Crossroads of Identity:

Visual Representation of Intersectionality

Garlick, Mark. “Spiral Galaxy, Artwork.” Britannica ImageQuest, Encyclopædia Britannica, 26 Mar. 2018, quest.eb.com/sear ch/132_1521217/1/132_1521217/cite.

Garlick, Mark. “Spiral Galaxy, Artwork.” Britannica ImageQuest, Encyclopædia Britannica, 26 Mar. 2018, quest.eb.com/sear ch/132_1521217/1/132_1521217/cite.

Within Chadwick International, with the recent DEI Exchange and related school events, there has been increased discussion of identity, inclusion, and diversity on a school level. On a regional level, though originally a homogenous society, South Korea has been affected by globalization. As a result, it has become more diverse with people of various races, nationalities, ethnicities, sexualities, etc. There is a need to adjust and accommodate the increased diversity by raising awareness of the effects of one’s identity on their experiences and evoking discussion of diversity and inclusion. This magazine aims to accomplish this through stories of members of the Chadwick community. In the next pages, there will be interviews with various individuals — former students, current students, and teachers — with different identities. As an interviewer, I have tried to explore how each individual’s identity has affected their experiences within Chadwick and South Korea, and throughout their lives.

What is “Identity”?

Though generally, “identity” is seen as a definition of a person’s self, character, goals, and more, there are more specific definitions in social science contexts. The term “identity” carries two meanings: social and personal. First, it refers to a social category involving expected

behaviors and particular rules and characteristics. For example, when one refers to themself as a “Korean,” “American,” “daughter,” “teacher,” or “Asian” as an identity. Second, a personally defining and unchangeable feature that a person views as essential or fundamental to themself. This definition links identity to an individual’s dignity and self-respect as it involves one’s essential nature (such as desires, preferences, and beliefs) that one cannot change by desire. Throughout this magazine, both definitions will be used interchangeably as in modern times, social categories often intersect with one’s personal identity.

What is “Intersectionality”?

“Intersectionality” is a term that was created in 1989 by American critical legal race scholar Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw and has since been used as a theory, methodology, paradigm, lens, and framework. Though its specific definition may differ, intersectionality generally involves understanding an individual based on the interactions of their different social locations (including but not limited to race, ethnicity, gender, class, sexuality, geography, and disability). These interactions take place inside and among connected systems and structures of power such as law, policies, governments, religious institutions, and media. Through these interactions, privilege, and oppression are created, like a “matrix of domination” (Malcoe, Lorraine Halinka, et al.) In the context of an intersectional perspective, inequities are the result of intersections of different social locations, power relations, and experiences.

Nishinaga, Susumu. “Hover Fly Eye, SEM.” Britannica ImageQuest , Encyclopædia Britannica, 25 May 2016, quest.eb.com/sear ch/132_1319100/1/132_1319100/cite.

Milse, Thorsten. “Antelope Canyon, a Slot Canyon, Upper Canyon, Page, Utah, United States of America, North America.” Britannica ImageQuest, Encyclopædia Britannica, 25 May 2016, quest. eb.com/search/151_2589945/1/151_2589945/cite.

McIntyre, Will, and Deni McIntyre. “Busy Intersection.” Britannica ImageQuest , Encyclopædia Britannica, 31 Aug. 2017, quest.eb.com/sear ch/139_1859594/1/139_1859594/cite.

Nishinaga, Susumu. “Hover Fly Eye, SEM.” Britannica ImageQuest , Encyclopædia Britannica, 25 May 2016, quest.eb.com/sear ch/132_1319100/1/132_1319100/cite.

Milse, Thorsten. “Antelope Canyon, a Slot Canyon, Upper Canyon, Page, Utah, United States of America, North America.” Britannica ImageQuest, Encyclopædia Britannica, 25 May 2016, quest. eb.com/search/151_2589945/1/151_2589945/cite.

McIntyre, Will, and Deni McIntyre. “Busy Intersection.” Britannica ImageQuest , Encyclopædia Britannica, 31 Aug. 2017, quest.eb.com/sear ch/139_1859594/1/139_1859594/cite.

Navigating a new school and a new country is challenging — but what if you were surrounded by people who are either unaware or misinformed about you and your identity?

This was the case for Audi Ellis, a senior at Chadwick International, who is legally blind. After spending 14 years in the Illinois area, they moved to Korea in June of 2021. They were born with nystagmus, meaning that their eyes shake rapidly and involuntarily. Their vision has gotten progressively worse throughout their life. Luckily, they have maintained a positive view of their condition.

When I was in varsity track last year, I recall them talking about how South Korea and Chadwick are less accommodating of their disabilities than America. Their experiences were very eye-opening for me, an ablebodied person, at the time, so I thought it would be very insightful for this magazine. Audi enjoys reading articles and watching documentaries on serial killers and crime. They are interested in forensic science. They also enjoy dance, ballet, cello, acting, singing, and performing in general.

Patricia Jung: How would you compare your daily experiences in Korea and Chicago?

Audi Ellis: Overall, my daily life is very different.

First, in terms of safety, there is a lot of violence in most areas of the U.S. In Korea, it is unreal how safe it is. It feels like a video game or an alternative reality that I am able to walk alone at night. In America, it is very dangerous for me to walk at night as a blind person — my mobility cane

it is very dangerous for me to walk at night as a blind person — my mobility cane makes me a target.

In terms of culture and acceptance, most people in Korea are conservative and not very open. Personally, I am very open about my identities such as my sexuality and disability — but this comes as a shocker to Korean people.

I think there is a lack of knowledge in Korea. For example, people have asked me, “If you’re blind, why do you have eyes?” Since there is a lack of knowledge and awareness, it is very good to communicate and educate people in Korea. Generally, in the U.S., there is more knowledge on disabilities such as mobility canes. When people in Korea saw my mobility cane, they didn’t know what it was.

PJ: Similar to how people have asked you about your disability in public, how did your personal identity shape your experiences and how you perceive the world?

AE: Well, in terms of my gender identity, expression, and disability, I had to become more open about these aspects in Korea because I had to be.

It was a gradual process: in my freshman year, I did not think that I would become this open about who I am. But my perspective has changed since and I have become very passionate about activism. I really want people to know about me.

I have been in a position where I’ve been told that I should not do something because of my identity. So, despite any limitations, I think that it is really important to open up others’ viewpoints. Coming to Korea gave me

more opportunities to discuss my identity such as when I got to work with an 8th-grade class to design adaptive PHE games.

In general, I think that identity does affect how people view the World along with other factors. One factor would be the environment — where people are raised. Your surroundings could either change your view to be more similar to theirs or completely different. Also, the media plays a huge role. For example, the law against same-sex marriage in the U.S. resonated with me as I identify as gay. There are both positive and negative media but we tend to see negative more often because it is more attention-catching. For example, anti-trans healthcare and anti-LGBTQ media.

Many people focus on pessimism but this isn’t always a bad thing — it’s just how most people view the World. They are more likely to view something terrible than good. So,

in a way, we expect to see negative media and we are more comfortable with it.

Returning to identity, I think people who are more open about themselves tend to have a more open worldview and also be more willing to accept others.

PJ: Returning to the context of Chadwick International, when do you feel the most included in the Chadwick community?

AE: I feel most comfortable when people respect my pronouns and when people feel comfortable enough to ask me about my vision and identity. I think Chadwick struggles with inclusion due to a cultural divide. There is a certain language barrier and a culture barrier that separates students. And the forced social events such as House or assemblies don’t help as much. The forced social collaborations don’t work and students are still excluded

“If you were told you have 60 seconds left to live, what would be your biggest regret?”

Every individual has different aspects to their identity. Similarly, they experience unique intersections of identity that also vary based on the power system they are under.

I decided to interview Ms. MacDonald, my 9th-grade science teacher, as she seemed to have an interesting intersection of her gender, profession, and family background. As a woman in STEM, I thought Ms. MacDonald would have great insight into how different aspects of identity affects one’s experiences. In addition, I remember being part of her American Sign Language (ASL) club during middle school where she taught us the basics of sign language. She told us that one of her family members is deaf — and I thought this may provide a new perspective on my key theme of identity.

Patricia Jung: Thank you for agreeing to this interview. I’ll be starting off with a basic question about your background. How did you start teaching in Korea?

Julie MacDonald: Well, I had already taught internationally prior to teaching in Korea. I taught in China for 7 years. I was looking to teach in a higher-level school with an IB curriculum so I applied to a few different schools in Korea. I was then offered a teaching position in the middle school by Chadwick International. Because I loved the idea of Chadwick, especially its mission statement, I accepted.

PJ: While you lived abroad, how has your identity affected your experiences in different countries?

JM: Hmm… my primary adult

looking to teach in a higher-level school with an IB curriculum so I applied to a few different schools in Korea. I was then offered a teaching position in the middle school by Chadwick International. Because I loved the idea of Chadwick, especially its mission statement, I accepted.

PJ: While you lived abroad, how has your identity affected your experiences in different countries?

JM: Hmm… my primary adult experience has been international and I have not lived as an adult in Canada. I’ve lived in Japan, China, and Korea and my experiences have really depended on the country.

In Japan, I was really young and in my early twenties. I enjoyed society there — it was very rural-driven with lots of intricate details for social

rules which were very fascinating. Overall, the culture was very different from Canada’s. For example, you never tell something directly to someone.

Meanwhile, in China, I had a different eye-opening experience. It was a very frank, direct, and open society — which I had to get used to. The people were nice and friendly and the country had a very rich culture and history. Canada does not have a long history as a country so it was very fascinating to live in a place with a monoculture.

Again, Korea was also very different. There is often a misconception that China, Japan, and Korea are similar. But in truth, they each have distinct cultures and it was interesting for me to see the differences.

PJ: Moving on, as a science teacher and woman in academia, how did your identity as a woman affect you in your career?

JM: My experiences are interesting because generally, women do not make up a big part of science fields. However, in my program, we were all girls except for one male. Maybe this was because the program was an environmental science program.

When I moved into education — traditionally a woman’s role — there was a lot of diversity and my gender did not make a big impact. I also used to work as a research assistant at a lab where lots of head scientists were male. Everyone treated each other with respect and was more interested in an individual’s scientific mind rather than gender. So, I never had to experience any noticeable difference due to my identity. However, this is definitely not representative of everyone’s

experiences as I am a white female in science.

PJ: When do you feel the most included in the Chadwick community?

JM: I feel most included during my interactions with the science department here at CI. The middle school and upper school science teachers are very close with each other; we’re really good friends outside of school and all very diverse. Our common interests help us to interact. Also, among scientists, there are similar personalities and ways of thinking about the World which helps with bonding.

PJ: This is unrelated to the previous question but I remember participating in your sign language club back in middle school. I recall you mentioning that one of your family members was deaf. May I ask how having a deaf family member shaped your identity and how you view the world?

JM: Hmm… let me think. In so many ways. When it comes to communication, I learned very early on that communication exists in many different forms. There is so much you can say with facial expressions and body language. I also learned how to become more clear and more precise. I am very mindful of how I can show my engagement with whoever I am talking to through these different modes of communication.

Something I have taken from my mother to my daily life is her great perspective on perseverance and trying to look at the bright side of life. My mother is a very positive person and despite living with a significant disability, she has never let that stop her from doing things that she has wanted to. She

really taught me the importance of positivity and strength in challenges and adversity. I have let those values shape me — while being realistic.

If we can focus on the small things, then we’re happier and more balanced people. We can look past the negatives and look at challenges as opportunities to grow. My grandfather is also deaf, along with numerous other family members. So this gives you perspective.

PJ: Likewise, how did your personal experiences influence you as an educator?

JM: Well my family always liked to take things with a grain of humor and try to find a positive humorous way to deal with stuff. As an educator, when students are worried or struggling, the first thing I like to do is to make them feel better through humor. This makes them feel more confident and comfortable.

The most important thing for me as an educator is to make my students feel comfortable and be available as a support system inside and outside of science. Even if my students don’t learn anything, that’s alright as long as my students leave my class feeling safe and comfortable, and supported.

I think my life experiences have shown that anyone can learn as long as they have someone who cares about them, supports them, and wants them to be successful. And the more experiences I have, the more I believe in the importance of connections over facts and knowledge.

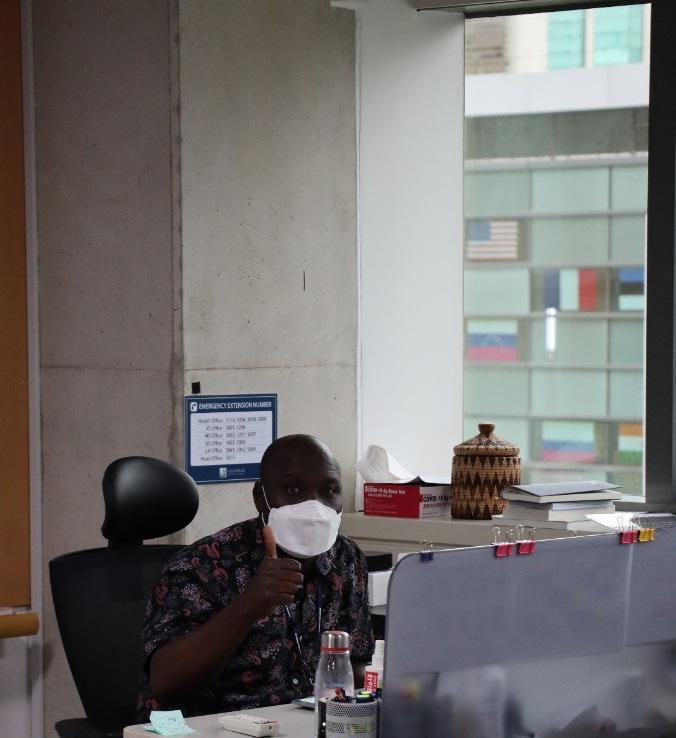

Depending on the individual, the situation or group in which they feel the greatest sense of belonging is different — even within Chadwick. This is true, especially for new members of the community, including Mr. Bukachi.

Mr. Bukachi is my I&S teacher from 9th grade. I thought he would have interesting stories to tell about his experiences as a teacher as he has taught in various countries and also studied international relations. He describes himself as a very outspoken, open, and easy-going person.

Patricia Jung: I will begin with a simple question about your background. How did you start teaching at Chadwick International?

Stanslous Bukachi: There were two parts to the story of how I began teaching in Korea. First, when I was completing my master’s degree in international relations, I was very interested in Korean War. Second, I had a close friend who came to work in Korea. Every time we met, I heard positive things about Korea. It was like a sign for me to come here. So, when I finally got the opportunity to work in Korea, I came.

PJ: During class last year, I recall you mentioning how you have lived in different countries. Did your identity affect your experiences? If so, in what ways?

SB: I have mostly lived in Kenya and Korea but I have also experienced other countries.

In Kenya, my character went well with

people that I associated with. Also, in Nigeria, the people there were very outspoken which matched very well with me. Meanwhile, in other countries such as Rwanda, the people were rather conservative because of what had happened to them in the past (the Rwanda genocide).

In the United Arab Emirates, apart from the community where I taught, it was very hard for me to integrate with others due to religion. The people there were very Muslim while I am a very active Christian.

PJ: Similarly, when did your identity make your life more challenging?

SB: During the short time I worked in UAE, there was a feeling that teachers from Africa weren’t as qualified as teachers from America or Europe. So, I felt the need to work

“I felt the need to work harder to prove myself... when something like this happens, it makes you not feel well.”

harder to prove myself.

There was no measurement of qualification but just because I came from Africa, I felt like this. I wasn’t the only one. It took some time for the students to appreciate us. When something like this happens, it makes you not feel well. But this didn’t last for long and I felt better.

PJ: Returning to the topic of our immediate community, how would you describe your experience in Korea and Chadwick International?

SB: I came to Korea during the pandemic so it was very difficult. I was received through separation at the airport because I came from Africa where the Korean government thought COVID was prevalent. Other people from the same plane but from different continents were allowed to proceed without the mandatory quarantine and additional COVID test. But even though I had arrived already with a negative test, I had to do it again. It was very challenging for me.

After I left the hotel, I proceeded for 14 more days in quarantine in my own house. It was in a completely new house and I had never lived in Korea before. It was definitely a very challenging experience. However, I did know about all these procedures before I came. Psychologically, I wasn’t hurt, but it was hard.

Meanwhile, in Chadwick, I was welcomed by a community of students and staff that was very friendly. Upon arrival, I immediately felt at home. My life revolves around Chadwick because that is where my life is. Most people I know in Korea are students and staff from CI.

One aspect that was unique about Chadwick was the discipline shown by students. I have worked in a

lot of schools but Chadwick has students who are so eager to learn and respectful. It feels amazing and motivating and makes me wake up every morning happy.

PJ: When do you feel the most included in the Chadwick community?

SB: I feel most included when I am teaching my students. Last year, I received very jovial students in my class. My advisory was amazing — this was where my life began. I felt very included.

When I first came to Chadwick, my advisees volunteered to help me in any way. They told me, “Technology, language, where to buy stuff,” if I had any questions, “we will help you.” My advisory became my backbone. I loved it. They completely changed my life.

“My advisory was amazing... My advisory became my backbone. I loved it. They completely changed my life.”

Most students at Chadwick International end up studying abroad: some leave for boarding school while some leave for university. However, as Chadwick International is mostly composed of students of Korean descent and upbringing, most Korean students do not become self-conscious of their racial and ethnic background.

I recently interviewed Jiyu Park, a Korean sophomore at Brooks School in North Andover, Massachusetts. Jiyu attended Chadwick International until the end of her freshman year and lived with her family in Seoul. As the cultural and social scene in America is very different from that in Korea, I thought her experience would

provide a different perspective on identity and inclusion compared to students who are currently attending Chadwick International.

Patricia Jung: Jiyu, you have experienced both Chadwick and Brooks recently. How would you compare your experience in Korea and North Andover?

Jiyu Park: Hmm… overall, I definitely felt like I belonged more in Korea as I was surrounded by other South Koreans. Also, in Chadwick, there were a lot of South Korean students and though I was friends with mostly foreigners, I still felt a strong sense of belonging. I felt completely safe with these friends. We were very close — like a family.

Meanwhile, in Brooks, I feel like I belong less because most people have different ethical and moral standards. Also, generally, most students have different personalities and priorities from South Korean people. Most people in America care less about academics and more about social life — which is unlike me or most Koreans.

PJ: Could you clarify what “ethical and moral standards” are referring to?

JP: Like, for things such as drinking, smoking, and using drugs. More students in Brooks engage in these activities and they are less stigmatized compared to Chadwick.

PJ: You mentioned how the students at Brooks are very different from you and the students at Chadwick. Has this affected your identity? If so, how has your perception of yourself and your identity changed?

JP: I definitely feel more like a foreigner in America. What can I say… I feel like an alien. Even though there are people who look like me, they are very different from me. For example, lots of Asian girls in Brooks are of American ethnicity while I am of Korean ethnicity.

PJ: Specifically, what were your greatest challenges related to your identity?

JP: I feel like people look at me with Asian stereotypes — like a pair of glasses. They think of me as a smart, hard-working Asian person who is very kind and doesn’t stand up for myself.

That’s what I think — people belittle you because you are Asian. They tend to act rougher and more careless towards you because they think, “Oh, Asians are more mannered… they’ll be okay with this.”

Also, as I mentioned earlier, I feel a cultural difference due to my background.

PJ: Moving on to the topic of inclusion, when do you feel most included in the Brooks community?

JP: When I am with the older girls in my dorm who are Chinese — Chinese Chinese, not Chinese American — I feel the most included. We have a lot of things in common such as our experiences as Asian people in Brooks. We care a lot about academics. They also help me with navigating life as an Asian person in Brooks since they experienced the same thing in the past.

Also, I feel most included when I am with my dorm parents. They treat all of their students the same — like their children.

PJ: Does Brooks have any particular initiative or policy for diversity and inclusion?

JP: Not really a policy but Brooks does have affinity groups for different religions, races, and ethnicities. There are also groups for international students. I think these student organizations would be the biggest part of diversity and inclusion at Brooks.

PJ: How would you compare the sense of community and school spirit at Chadwick and Brooks?

JP: In terms of school spirit, there is definitely more spirit at Brooks since people care more about their social life. As such, they have greater participation in parties, dances, and spirit weeks. Whereas in Chadwick, personally, I haven’t had a good experience in House or social activity — no one ever participated in or cared about these activities.

PJ: Based on your experience in Brooks, what recommendations would you make to improve the Chadwick community?

JP: Hmm… maybe there could be more social events in general. In Brooks, there are a lot of opportunities for students to get together and have a study break. Also, social activities (such as House and dances) need more effort because personally, I feel like the planners (students and teachers) of these events tend not to be very passionate as they know that most students will not participate.

One example of Brooks’s school

spirit is the head of the school’s open houses. Mr. Packard hosts open houses where there are snacks and food in his house and students can socialize with each other and other teachers. There are fewer gaps between students and teachers in Brooks, while there is a more clear line between students and most teachers in Chadwick.

I remember when Mr. Packard dressed as the Grinch on Halloween and ran around scaring people during our party.

However, I do remember some social events involving teachers in Chadwick. For example, when Ms. Oh was taped on the cafeteria wall. I think school spirit is a cooperative effort involving both students and teachers — everyone needs to participate.

Through these stories, we have seen how identity has affected people’s experiences within the Chadwick community. For Audi, it was their disability, gender expression, and sexuality that created their unique experience in South Korea and Chadwick. For Ms. MacDonald, it was her field of study and family background that led to her specific approach to teaching. Meanwhile, for Mr. Bukachi, it was his nationality, religion, and race that affected how he was treated in the UAE. Finally, for Jiyu, it was her ethnicity, nationality, and race that shaped how she feels in her new school.

How can we apply intersectionality in real life?

We can use the tenets of intersectionality to guide us:

1. People’s lives are multidimensional and complex. They are products of various factors and social dynamics.

2. We cannot determine the importance of any category or structure before analyzing social problems -- this is all discovered

during the process of investigation.

3. Relationships and power dynamics are all linked. They can also evolve over time and differ based on the geographic setting. For example, racism, classism, heterosexism, ableism, ageism, and sexism.

4. People can experience privilege and oppression simultaneously depending on the situation.

5. When investigating power relations, it is crucial to have multi-level analyses that connect individual experiences to broader structures and systems of power.

6. Scholars, researchers, etc must consider their own social position, role, and power when taking an intersectional approach. “Reflexivity,” acknowledgment of the importance of power at a microlevel (the self and relationships with others) and macro-level (society), should be considered before setting priorities and directions in research, policy work, and activism.

7. Intersectionality is directed towards transformation, building coalitions among diff groups, and striving for social justice

By applying intersectionality and its tenets in analysis regarding inclusion and diversity within the Chadwick community and in our daily lives, we will be able to address institutions of power and oppression and work towards equity.

Fearon, James. “What Is Identity (As We Now Use the Word)?” 3 Dec. 1999, pp. 1–37., web.stanford.edu/group/fearon-research/ cgi-bin/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/What-is-Identity-as-we-now-use-the-word-.pdf.

Hankivsky, Olivia. “INTERSECTIONALITY 101.” pp. 1–36. The Institute for Intersectionality Research & Policy, SFU, Apr. 2014.

“Libguides: DEI Resources: Gender & Intersectionality.” Gender & Intersectionality - DEI Resources - LibGuides at Michigan State University Libraries, Michigan State University , libguides.lib.msu.edu/c.php?g=1133877&p=8276225.

Malcoe, Lorraine Halinka, et al. “Intersectionality Research for Transgender Health Justice: A Theory-Driven Conceptual Framework for Structural Analysis of Transgender Health Inequities.” Transgender Health, vol. 4, no. 1, 29 Oct. 2019, pp. 287–296., doi:10.1089/ trgh.2019.0039.

Al-Faham, Hajer, et al. “Intersectionality: From Theory to Practice.” Annual Review of Law and Social Science, vol. 15, 13 Oct. 2019, pp. 247–265., doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-101518-042942.

Bešić, Edvina. “Intersectionality: A Pathway towards Inclusive Education?” PROSPECTS, vol. 49, no. 3-4, 2020, pp. 111–122., doi:10.1007/s11125-020-09461-6.

Carbado, Devon W., et al. “Intersectionality.” Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, vol. 10, no. 2, 2013, pp. 303–312., doi:10.1017/s1742058x13000349.

Kelly, Christine, et al. “‘Doing’ or ‘Using’ Intersectionality? Opportunities and Challenges in Incorporating Intersectionality into Knowledge Translation Theory and Practice.” International Journal for Equity in Health, vol. 20, no. 1, 21 Aug. 2021, doi:10.1186/ s12939-021-01509-z.

Krastel, Teresa. “5 Tips for Developing Intersectionality Practices and Awareness in Your Classroom.” Teach. Learn. Grow., NWEA, 19 Oct. 2022, www.nwea.org/blog/2021/5-tips-for-developing-intersectionality-practices-and-awareness-in-your-classroom/.

Moffitt, Kelly. “What Does Intersectionality Mean in 2021? Kimberlé Crenshaw’s Podcast Is a Must-Listen Way to Learn.” Columbia News, Columbia University, 22 Feb. 2021, news.columbia.edu/news/what-does-intersectionality-mean-2021-kimberle-crenshawspodcast-must-listen-way-learn.

Proctor, Sherrie L., et al. “Intersectionality and School Psychology: Implications for Practice.” National Association of School Psychologists (NASP), National Association of School Psychologists, 2017, www.nasponline.org/resources-and-publications/ resources-and-podcasts/diversity-and-social-justice/social-justice/intersectionality-and-school-psychology-implications-forpractice.