Dreaming past the anthropocene

by Hannah Sampé, August 2021

A study on rest / on moulding

/ on patience / on observing weight

/ on negotiating discomfort

/ on softening / on trusting that relaxation will come eventually

/ on realizing: my body is material, is matter

What happens, if we withdraw from producing and leave nature to itself? What happens, if we leave ourselves be? If we rest long enough, what will grow back?

Victor Fung, Jija Sohn, Agnetha Jaunich, Merel Heering,

September 2021

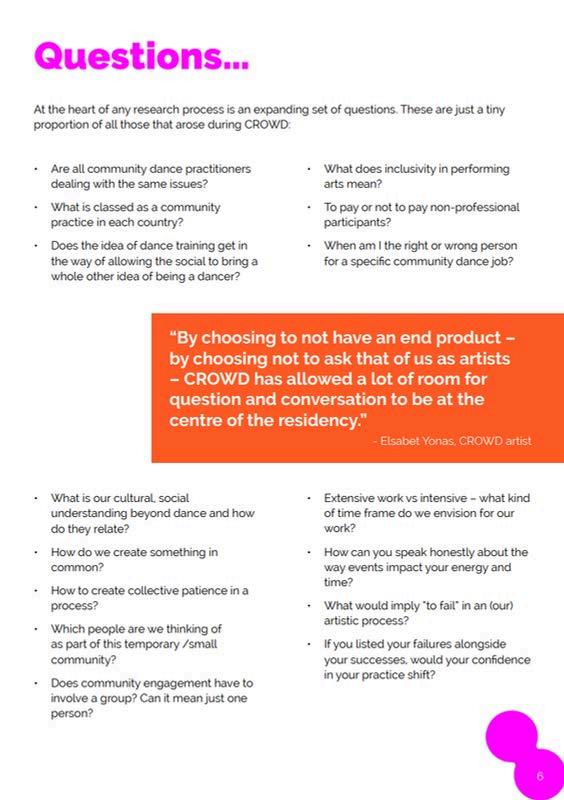

Our two-week residency at Dansateliers Rotterdam was a journey full of impulses, reflections, and interactions that gave us new ways of thinking about our work.

We started thinking about community engaged / based practices as… spending time to find ways of relating to or interacting with people a way of finding our own urgencies and our sense of belonging a strategy to disperse power a way of discovering and sharing joy a way of being together a way of writing new contracts a way of recalibrating and remodeling ways in which we experience the world a way to empower a way of reconnecting – the roots of why we value being part of a community

We leave with lots of questions, some answers, and a basket full of food for thought.

Agnetha Jaunich, February 2022

English translation begins on page 11

WasheißtdennhierCommunity?!

Community, dieses Wort habe ich, vor meiner Residenz, eigentlich immer ziemlich unbedacht benutzt. Im Tanzkontext meinte ich damit Projekte, an denen NichtProfessionelle Tänzer beteiligt sind, nicht mehr und nicht weniger.EswarmehrwieeinLabelfürmich,ohnegenauauf die Inhaltsstoffe zu schauen. Dies hat sich durch CROWD grundlegend für mich verändert. In meiner ersten ResidenzPhase in Rotterdam wurde mir dies zum ersten Mal bewusst. Im Gespräch mit meinen Kollegen fing ich an das Wort Community mehr zu reflektieren und mich zu fragen, washeißtdaseigentlichwirklichfürmich?

Meineichdamitwirklichnur,dassandemProjektMenschen beteiligt sind, die mit Tanzen nicht ihr Geld verdienen oder bedeutet es doch mehr? Die Antwort auf diese Frage ist wahrscheinlich leicht zu erraten. Natürlich steckte für mich hinter diesem Wort eine tiefere Bedeutung. Nur hatte ich über diese noch nie so intensiv nachgedacht. CROWD gab mirdieMöglichkeitdazu.Indenverschiedenen.

In den verschiedenen Projektphasen konnte ich in immer wieder neuen Kontexten, sowohl örtlich, als auch mit immer wiederanderenMenschen,überdasWortreflektieren.

oben herab gelingt, sondern ein gemeinsamer Ein Weg, den man am besten gemeinsam geht, volle künstlerische Potenzial, dass in jeder verborgenliegt,zumAusdruckkommenkann.

Durch CROWD hat das Wort Community für mich eine all umfassendereBedeutungbekommen.Communityengaged dance practice kann die Einbindung von Menschen aus der Gemeinde oder einem spezifischen Ort sein, es kann aber auch alles sein, wo auf Augenhöhe in der Gemeinschaft gearbeitet wird. Und das sagt viel darüber aus, wie ich selbst künstlerisch arbeiten möchte. Ich möchte keine künstlerischen Prozesse eingehen, in denen alte hierarchischeStrukturenreproduziertwerden.Ichmöchtein kollektiven Prozessen arbeiten, gemeinsam nach Konsens suchen und mich von verschiedenen Ideen inspirieren lassen. Und dies ganz unabhängig davon, wer an einem Projektbeteiligtist.

Die Residenz hat mir die Möglichkeit gegeben intensiv über das, was mir schon immer wichtig war, nachzudenken und dies in Worte zu fassen. Und genau das hat mich in meiner Arbeitwachsenlassen.

What does community mean here?!

Before my residency, I used the word ‘community’ rather carelessly. In the dance context, I meant projects involving non-professional dancers, nothing more and nothing less. I was using a label without looking closely at the ingredients.

CROWD has fundamentally changed this for me. I became aware of this during my first residency phase in Rotterdam. In conversations with my colleagues, I began to reflect more on the word community and to ask myself, what does that really mean for me?

Do I really just mean that the project involves people who don't make a living from dancing, or does it mean more? The answer to this question is probably easy to guess. Of course, there was a deeper meaning behind this word for me. Only I had never thought about this so intensely. CROWD gave me the opportunity to do this. In the various project phases, I was able to reflect on the word in new contexts, both locally and with different people.

Keywords such as participation and eye level made a particularly strong impression on me. I quickly realized that community, as I understood it, did not exclusively mean a certain group of people from a specific place or district. It could of course do that too, but for me it wasn't the decisive factor that defines a community. The answer to the question of how I would translate community for myself is as simple as it makes sense to me. It's about community. It's about working together, exchange at eye level, letting each individual have their say and the knowledge that artistic work doesn't succeed from above, but is a joint process. A path that is best walked together, so that the full artistic potential that lies hidden in each group can be expressed.

comprehensive meaning for me. Community engaged dance practice can involve people from the community or a specific location, but it can also be anything that involves working on an equal footing in the community. And that says a lot about how I would like to work artistically myself. I don't want to enter into artistic processes in which old hierarchical structures are reproduced. I want to work in collective processes, search for consensus together and be inspired by different ideas. And this is completely independent of who is involved in a project.

The residency gave me the opportunity to think intensively about what was always important to me and to put it into words. And that's exactly what made me grow in my work.

Hannah Sampé, February 2022

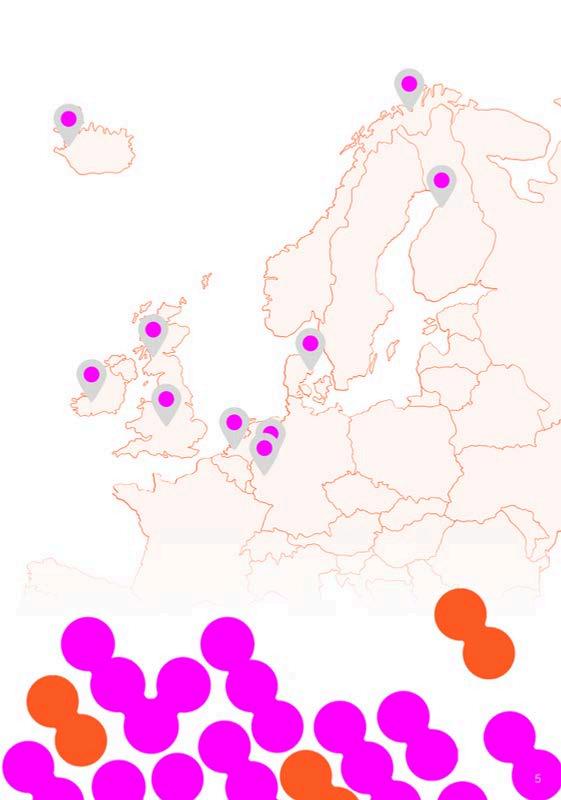

As romantic as community- based art making sounds, the role of the conditions of labour and the role of economies around dance projects is not to be underestimated. Our residencies involved countless discussions about the working conditions of freelance artists with regards to travel, accommodation, interaction and negotiations with institutions, economic security, networking, burn-out, overbooking, double booking, unemployment, isolation from non-artistic communities at home, sustainability of their work.

The economic histories of places we were visiting and diving into played a crucial role in the shaping of cultural landscapes we encountered and were extremely prominent in our observations and interactions: Migration and displacement of people, physical ability and protection of certain bodies as opposed to others, absence and presence of people living there or once having lived there, the question of access to certain sites and places, the role and standing of nature.

In most of the places, art seemed to be interwoven into these fields in various ways. Be it the deserted island of Varjakka in Finland or the huge deserted coal mining sites in the Ruhrgebiet in Germany, artists seemed to be very welcome guests. What is this interesting relationship between art and post-industrial sites?

On the one hand, sites that lost their economic value often provide what is scarce in cities, where many artists work: space. On the other hand, artists seem to be invited to act as the healer of a broken civilization or as the glue to weave nature and culture back together in sites where industry or civilizationhadastrongimpactonnature.

Looking at this critically, the question arises, whether inviting artists to such spaces is simply another way to re-capitalize thoseplacesthatlosttheireconomicvalueanddesirability?

And how does this dynamic actually cater to the local community of these sites? Who profits from it, who is even involved and in touch with the art that takes place there?

These thoughts and questions remain from our observations and reflections and are what I would like to keep in mind with regards to my own practice and future projects.

Elsabet Yonas and Maya Dalinsky, August 2022

Elsa:

Did you experience feeling in community?

When/how?

I didn’t really have any very strong feeling of being in community. Which isn’t a bad thing. I also know from the past – and I guess this has kind of reaffirmed it for me – that I’m someone who enjoys having time to themselves but also having time just one-on-one or in very small groups. That said, even if I’m with just one other person, there is kind of a feeling of being in community that’s possible. But I wouldn’t say that this one-to-one relationship is like a community.

When I am in a certain situation or with certain people, I am reminded of times I have felt in community. And that’s a very nice feeling. Remembering that is feeling in community. Even if it’s not the current reality. So maybe feeling in community is something you can have even when you’re not directly involved with a community, not physically present in that space or with the people, or in that task or action or activity.

Maya:

What would you happily do again?

Elsa:

The entire residency! But more specifically, I would happily reuse this mindset and approach toward creative process that allows room for the social aspects that feed into the creative exploration. This approach that allows for a balance and includes activities and experiences that are not conventionally considered “working”, because I think it produced really fruitful results.

Maya:

Elsa:

What will you take away and incorporate into your practice/daily life? What risks could you take?

One thing that I’ll take away is definitely to not be shy about music. So, integrating music and dancing to music, and that being okay. And one thing I’ll incorporate into my daily life is the popping exercise: keeping tension in the arms and releasing… I’d also be interested in integrating something that Elsa brought into her workshop, which was the piece of paper at the beginning where you ask everyone to write down something that they hope for, a fear that they have, and their intention.

One risk I’d take is to not shy away from leading things more confidently, for instance my own workshop. I don’t have to hide behind goofiness or self-deprecating humour in order to make room or space. I have a responsibility to the people that come into my practice to lead them confidently, and guiding this does not mean that I am not giving them time and space for their experience. On a very concrete level that means just keeping things rolling along. Risking interrupting people, taking risks that are really about staying on task, while also being attentive to people’s need for rest or time to process things.

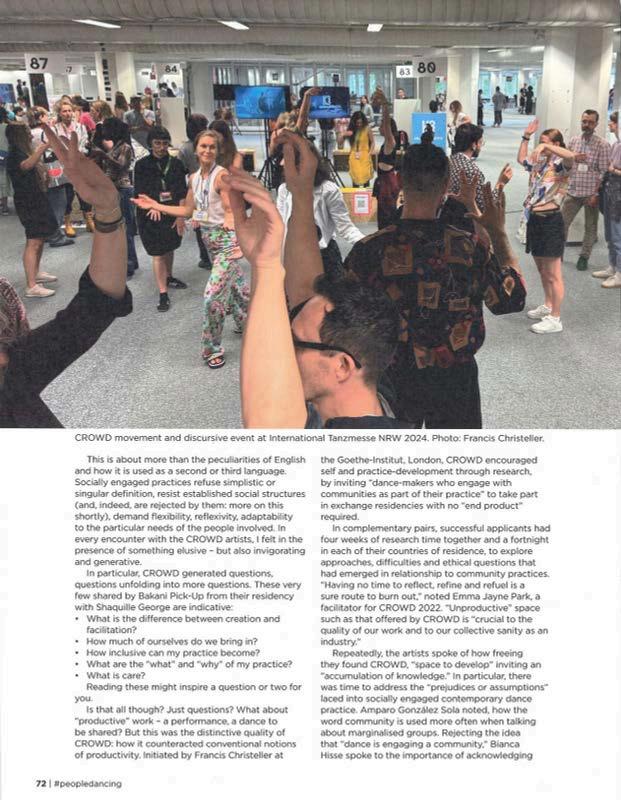

Emma Jayne Park, August 2022

Space to develop a practice is crucial, both to the quality of our work as community dance artists and to our collective sanity as an industry. Having no time to reflect, refine and refuel is a sure route to burn out, and with burn out often comes the departure of those who have developed their craft over years – many have often done this quietly as they foreground the communities they work with and exist between – from the sector.

However, the practicalities of these spaces for reflection are far easier to define than the process of developing a practice. In preparation for CROWD, I asked several friends who work in artist development what they might expect to happen over four weeks dedicated to ‘developing a practice’ – none of them could answer clearly or simply.

All were clear that the artists had to drive this (phew!) but in some ways they also anticipated that all artists would have an ordered, reflective praxis for understanding what they need. This unnerved me a little: in my experience as an artist the time to develop a practice is reserved for a few, which is why these spaces are so crucial but also why they might be overwhelming.

We are working most of the time. We see the opportunity to develop and feel a pull towards it. We apply with language that we think might entice a panel.

We are surprised when successful. We are working all the time and don’t have time to mull it over. We are grateful so will meet the expectations set. We take care of the practicalities. We arrive – and what next?

How can the work of development be truly responsive and emergent, particularly in the context of community dance practice? Because how is it possible to develop a community dance practice without being in and with community?

It is easy to imagine that we know what we need before we arrive somewhere, and therefore that we can commit to opportunities as a frame for our time. Yet, when you often make things work on less time than is required, how do you knowwhatyouneedfromtimewithoutboundaries?

The empty schedule can look like a chasm, and as we plot our desires (and the desires of others) into it, it can quickly become full. So full that we return to the rhythm of not having enough time or not feeling spaciousness in the time thatwehavemade.

And then before we know it, these desires we voiced when we didn’t have time have created an agenda for the week. What do we do if this is not the agenda that best serves us? And when in negotiation with another – a new collaborator whom we haven’t met – how do we renegotiate the time, so it offers the meaningful experience that we now desire, dreamtuptogether?

Isitethicaltoorganiseatthelastminutewithcommunities?

Is it ethical to schedule a workshop without the full context of those artists who are developing together?

I would argue that the process of organising a development residency is not dissimilar to the process of facilitating community projects. The deadlines and outcomes (with a pre-set agenda being a form of outcome) don’t always leave space to respond. And this is not a bad thing, necessarily, but a complicated question that Alex McCabe and Stefanie Schwimmbeck discussed at length. Where is the space to begin, respond and then decide what feels right? Where the time is best spent?

Even in a project as spacious as CROWD the patterns of behaviour that dictate the sector can creep into the room. There is no judgement in this, it simply is true that everything is a microcosm of the world we live in, unless we shape it otherwise.

by Amparo González Sola, August 2022

We are in Reykjavik.

We, right now, are Ásrún, Amparo, Ólöf, and Tinna.

We are a temporary we, a constantly changing one.

We don’t know exactly what we will do together.

We delay the moment of making statements.

We decide to think of this encounter as a creative process.

We decide to trust in the fact that the encounter, in itself, will give us clues about how to continue.

We are not expecting big things, we trust in the fact that small movements can produce huge transformations.

We talk about how our practices began.

We realize that there is always a previous moment, a previous encounter.

We do a kind of archaeology of our practices.

We realize the amount of people and places that hold us, that hold our trajectories.

We thank them.

We talk about the politics of quoting, about the politics of acknowledgment.

We talk about voices and which persons we name when talking of what we do.

We immerse in the pool. Under the water everything resonates, under the water the words touch us and each sound is perceived through the skin.

We talk about what things we notice and what things we don’t, about what becomes visible or invisible to us.

We talk about being able to perceive what seems to be invisible and to give attention to what we didn’t use to see. We decide to make a list of things we notice these days together.

We do a collective list.

In the list we write places, persons, concepts, gestures, actions.

We make also a list of questions.

We don’t pretend to answer the questions right now, we want to stay a bit with them, letting them complexify our discussions.

We walk. Walking the thoughts move differently. We walk against the wind, we can’t talk, the wind makes the words fly in the air.

We stay in silence.

We listen.

We discuss what a “community engaged dance” would be. We ask each other: How do you relate with this concept?

We realize that a lot of prejudices are contained there. We decide to let the discussion open. We cook.

We share food.

We meet Vala and Lovisa.

We listen to their stories.

We share memories of the things we had done in the past.

We share our screens.

We find things in common.

We find things different.

We talk about “context”, about the relevance of giving context, and at the same time the importance of avoiding putting labels or fixed categories to things.

We talk about our own contexts, and backgrounds.

We talk about how to avoid patronizing others, about how to break down prejudices.

We talk about community and inclusivity, about how some words become a kind of empty box.

We share some strategies we have used in our works.

We don’t know many things.

But we also know many things.

We go to swim, under the water we can feel the movement of others, under the water we can feel how our movement affects others and the environment.

Under the water we can feel how the others’ movement moves us.

We hang out in the pool.

We take breaks.

We feel that the breaks are very important moments. We read Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui.

We talk about curiosity, about trusting in the process, about being patient.

We talk about how to create a collective patience. About how to create a collective trust.

We wonder how an “extensive process” would be.

We meet Sara.

We find things in common.

We find things different.

We talk about “context”, about the relevance of giving context, and at the same time the importance of avoiding putting labels or fixed categories to things.

We talk about our own contexts, and backgrounds.

We talk about how to avoid patronizing others, about how to break down prejudices.

We talk about community and inclusivity, about how some words become a kind of empty box.

We share some strategies we have used in our works.

We don’t know many things.

But we also know many things.

We go to swim, under the water we can feel the movement of others, under the water we can feel how our movement affects others and the environment.

Under the water we can feel how the others’ movement moves us.

We hang out in the pool.

We take breaks.

We feel that the breaks are very important moments.

We read Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui.

We talk about curiosity, about trusting in the process, about being patient.

We talk about how to create a collective patience. About how to create a collective trust.

We wonder how an “extensive process” would be.

We visit an independent theatre in the city, we talk about the need of creating community to produce social changes. We walk.

We touch the lava with our hands, it is still warm. And in the night the earth trembles. We feel the earthquakes, a lot of earthquakes. We have fear. We are excited.

We think about all the processes that are going on on earth beyond our will, things that are happening, most of the time invisibly and silently to us, to think in this geological scale it is a kind of breath.

We decide to write something to share with you.

We create a temporary we, a we that is not homogeneous, a we that is full of contradiction.

This is an I, writing in we. This is a fabulative practice. A we as a fiction, a temporary one. We think of this encounter as a creative process.

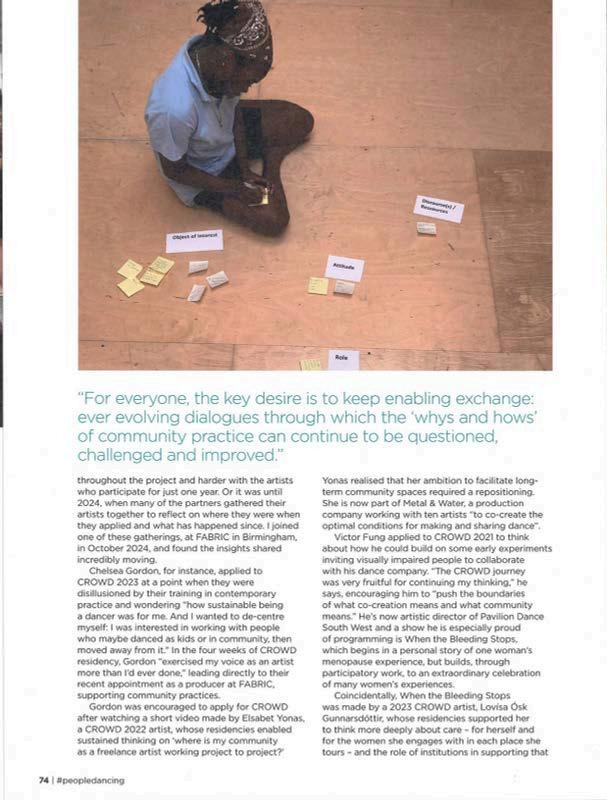

Chelsea Gordon, November 2023

What I’m taking from CROWD still feels like a bit of a blur. The first residency with Hubert was about realising that anything is possible in a way, anything can be reframed to interpret something different. There was lots of play and rumination.TanzFakturandourfacilitatorNinaPatriciaHänel gave us a lot of space to wander and encouraged dialogue within the studio and at home in our shared artists residence. Reflecting back I recognised how impactful it washavingpeoplesupportthoseideasthatIwasstilltrying tomakesenseofformyself.

Thesecondresidencytookplaceatthesametimeassome other professional development I was doing, and this all informed each other. There was a real emphasis in Birmingham on how to connect to people, and understanding what the intention is before the work even starts.Howdoweactuallyengagewithpeople?Howdowe build relationships? How do we address what we want before we even approach people? I am learning that with community dance, people feel more confident when you have a realised idea or something that you’re sure about, evenifit’snot100%figuredout.

For people to feel comfortable enough to try and to fail, they need to at least know the skeleton of what they are approaching. They need to feel safe enough to be playful.

I felt I could be more authentic and vulnerable in the second residency, because of the familiarity we had built up in Cologne. On the very first day with Hubert, we went to the studio and were like, what to do?! Then we went for lunch, and an hour turned into two hours, and we didn’t know what we should get back into the studio for, so we went for a walk, explored, got chatting, and I thought: OK, I prefer this way of working. Hubert initiated it, and I felt safe enough to contribute because this was also natural for me. It took a moment for us to realise that there wasn’t any small print: the residency is for us to get to know each other and to explore community dance, and we can explore that the way we both see fit.

I realised that a lot of the ‘getting to know each other’ involved asking ourselves: why do we do what we do and who is it for? I really appreciated Hubert’s freedom to constantly offer his mind and energy during both residencies, at times I felt very moved that we had connected so well and so quickly. Nina Hänel (TanzFaktur facilitator) put it perfectly: Hubert demonstrates the ‘what’ andIthe‘how’,andforusthatworkedincrediblywell.

There have been a lot of things that I have learned through CROWD that I didn’t know would be received as artistic or a practice. It’s like improvisation – the practice of “yes, and” –where anything you put into a space, it’s like: ok, let’s explore this. Because of that, you can pull out so much more that you wouldn’t have thought mattered or might be useful. In the second digital discourse session, one of the guest artists - Simone Kenyon - said that her practice involves walking. Walking is something I do habitually, to help declutter my mind or make sense of something: by the end of the walk I’ll have all these ideas and everything ironed out. But I didn’t realise that that can be a practice! Or that this could be a way of building relationships with people before getting into a studio.

I’m from Birmingham but don’t usually work here, so it was very humbling to have a residency here and think in that creative way. It forced me to face a lot of things internally, about how I engage with myself before engaging with other people. How do I get myself into the room? What’s my motivation? There is something important I had to learn about rediscovering your own city and Adam Carver (FABRIC facilitator) played a huge role in helping me reimagine the existing. It was necessary to acknowledge that I am also part of many communities and that how I treat myself will be reflected in how I work with other people.

Lisa Reinheimer, November 2023

In2021IwasartisticcoordinatoratDansBrabant,andoneof theartistsIwascollaboratingwith,JijaSohn,joinedCROWD initsfirstyear.SoIgottoseetheprogrammefromherside, and how in that period she rethought her practice. What does it really mean to be together in a space? What does it really mean to have different bodies and capacities and capabilities? How can we find ways to give that more equality – and what does that mean? If somebody needs a lot of support, is it always that we go and take care of that person? Or can we find a way to be on the same level, acknowledging that the other maybe needs more physical support, but I maybe need more mental support? In what way can we be next to each other? CROWD helped Jija to open up different perspectives on how you could accomplish that, thinking through how to deepen the practice and find different rules in order to lift the whole spacetogether.

For Jija, CROWD also gave an acknowledgement that this practice is valuable. In the Netherlands, when we say community arts, it’s seen as amateur: the work is valued less. Also in 2021, DansBrabant was involved in a community-building project called Performing Gender –Dancing in Your Shoes, and this intersected with CROWD, helping me to see that social engagement is an important part of the practice that we’re doing and that we need to support. So when I decided to apply for the job of director atDansateliers,thatwasoneofthethingsIfocusedon.

I arrived at Dansateliers in November 2022, and one of the first people I met was Amparo González Sola, a participant in the second year of CROWD. Amparo has been working with some very different and challenging groups, and goes back and forth, interweaving participation in her practice. In the productions she makes, maybe you can’t see that there was a whole engagement with a community: she gives it another life, both for the community and the work she’s creating. At Dansateliers we’re now writing our new culture plans for 2025-2028, giving an associates group a bigger productionbudgetforfouryears,andAmparoisgoingtobe partofthat.

Merel Heering has been Dansateliers’s facilitator with CROWD for all three years, so for me she was a guiding principle in how this year’s residency could take shape. I brought to her lots of questions about leadership, and how the organisation works, hoping this could be part of Shaq George and Bakani Pick-Up’s residency conversations. What does leadership mean in different contexts, either with a community or with an organisation or between an artist and an organisation? What is the responsibility that you carry? How much space do you give the other? What does it mean to build this relationship? I was really happy hearing how Bakani and Shaq had touched upon my questions: it gave me a lot of insight and energy in the way wearenowrefiguringDansateliers.

At Dansateliers we now say that we only want to collaborate with artists who are willing to share their practice with others. I really believe that the instruments or tools that artists develop in their practice have a value for our daily lives. So how can we open that up, exchange that on a daily basis, and on a more human, personal level? For some years we have hosted what we call Movement Class for non-professionals, anyone who enjoys movement practices, taught by artists who are working in the house. Bakani and Shaq taught a class during their residency, which was lovely, and I got a lot of positive feedback from that. Now we are going to bring in more programmes where we have different groups in the house that could work with an artist, or engage with a practice, or just get in touch with dance and movement, slowly building them up into a bigger community.

It’s also going to be a core value that artists think about audience and context at the start of the practice. Who do you want to share the work you’re creating with? You are never out of context: we want to make that more apparent, so it’s not just coming in at the end when you have a finished show. Once a month the office team join the artists we collaborate with in the studio: we start within their movement practice and then we talk about it, to understand better what it is that they do and how we can share or find words for it. What context would lift it up? Who can we partner up with to have a bigger impact? We find moving together and exchange from body to body very important, soeverybodyinthehouseneedstobepartofthat.

It’s very inspiring for me to be in these international collaborations, thinking about our different contexts. Why do we organise ourselves in certain ways? A lot of it has to do with how the country is organised, how the funding is organised, how cities are organised – and that’s really different in each European city. When you are with international colleagues you have to really think about how you can inform somebody about these things. There are also differences in how you organise or value community dance, what kind of place it has and understanding how that works. It makes a big difference if you see community dance as a method of how we work as an organisation, instead of as a project that we do. The conversations within CROWD have helped me to form ideas about the context in this city in the Netherlands, and to find new or other strategies and questions to ask.

This article, first published in the Winter 2025 edition of Animated, is reproduced by permission of People Dancing. All Rights Reserved. See www.communitydance.org.uk/animated for more information.