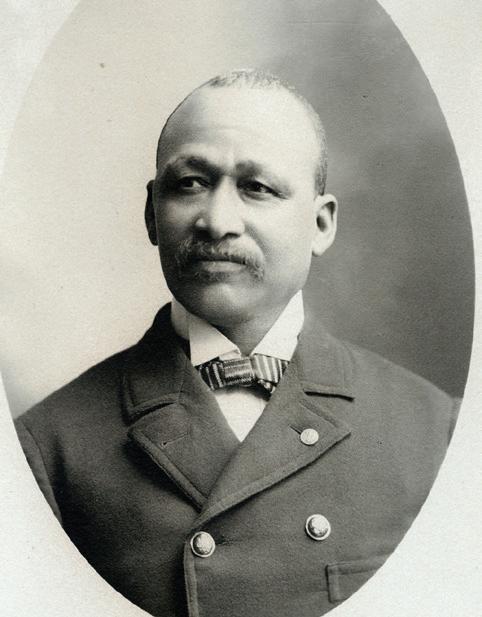

Horace Artis, Company F, 31st United States Colored Troops (USCT) Appleton, Wisconsin

Horace Artis, an enslaved person born in Virginia, along with thousands of other slaves in the region gained their freedom in Union-occupied Norfolk, Virginia with the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. In 1864 Artis joined the 31st USCT in Washington D.C. serving with the unit through the remainder of the war, and was present at the Confederate surrender at Appomattox in 1865. After the war, Artis settled in Appleton, Wisconsin and was a member of Appleton’s GAR (Grand Army of the Republic) veterans’ post.

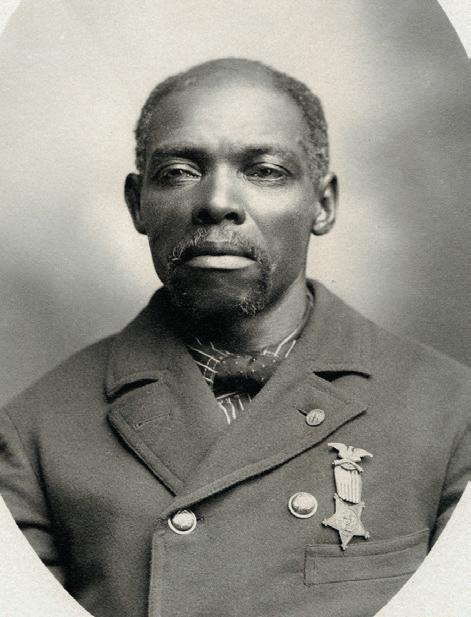

Joseph Elmore, United States Colored Troops (USCT) Appleton, Wisconsin

Joseph Elmore (sometimes listed as “Ellmore”) enlisted in February 1865 and served in a post hospital while in service. His enlistment was credited to Milwaukee. After the war he lived in La Crosse. He later settled in Appleton and worked as a barber.

About the Wisconsin Veterans Museum

As a means to educate and inspire an intelligent love of country since 1901, the Wisconsin Veterans Museum preserves and shares the stories of Wisconsin veterans from the Civil War to present day.

The museum is one of two Smithsonian Affiliate museums in the state and is accredited by the American Alliance of Museums.

Your Visit

W. MIfflin Street on the Capitol Square in Madison

Plan

30