die fledermaus

The Vienna State Ballet is part of the Vienna State Opera and Vienna Volksoper

Ewa Bathelier, Blue

die fledermaus

Ballet by Roland Petit in two Acts

Choreography & Direction

Roland Petit

Music

Johann Strauss II with additional material by Johann Strauss I & Josef Strauss

Arranged & orchestrated

Douglas Gamley

Musical Direction

Luciano Di Martino

Stage Design

Jean-Michel Wilmotte

Costume Design

Luisa Spinatelli

Realisation Stage Design & Light

Jean-Michel Désiré

Staging Director

Luigi Bonino

Staging

Gillian Whittingham

Orchestra of the Vienna State Opera

about today’s performance

With the revival of Roland Petit’s light-hearted ballet Die Fledermaus, set to popular melodies mainly by Johann Strauss II (1825–1899), the Vienna State Ballet pays tribute to the composer’s 200th anniversary. Where else could be more fitting for the performance of this ballet than the city where the “waltz king” was born, and his operetta of that name received its world premiere in 1874 at the Theater an der Wien? Petit’s work, described as an “operette dansée”, has relatively little in common with Strauss’s original and is more an adaptation of the latter. First presented at the Vienna State Opera in 2009, Petit’s Die Fledermaus received its world premiere under the title La Chauve-souris with the Ballets de Marseille at the Opéra de Monte-Carlo on 2 June 1979 and has conquered ballet stages all over the world ever since.

Petit essentially reduced the plot of this uplifting ballet to three main characters: Bella, Johann and Ulrich. The work is similar to the operetta in that all the action

revolves around masks, mistaken identities and amorous adventures. The family idyll of the opening is an illusion. In Petit’s ballet it is the charming Bella who tries to open her husband Johann’s eyes through roleplay and assuming other identities – however Johann continues to seek out extramarital pleasure by transforming at night into a bat and flying away. Supported by her friend Ulrich, both loyal and conflicted in equal measure – and who always seems to be in the right place at the right time to pull the strings that will save a marriage that has lost its equilibrium – Bella eventually succeeds in bringing her husband to his senses and clipping his wings in the truest sense of the word, while also reassessing her own role as a woman and a wife.

The versatile “storyteller” Roland Petit has the ability to present real-life situations in artistic form and represent them in ways that the audience can relate to, where every movement, every gesture has a meaning, and the characters are intensely human.

His technique is based on classical ballet, but always with an additional contemporary touch and typically “French esprit” and it is also enhanced with elements from a variety of dance styles, with particular importance attached to acting. Die Fledermaus therefore offers pure classical dance, coupled with the can-can, csárdás, waltzes and nuanced mime.

There is no doubt that a key component of the ballet is the music of Johann Strauss II, which is so important to – not only – Vienna. Johann Strauss’s music, composed from the middle of the 19th century, first for the ballroom and soon after also for the concert halls and theatres, seems tailor-made for the ballet stage, consisting principally of waltzes in ¾-time and possessing all the essential ingredients of dance: momentum and passion, but also tenderness. The momentum of whirling spins is virtuosic and intoxicating but also conveys a great sense of freedom, as was demonstrated by the exponents of “free” dance such as Grete Wiesenthal at the beginning of the 20th century. Choreographers have repeatedly drawn on Strauss’s masterful compositions – and not only his waltzes – with those to do so at the Vienna State Opera including Heinrich Kröller, Toni Birkmeyer, Valeria Kratina, Erika Hanka, Gerlinde Dill and Grete Wiesenthal.

In the more recent past, this music has been explored by former directors of the Vienna State (Opera) Ballet, notably Renato Zanella in Alles Walzer (1997), Kadettenball (2003) and the evening-length Aschenbrödel (1999) – Johann Strauss II’s final, unfinished work and his only ballet – and Martin Schläpfer, with a somewhat ironic take on Strauss’s blissful waltzes in Marsch, Walzer, Polka (2021). On the international stage, it was the Fledermaus theme, among others, that inspired choreographers such as George Balanchine (The Bat, 1936), Ruth Page (Die Fledermaus, 1961) and Ronald Hynd (Rosalinda, 1978).

Meanwhile, for his Fledermaus, Roland Petit commissioned the Australian composer Douglas Gamley (1924–1998) to arrange and orchestrate a “greatest hits” of Johann Strauss II with additional material from Johann Strauss I and Josef Strauss. With the aid of his specific choreographic language, he was able to find an extremely musical, humorous and succinct interpretation.

Die Fledermaus promises a great celebration of dance, but by no means one confined to charming, sweet ballet moves in a waltzing whirl: instead, it will be laced with a good portion of irony and the wink of an eye.

synopsis

Act 1

Scene 1 Can a husband behave like a lover?

Bella is a well-off lady who lives in a plush apartment somewhere in Vienna, Budapest, or another city – it matters not, providing it is a capital city in the former AustroHungary. Does Johann, Bella’s husband, love his wife? That is the question. And then there is Ulrich, a friend of the family. What does he expect from Bella? There he is! He always arrives at just the right moment with presents for everyone. But why is he giving those scissors to Bella?

Scene 2 A man is a thing that flies away.

In Bella and Johann’s bedroom. Once the light is out, the truth bursts out before the astonished young woman’s very eyes: her husband turns into a bat and flies away.

Scene 3 What a deserted wife can expect from a devoted friend. Who can Bella confide in? Ulrich rushes to her. He promises that in the big trunk he has brought he has the only thing that can help in such a situation. He gives her his advice: “If you want to keep hold of a frivolous husband, be both always the same and always different. Don’t let your husband get away with metamorphosis”. There follows a lesson in laughter, charm, and trickery…

Scene 4 A man is a man.

It is night, and the air is filled with the noise of women. Johann, who has left his wings in the cloakroom, is having “a pleasant time”. But unbeknown to him, Bella, emboldened by the lessons from her charm teacher, is watching over him. Will he recognize her? She disappears, reappears, each time looking different, each time unrecognizable. Ulrich’s advice pays off. Johann, himself astonished, puts his bat wings back on and flies off in pursuit of the unknown woman.

Act 2

Scene 5 Where we learn how a woman can keep her husband from turning into a bat. At a masked ball, Bella makes a grand entrance, pursued by her husband, who has still not recognized her and who, ever more insistent, is trying to seduce her.

Ulrich dodges in and out of the guests so as not to miss anything as his amazing plan bears fruit. When Bella appears in a costume in the lead role of the night’s main entertainment, Johann, dressed as a bat and giving in to the irresistible attraction he feels for the unknown beauty, tries to grab her. The woman resists, some gentlemen intervene, and blows are exchanged. The arrival of the chief of police and his henchmen puts an end to the fuss. The waltz restarts, but without Johann, who is thrown in jail.

Scene 6 The life of a gigolo is no bed for roses!

There is Johann in the cell. There he is locked up. No more waltzing. Love is now something for other people. He no longer has a place among the singers of serenades; other voices than his own will be speaking of love under women’s balconies.

But suddenly the unknown woman he is obsessed with appears. She orders the police chief to free his prisoner.

Alone at last, everything is resolved. The husband behaves like a lover, the wife is a mistress, while Ulrich, who crafted this whole scheme, continues to observe them.

Just as the husband succumbs to the seduction of his wife, Ulrich holds out a bag to Bella, from which she takes the precious scissors. Without hesitation she cuts the bat’s wings, just as Delilah cut Samson’s locks…

Scene 7 Slippers as a measure of martial happiness.

Bella, having recovered from anxiety, doubt, champagne and madness, has become again the untroubled lady whom we saw when the curtain rose. The bat with the clipped wings has moulted into a submissive, rather sheepish husband, who receives a symbolic pair of slippers from his wife.

With order restored to the household, what is there left to do? We are in the land of the waltz. So, ladies, gentlemen, dance, and let the music take you away.

Olga Esina (Bella), Kirill Kourlaev (Johann)

Ensemble

Ensemble

the storyteller and his ballets

KLAUS GEITEL

From the very start, it was impossible not to be captivated by Roland Petit. If Houdini was the greatest artist of all time at escaping from the shackles of captivity, Petit might be his opposite: an artist who could shackle the attention of his audience immediately. And he retained it for an astonishing length of time with an oeuvre that extended over decades. Post-war ballet in Paris began with Roland Petit – and it was spectacular from the start. He made it a hit with everyone, with his sense of artistic purpose, his humour and his dramatic passion. He created an entirely modern and thoroughly attractive art of dance on an established, classically trained foundation.

Petit never flirted with so-called modern dance. He remained steadfastly faithful to the art of ballet. But he did infuse it with new ideas. Especially the joy of creativity, excitement and the audacity to create all manner of mayhem. The legacy that he inherited from Diaghilev’s world-famous Ballets Russes was one of close collaborations with exciting new talents in painting and music, artists he brought together in dance theatre pieces that appealed directly to the eyes and ears of the audience. There was a delight in watching Petit’s works. They were bursting with surprises. They gave the impression of being thoroughly confident, original and inventive and they took dance in directions that were unmistakably their own. Nevertheless, they were also firmly within the utterly French tradition of the Paris Opera. Roland Petit had entered its ballet school at the age

of nine. There was no better education for a dancer far and wide. He joined the opera company’s corps de ballet when he was sixteen, and, of course, over the years he would have been able to rise through the ranks in the traditional way with its constant exams to attain the status of a premier danseur and étoile. But all that was too boring for him. His willingness to conform, his humility in the face of the iron guard of tradition had always been underdeveloped – and would remain so. The young man was and would remain unyielding even into old age and decisively went his own way, alone. And its time had come. The end of the war and France’s collapse into victory had cleared away many inhibitions and unlocked the gateway to artistic success for a new generation. Petit immediately and emphatically pushed it wide open. In October 1945, at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées, he founded his first ballet company and named it after the theatre. None of its members was over the age of twenty.

The only ones who were older and more experienced were their advisers and supporters, the highly professional enthusiasts who surrounded them, who, of course, included Jean Cocteau, Diaghilev’s former colleague Boris Kochno and the stage designer Christian Bérard. With capable and expert eyes, they watched over the artistic careers of these young people, who quickly began to write ballet history in this new era. The sensationally talented Jean Babilée led the way. He danced the male lead in Cocteau’s and Petit’s Le Jeune homme et la mort, a role that would be reinterpreted much, much later by Nureyev and Baryshnikov. Sometimes the originals are and will always be the best. No one has ever equalled Babilée in the fury of his performance and the remorseless pleasure he took in his doom.

Of course, for all his choreographic ambitions, Roland Petit did not hang up his ballet shoes. He was an elegant and cultivated dancer with a strong sense of theatre and over the decades he would remain a brilliant performer in a very wide range of roles such as Don José (in his ballet of Carmen) and Professor Unrat (in his version of the Emil Jannings role in The Blue Angel). A celebratory anthology of his ballets would constitute an eternity of delight. Some would take a more independent and original shape, and some a form that was more traditional and suffering slightly repetitiveness. But they would always be unmistakably recognisable as the work of Roland Petit. In any event, the standard he set himself for his ballets was always sky high. The partner he chose for his Carmen was Renée Jeanmaire, subsequently known as Zizi Jeanmaire, who would also reveal a sublime singing voice in Petit’s Croqueuse de diamants. By then Petit had already left the Ballets des Champs-Eysées and created a new company which he called Les Ballets de Paris and, not without some justified pride, added his own name. For many years the company was based at Paris’s Théâtre Marigny, whose theatre programme was directed by Jean-Louis Barrault. A first-class address.

Petit remained faithful to the company for a long time, however, his close artistic association with Jeanmaire, which eventually led to their marriage, her overwhelming sensuality and striking flirtatiousness made him focus more attention on the music hall as a new area for theatrical exploration. Petit began to study the tradition of Parisian revue, a popular destination for tourists to the city, treating himself and his Zizi to quite a few “trucs en plumes”. However, his intellectualisation of show business would not

succeed “à la longue”. Petit was more skilled at surprising people than at conserving things. He returned to the opera as a choreographer.

Before he did so, however, he had already tried out a genre that was entirely new to him: the evening-length ballet, a form that seemed to have been practically abolished in Western Europe since the days of Diaghilev but was still strictly adhered to in the Soviet Union. The Parisian audience for dance drama was eager for variety. Its curiosity craved one novelty after another. By contrast, evening-length ballets demanded an interest in dance with steely powers of endurance: an audience with what you might call muscular eyes. Roland Petit set about training them.

To do this, he chose Cyrano de Bergerac, the extremely popular swashbuckling drama in verse. He adapted it into steps and led it – and himself, of course – to a fresh triumph. From the very start he had possessed the gift of creating ballets with attractive roles that dancers would fight to perform. The cast lists of Roland Petit’s ballets read like a who’s who of dance, starting with Janine Charrat and continuing with Irene Skorik and Leslie Caron before reaching Natalia Makarova. Roland Petit was and always remained totally committed to adventure. He conquered the Paris Opera once again with a dance version of Notre-Dame de Paris. It genuinely felt as if the daring spirit of Dumas had entered the dancers’ legs and inspired moves that could swish through the air, then rapidly descend again and again, magnificently and redemptively into love. This was just what the audience wanted at heart. It was encouraged to be amazed – and it was.

As his accomplices Petit always hired painters and musicians who were in fashion at the time – or were about to come into fashion – and with his sharp eye he picked out the most promising talents in very different respects: from Marie Laurencin to Max Ernst, from Antoni Clavé to David Hockney, from Bernard Buffet to Niki de Saint-Phalle, from Léonor Fini to Paul Wunderlich and Josef Svoboda. And, of course, the composers Petit chose were able to keep up with their colleagues from the visual arts.

Joseph Kosma, Henri Sauguet and Marius Constant, Jean Francaix, Darius Milhaud, Georges Auric, Henri Dutilleux, Marcel Landowski, Maurice Jarre, Francis Poulenc and Yannis Xenakis: the Parisian school of modern music supported Roland Petit’s works and helped them, if not always themselves, to triumph. When one shouts in the forest, the echoes that are heard are not always congenial ones. It is something one must accept. Yet Petit would always find new ways of satisfying the ambitions he had of himself. And thereby rewarding his audience.

In retrospect, looking back on his life’s work, assembled step by step, lastly as the head of the National Ballet in Marseille, in artistic terms it sometimes seems that Petit only ever copied choreographic successes. One can easily forget that it was he and no one else who had created those successes in the first place. It simply appears as if he always conjured them up out of thin air. On the contrary: they were the product of his own stubbornness. He forced them out of himself. He made them work and with them he wrote ballet history – the history of an entirely new, uniquely entertaining style. He possessed the character of a discoverer and inventor who was crystal clear and utterly French. He hated all forms of abstraction. His choreography always kept on the dramaturgical ball. Roland Petit was and remained quintessentially a storyteller: a choreographic novelist.

“Petit is a clear, effective dance storyteller partly because he doesn’t muddy the waters with complex characterization or relationships; instead, he distills narrative to its essentials, often blending realism and fantasy. (…) Petit effectively pushed postwar French ballet into a new era, leaving behind the princes and swan queens of the 19th century to create 20th century characters who seemed radically modern and fresh.”

a palette with many colours

LUIGI BONINO

IN CONVERSATION WITH IRIS FREY

You look back on a long and close collaboration with Roland Petit. In 1975, you joined his Ballets de Marseille, where he created many roles for you, including Ulrich in Die Fledermaus. Later, you became his assistant, staging his ballets around the world. Since his passing in 2011, you have been responsible for preserving and rehearsing his entire repertoire as Artistic Director. How would you describe your work with Petit, and what kind of person was he?

LB Roland Petit was very demanding, and he expected everyone to work as hard as he did. But it was always a great pleasure, and I learned so much from him, above all, discipline. He could be strict, but always for a reason: he wanted to bring out the very best among his dancers. He discovered facets in people they didn’t even know they had and inspired them to surpass themselves. That’s exactly what he did with me. I was never a particularly good turner, but when I worked with Petit, I could suddenly do five pirouettes, or more! It was the adrenaline, the excitement he generated. The moments he was creating were the most wonderful ones. I learned everything from him – even dancing and singing in Broadway musicals!

When Roland Petit created a new ballet, did he already have a fixed concept, or were the dancers able to contribute their own ideas to the roles?

LB It was amazing when he created something new! When he arrived at the studio, he said, “Put the music on, please”. Then, with no prior preparation, he simply began to choreograph the steps. Yet he knew exactly what was happening in the music, when there would be a pas de deux or a solo, what he wanted, and who was in front of him. He also always emphasised that he did not create the choreography alone, but together with the dancers.

Petit’s ballets are very diverse – sometimes humorous, sometimes dramatic, one-act pieces or full-length story ballets – and they combine a wide range of dance styles. In Die Fledermaus, for example, we see pure classical dance alongside can-can, csárdás, and of course, the waltz ...

LB Roland Petit was like a painter with a palette full of colors. He created completely different ballets such as Die Fledermaus, Notre-Dame de Paris, Ma Pavlova, Pink Floyd Ballet, Duke Ellington Ballet, Carmen and L’Arlésienne, and yet his style was always unmistakable. He was also a great storyteller. When you watch Die Fledermaus, for example, every movement, every gesture, every situation has a meaning. There is never a single step without purpose or just for the sake of showing technique. I always say that Roland Petit’s ballets are easy to understand even for people who have never seen a ballet before. In Die Fledermaus, there are so many humorous, everyday scenes – like the family of five children gathered around the big dining table. It was pure joy creating that scene with Zizi Jeanmaire dancing the role of Bella, we laughed so much!

What was it like to perform and work with Zizi Jeanmaire – Roland Petit’s wife, the legendary French ballet and revue dancer, actress and chanson singer, as well as the protagonist of so many of Petit’s ballets?

LB It was fantastic! In the 1960s, there was a major TV show every Saturday evening, and Zizi and Roland Petit often appeared on it. Back then, I didn’t know who they were, but I watched every episode and was fascinated by Zizi’s incredible charisma. Years later, when I joined the company in Marseille, she was there and I was completely overwhelmed! We immediately developed a wonderful relationship, danced together and talked a lot.

How do you teach today’s generation the distinctive style and humor of Die Fledermaus? There are so many theatrical moments, some almost reminiscent of slapsticks. How do you guide dancers to find the right balance, so it doesn’t become exaggerated or clownish?

LB It takes a lot of work. Nowadays, anyone can learn a ballet from a video, but it’s not the same. Teaching the steps is easy – that’s important, but it’s not everything. It’s about conveying the spirit of the choreographer, and that’s much more difficult. I often tell the dancers, “Don’t be shy – if it’s too much, I’ll tell you. But dare to express yourselves, to feel, to dance from the heart.” Because that’s what Roland Petit was about: real life, human and touching. Like Bella in Die Fledermaus, who tries everything to open her husband Johann’s eyes and win him back, because he goes out every night in search of other pleasures. She calls on her friend Ulrich for help and in the end, she cuts off Johann’s wings and puts his slippers on him. Brilliant!

What does it mean to you to restage Die Fledermaus in Vienna, the birthplace of the “Waltz King,” Johann Strauss II?

LB It’s absolutely wonderful – especially now, on the 200th anniversary of Strauss’s birth! It’s something truly special, and I think it’s a fantastic idea by Ballet Director Alessandra Ferri to bring Die Fledermaus back to this place in such a significant year. For me, it’s a joy to restage the ballet here again and to see how the dancers evolve and open up. We have several excellent and very different casts, so it’s definitely worth seeing the production more than once.

Luigi Bonino with Davide Dato during a rehearsal

about the music

For the compilation of the music for Roland Petit’s Die Fledermaus, Douglas Gamley primarily drew upon compositions by Johann Strauss II, with additional material by Johann Strauss I and Josef Strauss.

Among the works heard are selections from Johann Strauss II’s operetta Die Fledermaus, including the overture and the Polka Mazur Glücklich ist, wer vergisst, mainly associated with the character of Bella. Roland Petit choreographed a lively number for three waiters to the quick polkas Leichtes Blut and Unter Donner und Blitz, as well as a virtuosic solo for Johann. To the march Es war so wunderschön Ulrich performs a humorous scene in the nightclub to which he brings the disguised Bella.

Furthermore, the waltzes Wo die Zitronen blühen, Neu Wien, Künstlerleben and Wiener Bonbons, which culminate in large ensemble scenes, the Polka française Etwas Kleines and the Polka Mazur Waldine, which turns into an amusing number ending in a dance duel between Ulrich and the Csárdás soloist, as well as the overture to Eine Nacht in Venedig also appear.

In addition, the waltzes Dorfschwalben aus Österreich and Sphärenklänge by Josef Strauss are featured – the latter in an intimate pas de deux for Bella and Johann in the “Prison Scene” of Act II – along with the Pizzicato-Polka by Johann and Josef Strauss, and material by Johann Strauss I.

“His melodic invention welled forth as delightfully as it was inexhaustible; his rhythms pulsed with lively variety; harmony and form stood pure and upright. ‘Love Songs’ he called one of his most beautiful sets of waltzes. All of them might have borne that title: little tales of the heart of shy courtship, rapturous affection, jubilant happiness, and, here and there, a breath of lightly comforted melancholy. Who could even name the most charming among Strauss’s many dance pieces! (…)

Strauss’s masterpiece Die Fledermaus owes its lasting and extraordinary success certainly above all to its enchanting music, but that music would be unthinkable without the thoroughly comic plot transposed to Viennese soil. The flood of Strauss’s melody flows here within a narrow bed, yet it fills it to the brim. Wherever, as in Die Fledermaus, wit and high spirits permeate the entire fabric and give rise to dance rhythms, Strauss offers what is most genuine and best in him.”

metamorphoses of a tale of metamorphosis

MARION LINHARDT

From a bourgeois comedy to a ballet

Within the – admittedly significantly longer – history of opera it is hard to find an individual work that occupies such as prominent position in the history of operetta as Johann Strauss’s Fledermaus. And no other operetta compares in occupying such a natural place in the repertoires of leading international opera houses. In his ballet La Chauve-souris, first premiered in 1979, Roland Petit tackles the classic operetta whose thoroughly dance-orientated music seems to cry out to be adapted for the ballet stage. However, the plotting and cast list of the ballet version are only vaguely reminiscent of its world famous source, first performed in 1874, which itself contains a series of more or less free variations on two highly successful precursors, namely Roderich Benedix’s comedy Das Gefängnis (“The Prison”), first performed in 1851 at the Schauspielhaus in Berlin and transferred that same year to the programme of the Hofburgtheater in Vienna,

and the comedy that Benedix’s work inspired, Le Re´veillon (“Christmas Supper”) by Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy, first performed in September 1872 at the Théâtre du Palais-Royal in Paris, which Maximilian Steiner then acquired for the Theater an der Wien and which was to be played here in a translation by the resident playwright Carl Haffner. The decision to adapt the French comedy into the libretto for a new Strauss operetta was not taken until a later date. With Das Gefängnis, Le Re´veillon, Die Fledermaus and La Chauve-souris, four related pieces exist which – each conforming to certain genre traditions and reflecting their own historical context – display more differences than common features. What they do have in common are: a recurring location – the prison; the motif of disguise; and, closely linked to these, the improvement or redemption of dissolute man to conform with bourgeois morality.

A successful comic author

In his autobiography he writes: “I have always been but a genre painter and will never allow comedy to be held hostage to the idiocies of the day.” With this recipe (Julius) Roderich Benedix (1811–1873) advanced within the tradition of August von Kotzebue to become one of the most successful German comic authors of the 19th century, whose plays could still be found in the repertoires of stages in German-speaking countries many years after his death. Benedix’s first theatrical engagement came with Bethmann’s company in 1831, and from 1838 he worked as a director at the theatre in Wesel, where his first play, the drama Das bemooste Haupt oder Der lange Israel was premiered with great success in 1841. A long series of dramatic works followed this, with which Benedix not only dominated German stages for decades, but also caused a sensation abroad. His comedy Das Gefängnis, for example, appeared as Vězenı´ in Prague in 1853 and as La Prison in a translation by C. Hombourg in Paris in 1856, and the play was even reprinted by the Reclam-Verlag as late as 1925 (in an adaptation by Ernst Albert). In Benedix’s Gefängnis, the history of the Fledermaus story begins as a moralistic play based on deception and mistaken identity from which – although the male lead warbles the “Champagne Aria” from Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Don Giovanni in Act One – one would hardly guess at the giddy, champagne-filled atmosphere of Die Fledermaus. Benedix’s comedy, it is clear, displays few similarities with Strauss’s operetta or Petit’s ballet: in Die Fledermaus (and also in Le Re´veillon) the motif is used of a (potential) lover who is arrested instead of the master of the house, and in La Chauve-souris the idea recurs that a dissolute man finds his “wings clipped” in prison. The marked differences between the comedy and the later variations on the same material characterise the former as a typical product of the German stage of the time. The men inclined towards libertinage here are not husbands but bachelors, and they are guided (back) onto the path of virtue by the love of dutiful women. Mathilde, the equivalent of Rosalinde in Die Fledermaus, is a shining example of virtuous womanhood and rejects advances of any kind with complete confidence. The plot focusses on the men and in the form of Baron Wallbeck, the “lover” Alfred – significant for the plot of Die Fledermaus but ultimately of minor importance – is the leading role.

The juxtaposition that is a core theme of every adaptation of the story from Le Re´veillon onwards of restrictive bourgeois mores with the ecstatic nature of a party and the colourful goings on of the demi-monde (a Christmas supper hosted by Prince Yermontoff in Le Re´veillon, a supper and ball at Prince Orlofsky’s house in Die Fledermaus, a late-night bar and masked ball in La Chauve-souris) is entirely lacking in Benedix.

The modern face of comedy

The two French stage authors who took Benedix’s play in the early 1870s and revitalised it with an entirely different spirit had made their names in the decade before mainly as librettists for the great operettas of Jacques Offenbach: La Belle He´lène, Barbebleue, La Vie parisienne, La Grande-Duchesse de Ge´rolstein, La Pe´richole and Les Brigands had all been written by Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy. The former was also the author of the comedy L’Attache d’ambassade, which became the basis for Franz Lehár’s operetta Die lustige Witwe. The path that the material Benedix had popularised took to become Le Re´veillon led, it is quite obvious, through La Vie parisienne by Meilhac/Halévy/Offenbach, the operetta based around disguises and reciprocal mistaken identities in the big city that received its world premiere in October 1866, also at the Théâtre du Palais-Royal, and was produced in Vienna at the Carltheater a mere three months later.

While Meilhac and Halévy adopted Benedix’s main dramatic idea, the arrest of the lover instead of the husband, for Le Re´veillon, they took the underlying mood of the piece from their own libretto for La Vie parisienne, which even provided the names for several characters in Le Réveillon: there is a Métella in the story of the Swedish Baron Gondremarck and his wife Christine, to whom two Parisian rakes show off both the high life and the demi-monde, enlisting servants and handymen to impersonate members of the nobility, and the censored libretto of La Vie parisienne indicates that the caretaker’s two daughters Clara and Leonie should be introduced as the Marquise de Valangoujar and Marquise de Villebouzin (pseudonyms which Gaillardin and Tourillon assume for Yermontoff’s supper and which had already appeared in Alfred de Musset’s comedy Il ne faut jurer de rien, first premiered in 1848).

The essential impulse for Le Reveillon – and ultimately for Strauss’s Fledermaus –was provided by the atmosphere of La Vie parisienne: the champagne-fuelled ecstasy of exuberant parties based on changing identity and stepping out of one’s everyday life is central in both cases. It was entirely in keeping with French operetta at the time for Meilhac and Halévy to decide to write Prince Yermontoff as a breeches role, a feature that was retained in the libretto for Die Fledermaus – in the original production of Strauss’s operetta Irma Nittinger played and sang the mezzo-soprano part of the young Prince Orlofsky.

Women to the fore!

There have been numerous rumours about the circumstances under which Carl Haffner’s translation of Le Re´veillon for the Theater an der Wien turned into the libretto for Die Fledermaus and the reasons why the spoken drama never reached performance in Vienna. Especially as Richard Genée, the experienced Kapellmeister and book author, who had been entrusted with the adaptation of Haffner’s translation, made statements about his and Haffner’s contributions to the libretto whose truth cannot be verified. Nevertheless, if one makes a direct comparison between Meilhac and Halévy’s comedy and Strauss’s operetta and then considers the situation of the ensemble that existed at the Theater an der Wien in 1873/74, the modifications that Genée made to the plot of Le Re´veillon appear to be unavoidable necessities. (It goes without saying that the musical genre generated a series of dramaturgical demands that will not be considered at this point.) The Theater an der Wien’s female star and principal audience attraction since 1865 was Marie Geistinger, who had also taken on the business of managing the theatre alongside Maximilian Steiner since 1869. Since her debut in the title role of La Belle Hélène, Geistinger had created the lead roles in numerous Offenbach operettas in Vienna, had been instrumental in the waltz king Johann Strauss’s conversion to the theatre and sung the leading roles in his first operettas: Fantasca in Indigo und die vierzig Räuber (1871) and Marie in Carneval in Rom (1873). Any libretto for a new Strauss operetta had to take into account Marie Geistinger’s prominence in multiple respects. However, this prominence did not match any of the female roles in Le Re´veillon; both the wife and maid as well as Yermontoff’s female guests are merely episodic roles. Simplifying broadly, one can state that Genée’s dramaturgical intervention in his source material were substantially aimed at strengthening the female roles and thereby aligning the play with the hierarchy within the Theater an der Wien’s ensemble. By involving Fanny, now Rosalinde, in Duparquet/Falke’s scheme, Genée devised a leading female role that provided the diva Geistinger with opportunities for a whole range of scenes and could show off both her singing and acting talents in both seductive and comic moments. Alongside the “principal female singer” Geistinger, the significantly younger Caroline CharlesHirsch offered a contrast in vocal range in the soubrette part of the chambermaid Adele. Caroline Charles-Hirsch had also appeared in Carneval in Rom, and the composer Strauss took a special interest in her. Almost fifty years after the world premiere of Die Fledermaus Charles-Hirsch recalled how Adele was created: “Johann Strauss was determined to have me as Adele. (...) Strauss knew that I had actually trained as a coloratura singer and wrote me my own aria scored for a coloratura singer. But he had to rehearse the aria with me in secret because Geistinger, who could never have enough arias in any piece, was not to know about it. In the premiere, my entrance was timed so that I sang the aria at a point where Geistinger was busy with a costume change in her dressing room. The first thing she knew of this little chess move was when she heard the storm of applause.” Like the part of the wife, the part of the maid now stretched over all three acts, which as a result were also connected far more convincingly than in Le Re´veillon. The trick that Dr. Falke plays on his friend Eisenstein is much more pointed

than Duparquet’s, as Eisenstein is not only – like Gaillardin – laughed at by all those at supper, he also has to justify his behaviour to his wife (who witnesses his extra-marital manoeuvres in person, disguised as a Hungarian countess) and is embarrassed in front of his chambermaid.

The metamorphosis of the woman becomes the subject

Assuming another identity, or at least a different name, role play, and the exchange of roles are, it has become clear, central dramaturgical elements in all the works that are derived from Roderich Benedix’s Das Gefängnis. While for Benedix himself and in Meilhac/Halévy it is exclusively men who take on the role of a different person for a certain period of time, for Strauss, role play by the women becomes one of the key drivers of events and for Petit to a certain extent the metamorphosis of the women becomes the subject of the piece. In Die Fledermaus it is Dr. Falke who includes the maid Adele and the wife Rosalinde in his plan to avenge himself on Eisenstein for his “bat trick” and, like a director, he allocates them specific roles: Adele is to appear at Prince Orlofsky’s ball elegantly dressed as a grande dame, while Rosalinde, wearing a mask, is introduced as a Hungarian countess. In this way they both become witnesses, indeed even objects, of Eisenstein’s erotic endeavours.

Petit bases his ballet, which makes do with three active figures, on a narrow section of the Strauss operetta, specifically the theme of the husband – Johann – who seeks his pleasure outside the marriage, and does not notice that he is observed doing so by his wife – Bella – indeed, he even chooses her, appearing in a variety of guises, as an object of desire. The ballet’s third central figure, Ulrich, combines the functions of both Alfred and Dr. Falke from Die Fledermaus, as Ulrich is both a “friend of the family” and the chief plotter at the same time. However, in this case his scheme is not intended as revenge for a prank, but to provide Bella and Johann’s marriage, which has lost its erotic equilibrium, with a new, more solid foundation. The prerequisite of this is that the wife should constantly take on a new form, or as Petit himself puts it: “If she wants to keep hold of a man with a lust for life, she needs to always be the same woman and yet someone else.”

the waltz on the ballet stage

GUNHILD OBERZAUCHER-SCHÜLLER

Dictionary definitions of the waltz tend to sound dry and simplistic: the twosome danced in ¾ -time is the oldest of the modern bourgeois social dances, having succeeded the minuet in the 18th century before the French Revolution, which had been the most popular dance until then. It reached its first peak of popularity around the time of the Congress of Vienna, when composers such as Joseph Lanner and Johann Strauss I had emerged and laid the foundations for its present popularity. Ultimately it was Johann Strauss II whose compositions would primarily confirm the waltz’s status as a significant –Viennese – musical form in its own right. Due to their high quality, they were soon taken out of the ballrooms and elevated to the concert platform, a position that they have continued to retain. Is the waltz then seen purely as a social dance and as music for concert programmes?

Not only in Vienna, but also in other “musical” cities – such as Paris, where the waltz has an effervescent character – the dance must also be seen differently. Here the waltz is spoken of as a physical expression of the feelings associated with all manner of circumstances: of bliss, of ecstasy but also of death. At home at all levels of society, the waltz is capable of manifesting itself in a wide range of social guises: it can be plain or rough, jaunty or sedate, smoothly elegant, glitzy or frivolous. As Viennese society (and Parisian too) has inherently theatrical features, the waltzes – regardless of where they are danced or by whom – are always covert or quite explicit theatrical statements. On top of this theatrically intensified level, the waltz also has an additional one: a stage

level where opera, operettas and ballets – and occasionally a “danced operetta” such as Roland Petit’s Fledermaus – not only uses ¾ -time but also treats the waltz as subject matter. Dance history shows that the stage waltz too can assume the broadest range of guises: from composers such as Johann Strauss II, and also taken from certain works, such as Die Fledermaus, it is at times sweet and gentle, determined and austere, revelling in drunkenness or demonically menacing. But the waltz also found other forms. It can be arranged grandly as Tchaikovsky does in works such as Swan Lake, Sleeping Beauty and The Nutcracker, where, in common with the ballets composed by Léo Delibes, whom the great Russian sought to imitate, the waltz has the capacity to depict the state of one of the characters or a situation in atmospheric sound images. Meanwhile the symphonic waltzes elevated into independent pieces at the beginning of the 20th century, such as La Valse by Ravel, are different again. In this work, which was originally to be entitled Vienna and whose later choreographic interpreters would include George Balanchine, a female protagonist enters the spell of a dark power that turns out to be none other than death.

From the ballroom to the stage

Who would be surprised that at a time – we are talking here about the second half of the 19th century – when the waltz was truly triumphant in Viennese ballrooms, efforts were made to transfer that great success to the ballet stage? The calculation was: why not put the bliss and ecstasy of this dance on the stage and be successful? The Vienna Court Opera, always keen to be topical, had already used numerous pretexts to smuggle the latest waltzes onto the ballet stage. Now, in 1885 (coincidentally the year that Grete Wiesenthal was born, who used the Viennese waltz to revive dance two decades later) the Vienna Court Opera produced a ballet with the succinct title Wiener Walzer (“Viennese Waltzes”). The work was choreographed by Louis Frappart (1832–1921), a journeyman who had belonged to the Court Opera ballet company since the middle of the century. The music was arranged by Josef Bayer, composer of The Fairy Doll. Although the ballet tells a slight story – how Vienna and the waltz developed through different periods – as so often during this period, the work can be seen as a “divertissement in costume” whose true theme is a reflection on the Court Opera ballet and the waltz itself. The ballet drew its particular sophistication from the degree to which it integrated the dance forms that were the waltz’s natural home: folk dance, ballroom dance and stage dance. This mix of different genres was also specified in the choice of musical pieces. Josef Bayer – working in a similar fashion to Douglas Gamley, who would arrange the music 100 years later for Roland Petit’s Fledermaus – conceived an orchestral arrangement for the three-part Wiener Walzer that matched the waltzes but also the image of Vienna of that time. Making no attempt at authenticity, the work traced, in the words of an accompanying text “… an evolution of the Viennese waltz and offers a generic picture of the Viennese and their life.” Among the pieces of music selected for the work, which is set in a Biedermeier entertainment establishment in Spittelberg, the “Apollosaal”, and in the Prater, alongside early, down-to-earth waltzes still derived from folk dances from the

end of the 18th century that came from the suburbs, there were compositions such as Die Schönbrunner by Josef Lanner, Aufforderung zum Tanz by Carl Maria von Weber, Brüder Lustig by Johann Strauss I, and Fledermaus-Walzer, Wiener Blut, An der schönen blauen Donau and In’s Centrum! by Johann Strauss II. It also included the popular Brüderlein fein by Joseph Drechsler, which is sung by the young people in Ferdinand Raimund’s Der Bauer als Millionär. The ballet came to a patriotic ending with Carl Millöcker’s Für’s Vaterland. Additional waltzes were heard in the preludes and interludes that gave the audience an opportunity to appreciate the course and development of the urban waltz.

The large orchestral cast matched the extensive personnel used by the Court Opera ballet. The ensemble, which then comprised some 100 members, was supplemented by 40 apprentice dancers. Just as they were different in genre and colour, the waltzes were also danced in a range of styles. A folk dance-like waltz would be danced by character dancers, a social waltz by semi-character dancers and a concert waltz by leading dancers, the prima ballerina, and on pointe. The plan worked: Wiener Walzer remained in the Vienna opera repertoire for 55 years, during which it received 601 performances!

To this day Viennese choreographers and ballet masters are regarded as specialists in choreographing waltzes. When Roland Petit set about producing his dance version of Fledermaus, he did not hesitate in having his ensemble instructed by just such an expert: Fred Marteny was born in Prague but grew up artistically in Vienna before going to pursue his career in France and was ballet master with the Ballets de Marseille in the Seventies. Famous for the Viennese dansante quality of his work, he trained Petit’s ensemble to waltz!

Graceful dancing and a rich world of emotion

While Wiener Walzer took the waltz from the social level of the ballroom and put it on stage at the Court Opera, stage composers had already approached the waltz in an entirely different way: Léo Delibes and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky were primarily concerned in an entirely new interaction between music and dance. Delibes had aimed to create this new relationship in his ballets when, in the words of musicologist Thomas Steiert, he “gave greater independence to musical form, albeit without altering the underlying structure of its fabric of mimic narrative and dance parts”. In this way he strengthened the ballet music as a whole as it no longer split into short numbers but allowed broader connections to be made between the music and the dramaturgy. One of the forms that he used was the waltz, and Delibes attached particular significance to it. For example, in Coppe´lia – a ballet that perhaps contained the first flashes of wit that would later be acclaimed as the “French esprit” and would come to characterise the work of Roland Petit – where waltzes play a central role in each of the work’s three acts, it is used as a means of characterisation for the leading couple. In Act One, Steiert suggests, the waltz expresses playful love and jealousy, in the Valse de la poupe´ e in Act Two, it lends the doll “magic and grace” and then provides a transition into the Festival of Bells in the final act, where the couple are reunited and married among noisy celebrations.

This served as a model for Tchaikovsky, who had seen one of the Delibes ballets in Vienna: his great ballet waltzes are also atmospherically coloured by the underlying character of each work. In Act One of Swan Lake, for example, the society scenes of the daytime world are embedded in waltz forms arranged on a broad scale. Waltzes are also used to illustrate the multifaceted emotional world of the protagonists, an emotional world that, again in the form of a waltz and in keeping with the plot, sounds withdrawn and bitter in Act Three. Tchaikovsky works in similar fashion in Sleeping Beauty and The Nutcracker. In Sleeping Beauty, the waltz serves a double dramatic function. At the beginning of Act One it unites the two worlds that are portrayed in the Prologue –those of the court and the fairies – with the jolly and more bourgeois world of Act One with its party for the adolescent female lead. The two great waltzes in The Nutcracker are also functional in nature, while additionally serving to connect the ballet’s opening narrative section with the divertissement section that follows. The Waltz of the Snowflakes presents the leading couple with a white dream world of glistening snow before they find themselves in a pastel-coloured world of sweets in the Waltz of the Flowers One evoking a magical mood, the other with “oriental” touches, in this final ballet by the great classical composer, the waltzes are again of central importance.

Revolution in ¾-time

January 2008 marked the centenary of the debut of the Viennese Grete Wiesenthal as a “free” dancer, an artist who seems rooted in space and time – in Vienna at the turn of the century – as few others are. Born out of the Secession and dreamily anchored in reality, even now Wiesenthal’s statements in waltz form feel like “Jung Wien” and the Secession manifested in the form of dance. Dissatisfied with the routine, tradition and stereotypes that she had to dance as a member of the Royal and Imperial Court Opera ballet company – including in works such as Wiener Walzer – she escaped from the prescriptive order of classical ballet and the House on the Ring and in the waltz she discovered the rhythmical form that could provide the basis for free interpretation. This was not what Wiesenthal regarded as the monotonous one-two-three of the social dancing scene, or the mincing on pointe of the ballet stage but a swinging borne along by a feeling of ecstasy, a free rocking back and forth and, by contrast, an equally inspired focus on oneself. The cry of “Vienna, Waltzes Wiesenthal!”, referring to Grete Wiesenthal and her sisters Elsa and Berta, made a new audience flock to venues such as the Wiener Werkstätte cabaret “Fledermaus”. But it would soon emerge that Wiesenthal’s dance was far more than a physical reaction to something that had already been articulated in literature (for the stage), painting and sculpture.

An art that was in transition between institutions, styles and periods was also caught between the spectacle of theatrical entertainment from the 19th century and avantgarde ambitions. A new self-confidence and approval accompanied Wiesenthal’s dancing, which had been able to lend the waltz and the music of the Strausses (including Fledermaus) an entirely new form, which was presented on new stages, bringing the character

of the suburbs into the city and thus into high culture. It also included motifs from variety dancing and ballet, both of which were exalted in a never-ending flow of movement.

As a result of the success of the incomparably new elements of Wiesenthal’s dancing, other art forms saw themselves vindicated in engaging with physical movement and continued – like Hugo von Hofmannsthal, for example – on a path already embarked upon, enriched by the knowledge that had already been gained through dialogue with Wiesenthal. These unique qualities of Wiesenthal’s dancing also aroused curiosity in other cities. Grete Wiesenthal did not hesitate for long before giving in to the temptation Hofmannsthal had presented in 1908: “Berlin is waiting for you!” After Berlin, the world followed.

The demonic power of perpetual spinning

Is there any other dance so deeply connected with death as the waltz? And does this mean that Vienna, a city generally considered the home of the waltz, has an especially close connection with death? Death, the waltz and Vienna, conjured up at times in “earthy”, at times in sentimental songs: these “three kinds of human existence” even cast their spell over foreign composers. Maurice Ravel, for example.

Originally Ravel, who, as his work demonstrates, had a particular affinity with stage dance, had the idea of writing a glorification of the Viennese waltz in 1906: a plan that he initially discarded and then returned to 1919. At that time Sergei Diaghilev, the legendary impresario of the Ballets Russes, had asked Ravel to write something about “Vienna and its waltzes”. At the end of 1919, when he had already begun the orchestration, the composer wrote that “I am waltzing like man possessed”. However, the work, which Ravel himself described as the “apotheosis of the Viennese waltz” did not find favour as, according to Diaghilev, it was not suitable for a story. (In this phase of the Ballets Russes’ existence, as Les Biches proves, Diaghilev was so taken with French frivolities one might think that he would have welcomed a Fledermaus story to Ravel’s music!)

After a large number of choreographers had studied the work, George Balanchine was probably the first to find the effective stage version for this waltzing whirl, for the New York City Ballet in 1951. Ravel himself outlines the atmosphere and beginning of his ballet: “Swirling clouds offer occasional glimpses of faintly discernible silhouettes of couples dancing a waltz. Gradually the fog dissipates. A giant ballroom, filled with a crowd constantly spinning in circles, becomes visible.” The characters and story that the Russian American Balanchine devised from the music is as follows: A ball is in full swing when a mysterious beauty enters dressed in white. She makes a cool but eccentric impression. Ominous figures cross her path, then suddenly an elegantly dressed young man with a page enters, who hands the beauty a series of black gifts. The first is a black necklace. A mirror is produced to confirm her beauty but the girl in white looks away in horror when she sees that the mirror is broken. However, she can no longer free herself from the man in black. As if compelled to do so, she reaches for the black gifts: long, black gloves into which she plunges her white arms in broad sweeping gestures, a black cloak and then a black bouquet. The girl is now dressed as if for a special occasion. Then

the young man reaches towards her, they embrace, and the girl falls to the floor, dead. The crowd of waltzers lift her high above their heads and continue to spin her on and on. La Valse is now the only remaining testimony of the lifelong dialogue between Balanchine and Ravel, from which the phrase “we are all dancing on the edge of the volcano” was also taken: the waltzing whirl of the aura of death associated with Vienna continues to be able to cast its spell over new audiences.

Death must be a waltzing Viennese

Where will waltzing stop? At a laughing face? Or immeasurable suffering? Can a waltz be transposed to any location? Or will the waltz stop short at certain venues? Could a Viennese waltz be heard in a church? In those circumstances, would one have to confine oneself to listening or might one – in church – also react to the sounds physically? And what form might that take? Now, having seen the images of the lying out and farewell celebrations for the former Mayor of Vienna Helmut Zilk, we know that waltzing is indeed “possible”, even in church. The television broadcast revealed that there was a “choreography” for this last waltz for Zilk: the bearers of the coffin of the man to be immortalised strode down the central aisle of the Stephansdom. As they did so, all in step, they repeatedly caught the beat of the waltz that the orchestra was playing. And something incredible happened: the coffin started swinging to the rhythm of the dance. Although the immutable should not be forgotten here, it is also necessary to address life once again and the waltz’s brighter side: so let us return to Die Fledermaus and to Roland Petit, and to join him in calling out: “We are in the land of the waltz. So dance, ladies and gentlemen and let yourselves be carried away by the music!” Petit himself would repeatedly obey this command, especially in the ballet he created for the Paris Opera in 1994, Rythme de valses, in which he presented waltzes by Johann Strauss in arrangements by Arnold Schönberg, Anton Webern and Alban Berg.

Laura Nistor (Maid), Davide Dato (Ulrich), Olga Esina (Bella)

Timoor Afshar (Johann), Olga Esina (Bella)

Ketevan Papava (Bella), Eno Peci (Ulrich)

Masayu Kimoto (Johann)

Ioanna Avraam (Bella), Giorgio Fourés (Ulrich)

& Direction

Roland Petit was born in 1924 in Villemomble, near Paris. He entered the Paris Opera Ballet School in 1933 and became a member of the corps de ballet of the Ballet de l’Opéra de Paris in 1940. He presented his first choreographic works as early as 1942, and in 1943 he took his first leading role in Serge Lifar’s L’Amour sorcier. After leaving the Opera, he worked as a dancer and choreographer with Irène Lidova’s Soirées de la danse from 1944.

In 1945, he founded the Ballets des Champs-Elysées and created groundbreaking works for the company such as Les Forains, Le Rendezvous, and Le Jeune homme et la mort. In 1948 he founded the Ballets de Paris, for which he created Carmen, Les Demoiselles de la nuit and La Croqueuse de diamants, among others. In 1950, he made Ballabile for the Sadler’s Wells Ballet. Between 1951 and 1955, he choreographed for Hollywood films such as Hans Christian Andersen, The Glass Slipper, Daddy Long Legs, and Anything Goes. His long-term artistic partnership with his wife, the famous dancer Zizi Jeanmaire, was also significant. For her, he created numerous revues and shows.

In the 1960s to 1980s, he created works for renowned companies like the Ballet of the Paris Opera—such as Notre-Dame de Paris (1965)—the Teatro alla Scala, the Deutsche Oper Berlin, the Royal Ballet London and the Royal Danish Ballet. In 1972, Roland Petit took over the direction of the Ballets de Marseille and choreographed such important works as L’Arlésienne, La Chauve-souris, Coppélia and The Nutcracker there. In 1981, his company was named Ballet National de Marseille Roland Petit. For this ensemble, he created ballets such as Les Contes d’Hoffmann, Ma Pavlova, The Sleeping Beauty, Le Diable amoureux, Boléro, and Le Lac des cygnes et ses maléfices. In 1992, he founded the École nationale supérieure de danse de Marseille. In 1998, he stepped down from the direction of the Ballet National de Marseille and settled in Geneva, where he died in 2011.

Since then, leading companies around the world have performed ballets from his oeuvre of over 165 works, including the ballet Teatro Colón Buenos Aires, New National Theatre Tokyo as well as the San Francisco Ballet, Beijing National Ballet and Bavarian State Ballet.

Roland Petit’s career has been honoured with numerous awards, including the Chevalier and Officier de la Légion d’honneur and the Commandeur de l’ordre national du Mérite.

A complete work by Roland Petit was first performed at the Vienna State Opera in 2009 with the premiere of Die Fledermaus. This was followed by L’Arlésienne (2012) and at ballet galas Le Jeune homme et la mort as well as excerpts from Carmen, Notre-Dame de Paris and Proust ou les intermittences du cœur.

The Italian-German conductor Luciano Di Martino has been a regular guest conductor at the Hamburg State Opera since 2008. He has led numerous performances of Giuseppe Verdi’s operas La Traviata and Luisa Miller as well as many ballets by John Neumeier, including The Nutcracker, The Little Mermaid, The Glass Menagerie and Duse. In the spring of 2025, he conducted Neumeier’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream at the National Center for the Performing Arts in Beijing.

As an internationally sought-after guest conductor, he has collaborated with many prestigious orchestras, including the Israel Symphony Orchestra Rishon LeZion, the Kennedy Center Opera House Orchestra, the Orchestre National du Capitole de Toulouse, the Orchestra of Teatro La Fenice, the National Ballet of China Symphony Orchestra, the Bulgarian National Radio Symphony Orchestra, the Tampere Philharmonic Orchestra, Korean National Symphony Orchestra, the Thessaloniki State Symphony Orchestra, the Novosibirsk Philharmonic Orchestra, and the Hamburg Symphony Orchestra. As an opera conductor, Di Martino has led performances at the Staatstheater Nürnberg, the Mariinsky Theatre, the National Opera of Bucharest, the Thessaloniki Megaron Concert Hall, the New Israeli Opera, and the Festspielhaus Baden-Baden, among others.

At the Théâtre du Capitole in Toulouse, he recorded a complete audio version of the ballet Giselle and conducted the premiere of La Sylphide in collaboration with choreographer and expert on August Bournonville’s ballets, Dinna Bjørn.

His work also includes contemporary music, having performed works by Lera Auerbach, Philip Glass, Arvo Pärt, and others.

After his initial positions as general music director of the State Opera in Stara Zagora, Bulgaria, he was appointed permanent conductor of the Classic FM Radio Orchestra in Sofia. He is currently the conductor and artistic director of the State Opera Plovdiv in Bulgaria.

Luciano Di Martino studied conducting at the University of Music and Drama in Hamburg with Professor Klauspeter Seibel, as well as at the Accademia Chigiana in Siena among others with Ilya Musin.

In the 2025/26 season Luciano Di Martino takes over the musical direction for Elena Tchernichova’s Giselle and Roland Petit’s Die Fledermaus at the Vienna State Opera.

imprint

Die Fledermaus

Ballet by Roland Petit

Season 2025/26

PUBLISHER

Vienna State Opera GmbH, Opernring 2, 1010 Vienna

General Director: Dr. Bogdan Roščić

Financial Director: Dr. Petra Bohuslav

Director Vienna State Ballet: Alessandra Ferri

Managing Director Vienna State Ballet: Mag.a Simone Wohinz

Editorial Team: Nastasja Fischer MA, Mag.a Iris Frey

Design & Concept: Fons Hickmann M23, Berlin Layout & Type Setting: Miwa Meusburger

Producer: Print Alliance HAV Produktions GmbH, Bad Vöslau

PERFORMING RIGHTS

Music material: Musikverlag Josef Weinberger GmbH, Wien.

TEXT REFERENCES

About today’s performance from Iris Frey as well as the interview with Luigi Bonino are original contributions for this programme booklet. / The synopsis as well as the quote by Roland Petit (p. 25) are taken from the programme booklet Il Pipistrello. Teatro alla Scala. Stagione 2005-2006 / The texts from Klaus Geitel, Dr. Marion Linhardt and Dr. Gunhild Oberzaucher-Schüller as well as about the music are partly are partly revised original contributions from the programme booklet Die Fledermaus from season 2009/2010. / p. 13: quoted after Roslyn Sulcas: Roland Petit: A French Choreographer, Most Savored in France, in: The New York Times. New York 2021. / p 19: Eduard Hanslick quoted after Hanslick. Digitale Edition, https://hanslick.acdh.oeaw.ac.at

Reproduction only with the permission of the Vienna State Ballet/Dramaturgy.

PHOTO CREDITS

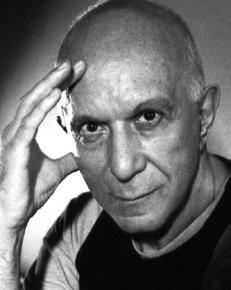

Cover: Ewa Bathelier, Blue, from the private collection of Kathryn and Stephen Mee, Sydney / pp. 6 & 7: © Axel Zeininger / pp. 8 & 9: © Michael Pöhn / pp. 17, 32 – 35: © Ashley Taylor / p. 38: z. V. g. / p. 39:

© Kiran West

Right Owners who could not be reached are requested to contact the editorial team for the purpose of subsequent legal reconciliation.

produced according to guideline Uz24 Austrian Ecolabel, Print Alliance HAV Produktions GmbH, UW No. 715

wiener-staatsballett.at