7 minute read

Creating iconic IP

A huge part of Star Wars’ success over the years is the consistent experience fans have at every touch point within a world they love, understand and feel they own. From staying at the Star Wars hotel to visiting the theme park, buying the toys, watching the shows on Disney+ or attending a Secret Cinema collaboration, audiences know exactly what world they are stepping into.

Another factor that makes audiences love the world Lucas has built is the impression he has created that even if you didn’t see it, much more is happening outside the frame – and over and beyond the story originally experienced in the first release, Star Wars: Episode IVA New Hope. The very fact that it began with its fourth chapter showed the scale and scope of this world. After all, the film wasn’t called ‘Luke Skywalker’, it was about so much more than that.

A different path to worldbuilding is demonstrated by one of the most iconic entertainment IPs of the 1980s: Masters of the Universe. And the conception of musclebound protagonist He-Man and his world came about as a direct result of toy company Mattel missing out on the merchandising opportunity for the Star Wars toy line.

Stung by having turned down the (now) multi-billion dollar gift horse, which ended up in the lap of rival toy company Kenner, Mattel set out to recoup on the lost opportunity by creating He-Man and his arch nemesis Skeletor. It deliberately moulded its He-Man and Skeletor figures to be shorter than typical action hero toys at that time but bulkier than Star Wars figures. Then it pitched its creation to the top toy distributors in the US.

Child World, at the time the country’s second largest toy distributor in the US, responded to Mattel’s initial pitch with a pointed challenge: “Star Wars has a movie kids know the characters from, what have you got?” Thinking on his feet, Mark Ellis, Director of Marketing at Mattel, told them a comic book series was in the works. And the Child World execs loved that. Trouble was, Mattel had no such plan.

So now Mattel had to create a comic book series.

When work began creating the comic, it soon became clear that to build a backstory for the toys a world beyond He-Man and friends was needed. So Mattel created Eternia, home of He-Man and a central location in the world of Masters of the Universe.

Armed with a cool toy line, a backstory, the world of Eternia, an overarching name and a new comic book series that came with each figurine and full of confidence, Mattel then met with the biggest toy distributor in the US, Toys R Us. But as the presentation ended, Ellis was met with another challenging response: “You say this is suitable for under five-year-olds ... they don’t read”.

Again thinking on his feet, he replied: “Oh, did I not mention the two one-hour specials we are going to release at the same time?”

So now Mattel had to create a TV show.

A series of one-hour specials evolved into a serialised cartoon that took He-Man from a successful toy line to an 80s cultural phenomenon. And there have been multiple reboots, reimaginings, spin offs and live action films over the years since. Most recently, the late iconic worldbuilder Virgil Abloh left his own stamp on the Masters of the Universe by creating monochromatic versions of the toys complete with a similarly monochromatic comic book – a nostalgic nod to the experience he had with the world of Masters of the Universe as a child.

Robots & Stardust

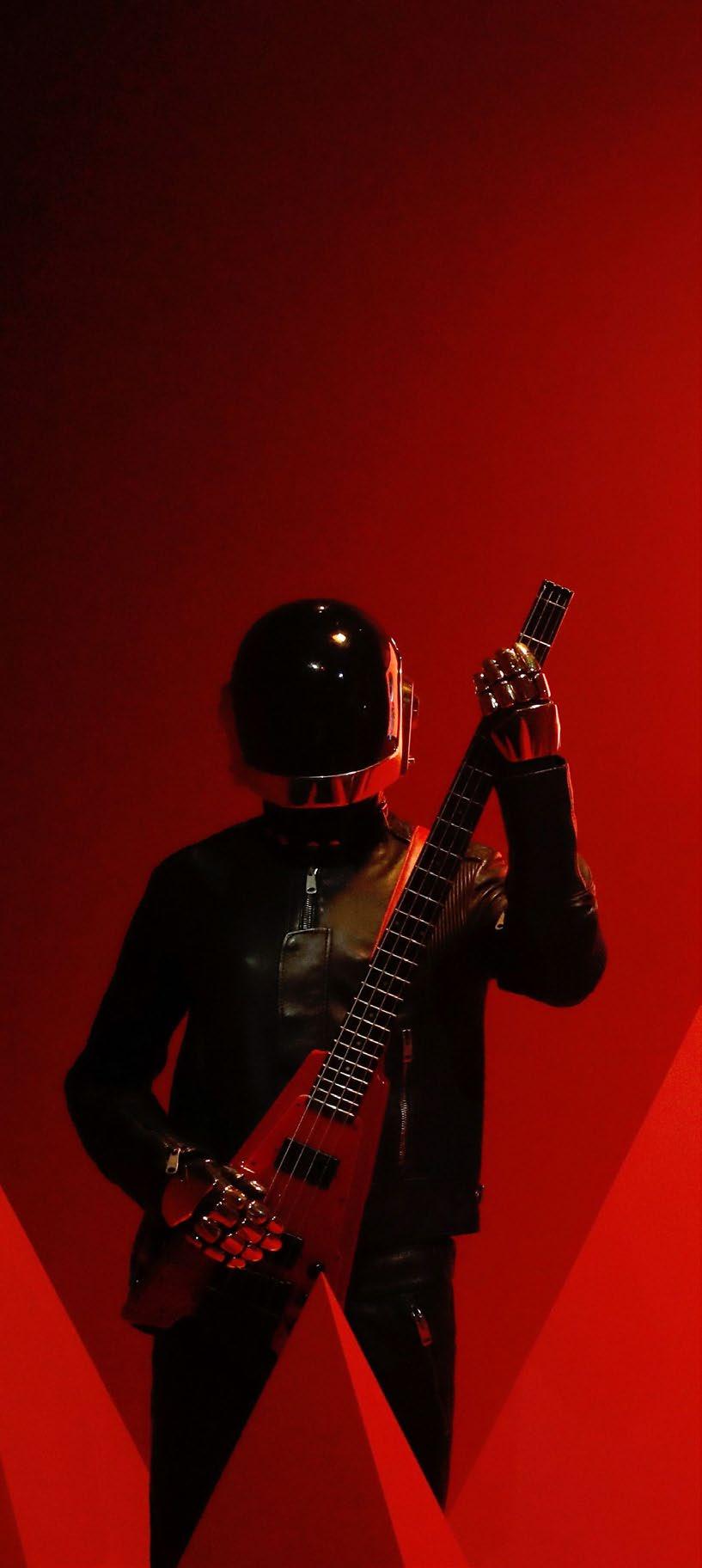

In 2001, a couple of robots appeared on the front cover of The Face magazine. Over the next two decades, these two musicians inspired and created a movement of producers and performers that hid their faces behind helmets, masks and wigs. Daft Punk built and committed to long-term robotic personas and aesthetics that would live through their music, anime music videos, live performance and cinematic scoring for Tron: Legacy. By creating a world where two robots came to life, they changed the course of the music industry.

Alternative personas and alter egos did not begin with these French electro pioneers, however. But it’s not always about doing it first – more important is doing it better than everyone else.

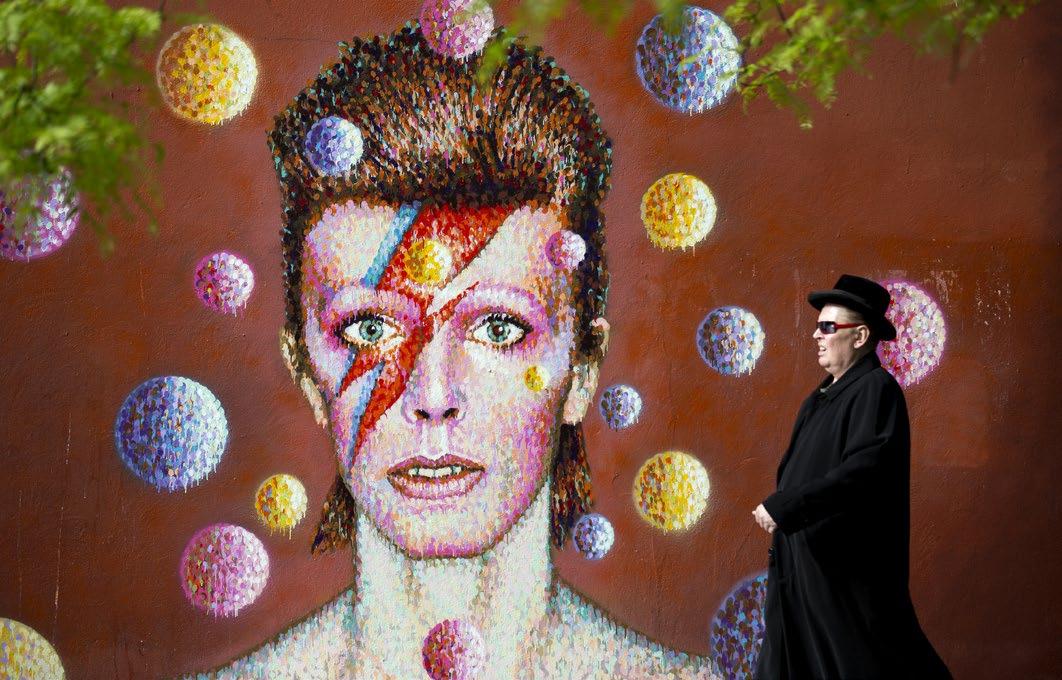

Enter David Bowie.

Style icon, musician, actor and visionary, Bowie constantly innovated in his world of creativity. Ziggy Stardust was just one of many alter egos he created, each bringing a new aesthetic and influences. This continued right up to his death, foretold by his final creation The Blind Prophet for his album Blackstar, released days before he passed. Bowie created a world that allowed him to bring his thoughts, beliefs and music to life through different characters and media as he saw it. He also saw the potential of the internet long before most people even knew what it was.

More recently, Yoann Lemoine (aka Woodkid) has combined his talents as a director, graphic designer and musician to create work that resonates with audiences on a visual level as much as audio. His stage performances reflect the worlds encapsulated by his videos, blending fashion with a sophisticated, layered musical sound accompanied by haunting vocals. As well as directing videos for Drake, Rihanna and Lana Del Rey, he has worked in the movie industry under Luc Besson and Sofia Coppola.

Best known for his 2012 hit Run Boy Run, a track that has found a second life through TikTok trends, Woodkid has constantly innovated and grown his world to celebrate his passion for multidisciplinary art forms throughout.

Image : Gaelle Marcel

Image: Francois Guillot / Contributor

Image: AFP / Stringer

Evolving Brand Worlds

The idea of ownership or collaboration with a world is truly special – and key to the evolution of a brand world.

Arguably one of the most famous brand worlds grew in 1940 from very humble beginnings... a 15-cent hamburger.

The McDonald brothers found success in drive-in restaurants having failed to make it in the movie business - a charming coincidence that underlines the impact film and entertainment has had on worldbuilding.

As the brand grew through the 1940s and 50s, the brothers ensured the architecture of their restaurants and hubs reflected the speed of their food service proposition: fast food. Real arches were part of the restaurant design and evolved into the iconic Golden Arches brand symbol.

And as the brand grew, so did its world.

Aside from the new product launches and global expansion, the brothers introduced Hamburger University in 1961 where students could graduate with a degree in ‘Hamburgerology’. And when a popular character called Bozo the Clown was rebranded as Ronald McDonald, a world was then built around himfrom comics, animation and films to videogames, park experiences and the Ronald McDonald House charity that works to improve the wellbeing of children.

Speaking of children, McDonald’s launched Happy Meals in the late 70s and fuelled the IP with further shows, partnerships and collaborations through toys and merchandise. These hubs and worldbuilding extensions continue today. Recently, McDonald’s even opened the first net zero-designed restaurant.

Whether it’s Star Wars, Pixar, or the work of its Imagineers, Disney never seems far from the subject of worldbuilding. Likewise Marvel which, under Marvel Studios boss Kevin Feige, has dominated the box office for the last decade with its well-planned out Marvel Cinematic Universe. Yet it isn’t only giant brands and corporations that are active in this space – other purveyors of entertainment and IP are also making an impact.

In 2012, an independent entertainment company was born in New York City called A24. What began as a disruptive vision to pick and produce movies that go against a trend became a brand in its own right with its own aesthetic and its own universe.

None of the films are connected in a narrative sense, but as a portfolio of work there is a consistent vision and a singularity to their output. You might not know who released Titanic or Avatar, but an A24 film is a marker of quality and something that holds a unique currency for film fans. And it’s those film fans that A24 ensures receive most of the attention around the launch of its films.

Unlike most film distribution companies, A24 doesn’t spend the majority of its marketing budget on traditional advertising, either. Instead, it focuses mostly on online marketing with social executions – a fake Tinder profile for Ava, the lead cybernetic character in Ex Machina, for example. And it invests in worldbuilding around IP – such as an 80s style board game for The Green Knight. A24 also gives fans the chance to get closer to the IPs they love through billboard screenings, auctions, podcasts, online shops and a subscription service. It’s about living the A24 lifestyle.

This is an approach that Monocle magazine has implemented beautifully for years. Reading Monocle while listening to a Monocle podcast while sipping a cup of coffee in the Monocle coffee shop is a brand world experience its audience is happy to buy into. And audiences are especially happy when brands invite them in and hand over the keys to affect their own experience or storyline - something the Secret Cinema has done successfully for over a decade.

Secret Cinema builds worlds in a more literal sense, but it is only able to do so due to the power of the worldbuilding that came before. Whether it’s eating sushi under a transparent umbrella in the rain (indoors) at Blade Runner or being chased down the street by zombies at 28 Days Later, Secret Cinema brings audiences into worlds built from existing IP that can be co-created by that audience and their experiences. In the worlds it builds, participants live their own story based on their own decisions.

And that autonomy lives on as we move into the web3 era and the metaverse. How would Tolkien have crafted Middle Earth if his audience could don VR headsets and walk through Isengard? This is an opportunity for today’s worldbuilders to explore what the forebears of the craft could only dream of.