Celebrating 40 Years

FOUR DECADES INSPIRING NATIVE PLANTS CONSERVATION

WILDFLOWER 2022 | Volume 39, No. 2

FIGHTING FIRE WITH FIRE UNDERGROUND CAVE WILDLIFE WOMEN TREE CLIMBERS

PAGE 18

The National Wildflower Research Center’s original location opened on Mrs. Johnson’s 70th birthday, December 22, 1982. Located in East Austin at the corner of FM 973, near Martin Luther King Boulevard and Highway 71, the Center occupied 60 acres of undeveloped land owned by the Johnson family, which was also home to KLBJ radio towers. The property consisted of a caretaker’s home, the gift store, research areas, a greenhouse, a volunteer area, administrative offices and a space referred to as the Clearinghouse, where informational packets about native plants and research were assembled and mailed nationwide.

PROMISE Land

– C.M. PHOTO Wildflower Center archives

2 | WILDFLOWER

The current campus, renamed the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center in 1997, opened in 1995 on 42 acres in Southwest Austin, nine miles from downtown. Native plant gardens and landscapes, designed by J. RobertAnderson (FASLA principal), Eleanor McKinney (EMLA) and Darrel Morrison (FASLA), were installed throughout a complex of award-winning buildings designed by Overland Partners to reflect the land and regional architecture of the Texas Hill Country. – C.M. PHOTO Overland Partners

AN EXPANDED View | 3

40 Years of Growth + Progress

IT’S EASY TO GET CAUGHT UP IN LIFE’S MINUTIA — running to the grocery store; taking the kids to soccer practice; tackling the weeds in the garden; digging out from a pile of never-ending emails; fretting over which brand of toothpaste to buy (this time).

When I’m feeling overwhelmed by those activities, I like to find a meditative moment and sink into what I call “Big Time” — to expand my mind outward and consider the millions of years and people that came before me, and new generations that will come after. It puts the little things into broader perspective.

As the Wildflower Center reaches its 40th birthday, we’re celebrating our history by reflecting on the small and large ways we’ve matured and the impact that we’ve had on native plants, the environment and our ever-growing community.

In the beginning, the Wildflower Center quickly distinguished itself as a leading voice for native plants, thanks to the vision and support of Lady Bird Johnson, Helen Hayes, our first board members and early staff. Growing into our teenage years, we established ourselves as an experiential public garden in

southwest Austin and began hosting school field trips, weddings, educational programs and exhibitions. We evolved during the past couple of decades through our 20s and 30s to think holistically about larger landscapes; to develop renowned landscape research and consulting programs; to expand our gardens to serve broader audiences; and to launch programs such as SITES®, on a national scale.

Along the way, tough times taught us new lessons, and we celebrated thousands of good times, too.

As we look ahead, we’re excited about what’s to come in the next 40 years at the Wildflower Center.

Thank you for joining us to support a thriving environment for the future.

Stay wild,

Lee Clippard Executive Director

4 | WILDFLOWER FROM THE Executive Director

A Place and a Promise

For

by Pam Penick

Grounded

Through deep connection to its roots of people and plants, the Center inspires long-standing and new generations

by Melissa Gaskill

by Melissa Gaskill

ON THE COVER

The first metal mailbox at the original location of the National Wildflower Research Center in East Austin at 2600 FM North Hwy. 973, circa 1982. PHOTO Wildflower Center archives

ABOVE City of Austin

cave biologists survey a newly discovered cave at the Center PHOTO Drew Thompson

| 5 7 PLANT PICKS Our founders’ favorite plants, flowers and trees 10 BOTANY 101 Why prescribed fire is crucial to land management 12 IN THEIR ELEMENT Research shows climate change is impacting bee populations 16 HOMELAND The Wildflower Center’s land acknowledgement 34 NEWS AND UPDATES The latest on our gardens and our work 40 THANK YOU, DONORS 42 THINGS WE LOVE A few of our favorite things 44 CAN DO Apartment dwellers can plant and grow Texas natives, too 48 WILD LIFE Scientific cave exploration magnifies underground worlds 48

40 years, the Wildflower Center has evolved as a place where hope blooms

18 28 FEATURES TABLE of Contents 12 42

Melissa Gaskill writes about science, nature and the environment for a variety of publications including Mental Floss, Newsweek, Men’s Journal and Alert Diver. Her books include “A Worldwide Travel Guide to Sea Turtles” and “Pandas to Penguins: Ethical Encounters with Animals at Risk.” She has a zoology degree from Texas A&M University and a master’s in journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.

Kim Lane served as copy editor on this issue. She is an award-winning publisher, editor and writer in Austin, Texas. She was the editor of Edible Austin magazine for over a decade, and her work has been featured in publications such as Mothering magazine and Salon.com, and on the air at National Public Radio. She was published in Salon’s anthology, “Life as We Know It,” and more recently, she co-wrote and edited the cookbook, “Thai Fresh: Beloved Recipes from a South Austin Icon.”

Austin writer and photographer Pam Penick is always on the prowl for interesting gardens to share on her website, Digging (penick. net), where for 16 years she’s been publishing “all the gardening goodness she can dig up.” She’s the author of “Lawn Gone!” and “The WaterSaving Garden,” and her articles have appeared in numerous publications. Pam also organizes an annual speaker series about garden design called Garden Spark.

Jill Sell is a freelance journalist, essayist and poet, specializing in the environment and nature. She is the co-founder of Three Women in the Words, a non-profit arts collaboration; a contributing editor for Ohio Magazine and a weekly contributor to The Plain Dealer, Ohio’s largest daily newspaper. She was named Best Freelance Writer in Ohio by The Press Club of Cleveland five times.

2022 | Volume 39, No. 2

EDITOR & CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Catenya McHenry

DESIGNER

Joanna Wojtkowiak

PLANT INFORMATION EDITOR

Joseph Marcus

ASSISTANT EDITOR

Elizabeth Standley FOUNDERS

Lady Bird Johnson and Helen Hayes

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

Lee Clippard

DIRECTOR OF EDUCATION

Demekia Biscoe

DIRECTOR OF HORTICULTURE

Andrea DeLong-Amaya

DIRECTOR OF SCIENCE & CONSERVATION

Sean Griffin

DIRECTOR OF OPERATIONS

Dawn E. Hewitt

DIRECTOR OF MARKETING & COMMUNICATIONS

Catenya McHenry

DIRECTOR OF LAND RESOURCES

Matt O’Toole

DIRECTOR OF FINANCE

Cathy Tran

DIRECTOR OF DEVELOPMENT

Leslie D. Zachary

ADVISORY COUNCIL

CHAIR Laura Beckworth

VICE CHAIR Jeanie Carter

SECRETARY Celina Romero

Sarah Natsumi Moore is a commercial and editorial photographer based in Austin, Texas who travels worldwide. Shooting projects large and small, close and far, she enjoys infusing life in still life products in her studio as well as capturing beautiful spaces and environments for brands.

Drew Thompson is a cave biologist with the City of Austin’s Wildland Conservation division. His essay highlights the Wildflower Center’s recent cave discovery, the importance of preserving its biodiversity, and the importance of preserving the fragility of the land.

Wildflower (ISSN 1936-9646) is published biannually by The University of Texas at Austin Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, 4801 La Crosse Ave., Austin, TX 78739-1702. Copyright © 2022 by the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Members of the Wildflower Center receive a subscription as a benefit of membership. No part of this periodical may be reproduced without the written consent of the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. The opinions expressed herein may not necessarily reflect those held by the Wildflower Center. Please direct any inquiries or letters to 512.232.0100 or magazine@wildflower.org.

Materials are chosen for the printing and distribution of Wildflower magazine with respect for the environment. Wildflower is printed locally in Austin , Texas, by Capital Printing.

6 | WILDFLOWER

WILDFLOWER

WILDFLOWER.ORG facebook.com/wildflowercenter @wildflowercenter @WildflowerCtr youtube.com/ WildflowerCenterAustin FEATURED Contributors

PHOTOS (Melissa Gaskill) author-provided, (Pam Penick) self portrait, (Sarah Natsumi Moore) self portrait, (Drew Thompson) Eleonora Chouquetta

Our Founders’ Favorites

We understand why Lady Bird Johnson and Helen Hayes loved these.

by Andrea DeLong-Amaya

TEXAS BLUEBELLS

Eustoma exaltatum ssp russellianum

WHY WE LOVE THEM: Whoa, Nellie! These show-stopping, bell-shaped blossoms span 2 - 2.5 inches wide. The flowers typically show purple, but sometimes white or pink versions appear above the matte-gray, almost succulent foliage.

PREFERRED GARDEN ENVIRONMENT: Moist, sandy or loamy soils in fields and prairies under full sun

FUN FACT: Legend has it that Lady Bird Johnson proclaimed the Texas bluebell to be her favorite wildflower. (Legend also has it that she loved any plant thriving in the garden.)

BRINGS THE BLOOMS: Flowers emerge in June and continue through summers with ample rain.

PLANT Picks

PHOTO Wildflower Center

TEXAS MADRONE

Arbutus xalapensis

WHY WE LOVE THEM: Mrs. Johnson imparted that the regal madrone flanking the front door of her Austin residence enticed her to purchase the property. Not long after her passing, the tree also died. A skilled craftsman carved vases and bowls from the salvaged fine wood.

PREFERRED GARDEN ENVIRONMENT: Well-drained, dry, rocky limestone or igneous soils in full to partial sun

PRO TIP: Who doesn’t like a challenge? These trees is notoriously difficult to cultivate, preferring a specialized menu of soil nutrients to thrive. It is best to plant them in soils that already support madrones.

BRINGS THE BLOOMS: February to April

WHITE WAKE-ROBIN

Trillium grandiflorum

WHY WE LOVE THEM: On a wall of our administration building hangs a sweet little sheet of paper adorned with a trillium sketched by Helen Hayes — Wildflower Center co-founder, actress and close friend of Mrs. Johnson. Evidently, her imagination was seized by a woodland understory densely carpeted with her favorite flower, white wake-robin!

PREFERRED GARDEN ENVIRONMENT: Rich mixed woodlands, thickets and swamps in the eastern third of the U.S. Unfortunately, Texans miss out.

PRO TIP: True to form, this member of the lily family (Liliaceae) features three large petals on each flower.

BRINGS THE BLOOMS: May and June

8 | WILDFLOWER

PHOTOS (left) Mariann Watkins, (right) Wildflower Center

PINK EVENING PRIMROSE

Oenothera speciosa

WHY WE LOVE THEM: Several archived photos depict the charming Mrs. Johnson lounging in a bank of lush pink evening primroses. In addition to attracting our founding heroine, the flowers also lure insect pollinators. For cool-season greens, try fresh leaves in a salad, or cooked with eggs.

PREFERRED GARDEN ENVIRONMENT: Full to partial sun in well-draining dry or moist clay, loam, sand or caliche

PRO TIP: Neighbor it with plants like Texas lantana (Lantana urticoides) that are strong enough to hold their own against this colonizing beauty. This wildflower truly runs wild.

BRING THE BLOOMS: February through June

ESCARPMENT LIVE OAK

Quercus fusiformis

WHY WE LOVE THEM: Like no other tree, live oaks characterize Central Texas, their primary geographic range. Low boughs and twisting, sometimes gnarly branches add an inimitable personality to the landscape. And some easy-to-climb mature trees build strong friendships with agile youth.

PREFERRED GARDEN ENVIRONMENT: Sun or partial sun on dry, rocky, sandy, clay or loam soils with good drainage

FUN FACT: The Texas White House, former home of the Johnson family, nestles inside a colony of live oaks, including the historic Cabinet Oak where the President and First Lady entertained guests. There exists no statelier tree under which to host heads of state.

PLANT PERK: It’s often referred to as an “evergreen,” but technically it is not. Live oaks shed their leaves in March, only to immediately regrow new foliage.

Need more native plant info? Search our mobile-friendly Native Plants of North America database for bloom times, planting conditions and more: wildflower.org/plants-main

| 9

PHOTOS (top) Wildflower Center, (bottom) Lauren Gersn, LBJ Library

Fire Starters

Why we burn

by Jill Sell

During the summer of 2021, fire officials kept a close eye on 1 ½ acres of a prescribed burn in the research area summer burn plot.

THE 284-ACRE WILDFLOWER CENTER HAS CONDUCTED PRESCRIBED BURNS for the past 20 years. Most of the burns took place on about 70 acres reserved for long-term experimental research. In 2014, however, the instances and locations of prescribed burns were increased, based on positive land management results. Over the past two decades, about 600 acres have been burned (this number reflects repeated burning of some land tracts). On-site, the burns take close to five days to complete and are on a three- to five-year rotation.

Prescribed burning is the intentional burning of a landscape for a specific purpose. Matt O’Toole, the Wildflower Center’s director of Land Resources, instrumental in coordinating prescribed fires for land management purposes, lists some of the reasons for the burns as creating better opportunities for grass to grow for livestock feed, encouraging a greater diversity of plant material, improving water infiltration and increasing nutrients in the soil. Another very important reason is reducing the potential spread of devasting wildfires. Clearing out “fuel” such as dead wood and dried vegetation near residences and buildings can suppress a fire’s progression.

In a number of ways, safe prescribed burns add to the balance of survival in nature for both plants and animals.

“Smoke actually draws in some wildlife,” says O’Toole, “As we burn, we have hawks and other raptors circling the area looking for prey running out. And other birds harvest seeds and other plant materials that have been burned. They are in the area before we are even done burning. Rattlesnakes also move in from unburned areas looking for prey.”

Wildlife is very mobile, O’Toole notes. Also, prescribed burns done on the Wildflower Center’s property are limited to specific geographic “units” with definite boundaries. Wildlife can travel from a designated burn area to a non-burn area quickly where safety and natural habitat is readily available. Prescribed burning is also a slower process than a wildfire, providing more time for animals to seek safety.

10 | WILDFLOWER BOTANY 101

PHOTO Sean Griffin

“Prescribed burning is effective and also one of the most economically feasible tools for land management,” says O’Toole, emphasizing that in today’s world of climate change and uncertain economic conditions, management is more vital than ever.

“What the Wildflower Center has learned through long-term research about prescribed burnings provides insight for state and public organizations, as well as private landowners,” says Dr. Sean Griffin, the Wildflower Center’s first director of Science and Conservation. For example, the Center’s work has revealed that winter burns increase the abundance of non-native grasses and lower plant diversity overall. But prescribed burns at any time of year carry both pros and cons, according to O’Toole and Griffin.

“Our research has already led to some changes in management of land around Austin,” says Griffin. “It’s tricky though, because many landowners are more nervous about burning in the summer. So, it is a balance.”

The Center’s studies echo the historic summer burns used by Native Americans in the region. The less intense but regular burns were completed to help with sustaining wildlife, hunting and foraging, and gaining advantage in certain conflicts, according to O’Toole. The Wildflower Center looks at prescribed burning as a “more sustainable method of land management,” says Griffin.

O’Toole also notes that the Wildflower Center is “a unique site with lots of sensitive features,” making it impossible to “completely mimic what Native Americans did with their burns.”

Being closer to neighborhoods and urban areas than historic people also dictates that the Wildflower Center remains aware of public perception. It works closely with the University of Texas fire marshal, local jurisdictions and other conservation agencies to notify the public of scheduled burns, provide education and share resources. Any negative factors caused by burns — smoke, visibility impairment, smells and disbursement of emission ingredients — are addressed during months-long preparation before each burn. During that time, additional safeguards are put into place if necessary, including the protection of any old-growth trees that may be within a burn unit.

Land managers in years past did not have to contend with extended drought and climate

change. The Center’s ongoing research shows that invasive grasses do better in drier conditions and that periods of heavy drought also increase the risk of wildfires.

“As the drought increases, and every year it gets a little hotter, it is even more important that we stay on top of land management and burn regularly,” says Griffin. “Fires are natural historic disturbances and would have burned every one to six years across most of Texas. But they were mostly small scale and low intensity, not the huge wildfires you see today.”

While Wildflower Center staff appreciate trees and shrubs, they know rich grasslands and savannas will be diminished if unchecked woody encroachment is allowed. O’Toole says burning opens up the surface of the soil and allows “hidden” plants to emerge — some that may have been dormant in the seed bank for years. Burning on Wildflower Center property has encouraged greater amounts of native grasses, including silver bluestem ( Bothriochloa laguroides), little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium) and big bluestem ( Andropogon gerardii ), among others.

“The benefits to the landscape from prescribed burns are tremendous and needed,” insists O’Toole. “It’s how we keep wildflowers growing in our natural areas outside the gardens. If we didn’t do it, we may not have the presence and abundance of the [wildlife and plants] that bring our guests to the Wildflower Center.”

Read more about prescribed fire at wildflower.org/ project/ prescribed-fire

Watch videos about prescribed fire here:

| 11

Aerial view of a summer prescribed burn in the Savanna Meadow

PHOTO Wildflower Center

Bumblebees ( Bombus spp.), like the one pictured here on a sunflower ( Helianthus sp.), are decreasing in relative abundance as the summers get hotter.

12 | WILDFLOWER IN THEIR Element

PHOTO Dr. Gabriella Pardee

Buzzworthy

Bigger isn’t always better — especially if you’re a bee trying to survive climate change.

by Elizabeth Standley

DR. GABRIELLA PARDEE’S DECISION to study bees was partially one of selfpreservation. As an undergraduate at the University of Toledo, she conducted research on Azteca instabilis ants, a particularly aggressive species that is a friend to farmers hoping to eliminate coffee pests, but a foe to researchers wanting to avoid the need for anti-inflammation lotion.

“I loved doing research, but I hated working with ants,” Pardee explains. “If you got too close to the nest, they’d just come out and attack you.”

Countless bites later, she knew it was time for a change. At the suggestion of her mentor, Pardee turned her attention to bees.

“There was a little community garden on campus, so I went out that day with a net, caught some bees, and thought, ‘Bees are amazing!’” she remembers. “From there on out, I’ve spent every single summer standing in meadows with a net, looking for bees.”

That may sound quaint, but Pardee’s research is cutting-edge. From 2013 to 2018, she and her husband, Dr. Sean Griffin, director of Science and Conservation at the Wildflower Center, joined an ongoing research project at the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory in Gothic, Colorado that seeks to understand how various bee species respond to climate change. Their work consisted of collecting bees at an elevation of 10,000 feet and was physically challenging. Griffin says he got terrible altitude sickness on one of the excursions.

“I wasn’t used to [the elevation],” he explains. “I went in and hiked eight miles in one day on snowshoes and it laid me out.”

But temporary discomfort is a small price to pay for impactful science. By the time Pardee began writing her doctoral dissertation, which examines the effects of climate change on insect populations, the Colorado project had amassed nearly 20,000 bees of approximately 154 species. She and her team analyzed the collection closely and made an interesting, if disconcerting, discovery: As summers get hotter and drier, large-bodied bee populations decrease, and small-bodied bee populations increase in relative abundances. Pardee and Griffin, along with several other researchers, co-authored their

| 13

Dr. Gabriella Pardee and Dr. Sean Griffin on a bee collecting excursion at the Nachusa Grasslands in Franklin Grove, Illinois. PHOTO Sean Griffin

findings in a paper titled, “Life History Traits Predict Responses of Wild Bees to Climate Variation,” recently published in the journal, Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

“We focused on body size, because body size has been shown to affect bees differently in response to global change,” Pardee explains. “Then we looked at their nesting behaviors.”

cause if [the bumblebees] are visiting flowers farther away, then it could help with gene flow.”

Of course, the fact that smaller bees are increasing in relative abundance under warmer conditions may compensate for the decline in bumblebees and create what Pardee tentatively calls “pollination security.” But she says only time will tell, and it’s essential for people to take action to protect bees of all species. These winged insects are independently responsible for pollinating about 75% of the Earth’s crops, so losing them could devastate the ecosystem. In fact, Albert Einstein is believed to have said, “If the bee disappears from the surface of the Earth, man would have no more than four years left to live.” Griffin and Pardee are more optimistic.

“I bet humans could survive,” Griffin speculates, “But eating wouldn’t be as much fun, because it’s all the best things [that bees pollinate], like fruits and vegetables.”

Luckily, there are actions people can take now to protect bees and the flavorful meals they make possible. Pardee says that, in addition to climate change, one of the biggest threats to bees is habitat loss. That’s why she encourages gardeners to fill their beds with native plants that bloom in succession.

“Bees are just emerging from their nests [in early spring, when there aren’t many flowers available],” she explains. “They’re hungry, they’re trying to build their nests, so having plants that bloom from early spring up until the late fall is really, really important.”

Bumblebees, which tend to be larger-bodied, are comb-building cavity nesters, while solitary bees, which tend to be smaller-bodied, are soil-nesting.

“Bumblebees are one of our best pollinators, so [their decline in relative abundance] is concerning,” Griffin says. “They are the largest [bees] and they have the most hair. They can transport a lot of pollen.”

The genus can also transport that pollen much more widely than their soil-nesting counterparts.

“Smaller bees usually have a foraging radius of about 200 to 500 meters, whereas bumblebees can travel about six kilometers from their nest,” Pardee says. “That’s good for plants, be-

Pardee and Griffin also recommend checking out “citizen science” websites like iNaturalist (inaturalist.org) and Bumblebee Watch (bumblebeewatch.org), where user-submitted photos of bees are used by researchers to monitor population changes. The more data collected about wild bees, like those in Pardee’s study, the better.

“Wild bees are actually better pollinators than domesticated honeybees in many crops and natural systems, but we don’t know as much about their trajectory because there are just so many different species and they all have different responses to global change,” Griffin explains. “So, this is an exciting field because I feel like we can really make a difference. And bees are just super cool … they’re interesting animals.”

14 | WILDFLOWER

Shop pollinator plants at the Wildflower Center’s Fall Native Plant Sale. Visit wildflower.org

TOP One of Pardee and Griffin’s research subjects, a bumblebee (Bombus sp.) pollinates a bluebell (Mertensia sp.).

BOTTOM Small-bodied, solitary bees like this one are increasing in abundance as temperatures rise. PHOTOS Dr. Gabriella Pardee

| 15 All the native plant knowledge you can handle — right at your fingertips Native Plants of North America Support the database you love! Give Today BIT.LY/GIVE-NPONA

We acknowledge that we are standing on the ancestral homelands of the Plains Tribes, including the Lipan Apache, Comanche and Tonkawa. We acknowledge that systematic elimination and forced expulsion of the Indigenous peoples of Central Texas enabled the society of today to develop on these lands. The Wildflower Center now resides within this society, which was established on these taken lands, at the divestiture and suffering of Indigenous peoples and the land itself. We pay respect to the people of the Plains Tribes past, present and future.

LAND ACKNOWLEDGMENT OF THE LADY BIRD JOHNSON WILDFLOWER CENTER

Homeland

Original stewards of the land we tread

FEATHERY GRASSES BEND AND SWAY in a meadow of confetti-colored wildflowers. Live oaks (Quercus fusiformis) stretch muscular limbs in solitary splendor. Ephemeral streams trace the path of water across scoured rock. Flitting from Ashe juniper (Juniperus ashei ) to possumhaw (Ilex decidua), birds chirp and pluck berries, and bumblebees comb wands of lavender liatris ( Liatris punctata var. mucronata). The living richness of the land that the Wildflower Center is built on encompasses two ecoregions: The biologically diverse Edwards Plateau and the endangered Blackland Prairie. It is also the homeland of distinct groups of Indigenous peoples. Although they were forced off their land by Anglo-American colonization, it is still their homeland.

For at least 13,000 years, people have called Central Texas home. The oldest archaeological evidence of human presence found at the Wildflower Center is a dart point in a cave that dates between 200 B.C. and A.D. 150. But after the first Europeans arrived in the 1500s, local Native American tribes eventually suffered loss of life and their land. Acknowledging that history is important, says Outreach Program Coordinator Dorothy Martinez, who helped draft the Wildflower Center’s land acknowledgement. That statement of recognition of the history of Indigenous people on their traditional homeland is read aloud before the start of various Center meetings. “We’re not the first people to occupy this land that we stand on,” she says. “A land acknowledgment is a way for us to appreciate and understand the people who shaped that land.” Martinez, who grew up just a few miles from the Center and whose heritage is in the Comanche tribe adds, “those people are still here, and they still recognize this land as the place where their ancestors once lived. It’s a way of remembering them and inspiring others to take action to support Indigenous communities.”

From the 1500s to the early 1800s, as the native people were being forced from their land, various nations laid claim to the territory of Central Texas. But by 1835, the Wildflower Center land was privately owned, acquired

by Pam Penick

through a Mexican land grant. Not long after Texas became a U.S. state, Morgan Hamilton purchased the land. A purveyor of dry goods at a corner store on Congress Avenue and Sixth Street in Austin, and later a U.S. senator, Hamilton grazed cattle on the property, then known as Hamilton’s Pasture. The land changed hands multiple times over the next century until 1985, when developer Gary Bradley bought it for the master-planned Circle C community. The Wildflower Center puchased 42 acres of that land. Today, the land, now expanded to encompass a total of 284 acres, supports the Center’s gardens and natural areas, which draw visitors from around the world to appreciate the unique nature of Texas native plants.

Riddled with caves, the Wildflower Center land is in the environmentally sensitive recharge zone for the Edwards Aquifer, one of the most important water resources in Texas. Rainfall and runoff trickle through holey karst bedrock into the aquifer, which pumps millions of gallons of icy water daily into the natural springs that fill Austin’s beloved Barton Springs Pool.

Matt O’Toole, the Center’s director of Land Resources, recognizes the critical role the Center plays in protecting the aquifer and Barton Springs. “We’re right over the recharge zone for the Edwards Aquifer,” he says. “People pay attention to what happens here. We have to manage this site in honor of the water quality and quantity that eventually makes its way to Barton Springs.” The land also serves as a green space and place of natural tranquility for Central Texans living in a rapidly urbanizing region. “People come here to engage with nature and reduce stress,” O’Toole says. “so, we manage the land with a human health and well-being aspect, too.”

This fragile land — stolen from its native people, claimed by nations, deeded, gifted and now managed as a botanical garden with a mission to conserve native plants — is the Wildflower Center’s responsibility to steward for future generations. It does so with respectful acknowledgment of those who came before and whose homeland it remains.

| 17

A Place AND A Promise

FROM LEFT A view from the Savanna Meadow of the Auditorium, Great Hall, Library, and administrative offices wing.

FROM LEFT A view from the Savanna Meadow of the Auditorium, Great Hall, Library, and administrative offices wing.

18 | WILDFLOWER

PHOTO Timothy Hursley

BY PAM PENICK

For

the Wildflower Center has inspired the conservation of native plants.

WILDFLOWERS — THOSE colorful, rough-and-tumble bouquets dotted across meadows, fields and roadsides by people and Mother Nature — make excellent ambassadors. Their romantic beauty draws people into an appreciation for other native plants, perhaps even for the pricklier or less colorful ones. Lady Bird Johnson knew this well. When she co-founded the National Wildflower Research Center — later renamed the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center — she savvily branded the wildflower as the friendly face of her organization. “Wildflowers got you in the door,” explains her youngest daughter, Luci Baines Johnson. “Mother wanted this institution to awaken our nation’s conscience about the importance of native plants. And what better ambassador to do that than the wildflowers that are so flirtatious and seductive and beautiful and bright and hopeful?”

The wildflowers carpeting the Texas countryside each spring attract thousands of

visitors eager to see denim-blue fields of bluebonnets (Lupinus texensis), swaths of yellow and red flame acanthus ( Anisacanthus quadrifidus), disks of sunset-hued firewheel (Gaillardia pulchella) and more. Attractive ambassadors indeed! But the Center has never been solely about pretty flowers. “Mrs. Johnson said that the Wildflower Center is both a place and a promise,” says Executive Director Lee Clippard. “We are a place where people can connect with nature and native plants — where we are actively displaying and conserving native plants. The promise is being made to future generations, and that’s through our education and the science and research that we can pass along.”

This year, the Wildflower Center celebrates its 40th anniversary. Over the past four decades of pursuing the mission to inspire the conservation of native plants, the Center has grown from a private nonprofit research organization mailing out one-page flyers, to a public botanical garden visited by

20 | WILDFLOWER

Spring bluebonnets on display in the Savanna Meadow with a view of the Great Hall, Observation Tower and administrative offices in the distant. PHOTO Wildflower Center

almost a quarter million people in 2021. It’s become an educational hub for homeowners, citizen scientists and public landowners, and a publisher of a comprehensive online database of North American native plants. The Center has also become a seed bank of Texas plants, a developer of Habiturf ® (a native turf grass mix) — a part of the University of Texas — and a participant in important ecological research. These achievements are due to the hard work of many dedicated and passionately invested people — from the Center’s namesake founder, executive directors and board members, to the staff, volunteers, donors and members. The humble Wildflower Center has opened a lot of doors and minds — and continues to do so today.

Growing the Wildflower Center

In December of 1982, on Lady Bird Johnson’s 70th birthday, she donated 60 acres of land in East Austin and $125,000 to establish — with co-founder Helen Hayes — the National Wildflower Research Center. “ Most people think of 70 as a time for retirement,” says Luci Baines Johnson, “not as a time to begin a brand-new national project. But Mother wasn’t most people.” At the time, the native-plant movement was in its infancy and much about native plant botany remained unstudied. “There was a lot we didn’t know about seed propagation [or] plant propagation for our native plants,” says Clippard. “Did they need to freeze? Did they need to be planted at certain times of the year? Lots of basic information like that. There was a huge effort to not only gain that knowledge through research and practice but then share that with the rest of the world.”

The Center operated purely as a private research facility in the early years, with wildflower plots for horticultural research. But even though it lacked public gardens, visitors showed up anyway. “People really wanted to visit,” says Clippard. “School groups wanted to come through; tourists would arrive there.” Leadership quickly recognized that the Center should expand to become a public facility.

In 1995, the Center relocated to a 42-acre site in Southwest Austin, nine miles from downtown, in a scenic transition zone between the limestone escarpments of the

| 21

ABOVE A 10,000-gallon stone cistern doubles as an observation tower offering dramatic views of the Center, prior to the grand opening PHOTO Timothy Hursley

BELOW The golden sunrise shining light on the Observation Tower, gardens and the Great Hall. PHOTO Wildflower Center

OPPOSTE PAGE TOP

Theme

Edwards Plateau and the deep gumbo soils of the Blackland Prairie. The new location offered visitors a distinctly Central Texas landscape to explore — five acres of native-plant gardens and natural areas designed by J. Robert Anderson (FASLA and principal), Eleanor McKinney (EMLA) and Darrel Morrison (FASLA), along with a building complex designed by Overland Partners. Clippard says that the Center welcomed about 40,000 people through the garden gates that first year. This year (2022), it’s expecting more than 230,000.

ed and reused boulders found on-site,” says Anderson. “ There are some tall walls on the north side of the Great Hall that hold up the terrace. We found accomplished rock workers to tie the building to the land with those walls. It’s almost a transition from the geology of the land itself up to the building. One of the best compliments we got was, ‘You can’t tell where the landscape stops and where the architecture starts.’”

OPPOSTE PAGE BOT-

Not only do the gardens connect to the natural landscape, but to the award-winning architecture of the Center’s buildings, as well. The structures reflect three main influences in Texas vernacular architecture: Spanish colonial (which shows up in rusty sandstone arches in walls, aqueducts and the observation tower), German settler (as seen in solid limestone-block construction) and Texas rancher (evoked with corrugated steel siding and silos). Landscape architect J. Robert Anderson worked closely with the structural architects to blend buildings with the gardens and meadows using local stone and experienced local masons. “We brought in limestone and sandstone in walls that we built, and we harvest-

The buildings provided space to expand the Center’s educational offerings through new classrooms, a 240-seat auditorium and the Little House for children. Planted exclusively with Texas plants, the new gardens showed visitors that natives can be used the same way as traditional garden plants, but with less water and without the chemicals often needed to keep fussy exotics thriving in the hot and humid, drought-to-flood Central Texas climate. “The Wildflower Center made people appreciate native plants for their beauty, and not just because it’s the thing to do or a landscape ordinance requires more native plants,” says Anderson, “And that appreciation of beauty — the inherent nature of why we love bluebonnets — in many types of native plants loosens up our landscape palette to make nontypical front yards look interesting and cool. It’s a

22 | WILDFLOWER

Children observing aquatic wildlife and native Texas plants in the Wetland Pond at the Center’s entrance. PHOTO Thomas McConnell

Gardens in 1995 displaying 23 separated theme beds used for demonstration and research. PHOTO Timothy Hursley

TOM Currently the most extensive exhibit of native plants and grasses. PHOTO Wildflower Center

| 23

24 | WILDFLOWER

TOP An aerial view of the 4.5-acre Luci and Ian Family Garden which opened in 2014.

BOTTOM Relaxing wooden swings in the Mollie Steves Zachry Texas Arboretum PHOTOS Wildflower Center

huge achievement that the Wildflower Center inspired people to do.”

By 2002, the Center’s original 42 acres had expanded to 284 acres, securing a buffer zone of natural landscape around its core gardens and opening space for the Mollie Steves Zachry Texas Arboretum and the Luci and Ian Family Garden. The additional acreage also allowed room for prescribed burn research and its impact on native plant diversity. “ When we added the rest of the land,” says Clippard, “it was transformative, and it protected it for future generations. We’re stewarding this important and sensitive piece of land, and it made our southern border contiguous with other green spaces — water-protection land and parkland — that will never be developed.”

Forty Years of Native Plant Advocacy and Research

The Wildflower Center exists not only as a physical place but also as an online resource. Since those early years of stuffing one-page flyers into envelopes, the Center has developed the Native Plants of North America online database that contains information about every native plant in North America north of Mexico — about 25,200 plants. “We don’t have Mexico in there yet,” says Clippard, “but that is a goal for us.” About 2.4 million people currently use the database every year. “Everyone uses it,” Clippard says. “It’s used by citizens, gardeners, by landscape architects, and for research and science. It’s one of our most popular tools, and it really goes back to our core mission, which is sharing information about native plants.”

The Wildflower Center also led the development of the Sustainable SITES Initiative (SITES ®) — a green program and rating system used by landscape architects, engineers, developers, ecologists and others in land development and management. “That project has had international impact through all of the projects that are now being SITES-certified,” says Clippard. Our team has worked with architects, landscape architects, engineers, resource managers, conservation professionals and multidisciplinary design teams on projects at multiple scales. We have worked on high-impact projects for public and private clients, including national and regional parks, corporate headquarters, urban developments, institutional campuses, river and prairie

| 25

TOP A SkySystem™ greenroof at the Edgeland House in Austin designed by Wildflower Center environmental designers. PHOTO Paul Bardagjy

BOTTOM Center experts led design on the LEED platinum certified George W. Bush Presidential Center in Dallas. PHOTO John W. Clark

restoration, state highways and botanic gardens, that includes things like the George W. Bush Presidential Center in Dallas and the Waterloo Greenway project in Austin, all to help developments use native plants appropriately. Those projects cumulatively impacted almost 90,000 acres in Texas. And hopefully through that, we’ve been able to demonstrate how beautiful native plants can be and how we can support native environments.”

Research has been a constant throughout the Wildflower Center’s 40 years. The Center’s longest-running research project — spanning the past 22 years — has been an examinination of the impact of prescribed fire and grazing on oak-savanna landscapes. “We’re finally seeing some trends in the data,” says Clippard. “And we’re starting to overlay new research on top of that — looking at pollinators and bird diversity and soil. We’ve hired a restoration ecologist to lead our Science and Conservation program. I think that’s going to bring a unique perspective to our research by linking plants to their wildlife and pollinators.”

The Center’s research arm was also instrumental in making green roofs feasible in hot climates. Green roofs are important tools for making cities resilient to climate change by capturing rainfall and reducing runoff, lowering a building’s heat load and need for air conditioning and removing carbon and other pollutants from the air. They also provide essential habitat for birds and pollinators in our increasingly urban world. But even as green roofs were taking off elsewhere, they faltered

in hot climates, where traditional rooftop plants struggle to survive in harsh conditions. In response, Wildflower Center researchers developed a growing medium designed for green roofs in semi-arid climates, allowing them to succeed in Texas and beyond.

In 2006, the Wildflower Center joined The University of Texas at Austin. Luci Baines Johnson says that union was a comfort to her mother. “When Mother started the Wildflower Center,” recalls Johnson, “she realized there was a whole lot more life in the rearview mirror than that which lay ahead. Like every mother, she wanted to make sure her child would thrive independently on its own when she was no longer here. Mother believed that The University of Texas was going to be here till Gabriel blew his horn, and she felt like, if her Wildflower Center could be a part of the University of Texas family, it could help young students want to pursue their life’s work in the environment.” Clippard also sees the value of being part of the university. “It provides an amazing opportunity for us to be part of world-class research happening across campus,” he says. “There are faculty and graduate students studying biodiversity and climate change, and that’s our wheelhouse. We’re able to provide a resource for all of that research and education. It gives us an opportunity to expand our impact.”

Focusing on the Future

When the Wildflower Center was established, Austin’s population was 358,950. Today it’s over 1 million and growing rapidly. With so many people pouring into the Austin area, and with housing and commercial development gobbling up open land, the Wildflower Center has become an urban refuge sooner than perhaps anyone could have imagined 40 years ago.

Lady Bird Johnson, who was only five when she lost her mother, found consolation outdoors in sunny meadows and in the cool shadows of trees. As an adult, she never forgot the healing power of nature. “Mother felt that nature could do so much for humankind’s ills,” says Luci Baines Johnson. “It could lift your spirit. It could make where you live a healthier, happier place.” That sense of refuge and healing is more important than ever to the Center’s mission. “As Austin grows and we become this giant metropolitan area,” says

26 | WILDFLOWER

Science and Conservation research team identifying plants during a veggie survey in 2021.

PHOTO Sean Griffin

Clippard, “the role the Center can play in human health is becoming more and more central to our purpose.” Landscape architect Anderson agrees. “ There’s a health issue that’s provided by a garden,” he says. “It offers a sense of relaxation, getting away from the world, not being next to paving. I think health is an underappreciated part of open space and gardens. And man, do we need something to de-stress our lives right now, after two years of COVID.”

As Austin and the Wildflower Center have grown, more and more people have been able to visit and learn about native plants. Clippard hopes even out-of-state visitors “gain an appreciation for the native plants in their own state, and start thinking about how they can support pollinators and wildlife.” Of course, more people visiting means more cars in the parking lot and more foot traffic in the buildings and gardens. “One of our biggest challenges ahead is figuring out how to accommodate the growth in our community and serving the growing community best,” says Clippard. “The potential for us to impact people is great, but we need to do that in a way that’s protective of the environment and equitable for everyone.” Plans are currently underway to redesign the garden’s main entrance to allow easier public access to the gift shop, café and restrooms. “We want to pull those facilities out to the front,” says Clippard, “and make them more accessible as a resource for the surrounding community.”

A Gift of Hope

Despite the enormous challenges of our time — climate change, habitat loss and species extinction, to name a few — the Wildflower Center is positioned to be a responding leader. After all, as Lady Bird Johnson recognized 40 years ago, native plants give us much that we take for granted: Species diversity and a distinct sense of place that feels like home; habitat for wild creatures that evolved alongside those plants; healthier landscapes that don’t require chemical interventions to thrive; and gardens better able to cope with extreme weather events. With the amount of global change happening, native plants need our help as much as we need theirs. “People can take action to save and foster native plants,” says Clippard. “There’s so much we can do to improve our environment, and the Wildflower Center will continue to play a pivotal role in inspiring people to do so.”

Reflecting on today’s challenges, Luci Baines Johnson recalls her mother’s oft-quoted words: “Where flowers bloom, so does hope.” “There’s lots of discord in the world today,” says Johnson. “But the Wildflower Center is not a place where that blooms. Hope for tomorrow, that was Lady Bird Johnson’s work. The environment is where we all meet, as Mother said. It’s something we can protect and celebrate. Where flowers bloom, so does hope… and what greater gift is there than hope?”

| 27

Mrs. Johnson standing in a field of wildflowers near Stonewall, Texas in April 1985. PHOTO Dennis Fagan

GROUNDED

The Center’s Inspirational Influence and Rooted Connection to its People, Plants and Place

by MELISSA GASKILL

by MELISSA GASKILL

28 | WILDFLOWER

FROM DREAM TO REALITY

Carolyn Curtis has been around since Lady Bird Johnson first had the idea for a wildflower center. Curtis, a longtime friend of the Johnson family, recalls spending a day at the LBJ Ranch — along with Nash Castro, who had worked at the White House on the national beautification program — when Mrs. Johnson described her dream. “Nash encouraged her … I did too. I knew that where she went, other people would go,” Curtis says. “She brought in Helen Hayes, saying, ‘we need a sparkly [person], someone everybody knows and recognizes,’ as if she was not one.”

Curtis served on the new organization’s Board of Trustees Executive Committee and Castro became its first president.

As the organization grew, there was concern about whether or not it could survive without Mrs. Johnson. “She was vastly relieved when we became part of The University of Texas,” Curtis explains. The Wildflower Center’s partnership with UT and the College of Natural Sciences has helped raise its profile.

“I don’t know anybody who started out with the Wildflower Center who ever had any regrets,” she adds. “We all were so proud of being a part of it, even at the rockiest times. I want my tombstone and my obit to say I was a founding member of the Wildflower Center.”

The Center’s beginnings, says David Northington, the organization’s first executive director, were inauspicious. “The original site had a little house on what was basically a piece of property used to grow hay. We put in a couple of greenhouses and plots to test germinating seed.” The staff at the time consisted of Northington, an administrative assistant, a botanist and Curtis as development director.

Northington traveled to as many botanic gardens around the country as the budget would allow. “None of them were doing anything with native plants,” he recalls. “It dawned on me that we could be the first true botanic garden that

| 29

ABOVE Carolyn Curtis PHOTO Alicia Wells

BELOW Former Executive Director David Northington lending a hand PHOTO Wildflower Center archives

OPPOSITE PAGE (clockwise from top left) Mrs. Johnson (sitting) relaxes against a tree, and original board members and staff enjoy refreshments while reviewing construction plans at the La Crosse campus. Volunteers of all ages lay grass and plant flower beds in the Theme Gardens. A volunteer pulls weeds and prepares a flower bed for planting. Center construction workers take a break. PHOTOS Wildflower Center archives

The Wildflower Center may be all about native plants and wildflowers, but it’s people who keep the mission alive. Here are a few stories of how the Center has inspired many to come aboard — as staff, volunteers and leaders — and stay throughout the last 40 years.

focused on using native plants to positively impact the planned landscape.”

About six years in, Northington had a conversation with a member of Mrs. Johnson’s staff about how to attract more attention to the center. “Mrs. Johnson understood it only existed because of her name on it and that she could not be the institution. I suggested we find a visible place and try to get people to come and see what we’re doing.”

Mrs. Johnson wanted the new site to open in the spring of 1995, before it got too hot for people to come and see it. “I asked her what date she wanted to open and said that we’d get it done,” Northington says. “She didn’t think we could, so I bet her $10. After the grand opening, she was there with some people giving a tour, and I went up to her and asked for my $10. She dug into her purse and gave me a $5 bill and five ones.”

MINDING THE STORE

Joe Hammer joined the staff in 1989, applying his retail and marketing background to create a small gift store. He stayed until 2017, eventually serving as director of visitor services, running the store, admissions, the café, facility rentals and adult tours. “The longer you are at a place, the more hats you wear,” he points out.

“The Center had to raise its budget basically from scratch every year and we rely heavily on donations, memberships, grants and facility rentals,” says Hammer. The store, catalog and (later) website became important sources of support. “We carried things that were educational, that reflected our mission.”

Hammer recalls when the Center was moving from East Austin to its current location in South Austin and the architectural

firm Overland Partners in San Antonio was hired. They asked Mrs. Johnson what she wanted the new site to look like. “She said, ‘I want it to look like God put it there.’ They really got it — the heritage of Texas, German hill country, Spanish and ranch architecture. The idea of capturing rainwater, which has been copied and improved on by lots of places around the country.”

Hammer adds that only one tree was affected by the buildings. “We preserved all the other trees that were there,” he says. “We put signs on them for the contractors, this tree has been valued at so many thousand dollars. We wanted to have a soft footprint on the land.”

“The Center was and is a wonderful cause,” Hammer says. “It is bigger than Austin and

30 | WILDFLOWER

TOP Joe Hammer PHOTO Alicia Wells

BOTTOM The Observation Tower, Great Hall, and administration building under construction. PHOTO Wildflower Center archives

“I want it to look like God put it there.”

much more than wildflowers. The place is just always exploding with new ideas and projects and never a dull moment.”

PLANTING SEEDS

Starting out as a volunteer at the original East Austin site in 1993, Julie Marcus is currently a senior horticulturist at the Center. “The energy of everyone here … it was fun and exciting. That’s probably what has kept me here — the people. The staff, the volunteers … everyone is just great.”

In the early days, the availability of native plants was a challenge. “When we first opened, we had two greenhouses but not enough staff members to do any real growing,” she says. “At first, we were just growing Texas bluebells, Mrs. Johnson’s favorite. They were hard to grow, but we were able to figure out what made them tick. Some things didn’t work in the gar dens, so we tried new things. Designs have changed. We’ve put in new gardens and added new areas. Over the years, we have learned how to grow a lot of things.”

She recalls the month before opening the new site as a flurry of planting. “We took possession of the site March 1st and opened March 31st. Fortunately, everybody wanted to be a part of it, so we had tons of volunteers out planting all these little plugs in the gar dens. When we opened the gates, it was wallto-wall people. Everyone wanted to see it.”

Native plants have become much easier to find, as their popularity and the emphasis on sustainable landscapes have grown — chang es due at least in part to the Center. “I think as far as putting native plants out in the com munity through our growing opportunities and plant sales, we have definitely contrib uted to that,” Marcus says. “And we have been able to add diversity to our gardens, which is really fun. We have some plants in our collection that are not readily available commercially. People are starting to get the importance of native plants, their role in con servation and native landscapes, especially with issues of climate change and how it has influenced landscapes.”

While people can find a lot of native plants at nurseries in the Austin area, she notes that isn’t the case in some other cities. “It doesn’t feel as mainstream everywhere as it does here. You just don’t have the availability, and people are not as familiar with natives. Our work is not done.”

| 31

TOP Julie Marcus PHOTO Alicia Wells

BOTTOM Staff and volunteers using tools to dig and preparing plots for planting in the front entrance. PHOTO Wildflower Center archives

VIVA VOLUNTEERS

“At the old site, there was a big wooden sign and a long driveway, and people sometimes just drove in and wanted to see things,” says Volunteer Coordinator Frances Cushing, who started as a volunteer in 1992.

And there have always been people wanting to volunteer. “While I sign up three people, three more apply,” she says. “It never has stopped. We couldn’t function without them.” She adds that the Center is always figuring out ways to better train volunteers, and does a good job taking care of them. One change she

has seen is more groups volunteering, including service groups at the University of Texas. The Center closed in 2020 due to the pandemic and most people began working at home, but staff rose to this challenge as they had to others. “Within a week or so, the education volunteer program decided we could do virtual tours and continue to engage people with online classes,” Cushing says. “I’m just amazed at how people responded. The attitude was, we can do this Once we opened back up, using timed visits, we had more visitors and people in online classes, memberships went up. Surprisingly, it was an exciting time for our department with all the things we’re doing. This place served as a refuge, a place for people to come out and heal.”

INSPIRING A NEW GENERATION

Wildflower Center Administrative Assistant Maggie Delamater, 28, first visited the Wildflower Center on an elementary school field trip. The experience made quite an impression, and as a young adult interested in geography and environmental restoration and conservation, she decided the Center would be a cool place to work. She started in spring of 2022 and, so far, it meets or exceeds her expectations.

“Everyone is friendly, curious, intelligent and passionate about what they do. It’s a really satisfying, stimulating work environment. Just the fact the Wildflower Center is so much about nature — it’s pretty much as close to working with nature as you can get without going out and doing the research yourself. I

32 | WILDFLOWER

“The attitude was, we can do this.”

TOP Frances Cushing

BOTTOM Maggie Delamater PHOTOS Alicia Wells

learn things every day working here — about botany, insects, fauna and weather.”

That learning happens both organically and formally, whether perusing the website to learn more about a plant, in conversations with coworkers or taking part in a plant survey.

The workplace culture encourages taking time out of the work day to step outside and appreciate what is here, she adds. “I can walk around the gardens, just look out into the savanna and see grasses blowing in the wind.”

She knows many co-workers who have been here for decades. “I think that speaks to their dedication and passion, to the fact it is a great work environment. People respect one another. Everybody is working toward the Center’s mission. Everybody is willing to put aside their differences or annoyances and stick around. It is worth it. It’s a really meaningful job.”

She hopes to work her way into a position related to conservation or restoration, but recognizes she has a lot to learn first. “I’m not in a rush. I’m here to work and learn and I’m open to whatever organically happens.”

RESEARCH

The Center’s realignment with the College of Natural Sciences and designation as a field research station in 2021 positions it to grow its research in the years to come. “I’m incredibly excited about the university embracing the Center as one of its premier field stations,” says Carolyn Long, a former board member, donor and volunteer.

For Long, one of the Center’s most significant accomplishments was developing — along with the United States Botanic Garden and the American Society of Landscape Architects — the SITES® (Sustainable Sites Initiative) program in 2006. SITES promotes creating sustainable landscapes that reduce demand on natural resources and sustain healthy ecological systems.

“For many years, people were familiar with LEED [Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design] green buildings,” says Long. “SITES is everything that goes on outside the box and tends to be every bit as impactful as what goes on inside it.” The program awards stars depending on how a planned landscape is developed or a degraded one restored. SITES was officially acquired by the Green Business Certification Inc. (GBCI) in 2015. The Center’s Luci and Ian Family Garden earned a 2-star SITES rating.

Long also sings the praises of the Center’s volunteers and staff. She says volunteers adopt specific gardens, designing and maintaining them over time. “They are a tremendous asset. They equate to something like 14 to 16 fulltime equivalent staff members.”

“There are staff members who have been here years, if not decades, and I count a lot of friends among them,” says Long. “It says a lot about their love of the place … the blood, sweat and tears that they’ve devoted … staying through changes and a pandemic. The other remarkable thing about staff is the number of folks who have left here and gone on to lead other

organizations. It’s like the UT motto, ‘What starts here changes the world.’ They take what they’ve learned here out into the world.”

Long is excited about the future, seeing ever more spectacular gardens, a better entry experience, more parking and more opportunities for education, as well as increased research. “And we will keep sending these great people out to other places; people who leave because they were presented with an amazing opportunity, which is not a bad thing. And a lot of them haven’t left, they’ve stayed because they loved it.”

| 33

Carolyn Long gives a tour of the Center PHOTO Joanna Wojtkowiak

“They take what they’ve learned here out into the world.”

CENTERED: News and Updates

The latest on our gardens and our work by Wildflower Center

Staff

Staff

34 | WILDFLOWER

Amy Galloway, certified arborist and lead horticulturist, tries out safety gear while practicing tree-climbing techniques at the Women’s Tree Climbing Workshop.

DON’T LOOK DOWN

WHILE WALKING A TRAIL ON ANY GIVEN Wednesday at the Wildflower Center, you may happen upon a set of ropes, carabiners, saws and a host of other treetrimming gear underneath an age-old post oak (Quercus stellata). If you look up about 40 feet in the air, you may see one of the Center’s skilled women arborists swaying from branch to branch, pruning trees or cutting down dying limbs.

“As soon as I learned you could climb trees for a living, I was trying to figure out how to do that,” says Rachel Brewster, Wildflower Center arborist.

Currently, she’s among a small but growing number of women tree climbers across the United States. According to the Women’s Tree Climbing Workshop (WTCW), a national organization seeking to increase gender equity in the arboreal world, only 6% to 10% of arborists in the U.S. are women, but Brewster is working to encourage more women to get excited about the industry.

“People think you need a lot of upper body strength, but it’s more about technique and having the right gear,” she says. Brewster volunteered at the WTCW’s three-day training event this past April in Wimberley, Texas. Twenty-two other women attended, including Amy Galloway and Leslie Uppinghouse, two of the Center’s horticulturists, both of whom recently completed their International Society of Arboriculture certifications. Participants scaled escarpment live oaks (Quercus fusiformis), talked ergonomics and tested out new gear. They also traded stories and shared tips about how to thrive in a male-dominated profession.

“It was an amazing bonding experience,” Uppinghouse says. “Women were not only realizing and learning there are better ways to stay safe but we also created a stronger community of women who can reach out to one another at any time for advice — and because of that, I feel more confident in the field.” Amid bald cypress trees (Taxodium distichum) bordering the Blanco River, strangers became friends.

“The workshop exceeded my expectations tenfold,” Galloway says. “I learned so much more than I could have imagined, and I built meaningful relationships with the instructors and other women in the tree-climbing industry.”

Prior to attending the WTCW campout, Uppinghouse was using ladders to reach high branches, which can be cumbersome and dangerous. Having skilled and experienced climbers on staff at the Center means dead limbs can be removed right away, creating a safer environment for visitors (by decreasing the risk of falling branches) and trees (by increasing their life expectancy through care and early intervention). Learning new tree-climbing skills has given Uppinghouse both confidence and a renewed sense of childhood wonder.

“I hadn’t climbed a tree in my adult life,” Uppinghouse explains. “I was afraid I wouldn’t be good at it and feel demoralized, but there was someone with me minuteby-minute, making sure I was comfortable and having a good time. I got back into that same headspace I was in as a kid climbing cherry trees in Lake Oswego, Oregon. It was the greatest thing ever!” – E.S. & C.M.

| 35

PHOTOS

Courtesy of Leslie Uppinghouse

LIGHT + LANDSCAPES

BRITISH ARTIST BRUCE MUNRO HAS ALWAYS been fascinated by and drawn to light.

“Light had always gotten me, from being a kid seeing Christmas-tree lights to just natural light in landscapes.”

Munro’s a passionate person who — for more than twenty years — has used art to help him express his imagination. Field of Light has connected him to something deeper, allowing him to explore and share what’s truly on his heart.

“I’m quite emotionally led and therefore when I feel things, light just seemed a really good medium to describe the world in various forms.”

In a way, you could say it all started with one flicker of light that would eventually evolve into 15,000 flickers. While living in Sydney, Australia, Munro would walk past a downtown lighting shop and couldn’t ignore the glowing lights in the store window. The florescent tubes lit his curiosity and led him into the lighting business. After working in the industry, he later started his own firm lighting homes. It was then that he discovered how important light is to influencing mood in a space.

“It wasn’t until the mid-’90s that people started to notice that you could create a feeling with lighting,” he says.

36 | WILDFLOWER

FIELD OF LIGHT

September - December 2022

To purchase tickets, visit wildflower.org/field-of-light or scan QR code.

Some years later, he felt new inspiration on an Australian trip to Uluru with his wife. Absorbing nature’s landscape was life changing for him, and it foreshadowed an idea of combining light with the landscape.

“It made me realize that there is power in landscapes, which I think we’ve lost that sense ... modern-day man has lost that sense. It’s a deep sense that we all know is there but because it’s such a natural feeling, you sometimes don’t even know you’re feeling it or why you’re feeling joyful, and all these things started to make sense to me,” he says.

After returning home, Munro told his wife, “I’ve just got to get this out of my head.”

As an experiment, he installed 15,000 lights in a field in front of their home which was on display for a year.

“In the evenings, I’d go out and turn the lights on and then people started to hear about it,” he says.

Scores of people visited but there was one spectator that made an impact on Munro’s soul.

“There was a lady that came several times and she later asked if she could bring her friend up to the lights,” he explains. “I went to turn the lights on, and she burst into tears, and she grabbed my hand. I thought I upset her, and she said, ‘Thank you,’ and I nearly burst into tears. It was very emotional. She passed away not long after. It obviously resonated with her. I said to my wife, ‘If there’s anything to motivate you to continue on what you’re doing, that is the key.’ I couldn’t have thought of anything better.”

That experiment has evolved into a world-renowned exhibition with 28,000 solar-powered light spheres known as Field of Light. Munro hopes it will be infectious, reconnecting people to nature and something meaningful within themselves.

“I’ve often thought: what is it about light? It’s the thing we can’t touch but it touches us. We can’t grab it, but when it’s switched on, it floods in,” he says. “If you walk away with a happy heart and a smile on your face, then it’s been a good experience.” – C.M.

| 37

LEFT Field of Light at Sensorio - Copyright © 2019 Bruce Munro PHOTO Serena Munro. RIGHT Precedent Images - Copyright © Bruce Munro PHOTO Mark Pickthall

ABOVE Professor of Integrative Biology Tom Juenger conducts research on switchgrass at biological field stations in Texas and other parts of the country.

OPPOSITE PAGE

Switchgrass field experiments by the Juenger lab and partners at Michigan State University

LIVING LABORATORIES

ON A RECENT SPRING SATURDAY AT THE LADY BIRD JOHNSON WILDFLOWER

Center, families strolled along paths surrounded by a riotous mix of bluebonnets, winecups and evening primrose. Avid gardeners stood in line for a chance to shop the Center’s annual native plant sale. And a teen in a glittering dress posed for quinceañera pictures beside a pond.

Meanwhile, behind the scenes, scientific research was going on that could have major impacts on how we combat climate change, the crops we grow and the fuel we put in our cars.

While the Wildflower Center is a tourist attraction and a valuable public outreach and education tool, it’s also a part of the Texas Field Station Network . This network at The University of Texas at Austin also includes the StenglLost Pines Biological Station near Bastrop and Brackenridge Field Laboratory in downtown Austin. The White Family Outdoor Learning Center, overseen by the Jackson School of Geosciences, is near Dripping Springs.

These living laboratories provide the opportunity for critical research and hands-on learning for students, as well as facilities for outreach to the public.

Tom Juenger, professor of integrative biology at UT Austin, has been studying switchgrass (Panicum virgatum) for a decade and conducts research at the Brackenridge Field Lab.

Switchgrass is a hardy perennial clumping grass that is native to much of North America. Its thin, fibrous blades can reach six feet in height, but its roots can sometimes grow three times as deep. While it may not be as pretty as the flowers at the Wildflower Center, it holds great potential as a biofuel source. It can be used for erosion control, particularly on the windswept plains of the Midwest, where this plant once played a critical role in the ecosystem, and as a cover for wildlife. It’s particularly good at pulling carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and sequestering it in its root system. It reseeds itself and can survive in a

PHOTOS (this page) Courtesy of The University of Texas at Austin, (oppostie page) Robert Goodwin, Michigan State University

PHOTOS (this page) Courtesy of The University of Texas at Austin, (oppostie page) Robert Goodwin, Michigan State University

38 | WILDFLOWER

wide range of temperatures and soils. In places where almost nothing else will grow, there is likely a variety of switchgrass that will be happy there.

Scientists are also interested in its complex genetic code, which holds clues about how this plant adapted to climate changes in North America over hundreds of thousands of years — and how we might be able to coax our food crops into doing the same.

“Switchgrass is neat because it lets us ask all of those questions,” Juenger says. “And the reason it lets us ask all those questions is it’s native to North America. So, it’s just a wild species and it has had to deal with climate change in the past, and it’s going to have to cope with climate change in the future. Aside from being a biofuel source, it’s also a great model organism for research.”

In a recent paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences , Juenger and his team studied varieties of switchgrass that contain either four or eight complete copies of their genetic code. For reference, humans have two copies of our genetic code.

Researchers found that the varieties with four copies, called tetraploids, were more specialized to their locales. While on their home turf, they are high performers in terms of growth, but the further they get from where they evolved, the more quickly they decline. Meanwhile, the varieties with eight copies of their genome, called octoploids, were generalists. They can grow in more places and much farther from their home turf, but the tradeoff is they don’t grow as large.

Mapping these genetic traits and tradeoffs can allow scientists to figure out which varieties might grow best in which places and how to breed hybrids that could grow in specific harsh environments or just about anywhere.

Mapping and modeling these scenarios is extremely valuable for researchers. But it’s no substitute for the real world.

Having field stations for research allows Juenger and his team to see how different varieties of switchgrass perform in real-world conditions. They use a network of 16 common gardens and field stations belonging to UT Austin, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, other universities and private entities that run from Central Mexico to South Dakota.

“Without sites like Brackenridge Field Lab and the Wildflower Center, we couldn’t do any of our research,” Juenger says.

Every plant is a data point that adds greater understanding to the complex inner workings of an organism that could have an impact on climate change.

“The more data we have, the better data we have, the better the models become at predicting how different plants will perform under different climate scenarios,” says Joseph Napier, a postdoctoral fellow working on predictive models in the Juenger Lab. “Common gardens and field stations are one of the best tools we have to gather that information.” – Esther R. Robards-Forbes, College of Natural Sciences staff

GIFTS OF NOTE

The Wildflower Center would like to acknowledge these generous donors and their gifts: Winn Family Foundation

$750,000 in support of accelerating research, conservation and outreach, and the Field Station Network.

Judy Weidow

$500,000 planned gift

Page and John Schreck

$250,000 Endowment in support of the Student Experience Program in the Education Department.

Colin Corgan

$75,000 to be dispersed over 3 years as Lady Bird Society membership

Claudia L. Parker

$41,500 planned gift

| 39

CENTERED: Thank You to Our Corporate Partners

ART SEEN ALLIANCE

Austin Wood Recycling | Blü Fern

Capital Printing | Cicada Lighting

Energy Renewal Partners

FastFrame & The Westlake Gallery

Meridian Hive | Native American Seed

Port Enterprises

40 | WILDFLOWER

CENTERED: Things We Love

Curated collectables we’re into by Catenya McHenry

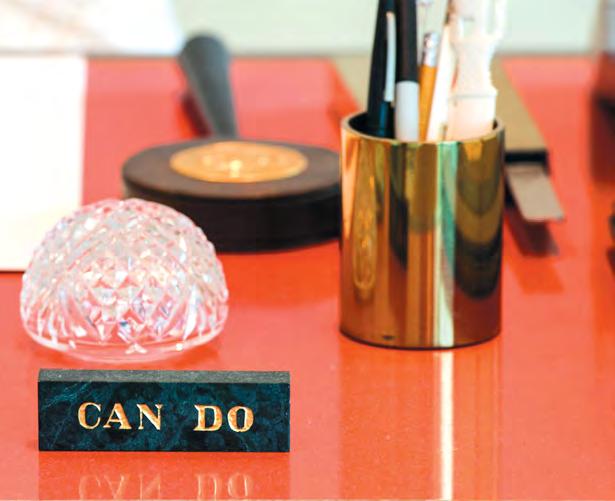

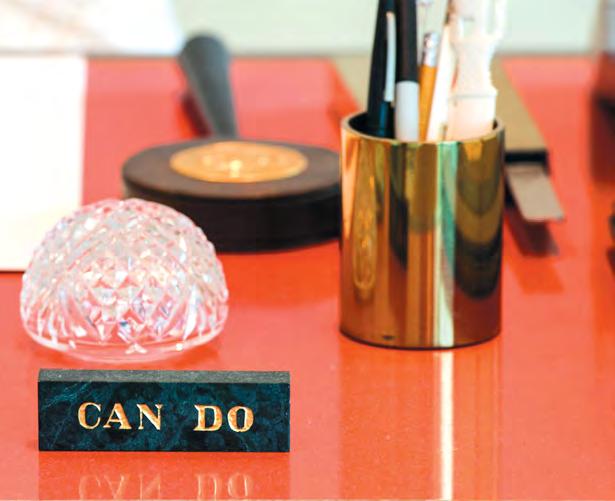

RECOGNITION Can Do Award

Instituted in 2018 by the Wildflower Center’s then-Executive Director Patrick Newman, the twice yearly Can Do award is an employee appreciation recognition honoring staff members who exemplify extraordinary achievements. The faux marble award is a replica of the paperweight Mrs. Johnson had on her White House office desk (the original is on display at the LBJ Library and Museum), and the Chinese characters on the reverse side refer to the ancient idiom: “When someone acquires the discipline of learning, then doing the work comes easily.”

It’s been said that one of President Johnson’s keys to success was that he surrounded himself with people who were resourceful go-getters. The ultimate compliment was for the president to call you a “can-do” person.

lbjstore.com/replica-can-do-paperweight

ART Sketch of Trillium

Helen Hayes was not only one of the most distinguished actresses in America for several decades, but also an avid gardener and a close friend of Lady Bird Johnson. At the recommendation of Nash Castro — another friend of Mrs. Johnson’s and the former regional director of the National Capital Parks in Washington, D.C. — Helen was elected to the National Wildflower Research Center’s board, serving as vice chairman.

One day, Nash, his wife Bette and Helen began chatting about their favorite wildflowers. Nash opted for the Mariposa lily (Calochortus nuttallii ), and Bette loved Sierra Queen Anne’s Lace (Perideridia parishii ). When it was Helen’s turn, she couldn’t recall the name of her favorite, so Nash encouraged her to draw a sketch. On a 5-by-7 index card, Helen penciled a flower that Nash immediately recognized as a trillium (Trillium albidum ssp. parviflorum).

The card lived in a stack of Nash’s papers until the spring of 1998 when the small group attended a board meeting at the new Wildflower Center. It was then that the Castros decided the drawing should move to a new home in the Helen Hayes Suite at the Wildflower Center.

STAMPS Plant for a More Beautiful America

In honor of Mrs. Johnson’s contributions — championing the Highway Beautification Act of 1965, and founding the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center — the U.S. Postal Service issued six stamps in 1966 and 1969 to encourage people to participate in the 1960s campaign, “Plant for a More Beautiful America.”

The campaign was President and Mrs. Johnson’s effort to awaken the country’s conscience about the importance of protecting the state’s native plants and maintaining a sustainable and beautiful environment. The stamps feature some of the nation’s most recognizable landmarks.

PHOTO Jay Godwin, Courtesy of the LBJ Library

PHOTO Jay Godwin, Courtesy of the LBJ Library

42 | WILDFLOWER

Can Do

Beauty on the Balcony

Apartment dwellers can plant Texas natives, too

by Jill Sell

by Jill Sell

44 | WILDFLOWER

Textured pots and accented gold elements can turn any balcony or patio into a stylish native plant display.

PHOTO Sarah Natsumi Moore

VAST ACREAGE AND SPACIOUS SUBURBAN YARDS give homeowners plenty of opportunities to contribute to the world’s much needed greenspace and the Center’s mission inspiring the conservation of native plants. Urban apartment dwellers can also successfully grow many natives in containers on balconies and patios, bringing nature a little closer.