Western Forester

April/May/June

Connecting Small Forest Landowners to Carbon Markets in Washington State

By John HenriksonIn 2021, the Washington State Legislature passed the Climate Commitment Act (SB 5126), which established a cap and invest carbon emissions reductions program for the state and included the potential to establish a compliance market for forest carbon credits. A known challenge with advancing successful forest carbon projects is that the expertise, data, and financial resources necessary for implementation are so significant that small forest landowners (SFLO) are typically precluded from participating.

gator account for carbon offsets projects; 2) development of offset protocols in coordination with the Department of Ecology (ECY);

3) an incentives framework to facilitate carbon-focused forest practices; and 4) methods and policies to support SFLO participation.

Washington Farm Forestry Association (WFFA) assembled a team of carbon policy, protocol, research, and life-cycle analysis experts, along with many SFLO, to explore the current opportunities and issues in the carbon market and to report on these recommendations to the Legislature by the end of June 2024.

Although these programs are not fully compliant with the established carbon offset protocols established by the ECY, and thus preclude participation in the regulatory carbon market, carbon sequestration and storage outcomes undertaken through these programs are accessible and attractive to SFLO. A survey conducted among active forest landowners indicated strong support (generally greater than 80 percent) for participation in funded carbon sequestration-focused programs.

The practicalities of connecting landowners to the carbon program

The workgroup identified several “pathways” for landowner participation, depending on a site’s attributes, age class, stand condition, management objective, etc.

The legislature sought to address this challenge in the Climate Commitment Act by establishing a SFLO Carbon Workgroup tasked with returning recommendations on:

1) a pilot program to develop an aggre-

We identified numerous existing incentive programs for improved forest management practices that either directly focus on carbon sequestration or could be modified to fulfill that objective. These incentive programs include:

1) Cost-share and per-acre payment over a contract period for implementing forest treatments to increase forest carbon via American Forest Foundation’s Family Forest Carbon Program and Natural Resource Conservation Service’s Conservation Reserve Program.

2) Payment for increased carbon volume due to extending harvest rotation via various private program developers in the voluntary carbon market.

3) Payment for standing timber in harvest-restricted or conservation-oriented sites via the Department of Natural Resources’ (DNR) Forest Riparian Easement Program.

4) Conservation easements and purchase of development rights, especially where forest land is vulnerable to conversion and development via various land trusts and government programs.

1) Afforestation: Create new forests on underutilized, marginal land

2) Improved Forest Management (IFM): Improve underperforming/unmanaged forest land

3) Extended Harvest Rotation: Increase timber/carbon sequestration over time per unit area

4) Legacy Forest Management: Maximize long-term carbon storage while harvesting excess

5) Wildfire Resilience: Optimize durability of forest carbon in the context of wildfire risk

6) Urban & Community Forestry: IFM in the context of non-typical forested landscapes

7) Avoided Conversion: Prevent forestland from being lost to other non-forest uses

Carbon-focused silvicultural practices were explored and defined, recognizing that the conventional approach of “protecting” forests and their carbon by ceasing harvest and management may not lead to the desired outcome. Practices should be designed to maximize

Western Forester

Society of American Foresters PO Box 82836

Portland, OR 97282 (503) 224-8046

https://forestry.org/western-forester/ EDITOR: Andrea Watts, wattsa@forestry.org

SAF NWO MANAGER: Nicole Jacobsen, nicole@westernforestry.org

Western Forester is published four times a year by the Oregon, Washington State, and Alaska Societies’ SAF Northwest Office

The mission of the Society of American Foresters is to advance sustainable management of forest resources through science, education, and technology; to enhance the competency of its members; to establish professional excellence; and to use our knowledge, skills, and conservation ethic to ensure the continued health, integrity, and use of forests to benefit society in perpetuity.

STATE SOCIETY CHAIRS

Oregon: Amanda Sullivan-Astor, CF (503) 983-4017, aastor@oregonloggers.org

Washington State: Samantha Chang, NorthPugetSAF@gmail.com

Alaska: Mitch Michaud, mitchmichaudak@ gmail.com

NORTHWEST SAF BOARD MEMBERS

District 1: Ed Morgan (303) 476-1583, edmorgan4@msn.com

District 2: Ron Boldenow (541) 350-5356, rboldenow@cocc.edu

Please send change of address to: Society of American Foresters, 2121 K Street NW, Suite 315, Washington, DC 20037 membership@safnet.org

Anyone is at liberty to make fair use of the material in this publication. To reprint or make multiple reproductions, permission must be obtained from the editor. Proper notice of copyright and credit to the Western Forester must appear on all copies made. Permission is granted to quote from the Western Forester if the customary acknowledgement accompanies the quote.

Other than general editing, the articles appearing in this publication have not been peer reviewed for technical accuracy. The individual authors are primarily responsible for the content and opinions expressed herein.

the carbon sequestration rate for the site while storing carbon in high-quality timber. At the same time, we should be implementing a balanced strategy to optimize carbon, timber, and environmental objectives at varying scales and granularity.

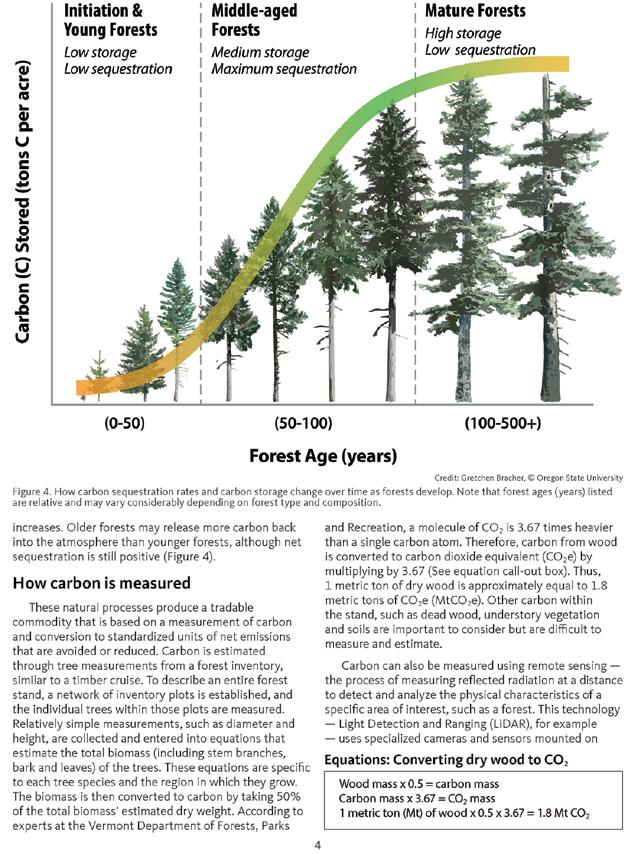

Forest carbon research indicates that the highest rate of carbon sequestration occurs when the forest is in its most vigorous stage of growth in the middle decades (20 to 60 years old). Sequestration rates can be sustained for a while longer in mature forests if they are thinned and managed, but over time the rate slows as the site capacity is reached. Ultimately, it declines as mortality exceeds growth.

Periodic timber harvesting provides an opportunity to maintain this high sequestration rate indefinitely by moving stored carbon from trees into a separate carbon pool via wood products in the human-built environment. Producing higher log grades that increase the ratio of long-lived wood products, full utilization of wood byproducts, and maintenance of a robust, localized wood processing infrastructure all help to reduce carbon emissions associated with the timber industry.

To determine if the small forest landowners are achieving the desired objectives through the carbon-focused silvicultural practices, the state needs a mechanism to evaluate the efficacy of the recommended programs and practices. A well-developed measurement, monitoring, reporting and verification (MMRV) protocol is essential to provide investors, government agencies and the public with confidence that these proposed recommendations are cost-effective and beneficial—similar to the protocols that carbon projects are audited under. A key

Next Issue: Forest Health Update

component of the Carbon Workgroup is the research team at University of Washington’s Natural Resource Spatial Informatics Group. They are working to develop remote sensing technology to measure and predict forest responses to various management practices. If we are successful, we should be able to accurately determine how much carbon is being sequestered across how many acres, within what time frame, and at what cost.

Finally, the successful implementation of these recommendations will require the creation of a state-level organization to develop and administer programs, coordinate research and technical development, engage stakeholders, act as a clearinghouse for funding mechanisms, and maintain a project registry and forest metrics database.

A small landowner perspective on carbon markets

As the manager and co-owner of Wild Thyme Farm, a 150-acre mixed forest and farm landscape in southwest Washington, I have been exploring opportunities for carbon sequestration in the context of a long-term family forest plan. Fifteen years ago, we participated in a pilot program to sell carbon credits in the voluntary offset market and learned a lot about what doesn’t work with the traditional model. The 100-year commitment to maintain a specific and expensively monitored volume of carbon, combined with a carbon price far below the value of the timber, led us to a different approach to achieve similar sequestration objectives in a way that recognizes the forest’s full value and encourages landowner participation and management flexibility.

We work with multiple age classes and species within a challenging topography and hydrology that is not well suited to conventional timber production. With the many management units in the farmland portion, as well as in the forest, we have implemented projects for agroforestry, afforestation, rehabilitation of damaged and underutilized stands, extended harvest rotation, and legacy forest management. Experimenting with different treatments at varying scales has informed us how to quickly and efficiently meet the triple objectives of carbon, timber

To deliver the recommendations requested by the legislature in the Climate Commitment Act, the Small Forest Landowners Carbon Workgroup developed the following workflow to guide the process

and environmental outcomes, all with an overriding consideration of aesthetics— we want it to look nice!

Carbon and timber objectives are so closely aligned that good forest management is sufficient to meet the majority of the natural carbon sequestration goals for Washington State. We can innovate and change our methods a little bit to do even better, but the low-hanging fruit is returning unmanaged land into production and managing “protected” lands to keep them from losing their carbon due to wildfire, crowding, and poor health.

The two key metrics to measure (on a per-acre basis) are the carbon sequestration rate and the durable wood volume in standing trees and wood products. If one or both are not performing up to the site’s capacity, or if the site is not managed in a way to sustain these into the future, then we are missing the opportunity to incorporate

carbon among our other management objectives.

Our hope is that the recommendations of the Small Forest Landowner Carbon Workgroup will inform and inspire the legislature, state agencies, and the public to enable landowner participation in carbon incentive programs and markets. Carbon sequestration in forests is by far the most cost-effective natural climate solution, and the economic and environmental co-benefits of comprehensive

land management allow us to tap the full potential of our Evergreen State. WF

John Henrikson is the project coordinator for the SFLO Carbon Workgroup. Henrikson is an active member of the small woodland owner community, serving as chair of Washington Department of Natural Resources’ Small Forest Landowner Advisory Committee and was co-chair of the Washington Tree Farm Program. He can be reached at john@wildlogic.com.

Exploring the Potential Effects of an Expanding Forest Carbon Market on Working Forests and Communities in the United States

By Dave Bubser, Kathryn Fernholz, and Eliza MeyerDovetail Partners and the U.S. Endowment for Forestry and Communities recently released a concept paper that explores the potential effects of an expanding forest carbon market. The paper is part of a broader project supported by a grant from the Endowment to Dovetail Partners to work in collaboration with Cambium Consulting to create a shared understanding of how carbon markets may impact working forests and communities in the United States.

The project has four phases designed to raise awareness and encourage consideration and integration of approaches to maximize positive outcomes and minimize negative impacts. The project includes the concept paper, a survey, development of mapping and impact assessment strategies, and a workshop on June 17-18, 2024, in Nashville, Tennessee.

Why a concept paper now

Within society, there is a broad awareness of climate change. Brands and other corporate entities are increasingly recognizing the economic and reputational threats to their businesses and operations if they fail to act. Currently, 38 percent of Fortune Global 500 companies have set a public net-zero target. Consequently, demand for carbon offsets is expanding and financial investment strategies are beginning to acknowledge the value of carbon. Offset markets provide a mechanism to engage private capital and can be a powerful vehicle for

advancing protections for related social and ecological values.

For decades, investors have engaged in forestland ownership because of the dependable and stable financial returns, derived in part from sustainable timber harvesting. Now, trees have additional economic value for sequestering carbon, and the land base serves as a carbon sink. In recent years, commercial timberlands in the U.S. have been acquired by banks and joint ventures speculating on future carbon offset markets. Long-term projections for the carbon offset market continue to reflect expectations for significant growth, with demand expected to increase dramatically in the coming years. In the last decade, more than 326 million carbon credits have been issued to projects in the U.S., and approximately 58 percent of those credits were issued from forestry projects. (See USDA Report to Congress, A General Assessment of the Role of Agriculture and Forestry in U.S. Carbon Markets https://tinyurl.com/3kxdac4s.)

Offset prices for the voluntary market in the U.S. are in the range of $12-$15/ton for Improved Forest Management (IFM) projects, and up to $35/ton for some Afforestation/Reforestation (A/R) projects. Prices in the regulatory market are equal to or above those in the voluntary market, and prices are expected to rise into the foreseeable future. Already, forest carbon offset prices are locally competitive with lower value traditional forest products such as pulpwood, and chip and saw logs. As offset prices increase, it’s reasonable to anticipate price competition with mid-value forest products in the future.

The protocols under which carbon credits are issued continue to evolve. In 2023, there were 16 forestry offset protocols applicable to the U.S., with others under development, but offsets have been issued using only seven of the 16. Given the age of most protocols and the changes taking place in the forest carbon market, now may be an appropriate time for updates to existing methodologies to introduce a more comprehensive approach to forest carbon projects.

Bundling multiple related issues (e.g., climate, biodiversity, community viability) may more effectively achieve targets, compared to an ‘a la carte’ approach of stacking multiple issue-focused instruments and corresponding payments for specific values in a single project. It’s not clear that current options are tailored to a modular approach. However, the market is calling for “high-quality offsets” that are at least partly defined by many stakeholders as nature-based approaches that deliver co-benefits. In the absence of a federal government-led effort to establish a national carbon market, private sector leadership as well as state-level actions are filling the gaps.

A market in flux

This project and accompanying concept paper were motivated by the growing interest in understanding forest carbon markets, as well as the rising concern that the downstream impacts of these investments are not well understood or sufficiently considered. To some degree, this concern is a variation on the theme of maximizing near-term profit without adequately considering longterm externalities. Carbon markets are well-intentioned and methodologies provide guardrails, but economic levers can distort landowner objectives and their management outcomes.

From an economic perspective, there are potential carbon market impacts on access to raw materials for traditional forest-based economic activities and the diverse products and services that forests provide throughout homes and businesses. As more forestlands are committed to forest carbon projects, there is concern that, by design, less timber may be harvested, even on sustainably managed forests. Reduced harvest levels could negatively impact forest products industries, which in turn can lead to direct and indirect job loss, mill closures, loss of tax revenue, and decline in rural, forest dependent communities. Expansion of forest carbon projects could also lead to increases in forest carbon stocks beyond levels conducive for maintaining forest

health and resiliency. From an ecological perspective, carbon projects may affect forest biology, associated climate mitigation capacities and risks, and the diverse habitats that forests provide within their essential role of supporting biodiversity. Relationships between species richness, management intensity, carbon stocks in trees, and site productivity are variable depending on site characteristics. As such, there is a high degree of flexibility within forest management approaches to achieve biodiversity and climate mitigation objectives.

From a social perspective, there are potential effects of carbon markets on the needs and values of local communities, employment and household incomes, state and local tax revenues, and associated quality of life considerations. Forest carbon offset methodologies that result in decreased and/or deferred harvest, or indirectly limit silvicultural practices designed to reduce tree stocking and or fuel levels, can lead to increased risk of wildfire, insect infestations, and reduced diversity in habitat. In other words, there may be instances where increasing forest carbon stocks in the near term (as incentivized by offset markets) and maintaining long-term forest health are in conflict.

Considerations besides carbon

Currently, most forest carbon project methodologies rely on reduction, deferment, or exclusion of harvesting activities to increase carbons stocks and generate marketable carbon credits. However, most existing projects haven’t resulted in much, if any, reduction of harvest levels. This may change as private and public climate pledges and related investments in forest carbon offsets increase in both number and scale. Decisions about how forests are managed determine timber harvest levels and have effects on forests, forest product markets, and forest-dependent communities. The forest and wood products sector supports livelihoods and cultural identity within hundreds of communities throughout the U.S., particularly in rural, forested areas. Suburban and urban communities are also the locations for significant forest products secondary manufacturing, finished goods production, distribution, and company operations. Urban and suburban forest management also contributes to climate mitigation strategies and to the supply of wood and fiber

SOURCE: FREY, 2022

In “Defining and Measuring Forest Dependence in the United States: Operationalization and Sensitivity Analysis,” the study authors used the following variables–forest area, earnings, employment, and indigenous population–to identify what could be considered forest-dependent communities. Their analysis identified 524 that met these criteria. Image taken from Concept Paper: Exploring the Potential Effects of an Expanding Forest Carbon Market on Working Forests and Communities in the United States.

through urban wood utilization.

While many forest product companies and landowners are strategizing around carbon markets while continuing to meet their timber harvesting objectives, conflict has begun to develop at the state and local levels in response to the acquisition and purchasing of working timber lands by forest carbon project developers with stated intentions to significantly reduce harvest levels (i.e., 40 percent reduction).

With the objective of enhancing forest carbon sequestration and storage, the new owners may also make other changes to how the land is managed that will impact local interests. Conflicts are also emerging

as carbon prices increase and compete with some traditional forest products. In both West Virginia and New Hampshire, concerns have surfaced about the ongoing viability of lumber mills, impacts to jobs, and loss of tax revenues. Changes in land ownership and management activities can impact traditional uses, recreation access, and other social and cultural values. Legislation has been drafted to address issues relating to forest carbon credits, and many states have enacted a variety of climate related policies.

The urgency of addressing the climate crisis has arguably led to focusing too

Continued on page 19

Aligning Carbon Considerations with Wildlife Habitat Priorities

By Andrea WattsIn 2023, the Oregon Legislature passed legislation that renamed the Oregon Global Warming Commission to Oregon Climate Action Commission (OCAC) and created the Natural and Working Lands Fund. With an investment of $10 million, this new fund would direct certain agencies to address natural climate solutions in their management objectives.

and working lands play in the carbon sequestration piece of the puzzle. Much of what they have identified as solutions aligns with work that we’re already doing so we don’t have to pivot to completely new work. However, considering watershed restoration and habitat restoration through a carbon sequestration lens is new work for us. In partnership with scientists and our sister agencies, we’re still figuring out what that looks like on the ground. We may modify our work slightly to include carbon sequestration and carbon capture as one of our objectives in our restoration.

We’ve lost a ton of our streamside and riparian vegetation, and there are a disproportionately high number of at-risk species dependent on this particular habitat. Restoring this habitat has always been a priority for the department and where there’s riparian reforestation projects that we can partner with private landowners and Tribes, that’s going to continue to be a wonderful opportunity for us to have those co-benefits of carbon sequestration and habitat restoration.

How are you navigating projects where habitat restoration priorities don’t align with carbon sequestration goals?

Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) is one of the agencies that has received funding for wildlife habitat restoration projects that align with the OCAC’s goals of carbon sequestration and climate resiliency. I spoke with Sarah Reif, the habitat division administrator for ODFW, to learn more on how the agency is incorporating carbon sequestration and climate resiliency into wildlife habitat restoration projects.

What follows is our conversation edited for length and clarity. How does the Natural and Working Lands Fund’s objective tie in with ODFW’s wildlife habitat restoration priorities?

The Oregon Climate Action Commission prioritizes the role that natural

For example, we are working in estuaries to restore habitat connectivity for native migratory fish or salmon while reducing flooding issues for private landowners and communities. We found federal infrastructure dollars to replace failing tide gates and are working with willing landowners and partners. An element we’ve added to these projects, which the Oregon Climate Action Commission gave us funding for, is seagrass restoration because science shows that seagrass is a major opportunity for carbon storage. Historically, when we’ve worked on channel connectivity, we’ve focused primarily on fish passage.

Another example is rangeland restoration work underway in Wasco County. The project area has checkerboard land ownership that includes our wildlife areas and private land. There are a lot of invasive grasses that are causing problems by outcompeting natives and reducing biodiversity, and increasing the fire frequency. This project is removing the invasives, but because there is also a carbon sequestration goal, we’re increasing and prioritizing our focus on perennial bunchgrass restoration because bunch grasses are another known opportunity to sequester carbon. Historically, we would have done some seeding of perennial bunch grasses but now we’re really putting extra muscle and effort into making it a taller priority and doing so at landscape scales.

One area where there’s a lot of fertile ground for increasing carbon sequestration is in riparian floodplain restoration.

One example is managing sage grouse and pronghorn in the sagebrush. Juniper is encroaching into what historically would have been shrublands and grasslands. One of the primary restoration approaches we take in this landscape is removing the juniper. If you only focused on carbon sequestration, you would say, ‘No, keep the juniper because it’s sequestering carbon.’ Yet in the long run, those sagebrush habitats are more resilient without the juniper there. In the short term, we may not be sequestering carbon, but in the long term, we’re aligning carbon sequestration activities with actual ecological site conditions. And the focus isn’t just about carbon sequestration, but also climate resiliency. Disturbance, such as natural fire, is a natural ecological process that helps ensure the landscape is resilient. While that may be a short-term release of carbon, in the long term we’re maintaining a larger carbon store because there won’t be catastrophic landscape-scale fires. In floodplains, a large flood may reset the landscape; those are all natural parts of a fluctuating system that we want to maintain from a resiliency standpoint. While carbon sequestration is important, you can’t get myopic with any of these elements of sustainability.

How was the OCAC funding distributed to ODFW?

It was a one-time appropriation. ODFW was given about $3.3 million for the projects that I described earlier. We picked five projects that will be implemented over the next three to four years, but we could have picked 50 projects because there’s a lot more work to be done. We’re hopeful that if we demonstrate

With Natural and Working Lands Funds, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife is restoring rangeland in Wasco County to create a landscape such as this found in the John Day canyon. The agency is removing invasive grasses and replanting with perennial bunchgrass species that provide habitat for wildlife species such as the short-eared owl.

success with these projects, there will be additional infusions into the Natural Climate Solutions Fund because there’s plenty of opportunity.

One of the other things the fund does is provide technical assistance to landowners. Oregon Watershed Enhancement Board, Oregon Department of Forestry, and Oregon Department of Agriculture, which all have technical assistance programs, received funding for these programs. This will really benefit landowners and provide the support that they need to do projects on their lands that are also geared toward carbon sequestration.

And also help with wildlife habitat connectivity if private landowners are adjacent to state lands.

Absolutely. We try to prioritize large landscapes or where a quilt-work of ongoing efforts could be leveraged. Additionally, we have this once in a lifetime opportunity with the Bipartisan Infrastructure legislation and the Inflation Reduction Act funds. When the Oregon Legislature gave the OCAC these funds, there was the explicit goal of leveraging the federal dollars as much as possible.

Going forward, for agency projects that will not be funded through the Natural and Working Lands Fund,

will carbon sequestration be a priority?

Where it makes sense, we will continue to prioritize carbon sequestration. Each agency has a carbon reduction plan. For ODFW, our wildlife areas and natural areas play an important role in our plan. It’s a new way of looking at work we’ve always done. In some cases where funds are more limited, we may not be able to make it a priority, but in

other cases we’ll continue to make carbon sequestration a priority. WF

Sarah Reif is the habitat division administrator for the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. In this position, she is working with partners and landowners to conserve and restore land and water in the face of a changing climate. Reif can be reached at sarah.j.reif@odfw.oregon.gov.

A New Resource to Connect Small Forestland Owners to Carbon Markets

By Jacob D. Putney, CFCarbon continues to be a frontand-center topic globally as we work to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and mitigate the effects of climate change. This is especially true within the forest sector since forested ecosystems play a crucial role in carbon cycling and storage, as well as a potential mitigation strategy. As the carbon economy continues to evolve and grow, so have the opportunities for forest landowners to participate in these markets through carbon offset projects. However, keeping up with the most current information on these projects and the associated requirements and commitments can be challenging. So, where should one start? I asked myself

the same question as I began to receive questions from interested landowners with whom I work in my extension role. As the number and frequency of these questions increased, from landowners and managers across the state, it was clear there was a need for an objective, science-based resource on forest carbon, carbon offsets, and markets.

In response, extension colleagues from Oregon State University (OSU), University of Idaho (UI), and Washington State University (WSU) recently published, Introduction to Forest Carbon, Offsets, and Markets, an 18-page Pacific Northwest Extension Publication (PNW 775). We developed this publication with the intent that it be foundational and provide a background on forest carbon, carbon terminology and processes, and an overview of forest carbon projects and carbon markets, as well as resources

Introduction to Forest Carbon, Offsets, and Markets is available within the extension catalogs at Oregon State University, University of Idaho, and Washington State University in both an online and PDF format: https:// tinyurl.com/3cttnczy.

for assistance and getting started. We initiated the development of this publication as a group project in 2021 with a small number of folks from OSU, but the project quickly grew as it gained interest from our extension forestry colleagues from neighboring land grant institutions. At that time, there weren’t any resources within our respective extension catalogs specific to forest carbon. Through a collaborative effort, we developed this resource to meet the needs of our audiences across the PNW region.

Creating a carbon-landowner focused publication

This publication is one of many outcomes that have been produced as a direct result of our Forestry & Natural Resources (FNR) Extension Program planning process. FNR agents, specialists, and coordinators from across the state gather each year to provide updates, discuss current and emerging needs, and participate in program planning. Our group planning process is a unique and long-standing tradition within FNR that allows us to use our collective efforts to address larger issues and statewide needs than would be possible individually. We discuss and consider key topics before organizing into teams to investigate them further and develop a proposal for a group project.

These group projects are intended to be a coordinated effort, with a defined outcome or output, that meets a broader need with statewide or long-term significance. We review group project proposals and collectively decide which should move forward based on available funding and amount of our time that can be committed. In 2021, we identified a resource related to forest carbon as an emerging statewide need, and this group project proposal was ultimately selected.

Our approach to writing the publication focused on achieving several objectives: identify and fill our own knowledge gaps related to forest carbon; understand the information most

Throughout the publication, text is paired with intuitive graphics that explain carbon

relevant to forestland owners, managers, natural resource professionals, and other interested audiences; and develop an introductory-level resource that would remain usable for the foreseeable future while addressing the identified, relevant, and needed information.

When we began, there were a limited number of extension-related resources available across the United Stated. We conducted a review of the current literature and outlined a draft to address key sub-topics, including forest carbon and the role of forests in the carbon cycle, measuring and quantifying carbon, forest carbon projects, project development, registries and verification, carbon markets, getting started, and where to learn more.

Throughout this process, we consulted with our stakeholders and requested “friendly” reviews to ensure the publication provided the appropriate amount of content and would be a useful tool for future readers. Additionally, we worked closely with a graphic designer to develop figures and graphics that were intuitive

and clearly demonstrate the presented concepts. After two years of drafts, reviews, and revisions, this new extension resource was published in December 2023.

Carbon will remain in our future

The carbon economy could still be considered in its early stages and will continue to evolve and grow in the coming years. This is particularly true for the voluntary market, which offers more flexibility with project requirements and commitments compared to compliance markets. Emerging carbon programs are also working to expand accessibility and reduce barriers to entry, such as up-front costs, minimum acreages, and more flexible commitments. These factors will facilitate increasing opportunities for smaller forestland owners interested in starting a forest carbon project on their property. Undoubtedly, this will generate a continued need for forest carbon knowledge and resources to inform responsible stewardship decisions. In fact, since this project began, interest

in forest carbon programs has grown almost exponentially with a multitude of programs and resources developed across a number of institutions. Clearly, the need for relevant, applicable information related to forest carbon extended far beyond the PNW, and we are excited to contribute. WF

Jacob Putney is the OSU extension forester for Baker and Grant Counties, immediate-past chair for Oregon SAF, and chair of the Blue Mountain Chapter. He can be reached at (541) 523-6418 or Jacob.putney@oregonstate.edu.

Seeking themes for 2025

This summer, the SAF NWO committee will vote on the themes for the 2025 issues of the Western Forester. If there is a topic you want to see covered next year, please send them to Andrea Watts, wattsa@forestry. org. I look forward to hearing your suggestions!

Small Landowners Are Key: An Analysis on the Pacific Northwest Carbon Market

By Midori SylwesterSmall private landowners own roughly a fifth of the forestland in Washington State, and many have indicated an interest in participating in carbon programs. Incorporating this community of individuals within carbon programs is beneficial on all fronts: programs can increase their revenue stream and small landowners can be compensated for their improved ecological forest management.

The potential for small landowners in carbon programs is not widely appreciated in the market and has resulted in a significant disconnect between the two. Nearly all the carbon programs that exist structurally exclude small landowners, defined as those who own less than 1,000 acres. Despite the Pacific Northwest containing the nation’s most productive forestland, efforts to expand carbon programs to include small landowners, which are gaining traction in other regions, have not displayed the same momentum in the Northwest. Understanding why this is occurring, and how to resolve this issue, was the focus of my capstone project with the Program on the Environment at the University of Washington.

This winter, I interned at Northwest Natural Resource Group to research what carbon programs are available to small landowners in the voluntary market, alongside pursuing my personal research on the role of communication in en-

hancing carbon program accessibility. I conducted a comprehensive literature review and interviewed 15 individuals involved in the carbon market space. These individuals included project developers and program representatives, along with small landowners who are currently enrolled in programs and those who walked away from the opportunity.

The carbon market perspective

The carbon market is inaccessible to small landowners for several reasons that include economics, methodology, and language choice. Programs currently offered to small forest landowners have requirements such as long-term contracts, property accessibility, and decreased harvesting. The most restrictive prerequisite in these programs has proven to be the acreage minimum. While interviewing one of the carbon programs available in the Pacific Northwest, I asked why their program minimum was 4,000 acres. The representative admitted that their

program believed 95 percent of projects smaller than 4,000 acres were “not viable” in their experience. In other words, the costs being poured into projects with smaller acreage were too high relative to the revenue they generated.

The availability of carbon programs relies heavily on the economics of market forces, which is also a deterrent. While the voluntary market has a higher price for carbon on average, many small landowners are not incentivized enough by the prevailing price to seek carbon opportunities due to the complexity and time-consuming nature of developing a project. Consequently, the demand for small landowner carbon programs is minimal and programs fail to develop in response.

The small pool of programs that currently exists faces significant challenges against market forces due to the program’s desire to maximize profit while simultaneously providing accessible programs. The Natural Capital Exchange (NCX) is a carbon program that attempted to address the concern of locking up land for prolonged periods of time by creating a program with 12-month contracts. NCX removed the daunting

OF MIDORI

The realm of carbon markets, as shown through a nested model, indicates carbon markets are the overarching environment in which all projects take place. Carbon programs are a division of the market that aids in developing and establishing projects with landowners. The position of landowners in the center indicates they are the sole focus of forestry carbon projects and drive the market overall.

long-term pledge to seemingly attract a larger pool of landowners but has since ceased operating in the carbon market space because its offset protocol did not win the approval of the Verra registry. Without approval, its harvest-deferral offsets were not marketable. Following my analysis of the Northwest carbon market, Forest Carbon Works has prevailed as one of the only programs available to small landowners and monopolizes the market in this region.

The

small forest landowner perspective

In numerous interviews, landowners were disappointed with the lack of support and clear direction that carbon market programs provided and wished the communication they preached was corroborated through action. Landowners often did not feel as though they fully understood the process of how their per acre price was determined or why carbon accounting took numerous trips to their property.

Why the communication disconnect?

The lack of transparency called out by landowners is due to project developers’ inability to provide a concrete estimate of income and refraining from sharing details regarding accounting methodology. An index for the price of carbon does not yet exist, which can make it increasingly difficult to give a definitive answer about income. Estimations of revenue may include characteristics that fluctuate by landowner and project depending on total acreage, growth rates, location, and current management practices, among others. The price of carbon currently sits at roughly $15-$18/ton in the California compliance market, whereas the voluntary market can present prices up to $20-$30/ton/acre for Pacific Northwest carbon projects. In contrast, the national crediting average is roughly two credits per acre. This means Pacific Northwest forests have the potential to be rewarded up to six credits per acre because of the region’s highly productive land. Carbon programs are aiming to generate profit, which can significantly impact the motivations behind project development and revenue shares, but the potential for large gains for programs can only be seized through integrating small landowners in the Pacific Northwest.

While the landowners who I interviewed had concerns regarding Forest Carbon Works’ transparency, the representative I spoke with provided unparalleled explanations for the market and program overall. The representative noted that their methodologies for pricing and carbon accounting are proprietary, but otherwise was more than willing to provide cost break-down and general support.

Though this representative was professional and pleasant during our discussion, landowner experiences provide a more accurate representation of program interaction. The disconnect between landowner conversations and my own also stems from communication: programs had the opportunity to market themselves in a positive light through my interviews, yet how these programs connect with landowners fall short of being informative or useful. Landowners who currently participate in carbon projects shared the simplicity of the enrollment process contributes to the trust they have in the program.

In sum, many challenges arise for carbon programs in wanting to address landowner needs, operate within market requisites, and generate enough revenue to maintain the program. Centralizing communication can easily fall wayside to a domain that is far too complex for a single summary. Yet, incentivizing and marketing participation can only be

done through improving the connection between programs and landowners. What’s next

While programs like Forest Carbon Works have worked well for some landowners, others are skeptical of the opportunities overall and refuse to participate unless certain milestones within the market are met. A consistently increasing carbon price or single verified carbon accounting method are specific milestones landowners mentioned they would like to see, but general suggestions regarding tackling misinformation or addressing greenwashing were also noted. The solution remains rooted in a call for carbon programs to incorporate landowner needs into program development, either through increasing the level of transparency to satisfy landowners or by performing a significant rethinking to how the market functions. Not incorporating small landowners in carbon markets creates a lost opportunity, where the potential to maximize the credits being produced by Pacific Northwest forests only occurs when the integration of this group takes place. WF

Midori Sylwester will graduate in June from the University of Washington with a degree in economics and environmental studies. She can be reached at mgs21@ uw.edu.

Improving Douglas-fir Component Biomass Estimates

By Robert SwanCarbon sequestration has become increasingly relevant in recent decades with many stakeholders wanting to increase carbon sequestration in forests to contribute to mitigation of greenhouse gas emission. This has led to analyses of carbon sequestration and cycling in forests, and often grand predictions of the amount of carbon being sequestered across forest landscapes. Due to this, prediction of biomass allocation within tree components has gained widespread attention as a method to quantify carbon sequestration within trees and forests.

However, the simple, single-predictor models of many widely used biomass equations are often insufficient to produce the resolution required for accurate estimations. Even relatively small errors accumulate rapidly when determining carbon levels across the landscape or region, which are important when reporting on a national or global scale. Therefore, increases in accuracy and precision gained by using more complex models that incorporate more variables,

such as latitude, tree height, and elevation, are especially vital and valuable for these largescale applications. The same can be said for prediction of industrially important component quantities, such as the stem of the tree, when industrial landowners estimate the biomass and timber volumes of their holdings. Small differences in expected productivity across large tracts of land may influence their decision to retain their forestland or transition the land to another use. In this way, these small gains in model accuracy and reliability may be critical for the perpetuity of working forests, especially on marginally productive land.

The right model for modern applications

Typically, models used to produce estimates for aboveground biomass of trees use diameter at breast height (DBH) as the only predictor. The appeal of using a single predictor model is the simplicity and the speed and ease with which field data may be collected, which has led to its widespread use by many forest managers.

There are drawbacks to using a single-predictor model for prediction of biomass because component biomass is very reactive to many variables. DBH-only models cannot reliably distinguish between trees of the same DBH when other landscape, stand, and/or tree-level variables differ. While DBH is indeed influenced by many of these variables, the same DBH may be reached by very different pathways, which limit its ability as a lone predictor to explain differences.

For instance, these models cannot predict the difference between stands growing on different site classes, which may reach the same DBH at much different ages and have very different morphological forms, particularly in components such as branches. These discrepancies can be substantial, and these simple models have often had their reliability for precise predictions overestimated, especially when predicting carbon across landscapes. Multi-variable models offer a way to increase the effectiveness of these predictions.

Why improve estimates for Douglasfir biomass

Douglas-fir is the dominant conifer species growing in the Pacific Northwest, both on industrial and non-industrial land, so having precise and accurate biomass estimates is crucial, whether the end goal is estimating timber volume or carbon sequestration. For my master’s research, I set out to develop multi-variable allometric models for Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii var. menziesii) growing in the coastal Pacific Northwest. While other researchers have examined biomass allocation, primary productivity, and physiological responses to assorted environmental factors, rarely has a broad array of these been examined concurrently to identify the most influential factors to individual components under broad ranging conditions.

Multi-variable models have the capacity to explain much of the influence of landscape, stand, and tree level variables on the amount and distribution of aboveground biomass in coastal Douglas-fir components throughout much of western Oregon and Washington. A drawback to these models is they are more complex and require more fieldwork. This has

accuracy was not worthwhile for the predictions that were required at the time. However, the expected precision of estimates has increased compared to past applications, especially in terms of component biomass allocation. Additionally, the predictor variables determined to be useful for aboveground component biomass prediction take minimal extra effort to assess and are already part of many contemporary forest inventory measurements. The rebalancing of this cost-benefit relationship makes these more complex models worthwhile in most modern applications.

Building the models

To build the multivariable models, 62 Douglas-fir trees throughout western Washington and Oregon were felled and their individual components measured.

For the development of these models, I used empirical data from 62 destructively sampled Douglas-fir trees grown in diverse environmental conditions in coastal Oregon and Washington State. Twelve predictor variables were used in the analyses that consisted of three levels—individual tree, stand, and landscape.

• Individual tree-level predictors were DBH, tree total height, live crown ratio, live crown length, height to live crown base, age, DBH percentile, and DBH to quadratic mean diameter ratio.

• Stand-level predictors were trees per acre and relative density.

• Landscape-level variables were latitude and elevation.

Of the models produced in this study, the multi-variable models were significantly better at explaining variation in biomass volumes than commonly used DBH-only models produced from the same data. The final models retained between two and five significant predictors, with all including DBH. Other predictors found to be significant were live crown ratio, total height, trees per acre, height to live crown base, latitude, live crown length,

and DBH to quadratic mean diameter ratio. Models were assessed for parsimony using methods such as Principal Component Analyses and Akaike Information Criterion to achieve the best cost-benefit balance. (See table 1 on page 18 for the final models.)

Many generally accepted relationships between variables and aboveground component biomass were supported by these models, such as the increase in both overall aboveground biomass and component biomass as DBH of the tree increased. Other general relationships were supported by these data, such as higher stand density decreasing biomass allocation to the crown of the tree and total biomass of the individual tree altogether. Additionally, the results suggest that certain variations in trees, stands, and landscapes may often only shift the distribution of biomass among the aboveground components of the tree, rather than causing an increase or decrease in the overall amount of aboveground biomass.

An important limitation of this study was the lack of belowground biomass measurement, soil information, and site topography, because it was beyond the scope of the study to quantitatively examine the belowground biomass of the trees and the soil and topographic features encountered throughout sampling. Many site and soil variables, such as the aspect and soil type, likely had effects upon the development of the trees sampled in this study. Additionally, many conditions such as drought and soil nutrient availability are well documented to impact the amount of carbohydrates a tree dedicates to belowground biomass, and likely had an impact upon the overall amount and

Continued on page 18

Connecting Urban Forests to the Carbon Market

By Morgan AnyaUrban forests stand at the center of carbon removal, social equity, public health, biodiversity, and positive community impacts where millions of people reside. Benefits range from cooler air in the summer to a reduction in stormwater runoff toward drainage systems during flooding events to improved health outcomes and reduced healthcare expenses.

However, as cities and urban area populations increase, municipalities are struggling to maintain existing city forests and increase urban tree canopy. A few of these challenges include pest and disease control, extreme heat, limited water, and cash-strapped city budgets. Concurrently, authors of the journal article “Declining urban and community tree cover in the United States” found that cities in the U.S. are losing more than 36,000,000 trees each year to development and projected to add 95 million acres of urban land by 2060. (https://www.fs.usda.gov/research/ treesearch/55941) It is vital to preserve some of the forested land in and around cities now, as these preserved areas could become future parks and open spaces for the public.

A conservation finance solution for cities

Urban forest carbon credits offer a new way to generate revenue while

also providing local climate action. City Forest Credits (CFC) is a national nonprofit carbon registry that solely serves the sector of carbon stored in forests and trees in metropolitan areas. CFC’s carbon crediting process offers a systems and accountability approach that ensures high-quality urban forest projects because projects must follow a rigorous set of rules outlined in the CFC Standard and Protocols and undergo a third-party verification process (https:// www.cityforestcredits.org/carboncredits/carbon-protocols/).

Entities that complete carbon projects include local governments, nonprofits, and sometimes a collaborative mix of both. Almost all the projects take place on public property or are open to the public, making these credits of genuine public interest. To enroll an urban forestry carbon project, cities work with CFC to develop a project. Documentation they must provide to demonstrate the project will generate high-value credits include a Project Design Document accompanied by supporting documentation.

CFC has protocols for either tree planting or tree preservation projects. Tree planting, also known as afforestation and reforestation, requires a 26-year commitment, and tree preservation projects require a 40- or 100-year commitment. These long-term commitments are one of many of the requirements of carbon projects that set them apart from business as usual.

The entities leading the project, also known as Project Operators, must agree

to monitor the trees over the course of the project duration, ensuring accountability and results. Project Operators sign a Project Implementation contract with CFC, committing to stewarding and protecting the trees for the life of the project. This contract may be developed in consultation with the Project Operator’s legal counsel to ensure that both parties reach a satisfactory agreement.

Each year, CFC staff require planting projects to submit a monitoring report, confirming the project is on track to deliver the expected carbon credits. Every three years, preservation projects submit a monitoring report to ensure project compliance.

The value of carbon+ credits

Each City Forest Carbon+ CreditTM includes quantified co-benefits such as stormwater reduction, air quality impacts, and energy savings, as well as reported social impacts such as social equity for under-resourced communities and physical, mental, and social health benefits. To date, CFC has issued, or will soon issue, credits to 55 projects representing an estimated $213 million in ecosystem co-benefits over 50 years.

Verified carbon offsets allow businesses to contribute to these tree projects that are making cities green, equitable, healthy, and climate-ready. The sale price of credits is determined by the buyer and the entity leading the project and depends on the market conditions at the time of sale. Credit revenue may be used for stewardship and maintenance costs, as well as help with the cost of buying future trees or land. New funding allows municipalities and nonprofit organizations to strategically increase tree canopy cover and diversify tree species to create a more resilient urban forest. Companies purchasing credits on the voluntary carbon market are willing to pay a premium due to the many benefits projects create where people live, work, and recreate.

Urban forest carbon projects are also valuable for advancing equity initiatives in cities. Entities can work with communities to design projects that strategically plant trees in historically disadvantaged communities and enroll these trees in a carbon project, thereby creating revenue

for long-term maintenance and additional planting of trees.

What’s the demand for urban forest carbon credits

The voluntary carbon market (VCM) fluctuates; credit prices rise and fall, regularly. Historically, CFC carbon credits have sold well above the average VCM $/credit value. However, worldwide demand slowed for credits in 2023. This is due in large part to a series of articles published in 2022 and 2023 criticizing offsetting and specific projects that had faulty methodologies, particularly in the global south.

It can be challenging for buyers to know which credits to buy, given the good and bad news around offsetting. Additionally, some buyers prefer to buy carbon “removal” credits, which include planting project; as trees grow, they remove carbon from the atmosphere. However, some buyers prefer preservation project credits as the carbon is already accounted for, stored in the trees and soil. Preservation credits are considered “avoidance” credits as preserving trees avoids emissions associated with development and harvest.

It is hard to know what VCM credit demand will look like in the near future though, generally, the carbon market is expected to grow in the coming years. One way confidence in the VCM is increasing is through carbon registry accreditations. CFC is endorsed by the prestigious International Carbon Reduction and Offset Alliance (ICROA), based in Geneva, Switzerland. This accreditation involved ICROA carefully assessing CFC’s Standard over multiple years and ensuring it met all requirements. There are only five Standards endorsed by ICROA in the United States. Additionally, there are carbon credit buyers that hire ratings firms to independently rate projects after they are completed.

But perhaps the most tangible way that CFC generates confidence in our carbon credits is that projects can be monitored by the public. With all these projects located on public lands, and many accessible to the public, the public can see first-hand a tree’s growth or preservation. WF

Morgan Anya is a project manager at City Forest Credits. She can be reached at morgan@cityforestcredits.org.

Carbon+ CreditsTM in Action

The Pierce Conservation District (District) is a natural resource agency working to protect and conserve the natural resources of Pierce County. Located in a major population center in central Puget Sound, the rapidly urbanizing area needs restoration to remove invasive species and replant with native trees and shrubs. Each year, the District restores approximately 100 acres of riparian habitat and plants about 20,000 trees and shrubs.

The District has completed two CFC planting carbon projects, one in 2020 and one in 2022. Both projects were riparian restoration planting projects whose goal is restoring native vegetation in floodplain habitat. Because forested riparian corridors are essential habitats for both rearing and spawning federally endangered and threatened salmon, these projects are also part of a larger effort to create barrier-free watersheds that have the conditions to sustain wild salmon by 2040.

An example of a tree preservation project is in the city of Issaquah, which leveraged verified carbon credits for over $200,000 in funding for forest conservation and stewardship. The Harvey Manning Forest is situated within the Issaquah city limits and the Greater Seattle urban growth area. The project includes 15 acres of forest on a 33.5-acre property. The 100-year-old forest consists of a mixture of coniferous and deciduous trees, including Douglas-fir and bigleaf maple, with riparian and wetland habitat supporting wildlife corridors on Cougar Mountain.

The forest was threatened by conversion into a 57-lot residential development. By protecting this forest, the city expanded a large, forested corridor on Cougar Mountain that affords benefits for both people and the environment. The expanded park increases recreational opportunities for residents, creates contiguous wildlife habitat, and protects waterways that feed into salmon-bearing streams. Revenue from the credit sales is used to support stewardship activities such as the Green Issaquah Program, which promotes forest health by removing invasive plants and restoring understory. In protecting this site, the city took a regional leadership role, generating a great deal of goodwill from both the community and partner agencies. Protecting this area, in part through carbon crediting, was also a celebration of and in alignment with, the city’s recently launched Climate Action Plan.

To see full project documentation packages, view projects on the CFC Carbon Registry page (https://www.cityforestcredits.org/carbon-credits/carbon-registry).

The Lay of the Land: Carbon in the Last Frontier

By John “Chris” Maisch, CF and Nathan Lojewski, CFAlaska is a big place with a history of resource development on a grand scale. The early gold rush days produced abundant stories of risk taking and success or failure of the prospectors who flooded into the territory. Robert Service’s famous tale, “The Cremation of Sam McGee” in the book Songs of the Sourdough, which was published in1907, captures the drama and risks faced by those seeking riches and adventure in this new frontier. Over 50 years later, the next “big strike” for resource development in the recently recognized state of Alaska was oil; the value of this oil was best captured in the catchy theme song of “The Beverly Hillbillies.”

will the next natural resources stampede unfold as this rush moves through the landscape of the Great Land?

Monetizing Alaska’s carbon

As foresters and natural resource managers, we are faced with responsibility and opportunity while we try to unravel and understand the science and mechanisms of how this new land management tool works, or in some cases may not work, as intended. There is hyperbole in abundance and agendas that are well intentioned, but the global and national risks we face with climate leave little room for failure.

IFM protocol. The projects have 40-year terms and were certified by the American Carbon Registry (ACR).

Both these events had profound impacts on the people, culture, wildlife, and landscapes that continue to shape our thinking and actions as a society and as natural resource managers. In the rush to monetize carbon management, how

The carbon “rush” in Alaska began slowly, but after several early adopters made their first strikes of green gold (sales), the pace and scale of projects accelerated. The voluntary systems were first active in 2006 when a project of 8,200 acres was completed on Afognak Island. The Afognak Forest Carbon project was an Improved Forest Management (IFM) project certified under the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS). Since this initial project, there have been numerous projects across the state, almost all tied to Alaska Native Corporations (ANC) at the regional or village levels. Doyon Ltd. a regional ANC, is a recent participant and through two separate projects in Interior Alaska contributes 376,248 acres using an

The first forestry projects developed under the California Air Resources Board (CARB) regulatory cap and trade program were in southeast and south-central Alaska. In 2018, the regional Alaska Native Corporation Sealaska committed 165,000 acres of their lands to a forestry offset program for a 100-year term. To the north, the regional ANC Ahtna, Inc. completed a CARB offset project that committed approximately 500,000 acres, which generated 14.8 million credits. From 2015-2019 approximately $370 million has been generated in sales and these Alaska-based projects have become the number one source for forestry offset projects utilizing the CARB registry. Projects in the states of California and Washington ranked number two and three, respectively.

Standing on the sidelines and seeing all this activity, the state of Alaska decided to participate in the carbon rush but first needed legislation to authorize and regulate the process on state land. Governor Dunleavy introduced legislation in the 2023 legislative session that became Senate Bill 48. This bill moved rapidly through the legislative process and was signed into law on May 23, 2023. It gives the “state authority to develop carbon management projects on state lands and sell carbon offset credits and to lease state lands for carbon management purposes.” The regulation package in support of the legislation was released on March 28, 2024, and was open for public comment for 30 days. Once the process is completed, expect a renewed push by numerous parties to develop projects.

Keeping carbon in place

While there is much focus on storing carbon, there is a growing awareness of the need to counter carbon’s release. There are numerous ways that carbon is emitted to the atmosphere, one of which is wildfire.

Alaska has a unique approach to its fire management plan; there are several options for fire protection based on the identified values at risk. The primary values are “life” and “property” with recognition of other values that provide fire

managers guidelines for consideration. The plan has four fire management options: critical (suppress); full (suppress); modified (treat as full during high fire danger or treat as limited after summer rains have arrived); and limited (monitor, then suppress or undertake local site protection when values on the landscape are threatened). These options, especially the limited, were developed in the early 1980s and recognized the role wildfire has in the boreal forest. Climate considerations were not recognized as a value, as the topic was not a concern at the time. As the amount of fire increased on the landscape, some managers began to rethink the relationship between climate and wildfire.

The majority of wildfires in Alaska are caused by lightning and the amount of fire on the landscape has increased dramatically over the past two decades. In 2004 and 2005, over 11.2 million acres burned in the state, primarily in the boreal forest regions. In 2015, approximately 5.1 million acres burned, which was more than half of the 10.1 million acres that burned in the rest of the United States—a record year. In 2023 Canada saw a jaw-dropping 45.7 million acres burn, again a record and primarily in the Arctic and boreal regions.

Scientists were also taking notice due to the intersection of fire and permafrost that underlay much of these regions. (Permafrost is defined as any ground that remains completely frozen at 32oF for

While writing this article,

Wildlife Service in the Yukon Flats Wildlife Refuge decided they wanted to implement a demonstration project to protect Yedoma from wildfire to slow emissions from this source. In 2023 they changed the fire management option from limited to modified protection for specific locations. No ignitions occurred in these areas last year, but the concept will be tested and may be more widely adopted moving forward.

Is there more we can do to reduce or avoid these emissions for a period of time? The concept is challenging, but a group of partners that include landowners, scientists, Alaska Tribes and Native Corporations, suppression agencies, land managers and communities are discussing ideas. Acting as a convener, the Alaska Venture Fund (AVF) is assisting this broader community with a dialogue that could result in a mitigation program. In the carbon trading world, this would be

Maisch visited the University of Alaska and met with Dr. Go Iwahana and other scientists working at the International Arctic Research Center. He had the opportunity to hold a frozen core of Yedoma. Visible are the many small bubbles of very old greenhouse gases that were trapped when the permafrost formed. These greenhouse gases will be released if the area burns and subsequent thawing occurs.

at least two years straight and as long as tens of thousands of years.) Some of the oldest permafrost is 10,000 years old and is called Yedoma. This permafrost is very ice rich, sometimes 80 percent ice.

The amount of greenhouse gases (GHGs) contained in the permafrost is enormous and far greater than the direct emissions by wildfires as they burn. The subsequent thaw and degradation of the permafrost soils release methane and other GHGs long after the fire is out. With so much fire on the landscape, this is cause for concern. Early climate models, which are still in use, often treated the Arctic and near Arctic region as large carbon sinks, capable of storing carbon for very long timeframes.

Managers with the U.S. Fish and

known as an ex-ante event or an avoided emission. Stand by for developments over the next year. The carbon rush is on, and the mitigation of climate change is to the benefit of all. Let’s hope it succeeds. WF

John “Chris” Maisch, CF, served 15 years as the state forester and director of the Alaska Division of Forestry and Wildfire Protection until his retirement in 2021. In 2022, he was the president of the Society of American Foresters Board of Directors. Maisch can be reached at maisch@acsalaska.net. Nathan Lojewski, CF, is the forestry manager for the Chugachmiut and chair-elect for AKSAF. He can be reached at Nathan@ Chugachmiut.org.

Improving Douglas-fir Component Biomass Estimates

Continued from page 13

distribution of biomass among the various aboveground components as well.

es, to improve habitat for sensitive or endangered species. Carbon credits are an emerging income source in which accurate predictions of carbon, and the effects of management decisions on carbon, are paramount to the stability and

We Remember

The values in parentheses indicates the standard error of the coefficient.

* The values followed by this symbol are multiplied by the natural log of the predictor.

° The values followed by this symbol are multiplied by the square root of the predictor.

Exploring the Potential Effects of an Expanding Forest Carbon Market on Working

Forests and Communities in the United States

Continued from page 5

narrowly on removal and storage of carbon in forests, at risk of losing sight of interrelated social and ecological values. Understanding where there is flexibility in management strategies to accommodate multiple values is critical for achieving comprehensive objectives and avoiding unintended negative impacts. Thoughtful, informed, and consultative assessments are needed to determine if and where regulation is most appropriate, where markets provide the best approach, and how to integrate both strategies in a practical way while protecting individual rights and freedoms. Stakeholders should be aware of potential downstream impacts of a growing market for forest carbon offsets and take practical measures to plan and adapt to

a changing climate and socio-economic dynamics. With increased emphasis on building a more comprehensive understanding of potential downstream impacts, there is potential for development of integrated, multi-dimensional strategies that balance climate change objectives with social and ecological values.

This article is based upon Concept Paper: Exploring the Potential Effects of an Expanding Forest Carbon Market on Working Forests and Communities in the United States. The concept paper is available at https://www.dovetailinc.org/ upload/tmp/1703195421.pdf. WF

Dave Bubser is a principal with Cambium Consulting. He can be reached at dave@consultcambium.com. SAF member Kathryn Fernholz is the president, CEO of Dovetail Partners and can be reached at katie@dovetailinc.org. Eliza Meyer is a project director with Dovetail Partners and can be reached at eliza@dovetailinc.org.

At the workshop, presenters and participants will further explore the current state of forest carbon markets in the United States, what is working well for forests and people, and what changes are needed to ensure all forest products, services, and values continue to be available for current and future generations.

To learn more about the workshop, visit Dovetail Partners https://dovetailinc. org/index.php.

Calendar of Events

2024 Northwest Scientific Association Annual Meeting, May 20-23, Gonzaga University, Spokane, WA. Contact: www. northwestscience.org.

Washington Hardwoods Commission 2024 Annual Symposium, June 6, Chehalis, WA. Contact: wahardwoodscomm.com.

SFI 2024 Annual Conference, June 4-7, 2024, Atlanta, GA. Contact: https://forests. org/conference/.

Comprehensive Environmental Sampling; Methodology, Practice, and Analysis, June 11-12, Live Remote Attendance. Contact: NWETC.

Western Mensurationists 2024 Meeting, June 16-18, Tahoe, CA. Contact: https://mensurationist.net/2024-westernmensurationists-meeting/.

CESCL: Certified Erosion and Sediment Control Lead Training, July 10-11, Live Remote Attendance. Contact: NWETC.

2024 SAF National Convention, Sept. 1720, Loveland, CO. Contact: www.eforester. org/SAFConvention.

CANOPY: Forests + Markets + Society (formerly Who Will Own the Forest?), Sept. 24-26, Portland, OR. Contact: worldforestry.org/canopy.

2024 Scaling for Non-Scalers, Oct. 10, Wilsonville, OR. Contact: WFCA.

Contact Information

NWETC: Northwest Environmental Training Center, 1445 NW Mall St., Suite 4, Issaquah, WA 98027, 425-270-3274, nwetc.org.

WFCA: Western Forestry and Conservation Association, 4033 SW Canyon Rd., Portland, OR 97221, 503226-4562, nicole@westernforestry.org, westernforestry.org.

Send calendar items to the editor at wattsa@forestry.org

Incorporating Biochar into Forest Management Practices to Deliver Carbon Benefits

By Derek PiersonFhave shown that biochar in the soil can persist for millennia, offering a long-term pathway for carbon sequestration. Carbon storage improved through forest management

orests play a critical role in regulating global levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide. The carbon that trees absorb from the atmosphere provides the backbone for plant tissues, such as wood, leaves, roots, etc. However, as a fundamental part of the carbon cycle, when a tree or branch falls in the forest, the stored carbon is released back to the atmosphere through decomposition. Depending on the size and type of biomass, as well as climate, this decomposition process can take weeks to centuries. For common forms of woody slash, much of the stored carbon returns to the atmosphere in less than 10 years. This decadal timescale for decomposition may seem like an opportunity to bolster carbon storage. However, this timescale is still far too short to support our need for a sustained drawdown of atmospheric carbon.

Additionally, common forest management practices, like harvest and thinning, generate scattered branches, twigs, and leaves; often referred to as slash. On any drive through your local forest, you’re likely to come across a slash pile or two,

or two hundred. Traditionally, this slash is viewed as a waste product, with no cost-effective use. As such, standard practice for removing this waste material is to simply pile it up and burn it. Yet, burning slash piles has many drawbacks, including the risk of fire, long-term soil damage and poor effects on air quality.

Further, pile burning is not climate smart. When burned, carbon stored in the biomass is sent into the atmosphere, in the form of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. Alternatives to pile burning are few, and fewer still are cost effective. However, with advances in technology and growing emphasis on sustainable, climate-smart forestry practices, a solution with wide ranging benefits has entered the conversation—biochar.

Since biochar has been covered in earlier issues of the Western Forester, most recently “Finally, a Market for Slash” in the Jan/Feb/March 2022 issue, I’ll only give a high-level detail of what biochar is. Biochar is a charcoal-like substance created by heating organic matter in an oxygen-limited environment. This process, known as pyrolysis, roasts the organic material, but stops short of complete combustion. The result is a stable, carbon-rich material with tremendous pore space and surface reactivity-good properties for soil water retention and remediation. Further, with a high carbon content (~80 percent), biochar has the unique potential to sequester carbon while simultaneously improving soil health.

The time required for the decomposition of biochar is on the scale of hundreds to thousands of years. Due to the low nutrient content and durable structure of biochar, decomposers in the soil, like fungi and bacteria, have a hard time breaking it down. Indeed, studies

Forest management offers a diverse toolkit for delivering carbon benefits, with biochar fitting in as a cornerstone in combination with other climate-smart practices. For example, selective thinning can help promote healthier stands that capture more carbon while reducing fire risk. In turn, this generates more merchantable timber, which when used sustainably, can also serve as a long-term carbon store, further offsetting emissions. Additionally, forests can be strategically managed to promote reforestation and afforestation efforts, expanding overall carbon sequestration potential.

Biochar complements these approaches by transforming the slash leftover from all these practices into a long-term carbon store. Together, these types of adjacent management practices form the foundation of climate-smart forestry, offering a multifaceted approach to help mitigate climate change.