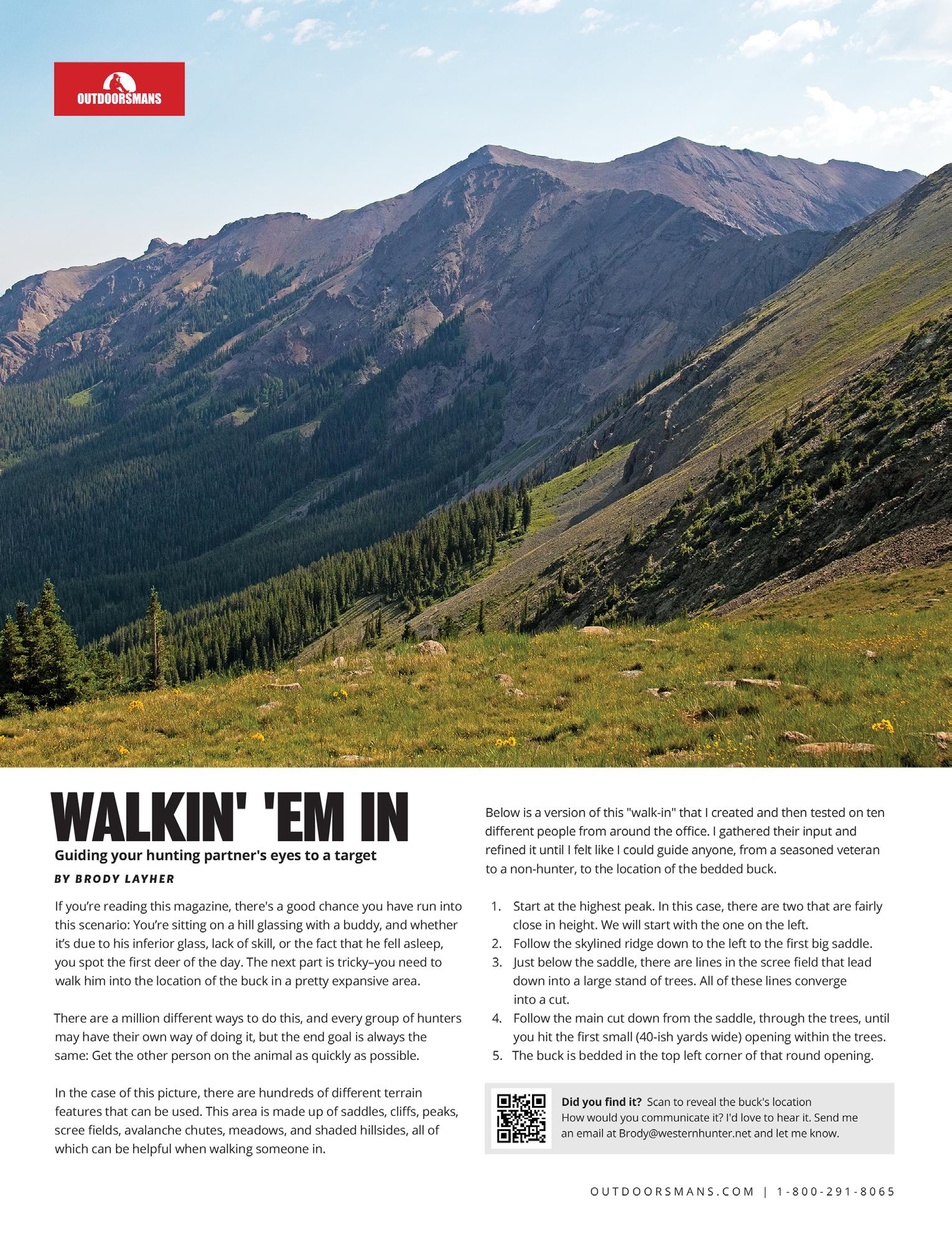

BY CHRIS DENHAM

First of all, thank you for your feedback on the previous issue, our first with the new format. As much as the team loved it before we sent it to the printer, we could never be sure what you would think. The feedback was overwhelmingly positive, in fact it was unanimously positive, not one single negative comment. That feels good, but it also makes me a little suspicious that some of you didn’t speak your mind. The only way we can improve future issues is to acknowledge our weaknesses and build back stronger, so please let us know what you didn’t like, or what you think we need to improve. Our team is strong, they can handle the truth, so don’t hesitate to let us know. Of course, feel free to give us positive feedback too. We are not bulletproof!

This is our holiday issue, and regardless of your religious beliefs, this time is always special. Families and friends gather at Thanksgiving, company Christmas parties, New Year’s celebrations, and more than a few extra days off from work. But I must say, the world doesn’t feel like a joyous place right now. Recent events, especially the fallout over the Charlie Kirk assassination, have further divided our country. Media, especially social media, continues to thrive on the idea that the entire country is filled with hate.

I have been vocal about my disdain of all current forms of media, but like a drug addict, I couldn’t help but scroll through social media the past month or so. Of course, the algorithm devil knows my right of center viewpoint from years of living in my phone, so that demon showed me post after post of young leftists denigrating, and some cases, physically assaulting someone who dared not agree with them. Does this actually happen? Yes, it does, those posts were real, they were not generated by AI (yet). It made me angry, resentful, and ready for a fight. These left-wing radicals were not born filled with hate, they have been groomed by society and trained by their media channels to believe we are all Nazi racists and need to be put in our place.

Media thrives on attention, that is its lifeblood, and its source of revenue. So, it is in their best financial interest to keep us coming back, the more we look, the more they learn, the more money they make selling our souls to advertisers. But just how prevalent are these radicals on both sides? Really... how many have you seen in person? I travel more than most and I have never been accosted for wearing hunting branded apparel or camo clothes at a gas station, fast food joints or an airport. But I have had hundreds of people ask me how my hunt was going and offering up where their brother in-law’s best friend saw some elk just last week.

Again, I know these people exist, the videos are real, but we are being gaslighted by the media into believing they are around every corner. I am not saying we do not need to be vigilant and prepared to handle a confrontation with intelligence or even with violence if provoked, but we need to fight allowing it to taint our view of the world around us.

I must confess, I am a big fan of romantic comedies, especially those with a Christmas theme. One of my wife’s and my favorites is Love Actually. The opening montage and accompanying monologue are exceptional and articulate my views better than I can. (Please imagine Hugh Grant’s British accent and inflections!)

“Whenever I get gloomy with the state of the world, I think about the arrivals gate at Heathrow Airport.

General opinion’s starting to make out that we live in a world of hatred and greed, but I don’t see that. It seems to me that love is everywhere.

Often, it’s not particularly dignified or newsworthy, but it’s always there–fathers and sons, mothers and daughters, husbands and wives, boyfriends, girlfriends, old friends.

When the planes hit the Twin Towers, as far as I know, none of the phone calls from the people on board were messages of hate or revenge–they were all messages of love.

If you look for it, I’ve got a sneaking suspicion... love actually is all around.”

I know this might be a strange intro to a hunting magazine, but life is messy. This holiday season we all have the responsibility of making our world a better place, and that starts in our own hearts, homes, workplace and community. Take the lead in taking back the joy!

Whew... I am stepping off my soapbox and encouraging you to dive into this latest issue of Western Hunter Magazine. We hope you enjoy it as much as we enjoyed creating it. WH

P.S. Die Hard is not a Christmas movie.

Courtney

Brody

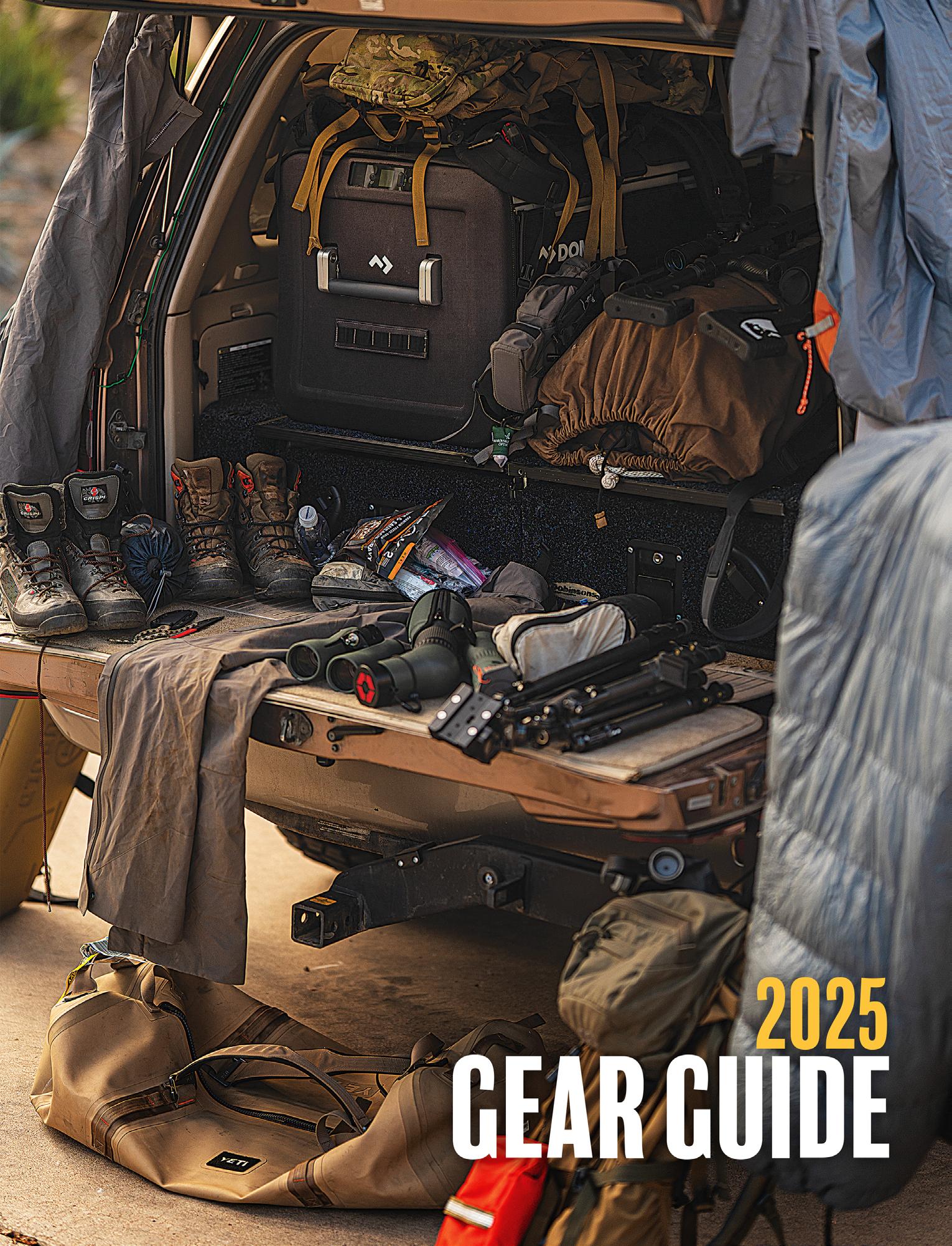

ESSENTIAL HUNTING GEAR TO HELP YOU TAG OUT THIS SEASON.

Browning redefines Total Accuracy yet again with the new X-Bolt 2 and Vari-Tech stock. This new stock design is engineered with three-way adjustment that allows you to customize the fit of the rifle to meet your specific needs, helping you achieve consistent, tack-driving performance while retaining the silhouette of a traditional rifle stock.

Internal spacers lock in length of pull. Adjustable from 13-5/8" to 14-5/8" right from the box, this system is sturdy and rattle free. LENgth of pull

Two interchangable grip modules are available for the Vari-Tech stock: The traditional Sporter profile and the Vertical profile. Both let you optimize finger-to-trigger reach and control.

Achieve consistent eye-to-scope alignment and a rock-solid cheek weld even with large objective lens optics. Six height positions offer 1" of height adjustment. COMB HEIGHT

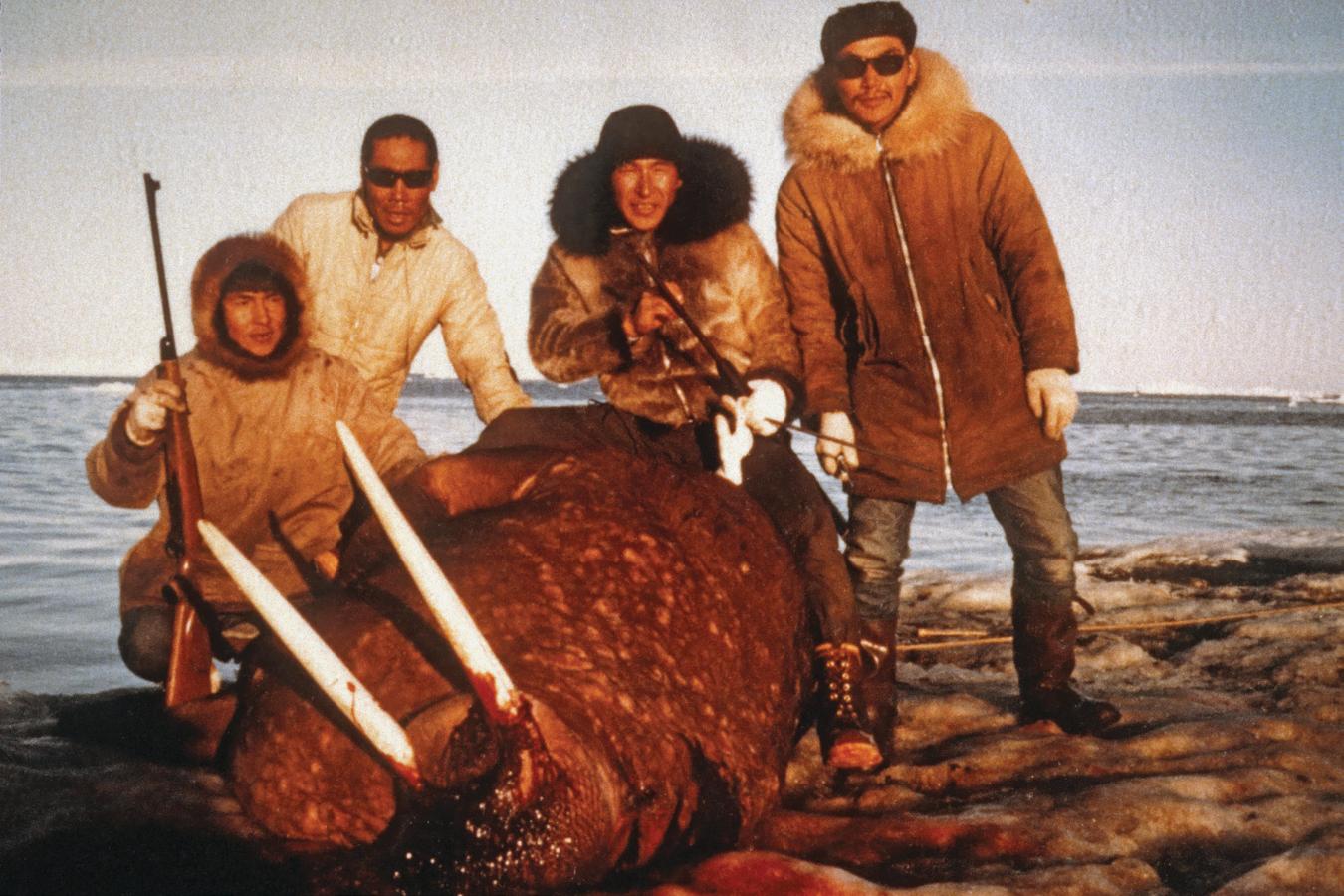

“I have always tempered my killing with respect for the game pursued. I see the animal not only as a target, but as a life granted.”

~ Fred Bear

BY JOE MANNINO

It seems that every time I need to write about my hunts, the story revolves less around the kill and more around the auxiliary aspects of hunting that keep me coming back season after season, regardless of whether I kill, miss opportunities, or get completely skunked and succeed only in taking my weapon for a walk. My 2024 Arizona late rifle bull elk hunt is no different, well, except this time we did kill–two bulls actually–but that’s not the point of this story.

Throughout the years, my uncles or my grandfather would accompany us, and that always made for a bit more of a special occasion. I remember a couple of fun years where my dad, his three brothers, my two cousins, and I made coues deer camp near the border. Nights were filled with laughter, loud voices, lots of hand gestures (Italians), and music. Those hunts when we were all together still hold a very special place in my heart, they’re core memories for sure. But they didn’t happen often enough.

As I mentioned, we’re a big, New York Italian family. My dad is one of four boys, each with a family of their own. When I was a kid in the ‘90s, life was all about family. At one point, two of my uncles lived within walking distance of our house. Most weekends, and EVERY holiday, we were all together, all 30+ of us by the time you add my grandparents, cousins, and unrelated “aunts and uncles.”

Over the years, our extended family dynamic changed quite a bit. We kids got older, went to college, moved states, and had families of our own. Sometime around the mid-2000s, we even stopped getting together for Christmas Eve. Any American Italians out there know how big that night is–seven fishes and all. Honestly, it’s the thing I miss most about growing up. My family is awesome and loud, angry at times, and fiercely loyal (you’ve seen mob movies). We say what we mean, and we mean what we say. We are equally unafraid to tell you that we love you as we are to tell you that you’re an idiot and doing whatever you’re doing wrong.

So, last year, when my dad asked if I wanted to put in for elk with my Uncle Mike and Uncle Tony (I know–I made that Robert De Niro face when I wrote that), I jumped at the opportunity. As luck would have it, our app got pulled, and four elk tags showed up in the mail.

with the sport for going on 40 years.

Uncle Mike, on the other hand, never hunted with us much–just a few trips here and there. He was absolutely stoked to go on this hunt with us and even more excited to roll up to elk camp in his 40-foot RV. No frozen tents or stiff sleeping bags this time. We had heat, real beds, and my mom and aunts would send us with homemade Italian food. You don’t hear about many elk camps where dinner revolves around baked ziti and garlic bread. Sure, we still grilled burgers and ribeyes on the Blackstone outside, but there was always pasta in the fridge, ready to reheat in the microwave, filling the RV with the smell of home. I don’t care what anybody says, that kind of comfort food hits different after a full day of hunting.

AZ elk hunts don’t come around often in general, but this one was lining up to be something special. We drew one of my favorite units in the state, the same unit in which I killed my first bull back in 2017. I was dangerously stoked since the moment our card got hit. I was determined to make this hunt special–usually a recipe for disappointment.

I didn’t spend as much time up there scouting as I had wanted to. I only made about four trips, but it was enough to check on the area where I killed years earlier and get a good bead on some country I wasn’t familiar with but super interested in. My priority was getting my dad a bull.

He last killed an elk in the ‘80s. Every hunt since, he has put me first, making sure that if we were to be successful, it would be me with the first shot. He prioritized taking me into the field over his own ambition. Somehow, I’ve always been conscious of that and extremely grateful. As I’ve gotten older, that gratitude has turned into a desire to guide him to success.

Call it ego, call it whatever you want, but he taught me those skills. I feel like the best way to say thank you for the life I’ve spent outside is to get him another bull or that wall hanger muley he’s always wanted. It’s the only sufficient way for me to say thank you, and even then, it’s not enough.

That was it, that was my motivation. Of course, I wanted to kill a bull, too. Anyone who says otherwise is blowin’ smoke. But going into that hunt, I was okay with coming home empty-handed, so long as he didn’t.

Opening day was frosty. Leftover moisture from a rainy Thanksgiving, plus a timely drop in temperatures, left the woods covered in a thin layer of ice. That type of cold always seems to increase my excitement level and, frankly, my expectations. The elk, however, did not seem to share that same excitement, and the weather only made for some nice photographs and more enjoyable nature walks.

The next few days played out pretty similarly. My old stomping grounds seemed to be devoid of elk, and I started to feel like that grass would be greener a little further north, where I had spent my summer scouting. I had planned to start to tackle that area once the weekend warriors headed back down to flat land. That plan changed once Sunday morning turned up nothing but boot tracks.

The unit we were hunting in consists of a ton of timber, very little wide open, glassable spots, and a lot of shallow canyons and draws. It’s perfect for parking the truck and still-hunting through the timber.

I spent my childhood following my dad through country like this. On this hunt, I didn’t need him to lead anymore, but I realized I still wanted him to. My dad’s getting up there in age. He’s losing a few steps and a bit of that fire that filled our living room with memories of hunts past. But there’s still a

part of him that loves cold weather, tall pines, and a chance to see the ivory tips of a big bull’s rack.

I, on the other hand, am still filled with piss and vinegar, loaded with ambition to get out there and experience all that comes with western hunting. It’s honestly quite the dichotomy between the two of us. I can’t seem to balance my ambition versus his ability and lack of ambition. But, again, this hunt was different. I made it a point to slow down, dial back my own goals, and focus on being present–with my dad, my uncles, and with the place.

One afternoon, after a long, 3-4 hour loop, we ended up back at my truck. The sun was dropping fast behind the ponderosas, shadows stretching across the dirt road. We stood there, the four of us, leaning against the tailgate, eating snacks and sipping that afternoon cup of coffee.

Then the stories started.

They weren’t hunting stories. They were stories about my grandpa, off the boat from Sicily, raising his boys in New York before moving them west. Stories about fist fights, about riding Greyhound buses cross-country from Arizona back to New York for family emergencies or weddings, about beatings that would make today’s parents call CPS in a heartbeat.

They’re proud of it. I am, too. Life isn’t always clean. People suck sometimes–even family. But using it as a crutch isn’t what we do. We don’t sit around feeling sorry for ourselves. We push through it, we laugh about it later, and we move on.

I don’t remember if we ended up actually hunting that afternoon, but I remember every laugh echoing through those pines. The late light turned everything gold, and I just stood there listening, wishing that time would slow down.

When my dad finally killed his bull, it wasn’t cinematic. We were driving out of an area when we spotted two bulls from the road. True western chaos. We scrambled out, rifles in hand, trying to make the best of a fleeting opportunity. Shots rang out across the timber as the bulls quartered away. I was focused downrange, trying to find an angle on one bull, when I heard my dad shoot again and again until the other bull lay down out of sight.

We marked the spot as dusk swallowed the last light. Driving back to camp, we retold the events of that evening over and over again and tried to make a game plan for the next morning.

Before the sun came up, we were back in that patch of timber. The first thing I did was find our spent brass, retracing our steps to where we last saw the bull. We walked slow circles in the frozen grass, scanning for blood. Eventually, we found him. Coyotes had already gotten to the bull overnight, leaving ragged marks on the hindquarters.

My dad didn’t say much. He never does about the good stuff. He’s quick to speak when something needs fixing or someone needs chewing out, but gratitude and pride come quieter for him. I get that now that I’m older.

He just looked down at his bull, set his rifle against a pine, and let out a sigh that said everything words couldn’t. When I hugged him, we both knew what it meant.

That morning taught me something about him I hadn’t fully realized before. Even after all these years, even after losing some of his passion for hunting, his instincts are still there. He knew where to stand, how to find the lane, how to put an elk on the ground. But it also taught me he doesn’t have all the answers, not about hunting, and not about life. Somehow, that made me feel closer to him.

We killed two bulls that week. Part of me felt accomplished, proud that my scouting and preparation put us in the right places at the right times. But I’d be lying if I said I didn’t feel unfinished driving home. My tag was still unfilled, and the hunt was slow. I kept thinking about the stalks that never came together, the bulls I never even saw.

Still, if I had killed, I don’t know that it would have changed much. Part of this hunt was realizing that I can’t do it my way when I’m with my dad and uncles. Sometimes it’s not about being efficient or maximizing the hunt. Sometimes it’s about just being there. Watching him notch his tag one more time.

I hope my dad remembers that part most–the laughs at the truck, the cold, quiet morning walks through the pines, the relief and pride in his eyes when we found his bull. When I think back on hunting with him as a kid, those experiences shaped who I’ve become. I don’t know what the equivalent is for a man in his late sixties. Maybe it doesn’t shape him the way it shaped me, but I hope it still leaves an impact.

Driving home, I felt accomplished, unfinished, and grateful. A few months later, I found out I’d drawn an early archery tag in that same unit for next season. Maybe it’s redemption. Maybe it’s just another chance to walk those trails again. Another chance to follow in his footsteps, even if someday it’s only in memory. WH

This season, hunters proved that tradition isn’t always about turkey and pie. Here’s a look at how fellow hunters are spending their time in the field, making gear decisions, and shaping their year.

When asked what gear they bought this year, hunters most often picked up optics (187), firearms (162), and camping gear (143), with knives (115) and packs (109) rounding out the list.

AFIELD

Western hunters make serious sacrifices for their passion, many carving out 16–20 days, nearly a hundred pushing for a month or more, and dozens logging 41+ days in the field every year.

“Once you get a tag, you hunt in whatever weather nature gives you.”

Most hunters either prefer snow (29%) or don’t care either way (32%), with fewer choosing dry ground (18%)

The vast majority (91%) don’t factor moon phases into their hunts or applications.

When asked about their primary source of gear information, hunters pointed first to in-person gear shops (120), followed closely by magazines (118) and YouTube (78).

Nearly two-thirds of hunters have skipped Thanksgiving dinner to head into the field.

// ROOM TO ROAM A tribute to wild western places.

Spanning 2.9 million acres, the Tonto National Forest is the largest in Arizona and the ninth largest in the U.S. With elevations ranging from 1,300 feet to nearly 8,000, the Tonto holds an incredible range of biomes and biodiversity. Low saguaro desert gives way to piñon-juniper country, which rises into the ponderosa pines of the Mogollon Rim. It’s home to a full slate of game; Coues deer, mule deer, javelina, elk, and desert bighorn sheep, just to name a few.

“Tonto,” in Spanish, translates to silly or foolish. Interpretations vary, but the fact that people have carved out a life in this brutal country for over a millennium proves the name fits. And speaking from experience, those of us who hunt this land are indeed chasing a fool’s errand.

It only takes one—one that does it all. The new VX-5HD Gen 2 features our Professional-Grade Optical System and delivers the repeatable accuracy and precision serious hunters demand.

INTEGRATED THROW LEVER

SPEEDSET TM ELEVATION DIAL

ILLUMINATED RETICLES WITH MOTION SENSOR TECHNOLOGY (MSTTM)

PROFESSIONAL-GRADE OPTICAL SYSTEM

This is the classiest liquid receptacle any outdoorsman can own. It’ll keep anything cold, from water to whiskey, and always make sure your coffee stays hot. I can’t say I’d take it on a backpack hunt, but I’ll never leave for a base camp hunt without at least a couple in the truck. ~ BL Yeti.com

Sick of wrestling your water bladder or cleaning it constantly? Upgrade to the Hardside Hydration Swig Rig. It has the hose function you love and Nalgene durability you need. Easy to use, easier to clean. It’s compatible with all Nalgenes. I’ve ditched the bladder and never looked back. ~ DM HardSideHydration.com

A titanium kettle is one of the most useful tools in the backcountry. You can boil water from your stove, or if you find yourself in a bind, you can stick it in the fire. The rubber grips on the foldable handles keep you from burning your paws without adding any unnecessary weight. If you’re looking for a simple solution for a backcountry cook kit, this is an item to keep in mind. ~ BL CascadeDesigns.com

This is hands-down one of the most luxurious sleep systems I’ve ever drifted off in. The Baja Bundle pairs a Therm-a-Rest MondoKing Sleeping Pad with a rugged bed shell, cozy Baja Quilt, and soft bamboo sheet set. The system is capable of handling summer days and winter nights depending on the layers you bring along. It’s your ticket to the most comfortable night’s sleep in the million-star motel. ~ DM BornOutdoor.com

This handy apparatus has been the source of the most “what the heck is that?” I’ve gotten for the past year. It looks a little odd and weighs a little more than your average pad, but it can turn a guy with a bad back into an all-day glassing machine. The chair allows you to lean back rather than having to hunch forward all day. It has not only enhanced my glassing ability, but it also lets me enjoy a glass of whiskey in the evening without having to find a stump to lean against. ~ BL CrazyCreek.com

Overbuilt is not an over-statement when it comes to the Gridiron Gameday from Camp Chef. This Hoss has a large enough cooking surface to feed you, your family, and the families in the two campsites next to yours. This thing is extremely versatile, and portable enough to earn a permanent spot in any serious camping kit. ~ JM CampChef.com

This is the future. The first time I fired up my CFX3 (previous version), the temperature in the back of my Land Cruiser was around 110 degrees, and it dropped to 35 degrees in about an hour. The voltage requirement is extremely low, and this unit is so smart that it will never overdraw your regular car battery. It hardly runs once it’s cold. The DZ stands for dual zone, so you can run it fridge/freezer with everything controlled and monitored via an app and Bluetooth. Assuming it lasts a few years, the cost isn’t a whole lot greater than a regular cooler plus ice. ~ LS Dometic.com

Headlamps are one of those pieces of gear I never put much thought into. That is, until I was deep in a wash in bear country with a dim bulb and dying batteries. I realized I needed to up my game. The Strike 1800 headlamp from Last Light is built for hunters and outdoorsmen who need reliable brightness in all conditions. With a powerful 1,800 lumen output, it provides unmatched visibility whether you’re on the trail, in camp, or tracking game after dark. Its lightweight design and rechargeable battery were two must haves for me. Pro tip: Get it as part of the Back Country Bundle they currently offer. You will get a great solar charger and LED light rope that are just as useful as the headlamp. ~ RB LastLightllc .com

I’ve always thought that to beat the Leupold VX-5 as a hunting scope would be very difficult... or very expensive. It’s lightweight, tough, and the glass is great. It’s got a redesigned turret with more travel, some ergonomic improvements like a handy-dandy throw lever, and the same SpeedSet system that was launched with the new VX-6HD. For me, this combination of small improvements takes the VX-5HD from the “most functional” category to the “best” category. It’s a lot like the original, but more so. ~ LS Outdoorsmans.com

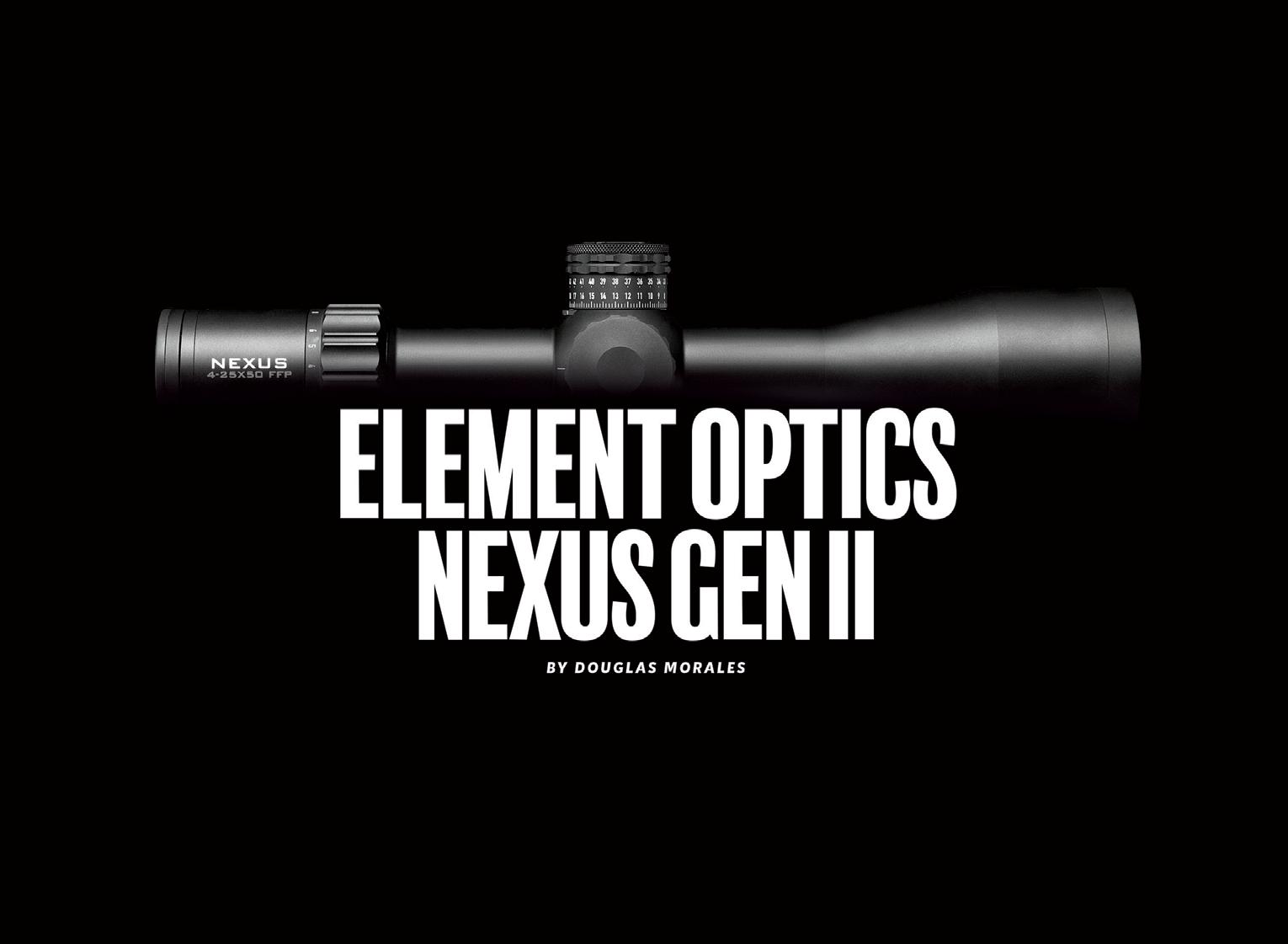

If you recently got a new hunting rifle to add to your collection (that your wife may or may not know about), then it’s time to get it dialed in and ready to put to good use. A quality riflescope that you can depend on is always a necessity, and there are a ton of choices in the riflescope optic world. In my opinion, one of the most bang for your buck options is the HELIX Gen 2 6-24x50 FFP by Element Optics. A First Focal Plane riflescope with reliable tracking, a tool-free turret system with a zero-stop, a 30mm tube, good reticle choices, and a lifetime warranty at this price point is undoubtedly a big time value. If you can afford a few tiers above this price point, Element Optics has some real heavy hitters in their NEXUS and THEOS lines that you’ll definitely want to check out. ~ PP Element-Optics.com

The SFL 10x40 is the best binocular that I’ve seen under that $2000 mark. I’ve had these out in the field and was hard pressed to find many differences in quality between them and a pair of Swarovski ELs. The best I could come up with is that the ELs gave me a little more finite detail, but not by much, not enough to justify a $200 price difference. Plus they’re smaller, and lighter. ~ JM Outdoorsmans.com

If you’re looking to enter the rangefinding binocular lifestyle, the Vortex Ranger HD 3000 is absolutely a great starting point. For $800–the price of many decent binoculars without rangefinders–you’ll have a tool to use for many seasons and maybe even pass down when you’re ready to step into something a little more feature-rich. ~ JM VortexOptics.com

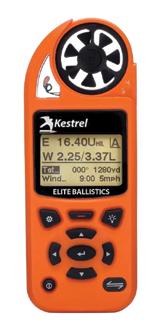

In a world where any Tom, Dick, and Harry can run out to the range and ring a 1000-yard gong with just about any off-the-shelf rifle, you should have a ballistic calculator that allows you to be as accurate as possible. The 5700 Elite is still the gold standard and won’t be dethroned anytime soon. ~ BL KestrelInstruments.com

Our team shot thousands of rounds of Hornady’s ELD-M cartridge this year, training for and competing in NRL Hunter matches. The consistency in speeds, accuracy, and reliability in a number of different conditions made this feel like one of the few easy buttons for shooting matches. If you aren’t handloading, or even if you are and aren’t very good at it, you should be shooting Hornady’s ELD-M cartridge. Plain and simple. ~ KG

MidwayUSA.com

The American-made bipod is a favorite among our crew. Its aluminum and stainless steel body holds up to any environments you’re willing to put your rifle through. It’s fast, stable, and easy to use once you’ve ran a few dry runs. The three sections and adjustable angles let you comfortably shoot prone, sitting and even kneeling in most cases. ~ DM Outdoorsmans.com

Scope rings might seem like something you can pick up at any old sporting goods store, and as long as they fit, they’ll be fine. Well, that couldn’t be further from the truth. Rings provide the foundation for your rifle holding zero. If your rings fail, your whole rifle system fails. These rings from Unknown were purpose-built to never let that happen. ~ BL UnknownMunitions.com

There is no greater balance between a highly protective hard case and an ultra-portable soft case than the Leupold Rendezvous Bow Case. I’ve never felt short on storage space with this thing either–there’s perfectly sized compartments for storing everything from stabilizers, releases, tools, you name it. With 900D water repellent nylon, beefy zippers, and reinforced padding, your bow is safe from just about any reasonable threat in its way. Except for a grizzly bear. A grizzly bear would still jack this thing up. ~ KG Leupold.com

Nearly every hunting apparel company has jumped on the “active insulation” train, but other companies (Outdoor Vitals in this case) have been perfecting them for years. This 7oz mid layer keeps you at a perfect temperature, no matter if it’s 40 and raining or 70 and sunny. This simple piece is well worth having in your closet. ~ BL OutdoorVitals.com

This hoody checks all the boxes for me–ideal weight for all day wear, loose and comfortable but not baggy and boxy, durable quality, and American-made with Montana raised wool. This piece gets worn in the truck, on the stalk, and in camp around the fire. It’s a great option for a cold night in the sleeping bag as well. ~ KG DuckWorthCo.com

Out of all the adjectives and keywords I can use to describe this base layer, essential is the most appropriate. I do not know what kind of sorcery First Lite used in producing the Yuma, but it is the most capable article of clothing I own. From keeping the summer sun off me during my kid’s soccer games to being my next-to-skin layer during late season hunts, the Yuma can do it all. ~ JM FirstLite.com

I’ve been highly impressed with the quality of this merino wool/polyester blend. Every stitch is sourced and sewn right here in the USA and delivers with the breathability, soft feel, and comfort you need to spend multiple days in this piece. You may stink after day 5 in this hoody, but it won’t be because of its performance. You’re probably just a stinky dude. ~ KG DuckWorthCo.com

I’ve worn many Kuiu base and mid layers over the years, and without question, the UM 120 LS Hoodie is my favorite and a non-negotiable piece for any warm or mid season hunts. Earlier this Summer I wore this piece at a two days NRL Hunter match in New Mexico, with temps in the high 90s. I stayed surprisingly cool and comfortable the whole match, especially when throwing the hoodie up was the only shade I could find. After taking my pack on and off a lot that weekend, I noticed some decent pilling of the wool around the mid section which was purely aesthetic and didn’t appear to weaken the fabric at all. ~ KG Kuiu.com

Easy, warm, and comfortable. These make a huge difference when it is extremely cold and windy. I really liked the clam-digger cut that falls just over the top of my boots, although it felt a little funny to begin with. Being able to zip them on and off is a godsend, but it backfired on me last year. If anyone finds a pair of these on a peak in the Matzatzals, they used to be mine. ~ LS SitkaGear.com

This year marks my fifth season in these boots. Over the last five years, they’ve seen just about everything Arizona can throw at a pair of boots; triple-digit desert heat, sub-freezing mornings on the Rim, and every kind of dirt, rock, and cactus in between. One of my favorite features is how reliably they keep my feet dry, whether I’m crossing ankle-deep creeks or chasing deer and javelina during those rare low-elevation snow dumps. I probably shouldn’t admit this, but I’ve never sent them back for a resole, and I’ve only waxed them once. I should take better care of my boots. But that just shows how tough these things are. If they can handle Arizona, and a hunting dad who barely thinks about boot care, they can handle anything. ~ JM Kenetrek.com

My least favorite backcountry nightmare scenario is being bitten by a rattler in the middle of a hunt. These gaiters give me the protection and peace of mind that I need without costing an arm and a leg in more ways than one. They’re also pretty dang light and breathable, so there’s no reason to not strap them on for those hot early season hunts. ~ TH QogirGear.com

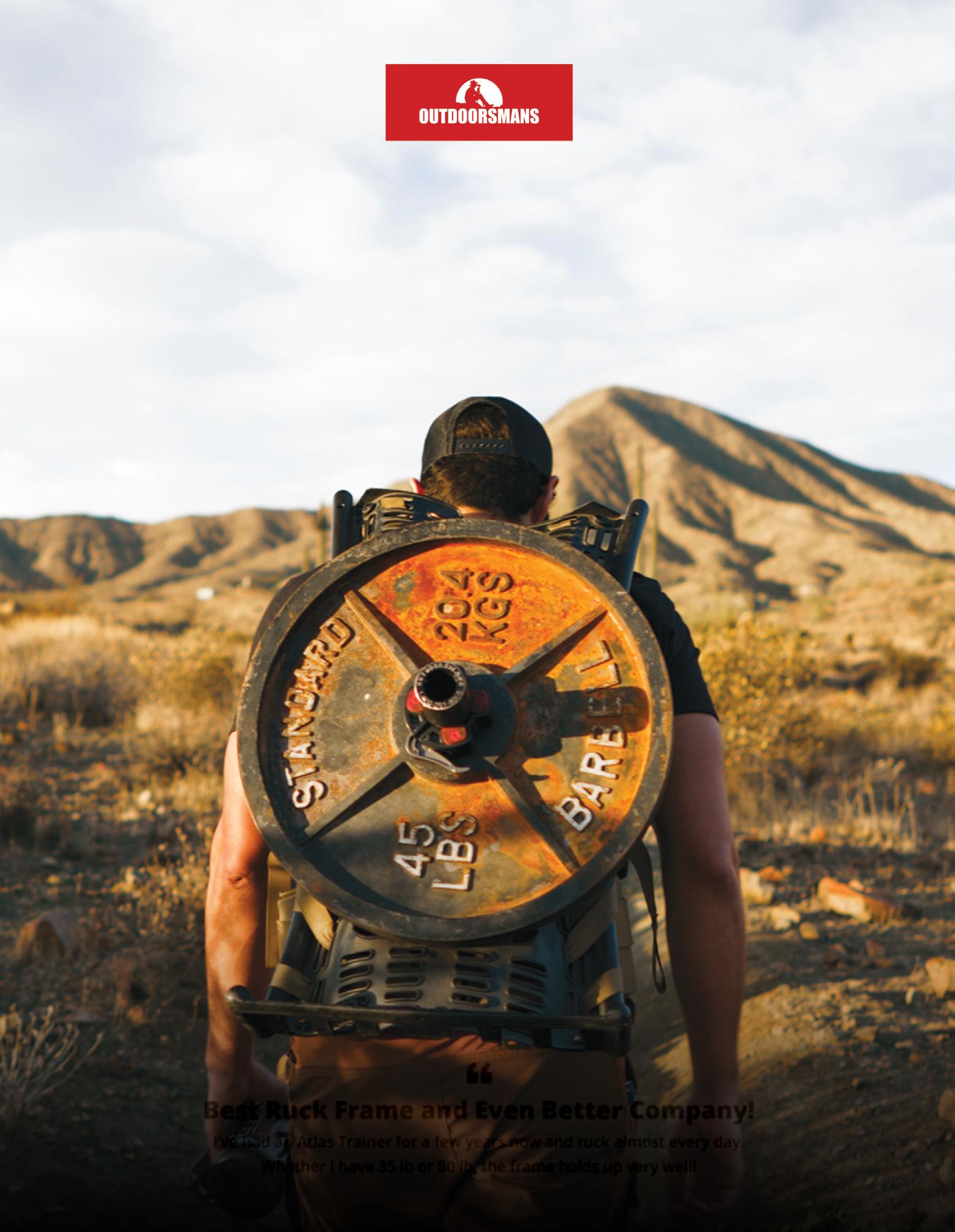

The new Eberlestock Modframe is a major leap forward in both comfort and versatility. Fully compatible with the entire EMOD system, swapping from my Brooks 3500 to my old Batwing and Scabbard set up was seamless and took me less than a minute. The totally revamped suspension system features larger padding and an integrated load panel that handles heavy meat hauls with ease, while the redesigned load lifters shift weight off your shoulders and onto your hips for unmatched comfort and stability. Built with Eberlestock’s signature durability, the Modframe is ready for years of abuse–and when it’s time for a mid-day glassing nap, the lumbar pad doubles as one of the best camp pillows you’ll ever find. ~ JA Eberlestock.com

Handing the meat off for someone else to grind and wrap was starting to feel... off. Like stopping an inch short of the finish line. Last year, I changed that. Picked up a MEAT! grinder and chamber vac, and took the last piece of the process back into my own hands. Now I can make what I want: burger, bulk sausage, links, whatever flavor, whatever batch size. It’s cleaner, more personal, and way more satisfying. If you care as much about what hits your plate as what hits the dirt, I’d recommend MEAT! processing gear. Worth every penny. ~ BB MeatYourMaker.com

The updated Batwing V2 quickly became my favorite pack setup due to its minimalist style while adding meaningful improvements like internal pockets and an exterior zippered pouch for better organization. When paired with the EMOD lid, this slim and lightweight pack system is built to go in light and come out heavy. ~ JA Eberlestock.com

I’ve gone through so many SD cards in the last 15 years that I have become an expert at recovering data. A few years ago, my A7RIII came with one of these TOUGH cards, and since then, I’ve added more and more of them. I refuse to use anything else. They come in all flavors and sizes, and they lack the little pins that are always the source of breakage. Filming one episode of The Western Hunter is plenty to kill a card, let alone a dozen, and I’ve yet to have one of these die on me. ~ LS Electronics.Sony.com

The MKC Stoned Goat strikes a perfect balance of size, weight, and blade profile, making it an ideal hunting knife. The blade profile makes precise work easier, especially when trying to avoid accidental hide punctures. I used it on a deer and then shortly after on a bear, and it made quick work of both without a single touch-up. Even after two full field dressings, it was still sharp enough to shave hair from my arm. ~ JA MontanaKnifeCompany.com

I’ve been shooting the heavy and very stiff HD 275 arrow from Day Six for the past six months and have been impressed with the out of the box consistency they arrived with. They showed up fletched with vanes and an insert/outsert system already installed to my specifications. The durability of these arrows is great and the build of the EVO broadhead is impressive as well–definitely has meat and bone as a focus, not just foam. ~ KG DaySixGear.com

After a decade of use, I finally said sayonara to my old Leki Legacy’s and hello to these new Makalus. They’re a handful of ounces lighter because of the carbon and the lack of a second locking clamp, while also feeling more rigid. They break down into a smaller package and have a far more comfortable grip on them. I can already see these surpassing the scratch count that the old Legacy’s have. ~ BL LekiUSA.com

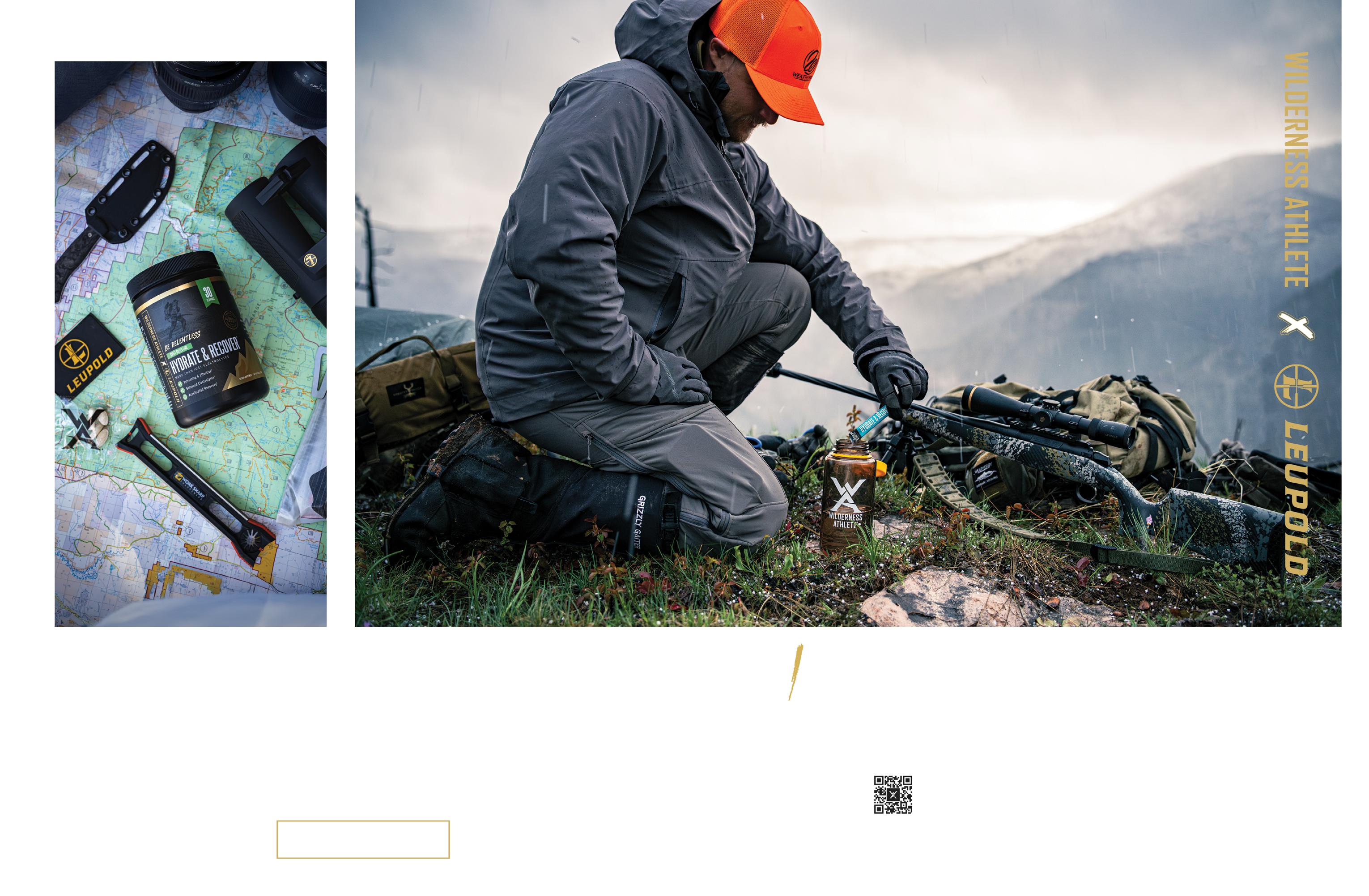

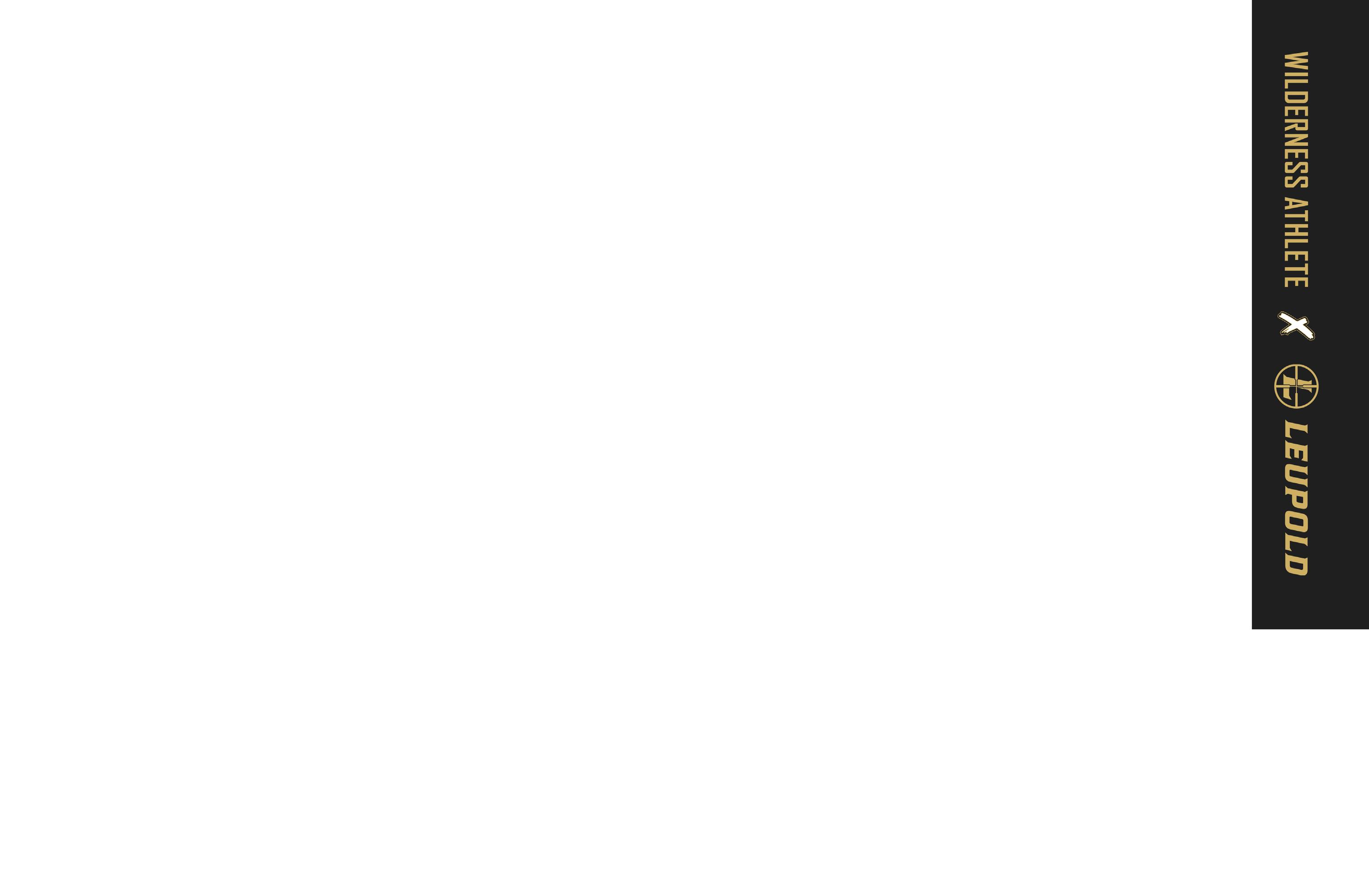

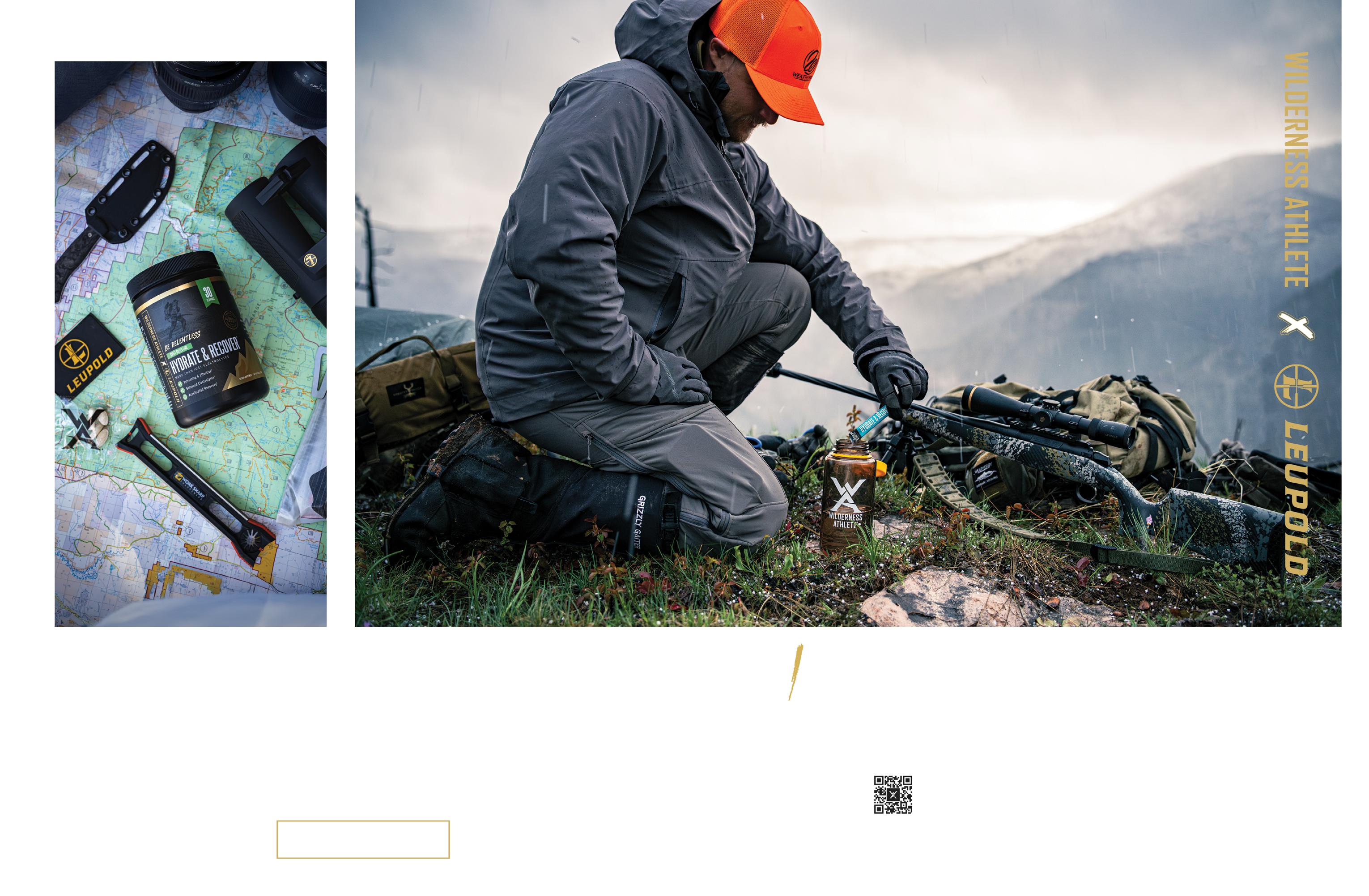

The Leupold Relentless series by Wilderness Athlete packs all the staples I’ve relied on for years–now in bold new flavors that hit the spot. This season they’ve fueled my elk hunt prep and earned a permanent spot in my pantry. Sweet Salted Lime Hydrate & Recover is my non-negotiable for training in the heat, while Strawberry Lemonade Energy & Focus gives me the guts to train in that heat. On heavy strength days, Brute Force Blue Raspberry brings the pump and intensity, and The Good Stuff (Multi-Vitamins, Omega-3s, and Probiotics) keeps my foundation solid so I’m ready seven days a week. This stack was built for the relentless hunter–ready 365 ~ KG WildernessAthlete.com

Created by an avid DIY bowhunter, each book is more than just a collection of successful, 100% fair chase, elk hunts. They explore the vital role that hunters play as stewards of conservation and the many life lessons learned through hunting. These coffee table books are great for seasoned elk hunters and newcomers interested in learning more about bowhunting elk. As a bonus, 30% of all profits are donated to organizations proven to deliver quality elk management and habitat improvement. ~ RS ElkBowhunting.com

From the moment I saw another dad walking around a crowded farmers’ market with his kid perched securely in a backpack, I needed to ditch the stroller and get one for my family. I chose Deuter because I’ve loved the day pack I’ve owned for years from their brand–and the features and materials on the Kid Comfort carrier were noticeably nicer than those of others I tried on. I’ve been on countless hikes and strolls through the farmers market with both kids enjoying the ride from this pack, and equally important, being comfortable myself too. ~ KG Deuter.com

The Osprey Poco LT has been a total lifesaver for getting out and exploring with my one and three-year-olds. It’s light enough that I don’t feel like I’m carrying a small boulder, but sturdy enough to handle all the bumps and twists on the trail. The kids ride in comfort, and I stay comfortable, too. The whole thing folds down small enough to toss in the car for spontaneous adventures. Not to mention it has an awesome storage compartment for the most important gear you’ll take with you–the snacks. It’s made for parents who refuse to sit still, and can (almost) guarantee nap time success. ~ KO Osprey.com

This foldable toilet seat is a total lifesaver for camping and road trips, especially if you’ve got kids! It’s super easy to set up, packs down small, and makes bathroom breaks way less stressful. It’s great for kids but sturdy enough for adults, too, which is awesome for those late-night campsite runs. Just make sure you get one without crossbars on the bottom (trust me, you’ll thank yourself) and if you can, grab one with a toilet paper holder–it’s such a nice bonus. Honestly, it’s one of those things you don’t realize you need until you have it, and now I never leave for a trip without it! ~ RB BlikaHome.com

I picked this tripod up for my boy when he tags along on hunts. The size, weight, and price caught my eye, and it hasn’t disappointed. It’s light enough for him to carry, and I don’t mind when it inevitably ends up in my pack because he’s got too many rocks in his. It deploys fast, stays steady, and doesn’t get in the way. The stock head’s kind of meh, but slap an Outdoorsmans Pistol Grip on there and you’ve got yourself a fine glassing system. ~ JM Outdoorsmans.com

I know a fella who siphoned a hundred bucks from every paycheck for years to make sure his wife didn’t find out how much he spent on his binoculars, only to one day hand them to their kids, who inevitably destroyed them while trying to look at a cow elk in Yellowstone Park. Get these Bantam binoculars for your kids instead. Worst case scenario, you’re out an hour or two’s wages. ~ BL VortexOptics.com

I went against the grain and picked up some legit technical gear for the kid. Sure, he’ll outgrow it fast, but it’ll get passed down, and the real win is how much more comfortable (and excited) he is out there with me. Managing a 50-pound nine-year-old’s body temp is no joke. I’m sweating, he’s freezing. KUIU cuts the guesswork and a few layers out of the mix. Bonus: he’s stoked to look the part... though I’ll miss that Pikachu hoodie bouncing down the trail. ~ JM Kuiu.com

In an ever-evolving world of digital media consumption, screen time, and AI creation, as parents, we need to be extra mindful of what is presented to our children and what kind of real experiences we want them to learn from. There is no substitute for being outdoors and learning the skills that are needed to provide for your family. As a father of a three-year-old son, I am so excited to read this to him every night and emphasize the importance of fresh air, feet in the grass, and meat on our tables. Author Tana Grenda has perfectly captured this sentiment in her children’s book, Stuck In the Rut: Chasing Dreams

This is a story of her own family’s passion and perseverance for hunting. Whether it’s through rushing streams or breathtaking landscapes, it encourages young hunters to follow their dreams and embrace the thrill of the hunt. If you’re a parent or know someone who is, I highly recommend getting this book as a gift this holiday season! ~ PP Amazon.com

THIS LIST WAS CURATED BY THE FOLLOWING WESTERN HUNTER STAFF:

BB – Ben Britton

BL – Brody Layher

DM – Douglas Morales

JA – Josh Adderson

JM – Joe Mannino

KG – Kevin Guillen

KO – Katelyn O'Brien

LS – Levi Sopeland

PP – Pedram Parvin

RB – Ryan Berg

RS – Randy Stalcup

TH – Tom Hinski

BY LEVI SOPELAND

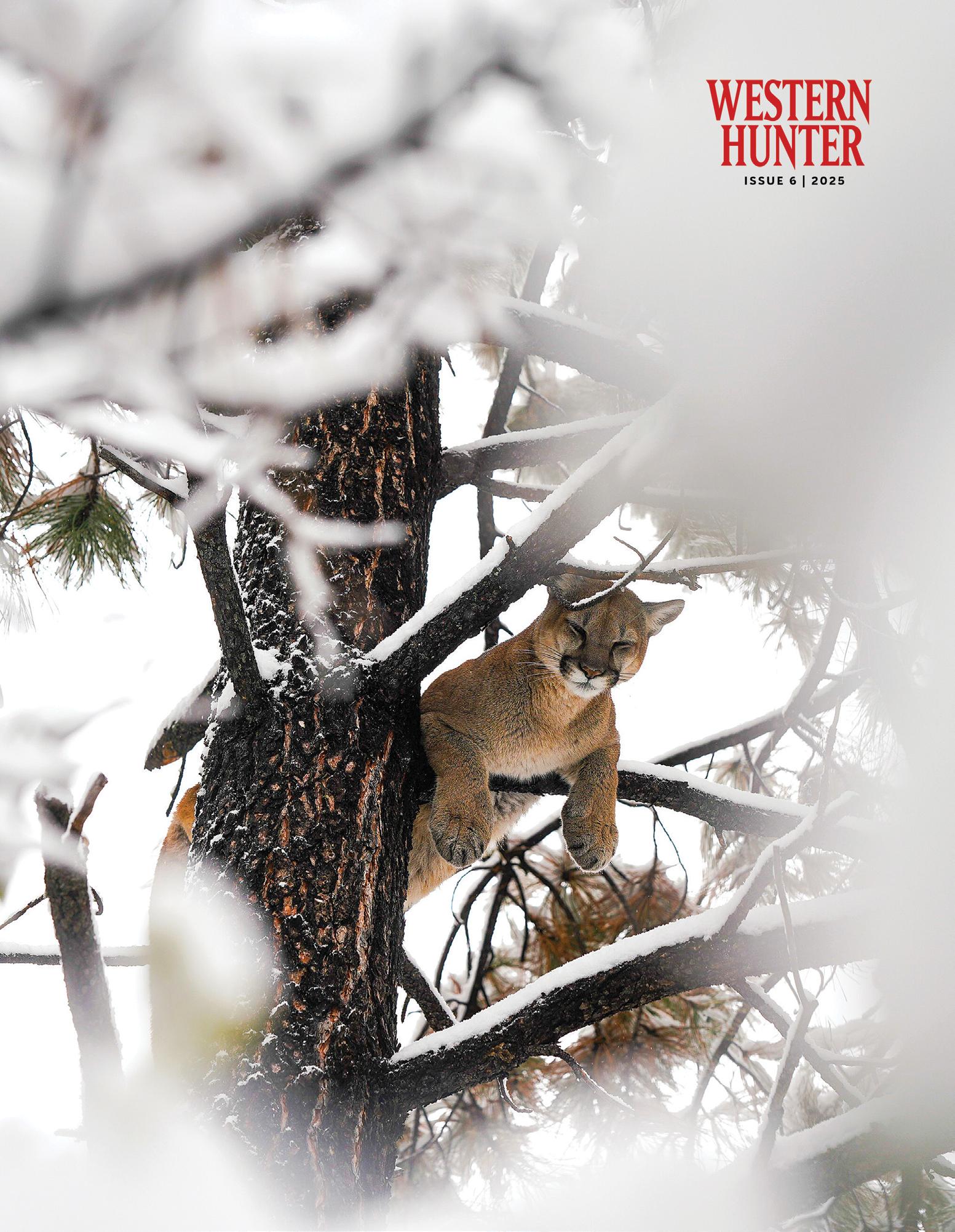

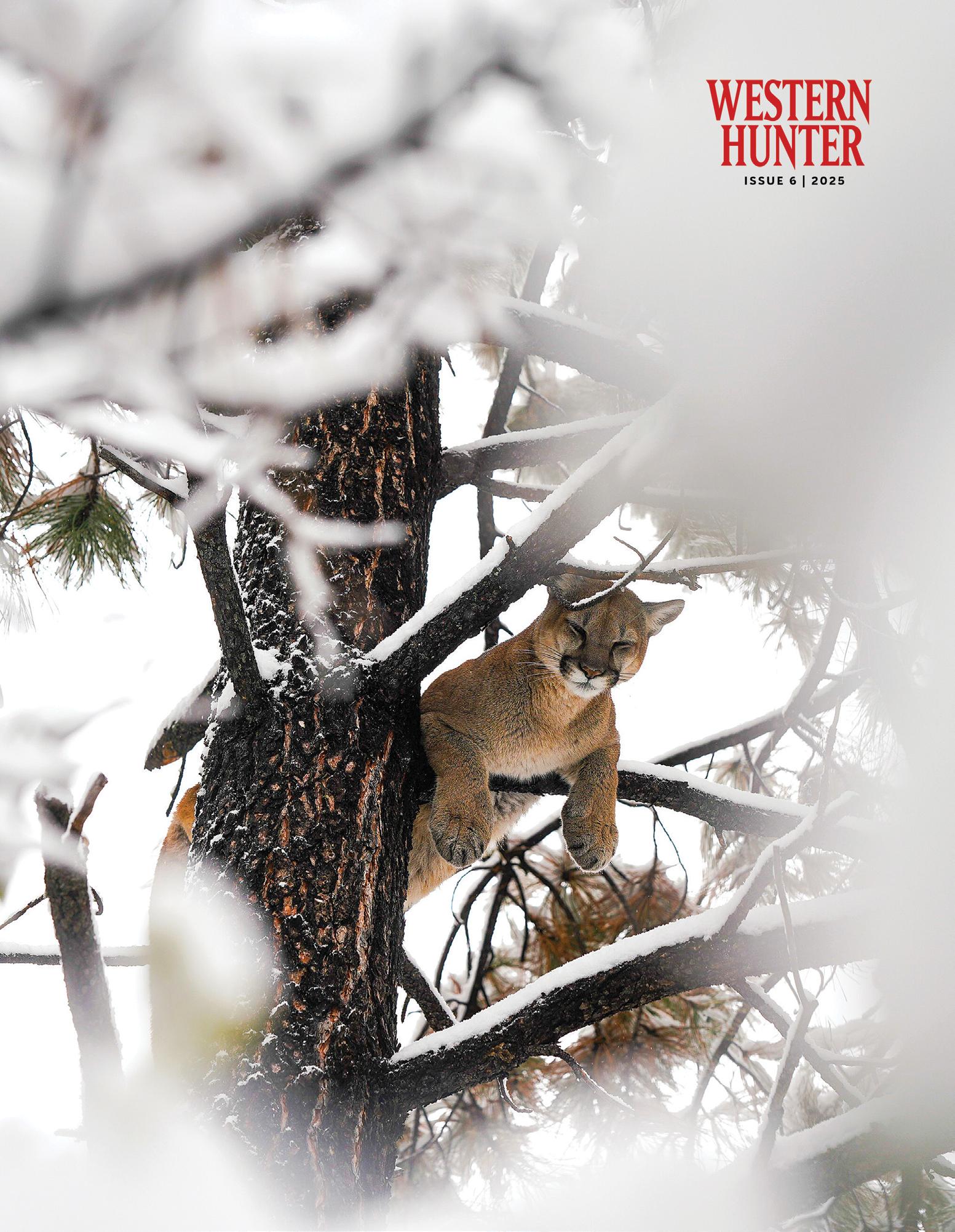

Kevin and I were on call for a few weeks, waiting for the starting gun for the race up to the Fort Apache Reservation in the White Mountains.

There, we would meet up with Floyd Green and Larry Johnson. Floyd, the owner of Outdoorsmans, has a predator outfitting business on the Reservation via a concession with tribal Game and Fish. Larry is a USDA problem animal removal specialist and a classically trained houndsman in his own right, and together, these two have more hound hunting experience than just about any pair alive.

The plan was to chase some lion tracks and accomplish either of two goals: If we caught a young cat, we would tranquilize, collar, and release it, as the Apache tribe was interested in studying the population in this area for the first time. If we caught an old cat, Kevin would punch his ticket.

The call finally came, and at midnight on a Tuesday in January, we rolled out of Fountain Hills in Kevin’s perfectly souped-up Lexus GX470. Plenty of windshield time and caffeine had the anticipation building like stage one of a self-landing rocket launch.

We arrived at our meeting point in Whiteriver a little after 3:00 AM and took off into the darkness on a dirt road with about six inches of snow cover. Floyd went in the other direction with his wife, Julie. Larry jumped in with us, and we split up and cruised along with flashlights out the open windows. I was mostly pretending to be looking for tracks, as I was too busy watching the 6'5" bear of a man work. I thought there was no real way we could find a track in the dark from a moving vehicle, but to Larry, it was only a matter of time.

Floyd ended up catching a track up the mountain a few miles, so we fishtailed our way up a virgin snowcovered two-track through the pines and around bends with biblical sunrise vistas. His dogs were sent to find the target and get it bayed up. After about 45 minutes, all of the dog symbols on the Garmin were vertical, and the bay meter was off the charts.

At the base of that tree, Larry came to us with another problem. And a net. Larry is not the type of guy you argue with much, so when he told us that we would hold the net and catch the pissed-off lion when she jumped out of the tree, we nodded silently and assumed the position.

After a few minor miscalculations with the air pressure in the dart pistol, we had a mountain lion in a tree with a dart in her butt. She was clearly affected, but by no means “sleepy.” Another few snowballs sent her down the tree and off across the hillside. The dogs and Floyd took off after her while we gathered up all the gear. We soon followed and were led to the cat by the baying of the loose dogs.

“She snapped and swatted her unsheathed claws, but I was able to dodge them. I find myself almost wishing I had a scar to remember her by.”

We ran down into the canyon in the snow to find six dogs frantically jumping at a particularly large ponderosa, scratching the bark from the bottom of it with a wildness in their eyes that is unique to lion and bear hounds. After we had tied them off, called them good dogs 20 times each, and become accustomed to the non-stop baying, Kevin and I took a look up at the first live, wild mountain lion either of us had seen.

We determined that she was a young-ish female and would be the perfect subject to accomplish goal number one. So, without much fuss, Floyd sat down and started mixing up the tranquilizer cocktail and priming the dart gun. It was as precise as snowy mountainside science gets. “Was it 100 ml

We arrived at the scene to find Floyd holding three spastic dogs by their collars, about 30 feet uphill of what I can only describe as a drunk mountain lion. She was attempting to stand and was mostly unable. Although her swiping and biting muscles were still relatively functional. The censored version of what I was thinking is, “What on earth do we do now?”

Larry, a man of action, quickly came to us with a plan. I can’t recall his exact words, but they were something to the effect of, “Levi, we need to get that cat up to this flat spot where we can work on her. Drag her up here.” My only issue with his order was that, in my opinion, she did not appear to have been rendered safe.

Once again, Larry is not the type to argue with, so I made my way over to her, grabbed her behind the jowls (per Larry’s instructions), and dragged her about 20 feet up the hill. I will never forget the feeling of the muscles of

“I can’t believe you did that.” In hindsight, I think maybe he could believe it, but we laughed so hard that I almost defrosted my pants.

With a little more cowboy doctoring, we got her settled down and collared. We then built a barrier between her and the creek in case she awoke and took off running into it. The tempera ture was in the single digits, and the semi-frozen river might not have spat her back out if she did.

That night, we celebrated a hilariously fun day back at Floyd’s house and went to sleep, dreaming of another day like that.

Again, we left around 2:30 AM and made our way out to another area of the Reservation. Same game plan, same teams. Larry, Kevin, and I had two of Larry’s dogs in the trunk, and Floyd’s team was a few miles down a different road. We were driving along with flashlights again for an hour or so, and I was getting dawn-sleepy when Larry firmly said something like, “KEVIN. STOP.”

We got out and inspected the freshly-snowed road. Larry had spotted another track, and it was exactly what we were hoping for. A four-inchwide paw mark that plunged two feet into the snow. It had no claw marks, a rounded rear pad with three rounded lobes in the back, and the distinct rearward ankle drag mark of a cat. Not a small cat, like the day before. A big cat.

Radio and inReach messages both went out to Floyd, and he and Julie hauled back to where we were in his command center truck. Garmin screens, stainless dog boxes, and eight steamy noses poking out of holes in the latter.

We let the dogs out, and after a few minutes of sniffing and encouragement from us, they found the trail. They bombed to the bottom of a 1,000foot canyon and began their chase. We patiently watched on the handheld Garmin screen, walked up and down the road, and observed.

They had run far. Miles. They were still run ning. We needed to get closer for their safety and to be ready in case the perfect scenario unfolded. Kevin, Larry, and I took off up the road, and Floyd and Julie wrapped back down the hill and around to the other side of the canyon.

We had a WMAT tribal biologist with us, so I jumped in with him. His rig was a late-’90s single-cab long-bed gas F350 with a five-speed manual box. The only appropriate thought was, Oh boy.

The next few hours involved chains, winches, mud, deep snow, chains, snow, whining BFGs, more winching, more snow, more mud, and more winching. We worked our way up a road that would test a vehicle in the dry, but somehow we made progress. When we finally stopped making much, I got another order from Larry that I’ll never forget. It left no room for interpretation or interruption.

“Levi. You gotta go find them dogs.”

He handed me the Garmin, pointed into the woods, and said to, “Start walkin’ that way.” Once again, my instinct was to argue, but it was a matter of the dogs’ safety and the possibility of Kevin getting a shot at a lion.

I took off through the snow, following both the Garmin and the tracks of an epic chase. The Garmin showed the dogs about 4,000 yards away, so I was

hustling. It was also about 9 degrees out, so I was motoring to stay warm. Following the tracks was like living the ultimate CSI investigation. There were many places where the cat had climbed boulders and jumped 20-footwide creeks. The dogs’ tracks went through the water. The cat tracks did not.

After about an hour, I reached the bottom of the first canyon. I was greeted by a creek about 15 feet wide and 2-4 feet deep. I wandered up and down a bit, looking for a place to cross, but there was no good option. Hopping with my pack on across frozen boulders and the Garmin in my hand, I inevitably fell face-first into some water that might have been dangerous if I had stopped moving.

Reinvigorated, I scrambled out and trudged on down the creek, only to find that I had crossed a fork in the creek and I was now at the confluence. The only option without hiking an extra hour or two around was to cross back where I was and then back again, and it was deeper and wider than before.

I crossed the first time with little issue. It was boulder-y, slick, and icy, but momentum carried me to the opposite bank. I wandered up and down for a long time looking for a crossable spot back to the side the dogs were on, and I found one. I had to climb and jump from a 10-foot-tall boulder to a five-foot-tall boulder in the middle, then across to a long, flat one that was just above the surface, and it was about 4-5 feet deep. Well, I jumped, landed on the rock, and... slipped into the void. I scrambled out again, holding the Garmin above my head.

Standing on the bank, I looked down at the Garmin and back up where it was showing the dogs. 2,000 yards away, straight uphill.

It was a monster mountain face. Going around to the canyon they were in looked to be about a three-mile trek, and I still would have had to climb, so I chose to go up and over. I swear it was a 70-degree face. It was so steep, most of the snow had slid off. I was holding onto trees and doing crampontype steps for well over an hour. Maybe the most difficult climb of my life.

It warmed me back up, though! When I got to the top, I had dried out and become soaked again with sweat.

My clothes were frozen on the outside and like a sauna on the inside. My beard was frozen, the Garmin soaked with sweat, and I had muttered so many curse words that my mom would have a heart attack if she knew. All the while, I had been following the distant sound of baying hounds and the unthinkably spaced cat tracks. That sucker had been MOVING.

Just over the crest, I was greeted by one of the older dogs who must have heard me swearing as I was falling up the hill. That was one of the most welcoming moments I’ve ever experienced. Just a tired old hound dog named Scout who rounded me up and showed me where to go.

I kept trudging through the snow between the pines for another 20 minutes or so. When I came to a big canyon where my ears were full of baying, I crested the edge and was staring right into the soul of a 180-lb lion about 40 yards away. His gaze was locked on me, and it gave me a big chill and a healthy dose of primal terror. These things mean business. They are designed to kill, eat, and repeat.

A little further down, I found none other than Floyd Green, sitting at the base of the tree the cat was in, calmly whispering sweet nothings to his dogs as they tore the trunk apart, trying to climb up and get the kitty.

I said something to the effect of, “WOW, FLOYD. HOW COOL!”

He turned around and calmly said, “Shhhhh. He’s reading our energy, and it will really help if we stay calm.”

So, we stayed calm. I sat down and took off my puffy jacket with steam pouring out of it. I got back to a comfortable temp and sat with Floyd for what felt like a week, just watching, listening, encouraging the dogs, and learning just how special his relationship with both the dogs and their quarry is.

In reality, it was probably just under two hours. Kevin and Larry, meanwhile, had been stuck, unstuck, re-stuck, and unstuck again probably a dozen times. The Apache biologist who had been cruising with us had broken the four-wheel drive on his F350. They had come around from the bottom of the big canyon and finally met up with Julie, who was waiting at Floyd’s truck.

We watched/heard Kevin and Larry cruising down and across the canyon to us while we gathered up the dogs and tied them off. When they arrived, we did some game planning, and Kevin decided to take a shot with his bow. It was about 9 yards, but at a 75-degree angle. Not an easy shot.

Kevin hit the most perfect dot-shot I’ve ever seen, and the cat tumbled. He took out 6-inch branches on the way down before thumping into the snow and taking one final, fatal leap into a nearby gully. Wow!

I will never forget this adventure. All of the running, effort, challenges, and what some might call “suffering” made it easily one of the most enjoyable days of my life. WH

// Gear can never replace knowledge.

// Your luck can change in the blink of an eye.

// You need to check your bubble level.

// Nothing ruins a hunt faster than bad boots.

// You will never be faster than an elk.

// The more you slow down, the better you glass.

// Stepping over something is always quieter than stepping on it.

// Animals see movement.

BY JAMES YATES

ith only a couple of hours of daylight left on the final day of the season, I was within 100 yards once again of this nearly 240" monarch. The buck I named “KK” was trailing a hot doe, and she was on a game trail heading straight for me–100 yards, 80 yards, 60 yards... My heart was absolutely pounding. KK needed to come about 15 yards closer for me to have a perfect broadside shot. Then, the most unthinkable thing happened. A 170-class four-point came crashing down through the aspens, right for the hot doe. I watched in absolute disbelief as KK disappeared, chasing off the other buck. I literally started crying.

I worked my way back across the canyon to the glassing spot to try for one last Hail Mary before dark. Ty, my partner, was voraciously glassing the pine line, trying to turn the buck back up himself. Then, at about 4:30 PM, Ty caught a glimpse of a heavy antler through the pines. We made a quick plan, and I set off on the stalk of my life. Sundown was 5:01 PM, which meant the legal close of the season was 5:31 PM. I had zero time to waste.

I ran as fast as I could in the deep snow and closed the distance in about 20 minutes. The deer were coming out of the pines up onto the steep, aspencovered hillside. As I was approaching the herd, I pulled up my binos every few yards to try and identify KK with no luck. The evening thermals were coming down the slope very consistently, and time was running out, so I decided to press forward, making sure I stayed below the deer.

Finally, after inching forward another 50 yards, I saw KK materialize from behind some tall brush, about 100 yards away. He was following a doe on a game trail that cut perpendicularly across the steep slope. I crept up to the edge of the pines, making sure to remain under the cover of the pine boughs. Light was fading fast, and it was already especially dark in the timber, so I used this to my advantage. As KK moved along the game trail, I paralleled below him, staying hidden by the darkness of the timber and the crust-free powder below the pines (the snow was crunchy everywhere else).

I paralleled KK for about 40 yards like this, just hoping that he’d stop long enough in an opening for a shot. When he finally stopped in a small opening, I ranged him at 65 yards and drew. Just as I was settling my pin, KK started walking again. I quietly let down and continued to parallel below him in the pines. Within 15 yards, KK stopped again, I ranged and drew, and he started walking again.

This time I didn’t let my draw down. I consciously made the decision that I didn’t need to re-range him because as I paralleled him, I remained about the same distance away from him. Also, my arrow had a very flat trajectory, so even if the range was off a few yards, I knew my arrow would still land in the kill zone.

After a few more steps, KK stopped again. I immediately dropped to my back knee to clear the pine boughs in front of me, and I executed my shot sequence. I remember seeing a flash of my orange vanes burying into KK’s armpit, followed by the distinct “thunk!” of a body cavity hit. What I had visualized every day for the last four months of hunting this buck had finally taken place. KK took one big leap behind some tall brush, and that was it. He just collapsed, dead. WH

TURNING POINT:

After ranging the buck, drawing his bow and settling his pin, the author had to let down as the buck started walking again. When the same scenario happened again, he consciously made the decision not to let down and re-range the buck because as he paralleled him, he remained about the same distance away.

• Dependable German-sourced glass, fully multi-coated, for superior clarity and contrast.

• First Focal Plane (FFP) and Second Focal Plane (SFP) models available — you can pick based on whether you need true sub tensions at all magnifications (FFP) or prefer a cleaner reticle view (SFP).

• Large zoom range + big objective lens - excellent light gathering and crisp clarity at long distance.

• Resettable turrets, with zero-stop and generous elevation travel — built to dial in long-shots precisely.

• Rugged build — waterproof, fog-proof, shockproof.

• Long range: can measure out to ~1,500 meters, which gives margin for 1,000-yard shots.

• Ballistic chip + environmental/ incline data — helps generate accurate firing solutions. Portable, lightweight, field-friendly build.

• Element Ballistics App provides accurate and reliable firing solutions through a friendly user interface.

Element Ballistics App

For hunters looking to push their limits without blowing their budget, the Helix Gen-2 paired with the Helix 1500 delivers a compelling, capable package. You get clarity and quality that punch above the price tag. With this combination of precision, reliability, and data, a successful hunt is no longer a dream—it’s a reality. Whether you’re treating yourself or looking for the perfect holiday gift for your next generation of hunters in your life, this setup checks every box.

Outdoorsmans Gen 2 Carbon Innegra

Outdoorsmans Pan Head Gen 2

Outdoorsmans Tripod Holster

Outdoorsmans Titanium Self-Timing Muzzle Brake

Outdoorsmans Arca+Picatinny Rifle Rail

Browning Hell's Canyon X-Bolt Long Range McMillan

Leupold VX-6HD 3-18x50 FireDot Duplex

.300 Winchester Magnum

Timney Trigger

BY JARYD BERNSTEIN

A marine veteran capitalizes on two incredible opportunities

In 2010, I deployed with VMFA-312 as part of the strike unit tasked with providing close air support to coalition forces on the ground for OEF (Operation Enduring Freedom). On this deployment, I unfortunately won myself a spine injury, which leads us into how I was able to hunt two incredible tags in 2024.

In the early days of summer 2024, I received a call about a Unit 10 Arizona archery bull tag, as I am on the list of VA-approved, service-connected disabled veterans who can accept turned-in tags from the state of Arizona. I was well aware of the magnitude of this opportunity and jumped right on the phone to the team at Drop Tyne Outfitters (DTO) to see if they had someone available to help and call for me. I had hunted with DTO in the past, and once again, they stepped up and instantly jumped on board–moving folks around and doing everything they could to help me with this unique opportunity.

The hunt started slow. We had 90-degree temps, a not-so-ideal moon, and, in turn, minimal rut activity leading up to the start of the hunt. It’s easy to get somewhat discouraged with those factors and this massive tag in your pocket, but we didn’t. We just kept doing what we had to do to find the bulls and give ourselves a chance.

On the evening of the third day, we spotted a few bulls and cows about 1.5 miles away from the knob we were glassing from. With the minimal activity, we knew we needed to get up high, be patient behind the glass, and hunt with our eyes for a while. When you look at a big bull, a really big bull, you know what you are looking at. We knew, even at over a mile out, this bull was exactly what we needed to go after. The mood on the hill changed instantly. We didn’t have the time that afternoon to close the gap. We could have literally run over there, but we all knew that was the wrong call, as there were other elk in between us. So, we watched until dark and then spent all evening making a plan. Who would be on the hill glassing, which direction we would hike in from if the wind did “X,” and which direction we would hike in from if the wind did “Y.”

and we kept moving. We made it to within 300 or so yards of the elk, and the sun was setting, but our approach, based on the wind, put us directly in the sun. We had to move slowly through a large open area, only moving as the sun set. We stayed in the shade so as not to be highlighted for the elk to pick us up.

The final gap we had to close was very open. We were within 180 yards of the elk, but our next tree was 105 yards away. We started crawling, on our faces, in the grass and dirt, with our allergy issues still present. It was honestly disgusting–noses flowing, holding in sneezes, and dragging our faces in the dirt. It took us nearly an hour of crawling to make it the 100-ish yards to the final tree between us and the elk. We still had not seen the target bull since leaving the glassing point, but we were confident that he was around the cows that we could see.

When we got to the last tree, we tried to recover from our crawl and allergy party while we worked on locating the bull. We had nowhere else to go–there were 15 or so cows within 100 yards of us, one small bull at about 65 yards, and a handful of cows in a small group of bushes within 50 yards of us. We had to hope the big bull would start to cooperate, or else we were going to have ourselves a nice sunset walk back to gather all the gear we left on the hill.

After a little less than 10 minutes, the big bull finally stepped out. Grady and I both looked at each other in near disbelief. I already had an arrow ready, and Grady was instantly on his rangefinder. We waited for the bull to stop–he was at 79 yards. Grady was giving me updated ranges by the second as I slipped out of the tree we were using as cover. My only shot was from my knees, based on the tree branches that were in the way from the standing position and the exposure I would have if I took one step further. Seventynine yards, from my knees.

“I was in my own head, essentially adding no value to the situation and wondering if I should hang my bow up for good.”

We had plans on plans, and as you can imagine, the elk did not cooperate the next morning. We hiked in, never found the bull, and neither did our spotter on the hill. The rollercoaster we all love called elk hunting had once again given us a dip, but we knew the bull was here, and we knew we had to get back up high and locate him. We sat on the hill all day–hours of exposed sun, burning through water and food to keep us behind the glass. Nothing out of the ordinary for anyone who shares our hunting addiction.

At around 1530 (3:30 PM for those of you without a DD214 and anger issues), we turned the bull up. He was easy to identify with the inline on his right side and giant thirds. We had minimal time to close the nearly one mile between us, but with minimal animals in between us and having watched another elk get killed that morning near his location, we knew we needed to move.

We ran off the hill–literally. We left our packs, water, tripods, everything. We knew we had to go light and fast. To add to the fun, the allergy levels were high for this year. As Grady (DTO guide) and I made our way quickly toward the elk, we both suddenly went into allergy attacks. At one point, Grady sneezed at least 15 times in a row, which is about as not ideal as possible as you are moving in on elk.

I had one allergy pill in my bino harness, so we split that, chewed on it for a faster effect (I’m not sure if that works, but it made sense at the time),

I let the arrow go. The bull was standing still, perfectly broadside, feeding. We both heard what sounded like the arrow hitting branches. The bull didn’t move. I was convinced I’d missed, and even got a bit vocal with Grady about how I felt I had just blown the greatest opportunity I’d ever had. Grady stayed calm and confident. He told me to get another arrow ready, and as I was quietly doing so, the bull turned and gave us another shot, opposite the first shot, perfectly broadside again.

I have never been so nervous taking a shot. As I was trying to settle my pin, Grady had eyes on the first arrow. It was perfect. Sticking out of the bull, good blood, a great first shot. I couldn’t see that arrow in all my emotion as I let the second arrow fly. The second arrow connected. It was a bit further back than we wanted, but the bull instantly showed signs of being hit and ran off into the trees just out of our sight. Grady had seen the first arrow, we both knew the second one hit, and we both knew the right call was to give the bull some time.

Anyone who has been in the position to “give the animal some time” knows how we were feeling. We sat, and I questioned everything. Grady remained positive and productive, updating our friends in the area, getting a route planned, etc. I was in my own head, essentially adding no value to the situation and wondering if I should hang my bow up for good. I had never been under 100 yards from a 390"+ bull, and from my seat, I had just screwed it all up.

I couldn’t believe what Grady was telling me about the first arrow since the bull did not move at all, but Grady was right. The first arrow was perfect, and after giving him about an hour to settle, we walked up on the bull not 35 yards from where he was when we shot him. A 392" Arizona giant with a bow–a memory and a pile of lessons I will never forget.

The craziness of my 2024 hunting season did not stop there. I headed to New Mexico to help with another elk tag that a buddy of mine from Virginia had. While on this NM hunt, I got a call about a Kaibab rifle deer tag. Those of you who know what that means know that I may have been the luckiest hunter in the world for the entire year of 2024. I told my buddies about the call, and they essentially asked me why I wasn’t packing already.

The call came on a Monday, and the hunt started on Friday. I had to get back to AZ and turn my gear around from helping with a NM elk hunt to hunting for myself with a rifle north of the Grand Canyon. Talk about a welcome logistical challenge. I once again worked with Drop Tyne Outfitters to secure some help and made it to the Kaibab Thursday night, just as the folks in their deer camp were sitting down for dinner.

The DTO crew is known for their success on the Kaibab, and they have earned that recognition. Three big bucks got killed over the next three days. I was not the shooter–the other clients in camp were. One buck scored just under 200", one just under 190", and a slammer of a buck, killed by a 16-year-old on his first deer hunt with his dad and the DTO crew, hit the ground at 206". I got to help glass as those guys were successful on that giant, and it may be one of the neatest things I have done in the woods. Sharing in the excitement of that kid having such a great hunt was something I did not know I would benefit from at such a high level. After that, I was the only tag in camp. The entire DTO crew jumped in to help glass, but they/we had knocked down some giants, so my expectation of finding another “once-in-a-lifetime” buck was minimal. I think I was trying to be “realistic,” which turned out to be thankfully out of my control.

We glassed a lot, and we did our due diligence, picking apart the country we knew the big bucks were in this time of year. When we didn’t turn anything up, we decided to move areas.

On our move, in the middle of the day, Mikey from DTO spotted a buck bedded. We could only see a partial side of one antler, and we got into a bit of an argument about how big the buck was. One guy could see nearly nothing, another guy could see a decent view, and I could see the entire side of the buck. We laughed about not being able to tell what he was, but then he stood up and turned. This is where the panic happened.

We panicked because he was huge. Not 45 seconds later, I had my rifle, Mikey was giving me a range, and I fired my only shot of the trip. The buck ran over a small rise and we lost sight, but knew he was hit good. He made it about 40 yards and died on his feet, running. He flipped over and got wrapped up in a tree. Done. When we got to the buck, I couldn’t believe it. We had just knocked down an AZ giant, only a few weeks after what will probably be the biggest bull I ever hunt. The buck ended up scoring 202", but what makes him a bit more special to me is his mass. He is the heaviest mule deer I have ever put my scope on.

I am thankful to the State of AZ for their program that allows non-profit organizations like Changed By Nature Outdoors (CBNO) to get disabled veterans into the woods. I won’t detail what the woods do for me mentally, but I can tell you it’s life-changing and necessary. 2024 will forever be the season to remember, and I will never be able to thank the DTO crew or CBNO enough for the impact they have had on me. WH

Hanging around the Outdoorsmans headquarters for the last seven years, I’ve had my fair share of time behind some truly exceptional glass. Over those years, it’s quite obvious that there are 4-5 major players when it comes to top-tier glass, so anytime we catch wind of someone creeping their way into the majors, all ears perk up.

Element Optics’ rifle scopes have my attention. Their design team is composed of a handful of top competition shooters, hunters, and Swedish military veterans, providing Element Optics with decades of in-field experience in a number of different shooting disciplines. Their singular purpose in coming together was to create a better option for consumers based on their needs.

Recently, I put over 250 rounds out within a span of two days at varying distances, from 150 yards to roughly 800 yards, at a recent NRL Hunter match in Clovis, NM. It was the perfect chance to get familiar with the Nexus Gen II 4-25x50 and gather up some first impressions.

I’m not one to hold too much stock in how the product is delivered–my opinion has grown to it being a waste of money and resources to deliver an unboxing “experience.” That being said, the Nexus Gen II comes in a suitable box with custom-cut foam holding it in place. The rifle scope includes a throw lever, a neoprene cover, a sunshade, an aperture ring, a lens cloth, and a thread protector. That’s a pretty sweet deal compared to some brands that toss an optic in a cardboard box and call it a day.

The scope itself feels really solid in hand. It’s a 30 mm tube with a 50 mm objective and a hard-anodized finish. It has a clean profile, easy-to-read indicators, and highly textured adjustment rings that feel impossible to slip up on.

Zero-Stop Turret: One of my favorite design features of this rifle scope is the turret. It’s responsive, it’s “clicky,” it’s accurate, the adjustment lines actually line up to the indicator (one of my biggest frustrations with many rifle scopes), and it’s almost too easy to zero. I say almost too easy because, while it did have me stumped for a solid 10 minutes (failed to read the user’s manual and I thought I’d seen it all), once I figured it out (read a book), it was done in roughly 2.3 seconds and felt like I was missing something. But I wasn’t. It was zeroed–no tiny screws, no tools, no Rubik’s cubes–just dial, pick up the cap, and place it back down on the zero. Done.

Once zeroed, the turret continues to shine. Like I mentioned earlier, the physical, audible, and visual feedback from adjustments is excellent. The turret features a zero-stop that goes 5 “clicks” past zero. Some shooters prefer this flexibility–for me, it was something to get used to. Something I found extremely useful was the revolution indicator. A humble little lever that flips between a ‘1’ and ‘2’ depending on whether you’ve made a full revolution or not is a massive help when making numerous adjustments between shots.

Illumination: The Nexus Gen II comes stock with a 10-step illuminated reticle easily controlled with a soft-touch rubber button located on the windage turret–useful for those early mornings or dawn shots. One thing to note: on some occasions, the required CR2032 battery will not work due to the bitter coating. You can remove the coating by licking it off, and if that doesn’t work, use rubbing alcohol. Or, be a smarter man than me and buy the non-coated version.

Eye Relief and Eye Box: Two minutes to take four shots in different positions and targets quickly makes you realize how important it is to have comfortable eye relief and a large eye box. During the match, I did not struggle to get right into the perfect eye position between shots, even while wearing bulky ear and eye protection. Admittedly, I do not wear either during hunts, which I can only imagine will make getting into the sweet spot that much more of a breeze. When looking for a rifle scope, the eye box is important to me, and this rifle scope passes with flying colors.

Glass and Magnification: I found that the 4-25x range is the goldilocks zone between mid-range and long-range shooting. Never did I feel a target was out of reach, and even more importantly, I never felt completely “boxed in” at the nearer ~150 yard targets. The roughly 6x variability made for incredibly quick target acquisition after taking a shot during the match. The ability to throw the magnification down to 4x, find the target, and just right back into a comfortable 12x using the throw lever was invaluable during the match. I don’t think I need to spell out why that’s valuable for hunting scenarios.

My early impressions of the glass itself suggest that it’s clean, it’s bright, and it’s accurate. At higher magnification levels, I didn’t lose too much brightness, nor did I notice any color fringing or excessive blurriness. The glass is very solid for the price.

All in all, the Element Optics Nexus Gen II feels like a well-designed rifle scope; whether you’re looking for an NRL hunter-style competition, strictly hunting, or long-distance rifle scope, or you’re like me and need one rifle scope to be capable of all things, I wouldn’t hesitate to call the Nexus Gen II a smart purchase.

It’s waterproof, fogproof, shockproof, and comes with a “Platinum Lifetime Warranty” that covers any rifle scopes damaged through normal use and requires no registration, proof of purchase, or transfer. Basically, if you have a problem, Element will fix it. I haven’t tested the warranty, but it’s worth noting. The accessories included in the box are also a point to the good–it’s the small things that add up to a good experience, and the Nexus has them covered. WH

TECHNICAL SPECS:

Magnification: 4-25x Objective Lens Diameter: 50mm

Elevation Adj: 100 MOA Windage Adj: 40 MOA

Weight: 30.7 oz Cost: $2,199 Contact: Element-Optics.com

Icouldn’t shake the feeling that something bad was going to happen to my bow as I loaded it into the case. I hate those thoughts, but the bow for this trip was integral in my mind. I just needed it to show up–unlike other trips where I could make do. This hunt was to take place in the most remote reaches of North America, and it was a trip I had been dreaming about for a long time. After four days of travel, my boots would hit the dirt in the northernmost portion of the famed McKenzie Mountains in the NWT.

I was headed to chase mountain caribou. These caribou, true to their name, inhabit the high ridges and slopes of the range during the summer months, before moving down into their winter range. This hunt was high on my list for many reasons. The first of these was wanting to experience a hunt in the McKenzie Mountains. Having heard stories of this vast and seemingly untouched place, I was immediately intrigued. Second was the animal itself. Caribou have always fascinated me. It is one of the few animals of which no two are quite the same. They live in the most remote reaches of the north, and unfortunately, hunting opportunities for caribou as a whole are decreasing.

About eight years ago, a good friend of mine mentioned something to me that I really took to heart. He said, “If you want to caribou hunt, do it now.” That statement really set the wheels in motion. I really wanted to chase all the species of caribou with my bow. His words, “do it now,” became even more meaningful as before I was able to embark on my first caribou hunt, a DIY hunt in Alaska, the Quebec-Labrador herd was shut down to hunting.

Here I was, over eight years later, about to chase the last species of caribou on that list, the mountain caribou–one of the most desirable among the lot. Their massive antlers and large bodies make them a standout subspecies. I had the tag, the flights, a guide–everything was in place. I just needed to grab my bow, get on the mountain, and find one that would lend itself to getting within bow range.

As I waited in baggage claim in Yellowknife for an overnight before flying to Norman Wells the next morning, then into base camp the day after that, I felt a pit in my stomach. The bow never showed up at the luggage pickup. For some reason, the bow never transferred at my last stop. At this point, I was not too worried. I had two more days, and there were over four flights that it could get on to make it. The next day, I got on my next flight. The bow did not show. I was banking on the hope that someone put it on a plane, and it would eventually turn up. To make a long story short, the next day, if not for an acquaintance who knew someone who went to the airport and practically stole the bow and put it on a flight, I would have left for the hunt bowless. It arrived five minutes before we were going to take off on the charter flight into the mountains. My anxiety about something happening to my bow subsided, and I knew I was about to hunt a mountain caribou.

As we flew into the mountains, the scale of where I was headed began to grow. Valleys and rivers started stacking up. Ridges and slopes seemed to expand into an infinite range of mountains, as if I were looking at them through two opposing mirrors. The vastness of the McKenzies seemed endless.

From the float plane, we were dropped over 150 miles from where we took off, at a small lake where a cabin sat tucked into a patch of willows. The cabin, decorated with scars from bears trying to break in, is where we met Colin, our guide for the week. Unless they’re a resident of NWT, every hunter is legally required to hunt with a guide. The plan for the week was to scout out the mountains behind the cabin the first day, then head up and backpack into the head basins and valleys across the way.

With the sun never really setting, that night just bled into the next day. In light rain, we loaded up the packs and made a climb to the top of the mountain behind us. As we crested over, I caught the tips of a bull about 250 yards below us. It was a nice bull, but not a first-day shooter. We worked around to see if he had any friends. Being extremely cautious, we backed out, went around the mountain, and popped out on the other side with a good view and farther away so as not to spook the bull, just in case.

“The scale of where I was headed began to grow. Valleys and rivers started stacking up. Ridges and slopes seemed to expand into an infinite range of mountains, as if I were looking at them through two opposing mirrors. The vastness of the McKenzies seemed endless.”