TEHRAN'S TEXTURES / OAXACAN SOUP / AKARA ABROAD

Layla

COPY

Layla

COPY

This edition feels vintage, careening from Asia to the Americas, the Balkans to Brazil, the arresting photography and intimate portraiture are what you all have come to expect from us over the last six years.

Have you ever noticed on the front of the magazine, the little idiom, ORIGIN FORAGING? It’s on the bottom center of the cover, and, at first (and maybe still?), people thought that was the theme of a particular edition of the magazine. But we put that stamp on each of our covers, as a way of saying who we are and what we do.

Origin is our framework for understanding the world, and also what connects these disparate geographies and communities. It’s about the gap between where we are and where we began, and the immense power of the stories that fill those universal voyages. The story of food is the story of humans, and neither can be told without the role of migration.

Uprooting by will or force is the crux of the universal, “Us.” Sometimes uprooting can be painful, other times, liberating, but without the knowledge of where you started, that gap is filled with the disorientation of false truths, or worse, a void.

The story of food is how we fill and how we feel. We hope you enjoy our latest collection of origin stories, foraged from around the globe.

With gratitude, Stephen

A herd of goats and their shepherd on the road between Kashan and Isfahan.

26 58 44

06 Decolonizing Korean Food | TEXT Giaae Kwon ILLUSTRATION Sinae Park

PHOTOGRAPHY Lyric Lewin 14 A Culinary Powder Keg | TEXT Irina Janakievska 26

Starting with Silog | TEXT Mark Corbyn PHOTOGRAPHY Martin San Diego 34 The Ceremonial Soup that Sustains a Culture | TEXT & PHOTOGRAPHY Fabricio González

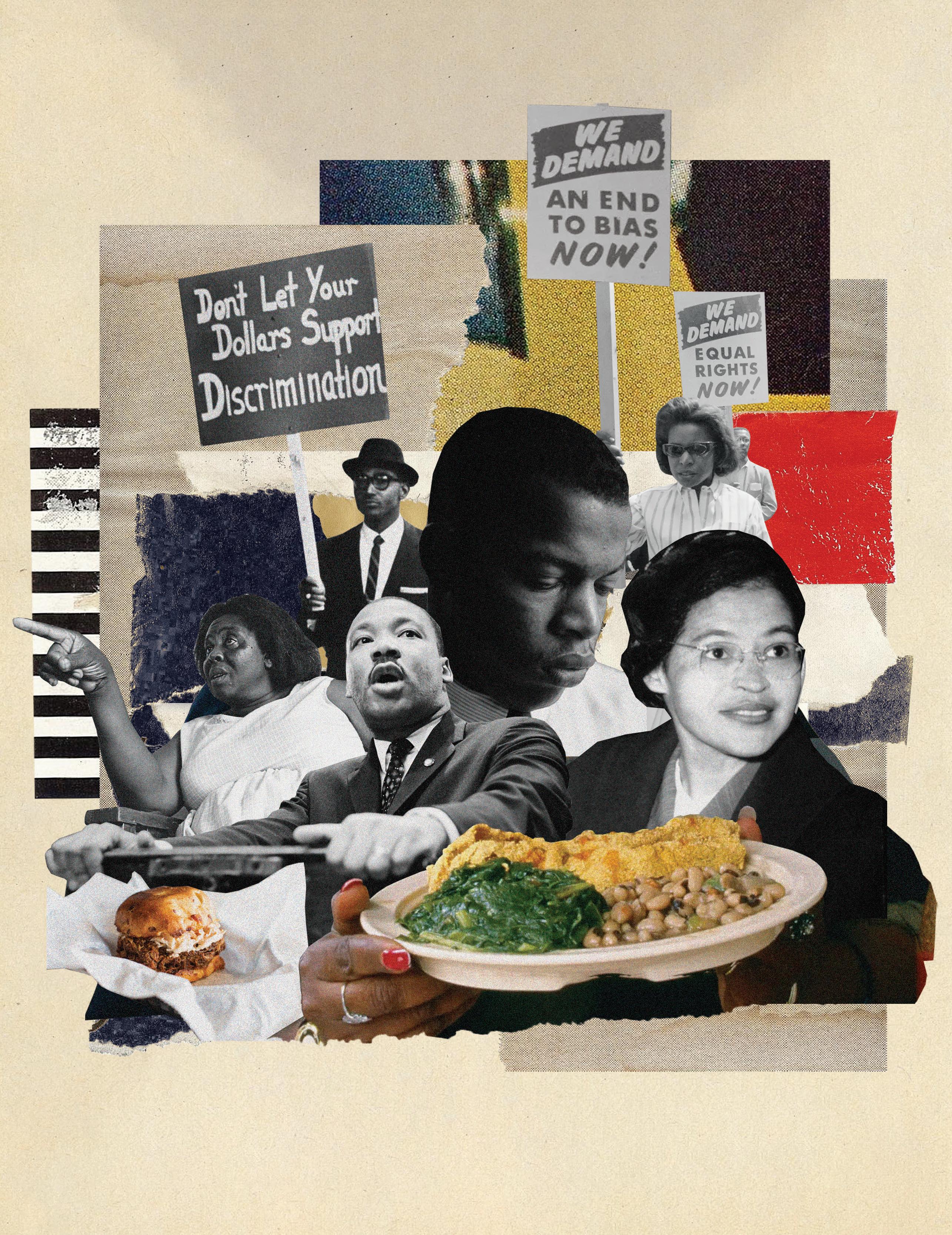

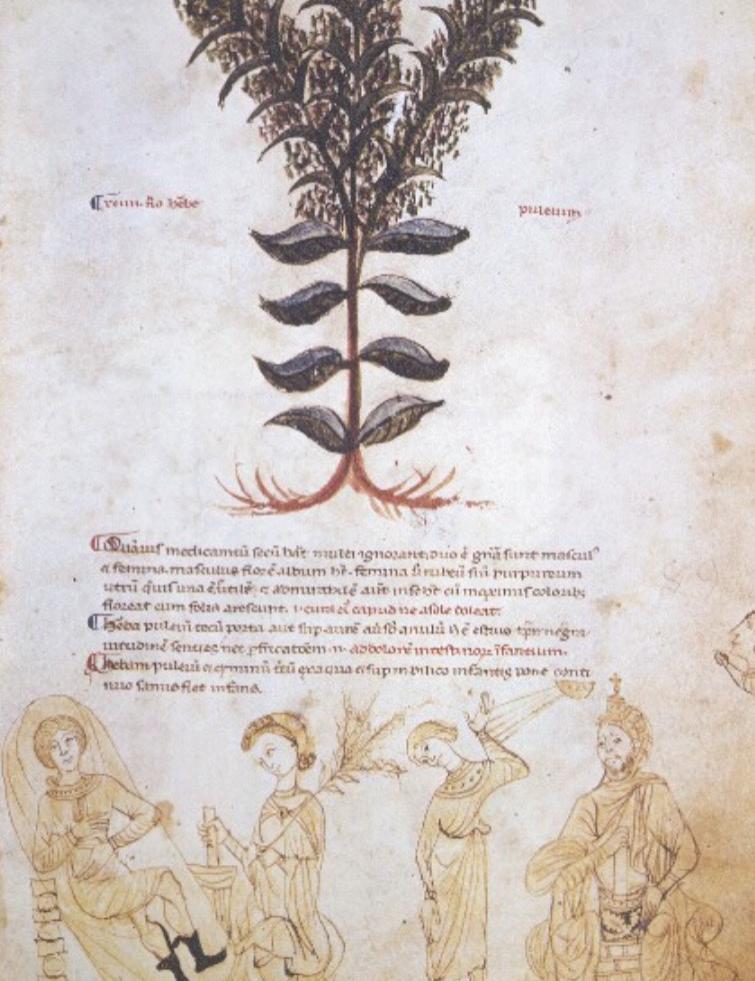

Soriano & Renée Alexander 44 A Feel for Tehran | PHOTOGRAPHY & TEXT Shabnam Ferdowsi 56 Lemon Street Market | POEM Ojo Taiye ART Dakarai Akil 58 Pennyroyal, Rue and ‘Hickry Pickory’ | TEXT Dr. Julia Fine & Dr. Ashley Buchanan 66 The Ticket to Freedom | TEXT Zahra Simpa PHOTOGRAPHY Rafaela Araújo 74 A History of Radicchio | TEXT Margarett Waterbury ILLUSTRATION Alexandra Bowman 80 Rendang for Eid | TEXT Annie Hariharan PHOTOGRAPHY Melati Citrawireja

Shabnam "Shab" Ferdowsi is a legally blind photographer born and raised in Los Angeles. Before Covid, she was primarily weaving her way around the music industry in the media and experiential space until she started performing on stage herself. Once everything went on hiatus, one thing led to another, and a pizza pop-up and catering business was born out of Shab's home kitchen. After a year roaming LA's parking lots, backyards, and bar patios, it was time for another shift. Nevertheless, food has now become the new centerpiece for building community, pursuing creativity, and telling impactful stories.

The food writer and recipe developer is a Macedonian, Kuwait-raised Londoner.

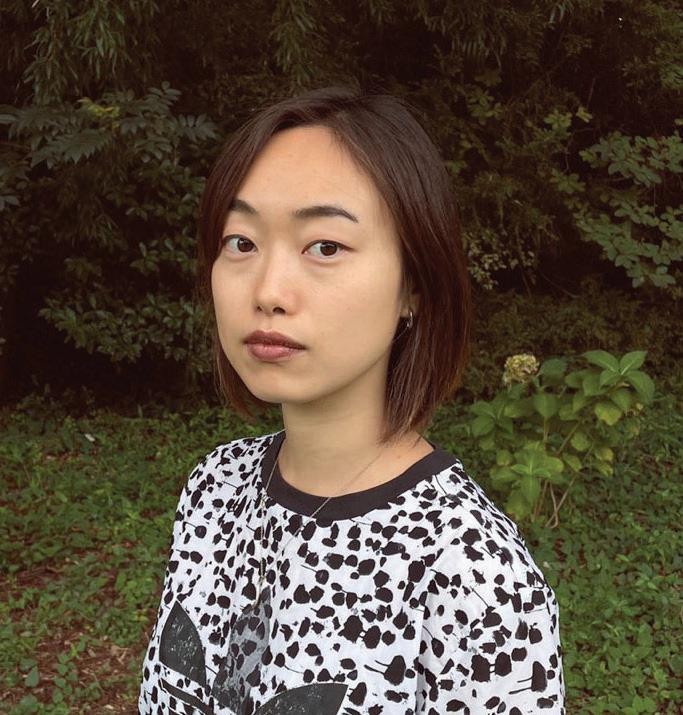

Giaae Kwon is a food and culture writer whose writing has appeared in Taste, Buzzfeed Reader, Catapult, and Electric Literature, amongst others. She writes the newsletter I Love You, Egg (iloveyouegg. com), and divides her time between New York City and Los Angeles.

When not spending time with his family (wife, daughter and mini dachshund), Mark occupies himself with cooking and writing about Filipino food as part of his work as a cofounder of The Adobros, a supper club and pop-up business based in London.

Sinae (she/her) is an independent illustrator and designer based in the UK and I use drawing as non-linguistic tool to propel conversation. When Sinae is not drawing, she designs and edits Fortified. You can find her swimming in a local pool or waiting for her third coffee of the day, worrying about getting too coffeed.

Martin San Diego is an independent documentary photographer from the Philippines. He is a multiple grantee of the National Geographic Society, a finalist of The Aftermath Project, an alumnus of the Angkor Photo Festival Workshops, a Diversify Photo member, a Visual Journalism graduate of the Ateneo de Manila University, and a fellow of the Konrad Adanauer Stiftung Media Programme Asia. Martin regularly contributes to The Washington Post and VICE News on notable Philippine issues— the Drug War, COVID-19 pandemic, and the environment.

Dr. Fabricio González is a professor of humanities at the University of Papaloapan in Oaxaca, Mexico. Driven by an adventurous palate, a deep appreciation of culinary traditions and a penchant for photography, he has focused the lens on the Chinantec region, exploring the relationship between territory, resources and food.

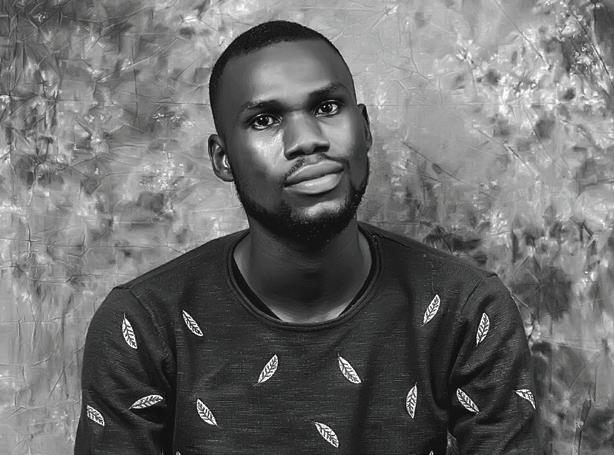

Ojo Taiye is a Nigerian eco-artist and writer who uses poetry as a handy tool to hide his frustration with society. Taiye’s most recent work is largely concerned with the effects of climate change, homelessness, migration, drought and famine, as well as a range of transversal issues ranging from racism, black identity and mental health. His current project explores neocolonialism, institutionalized violence and ecological trauma in the oil-rich, polluted Niger delta. His poems have been published or are forthcoming in Narrative Magazine, Salamander, Consequence Forum and Stinging Fly among others. Taiye worked on the Future(s) 2021 with Catalyst Arts and Belfast Photo Festival and 2021 Sustrans Black History Month Art Project.

Renée Alexander grew up in North Carolina and failed to master mountain biking in Bend, Oregon, before settling in San Francisco. When she isn't hosting a porkthemed dinner party or writing about food and booze, she is chasing solar eclipses and collecting travel bugs in remote locations around the globe. You can read her work online at StoryScout.net.

Julia Fine is a food writer and historian. Her work on food, imperialism, and the environment has been recognized by the Association of Food Journalists, the Association for the Study of Food and Society and the Oxford Food Symposium. She is currently a Plant Humanities Fellow at Dumbarton Oaks Museum in Washington, D.C.

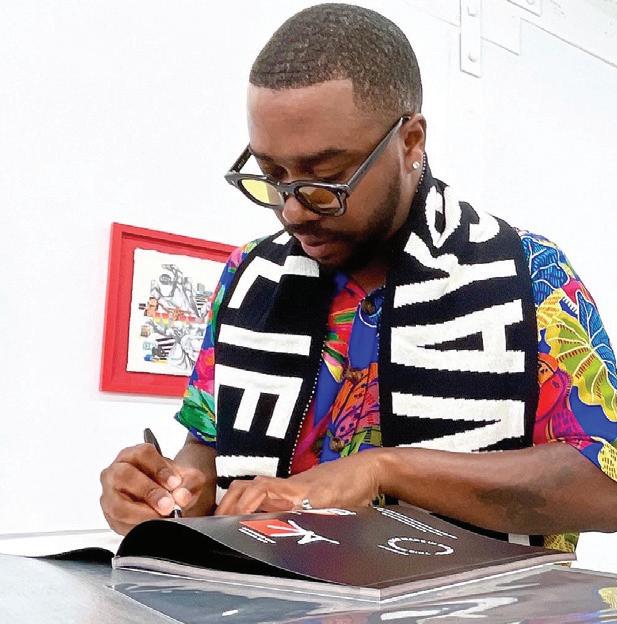

Dakarai is a Los Angeles based collage artist, designer, painter and editorial illustrator from Cleveland, OH. Primarily working in collage and design, he has selfpublished three art books that catalog works created between the span of 2014 to 2021. He has participated in numerous group and solo exhibits over the span of 10 years and has had work published in publications such as The New York Times, Wired Magazine, Readers Digest and several more.

Dr. Ashley Buchanan is a historian of the early modern world, with a particular interest in plants, recipes and medicinal cultures in early modern Europe. Her research spans many topics including the history of science and medicine as well as the dynamics of gender and authority. Her current book project investigates the social, cultural and political significance of pharmaceutical experimentation as well as the medicinal and botanical patronage at the court of the last Medici princess, Anna Maria Luisa de Medici (1667–1743).

Zahra is an ardent lover of words. When she's not writing, she's burying her face in a great story. She hopes to visit Cappadocia and ride a hot air balloon while relinquishing in the beauty of nature.

Margarett is an author, editor and freelance writer who lives in Portland, Oregon. She writes about drinks, food, plants, agriculture and how people interact with their environments. She is the author of Scotch: A Complete Introduction to Scotland’s Whiskies (Sterling, 2020), and contributes regularly to national trade and popular publications.

BACK COVER ARTIST

Rafaela Araújo is a Brazilian freelance photographer and journalist. Find her on Instagram at @raacph and on Twitter at @raacp

Melati Citrawireja is an IndonesianAmerican photographer and writer living on Ohlone land in Oakland, California. She enjoys growing Southeast Asian vegetables and practicing Indonesian family recipes for her food project Three Salted Fish.

Japan’s occupation caused deep and lasting wounds; calling dishes like gimbap ‘the Korean version of…’ rubs salt in them.

TEXT Giaae Kwon ILLUSTRATION Sinae Park PHOTOGRAPHY Lyric Lewin

Literally translated as “seaweed rice,” gimbap is a rice roll that is filled and rolled in a sheet of gim, or seaweed. It bears a physical resemblance to sushi rolls, so gimbap is often dismissively described as “Korean sushi,” which raises my hackles every time. A quintessential Korean food, gimbap is often strongly nostalgic, associated with school, road and family trips, but even this dish can’t escape being described as the Korean version of something Japanese.

Maybe, to a Westerner, the juxtaposition makes sense. On a superficial level, the two cuisines do appear similar—they both center around rice, with meals that often include some kind of soup. Korean and Japanese cuisines both use seaweed by drying it in sheets and wrapping those sheets around rice. In Korean, it’s called gim; in Japanese, nori. The latter is more commonly used, even in instances when a critic is reviewing a Korean American restaurant.

Japanese food has a stronger presence in the American zeitgeist. And to an outsider, maybe it seems fine— seaweed is seaweed.

But then there is this: In the late 19th century, Japan came into Korea and colonized it, formally annexing Korea from 1910 to 1945. Over the course of its decades occupying Korea, Japan tried to erase Korean-ness, illegalizing the Korean language, forcing Koreans to take Japanese names

and practice Shinto traditions, and exploiting Korean labor, agriculture and manufacturing.

Korean women were taken to be raped by Japanese soldiers on their campaigns in China, Manchuria and Southeast Asia. To this day, the Japanese government actively tries to erase that history as it waits for the remaining living comfort women in Korea and Southeast Asia to die out.

I’m a second-generation Korean American who was born and raised in the U.S. and grew up aware of this history because my grandparents lived through the Japanese occupation. Despite that, all this history really only connected with me emotionally when I spent 2019 eating gimbap at Momofuku Kāwi, the first Korean American restaurant whose food felt like home, resonating with the complex layers of my own identity.

Korea is a peninsula nation that juts off China into the East Sea. Termed the Hermit Kingdom, for centuries, Korea locked itself off from foreigners, interacting mostly with China and Japan, until Japan forced Korea to open up its ports to more trade partners at the end of the 19th century. This ultimately led to Japan’s colonization of Korea almost 100 years later.

Into the 20th century, Korean food was mostly made at home. Families would make their own jang, which are soybased seasonings that are considered the soul of Korean food and require months of care and fermentation— primarily ganjang (soy sauce), doenjang (soy bean paste), gochujang (chili paste). In late autumn, families and communities would come together for gimjang, the annual making of kimchi, a tradition that still continues today in some communities. Sool (alcohol) was also largely made from rice in small batches at home.

When Japan came into Korea, it brought massive change, from infrastructure to industrialization. As Japan considered Korea a geographically strategic stepping stone into the rest of Asia.

The Japanese occupation of Korea impacted food in many ways, but these two arguably may be the most significant: Japan industrialized food, and it brought the West into the Hermit Kingdom, from building European-style department stores to making bread a more accessible part of food culture. Additionally, as Korean agriculture and manufacturing were siphoned off to support Japan’s military, both directly and indirectly, Koreans’ access to

their food began to change. Korean rice was exported to Japan; canning factories were established to can fish and beer for Japan’s use; and soy sauce was industrialized and made in a Japanese style.

Meanwhile, Korea was being folded into Japan, its own culture and language erased—and that erasure is still continuing today, as Korean food continues to be referred to as the Korean version of Japanese foods. Like gimbap. Which brings me back to Momofuku Kāwi.

“I don’t want people to think about or mistake gimbap with sushi rolls,” Eunjo Park says. “I want to keep the traditional look of it and maybe just change the filling, so people are slowly getting an introduction to Korean food, but naturally.”

Park isn’t the first Korean American chef to reimagine Korean food in New York City; she’s part of a small but growing group of Korean American chefs who are challenging the notion of the “traditional.” She has her own approach to Korean food, tending to keep structures intact while changing their inner workings.

For example, her gimbap at Kāwi looked like gimbap and tasted like gimbap because she seasoned her rice the traditional Korean way—sesame oil, salt, sesame seeds— but she would fill her rolls with foie gras, custardy steamed eggs and raw bluefin tuna, instead of the usual eomook (pressed fish cake), bulgogi (soy-marinated beef) or tuna mayo.

Park, currently a private chef, was the executive chef at Kāwi when it opened in Hudson Yards in 2019. The Momofuku Group’s first dedicated Korean American restaurant, Kāwi served upscale, modern takes on Korean dishes, from gimbap to ddeok (made with rice imported from Korea and milled in Flushing, Queens, before being steamed and extruded in-house at Kāwi) to jjigae. Park studied at the Culinary Institute of America, then worked at French-inflected fine-dining restaurants like Daniel, Per Se and Le Bec Fin before joining Momofuku Ko.

“Working with Asian ingredients [like fish sauce] really opened my eyes as a cook,” she says. It was when she started developing ideas at Ko that she says, “I realized that my ideas weren’t coming from Daniel or Per Se. It was more like my home cooking, like nostalgia food.”

Park grew up eating Korean food at home but didn’t think much of it. In 2017, she left Ko to move to Seoul, where she worked at the three-Michelin-star Gaon and ate her way through Korea. In 2018, she came back to Momofuku

to helm the kitchen at Kāwi, which opened in March 2019 and closed because of Covid-19 in March 2020, just shy of its first anniversary. Momofuku announced its permanent closure in March 2021.

Kāwi’s closing, though, isn’t part of a trend, as American diners seem to be more curious to deepen their knowledge of Korean food, from banchan to grilled fish and even raw, marinated seafood.

For those new to the cuisine, unfamiliarity manifests in the constant juxtaposition of Korean food to Japanese food, the latter of which is more established among nonAsian diners, with the prevalence of dishes like sushi, tempura and katsu in the American zeitgeist. Regardless, even now, half a century after the Japanese occupation of Korea ended, the juxtaposition means Japanese-ness is still subsuming and erasing Korean-ness.

To be fair, in the West, the juxtaposition isn’t necessarily done with malice, simply a lack of knowledge.

“I think that, from a Western view, it’s less like equating Korea and Japan, but, also, they are two countries right next to each other,” says Irene Yoo, Korean American chef of Yooeating, and a writer and culinary historian.

“It’s like comparing New York and New Jersey. Of course, they’re super different, and New Yorkers would be like, ‘No, we’re not Jersey,’ and vice versa—but you’re also two states next to each other. There are going to be a lot of common shared things, both from a historical perspective and communication perspective.”

This tracks historically; Korea may have been closed off to much of the world, but it did interact with China and Japan even when it was the Hermit Kingdom. As is natural when cultures rub up against each other, there are commonalities and similarities to be found throughout East Asia, which is also seen in the food. For instance, dumplings are thought to have traveled through China to the rest of East Asia. We know them as jiaozi (China), mandu (Korea) and gyoza (Japan), and the various iterations have their subtle differences but are similar on the surface level.

Even the history of gimbap is itself murky—some historians argue it came to Korea via Japan during the occupation, that it was a direct evolution of Japanese futomaki. Others argue that gimbap was a natural, gradual evolution from the 14th-century Joseon era, when gim production began on the Korean peninsula and Koreans started wrapping rice in gim. Critics of the latter say that it’s an extension of Korean nationalism; gimbap is such a part of Korean

To reimagine Korean food, even in the diaspora, is to reckon with the history of the occupation and the questions it left behind. Even if this generation of chefs didn’t directly experience the occupation or the war, we have been affected by it.

nostalgia and culture that Koreans are loath to attribute it in any way to Japan.

It’s a fair point to consider, as well as a question that continues to chase me. Food cultures influence each other, and food evolves, and no one can deny that Japan has had an influence on Korean food. So why do I get so angry when people call gimbap Korean sushi rolls?

To reimagine Korean food, even in the diaspora, is to reckon with the history of the occupation and the questions it left behind. Even if this generation of chefs didn’t directly experience the occupation or the war, we have been affected by it.

Not all effects are negative. For example, David Chang, chef and founder of Momofuku, grew up with a grandfather who thought highly of Japan, placing Japanese cuisine over Korean cuisine. Based on his memoir, it seems that Chang internalized that prejudice, looking down on Korean food for most of his life, leading him, unsurprisingly, to open a noodle bar slinging Japanese ramen and avoiding Korean food until recent years.

And then there is the second layer of colonialism on Korean food that came from the U.S. via the military. After the U.S. dropped atomic bombs on two Japanese cities and brought an end to World War II, Japan’s occupation of Korea also came to a close.

However, instead of leaving Korea to the Korean people, recognizing the strategic position Korea occupied geographically, the U.S. and the then-Soviet Union divided

the Korean peninsula arbitrarily at the 38th parallel, with tensions rising until the Korean War broke out in 1950: the North backed by the Soviet Union, the South by the U.S. As U.S. troops moved in, they brought with them Spam, chocolate, cigarettes.

Budaejjigae (“army base stew”), a mash-up of kimchi, Spam and ramen noodles that is still popular today, is a direct result of military occupation and wartime poverty.

It’s impossible to communicate the depths to which the war has torn Korea apart and continues to do so. Technically,

the peninsula is still at war, divided with a border that separated families and split apart a nation. The North remains isolated, its borders closed, while the South has modernized at an enormous rate.

In the South, the first few decades after the war were marked by poverty. My parents told me stories of their childhoods in Korea, the ways in which they knew which of their classmates had money by the white rice, eggs and jangjorim (chilled soy-braised beef) in their lunchboxes, as opposed to poorer kids whose lunchboxes had rice mixed with other grains (like barley) and no beef.

The way Koreans eat has inevitably changed as Korea went from being a poor, war-torn country to the 10th largest economy in the world. With that economic growth has come a generation of young people who spend their youth in school and at after-school hakwons studying for the sooneung (university exam) to get into a top university, then from there into a top company.

The number of single-person households has risen as marriage rates have fallen, and Koreans no longer have the time or need to cook in the “traditional” way. Instead of making kimchi and jang, at home, Koreans go to the market. They go to the banchan store to buy pre-made banchan. As their pace of life has quickened, so has the desire for (and access to) convenience.

With a century of disruption behind them, in the face of all this modernization, there are Koreans in Korea who worry about losing their traditions. They’re investing money to preserve their history, primarily royal cuisine, which dates back to Joseon-era Korea and really emphasizes balance and the natural quality of ingredients with maintaining the king’s health as its primary objective. Seeing restaurants like Onjium, which opened a restaurant in New York City in 2021, equate “traditional” with “royal,” I’ve wondered if there isn’t something elitist about bypassing the more rustic and humble jip-bahp (home food) that feels to me like the heart of Korean food.

Or maybe my own focus is limited to the ways Korean food has changed over the 20th century.

“Inherently, the history of Korean food as we know it is quite short because there were a lot of things lost postKorean war,” Yoo says, “and then also the meteoric rise of the economy and society in general really has quickly affected what we know Korean food to be.”

Seung Hee Lee, author of the cookbook Everyday Korean and creator of Koreanfusion, offers another perspective.

“Royal cuisine is abundance,” she says. “And then Korea subsequently experienced war, Japanese occupation, like we had really shitty moments, and there was a lot of resilience that was incorporated into Korean tradition, which is to make something out of nothing.”

I find something profoundly beautiful and defiant in that, to move the goalposts of tradition back to a time when Korea was its own nation, before its borders were forced open to the West. Korea’s long history, before it was even Korea as we know it today, is tangled up with China’s and Japan’s, but it’s held onto its uniqueness and Korean-ness with fierce pride. In similar ways, it’s been beautiful and

delicious seeing Korean American chefs claiming this pride and redefining it for themselves. ***

Then there is also this: Until recently, Japanese cuisine was the main Asian cuisine allowed into the fine dining sphere in mainstream Western dining—for example, in 2021, 16 of New York City’s 68 Michelin-starred restaurants were Japanese.

Most others, including Korean food, were relegated to being cheap and grungy in order to be “authentic,” and therefore have value. The narrative has been shifting since the early 2010s, with Korean restaurants like Jungsik in Seoul and New York City, Gaon in Seoul and Atomix in New York City receiving Western recognition via Michelin stars and placement on The World’s 50 Best list, though the merits of both awards are debatable.

Korean cuisine as fine dining isn’t an odd concept, given the country’s long history of meticulous, detail-oriented food, which we see in royal cuisine. Lee, who has a certificate in royal cuisine from Taste of Korea, an institution in Seoul dedicated to preserving Korean traditions, tells me about things cooks had to do for kings in the Joseon era, from going into the mountains to catch pine pollen, to grating kilograms of ginger with a tool made of bone to create ginger starch for a tiny cookie, to picking off all the pointy ends of pine nuts so as not to irritate the king’s mouth.

We’ve seen threads of this extreme care in restaurants like Atomix and Kochi in New York City that call back to court food as inspiration. At Atomix, chef Junghyun (JP) Park looks to the surasang, the royal table, each course of the tasting menu reflecting a different part of what was once served to kings. At Kochi, chef Sungchul Shim plays with royal court cuisine and reinterprets tradition by serving every course on a skewer.

“Tradition,” though, is a complicated word, one that depends on the chef and their experience and background. Lee says that many of her traditional references are royal court food because she specifically trained in that discipline.

“For a lot of chefs, their ‘traditional’ is from their grandmother,” she counters.

Park says she keeps her idea of tradition broad, less about specific details, more as a general idea.

“I call it eating rice with soup and kimchi,” she says. “For me, that’s tradition. I see more of a structure, like keeping things structured.”

Neither is inherently more valuable than the other. Here, in the diaspora, Korean Americans have different relationships with this history and with their Korean-ness, and, over the last five to 10 years, we’ve been seeing this reflected in the range of Korean American cooking that reinterprets tradition into something new. That approach is still centered in New York City but increasingly found all over the country, in Chicago (Jeong, Perilla), the Bay Area (San Ho Won), Los Angeles (hanchic., Yangban Society) and elsewhere.

It’s been particularly fun to see chefs being more defiant in playing with the constant juxtaposition to Japanese-ness and claiming Korean-ness in that way.

At Kāwi, Park would fill her gimbap with raw fish, even though “traditionally” the proteins in gimbap are cooked, because why shouldn’t she use raw fish? Who said raw fish rolled in rice could only be Japanese? At Mari in New York City, Shim takes the Japanese hand roll and makes it Korean in the way the rice is seasoned and the variety of pickled banchan, sauces and garnishes served.

Whether these chefs’ intent is to decolonize Korean food or not, they are thoughtfully engaging with what it looks and tastes like to be Korean. This isn’t only happening at the fine-dining level, as culture flows in both directions, after all. Korean street food and jip-bahp have both been evolving and serving as inspiration for new ways of defining Korean-ness.

“That food is what trickled down from the royal court to the noble class to the commoners, and then the commoners ended up making their own versions of whatever the royal court cuisine is, and then that ends up becoming more like common comfort food and home food,” Yoo says.

And so, food evolves.

I still constantly ask myself: Why does this matter? Is it necessary for non-Koreans to understand and respect this distinction between Korean food and Japanese food? Does this all just stem from my own nationalistic pride? Why is it so important for me that people learn to use the correct words?

Yoo has grappled with this, too, and uses the example of pressed fish cakes, which have different names in Korean and Japanese.

“I grew up calling it oden, but the Korean version is eomook,” she says. “Sometimes, we’d be like, ‘We have to

decolonize ourselves,’ and call it eomook because that’s the Korean name, but, sometimes, you are actually just eating Japanese oden.

“I think we’re just in a struggle time where we’re transitioning out of the shadow of Japanese colonialism,” she continues, “and we’re either conscientiously making choices to decolonize our vocabulary and/or we’re also realizing that maybe it doesn’t really matter, and that two are one and the same, and that it’s more helpful for people to understand that, like, ume and maesil are the same thing.”

Some of these attempts at decolonizing admittedly do seem a little superficial to me. Recently, I learned that the spicy braised chicken stew I knew as dahk-doritang is now being called dahk-bokkeumtang. The dish itself hasn’t changed, but “dori” came from the Japanese word for chicken, “tori,” and, therefore, had to be replaced with “bokkeum,” which means stir-fried.

Dahk-doritang was admittedly redundant given that “dahk” is Korean for chicken, and dahk-bokkeumtang more accurately depicts how the dish is made—but what is gained in this attempt to decolonize the name of a dish?

In other instances, though, it feels crucial to learn to use the right language when discussing cuisine—for example, when writing about gimbap and Korean food, I find it inappropriate to call seaweed “nori,” even though gim and nori are technically the same thing. I wonder what makes the difference, a question I don’t yet have a clear answer for.

“I think it’s 100 percent being proud of the Korean language and culture and trying to keep the tradition,” Park says.

It ultimately comes down to respect. Lee puts it more humorously.

“There’s so many similarities as an outsider looking in,” she says. “French food, Italian food — it’s kind of the same. It’s creamy. They eat bread. It’s kind of like how Western people look at us, right? Koreans or Japanese—oh, they eat rice. They eat things in small bowls. They have this soupy thing on the side that’s kind of brown in color and made of soy, so it’s the same thing, right?

“If you look at it that way, you expect things to be intermingled, but there are some specificities that make specific cuisine,” she continues.

Specificity matters and respecting culture does, too. Diners might not have to know all this complex history to enjoy

Korean food. They don’t really need to know that a key difference between gimbap and futomaki is how the rice is seasoned, just like they don’t have to know that perilla and shiso aren’t the same thing or why doenjang and miso are different. They don’t even have to grasp the full history and why it makes many Koreans deeply irritated to hear Korean foods labeled as the Korean versions of Japanese things. They do, however, have to respect it.

Earlier in 2022, Lee hosted a pop-up with chef Jiyeon Lee in Atlanta, a seated tasting menu inspired by Korean royal cuisine.

“The way chef Jiyeon described why she was doing the pop-up was that—royal cuisine is respect,” she says. “The cuisine itself symbolizes respect to the king, and it’s respect to the guests. And that was her main message. We wanted to show grace and respect in the dishes.”

Park brings that same mentality into her modern Korean American food.

“For me, Korean food is all about jeongseong,” she says. “Like, guests are not going to know, but it’s all about jeongseong. And being patient.”

Jeongseong is a difficult word to translate pithily; it means sincerity, genuineness, a heart-felt emotion that runs deep and exhibits in care. Korean food is a labor of love, food that takes time and attention—kimchi is a laborious process that takes at least two days, jangs take months to ferment, gimbap requires you to make each individual filling before rolling everything in rice and gim.

And maybe it’s that heart that’s been the through line in Korean food, from royal cuisine centuries ago to the jipbahp of the postwar to the Korean American food we’re seeing today—that, even though so much trauma and violence was wrought upon Korea over the 19th century, Korean food has retained this care, even as the food itself has continued to evolve in both Korea and the diaspora. There is a reason the question Koreans ask to express love is, “Have you eaten?”

The idea of Balkan cuisine brings up questions around what a nation is and who is considered ‘other.’

TEXT Irina Janakievska

“ Violence was, indeed, all I knew of the Balkans.” writes Dame Rebecca West in Black Lamb and Grey Falcon (1941), her magnum opus on the history and culture of Yugoslavia.

Violence and instability are what many still associate with the region. From their designation as the European powder keg that sparks world wars through to the fragmentation of former Yugoslavia, the Balkans have long been the object of such derogatory stereotyping. The effect of this has been to overshadow their beautiful cuisine.

Delineating the Balkans is complicated. Although the name has become an increasingly recognized form of academic reference, to date there is no real geographical, historical or political consensus where the borders of the Balkan Peninsula or the Balkans lie, and no real consensus as to which nation-states, or peoples, are included in the undefined and potentially indefinable contours of the Balkans.

Even the etymology of the word “Balkan” is convoluted. The conceptualization of a specific Balkan region emerged within the Ottoman Empire at the turn of the 19th century.

The term was an Ottoman Turkish word for a wooded mountain range, referring to what are now known as the Balkan Mountains, but then known by locals in Slavic as Stara Planina (Old Mountain), among other names.

It is possible the Ottoman Turkish word has a Farsi root— bālkāneh or bālākhāna (high, above or proud house). NonOttoman sources used the term Haemus (or Aemus, or other variants) for the same mountain range, derived from an ancient Thracian term for mountain ridge.

In (perhaps overly, perhaps necessarily) simplistic and practical terms, though, the Balkans are in Southeastern Europe. They lie between the Adriatic Sea in the northwest, the Black Sea in the northeast, the Turkish Straits in the east, the Aegean Sea in the south and the Ionian Sea in the southwest. The land border is thought to extend along the Julian Alps and run, from Vienna, along the Danube River.

So, thinking in current global map terms, they comprise nation-states born out of the demise of the former Yugoslavia—Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia, Montenegro and Kosovo—as well as Albania, Bulgaria, mainland Greece and parts of Romania, Hungary and Turkey.

These are ancient lands where Europe meets Asia; they have been both the birthplace of civilizations and the thoroughfares of empires, the latest being the AustroHungarian and Ottoman Empires. A constellation of events

in the late 19th and early 20th century sealed the perception of the region as anarchic, violent and uncivilized.

The waning power of the House of Habsburg and the House of Osmanli created a power vacuum, an environment rife for the emergence of new nation-states, Serbia, Greece and Bulgaria, as well as irredentist movements, each of which pursued policies of extending its power and influence in the region through any means necessary, including military force both against the fading empires and each other.

The First Balkan War broke out in October 1912, when Montenegro declared war on the Ottoman Empire and an alliance between Serbia, Greece and Bulgaria saw the expulsion of the Ottoman Empire from Macedonia and Thrace.

This was soon followed by the Second Balkan War in June 1913: Bulgaria attacked Serbia, which in turn allied with Greece, and the strategically and economically important historic region of Macedonia (including the port of Thessaloniki) was carved up between Serbia and Greece under the Treaty of Bucharest, Misha Glenny writes in The Balkans: Nationalism, War and the Great Powers 1804–2012 (2012).

Events culminated with the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo in June 1914 which in turn was perceived as the trigger for global calamity—the outbreak of the First World War, imperial collapse and socialist revolution, Glenny writes.

In The World Crisis, 1911–1918 (2005), Winston Churchill wrote of an alleged statement by the German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck describing Europe as the powder-keg and warning that the next European war would be set off by some “damned foolish thing in the Balkans.”

The Balkans became Europe’s powder keg.

The region had often served as the “other” within Europe, Maria Todorova posits in Imagining the Balkans (1997). She coined the term “Balkanism,” a concept situated within ongoing theoretical debates in relation to orientalism and post-colonialism.

Unlike the imagined “Orient,” the imagined Balkans were relatively precise in geographical terms, they were European, there was no experience of a real colonial past, the population was considered white and (around 1900) much of the population was Christian. They served as a repository of negative characteristics upon which a positive and self-congratulatory image of the European

had been built, Dr. Hannes Grandes suggests in a review of Todorova’s book for Reviews in History . The Balkans were imagined—that is, conceptualized—as the European cultural other.

This stigmatization gathered momentum throughout the 20th century and was reignited with the dissolution of Yugoslavia in the 1990s. Although the Yugoslav wars did not embroil the entire region in conflict, “persistent use of ‘Balkan’ for the Yugoslav war[s]…re-kindled old stereotypes and licensed indiscriminate generalisations about the region,” Todorova writes. The Balkans, once again, became synonymous with instability, unpredictability and violence.

What does all of this have to do with food? Everything.

Food can become the manifestation of rivalries, an extension of the imperialist imperative to dominate, extend influence and reinforce the myth of the nation-state. A means of creating the “other.”

For me, the central theme that runs throughout the history of the Balkans is the emancipation of nations from empires and establishment of nation-states as distinct from nations. A nation-state does not necessarily encompass the extent of an imagined nation based on ethnic, linguistic, religious, cultural, geographical, historical or other myths, but it can still give rise to another phenomenon of nationalism: irredentism.

This requires the liberation and reunification of any part of a nation left outside the current borders of a nationstate. An irredentist would therefore seek to dominate or eliminate an “other” through the acquisition of or claims over territory deemed to form part of the relevant nation, and to subsume it within the existing nation-state.

Once formed, a nation-state would seek to consolidate the myths upon which it has come into existence and construct a national narrative that would require, to varying degrees, the negation of the past in its entirety or silencing certain aspects that are not compatible with the national ideological framework, and the manufacture of the present.

In culinary terms, this would manifest in, for example, the designation of a national cuisine or a national dish. In a scenario where, let us say, an irredentist was thwarted and the nation-state’s current borders do not match the mythical extent of the nation, does designating a cuisine or a dish as “national” purport to stake an irrefutable

claim over that cuisine or dish? Well, yes, that is generally the intention.

Does it automatically preclude another nation-state from ever having elements of that nation-state’s national cuisine or sharing the same national dish? Clearly not.

Moussaka is a serious contender for one of the national dishes of Greece, but moussaka is made beyond Greece’s borders. It may not always have the iconic French-style béchamel topping adapted by Nikolaos Tselementes, which distinguishes it as Greek moussaka, but variations on the theme of layers of a tomato-based ground meat sauce or sometimes chickpeas interspersed with fried or grilled aubergines, courgettes and/or potatoes are eaten across the Balkans and also called moussaka (musakka in Turkey, messa’aa if you are in Egypt, or musaqa’aa across the rest of the West Asia and North Africa).

Does it denigrate the existence of similar or related cuisines or dishes or stereotype them as derivative? It could, especially if taken in the context of a region’s history and prevailing political climate. Let us take shopska salad, an iconic salad eaten across the Balkans made with chopped tomatoes, cucumbers, onions, sweet long green peppers typical of the region, occasionally parsley, with either a basic red wine vinaigrette or just oil, topped with grated or crumbled sirenje or sir (a brined white cheese, similar to feta).

The name is derived from a mountainous region called Shopluk which transcends the borders of Bulgaria, North Macedonia and Serbia and is inhabited by a separate ethnic group called the Šop or Shopi who are highlanders or mountain shepherds. In composition, it is like Turkey’s Çoban or Choban salad (shepherd’s salad), and it would not take a huge leap of imagination to etymologically go from the words shopluk to choban or vice versa.

Shopska salad is often claimed as the national dish of Bulgaria and much has been written on its Bulgarian nationality, its colors purportedly resembling those of the Bulgarian flag. Yet, it is eaten across the Balkans and called the same name.

On the face of it, calling shopska salad Bulgarian seems harmless. In reality, this is a modern iteration of a historical issue: the Macedonian question, part of which is Bulgaria’s claim over the historic region of Macedonia. That, along with Greece and Serbia asserting ownership of the area, prohibited the creation of a Macedonian nation-state at the start of the 20th century.

It is also indicative of the current political tensions between Bulgaria and North Macedonia—specifically, Bulgaria blocking North Macedonia’s European Union accession process until it accepts Bulgaria’s claim that Macedonian identity and language are of Bulgarian origin, according to “Bulgarian PM Optimistic About Resolving North Macedonia Dispute,” a March 29 article Sinisa Jakov Marusic wrote for Balkan Insight. Claiming the national identity of a simple salad then becomes a symptom of the assertion of dominance of one national identity over, or to the exclusion of, another.

There are similar ongoing debates on the nationality of ajvar, a vegetable preserve made either with justroasted red peppers (like in Leskovac in Serbia) or with roasted red peppers from Strumica and aubergines (in North Macedonia). The reality is that ajvar, and countless variations of it, are eaten across the Balkans.

And let’s not forget sarma, a dish that truly transcends borders and, in the Balkans, has become a combination of the Levantine penchant for wrapping things in leaves and local customs, ingredients and a love of fermentation.

There is a winter sarma made with lacto-fermented (sour) cabbage leaves—the meat version filled with ground meat (beef or pork), rice, herbs and paprika and flavored often with smoked meat, the meat-free (posna) version filled with just rice, vegetables, herbs and spices. Spring and summer sarmas use any seasonal edible leaves—fresh cabbage, of course, beetroot tops, kohlrabi tops, spinach, chard, sweet dock, young hazelnut leaves, marshmallow leaves and, for me, the ultimate, young vine leaves (lozova sarma or dolma).

Despite the relatively fixed nature of the current borders of Balkan nation-states, ongoing political tensions relating to North Macedonia, Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina notwithstanding, longstanding questions of identity, language, ethnicity, territorial claims and irredentist aspirations can become, directly or obliquely, the object of discussion through food. It is culinary nationalism, or perhaps more dangerously, irredentism. Food is not, and should not be, a nationalist fig leaf.

Admittedly, there are clear benefits to defining or delineating cuisines, dishes or food products along national lines. For example, for existing nation-states, it can serve as a bastion against cultural appropriation. For nation-states denied self-determination or whose very reason for existence is still being challenged on historical, geographical, political, cultural, ethnic, religious, linguistic or other grounds, food becomes a way of preserving

identity—a way of claiming and ensuring the continued psychological, emotional, spiritual (if not geographical) existence of a nation.

Although the concept of a national cuisine, like the nation-state it attaches to, is a myth, it would be remiss to underplay the importance of food in the intricacies of identity—real or imagined.

Food can also be attached to cultural, ethnic or religious groups and this may be more meaningful than a delineation along national or nationalistic lines. Much of our perceived identity as humans is inextricably linked to a place, our roots in the lands we emerge from, the food— bounty from those lands—ensuring our survival, physical, cultural and spiritual.

At a time in our global history of unprecedented migration, forced or voluntary, when so many are uprooted from the land they call home, food becomes the thing that can be uprooted and travel with us, either through a few tomato or pepper seeds smuggled in a suitcase to be replanted or jars of grandma’s homemade wild green fig or quince slatko (spoon-sweet).

Food becomes one of the most effective ways of maintaining a connection to our place of origin and preserving a sense of identity. We can, through food, be at home anywhere in the world. We can, through food, preserve our memories and share an elemental part of ourselves with people we love, so they can experience the flavors preserved in our memories, and understand us and the land we come from.

Food becomes one of the most effective ways of maintaining a connection to our place of origin and preserving a sense of identity. We can, through food, be at home anywhere in the world.

Yet, given the ambiguous-at-best relationship between a nation, a nation-state and region, food—which transcends any modern physical political borders—is inherently antinationalist. The relatively recent emergence of nationstates means that delineating cuisine or dishes along national lines can have the effect of negating history that predates the establishment of the nation-state, thus trivializing the interconnectedness of ancient foodways.

Food remains an artifact that evidences and preserves the past and the underlying foodways that have led to its existence more stubbornly than anything. Consider Turkish manti, little dumplings filled with spiced ground meat, baked then boiled and served on garlicky yogurt with a pul biber infused butter. Now consider mantou (or baozi or jiaozi) made in the ancient imperial Chinese courts.

Consider similar dumplings made by the Uyghur peoples of Northwestern China. Consider buuz eaten across the Mongolian Empire. Then imagine these dumplings being carried across Central Asia and the South Caucasus by Turkic and Mongolian horsemen. Imagine their adaptation to suit the Ottoman palate in the Sultan’s kitchens at Topkapı Palace in Istanbul. Imagine Ottoman soldiers, like their ancestors, taking manti on horseback into the Balkans. Imagine the people of the Balkans taking inspiration from Ottoman manti and making mantije/mantii but adapting them to local customs of breadmaking to create ground meat–filled baked pastry parcels.

Then imagine ravioli-like dumplings filled with ground meat, boiled and either served on or baked with a garlicky yoghurt sauce and topped with a sweet paprika–infused butter but called klepe/kulaci—a fusion of Ottoman manti and Italian filled pasta, made in Bosnia and Herzegovina and parts of Croatia (a region where Ottoman, AustroHungarian and Venetian influences met).

Imagine how food has traveled and acquired its layers, flavors, textures, how it is adapted in moments of inspiration and love by the hands that made it somewhere in the world using ingredients available from their land and inherited cooking techniques and tools. Then consider the ever-present historical threads food carries with it and how connected we are, always.

Now, imagine Balkan cuisine. A concept just as elusive and complicated as the contours of the Balkans; Balkan cuisine is a construction, an invention, in much the same way as national cuisines and national dishes. For a relatively small region, the myriad influences of history, politics, ethnicity, language, religion, landscape and climate have resulted in the development of undeniably unique and diverse culinary practices and traditions. Amalgamating them under the banner of Balkan cuisine, much like any integration implicit in the creation of a national cuisine, can be detrimental because any differences or nuances become less pronounced or simply lost in favor of the greater whole.

But, in the concept’s implicit regionalism lies (some) salvation.

Balkan cuisine is a necessary artifice—a safe space from which to explore and celebrate both the commonality across, and the culinary diversity of, the Balkans without falling prey to the problematic delineation of cuisine along national lines and inadvertently perpetuating nationalist or political agendas.

Identifying as a “food writer, exploring and writing about Balkan cuisine,” by imagining the cuisine of an imagined Balkans, I am undoubtedly guilty of Todorova’s Balkanism. Yet, I am the “other,” writing from within my otherness. As a white European, I am perhaps not an obvious other, but I am the European other. The other on the doorstep of Europe (to borrow a phrase from Tony Blair discussing Kosovo in 1999). The other whose narrative, food or otherwise, has been excluded from, otherwise subordinated in favor of or subsumed by the dominant European narrative.

So, I find myself naturally drawn to and finding commonality with the narratives of other global cultures from around the world that have faced such cultural othering. I find myself, perhaps naïvely, attempting to take ownership of the symbolic othering of the Balkans, to reconfigure the negative perception of them through food and create a counternarrative intended to give a voice to and

incentivize the discovery of the region’s beautifully unique culinary heritage.

Inherently supranational, the concept of Balkan cuisine can and should transcend the modern political borders of Balkan nation-states and the problems of culinary nationalism. With all the complexities and ambiguities of the Balkans, food, more than anything else, is where the historical, cultural, political, ethnic, religious and geographic narratives overlap. Through food, we can discover and celebrate both similarities and differences. We can better understand and appreciate our common heritage and the intricacies of the region’s culinary traditions, while ensuring the preservation of all cultural and historical layers of identity, despite their difficult historical and political dimensions.

“Balkan cuisine” has, in short, the potential to go some way toward mending ties broken by conflict. It offers a way forward for objectively preserving the culinary practices of the region to avoid them being neglected, destroyed, amalgamated into a national myth, externally appropriated or worst of all, forgotten. It is possible, through a shared love of food, to look past nationality, ethnicity, religions and modern political borders and celebrate the culinary and cultural heritage and history of the Balkan powder-keg.

In the case of the Balkans, that culinary and cultural heritage is the result of an amalgamation of ancient, Indigenous civilizations and empires that have either emerged from or passed through the region. The former’s cooking techniques and ingredients have been impacted by the region’s historical connections with and influences

Here, food is all-encompassing, an accompaniment to every important occasion, celebrating life, death and everything in between.

across the world (including Slavic, European, Caucasian, Turkish, Arab, Jewish and Persian). Walnuts, pomegranates, roses and wine were in all likelihood brought to the region (and Europe) by Alexander the Great’s soldiers returning from their conquests.

Balkan cuisine reflects natural conditions across the region, socioeconomic factors, religion. The climate and topography ranges from Mediterranean in the south and along the Adriatic, allowing olives, figs, grapes and many sun-loving fruits to flourish, temperate across the central, rolling arable and forest regions, to extremely harsh and bitterly cold across the rugged mountains and mountain forests.

The same mountains offer not only wild game, but extensive upland grazing, allowing for the production of delicious cheeses, including sirenje or sir made from sheep, cow and goat milk, hard yellow cheeses like kashkaval or fresh whey cheeses like urda, as well as yogurts and other dairy products like kajmak, a salted, preserved clotted cream.

This combination of the Mediterranean, Adriatic and mountain ranges makes for unique terroirs across the region which is particularly suitable for wine production both of international and many indigenous grape varieties including whites such as Temjanika, Žilavka, Smederevka, Moravia, Malvazija, Graševina, Assyriko, Krstac, and reds such as Vranac, Plavac Mali, Crljenak Kaštelanski, Dingač, Prokupac, Teran, Kallmet, Babic, Mavrud, to name a few.

Grain and livestock dominate the vast, fertile Pannonian plains of Vojvodina. Coastal areas are naturally dominated by fruits of the sea, from the brodet (seafood stew) made all along the Adriatic coast, to mussels that are abundant in the depths of the Bay of Kotor, eaten buzara style in Montenegro and Croatia. Inland areas use fish like trout, carp and eels from the lakes (famously Lake Ohrid and Lake Skadar) and rivers of the region’s water systems and, of course, meats, which are cured, grilled, slow roasted or otherwise slow-cooked.

In the southern regions, sunflower oil forms the basis for cooking; in coastal regions, olive oil. As you move inland and north toward Central Europe, lard reigns supreme, but it’s used throughout the region for baked goods, religious affiliation permitting. Some regions are characterized by the production and use of wheat, others by millet, rye, maize, rice or buckwheat.

Breads and grains form the basis of the Balkan diet, supplemented heavily by dairy and fresh fruits and vegetables, though naturally immediate geographic reality has an influence on the local diet, with coastal areas

varying significantly. Lush fruits and vegetables dominate the entirety of the region; they’re eaten seasonally and preserved for winter. Herbs are gathered for cooking as well as medicinal purposes.

Different socioeconomic factors have resulted in a distinction between the food enjoyed in the cities and towns versus more rural areas. Christianity, Islam and Judaism have food uniquely associated with their respective customs and traditions.

The thread that runs through it is a shared culinary ethos and way of life is living off the land respectfully, using all its cultivated and foraged bounty seasonably, wasting nothing. It is a cuisine which is infinitely creative out of necessity—the vestiges of empires, poverty, conflict have created a Balkan cucina povera and created something truly special out of almost nothing.

Humble local ingredients, for example white kidney beans, are turned into an extraordinary number of dishes. Bean salads and dips, soups and stews (grav, grah or pasulj) or slow-cooked then baked (tavče gravče or prebranac), always with a variety of herbs, spices, vegetables and sometimes padded out with a little bit of meat for special feasts.

Here, food is all-encompassing, an accompaniment to every important occasion, celebrating life, death and everything in between. Despite our stigmatization as the “other” and the relegation of the region as the powder-keg of Europe, we are bālkāneh (proud).

Of everything that man erects and builds in his urge for living nothing is in my eyes better and more valuable than bridges. They are more important than houses, more sacred than shrines. Belonging to everyone and being equal to everyone, useful, always built with a sense, on the spot where most human needs are crossing, they are more durable than other buildings and they do not serve for anything secret or bad.

Ivo Andrić writes this in The Bridge on the Drina (1945). It encapsulates perfectly how I feel about Balkan cuisine. It is a bridge that we can use to cross beyond stereotyping the Balkans, to focus instead on the incredible cultural wealth of the region and the beauty of its food.

Filipino food looks radically different today than it would have a century ago. In a country that’s seen so many changing empires, we look at how traditional cuisine is established.

TEXT Mark Corbyn

PHOTOGRAPHY Martin San Diego

Up in the Peak District, the gently picturesque national park in the Midlands of England, you can find the little market town of Bakewell. Composed primarily of tidy Georgian townhouses, it sits prettily on the banks of the Wye, complete with lazing ducks and a medieval bridge spanning its reach.

Every time my wife and I visit the Peak District for our annual hiking trips, we always try to make time to visit the town, to take in the sights and try its culinary delights. If you know English puddings and pastries, the Bakewell name probably rings very familiar, for it is indeed the home of the Bakewell pudding.

As the story goes, the Bakewell pudding originated sometime between 1820 and 1860, when a cook at a local

inn, misunderstanding a strawberry tart recipe, accidentally poured jam into a puff pastry case before the almond custard mix. The resulting pudding was deemed to be a happy accident, and as they say, the rest is history.

The pudding is now a steadfast part of Bakewell’s modern identity, with at least three bakeries and many more cafés and restaurants peddling what each claim is the best version. And by best, they of course mean the one that hews closest to the original recipe. The idea of a Bakewell pudding is set in stone, much like the town itself.

Ask your average Brit, though, about Bakewell puddings and their history, and you might receive a rather nonplussed response. For how often do we all really think about where our favorite foods originate from?

Coincidentally, it was on our return from the Peak District last October, laden with Bakewell puddings, when I came across news from the Philippines of the death of Leticia Hizon, founder of the Pampanga’s Best company. I was vaguely aware of the company, having seen its meat products in the frozen aisle of supermarkets back in the Philippines. I thought it might be interesting to read a bit more about the woman behind it all.

“As the founder of Pampanga’s Best, the inventor of the original Tocino, and as a philanthropist in her community, her contribution to the Philippine economy is immeasurable. Likewise, her influence on Filipino cuisine cannot be overstated,” ran the statement released by her family.

I quite distinctly remember pausing for a good long moment. For someone who thought they knew a lot about tocino—having eaten it for most of my life, and having even developed a recipe for my catering business—that short statement was quite a revelation.

Tocino is a reddish-colored, sweet-cured pork that can be found all over the Philippines and the diaspora. Most Filipinos, certainly those who have attended my pop-ups and supper clubs, have nostalgic memories of enjoying it for breakfast and merienda. It is a hit whenever I have it on my menu.

But was it really invented in the 1960s by Hizon, a schoolteacher? Given its Spanish name, and its appearance bearing a passing likeness to Chinese char siu, I’d always assumed that it had developed during the Spanish colonial period, when the Philippines’ melting pot of Austronesian, Hispanic and Chinese influences really took shape.

Asking some of my friends about it, they had assumed the same. And why would we think otherwise? We’ve been eating it all of our lives, like most of the other Filipino dishes we grew up with; of course we’d think it’s been around forever.

But, as Hizon’s story goes, when her meat vendor neighbor returned home from the market with 5 kilograms of unsold pork, she decided to buy all of it and to cure it so that it wouldn’t go to waste.

However, instead of making the traditional pindang babi or burong babi (Kapampangan for cured pork and fermented pork, respectively), she modified her recipe so that it would be sweeter, softer and less sour. Happy with the result, she borrowed the Spanish word for bacon and christened her version tocino.

So, not really Hispanic, and not really Chinese either, but an evolution of a wholly indigenous dish and technique, one with a very old pedigree. And yet, Hizon had decided to align her product with the Philippines’ Spanish heritage.

It would not have been the first time in the country’s history that happened. I think immediately of arroz caldo. The name is Spanish for rice broth, right? Though originally known as congee or lugaw, i.e. rice porridge, it acquired its Spanish moniker in the 1800s when Filipino-Chinese restaurant owners sought to make the dish sound more respectable in colonial society.

At the time, arroz caldo was an umbrella term for many different types of lugaw. But gradually, versions that shunned offal, prioritized choice cuts of meat and used kasubha (safflower) to mimic the colorings of saffron came to the fore, and gradually “arroz caldo” began to specifically refer to those versions. Nowadays, it is classified as a type in its own right, with its own set of ingredients, and it’s celebrated as a much-loved comfort food.

Lugaw, on the other hand, now has some negative connotations attached to it. One only has to look at the pejorative nickname targeted at Leni Robredo, the unsuccessful contender in the recent presidential elections: Leni Lugaw. In the eyes of her critics, Robredo was weak, watery, bland and unsubstantial—just like lugaw. And when her campaign team started serving the dish at her rallies, in

an attempt to claim ownership of the insult, Robredo was accused of being patronizing to the masses by assuming that the only food they deserved was the poverty staple of lugaw.

I see something similar in the way that tocino has become a beloved breakfast staple, achieving a prominence that far exceeds that of the pindang babi and burong babi that it evolved from. The deliberate choice of tocino as a name not only lent Hizon’s creation a hint of Hispanic prestige, but I feel also made it feel less Kapampangan.

Cut off from its regional roots, tocino could be seen as more of a general Filipino dish, one that could be accepted more readily elsewhere across the country. Indeed, Hizon’s creation proved popular enough that Nora Daza, considered the first celebrity chef of the Philippines, even included a tocino recipe in her Let’s Cook with Nora (published 1965 and updated in 1969) and Galing Galing (1974) books. In her introduction to the first book, she remarked that the recipes within, tocino included, were what she considered “the tastiest, most practical, nutritious, reasonably priced and popular in the Philippines.”

Daza’s books were primarily targeted toward the burgeoning urban middle classes, particularly those based in the capital of Manila and its environs. Having migrated from the provinces for the economic opportunities of the rapidly-growing capital, Daza’s target market was in search of a more cosmopolitan and refined lifestyle, especially when it came to food.

Her recipes are a heady mix of internationally inspired dishes (beef stroganoff, Hawaiian meatballs, Jamaican Banana), aspirational branded creations (Nescafé à la Jetset) and Filipino classics—a potent combination that proved to be extremely successful for Daza. Her inclusion of tocino may very well have helped to popularize the dish and introduced it to a whole new generation of cooks and diners.

Cut off from its regional roots, tocino could be seen as more of a general Filipino dish, one that could be accepted more readily elsewhere across the country.

And, without any introduction to explain its Kapampangan roots or to provide any other context, these cooks could assume tocino to be similar, in terms of background and stature, to the many prestigious Hispanic-influenced fiesta dishes, like kaldereta or chicken relleno or mechado, that Daza so favored.

***

The most common way in which tocino is enjoyed these days is as part of breakfast, and more specifically as part of a silog breakfast. A silog is both a combo dish and a Tagalog portmanteau that combines sinangag (garlic fried rice) and itlog (fried egg) with a protein of choice. So, for example, we have tosilog with tocino, longsilog with longganisa, bangsilog with bangus/milkfish and Spamsilog with, you guessed it, Spam.

A common feature of the proteins favored for a silog is that they feature some form of preservation: drying, curing, fermenting, even canning. Alongside garlic fried rice, which like all fried rices developed a way of using up and refreshing old rice, the meal is a potent symbol of old prerefrigeration foodways. Even the Cebuano word for breakfast, pamahaw, comes from the root word bahaw: old or leftover food.

A common feature of the proteins favored for a silog is that they feature some form of preservation: drying, curing, fermenting, even canning.

“This may have started as a time-saver and a wastepreventative,” wrote Dr. Doreen G. Fernandez, the late esteemed food writer, about these sorts of Filipino breakfasts in Tikim: Essays on Philippine Food and Culture. Fernandez recounts youthful pre-World War II treats of sinangag with tapa (cured beef) at the historic Ambos Mundos restaurant in Manila, and she recalls her father’s favorite breakfast of rice, eggs and salted fish. Whatever the protein used, this is a quick and easy meal that provides maximum comfort from minimum effort. Indeed, the first meal my wife and I had when bringing our firstborn back from the hospital was a hearty plate of longsilog.

There is, however, another layer to the story of the silog. In a 2014 interview with ABS-CBN News, Vivian del Rosario, the owner of Tapsi ni Vivian in Metro Manila, talked about the origin of her business in 1986:

Nagtinda din ako ng tapa at mga sinangag. Naisipan ko mag-imbento ng pangalan, ‘yun nga ang sinasabi nilang tapa, sinangag at itlog. Shinortcut ko ng ‘tapsilog.’ Ako ang kaunaunahang nag-imbento ng tapsilog.

(I was selling tapa and other fried things. I thought of inventing a name, because people always said tapa, sinangag and itlog. So I shortened it to ‘tapsilog.’ I was the first to invent tapsilog.)

Thirty-six years on, the silog name is everywhere; some attribute this to the love of Filipinos for turning everything into an abbreviation, acronym, portmanteau or argot. Now, eateries and chains aplenty in the Philippines (including McDonald’s) offer some variation of it, and abroad it has become a marker for the diaspora that can be easily bought into and replicated—no doubt fueled by the fact that frozen bangus, tocino and longganisa proliferate in Filipino shops around the world.

The silog format, now fairly defined as a distinct meal in its own right, has superseded its breakfast predecessor in much the same way that tocino, arroz caldo and countless other dishes have done with their own forebears. And if we extrapolate this to the rest of Filipino food, we can start to get a sense of how this cuisine has shifted and evolved into what it is today: an eclectic mix of Austronesian, Chinese, Hispanic and American influences.

One might be tempted to ask whether, when our dishes evolve, we lose a little something along the way.

Fernandez wrote in Tikim that early in her career, she “lamented the cultural amnesia, the cultural loss” that she saw around her in Manila, where people and the food they ate were increasingly divorced from their original roots.

Were the vendors who developed arroz caldo out of lugaw guilty of this? And the middle classes who cooked from Daza’s book, preferring the more sophisticated sounding tocino over the provincial pindang babi?

How about those of us in the diaspora, cut off from the traditional techniques and ingredients, and unaware of the vastness and variety of our cuisine? Sachets of tamarindbased powder mix, as a stand-in for the many different sour fruits used to provide tang for sinigang; peanut butter in kare kare instead of ground roasted peanuts; ube flavoring in lieu of the actual purple yam.

It’s understandable, of course: Lacking the proper ingredients, either through availability or cost, we have to make do with what we can. How much does this change the dish, though?

When I make bibingka (baked rice batter cakes) with rice flour and baking powder instead of galapong (fermented ground rice), producing a lighter and fluffier product, am I shifting the perception of what bibingka is? When Ferdinand "Budgie" Montoya, owner of Sarap, started selling his famed London lechon, did he establish a new variant of the famous Filipino roast pig? Does diaspora cuisine always become different from that of the homeland?

I, like Montoya and our other contemporaries, am quite happy to make the changes to our dishes to suit our situation. When done with full awareness of where a dish comes from and how it has been made in the past, such changes can be extremely powerful in helping us to take dishes forward and, importantly, to keeping them relevant. Despite her initial fears about the state of Filipino food in Manila, Fernandez did say that the more she researched and learned about the food that her contemporaries ate, she increasingly came to see that while it may have taken

When done with full awareness of where a dish comes from and how it has been made in the past, such changes can be extremely powerful in helping us to take dishes forward and, importantly, to keeping them relevant.

different forms, it was still in essence our indigenous food, and people kept on coming back to it.

“They are hooked on its flavors, which are ingrained in their consciousness,” she writes.

And in a sense, perhaps that’s what has been happening with Filipino food over the decades, even centuries. The forms may have changed to stay relevant, but the flavors are still there. We eat the dishes that we do because, quite simply, they are still damn delicious. And at the end of the day, is that not what we want from our food?

We can now order Bakewell puddings online for delivery down to London, a pivot driven by the vicissitudes of the Covid-19 pandemic, and a welcome one at that. As much as I like eating them, quite frankly, I think I prefer their modern descendants, the cherry Bakewell slice. Knowing the origin of the Bakewell pudding, though charming and nice, and certainly part of the appeal of going to the town itself, doesn’t really supersede other factors that influence what we eat on a daily basis.

Learning about Leticia Hizon’s and Vivian del Rosario’s stories might make me pause for thought when I next make tosilog, but ultimately I am making that breakfast because my wife and I love eating it.

Food origin stories can be complex, and they can change depending on who’s telling them. With every small adaptation that I and millions of others make to the dishes we eat, the waters will continue to get increasingly muddied. But that shows that the dishes are alive, and if they have a life of their own, then they will continue to grow with and nourish us for many years to come.

In one Oaxaca town, a three-day process of slaughtering and cooking pigs is essential to an Indigenous changing-of-the-guard event.

TEXT & PHOTOGRAPHY Fabricio González Soriano & Renée Alexander

Four fat pigs lounge in the dappled shade of Isidro Pérez Pérez’s backyard, each tethered to its own tree by a thin rope looped around a back foot. The pigs don't yet know it, but soon they’ll be the stars of the ceremonial soup at the center of San Mateo Yetla’s annual Cambio del Bastón de Mando, or what English speakers might think of as the changing of the guard.

As the outgoing Fiscal, the community’s top political and social authority, Pérez will host a series of events over the next three days, including a ritual pig slaughter, communal cooking and meals, a candlemaking ceremony and a latenight dance party with a live band. The festivities will culminate in a group procession to the local church, where a religious service precedes the official handover of duties to the incoming Fiscal and other community leaders.

Though civic power is transferred administratively each January 1, Yetla’s transfer ritual is mandated locally for January 6. According to some community members, their ancestors prescribed the date to ward off the frequent death of infants, which had devastated the pueblo in a

past so distant that it is lost to memory. Curiously, in the Catholic liturgical calendar, January 6 is also Three Kings’ Day, which alludes to the biblical story of children being hidden from King Herod, who—upon learning of the birth of Jesus—had ordered the killing of all boys in Bethlehem under the age of 2, to prevent the prophesied king of the Jews from taking over his throne. In many parts of Mexico, including this region, Three Kings’ Day is celebrated by baking a loaf of sweet bread with a tiny doll hidden inside.

Though the Mexican government has sought to separate religious and civic life since La Reforma (The Reform) in the 19th century, the codependence among these entities persists in Indigenous and rural communities.

In order to carry out the cambio de bastón on January 6, two days of preparation are required: one to slaughter the pigs for the feast, and another to pour and cool the candles used in the ceremonial transfer of power.

This annual festival offers a clear demonstration of the combination of religious elements, social organization,

Yetla’s festivities feature Caldo Rojo, the deep-red, brothy soup that will be created today as a teambuilding activity for the men and women serving together on cargo committees.

political structure and local gastronomy. It’s one of the biggest parties of the year in this 600-person Indigenous community in Oaxaca’s mountainous Chinantla region, in southern Mexico.

But for 70-year-old Pérez, the retirement celebration is bittersweet. He lost his wife, Esther Antonio Andrés, unexpectedly in November, several weeks shy of the end of his year of service as the town’s top civic official.

Like his predecessors over the past two centuries, he was elected to the ultimate position as Yetla’s Fiscal following decades of service to the community, as he worked his way up through the ranks of a municipal structure known as the cargo system.

Every third year, he took on an unpaid, full-time position: caretaking the community cattle herd, maintaining the church, managing the ecotourism center and organizing community festivities. His final duty upon retirement is to satisfactorily fulfill the Mayordomía requirement by hosting this three-day celebration.

The cargo system lies at the heart of self-governance in semiautonomous regions throughout Southern Mexico.

Under this system, unpaid service is mandatory for each community member, as part of the usos y costumbres (uses and customs) that preserve Indigenous ways of life. Historians mostly agree that the system has been practiced since the 16th century in hundreds of towns and villages throughout Mesoamerica. According to anthropologists Dr. John K. Chance (University of Denver) and Dr. William B. Taylor (University of Virginia), the hierarchical system of ranked offices is, “[o]vertly Spanish in structure, but with some indegenous underpinnings,” and “[a]ll local men are

expected to ascend this ladder of achievement during their lifetimes.”

Although the pueblos participate in—and are officially governed by—the country’s political party system, elected municipal authorities respect and often defer to community-chosen councils of elders who have completed their cargo tenures. For instance, while municipal authorities determine how much money the pueblo will receive from the federal government, local community leaders decide how the money is spent.

The Cambio del Bastón marks the annual rotation of cargo posts, or charges. Each community's festival looks a bit different. Yetla’s festivities feature Caldo Rojo, the deepred, brothy soup that will be created today as a teambuilding activity for the men and women serving together on cargo committees.

Legend has it that Caldo Rojo was central to the community's first Mayordomía del Pueblo, a community celebration that marked the completion of San Mateo Yetla’s church in the 16th century. According to Floriano Garcia Delfín, a 60-year-old native corn farmer and keeper of the community seed bank, church documents verify the date of the church’s completion.

“The truth is I don’t know how long they've been making this recipe, but it has definitely been more than 100 years, surely 200 years,” he says. "My grandparents, who lived to be 90 years old and died 40 years ago, told us about these rituals, which they learned from their parents and grandparents. The food and rituals have been conserved over many generations. The recipe is the same as always. It hasn’t changed.”

As morning breaks on January 4, Don Pérez’s courtyard is arranged for the matanza (slaughter) and preparation of the soup. Four wooden work benches are set out within a perimeter of bamboo poles stretched between trees at head height. Several wood pyres are prepared, with plastic tables set up alongside and covered with tablecloth-sized leaves cut from nearby palm trees. Pots, pans and tools are laid out, and knives are sharpened on pocket-sized whetstones.

A team of four young men from one of the newly appointed departments approaches a pig. Three hold it down while one slides a long, thin knife blade under a front leg to pierce the heart. The animal’s death is neither quick nor

quiet, but it is executed with care and respect. Afterward, the men carry the carcass to one of the wooden benches, where the butchering process begins.

Joined by a few more coworkers of all genders, the team, now numbering eight or 10, works together to bathe the body in soapy water, rinse it clean and shave it bare with knives and razors. Sharing instructions and good-natured banter in Spanish, they drain and collect the blood in buckets. They rub cut-open orange halves over the smooth skin before making quick work of the breakdown.

One by one, the remaining pigs are dispatched and dismembered in the same fashion, each by a different departmental team: communal assets, church maintenance, municipal agency, culture and sports. Within a few hours, hog heads, haunches, rib cages and feet frame the courtyard, dangling from the bamboo perimeter poles.

Now the butchering teams turn their attention to large sheets of skin that have been peeled away from the carcasses. With newly sharpened knives, they score the fat and cut the skin into strips on the wooden benches. The cueritos (pork rinds) are deep-fried in a washing-machinesized metal pot perched over an open fire, surrounded by