SCHOOL INTERNATIONAL magazine

EDUCATING IRAQ

Launching a Britishbranded schools network AI strategy and the human challenge

When inclusion is more than a buzzword

Affluent neglect: walking the tightrope

Launching a Britishbranded schools network AI strategy and the human challenge

When inclusion is more than a buzzword

Affluent neglect: walking the tightrope

schoolmanagementplus.com

Our School Management Plus online platform offers a wealth of information to keep education professionals up to date, including:

• latest news, regular features and opinion

• monthly newsletter and jobs to your inbox

• contribute your own ideas and opinion

• join our webinars and round-table discussions. We are the leading opinion platform for those running a modern international school. We are always keen to hear about the issues that matter to you most, so get in touch to have your school’s voice heard. editor@schoolmanagementplus.com

The leading source of news, opinion, features & jobs for all professionals working in independent and international education.

@ International School News @SchoolManagementPlus @SchoolManagementJobs @SchoolAdmissionsPlus @ISM_Plus @schoolmanagementplus5799

EDTECH

4 Becoming head of AI at a global schools group was more than a matter of getting to grips with the tech, writes Richard Human

WELLBEING

7 Detecting and handling cases of affluent neglect in international schools can be a tricky task requiring diplomacy, writes Shane Daly

SEND

11 Being a truly inclusive international school takes bravery and very careful thought, write Anita Gleave and Clemmie Stewart

EXPERIENCE

14 The real strength of a school trip lies not in the destination, but the people we forge relationships with on the way, writes Tom Penny

LEADERSHIP

16 The tricky task of leading a British international school abroad offers perspective, agility, and insight, writes Carly Barber

RISK

19 When launching a new international school, what can go wrong will go wrong, writes Denry Machin

HOW WE DID IT

22 Launching a British-branded schools network in Iraq has been an incredibly rewarding challenge – but it’s all about the students – writes Timothy Fisher

THE INTERVIEW

25 From the stock exchange to international school leadership via SOAS, Mike Lambert has followed a varied path to his latest big role

ASK THE RECRUITER

29 Hugh Martin from recruitment experts Anderson Quigley looks at what educators should consider before deciding to work abroad

ON THE COVER

Educating Iraq, page 22

Becoming head of AI at a global schools group was more than a matter of getting to grips with the tech, writes Richard Human

The trolley arrived one morning in September, laden with pristine iPads in their sleek cases. Twentyfive devices, one for each child in my class – our school’s bold leap into “21st-century learning.” I felt that familiar flutter of excitement that comes with shiny new technology and its infinite possibilities.

By the following week, the reality had set in. I stared at twenty-five screens and realised I hadn’t the faintest idea what to do with them.

We muddled through – stop-motion films here, news reports there, the obligatory Newsround sessions and RMeasymaths activities. The children were engaged, certainly, but was this the transformative education we’d been promised? Gradually, as other priorities pressed in and no one was asking pointed questions about our iPad usage, they slipped down my mental list. After all, I reasoned, my performance wasn’t being measured on creative tablet deployment.

Looking back, that trolley of devices taught me more about educational technology than any training session ever could. The marketing materials had spoken of revolution; the reality was a well-meaning teacher trying to retrofit expensive hardware into lessons that worked perfectly well without it. The “1-to-1 technology” boast looked impressive in prospectuses, but I suspect it served the marketing department rather better than it served my pupils.

different

When I began my role as head of AI at Globeducate, I was determined not to become the trolley pusher – the enthusiast wheeling around the latest technological cure-all that would finally “save education.” I’d seen too many promising innovations gather dust in cupboards, victims of poor implementation and unrealistic expectations.

But I also recognised something fundamental: AI could not be compared

to the use of an iPad. This wasn’t another piece of hardware to be awkwardly shoehorned into existing lessons. AI represents something altogether more profound – a technology that was already beginning to reshape how we work, communicate, and think, with particular implications for the young people we teach.

I knew that teachers would be spinning all sorts of plates in their classrooms –assessment, differentiation, behaviour management, curriculum delivery, pastoral care, data collection, parent communication, and countless others. The last thing they needed was another plate to add to their precarious collection. Instead, I wanted to help some of those plates spin themselves, or even take down some plates entirely through the thoughtful introduction of AI.

Strategic focus: doing less, better I inherited an ambitious AI strategy that spanned everything from Space & Innovation Centres to pioneering student projects such as “Ainstein Jr” and “AI Sustainable Cities” designed and led by my colleague Elpidoforos Anastasiou.

Working with our chief education officer, Daniel Jones, we made a crucial decision: focus our immediate efforts on two fundamental pillars. First, meaningful AI training for teachers – not just showing them the latest tools, but helping them understand how AI could genuinely reduce their workload whilst enhancing their practice. Second, curriculum development that would prepare students not just to use AI, but to think critically about its role in society.

Everything else, however worthy, would have to wait. Because if we couldn’t get these basics right, all the innovation centres and youth councils in the world wouldn’t matter.

Teacher training: Meeting people where they are

For the teacher training, I knew I had to be both comprehensive and realistic. The

challenge was our context: 70+ schools across 11 countries, each with different curricula, languages, educational approaches, and priorities. What works for a staff meeting in Barcelona might be completely unsuitable for a training day in Chennai.

Before launching any training, the head of wellbeing, Rhiannon Phillips-Bianco, and I recognised we needed to understand the human impact of these changes. We’ve designed a survey – a “dip survey” – to discover colleagues’ sense of wellbeing before and after implementing these AI initiatives. Teachers are already under pressure; the last thing we want is for our AI support to become another source of stress rather than relief.

Rather than create a one-size-fitsall programme, I built a flexible toolkit. Teachers might access the same core content as a 60 to 90-minute training day session, spread across staff meetings, or work through it independently. I created video tutorials for visual learners, presentation slides for traditional training sessions, PDF guides for self-paced learning, comprehensive FAQs for quick problemsolving, and ready-to-use templates that teachers could adapt immediately.

The key insight was this: teachers are already experts at differentiation for their students. They needed AI training that was similarly differentiated for them.

Curriculum development: From theory to practice I inherited a 38-page AI curriculum document – impressive in scope but comprehensive to the point of being overwhelming. The curriculum mapped every conceivable AI concept across every age group, with detailed competency frameworks that would have challenged universities to implement, let alone busy primary schools.

Daniel and I made another strategic decision: distil this into something manageable. Instead of launching three years’ worth of content simultaneously, I

created just six lessons for 11 to 14-yearolds – what I called “Chapter 1: Meet AI: Machines That Learn.” These 40-minute sessions slot into form time, self-directed study periods, or assemblies, with multiple delivery formats including 15 to 20-minute video tutorials that pupils can follow independently.

Each lesson builds systematically –from “What is AI?” through to hands-on work with Google’s Teachable Machine, culminating in students designing their own AI assistant. Crucially, we wove privacy and ethical considerations throughout rather than leaving them as an afterthought.

The approach is deliberately scaffolded. Get Chapter 1 right across all our schools, then roll out the second chapter the following academic year. This means teachers aren’t overwhelmed, and we can refine our approach based on real classroom feedback.

Building community: Bringing the outside in

Beyond formal training and curriculum, I recognise that AI adoption needs ongoing conversation and community. I write a weekly blog called “The Good, The Bad and The Ugly of AI” for all colleagues, sharing AI stories from around the world.

When ChatGPT is banned in New York schools, when AI helps diagnose a rare disease, when deepfakes cause chaos in elections – teachers need context for the technology reshaping their students’ world.

I also became the organisation’s unofficial AI reading service, distilling insights from Dan Fitzpatrick’s “Infinite Education” into weekly notes for headteachers – essentially doing their reading for them, recognising that school leaders are drowning in priorities.

The children were engaged, but was this the transformative education we’d been promised?

But perhaps most importantly, I record podcasts and webinars with teachers across the organisation. I want to shine an AI light on colleagues who are already experimenting and innovating.

There’s incredible expertise happening in silos across our schools – a primary teacher in Rome using AI to help write the end-of-year performance, a geography teacher in Bilbao using AI as a teaching assistant whilst working with students who need extra support, a science teacher in Canada who designed an “AI Checklist” for students to use when deciding whether to use AI in their work.

All this work is happening without me. I don’t want to get in the way of innovation, but I do want to help as many as possible feel comfortable innovating – then I want to share their stories.

To take this further, we’re launching

an annual AI Innovation Competition. We provide teachers with full licences to advanced AI software like Microsoft Copilot Pro, give them freedom to choose their own projects, and support them across a full academic year. The outcomes are unpredictable – and that’s exactly the point.

Much of this work has already begun, but the real test comes during the 2025-2026 academic year, when we implement the curriculum, launch the AI Innovation Hub, and see whether our approach of starting small, building systematically, and supporting rather than directing innovation actually works at scale across 70+ schools.

Six months into this role, I’ve learned that the challenge isn’t technological – it’s human. The question isn’t whether AI will transform education, but whether we can help teachers feel confident enough to shape that transformation themselves. ◆

Richard Human has been a teacher and school leader for 25 years. He is currently head of artificial intelligence at global schools group Globeducate.

Take the next step in your career

Discover our range of education courses at Bath, taught by an international team of experts.

Campus-based courses:

• MA Education

• MA TESOL

• MA International Education and Globalisation

Part-time distance learning courses:

• MA Education

• PG Certificate in International Education

• MSc International Development with Education

We also offer research degrees:

• MRes Education

• PhD Education

• Doctor of Education (EdD)

Scan QR code to find out more

Detecting and handling cases of affluent neglect in international schools can be a tricky task requiring diplomacy, writes Shane

Daly

Affluent neglect is a precarious topic. A tightrope of rhetorical questions, a careful balance of not wanting to offend a parent and needing to safeguard a child.

Affluence is an aspiration for many and often regarded as the ultimate professional chequered flag. A finish line and a clear indicator for success. However, affluence can muddy the waters of well-being. The child that optically has it all, can be the child that is in most need of everything.

Money is a double-edged sword, often a lifetimes work culminates in a monetary reward and financial stability but at what expense? International schools have been on the front line of this question for some time now. None more so than Dubai. Dubai is incredible. A city, spilling over with opportunity, world class education, limitless activities and amazing career progression. Streets paved with gold. Figuratively and literally.

Students come to school in Ferraris, Rolls Royces and Lamborghinis, dressed in designer clothing.

Some of the wealthiest people in the world reside in Dubai, old money and new money million and billionaires. Dubai is income tax free and perpetually alluring to the uber rich. One could be forgiven for

asking, where is the safeguarding issue here?

Good question. Because to the untrained eye, there is none. This is where inclusion teams become extraordinarily powerful. Students come to school in Ferraris, Rolls Royces and Lamborghinis, dressed in the most incredible designer clothing, carrying their iPads and their schoolbooks in Louis Vuitton backpacks. It takes a very well-trained eye to spot the risk. Because, sometimes all that glitters is not gold.

One has to be skilled in empathy, kindness, and delicate as a beeswing when dealing with affluent neglect, because what if you’re wrong? How do you spot affluent neglect? What is it and what to watch out for? Affluent neglect can come in many different guises.

In Dubai, many parents are double-working professionals with high-powered roles that involve significant travel or long hours. This can lead to situations where children are materially provided for but lack sustained emotional presence from their parents. Teachers may notice students who consistently seek validation from staff, appear withdrawn during group activities, or over-share personal details in class as a way of filling the emotional void.

Here, the inclusion team plays a crucial role by monitoring patterns of emotional withdrawal, while the pastoral team ensures mentoring structures provide students with trusted adults in school. However, educators must tread carefully, in a transient expatriate environment, temporary absences may F

be misinterpreted as neglect when they are simply a product of professional demands. The designated safeguarding lead must weigh these contexts with care, documenting concerns before escalating.

Over-reliance on nannies and domestic staff

It is common in Dubai for families to employ nannies, drivers, or household staff, who often take on the role of primary caregiver. While these individuals may provide excellent practical care, they are rarely decision-makers when it comes to safeguarding or emotional wellbeing. Teachers may notice that nannies consistently attend parent meetings, pick up learners daily, and handle communication, while parents remain largely absent. This reliance is not unique to Dubai, it mirrors patterns in other global financial centres, but it does raise safeguarding challenges.

Educators should acknowledge nannies’ contributions while ensuring the responsibility for a child’s wellbeing is directed back to the parents. Inclusion teams and pastoral leaders can support by offering parent workshops that nannies may attend, but safeguarding conversations should always include the parents. The precarious nature of this dynamic means schools must be respectful, overstepping this mark can strain relationships, the alternative is underreacting, but this can leave children vulnerable.

Dubai’s competitive education market, combined with high parental expectations, can result in students facing significant pressure to excel academically or socially. Some parents equate success with top exam scores, elite university pathways, or high-profile extracurricular achievements. Teachers may spot signs of stress such as perfectionism, heightened anxiety before assessments, or a fear of failure that leads to emotional outbursts.

Pastoral teams should be vigilant in noticing when students’ achievements are celebrated publicly, yet their wellbeing appears fragile. Inclusion teams can support by identifying students who are masking academic anxiety with high performance. This is a delicate area: teachers must be cautious not to mislabel ambition as neglect, but rather consider when ambition overrides a child’s need for rest, balance, and reassurance. This is particularly difficult, so one must take time to have all the relevant facts and the correct context.

Affluent families in Dubai may provide their children with early access to wealth, technology, or independence, sometimes mistaking this for maturity. Students may arrive at school with the latest devices, large sums of money, or share stories of unsupervised social events. Teachers should look for patterns such as students staying online late into the night, discussing adultlike freedoms, or displaying behaviour that suggests insufficient guidance. Safeguarding leads must handle this area with caution, cultural expectations of independence differ among families from diverse backgrounds.

What may appear as neglect in one cultural context might be considered normal in another. Therefore, pastoral teams must be trained to balance cultural awareness with safeguarding standards, ensuring concerns are addressed respectfully while upholding the child’s right to safety and guidance.

or dismissing wellbeing concerns

Some parents, often unintentionally, dismiss their child’s wellbeing struggles by emphasising that “everything has been provided” to their children. They will often mean, financially. In Dubai’s fast-paced expatriate environment, a student may present with anxiety, social withdrawal, or even self-harming behaviours, but parents may interpret these as temporary mood swings or over-sensitivity.

Teachers might hear comments such as: “They have nothing to worry about we give them everything.”

Here, inclusion teams and school counsellors are critical. They can provide evidence-based insights into the impact of emotional neglect, helping parents understand that material comfort does not equate to emotional security.

Addressing this requires diplomacy. Educators must avoid sounding accusatory, avoid the “wagging the finger” mentality entirely. Instead framing discussions around wellbeing research and the shared goal of supporting the child. Staff need to let the parents know that they are on their side, it is not a blame game. This is a powerful tool. The role of the DSL is to ensure these conversations remain child-focused and sensitive, recognising the precarious balance between advocacy and parental defensiveness.

Affluent neglect in Dubai is not about poverty of resources but poverty of presence. Teachers, leaders, inclusion teams, and pastoral teams must learn to identify the less visible signs of emotional and supervisory neglect while handling concerns with tact and care.

Misinterpretation is a real risk, especially in a city shaped by cultural diversity, busy professional lives, and reliance on domestic staff. Therefore, safeguarding must be approached with genuine care, professional curiosity, and respect for family contexts.

With the designated safeguarding lead guiding the process, schools can ensure that children are not only academically successful but also emotionally safe and supported. Educators need to see past the luxury items to make sure that these material things are a surplus and genuine show of love and care from a wealthy family and not a replacement for love and care. ◆

Shane Daly is an Irish educator and head of humanities at a private international school in Dubai. A trained educational coach and COBIS peer accreditor, he supports schools worldwide through their compliance and accreditation process.

“ We have found Cambridge Insight data helps us develop informed teaching and learning interventions before the start of each Cambridge course. This has led to better results in Cambridge exams.”

Jackline Aming’a, Head of School, Oshwal Academy Mombasa, Kenya

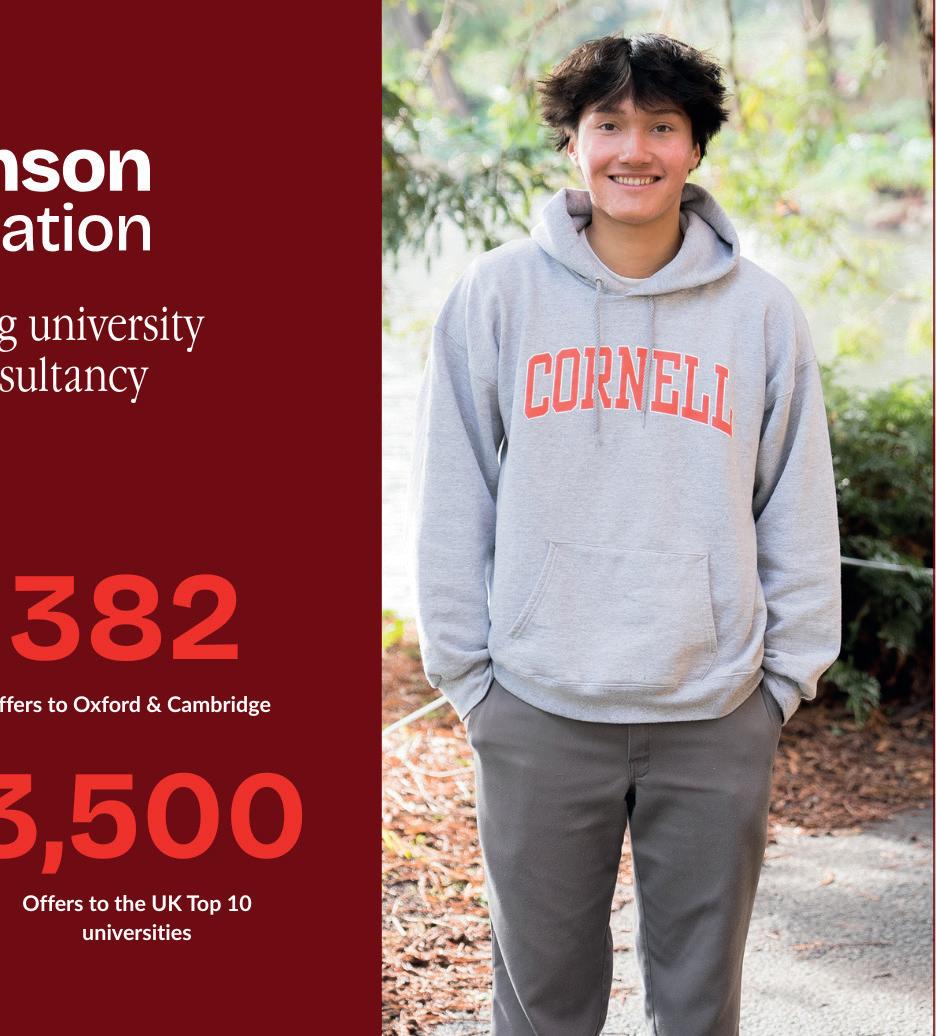

In recent years, increasing numbers of students from across Europe have set their sights on Oxford and Cambridge. Drawn by the universities’ academic prestige, global reputation, and strong graduate outcomes, they are entering one of the most competitive admissions landscapes in the world. Yet Oxford’s latest admissions report shows that offers to EU students have dropped to just 3.2%, making an already competitive process even more challenging. European students find themselves competing with peers from the UK educated in schools offering extensive Oxbridge-specific preparation.

For international schools in Europe, this raises an important question: how can teachers and counsellors help level the playing field? Beyond top grades, Oxbridge admissions officers consistently seek evidence of intellectual initiative, curiosity, and the ability to think independently – qualities sometimes summarised as an applicant’s academic character. Cultivating this takes time and strategic planning.

Academic character can be developed across three main areas:

1. Subject-Knowledge Extension

Students should be encouraged to extend their learning to confirm course choices or explore potential alternatives and academic niches, to deepen their knowledge and mastery of core academic subjects, to develop and demonstrate initiative and intellectual curiosity, and to show readiness to compete and succeed in university.

2. Independent Research and Projects

Competitive applicants often undertake self-authored research projects – whether a scientific investigation, economic analysis, or philosophical essay – sometimes culminating in publication in youth academic journals or submissions to university-led essay contests. These projects demonstrate intellectual ambition and the ability to engage deeply with a chosen field.

3. Competitions and Academic Challenges

Students should begin entering prestigious contests such as olympiads, essay

competitions, or the European Youth Parliament from as early as Year 10. Starting early allows them to develop their skills, refine their approach, and build towards winning results by Year 12. Success in these competitions not only strengthens their academic profile but also provides rich material to discuss during Oxbridge interviews.

Supporting students across all these areas can be challenging, which is why Crimson Education’s team of former admissions officers and top-university graduates provides holistic application services that cover every stage of academic character development. We help students start early, ideally by Year 10 or 11, guiding them through subject extension, research mentorship, and competition preparation in a structured, tailored way. Integrated with academic planning, personal statement guidance, and interview readiness, this approach ensures students present both academic excellence and the intellectual character and ambition Oxbridge demands. ◆

Being a truly inclusive international school takes bravery and very careful thought, write Anita Gleave and Clemmie Stewart

‘Inclusion’ has become one of the buzz words of the post Covid world – tagged by governments and organisations with vigour and yet we pose the question: Are we actually brave enough to not just talk true inclusion but to deliver it, in a meaningful sustainable way for all our children?

Do you talk openly and with pride about your inclusive culture?

Inclusion: such a seemingly simple word and concept. The state of being included. And yet, so many continue to wrestle with their definition and therefore culture of inclusion. It is something that we have always been deeply passionate about.

Having created, led and managed schools that are proudly non-selective and open to children of all talents, passions and challenges, it is not just a North Star for us;

it is a basic right. So what is inclusive education?

The language of inclusion is fraught with difficulty. Inclusion is not the same as SEND, and yet the two terms have become synonymous. Yes, inclusion means that a child or adult with SEND is fully catered for and supported, but it far transcends that. Language, culture, faith, race, all protected characteristics – everyone has a seat at our table, and everyone truly experiences a sense of belonging.

Beyond that, terminology also plays a critical role. The language used in one country, may well be seen as derogatory in another. A country at the start of its inclusion journey may use clunky terminology yet it is a powerful start and one which needs to be nurtured.

Similarly, a culture so scared of offending by using the

wrong terminology, may never get to the crux of the conversation. So, we seek to educate and to learn rather than correct. This was critically important to us when we opened the first fully inclusive schools in Dubai and then in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

someone has visibly grimaced at the idea of teaching children with additional needs. However, we also often hear that the candidate feels that inclusion is a basic right for all children; that they believe in tailoring to the individual and would relish the chance to learn more in a truly inclusive environment.

Build spaces that work for all children.

As more schools open internationally, leaders will find a myriad of skills and talents in the local market. We have been blessed to work with experts in the field of EAL and AAL, as bilingualism is really common in the Middle East. However, it has been more challenging to find colleagues already trained and experienced in inclusion.

Some interviews we have led have ended quickly when

A country at the start of its inclusion journey may use clunky terminology.

Hired!

All members of the community are welcome in our schools.

From parent cafes in Riyadh (the iced mocha has been a game changer) to translators at parents’ evenings, we have worked consistently to ensure parents feel valued and included in the process.

Not only are they the “customer”, but they are also the biggest and best resource in truly understanding their child. So, building powerful trusting and inclusive relationships is key.

Build spaces that work for all children. Bright, open glass spaces in the heart of the school where children an self-regulate, rather than dark corridors at the edge of the school, both physically and metaphorically. F

Interviews have ended quickly when someone has grimaced at the idea of teaching children with additional needs.

Warm, welcoming colours with minimal distraction, rather than primary colour explosions from ceiling to floor. Subtle sound mufflers on the ceiling, clever use of colour for wayfinding, flexible seating and standing solutions –all of these offer ways to make a learning space more inclusive without having to shout it from the roof tops. Inclusive means it works for all.

Don’t hide your inclusion for fear of alienating some families

– if they don’t like inclusion, they won’t like your school. Be ok with that! We have always shared our inclusive nature at every stage, and with pride. Do your socials celebrate all of your children? Does your website? Do you talk openly and with pride about your inclusive culture?

To be truly inclusive, you need buy in from all of your community and you can only do that if you are crystal clear

about what you are and who you are.

Inclusion is not for everyone. Not all children can access an inclusive education and indeed require more acute provision. Inclusion is a parental choice. Inclusion is not a gimmick, a tick box exercise to hide behind when the inspectors come calling.

True inclusion requires investment, training,

communication, dedication and passion. It requires honesty and transparency. As our children learn and grow in this every changing world, we know that schools will need to be more inclusive, more innovative and more flexible. Are you brave enough to accept the challenge, to truly change and truly deliver for all our children? ◆

Anita Gleave has enjoyed almost 40 years in the independent school sector. From teacher, head, principal and director, she founded Chatsworth Schools in 2018 and then Blenheim Schools during the Covid pandemic.

Clemmie Stewart has worked cross sector, enjoying a variety of leadership roles including head, senior head, executive principal in Saudi Arabia and director of learning and teaching for Chatsworth Schools.

Dr Helen Wood interviews Dr Eowyn Crisfield, founder and Director of the Oxford Collaborative for Multilingualism

ith shifting demographics reshaping student bodies, admissions testing practices in international schools are under scrutiny. For learners with English as an additional language (EAL), the stakes are particularly high. Yet Dr Eowyn Crisfield, believes many schools rely on measures that fail to reflect the true potential of these applicants.

The limits of monolingual metrics

Schools tend to default to using cognitive ability tests normed for monolingual English speakers. “These tests don’t take into account that English language learners are taking the test in their second language,”

Crisfield explains. “They are naturally disadvantaged – and cultural bias makes that worse.”

Attempts to ‘fix’ the problem by extracting non-verbal reasoning scores are, she cautions, only partially effective. “The question is, if we know the data is not a true reflection of these learners’ ability, how can we interpret it to inform good decision-making?”

Selection pressure and shifting standards

Crisfield notes that the problem is two-fold. “Selective schools risk overlooking talented learners at earlier stages of English, or admitting stronger English users with lower academic aptitude, simply by misreading what their tests measure,” she says.

On the other hand, market realities are adding pressure, with less selective schools lowering their minimum English thresholds.

“If you do that, without adapting your assessments and putting the right support in place, you are setting students up for an inequitable experience from day one,” she warns.

The learner’s perspective: stress, bias and self-esteem

The human impact of misaligned testing is significant. “If I’m forced to sit an ability

test in a language other than my own, I know I’ll do poorly,” Crisfield says. “That knowledge creates stress, which further undermines performance.”

Cultural bias compounds the problem.

“Unfamiliar expectations make tasks harder – especially under time pressure,” she explains. “It’s a direct hit to the learner’s confidence, motivation and sense of belonging.”

Her position is unequivocal: “If you feel you must use such tests for admissions, fine – but once the student is in your school, there is no justification for using culturally and linguistically inappropriate measures. Better tools exist.”

Towards fairer, more meaningful assessment Crisfield is realistic about the complexity. “There is no quick fix. EAL learners are highly individual, and any assessment strategy has to reflect that.”

Her recommendation: ensure decisionmakers understand how admissions data for EAL learners differs from that

of monolingual speakers of English, and pair that with an accurate measure of academic English language proficiency.

“Not a general EFL test – but one specifically designed to assess curriculumaccess language – which is good news for Password” she adds with a laugh, “because that is exactly what you do.”

“With reliable language proficiency data, alongside your other measures, schools can make fair, informed admissions decisions and start from a clear baseline.” ◆

Find out how Password supports international schools with fairer admissions decisions: www.englishlanguagetesting.co.uk contact@englishlanguagetesting.co.uk

Dr Helen Wood is Head of School Partnerships at Password English Language Testing

The real strength of a school visit lies not in the destination, but the people we forge relationships with on the way, writes Tom Penny

In the landscape of modern education, school trips often straddle a fine line between enrichment and afterthought. With budgets stretched, logistics complex, and curricula increasingly packed, the temptation is strong to default to safe, efficient itineraries.

But when international travel is approached with intentionality – when it’s designed around relationships, not just landmarks – it becomes a powerful learning engine for both students and educators. Through our global travel programme, we aimed to promote local connections.

The key to transformative travel isn’t the destination. It’s the people: the peers you plan with, the teachers you grow alongside, the locals who welcome you in. It’s a journey forged not on paper, but through collaboration, connection, and community.

My school, the International School of Stuttgart in Germany, has embraced this approach through Erasmus+ funding, which has allowed us to design a programme of annual student mobility alongside a strategic commitment to teacher professional learning.

By integrating student experiences with staff development visits, we’ve been able

to build authentic relationships across Europe, deepen our understanding of European identity and civic life, and place human connection at the heart of our learning journeys.

over places

When schools prioritise who students meet over what they see, trips move beyond tourism and become transformative.Visiting an iconic museum can be meaningful. But talking to the curator? Collaborating on an art project with students from a partner school? Sharing a meal with a host family? These moments leave lasting marks on identity and understanding.

By anchoring trips in human connection – through long-standing partnerships, cultural exchanges, and community projects – educational travel becomes deeply personal. It’s not about ticking off monuments. It’s about being welcomed into a story and becoming part of it, however briefly.

Through Erasmus+, we’ve cultivated these long-term relationships with schools and cultural organisations in multiple countries, allowing for real collaboration and continuity from one

year to the next. These aren’t one-off visits – they’re evolving partnerships built on mutual learning.

Teacher development through co-design

Trip planning is often seen as a logistical chore, but when reframed, it becomes professional development in its richest form.

When educators collaborate to design trips – not just supervise them – they engage in deep, reflective work. They research contexts, align learning goals, anticipate challenges, and weave in moments of student voice and choice. This process builds interdisciplinary thinking, logistical problem-solving, cultural literacy, and strategic visioning.

We’ve used Erasmus+ to support staff travel and training that feeds directly into trip planning and curriculum design. Teachers gain firsthand insight into the places we visit – whether through attending a preparatory meeting, visiting cultural institutions, or engaging with local NGOs. They return better equipped to embed European perspectives in their teaching and to lead students into deeper learning. Moreover, when teachers co-create

The temptation is strong to default to safe, efficient itineraries.

itineraries with their colleagues, they build stronger professional bonds. They learn from each other’s approaches, draw from each other’s networks, and develop a shared language around experiential learning. These relationships strengthen school culture well beyond the trip itself.

Students as partners

Involving students in the planning process isn’t just a nice touch – it’s a critical learning opportunity. When students help shape the goals, themes, and content of a trip, they build ownership, motivation, and leadership.

Working side by side with teachers and peers to co-design learning moments –identifying relevant local contacts, curating site visits, developing questions to ask on the ground – blurs the line between learner and educator.

It cultivates confidence, initiative, and a deepened sense of responsibility. These relationships – among students, and between

students and staff – elevate the school culture and foster a sense of shared purpose.

In fast-paced school life, international trips offer rare and valuable opportunities to slow down and reflect together. When schools allow for moments of lingering, listening, and being present, they create space for relationships to form organically.

Teachers, too, benefit from this reorientation. In travel, traditional hierarchies soften. Teachers and students navigate unfamiliar environments together, face the same uncertainties, and celebrate the same discoveries. Trips also have the power to improve staff relationships across departments in a school.

Even the most meticulously planned trip will meet the unexpected. Trains get delayed. Local sites close.

In these moments, it’s relationships that matter most. A well-connected local partner might suggest a powerful alternative. A colleague might offer a thoughtful pivot. A student, invested in the experience, might propose a plan B that’s even better than plan A.

Flexibility isn’t a flaw in educational travel – it’s a feature. And when schools have human connections to fall back on, they can turn disruption into discovery.

Community links that last

One of the most under-leveraged opportunities in educational travel is its power to strengthen school–community connections.

Trips shouldn’t be siloed events. When students and staff return, they bring back stories, relationships, and ideas that can enrich the broader school community. Connections made abroad can evolve into virtual exchanges, joint projects, or even broader institutional partnerships. Families, too, can be engaged – through language nights, photo exhibits, or shared celebrations of what students learned.

By highlighting the human stories that emerge from trips, schools inspire the whole community to think more globally and to feel more connected.

How school leaders can make trips more relational

• Centre relationships in planning. Make people, including partners, peers and mentors the backbone of every itinerary.

• Frame planning as PD. Recognise and support teachers’ time and effort as vital professional growth.

• Use Erasmus+ or other such funding strategically. Blend student mobility and teacher learning in ways that reinforce each other.

• Encourage community contributions. Invite staff and students to use their own networks to enrich trip design.

• Value flexibility. Empower staff to pivot based on local knowledge and emerging opportunities.

• Celebrate the ripple effect. Use trip experiences to inspire school-wide projects, exhibitions, or service initiatives. ◆

Tom Penny

upper school assistant principal at International School of Stuttgart.

The tricky task of leading a British international school abroad offers perspective, agility, and insight, writes Carly

Barber

Ask any UK headteacher to describe their role and you’ll likely hear a familiar set of themes: safeguarding, standards, staffing, and the occasional fire alarm incident courtesy of Year 9 mischief.

It’s a demanding job, requiring thick skin, quick thinking and deep reserves of empathy. But for those who step into headship at a British branch international school, familiar challenges take on new shapes. It’s still headship, but in a different climate, figuratively and literally.

And increasingly, it’s becoming part of the landscape. With more UK independent schools branching out overseas, international experience is no longer seen as an unusual career detour. In fact, it’s fast becoming a feature on the CVs of many future heads.

A stint abroad offers perspective, agility, and insight into the evolving expectations of globally minded families, insight that is just as relevant back home as it is in Dubai or Ho Chi Minh City.

Leading a British international school, especially one carrying the brand and ethos of an established UK name, is a delicate act of translation. You’re expected to uphold tradition while reinventing it. The curriculum might be recognisably British, but the operating context rarely is.

You’re managing expectations across cultures, time zones, and economic models. It’s a role that rewards clarity, patience, and a fairly welldeveloped sense of humour.

You’re expected to uphold tradition while reinventing it.

One of the first surprises for many heads making the leap is governance. In the UK, heads tend to report to a single governing body with a shared understanding of what school improvement looks like. In the international branch world, you’re often accountable to several stakeholders at once: a UK board focused on brand fidelity, a local proprietor with commercial priorities, and your in-school leadership team juggling day-to-day realities. Aligning these layers isn’t just a structural exercise, it’s about building trust in multiple directions.

There’s no manual for this. Cultural understanding isn’t about knowing national holidays or avoiding faux pas. It’s about learning how things really work. How do people give feedback? What does “academic success” mean to families here? Who actually makes the decisions? You won’t always get it right, but people notice when you’re genuinely trying.

You’re holding a legacy, but you’re also shaping something new. A strong house system, a chapel-style assembly, a commitment to co-curricular excellence, these can travel well, but they need to land authentically. Nostalgia won’t carry you far. What matters is making the founding school’s ethos mean something in its new setting.

Heads need fluency in financial language not just to steward resources, but to make a case within a business-first framework. Ironically, as VAT changes and increasing financial pressures reshape the independent sector in the UK, that experience may soon become just as relevant at home.

When you’re far from home, presence becomes more than symbolic. It’s stabilising. Staff want to see their head in the corridors. Families want to feel heard.

To thrive in this space, some specific skills become essential.

Many heads in the UK independent sector are already adept at managing large budgets, balancing long-term investment with short-term constraints, and working closely with finance directors.

But in most British branch schools abroad, the business model is different, and so is the chain of accountability. Here, the school operates as a commercial enterprise, often with the head ultimately reporting into a regional CFO or owneroperator group.

That shift matters. It can reshape priorities, timelines, even definitions of success. Many heads describe this shift, from teaching and learning into prioritising strategic business decisions made by the board, as one of the most significant adjustments they’ve had to make.

And students want to know you’ve noticed. A leader who takes time to learn the cleaner’s name or remember the backstory behind a Year 13 UCAS application builds credibility the long way round. But it lasts.

Things shift quickly in this world. Visa rules change. Inspection frameworks change. Even proprietors change. If you’re looking for certainty, you might be in the wrong profession. The best international heads respond with calm, adapt plans without panic, and give their teams space to breathe.

Of course, there’s also the question of longevity. Founding heads are sometimes seen as the “set-up” people, brought in to launch and then expected to hand over. That doesn’t suit everyone. But for those who want to build something meaningful, from scratch, in partnership with a local team, it can be the most professionally fulfilling phase of a career.

One colleague recently joked that they’d acted as a translator, therapist, and tour guide before their first cup of coffee. Another described the moment a local student got an offer from a top UK university after years of cross-cultural mentoring. These aren’t just anecdotes, they’re reminders of the purpose behind the pressure.

So what advice would I offer someone considering the leap? Stay curious. Stay grounded. Don’t try to be the UK head abroad. It’s not about replicating a British school in a sunnier location. It’s about leading something proudly different, drawing on what works, and letting go of what doesn’t.

This kind of headship isn’t for everyone. But for the right person, at the right moment in their career, it’s more than just a challenge. It’s a transformation. ◆

Carly Barber is head of college at Brighton College Vietnam. Previously, she was head of senior school at Brighton College Bangkok and at Southlands International School in Rome, Italy. She is currently finishing her doctorate at UCL looking at the relationships between governing bodies and heads in British branch schools.

Denry Machin looks at the pitfalls of opening a new international school - and what you can do to prevent major mishaps

Iwas recently asked what can go wrong when opening a new international school.

My answer? Something will go wrong. Something will be forgotten. Something will be missed. It’s not a matter of if, but what.

Opening a school is complex. Recruitment, marketing, construction, procurement, admissions, and educational design all need to align, often through a newly formed team, many of whom may be unfamiliar with the country or context.

It’s no surprise, then, that nobody – regardless of what

they might claim – ever has a perfect opening. There are delays. There are mistakes. However hard everyone works, something will go wrong, something won’t go to plan.

I’ve seen openings where:

• The group director of education was painting corridors the night before a

school opened and the paint was still wet as students arrived.

• A drop-off zone was built with too little height clearance for the local minibus fleet (which admittedly ran taller vehicles than standard).

• Staff housing was in a newly built city district where

power was often cut on weekends in favour of downtown malls. As you c an imagine, this was deeply unpopular.

• A delayed order meant boarding staff had to rush to IKEA for sets of bedding…and were still quickly making up beds as parents and children F

Nobody – regardless of what they might claim – ever has a perfect opening.

The group director of education was painting corridors the night before a school opened.

arrived in the dorms. (Yes, students could have done this themselves, but unmade beds is a bad look on day one).

• No one had remembered to order lanyards for ID badges. A small thing, but a very visible miss.

Snagging issues happen everywhere. But these, quirky as they are, aren’t even the most serious. With raised eyebrows suggesting that my questioner wanted a better answer, I offered four key risk areas:

Construction delays

Anyone familiar with international school openings will be aware of delayed starts: sometimes by days, sometimes weeks, occasionally months. While the delays themselves may be short-lived (and often mitigated by parental goodwill and the efforts of industrious staff) the long-term damage to a school’s brand can be far more enduring.

Design oversights

Architecture is part science, part art – and both can

go wrong. Classrooms are undersized. Meeting rooms are too few. Storage is underplanned. Specialist spaces –for learning support, speech therapy, etc – are forgotten, especially if needed only occasionally. And sometimes style is put before substance; architectural flair, whilst important, can impede function.

Capital is tight, of course. But too many rooms is almost always better than too few, giving flexibility for future growth and unpredictable student needs. Yet, whatever the budget, form should follow function.

Staffing gaps

No-shows. Mis-hires. Vacant roles. These are common everywhere but in start-ups, the scale of hiring, the highstakes nature of roles, and the speed of change make the impact far greater.

Regulatory delays Licensing. Visas. Building permits. Customs clearance. Any one of these can delay a staff member, a shipment, or

• Appoint experienced architects, even if they aren’t the cheapest.

• Choose reputable contractors and project managers, not just the lowest bidders.

• Hire early and generously. Give staff time to plan, settle, and to ask: “Have we thought of…?”

• Treat regulatory compliance as a senior role. In the pre-opening phase, they may matter as much as the principal. Plan and pay accordingly.

• Not all stakeholders will be on the same page about what the school will look like, or what’s realistic given the budget. Communicate expectations clearly, and check for shared understanding – both theirs and yours.

a building, sometimes fatally for your opening timeline.

There are other risks, of course. If pushed, I’d throw delayed resource orders into the mix too (though, annoying as they are, these can often be worked around in the short term and are unlikely to delay or significantly disrupt the opening). However, those above are perhaps the most common and the most significant; they are the ones which have derailed the most openings.

For any investor, school, or founding head, the obvious next question is:

those risks?

The answers are simple (if not easy): money, planning, and communication. Schools that “open well” tend to:

In short, if you try to open on a shoestring and in a rush you risk ending up with a school held together by string. Even if it does get off the start line on time (and it probably won’t), it may trip, falter and stumble soon after.

There’s more, of course –much more. Opening a new school is a major undertaking. The only real question is whether the things that go wrong for your project will affect the opening. Risks can be mitigated but not eliminated.

And that, too, is part of opening well: your founding team and your founding parents need to understand that it’s not a matter of if, but what. In that sense, it’s wiser to under-promise and overdeliver. Better to open small and solid than large and struggling. ◆

Dr Denry Machin is a former head of seniors, a consultant, author, and university lecturer. He specialises in international school startsups and project management. Contact him on denry@pedagogue.ac

Cheryl Shirley explains how her trust’s digital strategy and use of platforms like Nearpod has led to engaged children, improved behaviour, greater inclusion and substantial e ciencies.

“It’s necessary for people like me, but it helps everyone,” says Freddy, a pupil with SEND explaining in a nutshell why his primary school’s embrace of digital learning is so important and why it’s such a hit with children, teachers and parents.

Six years ago, LEO Academy Trust, of which Freddy’s school is a part, decided to embark on an ambitious digital strategy by giving every child in Year 3 and above a laptop and investing in a range of digital tools including Nearpod, an interactive classroom platform that uses quizzes, polls and videos to make lessons more engaging and provides instant feedback for individual students.

The trust’s motivation was straightforward: to help pupils thrive in a world where digital literacy skills were becoming indispensable. But an additional benefit of its strategy soon became apparent – the boost it delivered to children with SEND.

Equipping every child with a laptop and specialist software means dyslexic and autistic pupils, for instance, can access lessons alongside their peers, all of whom are engaged on class or individual tasks, and all of whom receive instant feedback from their teachers via Nearpod.

“Our digital approach has given those with SEND not only the tools they need but also the confidence they’ve needed,” says Cheryl.

“And it’s taken away a lot of the stigma. This group of pupils don’t stand out because they’re not supervised by a dedicated adult or sat with a separate group. They’re not seen as different in any way.”

As a result, despite the high levels of need still entering the trust’s schools, the number of LEO children on the SEND register has actually decreased, in stark contrast to national trends.

Behaviour, too, has improved. “The minute I introduced digital learning, behaviour improved massively. Why? Because every child in the room had the tools they needed to succeed. They weren’t disengaged or frustrated.”

Cheryl says another clear advantage of Nearpod is that it’s very easy for teachers to use and allows them to use their own material more effectively. “Now a question can be put to the whole class and answered by every child on their device, not just the usual three or four confident ones who put up their hands.”

Marking is done instantly, with teachers able to see if the class is struggling with particular questions, or only certain children are.

The impact the data provided by Nearpod makes is “massive”, says Cheryl, both at a class and trust level. “For teachers it means they can see what children have and haven’t understood so they can focus and target their teaching much more accurately and efficiently. At a trust level we can see trends in year groups or classes, which feeds back into our curriculum planning.”

Nearpod’s user-friendly features meant teachers quickly bought into LEO’s digital strategy, explains Cheryl. “They saw that so much could be done – how children were getting on, who needed help with a click of a button. Those sorts of quick efficiencies in the classroom have just been really powerful. They were instantly impactful.”

Cheryl Shirley, Director of Digital Learning, LEO Academy Trust.

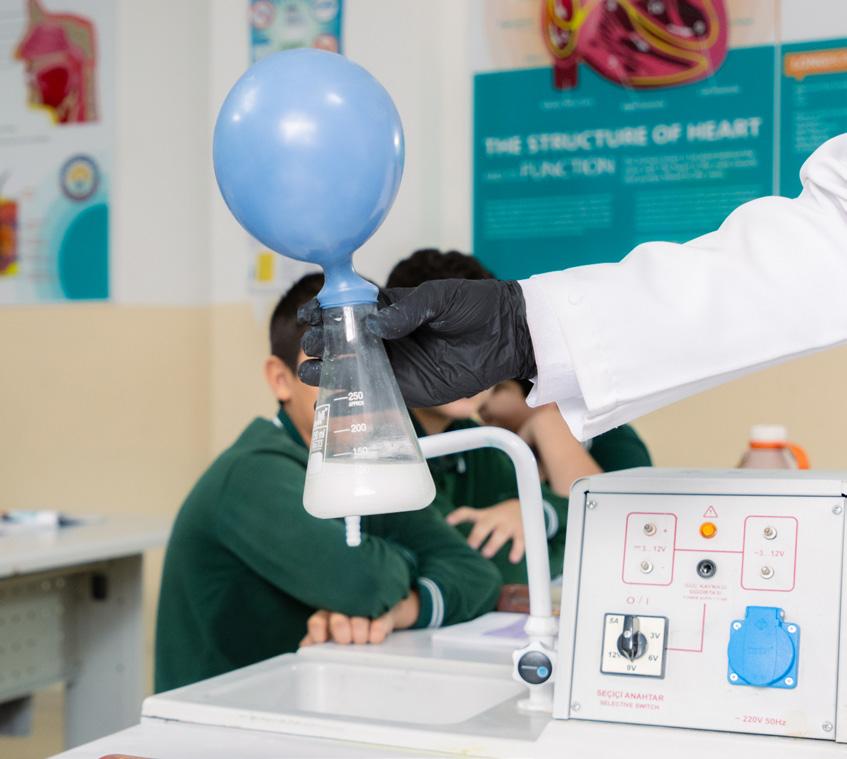

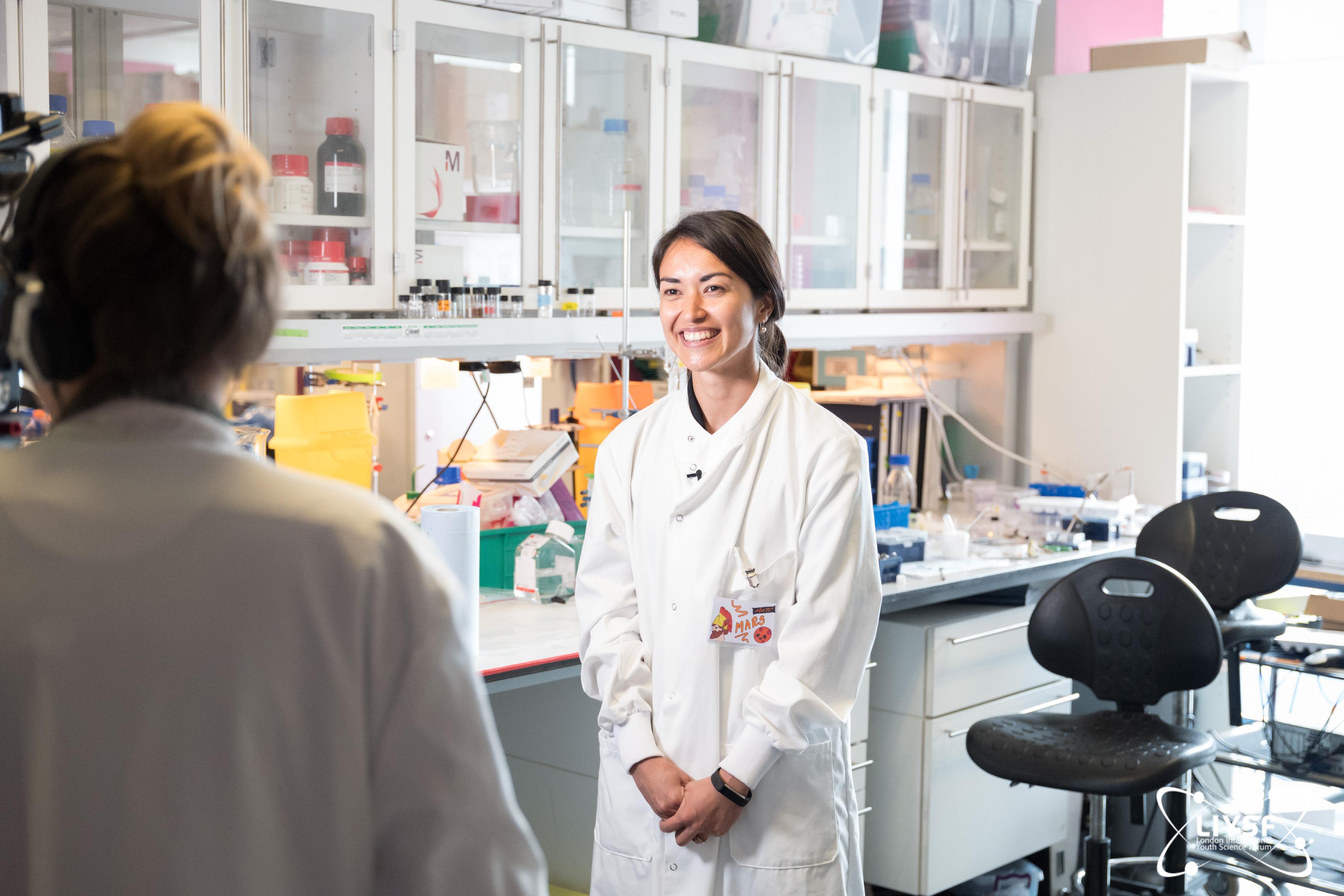

Launching a British-branded schools network in Iraq has been an incredibly rewarding challenge – but it’s all about the students – writes Timothy Fisher

In 2018, following nine months of due diligence, Stirling Education began a transformative journey with the acquisition of two portfolios of schools and universities: one in Iraq, the other in the Western Balkans.

As a result, we acquired more than 40 schools and two university campuses across six cities in Federal Iraq and the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI). The Western Balkans portfolio included 12 schools and a university in Sarajevo.

Since then, we have also invested in schools in Egypt and Bangladesh and today, Stirling Education owns and operates 60 educational institutions, from nursery to university. With more than 3,000 staff, Stirling educates some 27,000 students, including 7,500 at university level.

Among these ventures, the work in Iraq remains perhaps the most challenging, and the most rewarding. This is the story of that journey and the remarkable young people whose futures make every investment worthwhile.

To understand the scale of the challenge,

one must first appreciate the context. Iraq has faced profound and prolonged instability. The Syrian civil war following the Arab Spring in 2011, and the rise of ISIS between 2014 and 2017, displaced millions within and beyond Iraq’s borders.

The economy is almost entirely dependent on crude oil exports, which account for around 95 per cent of government revenue. When oil prices collapsed in 2015–16, national income plummeted. Inflation, currency volatility, and political uncertainty followed. The Iraqi Dinar was devalued in 2020, and in 2024 the use of US dollars in local transactions was banned outright. Tensions between Federal Iraq and the KRI added further strain, with local authority budgets under pressure and public sector salaries often delayed for months.

Despite this backdrop of economic difficulty and population displacement, the opportunity, while not without risk, was clear. Across major Iraqi cities there was a cluster of schools – some longestablished, others newly built but under capacity – all under financial strain to

varying degrees. While many faced cash flow issues and inconsistent curricula, our due diligence revealed a single, compelling constant: the students.

Iraqi students are intelligent, curious, and eager to learn. Throughout modern history, including under Saddam Hussein’s regime, Iraq has produced exceptional scientific and academic minds. This cultural respect for education remained strong but underserved by both state and private sectors. Even as the country lurched from one crisis to another, the research showed a consistent demand for high-quality learning with international standards.

Half the population is aged 16 or younger. Despite a shrinking middle class, Iraq remains in the upper-middle-income bracket. State schools, underfunded and overcrowded, often run double shifts, delivering only the most basic curriculum. Parents were ready to pay for stability and quality – provided the offer was both credible and affordable.

Given the market potential, a long-term view was adopted: education outcomes first, financial returns second. A British-

branded network was launched – Stirling Schools – layered over existing campuses in Baghdad, Basrah, Erbil, Kirkuk, Sulaymaniyah, and Duhok. We rapidly integrated digital learning, equipping every classroom with 4K smart boards. British curriculum elements, including Cambridge University Press resources, were introduced, and several schools sought British Schools Overseas (BSO) accreditation.

A centralised, agile management structure oversaw finance, risk, marketing, technology, and pedagogy. For local recognition, city-branded schools remained part of the portfolio, but we brought consistency in quality assurance, branding, and the deployment of scalable education technology across the group.

Academic excellence and reputation

Results came quickly. Iraq’s university entrance examinations – the Wezary –are fiercely competitive. Each year, Stirling students rank among the top five to 10 nationally. In 2025, the four highest-ranking students in the entire country all studied at our schools in Baghdad and Kirkuk, each achieving 100 per cent in all subjects.

Many alumni progress to study biomedical sciences, law, or engineering, both within Iraq and abroad. Our alumni include one of only two female surgeons in the country.

The work in Iraq remains perhaps the most challenging, and the most rewarding.

Our schools have become places of ambition and aspiration, not only for pupils but for the wider community. Stirling students have represented Iraq in competitions across Europe, the USA, and Australia, offering the world a new narrative about Iraqi youth: one of brilliance, resilience, and creativity.

At the heart of our work lies the belief that education must serve society as well as the individual. Stirling Education is proudly secular, welcoming students from all religious and ethnic backgrounds. We offer scholarships to the children of shaheed – those who lost their lives fighting ISIS – and operate two charitable schools in Halabja, the site of the 1988 genocide during the Iran Iraq war.

At Darashakran refugee camp, trainee teachers from Tishk University provide education to displaced Syrian children. In Duhok, our faculty delivers vocational training in IT and English to Yazidi women, a community still recovering from ISIS atrocities.

Our work is regularly recognised by the governments of both Federal Iraq and the KRI, with ministers of education and higher education attending our annual International Conference on Education & Teaching forum. Partnerships with the UK Government have also been instrumental. The UK recognises that quality education

underpins economic growth, social stability, and political confidence in post-conflict nations. Through collaboration with UK embassies and consulates, British values –the Nolan Principles of integrity, inclusion, and accountability – are embedded in our school ethos.

One of our greatest challenges has been teacher recruitment and retention. Regional instability makes attracting international educators difficult. We therefore invested in developing local talent.

The UK Teachers Academy (UKTA) offers scholarships and postgraduate training through Tishk International University, combining rigorous CPD with mentoring. Hundreds of new teachers have been trained through UKTA, many of whom are now community leaders as well as educators.

While we continue to recruit internationally – from the UK, South Africa, and New Zealand – our homegrown teachers form the backbone of our schools, their pride and ownership driving outstanding student outcomes.

The story of Stirling Education in Iraq is one of conviction: the belief that even in the most challenging environments, education can create stability, opportunity, and the promise of renewal. Each year in Iraq, we educate more than 11,500 pupils in schools and over 7,000 students in our universities.

Our growing alumni network, now working across government, healthcare, education, and industry, stands as a testament to the lasting contribution Stirling Education is making to Iraq’s future. ◆

Timothy Fisher is global CEO and investment manager at Stirling Education.

From the stock exchange to international school leadership via SOAS, Mike Lambert has followed a varied path to his latest big role

When Mike Lambert began his career at Barclays on a business leadership programme in the early 2000s, he was already doubting if the world of spreadsheets and stock indexes was for him.

“I knew I didn’t want to be a stockbroker,” he says, acknowledging the family expectation to follow in the footsteps of his stepfather. “The dot-com bubble had just burst, and my time at Barclays confirmed what I thought in the first place.”

What followed was an unconventional route into teaching, which started with a master’s in social anthropology at SOAS University, researching the Uyghur of Xinjiang Province in China.

Through this, he got into private tutoring and, as an Oxford classics graduate, worked for Oxbridge Applications.

“It didn’t feel like work, I was excited to be paid to work with young people,” he says.

That initial joy of shaping young minds would eventually grow into a successful career in teaching and leading, culminating in his current role as director of education at Inspired Education Group. A global network of around 120 international schools, they offer a mix of British, American, IB and local curricula to suit local demand.

I had a terrifically talented senior leadership team and they were all super hungry to deliver on their initiative.

After a series of UK-based posts, including the role of head of classics at Bedales School, Lambert’s decadelong tenure as head of Dubai College, from 2015 to 2025, marked a career high point.

Under his stewardship, the school experienced record exam results, over 30 per cent growth, and a successful fundraising campaign towards a complete campus redevelopment.

But his biggest lessons in leadership stemmed from the challenges of change management.

He says: “I had a terrifically talented senior leadership team and they were all super hungry to deliver on their initiative, their area, so I set up this ambitious vision to be leading British education overseas. What does that look like, what would it look like if we were literally leading?

“Unfortunately my senior team took me at my word…there was one year I remember three members of the SLT were all launching massive change initiatives and you could see that it was far too much for the teaching staff, who were always incredibly on board.

“So for me, it’s all well and good growing and developing your team and giving them the space to run with their ideas but you’ve got to co-ordinate change in a manageable way so it doesn’t become too overwhelming for those who effectively you are asking to deliver it.”

Another key takeaway from his time at Dubai College is that visibility matters. During the Covid lockdowns, when many schools struggled to maintain F

Getting into these schools is the nuts and bolts of who we are.

cohesion, Lambert committed to writing a daily message to the school community, what turned out to be 67 messages in all.

“At a time when we were completely atomised as a school community, this single thread of communication helped manage frustration, upset, and in some cases, tragedy,” he says.

Inspired

The next step for Lambert was clear: to move from running one excellent school to shaping a whole system of them. During the pandemic, he completed an MBA in educational leadership at UCL’s Institute of Education, focusing on multi-academy trust models and system-wide thinking.

He says: “The whole premise was that single-site schools were becoming a thing of the past. Schools were joining groups – state or private – and I wanted to be part of that evolution.”

The next step for Lambert was clear: to move from running one excellent school to shaping a whole system.

The name Inspired kept surfacing. “I kept hearing stories about Inspired’s rapid growth and reputation. Eventually, I was headhunted.” Now, as director of education, he is at the heart of one of the fastestgrowing premium school groups in the world.

Lambert describes himself as a “knowledge broker” –connecting best practices across Inspired’s schools in 28 countries.

“I spend a lot of time recruiting heads for existing and future schools, but more importantly, I’m focused on quality assurance and professional development,” he says.

Since joining in January, Lambert has been focusing on a range of light-touch initiatives to quality assure teaching standards and consistency across the group. These include better systems for tracking and comparing data across the group, “peer-led knowledge sharing” and “Inspired U”, an online platform for professional development tailored to teachers’ individual needs.

Lambert’s schedule now is a mix of work at Inspired’s headquarters in London and a rollercoaster of visits to its schools around the world.

“Getting into these schools is the nuts and bolts of who we are. You see fantastic teaching, and it bubbles

up ideas that the whole group can learn from,” he says

And how does he feel about working for a large for-profit group? The model often draws scrutiny, but Lambert remains unapologetically pragmatic.

“Inspired couldn’t be as successful as it is if we weren’t delivering something parents genuinely want. In many countries, there’s limited state provision, so parents seek quality alternatives. We’re offering a premium product – and it’s growing because it’s working.”

Now based on the English South Coast with his family, Lambert jokes that dinner conversations are a “busman’s holiday.”

“I spend my day looking at schools and then spend my evenings asking my own kids how their school day went.”

Lambert has been a keen sailor since taking it up in Dubai, but he’s held off buying a boat because of the British weather. In what some might view as a worse option, he now leaps into the icy waves with a windsurf.

“It’s the purest form of sailing,” he says, “Bareable in a wetsuit.” ◆

Irena Barker is the digital editor of School Management Plus. She also works as a freelance journalist and copywriter specialising in education.

Hugh Martin from recruitment experts Anderson Quigley looks at what teachers and school leaders should consider before deciding to work abroad

Before you engage other considerations (the culture, society, way of life), there are some immediate factors to weigh up:

Contract: is it fixed, variable, open-ended? Will you have any job security? Are certain benefits realisable only on completion of your contract, or a number of yars?

Relocation: what package is included?

Cost of living: how expensive is it to live in your destination country?

Travel: will return travel to your country of origin be covered? If so, how often? At the end of your contract? Annually? Is travel for

your partner, family, or dependents included?

Here are some notes from my own experience:

Contract: check your residency visa status. Find out about your rights. Try to discover if your contract (including salary) is market equitable where you’re heading. Don’t assume there will be any trades union or other representation.

Relocation: check what you can and can’t take. You may be surprised at what is and isn’t allowed in some countries. If in doubt, err on the side of caution and don’t trust unofficial advice. If you have pets, factor this in because it can get messy and expensive.

Cost of living: check the price of basic foodstuffs, utilities, rent, internet, insurance, car, fuel, and school fees if relevant. This may seem obvious but never assume. Extra bills such as airconditioning or heating quickly mount up in hot and cold climates. For example, water, electricity, and driving can be phenomenally more expensive than you’re used to.

Travel: be prepared to negotiate on airfare and tickets.

Don’t be afraid to be direct.

Polite but very straightforward questioning will often be necessary, in a manner you may not be familiar with back home. You may need to ask a number of people, and ask more than once.

The HR director at the school to which you’re going should be a source of useful, inside knowledge. If you know anyone who already lives there, definitely ask them. A national will have a very different perspective than a non-national resident. Both will be useful and both should be taken at facevalue – as personal opinions.

You can never do too much research in advance. Believe me, you will be amazed at the significant impact of something as simple as unpredicted/ able bills, or the speed and functionality of your internet connection. Your salary will get gobbled up soon enough or your home life will be uncomfortable – not things you need when you’re grappling with the challenges of a new work environment.

Then there is the important question: what job are you actually going to?

This is not as easy to bottom out as some of the earlier list.

You can never do too much research in advance.

Unless you know someone who already works where you will be taking up your post, you won’t easily find the inside track. You should visit if you can and, if offered, a final interview in-country will help.

Advice for living overseas

Expect cultural unfamiliarities. Embrace them.

Mostly, whatever your interests, you’ll find common ground in someone, somewhere, in your new home. And that’s important: make it your home.

There’s nothing worse than the ex-pat crowd eating the same food, reading the same newspapers, and talking about the same things they did before they left wherever they came from.

Ex-pat should be a dirty word. This is where you work now. This is your home. You’ll be much more welcomed and engaged with by locals if you

You will need the skills which make good embassy staff, including tact and diplomacy.

take that approach. You’ll also feel less removed.

A couple more clichés: eat the local food and try to learn the language.

Unless you’re a linguist, you’ll be surprised at your own lack of ability, and you’ll be chastened at how colleagues are working in second, third, and even fourth languages more fluently than you.

Education overseas

Accept that the education sector in different countries is at different levels of maturity and experience; some more and some less than you may be used to. This means:

• Governance norms may be at odds with political and

other pressures

• Stated hierarchies, policies, and processes may be more fluid than you’ve experienced

• Rigidities and unseen boundaries may exist that you may not have taken into account

• Staff recruitment, procurement, estate management, financial reporting, legal procedures: all may operate in different contexts.

Your success will depend on your ability to navigate waters which are uncharted for you, but quite familiar to others. In many ways, you will need the skills which make good embassy staff: tact, diplomacy, a breadth of understanding beyond your home country and a willingness to appreciate and learn from your new territory, rather than dictate and impose. And like embassy staff, you are also ambassadors for the countries you left behind.

American author Clifton Fadiman wrote: “remember that a foreign country is not designed to make you comfortable. It is designed to make its own people comfortable.”

Hugh Martin is the managing partner MENA for executive search firm Anderson Quigley. He has spent 25 years in the education sector as a lecturer, teacher, senior manager, and consultant. He can be contacted at hugh.

45,000+ independent & international professionals

15,000 social media reach accross six channels

Included in weekly jobs newsletter

Standard listing PLUS

Featured listing at the top of the Careers Section

Advertising alongside relevant content throughout the site

ATTRACT THE BEST STAFF WITH THE LEADING DIGITAL PLATFORM FOR INDEPENDENT AND INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL PROFESSIONALS WORLDWIDE

School Management Plus is the leading print, digital and social content platform, for leaders, educators and professionals within the independent and international education sector worldwide.

Our readership spans every stakeholder within fee paying education worldwide from Heads, Governors, Bursars, Admissions, Marketing, Development, Fundraising and Educators – to catering, facilities and sports. Our jobs & careers center is the natural meeting point for those already in the sector, aspiring to join it, or hiring from within it.

Featured listing PLUS

Free listing if the vacancy is not filled

Included on magazine digital distribution to 150,000 readers

Included in school directory

Listing experience hosted on Kampus24

Premium listing PLUS

Unlimited job listings throughout the year to our audience

Newsletter presence every month for your school

Exposure and features on your school in main careers section

Print adverts for your listings each term

Listing experience hosted on Kampus24

The rst 100 schools to sign up will receive 20% o a year’s unlimited package

•Social following of 15k across 6channels

• 60% annual growth in web tra c

• Core readership of Heads, Senior Leaders, Heads of Department, Bursars and Finance managers, Marketing and Admissions, and Development across the sector