Masterplan Prairie House

Michael Hoffner

Shane D.Hood

Jacob Hugo

Oklahoma Historical Society

2025 Name of Grant

Executive Summary

Prairie House Preservation Society

Herb Greene Biography

Statement of Significance

The Prairie House: A Living Work of Art

The Prairie House Through the Years

Future Use

Experiencing the Site

Conditions and Conservation Objectives

Conservation Policies

Rehabilitation Standards

Rehabilitation Guidelines

Rehabilitation Narrative

Site + Context

Exterior Shell

Interior

Building Systems Rehabilitation

Scope of Work by Trade

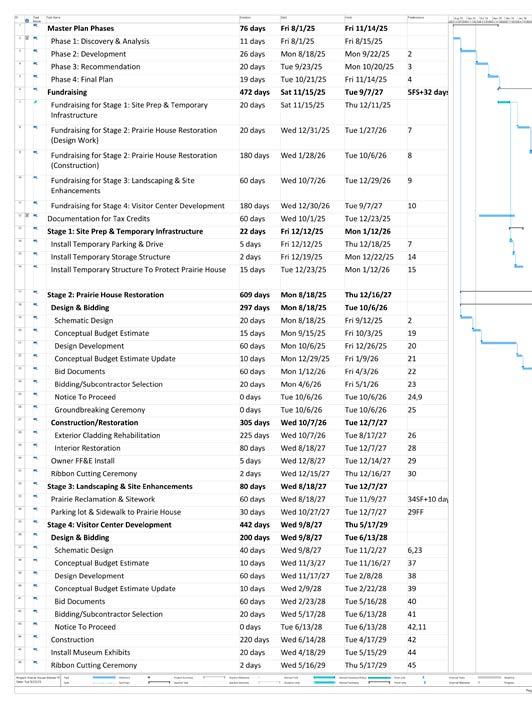

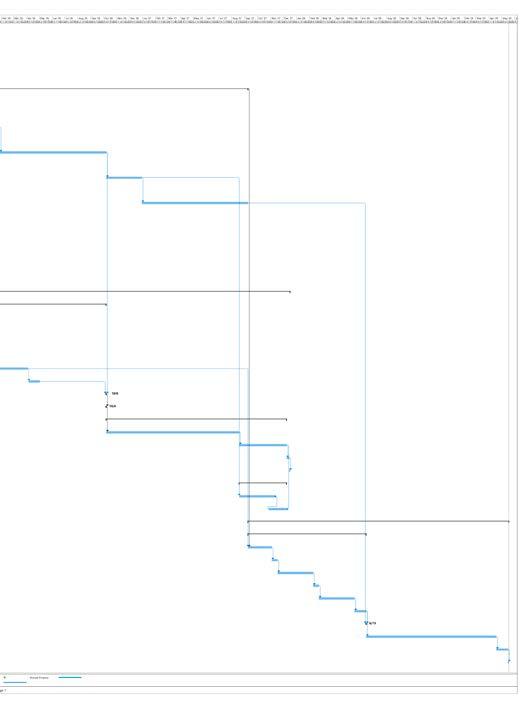

Project Delivery Comparison Schedule

Phasing

Construction

Appendices

Historical Drawings + Photos

Interview Figures and Questions

Condition Assessment Tables

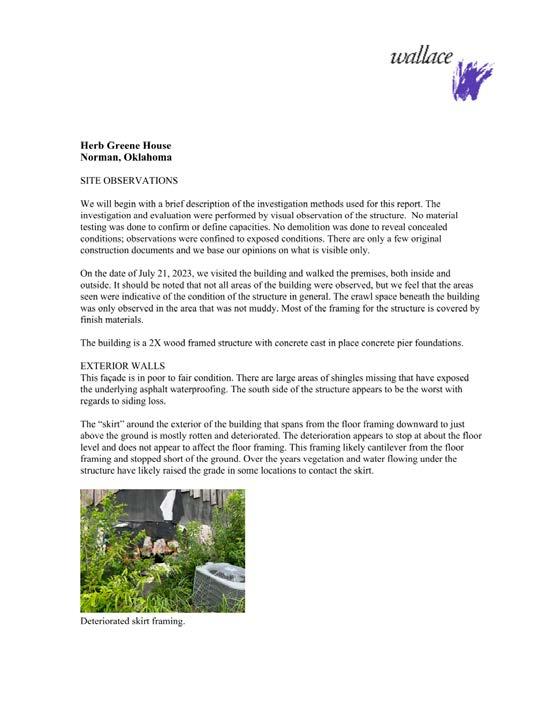

Structural + MEP Reports

Architectural Program for Phase I: House Rehabilitation

Architectural Program for Phase II: Visitor Center

Secretary of the Interior’s Standards

The Prairie House Preservation Society (PHPS) gratefully acknowledges the many individuals, organizations, and institutions whose expertise, time, and generosity made this Master Plan possible. This document builds on years of stewardship, research, and collaborative work dedicated to ensuring the longterm preservation of Herb Greene’s Prairie House.

PHPS extends deep appreciation to current and past Board members whose leadership and commitment have shaped every stage of this effort.

This Master Plan draws directly from the research and documentation completed through the Historic Structure Report (HSR), prepared collaboratively by Shane D. Hood (Align Design) and consulting partners Wallace Design Collective and Green Acorn. We extend our gratitude to Shane D. Hood, structural engineer Steven M. Huey, and MEP engineer Allen Merk, whose expertise informed the conditions assessment, treatment recommendations, and documentation that underpin this planning effort.

PHPS also acknowledges the generous support of the Ruth and Allen Mayo Fund for Historic Preservation in Oklahoma of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, whose funding made the HSR possible. Additional thanks are extended to Chuck Thompson, the Cleveland County Land Trust, Erik and Juliet Baker, and the many donors and supporters whose contributions sustain this work.

Special appreciation is extended to the Oklahoma Historical Society (OHS) for its guidance, partnership, and sustained support. PHPS has been awarded multiple OHS preservation grants, including the 2024 Heritage Preservation Grant for documenting the Prairie House’s shingle and siding system, the 2024 grant supporting the HSR, the 2025 grant enabling the Exterior Cladding Survey, and the 2025 grant funding this Master Plan. These investments provided essential baseline data and planning resources for long-term stewardship. The leadership of OHS and the expertise of the State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO) continue to strengthen PHPS’s preservation capacity and ensure alignment with state and federal standards.

We also recognize the contributions of community partners, educators, historians, tribal staff, and local organizations who engaged with PHPS through dialogue, consultation, and early program development. Their insight guided the vision and long-range goals outlined in this Master Plan, particularly as PHPS expands partnerships across the University of Oklahoma, local schools, tribal communities, and fellow historic sites.

Finally, we express our gratitude to the many volunteers, visitors, and supporters who share their time, expertise, and enthusiasm for the Prairie House. Their passion is vital to sustaining this place as a site of learning, creativity, and community for generations to come.

Preservation of Herb Greene’s Prairie House and Development of a Long-Term Master Plan

The Master Plan for the Prairie House represents a major step forward in the preservation and stewardship of one of the most significant works of Organic Modernism in the United States. Following the completion of the 2024 Historic Structure Report (HSR) and the 2025 Exterior Cladding Survey—both supported by preservation grants from the Oklahoma Historical Society (OHS)—PHPS initiated a comprehensive planning process to define a long-range strategy for conservation, restoration, education, and public engagement.

PHPS’s recent preservation work has centered on establishing strong baseline documentation. Technical studies conducted between 2023 and 2025 included detailed architectural documentation, structural and MEP assessments, wood and material analysis, and investigation of the historic shingle system. These findings provide essential data for the Master Plan.

The Master Plan draws on interdisciplinary research, archival study, landscape analysis, historic preservation planning, institutional partnerships, and consultation with specialists in architecture, engineering, ecology, and public history. Together, these efforts inform a coordinated framework for restoring the Prairie House, enhancing visitor experience, and expanding its cultural and educational role.

The primary goals of the project are to:

• Establish a long-term preservation and conservation framework that guides the treatment, care, and future restoration of the Prairie House and its surrounding landscape.

• Translate the findings of the HSR and Exterior Cladding Survey into a coordinated sequence of preservation priorities and phased implementation strategies

• Develop a coherent vision for public access, interpretation, and programming that reflects the architectural, artistic, and cultural significance of the site.

• Strengthen PHPS’s operational capacity through the development of partnerships, staffing strategies, volunteer programs, and stewardship models.

• Plan for the sustainable use of the site, including landscape management, visitor experience, revenue generation, and long-term maintenance cycles.

• Define future improvements and site infrastructure needs, including accessibility, parking, paths, signage, utilities, and support spaces.

In 2022, PHPS was founded as a nonprofit organization dedicated to stewarding the Prairie House. Recognizing the need for comprehensive planning, PHPS sought and secured multiple OHS preservation grants, including:

• 2023 - Strategic Plan

• 2024 – Historic Structure Report (HSR) funded in part by the OHS Heritage Preservation Grant

• 2025 – Exterior Cladding Survey, also supported by OHS

• 2025 – OHS Master Plan Grant, enabling the creation of this document

Throughout the planning process, PHPS worked to broaden awareness of the Prairie House and strengthen preservation capacity across local and regional networks. Key initiatives included:

• Guided tours, lectures, and educational programs centered on Organic Modernism and Herb Greene’s legacy

• Collaborative projects with architecture students, historic preservation specialists, and regional historians

• Public events, workshops, and community engagement activities

• Ongoing consultation with OHS, SHPO staff, preservation architects, engineers, and conservation specialists

The Master Plan was developed by PHPS in collaboration with:

• Shane D. Hood, — Align Design Build

• Michael Hoffner - Hoffner Design Studio

• Jake Hugo - Wayne Contracting

“The Prairie House seeks to communicate vulnerability and even pain, as well as shelter and wonder.”

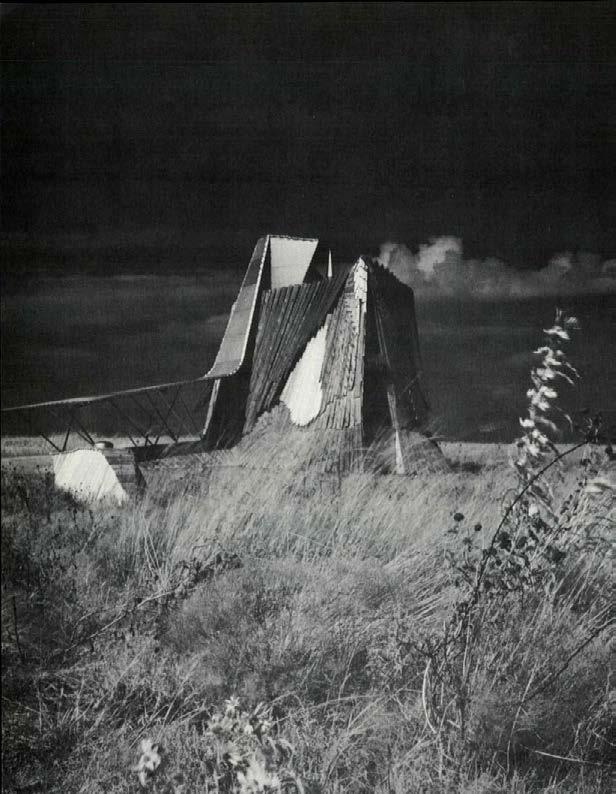

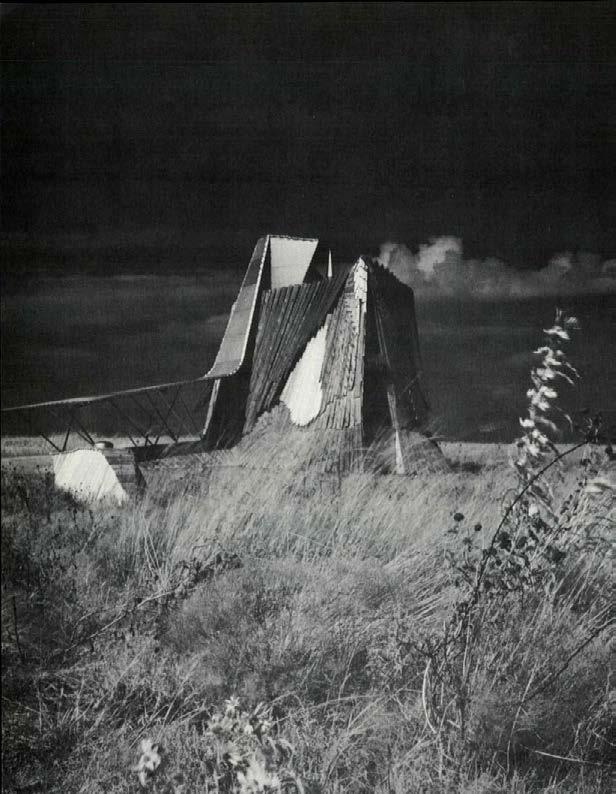

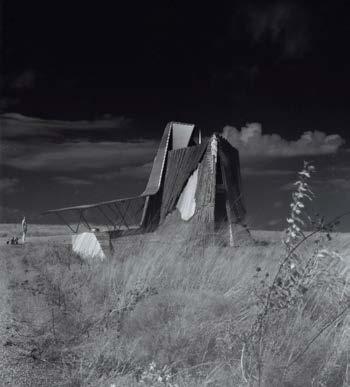

Set against the open prairie of central Oklahoma, the Prairie House stands as a vivid meeting of art, architecture, and landscape.

Designed by Herb Greene in 1961, its sculptural form captures the motion of wind and grass, translating the language of the plains into wood, stone, and light. What began as an experimental home has become an emblem of imagination rooted in place.

Today, the house faces a turning point—fragile yet full of promise. Its preservation depends on vision as much as repair: a belief that architecture can once again serve as a bridge between people and the land that sustains them. The Prairie House calls for renewal not only of its materials, but of the creative spirit that shaped it.

The Prairie House (1961), designed by Herb Greene, is an internationally recognized landmark of Organic Modernism and a defining work of Oklahoma’s creative heritage. Now endangered, it faces loss without intervention. The Prairie House Preservation Society (PHPS) is advancing critical stabilization and shaping a long-term vision to restore and reimagine the site as a cultural place where art, nature, and community meet.

The Prairie House is an internationally recognized architectural landmark, designed by Herb Greene in 1960–61. It represents a revolutionary creative counterculture movement that emerged in Oklahoma before anywhere else in the U.S. The house is a poetic expression of the Oklahoma prairie, honoring history, nature, culture, and individual expression long before those ideas gained wider traction. It is a touchstone of innovation and artistic sensibility that is disappearing in front of our eyes and must be preserved to carry its story forward.

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places and currently on Preservation Oklahoma’s Most Endangered List, the house stands at a critical crossroads: either we act now to protect it, or it risks the same fate as other lost masterpieces of organic modernism, like the Bavinger House.

In the near term, our focus is on securing the Prairie House so that it may once again welcome people into its extraordinary spaces. Essential safety and comfort repairs will allow limited public access, while protective measures, such as re-grading to direct water away from the foundation and constructing a temporary shelter to shield the structure from sun, wind, and rain, will slow deterioration. These interim steps will safeguard the building and create breathing room as we complete the master plan and prepare for full restoration.

Our long-term vision reaches far beyond preservation. The Prairie House will emerge as a living work of art and a cultural nexus where art, nature, and community converge. Here, visitors will encounter not only the architectural poetry of Herb Greene’s design but also exhibitions, performances, and programs that extend its spirit. The house will host tours, storytelling, and rotating exhibitions; interdisciplinary workshops linking the arts, science, and philosophy; andgatherings in the restored prairie landscape for walks, lectures, and intimate performances. This transformation will unfold in two phases: first, the stabilization and rehabilitation of the house and its landscape; and second, the construction of a visitor center to accommodate needs the house itself cannot—bathrooms, gallery and event spaces, conference rooms, and storage. Together, these efforts will position the Prairie House as both a preserved landmark and a dynamic cultural center, alive with exchange and discovery.

The PHPS is composed of passionate individuals racing against time to save the house. The PHPS is supported by a large local, state, national, and international community invested in its survival. Preserving the Prairie House will demonstrate Oklahoma’s dedication to protecting its cultural and creative history. It is Oklahoma’s Fallingwater: a singular architectural treasure that will continue inspiring generations to come.

Founded in 2022, the Prairie House Preservation Society (PHPS) preserves Herb Greene’s iconic 1960–61 Prairie House in Norman, Oklahoma. Through tours, events, and educational programs, PHPS celebrates Greene’s iconic masterwork and inspires community engagement. Board members are featured on the adjacent page.

The Prairie House Preservation Society (PHPS) is a 501(c) 3 nonprofit organization, formed in January of 2022, to ensure the restoration, preservation and development of the Prairie House (1960-61), designed and built by architect Herb Greene in Norman, Oklahoma.

The PHPS makes the house accessible to the community through public tours and special events, geared towards enriching the cultural landscape of Norman and to build awareness around the critical need to preserve the endangered historic architecture.

The PHPS endeavors to inspire a deeper understanding and appreciation of Oklahoma’s rich heritage by engaging the community and providing educational experiences centered around the architectural and cultural significance of the site.

Herb Greene, a student of Bruce Goff, is an innovative architect and educator known for his Prairie House (1961) and residential work that expresses client personality, site, and materials. Beyond architecture, Greene is a prolific collage artist and author who promotes integrating art into building, with his writings and artworks widely published and collected.

Herb Greene studied architecture under the direction of Bruce Goff (1904–1982), one of the nation’s most original architects and influential architectural educators. During and after school, Greene worked for Goff preparing numerous presentation drawings, which are now part of the Art Institute of Chicago’s collection. Greene also worked for architect John Lautner (1911–1994), who was one of Frank Lloyd Wright’s original apprentices. Following the retirement of Goff in 1957, Greene taught architecture at the University of Oklahoma for six years in order to continue his teacher’s legacy. During this period, Greene also designed and built houses of significant historic interest before moving to Lexington, Kentucky, where he continued to work and teach for eighteen years.

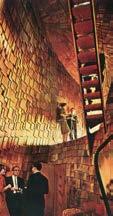

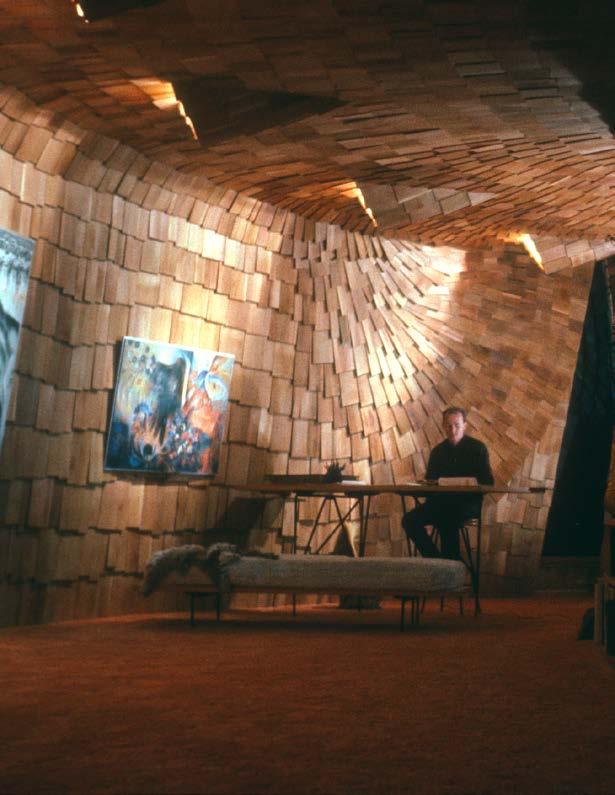

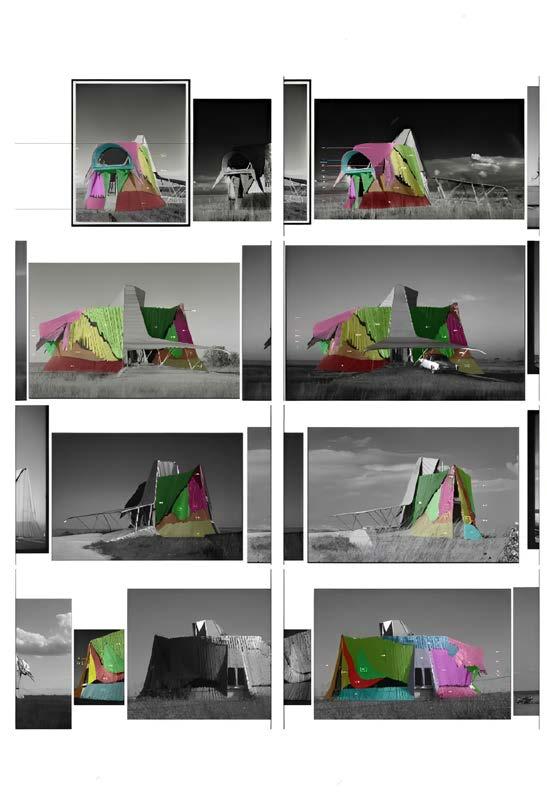

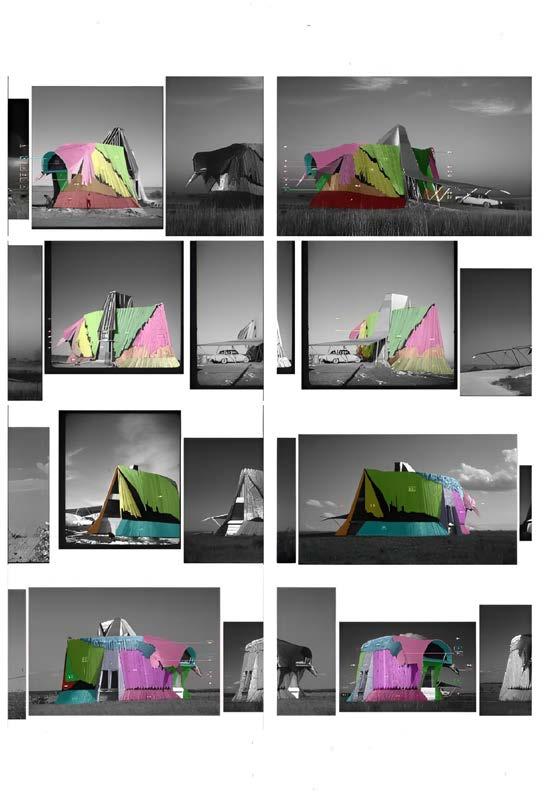

In 1961, Greene designed and built his Prairie House in Norman, Oklahoma. The idiosyncratic and innovative architecture of Greene’s Prairie House caused an international sensation and was published in Life and Look magazines, Progressive Architecture (St. Martin’s Press), and numerous journals throughout Europe and Japan. Greene’s residential work, following Goff’s architectural philosophy, is an expression of the client’s existential qualities (personality and physiognomy), as well as conditions related to site, region, and the nature of materials. In addition to architectural work, Greene makes collage paintings as an exploration of existential philosophy and the power of images on the human psyche.

After his retirement from teaching in 1982, Greene moved to Berkeley, California where he continues to write, paint, and promote his concept for building with artists. In 1981, Greene published the book Building to Last: Architecture as Ongoing Art (Architectural Book Publishing, 1981), which advocates incorporating the work of artists and crafts people into architecture in order to increase perceptual richness and history in an architectural form. Greene’s architectural drawings are in The Art Institute of Chicago’s collection alongside works by Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright, Bruce Goff, and other works in the “Prairie Tradition.” Greene’s collage paintings are also in The Art Institute of Chicago’s collection, as well as numerous private collections across the United States. Greene’s writing has been widely published, including his books Mind & Image (The University Press of Kentucky, 1976), Painting the Mental Continuum: Perception and Meaning in the Making (Berkeley Hills Books, 2003), and Generations: Six Decades of Collage Art and Architecture Generated with Perspectives from Science (Oro Editions, 2015).

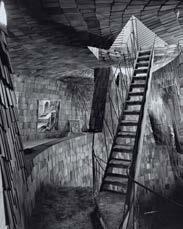

On the edge of Norman, Oklahoma, nestled in the tallgrass and sky, stands a house unlike any other. The Prairie House, designed in 1961 by architect Herb Greene, is not simply a building—it is a living work of art. Its soaring, sculptural form seems to grow from the earth itself, echoing the rhythms of wind, land, and imagination. Long celebrated in the history of modern architecture, the Prairie House remains an unaltered masterpiece of organic design, studied by generations of architects and admired around the world.

But its greatest power lies in how it feels to those who experience it. Stepping inside is to enter a place where art and life converge, where architecture becomes poetry, and where visitors are reminded that creativity can be both daring and deeply human.

The Prairie House Preservation Society (PHPS) was founded to protect this extraordinary landmark and to share it with the public as a catalyst for culture, learning, and inspiration. PHPS envisions the house not as a relic to be admired at a distance, but as a living resource: a site for exhibitions, events, performance, and community gatherings that spark new connections across architecture, nature and the arts.

This vision depends on stewardship. Preserving a building of such expressive originality requires care, expertise, and resources. By joining us, you become part of a legacy, ensuring that the Prairie House will continue to inspire wonder, foster dialogue, and stand as a beacon of imagination for generations to come.

On the edge of Norman, Oklahoma, nestled in the tallgrass and sky, stands a house unlike any other. The Prairie House, designed in 1961 by architect Herb Greene, is not simply a building—it is a living work of art. Its soaring, sculptural form seems to grow from the earth itself, echoing the rhythms of wind, land, and imagination. Long celebrated in the history of modern architecture, the Prairie House remains an unaltered masterpiece of organic design, studied by generations of architects and admired around the world.

But its greatest power lies in how it feels to those who experience it. Stepping inside is to enter a place where art and life converge, where architecture becomes poetry, and where visitors are reminded that creativity can be both daring and deeply human.

The Prairie House Preservation Society (PHPS) was founded to protect this extraordinary landmark and to share it with the public as a catalyst for culture, learning, and inspiration. PHPS envisions the house not as a relic to be admired at a distance, but as a living resource: a site for exhibitions, events, performance, and community gatherings that spark new connections across architecture, nature and the arts.

This vision depends on stewardship. Preserving a building of such expressive originality requires care, expertise, and resources. By joining us, you become part of a legacy—ensuring that the Prairie House will continue to inspire wonder, foster dialogue, and stand as a beacon of imagination for generations to come.

BY LINES

The Prairie House presented through historic drawings, photos and timeline of significant moments

1950-1953

Works intermittently in Bruce Goff’s office in Bartlesville; also gains experience with John Lautner (Los Angeles) and Joseph Krakower (Houston).

1953

1929

Herb Greene (Herbert Ronald Greenberg) is born in Oneonta, New York.

1947

Begins studies at Syracuse University.

1948

Transfers to the University of Oklahoma to study architecture under Bruce Goff.

Graduates with a Bachelor of Architecture from the University of Oklahoma.

1957

Joins OU architecture faculty, serving as Assistant Professor until 1963.

1960-1961

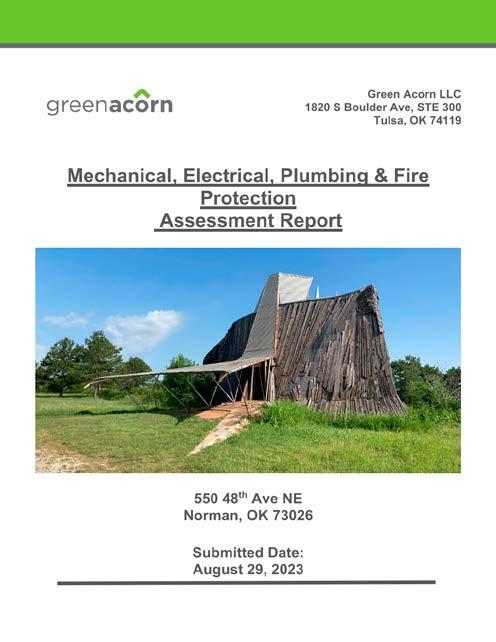

Designs and builds the Prairie House in Norman, Oklahoma, as his family home. Prairie House gains international attention through publications in Life and Look magazines, as well as architectural journals in Europe and Japan.

1962

Leaves OU to teach at the University of Kentucky (faculty through 1982).

1965

Designs notable works during his Kentucky period, including the Lexington Unitarian Church.

1968

Sells the Prairie House. Longtime owner Janie Wilson acquires the property.

1970-1980s 2000s

1976

Publishes Mind & Image: An Essay on Art and Architecture.

1981

Publishes Building to Last: Architecture as Ongoing Art.

1982

Retires from teaching; relocates to Berkeley, California. Expands focus on painting, writing, and interdisciplinary collaboration.

2003

Publishes Painting the Mental Continuum: Perception and Meaning in the Making.

2015

Co-authors Generations: Six Decades of Collage Art and Architecture Generated with Perspectives from Science with Lila Cohen.

2016

Janie Wilson dies (January). Ownership of the Prairie House passes to her estate.

2016-2017

The house is sold to preservationists Brent Swift and partner. Restoration efforts begin.

2017

Herb Greene visits Norman to advise on preservation efforts at his former home.

2020s

2021

The Prairie House Trust acquires the property, securing long-term preservation.

2022

Prairie House Preservation Society (PHPS) is founded as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit to steward the house, oversee restoration, and promote public engagement.

2024

Prairie House Preservation Society (PHPS) completes a Historic Structure Report in conjunction with a grant from the Oklahoma Historic Society (OHS).

2025

Prairie House Preservation Society (PHPS) completes an Exterior Cladding Survey in conjunction with a grant from the Oklahoma Historic Society (OHS).

2025

Prairie House Preservation Society (PHPS) is awarded a grant to complete a Masteplan by the Oklahoma Historical Society (OHS).

The word “programming” is used here in the sense of planned activities, functions, public offerings, etc. Initially a house museum and ultimately a cultural hub, there is a plan for the programming at the Prairie House.

The Prairie House will initially operate as a house museum, offering visitors opportunities to engage with the site through salons, concerts, performances, and other programs that connect art, architecture, and ecology. In later stages of development, a new Visitors Center will greatly expand these capabilities.

At the outset, the Prairie House will function as a small-scale museum where a multi-role staff balances public engagement with behindthe-scenes tasks such as administration and routine maintenance. Comparable house museums of similar architectural stature typically operate four or five days per week, with at least one weekend day. For example, the Farnsworth House in Plano, Illinois, is open Wednesday through Sunday from 9:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. and generally offers three guided tours per day for groups of 10–20 visitors.

The Prairie House’s operating schedule will evolve through experimentation to find the right balance. Initially, the house could open Thursday through Sunday from 9:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m., staffed by a half-time Executive Director and volunteer docents. Two daily guided tours—at 10 a.m. and 2 p.m.—would provide structured public access while allowing flexibility for other duties. Special events, such as concerts, could take place outside regular hours to preserve the contemplative experience of visitors appreciating the architecture and site.

In future phases, the addition of a fully accessible Visitors Center with extended hours will significantly increase the site’s capacity and protect the house itself from overuse. Exhibitions, lectures, classes, symposia, and other special events will broaden the audience and transform the Prairie House into a lively cultural hub. PHPS envisions an expanding range of initiatives, including architectural and art fellowships, community events, coordinated research programs, and collaborations with the University of Oklahoma.

When completed, the Visitors Center will serve as the starting point for guided tours, its architecture and site design enhancing the sense of approach and anticipation upon arrival at the Prairie House.

In summary, the restored Prairie House will begin as a house museum with light programming on the property. With the eventual addition of the Visitors Center, it will evolve into a fully accessible center for cultural exchange, research, and creative engagement.

This drawing illustrates the work proposed for this phase and indicates more exciting enhancements to come in future phases.

A series of moments showing how architecture and landscape come back into balance.

The Serial Vision Tour presents a sequence of views that describe how visitors will experience the restored Prairie House site. Each perspective reveals the evolving relationship between the house, the prairie, and the paths that connect them. Moving from the visitor center through shifting light and terrain, the journey frames the architecture within its natural context and highlights the renewed dialogue between structure and landscape. Together, these moments illustrate how careful restoration can recover both the spirit and the setting of Herb Greene’s design, allowing the house to be seen once again as part of the living prairie.

Rediscovered in quiet light.light.

Seen first through the glass of the new visitor center, the Prairie House rises from the surrounding grasses as if rediscovered by the land itself. The view is intentional, framing the house within a broad field that recalls the openness of the original prairie. Though the site is now bounded by trees at its edges, the house continues to read as a form shaped by light and land. This first glimpse reintroduces the essential connection between architecture and landscape, a relationship that restoration will bring fully back to life.

Glimpsed through trees and shadow.

Leaving the visitor center, visitors follow a path that bends east toward a stand of trees. Through shifting light, the house appears again in partial view, softened by the rhythm of trunks and movement of wind. The ground begins to rise and the prairie becomes more defined underfoot. This is a moment of transition, where enclosure gives way to openness and the landscape begins to speak again.

The land opens wide.

Emerging from the tree line, the prairie opens wide and unbroken ahead. The visitor pauses at a point of decision, choosing either the narrative path that winds through the restored landscape or the direct route toward the house. The geometry of the site becomes clear in this open ground, and the house stands centered within it, visible yet still at a distance, grounded in its original horizon.

The house meets its ground.

The original drive leads the visitor toward the granite ramp and carport that define the entrance to the house. The southern façade begins to reveal itself, layered in weathered wood, metal, and shadow against the existing trees beyond. Here the site still feels contained, the southern edge pressing close around the house. As restoration progresses and the treeline gives way to open prairie, this approach will regain its intended clarity and sense of release.

Light warms the waking prairie.

From the northern path, the house meets the first light of morning. Sun strikes the weathered siding, turning the muted grain to soft gold as the prairie begins to shimmer in movement. The house rests quietly within this light, its form and material renewed by the surrounding landscape. It is a scene of balance and restoration, where architecture once again belongs to the rhythm of the land.

Time folds into light.

Late in the day, the western field glows beneath a warm autumn sky. The house stands calmly within the fading light, its surfaces reflecting the color of the setting sun. A photographer pauses on the path, recording a moment that feels suspended between past and future. The house, the land, and the future visitor center all share this horizon, unified by the steady light of evening.

The prairie endures still.

In late fall, the prairie shifts to bronze and pale gold, and the grasses move gently in the cooling air. A couple walks the final stretch of the path, approaching the house as twilight deepens. Even in dormancy, the landscape remains vital and expressive, revealing beauty in its seasonal change. The house stands quietly within it, enduring and timeless, a reminder that the dialogue between place and design continues through every season.

“The idea was to relate the house to the prairies itself.”

The Prairie House belongs wholly to its landscape. Set within the rolling plains northeast of Norman, it rises from the earth as if shaped by wind and time. The gentle slope, the shifting grasses, and the wide horizon are integral to its form and feeling, architecture and prairie completing one another. Even as encroaching cedar and nearby development have softened the vastness that once surrounded it, the land retains the quiet rhythm and spaciousness that inspired its creation.

This chapter situates the house within that evolving landscape, its orientation to sun and sky, its relationship to native ecology and history, and its potential for renewal. In restoring both the structure and the site, the goal is to recover the sense of emergence and wonder that made the Prairie House inseparable from its setting.

“Conservation is about understanding the context of time and place, the objectives of when a building was originally built. If we can keep these resources relevant for today and the future, and my involvement isn’t apparent, I’ve been successful. “Kelly Sutherlin McLeod on her restoration of the 1953 Hafley house by Richard Neutra in Long Beach, California.

The structure is in fair to good condition overall but faces critical issues from water infiltration, material aging, and landscape alterations. Objectives include replacing deteriorated cedar cladding, sealing the envelope, stabilizing structural components (notably the skirting and carport). Landscape rehabilitation is required to restore original prairie conditions and improve water shed.

The level of rehabilitation or restoration needs to be established. As preservationists, our goal and philosophy is to retain the highest level of authenticity possible. This means:

• Retaining as much of the 1961 fabric and features as possible

• Replicate missing elements where adequate information exists

• Using austere, non-distracting stand-ins where adequate information does not exist

• Improvements to systems and technology should be as invisible as possible

• Avoid over-restoring or deviating from what actually got built in 1961 and eschew adding features that “could have been,” or represent never-constructed features.

•Where interventions are necessary, they should “self describe” while being as non-distracting as possible

The Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties provide guidance on preserving, rehabilitating, restoring, and reconstructing historic buildings while protecting their significance and integrity. They help determine whether rehabilitation projects qualify for federal incentives and ensure consistency in preservation practices across federal, state, and local levels.

The Secretary of the Interior’s Standards serve as foundational principles to guide historic preservation projects across the United States, ensuring that the cultural and architectural significance of historic properties is respected and maintained. These Standards exist within two regulatory frameworks:

• 36 CFR Part 67- Rehabilitation Standards for Tax Incentives which specifically addresses Rehabilitation and is used to assess eligibility for federal Historic Preservation Tax Incentives.

• 36 CFR Part 68 - Treatment of Historic Properties which governs the broader Treatment of Historic Properties, including preservation, rehabilitation, restoration, and reconstruction.

These Standards apply broadly to historic sites of all types, regardless of materials, size, or occupancy, and adress both interior and exterior features, landscapes, related environments, and thoughtfully designed new additions.

Understanding the regulatory context is essential, as the Standards influence multiple aspects of project planning and execution:

• Federal Historic Preservation Tax Incentives require compliance with the Rehabilitation Standards.

•Federal and State grant programs rely on the Standards to evaluate project eligibility and appropriateness.

• Local preservation authorities use the Standards as the basis for decisions regarding alterations, additions, and site work.

• Professional practice follows the Standards as the shared framework for ensuring consistency, quality, and integrity in treatment decisions.

For PHPS, the Standards shape both near-term rehabilitation work and long-term stewardship, ensuring that decisions align with national best practices and support the House’s continued eligibility for financial incentives and preservation protections.

The Standards are grouped under four treatment strategies, each serving a different preservation goal:

• Preservation emphasizes maintaining and repairing existing historic

materials and character with minimal change.

• Rehabilitation supports adapting historic buildings for new or ongoing use while preserving defining features.

• Restoration seeks to return a property to its appearance during a specific historical period, removing incongruent additions.

• Reconstruction involves recreating lost structures or features based on sufficient documentation, often for interpretive purposes.

Choosing an appropriate treatment depends on factors such as the building’s historical significance, intended future use, documentation available, and economic or technical feasibility. 1.4 Philosophy & Application

The Standards advocate a “least harm” approach, preserving as much authenticity as possible. They serve as a unifying framework for professionals and reviewers rather than prescriptive rules. Different treatments may be combined, but selecting a primary approach ensures clarity throughout a project.

Of the four treatment approaches, Rehabilitation is the most appropriate for the Prairie House. The project goals include:

Addressing deterioration and system deficiencies

Ensuring life-safety and functional performance

Supporting ongoing and future use of the House

Preserving the architectural and artistic character of the original design

Allowing necessary upgrades that remain compatible with the historic fabric

Rehabilitation offers the flexibility needed to sustain Herb Greene’s artistic intent while enabling PHPS to meet contemporary functional, safety, and accessibility requirements. It also aligns with eligibility requirements for the Federal Historic Preservation Tax Incentives that can support project funding.

The Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties provide guidance on preserving, rehabilitating, restoring, and reconstructing historic buildings while protecting their significance and integrity. They help determine whether rehabilitation projects qualify for federal incentives and ensure consistency in preservation practices across federal, state, and local levels.

1. New Use Respecting Original Character

A property will be used as it was historically or be given a new use that requires minimal change to its distinctive materials, features, spaces and spatial relationships.

2. Retain Historic Character

The historic character of a property will be retained and preserved. The removal of distinctive materials or alteration of features, spaces and spatial relationships that characterize a property will be avoided.

3. Physical Record of Time and Place

Each property will be recognized as a physical record of its time, place and use. Changes that create a false sense of historical development, such as adding conjectural features or elements from other historic properties, will not be undertaken.

4. Respect Later Historical Layers

Changes to a property that have acquired historic significance in their own right will be retained and preserved.

5. Preserve Craftsmanship and Materials

Distinctive materials, features, finishes, and construction techniques or examples of craftsmanship that characterize a property will be preserved.

6. Repair Before Replace

Deteriorated historic features will be repaired rather than replaced. Where the severity of deterioration requires replacement of a distinctive feature, the new feature will match the old in design, color, texture and, where possible, materials. Replacement of missing features will be substantiated by documentary and physical evidence.

7. Gentle Treatment of Surfaces

Chemical or physical treatments, if appropriate, will be undertaken using the gentlest means possible. Treatments that cause damage to historic materials will not be used.

8. Protect Archaeological Resources

Archeological resources will be protected and preserved in place. If such resources must be disturbed, mitigation measures will be undertaken.

9. Compatible Additions

New additions, exterior alterations, or related new construction will not destroy historic materials, features, and spatial relationships that characterize the property. The new work will be differentiated from the old and will be compatible with the historic materials, features, size, scale and proportion, and massing to protect the integrity of the property and its environment.

10. Reversible Design

New additions and adjacent or related new construction will be undertaken in such a manner that, if removed in the future, the essential form and integrity of the historic property and its environment would be unimpaired.

The Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties provide guidance on preserving, rehabilitating, restoring, and reconstructing historic buildings while protecting their significance and integrity. They help determine whether rehabilitation projects qualify for federal incentives and ensure consistency in preservation practices across federal, state, and local levels.

In Rehabilitation, historic building materials and character-defining features are protected and maintained as they are in the treatment Preservation. However, greater latitude is given in the Standards for Rehabilitation and Guidelines for Rehabilitating Historic Buildings to replace extensively deteriorated, damaged, or missing features using either the same material or compatible substitute materials. Of the four treatments, only Rehabilitation allows alterations and the construction of a new addition, if necessary for a continuing or new use for the historic building

Materials and Features The guidance for the treatment Rehabilitation begins with recommendations to identify the form and detailing of those architectural materials and features that are important in defining the building’s historic character and which must be retained to preserve that character. Therefore, guidance on identifying, retaining, and preserving character-defining features is always given first.

After identifying those materials and features that are important and must be retained in the process of rehabilitation work, then protecting and maintaining them are addressed. Protection generally involves the least degree of intervention and is preparatory to other work. Protection includes the maintenance of historic materials and features as well as ensuring that the property is protected before and during rehabilitation work. A historic building undergoing rehabilitation will often require more extensive work. Thus, an overall evaluation of its physical condition should always begin at this level.

Next, when the physical condition of character-defining materials and features warrants additional work, repairing is recommended. Rehabilitation guidance for the repair of historic materials, such as masonry, again begins with the least degree of intervention possible. In rehabilitation, repairing also includes the limited replacement in kind or with a compatible substitute material of extensively deteriorated or missing components of features when there are surviving prototypes features that can be substantiated by documentary and physical evidence. Although using the same kind of material is always the preferred option, a substitute material may be

an acceptable alternative if the form, design, and scale, as well as the substitute material itself, can effectively replicate the appearance of the remaining features.

Following repair in the hierarchy, Rehabilitation guidance is provided for replacing an entire character-defining feature with new material because the level of deterioration or damage of materials precludes repair. If the missing feature is character defining or if it is critical to the survival of the building (e.g., a roof), it should be replaced to match the historic feature based on physical or historic documentation of its form and detailing.

As with repair, the preferred option is always replacement of the entire feature in kind (i.e., with the same material, such as wood for wood). However, when this is not feasible, a compatible substitute material that can reproduce the overall appearance of the historic material may be considered. It should be noted that, while the National Park Service guidelines recommend the replacement of an entire character-defining feature that is extensively deteriorated, the guidelines never recommend removal and replacement with new material of a feature that could reasonably be repaired and, thus, preserved.

When an entire interior or exterior feature is missing, such as a porch, it no longer plays a role in physically defining the historic character of the building unless it can be accurately recovered in form and detailing through the process of carefully documenting the historic appearance. If the feature is not critical to theurvival of the building, allowing the building to remain without the feature is one option. But if the missing feature is important to the historic character of the building, its replacement is always recommended in the Rehabilitation guidelines as the first, or preferred, course of action. If adequate documentary and physical evidence exists, the feature may be accurately reproduced. A second option in a rehabilitation treatment for replacing a missing feature, particularly when the available information about the feature is inadequate to permit an accurate reconstruction, is to design a new feature that is compatible with the overall historic character of the building. The new design should always take into account the size, scale, and material of the building itself and should be clearly differentiated from the authentic historic features. For properties that have changed over time, and where those changes have acquired significance, reestablishing missing historic features generally should not be undertaken if the missing features did not coexist with the features currently on the building. Juxtaposing historic features that did not exist concurrently will result in a false sense of the building’s history.

Some exterior and interior alterations to a historic building are generally needed as part of a Rehabilitation project to ensure its continued use, but it is most important that such alterations do not radically change, obscure, or destroy character-defining spaces, materials, features, or finishes. Alterations may include changes to the site or setting, such as the selective removal of buildings or other features of the building site or setting that are intrusive, not character defining, or outside the building’s period of significance.

Sensitive solutions to meeting code requirements in a Rehabilitation project are an important part of protecting the historic character of the building. Work that must be done to meet accessibility and life-safety requirements must also be assessed for its potential impact on the historic building, its site, and setting.

Resilience to natural hazards should be addressed as part of a Rehabilitation project. A historic building may have existing characteristics or features that help to address or minimize the impacts of natural hazards. These should always be used to best advantage when considering new adaptive treatments so as to have the least impact on the historic character of the building, its site, and setting.

Sustainability should be addressed as part of a Rehabilitation project. Good preservation practice is often synonymous with sustainability. Existing energy-efficient features should be retained and repaired. Only sustainability treatments should be considered that will have the least impact on the historic character of the building.

Rehabilitation is the only treatment that allows expanding a historic building by enlarging it with an addition. However, the Rehabilitation guidelines emphasize that new additions should be considered only after it is determined that meeting specific new needs cannot be achieved by altering non-character-defining interior spaces. If the use cannot be accommodated in this way, then an attached exterior addition may be considered. New additions should be designed and constructed so that the character-defining features of the historic building, its site, and setting are not negatively impacted. Generally, a new addition should be subordinate to the historic building. A new addition should be compatible, but differentiated enough so that it is not confused as historic or original to the building. The same guidance applies to new construction so that it does not negatively impact the historic character of the building or its site.

Rehabilitation treatments include removal of invasive vegetation, replacement of deteriorated siding, roof and drainage system redesign, and in-kind repair or replacement of windows and doors as appropriate. Interior repairs include restoration of cork and granite flooring, installation of carpeting; tuning up door and cabinetry operation, attending to cedar surfaces, and mechanical systems. The grounds require regrading to redirect water, removal of a problematic pond, removal of Bermuda and re-establishment of prairie grasses.

The rehabilitation of the Prairie House will address both building fabric and site conditions to ensure long-term preservation of Herb Greene’s 1961 landmark while allowing for safe, functional public use. Treatments are designed to retain historic integrity and authenticity while correcting deficiencies that threaten the structure and landscape.

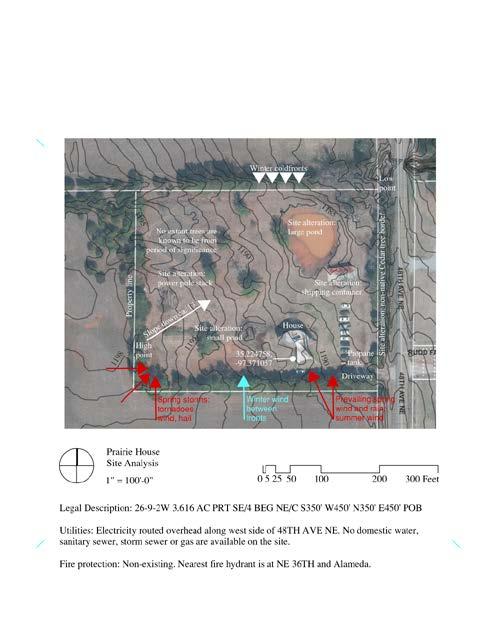

The immediate grounds will undergo selective clearing to remove invasive vegetation and interloping trees that obscures the original character of the prairie site. Non-native species, particularly Bermuda grass, will be eradicated and replaced with native prairie grasses, consistent with the house’s original integration into its landscape. Cedar trees, though unoriginal to the site, now serve the function of screening out development that has occurred around the site, on neighboring property whose development is currently out of PHPS control. However, the trees that are within that cedar perimeter, none of which are original and are diminishing of the site’s prairie character are to be removed. The large pond may be removed if funding allows, however the existing small pond near the house must be removed as soon as possible. Introduced after the period of significance, the small pond is currently contributing to the undermining of soils near and beneath the structure—will be removed, and the site will be regraded to establish positive drainage away from the house. These interventions will reduce moisture infiltration, mitigate erosion at the foundations, and make progress towards restoring the historic ecological character of the site.

The exterior cladding, a defining feature of the house, exhibits wideranging deterioration requiring in-kind replacement of all siding. Care will be taken to preserve as much original sheet metal and other exterior materials as feasible. The roofing system must be replaced to faithfully replicate the original detailing around the tops of walls. The building has suffered from roof run-off draining down the surfaces of walls and the new roof will incorporate the latest technology and a sensitively incorporated drainage system that will directly discharge water from the roof while respecting the house’s sculptural roofline. Improved technology will also be deployed on the exterior walls as advances in waterproofing and drainage plane technology can be hidden from view while increasing the lifespan and performance of the exterior wall finishes. Windows and doors will be repaired and re-used where possible and original to design.

Custom cedar screen door and entry door will be replicated as closely as possible based on interviews and historic photos. Windows will be evaluated individually: deteriorated components will be repaired where possible, and when beyond repair, replaced in kind with materials and profiles matching the originals. Consideration will be given to removing the replacement windows at the ventilation flaps with replica units as close to original design as can be determined. Hardware will be retained and refurbished wherever feasible.

Interior finishes and fixtures, many custom-designed by Greene, will be carefully conserved. Non-extant cork flooring will be replicated as closely as practical. Granite flagstone floors will be cleaned and sealed. Carpeting will be reinstalled in areas where Greene specified textile floor covering, referencing original color and weave as according to documentation and historic photos – stair tread and floor edges should be examined for traces of original carpet yarns that could help recreate the carpet’s color and yarn gauge. Cabinetry and built-in doors will be tuned for smooth operation, with repairs to hinges, pulls, and sliders undertaken using preservation-sensitive methods. Cedar surfaces—including walls and ceilings—will be gently cleaned, treated for biological growth if present. Areas with missing or badly damaged shingles should be evaluated as to whether repair constitutes the risk of further, damage, breakage or distracting color mis-match. Where applicable, consider painting or staining replacement wood to match existing. Water stains are considered to be part of the building’s story and should not be considered “damaged” solely because of discoloration. It is further proposed that furniture, fixtures and decorations chosen to match historic records could be discretely added to the space to aid in visitors’ understanding of how the house functioned. Rounding it out, a vintage stove and refrigerator are proposed to add context to the kitchen. More research is needed to determine whether they can be updated and maintained in working condition or simply exist as interpretive elements. If desired, other appliances could be evaluated for safety and compatibility, but clutter and too many artifacts should be avoided.

Mechanical, electrical, and plumbing systems will be upgraded to modern standards in a manner that minimizes visual impact. The furnace and AC compressor will be replaced with efficient, code-compliant equipment, and ductwork will be serviced to improve cleanliness and performance— however, preventing damage to the architectural fabric is prioritized over incremental improvements to HVAC systems. Plumbing systems, including piping, toilets, and faucets, will be inspected and repaired or replaced as needed to ensure reliable function. Ventilation systems—particularly the exhaust fan and roof-adjacent ventilation fan—will be serviced or

replaced to provide adequate indoor air quality without altering historic surfaces.

All rehabilitation treatments will follow the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Rehabilitation. Retention of original material is prioritized over intervention, with new work differentiated subtly to maintain legibility between historic fabric and contemporary repair. “Self-describing” detailing should be used for new interventions, acknowledging the continuing history of the Prairie House without compromising its midcentury character.

Herb Greene, a student of Bruce Goff, is an innovative architect and educator known for his Prairie House (1961) and residential work that expresses client personality, site, and materials. Beyond architecture, Greene is a prolific collage artist and author who promotes integrating art into building, with his writings and artworks widely published and collected.

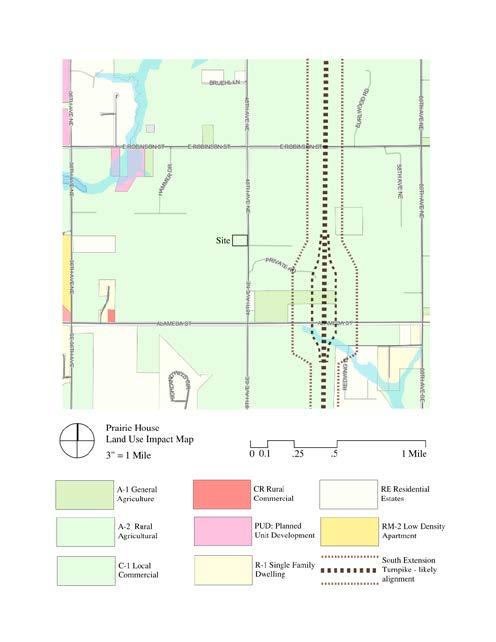

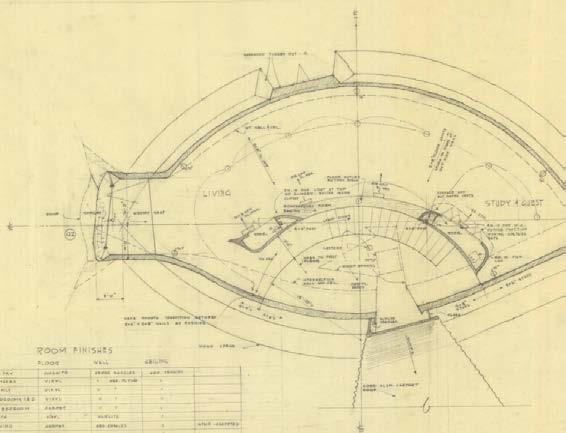

The Prairie House is part of what was once the prairie northeast of Norman. Located on the south side of the 3.8-acre slice of the Oklahoma plains, the house is oriented long ways from the East to the West with an entry facing to the South. Views are framed from the Kitchen towards the sunrise in the East and from the Master Bedroom and Living towards the sunset in the West. The original grassland context provided the appropriate combination with the structure as it seemingly emerged from the plains itself.

While the vast prairie of the 1960s is somewhat diminished with the planting of cedar trees and the spread of housing, this is still a rural part of central Oklahoma, and the spirit of the prairie is still there. The land on which the house sits was the traditional home of the Potawatomi-Shawnee, Kiowa, and Kickapoo peoples.

The property consists of the intact main house, a propane tank, a shipping container, a large concrete slab, a barbed wire perimeter fence, steel entry gates, wood gate posts, and a railroad tie wall/entry landscape feature. The Prairie House Trust owns the Prairie House, associated structures, and property. While the house is not on the National Register, it is considered an eligible property and managed accordingly.

This process renews the relationship between the Prairie House and the land that shapes it.

An introduction to the Prairie House and PHPS

The proposed work for the Prairie House site will focus on restoring the integrity of both the historic structure and its surrounding prairie landscape. The plan begins with the restoration of the Prairie House itself, addressing the weathered cedar shingles and siding, compromised framing, and deferred maintenance documented in the Historic Structure Report. This effort will return the building to its original architectural expression and ensure it is stabilized for future public use as a museum and learning center.

Beyond the house, significant site rehabilitation will reestablish the property’s relationship to the prairie. This includes removing the nonhistoric ponds that currently direct water beneath the building, clearing invasive trees and vegetation that obscure the original landscape, and eliminating manmade intrusions such as the concrete pad, power pole storage, electrical poles, and the shipping container. Once cleared, the site will undergo prairie restoration, reintroducing native grasses and plant communities that reflect the landscape Herb Greene originally designed the house to emerge from.

A narrative trail will loop around the property, offering visitors an interpretive experience that connects the architecture, ecology, and cultural history of the site. Future phases envision acquiring adjacent land to protect the view corridor and allow for expansion, as well as the construction of a visitor center designed to support tours, exhibits, and educational programming. Together, these efforts will restore the Prairie House and its landscape as a cohesive cultural landmark,an immersive environment where architecture and the Oklahoma prairie once again speak as one.

This process renews the relationship between the Prairie House and the land that shapes it.

Today, the Prairie House sits within a landscape that has drifted from its original intent. Over decades of private ownership, the surrounding prairie was altered by ponds, trees, and man-made features that obscured the house’s connection to the open horizon. The site remains rich with potential, its layered history and remarkable architecture poised for renewal. Understanding this existing condition provides the baseline for the Society’s vision: to restore the dialogue between Greene’s architecture and the prairie that inspired it.

Two non-historic ponds will be removed to correct the site’s disrupted hydrology. Over time, these artificial features have directed water toward the foundation, accelerating deterioration of the crawlspace and ramp. Their removal will restore proper drainage, protect the building’s structure, and re-establish the natural grade of the prairie. This critical step ensures the long-term health of the house while returning the land to its original rhythm of rainfall and runoff across the open plains.

At the heart of the project is the careful restoration of Herb Greene’s 1961 Prairie House—an internationally recognized icon of Organic Architecture. Guided by the Historic Structure Report, the work will replace deteriorated cedar shingles and siding, repair the lower skirt framing, restore windows and doors, and stabilize the carport and pyramid structure. Every intervention will follow the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Rehabilitation, ensuring the home is both structurally sound and true to Greene’s original intent, enabling its use as a cultural and educational center.

The original prairie setting—open, windswept, and rhythmic—has been replaced by dense plantings of invasive cedar and other non-native trees. Selective clearing will remove these visual and ecological barriers, re-exposing the panoramic views that Greene designed the house to frame. This restoration of the horizon is not just aesthetic; it revives the ecological health of the prairie and renews the spatial dialogue between architecture and landscape.

Modern intrusions such as the concrete pad, power poles, storage container, and other utility remnants will be removed to declutter and simplify the site. These non-historic elements distract from the sculptural presence of the Prairie House and interfere with the visitor experience. Their removal restores a sense of authenticity, allowing the site to breathe again and reassert the timeless qualities of Greene’s design.

Once cleared, the site will be re-seeded and replanted with native prairie grasses and forbs, reviving the landscape that originally inspired the architecture. This ecological restoration will stabilize soils, manage stormwater naturally, and create habitat for pollinators and wildlife. More importantly, it will restore the poetic continuity between Greene’s design and the environment it grew from, reuniting the house with the prairie as a living, breathing organism.

This process renews the relationship between the Prairie House and the land that shapes it.

A new narrative trail is planned to loop through the property, guiding visitors through the story of the Prairie House, its architect, and its place within the broader American School movement. The path will trace subtle shifts in terrain and light, framing key views of the house and prairie. Interpretive markers will connect architecture, ecology, and history, transforming the site itself into a living classroom where art, nature, and storytelling converge.

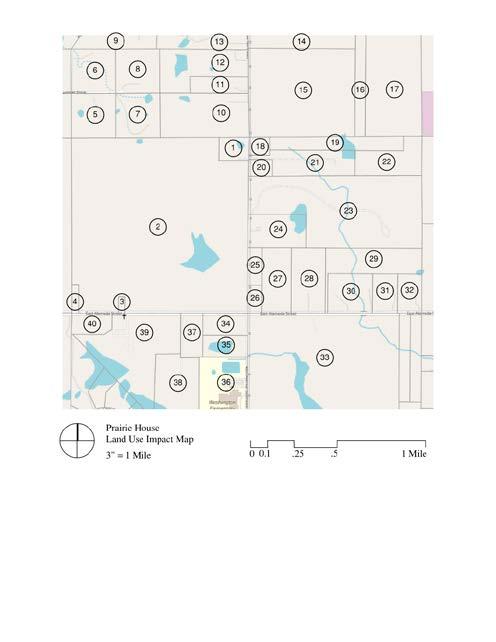

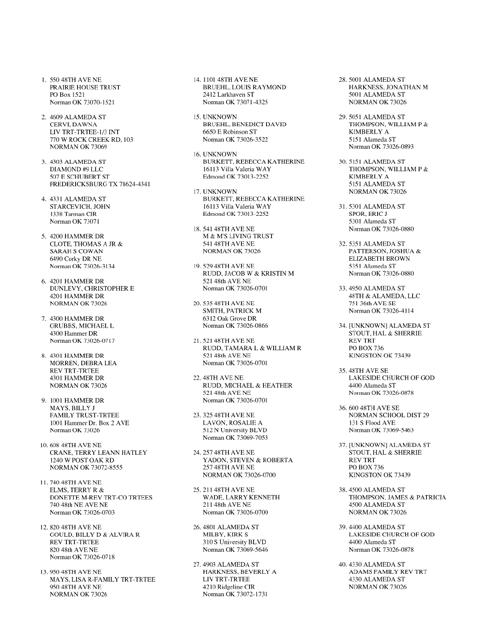

To ensure long-term protection of the site’s visual and ecological context, PHPS plans to acquire adjacent parcels of land. Expanding the property boundary will safeguard the horizon views and allow for compatible development of educational and program spaces. This step secures a sustainable future for the site, preserving the isolation, serenity, and sense of discovery that define the Prairie House experience.

A modest new visitors center will serve as the welcome point for guests, researchers, and students. Designed with sensitivity to scale, material, and landscape, the structure will provide essential amenities, restrooms, exhibition space, and educational resources, while remaining secondary to the house itself. As a contemporary counterpoint the visitors center will extend the spirit of Greene’s vision, supporting the Society’s mission to educate, engage, and inspire future generations.

This drawing illustrates the work proposed for this phase and indicates more exciting enhancements to come in future phases.

The landscape in its present, unaltered state.

Today, the Prairie House sits within a landscape that has drifted from its original intent. Over decades of private ownership, the surrounding prairie was altered by ponds, trees, and manmade features that obscured the house’s connection to the open horizon. The site remains rich with potential, its layered history and remarkable architecture poised for renewal. Understanding this existing condition provides the baseline for the Society’s vision: to restore the dialogue between Greene’s architecture and the prairie that inspired it.

This drawing illustrates the work proposed for this phase and indicates more exciting enhancements to come in future phases.

A gateway to the experience.

A modest new visitors center will serve as the welcome point for guests, researchers, and students. Designed with sensitivity to scale, material, and landscape, the structure will provide essential amenities, restrooms, exhibition space, and educational resources, while remaining secondary to the house itself. As a contemporary counterpoint the visitors center will extend the spirit of Greene’s vision, supporting the Society’s mission to educate, engage, and inspire future generations.

“The truest restoration is not of walls, but of the dialogue between architecture and the land that shaped it.”

The renewal of the Prairie House is not only a matter of preservation—it is an invitation to participation. What began as a singular work of architecture now opens outward toward community, education, and shared experience. In its next life, the house becomes both host and catalyst: a place where art, ecology, and inquiry converge. Tours, performances, residencies, and workshops will allow visitors to encounter Greene’s vision not as history but as living dialogue. As the Prairie House Preservation Society grows, so too will the scope of these engagements—extending from intimate gatherings within the house to public programs and partnerships across the region. Through this unfolding, the Prairie House will reclaim its original purpose: a space for imagination to take form, evolve, and inspire new creation.

Site investigation will be done by owner and an Architect led team of consultants will be chosen to prepare drawing and specifications for the project. This section identifies specialists recommended for the project, their proposed responsibilities and proposed qualifications.

During any construction project, issues will arise that require decisions by an owner’s representative. These may issues having to do with budget, schedule, unforeseen conditions, conflicts, accidents and many other things that will require direction from the owner. To fulfill the role of Owner’s Representative, a non-profit organization will usually form an ad hoc “building committee.” The PHPS building committee could be composed of 4-6 members, including the executive director; at least two board members who have experience with construction projects; and other board member[s] who have financial and legal expertise. A chair or two co-chairs should be appointed to take responsibility and be entrusted to make day-to-day decisions needed by the design and construction team, be present at regular construction meetings, and be available to be on site at short notice.

Owner is directly responsible for fundraising, procurement of land survey and hiring the geotechnical and testing agency for the project. Survey and geotechnical report need to be done before design team begins work, as these will form the basis of structural and civil engineering decisions.

Capital Campaign Consultant – introduce to design and construction team so they can understand benchmarks that will allow the project to begin while capital campaign continues.

Survey: ALTA Survey, including location of nearest fire hydrants

Task: Order survey and get agreement with testing agency for services during the construction phase.

Geotechnical report and testing

Rehabilitation Design Team: Documentation of exterior cladding as it is removed layer by layer, materials analysis, construction drawings

● Preservation Architect:

● ADA compliance [if final program direction dictates]

● FFE

● Exhibits design

● Civil Engineer

● Structural Engineer: Analysis and intervention for carport, floor framing, and skirting

● MEP Engineer: Upgrades to HVAC, plumbing, and electrical systems, preserving original infrastructure where feasible, possible participation in new roof drainage plan

● Lighting

● A/V and Acoustics

● Envelope consultant

● Landscape Architect: Water flow correction, native prairie restoration, driveway restoration, parking, ADA access considerations

Stage 1 - Stabilization + Construction Site Preparation

Stage 2 - Prairie House Restoration

Stage 3 - Landscaping + Site Enhancement

BIM Updating and Cut File Generation (daily, 60 days)

3 Total - Design Services

Stage 4 - Visitor Center (3,700 sf.; Construction: 1.8M)

(Based on construction cost of $1,632,026.50) Combined Design Services

1, 2 and 3

Owner-Direct Costs (not in design services)

This section is provided for informational purposes only and outlines the anticipated scopes of work for the various trades likely involved in the Prairie House restoration. It is not intended as a directive to contractors who may participate in the project.

Masonry & Concrete: Granite ramp repair or reconstruction, crawlspace improvements (consider paving to floor of the crawl space)

• Carpentry: Skirting, structural framing, cedar cladding repair

• Roofing: Replace/restore roofing systems, add historically accurate drainage, and/or route an internal drain through the building

• Glazing: Restore/recreate original windows, ventilation flaps, skylights

• Plumbing: Modernize systems with minimal visual impact

• Electrical: New lighting, outlets, code upgrades; restore original fixtures where possible

• HVAC: Design for efficient, concealed operation

• Finishes: Reinstall cork flooring, carpet, linoleum, mirrors, tile

• Landscape: Pond removal, regrading to restore Prairie and provide positive drainage away from the house, native planting

Design-build and design-bid-build are two common construction project delivery methods that differ mainly in how responsibility and sequencing are structured. In design-bid-build, the owner contracts separately with a designer and a builder, following a linear progression of design, bidding, and then construction. In contrast, design-build combines both services under one contract, allowing design and construction phases to overlap. Each approach offers unique advantages depending on an owner’s priorities such as control, budget certainty, schedule, and risk.

Design-bid-build remains the traditional method, valued for its transparency, competitive bidding, and clear separation of responsibilities. Owners benefit from direct oversight of the design and contractor selection process, ensuring strong design integrity and cost competition. Because architects and builders work independently, design quality and professional objectivity are typically high. However, this method often results in longer project durations due to its sequential nature and limited collaboration between design and construction teams. Miscommunication can lead to change orders and cost overruns, and the owner bears the primary risk of coordination issues or design omissions. Despite these limitations, design-bid-build is preferred for projects requiring well-defined scope, predictable specifications, or stricter public procurement rules.

Design-build integrates design and construction into a single entity responsible for both phases. This approach promotes early collaboration, reduces change orders, and can deliver projects faster—sometimes up to 15–20% shorter schedules compared to traditional methods. The unified structure minimizes conflict and simplifies communication while transferring risk from the owner to the design-builder. Yet, design-build requires trust and clear expectations, since owners relinquish some design control and lose the cost transparency of competitive bidding. Quality can also vary depending on how well the builder balances design intent with budget targets. When well-managed, however, design-build projects achieve cost and schedule efficiencies that benefit complex or time-sensitive developments.

In summary, design-build favors speed, collaboration, and single-point accountability, ideal for owners prioritizing efficiency and reduced administrative burden. Design-bid-build, in contrast, prioritizes control, transparency, and competitive pricing, making it better suited for owners who value design independence and well-defined processes. The optimal choice ultimately depends on project size, complexity, and the owner’s tolerance for risk and desired level of involvement.

For more detail, see the appendices for detailed timeline.

For more detail, see the appendices for detailed budget by CSI division and by construction trade.

A non-profit organization such as the Prairie House Preservation Society can access Federal and Oklahoma State Historic Preservation Tax Credits and transfer (monetize) these credits, but the process differs for Federal and State credits. Federal credits cannot be sold directly, but State credits usually can be sold or transferred—typically via a partnership structure with an investor who purchases the credits at a discount. , ,

● Federal credits (20%) are not directly transferrable or sold. Non-profits must create a for-profit entity, often a limited liability company (LLC), which owns the property for at least five years.

● The non-profit partners with an investor (usually someone with significant federal tax liability) who invests cash in the LLC in exchange for receiving the credits.

The process:

● Form an LLC and transfer property ownership to the LLC.

● Complete the three-part National Park Service (NPS) application with input from the Oklahoma State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO).

● After rehabilitation is certified, investors receive credits based on their role in the LLC.

● Credits are usually sold at a discount to attract investors, providing the non-profit with upfront funds for preservation work.3

● Oklahoma state tax credits (25%) are transferrable—they can be sold or assigned to a third party.

● After SHPO approval and project completion, the credits can be sold to businesses or individuals with an Oklahoma state income tax liability.

The process:

● Submit the project application to SHPO for eligibility and ov ersight.

● File with the Oklahoma Tax Commission after project completion, including required documentation.

● Credits may be claimed over five years and can often be advertised, sold, or assigned to a purchaser through a broker or direct arrangement.

● Develop the rehabilitation plan and get SHPO approval.

● Complete and certify rehabilitation work.

● Work with a tax attorney or broker to structure and market available credits.

● The non-profit receives funds (usually less than face value of credits)

from the investor/purchaser; the purchaser then applies the credits to their own tax liability.

● Keep all documentation for at least five years after completi on.

● Federal credits require complex partnership structuring—legal/tax advice is critical.4

● State credits offer more flexibility and can often be sold outright for cash; the actual sale mechanism may involve brokers or direct negotiation.

● SHPO/NPS eligibility/scope approvals are required to avoid disqualification.

The process leverages both Federal and Oklahoma credits when possible, offering significant funding for preservation projects through strategic sale or syndication of credits to interested investors.3,

“To conserve is to understand before acting; to restore is to reveal what time has hidden, not to erase what it has

Rehabilitating the Prairie House demands equal parts restraint and resolve. Every material, joint, and surface holds meaning, revealing the architect’s hand and the passage of time. The goal is not to restore youth, but to sustain authenticity, allowing the building to continue aging with dignity and purpose. Conservation here means working with, not against, the marks of history: repairing rather than replacing, clarifying rather than perfecting.

This framework outlines a philosophy of minimal intervention and maximum understanding, guided by national preservation standards and local stewardship. Through careful study and sensitive repair, the Prairie House will retain its expressive character while regaining stability and resilience. The work affirms a simple but essential truth: that preservation is not nostalgia, but continuity, a dialogue between the past and the future, carried forward in the grain of the cedar and the light of the prairie.

As Grene was a OU student who studied and worked with Goff, later joining the faculty, it’s natural that opportunities to engage with the college should be explored. Below are several areas where it could make sense to partner with the College of Architecture and even collateral colleges.

1. Purpose & Principles

Protect original fabric, manage moisture, UV, and pests, ensure visitor safety.

Follow the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards and NPS Cultural Landscape guidance.¹

Emphasize preventive care and Integrated Pest Management (IPM).²

2. Roles, Records, and Tools

Roles: Though likely filled by some combination of Executive Director, volunteers and contractors, they are as follows:

Site Manager

Facilities Tech Landscape Steward Collections/Exhibit Lead Licensed Pest/Wildlife Contractor.

Records: Daily logs monthly moisture/IPM logs annual condition survey with photo points.

Tools:

Minor Maintenance tools

6 ft step ladder dedicated for indoor use

Hand tool kit – hammer, screwdrivers, pliers, socket set, etc.

Cordless drill

Tape measure

Extension cords

caulk gun

stainless fasteners

hardware cloth compatible sealants. ³

Cleaning tools:

HEPA vacuum cleaner

Grounds & Exterior Tools & Equipment:

24’ extension ladder with outriggers

Garden tools (rake, shovel, pruners, loppers, leaf blower)

Lawnmower

Weed eater

Leaf blower

Hose watering cans

Supplies:

Minor Maintenance Supplies

painter’s tape

duct tape

electrical tape

Teflon tape

bailing wire

Cleaning Supplies

Neutral-pH wood soap (for cedar)

[note: clarify optimal care routine with the Western Cedar Association] stainless/aluminum cleaner soft bristle brushes microfiber cloths non-abrasive scrubbing pads glass cleaner

Insect/Wildlife Control:

Termite bait stations live traps (for rodents if needed) caulk/sealant copper mesh for gaps [copper is more durable than steel wool which may degrade or be chewed away by rodents.]

replacement screening for ventilation flaps and doors.

Safety & Monitoring:

Flashlights, step ladder, fire extinguisher (ABC type), carbon monoxide detectors, smoke detectors, batteries.

Plumbing & HVAC:

Replacement faucet washers, plumber’s tape, small pipe wrench, HVAC filters, condensate drain cleaner.

Documentation & Recordkeeping:

Maintenance log (paper and/or digital), camera for photographic documentation, labeled storage bins for supplies.

3. Building Envelope

• Western Red Cedar

Documentation & Recordkeeping: Maintenance log (paper and/or digital), camera for photographic documentation, labeled storage bins for supplies.

3. Building Envelope

Western Red Cedar

Monthly debris removal.

Spring/Fall: Gentle wash, mildew treatment, spot sealant repairs.

Refinishing

Ensure moisture content is below 20% transparent sealant – once a year [not recommended because it sets unrealistic expectations and wood will still age, and more unevenly]

stained coatings – 3-5 years

Factory finish – 15-25 year warranty

Unfinished – seasonal inspection only Always: Use stainless or double galvanized fasteners to avoid staining/ corrosion.³

• Corrugated Aluminum

o Quarterly rinsing.

o Spring: Hand wash with mild detergent; inspect coatings, scratches, fasteners, galvanic contact.

o Touch-up coating as needed.

o Inspect canopy/skirting and ventilation flaps annually.

• Roofs, Drainage System, Flashings

o Monthly debris removal.

o Annual inspection of flashings, penetrations, and sealants.¹

• Doors, Windows, Housekeeping

o Monthly check of weatherstripping.

o Weekly HEPA vacuuming and dry dusting; no aerosols near cedar.²

4. Mechanical, Electrical, and Plumbing (MEP) Systems

• Water Heater

o Inspect annually for corrosion, leaks, sediment buildup; flush tank if applicable.

o Check temperature settings to prevent scalding and conserve energy.

• Furnace & AC Compressor

o Replace filters quarterly or per manufacturer.

o Annual service contract for cleaning, lubrication, and safety checks.

o Check condensate drain line to prevent clogs.

• Exhaust & Ventilation Fans

o Clean grilles quarterly.

o Test ventilation fan near roof access door to ensure operability.

• Plumbing Systems

o Inspect visible supply and waste piping annually for leaks or corrosion.

o Test all faucets and toilet flush mechanisms quarterly.

o Check drainage in crawl space and around foundation to prevent backups or moisture intrusion.

• Electrical

o Inspect panel and breakers annually by licensed electrician.

o Test GFCI/AFCI outlets quarterly.

• 5. Appliances (Vintage and Operational)

• Stove (vintage gas or electric)

o Check burners, ignition, wiring (if electric), or gas connections (if gas).

o Clean surfaces with museum-safe cleaners that avoid scratching enamel.

• Refrigerator (vintage)

o Inspect door seals for air leaks.

o Clean condenser coils annually.

o Check refrigerant charge if cooling seems diminished (specialist required).

6. Substructure, Crawl Space & Moisture Control

• Monthly inspections for standing water and frass/mud tubes.

• Maintain ventilation openings equal to ~1/150 crawl-space area.