Western Journal of Emergency Medicine: Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health

Indexed in MEDLINE

Medical Education

1499 The Effect of Dictation on Emergency Medicine Resident Time to Note Completion

LR Willoughby, DJ Hekman, BH Schnapp

1504 Program Director Perspectives on the Impact of the Proposed 48-Month Emergency Medicine Residency Requirement: A National Survey

R Austin, C Patel, K Delfino, S Kim

1510 A Qualitative Study of Senior Residents’ Strategies to Prepare for Unsupervised Practice

M Griffith, A Garrett, BK Watsjold, J Jauregui, M Davis, JS Ilgen

1519 Language Differences by Race in the Narrative Section of the Emergency Medicine Standardized Letter of Evaluation

S Fletcher, K Carter, J Ahn, P Kukulski

1526 A Taste of Our Own Medicine: Fostering Empathy in Medical Learners Through Patient Simulation

RP Peña, W Weber

1530 The State of Simulation in Emergency Medicine Residency Programs in the United States

BD Miller, C Khoury, J Raper, LA Walter, A Bloom

1536 Unveiling Humility in Emergency Medicine Chief Residents: A Thematic Exploration of Standard Letters of Evaluation

A Bierowski, R Ghei, C Morrone, XC Zhang, D Papanagnou

1544 A 30-year History of the Emergency Medicine Standardized Letter of Evaluation JS Hegarty, CB Hegarty, JN Love, A Pelletier-Bui, S Bord, MC Bond, SM Keim, EF Shappell

Clinical Practice

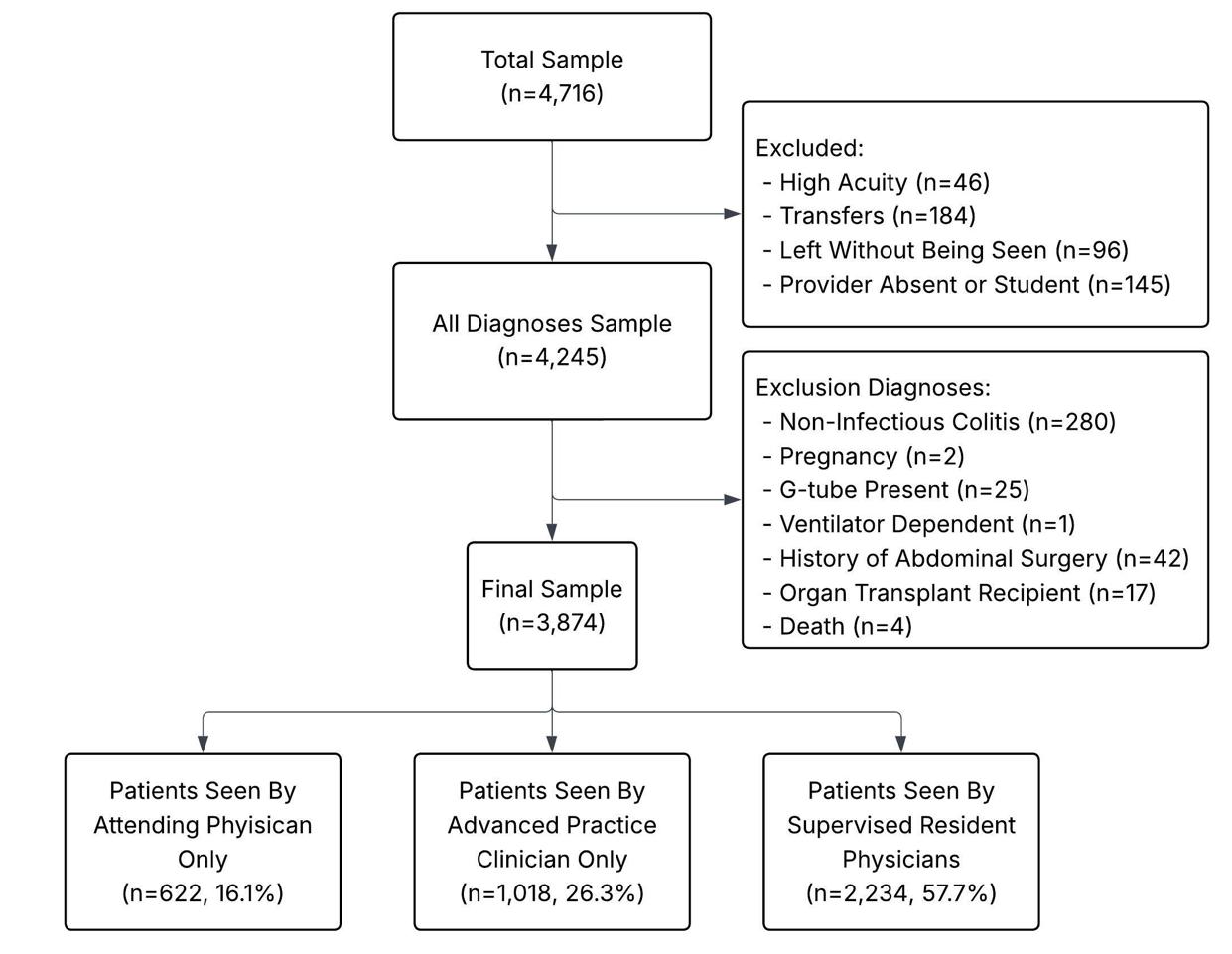

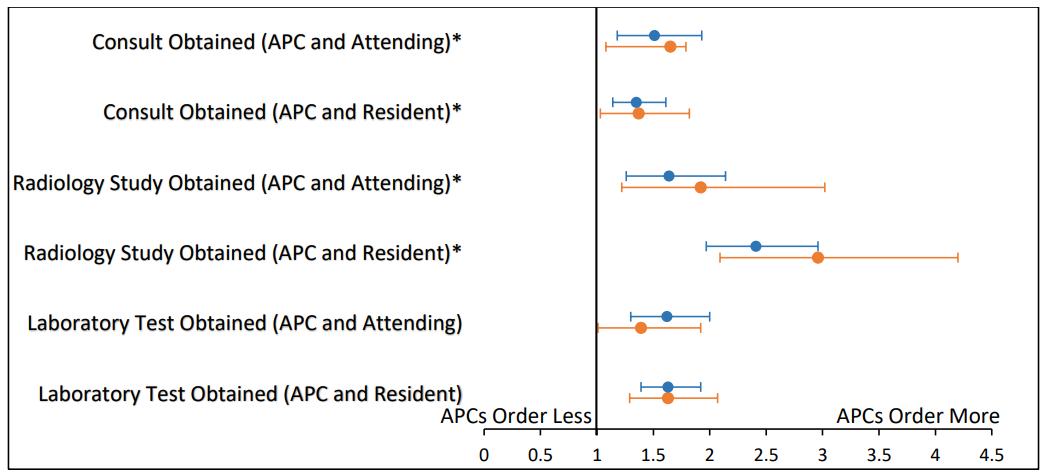

1549 Resource Utilization and Throughput in Pediatric Abdominal Pain among Attendings, Residents, and Advanced Practice Clinicians

AG Nuwan Perera, R Tisherman, R Pitetti, K Conti, SA Ohl, J Dunnick

Penn State Health Emergency Medicine

About Us: Penn State Health is a multi-hospital health system serving patients and communities across central Pennsylvania. We are the only medical facility in Pennsylvania to be accredited as a Level I pediatric trauma center and Level I adult trauma center. The system includes Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, Penn State Health Children’s Hospital and Penn State Cancer Institute based in Hershey, Pa.; Penn State Health Hampden Medical Center in Enola, Pa.; Penn State Health Holy Spirit Medical Center in Camp Hill, Pa.; Penn State Health Lancaster Medical Center in Lancaster, Pa.; Penn State Health St. Joseph Medical Center in Reading, Pa.; Pennsylvania Psychiatric Institute, a specialty provider of inpatient and outpatient behavioral health services, in Harrisburg, Pa.; and 2,450+ physicians and direct care providers at 225 outpatient practices. Additionally, the system jointly operates various healthcare providers, including Penn State Health Rehabilitation Hospital, Hershey Outpatient Surgery Center and Hershey Endoscopy Center.

We foster a collaborative environment rich with diversity, share a passion for patient care, and have a space for those who share our spark of innovative research interests. Our health system is expanding and we have opportunities in both academic hospital as well community hospital settings.

Benefit highlights include:

• Competitive salary with sign-on bonus

• Comprehensive benefits and retirement package

• Relocation assistance & CME allowance

• Attractive neighborhoods in scenic central Pennsylvania

FOR MORE INFORMATION PLEASE CONTACT:

Heather Peffley, PHR CPRP

Penn State Health Lead Physician Recruiter hpeffley@pennstatehealth.psu.edu

Western Journal of Emergency Medicine:

Emergency Care with Population Health Indexed in MEDLINE, PubMed, and Clarivate Web of Science, Science Citation Index Expanded

Andrew W. Phillips, MD, Associate Editor DHR Health-Edinburg, Texas

Edward Michelson, MD, Associate Editor Texas Tech University- El Paso, Texas

Dan Mayer, MD, Associate Editor Retired from Albany Medical College- Niskayuna, New York

Wendy Macias-Konstantopoulos, MD, MPH, Associate Editor Massachusetts General Hospital- Boston, Massachusetts

Gayle Galletta, MD, Associate Editor University of Massachusetts Medical SchoolWorcester, Massachusetts

Yanina Purim-Shem-Tov, MD, MS, Associate Editor Rush University Medical Center-Chicago, Illinois

Section Editors

Behavioral Emergencies

Bradford Brobin, MD, MBA Chicago Medical School

Marc L. Martel, MD

Hennepin County Medical Center

Ryan Ley, MD

Hennepin County Medical Center

Cardiac Care

Sam S. Torbati, MD Cedars-Sinai Medical Center

Emily Sbiroli, MD Palomar Medical Center

Climate Change

Gary Gaddis, MBBS University of Maryland

Clinical Practice

Cortlyn W. Brown, MD Carolinas Medical Center

Casey Clements, MD, PhD Mayo Clinic

Patrick Meloy, MD Emory University

Nicholas Pettit, DO, PhD Indiana University

David Thompson, MD University of California, San Francisco

Kenneth S. Whitlow, DO Kaweah Delta Medical Center

Critical Care

Christopher “Kit” Tainter, MD University of California, San Diego

Gabriel Wardi, MD University of California, San Diego

Joseph Shiber, MD University of Florida-College of Medicine

Matt Prekker MD, MPH Hennepin County Medical Center

David Page, MD University of Alabama

Erik Melnychuk, MD Geisinger Health

Quincy Tran, MD, PhD University of Maryland

Disaster Medicine

John Broach, MD, MPH, MBA, FACEP

University of Massachusetts Medical School UMass Memorial Medical Center

Christopher Kang, MD Madigan Army Medical Center

Mark I. Langdorf, MD, MHPE, Editor-in-Chief University of California, Irvine School of MedicineIrvine, California

Shahram Lotfipour, MD, MPH, Managing Editor University of California, Irvine School of MedicineIrvine, California

Gary Gaddis MBBS, Associate Editor University of Maryland- Baltimore, Maryland

Rick A. McPheeters, DO, Associate Editor Kern Medical- Bakersfield, California

R. Gentry Wilkerson, MD, Associate Editor University of Maryland

Education

Danya Khoujah, MBBS

University of Maryland School of Medicine

Jeffrey Druck, MD University of Colorado

John Burkhardt, MD, MA University of Michigan Medical School

Michael Epter, DO Maricopa Medical Center

ED Administration, Quality, Safety

David C. Lee, MD Northshore University Hospital

Gary Johnson, MD Upstate Medical University

Brian J. Yun, MD, MBA, MPH Harvard Medical School

Laura Walker, MD Mayo Clinic

León D. Sánchez, MD, MPH Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center

William Fernandez, MD, MPH University of Texas Health-San Antonio

Robert Derlet, MD

Founding Editor, California Journal of

Emergency Medicine

University of California, Davis

Emergency Medical Services

Daniel Joseph, MD Yale University

Joshua B. Gaither, MD University of Arizona, Tuscon

Julian Mapp

University of Texas, San Antonio

Shira A. Schlesinger, MD, MPH Harbor-UCLA Medical Center

Geriatrics

Cameron Gettel, MD Yale School of Medicine

Stephen Meldon, MD Cleveland Clinic

Luna Ragsdale, MD, MPH Duke University

Health Equity

Emily C. Manchanda, MD, MPH Boston University School of Medicine

Faith Quenzer

Temecula Valley Hospital San Ysidro Health Center

Mandy J. Hill, DrPH, MPH UT Health McGovern Medical School

Payal Modi, MD MScPH

Quincy Tran, MD, Deputy Editor University of Maryland School of Medicine- Baltimore, Maryland

Brian Yun, MD, MPH, MBA, Associate Editor Boston Medical Center-Boston, Massachusetts

Michael Pulia, MD, PhD, Associate Editor University of Wisconsins Hospitals and Clinics- Madison, Wisconsin

Patrick Joseph Maher, MD, MS, Associate Editor Ichan School of Medicine at Mount Sinai- New York, New York

Donna Mendez, MD, EdD, Associate Editor University of Texas-Houston/McGovern Medical School- Houston Texas

Danya Khoujah, MBBS, Associate Editor University of Maryland School of Medicine- Baltimore, Maryland

University of Massachusetts Medical

Infectious Disease

Elissa Schechter-Perkins, MD, MPH Boston University School of Medicine

Ioannis Koutroulis, MD, MBA, PhD

George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences

Kevin Lunney, MD, MHS, PhD University of Maryland School of Medicine

Stephen Liang, MD, MPHS Washington University School of Medicine

Victor Cisneros, MD, MPH Eisenhower Medical Center

Injury Prevention

Mark Faul, PhD, MA Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Wirachin Hoonpongsimanont, MD, MSBATS

Eisenhower Medical Center

International Medicine

Heather A.. Brown, MD, MPH Prisma Health Richland

Taylor Burkholder, MD, MPH Keck School of Medicine of USC

Christopher Greene, MD, MPH University of Alabama

Chris Mills, MD, MPH

Santa Clara Valley Medical Center

Shada Rouhani, MD

Brigham and Women’s Hospital

Legal Medicine

Melanie S. Heniff, MD, JD Indiana University School of Medicine

Statistics and Methodology

Shu B. Chan MD, MS Resurrection Medical Center

Stormy M. Morales Monks, PhD, MPH Texas Tech Health Science University

Soheil Saadat, MD, MPH, PhD University of California, Irvine

James A. Meltzer, MD, MS Albert Einstein College of Medicine

Musculoskeletal

Juan F. Acosta DO, MS Pacific Northwest University

Rick Lucarelli, MD Medical City Dallas Hospital

William D. Whetstone, MD University of California, San Francisco

Neurosciences

Antonio Siniscalchi, MD Annunziata Hospital, Cosenza, Italy

Pediatric Emergency Medicine

Muhammad Waseem, MD Lincoln Medical & Mental Health Center

Cristina M. Zeretzke-Bien, MD University of Florida

Public Health

Jacob Manteuffel, MD Henry Ford Hospital

John Ashurst, DO Lehigh Valley Health Network

Tony Zitek, MD Kendall Regional Medical Center

Trevor Mills, MD, MPH Northern California VA Health Care

Erik S. Anderson, MD Alameda Health System-Highland Hospital

Technology in Emergency Medicine

Nikhil Goyal, MD

Henry Ford Hospital

Phillips Perera, MD Stanford University Medical Center

Trauma

Pierre Borczuk, MD

Massachusetts General Hospital/Havard

Medical School

Toxicology

Brandon Wills, DO, MS Virginia Commonwealth University

Jeffrey R. Suchard, MD University of California, Irvine

Ultrasound

J. Matthew Fields, MD Thomas Jefferson University

Shane Summers, MD Brooke Army Medical Center

Robert R. Ehrman Wayne State University

Ryan C. Gibbons, MD Temple Health

Official Journal of the California Chapter of the American College of Emergency Physicians, the American College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians, the California Chapter of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine, and Official International Journal of the World Academic Council of Emergency Medicine (WACEM)

Available in MEDLINE, PubMed, PubMed Central, CINAHL, SCOPUS, Google Scholar, eScholarship, Melvyl, DOAJ, EBSCO, EMBASE, Medscape, HINARI, and MDLinx Emergency Med. Members of OASPA.

Editorial and Publishing Office: WestJEM/Depatment of Emergency Medicine, UC Irvine Health, 3800 W. Chapman Ave. Suite 3200, Orange, CA 92868, USA Office: 1-714-456-6389; Email: Editor@westjem.org

No. 5: September 2025

Western Journal of Emergency Medicine:

Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health

Indexed in MEDLINE, PubMed, and Clarivate Web of Science, Science Citation Index Expanded

Editorial Board

Amin A. Kazzi, MD, MAAEM

The American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon

Anwar Al-Awadhi, MD

Mubarak Al-Kabeer Hospital, Jabriya, Kuwait

Arif A. Cevik, MD

United Arab Emirates University College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Al Ain, United Arab Emirates

Abhinandan A.Desai, MD University of Bombay Grant Medical College, Bombay, India

Bandr Mzahim, MD

King Fahad Medical City, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Brent King, MD, MMM University of Texas, Houston

Christopher E. San Miguel, MD Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center

Daniel J. Dire, MD University of Texas Health Sciences Center San Antonio

David F.M. Brown, MD Massachusetts General Hospital/ Harvard Medical School

Douglas Ander, MD Emory University

Edward Michelson, MD Texas Tech University

Edward Panacek, MD, MPH University of South Alabama

Francesco Della Corte, MD

Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria “Maggiore della Carità,” Novara, Italy

Hoon ChinStevenLim, MBBS, MRCSEd Changi General Hospital

Gayle Galleta, MD

Sørlandet Sykehus HF, Akershus Universitetssykehus, Lorenskog, Norway

Jacob (Kobi) Peleg, PhD, MPH Tel-Aviv University, Tel-Aviv, Israel

Jaqueline Le, MD Desert Regional Medical Center

Jeffrey Love, MD The George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences

Jonathan Olshaker, MD Boston University

Katsuhiro Kanemaru, MD University of Miyazaki Hospital, Miyazaki, Japan

Kenneth V. Iserson, MD, MBA University of Arizona, Tucson

Advisory Board

Kimberly Ang, MBA

UC Irvine Health School of Medicine

Elena Lopez-Gusman, JD

California ACEP

American College of Emergency Physicians

Amanda Mahan, Executive Director

American College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians

John B. Christensen, MD

California Chapter Division of AAEM

Randy Young, MD

California ACEP

American College of Emergency Physicians

Mark I. Langdorf, MD, MHPE UC Irvine Health School of Medicine

Jorge Fernandez, MD

California ACEP

American College of Emergency Physicians University of California, San Diego

Peter A. Bell, DO, MBA

American College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians Baptist Health Science University

Robert Suter, DO, MHA

American College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians UT Southwestern Medical Center

Shahram Lotfipour, MD, MPH UC Irvine Health School of Medicine

Brian Potts, MD, MBA California Chapter Division of AAEM Alta Bates Summit-Berkeley Campus

Khrongwong Musikatavorn, MD

King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand

Leslie Zun, MD, MBA Chicago Medical School

Linda S. Murphy, MLIS University of California, Irvine School of Medicine Librarian

Pablo Aguilera Fuenzalida, MD Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, Región Metropolitana, Chile

Peter A. Bell, DO, MBA Baptist Health Sciences University

Peter Sokolove, MD University of California, San Francisco

Rachel A. Lindor, MD, JD Mayo Clinic

Robert M. Rodriguez, MD University of California, San Francisco

Robert Suter, DO, MHA UT Southwestern Medical Center

Robert W. Derlet, MD University of California, Davis

Rosidah Ibrahim, MD Hospital Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia

Samuel J. Stratton, MD, MPH Orange County, CA, EMS Agency

Scott Rudkin, MD, MBA University of California, Irvine

Scott Zeller, MD University of California, Riverside

Terry Mulligan, DO, MPH, FIFEM ACEP Ambassador to the Netherlands Society of Emergency Physicians

Wirachin Hoonpongsimanont, MD, MSBATS

Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand

Editorial Staff

Ian Olliffe, BS Executive Editorial Director

Sheyda Aquino, BS WestJEM Editorial Director

Tran Nguyen, BS CPC-EM Editorial Director

Stephanie Burmeister, MLIS WestJEM Staff Liaison

Cassandra Saucedo, MS Executive Publishing Director

Isabelle Kawaguchi, BS WestJEM Publishing Director

Alyson Tsai CPC-EM Publishing Director

Isabella Choi, BS Associate Publishing Director

June Casey, BA Copy Editor

Official Journal of the California Chapter of the American College of Emergency Physicians, the American College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians, the California Chapter of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine, and Official International Journal of the World Academic Council of Emergency Medicine (WACEM)

Available in MEDLINE, PubMed, PubMed Central, Europe PubMed Central, PubMed Central Canada, CINAHL, SCOPUS, Google Scholar, eScholarship, Melvyl, DOAJ, EBSCO, EMBASE, Medscape, HINARI, and MDLinx Emergency Med. Members of OASPA. Editorial and Publishing Office: WestJEM/Depatment of Emergency Medicine, UC Irvine Health, 3800 W. Chapman Ave. Suite 3200, Orange, CA 92868, USA Email: Editor@westjem.org

Western

Journal of Emergency Medicine: Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health

Indexed in MEDLINE, PubMed, and Clarivate Web of Science, Science Citation Index Expanded

JOURNAL FOCUS

Emergency medicine is a specialty which closely reflects societal challenges and consequences of public policy decisions. The emergency department specifically deals with social injustice, health and economic disparities, violence, substance abuse, and disaster preparedness and response. This journal focuses on how emergency care affects the health of the community and population, and conversely, how these societal challenges affect the composition of the patient population who seek care in the emergency department. The development of better systems to provide emergency care, including technology solutions, is critical to enhancing population health.

Table of Contents

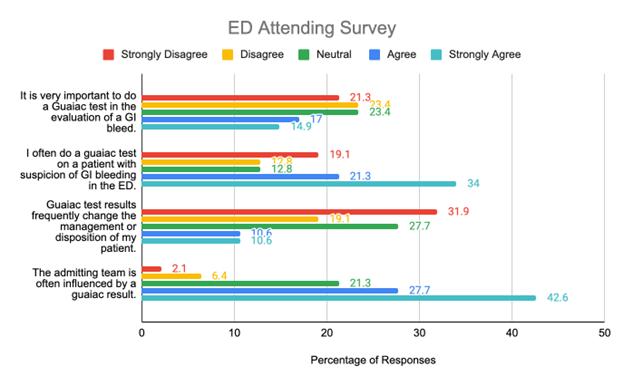

1559 Comparison of Emergency Physicians’ and Hospitalists’ Attitudes Toward Fecal Occult Blood Testing in Gastrointestinal Bleeding

D Ilic, J Bove

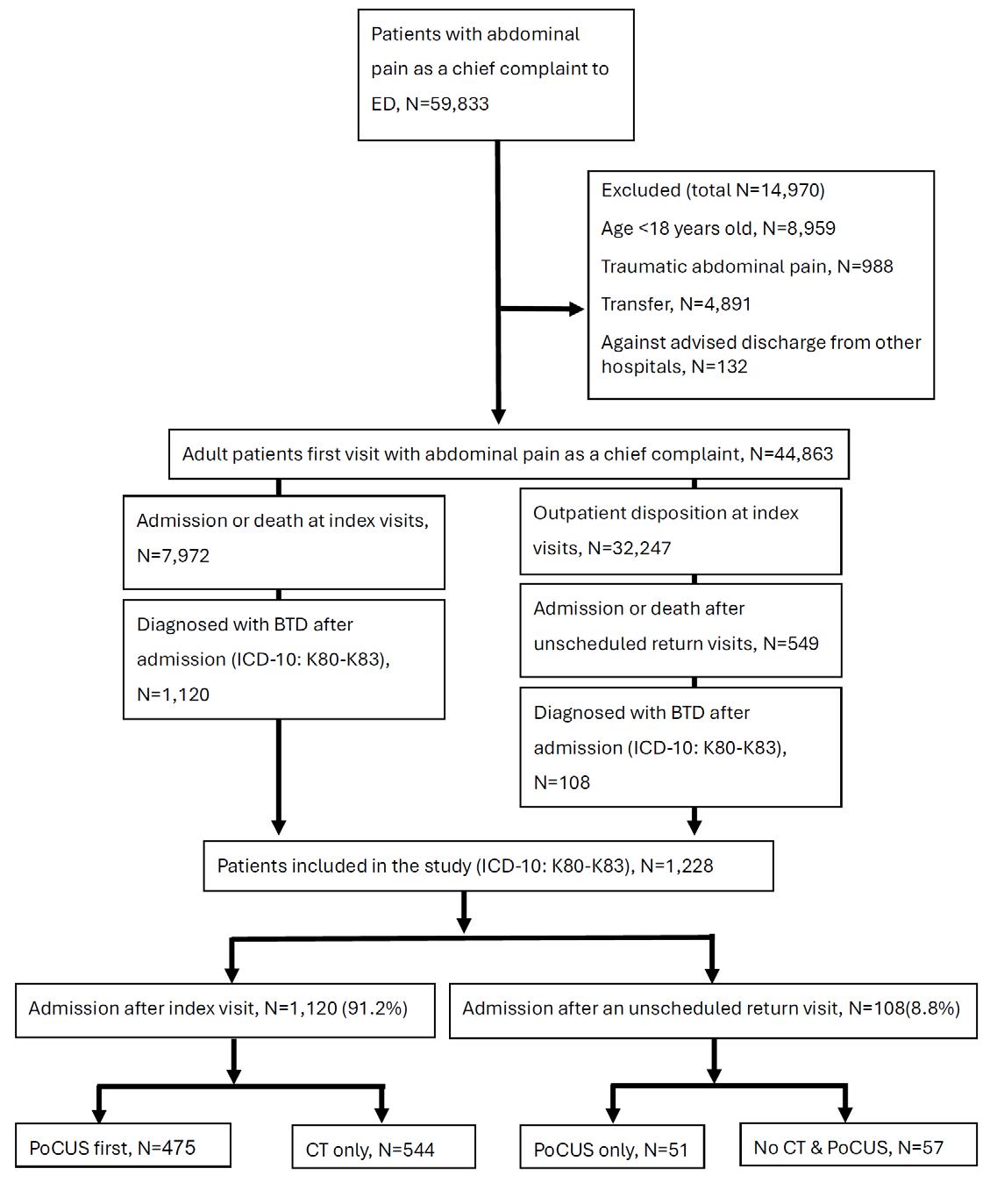

1564 Emergency Department Disposition and Point-of-Care Ultrasound in Biliary Disease: Propensity Weighted Cohort Study

Y Eda, PS Wu, FW Huang, SY Hung, CT Hsu, WK Chen, SH Wu

1575 Biological Sex Is Associated with Pre-Tibial Subcutaneous Tissue Depth for Intraosseous Catheter Insertion

AJ DuVall, T Sprys-Tellner, T Lemon, R Kelly, A Stefan, JH Paxton

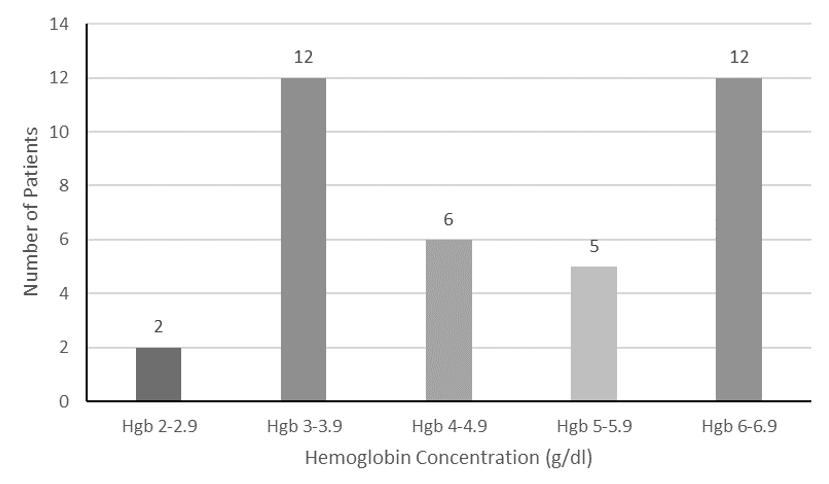

1581 Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Pediculosis-associated Severe Anemia in the Emergency Department

W Plowe, R Colling, S Mohan, R Gulati, R Biary, E Yanni, CA Koziatek

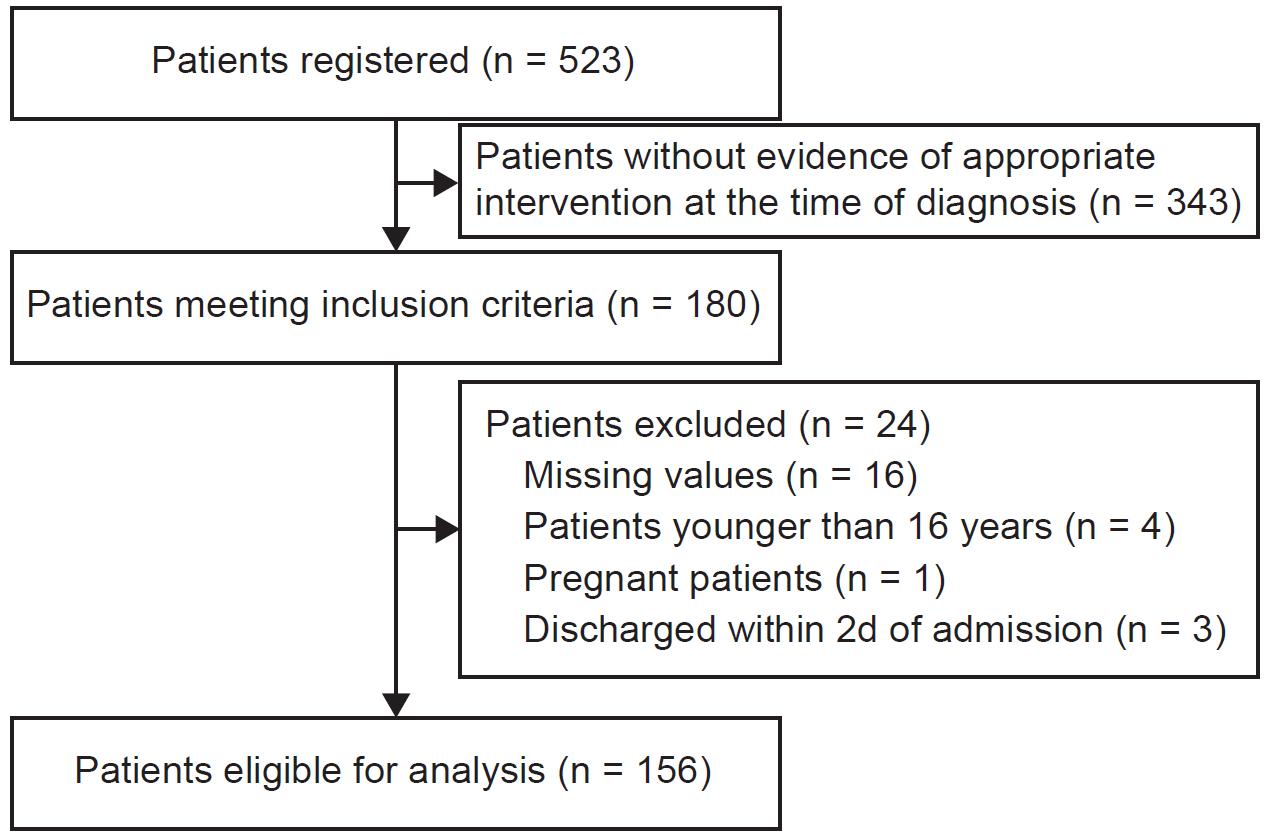

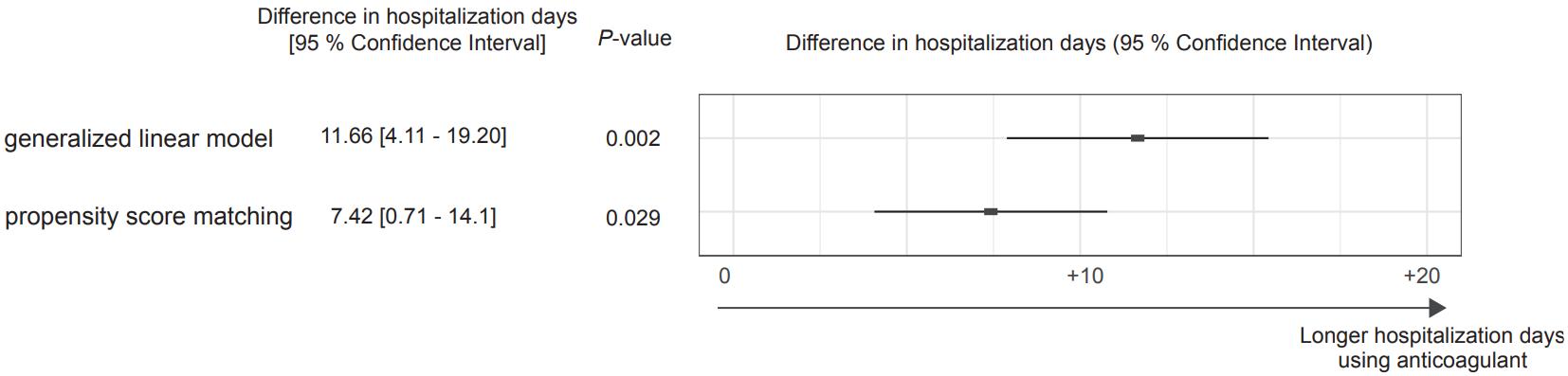

1590 Anticoagulation Treatment in Patients with Septic Thrombophlebitis of the Internal Jugular Vein

A Senda, K Fushimi, K Morishita

Behavioral Health

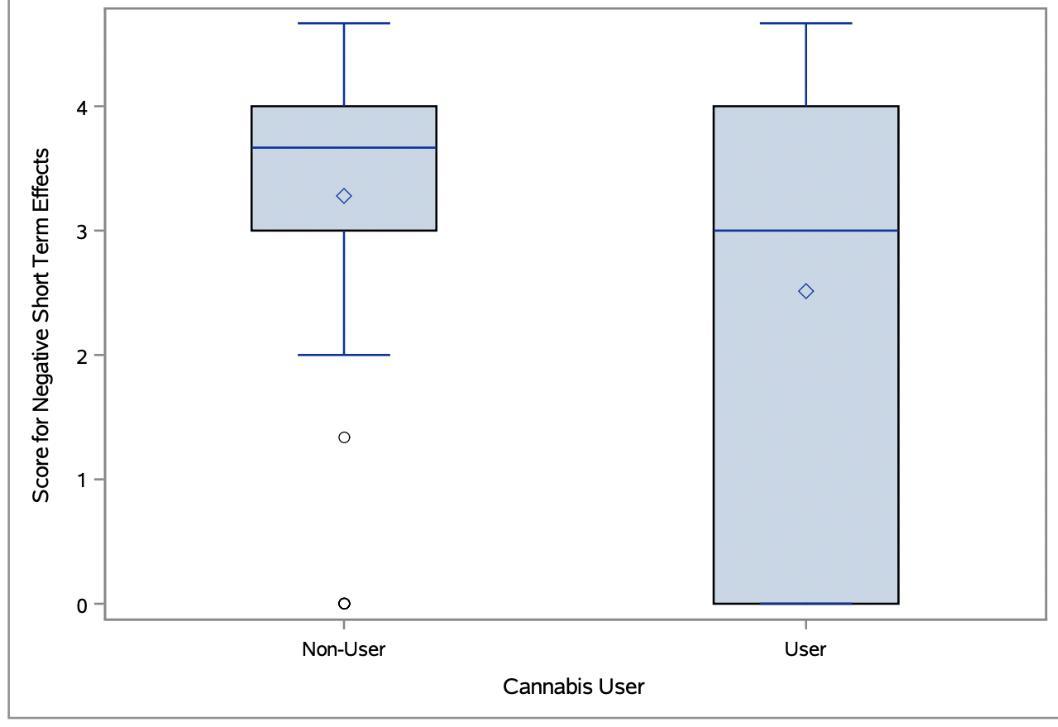

1598 Comparison of Perspectives on Cannabis Use Between Emergency Department Patients Who Are Users and Non-users

CA Marco, L Becker, M Egner, Q Erturk, A Sharma, T Vail, C Soderman, N Morrison, S Sandelich

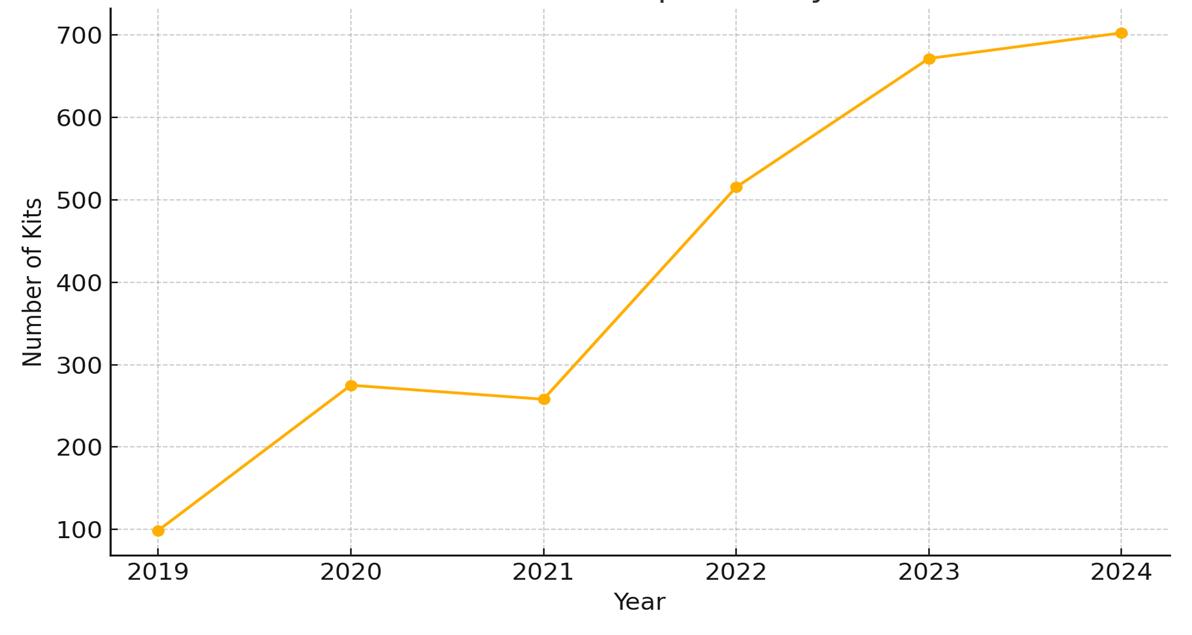

1605 Development of a Low-Barrier, Reimbursable Take-Home Naloxone Program at a Regional Health System

KS London, S Patel, D Lockstein, J Rashid, D Goodstein, R Pacitti, T Warrick-Stone, F Randolph, A Cherney, K Alexander, M Reed

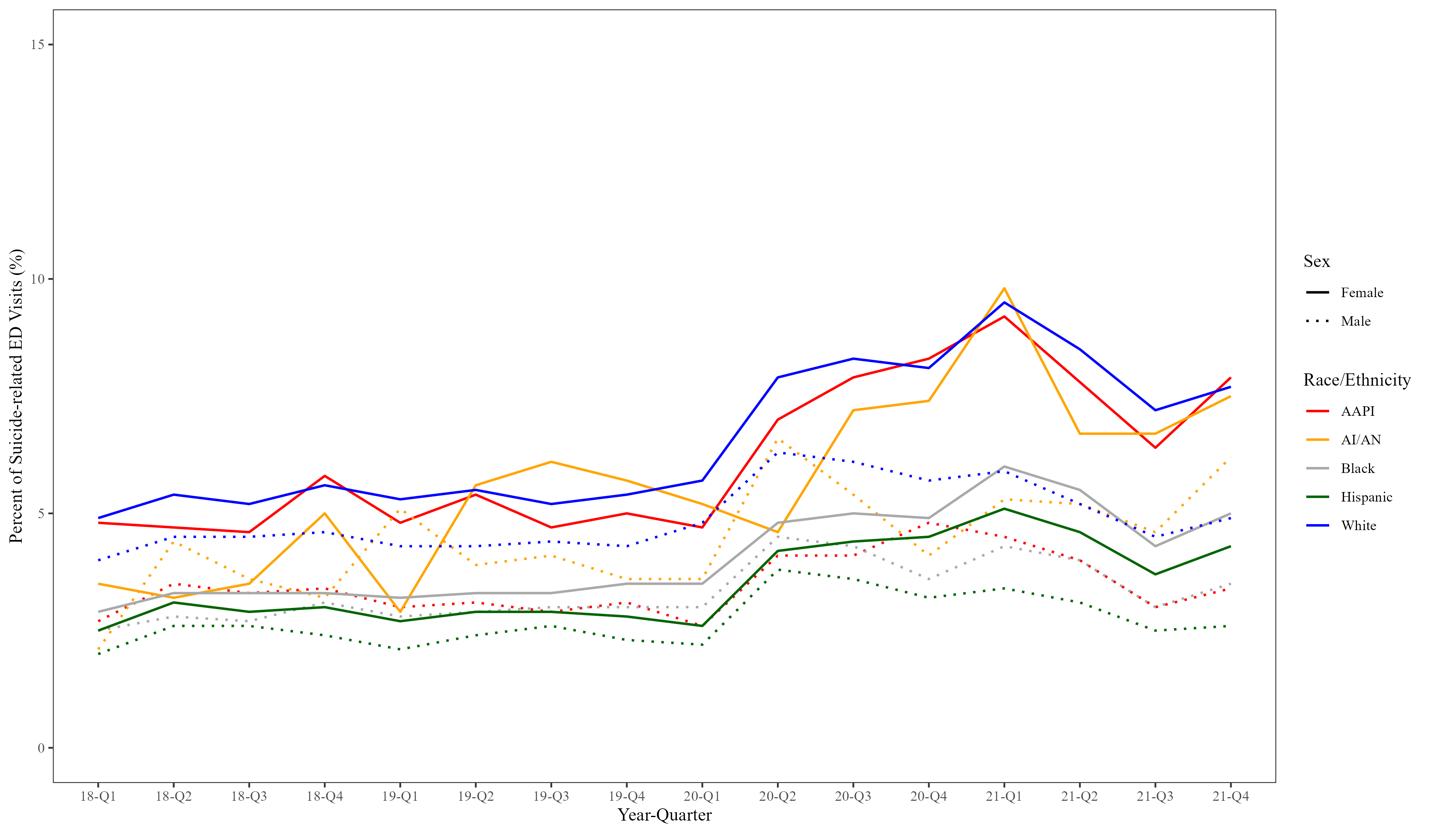

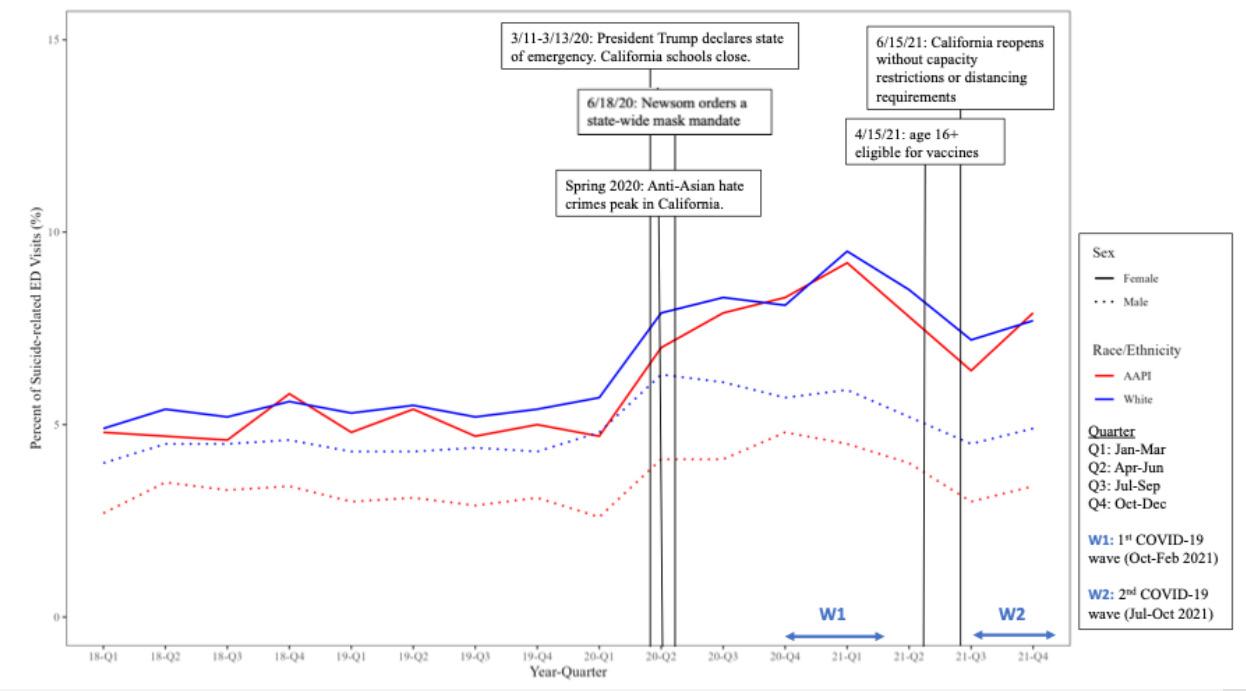

1611 Intersectional Analysis of Suicide-related Emergency Department Visits in Youth in California, 2018–2021

LM Prichett, A Na, H Fujii-Rios, EE Haroz

Emergency Department Operations

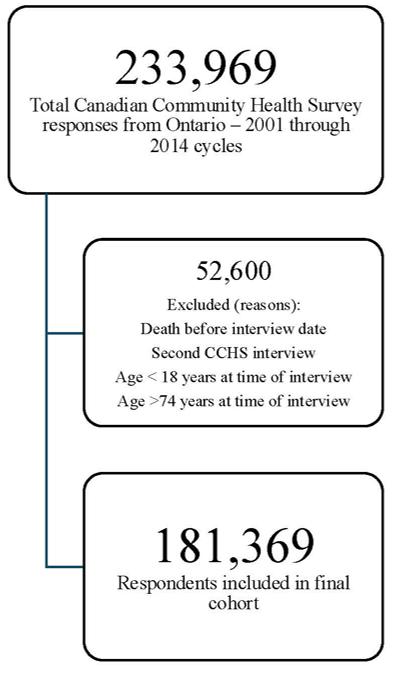

1622 Sociodemographic and Health Behaviour of Frequent, Avoidable Emergency Department Users in Ontario, Canada: A Population-based Descriptive Study

C Thompson, T Watson, MJ Schull, J Gronsbell, L CA Rosella

Policies for peer review, author instructions, conflicts of interest and human and animal subjects protections can be found online at www.westjem.com.

No. 5: September 2025

Western Journal of Emergency Medicine:

Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health

Indexed in MEDLINE, PubMed, and Clarivate Web of Science, Science Citation Index Expanded

Table of Contents continued

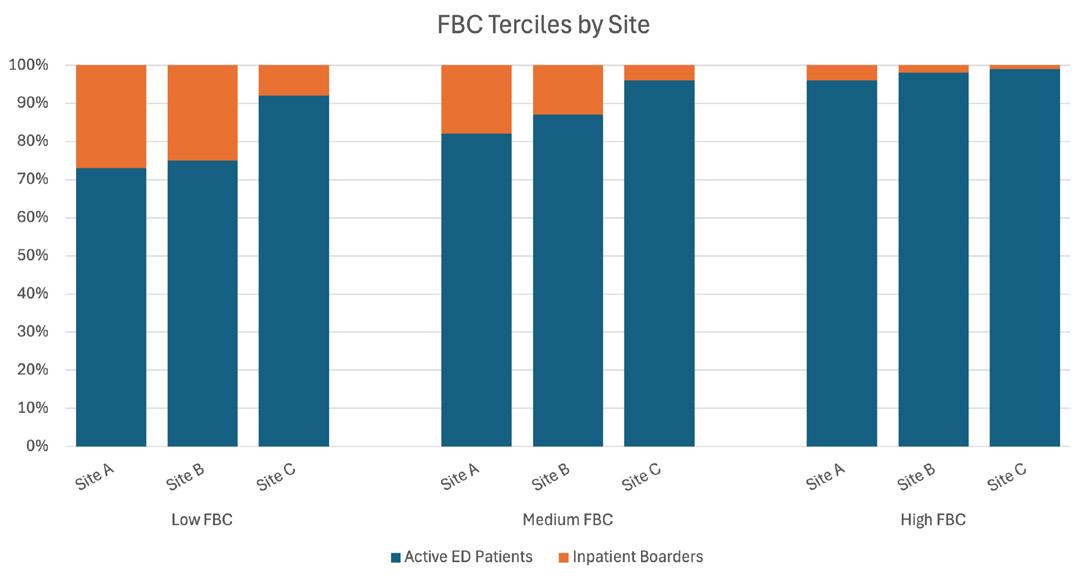

1640 Patterns in Duration of Emergency Department Boarding and Variation by Sociodemographic Factors

CK Prucnal, MA Meeker, M Copenhaver, PS Jansson, RE Cash, W Hillmann, S Knuesel, W MaciasKonstantopoulos, JD Sonis

1648 Reduced Functional Bed Capacity Due to Inpatient Boarding Is Associated with Increased Rates of Left Without Being Seen in the Emergency Department Y Berlyand, T Lin, TD Marquis, JS Anderson, DJ Shanin, AC Lawrence, FL Overly, DB Curley, J Baird, AM Napoli

Cardiology

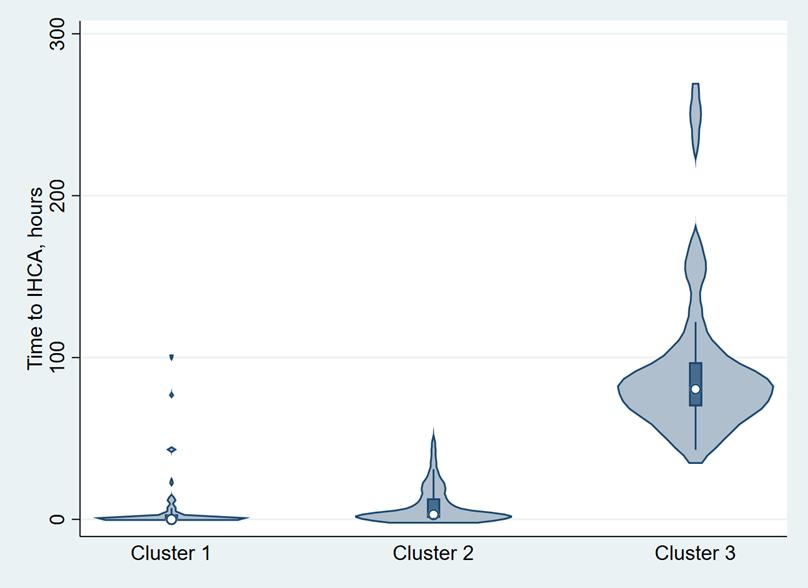

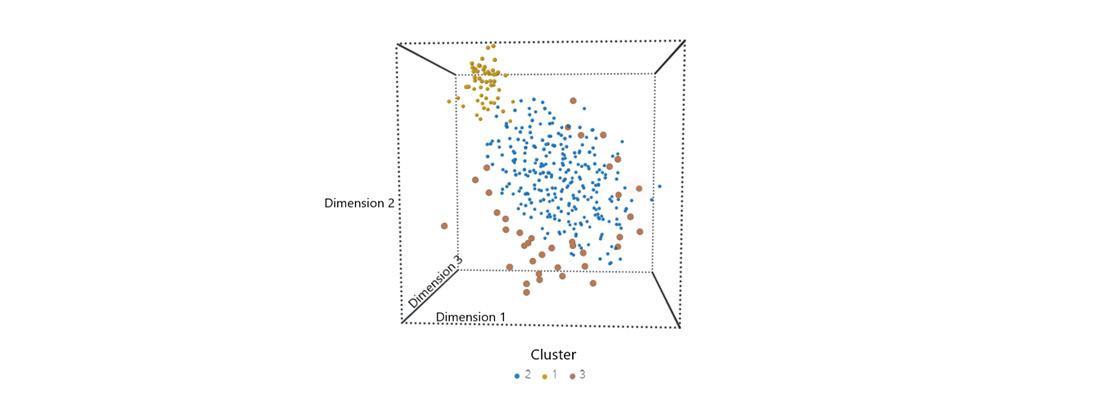

1656 Grouping of Emergency Department-based Cardiac Arrest Patients According to Clinical Features to Assess Patient Outcomes

J Leow, P Shih, J Gao, C Wang, T Lu, C Huang, C Tsai

1667 Pursuit of Optimal Vagal Maneuvers in Stable Supraventricular Tachycardia: A Network Meta-Analysis

SS Immanuel, JE Gotama, Y Sayogo, A Sunjaya, G Tandecxi, CP Anthony, SA Wirawan, K Wibawa, LP Suciadi

1679 Comparison of Pretreatment in European Society of Cardiology Acute Coronary Syndrome Guidelines

İ Ataş, MM Yazıcı, AN Ç, N Parça, US Cerit, M Kaçan, Ö Bilir

Health Equity

1688 Housing Insecurity among Emergency Department Patients with Opioid Use Disorder

CM Shaw, W Covington, LA Walter

1696 Interfacility Transfers from the Emergency Department for Non-contracted Insurance Status Disproportionately Affect Minority Patients

A Holzman, M Aaron, K Nayar, W Rankin, M Tapia, D Rappaport

Trauma

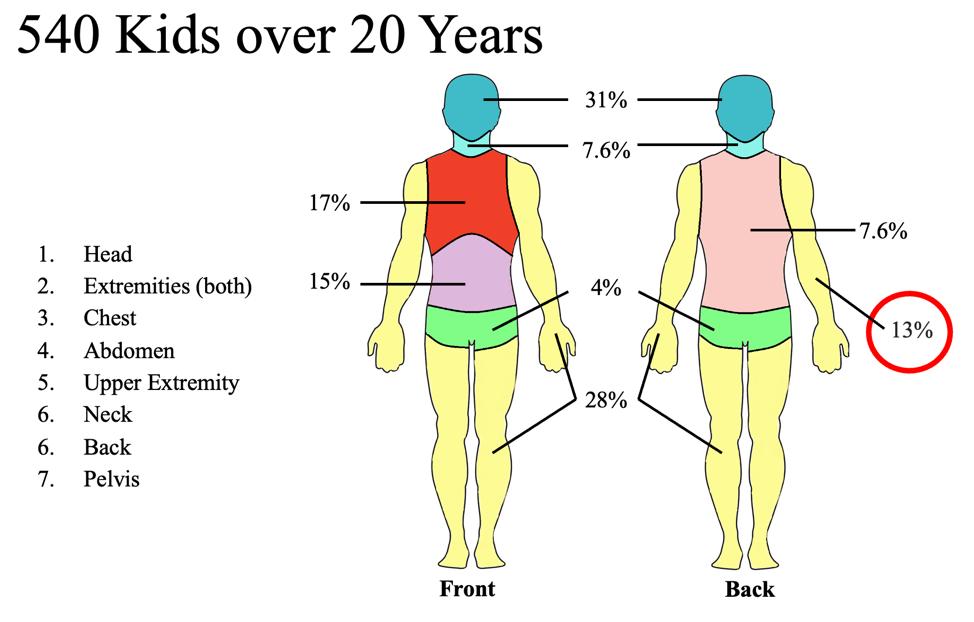

1702 Pediatric Upper Extremity Firearm-related Injuries: A Level I Pediatric Trauma Center Experience

AC Braswell, E Soto, AD Bloom, E Jorge, EF Ransom, RE Aliotta

1710 Completeness and Audibility of Verbal Orders for Medications and Blood Products during Trauma Resuscitation

R Ryan, K Williams, J Aranda, N Jacobson

Pediatrics

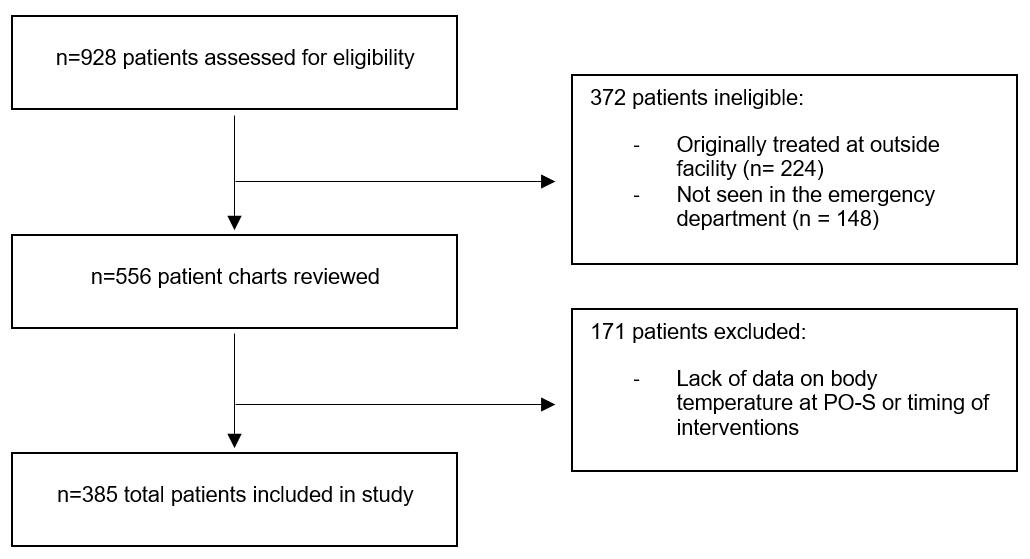

1719 Triage Temperature and Timeliness of Sepsis Interventions in a Pediatric Emergency Department

M Straus, JM Morrison, R Khalaf, J Fierstein, A Miller, D Young, E Melendez

1729 Differences in Admission Rates of Children with Pneumonia Between Pediatric and Community Emergency Departments

G VanGorder, S Lee, Z Jensen, S Boehmer, RP Olympia

Geriatrics

1738 A Geriatric Nurse-led Callback System to Reduce Emergency Department Revisits in Older Adults

J Roh, L Walls-Smith, S Mushtaq, L Gonzalez, V Giles, L Spiegelman, S Sadaat

1744 Trends in Proportion of Delirium Among Older Emergency Department Patients in South Korea, 2017-2022

J Moon, S Kim, D Lim, HK Sung, N Lee, KS Lee

Western Journal of Emergency Medicine:

Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health

Indexed in MEDLINE, PubMed, and Clarivate Web of Science, Science Citation Index Expanded

Table of Contents continued

Toxicology

1755 Factors Associated with Survival to Hospital Discharge in Cardiac Arrest by Poisoning: WAIVOR Score

M Cha, M Song, J Kim

Neurology

1764 Emergency Medicine Residents’ Performance with National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale and Its Impact on Key Stroke-care Metrics

M Roces, T Alacala-Arcos, N Addo, M Boyle, M Hewlett, R Nguyen, A Wong, CR Peabody, DY Madhok

Injury Prevention==

1769 Prevalence and Impact of Violence Against Healthcare Workers in Brazilian Emergency Departments: A National Survey

JM Dorn de Carvalho, SS McGuire, LLR Oliveira, F Bellolio, OT Ranzani, BAM Pinheiro Besen, HP Guimarães, MC Lunardi, AF Mullan, LA Hajjar, IWA Maia

Endemic Infections

1781 National Survey on Infection Prevention and Control in United States Emergency Departments

L Dasari, MLParas, SL Pellicane, EF Searle, A Courtney, JM Shum, KM Boggs, JA Espinola, AF Sullivan, CA Camargo, JD Schuur, ES Shenoy, PD Biddinger

Emergency Medicine Services

1790 Limiting Albuterol Use by EMS at the Start of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Retrospective Analysis of Rapid Deimplementation

R Varughese, SJ Burnett, H Kirk, I Wallis, N Nan, C Ma, D Hostler, BM Clemency

Critical Care

1795 Optimizing Fluid Resuscitation Strategies: A Network Meta-analysis of Effectiveness and Safety for Hemorrhagic Shock Patients in Emergency Settings

FM Aldian, V Visuddho, MV Anggarkusuma, JA Wijaya, AC Lim, G Chandrawira, YE Sembiring, BP Semedi, JJ Dillon

Climate Change

1804 “Predictive Factors and Nomogram for 30-Day Mortality in Heatstroke Patients: A Retrospective Cohort Study”

JRStowell, G Comp, P Pugsley, M McElhinny, M Akhter

Western Journal of Emergency Medicine:

Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health

This open access publication would not be possible without the generous and continual financial support of our society sponsors, department and chapter subscribers.

Professional Society Sponsors

American College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians

California American College of Emergency Physicians

Academic Department of Emergency Medicine Subscriber

Alameda Health System-Highland Hospital Oakland, CA

Arnot Ogden Medical Center Elmira, NY

Ascension Resurrection Chicago, IL

Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist Winston-Salem, NC

Baystate Medical Center Springfield, MA

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Boston, MA

Brigham and Women’s Hospital Boston, MA

Brown University Providence, RI

Capital Health Regional Medical Center Trenton, NJ

Carolinas Medical Center Charlotte, NC

Cedars-Sinai Medical Center Los Angeles. CA

Cleveland Clinic Cleveland, OH

Desert Regional Medical Center Palm Springs, CA

Detroit Medical Center/Wayne State University Detroit, MI

Duke University Hospital Durham, NC

Eisenhower Health

Rancho Mirage, CA

Emory University Atlanta, GA

ESO Austin, TX

Franciscan Health Olympia Fields Olympia Fields, IL

Geisinger Health System

Danville, PA

George Washing University Washington, DC

HealthPartners - Regions Hospital St Paul, MN

Hennepin County Medical Center Minneapolis, MN

Henry Ford Hospital Detroit, MI

State Chapter Subscriber

Arizona Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

California Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Florida Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

International Society Partners

Emergency Medicine Association of Turkey

Lebanese Academy of Emergency Medicine

Henry Ford Wyandotte Hospital Wyandotte, MI

INTEGRIS Health

Oklahoma City, OK

Kaweah Delta Health Care District

Visalia, CA

Kern Medical Bakersfield, CA

Lehigh Valley Hospital and Health Network Allentown, PA

Loma Linda University Medical Center Loma Linda, CA

Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center New Orleans, LA

Maimonides Medical Center Brooklyn, NY

Massachusetts General Hospital Boston, MA

Mayo Clinic College of Medicine Rochester Rochester, MN

Mayo Clinic College in Arizona Phoenix, AZ

Mayo Clinic College in Florida Jacksonville, FL

Medical College of Wisconsin Affiliated Hospitals Milwaukee, WI

Morristown Medical Center Morristown, NJ

Mount Sinai Medical Center Miami Beach

Miami Beach, FL

Mount Sinai Morningside (West) New York, NY

North Shore University Hospital Manhasset, NY

New York - Presbyterian Brooklyn Methodist Hospital Brooklyn, NY

NYU Langone Health - Bellevue Hospital New York, NY

Ochsner Medical Center New Orleans, LA

Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center Columbus, oH

Oregon Health and Science University Portland, OR

Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center Hershey, PA

Prisma Health - University of South Carolina School of Medicine Greenville, SC

California Chapter Division of American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Riverside Regional Medical Center Newport News, VA

Rush University Medical Center Chicago, IL

Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School New Brunswick, NJ

Saint Louis University School of Medicine St Louis, MO

Sarasota Memorial Hospital Sarasota, FL

Seattle Children’s Hospital Seattle, WA

Summa Health System Akron, OH

SUNY Upstate Medical University Syracuse, NY

Swedish Hospital Part of NorthShore Chicago, IL

Temple University Philadelphia, PA

Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center El Paso, TX

The University of Texas Medical Branch Galveston, TX

Trinity Health Muskegon Hospital Muskegon, MI

UMass Memorial Health Worcester, MA

University at Buffalo Buffalo, NY

University of Alabama Medical Center Birmingham, AL

University of Arizona College of MedicineTuscon Tucson, AZ

University of California, Davis Medical Center Sacramento, CA

University of California, San Francisco General Hospital

San Francisco, CA

UCSF Fresno Fresno, CA

University of Chicago, Chicago, IL

University of Cincinnati Medical Center Cincinnati, OH

University of Colorado Denver Denver, CO

University of Florida, Jacksonville Jacksonville, FL

Mediterranean Academy of Emergency Medicine

To become a WestJEM departmental sponsor, waive article processing fee, receive electronic copies for all

please go to http://westjem.com/subscribe or contact:

Stephanie Burmeister

WestJEM Staff Liaison

Phone: 1-800-884-2236

Email: sales@westjem.org

University of Illinois at Chicago Chicago, IL

University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics Iowa City, IA

University of Kansas Health System Kansas City, KS

University of Louisville Louisville, KY

University of Maryland School of Medicine Baltimore, MD

University of Michigan Ann Arbor, MI

University of North Dakota School of Medicine and Health Sciences Grand Forks, ND

University of Ottawa Ottawa, ON

University of Pennsylvania Health System Philadelphia, PA

University of South Alabama Mobile, AL

University of Southern California - Los Angeles General Medical Center Los Angeles, CA

University of Tennessee Knoxville, TN

University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center

Houston, TX

University of Utah School of Medicine

Salt Lake City, UT

University of Vermont Medical Center

Burlington, VT

University of Washington - Harborview Medical Center

Seattle, WA

University of Wisconsin Hospitals and Clinics Madison, WI

Valleywise Health Medical Center Phoenix, AZ

Wellspan York Hospital York, PA

West Virginia University Morgantown, WV

Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine

Dayton, OH

Yale School of Medicine New Haven, CT

The Effect of Dictation on Emergency Medicine Resident Time to Note Completion

Lauren R. Willoughby, MD, MSEd*†

Daniel J. Hekman, MS*†

Benjamin H. Schnapp, MD, MEd†

Section Editor: Muhammad Waseem, MD

Medical College of Wisconsin, Department of Emergency Medicine, Milwaukee, Wisconsin

University of Wisconsin, Department of Emergency Medicine, Madison, Wisconsin

Submission history: Submitted January 1, 2025; Revision received May 28, 2025; Accepted June 9, 2025

Electronically published November 17, 2025

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

DOI 10.5811/westjem.41812

Introduction: Timely documentation of a patient encounter is a necessary component for delivering high-quality healthcare as it has direct impacts on continuity of care. The use of voice recognition software has been integrated into the electronic health record (EHR) to increase efficiency of documentation. We aimed to investigate the impact of dictation use on emergency medicine (EM) residents’ time to note completion.

Methods: We conducted this study in a three-year EM residency program at an academic emergency department. Notes written in the EHR by EM residents were included for analysis. We split notes into two cohorts based on academic year: 2018-19 academic year (AY18-19); and 202122 academic year (AY21-22). We analyzed approximately 37,000 notes per cohort. Dictation was available to all residents in each cohort. The length of the note (measured by character count) and time to note completion (less than or greater than 24 hours) was analyzed.

Results: For both the AY18-19 and AY21-22, the rate of note completion within 24 hours was higher when using dictation compared to typing (odds ratio [OR] 1.3 and OR 2.9, respectively). Aggregated data of both cohorts showed 77.9% of dictated notes were completed within 24 hours compared to 70.9% of typed notes (P < .001). In both cohorts, the average number of characters per note was larger if the note was dictated. For AY18-19, the average was 6,628 characters for dictated notes vs 6,136 for typed notes (P < .05). Similarly, for AY21-22, the average was 6,531 vs 6,347 (P < .05).

Conclusion: The use of dictation by EM residents for note completion resulted in a higher likelihood of the note being completed within 24 hours. [West J Emerg Med. 2025;26(6)1499–1503.]

INTRODUCTION

Timely documentation of a patient encounter is a necessary component for delivering high-quality healthcare as it has a direct impact on continuity of care.1,2 However, many physicians report being unable to complete tasks related to the electronic health record (EHR) during their clinical hours, often requiring remote access to the EHR outside scheduled work time.3 Inefficient documentation processes may contribute to physicians’ spending significant time outside their clinical shifts to finalize patient notes. Initiatives aimed at improving physician well-being have

targeted the reduction of EHR- and documentation-related burdens.4 The Stanford Model of Occupational Well-Being is a widely recognized framework that identifies workplace efficiency as a component influencing physician wellness.5 Within this model, streamlined documentation is highlighted as a critical factor in enhancing workplace efficiency. Therefore, optimizing workplace efficiency by improving interactions with the EHR may support physician wellness. Additionally, the Council of Residency Directors in Emergency Medicine has recommended optimization of the EHR as a best practice for promoting resident wellness.6

Various interventions have been tried to decrease the burden of charting on clinicians. To help increase the efficiency of documentation and decrease the amount of time spent on documenting, some EHR vendors have introduced shortcuts, often called “dot phrases,” which are short texts beginning with “.” that are typed into a note and are then replaced by different, often more lengthy, text (for example, replacing “.wdl” with “within defined limits”). However, a recent study has shown that dot phrases do not affect the time to note completion.7 The use of a medical scribe, a person who accompanies the physician during the patient encounter and documents portions of the chart, has been shown to increase clinician efficiency.8 One study demonstrated that faculty use of scribes can enhance resident educational experiences.9 However, there is a lack of research examining the effects of scribes documenting on behalf of residents, specifically regarding the impact on a resident’s ability to independently and effectively document in the EHR. Another strategy to alleviate the burden of documentation is the integration of voice recognition software. The use of dictation strongly correlated with increased emergency medicine (EM) resident productivity as measured by relative value units per hour.10 However, to our knowledge, there has not been a study investigating the effect of dictation on timely EM resident note completion as an indicator of efficiency. Our primary goal in this study was to determine whether dictated notes were linked to improved documentation efficiency by assessing whether notes are more likely to be completed within 24 hours when dictation is used.

METHODS

Study Setting and Population

The study was conducted in a three-year EM residency program at an academic emergency department (ED). The ED is in a midwestern, small-city urban location with 54 beds and approximately 60,000 patient visits annually. The EM residents were eligible for inclusion if they had worked in the ED uninterrupted between 2017–2022. There were 12 EM residents per year until 2020, after which there were 13 per year. The institution uses M*Modal Fluency Direct (3M Company, Maplewood, MN) for dictation, and a microphone and dictation software integrated with the EHR was available at each workstation and in multiple shared work areas (eg, resident lounge). All residents receive dictation training during residency orientation. Most residents will start a patient note while on shift, but it is not mandatory that they stay at the hospital after their shift to complete their notes. All residents receive personal microphones, can dictate using their personal phone, and can access dictation software remotely; thus, they are able to complete notes at their convenience. Additionally, there is no strict consequence for not completing a note within 24 hours. However, weekly reports are generated, and residents who are frequently delinquent may be placed on an individualized improvement plan or probation based on tardy chart completion.

Population Health Research Capsule

What do we already know about this issue?

Timely documentation is crucial to high-quality patient care as it facilitates continuity among team members.

What was the research question?

We examined whether the use of dictation improves the timeliness of documentation completion.

What was the major inding of the study?

Within two cohorts analyzed, dictation improved timely note completion, with ORs of 1.47 and 2.93, respectively.

How does this improve population health?

Using dictation results in faster time to note completion, enhancing continuity of patient care and supporting clinician wellness by reducing the amount of after-hours work.

Study Protocol

We included notes written by EM residents between 2017–2022. This included notes from an adult ED at an academic medical facility, a pediatric ED, and an affiliated community ED. Although a randomized control study design was considered, we conducted a retrospective study to better reflect real-world use of dictation in actual clinical practice. Data obtained included the note length (total number of characters in the note), whether the note was signed by a resident within 24 hours of the resident assigning him/herself to the patient, and whether dictation was used to complete any portion of the note. We collected data on note length to assess whether it acted as a confounder, specifically examining whether shorter notes are associated with faster chart completion. For this study, we defined efficiency as documentation timeliness, measured by the completion of notes within 24 hours. This timeframe was selected as it aligns with institutional documentation standards and logically supports continuity of care among the healthcare team. We did not assess quality of the note, although this is also important. Each resident was assigned a study identification number, and the identification key was accessible only by the data scientist on the study team (DH) who did not perform the statistical analysis. Patient information was de-identified for the author performing the data analysis (LW). Data was imported to Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA) for analysis.

Data Analysis

Analysis was run on notes completed by two cohorts of residents: the 2018-19 academic year (AY18-19) and the 2021-22 academic year (AY21-22). We excluded AY19-20 and AY20-21 due to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on clinical volumes and related interruptions to clinical practice. Notes that included any portion completed using dictation were identified by an internal flag within the EHR. We stratified notes by disposition to account for the fact that some notes may be completed sooner if they have a higher priority disposition. For example, the note for a patient being transferred to an outside facility needs to be completed before transfer. Each patient note was coded into one of two categories based on their disposition: high priority (“Admit,” “Transfer to another facility,” “Against medical advice”); or regular priority (all other disposition codes that were not a high priority). Notes for patients handed off during shift change, or “sign out” patients, were not categorized as high priority.

We used a logistic regression model to adjust for covariates potentially affecting time to note completion. Predictor variables included dictation use, note length, resident’s postgraduate year (PGY), and note priority. Additionally, one resident was excluded from the analysis due to an off-schedule progression through the program and graduation. This study was deemed exempt as quality improvement by the institutional review board.

RESULTS

We included 37,778 notes in the analysis of the AY18-19 cohort and 37,716 notes of the AY21-22 cohort. Of the 37,778 notes in the AY18-19 cohort, 35,162 (93.08%) were non-priority dispositions and 2,616 (6.92%) were highpriority dispositions. Of 37,716 notes in the AY21-22 cohort, 36,692 (97.28%) were non-priority and 1,024 (2.72%) were high priority.

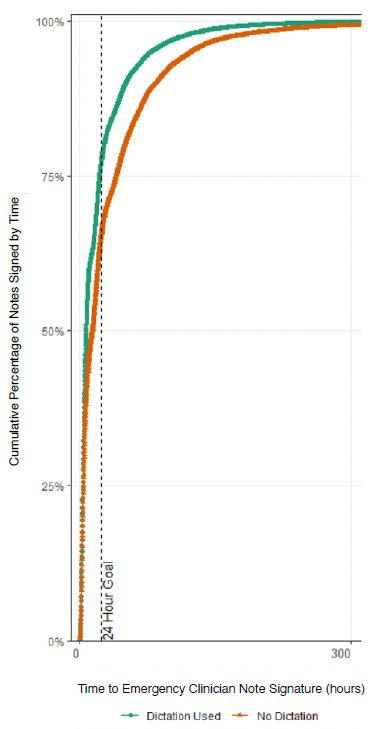

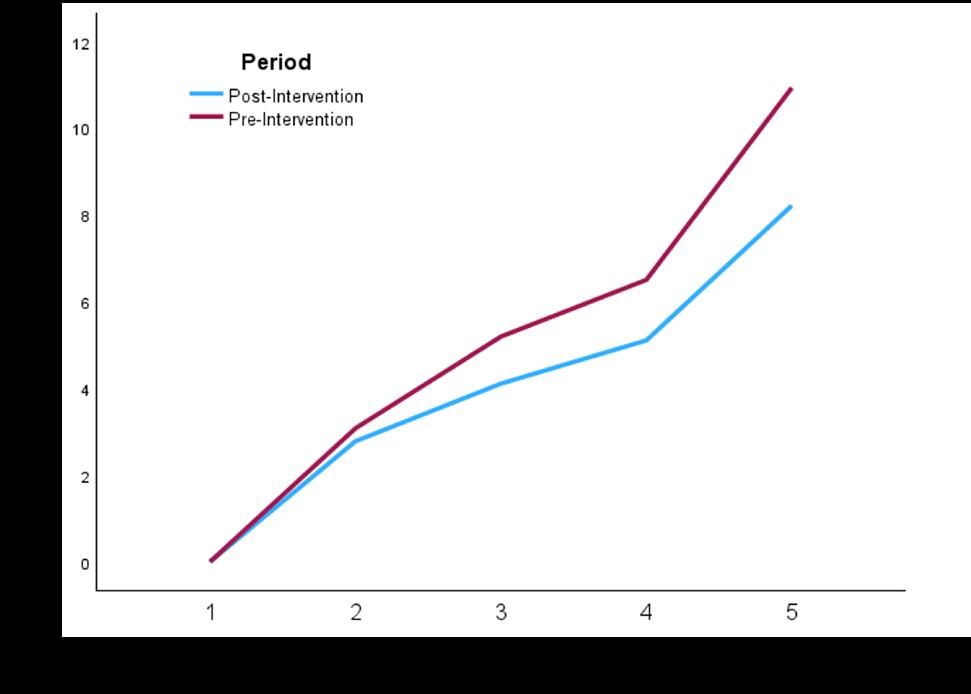

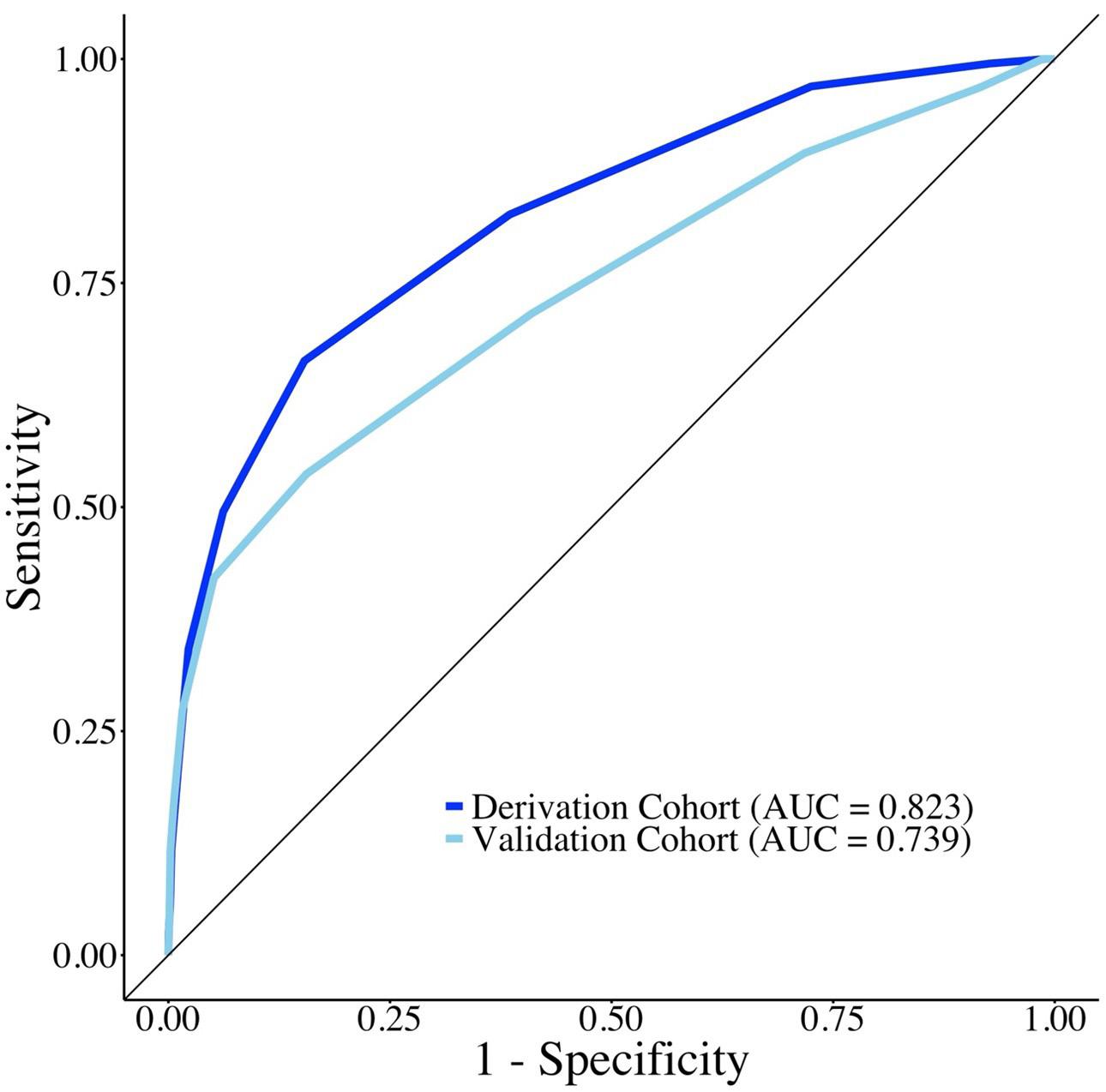

In the AY18-19 cohort, the unadjusted rate of note completion within 24 hours was higher when using dictation compared to typing (odds ratio [OR] 1.3). Similarly, in the AY21-22 the unadjusted rate of note completion within 24 hours was higher when using dictation compared to typing (OR 2.9). Aggerated data from the two cohorts showed that 77.9% of dictated notes were completed within 24 hours vs 70.9% of typed notes (P < .001). The Figure depicts the overall aggregated time to note completion for both academic years with and without dictation. In both the AY18-19 and AY21-22 cohorts, the logistic regression model was statistically significant, and all the predictors were significant as well. Additionally, the AY18-19 model correctly predicted timely note completion approximately 60% of the time, and the AY21-22 model correctly predicted completion of notes in 24 hours in the analysis sample approximately 68% of the time. The R2 for AY18-19 was .0453, and the R2 for AY21-22 was .1151.

In the AY18-19 cohort, dictation use and disposition priority status were both strong positive predictors of timely

Figure 1. Overall aggregated time to note completion by emergency medicine residents for academic years 2018-2019 and 2021-2022 with and without dictation.

note completion while an increase in note length, whether dictated or typed, was associated with a decrease in the likelihood of timely note completion. The predicted probability of an average length, regular-priority note being completed on time by a PGY-3 resident when dictation was not used was 0.63, and 0.71 when dictation was used (OR 1.47). Timely note completion was about one and a half times more likely with dictation than without after controlling for other explanatory variables.

In AY21-22, most of the same effects were observed, with dictation use predicting an even greater increase in the likelihood of timely note completion. After adjusting for other predictors, the OR for note completion within 24 hours with

Effect of Dictation on EM Resident Time to Note Completion

dictation use was 2.93, aligning with the simple contingency analysis. In the AY18-19, the average number of characters per typed note was 6,136 compared to dictated notes, which was significantly larger at 6,628 (P < .05). In the AY21-22, the average number of characters per typed note was 6,347; the average number of characters per dictated note was significantly larger at 6,531 (P < .05).

DISCUSSION

Dictation is widely used among EM residents—at least in this residency program. In both cohorts analyzed, the rate of note completion within 24 hours was more likely with dictation than without after controlling for other explanatory variables. The use of dictation improving documentation efficiency is a crucial finding as other interventions, such as dot phrases, have not been proven to increase efficiency.6 (Interestingly, the integration of artificial intelligence may enhance efficiency of documentation; however, this is in still in the preliminary stages of evaluation.11) The relatively low R2 suggests that even though dictation and the other predictors have statistically significant relationships with timely note completion, many external factors played an important role in note completion, which our study was not able to capture. Additionally, there is a noteworthy difference in the ORs between the two cohorts with respect to time to note completion and note length. The reason for these differences is unclear and warrants further investigation, potentially through focus groups or qualitative methods, to explore differences in workflows, training, or other contextual factors between the resident cohorts.

While dictation use was associated with a higher rate of note completion within 24 hours, it did result in longer note length by several hundred characters. It is important to acknowledge that while the note length was longer in dictated notes, we did not assess the quality of included information. It is possible that the additional included information was beneficial and that dictation facilitates easier inclusion of helpful medical information and decision-making. However, it is also possible that dictation results in a greater volume of low-quality information being included in the note. Significant inter-physician variation has been previously noted in EHR data and has been cited as a possible barrier to safe and efficient care.12 Assessment of the quality of dictated vs typed notes represents an avenue for further study. Additionally, dictation is also known to cause errors in transcription, some of which can be clinically significant.13 Exploring the impact of these errors on resident documentation efficiency and clinical care could also be investigated further.

Finally, the association between dictation and increased note completion within 24 hours suggests potential downstream effects on resident wellness, as it may contribute to greater workplace efficiency and reduce the need to complete notes outside clinical shifts. This relationship warrants further investigation.

LIMITATIONS

There are several limitations to this study. First, because we conducted this study at a single institution generalizability may be limited; other implementations of dictation could provide different results. Additionally, notes were included for analysis if any portion of the note was completed with dictation, but there was no data on how much of the note was completed with dictation. Further, not all notes written by residents were included for analysis. Notes written at the Veterans’ Administration hospital and the unaffiliated community site were not included as these sites represented a small minority of the residents’ training experience and used a different EHR. Finally, factors that may influence time to note completion, such as priority of disposition, were accounted for; however, there are additional factors that may impact time to note completion that were not accounted for, such as patient volume or overall shift workload. Future areas of investigation may include conducting focus groups or interviews to further investigate the perception of residents on what factors influence time to note completion and how dictation influences efficiency.

CONCLUSION

The use of dictation by residents for note completion results in a higher likelihood of the note being completed within 24 hours.

Address for Correspondence: Lauren Willoughby, MD, MSEd, Medical College of Wisconsin, Department of Emergency Medicine, Hub for Collaborative Medicine, 8701 Watertown Plank Rd, Milwaukee, WI 53226. Email: lwilloughby@mcw.edu.

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. No author has professional or financial relationships with any companies that are relevant to this study. There are no conflicts of interest or sources of funding to declare.

Copyright: © 2025 Willoughby et al. This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) License. See: http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/

REFERENCES

1. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, et al. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831-41.

2. Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, et al. Transitions of Care Consensus Policy Statement American College of Physicians-Society of General Internal

Medicine-Society of Hospital Medicine-American Geriatrics SocietyAmerican College of Emergency Physicians-Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(8):971-6.

3. Gardner RL, Cooper E, Haskell J, et al. Physician stress and burnout: the impact of health information technology. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2019 Feb 1;26(2):106-14.

4. Sinsky CA, Biddison LD, Mallick A, et al. Organizational evidencebased and promising practices for improving clinician well-being. NAM Perspect. 2020 Nov 2;2020:10.31478/202011a.

5. The Stanford Model of Occupational Well-BeingTM. WellMD & WellPhD. Available at: [https://wellmd.stanford.edu/about/modelexternal.html]. Accessed May 15, 2025.

6. Parsons M, Bailitz J, Chung AS, et al. Evidence-based interventions that promote resident wellness from the Council of Emergency Residency Directors. West J Emerg Med. 2020 Feb 21;21(2):412-22.

7. Perotte R, Hajicharalambous C, Sugalski G, et al. Characterization of electronic health record documentation shortcuts: Does the use of dotphrases increase efficiency in the emergency department? AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2022;2021:969-78.

8. Addesso LC, Nimmer M, Visotcky A, et al. Impact of medical scribes on provider efficiency in the pediatric emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2019;26(2):174-82.

9. Ou E, Mulcare M, Clark S, et al. Implementation of scribes in an academic emergency department: the resident perspective. J Grad Med Educ. 2017 Aug;9(4):518-22.

10. Egan HM, Swanson MB, Ilko SA, et al. High-efficiency practices of residents in an academic emergency department: a mixed-methods study. AEM Educ Train. 2020;5(3):e10517.

11. Using an AI assistant to reduce documentation burden in family medicine evaluating the Suki assistant. 2021. Available at: [https://www.aafp.org/ dam/AAFP/documents/practice_management/innovation_lab/report-sukiassistant-documentation-burden.pdf]. Accessed February 4, 2024.

12. Cohen GR, Friedman CP, Ryan AM, et al. Variation in physicians’ electronic health record documentation and potential patient harm from that variation. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(11):2355-67.

13. Goss FR, Blackley SV, Ortega CA, et al. A clinician survey of using speech recognition for clinical documentation in the electronic health record. Int J Med Inform. 2019;130:103938.

Program Director Perspectives on the Impact of the Proposed 48-Month Emergency Medicine Residency Requirement: A National Survey

Richard Austin, MD*

Chinmay Patel, DO†

Kristin Delfino, PhD‡

Sharon Kim, PhD*

Southern Illinois University, School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Springfield, Illinois

Baylor Scott & White All Saints Medical Center, Department of Emergency Medicine, Fort Worth, Texas

Southern Illinois University, School of Medicine, Department of Surgery, Springfield, Illinois

Section Editor: Kendra Parekh, MD, MHPE

Submission history: Submitted June 2, 2025; Revision received October 15, 2025; Accepted October 15, 2025

Electronically published November 26, 2025

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem DOI 10.5811/westjem.48359

Introduction: In early 2025, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) announced proposed revisions to emergency medicine (EM) residency training to include substantial changes to the length of training programs, required rotations, and structured experiences. To date, no published national survey has sought to determine how these changes would impact individual programs.

Methods: Over a three-week period in April 2025, we anonymously surveyed program directors or their designees online through the Council of Residency Directors in Emergency Medicine listserv. Survey respondents were asked about the impact the changes would have on their programs and their overall opinions of the proposed 48-month minimum requirement.

Results: A total of 86 program directors responded to the survey (response rate of 29.9%) with representative samples from current three-year (83.7%, 72/86) and four-year (16.3%, 14/86) programs. Most program directors reported that they would have to make significant revisions in either structured experiences, required rotations, or both. Most survey respondents from three-year programs (52/72) do not support the proposed changes, whereas all respondents from four-year programs (14/14) do support the changes (P<.001).

Conclusion: Proposed program requirements may require modifications in both three- and four-year programs; 33 of the 86 program directors surveyed reported that would need more than one year to meet the requirements, if adopted. This raises the concern that programs may not be prepared to implement the revisions within the proposed timeline, potentially impacting resident education and the future EM workforce. The ACGME should consider a staged rollout of requirements to allow them to be thoughtfully implemented in a meaningful way. [West J Emerg Med. 2025;26(6)1504–1509.]

INTRODUCTION

On February 12, 2025, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) proposed significant revisions to the program requirements for emergency medicine (EM) residency training in the United States, with the most notable change being the standardization of training length to 48 months for all programs, effective July 1, 2027.1 This proposed change has generated considerable discussion and

debate within the EM community, with concerns raised about its potential impact on resident education, program finances, and the EM workforce. Currently, most programs are three years in length, with four-year programs comprising less than 25% of EM residency programs in the US.2

Approximately 60% of EM program directors (PD) (173/289) from the ACGME database completed a survey created by the Program Requirements Writing Group 3, which

found that summed averages for necessary experiences were 41.6 months for three-year programs and 50.7 months for four-year programs. This survey has subsequently been used as justification for the proposed new program requirements, including the 48-month minimum program length. However, the survey did not specifically ask about support for a change from three to four years of training, and it was not designed to examine the impact of any potential changes. The ACGME’s rationale for this change includes concerns about declining board pass rates, potentially attributed to shorter EM shifts and fewer patient encounters during training.4 Yet the available published data show that graduates of three- and four-year programs perform similarly in clinical practice and on board pass rates. 5,6

To further explore the perceived challenges and opportunities associated with this change, we surveyed EM PDs on the changes that would be required within their programs and anticipated challenges with the new requirements, and we gauged their support for the proposed requirement of 48 months of training for all EM programs.

METHODS

We conducted a national cross-sectional survey of EM PDs, or their selected designees (defined as a faculty member delegated by the PD or other residency leadership), from ACGME-accredited EM residency programs in the US over a three-week period in April 2025. After we developed the survey instrument it was piloted for content validity, clarity, and relevance by four members of our educational leadership teams who have experience in program leadership and surveybased research. All feedback was incorporated into the survey, which was approved by our institutional review board as an exempt study. The survey was designed on SurveyMonkey (Momentive Inc., San Mateo, CA) and disseminated to EM PDs through the Council of Residency Directors (CORD) in Emergency Medicine Program Director list-serv. Reminders were sent at one-week intervals for a total of three times. At the time of the study there were 288 PDs in ACGMEaccredited EM programs.

The survey (Appendix A) consisted of 11 questions and was divided into three sections: demographic information; curricular changes; and reflection. In the section on proposed curricular changes, participants were asked to assume that the program requirements had been adopted and to answer questions on anticipated changes to their program’s required rotations (62 weeks at primary emergency department [ED], low-resource ED, high-resource ED, low-acuity area, critical care, pediatric intensive care unit, pediatric ED, administration/quality assurance, toxicology/addiction medicine, and emergency medical services). They were then asked about anticipated changes that would be necessary to meet the required structured experiences (non-laboratory diagnostics such as ultrasound, telemedicine, primary assessment and decision-making, airway management,

Population Health Research Capsule

What do we already know about this issue?

The ACGME has proposed major changes to emergency medicine (EM) training.

What was the research question?

How do program directors view the proposed ACGME changes and what resources are needed to comply?

What was the major finding of the study?

33.6% of 3-year and 100% of 4-year programs support the change to 48 months minimum residency training in emergency medicine (P < .001).

How does this improve population health?

The study identifies changes that EM programs would need to implement meet new standards, to ensure the future workforce is well-prepared to deliver quality care.

ophthalmologic procedures, acute psychiatric emergencies, sensitive exams, transitions of care, and observation medicine). The final section of the survey included questions on the time needed to adopt the 48-month format, additional resources required (additional funding aside from salary, additional training sites, additional core faculty, additional clinical faculty, more protected time, additional simulation or procedure lab time), and agreement on the proposed changes. We summarized categorical survey responses with frequencies and percentages. Chi-square tests were used to evaluate associations. P-values < .05 were considered statistically significant. We performed analysis using SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

A total of 92 respondents completed the survey. However, six were excluded because they did not identify as either a PD or their designee, and their data was not included in the analysis. In total, 86 EM programs were included in the analysis of the survey data for a final response rate of 29.9%. Of the 86 PDs who completed the survey, 72 (83.7%) were from three-year programs and 14 (16.3%) from four-year programs, which is similar to the breakdown of three- and four-year programs currently listed on the Emergency Medicine Residents’ Association Match website.7 Most programs were university-based (33, 38.4%), followed

Impact of the Proposed 48-Month EM Residency Requirement

by community-based university-affiliated (31, 36%), and community-based (22, 25.6%). Participant programs were geographically representative (Table) of the EM academic community based on Fellowship and Residency Electronic Interactive Database Access geographic regions.7

Curriculum Changes

Of the 86 PDs who responded to the survey, 50 (58%) anticipated needing to make three or more changes to their curricula to meet the required nine structured experiences (Table). This was not significantly different between threeand four-year programs. Of the 86 respondents, 14 (16%) reported already having all the required rotations in the proposed requirements, and 34 (40%) reported that they would

need to add three or more rotations. Forty-four respondents (51.2%) indicated that they would be likely to increase their complement of residents, whereas 12 (14%) indicated that they would likely decrease the number of residents. Twentyfive respondents (29.1%) indicated that they were unlikely to change their complement, and five respondents (5.8%) did not answer the question. Most of the programs that would look to expand their complement were currently three-year programs (42/44, 95.5%).

Time Needed

Forty-nine (57%) PDs indicated readiness for all the changes within a one-year period, while 33 (38.4%) reported they would require more than one year to prepare, 20 (23%)

Table. Survey results comparing three- and four-year programs by demographic region, program type, time required to implement changes, additional resources required to implement changes, agreement on 48 months of training, total changes needed in experiences, and total changes needed in rotations.

What geographic region is your program in (as listed in FRIEDA)? East North Central (IL, IN, MI, OH, WI)

East South Central (AL, KY, MS, TN)

(NJ, NY,

(AZ, CO, ID, MT, NM, NV, UT, WY)

New England (CT, MA, ME, NH, RI, VT)

(AK, CA, HI, OR, WA)

South Atlantic (DC, DE, FL, GA, MD, NC, SC, VA, WV)

West North Central (IA, KS, MN, MO, ND, NE, SD)

West South Central (AR, LA, OK, TX)

What best describes your program?

Given your current resources, how much time do you feel you would need to create the new rotations and experiences required in the new rules?

FRIEDA, Fellowship and Residency Electronic Interactive Database Access.

Table. Continued.

What additional resources would you require to meet the new requirements?*

Do you agree with the change to require 48 months of training for all EM programs?

changes needed in required rotations

*Not mutually exclusive. EM, emergency medicine; FRIEDA, Fellowship and Residency Electronic Interactive Database Access.

would require two years, and 13 (15%) would require more than three years to prepare.

Overall Support

Of the PDs of four-year programs, 100% (14/14) supported the change to a minimum 48 months of residency training. However, only 21% (15/72) of three-year PDs supported the change (P<.001).

DISCUSSION

Structured Experiences

Our survey results indicate that the new program

requirements would require a substantial need for curricular revision, which impacts programs differently. For the new “experiences” requirement, only one PD surveyed reported already having all components in place. By contrast, 36% of PDs (31/86) reported that they would probably require one to two changes, and 26% (22/86) would have to make ≥ 5 curricular changes to meet the “experiences” requirements. Curricular revision, including time to pilot, revise, and assess the curricula, is a time-intensive process that can take over a year.

Required Rotations

The required rotations also pose challenges for programs.

Residency Requirement

While 16% (14/86) reported already having all required rotations, 40% (34/86) of the PDs surveyed reported that they would require ≥ 3 revisions to their rotations. When these new rotations require a new training site, such as adding a low-resource ED, it takes a considerable amount of time to research sites and reach agreements. These external sites can also impact the funding of programs through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.8 Additionally, new rotations may require the addition of new faculty, more faculty development, and institutional agreements that cost money and take time.

Time Needed

While 57% of the PDs surveyed (49/86) reported readiness for changes in one year, 38% (33/86) reported they would need more than one year to prepare for the new requirements. This affected both three-year (28/72, 39%) and four-year (5/14, 36%) programs. More concerning is that 15% (13/86) of the PDs surveyed anticipated needing more than three years to prepare for the new program requirements. If those programs were truly unable to prepare in the time frame proposed by the Residency Review Committee (RRC) and decided to close their programs, this could have a major impact on the number of trainees in EM. Additionally, should the RRC-EM grant exceptions or extensions to some programs transitioning to a 48-month format, it could create a competitive advantage to those programs in resident recruitment.

Overall Support

While overall support for the change to 48 months of training was universal for the PDs of four-year programs, there was considerable disagreement among the PDs of threeyear programs, with only 15 (22%) supporting the change and 52 (78%) opposing. Our findings of support for a 48-month training requirement mirror a previous study that showed a strong correlation between the current length of a program and its PD’s support for that format.9

There has been robust discussion regarding the proposed changes since they were presented. Emergency medicine is not alone in considering lengthening residency training time. Family medicine has also discussed a transition to a 48-month training program, which would entail more study and a gradual transition rather than a sudden turnaround.10 The majority of EM program directors surveyed indicated that they would be likely to increase their complements of residents, which could significantly impact the future workforce in EM. Further study is needed to determine how these complement changes may affect the total number of residency spots available in EM each year. More study is needed to fully understand the impacts these changes would have on EM training programs, as well as their impact on the costs involved, especially when considering the lack of evidence to support the extension of training.

LIMITATIONS

The results of this survey do not include all EM residency programs in the United States, as not all programs are part of CORD, and not all members participate in the list-serv we used to disseminate the survey. Additionally, only 29.9% of programs responded to the survey, creating a significant risk of non-responder bias; however, an appropriate representation of programs both geographically and in terms of length of training was included, which provides support that the data are appropriately representative of the general EM academic community. The narrow three-week window to respond also may have impacted the total number of responses. Finally, we did not collect data on whether the respondent was a program director or their designee, only that they attested to being either the PD or a designee.

CONCLUSION

Most of the program directors who responded to a survey on the proposed new minimum of 48 months training in emergency medicine were opposed to the change, and a significant minority reported being unprepared to implement the new requirements within one year as proposed by the RRC-EM. If the ACGME does adopt the proposed program requirements in total, multiple years may be required for programs to create new and effective curricula and rotations. More study is needed on the impact of the proposed changes that focuses on the outcomes of graduates. Previous studies have already shown us that graduates of three- and fouryear programs perform similarly on the American Board of Emergency Medicine certifying exam and in clinical practice.5,6 The ACGME should consider a phased rollout of new requirements to ensure programs have time to thoughtfully and meaningfully adhere to the new requirements in a way that is beneficial to their trainees.

Address for Correspondence: Richard Austin, MD, Southern Illinois University, School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, 701 North First Street, Springfield, IL 62781. Email: raustin@siumed.edu.

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. No author has professional or financial relationships with any companies that are relevant to this study. There are no conflicts of interest or sources of funding to declare.

Copyright: © 2025 Austin et al. This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) License. See: http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/

REFERENCES

1. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Emergency Medicine. 2025. Available at: https://www.acgme. org/globalassets/pfassets/reviewandcomment/2025/110_ emergencymedicine_rc_02122025.pdf. Accessed March 2, 2025.

2. Nelson LS, Calderon Y, Ankel FK, et al. American Board of Emergency Medicine report on residency and fellowship training information (2021‐2022). Ann Emerg Med. 2022;80(1):74‐83.

3. Regan L, McGee D, Davis F, et al. Building the future curriculum for emergency medicine residency training. J Grad Med Educ. 2025;17(2):248-53.

4. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Emergency Medicine Summary and Impact of Major Requirement Revisions. 2025. Available at: https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/ pfassets/reviewandcomment/2025/110_emergencymedicine_ impact_02122025.pdf. Accessed March 2, 2025.

5. Beeson MS, Barton MA, Reisdorff EJ, et al. Comparison of

performance data between emergency medicine 1-3 and 1-4 program formats. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2023;4(3):e12991.

6. Nikolla DA, Zocchi MS, Pines JM, et al. Four- and three-year emergency medicine residency graduates perform similarly in their first year of practice compared to experienced physicians. Am J Emerg Med. 2023;69:100-7.

7. Emergency Medicine Residents’ Association. EMRA Match. 2025. Available at: https://www.match.emra.org. Accessed March 2, 2025.

8. Association of American Medical Colleges. Medicare Payments for Graduate Medical Education: What Every Medical Student, Resident, and Advisor Needs to Know. Association of American Medical Colleges. 2025. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/media/71701/ download?attachment. Accessed September 10, 2025.

9. Hopson L, Regan L, Gisondi MA, et al. Program director opinion on the ideal length of residency training in emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23(7):823-7.

10. Green LA, Miller WL, Frey JJ 3rd, et al. The time is now: a plan to redesign family medicine residency education. Fam Med. 2022 Jan;54(1):7-15.

A Qualitative Study of Senior Residents’ Strategies to Prepare for Unsupervised Practice

Max Griffith, MD*

Alexander Garrett, MD*

Bjorn K. Watsjold, MD, MPH*

Joshua Jauregui, MD, MHPE*

Mallory Davis, MD, MPH†

Jonathan S. Ilgen MD, PhD*

Section Editor: Abra Fant, MD

University of Washington, Department of Emergency Medicine, Seattle, Washington University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Department of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan

Submission history: Submitted July 11, 2025; Revision received October 10, 2025; Accepted October 13, 2025

Electronically published November 26, 2025

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem DOI 10.5811/westjem.48914

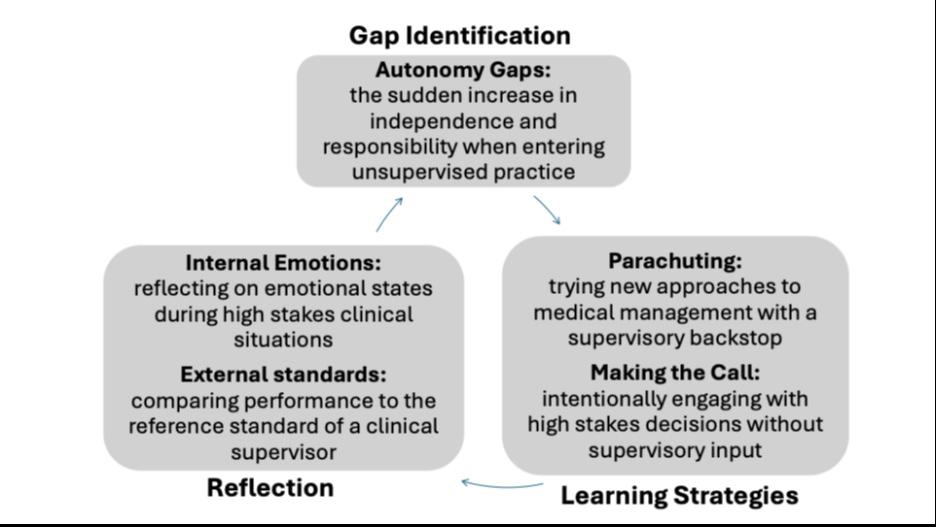

Introduction: As emergency medicine (EM) residents prepare for the transition into unsupervised practice, their focus shifts from demonstrating competencies within familiar training environments to anticipating their new roles and responsibilities as attending physicians, often in unfamiliar settings. Using the self-regulated learning framework, we explored how senior EM residents proactively identify goals and enact learning strategies leading up to the transition from residency into unsupervised practice.

Methods: In this study we used a constructivist grounded theory approach, interviewing EM residents in their final year of training at two residency programs. Using the self-regulated learning framework as a sensitizing concept for analysis, we conducted inductive, line-by-line coding of interview transcripts and grouped codes into categories. Theoretical sufficiency was reached after 12 interviews, with four subsequent interviews producing no divergent or disconfirming examples.

Results: We interviewed16 senior residents about their self-regulated learning approaches to preparing for unsupervised practice. Participants identified two types of gaps that they sought to address prior to entering practice: knowledge/skill gaps, and autonomy gaps. We employed specific workplace learning strategies to address each type of gap, which we have termed cherry-picking, case-based hypotheticals, parachuting, and making the call, and reflection on both internal and external sources of feedback to assess the effectiveness of these learning strategies. This study presents participants’ identification of gaps in their residency training, their learning strategies, and reflections as cyclical processes of self-regulated learning.

Conclusion: In their final months of training EM residents strategically leverage learning strategies to bridge gaps between their self-assessed capabilities and those they anticipate needing to succeed in unsupervised practice. These findings show that trainees have agency in how they use goal setting, strategic actions, and ongoing reflection to prepare themselves for unsupervised practice. Our findings also suggest tailored approaches whereby programs can support learning experiences that foster senior residents’ agency when preparing for the challenges of future practice. [West J Emerg Med. 2025;26(6)1510–1518.]

INTRODUCTION

Competency-based medical education frameworks provide scaffolding and accountability to ensure that emergency medicine (EM) trainees develop the necessary

knowledge and skills for unsupervised practice.1,2 While competency-based medical education frameworks provide a roadmap for residents to deliberately practice the core elements of EM, graduates of EM training programs often

lament the inevitability of encountering new challenges when entering practice.3,4 This suggests that the training experiences that advance residents’ competencies (what a resident does to demonstrate their abilities) must be done in conjunction with efforts to advance residents’ capabilities (the things they can think or do in future practice.)5 While competencies are often embedded in the tools that training programs use to assess residents,1,6,7 capability development requires trainees to engage in dynamic self-assessment8 to consider what they can work on now to prepare themselves for future transitions. A capability approach looks beyond training residents who are simply competent, aiming instead to develop trainees who can self-diagnose their future learning needs and enact learning strategies to achieve their goals.9–11

Self-regulated learning (SRL) provides a framework to study how senior residents approach workplace learning to prepare for their transitions into unsupervised practice.12 The SRL theory proposes that individuals are “metacognitively, motivationally, and behaviorally active participants in their own learning process.”13 This provides a structure to consider how residents might assess their abilities and modulate their activities during training.14 These SRL behaviors are often depicted as a cycle whereby individuals set goals, employ learning strategies to attain these goals, and reflect on their progress.14 This cycle is context-dependent, shaped by learner characteristics (eg, knowledge, prior experiences, emotions, and confidence) as well as by the learning environment (structure, supports, and cultural expectations).15 Learnerrelated factors such as autonomy, efficacy, and accumulated experience have been shown to support engagement with SRL,16 suggesting that residents in the final months of training have nuanced and mature self-regulated learning habits.

The end of residency training is a compelling period to examine SRL as it relates to capability development. As residents prepare for the transition into unsupervised practice, their focus shifts from demonstrating advanced competencies within familiar training environments7 to anticipating their performance with new roles and responsibilities as attending physicians, often in unfamiliar practice environments.17–21 In recent work exploring how senior EM residents conceptualized their preparedness for unsupervised practice, we found that trainees were cognizant of the inevitable mismatch between what they learned in training and what they would be expected to do in unsupervised practice.3

We were struck by trainees’ sense of agency in their reflections,22 particularly by how they set goals and leveraged their learning environments to create learning strategies that addressed their anticipated future practice needs. Recognizing that these findings have not been described previously in the literature, we returned to our data using the lens of SRL to explore how senior residents proactively identified goals and enacted learning strategies specific to their transitions from residency into unsupervised practice. By elaborating these strategies, we hope to provide insights that educators

Population Health Research Capsule

What do we already know about this issue? Emergency medicine (EM) residency graduates are often anxious about the unfamiliar clinical problems that they will encounter in unsupervised practice.

What was the research question? What workplace learning strategies do EM senior residents use to prepare themselves for unsupervised practice?

What was the major finding of the study? We describe self-regulated learning strategies: cherry picking, case-based hypotheticals, parachuting, and making the call.

How does this improve population health? These learning strategies can improve new physicians’ preparedness to treat patients without supervision in a variety of clinical settings.

can use to tailor their support for senior trainees during these important transition periods.

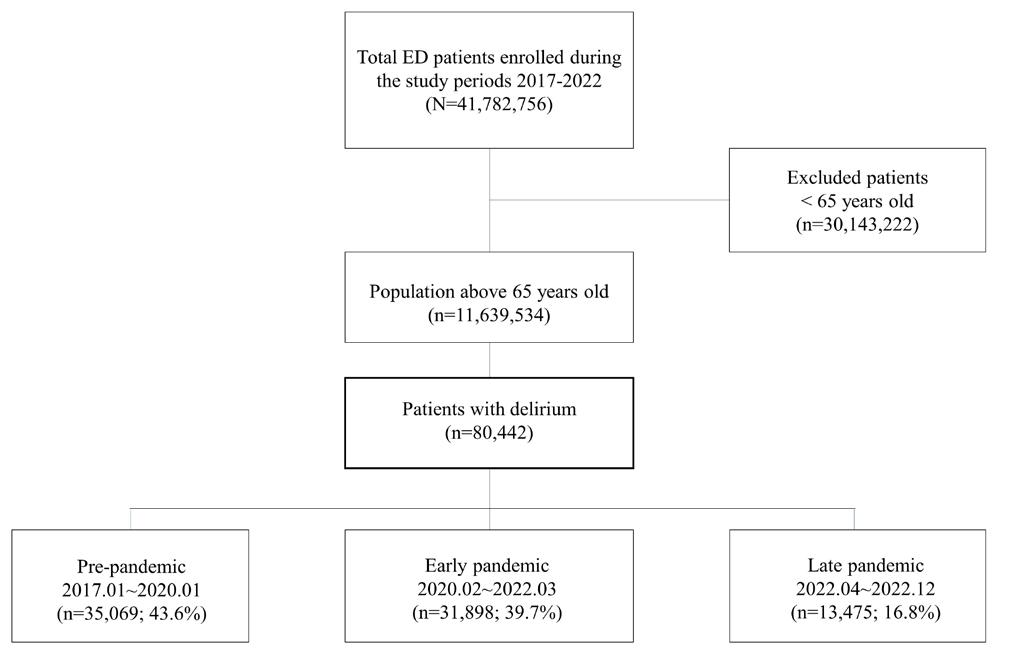

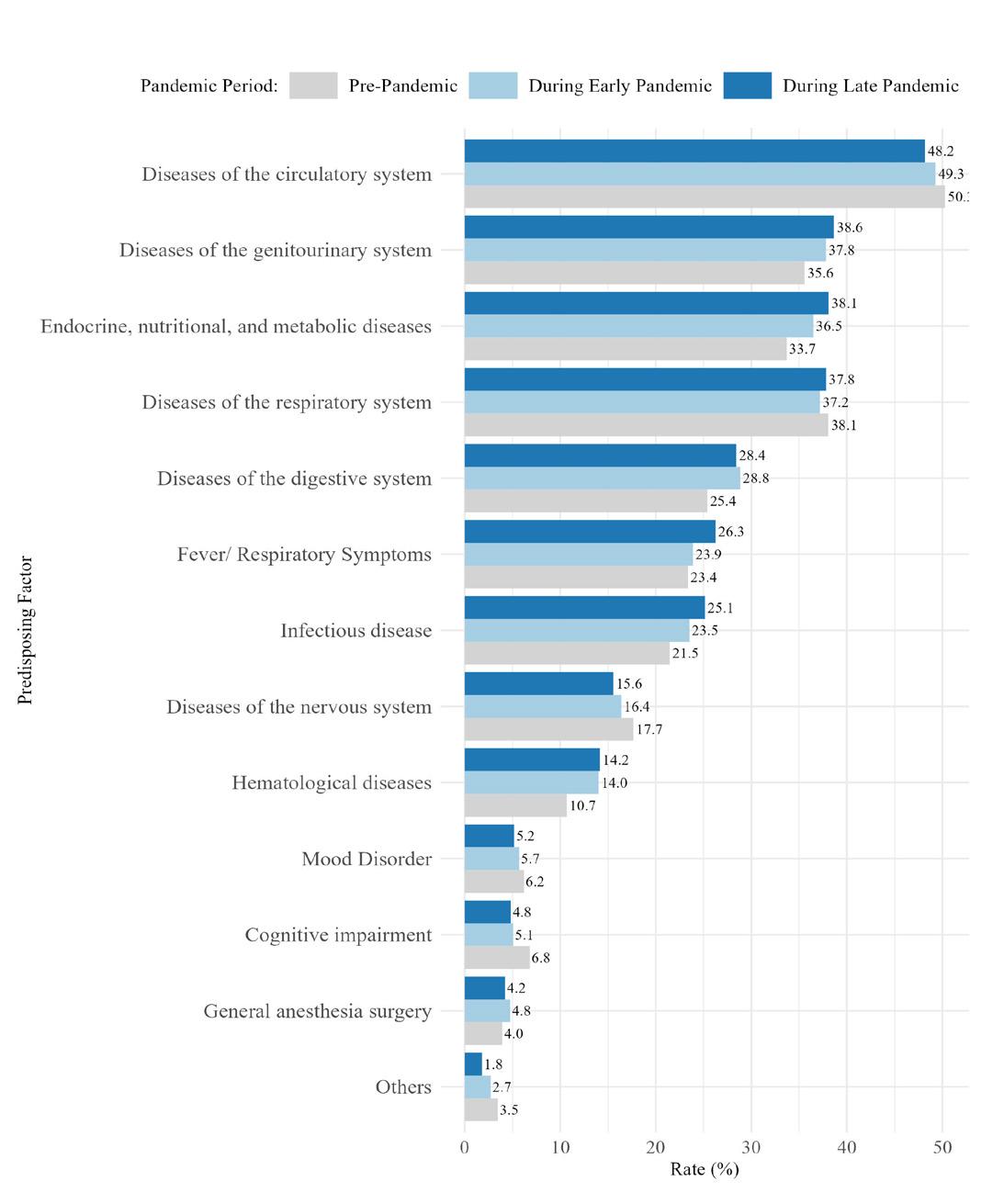

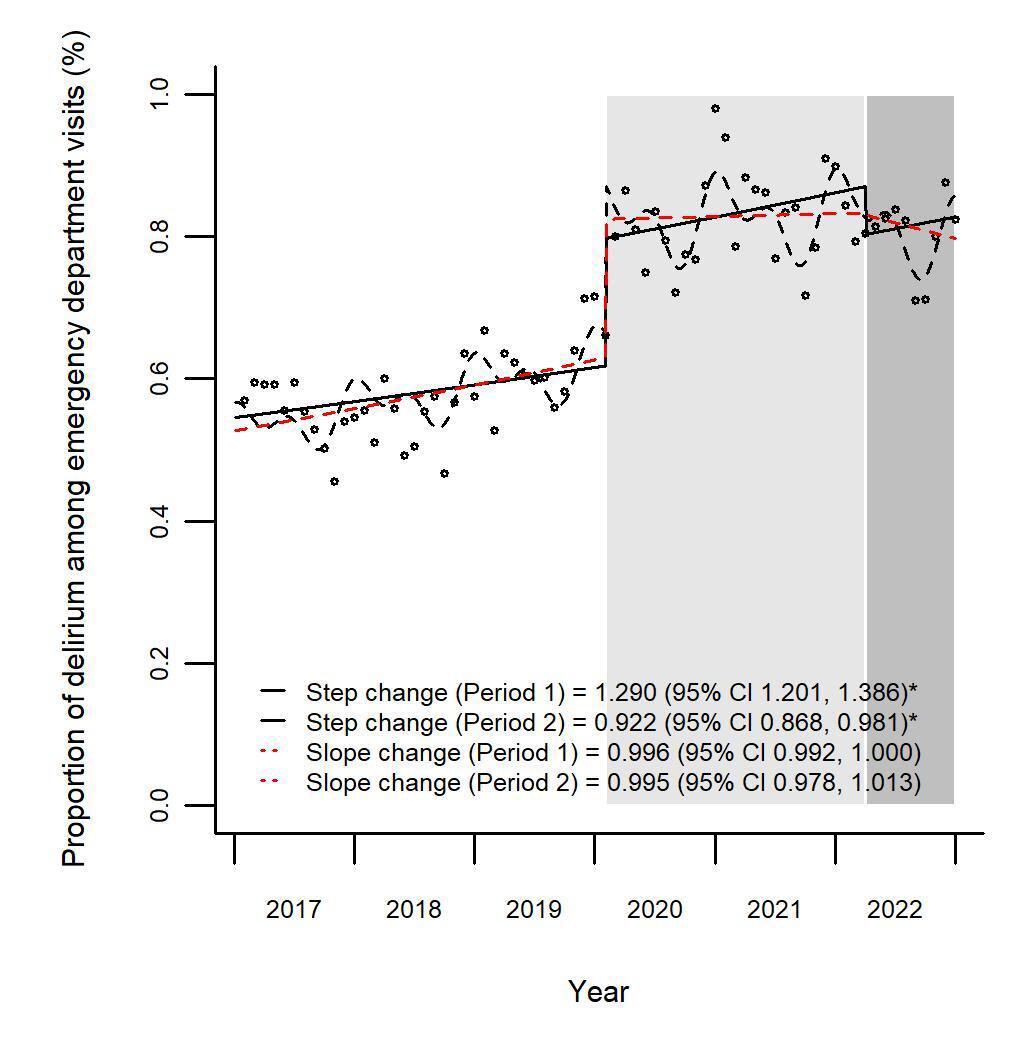

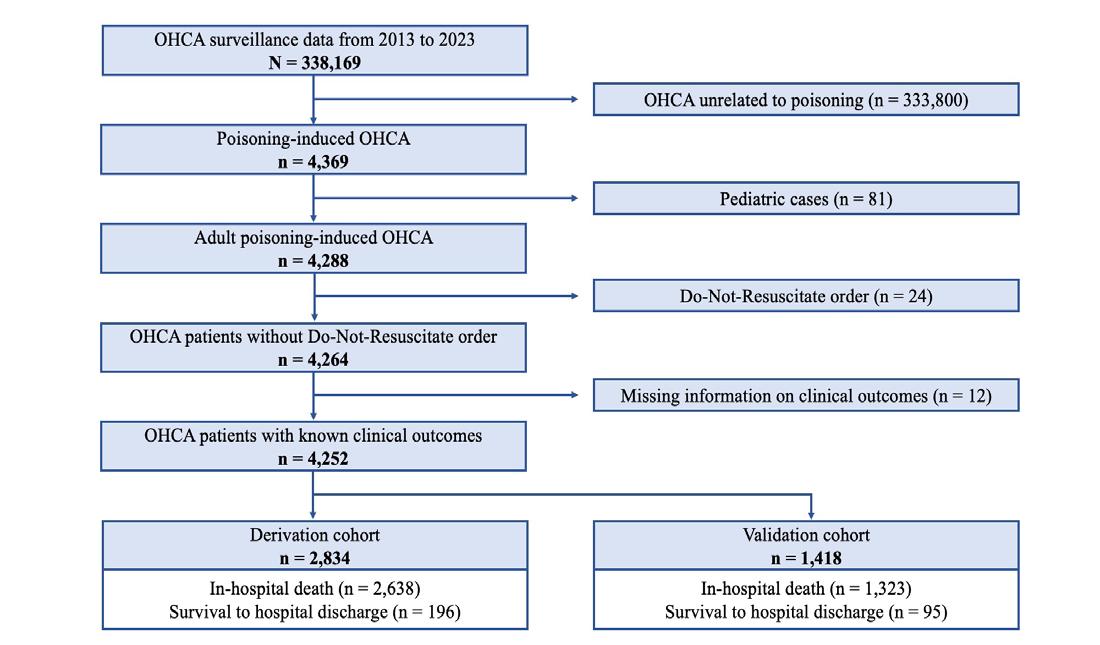

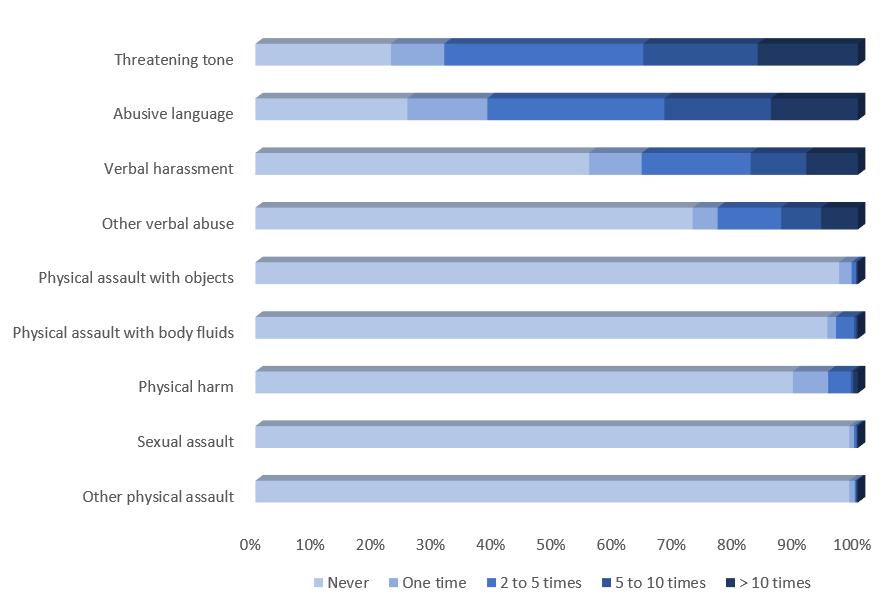

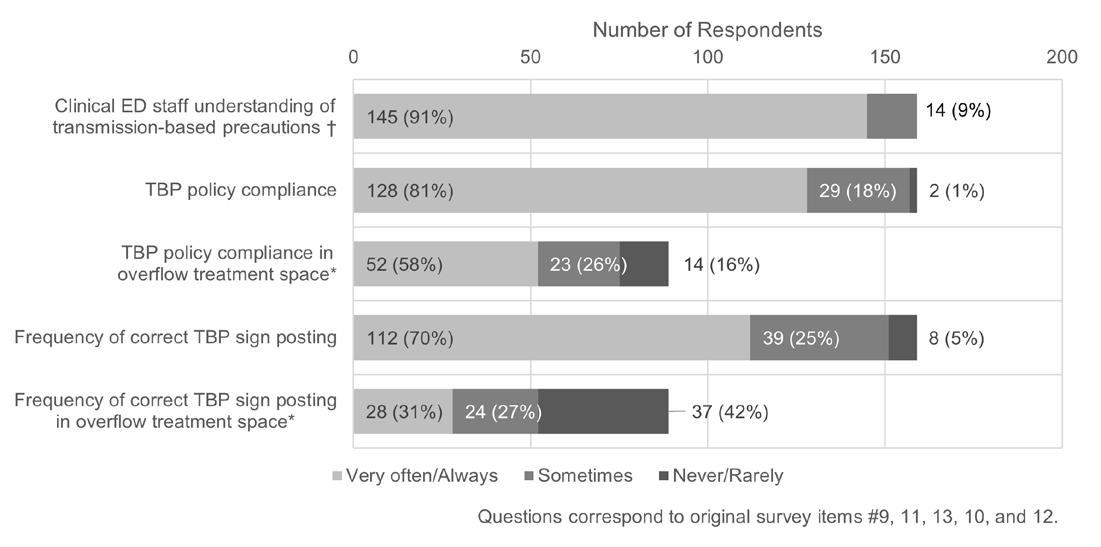

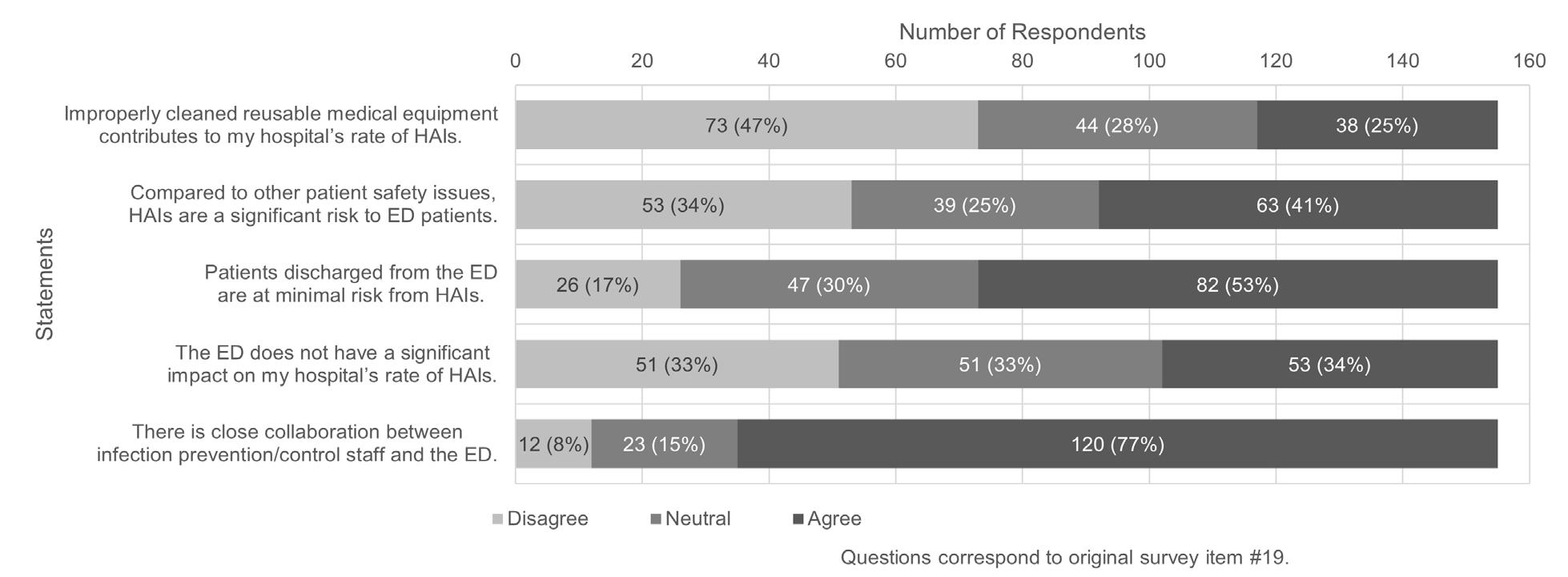

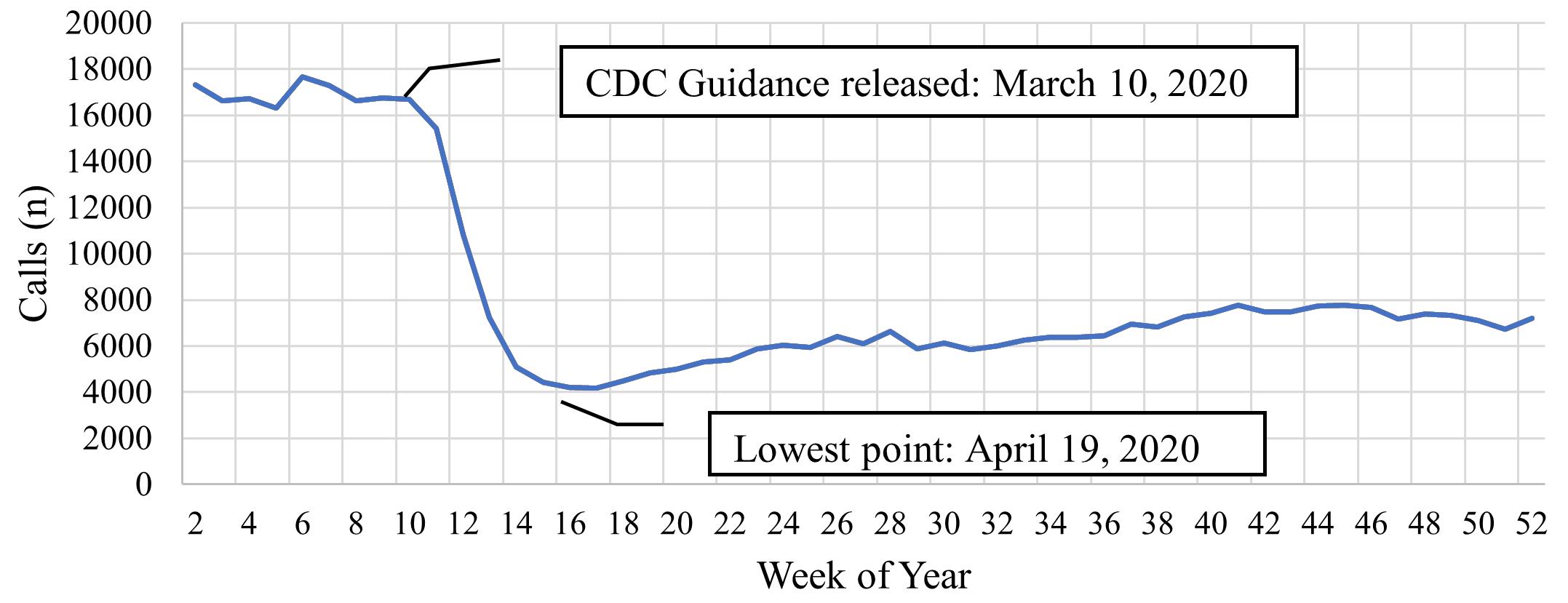

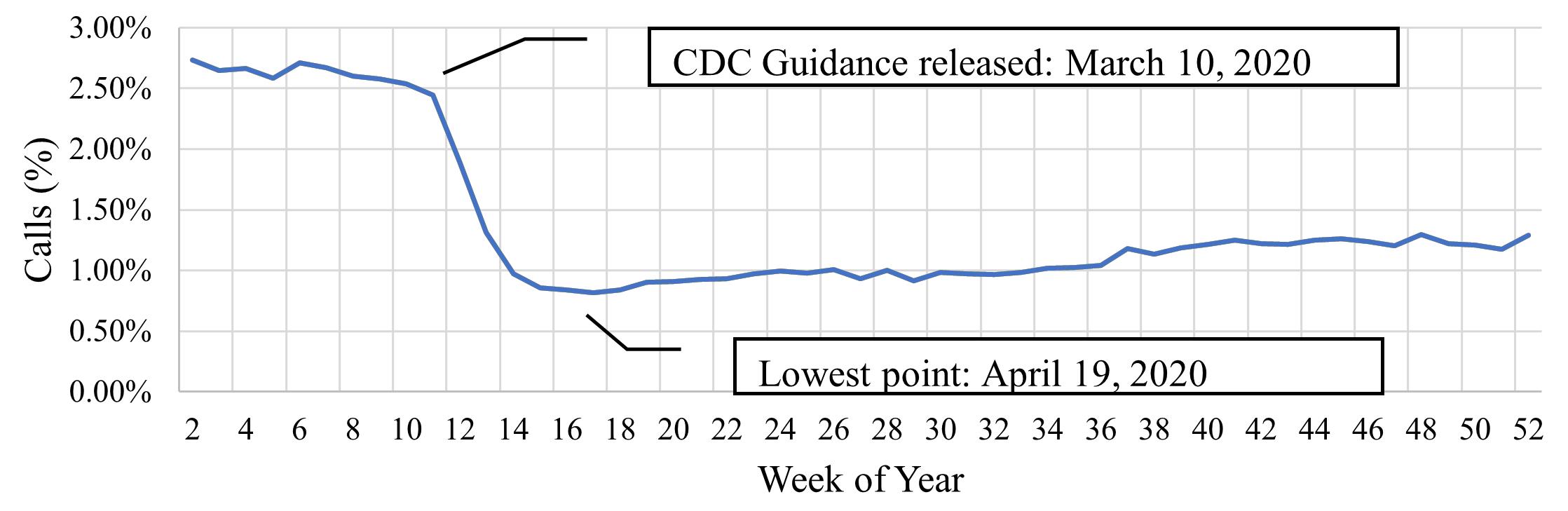

METHODS