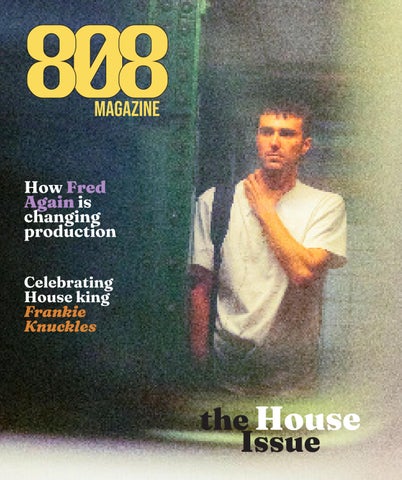

How Fred Again is changing production

To me, one of the biggest pleasures in life is sharing music with the people we love—because why would we keep these beautiful secrets hidden? Music allows us to transcend; to connect; and most importantly, to love. And that is why I find writing about it so imporant to understnading ourselves and those we share space with. My intent with this issue was to spread awareness to the public about a genre of music that I deeply adore, yet is widly overrated. When they say house is a feeling, they mean it. It allows us to garner strneegth and proceed with life with ecstacy and comapssion—I mean who doesn’t want that?

It’s important to highlight the people that make house, house. From Barbara Tucker to an engaging conversation with the late Frankie Knuckles, a key adapter in the genre. Modern day legends like Fred Again even prove that house can be in combination with other genres.

What I hope you find is a deep exploration of the history and the present—and perhaps your thrist to create your own.

Front Cover

https://www.nytimes. com/2022/10/26/arts/music/fredagain-actual-life.html

https://www.beatportal.com/ feed-beatportal/how-to-get-started-djing-how-and-what-tow-play/ https://pitchfork.com/features/ lists-and-guides/the-best-housetracks-of-the-90s/

https://www.theguardian. com/music/2014/mar/06/roland-tr-808-drum-machine-revolutionised-music

https://www.nytimes. com/2022/10/26/arts/music/fredagain-actual-life.html

https://www.harpersbazaar. com/culture/art-books-music/ a40473664/house-music-is-backlets-remember-its-roots/

https://daily.redbullmusicacademy.com/2018/02/frankie-knuckles-1995-interview

https://www.nytimes. com/2022/10/26/arts/music/fredagain-actual-life.html

https://the-gist.org/2018/10/whydoes-house-music-feel-so-damngood/

https://www.dazeddigital.com/music/article/30445/1/why-modernrave-culture-isn-t-dead-yet https://i-d.vice.com/en/arti cle/43vaqm/how-boiler-roomworks

https://www.vice.com/en/article/ez3mj4/cheeky-house-feature-naughty-outrageous

https://www.behance.net/ gallery/154102423/HeinekenRefresh-Your-Music-RefreshYour-Nights?tracking_source=search_projects%7Cdj

https://www.southeast15.com/ peckhamandnunheadblog/music-spotlight-dj-little-missions

https://www.behance.net/ gallery/154102423/HeinekenRefresh-Your-Music-RefreshYour-Nights?tracking_source=search_projects%7Cdj Images https://www.complex.com/music/ house-music-history (infographic) https://southsideweekly.com/ frankie-knuckles-liberatory-space/ https://www.soundonsound.com/ people/fred-gibson-aka-fred-again https://www.songkick.com/artists/10060749-fred-again https://edm.com/features/whyfred-again-is-exactly-what-electronic-dance-music-needed https://boilerroom.tv/ https://www.highsnobiety.com/p/ fred-again-highsnobiety-soundsystem/

Do you want to become a DJ, but aren’t sure where to start? Do you want to learn how to mix songs, but don’t know where to buy them or what equipment to use?

This starter guide will help you with your initial steps, and should answer some burning questions you may have have when it comes to getting started with DJing.

start playing straight away, picking up skills, techniques, and styles as you progress.

Not only that, but the costs required nowadays are far much lower than they used to be. Whether you’re looking to start out by using CDJs, playing with controllers, or just playing with DJing software, the setup costs now make it possible for anyone to DJ.

Illustration ByBehanceStarting out as a DJ has never been easier. The ability to access controllers, decks, and a near-unlimited amount of music means you can

The introduction of Beatport LINK has also made the jump into becoming a DJ more effortless. To become a digital DJ, you no longer need

to rely on downloadable music or downloading MP3s. With Beatport LINK you have access to millions of songs in all kinds of styles at your fingertips.

With the right setup, a bit of practice, some confidence, and of course the right music (and global health situation) you could find yourself playing at your favorite next party.

But before you ask yourself questions like how to beat match, or even — if you’re getting ahead of yourself — how to stream your DJ sets, you first need to decide on what tools you want to use as a DJ.

In the end, it is the music you play that defines who as a DJ. But to get behind the booth you need to find the right controllers, turntables, or decks that fit your style.

The first thing you’ll want to consider is whether you want to DJ with or without a laptop, tablet, or smartphone.

Traditionally, the classic setup — playing with two turntables and a mixer — is a good option. But unless you use this setup with a digital vinyl system (we’ll get to that later), you’re limiting the amount of tracks you have at your fingertips to what is available on vinyl. Thus, by using a laptop, or an app with an in-builtstreaming system, you allow yourself access to a far greater palette of music. This setup can also be prohibitively expensive, if cost is a consideration.

All of this begs the question: which DJ software is best for you?

DJing digitally allows you to get a handle on the fundamentals of playing. Whether you’re using VirtualDJ, Serato, rekordbox, or any other favored DJing software, you’ll be able to interact with the basic properties that will allow you to mix two (or more) tracks together. By cueing up tracks, looking at their waveform properties, creating loops, mixing your tracks together, and then

playing with effects, you can start to properly understand how DJing works.

You’re not just limited to using a laptop either, with the majority of DJing platforms available as downloadable apps, some of which are even free of charge.

Starting off with djay / djay PRO by algoriddim, for example, is a great introductory tool to get started with DJing. With a free version that works on all devices and operating systems, you can experiment with waveforms, mixing, loops, and more. What’s more, the PRO version is compatible with multiple streaming services, including Beatport LINK, which allows you to integrate a near-infinite amount

PRO version is also compatible with multiple controllers, allowing you to physically control the music you’re playing.

You don’t actually need anything more than DJing software in order to start playing. But for maximum impact, you will want to look at adding a controller to your setup.

Controllers don’t just allow you to better interact with your music, they also give you the most satisfaction by allowing you to get a real handson experience.

Essentially, controllers are reproductions of traditional DJ setups, designed to be more transportable, easier to use, and with more upto-date features that allow you to be more creative with your mixing. They are also often less expensive than traditional setups.

Controllers come in all shapes and sizes and are made by various brands, but most will come with the same functions: jog wheels, mixers, and pitch control. Most importantly though, controllers nowadays come

your laptop, mixer, or soundsystem without having to invest in a separate system.

Whichever controller you use, make sure it’s compatible with the DJing software you’ve selected to work with.

For the more adventurous DJ, it’s recommended to start out with more professional hardware, CDJs. With CDJs, you get the full tactical experience of playing digital music with that tactile feel, allowing you to speed up, spin, or stop the music without pressing any buttons.

The most popular CDJs on the market are made by Pioneer DJ and Denon.

Newbies need not fear. Many systems are tailored such that they can be used by pros and beginners alike, designed with sync functionality and large screen displays that allow you to easily browse, cue, loop, and much more.

If you’re a regular viewer on streaming platforms such as Beatport Live, then you’ll notice that the

majority of professionals are DJing with USBs, often using the Pioneer CDJ-2000. Pioneer have become the industry standard when it comes to CDJs, such that they are found behind the booths at many clubs across the world. If you want to be a DJ that can play anywhere, then learning how to play with CDJs will be a massive bonus in the long run. You can access a near-infinite amount of tracks using CDJs as well. Both Pioneer and Denon use library software systems, in which you can access your entire music library.

By using management tools, you can tag, file, and find your tracks with the greatest of ease. Not only that, but both systems employed by Pioneer and Denon are compatible with streaming services like Beatport LINK, so you can integrate Beatport’s vast library of electronic music into your set wherever you are.

Denon DJ even has Beatport LINK integrated directly into the players,

so that no laptop is required to access the complete Beatport catalog.

The final thing that we didn’t fully mention yet is digital vinyl systems (DVS).

These are the tools that allow you to control turntables through a digital medium, made popular through DJs who use Serato. This is when you see a DJ, like Jazzy Jeff, or DJ Marky for instance, controlling a turntable or CDJ through a timecode vinyl, or CD. As Beatport LINK is fully integrated into Serato, that means you can have the near-infinite Beatport catalog at your fingertips, controlling the music and the selection at your will.

Having looked at all the options available to you as a DJ, from ones that fit in your pocket to the ones behind the booth, the next step you need to take is finding your music.

Remember, music is the special sauce behind any DJ set.

From its 1980s roots in Black, Latinx, and queer communities in cities like Chicago, Detroit, and New York, electronic dance music exploded in the 1990s, taking techno, rave, jungle, and other permutations around the globe. But nothing better exemplifies ’90s dance music than house, whose pumping groove supplies the heartbeat of club culture.

It was everywhere—both the dominant force in the underground and the sound du jour at the top of the charts. And it morphed as it spread, spinning off innumerable styles. There was deep house, cued to dusky moods and soulful expression; gospel house, pairing dancefloor deliverance with spiritual union; minimal house, blippy and lithe—and that’s just to name a few. House could be lean and tracky or carefully arranged, hell-bent for leather or in love with the drift.

The following list, presented in alphabetical order by artist, includes house tracks featured on our 250 Best Songs of the ’90s, as well as ones that didn’t make that tally but are still crucial to the genre. These are the cuts that best defined ’90s house—the ones that changed dance music forever, and keep us moving today.

Barbara Tucker: “Beautiful People (Underground Network Mix)”

Produced by Masters at Work, “Beautiful People” combines songwriting in the lineage of disco legends Gamble and Huff with the cutting edge of ’90s house. The 1994 single topped the Billboard Hot Dance Club Songs chart and will forever be remembered for Barbara Tucker’s vocal, which was sampled by Masters at Work’s Louie Vega

under his Hardrive alias and subsequently used by Kanye West on 2016’s “Fade.”

But there is so much more to the song than one (admittedly powerful) line, as Tucker’s sassy, yearning delivery rides a wave of jazzy chord changes, exquisite high notes, and back-to-church organs. She’s got one of the most recognizable voices in house music: Its soulful tones, immaculate control, and hint of unspecified naughtiness are enough to draw the most introverted wallflower onto the floor. Working under his Hardrive alias, Masters at Work’s Louie Vega would end up zooming in on two particularly potent bars of Tucker’s performance to create the equally iconic hit “Deep Inside,” a sleeker, trackier 1993 cut—released a few months before Tucker’s single—that would go on to be sampled by DJ Rashad. –Ben Cardew

Though they would go on to make much bigger hits like “Red Alert” and “Where’s Your Head At,” nothing quite captures Basement Jaxx in heads-down dancefloor mode like “Fly Life.” Released amid a run of club-focused EPs the UK duo turned out in the five years before their 1999 debut album, it’s a tough, insistent slice of sample-heavy disco house in the vein of DJ Sneak’s “U Can’t Hide From Your Bud”; it stands out from the pack by virtue of its relentless stabs and a hair-raising vocal line that stretches wordless melisma into psychedelic curlicues. The “Brix Mix,” meanwhile, threw a gruff ragga vocal into the stew, proving house music’s adaptability, and signaling Basement Jaxx’s own imminent post-genre future. –Philip Sherburne

pared to the harmonic range of most of their soul-, jazz-, and gospel-tinged productions—their 1990 debut LP, in fact, came out on Motown—the 1996 single employs little more than a fistful of chords arrayed around a driving house groove. But what chords! Filtered this way and that, morphing between strings, Rhodes, and synths, they move like mercury and glisten like opal; Steve Reich himself couldn’t have envisioned a more enveloping matrix of pulses.

Blaze: “Lovelee Dae” (1996)

“Lovelee Dae” is an outlier in New Jersey duo Blaze’s catalog. Com-

That intensity of focus resonated far outside the tri-state area’s soulful-house scene: In 1997, house innovators Derrick Carter and Luke

By Weronika Durachta

By Weronika Durachta

Solomon released the track on their Classic label in the UK, and the following year Germany’s Playhouse got in on the action. Remixes proliferated, with Carl Craig, Roman Flügel, Isolée, Kompakt’s Michael Mayer and Tobias Thomas, and many others distilling the song into increasingly high-proof doses of minimalism. But it’s that soaring vocal refrain—“It’s a lovely day/ And the sun is shining”—that makes it the most guilelessly optimistic day-brightener in the deep-house canon. –Philip Sherburne

Cajmere: “Brighter Days” [ft. Dajae] (1992)

Curtis Alan Jones brought a Jekylland-Hyde dichotomy to Chicago house music. As Green Velvet, he reveled in dark-side thrills on songs like “The Stalker,” “Answering Machine,” and “La La Land”; as Cajmere, he explored sweeter, more wholesome vibes. (One major exception: Cajmere’s 1992 anthem “Percolator,” a tweaked-out descent into chants and squeals that was recently sampled on City Girls’ “Twerkulator,” could easily have come from his angstier alter ego.) Cajmere’s most upbeat moment remains 1992’s “Brighter Days,” in which Chicago singer Dajae offers a message of uplift in the simplest of terms over sprightly drums and organ stabs; it’s as carefree a song as house music has ever produced. DJ Rashad and DJ Spinn sampled the vocal on their 2013 track “Brighter Dayz,” flipping Dajae’s coolly optimistic hook into a more contorted figure, suggesting the way hopes harden over time. –Philip Sherburne

Crystal Waters: “Gypsy Woman (She’s Homeless)” (1991)

As in New York, Newark, and Atlanta, the underground club scene in Baltimore was intimate. With Crystal Waters’ “Gypsy Woman (She’s Homeless),” respected local DJs and producers the Basement Boys were able to transpose the sybaritic vibe

of local hot spots like the Black Box to similar musical sanctuaries for Black and gay youth outside Maryland. Their instantly memorable, organ-driven rhythm track combined with Waters’ distinctive, jazz-influenced vocals to create a perfect peak-hour club record. Dancing to serious subject matter is a form of exorcism in house music—and the opening bars of “Gypsy Woman” sent the denizens of New York City’s most influential nightclubs running for the dancefloor. –Carol Cooper

March 6, 2014

March 6, 2014

The congas ring cheekily, the cowbell plays a corroded chime, the snare is parched and cruel –and the bass drum, a hard bloom of air, is barely music at all. With these core sounds, abetted by a handful of others, a simple drum machine gave house, techno and hip-hop the language it still speaks today.

The Roland TR-808 went out of production in 1983, even as the music that depended on it was being formed. Now Roland has resurrected it as the TR-8. The new model features all the sounds of the original as well as those of its successor, the TR-909 (there is also a relaunched version of the TB-303, the imitation bass guitar that acid house producers used to produce disturbing, squelching undulations). The 909 certainly left its mark, its hihats becoming one of the hallmarks of techno›s froideur, but it›s the 808

that remains the most iconic and influential.

Until the 808 became available in 1980, drum machines were something you put on top of a living-room organ to play along in time with. “Suddenly there was a move to make rhythm machines that could be used in the professional market, to break away from this preset bossa nova thing,” says Sean Montgomery, a product manager at Roland. Roland aimed to recreate actual drum sounds, but the 808’s drum sounds, created by running an electrical current through transistors, sounded very little like the real thing. “They did it the best they could with the analogue technology, and it sounded shit,” says Montgomery with admirable frankness. The 808 went into commercial freefall.

But with units at low prices, relatively cash-strapped producers picked them up, and here the legend begins. Detroit techno producer Juan Atkins bought “the first 808 in

Michigan” when he was still in high school, using it for his band Cybotron. “I had a class called Future Studies, about the transition from an industrial society to a technological society,” he says. “I just applied a lot of those principles to my music-making.” The 808 was the perfect tool for his future music, a “hi-tech funk” inspired equally by Kraftwerk and George Clinton, and was a cut above the primitive DR-55 drum machine he’d previously had. “The 808 allowed you to actually build your own patterns – you were able to put the kick drums and snares where you wanted them. It opened up a lot of creativity.”

Meanwhile, in New York, Afrika Bambaataa and the Soul Sonic Force had recorded their 1982 hiphop track Planet Rock, giving the nascent style a bright shaft of daylight between it and the funk that had come before. Greg Broussard, a producer in Los Angeles calling The Egyptian Lover, found out that it was the 808 that gave the track its distinct character and went to play with it at a local music store. “I programmed the Planet Rock beat and fell in love with this machine,” he remembers dewily. “It blew me away. Everything sounded a bit toy-like, but at the same time it made you want to dance. I bought it right there on the spot.” After a selftaught crash course, he played it live the next day in front of 10,000 people in a sports arena with his Uncle Jamm’s Army DJ crew. “I didn’t have any other instruments – the beat was moving the whole crowd. Thousands of people were dancing to this one little drum machine.” Over in Detroit, Atkins was also feeding it into his sideline as a DJ. “We just took an 808 to the party, and made rhythm tracks on the fly – the place

“TheLeft Illustration by Weronika Durachta

went crazy. It was something fresh, more than just playing a record.”

It struck a chord as an instrument that truly reflected the 80s. “Home computers were coming on the scene, and it just fitted in with that,” says Joe Mansfield, a drum machine collector who wrote this year’s pictorial history Beat Box: A Drum Machine Obsession. “It sounded futuristic, what you thought a computer would sound like if it could play the drums.” It began to seep into the mainstream, as the backbeat to Marvin Gaye’s Sexual Healing, and across the Atlantic to the UK into, firstly, the industrial and postpunk scenes, where Graham Massey of Manchester acid house act 808 State first encountered it.

“It had that industrial heritage, but had that soul heritage,” he says. “The Roland gear began to be a kind of Esperanto in music. The whole world began to be less separated through this technology, and there was a classiness to it – you could transcend your provincial music with this equipment.” Massey made hip-hop with the 808, and then, because he couldn’t afford anything else, used it for house too, making “dense, jungle-like” tracks that also deployed the 909. “On the 909 the kick was a bit more in your chest, a bit more of an aggressive drum machine. The 808 almost seems feminine next to it … the cowbell on the 808, that’s the thing that says mid-80s R&B to me – SOS Band, big dancefloor anthems, which were a massive thing in the north-west of England. It wasn’t just nerdy DJ culture, it was a ‘ladies’ night’ kind of music.”

The sounds became so much a part of dance music – where very often drums still don’t sound like drums –that it’s continued to endure, helped along by the digital versions made for production software. “Producers are searching through kits of

tens of thousands of drum sounds and always coming back to the 808,” says Mansfield. “It’s embedded, it’s constant.” Hip-hop has continued to use it, with producers such as Lex Luger building intimidating 808 minimalism, and the juke artists of Chicago tapping its basic palette for their frenetically paced dance workouts.

These were heard by dubstep producer Tony Williams, inspiring his current Addison Groove project, which is based around the 808. «If you layer its bass drum, clap and snare on top of each other, it fills up such a specific but perfect frequency range that it sounds great in a club, at home, even on laptop speakers,» he says. Previously using a software version, he bought an actual 808 instead of buying a new car when superclub Fabric asked him to play a live set with one. “I shouldn’t really say this, but they’ve made it really easy to play live when you’re drunk,” he says in a languorous Bristolian drawl. “The sound palette is one of the best that’s ever existed – whatever you do is probably going to make people dance. And I really enjoy that, because I like a drink.”

The new incarnations are designed to continue this live heritage, as more producers gravitate from laptops towards the improvisatory potential of hardware. They’re unlikely to entirely replace the original, though, with their pungent whiff of madeleine; Broussard, AKA, The Egyptian Lover, has now hoarded six 808s, and his voice turns soft and fond when he talks about them. “These machines are like my children – I could never get rid of them.”

Addison Groove›s album Presents James Grieve is released on February 28 by 50Weapons. The Egyptian Lover realeases an anthology later this year by Stone’s Throw Records. Juan Atkins plays London’s Village Underground on March 8.

.

By Lynnee Denise June 30th, 2022

First things first, house music is Black queer music. A vehicle used to transcend earthly troubles and a soundtrack for the disappearing of bodies on dance floors snatched up by the AIDS virus. Music found at weekly parties and weekly funerals. Contemporary Negro spirituals. The ballroom culture surrounding house music provided a sanctuary for people who were kicked out of their homes, shamed into silence, and at times shunned by churches, mosques, and cathedrals. House music spoke to “the children” who, when expelled

from their biological families for being gay, found protection and belonging with chosen families. They formed queer kinships with parental figures in places like New York City, Detroit, D.C., Baltimore, and Philadelphia. So, when Mr. Fingers penned and produced one of the first of many house anthems asking the question “Can You Feel It?” it was far from rhetorical. And when Marshall Jefferson ordered people to “Move Your Body” in his equally epic anthem, it was a rhythm directive. DJs and house music producers, some queer and some straight,

were calling on witnesses of the AIDS crisis to grieve and groove. I coined the term DJ scholarship in 2013 to explore the Black queer roots of house music. My curiosity about house feels like a form of respect, a living altar I create every time I compose a house mix. Yet never before in my three decades as a DJ have I experienced it being part of such a fiery national dialogue. Within one week, Beyoncé released a new single featuring Big Freedia, and Drake dropped a new house-inflected album featuring South African house music producer Black

Coffee. This unexpected turn of events opened up larger questions about commercial vs. underground culture, racism and sexism, and ownership and authenticity. But where does the story of house music begin? Given the varying factors involved with its formation, the story is by no means linear. I’ll share one of them.

In the 1970s, Chicago promoter Robert Williams recruited the legendary Bronx-born Frankie Knuckles to start a club called the Warehouse in Chicago for predominantly Black gay men. But Knuckles wasn’t

the first choice. Williams wanted DJ Larry Levan, a magical music conductor, producer, and thought leader in designing one of the most pristine sound systems in New York City. Levan was the minister of music for the predominantly Black and Brown gay patrons at the famous membership-based Paradise Garage club. Williams traveled from Chicago frequently to hear him spin. And Williams wasn’t the only supporter of Levan’s willing to travel. Among the thousands of attendees who danced at the Paradise Garage between 1976 and 1987, you could find Eartha Kitt, Madonna, Basquiat, Keith Haring, and Grace Jones partying with the same fierce focus. Still, Levan passed on the opportunity to leave the Paradise Garage for Chicago. Instead, Frankie Knuckles accepted the offer and left New York City in the late ’70s. Shortly after, he became the official resident DJ for Robert Williams’s Warehouse parties.

While locating the origin of any genre of music is slippery and complex, plenty of evidence suggests that the early-1980s underground club scene in Chicago is where the term house found a home. Frankie Knuckles, who was eventually crowned the Godfather of House Music, recalled seeing the term in a record store window for the first time between 1980 and 1981. Incidentally, around the same time, the first AIDS cases were reported in Los Angeles in five young gay men. When Knuckles asked a friend from Chicago what house music meant, the friend explained how the record store was advertising music that could be heard at the Warehouse parties where Frankie Knuckles spun. House music then referred to the disco, gospel, funk, and soul Knuckles played at his party.

It’s arguable that Frankie Knuckles is the godfather of what is called Chicago house music today. The DJ known to have premiered the earli-

est known Chicago house tracks was Chicago native Ron Hardy. Hardy incorporated the music of Chicago’s aspiring electronic musicians into his sets at the Music Box long before Knuckles did. These songs were made using secondhand synthesizers and drum machines to create sophisticated four-to-the-floor musical patterns, typically at the tempo of 120 beats per minute. Hardy and many early house producers were the grandchildren of Black Southerners who migrated from places including Mississippi, Georgia, and Alabama to Chicago, looking for a break from the segregated South and for work on the assembly lines in Midwest factories. As a result, there’s a musical legacy connecting rural blues to urban electronic music. Perhaps the most famous music migrant was Muddy Waters, one of the first Mississippians to move to Chicago and plug his acoustic guitar into an amplifier, changing the course of blues music. Twenty years later, young Chicagoans cultivated a new mode of soulful electronic music making from the Muddy Waters moment and changed the course of Black dance (house) music.

At the core of house music is joy, a rhythmic theory of escape, accentuated by what could be called fatal pleasure—the war on drugs and addiction, coupled with dangerous freedom marked by a lurking “big disease with a little name.” The presence of Black women DJs and vocalists makes house music unique, even though too many of these women are erased from the early house music narrative. Stacey “Hotwax” Hale traveled between Chicago and Detroit modeling turntablism to the young men who would come to be known as architects of early Detroit Techno. DJ Sharon White of New York City was among the few women who spun at the Paradise Garage. Ultra Naté not only offered her voice to hundreds of house tracks but also turned her attention

“At the core of house music is joy, a rhythmic theory of escape”Infographic

to the turntables to make sure her name would become part of history. I’m also grateful for the many unnamed house producers, DJs, dancers, and promoters whose voices we will never hear because they passed too soon.

From the DJ History archives: In an extensive interview from 1995, the Godfather of House talks about the first two decades of his DJ career, focusing on the Warehouse, the Power Plant and his return to the city of his birth, New York

By Frank Broughton

During his lifetime, nobody did more to spread the gospel of house than Frankie Knuckles. Christened the Godfather of House thanks to his enduring influence and early role in the sound’s development, Knuckles continued to produce, remix and DJ around the world up until his death, aged 59, in 2014.

Knuckles first learned his craft alongside future Paradise Garage resident DJ Larry Levan at New York’s Continental Baths in the 1970s. When Levan turned down an offer to become resident at the Warehouse club in Chicago in 1977, Knuckles took the job instead. Over the next five years, he made the venue his own, in the process making the club the hottest ticket in town.

So popular were his sets, in fact, that Windy City record stores soon started fielding requests from shoppers for “Warehouse music,” later shortened simply to “house music.” Knuckles became famous for mixing together underground disco, obscure independent soul and muscular European electronic disco records, some of which he also re-edited especially for his DJ sets. Later, he began using a drum machine in his sets in order to beef up the rhythms of the records he was playing.

Knuckles left the Warehouse in 1982 to open his own club, the Power Plant. Here he continued to push the boundaries, incorporating early Chicago “beat tracks” – strippedback drum machine jams – and the early house tracks he produced alongside Jamie Principle for the Trax and D.J International labels.

Following his return to New York in 1987, Knuckles became one of the most in-demand producers and remixers on the circuit, while his association with the flourishing Chicago house movement made him a big draw as a DJ in the UK. He finally released his debut album, Beyond The

Mix, in 1991.

In 1995, around the time he released his second album, Welcome To The Real World, Knuckles sat down with Frank Broughton to discuss his career, focusing on the musical revolution he helped inspire during his time in Chicago.

I started spinning at the Continental Baths in July 1972. As well as the club area, there was an Olympic-size swimming pool and a TV room at the very end. Alongside the pool was a sauna and a shower room, then there was like boutiques and restaurants and bars, and back into an area where there was apartments and private rooms.

I was scheduled to play Mondays and Tuesdays, and Larry [Levan] played from Wednesday to Sunday, and on the nights he played I found myself playing at the beginning of the evening or playing before he woke up... If he woke up. I mean, Fridays and Saturdays he was generally OK, but Wednesdays and Thursdays he wouldn’t get started till very late.

I played different other clubs around the city, including this one after-hours called Tomorrow. Larry eventually left Continental and went to work at a club called Soho, which was owned by Richard Long, who was the premier sound engineer.He was the one who taught us everything about sound.

The Continental went bankrupt and closed in ’76. I worked a couple of other places here in the city, but I was looking for something a little bit more than just a job. I figured I’d already put five years in one club and it had gone bankrupt, so if I was to go and work at a particular club at this point I wanted more of an incentive. If you give me a piece of what’s going on, then I wouldn’t have a problem applying myself and working hard to make everything

work. Or else, to me, it just wasn’t worth it to just go and play records and collect a paycheck.

Originally they wanted Larry in Chicago, but Larry didn’t want to leave New York, and besides, the club Soho was beginning to take off – no, as a matter of fact, he had left Soho and they were already at Reade Street which was what Paradise Garage came from. They were already building that and he didn’t see himself leaving. They pretty much already had their ideas for what they wanted to do with that.

He had no intention of leaving the city, so they came to me second and asked me to do it. I went out to play for the opening and stuff and I was there for about two weeks, and I really liked the city a lot. I only played twice because the club was only open one day a week, on a Saturday. But it worked really, really well. They offered me the job at that particular point and I gave them my terms, how I felt about it. They offered me a piece of the business. So at that point I realized I had to think about what I wanted to do and if I really wanted to uproot from New York City and move there. Then, actually when I looked at it, I didn’t have anything holding me here. I figured, “What the hell!” I gave myself five years, and if I couldn’t make it in five years then I could always come back home.

Describe walking into the Warehouse.

It’s such a long time ago. I look at a lot of different parties and stuff that I play for when we go out on the road, like the Def Mix tour, playing over in England and things like that, and I look at the energy of the crowd and the stuff like that. The energy is most definitely the same. The feeling, the feedback that you get from the people in the room, is very, very spiritual. The Warehouse was a lot like that. For most of the people that

went there, it was church for them. It only happened one day a week: Saturday night, Sunday morning, Sunday afternoon.

Was that the first time you’d experienced that sort of energy?

No, because it was the same thing here [New York]. I mean, you know a lot of these kids that are hanging out and doing all these parties and running around all these different clubs in England. Not so much here in the United States, because it’s a much more surefire thing in England. I guess it’s pop, so that’s the reason why. A lot of them think what they’re doing and the type of fun they’re having in clubs is something new. It’s not. I’m here to tell them that it’s not. This is something that’s been going on a very long time. What they’re doing is actually nothing new. What they’re doing is carrying on a tradition, which I think is great.

As for the Warehouse, it was predominantly black, predominantly gay, age probably between 18 and maybe 35. Very soulful and very spiritual, which is amazing in the Midwest because you have those corn-fed Midwestern folk that are very down-to-earth. Their hearts are always in the right place, even though their minds might not always be. Their hearts are definitely in the right place. And I think those type of parties we were having at the Warehouse, I know they were something completely new to them, and they didn’t know exactly what to expect. So it took them a few minutes to grow into it, but once they latched onto it, it spread like wildfire through the city.

And in the early days between ’77 and ’80-’81, the parties were very intense – they were always intense – but the feeling that was going on, I think, was very pure. And a lot of that changed between ’82 and ’83, which is why I left there. There was a lot more hard-edged straight kids

that were trying to infiltrate what was going on there, and for the most part they didn’t have any respect for what was going on.

Songs lasted a lot longer. I don’t mean length-wise: Songs lived in people’s consciousness a lot longer than they do now.

So it was a black gay scene?

Yes.

Who else was involved?

Just a lot of outsiders. Some people have said there was quite a merging of the alternative, punk scene.

Not with what we were doing. When punk came about they had other clubs like Neo’s, places like that where those punk kids went to. Chicago, believe me, it was very segregated, very much like it is now.

The white kids didn’t party with the black kids. What really tripped me out was when I first moved there...

Growing up in New York City, all kinds of people grow up around each other, it’s pretty much like you see it. To me, here it’s not that big of a deal; race and color is not that big of a deal. There, when I got there, it was. You had the black folks living on the south side of Chicago, and on the immediate west of the city.

The only place where you found people who were different colored people living together was on the north side of Chicago like Newtown, that type of area, which is where I lived. It bothered me at first, when I didn’t see enough white or other races on the dancefloor at the beginning, and then I realized I had my job cut out because I had to try and change that.

And then when I found that the black gay kids didn’t want to party with the white gay kids, and the

white gay kids weren’t gonna let the black gay kids hang out in their clubs, I was like, “Everybody’s rocking in the same boat but nobody wants to...” Everybody wants to play this game and it made no sense to me.

We’re all living the same lifestyle here. We’re rocking in the same boat, but you don’t want me playing in your clubs because you don’t want my crowd following me in. It made no sense to me. When you go out in the gay clubs in Chicago now, it has changed a lot. But while I was there it didn’t change at all.

uptempo dance records, everything was downtempo.

Skatt Bros. - Walk the Night

What were the drugs that were driving the scene at the time?

Probably a lot of acid. A lot of acid.

What was the club scene like when you arrived in Chicago?

By the time I got to Chicago, the disco craze had pretty much already kicked in. The difference between what was happening with music then and music now is that songs lasted a lot longer than they do now.

I don’t mean length-wise: Songs lived in people’s consciousness a lot longer than they do now. So a lot of the stuff that came out in the early ’70s on Philadelphia International, I was playing a lot of stuff like that. That was still working pretty strong in ’77 when I moved to Chicago.

I didn’t actually start doing things like that until like 1980, ’81. A lot of the stuff I was doing early on, I didn’t even bother playing in the club, because I was busy trying to get my feet wet and just learn the craft. But by ’81, when they had declared that disco is dead, all the record labels were getting rid of their dance departments, or their disco departments, so there were no more

That’s when I realized I had to start changing certain things in order to keep feeding my dancefloor, or else we would have had to end up closing the club. So I would take different records like “Walk The Night” by the Skatt Bros. or stuff like “A Little Bit Of Jazz” by Nick Straker, “Double Journey” [by Powerline] and things like that, and just completely re-edit them to make them work better for my dancefloor. Even stuff like “I’m Every Woman” by Chaka Khan, and “Ain’t Nobody,” I’d completely re-edit them to give my dancefloor an extra boost. I’d re-arrange them, extend them and re-arrange them.

Was that a revolutionary thing to do?

No, I’m sure there were other people that were doing it, but to my audience it was revolutionary. But it had been done. It was already being done before I moved to Chicago. When I was still here [in New York] there were people that were doing it here. It was just a matter of time before I could learn how to do it myself.

And it was all on reel-to-reel.

Yes. And by the time I did get around to start doing it, it might not have been revolutionary to anyone else within the industry, from the DJ side of it. But as far as the crowd in Chicago [was concerned], it was revolutionary to them because they had never heard it before. They went for it immediately. next day looking for that particular version and never find it. It used to drive the record stores crazy.

“The feeling, the feedback that you get from the people in the room, is very, very spirituaL.”

The Brian Eno-mentored musician Fred Gibson is amassing a following with tracks built from social feeds and his iPhone. The intricate and emotional results can sometimes even start a party.

By Foster KamerOn a recent Friday night in Manhattan, pandemonium surrounded a waffle truck parked on the corner of 56th Street and 11th Avenue, as thumping beats and the aroma of fresh batter poured from within. An enthusiastic young woman thrust an inflatable giraffe head festooned with a red glow stick through one of the truck’s windows, bopping it to the music. A security guard ripped it away.

Inside the vehicle, holding court, stood a grinning Fred Gibson, the 29-year-old British songwriter, producer and multi-instrumentalist better known as Fred again.., who was following up a show at the Hell’s Kitchen venue Terminal 5 with an ad hoc after-party.

“Chaotic,” he later happily proclaimed the impromptu event, where he previewed tracks from his third album, “Actual Life 3 (January 1 — September 9, 2022),” out Friday. “Just great.”

“Actual Life 3” is the culmination of music that Gibson — a pop hitmaker for Ed Sheeran, BTS and the British grime star Stormzy — started releasing at the end of 2019, after his mentor Brian Eno urged him to forgo writing for others and prioritize his own work. The result is lush electronica-rooted piano balladry, wistful nu-disco anthems and the occasional U.K. garage firestarter, all threaded with samples culled from the far reaches of YouTube, Instagram and his iPhone camera roll — a sonic bricolage of digitally documented lives.

A few days after the concert, Gibson — a smiley, ebullient, occasionally sheepish presence — rolled a cigarette on a West Village bar patio and recalled Eno needling him when he was experiencing a peak of commercial success but had a brewing fear of artistic complacency. He had met Eno at one of the artist’s occasionally star-studded a

cappella gatherings as a teenager, and wowed him with his production talents, which led to Eno (“a wizened cliff-pusher,” as Gibson described him) bringing him on as a producer on some of his projects.

“I know that Fred has sometimes referred to me as a mentor, but actually, it works both ways,” Eno said by phone. “What he’s doing is quite unfamiliar — I’ve actually never heard anything quite like this before. He always seems to be doing it in relation to a community of people around him — the bits of vocal and ambient sounds.”

Eno was referring to the basic construction of a Fred again.. song. Many tracks start with Gibson using one of thousands of ambient drones Eno once gave him. From there, he’ll go into his digital scrapbook of found footage. While some samples employ familiar voices — the moaning rap of the Atlanta superstar Future, an Instagram Live freestyle of the rapper Kodak Black, vocals from a call with the Chicago house D.J. the Blessed Madonna — the vast majority are relatively obscure. They include a stadium worker Gibson joked around with after a Sheeran show, audio from a nightclub he recorded with his iPhone, spoken word poets and burgeoning bedroom pop singers he caught glimpses of while scrolling his various social media feeds.

Brian Eno, Gibson’s mentor, described his music as “romance, in a sort of maelstrom of emotion.”Credit...Peter Fisher for The New York Times

Gibson then cuts, distorts, pitchshifts, stretches or compresses the samples into shimmering cinematic soundscapes, and sings atop them in his soft, pleading croon. Some are cavernous, others dense, but they all retain the deep warmth of something homespun — the ideal foun-

dation for lyrics about feeling too much and not nearly enough that map thin fault lines demarcating love and loss. The result are tracks that leave listeners both laughing and weeping on the dance floor.

Gibson estimated that he’s experimented with thousands of different ways to turn the speech of complete strangers into something musical. “You’re constantly trying to create as many vacancies as possible for accidents to happen,” he said. “But at the beginning it was very labored, quite tortured, if I’m honest,” he added. “It felt like I was distorting their spirit.”

One track was crafted from footage of a young Toronto-based performance artist named Sabrina Benaim performing her piece “Explaining My Depression to My Mother,” which would go on to become the thumping dirge “Sabrina (I Am a Party).”

The source material is a full-tilt confessional characterizing the vicissitudes of anxiety and depression — not exactly the kind of thing obviously complemented by beats from a successful pop producer. “I was anxious with everything I was putting onto these people,” Gibson said. “I felt like I was projecting onto them.”

Speaking by phone from Toronto, Benaim remembered hearing the finished track for the first time, after Gibson reached out over Instagram. “It was the wildest thing,” she said and laughed. “It was like I left my body. He handled the emotional center of it so well — he just cared so much about not ruining or soiling the poem in any way. It’s coming

“the mystery of it is: How can anybody make it look so easy?”Photo Songkick

from such a careful place.”

Romy Madley Croft — a singer-songwriter in the xx who tapped Gibson to produce her own debut solo single, “Lifetime” — worked with Gibson and Haai on “Lights Out,” a song released earlier this year, in nearly the same way. Croft had given Gibson an xx demo that never came to fruition; a year later, Gibson mentioned having done something with it.

As she explained in a recent phone call, she was gobsmacked by the result, a dance track that mixes laser squelches, piano chords, a skittering beat and Croft’s wistful vocals. “He had just given it a new lease of life,” Croft said. To her, the record reflects a thematic link in his work: “A thread of emotion and vulnerability within it that ties it together, as well as a lot of joy.”

Gibson continues to experiment with turning strangers’ speech into something musical. “You’re constantly trying to create as many vacancies as possible for accidents to happen,” he said. Credit...Peter Fisher for The New York Times

Eno said he finds many of Gibson’s samples to be “tender and beautiful.” “To marry that with the kind of energetic chaos of the music he does is, I think, a beautiful combination,” he added. “It’s romance, in a sort of maelstrom of emotion.”

The new album may be the apotheosis of this aesthetic. Gibson’s first two LPs, made during and immediately after the pandemic lockdown, concerned the illness of a close friend and its aftermath, and are often pensive affairs. “Actual Life 3” is an unfurling of sorts, a more cathartic, misty-eyed dance-floor moment. Its unlikely collaborators include Kieran Hebden, a.k.a. the electronic musician and producer Four Tet, known for the kind of dense, protean electronica compositions that rarely (if ever) abide anything close

to a typical pop song’s structure.

“He pulls me in a direction I wouldn’t normally be working in,” Hebden said on a recent FaceTime call. Gibson’s songs, he explained, are “great melodies and chord sequences, elegantly done. The work that has been done is considered. It doesn’t always sound ridiculously slick — there’s nothing very cynical about it. It’s quite direct, and honest; it just feels deeply refreshing, isn’t hidden away, and isn’t super mysterious.”

“But,” Hebden paused, “the mystery of it is: How can anybody make it look so easy?” He laughed.

At the waffle truck earlier this month, after playing the last in a series of then-unreleased songs to his increasingly hyped crowd, Gibson told Hebden — who was among his mischief-makers that night — to pick a final song. Hebden looked at him knowingly, and changed tracks. Miley Cyrus’s “Party in the USA” blasted over the speakers. The crowd exploded into verse, and Gibson danced along, laughing. The musicians made their way out of the truck and back into the venue thronged by fans, another memory made in the night, soon to be posted for posterity — potentially, the start of another song.

“House music is a feeling” is a phrase coined by multiple producers, DJs and other prominent figures in the electronic music scene. It is also an unoriginal title shared by around a hundred house tracks. Is this just a figure of speech or is there sound scientific reasoning behind it?

Marissa Trimble October 8, 2018You may have heard of dopamine, a neurotransmitter found in the brain most commonly known for its association with feelings of happiness. When dopamine is released from a region in the brain known as the ventral tegmental area, it stimulates dopamine-sensitive neurons in other parts of the brain, namely the nucleus accumbens, amygdala and hippocampus. This is known as the mesolimbic pathway, commonly referred to as the reward pathway. Dopamine is released when we partake in rewarding and pleasurable activities which activate the aforementioned pathway. This includes activities essential to one’s survival such as eating and having sex, which our bodies reward us for. Furthermore, drugs such as nicotine, cocaine and heroin boost dopamine levels. So, why does listening to music also trigger this response?

Although listening to music can produce a rewarding feeling, it is not intrinsic to human survival. As such, the effect of music on the reward pathway has baffled people from the common party-goer to the puzzled scientist. Hence, a multitude of studies have investigated the subject, with the majority utilising brain scans to explore the neural correlates of this reward system. A study at McGill University carried out by Salimpoor and Zatorre shed some light on this topic 1. The study showed that listening to music generates a strong transmission to the nucleus accumbens. Zatorre claims “music has such deep roots in the brain that it engages this biologically ancient system”, and the results of his study support this. The findings demonstrated that when participants listened to one of their favourite songs for 15 minutes, dopamine levels in the brain significantly increased by 9% compared to the dopamine levels of participants who did not listen to music. Howev-

er, it is important to note that only eight volunteers participated in the study and it did not investigate different genres of music. Although this study demonstrates the influence of music on the brain’s reward or dopaminergic system, it is unclear whether different genres have different effects on the dopaminergic reward pathway. Nonetheless, several studies that examine the specific traits of house music suggest that listening to house music is an extra pleasurable experience.

House music has particular qualities that make it ‘so damn good’. Beats per minute (BPM) plays a fundamental role in how humans process music. House music has an average speed of 120 to 130 BPM. Interestingly, studies show that music that lies between 90 to 150 BPM produces greater feelings of happiness and joy as well as diminishing emotions associated with sadness 2. Tempo directly affects a person physiologically, namely their respiratory and cardiovascular system, by stimulating the sympathetic nervous system. Evidence has shown that the respiratory system exhibits a degree of synchronisation with the tempo of the music with faster tempos increasing heart rate, blood pressure and breathing rate, whereas a slower tempo produces the opposite effect. These effects on the cardiovascular and respiratory system explain how house music can generate feelings of excitement and happiness.

Another theory is that the ‘build up and drop’ incorporated into house music influences the dopamine reward system. The drop is when there is a drastic change in beat and rhythm; momentum is built up and then the bass and rhythm ‘hit hard’ or ‘drop’. It has been suggested that the length and intensity of anticipation during the build up to a drop in a house track plays an important part in how much of a reward your brain

School of Music and in the Center for Cognitive and Brain Sciences at the Ohio State University, aim to fully understand and explain why this is 4. Huron uses a five response factor system involving imagination, tension, prediction, reaction and appraisal to understand the effects of musical anticipation. Combined, these five factors cause a person to react to music. For example, say you are listening to a song and a build up begins, you are already imagining that there is going to be a satisfying drop. The tension response is preparing your body for the drop (and also preparing a dopamine hit to the brain) as does the prediction response. The reaction and appraisal response occur when the body

assessing its environment and situation and determines that the dopamine should be released.

Other factors that influence the relationship between house music and the dopamine system include socialising and dancing. Humans are social creatures – we love to interact with others and crave a sense of belonging. Furthermore, as you have probably experienced, emotions are contagious and spread through social networks, a fact supported by psychological studies. In one study, participants were shown photographs of another person who displayed either a happy or sad expression 5. The emotions experienced by those viewing the photographers were assessed using MRI

scans and, in the majority of cases, they were found to experience the same emotion as the person in the photograph. Therefore, when in a room full of others enjoying themselves and dancing a collective positive mood can be generated due to our brains subconsciously mimicking the perceived emotions of those around you.

Dancing is also part of the dopamine release process – be it in a club or if you are just home alone having a boogie. Like many other physical activities, dancing releases endorphins into the bloodstream. Endorphins are another form of neurotransmitter and their main function is to decrease levels of pain felt in the body. When they are released they can also stimulate feelings of euphoria; when you dance, you can feel great. Therefore, when dancing to house music, you can experience the dual action of dopamine and endorphins, a hugely pleasurable combination.

It is important to consider that personal taste affects how a person feels when listening to music. House fans have a predisposition to repetitive, pulsating rhythms and the characteristics of house, including the previously discussed BPM and build up and drop. It is thought that various personality traits can affect a person’s music taste such as extraversion, agreeableness and neuroticism. Extraverts tend to enjoy upbeat and energetic music (such as house), which people who demonstrate a high level of agreeableness also prefer. Neurotic people tend to experience higher levels of emotional response from music, both positive and negative. Influences like age, gender and how an individual wants to be viewed also affect what kind of music you listen to and how it makes you feel. Cultural assumptions can result in certain prejudices towards music with regards to gender – it is often assumed that boys prefer rock music and girls prefer

pop. Similarly, we think of older people preferring quieter classical music as opposed to bass-heavy EDM.

The unique features of house music can explain why passionate fans say it just feels ‘so damn good’. Through its physiological influence on our dopaminergic reward system, music affects us both mentally and physically. One could say that house music listeners take full advantage of this phenomenon. Our brains cannot help it that we love house music’s big beats and we cannot help two-stepping away to it, with our dopaminergic system loving it just as much 6.

George Hull, the founder of Bloc, wrote an article damning today’s ravers, but how much truth is there to the claims we’re spineless and dull?

By Anna Cafolla Photo By Weronika DurachtaOne week on from Bloc’s swan song in Minehead, I’ve just about readjusted. Thousands bade farewell to a weekend that, for almost a decade, successfully united sections of the dance music community to a syncopated beat. The ravers had annually set up camp at the Butlins resort: Detroit techno pumped from a carpet-walled room usually reserved for bingo and Neil Diamond tribute acts, and the beats of Egyptian Lover snaked down the waterslide with you at his pool party. Across three days in the big top, barely popping a head into our chalet, there was a beautiful sense

of euphoria only an event like that can muster. I’ve spent the rest of my working week riding bleary-eyed on the Bloc wave, to arrive absolutely stumped by promoter George Hull’s recent Spectator article.

Hull, a founder of Bloc and London’s Autumn Street Studios, penned an article on why he’s out – done, totally over – today’s dance music. In particular, he’s tired of the hipster subculture that surrounds it, the young people are totally harshing his vibe. We’re too uptight, too meticulous to truly appreciate and elevate dance music to a higher level, as “they lack the

Photos By Weronika Durachta

Photos By Weronika Durachta

sense of abandon that made raving so much fun”.

The level of disdain for the people lining the pockets of promoters is pretty disturbing – although what an honour that our generation is credited with bringing down a Spartan-like music genre and all its trappings. Sidelining the Bloc audience as ignorant hipsters pushes this argument into angry, bootleg jeaned old man territory – completely out of touch. Additionally, it’s completely out of step with what’s at the heart of the electronic community, which should be a welcoming, nonjudgmental space. So, it’s concerning to hear such arrogance from someone who curates the scene.

It’s interesting that they’re happy to sell tickets for luxury chalets at up to £240, but scolds ravers for planning these activities months in advance. If anyone is a problem it isn’t the hipsters – a truly contemptuous word co-opted by people who

scoff at student protests and read right-wing rags like, say, the Spectator – it’s those at the top. The London superclubs, the festival bookers, label execs and curators. Those at the grass roots are not to blame for the supposed death of dance.

Bloc reaped the rewards of those who took up their discount offers, but Hull weeps at the loss of ‘spontaneity’. In reality, being ‘spur of the moment’ isn’t possible for those of us who spend three-quarters of our salary on our rent. But damn us for expecting a “level of service” for something we spend months saving for.

Hull maintains a bizarre nostalgia for raving days in the fields of the Home Counties – which, at 33-years-old, were something he didn’t genuinely experience. His heydey, the early 2000s, gave him an advantage as a dropout who began promoting during the birth of the superclub. We’ve lost the “true

Thatcherite spirit” that allowed ravers before us to experience the freedom and rebellion we have never tasted. It’s peculiar to yearn for days when unemployment was rife and the administration reacted so ominously to its youth. Rave culture was railing against the terrible shit everyone dealt with the other 90 per cent of the time. Hull’s contempt for volunteers eager for Wi-Fi to hand in coursework is inappropriate – given that student loans have skyrocketed since his golden age of rave.

Dance music culture is reactionary: the queer discos of Downtown New York in the 70s defied a government that ignored the plight of the LGBT community, and Chicago house offered an escape for young working class black men. The social and political climate has changed: we’re battling a housing crisis and the swelling wave of university graduates with no secure future, so we have adapted dance culture to

a crowd baying at the touch of a cue ball. You can easily find yourself hand-in-hand with dozens of other anonymous ravers at Four Tet, as Kieran drops “Opus” for the hundredth time this year to a crowd who reacts like it’s the aural vision of their entrance into heaven. The festival comes from a long lineage of music events taking over the retro holiday camps, from the Northern Soul lock ins to 80s acid weekends. Honestly, the state of electronic music right now could not be better. Despite our licencing laws we’re one of the top places to rave in the world, with mainstays like Fabric still going strong and after-hours club nights like Jaded at Corsica Studios enjoying continued success. Hull’s dismissal of ”overpaid circuit DJs” ignores the talent that deserves to be rewarded. Just looking at Bloc’s lineup would tell you that. The strength of Helena Hauff’s compelling techno sets, Omar-S’s pounding beats chilling thousands to the bone and Belfast boys Bicep pulling out banger after banger.

George Hull’s article is a death rattle. It boils down an entire generation to a fallacy imposed by the bitter. Because all the shit pills we take these days mean we don’t have the brain cells to simultaneously care about Rødhåd’s set and what time we’re in for work tomorrow.