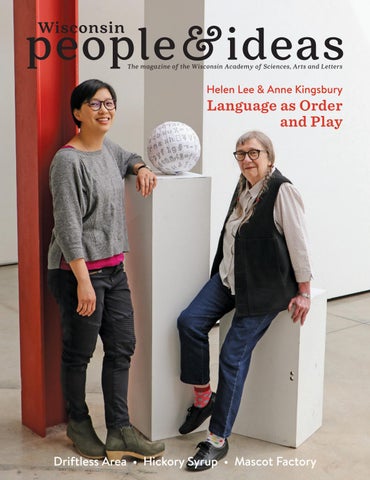

Helen Lee & Anne Kingsbury

Language as Order and Play

Fighting the Formidable Flying Foe Mosquito research in Wisconsin

Mayana Chocolate Riders •• Mascot GrimmFactory & Litherland Driftless Area •• Freedom Hickory Syrup

Helen Lee & Anne Kingsbury

Language as Order and Play

Fighting the Formidable Flying Foe Mosquito research in Wisconsin

Mayana Chocolate Riders •• Mascot GrimmFactory & Litherland Driftless Area •• Freedom Hickory Syrup