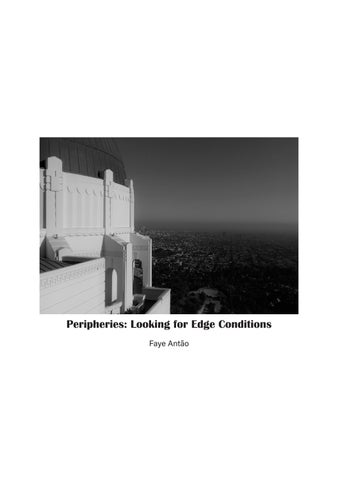

Peripheries: Looking for Edge Conditions

Abstract

Introduction

Part 1

Peripheral relations

Anthropocene conditions

Typologies

Part two

The Dual Geometries of the Los Angeles Urban Grid Exploring Edge Conditions

Looking for Suburban Spatial Thresholds

Inserting a Grid

Montage: Identifying the Edges Part Three

Abstract

This book investigates the Anthropocene’s urban periphery and its relationship with edge conditions. The first theme delves into the concept of the paradigm plan, how the dual geometries described by Mario Gandelsonas affect the urban context. The images in this project analyse Diana Agrest + Mario Gandelsonas’ paradigm plan from Los Angeles in 1985 by separating and inventorying its components, which include peripheral relations, anthropocene circumstances, and typologies. The second theme explores the edge conditions of the paradigm plan compared to the periphery site and how peripheries shape not only the boundaries of cities, but also their identity and complexity which could be obtained. It explores the relationship of creating grids within the peripheral. The last section elaborates on the notion that the grid frequently falls short of completely controlling or organising the urban landscape rather than upholding rigid order. It also implies that architectural design can find value in embracing irregularities and working within them rather than necessarily fixing or eliminating these inconsistencies.

Introduction

The idea of the peripheral in architecture and urban planning defines a spatial boundary while also suggesting the opposite, the centre which is a zone of density, influence, and gravitational attraction. One of the characteristics of modern urbanism is the spatial division between the centre and the periphery. Since the centre is where the most established physical and social networks are found, movement, infrastructure, and architectural intensity tend to concentrate there. In contrast, the periphery is typically defined by slower development, smaller density, and a feeling of physical and symbolic separation from the urban core. (Morrow and M Gamal Abdelmonem, 2013, pp.1–8)

This essay looks at how edge conditions appear in two very different urban settings: the Los Angeles Paradigm Plan, which was put forth by Mario Gandelsonas and Diana Agrest, and the planned suburban development of Newcastle's Great Park. In addition to being geographically and culturally different, these two case studies also represent divergent historical paths, urban design approaches, and planning ideologies. In order to shed light on the larger discussion of how urban boundaries can function as both a generating space and a limitation for architectural intervention, the essay will examine how each environment conceptualises and responds to the idea of the edge through these opposing lenses.

By exploring these two examples, this essay will investigate how different types of urban planning create distinct types of edges, as well as how architecture influences and responds to these situations. It will argue that edge conditions are more than merely consequences of city planning, they are essential areas that help form important areas, especially when planning systems such as grids or masterplans break the "logic". By comparing the two, a better understanding of how peripheries shape not only the boundaries of cities, but also their identity and complexity could be gained.

I will build on Gandelsonas's book, X - Urbanism: Architecture and the American City, which is divided into two parts, the first being a theoretical one at the beginning and the second which analyses American cities through the study of their planimetry. The first section is divided into seven "urban scenes" and two chapters of synthesis and reflection, all of which suggest a new interpretative framework for the Evolution of the American City. In order to demonstrate how these systems contribute to the larger patterns of urban evolution, the study's second goal is to analyse and depict the underlying geometries and spatial ordering that have influenced the form and structure of a few chosen cities. (Mora, 2005)

Part One

Peripheral Relations

Pattern

(Fig 1) Pattern - Peripheral relations , Authors own, Fine liner drawing

(Fig 2) Margins - Peripheral relations , Authors own, Fine liner drawing

The Inbetween

(Fig 3) The Inbetween - Peripheral relations , Authors own, Fine liner drawing

(Fig 4) Edge - Peripheral relations , Authors own, Fine liner drawing

Anthropocene conditions

Zones

(Fig 5) Zones - Anthropocene conditions , Authors own, Fine liner drawing

Roads/ Highways

(Fig 6) Roads/Highways - Anthropocene conditions , Authors own, Fine liner drawing

Borders

(Fig 7) Borders - Anthropocene conditions , Authors own, Fine liner drawing

Nature

(Fig 8) Nature - Anthropocene conditions , Authors own, Fine liner drawing

Typologies

Grid

(Fig 9) Grid - Anthropocene conditions , Authors own, Fine liner drawing

(Fig 10) Blocks - Anthropocene conditions , Authors own, Fine liner drawing

Part Two

The Dual Geometries of the Los Angeles Urban Grid

Mario Gandelsonas and Diana Agrest explore the distinctive American one-mile grid through their Los Angeles Paradigm Plan. The disorder that exists within Los Angeles' gridded layout, as evidenced by the patchwork of smaller grids laid on top of the main continental grid. Each city presents it's own set of difficulties and ways of being comprehended, as evidenced by various sketching and mapping methods. The Los Angeles grid system looks to be peeled back in layers, revealing how the one-mile grid interacts, overlaps, and occasionally clashes with city grids and irregular street layouts. (Gandelsonas, 1999, p.76)

Gandelsonas and Agrest both present an original technique to understanding and depicting the urban environment. His work seems to deviate from traditional architectural ways of evaluating the built environment by applying abstraction techniques such as distortions, exaggerations, and layered pictures to reveal the city as a complicated narrative. Through this deconstruction process, he urges people to observe and connect with the urban form from alternative and critical perspectives. (Grew , 2011)

Gandelsonas' use of simple black-and-white linework and geometric shapes frees both the viewer and the designer from the rigidity and formality of traditional urban design. His analytical drawings are not guided by a definite or systematic procedure but rather, they function as an exploratory process. Instead of serving as a stylistic manner of urban representation, these drawings seek to reveal distorted areas and underlying architectural conditions hidden inside the city's layered complexity. (Grew , 2011)

As a sort of infrastructural 'glue' that binds together otherwise disconnected urban fragments, this vast and seemingly endless continental grid spans the entire expanse of the megacity, unlike traditional urban grids and boulevards, which typically serve localised neighborhoods with defined boundaries. This connects distant and distinct areas like Santa Monica and downtown Los Angeles into a broader, though frequently incoherent, metropolitan fabric. This raises a central question: is the grid a meaningful link between architecture and the city, or is it simply a tool for organising space geometrically?

(Gandelsonas, 1999, p.77-78)

According to Gandelsonas, two types of geometry are at work in the Los Angeles grid. The first is 'metrical geometry', which structures the city using consistent rules, equal distances, areas, and angles which provide a clear and measurable layout. The second is 'projective geometry', which comes from images, maps, and visual representations. This second type reveals the edge conditions, the irregular or transitional spaces that stand out when reading the plan. (Gandelsonas, 1999, p.51) For Gandelsonas, architecture blends both these systems: it is a measured structure, but one that is interpreted visually.

In reflecting on the Paradigm Plan, it becomes clear that the grid serves more as an overlay than a rigid framework. It's regularity reveals the unevenness and disruptions of the landscape beneath it. Interestingly, the grid becomes architectural when it fails to impose complete order, for example, when the grid shapes and disrupts the ground rather than dominating it.(Gandelsonas, 1999, p.51) Topography, infrastructure, and historical layering disrupt the logic. In this way, the tension between architecture and urban planning creates an urban condition that is both structured and fragmented. This condition is especially noticeable on the city's outskirts.

Peripheries in Los Angeles are not clearly defined zones, but rather spatial anomalies caused by infrastructure collisions, natural terrain, and poor urban integration. These areas are frequently where freeway systems cut through neighbourhoods like where the metric grid bends over hillsides. Rather than creating smooth thresholds, these peripheries acquire spatial disruptions. These edge conditions call into question the grid's role as a logical structure demonstrating it's inability to fully resolve or integrate the city's physical intricacies. (Gandelsonas, 1999, p.51)

Furthermore, the paradigm plan's peripheral zones are more than just results of urban expansion. They are also locations of architectural and urban potential. They encourage reinterpretation, with the friction between systems, the mapped versus the built which allows for creating space for experimentation. In this way, the periphery serves as a testing ground for exploring the limitations of architectural intervention inside broad urban contexts. (Gandelsonas, 1999, p.51)

This leads to how there is also a clear contrast between how American and European cities develop. European cities grow through a solid-void structure, where buildings (solids) define streets (voids) with dense fabrics shaped by historical walls and linear pathways. In contrast, American cities like Los Angeles grow by placing individual buildings as isolated objects in a wide-open field.(Gandelsonas, 1999, p.52) In such cities, dense groupings of buildings are not the norm but rather a temporary stage brought about by moments of urban growth or densification.

Exploring edge conditions

Fragmentation vs Transition

Gandelsonas’ plan defines edge circumstances as ruptures within the urban grid caused by infrastructure, geography, or architectural factors that break the metrical order. (Gandelsonas, 1999, p.52) These are not clear boundaries, but rather fragmented zones where networks collide, for example, where freeways cut across neighbourhoods, or the imposed grid meets natural properties. These boundaries are crucial points of tension, emphasizing the disconnect between enforced urban logic and actual development. In comparison, the edge conditions here are more deliberate, gentle, and transitional. As a suburban development, Newcastle Great Park clearly distinguishes between built-up residential zones and the adjacent open countryside. These margins are purposefully created as buffers, often landscaped or infrastructural, indicating a transition from suburb to rural without the friction observed in Los Angeles. There are less sudden changes or contradictory features, and the transitions between various spatial zones are clearly smoother and more gradual, making the urban experience more cohesive and unified.

Grids and Spatial Integration

As mentioned in the first part, the Los Angeles plan's grid functions as an overlay, revealing and seeking to fully consume the urban fabric. It's disintegration at the edges creates architectural interest and urban meaning. Edges are where these projective and metric geometries collide, making them dynamic and analytically interesting. However, the suburb adheres to more traditional European design ideas, like cul-de-sacs and house clusters. Its layout is not grid-based, and the edge conditions serve as development boundaries rather than spatial negotiation points. These boundaries are concerned with containment and transition between land-use zones, rather than architectural friction.

Threshold and Borders

According to Mario Gandelsonas' paradigm, the edge is a threshold, a location where transition occurs, one system gives way to another, and complexity is most apparent. These are fruitful places for exploration and shift. In the suburbs of Newcastle Great Park, the edge serves as a barrier, defining control, design goal, and spatial order. It is about the separation of spaces and not transformation. In Newcastle's Great Park suburban area, however, the edge serves more as a barrier. It clearly separates one space from another and is intended to demonstrate control, order, and a completed plan. Instead, than offering a space for change or new ideas, the edge in this case serves to complete the design and keep everything neat and divided, rather than inviting transformation or interaction.

One of the main aspects where the American plan compares to the periphery suburb is the relationship between plan and buildings and between the buildings themselves. In Los Angeles, it seems the structures don’t relate to the plan and tend to be independent from each other even when they form a street wall. However, the extruded local urban fabric is reinforced by features such as strong horizontal cornices. European streets seem to have mediating roles whilst with American cities, the “main street” is dominant public space.(Gandelsonas, 1999, p.45) European streets tend to become spaces because of typological uniformity of street walls. Opposingly, in America they read as voids that suture the separation between blocks, they represent a split. (Gandelsonas, 1999, p.45)

The vertical dimension and the sequential notion of time are eliminated in the Los Angeles plan, which then showcases the metropolis as solids and voids in two dimensions. It is framed by a reading mechanism that penetrates "the unlimited perceptual surface" of the X-Urban metropolis and permits admission into the urban text. (Gandelsonas, 1998, p.138)

"It is in the space where these two levels are reconciled that architecture finds the site for its articulation with the city, the site where architecture can produce changes that inscribe permanent traces in the urban realm" (Gandelsonas, 1998, p.137)

Looking for Suburban Spatial Thresholds

Fences

Typological - Commercial + Agricultural

13) Fabric changes , Authors own, Site photograph

Fabric changes

(Fig 14) Typological- residential + agricultural , Authors own, Site photograph

Typological - Residential + Agricultural

Change in Surface

Roads

(Fig 19) Boundaries, Authors own, Site photograph

Boundaries

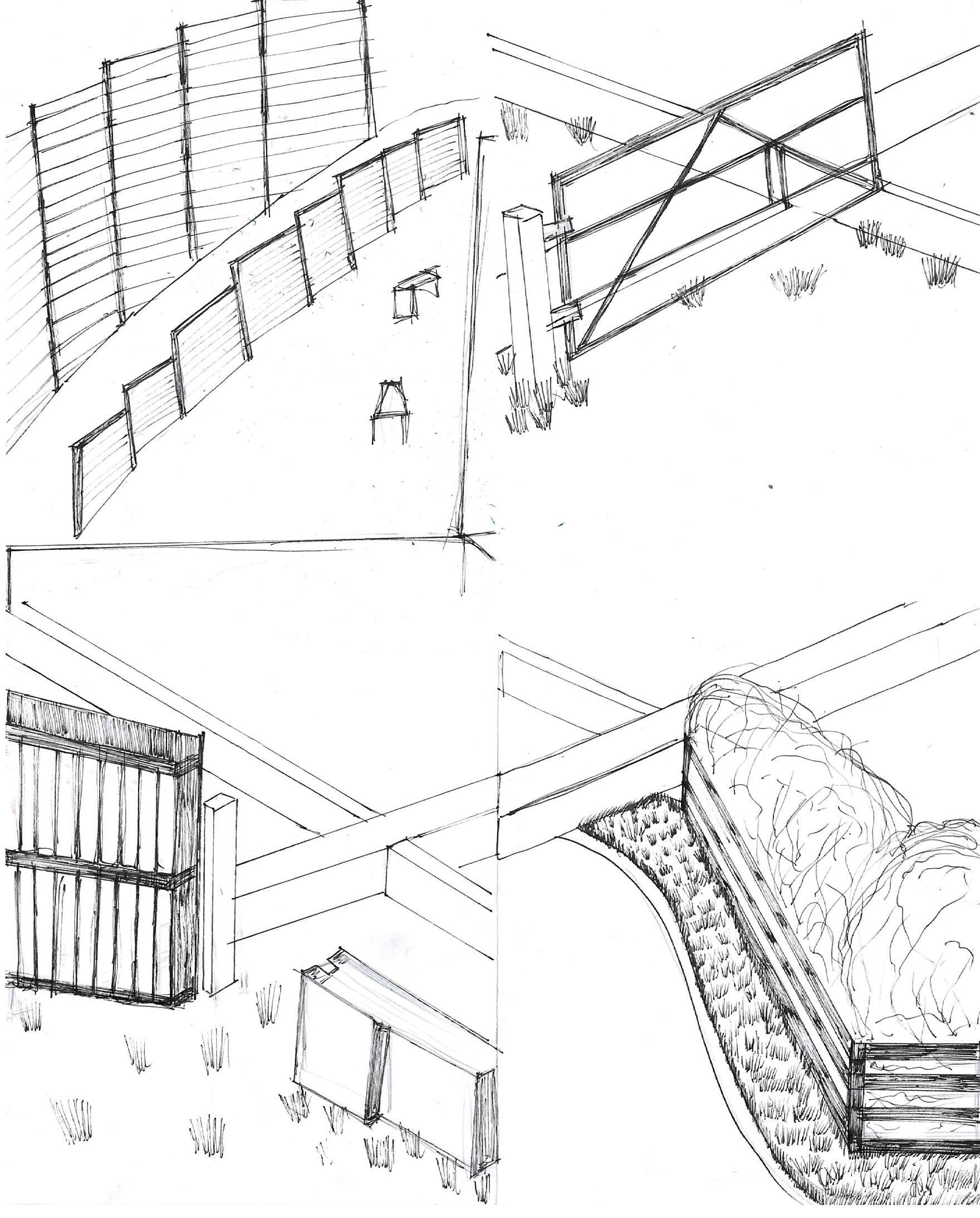

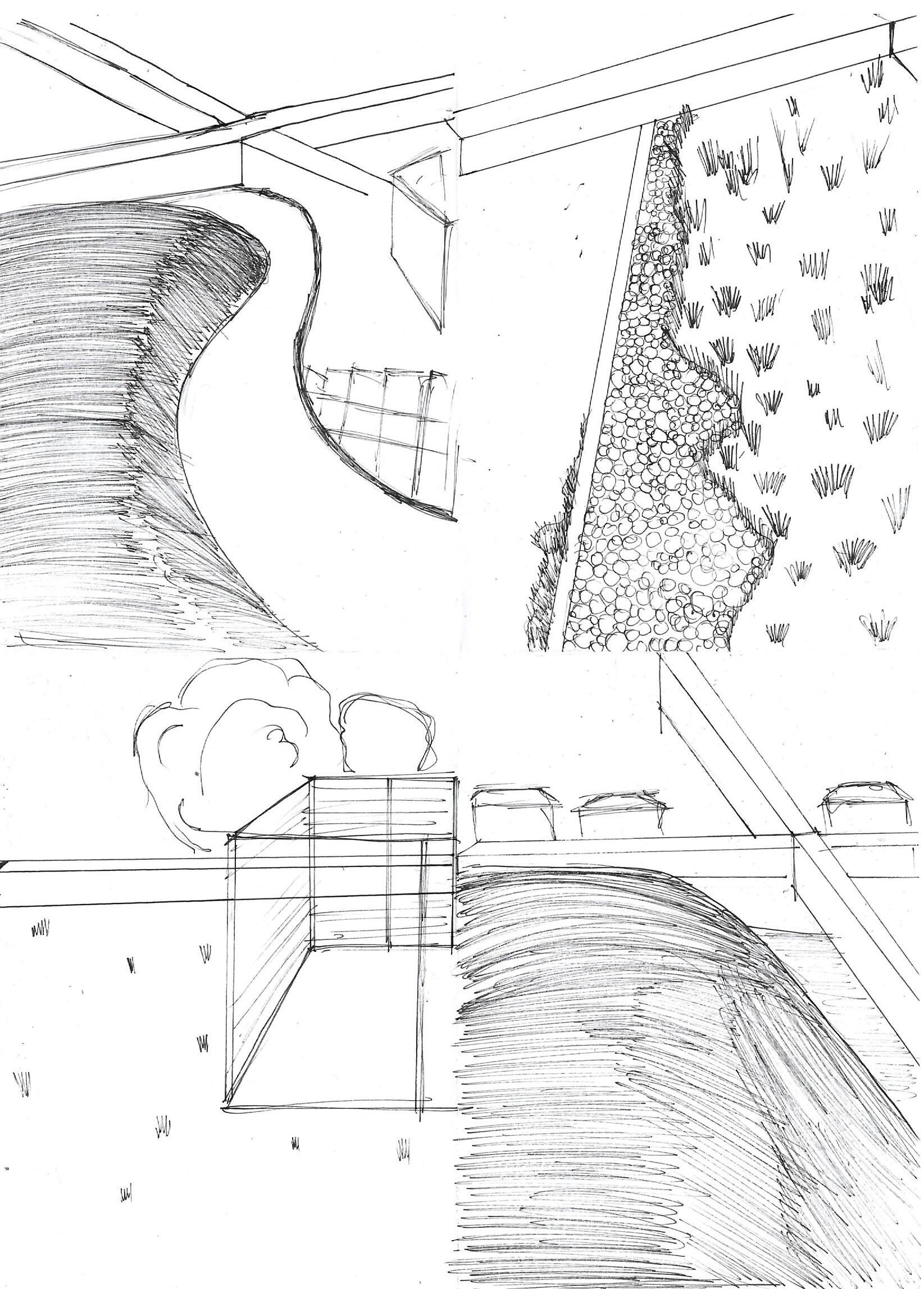

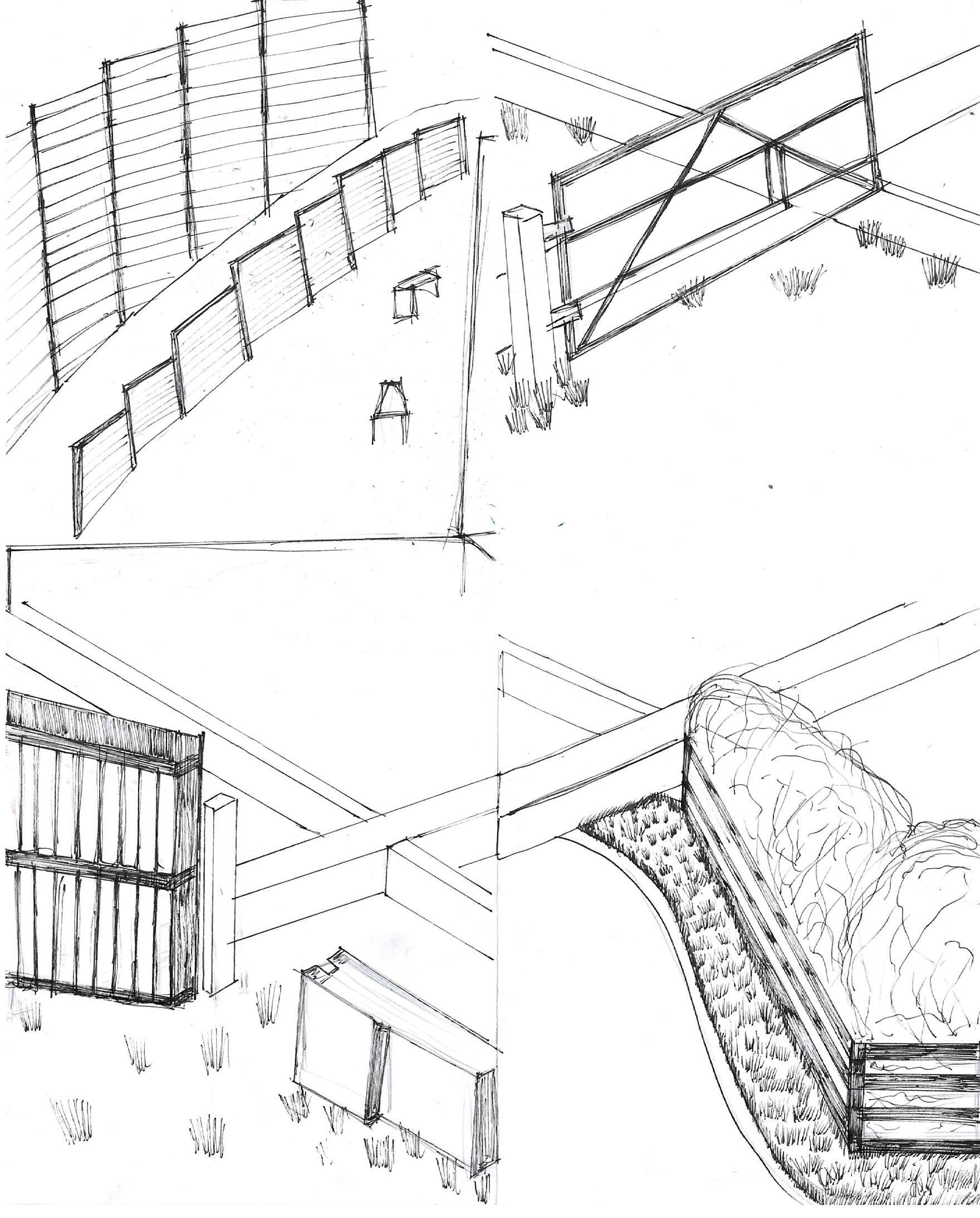

Inserting a grid

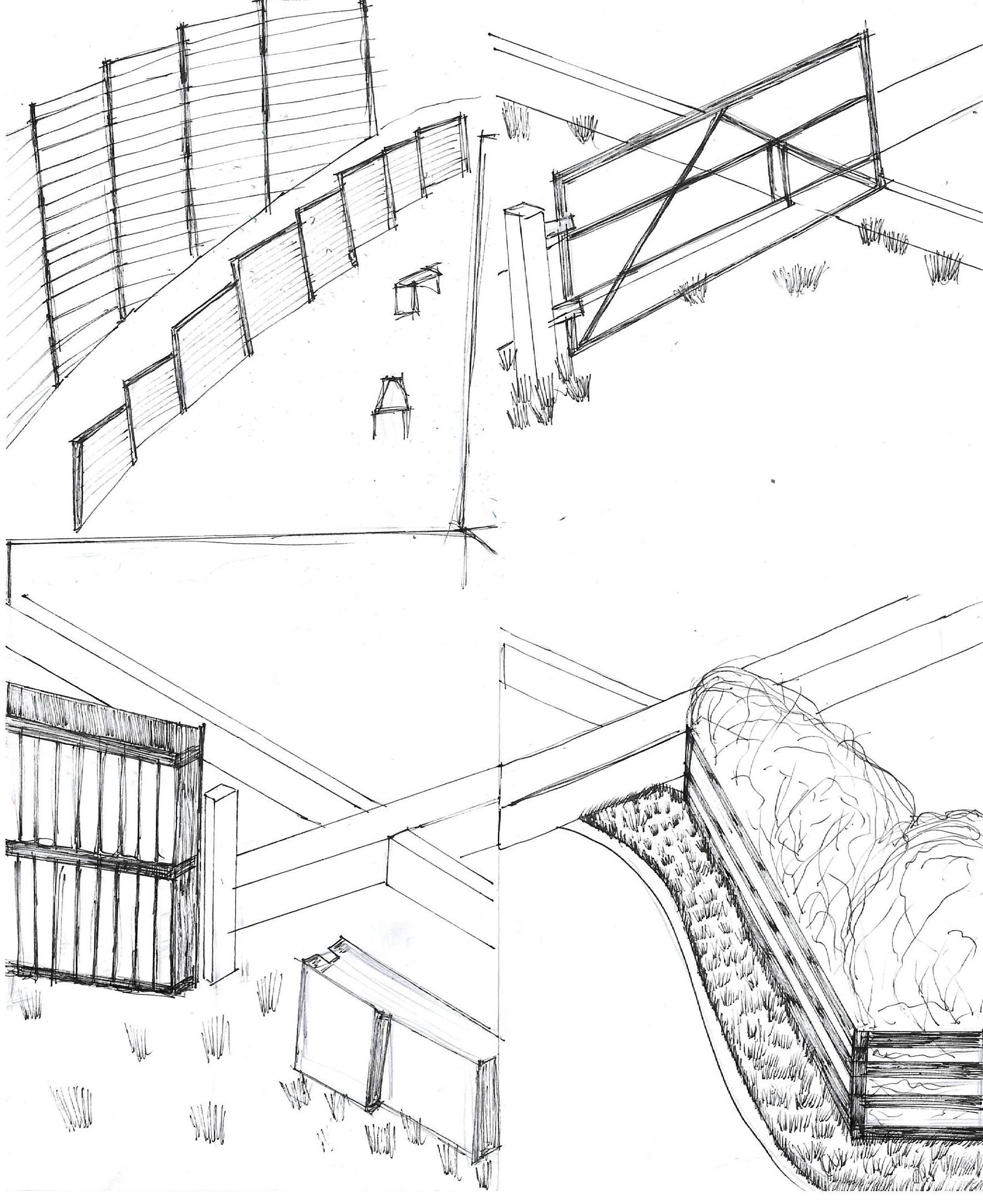

The following suite of drawings showcases the suburban setting in Newcastle which is photographed and then layered with a hand drawn three-dimensional grid interpretation. This approach enables a spatial analysis that places the grid’s rigid logic within the existing environment’s irregularities. The drawings provide a analytical perspective on the relationship between architectural order and suburban form by examining the tensions and alignments between imposed geometric systems and the site’s physical conditions through the volumetric embedding of the grid.

(Fig 20) Fences- Inserting a grid , Authors own, Fine liner drawing

(Fig 21) Typological- Commericial + agricultural - Inserting a grid , Authors own, Fine liner drawing

(Fig 22) Fabric changes - Inserting a grid , Authors own, Fine liner drawing

(Fig 23) Typological- residential + agricultural - Inserting a grid , Authors own, Fine liner drawing

(Fig 24) Chage in surface - Inserting a grid , Authors own, Fine liner drawing

(Fig 25) Hedges - Inserting a grid , Authors own, Fine liner drawing

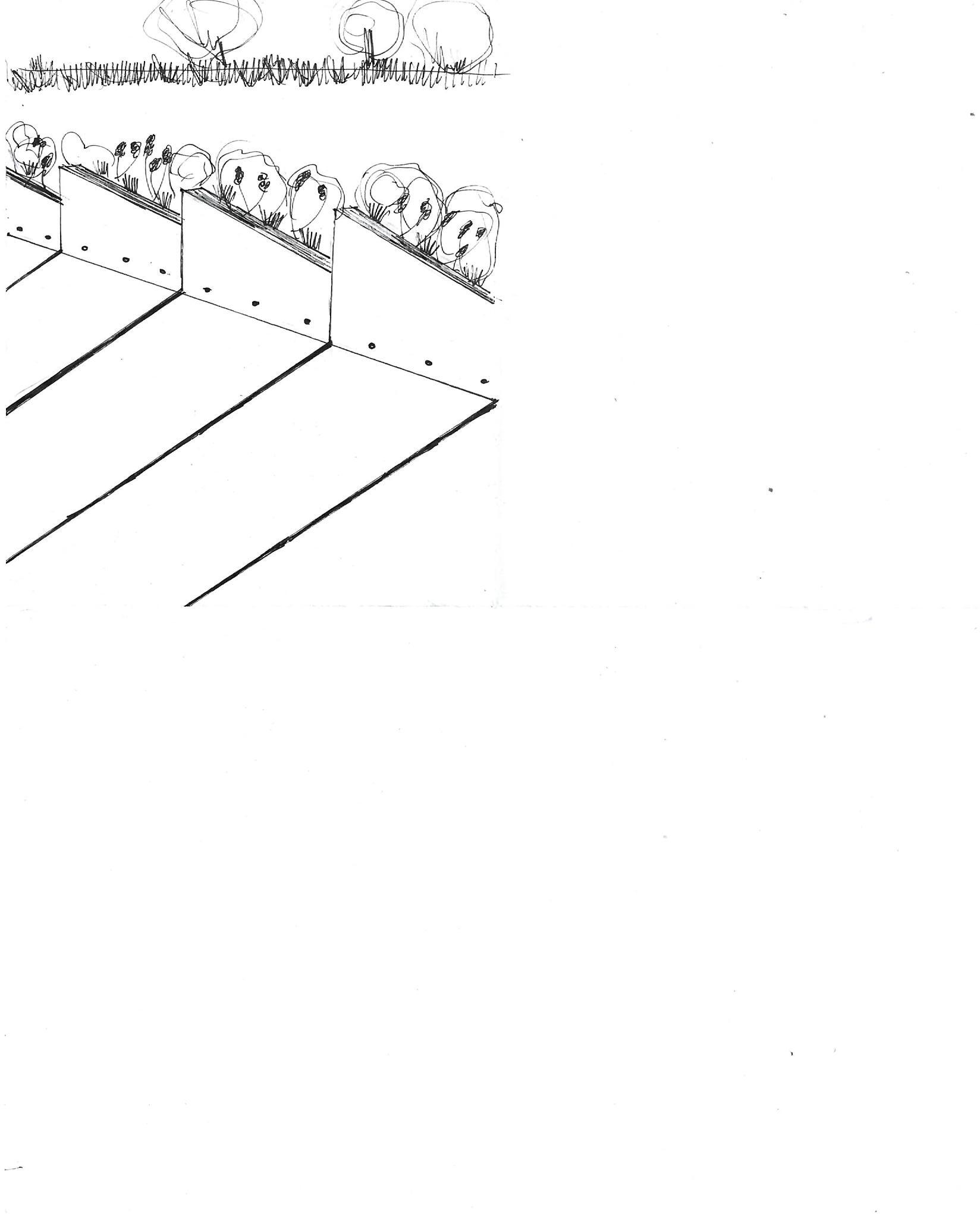

(Fig 26) Roads - Identifying the edges , Authors own, Fine liner drawing

(Fig 27) Zones- Identifying the edges , Authors own, Fine liner drawing

(Fig 28) Boundaries - Identifying the edges , Authors own, Fine liner drawing

the Edges

Using many city grids as interlocking puzzle pieces that hovers above the actual plan, separate edges are created for distinct city plans. When these grids are joined into colossal city fabrics, they create a dynamic composition with things arranged at various angles. The underlying plan acts as a unified "glue," connecting these different urban qualities. This approach allows for a combination of structure and randomness, resulting in a layered, layered cityscape.

Newcastle suburb periphery collage inspired by The Los Angeles Megacity plan by Mario Gandelsonas.