ISLANDSCAPE AND AQUATIC URBANISM

Nomadic, Amphibious, and Resilient Ecosystem for Small Island Developing States

Graduate Thesis_ The Cooper Union_ 2023 Fall

Advisor: Susannah C. Drake

Site: Kiribati, the Paci c Ocean

*The Small Island Developing States (SIDS) are a grouping of developing countries which are small island countries and tend to share similar sustainable development challenges. These include small but growing populations, limited resources, remoteness, susceptibility to natural disasters, vulnerability to external shocks, excessive dependence on international trade, and fragile environments.

Islands, as both tangible geographical environments and metaphoric entities, are characterized by their isolation, uid boundaries imbued with contention, and self-su cient yet vulnerable ecosystems. Island is a miniature experimental station for the hybridization of cultures and global climate observation. They provide a unique framework for rethinking the relationship between aquatic systems and terrestrial environments.

My thesis starts with questioning why territorial framing and the national scales dominated adaptation governance. How do “borderless climate risks” challenge this framing and what are possible governance responses? What happens to our urban resilience evaluation systems if we shift away from predominant global views and mega-city model, to the extensive socio-spatial and ecological transition currently transpiring in regions stereotypically perceived as “remote” or “wilderness,” like the Paci c Ocean. Are non-terrestrial environments such as the oceans becoming spaces of urbanization? To what extent are such zones now being integrated into the global nexus of urbanization? Furthermore, how do they deal with climate adaptation in relation to energy, water, material, and food and how do we

understand aquatic urbanism in such contexts? Through representation and interventions across varied spatial scales, coupled with an integration of climate resilience theory, geopolitical visualization, and material experimentation, my thesis aims to addressing global challenges of climate resilience and equitable environmental adaptation in small island nations in Paci c Ocean and broaden the architectural perspectives of informal urban theory into the urbanization of “extreme territories”.

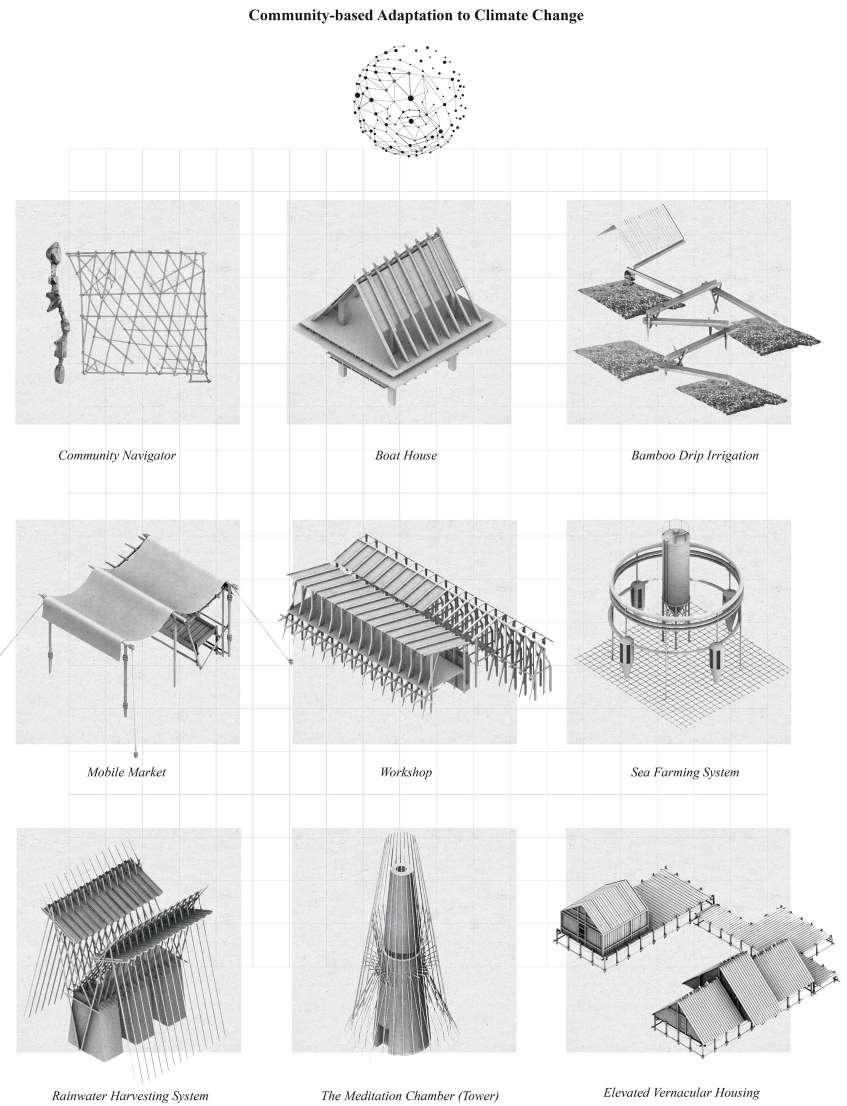

The concept of “islandscape”, weaving the tangible topographies of islands with their cultural, historical and symbolic resonance, is proposed as the theorization of aquatic urbanization. Far from being a passive backdrop, “islandscape” asserts itself as a generative design milieu, inviting nuanced provocations and interventions. Amid the intricate economic and political landscape and the geographical-territorial imaginaries, “islandscape” has become an interdisciplinary corpus that posits a profound avenue for contemplating climate resilience and confronting environmental inequities. The morphological strategy and testing of the concept “islandscape” commence with the subsequent four themes: Atlas, Water, Community, and System.

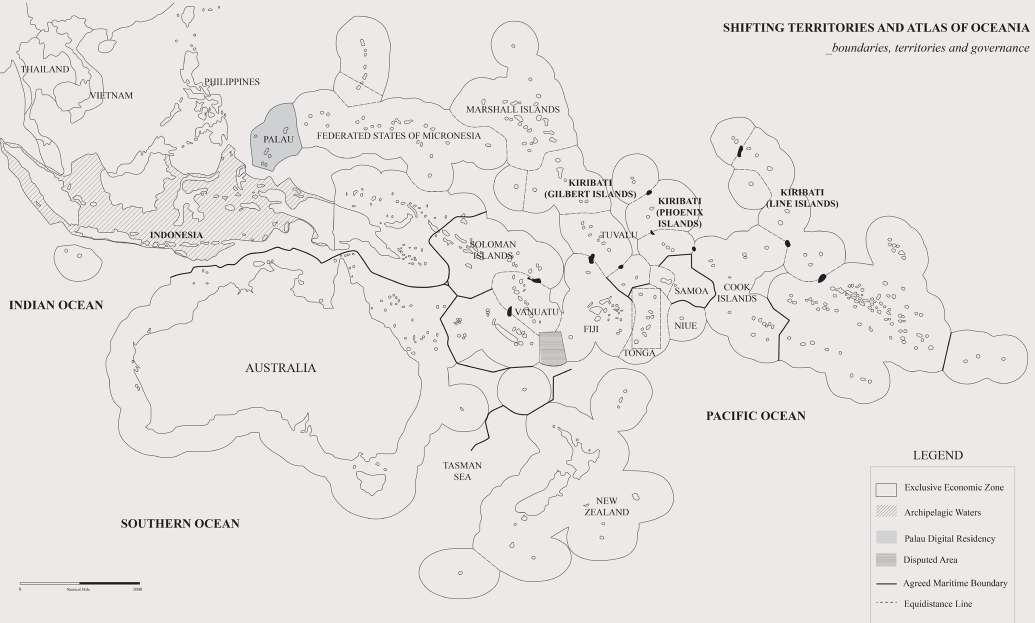

_Boundaries, Territories and Governance

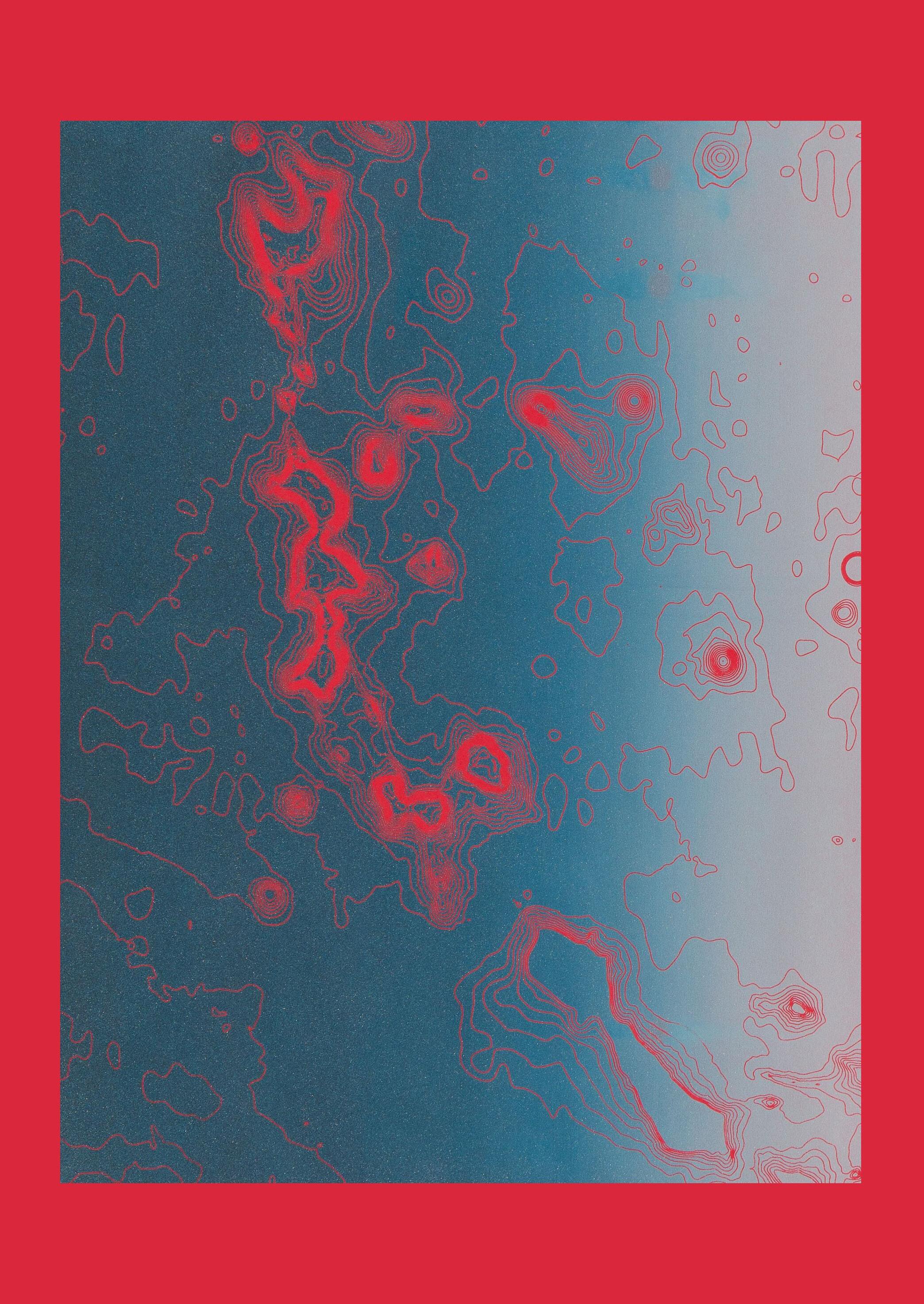

Paper embossing: The Paci c Ocean and Disappearing Archipelagos Size: 7’’x6’’ Thickness: 3mm

The ocean is not a void, it is not value-neutral, nor is it an external entity separate from urbanity. Rather, It is a deeply structured political space, an essential part of the Earth’s system—a socio-ecological entity deeply intertwined with the fallout of human activity. The informal urbanization and invisible global transportation circuits co-shape the transgressive, hybrid identities, and resistant cultures in the Paci c Islands region. My thesis argued that non-terrestrial environments such as the oceans should be regarded as spaces ofurbanization and explored what extent such zones are now being integrated into the global nexus of urbanization.

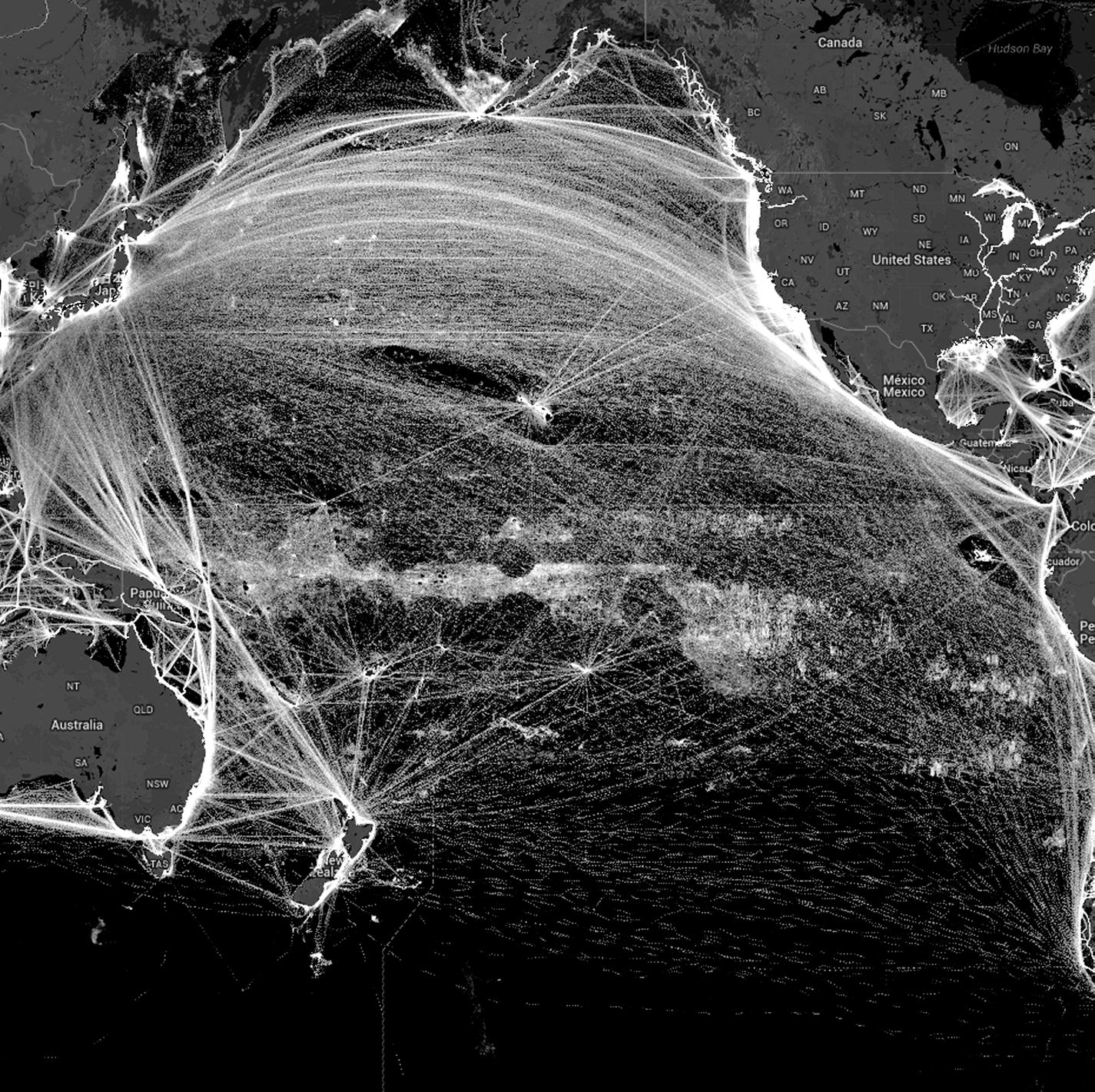

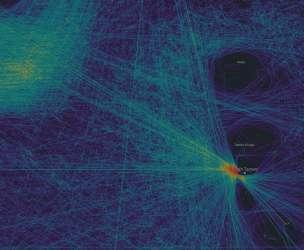

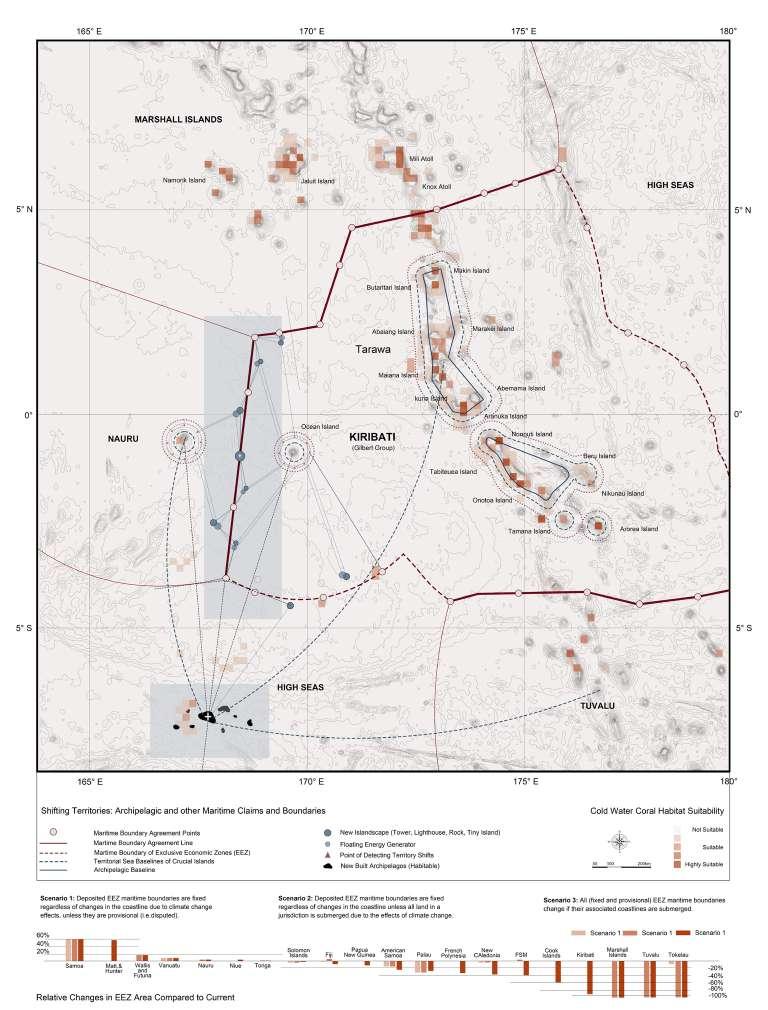

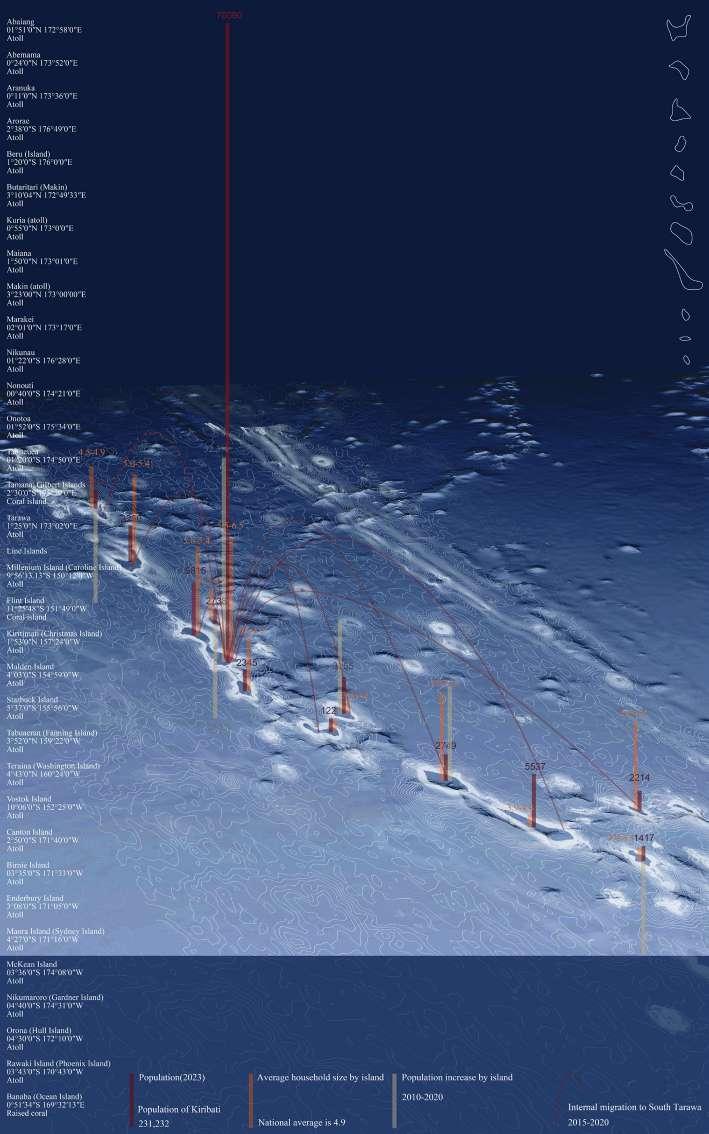

When mapping the political boundaries and exclusive economic zones of Paci c island nations, I observed the Paci c Ocean as an interlocking, bubble-like ecological structure. Environmental crises such as rising sea levels and coral bleaching exacerbate the fragility of these boundaries. However, these ‘bubbles’ are not void spaces. Focusing on Kiribati, an island country in the Micronesia subregion of Oceania, central Paci c Ocean, we note its signi cant population of over 119,000 (2020 census), with more than half residing on Tarawa atoll. Kiribati consists of 32 atolls, spanning 811 km² (313 sq mi) of land over 3,441,810 km² (1,328,890 sq mi) of ocean. Zooming into Kiribati’s territory, we observe a complex network of international shipping lanes and local shing vessel trajectories. On the ocean, these vessels represent not only a transport system but also a crucial aspect of urbanization.

1.Marine Tra c Map of the Paci c Ocean_Carbon Footprint of the Ocean

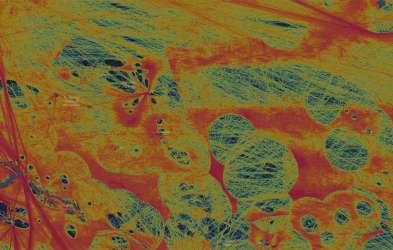

2. Zoom in- Marine Tra c Map of in the central Paci c Ocean

3. Zoom in- Marine Tra c Map in kiribati (Gilbert Islands)

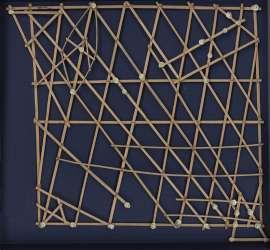

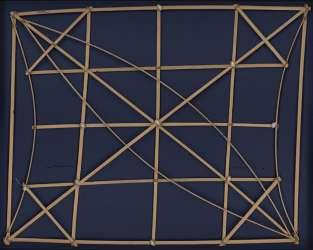

4. Marshall Islands stick chart, Meddo type, 192-. Geography and Map Division

5. Marshall Islands stick chart, Rebbelib type, 192-. Geography and Map Division

6. Marshall Islands stick chart, Mattang type, 192-, Geography and Map Division

By mapping the tra c routes and ports across the Paci c Ocean, distinct patterns emerge in its northern, central, and southern regions. The north, characterized by numerous vital international routes, exhibits highly dense and direct tra c lines, signifying a signi cant carbon footprint of capitalism. The south, interspersed with islands of varying sizes, displays an interconnected weblike system of routes. Moving further south, the urban carbon footprint diminishes. A closer examination of the central Paci c’s tra c routes reveals a bubble-like navigation pattern, highlighting the signi cant in uence of exclusive economic zones (EEZs) and political boundaries on maritime routes and resource access.

Contrasting with Western maps, the Marshall Islands stick charts o er insight into how Paci c island natives observed and navigated the seas. Lacking astrolabes, sextants, or even compasses, islanders relied on maps made from the midribs of coconut leaves tied together to form an open framework. Islands were represented by shells tied to the framework or at the intersections of two or more sticks. These lines depicted ocean swells, major surface wave crests, and their directions as they approached islands, serving as a crucial navigation and shing guide. The Marshall Islands stick chart embodies a unique cartographic encoding system of indigenous wisdom, representing a body of knowledge passed down through generations.

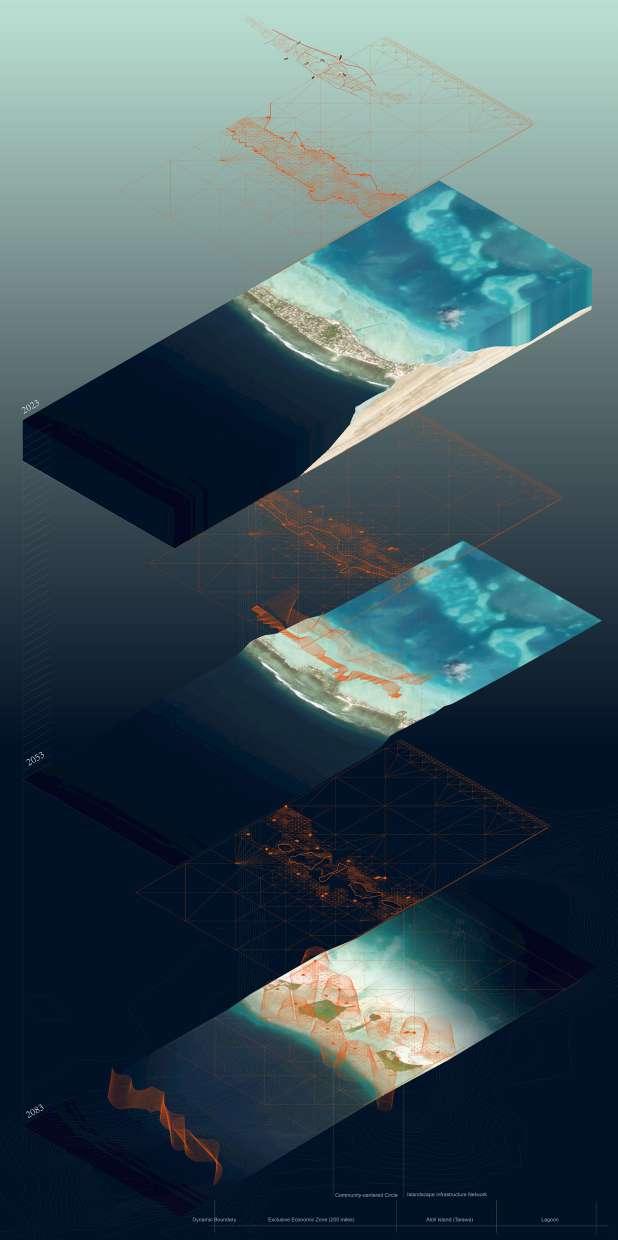

The rise in sea levels will variably impact di erent atoll nations, altering the boundaries of their exclusive economic zones (EEZs) as coastlines shift, consequently increasing or decreasing their territory. Among these, Kiribati, a lower-lying atoll nation, stands to lose a signi cant portion of its landmass. Therefore, my research has progressively explored how to establish a dynamic boundary network to safeguard its rights to marine resource acquisition.

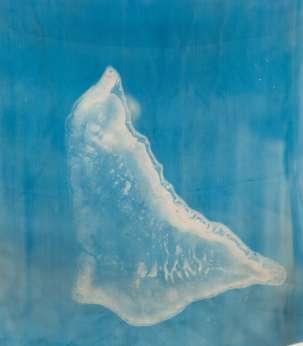

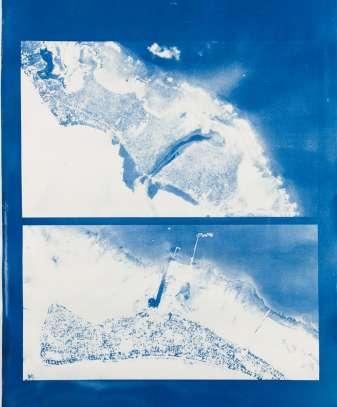

Cyanotype printing is a signi cant medium for the visual representation of the e ects of sea-level rise on atoll islands. The gradual fading of its chemical reagents over time mimics an “erosion” by the surrounding sea, thus imparting a sense of temporality to the static images. Additionally, I used silk to depict the uidity of the ocean and the unstable nature of

Can you imagine a place surrounded by water that has di culty in freshwater supply? Whose water? Who has access to It? Water has always been a crucial medium for understanding Territory, Resources, and Infrastructure.

Waves become the “environmental infrastructure” of the ocean; they serve as the integrative nexus between energy, geopolitics, economy, and maritime ecological development. If we rethink the water geopolitics in the age of the Anthropocene, islands will no longer be the antithesis of the mainland. Atolls can be regarded as the belts for ecological integration, which have intense relationships with aquatic environments. They are the test places of amphibious landscape interventions and imaginative water-based urbanisms.

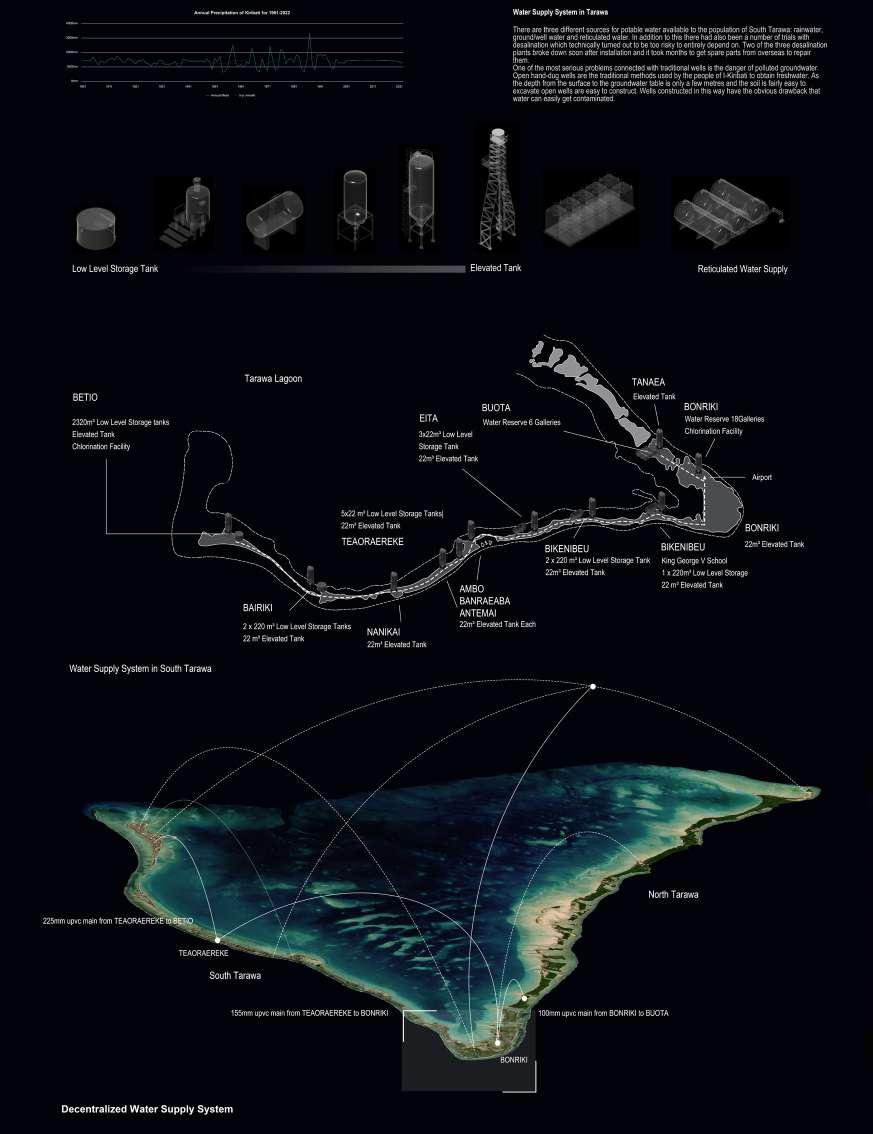

I speci cally looked into the water supply system of Tarawa, Kiribati: The population of Kiribati is approximately 92000, 50000 of which reside in densely populated neighborhoods of South Tarawa. South Tarawa is the most densely populated island among Kiribati’s 33 atolls and has experienced a population growth rate of 3% per year. The geography of Kiribati is somewhat limited in arable land resources.

The infrastructure of Kiribati especially in the island of South Tarawa is under immense tension due to sea level rise. Most of the houses lack modern sanitation and are not connected to the town sewage system. Extreme weather conditions and high tides routinely contaminate the groundwater.

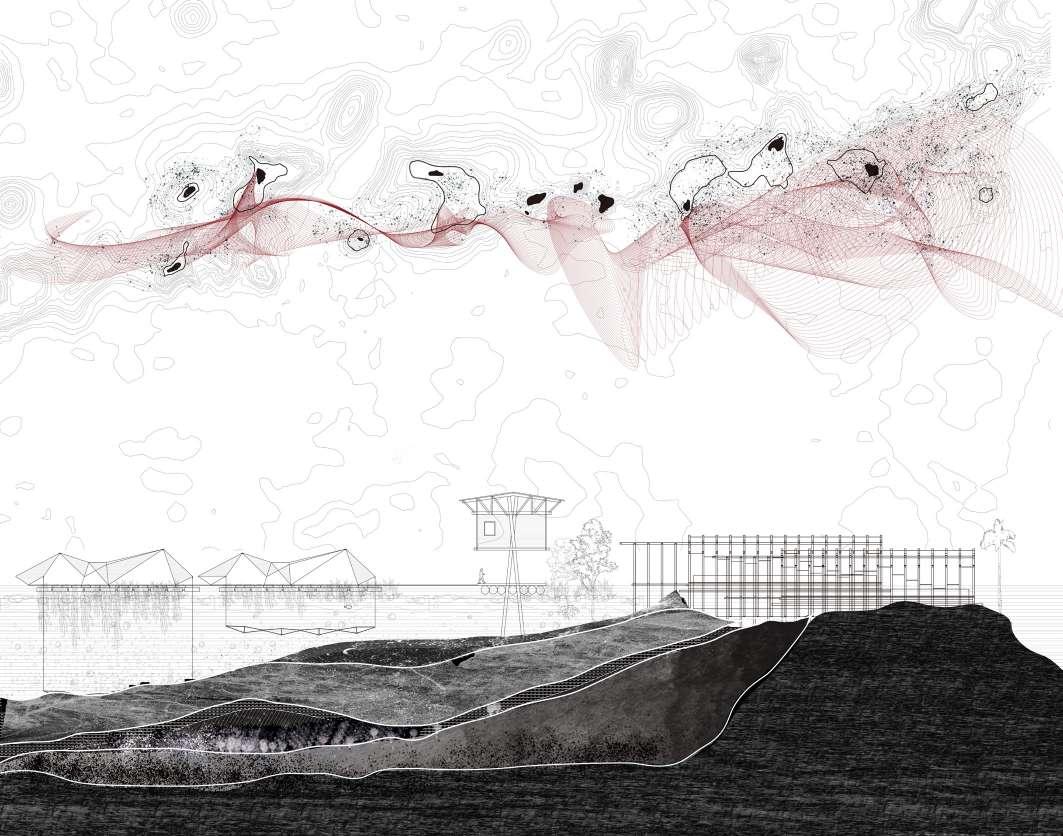

Continuing to zoom in, I focused on Tarawa, the capital of Kiribati. By analyzing Tarawa’s settlement pattern and designing appropriate architectural interventions, I aimed to mitigate the impact of rising sea levels and address issues of freshwater collection and storage. The territorial erosion of linear islands due to sea level rise is severe, and with Tarawa having just one crucial roadway, there’s an urgent need to develop designs for oating aquatic ecosystems as a response to this environmental crisis.

Left: Screenprint_11’’x 16’’

Seaweed Farming, Fisheries, and Floating Aquatic Settlements Constitute a New Pattern in the Ocean

Seaweed Aquaculture

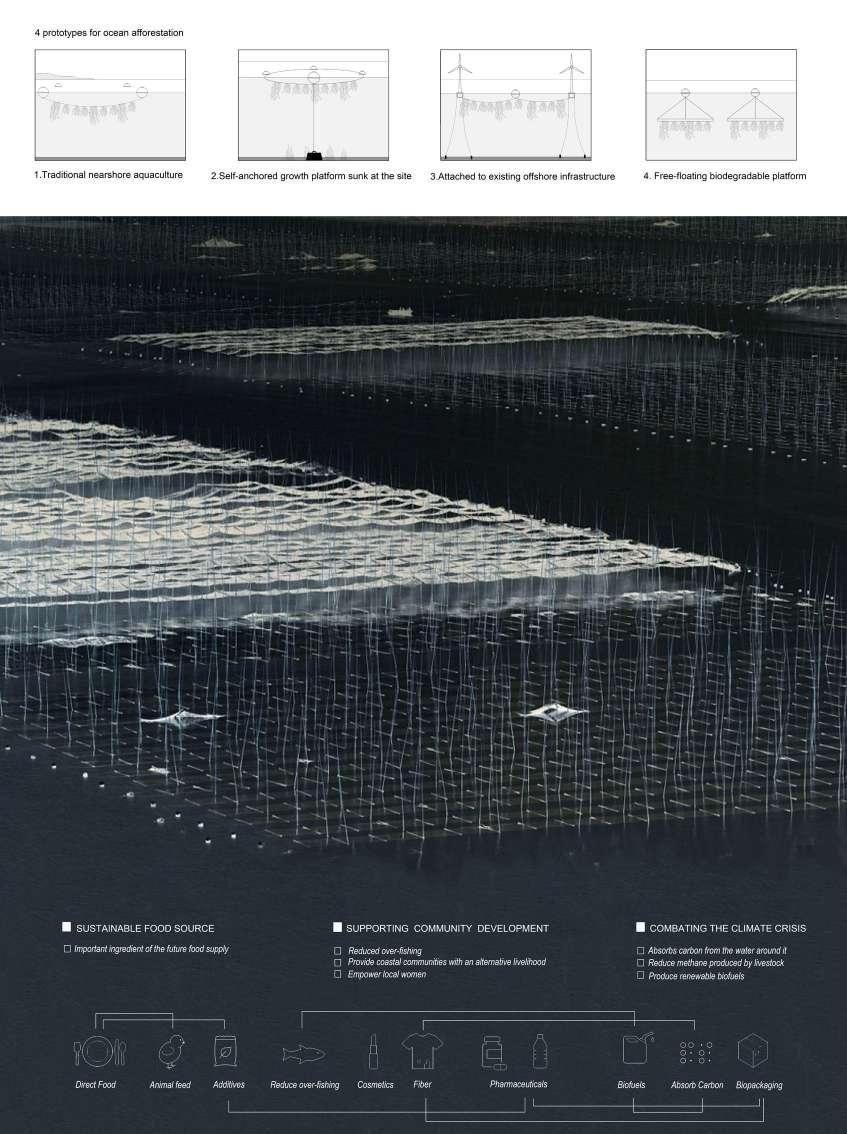

Growing seaweed is a simple and versatile method that o ers numerous bene ts to ocean ecosystems. Cultivating seaweed proves to be an e cient means of generating highly nutritious food to meet the needs of a growing global population. Unlike traditional land-based crops, seaweed cultivation does not necessitate fertilizers, pesticides, freshwater, or arable land. Moreover, it boasts rapid growth rates, with certain marine algae ready for harvest in as little as six weeks. Functioning as an underwater forest, seaweed serves as a natural carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus absorber, making it a valuable asset in the battle against climate change. Additionally, it functions as a water puri er and creates new habitats for a diverse array of marine life.It is also utilized in various medicinal and beauty products, biofuels, and packaging materials.

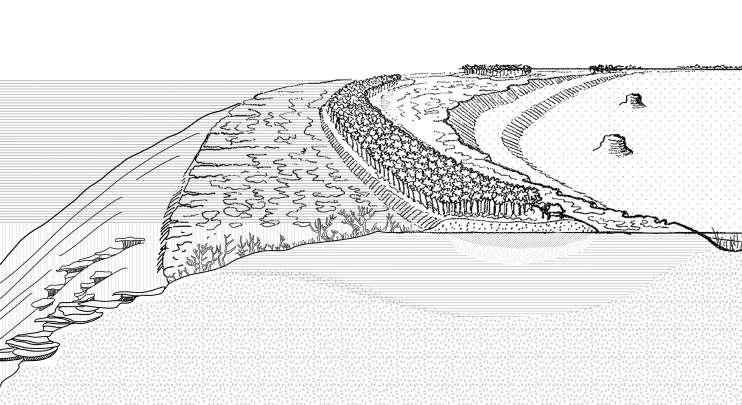

Down: Hand drawing_20’’x 40’’

The cross-sectional relationship of oceans, lagoons, and atoll islands, underground and seawater. Without coral reefs, shorelines would be vulnerable to erosion and rising sea levels

Designing for Changes and Territories in Flux

As sea levels rise, the linear atoll islands will gradually become submerged. In this process, we should abandon the notion of coastlines as xed lines and instead consider boundaries as uid areas to be managed and allocated within a changing timeline.

The Ocean is a key medium for envisioning future environmental management and urbanization. Following a multi-scalar analysis encompassing atlas, energy, infrastructure, land-use patterns, and indigenous communities, I have gradually outlined the political, economic, and cultural landscapes of developing island nations in the Paci c Ocean. I proposed a new infrastructure-oriented and community-based new system for resource assessment and acquisition, which challenged the existing maritime law, traditionally de ned by coastlines. The design integrates seaweed farming with new oating settlements, establishing xed infrastructural frameworks and scalable, resilient living structures, constituting a new aquatic urbanism.