Western Journal of Emergency Medicine:

Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health Indexed in MEDLINE

Behavioral Health

144

Characteristics for Low, High and Very High Emergency Department Use for Mental Health Diagnoses from Health Records and Structured Interviews

Marie-Josée Fleury, Zhirong Cao, Guy Grenier

Cardiology

155 Bridging the Gap: Evaluation of an Electrocardiogram Curriculum for Advanced Practice Clinicians

Steven Lindsey, Tim P. Moran, Meredith A. Stauch, Alexis L. Lynch, Kristen Grabow Moore

160 Stage B Heart Failure Is Ubiquitous in Emergency Patients with Asymptomatic Hypertension

Kimberly Souffront, Bret P. Nelson, Megan Lukas, Hans Reyes Garay, Lauren Gordon, Thalia Matos, Isabella Hanesworth, Rebecca Mantel, Claire Shubeck, Cassidy Bernstein, George T. Loo, Lynne D. Richardson

166

Performance of Intra-arrest Echocardiography: A Systematic Review

Yi-Ju Ho, Chih-Wei Sung, Yi-Chu Chen, Wan-Ching Lien, Wei-Tien Chang, Chien-Hua Huang

Education

175 Staffing Patterns of Non-ACGME Fellowships with 4-Year Residency Programs: A National Survey

David A. Haidar, Laura R. Hopson, Ryan V. Tucker, Rob D. Huang, Jessica Koehler, Nik Theyyunni, Nicole Klekowski, Christopher M. Fung

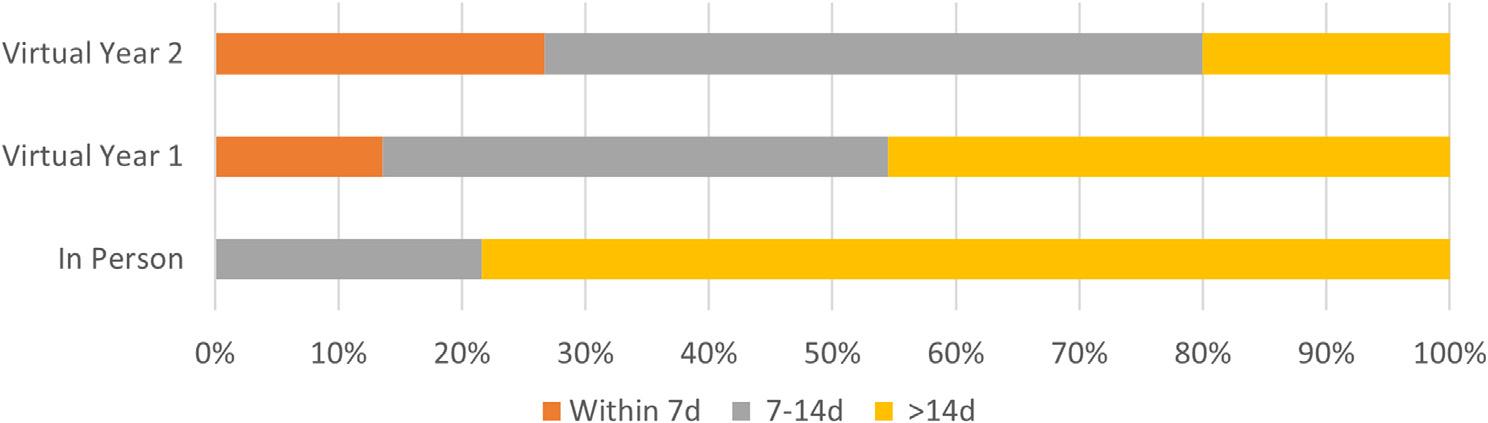

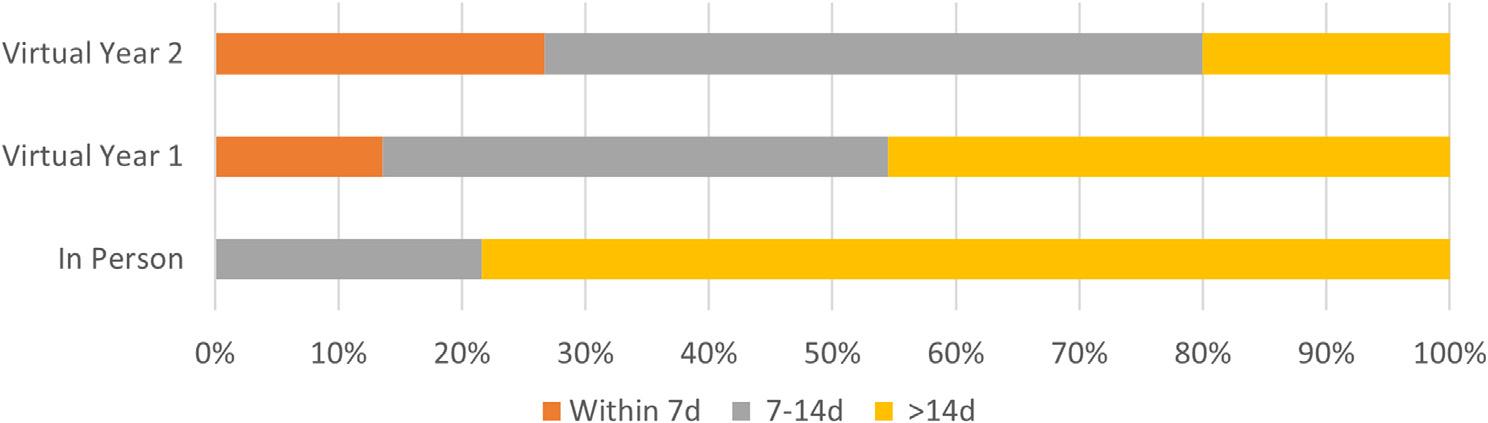

181 Changes in Residency Applicant Cancellation Patterns with Virtual Interviews: A Single-site Analysis

Meryll Bouldin, Carly Eastin, Rachael Freeze-Ramsey, Amanda Young, Meredith von Dohlen, Lauren Evans, Travis Eastin, Sarah Greenberger

Volume 25, Number 2, March 2024 Open Access at WestJEM.com ISSN 1936-900X A Peer-Reviewed, International Professional Journal Western Journal of Emergency Medicine VOLUME 25, NUMBER 2, March 2024 PAGES 144-302

continued on page iii West

Contents

Western Journal of Emergency Medicine:

Andrew W. Phillips, MD, Associate Editor DHR Health-Edinburg, Texas

Edward Michelson, MD, Associate Editor Texas Tech University- El Paso, Texas

Dan Mayer, MD, Associate Editor

Retired from Albany Medical College- Niskayuna, New York

Wendy Macias-Konstantopoulos, MD, MPH, Associate Editor Massachusetts General Hospital- Boston, Massachusetts

Gayle Galletta, MD, Associate Editor

University of Massachusetts Medical SchoolWorcester, Massachusetts

Yanina Purim-Shem-Tov, MD, MS, Associate Editor Rush University Medical Center-Chicago, Illinois

Resident Editors

AAEM/RSA

John J. Campo, MD

Harbor-University of California, Los Angeles Medical Center

ACOEP

Justina Truong, DO Kingman Regional Medical Center

Section Editors

Behavioral Emergencies

Leslie Zun, MD, MBA Chicago Medical School

Marc L. Martel, MD Hennepin County Medical Center

Cardiac Care

Fred A. Severyn, MD University of Colorado School of Medicine

Sam S. Torbati, MD

Cedars-Sinai Medical Center

Clinical Practice

Cortlyn W. Brown, MD Carolinas Medical Center

Casey Clements, MD, PhD Mayo Clinic

Patrick Meloy, MD Emory University

Nicholas Pettit, DO, PhD Indiana University

David Thompson, MD University of California, San Francisco

Kenneth S. Whitlow, DO Kaweah Delta Medical Center

Critical Care

Christopher “Kit” Tainter, MD University of California, San Diego

Gabriel Wardi, MD

University of California, San Diego

Joseph Shiber, MD University of Florida-College of Medicine

Matt Prekker MD, MPH Hennepin County Medical Center

David Page, MD University of Alabama

Erik Melnychuk, MD Geisinger Health

Quincy Tran, MD, PhD University of Maryland

Disaster Medicine

John Broach, MD, MPH, MBA, FACEP University of Massachusetts Medical School UMass Memorial Medical Center

Mark I. Langdorf, MD, MHPE, Editor-in-Chief University of California, Irvine School of MedicineIrvine, California

Shahram Lotfipour, MD, MPH, Managing Editor

University of California, Irvine School of MedicineIrvine, California

Michael Gottlieb, MD, Associate Editor Rush Medical Center-Chicago, Illinois

Niels K. Rathlev, MD, Associate Editor Tufts University School of Medicine-Boston, Massachusetts

Rick A. McPheeters, DO, Associate Editor Kern Medical- Bakersfield, California

Gentry Wilkerson, MD, Associate Editor University of Maryland

Christopher Kang, MD Madigan Army Medical Center

Education

Danya Khoujah, MBBS

University of Maryland School of Medicine

Jeffrey Druck, MD University of Colorado

John Burkhardt, MD, MA

University of Michigan Medical School

Michael Epter, DO Maricopa Medical Center

ED Administration, Quality, Safety

Tehreem Rehman, MD, MPH, MBA Mount Sinai Hospital

David C. Lee, MD Northshore University Hospital

Gary Johnson, MD Upstate Medical University

Brian J. Yun, MD, MBA, MPH Harvard Medical School

Laura Walker, MD Mayo Clinic

León D. Sánchez, MD, MPH

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center

William Fernandez, MD, MPH University of Texas Health-San Antonio

Robert Derlet, MD

Founding Editor, California Journal of Emergency Medicine

University of California, Davis

Emergency Medical Services

Daniel Joseph, MD Yale University

Joshua B. Gaither, MD

University of Arizona, Tuscon

Julian Mapp

University of Texas, San Antonio

Shira A. Schlesinger, MD, MPH Harbor-UCLA Medical Center

Geriatrics

Cameron Gettel, MD Yale School of Medicine

Stephen Meldon, MD Cleveland Clinic

Luna Ragsdale, MD, MPH Duke University

Health Equity

Emily C. Manchanda, MD, MPH Boston University School of Medicine

Faith Quenzer

Temecula Valley Hospital San Ysidro Health Center

Shadi Lahham, MD, MS, Deputy Editor

Kaiser Permanente- Irvine, California

Susan R. Wilcox, MD, Associate Editor

Massachusetts General Hospital- Boston, Massachusetts

Elizabeth Burner, MD, MPH, Associate Editor

University of Southern California- Los Angeles, California

Patrick Joseph Maher, MD, MS, Associate Editor Ichan School of Medicine at Mount Sinai- New York, New York

Donna Mendez, MD, EdD, Associate Editor

University of Texas-Houston/McGovern Medical School- Houston Texas

Danya Khoujah, MBBS, Associate Editor

University of Maryland School of Medicine- Baltimore, Maryland

Mandy J. Hill, DrPH, MPH

UT Health McGovern Medical School

Payal Modi, MD MScPH

University of Massachusetts Medical

Infectious Disease

Elissa Schechter-Perkins, MD, MPH Boston University School of Medicine

Ioannis Koutroulis, MD, MBA, PhD

George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences

Kevin Lunney, MD, MHS, PhD University of Maryland School of Medicine

Stephen Liang, MD, MPHS Washington University School of Medicine

Victor Cisneros, MD, MPH Eisenhower Medical Center

Injury Prevention

Mark Faul, PhD, MA

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Wirachin Hoonpongsimanont, MD, MSBATS

Eisenhower Medical Center

International Medicine

Heather A.. Brown, MD, MPH Prisma Health Richland

Taylor Burkholder, MD, MPH

Keck School of Medicine of USC

Christopher Greene, MD, MPH University of Alabama

Chris Mills, MD, MPH

Santa Clara Valley Medical Center

Shada Rouhani, MD Brigham and Women’s Hospital

Legal Medicine

Melanie S. Heniff, MD, JD Indiana University School of Medicine

Greg P. Moore, MD, JD

Madigan Army Medical Center

Statistics and Methodology

Shu B. Chan MD, MS Resurrection Medical Center

Stormy M. Morales Monks, PhD, MPH Texas Tech Health Science University

Soheil Saadat, MD, MPH, PhD University of California, Irvine

James A. Meltzer, MD, MS

Albert Einstein College of Medicine

Musculoskeletal

Juan F. Acosta DO, MS Pacific Northwest University

Rick Lucarelli, MD Medical City Dallas Hospital

William D. Whetstone, MD

University of California, San Francisco

Neurosciences

Antonio Siniscalchi, MD

Annunziata Hospital, Cosenza, Italy

Pediatric Emergency Medicine

Paul Walsh, MD, MSc

University of California, Davis

Muhammad Waseem, MD Lincoln Medical & Mental Health Center

Cristina M. Zeretzke-Bien, MD University of Florida

Public Health

Jacob Manteuffel, MD

Henry Ford Hospital

John Ashurst, DO Lehigh Valley Health Network

Tony Zitek, MD

Kendall Regional Medical Center

Trevor Mills, MD, MPH

Northern California VA Health Care

Erik S. Anderson, MD

Alameda Health System-Highland Hospital

Technology in Emergency Medicine

Nikhil Goyal, MD

Henry Ford Hospital

Phillips Perera, MD

Stanford University Medical Center

Trauma

Pierre Borczuk, MD

Massachusetts General Hospital/Havard Medical School

Toxicology

Brandon Wills, DO, MS

Virginia Commonwealth University

Jeffrey R. Suchard, MD

University of California, Irvine

Ultrasound

J. Matthew Fields, MD Thomas Jefferson University

Shane Summers, MD Brooke Army Medical Center

Robert R. Ehrman

Wayne State University

Ryan C. Gibbons, MD Temple Health

Volume 25, No. 2: March 2024 i Western Journal of Emergency Medicine Available in MEDLINE, PubMed, PubMed Central, CINAHL, SCOPUS, Google Scholar, eScholarship, Melvyl, DOAJ, EBSCO, EMBASE, Medscape, HINARI, and MDLinx Emergency Med. Members of OASPA. Editorial and Publishing Office: WestJEM/Depatment of Emergency Medicine, UC Irvine Health, 3800 W. Chapman Ave. Suite 3200, Orange, CA 92868, USA Office: 1-714-456-6389; Email: Editor@westjem.org

Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health Indexed in MEDLINE, PubMed, and Clarivate Web of Science, Science Citation Index Expanded

Official Journal of the California Chapter of the American College of Emergency Physicians, the America College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians, and the California Chapter of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Western Journal of Emergency Medicine:

Amin A. Kazzi, MD, MAAEM

The American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon

Brent King, MD, MMM University of Texas, Houston

Christopher E. San Miguel, MD Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center

Daniel J. Dire, MD University of Texas Health Sciences Center San Antonio

Douglas Ander, MD Emory University

Edward Michelson, MD Texas Tech University

Edward Panacek, MD, MPH University of South Alabama

Francesco Della Corte, MD Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria “Maggiore della Carità,” Novara, Italy

Gayle Galleta, MD

Editorial Board

Sørlandet Sykehus HF, Akershus Universitetssykehus, Lorenskog, Norway

Hjalti Björnsson, MD

Icelandic Society of Emergency Medicine

Jaqueline Le, MD Desert Regional Medical Center

Jeffrey Love, MD

The George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences

Katsuhiro Kanemaru, MD University of Miyazaki Hospital, Miyazaki, Japan

Kenneth V. Iserson, MD, MBA University of Arizona, Tucson

Leslie Zun, MD, MBA Chicago Medical School

Linda S. Murphy, MLIS

University of California, Irvine School of Medicine Librarian

Niels K. Rathlev, MD

Tufts University School of Medicine

Pablo Aguilera Fuenzalida, MD

Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, Región Metropolitana, Chile

Peter A. Bell, DO, MBA Baptist Health Sciences University

Peter Sokolove, MD University of California, San Francisco

Rachel A. Lindor, MD, JD Mayo Clinic

Robert Suter, DO, MHA UT Southwestern Medical Center

Robert W. Derlet, MD University of California, Davis

Rosidah Ibrahim, MD Hospital Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia

Scott Rudkin, MD, MBA University of California, Irvine

Scott Zeller, MD

University of California, Riverside

Steven H. Lim, MD

Changi General Hospital, Simei, Singapore

Terry Mulligan, DO, MPH, FIFEM ACEP Ambassador to the Netherlands Society of Emergency Physicians

Wirachin Hoonpongsimanont, MD, MSBATS

Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand

Elena Lopez-Gusman, JD

California ACEP

American College of Emergency Physicians

Jennifer Kanapicki Comer, MD FAAEM

California Chapter Division of AAEM Stanford University School of Medicine

DeAnna McNett, CAE

American College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians

Kimberly Ang, MBA

UC Irvine Health School of Medicine

Randall J. Young, MD, MMM, FACEP

California ACEP

American College of Emergency Physicians

Kaiser Permanente

Mark I. Langdorf, MD, MHPE, MAAEM, FACEP

UC Irvine Health School of Medicine

Robert Suter, DO, MHA

American College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians

UT Southwestern Medical Center

Shahram Lotfipour, MD, MPH FAAEM, FACEP

UC Irvine Health School of Medicine

Jorge Fernandez, MD, FACEP

UC San Diego Health School of Medicine

Isabelle Nepomuceno, BS Executive Editorial Director

Visha Bajaria, BS WestJEM Editorial Director

Emily Kane, MA WestJEM Editorial Director

Stephanie Burmeister, MLIS WestJEM Staff Liaison

Cassandra Saucedo, MS Executive Publishing Director

Nicole Valenzi, BA WestJEM Publishing Director

June Casey, BA Copy Editor

Western Journal of Emergency Medicine ii Volume 25, No. 2: March 2024 Available in MEDLINE, PubMed, PubMed Central, Europe PubMed Central, PubMed Central Canada, CINAHL, SCOPUS, Google Scholar, eScholarship, Melvyl, DOAJ, EBSCO, EMBASE, Medscape, HINARI, and MDLinx Emergency Med. Members of OASPA. Editorial and Publishing Office: WestJEM/Depatment of Emergency Medicine, UC Irvine Health, 3800 W. Chapman Ave. Suite 3200, Orange, CA 92868, USA Office: 1-714-456-6389; Email: Editor@westjem.org Official Journal of the California Chapter of the American College of Emergency Physicians, the America College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians, and the California Chapter of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Advisory

Editorial Staff

Board

Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health Indexed in MEDLINE, PubMed, and Clarivate Web of Science, Science Citation Index Expanded

Western Journal of Emergency Medicine:

Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health

Indexed in MEDLINE, PubMed, and Clarivate Web of Science, Science Citation Index Expanded

JOURNAL FOCUS

Emergency medicine is a specialty which closely reflects societal challenges and consequences of public policy decisions. The emergency department specifically deals with social injustice, health and economic disparities, violence, substance abuse, and disaster preparedness and response. This journal focuses on how emergency care affects the health of the community and population, and conversely, how these societal challenges affect the composition of the patient population who seek care in the emergency department. The development of better systems to provide emergency care, including technology solutions, is critical to enhancing population health.

Table of Contents

186

191

197

Virtual Interviews and the Pediatric Emergency Medicine Match Geography: A National Survey Aline Baghdassarian, Jessica A. Bailey, Derya Caglar, Michelle Eckerle, Andrea Fang, Katherine McVety, Thuy Ngo, Jerri A. Rose, Cindy Ganis Roskind, Melissa M. Tavarez, Frances Turcotte Benedict, Joshua Nagler, Melissa L. Langhan

Analysis of Anonymous Student Narratives About Experiences with Emergency Medicine Residency Programs

Molly Estes, Jacob Garcia, Ronnie Ren, Mark Olaf, Shannon Moffett, Michael Galuska, Xiao Chi Zhang

Rapid Cycle Deliberate Practice Training for Simulated Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in Resident Education

Jaron D. Raper, Charles A. Khoury, Anderson Marshall, Robert Smola, Zachary Pacheco, Jason Morris, Guihua Zhai, Stephanie Berger, Ryan Kraemer, Andrew D. Bloom

205

209

213

221

Simulation Improves Emergency Medicine Residents’ Clinical Performance of Aorta Point-of-Care Ultrasound

Brandon M. Wubben, Cory Wittrock

Foundations of Emergency Medicine: Impact of a Standardized, Open-access, Core Content Curriculum on In-Training Exam Scores

Jaime Jordan, Natasha Wheaton, Nicholas D. Hartman, Dana Loke, Nathaniel Shekem, Anwar Osborne, P. Logan Weygandt, Kristen Grabow Moore

Integrating Hospice and Palliative Medicine Education Within the American Board of Emergency Medicine Model

Rebecca Goett, Jason Lyou, Lauren R. Willoughby, Daniel W. Markwalter, Diane L. Gorgas, Lauren T. Southerland

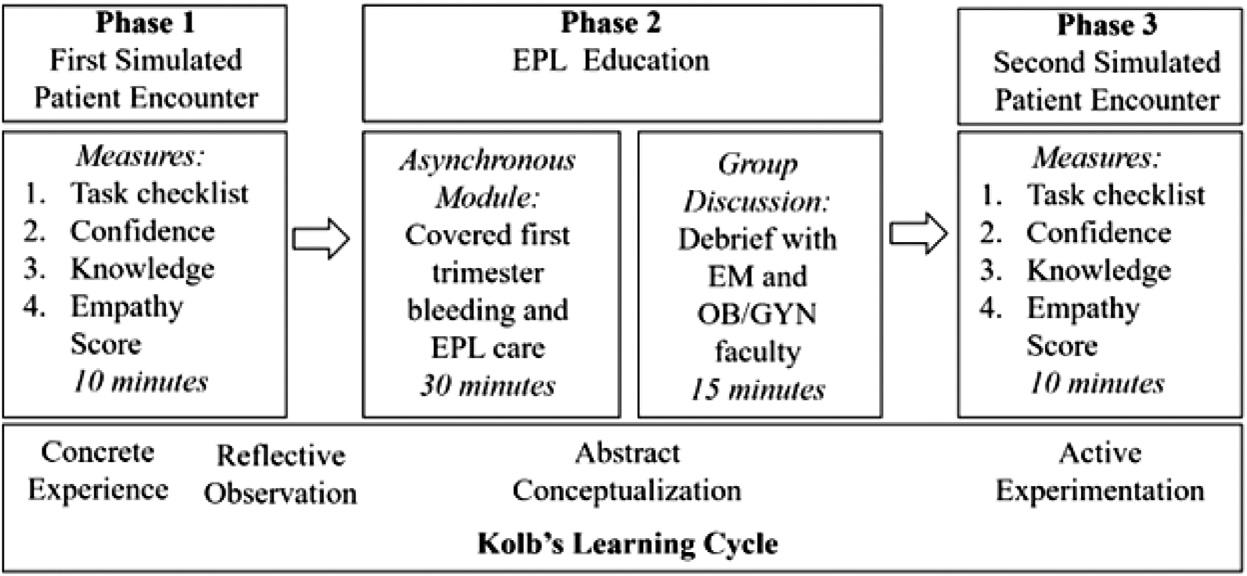

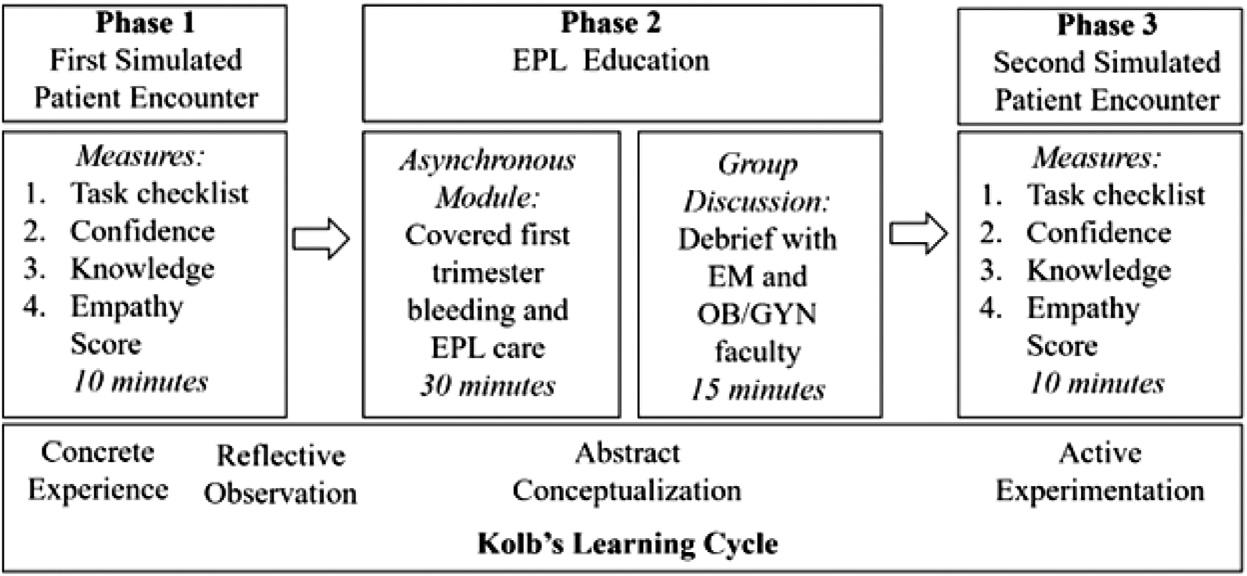

The Effect of a Simulation-based Intervention on Emergency Medicine Resident Management of Early Pregnancy Loss

Shawna D. Bellew, Erica Lowing, Leah Holcomb

Emergency Department Operations

226 Root Cause Analysis of Delayed Emergency Department Computed Tomography Scans Arjun Dhanik, Bryan A. Stenson, Robin B. Levenson, Peter S. Antkowiak, Leon D. Sanchez, David T. Chiu

Geriatrics

230 Usability of the 4Ms Worksheet in the Emergency Department for Older Patients: A Qualitative Study Mackenzie A. McKnight, Melissa K. Sheber, Daniel J. Liebzeit, Aaron T. Seaman, Erica K. Husser, Harleah G. Buck, Heather S. Reisinger, Sangil Lee

Volume 25, No. 2: March 2024 iii Western Journal of Emergency Medicine

for peer review, author instructions, conflicts of interest and human and animal subjects protections can be found

at www.westjem.com.

Policies

online

Western Journal of Emergency Medicine:

Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health

Indexed in MEDLINE, PubMed, and Clarivate Web of Science, Science Citation Index Expanded

Table of Contents continued

Pediatrics

237 National Characteristics of Emergency Care for Children with Neurologic Complex Chronic Conditions

Kaileen Jafari, Kristen Carlin, Derya Caglar, Eileen J. Klein, Tamara D. Simon

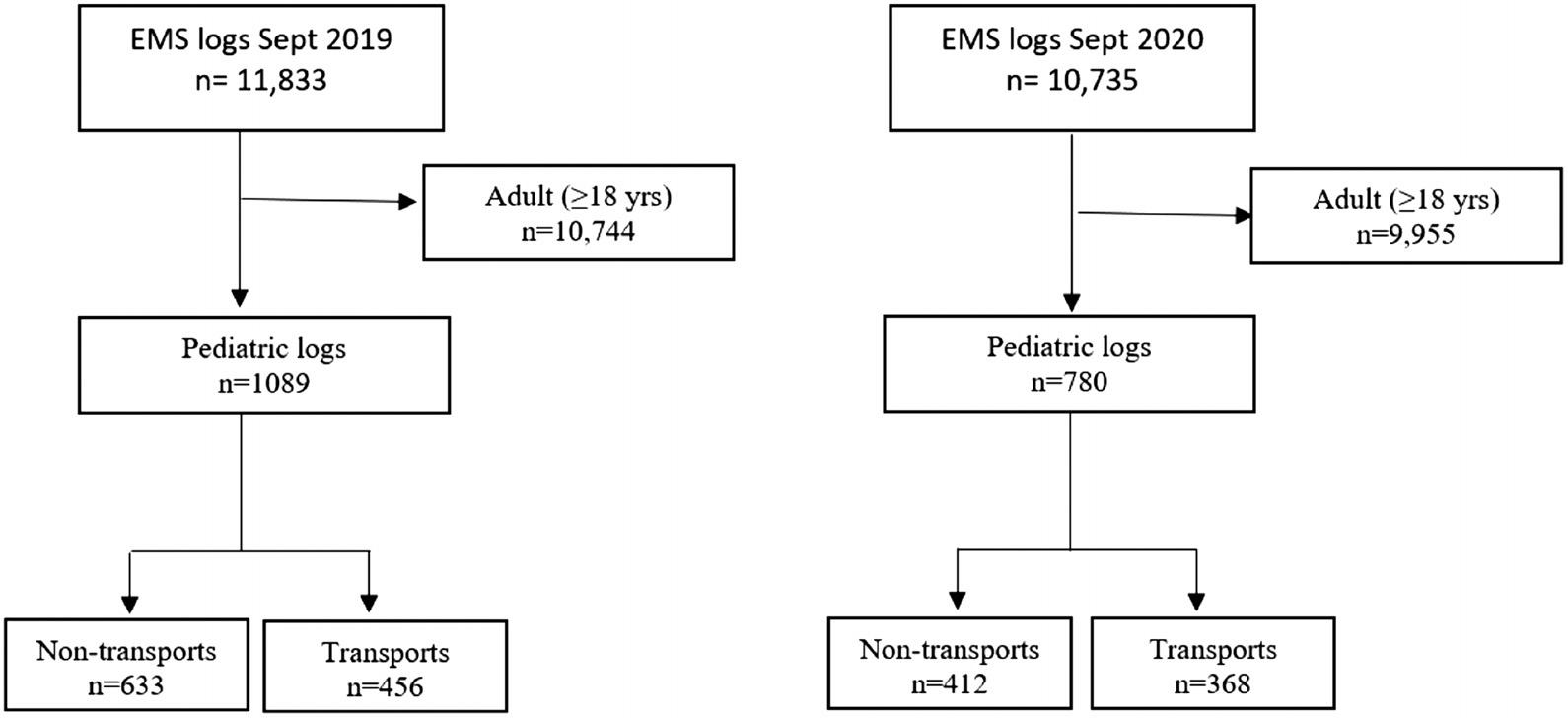

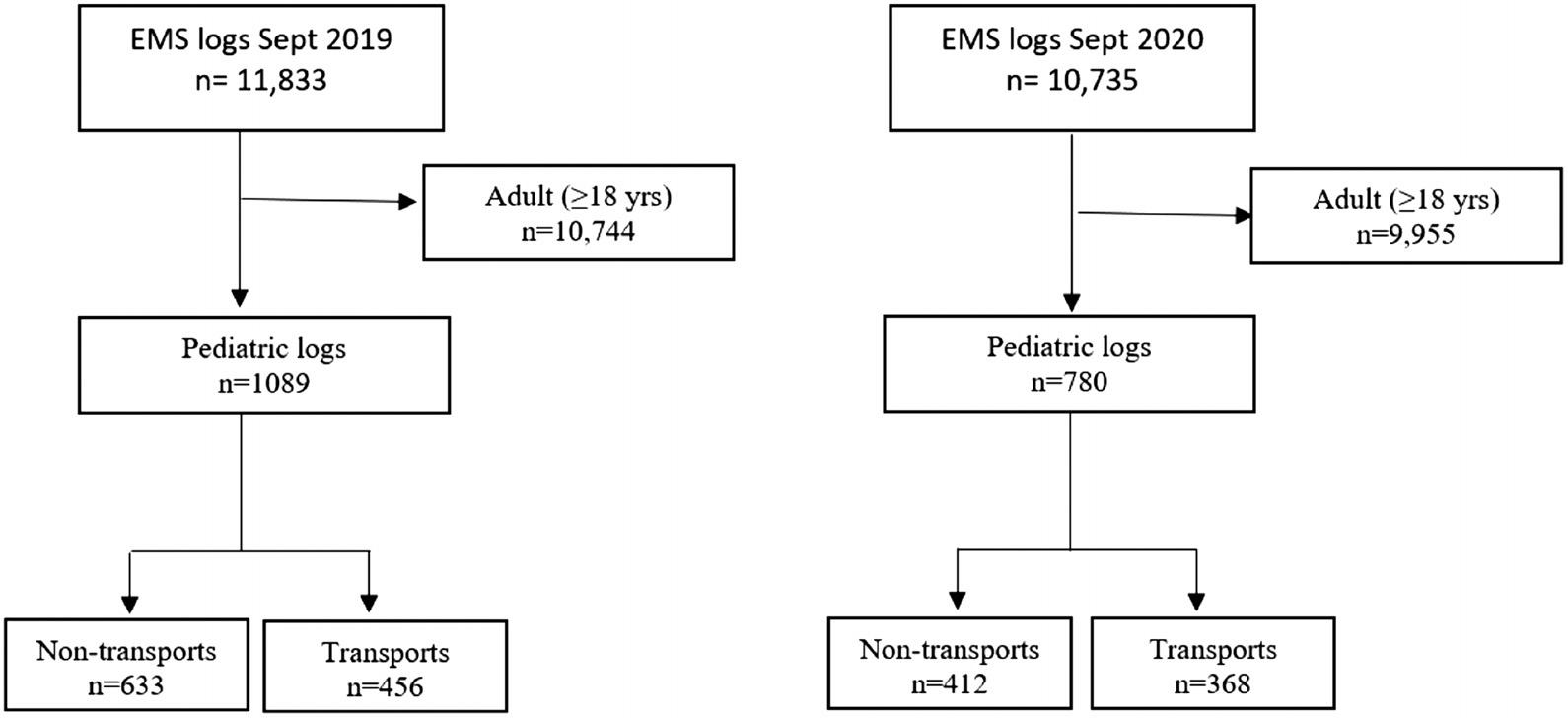

246 Pediatric Outcomes of Emergency Medical Services Non-Transport Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Lori Pandya, Brandon Morshedi, Brian Miller, Halim Hennes, Mohamed Badawy

Research Methodology

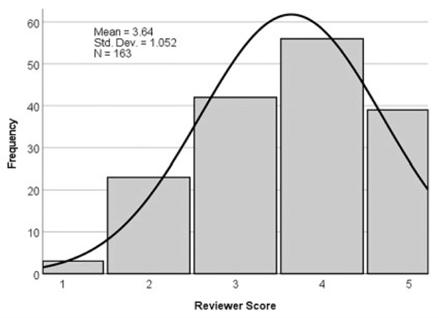

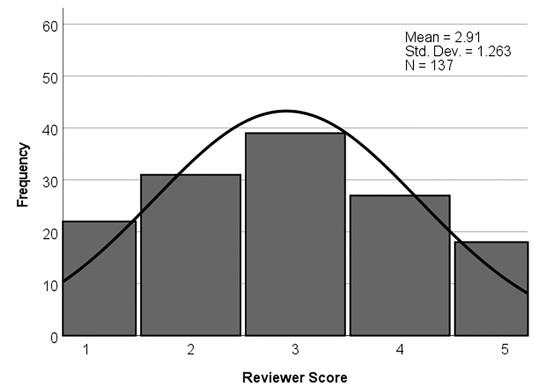

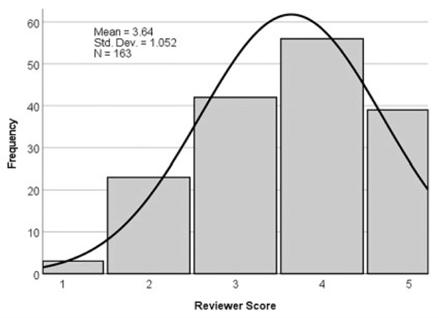

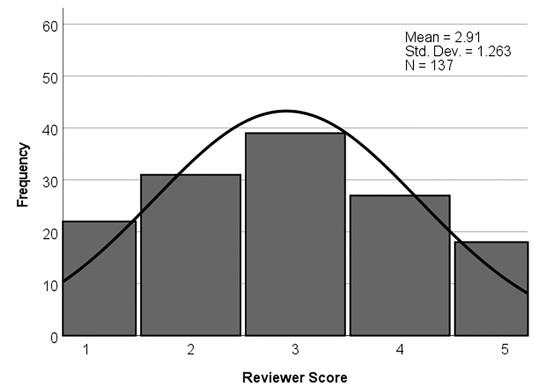

254 Development and Validation of a Scoring Rubric for Editorial Evaluation of Peer-review Quality: A Pilot Study

Jeffrey N. Love, Anne M. Messman, Jonathan S. Ilgen, Chris Merritt, Wendy C. Coates, Douglas S. Ander, David P. Way

Ultrasound

264 Novel Scoring Scale for Quality Assessment of Lung Ultrasound in the Emergency Department

Jessica R. Balderston, Taylor Brittan, Bruce J. Kimura, Chen Wang, Jordan Tozer

268 Diagnostic Accuracy of a Handheld Ultrasound vs a Cart-based Model: A Randomized Clinical Trial

Ryan C. Gibbons, Daniel J. Jaeger, Matthew Berger, Mark Magee, Claire Shaffer, Thomas G. Costantino

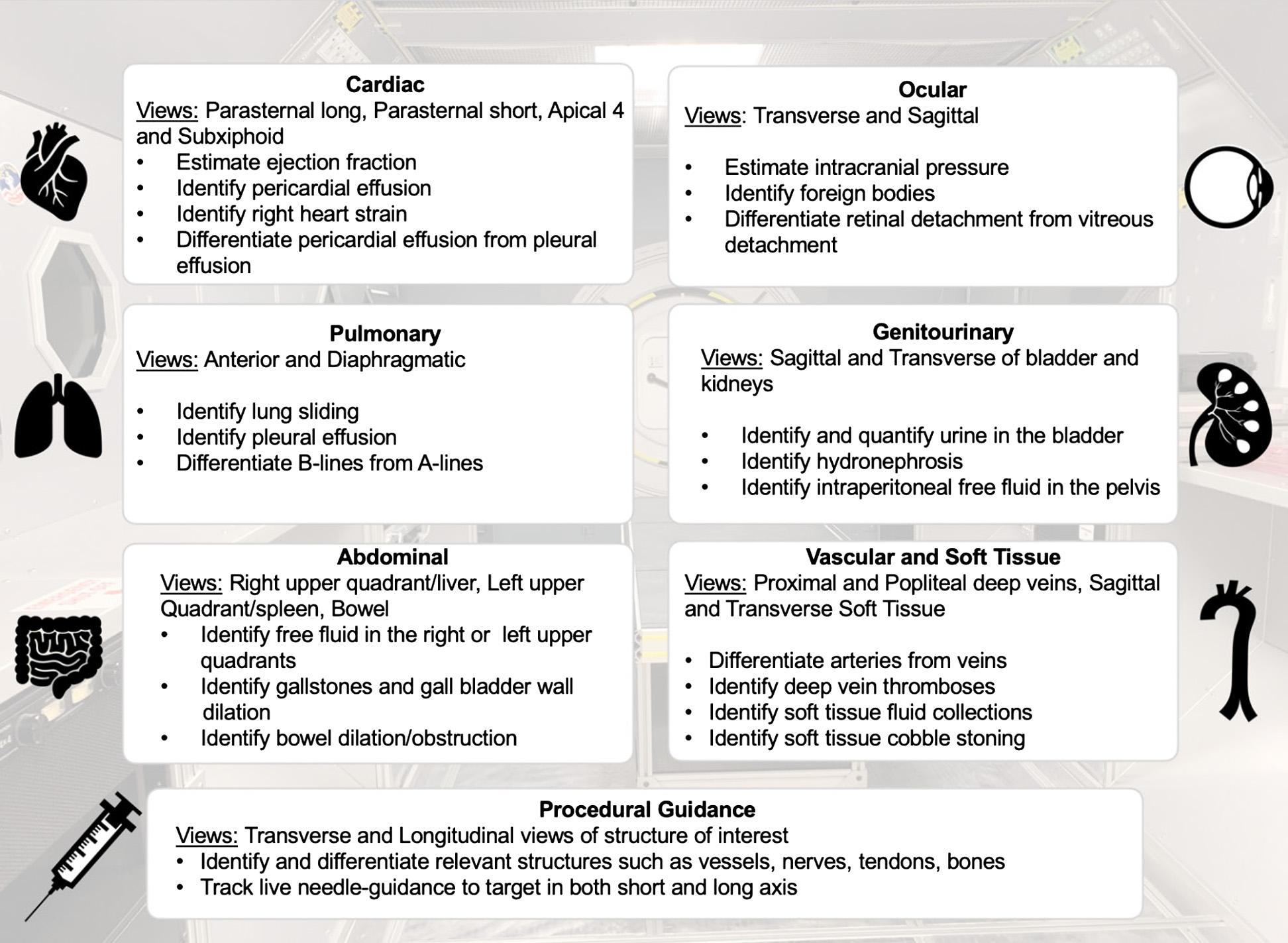

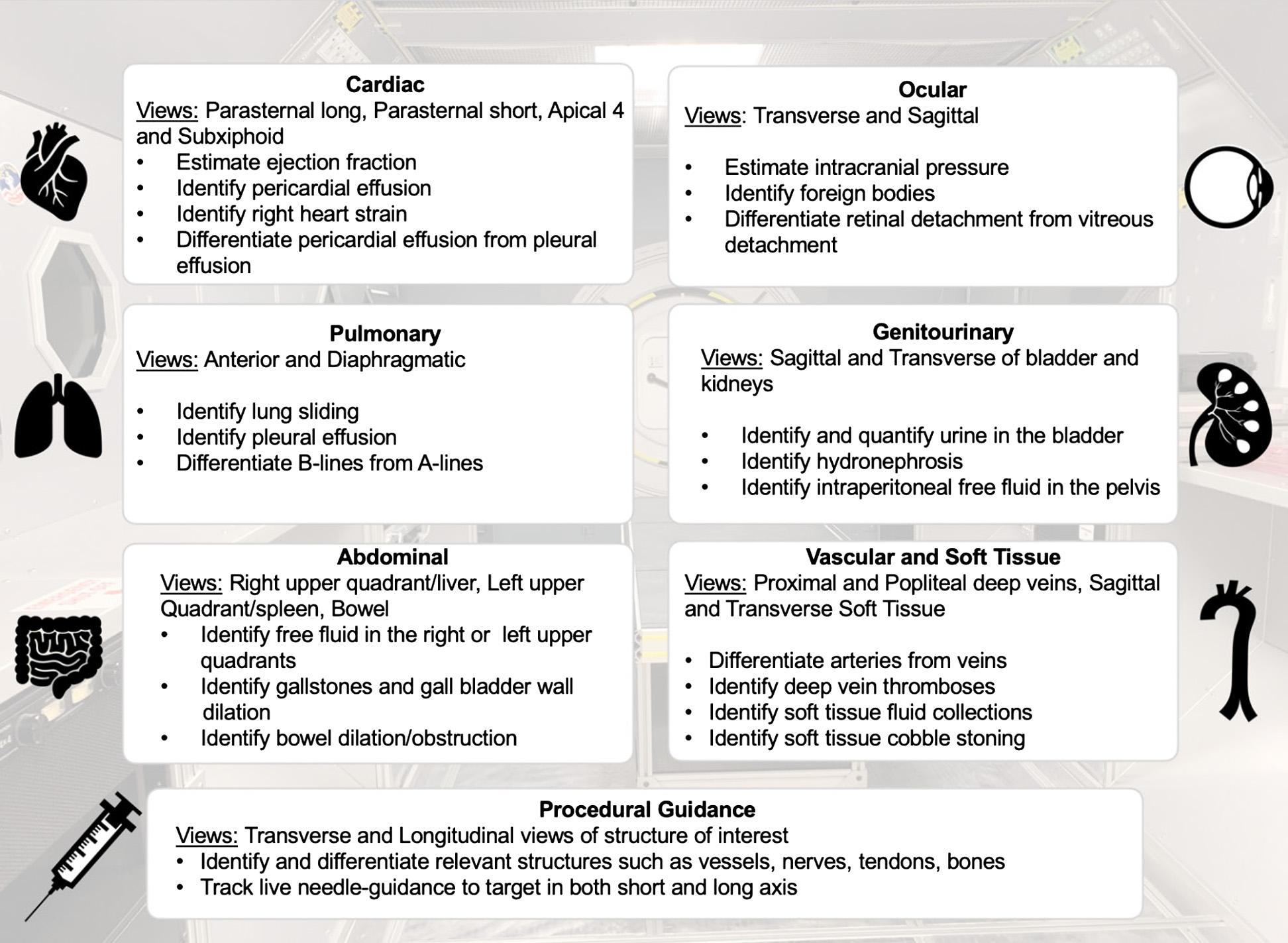

275 Space Ultrasound: A Proposal for Competency-based Ultrasound Training for In-flight Space Medicine Chanel Fischetti, Emily Frisch, Michael Loesche, Andrew Goldsmith, Ben Mormann, Joseph S. Savage, Roger Dias, Nicole Duggan

282 Ultrasound Performed by Emergency Physicians for Deep Vein Thrombosis: A Systematic Review

Daniel Hercz, Oren J. Mechanic, Marcia Varella, Francisco Fajardo, Robert L. Levine

Women’s Health

291 User Experience of Access to Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner and Emergency Contraception in Emergency Departments in the United States: A National Survey

Colleen Cowdery, Diana Halloran, Rebecca Henderson, MA Kathleen M. Allen, Kelly O’Shea, Kristen Woodward, Susan Rifai, Scott A. Cohen, Muhammad Abdul Baker Chowdhury, Cristina Zeretzke-Bien, Lauren A. Walter, Marie-Carmelle Elie-Turenne

Letters to the Editor

301 Factors Associated with Overutilization of Computed Tomography Cervical Spine Imaging

Tessy La Torre Torres, Jonathan McGhee

302 Reply to “Factors Associated with Overutilization of Computed Tomography Cervical Spine Imaging” Karl Chamberlin

Western Journal of Emergency Medicine iv Volume 25, No. 2: March 2024

Western Journal of Emergency Medicine:

Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health

This open access publication would not be possible without the generous and continual financial support of our society sponsors, department and chapter subscribers.

Professional Society Sponsors

American College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians

California American College of Emergency Physicians

Academic Department of Emergency Medicine Subscriber

Albany Medical College Albany, NY

Allegheny Health Network Pittsburgh, PA

American University of Beirut Beirut, Lebanon

AMITA Health Resurrection Medical Center Chicago, IL

Arrowhead Regional Medical Center Colton, CA

Baylor College of Medicine Houston, TX

Baystate Medical Center Springfield, MA

Bellevue Hospital Center New York, NY

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Boston, MA

Boston Medical Center Boston, MA

Brigham and Women’s Hospital Boston, MA

Brown University Providence, RI

Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center Fort Hood, TX

Cleveland Clinic Cleveland, OH

Columbia University Vagelos New York, NY

State Chapter Subscriber

Arizona

Florida

International

Lebanese

California Chapter Division of American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Conemaugh Memorial Medical Center Johnstown, PA

Crozer-Chester Medical Center Upland, PA

Desert Regional Medical Center Palm Springs, CA

Detroit Medical Center/ Wayne State University Detroit, MI

Eastern Virginia Medical School Norfolk, VA

Einstein Healthcare Network Philadelphia, PA

Eisenhower Medical Center Rancho Mirage, CA

Emory University Atlanta, GA

Franciscan Health Carmel, IN

Geisinger Medical Center Danville, PA

Grand State Medical Center Allendale, MI

Healthpartners Institute/ Regions Hospital Minneapolis, MN

Hennepin County Medical Center Minneapolis, MN

Henry Ford Medical Center Detroit, MI

Henry Ford Wyandotte Hospital Wyandotte, MI

INTEGRIS Health Oklahoma City, OK

Kaiser Permenante Medical Center San Diego, CA

Kaweah Delta Health Care District Visalia, CA

Kennedy University Hospitals Turnersville, NJ

Kent Hospital Warwick, RI

Kern Medical Bakersfield, CA

Lakeland HealthCare St. Joseph, MI

Lehigh Valley Hospital and Health Network Allentown, PA

Loma Linda University Medical Center Loma Linda, CA

Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center New Orleans, LA

Louisiana State University Shreveport Shereveport, LA

Madigan Army Medical Center Tacoma, WA

Maimonides Medical Center Brooklyn, NY

Maine Medical Center Portland, ME

Massachusetts General Hospital/Brigham and Women’s Hospital/ Harvard Medical Boston, MA

Mayo Clinic Jacksonville, FL

Mayo Clinic College of Medicine Rochester, MN

Mercy Health - Hackley Campus Muskegon, MI

Merit Health Wesley Hattiesburg, MS

Midwestern University Glendale, AZ

Mount Sinai School of Medicine New York, NY

New York University Langone Health New York, NY

North Shore University Hospital Manhasset, NY

Northwestern Medical Group Chicago, IL

NYC Health and Hospitals/ Jacobi New York, NY

Ohio State University Medical Center Columbus, OH

Ohio Valley Medical Center Wheeling, WV

Oregon Health and Science University Portland, OR

Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center Hershey, PA

Mediterranean Academy of Emergency Medicine

To become a WestJEM departmental sponsor, waive article processing fee, receive electronic copies for all faculty and residents, and free CME and faculty/fellow position advertisement space, please go to http://westjem.com/subscribe or contact:

Stephanie Burmeister

WestJEM Staff Liaison

Phone: 1-800-884-2236

Email: sales@westjem.org

Volume 25, No. 2: March 2024 v Western Journal of Emergency Medicine

Society Partners

Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

California

Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Lakes

of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Great

Chapter Division

Tennessee

Emergency Medicine Association of Turkey

Academy of Emergency Medicine

Norwegian Society for Emergency Medicine Sociedad Argentina de Emergencias

Sociedad Chileno Medicina Urgencia Thai Association for Emergency Medicine

Uniformed Services Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Virginia Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Indexed in MEDLINE, PubMed,

Index Expanded

and Clarivate Web of Science, Science Citation

Western Journal of Emergency Medicine:

This open access publication would not be possible without the generous and continual financial support of our society sponsors, department and chapter subscribers.

Professional Society Sponsors

American College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians

California American College of Emergency Physicians

Academic Department of Emergency Medicine Subscriber

Prisma Health/ University of South Carolina SOM Greenville Greenville, SC

Regions Hospital Emergency Medicine Residency Program St. Paul, MN

Rhode Island Hospital Providence, RI

Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital New Brunswick, NJ

Rush University Medical Center Chicago, IL

St. Luke’s University Health Network Bethlehem, PA

Spectrum Health Lakeland St. Joseph, MI

Stanford Stanford, CA

SUNY Upstate Medical University Syracuse, NY

Temple University Philadelphia, PA

Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center El Paso, TX

The MetroHealth System/ Case Western Reserve University Cleveland, OH

UMass Chan Medical School Worcester, MA

University at Buffalo Program Buffalo, NY

State Chapter Subscriber

University of Alabama Medical Center Northport, AL

University of Alabama, Birmingham Birmingham, AL

University of Arizona College of Medicine-Tucson Tucson, AZ

University of California, Davis Medical Center Sacramento, CA

University of California, Irvine Orange, CA

University of California, Los Angeles Los Angeles, CA

University of California, San Diego La Jolla, CA

University of California, San Francisco San Francisco, CA

UCSF Fresno Center Fresno, CA

University of Chicago Chicago, IL

University of Cincinnati Medical Center/ College of Medicine Cincinnati, OH

University of Colorado Denver Denver, CO

University of Florida Gainesville, FL

University of Florida, Jacksonville Jacksonville, FL

California Chapter Division of American Academy of Emergency Medicine

University of Illinois at Chicago Chicago, IL

University of Iowa Iowa City, IA

University of Louisville Louisville, KY

University of Maryland Baltimore, MD

University of Massachusetts Amherst, MA

University of Michigan Ann Arbor, MI

University of Missouri, Columbia Columbia, MO

University of North Dakota School of Medicine and Health Sciences Grand Forks, ND

University of Nebraska Medical Center Omaha, NE

University of Nevada, Las Vegas Las Vegas, NV

University of Southern Alabama Mobile, AL

University of Southern California Los Angeles, CA

University of Tennessee, Memphis Memphis, TN

University of Texas, Houston Houston, TX

University of Washington Seattle, WA

University of WashingtonHarborview Medical Center Seattle, WA

University of Wisconsin Hospitals and Clinics Madison, WI

UT Southwestern Dallas, TX

Valleywise Health Medical Center Phoenix, AZ

Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center Richmond, VA

Wake Forest University Winston-Salem, NC

Wake Technical Community College Raleigh, NC

Wayne State Detroit, MI

Wright State University Dayton, OH

Yale School of Medicine New Haven, CT

International

Lebanese

Mediterranean

To become a WestJEM departmental sponsor, waive article processing fee, receive electronic copies for all faculty and residents, and free CME and faculty/fellow position advertisement space, please go to http://westjem.com/subscribe or contact:

Stephanie Burmeister

WestJEM Staff Liaison

Phone: 1-800-884-2236

Email: sales@westjem.org

Western Journal of Emergency Medicine vi Volume 25, No. 2: March 2024

Society Partners

Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine California Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Lakes Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Arizona

Florida

Great

Tennessee

Emergency Medicine Association of Turkey

Academy of Emergency Medicine

Academy of Emergency Medicine Norwegian Society for Emergency Medicine Sociedad Argentina de Emergencias

Sociedad Chileno Medicina Urgencia Thai Association for Emergency Medicine

Medicine

Uniformed Services Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine Virginia Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency

Integrating Emergency

Population

Indexed in MEDLINE, PubMed, and Clarivate Web of Science, Science Citation Index Expanded

Care with

Health

Save the Date Spring Seminar 2024 | April 27 - May 1 Signia Orlando Bonnet Creek • Orlando, Florida #ACOEP24

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

CharacteristicsforLow,HighandVeryHighEmergency DepartmentUseforMentalHealthDiagnosesfromHealth RecordsandStructuredInterviews

Marie-JoséeFleury,PhD*†

ZhirongCao,MSc†

GuyGrenier,PhD†

*McGillUniversity,DepartmentofPsychiatry,Montreal,Canada

† DouglasMentalHealthUniversityResearchCentre,Montreal,Canada

SectionEditors:BradBobrin,MD,andYaninaPurim-Shem-Tov,MD,MS

Submissionhistory:SubmittedMay24,2023;RevisionreceivedNovember17,2023;AcceptedNovember22,2023

ElectronicallypublishedFebruary9,2024

Fulltextavailablethroughopenaccessat http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

DOI: 10.5811/westjem.18327

Introduction: Patientswithmentalhealthdiagnoses(MHD)areamongthemostfrequentemergency department(ED)users,suggestingtheimportanceofidentifyingadditionalfactorsassociatedwiththeir EDusefrequency.Inthisstudyweassessedvariouspatientsociodemographicandclinical characteristics,andserviceuseassociatedwithlowEDusers(1–3visits/year),comparedtohigh(4–7) andveryhigh(8+)EDuserswithMHD.

Methods: OurstudywasconductedinfourlargeQuebec(Canada)EDnetworks.Atotalof299patients withMHDwererandomlyrecruitedfromtheseEDin2021–2022.Structuredinterviewscomplemented datafromnetworkhealthrecords,providingextensivedataonparticipantprofilesandtheirqualityof care.WeusedmultivariablemultinomiallogisticregressiontocomparelowEDusetohighandveryhigh EDuse.

Results: Overa12-monthperiod,39%ofpatientswerelowEDusers,37%high,and24%veryhighED users.ComparedwithlowEDusers,thoseatgreaterprobabilityforhighorveryhighEDuseexhibited moreviolent/disturbedbehaviorsorsocialproblems,chronicphysicalillnesses,andbarrierstounmet needs.Patientspreviouslyhospitalized1–2timeshadlowerriskofhighorveryhighEDusethanthose notpreviouslyhospitalized.ComparedwithlowEDusers,highandveryhighEDusersshowedhigher prevalenceofpersonalitydisordersandsuicidalbehaviors,respectively.Womenhadgreaterprobability ofhighEDusethanmen.PatientslivinginrentalhousinghadgreaterprobabilityofbeingveryhighED usersthanthoselivinginprivatehousing.Usingatleast5+ primarycareservicesandbeingrecurrentED userstwoyearspriortothelastyearofEDusehadincreasedprobabilityofveryhighEDuse.

Conclusion: FrequencyofEDusewasassociatedwithcomplexissuesandhigherperceived barrierstounmetneedsamongpatients.VeryhighEDusershadmoresevererecurrentconditions,such asisolationandsuicidalbehaviors,despiteusingmoreprimarycareservices.Results suggestedsubstantialreductionofbarrierstocareandimprovementonbothaccessandcontinuity ofcareforthesevulnerablepatients,integratingcrisisresolutionandsupportedhousing services.Limitedhospitalizationsmaysometimesbeindicated,protectingagainstED use.[WestJEmergMed.2024;25(2)144–154.]

Keywords: emergencydepartment;frequencyofemergencydepartmentvisits;lowserviceusers; highserviceusers;veryhighserviceusers;mentalhealthdiagnoses;probabilityfactors; associatedvariables.

WesternJournal of EmergencyMedicineVolume25,No.2:March2024 144

INTRODUCTION

Emergencydepartment(ED)crowdingisamajor impedimenttotheefficacyofhealthcaresystems,1 causedin partbyaminorityofpatientswhousetheEDfrequently.2

Accordingtoa2019systematicreview,theestimated prevalenceofhighEDuserswas4-16%,yetthesepatients accountedfor14–47%ofallEDvisits,averaging6.9ED visitsperyear.3 HighEDusers,commonlydefinedashaving 4+ EDvisitsina12-monthperiod,4,5 aremorelikelythan otherpatientstobehospitalizedfrequently6 andhave2.2 timesgreaterprobabilityofdeaththanotherEDusers accordingtoa2015systematicreview.7 Mentalhealth diagnoses(MHD),includingsubstance-relateddisorders (SRD),areveryprevalentamonghighEDusers.1,4,8 Another 2013reviewreportedthatbetween0.3–18%ofpatientswith MHDwerefrequentEDusers.8 A2019Canadianstudy showedthatQuebecpatientswithMHDhadusedtheED roughlytwiceasoftenaspatientswithoutMHD,and17%of thesepatientswerehighEDusersin2015-16.9 AstheEDis notanappropriatesettingfortreatingrecurrentpatientswith MHD,theidentificationofhighEDusersandtheir characteristicsiskeytoimprovingcareamongthese vulnerablepatientsandforreducingcrowdingand healthcarecostsintheED,giventhatEDuseisoneofthe costliestcomponentsofhealthcare.10

Severalstudieshaveassessedpatientcharacteristics associatedwithhighEDuseamongpatientswithMHD, mostcomparinghighEDusersvsotherEDusers.11–17 The sociodemographiccharacteristicsdistinguishinghighED usersfromotherEDusersincludedbeingmale,15 younger, 14 single,16 havingpublichealthinsurance,11,12 andlivingin moresociallyormateriallydeprived15,18 ormetropolitan15 areas.Personalitydisorders,11,13,15,16 seriousMHD15,17 or SRD,5,17 andhavingchronicphysicalillnesses12 werethe mainclinicalcharacteristicsassociatedwithhighEDuse. HighEDusersalsodifferedfromotherEDusersintermsof higheroveralluseofmentalhealthservices.15,19,20 Toour knowledge,fewstudieshavecomparedsubgroupsoflow, high,andveryhighEDusersamongpatients.1,21 Those studieshavefocusedonMHDtoexplainthefrequencyof EDuse,includingpatientswithmultipleconditionsand withSRD,asthemainfactorleadingtoincreaseduse. VeryhighEDusersalsoreportedmorerecurrentEDusein previousyears.22 Yet,howthefrequencyofEDusewas categorizeddifferedgreatlyamongthesestudies: “veryhighEDuse” couldbeanywherebetween 8+1 and18+ visits/year.21

Abetterunderstandingofpatientcharacteristics associatedwithlow,high,andveryhighEDusersmayhelp tailorinterventionsandprogramstoEDprofilesandreduce EDuse,particularlyforhighandveryhighusers.Wefound nopreviousresearchcomparinglowEDuserstohighand veryhighusersamongpatientswithMHDorSRD.Also, moststudieswerebasedsolelyonsingle-sitehospitalhealth

PopulationHealthResearchCapsule

Whatdowealreadyknowaboutthisissue?

Emergencydepartment(ED)crowdingisa majorimpedimenttotheef fi cacyof healthcaresystems,causedinpartby aminorityofpatientswhousethe EDfrequently.

Whatwastheresearchquestion?

Wesoughttoassesspatients ’ characteristics andserviceusepatternsassociatedwithlow, highandveryhighEDusers.

Whatwasthemajor findingofthestudy?

Violent/disturbedbehaviorsorsocial problemsincreased5.55timestheprobability ofveryhighEDuse.

Howdoesthisimprovepopulationhealth?

Areductionofbarrierstocareandbetter accessandcontinuityofoutpatientcare shouldbeprovidedforthemost vulnerablepatients.

records.Ourstudyisoriginalinthatitintegratespatient structuredinterviewswithhealthrecordsfromfourlarge mentalhealthnetworksthatincludehospitalsand community-basedservices.VeryfewstudiesonEDuse integrateoveralloutpatientserviceuse,fromprimaryto specializedcare,andassesshowtheseservicesrelateto patientEDusefrequency.22 Moreover,fewstudieshave testedassociationsbetweenEDusefrequencyandquality ofoutpatientcareormotivationalbehaviors,suchas satisfactionwithcare,unmetneedsorperceivedstigma thatmaytriggerEDuse.

Basedontheliterature,wehypothesizedthatveryhigh EDusers,followedbyhighEDusers,wouldbemorelikely thanlowEDuserstohavecomplexhealthandsocialissues andunmetneeds,andtouseoutpatientcaremorefrequently. Weassessedvariouspatientsociodemographicandclinical characteristics,andserviceusepatternsassociatedwithlow EDuserswithMHD(1–3visits/year),comparedwithhigh EDusers(4–7visits)andveryhighEDusers(8+ visits)in fourlargeEDnetworksinQuebec(Canada).

METHODS

DescriptionoftheQuebecMentalHealthSystem

InCanada,allresidentsarecoveredbyauniversalhealth insurancemanagedattheprovinciallevel.23 Mentalhealth

Volume25,No.2:March2024WesternJournal of EmergencyMedicine 145

Fleuryetal.

PatientCharacteristicsAssociatedwithEDUseforMHD

services,includingmedication,aremainlypublic,except servicessuchaspsychologicalservices,whichareusually paidbytheuserorcoveredbysomeemployers.Quebec publichealthcareservicesaremainlymanagedthrough22 largenetworks,integratinghospitals,long-termand addictionfacilities,andcommunityhealthcarecenters.24 In thesenetworks,specializedmentalhealthcareisprovidedin psychiatricdepartmentsofgeneralhospitalsorinpsychiatric hospitals,orinspecializedaddictiontreatmentcenters.25 HospitalEDstaffincludespecializedorgeneralemergency physicians,psychiatrists,andpsychosocialclinicians mostlynursesandsomesocialworkersandaddiction specialists.Primarymentalhealthcareisofferedinmedical clinicsstaffedbygeneralpractitioners,incommunity healthcarecentersmainlyprovidingpsychosocialservices, andbypsychologistsmostlyworkinginprivatepractice. Community-basedorganizations,thevoluntarysector, integratecrisisandsuicidepreventioncenters,detoxcenters, andpeersupportgroups.

StudySettingsandDataCollection

ThestudywasconductedinfourEDnetworksserving abouttwomillionpeople roughlyone-fourthofQuebec’ s population.StudyparticipantshadtobeEDusers,18+ years old,abletocompleteastructuredinterview,knowFrenchor English,andhadtogranttheresearchteamaccesstotheir healthrecords.Studyparticipantswererecruitedrandomly byEDstaffbasedonahealthrecordlistof1,751EDusers whohadMHD,includingSRD,andhadusedtheEDatleast oncewithinthefourEDnetworksinthe12monthspreceding recruitment.Ofthe first563eligiblepatientsreached,450 (80%)agreedtobereferredtotheresearchteamfor considerationasstudyparticipants.Theywerethen contactedbytheresearchcoordinatorandaskedtotakepart inastructuredtelephoneinterview,donebytrained interviewerscloselymonitoredbytheresearchteam.

TheseinterviewswereadministeredbetweenMarch1, 2021–May13,2022.Averagecompletiontimewas45 minutes.Healthrecordsforthe12monthspriortointerviews werecollectedtocomplementinterviewdata,exceptfor previousEDuse,whichwasmeasuredwithinthetwoyears priortothelastyearofEDuse.Healthrecordsdata concernedEDuse(Banquededonnéescommunesdes urgences[BDCU]database),psychiatricoutpatientservices used,hospitalization(MED-ÉCHOdatabase),and psychosocialservicesfromcommunityhealthcarecenters(ICLSCdatabase).PatientdiagnoseswereincludedinBDCU andMED-ÉCHO,andframedbytheInternational ClassificationofDiseases,Canada,10th Rev(Appendix).All healthrecordsincludedinformationonpatientserviceuse (eg,type,frequency)butexclusivelywithintheEDnetwork. Validatedbyasteeringcommitteeintegratingclinicians, structuredinterviewdataconsideredserviceuseoutsideED networksandservicesnotincludedinhealthrecords

(eg,medicalclinics,psychologists).Thesemergeddata allowedforabroaddatasetonpatientserviceuseandother patientcharacteristicspriortorecruitment.Participationin thestudywasvoluntary.Patientswhoprovidedconsent receivedamodest financialcompensation.Themultisite protocolwasapprovedbytheethicsreviewboardofthe DouglasMentalHealthUniversityInstitute.

StudyVariables

ThedependentvariablewasEDusefrequencyformental healthreasonsamongpatientswithMHD,measured12 monthspriortointerviews.Patientswerecategorizedaslow EDusers(1–3visits/year),highEDusers(4–7visits/year)or veryhighEDusers(8+ visits/year).Thestandarddefinition ofhighEDuseis4+ times/year,11,12,26 whileveryhighuse wasdefinedas8+ times/yearbasedonprevious1,27 studies andonaminimaldistributionofveryhighEDvisitsinthe studysample.Independentvariablesweresociodemographic characteristics,clinicalcharacteristics,andserviceuse patterns,againbasedonpreviousresearch.21,28

Sociodemographiccharacteristicsincludedthefollowing: sex;agegroup;educationlevel;civilstatus;employment status(eg,worker,unemployed);householdincome($Can); typeofhousing(eg,supervised);numberofsignificantsocial supportnetwork;andstigma.Allexcept “ agegroup ” were determinedbyinterviewdata.BasedontheCanadian CommunityHealthSurvey(CCHS),socialsupportwas measuredwiththefollowingquestion: “Doyouhaveoneor morepeoplearoundyouonwhomyoucanrelyforhelpwith problems?Ifyes,howmanypeople?” Alsobasedonthe CCHS,ona5-pointscale,withresponsesrangingfrom “totallydisagree” to “totallyagree” (greatest stigmatization),stigmawasmeasuredwiththefollowing affirmation: “Mostpeopleinmycommunitytreataperson withaMHDorSRDinthesamemannerastheywouldtreat anyotherperson.”

Clinicalcharacteristicsincludedthefollowing:MHD; SRD;suicidalbehaviors(suicideideationorattempt); violent/disturbedbehaviorsorsocialproblems;chronic physicalillnesses(eg,heartdiseases,diabetes);co-occurring MHD-SRD;andhightriagepriorityamongEDusers.All thesevariableswerebasedonhealthrecords,exceptSRD, whichwasbasedonbothhealthrecordsandthestructured interviews.TheMHDincludedseriousMHD(schizophrenia spectrumandotherpsychoticdisorders,andbipolar disorders),personalitydisorders,andcommonMHD (anxiety,depressiveandadjustmentdisorders;attention deficit/hyperactivitydisorder).TheSRDintegratedalcoholanddrug-relateddisorders(use,induced,intoxicationand withdrawal),measuredusinghealthrecordsalongwiththe AlcoholUseDisordersIdentificationTest29 andtheDrug AbuseScreeningTest-20.30 Thesewereincludedinthe structuredinterviews,asSRDareoftenunderdiagnosedin healthrecords.31 Weidentifiedchronicphysicalillnessesand

WesternJournal of EmergencyMedicineVolume25,No.2:March2024 146 PatientCharacteristicsAssociatedwithEDUseforMHD Fleuryetal.

theirseverity(0to2+)basedonanadaptedversion integratingboththeCharlsonandElixhausercomorbidity indexes.32 TheEDtriageprioritywasbasedontheCanadian TriageAcuityScale,33 consistingof fiveprioritylevelsor illnessseverity,withlevels4–5consideredtreatablein outpatientcare.33 Inthisstudy,hightriagepriorityEDuse (1–3)wasconsideredaproxyforfunctionaldisability,based onmeanofnumberofEDvisitsperpatient,with1–3triage prioritydividedbytotalofEDvisitsperpatient(1–5).

Patientserviceuseincludedthefollowing:knowledgeof mentalhealthoraddictionservices;havingafamilydoctoror otherregularcareclinician;frequencyofprimarycare, community-based,andspecializedoutpatientservicesused; overallsatisfactionwithoutpatientservicesused;numberof barriersrelatedtounmetneeds;frequencyofhospitalization, andfrequencyofpreviousEDuse.Patientserviceuseinthe EDnetworks,mostlymentalhealthspecializedcareand someprimarycareservices(communityhealthcarecenters), wasbasedonhealthrecords,andservicesoutsidetheED networkswerereportedinthestructuredinterviews mostly primarycare,community-based,orspecializedaddiction services.Serviceusemeasuredwithbothtypesofdata integratedonlythehighestfrequencyofserviceuse patientsreported.Asaproxyofcontinuityofcare,patients wereaskediftheywerefollowedregularlybyafamilydoctor orotherclinicians.Basedonapreviousstudy,34 the benchmarkforfrequentserviceuse,orminimalintensityof optimalcare,was5+ follow-upappointments/year.Primary careincludedservicesreceivedfromfamilydoctors,general practitionersinwalk-inclinics,psychologistsinprivate practice,andpsychosocialcliniciansincommunity healthcarecenters.

Community-basedorganizationsintegratedcrisisand suicidepreventioncenters,etc.Specializedoutpatientcare includedpsychiatricservices(eg,treatmentfrompsychiatrist teams,assertivecommunitytreatment,andintensivecase managementprograms),andservicesfromaddiction treatmentcenters.Patientswereaskedtoindicateona 5-pointscaletheiryearlysatisfactionwitheachoutpatient servicereceived.Wecalculatedthemeansatisfactionscore, withhigherscoresindicatinggreatersatisfaction.Unmet needsweremeasuredthroughthefollowingCCHSquestion:

“Couldyouexplainthereasonswhyservicesoutsideofthe EDdidnotrespondtoyourneeds?” includingmultiple choiceofbarrierstocare(eg, “Iprefertomanagebymyself;” “Thehelpisnotreadilyavailable”).Thenumberofbarriers wascountedas0,1–2,or3+.FrequencyofpreviousEDuse included4–7(highEDusers)and8+ EDvisits(veryhighED users),measuredforthetwo-yearperiodprecedingthe 12-monthinterviewperiod.

Analyses

Missingvalues(<1%)wereimputedbymeanfor continuousvariablesandmodeforcategoricalvariables.35

Descriptiveanalysesincludedpercentagesforcategorical variablesandmeanvaluesforcontinuousvariables.Weused bivariatemultinomiallogisticregressiontoexaminethe associationsbetweeneachindependentvariableandthe dependentvariable,frequencyofEDuse.Theintraclass correlationcoefficient(ICC)forthestudywassmall(<0.01), indicatinglowsharedvarianceamongpatientsfromtheED networks;multilevelanalysiswasnotrequired.Basedon criterionproceduresforforwardmodelselection, independentvariablesidentifiedassignificantinthebivariate analyses(Alpha:0.20)36 wereenteredsequentiallyintothe multivariablemultinomiallogisticregressionmodelfor frequencyofEDuse,withlowEDuse(1–3visits/year)asthe referencegroup.WeusedtheAkaikeInformationCriterion (AIC)37 tocomparetherelativegoodnessof fitamong differentmodelsbeforeselectingthe finalmultivariatemodel withthesmallestAICthatbest fitthedata.Wealsoused varianceinflationfactor(VIF)tomeasuretheamountof multicollinearityinregressionanalysisandfoundsmaller than4,indicatingthatmulticollinearitywasnotaconcern.38 Relativeriskratios(RRR)and95%confidenceintervals(CI) werecalculatedinthe finalmodel.Weperformedstatistical analysesusingStata17(StataCorpLLC,College Station,TX).

RESULTS

Ofthe450EDusersreferred,50couldnotbereachedand 300agreedtoparticipateinthestudy(75%responserate). Onepatientwaswithdrawn.Ofthe299patientsinthe final sample,amajority(55%)werewomen;39%were30–49years old,82%single,and57%unemployedorretired;47%hada householdincomeoflessthanCAN$20,000;57%hadpostsecondaryeducation,58%livedinrentalhousing,and50% perceivedhighstigma(Table1).Overhalf(57%)had commonMHD,44%seriousMHD,42%personality disorders,59%SRD,and45%chronicphysicalillnesses;38% hadco-occurringMHD-SRD,54%suicidalbehaviors,and 17%violent/disturbedbehaviorsorsocialproblems.Interms ofEDuse,39%werelowEDusers(1–3visits/year),37%high EDusers(4–7visits/year),and24%veryhighEDusers(8+ visits/year)(Table2).Nearlyhalf(46%)hadpoortofair knowledgeofmentalhealthoraddictionservices;88%hada familydoctor(74%)orotherregularcareclinician(58%).In thepreviousyear,58%hadused5+ primarycareservices, 26%5+ servicesfromcommunity-basedorganizations,and 65%5+ specializedoutpatientcare.Overallsatisfactionwith outpatientservicesaveraged4.02/5;37%ofparticipantshad unmetneeds,with15%identifying3+ barriers.Amajority (56%)werehospitalized,35%ofthose1–2times, and39%hadbeenveryhighEDusersovertheprevious two-yearperiod.

Wecomparedvariablesassociatedwithhighorveryhigh EDuserswithvariablesamonglowEDusers(Table 3). Womenhad1.30timesmoreprobabilityofbeinghighED

Volume25,No.2:March2024WesternJournal of EmergencyMedicine 147 Fleuryetal. PatientCharacteristicsAssociatedwithEDUseforMHD

Table1.

1Patientstructuredinterviews. 2Banquededonnéescommunesdesurgences (BDCU,EDdatabase). 3Thesamplewastoosmalltoseparate unemployedfromretired. 4Supervisedhousingincludedgrouphomes,residentialcare,supportedapartments,etc. 5Maintenanceet exploitationdesdonnéespourl’étudedelaclientèlehospitalière (MED-ÉCHO,hospitalizationdatabase). 6Patientsmayhavemorethan oneMHD. 7AlcoholUseDisordersIdenti ficationTest(AUDIT). 8DrugAbuseScreeningTest-20(DAST-20).Detailsofdiagnosticcodes arepresentedinthe Appendix ED,emergencydepartment.

Group LowED users(1–3 visits/year) HighED users(4–7 visits/year) Veryhigh EDusers (8+ visits/ year)Total Bivariate analysis 11739.1310936.457324.41299100 n%n%n%n% Size(N)meanSDmeanSDmeanSDmeanSD P-value Sociodemographiccharacteristics(measuredintheprevious12months) Women1 5345.36963.34358.916555.18 <0.20 Age2 18–29years3025.643633.032635.629230.77 <0.20 30–49years4841.034137.612838.3611739.13 50+ years3933.333229.361926.039030.1 Educationlevel1 Highschoolorless4841.035045.873243.8413043.48 ≥0.2 Post-secondaryeducation6958.975954.134156.1616956.52 Civilstatus1 Single(includingseparated, divorced,orwidowed) 9278.638981.656589.0424682.27 <0.20 Incouple2521.372018.35810.965317.73 Employmentstatus1 Workerorstudent5849.574137.613142.4713043.48 ≥0.20 Unemployedorretired3 5950.436862.384257.5316956.52 Householdincome (Can$/year)1 0–$19,9995446.155247.713547.9514147.16 <0.20 $20,000–$39,9993025.643834.862128.768929.77 $40,000+ 3328.211917.431723.296923.07 Typeofhousing1 Private2823.932522.9479.596020.07 <0.20 Rental6353.856357.84764.3817357.86 Supervised4 2622.222119.271926.036622.07 Numberofsignificantsocialsupportnetwork(mean/SD)1 3.523.193.615.083.635.403.584.51 ≥0.20 Stigma1 High5647.865651.383750.6814949.83 ≥0.20 Medium2319.661917.431216.445418.06 Low3832.483431.192432.889632.11 Clinicalcharacteristics(measuredintheprevious12months) Seriousmentalhealthdiagnoses(MHD)2,5,6 5547.014137.613750.6813344.48 <0.20 Personalitydisorders2,5,6 3126.505247.714460.2712742.47 <0.20 CommonMHD2,5,6 6152.146458.724460.2716956.52 ≥0.20 Substance-relateddisorders1,2,5,7,8 6252.996559.634865.7517558.53 <0.20 Suicidalbehaviors(suicideideationorattempt)2,5 4437.616357.805473.9716153.85 <0.20 Violent/disturbedbehaviorsorsocialproblems2 97.692119.272027.405016.72 <0.20 Chronicphysicalillnesses2,5 3832.484844.045068.4913645.48 <0.20 Severityofchronicphysical illnesses2,5 09379.497266.063041.119565.22 <0.20 11512.821816.512736.996020.07 2+ 97.691917.431621.924414.72 Co-occurringMHD-SRD1,2,5,7,8 3529.914339.453547.9511337.79 <0.20 Percentageofhighpriorityin EDtriage2 0–33%1916.242018.35912.334816.05 ≥0.20 34%–66%2420.512926.612230.147525.08 67%–100%7463.256055.054257.5317658.86

Sociodemographicandclinicalcharacteristicsofpatientsusingtheemergencydepartment(N = 299).

WesternJournal of EmergencyMedicineVolume25,No.2:March2024 148 PatientCharacteristicsAssociatedwithEDUseforMHD Fleuryetal.

Serviceuse(measuredintheprevious12months,orotherasspecified)

Group

LowED users(1–3 visits/year)

HighED users(4–7 visits/year)

Veryhigh EDusers (8+ visits/

1Seenote 1belowTable 1 2Seenote 2belowTable 1 3Systèmed’informationpermettantlagestiondel’informationcliniqueetadministrative dansledomainedelasantéetdesservicessociaux (I-CLSC,communityhealthcarecenterdatabase). 4Psychiatricoutpatientservicesused database. 5BasedontheCCHS,barrierstocareexplainingunmetneedswerea)Ipreferredtomanagebymyself;b)Ihaven’tgottenaround toityet(eg,toobusy);c)Ididn’thaveenoughconfidenceinthehealthcaresystemorsocialservices;d)Iwasafraidaboutwhatotherswould thinkofme;e)Ipreferredtoaskmyfamilyorfriendsforhelp;f)Iamdissatisfiedwiththequalityofservices;g)Idon’tknowhoworwheretoget thiskindofhelp;h)Myjobinterferedwithpossibletreatment(eg,hoursofwork);i)Thehelpisnotreadilyavailable;j)Icouldnotaffordtopay; myinsurancedidn’tcoverthecost;andk)Servicesarenotofferedinmylanguage. 6Seenote 5belowTable 1 ED,emergencydepartment.

usersthanmen.Patientslivinginrentalhousinghad2.09 timesmoreprobabilityofbeingveryhighEDusersthan thoselivinginprivatehousing.Patientsexhibitingviolent/ disturbedbehaviorsorsocialproblems,orchronicphysical illnesses,respectively,showed2.87and1.02timesincreasein probabilityofhighEDuse,anda5.55and4.95timesgreater probabilityofveryhighEDuse.Patientswithpersonality disordershad1.06timesgreaterprobabilityofhighEDuse, andthosewithsuicidalbehaviors,a1.29increased

probabilityofveryhighEDuse.Patientswith3+ barriers relatedtounmetneedshad1.64and2.27timesgreater probabilityofbeinghighorveryhighEDusers, respectively.Patientswith5+ primarycareservicesandhigh recurrentEDusehad2.5and1.53timesgreaterprobability ofbeingveryhighEDusers.Patientshospitalized 1–2timeshadareducedprobabilityof54%forhigh and79%forveryhighEDuse,comparedwiththose nothospitalized.

Table2. Serviceuseofpatientsusingtheemergencydepartment(N=299).

Bivariate analysis 11739.1310936.457324.41299100 n%n%n%n% P-value Size(N)meanSDmeanSDmeanSDmeanSD Verygoodtoexcellentknowledgeofmentalhealth oraddictionservices1 5950.436357.803953.4216153.85 ≥0.2 Havingafamilydoctororotherregularcareclinician1–3 10287.189688.076690.4126488.29 <0.20 Frequencyofprimarycare serviceuse1 02521.372220.1856.855217.39 <0.20 1–42924.793229.361419.187525.08 5+ 6353.855550.465473.9717257.53 Frequencyofserviceuseof community-basedorganizations1,3 06858.125146.792939.7314849.50 <0.20 1–42420.513330.281621.927324.41 5+ 2521.372522.942838.367826.09 Frequencyofspecializedoutpatient careuse1,4 01916.242018.351216.445117.06 <0.20 1–42823.931816.51912.335518.39 5+ 7059.837165.145271.2319364.55 Overallsatisfactionwithoutpatientservicesused(mean/SD)1 4.180.703.980.773.830.814.020.76 <0.20 Numberofbarriersrelatedto unmetneeds1,5 08169.236660.554156.1618862.88 <0.20 1–22420.512422.021723.296521.74 3+ 1210.261917.431520.554615.38 Frequencyofhospitalizations1,6 05446.154743.123041.113143.81 <0.20 1–25042.743733.941824.6610535.12 3+ 1311.112522.942534.256321.07 FrequencyofpreviousEDuse (measuredwithinthe2yearspriorto the12-monthperiodinwhich interviewswereconducted)1,2 0–34538.463733.941419.189632.11 <0.20 4–7(highEDusers)4437.613128.441115.078628.76 8+ (veryhighEDusers)2823.934137.614865.7511739.13

year)Total

Volume25,No.2:March2024WesternJournal of EmergencyMedicine 149 Fleuryetal. PatientCharacteristicsAssociatedwithEDUseforMHD

HighEDusers (4–7visits/year)

VeryhighEDusers (8+ visits/year)

RRR* P-value95%CI*RRR* P-value95%CI* Sociodemographiccharacteristics(measuredintheprevious12months)

Womenvsmen2.300.0071.254.231.480.3070.703.16

Typeofhousing1

Rentalvsprivate1.430.3260.702.943.090.0361.088.85

Supervisedvsprivate0.810.6310.341.942.180.2000.667.18

Clinicalcharacteristics(measuredintheprevious12months)

Personalitydisorders2.040.0391.044.012.260.0550.985.18

Suicidalbehaviors(suicideideationorattempt)1.810.0630.973.382.290.0461.015.16

Violent/disturbedbehaviorsorsocialproblems3.870.0051.529.856.550.0012.2619.00

Chronicphysicalillnesses2.020.0431.024.005.950.0002.5014.13

Serviceuse(measuredintheprevious12months,orotherasspecified)

Frequencyofprimarycareserviceuse

1

FrequencyofpreviousEDuse(measuredwithinthe2yearspriortothe12-monthperiod inwhichinterviewswereconducted)

ED,emergencydepartment;*RRR,relativeriskratio; CI,confidenceinterval. 1Seenote 4belowTable 1 2Seenote 5belowTable 2

DISCUSSION

Inthisstudyweaimedtoidentifysociodemographicand clinicalcharacteristics,aswellasserviceuse,amongpatients withMHD,comparinglow(1–3visits/year)tohigh(4–7 visits)andveryhighEDuse(8+ visits)formentalhealth reasons.Mostpatientshadhigh(37%)orveryhigh(24%)ED use,whichmaybeexplainedbythesubstantialsocialand healthissuestheyfaced.Theirlevelsofsocialandmaterial deprivationwerehigh,aswastheirperceivedstigma.Nearly halfhadseriousMHD,personalitydisordersorchronic physicalillnesses,whilemostexperiencedSRDandsuicidal behaviors.About40%reportedunmetneedsorpoorto fairknowledgeofservices,whichmayexplaintheirhigh overallEDuse.Asfoundinotherstudies,13,28 mosthighED userswerealsohighusersofoutpatientcareandwere frequentlyhospitalized.

Findingspartlyconfirmedthehypothesesthatveryhigh EDusers,followedbyhighEDusers,weremorelikelythan

lowEDuserstohavecomplexhealthandsocialissues,unmet needs,andtomakemorefrequentuseofoutpatientcare.The result showingthatdisturbed/violentbehaviorsorsocial problemswerethepatientcharacteristicsmoststrongly associatedwithbothveryhighandhighEDuse underlined thespecialneedsofthesepatients,whoforsomewerelikely involuntaryEDusers.Policearefrequentlycalledintodeal withpeoplepresentingviolentorerraticbehaviorsandto transportthemtoED.39

Interventionplans40 integratingbehavioraltreatment41 andhelpincrisisresolution42,43 maybebetterdeployedfor thesehighandveryhighEDusers.Studieshaveshownthat fewoverallinterventionsarebeingdeployedintheEDfor highusers.44,45 Previousstudieshavealsoshownthat patientswithchronicphysicalillnessesmademoreED visits.21,26 Thosewithco-occurringissueshadpoorerhealth overall,higherriskofmedicationinteractions46 andmore distress,47 explainingtheirfrequentEDuse.Improving

Table3. Estimationsofmultivariablemultinomiallogisticregressionmodelonemergencydepartment(ED)visits(referencegroup: lowEDusers,1–3visits/year).

–4vs.00.970.9410.412.311.260.7370.334.75 5+ vs.00.830.6410.381.803.510.0361.0911.35 Numberofbarriersrelatedtounmetneeds2 1–2vs.01.050.8920.512.151.130.7880.462.76 3+ vs.02.640.0321.096.423.270.0281.149.44 Frequencyofhospitalizations 1–2vs.00.460.0370.220.960.210.0020.080.56 3+ vs.01.470.4100.593.691.150.7970.393.45

4–7(highEDusers)vs.0–30.700.3080.351.400.560.7880.462.76 8+ (veryhighEDusers)vs.0–30.930.8550.441.972.530.0281.149.44

WesternJournal of EmergencyMedicineVolume25,No.2:March2024 150 PatientCharacteristicsAssociatedwithEDUseforMHD Fleuryetal.

collaborativecare48 betweenpsychiatristsandprimarycare servicesforbettertreatmentofpatientswithco-occurring issuesmayalsoreducetheirEDuse.

Higherperceivedbarriersforunmetneedswerealso stronglyassociatedwithmoreEDuse.Barriersmaybe structural(eg,lackofaccesstoservices)ormotivational (eg,duetodistrustordissatisfactionwithservices).49 AUS studyonbarrierstocareamongfrequentEDusersfoundthat mostofthemperceivedtheEDastheonlyplacewheretheir healthproblemswouldbetreated.50 Theseresultshighlight theimportanceofacknowledgingbarrierstooutpatientcare anddevelopingmorepersonalizedpatientcarebasedon recovery-orientatedserviceswithpatient-centred interventions,51,52 oralternative “rapid” specialized responsesforpatientswithMHDincrisis.53,54 Evenifvery highEDusersreceivedprimarycaremorefrequently,it doesn’tmeanthoseserviceswereadequateorsufficientto reduceorpreventunmetneeds.

Our findingthatbeinghospitalized1-2times,butnot3+ times/year,wasprotectiveagainsthighorveryhighEDuse comparedwithnotbeinghospitalized,wasanoriginalresult. Mosthospitalizedpatientsarereferredbyemergency physicians,55 whichmightsuggestthattheserepeated hospitalizedpatientshaveveryserioushealthconditionsand thattheirinpatientcareepisodesmaybeunavoidable.Lack ofabilitytorefer(eg,timeofday)orpossibilitytorefer (eg,longwaitinglists)tooutpatientcare,lackofmental healthsupportintheED(eg,briefinterventionteams)56,57 or ofcomfortintreatingpatientswithmorecomplexMHD profilesinoutpatientcaremightalsoexplainfrequentpatient hospitalizations.Hospitalizationmaysometimesbethemost appropriatesolutionformaximizingpatientrecovery.58 For patientswith1–2hospitalizations/year,closefollow-up care,59,60 whichisincreasinglyrecommendedfollowing discharge,mayhavecontributedtoreducingtheirEDuse. Diversifiedstrategiessuchasassertivecommunitytreatment programs, 61 hometreatmentteams,62 short-staycrisis units,63 andcrisisinterventionteams64 arealsoincreasingly beingpromotedtohelpreduceacutecareuse.Althoughsuch interventionsremaininsufficientlydeployedinQuebec,the province’snewMentalHealthActionPlan(2022–2026) promisestoincreasetheiruse.25

ComparedtolowEDusers,veryhighEDusershada higherprobabilityofhavingsuicidalbehaviors,whilehigh usersshowedhigherprobabilityofhavingpersonality disorders.Previousstudieshavefoundassociationsforboth theseissueswithgreaterEDuse.13,16,28 Consideringthat healthcaresystemstendtorespondpoorlytocrisis situations,55 especiallythosethatoccuroutsideregular businesshours,thefactthatthesestudyparticipantswere veryhighEDuserswasnotsurprising.Greateravailabilityof sustainedpsychosocialprogramsinprimarycareandmore specializedcrisisandsuicidalpreventionservices65 mayhelp preventEDvisitsforsuicidalbehaviors.66 Dialectical

behaviortherapymayalsobepromotedmoreextensivelyto reducesymptomsofpersonalitydisorders,borderline personalitydisorderinparticular,asreportedinasystematic review.67 Ingeneral,theEDshouldnotreplaceoutpatient careforvulnerablepatients,astheircapacitytotreatsuch patientswasidentifiedaslimited.68,69

WomenhadagreaterprobabilityofhighEDusethan men,andpatientslivinginrentalhousingshowedagreater probabilityofveryhighEDusethanthoseinprivate housing.Womenreportedlyusemorehealthservicesthan men, 70 whichforhighEDusecontradictedpreviousstudies thatfoundmoremenwerehighEDusers.15,26 Becausehigh andveryhighEDusersweredifferentiatedinourstudy,it mayaccountforthisdivergentresult,withnodifference foundbetweenwomenandmeninveryhighEDusers.The compositionofourstudysamplecouldalsoexplainthis finding,asamajorityofparticipantsrecruitedrandomlyby EDstaffwerewomen.Concerningpatientsresidinginrental housing,theymayexperiencegreaterdeprivation,including inadequatehousingsupport,comparedwiththoselivingin privateorsupervisedhousing,whichmayaccountfortheir veryhighEDuse.Sometypeofsupportivehousingwithcase management71 mayhelpthesepatientsavoidfrequentED use.Difficultytoaccessoutpatientcarebecauseoflong waitinglistsortransportationissuesmightalsoexplainvery highEDuseamongthesepatients.

Using5+ primarycareservices/yearandrecurrenthigh EDusewereonlyassociatedwithveryhighEDusers comparedtolowEDusers,butnothighEDusers.Asfor highEDusers,studieshaveidentifiedthemashighservice usersingeneral,72 andasbeing “recurrent” EDusersover severalconsecutiveyears.6,28 Ourstudyaddedtothis literaturebyspecifyingthatonlypatientswhomadeatleast fiveprimarycareappointmentsinthepreviousyearandeight EDvisitsintheprevioustwoyearshadagreaterprobability ofbeingveryhighEDusers(8+ EDvisits/year).Thegreater useofprimarycareservicesamongveryhighEDusersmay beexplainedbytheirhigherratesofchronicphysicalillnesses andthegreaterseverityoftheseconditions,comparedwith ratesforlowandhighEDusers.Perhapsprimarycarewas notadequateorcontinuousenoughtopreventEDuse 22,73 or topreventorreduceunmetneeds.Generalpractitionershave beenshowntolacktrainingorsufficientteamcapacityto adequatelyfollowuponvulnerablepatientswithMHD.74,75 Collaborativecaremaybemorepromotedbetweenprimary andpsychiatriccareandteamworktoreduceEDuseand bettertreatthesepatients.76,77

LIMITATIONS

Thisstudyhadcertainlimitationsthatshouldbenoted. First,thereisnoconsensualdefinitionforlow,high,andvery highEDuse.Differentdefinitionsthanthosechosenhere couldhaveledtodifferent findings.Second,thestudyresults weredifficulttocomparewiththeliteratureasmoststudies

Volume25,No.2:March2024WesternJournal of EmergencyMedicine 151 Fleuryetal. PatientCharacteristicsAssociatedwithEDUseforMHD

havecomparedhighEDusewithotherEDuse.Third, structuredinterviewsmaybebiasedduetothepatients’ abilitytorecall,andthehealthrecordsthatwereused reflectedserviceuseonlywithintheparticipatingnetworks. Finally,thediversityofhealthcaresystemsmaylimitthe generalizationofthestudy findings,especiallyincountries thatdon’thavepublichealthcarecoveragefor deprivedpopulations.

CONCLUSION

Thisstudywasinnovativeinthewayitcomparedlow, high,andveryhighEDusersamongpatientswithMHDin Canada,andbyusingbothpatientstructuredinterviewsand healthrecords.The findingsconfirmedthathigherEDuse wasassociatedwithcomplexpatienthealthissuesandhigher perceivedbarrierstounmetneeds.Patientswithveryhigh overallEDusehadthemostsevereconditions,including greaterhousingvulnerabilityandisolation,andmore suicidalbehaviors.Theyalsousedmoreprimarycare services,possiblybecauseoftheirseverechronicphysical healthconditions.

RecurrentEDuseovertheyearsalsodistinguishedvery highEDusersfromlowusers.Bycontrast,theriskofhigh andveryhighEDusewasreducedinpatientswith1–2 hospitalizations/year,whichunderlinesthepotentialbenefits andpertinenceofhospitalizationforsomepatients.Overall, barrierstocareshouldbereducedandbetteraccessand continuityofoutpatientcareprovidedforthemost vulnerablepatients,integratingcrisisresolutionand supportedhousingservices.Thismayreducethenumberof patientswithMHDintheED,decreasingwaittimesand improvingcareintheED.

2.MinassianA,VilkeGM,WilsonMP.Frequentemergencydepartment visitsaremoreprevalentinpsychiatric,alcoholabuse,anddual diagnosisconditionsthaninchronicviralillnessessuchashepatitisand humanimmunodeficiencyvirus. JEmergMed.2013;45(4):520–5.

3.GiannouchosTV,KumHC,FosterMJ,etal.Characteristicsand predictorsofadultfrequentemergencydepartmentusersintheUnited States:asystematicliteraturereview. JEvalClinPract 2019;25(3):420–33.

4.KriegC,HudonC,ChouinardMC,etal.Individualpredictorsoffrequent emergencydepartmentuse:ascopingreview. BMCHealthServRes 2016;16(1):594.

5.LaCalleEandRabinE.Frequentusersofemergencydepartments:the myths,thedata,andthepolicyimplications. Review.AnnEmergMed 2010;56(1):42–8.

6.BillingsJandRavenMC.Dispellinganurbanlegend:frequent emergencydepartmentusershavesubstantialburdenofdisease. HealthAff(Millwood).2013;32(12):2099–108.

7.MoeJ,KirklandS,OspinaMB,etal.Mortality,admissionratesand outpatientuseamongfrequentusersofemergencydepartments: asystematicreview. EmergMedJ.2016;33(3):230–6.

8.VandykAD,HarrisonMB,VanDenKerkhofEG,etal.Frequent emergencydepartmentusebyindividualsseekingmentalhealthcare: asystematicsearchandreview. ArchPsychiatrNurs.2013;27(4):171–8.

9.FleuryMJ,FortinM,RochetteL,etal.Assessingqualityindicators relatedtomentalhealthemergencyroomutilization. BMCEmergMed 2019;19(1):8.

10.OndlerC,HegdeGG,CarlsonJN.Resourceutilizationandhealthcare chargesassociatedwiththemostfrequentEDusers. AmJEmergMed 2014;32(10):1215–9.

11.ChangG,WeissAP,OravEJ,etal.Predictorsoffrequentemergency departmentuseamongpatientswithpsychiatricillness. GenHosp Psychiatry.2014;36(6):716–20.

AddressforCorrespondence:Marie-JoséeFleury,PhD,Douglas MentalHealthUniversityInstituteResearchCentre,6875,LaSalle Blvd.,Verdun,Canada.Email: flemar@douglas.mcgill.ca

ConflictsofInterest:Bythe WestJEMarticlesubmissionagreement, allauthorsarerequiredtodiscloseallaffiliations,fundingsources and financialormanagementrelationshipsthatcouldbeperceived aspotentialsourcesofbias.ThisstudywasfundedbytheCanadian InstitutesofHealthResearch(CIHR,grantnumber:8400997).

Copyright:©2024Fleuryetal.Thisisanopenaccessarticle distributedinaccordancewiththetermsoftheCreativeCommons Attribution(CCBY4.0)License.See: http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/

REFERENCES

1.LiuSW,NagurneyJT,ChangY,etal.FrequentEDusers:aremostvisits formentalhealth,alcohol,anddrug-relatedcomplaints? AmJEmerg Med.2013;31(10):1512–5.

12.BuhumaidR,RileyJ,SattarianM,etal.Characteristicsoffrequentusers oftheemergencydepartmentwithpsychiatricconditions. JHealthCare PoorUnderserved.2015;26(3):941–50.

13.Richard-LepourielH,WeberK,BaertschiM,etal.Predictorsofrecurrent useofpsychiatricemergencyservices. PsychiatrServ 2015;66(5):521–6.

14.SirotichF,DurbinA,DurbinJ.Examiningtheneedprofilesofpatients withmultipleemergencydepartmentvisitsformentalhealthreasons: across-sectionalstudy. SocPsychiatryPsychiatrEpidemiol 2016;51(5):777–86.

15.FleuryMJ,RochetteL,GrenierG,etal.Factorsassociatedwith emergencydepartmentuseformentalhealthreasonsamonglow, moderateandhighusers. GenHospPsychiatry.2019;60:111–9.

16.SlankamenacK,HeidelbergerR,KellerDI.Predictionofrecurrent emergencydepartmentvisitsinpatientswithmentaldisorders. FrontPsychiatry.2020;11:48.

17.VuF,DaeppenJB,HugliO,etal.Screeningofmentalhealthand substanceusersinfrequentusersofageneralSwissemergency department. BMCEmergMed.2015;15:27.

WesternJournal of EmergencyMedicineVolume25,No.2:March2024 152 PatientCharacteristicsAssociatedwithEDUseforMHD Fleuryetal.

18.GaulinM,SimardM,CandasB,etal.Combinedimpactsof multimorbidityandmentaldisordersonfrequentemergencydepartment visits:aretrospectivecohortstudyinQuebec,Canada. CMAJ 2019;191(26):E724–32.

19.MitchellMS,LeonCLK,ByrneTH,etal.Costofhealthcareutilization amonghomelessfrequentemergencydepartmentusers. PsycholServ 2017;14(2):193–202.

20.KorczakV,ShanthoshJ,JanS,etal.Costsandeffectsof interventionstargetingfrequentpresenterstotheemergency department:asystematicandnarrativereview. BMCEmergMed 2019;19(1):83.

21.DoupeMB,PalatnickW,DayS,etal.Frequentusersofemergency departments:developingstandarddefinitionsanddefiningprominent riskfactors. AnnEmergMed.2012;60(1):24–32.

22.GentilL,GrenierG,VasiliadisHM,etal.Predictorsofrecurrenthigh emergencydepartmentuseamongpatientswithmentaldisorders.

IntJEnvironResPublicHealth.2021;18(9):4559.

23.MinistèredelaSantéetdesServicesSociaux(MSSS).Lesystèmede santéetdeServicesSociauxauQuébec,enbref.Quebec:Government ofQuebec.2017.Availableat: https://publications.msss.gouv.qc.ca

AccessedJanuary27,2022.

24.MinistèredelaSantéetdesServicessociaux(MSSS).Projetdeloino 10(2015,chapitre1).Loimodifiantl’organisationetlagouvernancedu réseaudelasantéetdesservicessociauxnotammentparl’abolitiondes agencesrégionales.Quebec:GovernmentofQuebec.2015.

Availableat: https://www2.publicationsduquebec.gouv.qc.ca

AccessedJanuary21,2022.

25.Ministèredelasantéetdesservicessociaux(MSSS).LePland’action interministérielensantémentale2022-2026-S’unirpourunmieux-être collectifPublicationsduministèredelaSantéetdesServicessociaux. Quebec:GovernmentofQuebec.2022.Availableat: https:// publications.msss.gouv.qc.ca/msss/document-003301 AccessedJanuary27,2022.

26.BrennanJJ,ChanTC,HsiaRY,etal.Emergencydepartmentutilization amongfrequentuserswithpsychiatricvisits. AcadEmergMed 2014;21(9):1015–22.

27.MoeJ,BaileyAL,OlandR,etal.Defining,quantifying,and characterizingadultfrequentusersofasuburbanCanadianemergency department. CJEM.2013;15(4):214–26.

28.ArmoonB,CaoZ,GrenierG,etal.Profilesofhighemergency departmentuserswithmentaldisorders. AmJEmergMed 2022;54:131–41.

29.BohnMJ,BaborTF,KranzlerHR.Thealcoholusedisorders identificationtest(AUDIT):validationofascreeninginstrumentforusein medicalsettings. JStudAlcohol.1995;56(4):423–32.

30.SkinnerHA.Thedrugabusescreeningtest. AddictBehav 1982;7(4):363–71.

31.HuynhC,KiselyS,RochetteL,etal.Usingadministrativehealthdatato estimateprevalenceandmortalityratesofalcoholandothersubstancerelateddisordersforsurveillancepurposes. DrugAlcoholRev 2021;40(4):662–72.

32.SimardM,SiroisC,CandasB.Validationofthecombinedcomorbidity indexofCharlsonandElixhausertopredict30-daymortalityacross ICD-9andICD-10. MedCare.2018;56(5):441–7.

33.CanadianAssociationofEmergencyPhysicians.Canadiantriageacuity scale.2012.Availableat: https://ctas-phctas.ca AccessedDecember18,2021.

34.HarrisMG,HobbsMJ,BurgessPM,etal.Frequencyandqualityof mentalhealthtreatmentforaffectiveandanxietydisordersamong Australianadults. MedJAust.2015;202(4):185–9.

35.DziuraJD,PostLA,ZhaoQ,etal.Strategiesfordealingwithmissing datainclinicaltrials:fromdesigntoanalysis. YaleJBiolMed 2013;86(3):343–58.

36.MickeyJandGeenlandS.Astudyoftheimpactofcounfounderselectioncriteriaoneffectestimation. AmJEpidemiol 1989;129(1):125–37.

37.AkaikeH.Informationtheoryandanextensionofthemaximum likelihoodprinciple.In:PetrovBNandCsakiF(Eds.), Proceedingsofthe 2ndInternationalSymposiumonInformationTheory (267–81). Hungary,Budapest:AkademiaiKiado,1973.

38.HairJ,BlackWC,BabinBJ,etal.(2001). MultivariateDataAnalysis (7thed.).NewJersey,UpperSaddleRiver:PearsonEducation.

39.ShortTBR.Thenatureofpoliceinvolvementinmentalhealthtransfers. PolicePractRes.2014;15(4):336–48.

40.AbelloA,Jr.,BriegerB,DearK,etal.Careplanprogramreduces thenumberofvisitsforchallengingpsychiatricpatientsintheED. AmJEmergMed.2012;30(7):1061–7.

41.FrazierSNandVelaJ.Dialecticalbehaviortherapyforthetreatmentof angerandaggressivebehavior:areview. AggressViolentBehav 2014;19(2):156–63.

42.WheelerC,Lloyd-EvansB,ChurchardA,etal.Implementationofthe crisisresolutionteammodelinadultmentalhealthsettings:asystematic review. BMCPsychiatry.2015;15:74.

43.VakkalankaJP,NeuhausRA,HarlandKK,etal.Mobilecrisisoutreach andemergencydepartmentutilization:apropensityscore-matched analysis. WestJEmergMed.2021;22(5):1086–94.

44.GabetM,ArmoonB,MengX,etal.Effectivenessofemergency departmentbasedinterventionsforfrequentuserswithmentalhealth issues:asystematicreview. AmJEmergMed.2023;74:1–8.

45.GabetMandFleuryM-J.Innovationsorganisationnellesauxurgences pouraméliorerlaqualitédessoinsdispensésauxpatientssouffrantde troublesmentaux:perspectivesinternationales. JGestÉconSanté 2022;40(2-3):100–15.

46.KangHJ,KimSY,BaeKY,etal.Comorbidityofdepressionwith physicaldisorders:researchandclinicalimplications. ChonnamMedJ 2015;51(1):8–18.

47.QinP,HawtonK,MortensenPB,etal.Combinedeffectsofphysical illnessandcomorbidpsychiatricdisorderonriskofsuicideinanational populationstudy. BrJPsychiatry.2014;204(6):430–5.

48.IvbijaroGO,EnumY,KhanAA,etal.Collaborativecare:modelsfor treatmentofpatientswithcomplexmedical-psychiatricconditions. CurrPsychiatryRep.2014;16(11):506.

Volume25,No.2:March2024WesternJournal of EmergencyMedicine 153 Fleuryetal. PatientCharacteristicsAssociatedwithEDUseforMHD

49.MojtabaiR,OlfsonM,SampsonNA,etal.Barrierstomentalhealth treatment:resultsfromtheNationalComorbiditySurveyReplication. PsycholMed.2011;41(8):1751–61.

50.BirminghamLE,CochranT,FreyJA,etal.Emergencydepartmentuse andbarrierstowellness:asurveyofemergencydepartmentfrequent users. BMCEmergMed.2017;17(1):16.

51.ChesterP,EhrlichC,WarburtonL,etal.Whatistheworkofrecovery orientedpractice?Asystematicliteraturereview. IntJMentHealthNurs 2016;25(4):270–85.

52.CareyTA.Beyondpatient-centeredcare:enhancingthepatient experienceinmentalhealthservicesthroughpatient-perspectivecare. PatientExpJ.2016;3(2):46–9.

53.HubbelingDandBertramR.CrisisresolutionteamsintheUKand elsewhere. JMentHealth.2012;21(3):285–95.

54.BoucheryEE,BarnaM,BabalolaE,etal.Theeffectivenessofapeerstaffedcrisisrespiteprogramasanalternativetohospitalization. PsychiatrServ.2018;69(10):1069–74.

55.JohnsonS,Dalton-LockeC,BakerJ,etal.Acutepsychiatriccare: approachestoincreasingtherangeofservicesandimprovingaccess andqualityofcare. WorldPsychiatry.2022;21(2):220–36.

56.GabetM,GrenierG,CaoZ,etal.Implementationofthreeinnovative interventionsinapsychiatricemergencydepartmentaimedatimproving serviceuse:amixed-methodstudy. BMCHealthServRes 2020;20(1):854.

57.TurnerSBandStantonMP.Psychiatriccasemanagementinthe emergencydepartment. ProfCaseManag.2015;20(5):217–27; quiz228-9.

58.JunWHandYunSH.Mentalhealthrecoveryamonghospitalized patientswithmentaldisorder:associationswithangerexpressionmode andmeaninginlife. ArchPsychiatrNurs.2020;34(3):134–40.

59.GentilL,GrenierG,FleuryMJ.Factorsrelatedto30-dayreadmission followinghospitalizationforanymedicalreasonamongpatientswith mentaldisorders[Facteursliesalarehospitalisationa30jourssuivant unehospitalisationpouruneraisonmedicalechezdespatientssouffrant detroublesmentaux]. CanJPsychiatry.2021;66(1):43–55.

60.KurdyakP,VigodSN,NewmanA,etal.Impactofphysicianfollow-up careonpsychiatricreadmissionratesinapopulation-basedsampleof patientswithschizophrenia. PsychiatrServ.2018;69(1):61–8.

61.AddingtonD,AndersonE,KellyM,etal.Canadianpracticeguidelines forcomprehensivecommunitytreatmentforschizophreniaand schizophreniaspectrumdisorders. CanJPsychiatry 2017;62(9):662–72.

62.BoisvertA,BouffardA-P,PaquetK.Letraitementintensifbrefà domicile. SantéMentale.2016;204:68–72.

63.AndersonK,GoldsmithLP,LomaniJ,etal.Short-staycrisisunitsfor mentalhealthpatientsoncrisiscarepathways:systematicreviewand meta-analysis. BJPsychOpen.2022;8(4):e144.

64.MurphySM,IrvingCB,AdamsCE,etal.Crisisinterventionfor peoplewithseverementalillnesses. CochraneDatabaseSystRev 2015;2015(12):CD001087.

65.MisharaBL,CoteLP,DargisL.Systematicreviewofresearchand interventionswithfrequentcallerstosuicidepreventionhelplinesand crisiscenters. Crisis.2023;44(2):154–67.

66.GentilL,GrenierG,FleuryMJ.Determinantsofsuicidalideationand suicideattemptamongformerandcurrentlyhomelessindividuals. SocPsychiatryPsychiatrEpidemiol.2020;56(5):747–57.

67.BloomJM,WoodwardEN,SusmarasT,etal.Useofdialecticalbehavior therapyininpatienttreatmentofborderlinepersonalitydisorder: asystematicreview. PsychiatrServ.2012;63(9):881–8.

68.DeLeoK,MaconickL,McCabeR,etal.Experiencesofcrisiscare amongserviceuserswithcomplexemotionalneedsoradiagnosisof 'personalitydisorder',andotherstakeholders:systematicreviewand meta-synthesisofthequalitativeliterature. BJPsychOpen 2022;8(2):e53.

69.StanleyB,BrownGK,BrennerLA,etal.Comparisonofthesafety planninginterventionwithfollow-upvsusualcareofsuicidalpatients treatedintheemergencydepartment. JAMAPsychiatry 2018;75(9):894–900.

70.PinkhasovRM,ShteynshlyugerA,HakimianP,etal.Aremen shortchangedonhealth?Perspectiveonlifeexpectancy,morbidity,and mortalityinmenandwomenintheUnitedStates. IntJClinPract 2010;64(4):465–74.

71.McPhersonP,KrotofilJ,KillaspyH.Mentalhealthsupported accommodationservices:asystematicreviewofmentalhealthand psychosocialoutcomes. BMCPsychiatry.2018;18(1):128.

72.PinesJM,AsplinBR,KajiAH,etal.Frequentusersofemergency departmentservices:gapsinknowledgeandaproposedresearch agenda. AcadEmergMed. 2011;18(6):e64–9.

73.BarkerLC,SunderjiN,KurdyakP,etal.Urgentoutpatientcarefollowing mentalhealthedvisits:apopulation-basedstudy. PsychiatrServ. 2020;71(6):616–9.

74.FleuryMJ,BamvitaJM,FarandL,etal.GPgroupprofilesand involvementinmentalhealthcare.Researchsupport,non-U.S.Gov’t. JEvalClinPract.2012;18(2):396–403.

75.LoebDF,BaylissEA,BinswangerIA,etal.Primarycarephysician perceptionsoncaringforcomplexpatientswithmedicalandmental illness. JGenInternMed.2012;27(8):945–52.

76.AupontO,DoerflerL,ConnorDF,etal.Acollaborativecaremodelto improveaccesstopediatricmentalhealthservices. AdmPolicyMent Health.2013;40(4):264–73.

77.RaneyLE.Integratingprimarycareandbehavioralhealth:therole ofthepsychiatristinthecollaborativecaremodel. AmJPsychiatry 2015;172(8):721–8.

WesternJournal of EmergencyMedicineVolume25,No.2:March2024 154 PatientCharacteristicsAssociatedwithEDUseforMHD Fleuryetal.

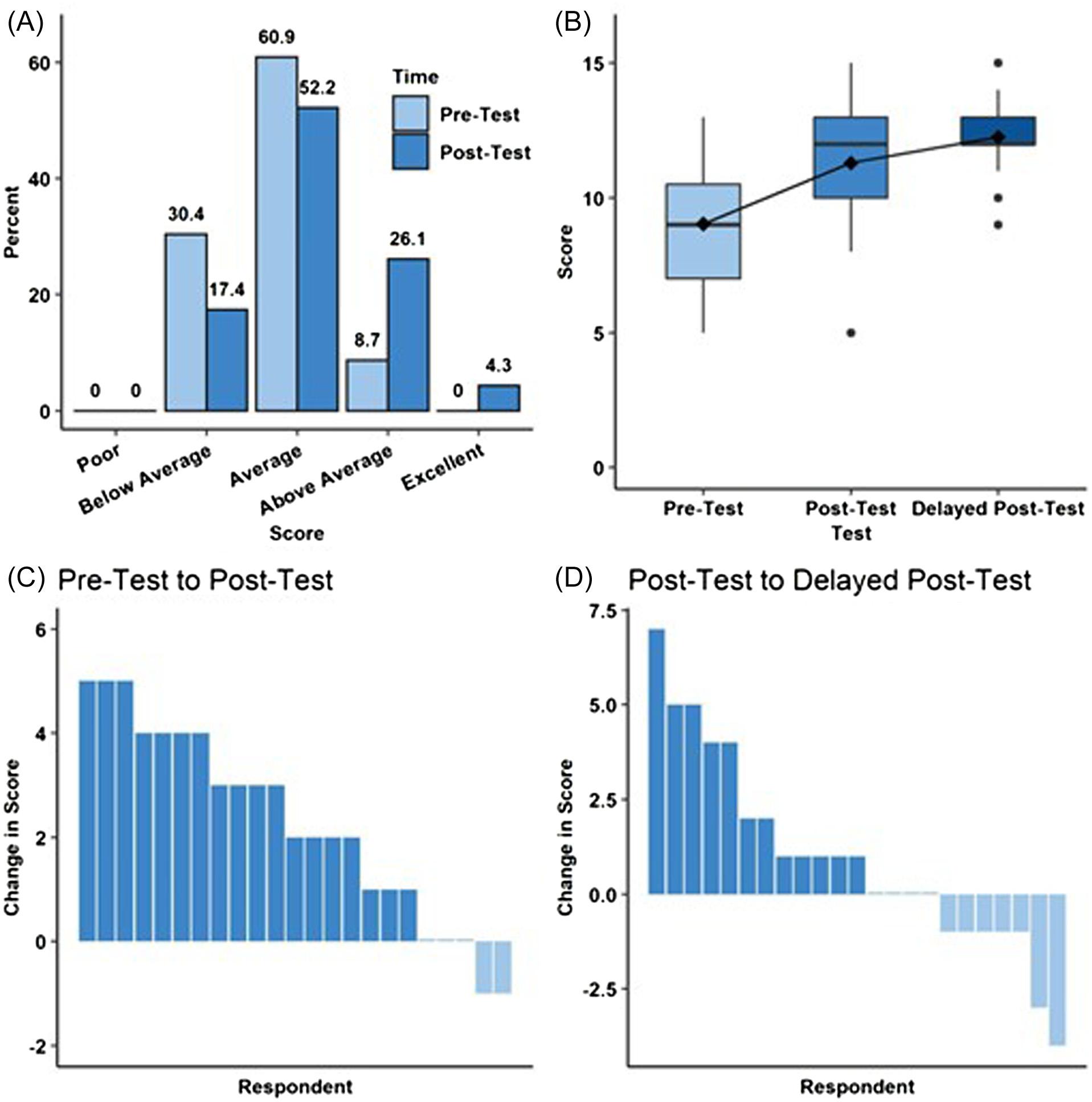

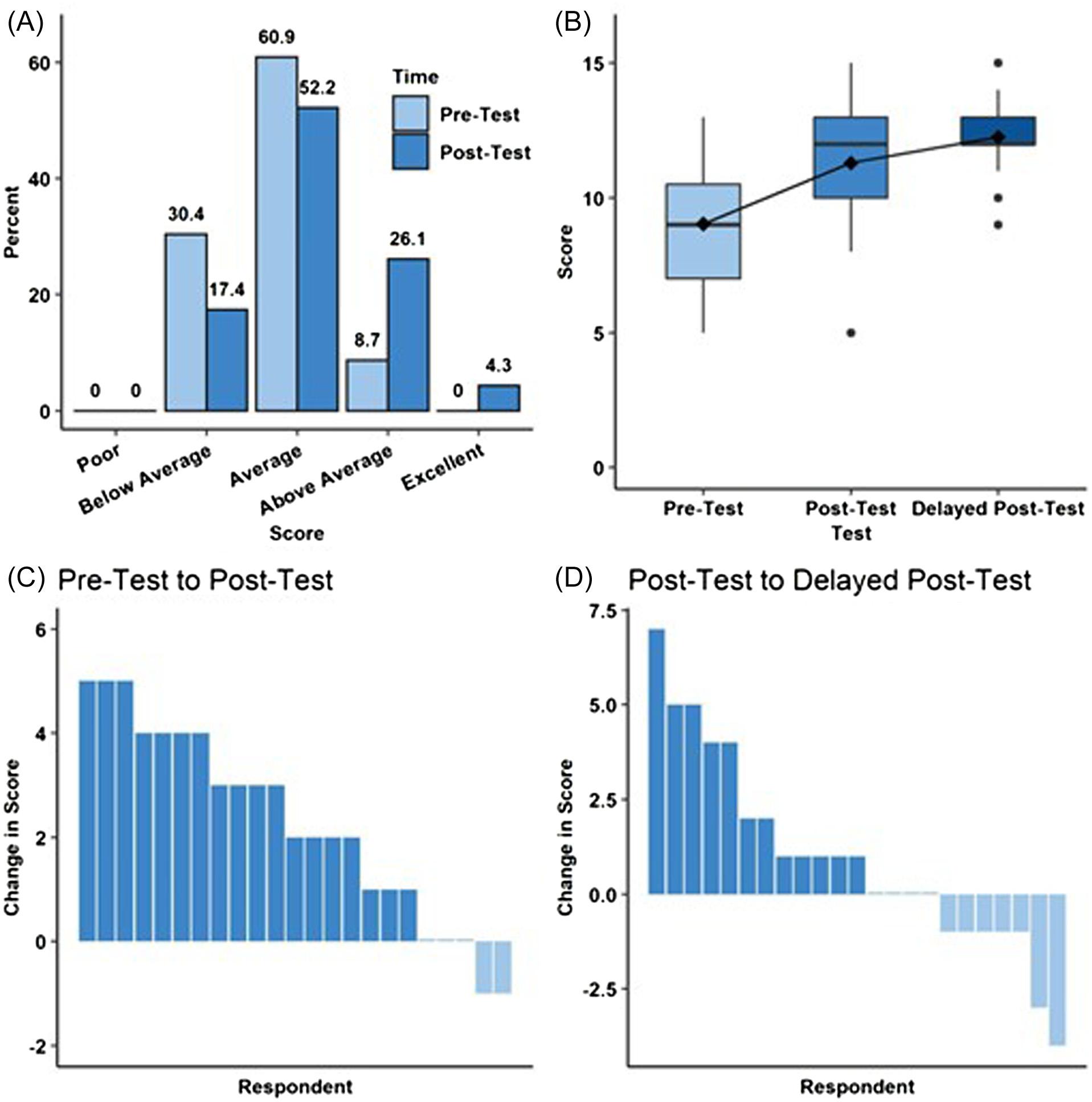

BridgingtheGap:EvaluationofanElectrocardiogramCurriculum forAdvancedPracticeClinicians

StevenLindsey,MD*

TimP.Moran,PhD*

MeredithA.Stauch,MSN,APRN,FNP-BC,ENP-C†

AlexisL.Lynch,MSN,APRN,ENP-C,FNP-BC,ANP-BC*