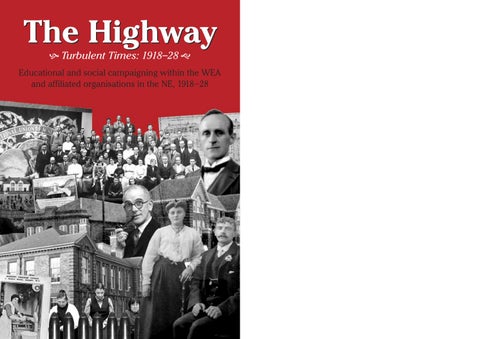

The Highway h Turbulent Times: 1918 –28 g

Educational and social campaigning within the WEA and affiliated organisations in the NE, 1918 – 28

The Highway h Turbulent Times: 1918 –28 g

Educational and social campaigning within the WEA and affiliated organisations in the NE, 1918 – 28