5 | ISSUE 1 FALL 2024

5 | ISSUE 1 FALL 2024

The privilege we enjoy, particularly in the United States, to attend church and to worship freely without fear of persecution is a gift of liberty that we often take too much for granted. For simply worshiping Christ, many of our global brothers and sisters face immense persecution and even

Westminster Magazine appears amid America’s election season. Its focus is not only on the privilege the church has to worship without fear of persecution but also on the honor believers in Christ have as public witnesses, serving as salt and light on behalf of our Lord Jesus Christ.

Our theology, which we hold in our hearts and share with family and the church, is a vital aspect of our impact on our communities and even our nation. Whether we label it Christian witness, public theology, or cultural impact, it is our duty and wonderful calling to proclaim and advance the kingdom of Christ through each of our God-given gifts.

Thank you for helping Westminster let its light shine before men by supporting our efforts to proclaim the truth of the gospel. Westminster’s motto is “the whole counsel of God,” which is at the heart of our understanding of a biblical worldview. Your prayerful support and encouragement, as well as your studying with us and sending students to us, are working together to help Westminster be a beacon of truth for the kingdom of Christ. Your prayerful investments in our work enable us to train the next generation of leaders for Christ’s global church.

May our lights shine into a world of darkness so that all the peoples of the earth may see the hope of Christ to the glory of God our Father. Thank you for reading our magazine!

In His service,

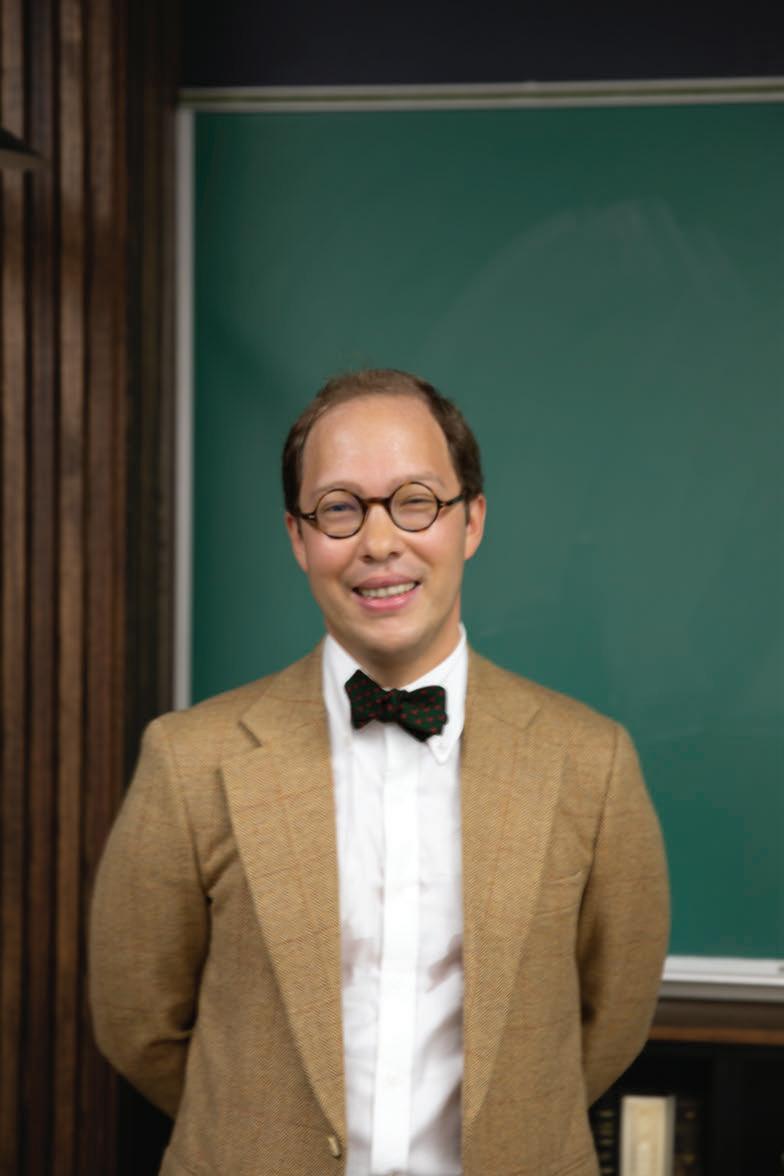

Peter A. Lillback, President

Volume 5 | Issue 1 | Fall 2024

Editor–in–Chief

Peter A. Lillback

Executive Editor

Jerry Timmis

Managing Editor

Nathan Nocchi

Senior Writer

Pierce Taylor Hibbs

Associate Editor

Anna Sylvestre

Archival Editor

B.McLean Smith

Design

Ethan Greb

Interior

Angela Messinger

Read, watch, and listen at wm.wts.edu.

WestminsterMagazineaccepts pitches and submissions of previously unpublished work. For more information, email wtsmag@wts.edu.

WestminsterMagazineis published twice annually by Westminster Theological Seminary, 2960 Church Road, Glenside, Pennsylvania 19038. No part of this publication may be reproduced without permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations.

Printed and bound in the United States of America

Cover art: John Lewis Krimmel (1787–1821), Election Day in Philadelphia 1815

“Is or ever was the United States a Christian nation?”

Well, what do you mean? Do you mean by “nation” a national government explicitly endorsed or established by Christianity? Or do you mean by “nation” a people overwhelmingly adhering to Christianity?

In 1776, the latter was obviously true, but more people are probably interested in the former. Secularists will

appeal to John Adams’s execution of the Treaty of Tripoli, which states, “As the government of the United States of America is not in any sense founded on the Christian Religion…” This, they say, is proof that the United States is not now, nor ever was, a Christian nation.

More to come on the Treaty of Tripoli. But first, is that even an appropriate way to ask the question? The United States as a “nation” can imply many things,

including our government under the federal Constitution, which itself makes no explicit endorsement or establishment of Christianity. But the United States, as a nation, is first and foremost composed of united sovereign states, most of whom had established systems of sovereign government in a constitution prior to the ratification of the federal Constitution.

In discerning a more meaningful answer to the question of original Christian government, we should not ask, “WAS the United States a Christian nation?” We should instead ask, “WERE the united States Christian states?” Understood and asked this way, the question leaves no doubt. Let’s look at the state constitutions of the original thirteen.

Delaware—1776—On legislators’ required oath of office: Delaware is explicitly Christian, requiring an oath or affirmation of faith in the Trinity and acknowledging the divine inspiration of Holy Scripture—both the Old and New Testaments. Article 22 reads, “I, A B. do profess faith in God the Father, and in Jesus Christ His only Son, and in the Holy Ghost, one God, blessed for evermore; and I do acknowledge the holy scriptures of the Old and New Testament to be given by divine inspiration.”

Pennsylvania—1776—On legislators’ required oath of office: Similar to Delaware, Pennsylvania requires an oath unto God (although leaving out the trinitarian formula) and the acknowledgement of the divine nature of Holy Scripture. Pennsylvania uniquely affirms God as the consummate governor, reminding lawmakers of their due submission unto him and his word. Section 10 reads, “I do believe in one God, the creator and governor of the universe, the rewarder of the good and the punisher of the wicked. And I do acknowledge the Scriptures of the Old and New Testament to be given by Divine inspiration.”

New Jersey—1776—On qualifications for legislative office: New Jersey goes a step beyond Pennsylvania, requiring not simply a profession of faith in God as part of the universal church, but more specifically a belief in any Protestant sect, in order to meet the requirements for public office, as well as to be protected in their civil rights. Article 19 reads,

[T]here shall be no establishment of any one religious sect in this Province, in preference to another; and that no Protestant inhabitant of this Colony shall be denied the enjoyment of any civil right, merely on account of his religious principles; but

that all persons, professing a belief in the faith of any Protestant sect who shall demean themselves peaceably under the government, as hereby established, shall be capable of being elected into any office of profit or trust, or being a member of either branch of the Legislature, and shall fully and freely enjoy every privilege and immunity, enjoyed by others their fellow subjects.

Georgia—1777—On qualifications for legislative office: Georgia, too, explicitly required Christian Protestantism as a staple for public office. Article 6 states, “The representatives… shall be of the Protestent religion, and of the age of twenty-one years, and shall be possessed in their own right of two hundred and fifty acres of land, or some property to the amount of two hundred and fifty pounds.”

Connecticut—1818—On preference of worship and civil rights: Connecticut guarantees religious liberty for “any christian sect,” and guarantees equal rights, powers, and privileges for “each and every society or denomination of christians.” But it does not guarantee religious liberty, nor even equal rights and treatment, to non-Christians in the state. Article 1.4 reads, “No preference shall be given by law to any christian sect or mode of worship.” And Article 7.1 says, “each and every society or denomination of christians in this state, shall have and enjoy the same and equal powers, rights and privileges.”

Massachusetts—1780—On religious rights: Like Connecticut, Massachusetts establishes equal protection of the law only for denominations of Christians. Likewise, those who did not profess Christianity were disqualified from public office. Part 1, Article 3 states, “every denomination of Christians, demeaning themselves peaceably, and as good subjects of the commonwealth, shall be equally under the protection of the law: and no subordination of any one sect or denomination to another shall ever be established by law.” Part 2, Chapter 2, Article 2 declares, “no person shall be eligible to this office [of governor]…unless he shall declare himself to be of the Christian religion.” Lastly, Part 2, Chapter 6, Article 1 proclaims, “Any person chosen governor, lieutenant-governor, councillor, senator, or representative…shall…make and subscribe the following declaration, viz.: ‘I, A.B., do declare that I believe in the Christian religion, and have a firm persuasion of its truth…”

Maryland—1776—On religious liberty: Though historically Roman Catholic in culture, the state of Maryland generalized its protection of religious liberty to those “professing the Christian religion,” but did not grant that same protection to those who did not make the same profession. Declaration of Rights, 33 reads, “That, as it is the duty of every man to worship God in such manner as he thinks most acceptable to him; all persons, professing the Christian religion, are equally entitled to protection in their religious liberty… the Legislature may, in their discretion, lay a general and equal tax for the support of the Christian religion.”

Our national mindset has fundamentally shifted away from the founding philosophies in so many ways …

South Carolina—1778—On the establishment of a religion: South Carolina is as explicitly Christian as any of the original states. The introduction below speaks for itself, but the entire resolution in Article 38 is even more prescriptive in its state Christianity. Article 38 declares, “[A]ll persons and religious societies who acknowledge that there is one God, and a future state of rewards and punishments, and that God is publicly to be worshipped, shall be freely tolerated. The Christian Protestant religion shall be deemed, and is hereby constituted and declared to be, the established religion of this State. That all denominations of Christian Protestants in this State, demeaning themselves peaceably and faithfully, shall enjoy equal religious and civil privileges.”

New Hampshire—1792—On the support of religion for the security of government: New Hampshire again sponsors equal protection of the law, but only for denominations of Christians. New Hampshire also grounds its civil and moral philosophies on evangelical [i.e., gospel] principles, and authorizes the legislature publicly to support only “protestant teachers of piety, religion and morality.” Article 6 states,

As morality and piety, rightly grounded on evangelical principles, will give the best and greatest security to government, and will lay in the hearts of men the strongest obligations to due subjection; and as a knowledge of these is most likely to be propagated through a society by the institution of the public worship of the Deity, and of public instruction in morality and religion; therefore, to promote those important purposes the people of this State have a right to empower, and do hereby fully empower, the legislature to authorize, from time to time, the several towns, parishes, bodies corporate, or religious societies within this State, to make adequate provisions, at their own expense, for the support and maintenance of public protestant teachers of piety, religion, and morality… [E]very denomination of Christians, demeaning themselves quietly and as good subjects of the State, shall be equally under the protection of the law.

New Hampshire is explicitly Protestant Christian and evangelical (Christian gospel), and it does not authorize the legislature to support non-Christian religions.

Virginia—1776—On religious liberty: Virginia is the first state on our list (in state order) that does not explicitly make itself a Christian state. While it does apply an obligation of religion to “our Creator,” it also goes out of its way to place “reason and conviction” and “the dictates of conscience” as the governors of that duty. One can infer an implicit call to Christianity at best in the Declaration of Rights. Section 16 reads, “it is the mutual duty of all to practice Christian forbearance, love, and charity towards each other.” We can conclude that this was not explicitly Christian.

New York—1776—On religious liberty: Similar to Virginia, New York protects religious liberty, while never calling for a Christian preference in worship or establishment. It does briefly allude to traditionally Christian virtues, but also calls the state to guard against “the bigotry of weak and wicked priests,” and calls Christian preference “repugnant to this constitution.” New York was explicitly not a Christian state. Article 38 reads, “this convention doth further, in the name and by the authority of the good people of this State, ordain, determine, and declare, that the free exercise and enjoyment of religious profession and worship, without discrimination or preference, shall forever hereafter be allowed, within

this State, to all mankind: Provided, That the liberty of conscience, hereby granted, shall not be so construed as to excuse acts of licentiousness, or justify practices inconsistent with the peace or safety of this State.”

North Carolina—1776—On qualifications for office: While not as explicitly establishmentarian as her Southern Sister, North Carolina similarly holds Protestant Christianity in legal preference, requiring its affirmation for public office. Article 32 states, “That no person, who shall deny the being of God or the truth of the Protestant religion, or the divine authority either of the Old or New Testaments, or who shall hold religious principles incompatible with the freedom and safety of the State, shall be capable of holding any office or place of trust or profit in the civil department within this State.”

Rhode Island—1843—On religious liberty: Rhode Island, our thirteenth state, is a strange case, since it didn’t formally adopt a constitution until 1843. Their charter of 1663 is explicitly Christian, and they were technically governed by this charter even after independence in 1776, but it is questionable whether that religious governance was in practice or in name only. In its 1843 constitution, it turned decidedly a-Christian, requiring no religious test for public office, and speaking only of a general God, rather than a Christian or Protestant God. Article 1.3, Section 3 states,

We, therefore, declare that no man shall be compelled to frequent or to support any religious worship, place, or ministry whatever, except in fulfillment of his own voluntary contract; nor enforced, restrained, molested, or burdened in his body or goods; nor disqualified from holding any office; nor otherwise suffer on account of his religious belief; and that every man shall be free to worship God according to the dictates of his own conscience, and to profess and by argument to maintain his opinion in matters of religion; and that the same shall in no wise diminish, enlarge, or affect his civil capacity.

So, of the thirteen original states to ratify the Constitution, ten states were indisputably and explicitly Christian states either at the time of ratification, or shortly thereafter. Hypothetically, had they bullied their position, they as states could have amended the federal Constitution to provide equal protection only to

Christians, and required adherence to Christianity as a qualification for office.

So, what was the Treaty of Tripoli talking about, asserting that the government of the United States of America is not in any sense founded on the Christian religion?

Quite simply, this treaty, being concerned with trade via a Muslim country, is asserting at face value that the federal mechanisms for enforcing international treaties are agnostic to religion and thereby not inimical to Islam. The full context of the statement, not often quoted, shows it as simply a preamble for what’s really important to Adams: the potential interruption of trade. Note the language.

As the government of the United States of America is not in any sense founded on the Christian Religion—as it has in itself no character of enmity against the laws, religion or tranquility of Musselmen [Muslims],—and as the said States never have entered into any war or act of hostility against any Mehomitan [Islamic] nation, it is declared by the parties that no pretext arising from religious opinions shall ever produce an interruption of the harmony existing between the two countries.

Notice that when it comes to the individual states, it emphatically does NOT assert their governments are not founded on the Christian religion (which would be a lie). It only asserts that the states have not entered into any war or act of hostility with Islamic nations (which was true).

It should be noted also, that after the admission of Vermont as the 14th state in 1791, the “Christian” language more and more was left out of official state constitutions. But when asking the question, “Were the United States founded as Christian states?” it’s clear that a veto-proof majority absolutely were.

In 1789, the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America adopted the Westminster Confession of Faith as its doctrinal standard. But there seemed to

be a problem. The 1646 version of Chapter 23 had some pretty un-republican language:

The civil magistrate may not assume to himself the administration of the Word and sacraments, or the power of the keys of the kingdom of heaven: yet he hath authority, and it is his duty, to take order, that unity and peace be preserved in the Church, that the truth of God be kept pure and entire; that all blasphemies and heresies be suppressed; all corruptions and abuses in worship and discipline prevented or reformed; and all the ordinances of God duly settled, administrated, and observed. For the better effecting whereof, he hath power to call synods, to be present at them, and to provide that whatsoever is transacted in them be according to the mind of God.

With no monarch installed as a “Defender of the Faith,” as there was in England, this didn’t make as much sense to the American church. The new 1789 language no longer treats the civil magistrate as a singular, but rather as many.

Civil magistrates may not assume to themselves the administration of the Word and sacraments; or the power of the keys of the kingdom of heaven; or, in the least, interfere in matters of faith.

However, it does still maintain its expectations of the civil magistrates to protect religion—not just general religion, but specifically the Christian religion. Presbyterians, despite this new republican sentiment, emphatically did not expect the civil magistrates to protect all religions the same way they were expected to protect Christianity:

Yet, as nursing fathers, it is the duty of civil magistrates to protect the church of our common Lord, without giving the preference to any denomination of Christians above the rest, in such a manner that all ecclesiastical [i.e., of the Christian church] persons whatever shall enjoy the full, free, and unquestioned liberty of discharging every part of their sacred functions, without violence or danger. And, as Jesus Christ hath appointed a regular government

and discipline in his church, no law of any commonwealth should interfere with, let, or hinder, the due exercise thereof [i.e., Jesus’s Church], among the voluntary members of any denomination of Christians, according to their own profession and belief. It is the duty of civil magistrates to protect the person and good name of all their people, in such an effectual manner as that no person be suffered, either upon pretense of religion or of infidelity, to offer any indignity, violence, abuse, or injury to any other person whatsoever and to take order, that all religious and ecclesiastical [i.e., of the Christian church] assemblies be held without molestation or disturbance.

This is important because the Presbyterians, perhaps more so than any other demographic, were crucial in the advancement of the political rebellion against tyranny. The tyrant himself, according to many, considered the rebellion to be “a Presbyterian War.” Presbyterians were not just influential in matters of religion, but they also helped build these Christian states and demanded Christian preference in their civil and religious constitutions.

Whatever one might think or feel about the wisdom of these state constitutions is a completely different question. Our national mindset has fundamentally shifted away from the founding philosophies in so many ways: theology, anthropology, legal philosophy, social theories, economics, and teleology. (I am tempted to blame Kant for all of it.) One may even agree with these shifts to any manner of degree, especially as it concerns the conversation about church and state. But when appealing to the origins, it would be ignorant or deceitful to imply our united States were not overwhelmingly built as Christian systems of government.

Andrew Schwartz is the Senior Director of Stewardship at Westminster Theological Seminary and a Ruling Elder in the PCA. He is also an Early American Historian out of Old Dominion University, currently living with his wife and four children in the Pocono Mountains of Pennsylvania.

“Aided by the Spirit and empowered by the gospel, may we live as faithful citizens of the city of God in the midst of the city of man. The Church needs to respond now by equipping culture-shaping Christians for the marketplace and the public square.”

Robert J. Pacienza, DMin, Westminster Theological Seminary President and Founder, Institute for Faith and Culture

“And if Christ is Lord of lords and King of kings, if he is really the Ruler among the nations, then all nations are in a higher sense one nation, under one King, one law, having one interest and one end. There cannot be two laws for Christians—one to govern the relations of individuals, and the other the relations of nations. I charge you, citizens of the United States, afloat on your wide wild sea of politics, There is another King, One Jesus: the safety of the state can be secured only in the way of humble and whole-souled loyalty to His Person and of obedience to His Law.”

—A.A. Hodge

The French essayist Joseph Joubert once quipped that “it is better to debate a question without settling it than to settle a question without debating it.” One should say further that this is considerably more important when questions of the greatest importance are in view, even if it is those questions that cause the greatest controversy. In our mercurial world, one of these contentious questions is that of the relationship between Christianity and politics, between religion and the state. This particular question is hardly new. From Constantine to Charlemagne, from the Peace of Augsburg to the Peace of Westphalia, and from political theorists such as John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and John Stuart Mill, the relationship between religion and the state has been a prominent issue. Some argued that religion should be sequestered to one’s private life. Others, such as Ludwig Feuerbach, argued that religion is “the only practical and successful vehicle for politics.” The question has been, likewise, explored in our American context. The competing interests of the ministers of Massachusetts Bay and Roger Williams in the seventeenth century, or the nineteenth-century debate between the so-called “Amendmentists,” namely the National Reform Association and the Liberal League, are examples of this question.

In the last three years, there has been, in no uncertain terms, an interest in retrieving an older theological heritage, a “Reformed statecraft.” The buzzwords associated with this retrieval are ‘Christian Nationalism’ and ‘Establishmentarianism,’ with the latter generally being a theological constituent part of the former. The former has become so broadly defined that it is arguably an unhelpful appellation. For instance, in Ross Douthat’s recent New York Times article, he identifies four ways in which the term Christian Nationalism is employed. This has led to poor argumentation, and as Charles Dickens

once said, “If the defendant be a man of straw, who is to pay the costs?” There is, therefore, cause to consider what these terms mean so as to encourage greater understanding about the current political and theological discourse. For our purposes in this brief article, we shall not explore the question of nationalism, though the issue is not foreign to our modern Reformed tradition. Geerhardus Vos spoke positively of nationalism, saying that “nationalism, within proper limits, has the divine sanction,” and that “attempt[s] at world-power” are against “the voice of prophecy,” not only “as is sometimes assumed, because it threatens Israel, but for the far more principal reason, that the whole idea is pagan and immoral.” We shall, rather, explore that which is more obviously aligned with a Reformed statecraft, namely, establishmentarianism.

When human autonomy is coupled with a vague “pursuit of happiness,” society will inexorably tend toward chaos.

In Reformed Presbyterian circles, there has been a notable reticence to return to the question of church and state ever since the debates over theonomy in the 1970s through the 1990s. However, for the sake of clarity and Christian witness, we must thoughtfully and charitably explore the issue. The obvious reason that this is required is that, in the midst of the culture war, commentators have signaled that “the nation is awash in religiosity,” as an op-ed in the New York Times put it. Perhaps, one might say, with a Jeffersonian spirit, that there is a deep concern about religious values coming to bear on the goings-on of the political sphere. For example, Linda Greenhouse recently asserted in her New York Times article on the Alabama Supreme Court ruling that the country is now coming to a greater realization of “the peril of the theocratic future toward which the country has been hurtling.” The task before us is thus a foray into an issue that is politically charged, debated vigorously within the church, and ambiguous in its terms. But it is, at the same time, an inquiry into that which is “true, honorable, and just” (Phil. 4:8).

What is ‘Establishmentarianism’? In plain terms, it is the teaching that the civil magistrate should recognize “God, the supreme Lord and King of all the world” (WCF 23.1). This involves the magistrate supporting and fostering the visible church within its geographical jurisdiction for the promotion of true religion. On this view, there are two errors that are to be avoided. First is the Erastian error, which arises when the civil magistrate acts beyond the power corresponding to his magistracy. For example, the civil magistrate “may not assume to themselves the administration of the Word and sacraments; or the power of the keys of the kingdom of heaven; or, in the least, interfere in matters of faith” (WCF 23.3). Second is the error of Rome, which is where the church unduly superintends upon the civil magistrate, usurping its ordained authority, and consequently hinders its function. In contradistinction to these views, the church and state are argued to be coordinate powers, and, as such, have unique proximate ends that notwithstanding, by virtue of their coordination, coincide in their ultimate ends. The civil magistrate is, “as [a] nursing father…” and is to “protect the church of our common Lord” (WCF 23.3), and thereby “countenance and maintain” the church (WLC, Q.191).

A significant majority of 16th and 17th-century Reformers have articulated and defended this understanding of the divinely sanctioned duties of the civil magistrate. One of the chief passages in their argumentation was Romans 13:1–4, which reads,

Let every person be subject to the governing authorities. For there is no authority except from God, and those that exist have been instituted by God. Therefore whoever resists the authorities resists what God has appointed, and those who resist will incur judgment. For rulers are not a terror to good conduct, but to bad. Would you have no fear of the one who is in authority? Then do what is good, and you will receive his approval, for he is God’s servant for your good. But if you do wrong, be afraid, for he does not bear the sword in vain. For he is the servant

[διάκονός] of God, an avenger who carries out God’s wrath on the wrongdoer. (Emphasis added)

In seventeenth-century England, divines such as Anthony Burgess argued that Romans 13 is “the Magistrate’s Magna Charta…his Commission sealed from

heaven, whereby he may be encouraged to goe through his office, [which is] his Calling of God, who hath a peculiar providence over such.” It is vital that the magistrate recognizes this, for just as “the eclipse of the Sun makes a great deale of motion and alteration in things below, so any eclipse in those that are in Authoritie and Government workes great but sad effects in inferiours.” Thus, when civil magistrates do not readily consult that which “God and his Word speaketh,” but follow instead “maximes and principles of State,” there will be ramifications for the subjects of that kingdom or nation. A coherent two-fold polity requires both the church’s prophetic witness and the magistrates’ enforcement of the law.

One might say that it is only natural that English theologians held such views. After all, the Protestant church in England was, at the outset, connected to the Crown. However, should one sail across the English Channel to the Continent, they would find figures such as Petrus Van Mastricht, Franciscus Junius, and Francisco Turretini, all of whom proffered similar arguments. Van Mastricht, who is worth quoting at length, says,

Magistrates, who should know theology and should have the law before their eyes (Deut. 17:18–20; Josh. 1:8; Psalm 19), prescribe it for their subordinates (2 Chron. 17:7–9; Josh. 24:14), protect it against enemies, as nursing fathers of the church (Isa. 49:23; 60:16), and as guardians of both tables of the law, propagate it (Gen 18:19). In sum, they should, in all ways, kiss Christ (Ps. 2:10–12), so that their polity becomes a theocracy, that is, a Christocracy

Countless other theologians from the 16th and 17th centuries could be referenced to support the notion of establishment, including 17th-century American theologians. It is, however, not merely individuals who can be cited, but consensus documents, namely confessions, which codified this idea. Indeed, one can point to many confessions of the period, including the Westminster Standards, the Second Helvetic Confession, the Belgic Confession, and the Thirty-Nine Articles. At least one reason why arguments for establishment were so prevalent is because of a principle that was fundamental to the Reformation itself: the word of God regulates all of life. All human life was argued to be under the authority of Scripture. Thus, when it was seen that the Scriptures note particular duties and articulate an ideal for kings, emperors,

and magistrates, whom the Reformers understood to be public persons, these were thought to have an obligation and duty to abide by the moral law and refrain from acting, either privately or publicly, in such a way that contravenes that law. Scripture states that “it is an abomination to kings to commit wickedness: For the throne is established by righteousness” (Prov. 16:12). Indeed, the Lord is the keeper of the city (Ps. 127:1), and should that city not honor him, it “shall be utterly wasted” (Isa. 60:12). As Edward Reynolds wrote, “It would infinitely conduce to the peace of the Church and State, to the honour of Religion and justice, and to the avoiding of envy or scandal, if every person…would regulate all his demeanours and administrations with a Quid requisivit, [namely] what is it that God would have me to do?”

One need only be half-cognizant to see, however, that the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries are markedly different politically than, say, America is today. But, at the same time, it must be said that the Puritans of England became, as it were, the Puritans of New England. As the English poet George Herbert said, “Religion stands on tip-toe in our land / Readie to passe to the American strand.” The Mayflower Compact (1620) says that their efforts were “for the glory of God, and advancement of the Christian faith ... [to] covenant and combine ourselves together into a civil body politic, for our better ordering and preservation and furtherance of the ends aforesaid…” This sentiment was later echoed by others, such as theologian John Cotton (1585–1652), who said that “these plantations be planted by God.” Many of the Puritans who traveled to America had a “sacred vision of human progress.”

At a basic level, … the church is to be active in translating the teaching of the Scripture to every context of life, including politics.

Moreover, one might wager that despite the material differences, the substance is very much the same. What is meant is that while there is not a formally established

religion in America, there is nonetheless an “established” religion. How can this be true? The answer to that question is found in the basic facts of human existence. If human creatures are made in the image of God and are created for religious fellowship, then there are, necessarily, eschatological and religious ends which are intrinsic to, and determinative of, human existence. There is no politics, indeed, no knowledge, detached from this reality. In this way, as all people are inherently religious, all societies and all politics are necessarily and inescapably religious. Thus, at least in principle, the question is not whether there is an establishment, but which one.

And the facts are before our eyes. The recent cultural shift has been nothing but palpable, and behind this shift is an ideology that is actively shaping legislation, views of human nature, civic duties and freedoms, and the meaning and purpose of human life. The Christian church and American society no longer share common values or a broadly common religion; the church that was once prominent in the public square has been replaced by the synagogue of Satan, which has its own sacraments, such as abortion and “love wins” creeds. Is this what Friedrich Nietzsche had in view when speaking of the “freedom of the new dawn”? When human autonomy is coupled with a vague “pursuit of happiness,” a phrase which, as Malcolm Muggeridge noted, “is responsible for a good part of the ills and miseries of the modern world,” society will inexorably tend toward chaos. Humankind’s happiness, its beatitude, is found only in the God who made the world ex nihilo. “A Common-wealth is made glorious when it becometh holy and Christian,” says Anthony Burgess. Likewise, when a given society unabashedly repudiates the natural law and the plain teaching of the Scriptures, that society will become treacherous and evil. “Righteousness exalts a nation, but sin is a reproach to any people” (Prov. 14:34).

But what does this mean for our current moment? Shall we, at this juncture, legally establish the Christian religion in America? Is there something to glean from our forefathers? Some Christians argue that we ought not concern ourselves at all with the goings-on of the political world. Are we not awaiting heavenly Jerusalem, a new heaven and new earth? We most certainly are, and eagerly so, but while we long heavenward, we nonetheless have earthly duties. We do not so set our minds on heavenly things (Col. 3:1–2) that we do not pray for our earthly rulers (1 Tim. 2:2), or render unto

them that which ought to be rendered (Matt. 22:21), or do not submit to their governance as they support good conduct and punish evil (Rom. 13:3). Indeed, we still have a neighbor to love and friend or colleague to whom we should minister (Matt. 22:36–40). In other words, to borrow the language of Augustine and Calvin, remote ends do not destroy proximate ends, when rightly ordered. We ought not embrace a kind of political gnosticism.

“...while we long heavenward, we nonetheless have earthly duties.”

Thus, the first and most important thing that the church can and should do in our current moment is be a bold prophetic witness. What does this mean? At a basic level, it means that the church is to be active in translating the teaching of the Scripture to every context of life, including politics. In this way, Christians can—and should—be political. If there are policies that are sinful, the Christian ought to oppose them, for love “rejoiceth not in iniquity, but rejoiceth in the truth” (1 Cor. 13:6; emphasis added). As Westminster’s Paul Woolley remarked in his radio address Our American Christian Future, “[We] must not remain content with never having anything but the foundations of Christianity…[We] must present a gospel which says something about every sphere of human activity, that has bearing upon all of life, that comes to the secularized man where he now is and says, ‘Look what can be done with politics…’” Thus, politics, too, should be sanctified unto God, for “there is no realm of life which is exempt from the applicability of Scripture.”

Another concern about the intersection between religion and politics is that of the separation of church and state, which is often misunderstood. But given those facts which are basic to human existence, religion, then, is in politics insofar as man is in society. In his essay published in the Presbyterian Guardian entitled “The Christian World Order,” John Murray offers a principled argument against a complete separation of church and state, saying that a “Christian world order embraces

the state. Otherwise, there would be no Christian world order.” He then maintains,

The Bible is the only infallible rule of conduct for the civil magistrate in the discharge of his magistracy just as it is the only infallible rule in other spheres of human activity… this just means that the obligation and task arising from Christ’s kingship and headship are that civil government, within its own well-defined and restricted sphere, must in its constitution and in its legislative and executive functions recognize and obey the authority of God and of His Christ and thus bring all of its functions and actions into accord with the revealed will of God as contained in His Word… To recede from this position or to abandon it, either as conception or as a goal, is to reject in principle the sovereignty of God and of His Christ…

Murray concludes this essay with an exhortation regarding the “philosophy of Christian world order,” saying,

Who is sufficient for these things? We are indeed totally insufficient and the task is overpowering. But this overpowering sense of our weakness and inability is no reason for faintheartedness. It is rather the very condition of true faith and perseverance. The responsibility is ours: it is stupendously great. The insufficiency is ours: it is complete. But the power is God’s.

Indeed. As Thomas Goodwin once remarked, “They that will reforme a Church or State, must trust more in God in doing it, than in any work else.”

How then shall we live? The Christian today should recognize that religion and society are inseparably tied together. When we think about Christianity’s encounter with modern culture, we must at the outset remain true to the commission that we have received from our risen King and Lord Jesus Christ. If we are to reform a society, we must see that spiritual reformation is necessary for true and lasting cultural reformation. As Edward Reyn olds said, “It is not enough for the honour and security of a Kingdome that justice be in the Laws; it must be in the Judges too…” He continues, “Take away the Sun, and all the Stars of Heaven would never make day: So if a man… were destitute of faith in Christ, the Sun of righteousness,

have not God for his God, there would be night and calamity in his soul still.” Thus, without the spiritual reformation of individuals, even those in places of authority, there will not be true civil reformation. This means that now, in volatile times and with profound opposition, the church cannot, must not, capitulate. Cowardice must not masquerade as wisdom. Now is the time, by the grace of God, to stand fortified as a “pillar and bulwark of the truth” (1 Tim. 3:15).

J. Gresham Machen once remarked that “The Christian cannot be satisfied so long as any human activity is either opposed to Christianity or out of all connection with Christianity. Christianity must pervade not merely all nations, but also all of human thought.” Thus, our prayer should be that the gospel will resound to the ends of the earth, and not just resound, but renew every nation of the earth, that the peoples of this earth might proclaim that Jesus Christ is King of kings and Lord of lords, so that all of life may be lived unto Him. As Machen argued in Christianity and Culture, “Instead of obliterating the distinction between the kingdom and the world, or on the other hand withdrawing from the world into a sort of modernized intellectual monasticism, let us go forth joyfully, enthusiastically to make the world subject to God.” It is therefore most fitting to conclude with a passage from the American theologian John Davenport (1597–1670):

What I pray may be expected in future times, if the best Church, and the best Common-wealth grew up together? Oh blessed people, among whom each Administration shall conspire with one mouth, and one minde, to conjoyn and advance the Communion of Saints with the Civil Society! One of these Administrations will not detract from the other, but each will confirm the other if it stand, and stay it if it be falling, and raise it up if it be fallen down.

Nathan Nocchi is the Assistant Director of the Craig Center for the Study of the Westminster Standards and Managing Editor Westminster Magazine. Nathan is undertaking PhD studies in historical theology at Westminster Theological Seminary that focus on seventeenth-cen-

Dr. Lillback interviewed Dr. Edgar and Dr. Gaffin on the topic of Christian citizenship for Westminster Magazine. This inter view took place on Monday, July 22, 2024. The following has been compressed and condensed for clarity.

Peter A. Lillback (PAL): Dr. Gaffin, I would like to ask you this question. Citizenship is an idea that’s external to the Scriptures but enters into the Scriptures. How do you put those two together in your mind?

Richard B. Gaffin, Jr. (RBG): Peter, in fact, the Bible speaks pointedly to the issue of Christian citizenship. In Phi lippians 3:20, Paul addresses the church—the church, we should understand, not just in his day but for any and all times until Jesus returns—and he says, “our citizenship is in heaven.” So, Christians have a heavenly citizenship that comes as they are united to Christ by faith and are concerned to serve him. This is the Christian’s primary and ultimate citizenship. So, the question is, how does this heavenly citizenship manifest itself in the various earthly citizenships there are? I take it that was the direc tion of your question, a question the Bible leaves consid erable scope for in terms of how we address it.

PAL: Dr. Edgar, as you think about the ethics of citizen ship, obviously there was a sense in which Israel had a unique boundary for members within it, and Paul was a Roman and appealed to his citizenship. Do those biblical principles or historical facts give us any guidance for our own understanding of citizenship in the secular state that we’re members of?

William Edgar (WE): I think they do. As Dick said, our primary citizenship is in heaven. And we look forward to the fulfillment of that at the end of time when we will be citizens and have our primary identity with that reality. Now, God has placed us on this earth. He gave Adam and Eve and their progeny a cultural mandate. Culture includes citizenship as was suggested. It varies a great deal with the type of government we have. But it’s not negligible to think of our citizenship here on earth. You mentioned Paul’s appeals to Rome. That’s one scenario. You know, in China you have to be very cautious about getting involved with politics because of the dangers there. In a modern democracy . . . well, the way I like to put it is: “How do you render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s and to God the things that are God’s when

Peter A. Lillback

you are Caesar?” I think the implication is that God’s imprint is everywhere, whereas Caesar’s imprint is on the coin. And that coin looks different from age to age. But we have an allegiance or responsibility to honor Caesar, whatever form it takes. That is not in competition with—it’s a complement to—the heavenly comprehensive citizenship of God over all things.

PAL: Dr. Gaffin, since you’ve emphasized our heavenly citizenship, how does our citizenship in heaven compare or contrast with our citizenship in the earthly state? The word is used in both senses, obviously. What are your thoughts on comparing and contrasting the use of the word?

RBG: If I may, I’d like to back up and make the important point that in answering your question we need to be careful in using the Old Testament. To give an example, I’ve been struck in the aftermath of last October 7th how often comments and discussions about the war refer to Israel-Palestine as “the Holy Land”; even some secular reporters use that language. If I were to write an article, I would entitle it, “It’s No Longer the Holy Land.” The citizenship of the people of God now, in light of the coming of Christ, is no longer identified with or confined to one geopolitical order, as was the case with Old Testament Israel. The church in the Old Testament was ethnically limited; God’s people were one nation, holy in distinction from all others. Now the New Testament church is made up of not just Jews but non-Jews as well, Jews and Gentiles found in every ethnicity, present in every earthly political order. So the question becomes how Christians function given the state of affairs that has arrived in the death, resurrection, and ascension of Christ, where now he is, as Paul says, “head over all things to the church” (Eph. 1:22). How does that universal Lordship work out on earth?

PAL: Let’s zero in this way and say Christ is the Lord of everything, and we’re in a divine monarchy in the church, but in the American context we’re not in a monarchy; we’re in some sort of a constitutional democratic republic. In that setting, what does it mean to be a citizen of heaven? How is it different than being a citizen on earth?

WE: Since Pentecost, there has been no such thing as a Christian nation per se. There might be nations that come closer to putting biblical ideals into the law. But this

whole discussion of, for example, America as a Christian nation is misguided. As Dick suggested, the present expression of nationality is in the church. And the church has an ambiguous or paradoxical relationship to the surrounding system of government. We may be in a more or less free country where we get to decide and vote and set policy. Or we may be in a highly oppressive situation where we don’t get to make such decisions, and we may even have to resist. But there is no Christian nation today, and all this discussion of the Christian origins of America is often misguided because while there may have been a Christian influence in the Founding Fathers, you don’t want to call this a Christian nation. Instead, we should say that Christian principles were at work, but not necessarily [that we have a] Christian nationality. Anyway, yes, the citizenship is different. But of course, our heavenly citizenship not only does not preclude earthly responsibility, but it demands that we participate fully in the creation that God has given us, which means politics, as well as culture and the arts, science, business, and so forth.

PAL: Let me give an interesting historical test case for both of you to respond to. There was in 1892, perhaps you’ll remember, the Holy Trinity case that went all the way to the Supreme Court. And Chief Justice Brewer wrote, and a unanimous Supreme Court declared, by the organic utterances and many other evidences, “This is a Christian nation.” So at the end of the 19th century, there was a sense in our highest court that we could call the legacy of America Christian, that we were a Christian nation. Were they misguided? Were they onto something? What were they trying to get across? The Supreme Court is generally a lagging indicator of the beliefs of a country. At least historically, they tend to be indicating this is where we’ve come from. Maybe they’re going to change, but right now this is what we think. So I’d love to hear how you’d evaluate that both historically and perhaps theologically.

RBG: Tying into what Bill was emphasizing, I wonder if the Justice meant anything more than that there was a pervasive Christian influence which gave rise to the birth of our nation. Also, what did he mean by “Christian”? How do you become a Christian? What makes you a Christian? Those are questions that need clarification. I wonder, speaking at the end of the 19th century, if he

wasn’t reflecting in that language what Bill was pointing out, not that we are a Christian geopolitical entity but that undeniably there has been a significant Christian influence, for instance, on the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution.

WE: Glenn Scrivener, the British theologian, says that we’ve never been Christian, but there has been Christendom. And so, we shouldn’t talk today about being post-Christian because we never were a Christian nation in the sense that Israel was a believing nation. We had Christian influence, yet we were in Christendom. And even today as we get further and further from a Christian consciousness, we’re walking away from Christendom rather than Christianity. And I think that means that, as Dick was suggesting, there are undoubted Christian influences in our government. Just the separation of powers, for example, you can trace that back to the Puritan notion that you can’t trust one person or one group with all the authority. You’ve got to have checks and balances. The idea of the Constitution is somewhat rooted in the Covenant idea. Although there’s a lot as well of Enlightenment principles that are at work, not just Christian principles. So, it seems to me it’s a helpful distinction to say that we are abandoning Christendom, not Christianity, because we never were Christian.

PAL: Let’s put it this way. Is it good to abandon Christendom and become just totally a secular state or let’s say a quasi-Marxist state? Or is preserving Christendom a valuable thing because of the benefits that flow from it culturally?

RBG: You’re asking a fairly theoretical question, and I’m not a political scientist. I don’t know how helpful this will be to our conversation, but I do think it gets at what you were asking about initially, Peter. What shapes my thinking is a passage like 1 Timothy 2:2, where in the context of the Pastoral Epistles, Paul has in view not only the immediate circumstances of the church in Ephesus but the entire post-apostolic future of the church and what should be the outlook and conduct of Christians looking toward Christ’s return. There he makes the point that we are to pray for governing authorities “that we [the church, Christians] may lead a peaceful and quiet life, ….” While that was written in the context of submission to the autocratic governance of the Roman Empire,

whereas we have the democratic advantage of having a say in government by voting for or even participating in government, Paul’s exhortation still stipulates an agenda for us: what we are to pray for is what we are to be concerned to work for, as we are able and have opportunity. And that goal is a political order that promotes peace and ordered, quiet living as that would be not only for the good of believers and the well-being of the church, but also for all citizens.

WE: To answer your question directly, it’s tragic to abandon Christendom-type principles. And we see that increasingly in the trends around us. We have to, as Dick said, pray for peace and order that the gospel may run its full course. So our prayer for peace and order is not just for the good of humanity, but it’s also for the sake of the gospel going forward.

It’s awful to see the country departing from Christendom. But the answer is not theocracy. The answer is to pray for order and peace and justice. Just as Paul in Romans 13 alludes to the fact that authority is legitimate, governmental authority is legitimate, and it contributes to rewarding the good as well as punishing the bad. Those are, I think, principles that transcend the different episodes of government.

PAL: Some time ago I was reflecting on the question, did our founders intend to create a Christian nation? And the answer became really clear to me when I was reading the Constitution. In Article VI it says “the supreme law of the land” is this constitution. It doesn’t say it’s the Bible. It’s clear that they intended to have a standard that was not the Bible. So it’s not making it a Christian nation, but they created a constitution, it seems to me, that has the ability to let consciences have freedom. And that was obviously augmented by the First Amendment, the free exercise of religion and the government not having the right to establish it. So I think we have then, whether we call it Christendom or Christian influence into a new form of government, the kind of peace that means that you have religious liberty and the freedom to make influence for the good.

So that brings me then to the classic text from Jesus of the Sermon on the Mount, where he tells us that we are the salt of the earth and the light of the world. And Christians have often taken that to say that by our work, we are helping to preserve what is good and prevent

decay, and also to dispel darkness. And it has that notion perhaps of cultural influence, of political impact. How do you look at that particular biblical text and its use in that way, in terms of our notions of citizenship?

RBG: Well, that has a nice aphoristic ring to it when it’s quoted by itself, but we are bound to see it in context, particularly as it flows directly out of the Beatitudes, which mark the effects of the grace of God in bringing the kingdom as the rule and realm of the redemption accomplished by Christ. Among those effects mentioned is seeking genuine peace. Then the issue becomes a matter of what that peace is and how you go about realizing it. I read something recently—an article for the 100th anniversary of Machen’s Christianity and Liberalism—picking up on a quote of Machen concerning what Jesus says later in chapter six of Matthew, which is also part of the Sermon on the Mount, and so has to be related to your “salt of the earth” question. This is in a context where Jesus is noticing things in human life and society that create anxiety: concern about food, clothing, and, by implication, shelter (Matt. 6:25‒31); in view more broadly, we may say, is the economic aspect of our lives, those things that any just political order ought to be concerned about. Concerning these anxiety-producing matters Jesus makes a basic distinction. He says, “seek first the kingdom of God and his righteousness, and all these things will be added to you” (Matt. 6:33‒34). “All these things,” the things that can cause anxiety, God is well aware of our need of them (verse 32) and will provide for them. Concerning this distinction of Jesus, Machen makes an observation that really struck me. He says, if you understand seeking the kingdom of God as realized in bringing about all these added things or merely a means to the end of realizing them, then you will get neither the kingdom nor these things. But when you make seeking the kingdom of God primary—responding to the gospel of the kingdom by faith in Christ for the salvation he provides from sin— then all these other things will be provided. And as they are provided for God’s people, then as we love neighbor as well as self, we will have a concern for a just and quiet peaceful order for all citizens, whether confessing kingdom-followers of Christ or not, and will contribute as we can to that political end.

WE: Going back to the Founding Fathers, I think the creation of our Constitution was a work of genius. It

provided for freedom of conscience and not freedom from religion, but freedom for religion. But it’s important to remember that the founders owned slaves. Some were nativists that resented Catholic immigration. There was a lot of work to be done, and we had to go as far as the Civil War to resolve some of those problems.

PAL: Dr. Edgar, you’ve had a great exposure to the Huguenots in France, and they had an experience of losing their citizenship in France because of the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, and many of them fled to America, where they became great defenders of the American experience, in fact the Declaration as well as the Constitution. Why did the Huguenots find the American expression of government such a blessing for them given their history?

WE: Well, because of what I said earlier about the freedom to express one’s faith without the oppressive constraint of government. Remember, they went to Germany, they went to Holland, they went to England, they went to countries that had been influenced by the Reformation, and the Reformation with all of its drawbacks promoted freedom through discussion and through dissent as opposed to freedom through revolution. And so I think the Huguenots were drawn to that. And though they loved their mother country, they could be more salt and light in those new situations than they ever could in their own country.

PAL: Dr. Gaffin, I believe it is Dr. Van Til in his book Christian Theistic Ethics who says the summum bonum of the Christian life is the pursuit of the kingdom of God. So as a citizen on earth pursuing that summum bonum, how do we live that out as our highest goal, even as we go about our daily business, including engaging in political things? Is there a dialectic? Is there a commonality? How do we pursue that and then impact other aspects of our duties as a citizen?

RBG: That’s a very important question. Maybe, in responding, I could draw our attention again to Philippians 3:20, that our citizenship is in heaven. When we turn over to Colossians and the opening verses of chapter 3 (1‒4), we have an indication of how that heavenly citizenship originates and something of what marks it. Christians are heavenly citizens because they have

been united with Christ in his resurrection, so that for them, in union with Christ ascended and “seated at the right hand of God,” nothing less than “your life” itself “is hidden with Christ in God.” Further, the citizens of heaven are to be active citizens. They are to “seek” and “set [their] minds on” “the things that are above.” Their aspiration is to be everything that pertains to the present life and rule of the ascended Christ. This is clearly a large scale, comprehensive imperative for the church, this call for Christians to be heavenly-minded in all they do. But it should not be missed that the striking thing in Colossians 3 is that this heavenly-mindedness is not simply an otherworldly preoccupation but very much a down-toearth reality. The immediately following verses through 4:1 go on first to address the proper use of the body, then interpersonal relationships within the church, before moving on to how heavenly-minded seeking the things above plays out in marriage, in the home, family life, and beyond—most directly related to the question we’re dealing with—the economic concerns of life. A key aspect of seeking the things above is doing what pleases the Lord, and what pleases the Lord is keeping his commandments, in whatever ways that can apply. So then in our present situation, a just political order, and someone wanting to enter into the political process and seek office, will want to facilitate what will promote pleasing the Lord and be conducive to seeking his kingdom. Christians will be any earthly good only as they are heavenly-minded.

PAL: If you had young people who felt they had leadership gifts and were fascinated by the principles of politics and what earthly citizenship means, what would you advise them if they asked, “Should I enter into politics today given the realities that we’re facing?” What would be your council?

WE: Well, I’ve got some thoughts on that. First of all, I’m a great believer in the primacy of local politics over national politics. So if you’re called into the political life, you should consider first your local responsibilities. Are you involved with the practices of neighborliness, of garbage disposal, or whatever. And for that matter, does your participation reflect what Dick was saying, obedience to the commandments? Now, beyond that, there are a few who are called to more prominent leadership in the world, including the highest offices. And I would say with cautious optimism, they should participate

in political life as Christians—not thinking that legal maneuvering is going to change the world but thinking that bringing the righteousness of the kingdom into the political process will be reflecting the heavenly citizenship that is our primary place of consolation and of security.

So one phrase I heard, which I think is helpful, is “Jesus is political, but he was not partisan.” So it’s a big mistake to think that the only way to be a public leader is to align yourself with certain precepts and set positions about immigration and so forth. I think that political involvement is crucial, but be very careful of the particular choices you make as a partisan because they tend to be tentative and relative. They might be helpful and true, but they should be held with a light hand.

RBG: I would second the point that Bill was making; all politics is local. I think that’s been said, particularly for someone starting out, and that’s very good advice. That’s likely the way a person would have to start out anyway. The increasing dominance of the way government has been centralized and consolidated in Washington presents a formidable challenge for a Christian in politics at the national level.

PAL: Let me zero in on some of our duties as heavenly citizens, with a duty to honor King Jesus in all that we do, seeking his kingdom, seeking the common good through prayer, through peace, through love, through obeying the commandments. We have duties then in our earthly task. So let’s start with the beginning. Should Christians pay taxes to a government they believe is unjust?

WE: They should, as long as at the same time they’re working to reform the system. In other words, yes, pay taxes. We don’t have a choice about that, but don’t stop your activities there. You go on to try to change the system to make it more just. Christ is the great example of this. He, of course, paid taxes. He pulled the coin out of the lake, but he also ministered to Zacchaeus, and Zacchaeus under his influence reformed his views. So as long as you’re working as best you can to change the system, yes, you should pay taxes even to an unjust government. I don’t want to lose track of what Dick was saying. [Even though it can be] very discouraging for good young people to go into the political arena, there’s got to be a way in which people of integrity can move forward in

a limited way but in a forthright way to make changes. And right now it’s nearly impossible for a good person to do that, which is a very sad statement about American politics.

RBG: Romans 13 seems pretty clear in what was manifestly a situation where the autocratic functioning of the Roman empire could be quite unjust and abusive. Even though that passage is challenging exegetically at points, it is clear that however political or governmental power may be abused, it still is ordained by God. First Peter 2:13‒14 is another passage that makes that point. But then I would emphasize what Bill said, that when we have the political capacity, do everything we can to get rid of unjust taxation. Over the years, this became an issue for parents with children in Christian schools who were not willing to have their children in public schools because of the non-Christian influence there. I know of one case where a person took the amount of their school taxes, put it in a bank account, and told the government, “If you want it, you can go get it. I’m not going to pay you.”

PAL: Is it our duty of citizenship to volunteer to serve in the military to defend the land, or be willing to be drafted? Is that something that we ought to do.

WE: Of course. Each of these institutions is legitimate as a creation ordinance. That includes the defense of property and the defense of a country. So those are legitimate callings. Obviously, you can abuse them. I think pacifism is a romantic dream. But it’s like marriage or business or any of these spheres. They’re legitimate, but there’s going to be huge abuses and problems. We all know that marriage is good, but we also see terrible marriages. And the answer is not to abolish marriage. The answer is to work for the improvement of the institution. Now, it gets very complicated, but I think that’s the same set of answers to your first question: Should we be paying taxes? [Should we] go into the military? Yes. But as we do that, we need to work towards the biblically based improvement of these institutions.

PAL: Dr. Gaffin, any further thoughts?

RBG: Well, that raises the issue of just war, which I think is to be affirmed biblically for various reasons, some of

which Bill has indicated. So, if I were much younger and draftable, as a believer I could be faced with my government initiating an unjust war. I think, akin to the question about taxation, I would have to go along with the government unless, you know—the Third Reich comes to mind and people like Bonhoeffer taking the stand of opposition that he and others did, which, I certainly want to affirm. But it could be a difficult question under circumstances which are less stark than the rise of the Third Reich and Nazism taking over the entire political process. My default position would be that I have to go along with the government, right or wrong, like taxation, right or wrong.

WE: When I was younger, the big issue for us was the Vietnam War. And I had friends who paid their taxes except the part that they thought was going to supply the war effort. I chose to oppose the war, not by illegal measures such as refusing to pay taxes, but by persuasion. Now, sometimes persuasion is not possible. You mentioned Bonhoeffer. I don’t think persuasion was going to work for him, and for our Huguenot ancestors, persuasion wasn’t always possible. But I think it should be a very, very rare default position to resist in some sort of clearly physical way. Calvin has helpful teachings on this. He’s very reluctant to change the regime, Christian resistance or not. He does admit that there are cases when there has to be resistance to tyranny, but even there, it’s got to be in line with a secondary magistrate or with some legal entity. He’s totally against vigilante justice, and I think that’s biblical. There’s no call in Scripture to lash out as a Clint Eastwood type of rebellion against the system. You’ve got to work within the system, however unjust it might be.

PAL: You have been very generous with your time. I should bring it to a close, but I do want to ask you about the issue of citizenship and voting and the context. What counsel do you give people at this moment? Does a Christian have an obligation to vote? If they vote, is there any legitimacy in voting for what you believe to be the lesser of two evils? Since we’re not voting for king Jesus in this context—we don’t vote for king Jesus anyway, who sovereignly chooses us. Given that we’re in a broken, fallen world, what are our duties as citizens . . . in a democratic republic, for exercising our right as a citizen to vote?

RBG: I’m aware of various Christian bloggers and journalists who are telling me that I ought not to vote, that this election—particularly for president—is one that believers ought to sit out. I’m not persuaded by that. Peter, you put it in terms of the lesser of two evils. I do think the person, particularly the person of the president, is very important. I get that and I get the problems that can be raised about the candidates. Well, just as we’re talking this morning there’s going to be significant change on the one side. But the way I look at it—particularly as a federal election—is that I’m voting not only for a president, as significant and influential as that person undoubtedly is and will be if elected, but for an administration with the party platform it intends to implement. So, I need to determine what will be most conducive to what would be pleasing to the Lord between one administration or the other. And I need to vote that way. That’s my present thinking.

WE: I think that’s exactly right. All political decisions that we make are going to be challenged by things we don’t like, even the best of all candidates. We won’t agree with all their platforms. The difficulty is when you have a couple of candidates whose platforms and character are very dubious. And [...] you vote for what the administration might bring that’s a bit better than what already exists. [There are times when you may need to] vote your conscience. And I think sometimes you have to do that rather than think that your vote is going to change the world. You vote for what you think the administration might bring, and it’s all fallible, but you can’t retreat into political indifference, because Jesus was political, not partisan.

PAL: All right. As we conclude, I’ll just put this pointed question this way: In your quest to honor Christ, can a Christian simply choose in a democratic republic not to vote and not get involved? Is that an option? Or is that abandoning our duty as a Christian?

RBG: Well, I’ve mentioned blogs that I’m aware of that argue as a matter of principle that we ought not to vote, particularly for president. As I’ve said, I don’t agree with that. But if, as you put it very pointedly, Peter, I think not voting is a defensible position, although less

defensible than what I’ve expressed. Is that too weaselly an answer?

PAL: That sounds like a pointed answer that doesn’t want to be too harsh. So that’s good [laughs].

WE: And don’t forget that not to vote is actually to vote for some default candidate or party. It’s not as if not voting gets you out of the process. So in a country where the vote is possible, you have to do it. But it is very challenging indeed in our current political state of affairs.

PAL: You’ve been very gracious. You have spoken as Christian gentlemen about touchy issues. Let me have the privilege of concluding us with a word of prayer if I might.

Lord, I thank you for these gentlemen who love you, who have given their lives for your glory and your service to advance the kingdom as the primary concern of their lives. They are role models and blessings in so many ways. We do pray, Lord, that readers would find, in the conversation we’ve had today, wisdom and truth that will bless your people, [who] will be seeking guidance and prayer and encouragement. Lord, we do pray for the crisis that’s before the world and before our nation. Lord, we pray for President Biden and his family as he’s made a massive decision. We do pray for the Democratic convention that will be meeting in Chicago, Lord, that you’ll [rule over] that according to your wise council and for the good of your people. We thank you for the Republican National Convention’s completion. We pray, in spite of all the challenges that are before everyone, that good might come through it. And Lord, regardless of our politics, we’re grateful that the attempt on the former president’s life was not successful, for Lord, that only makes us less a part of the Christendom that we’ve spoken of, of honoring those that lead even when we disagree with them. Lord, would you please let us find the kingdom of God advancing by our fidelity to your word, by the work of your Spirit? And as we’ve been reminded, we thank you that our citizenship is with the risen Christ. We appeal to your throne for your glory and the advance of your name and the completion of your kingdom. May this be a small step toward that. We thank you for the joy of serving you, and we pray for health and strength and blessing upon these brothers, and we ask it in Christ’s name. Amen.

A review By Pierce Taylor Hibbs

Food chains have always fascinated me. It wasn’t so much the “kill or be killed” tenacity that drew my attention. It was the interrelation of all things— the delicate harmony that would shatter if just a single creature were removed from the chain. It was comforting to me that God had built a world this way, a place where the significance of the smallest carried weight, where—to use Leonardo Da Vinci’s words—“everything connects to everything else.”

Food chains exist in the public square, too. They just take the form of ideologies and cultural trends. God is Lord over all relations, including where Christianity fits in that chain at any given moment in history. And history shows these chains are fluid. What’s in vogue Monday might be unfashionable by Friday. But not all changes are so light or superficial. Many have serious consequences. As I’ve heard David Owen Filson say, “Ideas have consequences; bad ideas have victims.” Ideologies do not just switch places in the chain of popular opinion. They might also crush or abuse those who find themselves beneath them. And so the principle of natural food chains applies to ideological ones as well: know where you are.

The principle of natural food chains applies to ideological ones as well: know where you are.

This sets the stage for Aaron M. Renn’s book Life in the Negative World: Confronting Challenges in an Anti-Christian Culture (Zondervan 2024), a work that has already had broad influence in Christian circles. Essentially, the book is about a shift in America’s ideological food chain. Christianity was once a fierce creature here—setting moral standards and shaping legislature. But in the last sixty years, it’s moved down. Those who call themselves Christians today are unsuspecting prey for larger and more widespread ideologies such as secularism, pragmatism, materialism, Marxism, egalitarianism, and a host of others. God is still Lord over these changes. So, despite the particular place Christianity has in a given culture, we know that Christ is King. He may just work out that

kingly rule with patience for rebellious hearts. (Isn’t that what he does with all of us?)

Let me set out a synopsis for the book and then offer some engagement with a selection of Renn’s ideas. My goal is not to be analytically thorough but to be thought-provoking in helping Christians both question and then build on Renn’s work.

Renn argues that we can think of Christianity in America for the last sixty years as falling into three identifiable eras: the positive world (1964–1994), the neutral world (1994–2014), and the negative world (2014–present). His selection of these dates is intentional but somewhat arbitrary. In the positive world, “Publicly being a Christian enhances social status. Christian moral norms are still the basic moral norms of society, and violating them can lead to negative consequences.” In the neutral world, “Christianity no longer has privileged status, but nor is it disfavored. . . . Christian moral norms retain some residual effect.” But in our own time, the negative world, “society has an overall negative view of Christianity. Being known as a Christian is a social negative. . . . Christian morality is expressly repudiated and now seen as a threat to the public good and new public moral order.”

Renn uses political scandals to represent each era. Rumors of a possible affair could end your political career in the positive world (Gary Hart, 1987). But in the neutral world, a politician could survive this, appealing to the separation of public and private life (Bill Clinton, 1998). In the negative world, egregious moral failures are overlooked as insubstantial because Christian moral standards and the importance of character have been washed away (Donald Trump, 2016).

Renn suggests a series of causes for the shift from neutral to negative: the collapse of the WASP establishment, the sixties social and sexual revolutions, the end of the Cold War, deregulation of the corporate sector (allowing a smaller group of large companies to gain dominance), and digitization (financial, professional, and social engagement moving online).

The remainder of the book focuses on strategies Christians might adopt for life in the negative world. After considering which model of Christian civic life you might pursue (culture war, seeker sensitivity, or cultural

engagement), Renn reminds readers of the deeper problem: “American evangelicals are largely operating as though they’re still living in the lost positive or neutral worlds.” Christians today have not truly accepted that we are the real minority now, that we have been pushed down the country’s ideological food chain. For Renn, this means we need to critically assess which models of civic life have worked best in the past, and how we might reconstruct or reapply them in the present. But it also means thinking about how we live personally, institutionally, and missionally.

On a personal level, Renn first calls Christians to obedience. Obeying the truth of Scripture amidst a hostile world is a necessity. We cannot sacrifice biblical orthodoxy for the sake of cultural compromise. Second, Renn encourages Christians to pursue excellence—especially intellectual excellence. He warns of the loss of intellectual excellence in evangelicalism and the exodus of intellectuals to different realms of Christianity (mainline Protestant Christianity, Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy), or to full blown secularism. But excellence goes beyond the intellectual. Each one of us needs to commit to excellence in our field, whatever it may be. As to how we might learn of and measure this sort of excellence, Renn offers few details. Third, Renn invites evangelicals to be resilient. This means not only standing back up after being persecuted for our beliefs, but also taking proactive measures to ensure our financial independence (so as not to be reliant on government-based funding).

On the institutional level, Renn asks evangelicals to pursue another triad of traits: integrity, community strength, and ownership of social and cultural spaces.