SUBARU BELL 412EPX

SUBARU BELL 412EPX

The most reliable work trucks are transformed and reborn year after year for decades. When you’re fighting wildland fires from the sky, critical moments require experienced and renewed solutions. The upgraded transmission of the new Subaru Bell 412EPX provides 11% more shaft horsepower at takeoff, resulting in a 15% boost in the hot and high hover. Add in an unprecedented increase for internal, external and cargo hook with 1,100 pounds/499 kg payload added. Proven operational readiness now with more payload, more firemen and women, more water…and more power to fight fire.

bell.co/fire

MICHAEL DEGROSKY

and Paudie Mangan of Kerry

and

the

and Fuels Conference in April. Photo by Laura King.

EDITORIAL

Laura King managing editor

laura@iawfonline.org

BUSINESS

Mikel Robinson administration

execdir@iawfonline.org

Kim Skufca advertising associate Kim@iawfonline.org

Shauna Murphy graphic design

Century Publishing, Post Falls, Idaho

COMMUNICATIONS

COMMITTEE (IAWF)

Joaquin Ramirez, chair

David Bruce

Amy Christianson

Lucian Deaton

Jennifer Fawcett

Ariadna Goenaga

Scott Goodrick

Xinyan Huang

Richard McCrea

Tiago Oliveria

Mikel Robinson

Amber Lynn Scott

Kim Skufca

Ron Steffens

Michele Steinberg

Gavriil Xanthopoulos

Scott Goodrick

Ciaran Nugent

David Shew

Laura King

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

David Bruce (Australia)

Natasha Caverley (Canada)

Paul Courtorelli (Canada)

Scott Goodrick (U.S.)

Michael Scott Hill (U.S.)

Michelle Huley (Canada)

Richard McCrea (U.S.)

Diogo Miguel Pinto (Portugal)

Lindon Pronto (Spain)

Daniel Ricardo Maranhao Santana (Portugal)

Cathelijne Stoff (Netherlands)

Anthony Robert White (Australia)

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Kelly Martin (U.S.), president

Trevor Howard (Australia), vice president

Sarah Harris (Australia), secretary

Sara McAllister (U.S.), treasurer

Mikel Robinson (U.S.), executive director

Amy Cardinal Christianson (Canada)

Scott Goodrick (U.S.)

Xinyan Huang (Hong Kong)

Claire Lötter (South Africa)

Ciaran Nugent (Ireland)

Tiago Oliveria (Portugal)

Nuria Prat-Guitart (Spain)

Joaquin Ramirez (U.S.)

Amber Lynn Scott (U.S.)

David Shew (U.S.)

Naomi Eva Stephens (Australia)

Vivien Thomson (Australia)

Tamara Wall (U.S.)

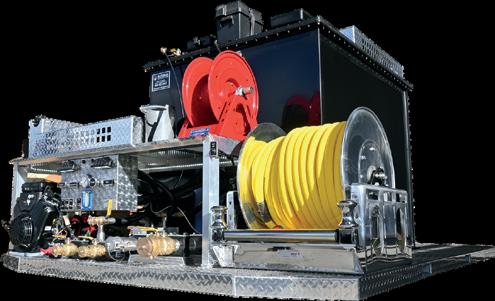

AT-802F Coordinated Flight Groups.

Increase the safety and efficiency of firefighting missions.

This forward-leaning, dynamic response strategy lets incident commanders adapt tactics to rapidly changing conditions. Season after season, dollar for dollar, hour for hour; the Air Tractor® AT-802F proves its value.

Scan to learn more about Flight Groups

BY LAURA KING

In the first quarter 2024 issue of Wildfire, I noted that it’s a remarkable feat, planning a conference that will run simultaneously on three continents.

The 7th International Fire Behavior and Fuels Conference April 15-19 in Boise, Canberra, and Tralee (pages 34-48) was, indeed, remarkable – a global event with dozens of speakers and hundreds of delegates from around the world. There were Americans in Canberra, Australians in Tralee, and Europeans in Boise.

All three iterations of #FBF2024 comprised field trips, presentations, networking, and promises to share solutions rather than have multiple people in different places working out the same problems.

As Richard McCrea writes (page 38), almost 400 delegates from 10 countries gathered in Boise, where the opening keynote session by U.S. Fire Administrator Dr. Lori Moore-Merrill was streamed live to Canberra.

On July 17, Moore-Merrill and the United States Fire Administration released a tool to help communities and firefighters be better informed about wildfire urban interface vulnerabilities – the WUI Awareness | FEMA Geospatial Resource Centre (https://gis-fema. hub.arcgis.com/pages/wui-awareness). The tool helps inform residents in fire-prone areas about wildland fire and explains how embers from WUI fires can ignite their homes.

In March, Moore-Merrill testified before the U.S. Senate committee on homeland security and governmental affairs about the evolving threats of wildland fire, noting that “It is imperative that states and local officials adopt, implement, and enforce the national wildland urban interface building code,” and that “current approaches to wildfire mitigation and management do not match the scale of the issue.”

The USFA and other federal agencies led the Wildland Fire Mitigation and Management Commission, which made 148 recommendations, including putting more focus and resources toward proactive pre-fire and postfire planning to break the cycle of increasingly severe wildfire risk, damages, and losses.

A key theme of the report was modernizing tools for informed decision-making including measures to better coordinate, integrate, and strategically align fire-related science, data, and technology.

As Brad Pietruszka, Dave Calkin, Matt Thompson, and Stephen Fillmore write in A call to action, Rethinking strategy in wildfire response, (pages 24-32), the concept of strategy is often misunderstood and misapplied in wildland fire. The authors “propose the following definition of wildfire strategy: the focused set of actions taken to address incident level challenges, guided by seeking the best balance of risk to lives, communities, and landscapes,” and explore known strategy options – full suppression, point / zone protection, confine, and monitor. Ultimately, the authors conclude that “communicating strategy . . . will be critical . . . What you are doing and why, as well as what you are not doing and why, would describe a chosen strategy in more definitive terms and the current approach.”

Through a journalist’s lens, Lily Mayers looks at strategy and land management on the Iberian Peninsula, the growing incidence of megafires (pages 14-22), and the impact of weather and climate change.

Weather and climate were key topics at the Fire Behavior and Fuels sessions in Canberra (pages 38-40), and Tralee (pages 42-48). Weather was also a topic of conversation in Tralee, with many North American delegates unprepared for the volume of precipitation while the properly kitted Irish hosts simply shrugged off downpours and trudged on through the wind and rain.

Former IAWF board member Steve Miller was on hand in Tralese to summarize three days of presentations, discussion, insight and revelations. Miller’s notes (page 48) are testament to the breadth of discussion, the global nature of the conference(s), and the depth of the takeaways.

It was a remarkable feat, planning a conference that ran simultaneously and smoothly on three continents. More remarkable will be the actions of those who attended to achieve the agreed upon next steps and new approaches to wildland fire management around the globe.

Managing editor Laura King is an experienced international journalist who has spent more than 15 years writing and editing fire publications. She is the Canadian director for the National Fire Protection Associaiton (NFPA), works closely with FireSmart™ Canada to help residents build resilience to wildland fire, and has partcipated in the development of the Canadian wildland fire prevention and mitigatgion strategy.

As a past president (2018-2019) and board member, Alen Slijepcevic continues to work tirelessly for the IAWF, contributing to board meetings, committees, position papers, and conference planning and management. Slijepcevic was a core member of the steering committee for the Fire Behavior and Fuels Conference in Canberra.

As a wildland fire professional, Slijepcevic is a highly regarded powerhouse. With strong foundations in science and operations, as well as experience across multiple continents and countries, Slijepcevic works at the senior level in Australia and provides excellent leadership as well as technical and strategic input to so many state and national issues and initiatives.

Slijepcevic is deputy chief officer, fire risk, research and community preparedness, Country Fire Authority.

Ben Strahan has been a wildland firefighter working with the U.S. Forest Service working out of northern California since 2001, first on engine crews and later as an interagency hotshot crew member.

Strahan has been superintendent of the Eldorado Hotshots since 2020.

Strahan’s nominator for the safety award said: “Being a good firefighter and a good leader are requirements of the job. But here is the thing about Ben that sets him apart: On the one hand he has been relentlessly dedicated to self-betterment, physical performance, and mental health, and on the other hand he has gone above and beyond to understand, embody, and lobby for a safer working environment for all wildland firefighters.”

Strahan has operated as a hotshot leader on many large wildfires in the western United States.

He has advocated for reforms to health and wellness of firefighters and issues such as pay, access to mental health programs, and better working conditions.

Dr. Erin Belval is a research forester with the US Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station.

Since joining the Forest Service in 2021, Belval’s work builds on projects with which she engaged while earning her PhD at Colorado State University, with new energy and attention to critical research needed to support pressing data compilation, complex analytics, and strategic science delivery related to key fire management issues.

Belval is establishing herself as the go to researcher for rigorous science applied to firefighting personal usage and safety. She has led studies related to the wildland fire dispatching system structure and performance and worked to improve the data used to compare fires and the visual delivery of the metrics to decision makers to improve interpretation. Bleval’s research focuses on barriers to change and opportunities for the future, with regard to risk-informed decision making at the regional and national level in wildland fire. She has worked directly with the U.S. National MultiAgency Coordination Center to improve intelligence processes that directly impact dispatch allocation.

Bleval has also led research designed to quantify the impact of pay on wildland firefighter retention and was invited to participate in forecasting wildland fire suppression costs while explicitly accounting for increased fire activity due to climate change.

Dr. José Manuel Fernández-Guisuraga is a postdoctoral researcher at CITAB, Centre for the Research and Technology of Agro-Environmental and Biological Sciences, University of Trás-os-Montes and Alto Douro, in Portugal.

Fernández-Guisuraga masters several tools at state-ofthe-art level, including remote sensing techniques and innovative data analysis tools.

Fernández-Guisuraga published four papers (20202022) in the most prestigious journals of the JCR remote sensing category, including ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing of the Environment.

As a result of his postdoctoral collaboration in an international project of the United States Department of Agriculture and several U.S. universities, FernándezGuisuraga published in 2023 a paper as leading author in which a fundamental driver of the prevailing fire regime in the western United States, the litter accumulation of exotic herbaceous species, was assessed using physicallybased remote sensing techniques for the first time.

Fernández-Guisuraga was the principal investigator in the British Ecological Society International Research Project Exploring the effects of fire severity on ecosystem multifunctionality in fire-prone landscapes (SR22-100154).

The project produced new knowledge about the functions and services of Mediterranean ecosystems that may be more affected by extreme wildfire events. This novel approach is expected to foster substantial advances in the field of functional and applied ecology.

Russell Myers Ross is the program lead, Yunesit’in Qwen (fire) Stewardship, Yunesit’in, British Columbia. Yunesit’in, is one of the six communities within the Tsilhoquot’in Nation.

Myers Ross completed a master’s degree in Indigenous governance at the University of Victoria before returning home to Tsilhqot’in territory, where he was elected chief of Yunesit’in government before the age of 30, serving two terms (2012-2020).

Myers Ross has exercised compassionate and effective leadership through many triumphs and challenges, including the 2017 wildfires that surrounded his Yunesit’in community and devastated much of their territory (totalling 545,151 hectares, the largest fire recorded in British Columbia to that point). As chief, Myers Ross led, managed and supported his community through evacuation and emergency management.

Subsequently, his response and pro-active initiatives included analyzing lessons learned (The Fires Awakened Us, 2018), and taking action to manage wildfire risk while building community response capacity. Most significantly, Myers Ross responded to the wildfires with long-term vision – initiating a program to revitalize Indigenous fire stewardship (cultural burning) practices as a way of healing people and restoring the land, together.

Natasha Broznitsky is acting senior research officer for the BC Wildfire Service.

Broznitsky’s leadership in research integration has been instrumental in fostering collaboration between researchers and operational personnel within the BC Wildfire Service. She has facilitated the integration and investigation of research findings by providing valuable information, acting as a point of contact, acting as a field guide, and facilitating

introductions to other functional areas.

Broznitsky has been an active member of CIFFC’s national Research and Innovation Integration Committee. Her insights and expertise have contributed significantly to advancing wildfire research and innovation on a national level as she also provides valuable input to Canada Wildfire and FPInnovations Wildfire.

Broznitsky brings a wealth of practical expertise including on-the-ground firefighting in initial attack and fulfilling the critical information officer role as well as numerous other functions during response operations. Her involvement in health research projects covering various aspects of wildland fire personnel health underscores her commitment to enhancing firefighter safety and well-being – a mission critical for the sustainability of firefighting efforts into the future.

Oscar Jared Diaz Carrillo is head of the experimental forestry areas of Universidad Autonoma Chapingo, in Mexico.

Diaz Carrillo has dedicated his career to the promotion of academic excellence and the practical application of knowledge acquired at the Autonomous University of Chapingo. His trajectory in fire management began with a firm commitment to conservation and has been an active advocate for the protection of forest cover, contributing significantly to the conservation of approximately 470 hectares of forest and leading reforestation efforts that have resulted in the establishment of more than 36,000 trees.

Diaz Carrillo specialized in fire management science at various national and international institutions, including a professional internship at the National Fire Management of the National Forestry Commission, where he innovatively used specialized software for the study of fire behavior.

As a firefighter and leader in his community, Diaz Carrillo as been part of both local and university fire departments, has implemented advanced fire behavior analysis techniques and participated in prescribed burns for forest fire prevention.

No grinding. No hauling. No obstacles.

Air Burners® is the most cost-effective end solution for wood waste elimination on the market today. For 25 years, our patented air curtain technology has delivered a clean, environmentally-friendly burn with no grinding, hauling, or open pile burning. TrackBoss, the self-contained, fully-assembled, above-ground, pollution-control air curtain burner, reduces slash piles onsite–including whole trees, logs, stumps, and other biomass waste. Forestry services, tree companies, and disaster relief agencies turn to the trailer-mounted mobility of TrackBoss to clear land, brush, and other potential firehazardous natural debris to mitigate wildfires and protect our lands and forests. Contact us for a quote today.

772.220.7303

BY BEQUI LIVINGSTON

As wildfires ravaged the Texas Panhandle in early 2024, and the Sierra Nevadas were under blizzard conditions, it was hard to believe wildfire season had already arrived. As temperatures rise, relative humidity decreases, and the winds begin to blow, all it takes is one small ignition to bring a wildfire to full-force fruition.

Are you ready for wildfire season 2024? As a homeowner, living in the wildland urban interface, have you managed the defensible space around your home and property? Is your go-bag ready with all your important documents, contacts, and medications? Do you have a safety plan that includes ensuring that your children and pets will be taken care of if you can’t make it home? Do you have an escape route and a safety zone? You need to plan now. Don’t wait until it’s too late, and the flames are beckoning at your front door.

know how to unwind and destress during and after a hectic assignment? What else can you do to ensure that you are managing your mental and emotional wellness?

What about relationally? We all know how challenging wildland fire can be to our most valued relationships. Have you developed a plan of action for the people you love most? Have you communicated the effects of being a wildfire responder, and what comes with it? Do your loved ones know where to turn for support, if needed? Our line of work doesn’t just affect us, it affects everyone around us. What if something were to happen to you on the job? Does your family know what to do, and where to turn for help?

How can you become the healthiest version of you, and be the best wildland fire responder you can be?

As a wildland fire responder, are you prepared for wildfire season, and not just physically? Although your physical fitness is of great importance, what about your overall wellbeing? What about your mental and emotional preparedness? Have you been acquiring and practicing skills and tools, such as mindfulness, movement, and breathing? Are you finding healthy coping skills that you can use when stuff hits the fan? What about a plan if you, or someone else, needs support during a crisis? Do you have a list of safe, professional resources? And – importantly – do you

How can you practice selfcare? What can you do to better prepare for what’s to come? How can you find healthy modalities and tools to help manage your stress? Can you muster the courage to speak your truth, with authenticity, even when others may not want to listen to what you have to say? What about setting healthy boundaries, on and off the job, including learning how to say no? What about asking for help, when needed, and then being able to receive it? These steps should be included in your personal wellbeing plan. How can you become the healthiest version of you, and be the best wildland fire responder you can be?

Here are a few practices that you can incorporate now, and take them into wildfire season:

• Learn and practice mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR): This is a simple yet profound tool that can be used any time, in any location, including the fireline. Check out The Mindful Center, http://themindfulcenter. com

• Somatic movement: This movement program works with your autonomic nervous system to help you destress and mitigate injury by helping the body find its natural movement pattern. Visit Somatic Experiencing International, https://traumahealing.org

• Breathwork: Although breathing is essential to life, health and wellness, certain breathing techniques are useful for mitigating stress and helping an overwhelmed nervous system find balance. Visit Breathwork for First Responders at www.breatheology.com/breathwork-forfirst-responders/

Only you can take care of yourself before, during, and after wildfire season. May you be safe, may you be healthy, and may you always listen to the wisdom of your nervous system and your heart, because they will always tell you the truth.

Bequi Livingston was the first woman recruited by the New Mexico-based Smokey Bear Hotshots for its elite wildland firefighting crew. She was the Regional Fire Operations Health and Safety Specialty for the U.S. Forest Service in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Contact her at bequilivingstonfirefit@msn.com

BY MICHAEL DEGROSKY

I was home for a couple of days when I realized I had hit the wall. I had planned to work from home for two weeks while some controversy played out at work but, within days, I announced my retirement. Mine was a tough job under the best of circumstances. Relentless workload, lots of people, cumulative stress and fatigue, too little time to step back and recover. Now, a new challenge felt like one too many.

Honestly, when I decided to retire, I wasn’t sure why. I loved the responsibilities of my job. I had assembled a great team, training and core fire season were nearly upon us, we were doing great work, and I had not intended to retire for another six months to a year. However, suddenly my stress seemed unending, I felt inefficient, cynical, and exhausted – what I now know was classic workplace burnout.

According to the American Psychological Association (APA) and the World Health Organization, “Workplace burnout is an occupation-related syndrome resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed.”

Credible research suggests several negative health outcomes associated with burnout ranging from musculoskeletal pain to depressive disorders and cardiovascular disease. According to the APA’s senior director of applied psychology, people suffering burnout are less productive and more error prone. Absenteeism due to illness increases. Clearly, burnout is bad for us as individuals and leaders.

The essence of leadership lies in influence through relationships. Leadership happens between people and is a process in which leaders and followers engage together. In that process, leaders matter because they help direct, mobilize, and align people and their ideas. Leaders have power, responsibility, and authority, and all must be used responsibly. And then, of course, people rely on their leaders and expect a lot of them.

Therefore, it is easy to see how a person’s leadership suffers when the pressure of those responsibilities, other people’s expectations, and various burdens that come with leadership – such as isolation –become overwhelming; business and leadership writers have dubbed this leadership burnout. Evidence from several well-known business surveys makes clear that leadership burnout is a growing problem, and recent research indicates that the majority of leaders have experienced it

From what I’ve been able to learn, expectations of self-sacrificing service are contributing to an epidemic of leadership burnout.

indecisive, lose confidence in their choices, and engage less with the people they lead. In my case, in addition, I lacked confidence that I could regain my productivity or perform at my best.

In an excellent 2023 Harvard Business Review article, Kandi Wiens, a senior fellow at the University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education, wrote about the cynicism accompanying workplace burnout. “Cynicism is dangerous to both individual and organizational health,” Wiens said. “It can quickly overtake our thoughts, resulting in overwhelming negativity, irritability, and pessimism.” While, at the time, I had not yet recognized my leadership burnout as such, those observations about cynicism are spot-on with my experience.

Perhaps the worst part for me was that I was losing confidence in my own leadership and feared that perhaps I had become a negative influence on the people for whom I was responsible. According to Wiens, my fear was not unfounded, noting that “Cynicism can rapidly spread throughout teams and organizations through a phenomenon known as ‘emotional contagion.’ ”

It stands to reason that burned-out leaders simply cannot be effective leaders and it is for that reason that I believe leaders must place a high priority on their own well-being. Advocating for self-attention can make one seem like an outlier in leadership circles these days. People have re-discovered servant leadership and it’s a hot topic. Others are selling

“extreme” and “radical” team leadership concepts left and right. But from what I’ve been able to learn, expectations of self-sacrificing service are contributing to an epidemic of leadership burnout. It is no coincidence, for example, that the resurgent interest in servant leadership comes at a time when some researchers are also suggesting that a servant leadership orientation may be inconsistent with the demands of leading in contemporary organizations.

I contend that we cannot be anyone’s loyal servant or awesome team lead if we are burning out. It took me a while to recognize my experience as burnout and considerable time and effort to work my way out of its effects. While all is well now, I do not recommend that journey. These days, I believe that serious leadership practitioners will learn about leadership burnout, remain vigilant to its causes and effects, and assure that they, and the leaders they lead, have ample opportunity to, at very least, manage workloads as well as step back and recover to relieve cumulative stress and fatigue.

Mike DeGrosky is a student of leadership, lifelong learner, mentor and coach, sometimes writer, and recovering fire chief. He taught for the Department of Leadership Studies at Fort Hays State University for 10 years. Follow Mike via LinkedIn.

BY LILY MAYERS

As the incidence of mega fires intensifies across the Iberian Peninsula and around the world, experts in fire operations and research say it’s critical to acknowledge the precursors of extreme wildland fires and understand what fuels the severity and scale of these large phenomena.

Fierce and erratic mega fires have become a staple chapter in southern European summers.

Lacking international consensus on the specifications of mega fires, an accepted definition is fires that burn an area of more than 5,000 hectares or emit more than 10,000 kilowatts of energy per square meter.

What sparks a mega fire is not what determines its behavior, size, or its speed, nor does understanding how a fire started hold the solution to preventing future catastrophic wildfires.

Three critical variables fuel mega fires: uninterrupted expanses of forest; dense, flammable overgrowth; and the convergence of unstable atmospheric and climate conditions. The catalysts – continuity, density and weather – mean the difference between a fire burning out, and one capable of generating enough momentum to surge across the line of control.

Mega fires have been recorded as far back as 350 million years ago but due to dramatic shifts in land use and with the accelerant of climate change, they are becoming more frequent, more destructive and affecting new geographic regions. In 2023 Greece experienced the worst fires in European record with more than 94,000 hectares of land burned in a single event and at least 28 people killed. The deadly Hawaii firestorm in Maui killed more than 100 people and decimated the town. Dwarfing all other countries in 2023 was Canada, where more than 15 million hectares burned – more than double the 1995 record.

The effects of these devastating mega fires are something fire-prone Spain and Portugal understand intimately. In the last 17 years, the countries have cumulatively burned ore than 3.1 million hectares of land to wildfires.

Experts agree one of the most significant causes of mega fires is the expanding continuity of global forests. In the context of mega fire danger, unmanaged and abundant tree areas are an enemy hiding in plain sight.

Spain’s treeline has exploded in growth over the last 30 years while Portugal’s has declined. After huge treeline increases in the second half of the twentieth century, experts say Portugal’s forest recovery was delayed by land-use changes together with several fire events after the 1990s that severely scarred the country.

“Contrarily to other European countries and especially Spain, [in Portugal] we don’t see this expansion of forests, what we see clearly is more the loss of agriculture in between forests and shrubland patches, which again reinforce the propensity to have increasingly larger fires,” said Paulo Fernandes, forestry engineer and senior researcher at Portugal’s University of Trás-os-Montes and Alto Douro. But even with the losses and slow regeneration, the country now has more trees than it can manage.

“The last time we had so many forests was by the beginning of the neolithic,” Fernandes said.

As of 2021, about 56 per cent of Spain’s land was covered by forest ecosystems and every year that number grows. To reduce fire risk, experts say the country actually needs fewer trees and shrubs.

Forest continuity is predominantly the fruition of neglected land. After managing and using most of

Spain’s forests for thousands of years, the abandonment of agricultural lands and rural towns throughout the mid-20th century facilitated an unfettered expansion of trees. As farming families sought greater employment opportunities with increasing industry in capital cities, trees and shrubs enveloped their fields, blurring parcels of cultivated land into homogenous forests. This relentless reclamation of nature has resulted in expansive forest spaces as well as two of the largest demographic deserts in Europe known as the Spanish Lapland and the Celtic Strip.

Without interruptions in forest continuity in the form of heterogeneous mosaic landscapes, clearings and agriculture, fires can spread indiscriminately. One of the Peninsula’s most critical cases of fuel continuity is in the lower Pyrenees. Forests cover 59 per cent of the mesic mountain range, according to the Pyrenean Climate Change Observatory, with the most uninterrupted expanses in the central eastern regions. Carbon studies have traced the mountain’s coniferous pine forests back between 50,000 and 15,000 years. In the past century, however, this resilient forest’s treeline has bulked up and crept to higher altitudes.

Like most forest environments across the Iberian Peninsula, the Pyrenean landscape has undergone

multiple land management changes throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

“All forests are an expression of our social and natural history,” said Marti Boada, a professor, geographer, and author. The 73-year-old Catalan grew up in the prePyrenees and has dedicated his life to understanding forests across the Peninsula and the world. Along with his exhaustive research, Boada has witnessed firsthand the changes Spain’s forests.

“The biggest change is the energy change, when hydrocarbons arrived en masse in the 50s or 60s . . . People no longer cooked with charcoal or firewood,” Boada said.

“What was previously about five tonnes per adult per year in forest consumption, is now five butane cylinders; this is key.”

When the forests stopped being utilized, trees reclaimed the space.

The most effective way of seeing the impact a rural exodus has on forest spread is from above.

“In the 60s we in Catalonia had 37 per cent of the surface covered by forest area, and now we are at 72 per cent,” Boada said. That surge in trees has meant a simultaneous increase in the forest’s demand for water.

“If you had about 2,000 trees per hectare and now you have more than 20,000, it is as if you had 10 geraniums in your home and you added 100. And you can see this, that is, the river flows have dropped, the aquifers have dropped also.”

Water stress is one of the leading causes of forest mortality in the Pyrenees, which currently sits at around 38 per cent. And the higher the forest mortality, the higher the mega fire danger.

“With this heat, ignitability can come to you in the most unexpected way,” said Boada, “Not only the prePyrenees but all of the Ebro Valley is going to burn.”

It’s a dark prediction but one echoed by other experts. While fires in the Pyrenees are rare, simulations developed by Catalunya’s forest fire service found if a fire were to start under heightened meteorological conditions, it would have the potential to burn through an enormous amount of land based on the current fuel levels.

“So right now we have three per cent more chances than we used to have in 2015 of having an event that can support a fire spreading for more than half a million hectares in the Pyrenees, even reaching one million hectares,” said Marc Castellnou Ribau, inspector of Catalunya’s internationally recognized Forestry Action Support Group (or GRAF) and a leading expert in fire extinction.

“So that was impossible 10 years ago. It started to be possible but rare in 2015, and now there’s a good chance for that to happen. All the elements are ready to cook the recipe, it is just a question of when.”

An important role in this transformation can be played by pyrocumulus, large clouds originating from the intensity of the flames of a fire and like those generated by volcanic eruptions. The mass of warm air made of water vapor and ash rises at high speed and condenses when it meets a cooler environment. Pyrocumulus can cause thunderstorms and electrical activity; they are capable of generating bursts of rain and spreading small particles of ignited matter, to create new fronts or secondary fires.

If a fire did start in the Pyrenees under high fire danger conditions, the simulations predict it wouldn’t take long to develop into a mega fire. “It needs one day to start and build pyroconvection, one long night where the pyroconvection is maintained and the second day when it finally blows up. That’s the process,”said Castellno. “There is a lot of evidence of mountain areas around the world going through the same process and the Pyrenees are no different.”

The region has become Castellnou’s team’s most critical focus area. “It is where the big fire can happen and where the most efforts to convince society that we must manage the landscape is.”

Graciela Gil-Romera, an expert in fire paleoecology at the Pyrenean Institute of Ecology, a research center within the Spanish National Research Council, agrees the current forest spread in the Pyrenees creates a very dangerous situation.

“Having such continuity of fuel in the scenario of global warming, that’s a bomb,” Gil-Romera said, “Sometimes you have the urban forest boundary mixing with the wilderness and that’s when the critical thing happens. Because then you may have a fire start which might not be intentional and then it spreads with no end, and

there’s nothing, no means that can stop the fire.”

Wedged in by this prospective fire fuel are the small rural towns and urbanizations dotted across the mountain range; residents will find themselves in the eye of the storm should a mega fire ignite, something that deeply concerns Castellnou, who sees new homes continually built in the path of future fires.

“The population is living calmly on a Mediterranean coast or in a boreal forest because they think a devastating fire cannot happen because the extinction systems have been saying they can put out the fires,” said Castellnou. “But we are not explaining the whole truth. We can no longer put out those fires. We are not prepared [for mega fires], although we have been warned.”

Wrangling continuity is an endless battle against nature’s unrelenting growth but it is also a result of fast and effective firefighting operations. This concept is known as the fire paradox because the success and efficiency of extinction operations over decades has directly contributed to an increase in the fuel continuity and therefore fire danger.

Unlike surface level prescribed burns or small grass fires, mega fires damage plant tissue and cause

long-term scarring, delaying landscape recovery. This paradox has led to calls for a shift in focus from solely reactive extinction operations to proactive fuel management.

“We need to think that fire is part of our ecosystems in the Mediterranean forests,” said Sergio de Miguel, associate professor of the University of Lleida and researcher of global forest ecosystems. “We have to live with fires and we can, through management, decide how they occur,”.

If this change were realized it would also be a significant cost-saving measure. “Why? Because we respond, not to what is burning but to what could burn,” said Castellnou. He says current firefighting operations cost about 20,000 euros per hectare, while the average cost of managing a hectare of land is between 2,000 and 3,000 euros.

Knotted within the forest walls is the second variable fuelling mega fires: density – the vertical and horizontal build-up of vegetation undergrowth which acts as a ladder during a fire, capable of distributing fire to other trees and rapidly lifting flames from the forest floor

up to the canopy. A forest’s mass of ladder fuels will determine how hot a fire burns and how fast it travels. To get a rough idea of how dangerous the fuel load of an area is, forest engineers use a simple rule of thumb simple formula: If a square meter of land holds more than a kilogram of dry litter or shrub, that indicates it could burn at 10,000 kilowatts per meter, equivalent to the magnitude of a fire that cannot be successfully fought.

At its heart, forest density is an absence or failure of fuel management. Throughout the Iberian Peninsula there are extensive areas of high vegetation density. Portugal’s central region is the country’s most dense, and an example of how good and bad forest management can affect fire behavior.

“That’s the big problem with these large, very continuous, very dense forest patches that are so characteristic of central Portugal,” said Fernandes. “It began by being planted, supposedly it would have to be managed in an orderly manner, but it has become a certain jungle, so to speak, of trees of various sizes and heights, but always in great density and therefore enhancing extremely intense fires.”

Fernandes believes the region suffers under the weight of so much forest mass mostly due to a lack of clearing by small private landowners.

“The soils are not at all good for agriculture and the use of forestry from the mid-twentieth century became . . . the obvious option or the only option in terms of economic income for the population. The entire area was initially forested with pine and later with eucalyptus. The problem is that in these plantations, especially after fires, the intensity of the management is generally very reduced.”

Portugal is ranked seventh in the top 10 countries with the highest proportion of forests under private ownership, accounting for 95 to 97 per cent of the territory’s total forest area (much like the neighboring Spanish province of Galicia.) Most of these properties cover less than 0.5 hectares of land however many owners are still unable physically or economically to actively manage their fuels.

“There is no forest management, and in many situations, there is no professional management,” Fernandez said. “When there is some, it is in forests managed by companies. These types of forests or plantations are inherently vulnerable to fire due to the accumulation of biomass by the species that are used, which are normally fast growing like pines or really fast like eucalyptus.”

In Spain similar examples of worrying forest density can be found. In the province of Extremadura many farms

and olive groves have been left abandoned due to a drop in profitability and the toll of labor. Jesús Campo García is among those who have walked away from their plots. The 72-year-old has spent his life in and around Monfragüe National Park in the municipality of Serradilla working as both a forest agent and an olive farmer.

“There is nothing managed here in La Solana other than a few farms right next to the road, they are the only ones. Everything else is completely lost, everything,” he said. During Garcia’s 25 years working as a local forest agent, he witnessed the landscape change, the shrubs build up and the fires intensify.

Aiding in the crowding of forests has been the gradual tightening of important conservation regulations on natural spaces, especially in Spain. The environmental protections needed to preserve biodiversity and habitats have been strengthening since the second half of the twentieth century. In Portugal, 22.4 per cent of the land is defined as protected areas and in Spain 28 per cent. Many protected areas form part of a chain of European forests known as the Natura 2000 Network and their protections mean that to preserve the native plants and wildlife, limitations are enforced on the ability to manage the fuel buildup, carve fire breaks, and perform prescribed burns. That’s why in some parts of the Peninsula, largely in Spain, experts are concerned

the restrictions risk endangering the subjects they were created to protect.

In the 2022 fire season, 42 per cent of the total razed land in Spain was within Natura 2000 sites, with the Sierra de la Culebra in Zamora, Alto Palancia in Bejis, and Serra do Courel in Galicia the worst affected. In Portugal, 37 per cent of the fires were in protected Natura 2000 sites, with the worst affected in the Serra da Estrela Nature Park and the Alvão Natural Park. This follows a trend in recent years where protected areas appear to be having an increasing vulnerability to fires. In Portugal protected areas pose less of a problem, due to more relaxed clearing policies allowing an easier balance between nature and people.

In Spain, fires within the Natura 2000 Network have been found to be on average twice as destructive as those originating outside, according to the Spanish Government’s Los incendios en la Red Natura 2000 report. “There are two take-home messages here,” said scientist and forest engineer Victor Resco de Dios of the of the University of Lleida, who co-authored a study into the drivers of the 2022 fires. “One is that protected areas are not protected against fire, they do burn, so fire prevention must happen there and in some areas, we see protected areas burning more than they should based on the area they occupy.”

Some of the most significant precursors to mega fires are impossible to see but essential to understand; humidity, wind and increasing temperatures are among them.

The relationship between vegetation and its access to water, both through the earth and the atmosphere, directly influences flammability and therefore mega fire risk at all times. When temperatures are high and relative humidity is low, plants want to retain as much water as possible, so they must choose between growing or surviving. In either case, plants are left with a lower moisture content and as a result burn faster.

Researcher Javier Madrigal from the Forest Fire Laboratory of INIA-CSIC in Madrid says a plant’s flammability is partly determined by its characteristics, such as thickness, however, it will mostly be influenced by the amount of water inside it. “That doesn’t mean to say that a wet tree does not burn, because if there is a lot of energy everything will be lost, but it gives us an idea of the ease with which one process can occur with respect to another.”

Dry weather and a lack of rainfall translates to drought. The Iberian Peninsula periodically experiences long stretches without sufficient rainfall. For Spain, the drought of 2019 to 2023 could have a lasting effect on mega fire danger.

“All climate models say that it will last for decades because it is not only a temporary drought, but a global circulation change, so we will see a total change of our landscape in the coming decades because we are changing the water regime,” said Castellnou.

Dry lightning storms seize the parched and dead fuels. Fires started by lightning account for only a small percentage of total fires in Spain and Portugal but they are increasing in frequency and burning larger areas of land, presumably because they can ignite during a moment of heightened atmospheric instability, often in densely forested areas away from high surveillance and are capable of igniting multiple fires simultaneously.

“When a fire occurs in those [dry lightning] conditions what it really does in the atmosphere is throw the flame front literally upwards, it draws the flame front towards itself and accelerates the combustion process,” said Madrigal.

Back on land, topography also plays a big role in determining mega fire direction and intensity. If an area is inaccessible to people or machines, not only will the fuel be unmanaged but when a fire starts it can’t be controlled. The formation of the land itself also has the potential to shape the fire’s progression, influencing direction through the aspect and degree of slope and the creation of wind channels.

Accelerating and exacerbating these factors is climate change. Not only does human-caused climate change lengthen the fire season, it also increases the frequency and intensity of mega fires. Tiago Oliveria, president of the Portuguese Agency for the Integrated Management of Rural Fires (AGIF), describes the challenge as one without a hero.

“Do you know any hero the world recognized because he prevented an event that didn’t occur? It’s not popular, so we are facing a dilemma here. We know

how to do it, [prevent fires], the money is flowing in the proper direction, but we are not doing it as fast as it is needed.

“There is a joke people who work in these types of phenomena use. It’s that a guy is jumping from the tenth floor and he is skydiving to the ground and on the second floor, he says, “So far, so good.” It’s a dark joke but it describes a little bit of what we are envisioning. If you don’t treat the vegetation, the only solution you have on that critical day, it’s evacuation. You cannot fight that fire unless you have fuel management.”

This article was developed with the support of Journalismfund Europe.

Lily Mayers is a cross-platform freelance journalist from Sydney, Australia, based in Madrid, Spain. Mayers’ career began in television and radio news for Australia’s national broadcaster, the ABC. Since moving to Spain in 2020, Mayers’ work has focused on the long-form coverage of world news and current affairs.

Mikel Konate is a freelance visual journalist focused on migration, conflicts, and the climate crisis. Konate’s work has been featured by major international media outlets and earned him a Rory Peck Trust Award.

Paulo Nunes dos Santos is a freelance photojournalist and reporter covering armed conflict, humanitarian crises, political instability, and social issues worldwide. Nunes dos Santos is a frequent contributor to international publications including The New York Times and Jornal Expresso.

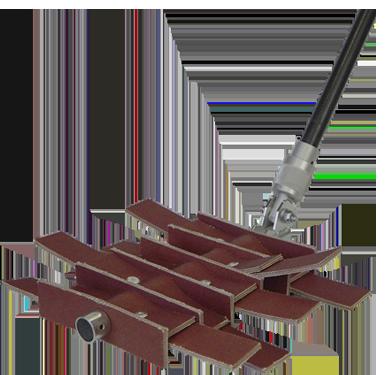

Six decades of unwavering commitment to precision and advancement have shaped the MARK-3® pump into a symbol of reliability and cutting-edge technology. From the front lines to the heart of communities, the MARK-3® has stood the test of time, ensuring that tahe spirit of innovation continues to flow.

waterax.com

BY BRAD PIETRUSZKA, DAVE CALKIN, MATT THOMPSON, AND STEPHEN FILLMORE

Expected future scenarios including climate change, a greater incidence of urban conflagrations, and continued fuel-load accumulations will increase demands on the wildfire management system in the United States, resulting in increased difficulty managing wildfires. There is a need to expand concepts of effectiveness to manage more extreme and complex events.

Fires nominally managed under the same defined strategy (for example, full suppression) can have widely divergent resource needs, tactics, and timeframes. The increase in hazards during wildfire operations is leading to shifts in how fires are engaged, even when rapid containment is the most desired objective. The need to improve systems of understanding, developing, and communicating wildfire strategies is a key source of leverage to mitigate the consequences of increasing workload and complexity on a system under duress.

Ensuring sound strategy is essential as wildfire response systems continue to be tested by these pressures. However, these issues, as well as many unforeseen, will challenge our ability to effectively convey the rationale behind a chosen strategy, connect it to outcomes, and learn from it.

The current understanding and approach for developing and communicating wildfire response strategy is insufficient to meet these challenges.

Arguably, some of these issues are systemic and originate at least in part from the current framing of the problem, in which the wildfire itself is the problem.

There is an urgent need to convene greater dialog within the fire management community around the idea and application of strategy. Given the recent evolutions in strategic guidance, now is an opportune time. The USDA Forest Service issued a Wildfire Crisis Strategy in early 2022 that emphasizes returning fire to fire-prone forests. The National Cohesive Wildland Fire Management Strategy was updated in 2023 with an addendum that also identifies a need to increase the use of proactive fire. The US Wildland Fire Mitigation and Management Commissioner’s final report similarly echoes these aims. The wildland fire community has a unique window of opportunity to capitalize on the convergence and momentum of these calls for change.

The concept of strategy is often misunderstood and misapplied; improvement of the core concept is critical to improvement. The US Marine Corps War College Strategy states that “In its simplest form, strategy is a theory on how to achieve a stated goal.” Within the world of wildland fire, we can and do learn from military strategic victories and defeats, yet the framing of these lessons is around the outcome of the battle,

with less attention paid to the uncertainties faced and trade-offs made by commanders. There are valuable lessons in understanding key tenets of applied military strategy, yet wildland fire practitioners must reckon with the fact that war with fire, as viewed in the traditional sense, is inherently un-winnable. Fire and land managers must begin to think about wildland fire differently to make progress against the threats it poses.

Other fields, such as business management, have similar views of strategy, but framed with alternative lenses and complementary insights. In a 1996 article What is Strategy, Michael Porter describes the essence of strategy as making trade-offs, choosing what not to do, and deploying a system of combined, aligned activities. In the book Good Strategy / Bad Strategy, Richard Rumelt says strategy requires diagnosing the challenge to be overcome, providing guiding policies, and identifying a set of coherent actions; doing this frames the addressable challenges to be surmounted and then establishes overall direction and guardrails to implement actions. Both authors suggest that strategy is about problem solving through creativity, design, and iteration. Importantly, by first understanding the problem and framing it correctly, objectives become

not about predefined inputs into a decision process, but about meaningfully measuring progress towards achieving the strategy.

In other words, objectives emerge from the process of strategy setting – they shouldn’t pre-empt it. Objectives are unsupported if they come before critical analysis of a challenge. While goals should guide the direction organizations take, objectives should measure progress toward achieving strategies that overcome specific problems. In sum, strategy setting is about problem framing, focus, co-ordination, and tailoring solutions to specific problems or opportunity – and there is no one-size-fits-all approach.

The Incident Status Summary (ICS-209) reporting system provides four incident strategy options from which fire managers can choose. Through our research and professional observations, we believe that none of the four options provides a holistic representation of a strategy on their own, or in combination. Also, simply reporting portions of each option does not solve this. The current definitions of each ICS-209 strategy option are shown on page 28.

“. . . put the fire out as efficiently and effectively as possible while providing for firefighter and public safety. This includes completing a fireline around a fire to halt fire spread, and cooling all hot spots that are immediate threats to control lines or outside the perimeter, until the lines can reasonably be expected to hold under foreseeable conditions.” Full suppression is synonymous with “full perimeter containment” and “control.”

protects specific assets or highly valued resources from the wildfire without directly halting the continued spread of the wildfire.

CONFINE restricting a wildfire to a defined area, primarily using natural barriers that are expected to restrict the spread of the wildfire under the prevailing and forecasted weather conditions. Some response action may be required to augment or connect natural barriers (e.g., line construction, burn-out, bucket drops, etc.).

. . . the orderly collection, analysis, and interpretation of environmental data to evaluate management’s progress toward meeting objectives and to identify changes in natural systems particularly with regards to fuels, topography, weather, fire behavior, fire effects, smoke, and fire location.

Full suppression appears to be applied most often when a fire is considered an acute problem, solvable only by making the fire go away rapidly. Agency employees and the public can take the view that using any other listed strategy indicates a desire or willingness to allow fires to burn unabated. However, the only strategy that places a values-based judgement on a fire is full suppression, as it identifies the fire itself as the challenge to be overcome and uses an inapplicable problem frame. Confusion also arises because the definition of full suppression does not dictate where, when, or in what fashion a fireline must be completed around the fire. Nor does the 2009 Guidance for Implementation of Federal Wildland Fire Management Policy indicate when, where or how a fire should be suppressed when the full-suppression strategy is chosen. In fact, managers may implement a variety of tactics to achieve full suppression. Indirect control lines located miles from the final perimeter are commonly used during full-suppression fires, yet the reasons underlying these decisions are not always well conveyed internally or externally, leaving communication gaps for the rationale behind fire-management decisions.

Complicating the matter, some fires that achieved resource objectives (such as improving wildlife habitat

or watershed functionality) may have appeared to the public to have been intensively managed, particularly if fire crews spent numerous days completing firing operations – identical in appearance to indirect tactics that achieve full suppression. Or, as research has shown, other fires that are described to the public as full suppression may not see a firefighter directly engage with the fire at all. Given how different managerial intent can translate into nearly identical implementation actions, we believe it is time to revisit not only how wildfire strategy is reported but also how it is communicated.

As discussed, framing the problem is critical to developing strategy. A strategy built to simply eliminate a fire from existing is a poor one – just as a strategy built to simply allow fire to burn unabated would be. The perceptions of good or bad placed upon fires are social-based moral judgements that differ among individuals; this creates an impossible perspective from which to develop and apply sound strategies. The way people feel about any wildfire is irrelevant; the fire itself does not share any of those concerns – it simply exists, creating risks that must be addressed.

More than a century of fighting wildfire in the United States has created an acknowledged fire paradox; past wins (successful suppression) have significantly contributed to current losses (the wildfire crisis). Viewing fire as the enemy to overcome continues an unsustainable cycle of fire exclusion, resulting in increasing costs and losses. Reframing the understanding and communication of the problem may improve outcomes. We propose the following definition of wildfire strategy: the focused set of actions taken to address incident level challenges, guided by seeking the best balance of risk to lives, communities, and landscapes.

We offer several ideas for improving strategy. First, we believe a big part of the solution is a fundamental shift in how the wildfire problem is framed. Describing specific challenges presented by a fire that need to be overcome, and why, could improve communication, versus describing only actions unlinked from the meaning behind them. Specific and clear language is necessary to communicate the risks to values and firefighters, and the trade-offs that managers must make to limit those risks as fully as practicable.

Developing strategies framed around specific addressable challenges has had some success in the United States with the evolution of the Incident Strategic Alignment Process (ISAP). ISAP is a continuation of previous risk management efforts, such as the 2016 USDA Forest Service’s Life First Initiative, which led to the advent of Risk Management Assistance Teams from 2017 to 2019. ISAP provides a framework through which agency administrators and incident management teams can anchor strategic conversations to a set of four pillars: critical values at risk; strategic actions; responder risk; and probability of success. This framework allows managers to have risk-informed dialog with key partners, stakeholders, and Indigenous leaders while developing strategies that leverage analytics and data in addition to experience and judgement. Discussing risks to lives, communities, and landscapes instead of debating and reporting categorizations such as full suppression or monitor, may improve the basis upon which strategy is built, communicated, and applied.

WE PROPOSE THE FOLLOWING DEFINITION: WILDFIRE STRATEGY IS THE FOCUSED SET OF ACTIONS TAKEN TO ADDRESS INCIDENT LEVEL CHALLENGES, GUIDED BY SEEKING THE BEST BALANCE OF RISK TO LIVES, COMMUNITIES, AND LANDSCAPES.

ISAP leverages several spatial risk-management products, collectively referred to as risk management assistance products. Tools such as potential operational delineations or PODs, suppression difficulty index or SDI, potential control locations or PCL, snag hazard, and other layers are available pre-season and CONUS wide. Continued investment in these types of decision-support tools is critical to improve strategies, while understanding that experts and novices use information differently, and that improving data quality alone does not improve decision quality. There must be simultaneous investment in the tools while training the workforce to use them.

Second, there is room to improve assessments and understanding of probability of success. How likely is a strategy to succeed, and are the potential benefits of a decision meaningful enough to act upon? These two questions comprise a critical element of any strategy and should inform any deliberation of whether the risk is warranted, as no action undertaken is guaranteed to be successful.

Recent research on fireline effectiveness shows that on large fires in the United States, only about one in three miles (33 per cent) of constructed fireline ends up containing fire spread. According to Paul Slovic and others in 1985, “. . . intelligent people have great difficulty judging probabilities . . . ”. Decision makers must consider both facts in attempts to improve strategy. The mismatch between assessed and observed outcomes can, in part, be explained by the overconfidence effect, but it is feasible and critically important to assign a reasonable estimation of the probability of success to make decisions based on the expected value of the outcome.

However, a low probability of success on its own does not mean an action should be dismissed. An action with a low probability of success may be justified if the payoff is very high and risks to responders can be mitigated to an acceptable level. Conversely, an action that may be very likely to succeed yet results in very little benefit must be subjected to scrutiny. As evidenced from the United States’ initial attack success rate of 90 per cent, the undertaking of high probability of success actions on a large scale (initial response focused on minimizing fire size) has resulted in the remaining two per cent of ignitions burning in unbroken fuelbeds that are more prone to high severity and rapidly spreading wildfire. Linking the

assessment of uncertainty to the expected result of the action is critical to improving decision making and strategy development.

Third, senior leaders could provide guiding policies that include clear articulation of their risk appetite and risk tolerance. Specifically, leaders could move away from qualitative assessments that define risks as low or high, and move toward quantitative descriptions of risk. These descriptions should be aligned in terms of severity, followed by a determination of the tolerability of each to understand and communicate enterprise risks. Indeed, including sociopolitical, economic, and career risks must be considered in this exercise. Only after completing this process can individual wildfire strategic decisions align with organizational risks. Absent clarity on enterprise-level risks, the system will continue to be noisy, and we will continue to fall back on institutional biases such as the default to aggressive wildfire suppression.

Fourth, we believe there is an opportunity for wildfire management in the United States to undertake a systematic decision audit, reviewing and daylighting examples of acceptable risk trade-offs even when bad outcomes occurred, and finding acceptable outcomes as the result of unnecessary and unsustainable risk taking. Individually, we must hold ourselves accountable, but organizations must also be held accountable, set clear expectations and provide appropriate methods to consider trade-offs among competing priorities and their conditions for success.

Fifth, establishing consistent time horizons for assessing risks that get us wildfire response out of the short-term emergency response mindset and working toward a long-term stewardship mindset could help foster improvement. Failing to do so do so will enlarge the burden on an already strained wildfire response system. The tendency of people to accept lower benefit in the short-term despite their future selves regretting that decision is called hyperbolic

discounting and is one of the key contributors to the wildfire crisis. To move beyond this bias, incident strategies must be developed with both short- and long-term impacts in mind. To be clear we are not advocating to dismiss short-term threats but if incident strategies are limited only to a small temporal horizon, long-term outcomes will continue to suffer. Importantly, a longer-term focus may improve communicating short-term disruption such as smoke impacts from either prescribed or wildfires in terms of future risk reduction.

Finally, we the wildfire response system need to embrace a learning culture, which likely means initiating a broader dialog that changes the understanding of strategy, its implementation, and its implications. Truly embracing a learning culture also means allowing the application of military lessons of strategy yet fundamentally reframing and moving from the war on fire to living with fire. Changing this paradigm will certainly mean measuring performance and modifying behaviors when gaps are identified. Organizationally, we must span boundaries, from fire managers to agency administrators certainly, but also bridge the gap between scientists and implementers. No group in the wildland fire system fully understands the others, yet all are dependent on one another to improve. The entire system must recognize that our collective history got us into this paradox and that doubling down on the status quo is not going to lead to changes that are long past due. If you find yourself in a hole, the first rule is to stop digging.

Societal expectations drive managerial incentives, and status quo is usually safer professionally than trying something different. Anyone who becomes a wildfire decision maker must understand how difficult their choices will be, and how often they will face criticism because of them, regardless of the choice’s quality. Communicating strategy, particularly the feasibility of that strategy, both at the near- term (incident level) and longer term (landscape condition) will be critical to this work. What you are doing and why, as well as what you are not doing and why, would describe a chosen strategy in more definitive terms than the current approach. At its core, the question becomes how do we best reduce risk and complexity – not only for an individual fire, but for coming years and decades. In other words, how can this be done durably and systematically?

While certainly not the only answer, we believe that part of the answer is a better understanding and execution of strategy.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent any official USDA or U.S. government determination or policy. This research was supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service.

This material was prepared by federal government employees as part of their official duties and therefore is in the public domain and can be reproduced at will. Inclusion in a private publication that is itself copyrighted does not nullify the public domain designation of this material.

A wildland fire strategy needs to consider how decision makers can best reduce risk and complexity – not only for an individual fire, but for coming years and decades. Photo by Ari Lightsey.

Brad Pietruszka is a fire management specialist with the Rocky Mountain Research Station, Human Dimensions Program, Wildfire Risk Management Science Team. His position spans boundaries between research and practice, aligning the needs of the field with research directions and encouraging the adoption of the best available science in fire management. Pietruszka spent most of his career in fire and fuels management in several federal agencies before joining the WRMS team, and is a complex operations section chief, strategic operational planner, and long-term analyst. He is a co-developer of the incident strategic alignment process for strategic risk management in wildfire response.

Dave Calkin, PhD, is a supervisory research forester with the Rocky Mountain Research Station, Human Dimensions Program, Wildfire Risk Management Science Team. Calkin’s work is designed to improve risk-informed decision making through innovative science development, application, and delivery incorporating economics with risk and decision sciences. His research interests include risk assessment, collaborative wildfire mitigation and response planning, suppression effectiveness, and risk informed decision making. Calkin developed and leads the Wildfire Risk Management Science team within the US Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station.

Matt Thompson, PhD, is the director of applied fire science at Pyrologix, a subsidiary of Vibrant Planet. Prior to joining Pyrologix, Thompson spent 14 years in the Human Dimensions Program at the USDA Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station, Wildfire Risk Management Science Team.

Stephen Fillmore works for the USFS Region 5 Regional Office, where he serves as the regional fuels operations specialist. His portfolio focuses on working with National Forests and their partners to increase the amount and quality of wildfire fuels mitigation work accomplished within California and the Pacific Islands. Fillmore also actively works in wildfire management as a complex incident commander, operations section chief, and Type 1 burn boss. He recently finished his PhD from the University of Idaho where his dissertation focused on wildfire decision making within the context of wildfires managed for an objective other than full suppression.

The Future of Aerial Firefighting: The Dash 8-400AT

Fast, fuel efficient and tactically flexible. A modern airtanker with a 10,000 litre / 2,642 US gallon capacity to drop water, retardant, or gel over diverse geography.

Setting the standard for Next Generation aircraft with OEM support to keep the firefighter flying for decades.

BY RICHARD MCCREA

The 7th IAWF Fire Behavior and Fuels Conference opened its first session on Monday, April 15, in Boise, Idaho, under the shadows of the snowcapped peaks of the Rocky Mountains. This conference was well attended by fire practitioners, researchers, managers, professors, and students. The Boise conference attendance included 385 folks from 10 countries, 26 states, and 23 exhibitors. Students comprised two per cent of the attendees with the rest of the group split between researchers and practitioners.

Kelly Martin, IAWF president, opened the session with a welcoming statement and gave recognition to the leadership role that IAWF provides that unites fire managers and Indigenous Peoples. Martin emphasized the importance of global communication, collaboration, support for local communities, science, and the need for more flexible and adaptive approaches. IAWF recognizes that the scale and impact of wildland fire is continuing to grow on a worldwide basis and that some current management approaches are not workable. The fire community needs to craft strategies to effectively manage fire in all ecosystems and promote the importance of prescribed and managed fire.

Dr. Lori Moore-Merrill, U.S. fire administrator, opened with the keynote presentation that was shown virtually in Canberra. Moore-Merrill discussed the roles of the U.S. Fire Administration (USFA), which is to support and strengthen fire and emergency services and stakeholders to prepare for, prevent, mitigate, and respond to hazards. One of the current initiatives of USFA is the launch of the prototype version of the new, interoperable fire information and analytics platform, known as the National Emergency Response Information System (NERIS) for U.S. fire and

emergency services. The goal of NERIS is to empower the local fire and emergency services community by equipping it with near real-time information and analytic tools that support data informed decision making for enhanced preparedness and response to emergency incidents of all types.

Prior to the opening remarks participants had the choice of two workshops; one on gathering user inputs for long-term fire weather outlooks and the second on communicating practices for more effective wildland fire management. A tour of the National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC) was also available.

The Tuesday, April 16, morning keynote presentation, streamed from Ireland, was by Dr. Mark Parrington, senior scientist in the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service and Dr. Joseph Wilkens, assistant professor, Department of Atmospheric Science, Howard University. Parrington discussed the Copernicus Climate Change Service, one of the six thematic services provided by the European Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasts. This centre integrates fire models into weather forecasts and monitors smoke emissions, pollution, vegetation responses to climate and provides earth observation products for wildland monitoring and forecasting. Wilkens’ presentation focused on research into wildland fire smoke and its impacts.

The concurrent sessions on April 16 focused on fire behavior and fuels, technology and approaches, operations and management and extreme fire behavior. The presentations that day were followed by a poster session in the evening.

Nick Nauslar, National Weather Service (NWS) meteorologist, did a presentation that focused on

current programs for fire environment and decision support, and future needs. There is a wealth of information available to support decision making, which includes National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) monthly and seasonal outlooks for temperature and precipitation, NWS weather forecasts, and Predictive Services 7-day Significant Fire Potential. The Risk Management Assistance Dashboard (RMA) is another decision support tool that offers a wealth of information that has a spatial tool to view custom maps that displays such products as snag hazards, suppression difficultly index, potential control lines, NOAA forecasts, fire danger information and incident status. Other tools available include the Wildland Fire Decisions Support System and The Interagency Fuels Treatment Decision Support System. Future needs and improvements should focus on doing a better job of gathering fire environment information. There is a need for additional personnel to support operational decision making including fire behavior analysts (FBANS) and long-term analysts (LTANS). How information and data is being used for decision making in a daily operational environment is not fully understood and improved guidance is needed.

The April 16 evening keynote address, streamed from Australia, was presented by Dr. Dean Yibarbuk, chair of Warddeken Land Management Ltd., followed by a panel discussion. The discussions focused on the importance of Indigenous traditional burning practices and their importance in Australia. Wildland fire management is necessary to enhance and protect natural and cultural resources and communities. There is a need to shift from asking “why” we are managing fire in our environment to “how” programs need to proceed in the future and a move towards cultural burning and Indigenous knowledge and burning practices.

The April 17 sessions involved three field tours and four workshops. Field tours were available to NIFC, the Idaho Firewise Garden, and The Peregrine Fund’s World Center for Birds of Prey. The workshops included:

• Development and availability of spatial burn severity data through the United States Geological Survey and U.S. Forest Service, Burn Severity Portal

• Decolonial Community-led Forest Fire Research Methodology

• The Interagency Ecosystem Lidar Monitoring Program

• Challenges and Opportunities for Wildland Fire Workforce Reforms’ Career resource and tools workshop/Career Fair

The April 18 morning keynote speaker was Dr. Mark Finney, research forester with the U.S. Forest Service, Missoula Fire Sciences Laboratory. This presentation was titled “Big Fuels for Big Fires: Experiments to understand burning behavior of forest fuel complexes.” Finney discussed current research on fire behavior as it relates to large woody fuels and their contribution to extreme fire behavior. The United States faces a century

long accumulation of woody fuels and duff in our forests from mortality and disease impacts. These fuel accumulations contribute to extreme fire behavior, spotting, pyrocumulus development, firestorms, and high severity impacts. High winds are not required for this type of firestorm development because of the intense indrafts, and large vortices created by column development. With these firestorms the flames can spread in multiple directions and 80 per cent of the fuel burns after the flaming front passes. With our current fire behavior models it is difficult to predict fire behavior in these situations. This research is focused on the study of burnout of “big” fuels under controlled environmental conditions of wind speed, temperature, and humidity. The burning experiments are conducted in a laboratory setting, and a large steel building was constructed for this purpose. During these experiments various arrangements of fuels are burned with close monitoring of fuel moistures, burnout times and weight reduction of woody fuels. Initial findings show that wind speed, fuel moistures, fuel arrangements/geometry and topography really matter. During experiments the large fuels burnout from the bottom up and wind speed has a big impact on consumption. The focus of the research is to build the ability to predict fire behavior transition from line spreading fire to area fire spread.

On April 18, the concurrent sessions focused on fire behavior and fuels, fuels mitigation in the WUI, fire behavior and technology, and weather and climate. Robyn Heffernan, NWS Meteorologist, did a presentation on NOAA improvements in the United States fire weather hazards program. NOAA programs include research, operational forecasting, incident meteorologists (IMET), and the storm prediction programs. Daily operations include forecasts for weather, smoke, air quality, extreme weather events, debris flows, and fire detections. Long-term climate conditions are forecasted for temperature and precipitation. There is an increasing need for IMETs on incidents, and additional support for prescribed fire operations and spot weather forecasts. NOAA is investing in improvements in climate and weather forecasts, smoke modeling and equipment for IMETs.