Spending Eternity with the EXECUTIVE BRANCH

White House Connections at Historic Congressional Cemetery

REBECCA BOGGS ROBERTS

about a mile and a half east of the capitol building, beyond busy commercial districts and neighborhood row houses, you can find a peaceful corner of Washington, D.C., where statesmen, citizens, heroes, and scoundrels share eternal rest. This is the historic Congressional Cemetery. George Watterston, the third librarian of Congress and a cemetery resident since his death in 1854, wrote in his guide to Washington, “The site of this graveyard has been most judiciously chosen. It commands a fine view of the surrounding country and the Anacostia, which flows at a short distance below it.”1 Even today, if you stand near the little chapel and gaze out toward the Anacostia River (you might have to hold up your left hand to block the view of the city jail that looms over the brick wall), you can

imagine it is the dawn of the nineteenth century and Washington is a brand new capital city.

Despite many elaborate maps and surveys, the original plans for the new capital from the 1790s did not include any burial grounds.2 When the federal government relocated from Philadelphia to Washington in 1800, this oversight became a problem almost immediately. A graveyard was built on the western end of the city, but it was the east side that was bustling with activity in those early years, as the twin economic engines of the Navy Yard and the new Capitol Building drove rapid growth. By 1807, a group of prominent citizens declared, “A great inconvenience has long been experienced by the citizens residing in the eastern portion of the city for want of a suitable place for a burying

Recent views of Congressional Cemetery capture a glimpse of the 35-acre site. The ornate entry gate stands at 1801 E Street SE, opening onto the final resting place of almost seventy thousand people.

opposite

The U.S. Capitol Building is seen in the distance at top left in this aerial view of Congressional Cemetery looking northwest over blocks of residential, commercial, and government buildings.

above

A northeast view of Congressional Cemetery captures the Anacostia River and the D.C. Central Detention Facility.

ground.”3 They purchased the central acres of what would become Congressional Cemetery and promised to turn the deed for the property over to Christ Church on Capitol Hill, the first Episcopal church in Washington where they were all members of the vestry, as soon as the graveyard was debt free. The founders originally called it Washington Parish Burial Ground.

It soon became evident that the U.S. Congress would need to make regular use of the new cemetery. At the time, with embalming uncommon and no speedy way to transport the deceased, almost everyone was buried where they died, even members of Congress who did not consider the capital home. The first was Connecticut Senator Uriah Tracy, who died just months after the cemetery

opened in 1807. But it was clear he would not be the last. Through the mid-1830s, almost every member of Congress who died in office was laid to rest in the Washington Parish Burial Ground, which inevitably became known as Congressional Cemetery.4

In 1815, Congress commissioned Benjamin Henry Latrobe, then the architect of the Capitol, to design a unique monument to mark the congressional graves. Latrobe was concerned that thin marble tablets, the most fashionable grave markers of the early nineteenth century, were “ingeniously contrived to last as short a time as possible.”5 To stand the test of time, Latrobe believed, monuments should be heavy, have a broad foundation, and be composed of as few blocks as possible. He designed a cube of Aquia sandstone, topped by

opposite

The distinctive Aquia sandstone cube-shaped and domed monuments were designed for members of Congress in Congressional Cemetery. Fifty-nine mark actual burials, while 112 are empty cenotaphs.

above

William Thornton, the first architect of the Capitol, is the only person honored with the specially designed monument who was not a member of Congress.

right

The Public Vault held the remains of President John Quincy Adams for eight days prior to his burial in Massachusetts. He is now remembered with a cenotaph in Congressional Cemetery.

a little classical dome, with a space for a marble insert engraved with the relevant details of the deceased. Even after it became more common in the middle of the century for members to be sent home for burial, a Latrobe monument was installed for every congressman who died in office. Today there are 171 of them in Congressional Cemetery, although only fifty-nine mark actual bodies. The rest are cenotaphs—a marker of an empty tomb.6

These distinctive monuments are found in no other cemeteries and nowhere else at all.

Despite its obvious association with the legislative branch of the federal government, Congressional Cemetery has a long history with the executive branch as well. In fact, one of those Latrobe cenotaphs bears the name of John Quincy Adams. When he was defeated for reelection as president in 1828, Adams went home to Massachusetts and then was elected to the House of Representatives. He represented Eastern Massachusetts in Congress until 1848, when he suffered a cerebral hemorrhage and collapsed on the House floor during a debate. He died two days later, and his body was placed in the Public Vault at Congressional Cemetery. He remained there for about a week, until arrangements could be made to have him interred in the Adams family plot in Quincy, Massachusetts. As a congressman who died in office, however, he earned a permanent marker at Congressional Cemetery.

The Public Vault, constructed with federal funds in 1835, was designed as a temporary resting place until a body could be moved to a more permanent site.7 Only the top third is visible from street level; the subterranean lower part is reached by a steep set of stairs below the heavy steel doors. John Quincy Adams was not the only president to spend time there. William Henry Harrison, the first president to die in office, only a month after his Inauguration in 1841, rested

in the vault for almost three months before being sent to Ohio for burial. Nine years later, President Zachary Taylor died after contracting a gastrointestinal ailment at the 1850 Fourth of July celebrations. His body stayed in the vault until late October, when it was sent to the family burial plot near Louisville, Kentucky.8

Despite its cave-like coolness, long-term storage in the Public Vault was a less than ideal solution in the days before routine embalming. Nonetheless, former First Lady Dolley Madison’s remains stayed in the vault for more than two years after her death, from July 1849 to February 1852. By the end of her life, Dolley Madison was practically penniless, having sold the Montpelier estate and her husband’s papers to cover the debts run up by her son, Payne Todd. The unrepentant Todd continued his profligate ways after her death, drinking and gambling away any money that was raised to bury his mother properly. Todd died of typhoid fever in January 1852 and is also buried in Congressional, under a small stone. Shortly thereafter, Dolley Madison’s body was moved out of the Public Vault and across the slate path to the Causten family vault, owned by the husband of her niece Anna. Six years later, arrangements were finally made to have the former first lady reinterred next to her husband James in the graveyard at Montpelier, despite the property no longer being owned by the Madison family.

Two vice presidents have been buried at Congressional Cemetery. George Clinton served as vice president in both Thomas Jefferson’s second administration and James Madison’s first. When he succumbed to a heart attack in 1812, he was the first vice president to die in office. An elaborate ceremonial procession was staged down Pennsylvania Avenue to Congressional Cemetery.9 Clinton was buried there under an ornate monument until 1908, when his body was removed to Kingston, New York. Elbridge Gerry was serving as James Madison’s second vice president when he suffered a fatal heart attack in 1814. He resides at Congressional Cemetery under a marble monument topped by a representation of an eternal flame and inscribed with an epitaph of his own words, “It is the duty of every citizen though he have but one day to live, to devote that day to the good of his country.”10 He is the only signer of the Declaration of Independence buried in the capital city. But perhaps Gerry is most famous for a cartoon published in 1812 when, as governor of Massachusetts, he signed a

redistricting bill with a district so oddly shaped that press declared it a mythical creature called a “gerrymander.”

Several presidential hopefuls reside at Congressional Cemetery, largely drawn from the population of congressmen. Southwest of the congressional cenotaphs, however, you’ll find the grave of Belva Ann Lockwood. A prominent lawyer, writer, and suffragist, Lockwood was the first woman to run for president, the nominee of the National Equal Rights Party in 1884 and 1888.11

As a woman, Lockwood could not cast a vote in those elections and had no expectation of winning. She just wanted to get her name on the ballot in as many states as possible, “and thus get up a grand agitation on the woman question.”12 She died in 1917, before the Nineteenth Amendment recognized women’s right to vote nationally. Like

below Vice president to James Madison, Elbridge Gerry is the only signer of the Declaration of Independence buried in Congressional Cemetery.

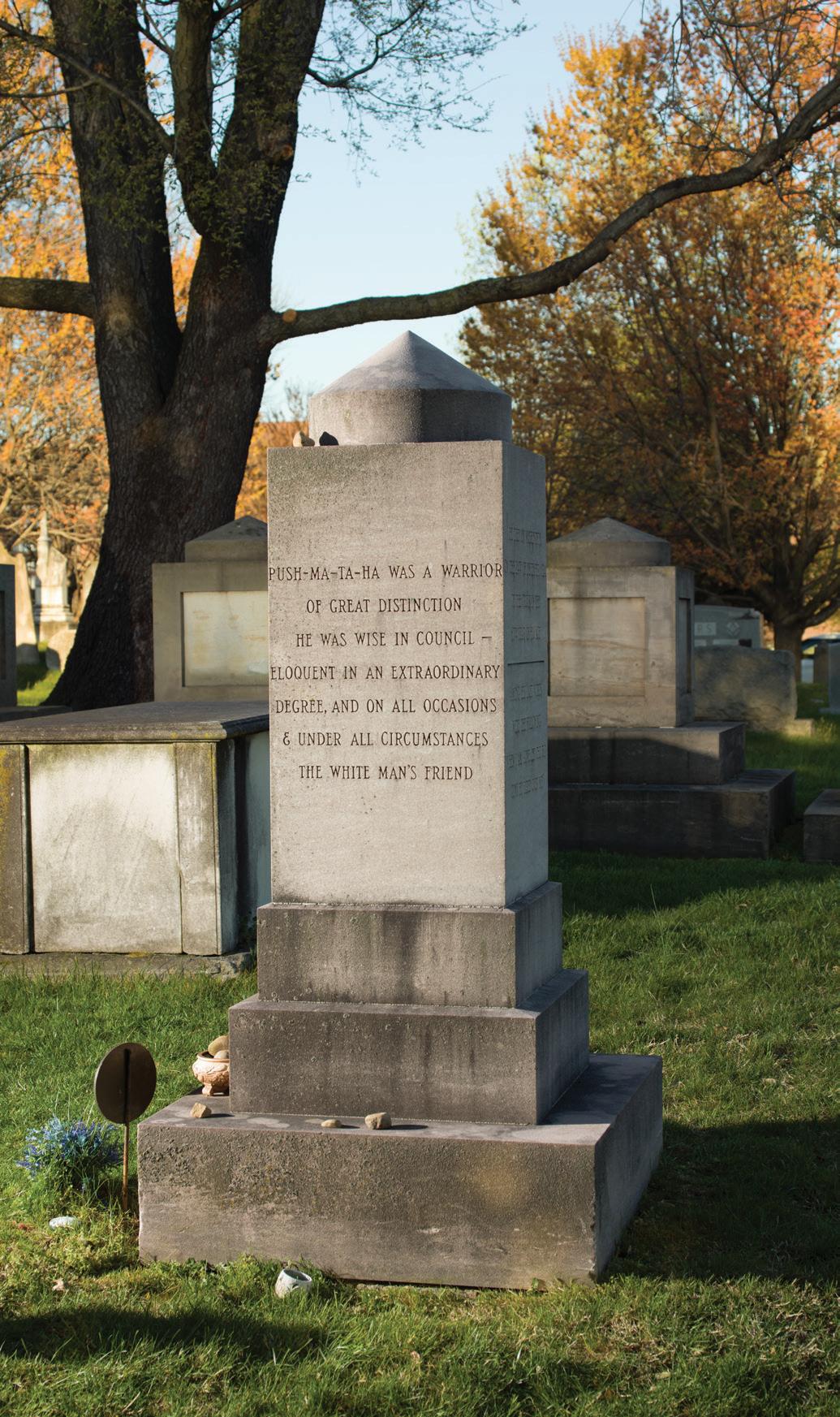

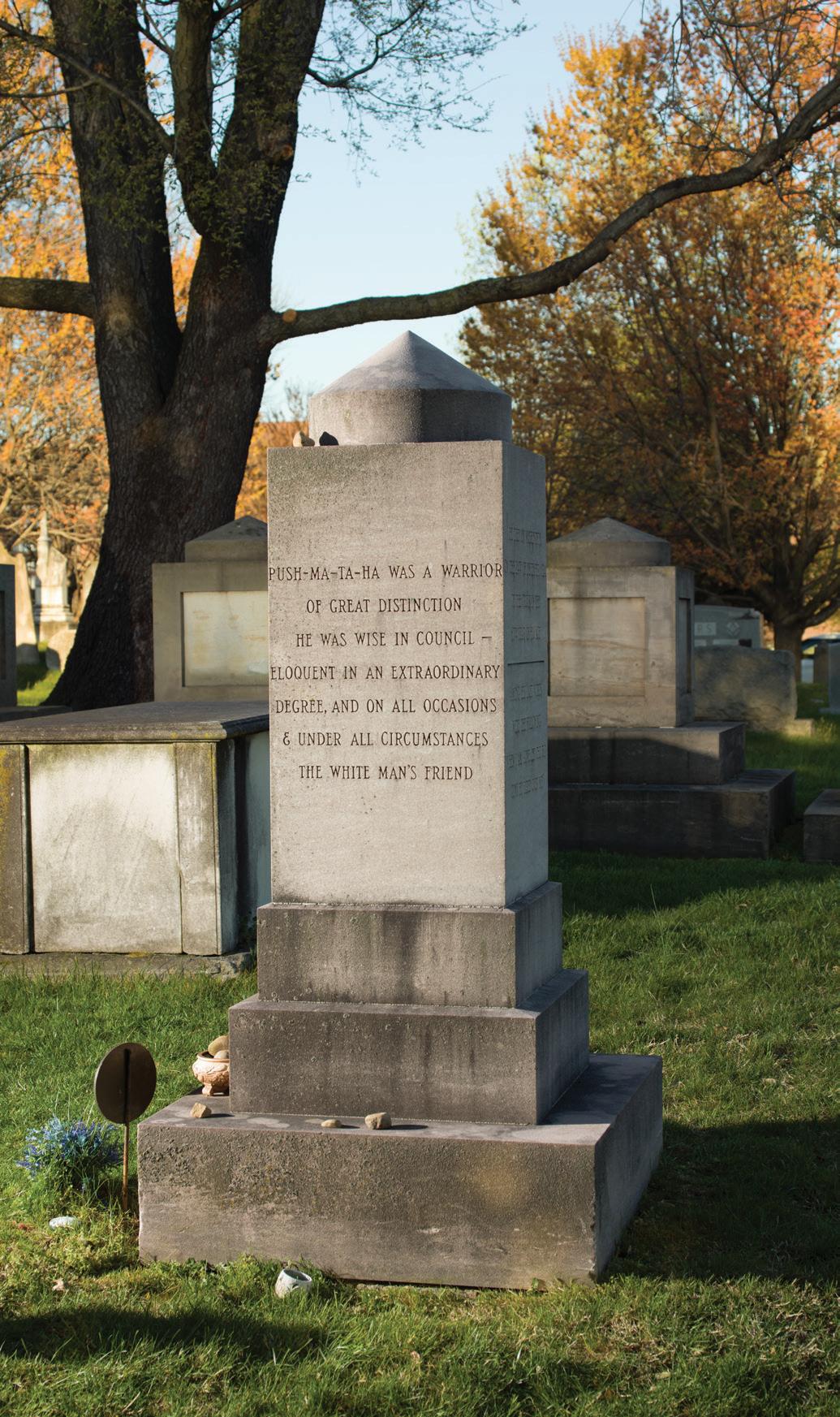

Among the notable burials at Congressional Cemetery are Belva Ann Lockwood (left), the first woman to run for president of the United States, and Push-mata-ha (right), a paramount chief of the Choctaw Nation.

Susan B. Anthony’s grave in Rochester, New York, voters often visit Lockwood’s grave on Election Day and leave their “I Voted” stickers on her headstone. Congressional Cemetery is also home to executives from other nations. In the northeast section stands the pink granite stone of Push-ma-ta-ha, the great Choctaw chief. Push-ma-ta-ha led the Choctaw in an alliance with the Americans in the War of 1812, and Andrew Jackson credited the Choctaw soldiers at the Battle of New Orleans with ensuring an American victory.13 After the war, Push-ma-ta-ha was elected paramount chief of the Choctaw Nation and negotiated land treaties with the United States. By 1824, frustrated by local authorities who refused to respect Indian land titles, Push-ma-ta-ha traveled to Washington to take his case directly to the federal government. There he caught a fatal fever. As he was dying, he

requested that he be buried with full military honors in Congressional Cemetery. He was buried on Christmas Day 1824, following a miles-long procession of thousands of mourners.14 His monument is reminiscent of the congressional cenotaphs, but made of a different stone and more elongated. The similarity is purposeful. It is meant to indicate that Push-ma-ta-ha was a leader and a statesman, respected on a federal level. The stone is inscribed on three sides. One reads:

PUSH-MA-TA-HA WAS A WARRIOR OF GREAT DISTINCTION

HE WAS WISE IN COUNCIL— ELOQUENT IN AN EXTRAORDINARY DEGREE, AND ON ALL OCCASIONS & UNDER ALL CIRCUMSTANCES

THE WHITE MAN’S FRIEND15

The tradition of installing a cenotaph for every

opposite and right

Congressional Cemetery remains an active cemetery today and plots remain available for new burials. In 2004 two totem poles representing Liberty and Freedom were installed to honor the victims of 9/11 (right). Made by Lummi Nation House of Tears carvers, the poles were originally placed at the Pentagon. Fees paid by K9 Corps members for dogwalking privileges provide an important source of revenue for the maintenance of the historic cemetery.

member of Congress who died in office ended in 1877, as fewer congressmen were electing to spend eternity in Washington, D.C. There was also some concern among the members that the stones were ugly: George Frisbie Hoar of Massachusetts insisted they added “new terrors to death.”16 Nonetheless, at the end of the nineteenth century, the cemetery was both a coveted final resting place and a popular spot for quiet contemplation in the ever-growing capital city. Like many urban graveyards, it suffered from neglect and vandalism in the middle of the twentieth century, and by 1997 qualified for the dubious honor of inclusion on the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s list of America’s Most Endangered Historic Spaces. Through a combination of community action, congressional support, and the dedicated efforts of staff and volunteers, Congressional Cemetery today is a thriving and beautiful place. It is still an active burial ground, with plots for sale among the historic graves.

notes

1. George Watterston, A New Guide to Washington (Washington, D.C.: Robert Farnham, 1842), 72.

2. Rebecca Boggs Roberts and Sandra K. Schmidt, Historic Congressional Cemetery (Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia, 2012), 7.

3. Quoted in U.S. Senate, History of the Congressional Cemetery (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1906), 5.

4. Roberts and Schmidt, Historic Congressional Cemetery, 7.

5. Benjamin Henry Latrobe, The Journals of Benjamin Henry Latrobe, 1799–1820: From Philadelphia to New Orleans, ed. Edward C. Carter II, John C. Van Horne, and Lee W. Formwalt (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989), 3:259.

6. Abby Arthur Johnson and Ronald Maberry Johnson, In the Shadow of the United States Capitol: Congressional Cemetery and the Memory of the Nation (Washington, D.C.: New Academia, 2012), 46.

7. Ibid., 139.

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid., 56.

10. Quoted in Roberts and Schmidt, Historic Congressional Cemetery, 46.

11. Victoria Woodhull ran for president as the candidate for the Equal Rights Party in 1872, but she was not yet 35, as mandated by the U.S. Constitution.

12. Quoted in Jill Norgren, Belva Lockwood: The Woman Who Would Be President (New York: New York University Press, 2007), 164.

13. Roberts and Schmidt, Historic Congressional Cemetery, 55.

14. Johnson and Johnson, In the Shadow of the Capitol, 163.

15. Quoted in ibid., 162.

16. Quoted in ibid., 227.