THE ABBEY OF BONNEVAUX

An Illustrated History And Introduction

PREFACE

The spirit of place is a mysterious thing.

When I first visited Bonnevaux I was immediately and physically struck not only by its natural beauty but its spirit of place. I knew that a Benedictine monastery was founded here in 1119 and that awareness certainly forms one stronger layer of the spirit of place here. With our community we moved into the old, recently renovated abbey 900 years later, while the renovation of the Barn and the Stables continued – now a prayer space and a guesthouse respectively. Later I learned that this ‘good valley’ has been a place of contemplation for much longer.

The oldest monastery in Europe, pre-benedictine, is a few kilometres away from Bonnevaux and an ancient tradition testifies to monks from Ligugé coming to live a solitary life here from the 4th century. Today ina. contemporary way we continue this ancient monastic rhythm of life – a rhythm aligned with nature, our bodies and a living tradition.

So those who live at Bonnevaux, whether permanently, for extended visits or even for a short retreat or to meditate with us for one of our daily times of silent prayer, are immersed in a spirit of contemplative energy and peace with a historical density of 1700 years. In a world dizzy with speed and turbulent confusion Bonnevaux witnesses to a deeper present, an ever present origin, that we need to reconnect with if we are not to spin totally out of control.

Bonnevaux is therefore committed as a centre for peace for our time to the practice of contemplation and to sharing this gift with all who seeking it. I hope this booklet, lovingly composed to give a sense of its rich history, will give you a sense of connection to one of those places in the world where the spirit of place hardly needs to be put into words. Just felt. If this connection leads you to come and visit in person, we will be most happy to welcome you.

Laurence Freeman OSB Director WCCM

THE ABBEY AT BONNEVAUX

An Illustrated Introduction

1. WCCM at Bonnevaux

2. Piecing Together the History

3. The Earliest Settlement – The Coins

4. Bonnevaux – Foundation and the Medieval Years – A Papal Visit

5. The Years of Turbulence – The Protestant Abbot

6. A Secular Interlude

7. The Abbey at Bonnevaux – The Daily Life of A Medieval Monk

8. WCCM at Bonnevaux

1. WCCM AT BONNEVAUX

The Abbey at Bonnevaux is the international meditation and retreat centre of The World Community for Christian Meditation (WCCM).

The revival of meditation and contemplative practice within the Christian communities has been a significant feature of the last half century. There has been a number of inspirational figures and teachers who have developed an understanding of the power of meditation, demonstrated how it can enhance spiritual practice within Christian worship and can enable common ground to be found with adherents of many world faiths.

The inspiration behind the development of WCCM is to be found in the simple, but profound, teachings of John Main OSB (1926 -1982)

This is not the place to recount how John Main’s ministry and teachings, supported and developed by Father Laurence Freeman, his pupil, friend and successor, have inspired Christians across the world. These matters are well documented in publications and resources available from WCCM.

It is sufficient for the moment to understand that fewer than ten years after Father John’s death, Christian Meditation was being practised across the world and a structure for supporting this expansion was needed.

The network of communities, formalised in the establishment of WCCM in 1991, turned the vision of a global monastery without walls into a reality.

WCCM continued to develop organically with many publications, newsletters and internet linkages and tireless travel across the continents inspiring new followers and supporting new communities.

Gradually a shared understanding developed that a central and physical home would eventually be needed to enable the community of faith to reach the next level of maturity

In his introduction to ‘Bonnevaux: Incarnating the Vision’ Father Laurence describes how, “On the 25th anniversary of its formal naming, the National Coordinators of The World Community for Christian Meditation and all those in its governance, agreed that the time had come for an international centre and home.”

The identification of Bonnevaux, set in a secluded valley south West of Poitiers, home to an Abbey founded to observe The Rule of St Benedict from the Twelfth Century, marked the beginning of a new chapter in the life of WCCM.

So what do we know of the history of this beautiful location and the tradition of worship embodied here?

2. PIECING TOGETHER THE HISTORY

To understand the limitations of what we know of the history of the Abbey and the site, we take as our starting point the small commune of Lusignan, which lies about 12 kilometres south west of Bonnevaux.

And we start, not in medieval times but in the Eighteenth Century – the Age of Enlightment. For France the Age of Revolution, a time of new beginnings, of radical fervour.

November 1793 proved to be a crucial month for our understanding of the history of Bonnevaux. After years of discontent

with the rumbling ’ancien regime’, France was a cauldron of civil unrest. Driven on by waves of popular radicalism, the Convention had overseen the arrest, the trial and finally the execution of Louis XVI in January of that year. In Paris the Revolutionary leaders were jockeying for position. The Committee of Public Safety had been set up to defend and enforce the new order.

France was divided on the status of the Church. Paris was a hotbed of anti-clericalism. In the rural areas, and particularly in the South and far West, support for the rural clergy remained strong.

1789 had seen withdrawal of recognition of monastic vows and a determination that the property of the Church was at the disposal of the state. By legislation of February 1790 all religious orders were dissolved and monks and nuns were to return to private life. Clergy were required to swear an oath of allegiance and obedience to the State. By 1793, Notre Dame de Paris, like many of the major church establishments was designated as a Temple of Reason serving the Cult of Reason.

In the Poitou area these decrees and laws were largely implemented as required.

And so it was that in November 1793, in compliance with a law passed earlier in the year, all the records of The Abbey at Bonnevaux, along with those of the Church and Priory of Marcay, were destroyed by burning at the Maison Commune at Lusignan.

For the Revolutionaries the injustices and inequalities of the past were being expunged. For the historian the opportunity to examine and interpret the historic records of much of the life of medieval and early modern France disappeared in an instant.

To piece together the history of The Abbey at Bonnevaux we must rely on records of associated institutions not subject to the zealous implementation of the wishes of the revolutionary leaders. It’s like a jigsaw with so many pieces missing.

But there are scattered records of legal agreements and disputes, land records and limited evidence from the buildings themselves –sufficient for the story to be told.

For Bonnevaux, in particular, the work of Monsieur Roger and Madame Rolande Duputie, set out their book Marcay, Au Fils Du Temps (1995) provides a solid basis for putting together the essential pieces of the jigsaw. Much of what is recorded here is amplified in their history.

3. THE EARLIEST SETTLEMENT

In their account of the history of the Abbey M. and Mme. Duputie refer to the work of Dom Chambard, a monk of Liguge, who wrote his ‘Ecclesiastical History of Poitou du Verne in the Seventh Century’ in the 1850s.

Dom Chambard argued for a very early Christian presence in the Rhune Valley where Bonnevaux now stands.

Liguge is one of the oldest monastic foundations in France and has its root in the hermitical practices of St Martin of Tours, dating back to the mid-Fourth Century.

St Martin is renowned as the Roman soldier who converted to Christianity and who ripped his cloak in half to enable a beggar to keep warm. Having left the army, St Martin lived the life of a hermit before becoming a monk at Tours. He is credited with establishing the original foundation at Liguge where disciples lived according to the patterns of the Desert Fathers, each in his own locaciacum (small hut).

According to Dom Chambard, St Avitus, a follower of St Martin who would go on to be Bishop of Vienne and an adviser to the early Dukes of Burgundy, spent time when a young man based at Liguge living in isolation as a hermit in the “Bonne Vallis”. Thus building up a case that there was a monastic presence at Bonnevaux dating back many years before the Twelfth Century foundation.

There is only limited evidence for this early Christian settlement at Bonnevaux – but there is some circumstantial evidence of some early settlement in this location. This evidence is in the form of the treasure trove of coins uncovered in the demolition/building works undertaken in 1854

If we accept the proposal that the fact that the latest-minted coins in this cache date from the 870s means that the collection was secreted away some time in the late Ninth Century, the following questions arise.

Why would such treasure be hidden at this point in history? And who might have been seeking to protect their assets in this way? - We cannot know for certain but large areas of what would become modern-day France were subject to raids from Viking groups in the late Ninth Century. And if a landowner wished to protect their belongings might it have been a good idea to hide it away until more peaceful conditions prevailed?

And who in this isolated location could have had the opportunity to accumulate such a large fortune? Could it have been a religious house? - We can never know with any degree of confidence the answer to that question. But it is worth observing that it did become a constant source of grievance through the Middle Ages that the goods and riches of the monastic houses (and such other institutions and foundations that came into being – such as the early universities and the knightly orders of chivalry) could be accumulated, preserved and grow because, unlike the riches of families, they did not have to be shared out between competing inheritance claims.\

The case is unproven but there is certainly a possibility that this beautiful and peaceful valley has been home to followers of the monastic life for well over a millennium.

The Coins

The year 1854 saw radical changes to the estate at Bonnevaux.

Over half a century since it had passed into lay hands during the French Revolution, the De Montjou family undertook the dramatic transformation of a medieval Abbey into a fashionable Nineteenth Century chateau.

The main medieval buildings were completely destroyed with limited retention of original features in the newly built Second Empire chateau. The southern walk of the cloister was retained and incorporated into the new grand house.

The great monastic Church was demolished with the Sacristry at the eastern end preserved. And it was during the course of the demolition of the Church building that a spectacular discovery was made.

The story goes that two workmen from Limousin, masons working on the demolition, uncovered a rotting box inside a hole below the foundations of the Church. They waited till their colleagues had departed before exploring their find – but when they broke the box open they found hundreds of very early coins. They did not hang around but quickly exchanged the coins for modern currency and returned to Limousin.

There is no record of the two workmen ever being charged for robbery but the fact they acted quickly to cash in on their find does mean that a detailed inventory was made. That records that hoard comprised an extraordinary number of coins - 5000 deniers poitevines and 250 obols poitevines. In terms of dating the coins – 27 dated from the time of Charlemagne, (Carolignian Emperor 800- 814) and 33 bore the image of his grandson, Charles le Chauve or Charles the Bald (Carolignian Emperor 875 -877). These were the most recently minted coins in the collection hence the conclusion that the treasure might have been hidden away in the late Ninth Century.

4. BONNEVAUX – FOUNDATION AND

THE MEDIEVAL YEARS

Our knowledge and understanding of the next stage of development of the Abbey at Bonnevaux is on a much firmer historical base.

While the loss of the Abbey’s own archive will always leave gaps in our knowledge and leave questions unanswered there are other records, particularly legal records, that can provide some brief flashes of illumination.

It is clear that a Monastery following the Rule of St Benedict was established in the Valley following the gift of land in 1119 from a local nobleman, Hugues VII of Lusignan, and his wife Sarrazine, to Helie, abbot of Cadouin in Perigord The condition for the donation was that a Monastery should be built.

The work seems to have proceeded briskly under the direction of the Geraud de Sales, who is also credited with being the founder of Cadouin , and daughter abbeys at Pin, Absie and Chatteliers as well as Bonnevaux. Cadouin, in turn, was overseen by Pontigny Abbey itself a daughter house of Citeaux, the centre of the growing Cistercian Order,

1120 is the accepted date of the founding of the Abbey at Bonnevaux. Perhaps exhausted by the effort of arranging for the building of these new communities, Geraud died before the year 1120

was out.

The historian of the Cistercian Order, Stepen Tobin, talking in terms of the construction of monastic buildings in general in this period notes, “We must not forget that it never took less than five years to complete just the bare bones of the monastery.”

The lack of documentation specific to the foundation of Bonnevaux means there would seem to be little chance of ever identifying how quickly the buildings were erected, or indeed whether Bonnevaux was immediately incorporated into the fastgrowing Cistercian family or whether it had a period as a more independent entity. But perhaps it is a redundant question – there is no question that the new monastery was established for a community with a commitment to observance of The Rule of Benedict.

The Cistercian movement was based on dissatisfaction with the laxity of observance of the Rule of St Benedict in too many Benedictine houses. The drive of the key figures in the new order –Robert of Molesme, St Stephen Harding and St Bernard of Clairvaux, all active in the early Twelfth Century when Bonnevaux was being constructed - was to put into practice a more disciplined adherence to Benedict’s prescripts.

In the 1120s, the doctrines and practices of the new order were still in the process of formulation. St Stephen Harding’s Carta Caritas (1119) and the works of Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, who had only founded Clairvaux a few years earlier in 1115, were inspiring renewed vigour and enthusiasm within monasticism.

The Cistercians went on to become the pioneering inspiration behind the spread of monasticism within France, northern England, Wales and parts of Spain. Their teachings emphasised the importance of manual labour as an integral part of daily life alongside a stricter observance of Benedict’s requirements for lectio and spiritual practice. The Order’s contribution to the culture of technology and

architecture of Medieval Europe was immense.

While we have little knowledge of the daily life of the monks of Bonnevaux we do know that the Abbey’s lands incorporated many of the local farms and villages many of which that can still be identified today – Beauvais, Cadoue, Tarcay, Moulin-Garnier, Bouchaudrie. It can be assumed that while much of the land belonging to the Abbey was later let under feudal terms to tenants, in the early years much of the estate will have been worked by the monks and their lay brothers. The Abbey had rights of justice in the area and is reported to have an annual income of 4,000 livres in the Thirteenth Century.

St Benedict set great store on the requirement to demonstrate hospitality of the highest order. The Abbey lies barely a kilometre east of one of Middle Ages’ best used pilgrimage routes to Compostella. There are several starting points for Le Chemin de St Jacques de Compostelle within France. The Via Turonensis (starting from Tours) was probably the busiest passing through Poitiers, Bordeaux and Les Landes on its way to Spain. It was this branch that skirted the lands of The Abbey.

While there were other religious houses located on the Route, Bonnevaux was close enough to imagine that pilgrims would look for hospitality and shelter from the community as they made their way along the route.

The Abbot was the key figure in the Medieval Monastery, setting the tone for worship and lives of the Brothers, providing leadership for the community. The Duputies put together a listing of the Abbots of Bonnevaux – It is incomplete and we know nothing of many of the Abbots listed. But the tentative list includes:

Fulcon or Foulques 1147

Guidon 1155

Geoffoy 1195

Arnaud

Adhemar

Aimery 1285

Jean 1 Cardinaut 1423 -1463

Noel Voyeur 1465 -1472

John II 1476 – 97

John III du Cozie 1506

Charles of Montjournal 1507 -1516

Rene de la Roche 1530 -1544

There are only a few brief references to the Abbots in the various archives. Aimery is named as Abbot when Hugues, Comte de la Marche, made a land donation towards the end of the Thirteenth Century. And in 1432, when King Charles VI founded the University of Poitiers, tribute was made to the support received from John, Abbot of Bonnevaux, renowned for his great knowledge.

A Papal Visit

Known as Philip The Fair, the Capetian King Philip IV of France, (reigned 1285 -1314) was one of the key figures who helped transform France from an assemblage of feudal fiefdoms to a more centralised modern state.

For a King with such ambitions, the power of the Church within his territories was a constant irritation. As the Thirteenth Century drew to a close, Philip found himself increasingly in conflict with successive Popes (and with the Holy Roman Emperors who saw themselves as defenders of the Church).

As Philip struggled to finance wars against the English and, even further afield planned a new Crusade in alliance with the Mongols, he increasingly turned to taxation of the Church and of the clergy to provide him with the income he needed.

Pope Boniface VIII resisted Philip’s plans and two Papal Bulls, Clericis Laicos of 1296 and Unam Sanctum of 1302, were early assertions of Papal Supremacy and defiance to royal aspirations. Philip sent delegates to confront the Pope and, while probably not killed directly by physical assault, Boniface died during the ensuing stand-off. He was briefly succeeded by Pope Benedict XI but he was not in good health and a further Papal election was soon necessary.

It was in the light of these events that Philip intervened in the election of the new Pope and secured the election of a French cleric, the Archbishop of Bordeaux, Bernard de Goth as Pope in 1305.

The new Pope took the name Clement V and, in the light of the support he had received, moved the Papal seat from Rome in 1309 to become the first Pope to be based at Avignon.

While Avignon at this time was not formally part of France (it was situated in the Imperial territory of Arles) this was the beginning of what became known as the Babylonian Captivity of the Papacy. Clement and his immediate successors were beholden to the French King.

Whatever the deficiencies in Clement’s election process, the legitimacy of his appointment to the Papacy was not formally disputed but within 70 years the divisions between Rome and Avignon were irreparable and the late Fourteenth Centuries Avignon Popes were seen as schismatic Anti-Popes.

But that all lay in the future when Philip decided in 1307 to summon the newly established Clement V to meet him to discuss important matters of mutual interest. Clement consented and Poitiers was appointed as the venue for this momentous formal meeting between Church and State. Clement slowly made his way North along the Via Turonensis.

And so it was that in April 1307 Clement broke his journey and arrived at the Abbey at Bonnevaux. He stayed for four nights preparing for his encounter with the King. To receive a visit from the Pope would have been a unique experience for the Abbey but unfortunately we know nothing of the details of the visit.

Philip, having in the previous year 1306 expelled the Jews from his territories, was focused on having Papal support for an attack on the Knights Templar – the monastic military order that had huge influence in Southern France - and to whom Philip was significantly indebted.

Clement gave his approval for the suppression of the Knight’s Templar, paving the way for an active persecution of the Order. The Pope’s visit to Bonnevaux can be seen to have played a small part in the process that determined the fate of one of the major symbols of knightly power in Medieval Europe.

But as we move towards the Sixteenth Century we enter an age of notable religious unrest. Ominously, the Order lost the right to choose the Abbot. In 1544 the right to appoint the Abbot at Bonnevaux passed to the authority of the abbot sponsors under the notorious commendam system. From now on Abbots were appointed in the King’s name. They might be religious or laymen, and in many cases were largely interested in the income generated by the estate. A period of turbulence had begun.

5. THE YEARS OF TURBULENCE

As Protestant teachings took hold across Northern Europe over the course of the Sixteenth Century , faith became the crucial definer of identity, defining allies and crystallising enmities.

In France it was the teachings of the Frenchman, Jean Calvin, based in Geneva, that captured the zealous devotion of people from all sectors of society, inspiring the growth of the Protestant Huguenot community and challenging the traditional faiths of the people.

This period of religious conflict coincided with a period of weakness in the monarchy. With the death of Henry II in 1559 his widow Catherine de Medici, having to act as Regent to two young sons who succeeded to the throne in a relatively short period of time, found herself in the middle of bitter court battles between the competing interests of the Guise faction (pro-Catholic) and the Bourbons (pro-Protestant).

1562 witnessed some of the most bitter conflicts of the early years of the French Wars of Religion. The Edict of January authorised limited Protestant worship, but the Guise faction engineered a massacre of Protestants at worship in Wassy, east of Paris. Orleans and the Loire Valley area were the focus of deadly rivalry.

Bonnevaux found itself immersed in the religious turmoil of 1562 (see below) and, even when stability was restored, it was not untouched by these conflicts. There is evidence that the Abbey

suffered significant physical damage as the religious conflict continued to rage over the course of the second half of the century.

The Protestant Abbot

One of the first Abbots appointed to Bonnevaux after the right of appointment passed to the Crown through the abbot sponsors in 1544 was Guichard de Saint Georges.

We know very little about him except that in 1562, the very year that the tide of Protestant protest began to most keenly felt in Mid-France, he embraced the Protestant faith.

Not only that, he and the brothers joined the 1562 Huguenot storming of Poitiers. The city was captured and the chronicles of the time bewailed the fact that during the short period of Huguenot occupation the body of St Radegonde, which had been preserved intact for ten centuries was burnt. (She had been a Frankish Queen of the Sixth Century who founded the Abbey of the Holy Cross at Poitiers – her remains are still enshrined in The Church of St Radegonde in the city).

The Huguenot success was short-lived and so was Guichard’s tenure at Bonnevaux. He was swiftly replaced as Abbot by a distinguished stalwart of the Catholic Church – Jacques Garnier, already over eighty years old and who had seen service as a Canon of Notre Dame de Paris, Treasurer of SaintHilaire Le Grand in Poitiers, Auditor of the Archbishop of Bordeaux. He was to die at the age of 87 in 1567.

At this distance in time we cannot know what may have motivated Guichard de Saint Georges to embrace the Protestant cause. Did he experience a crisis of Faith and become a devout follower of Calvin’s teaching? Or did he see an opportunity for advancement in the service of the new cause?

The historian R J Knecht who has written extensively on the Sixteenth Century Wars of Religion notes, “Some may have used religion as a pretext to seize a neighbour’s property, to harm a business rival or to pay off a private debt.” We have no personal information on Guichard de Saint Georges so we can come to no conclusion on his motivation. Another mystery left by the absence of records…

The Edict of Nantes of 1598 is seen as bringing about an uneasy period of co-existence between the Catholic and Protestant populations.

We know little about Bonnevaux in the Seventeenth Century. But we do know that the Abbey’s rental income stagnated and that there was litigation over late payments of debt.

The Duputies identify the commendatory Abbots of the period (largely absentee Crown appointments):

- Louis Garnier de la Sauvagere (1613)

- Jacques 1 Garnier 1613-1657

- Jacques II Garnier 1670-1680

- Pierre de Baglion de La Salle, Bishop of Arras 1690-1710

Dom David Knowles describes how, following the revival prompted by The Council of Trent, communities at St Vanne and St Maur, sought to reinvigorate Benedictine practice but little of that seems to have impacted life at Bonnevaux.

As the Eighteenth Century progressed and France basked in the pomp of the ‘ancien regime’ of the Sun King, Louis XIV, there is evidence that the religious life was no longer an attractive option to young men. The spirit of Enlightenment, and eventually radical dissent and anti-clericalism, come to prevail.

A report of 1769 to the Bishop of Poitiers recorded that there were at this point only two religious resident at Bonnevaux. The Parish Priest at Marcay complained, “They do no work, do not regularly say Mass, never say vespers in the chorus, not even on Easter.”

But while Bonnevaux may have been experiencing a period of spiritual malaise, works to improve the physical condition of the Estate continued.

For reasons for which there is no obvious explanation, in 1715

it was the Abbess of The Abbey of Sainte-Croix in Poitiers who commissioned significant restoration and improvement works for the Abbey Church at Bonnevaux

Later, in 1752, a new commendatory abbot was appointed –Benjamin Frottier de La Coste Messeliere. While the religious life of the Abbey may not have prospered under him he was clearly a persistent and accomplished manipulator of the Royal bureaucracy.

With patience and persistence he persuaded The Forestry Administration in Paris to give permission to fell a considerable proportion of the surrounding forest in order to pay for refurbishment of the Church, the Monastery and parts of the outlying Estate. Within the final years before the Revolution, Bonnevaux benefited from a huge investment and significant rebuilding and improvements were completed.

6. A SECULAR INTERLUDE

We have already seen how Benjamin Frottier de La Coste Messeliere, the last Commendatory Abbot of Bonnevaux, had persuaded the dying vestiges of the ancient regime to invest in the property. He was to prove no less adept at dealing with the revolutionary administrations from the late 1780s onwards.

The abolition of the monasteries under the revolutionary government was swift and certainly as far as Bonnevaux was concerned efficient. In November 1789 the Assembly had declared the property of the Church at the disposal of the nation and in 1790 the Religious Orders were abolished.

There were still only two monks resident at Bonnevaux at the point of abolition. The Prior, Dom Joncque, was appointed to the parish of Saint-Georges de Vivonne. He performed one Easter Mass in his parish in 1791 and then disappeared.

But Frottier de La Coste Messeliere fared much more successfully. He managed to be appointed President of the Regional Ecclesiastical Committee charged with liquidating the goods of the clergy and disposing of Church lands. Using an agent he was then able to purchase the Abbey of Bonnevaux – and all its ancillary lands – early in 1791 at a favourable price. Ironically, it appears that having been a non-resident Abbot, shortly after abolition he become a resident owner.

Entrepreneurial though he had proven himself, when he died in 1806 his widow needed to dispose of Bonnevaux swiftly to raise funds and the estate passed through several hands before being bought in 1838 by Dominique Gaborit de La Brosse, a member of the de Montjou family. The family was to occupy Bonnevaux for over a hundred years.

The Nineteenth Century was largely a period of serenity and stability for Bonnevaux. Dominique’s son, also named Dominique, inherited the estate in 1848 and it was under his ownership in 1854 that the Church was demolished and the chateau constructed incorporating some of the remains of the original Monastery. He served as Mayor of Marcay from 1871 and died in 1882 at the age of 62.

The Estate became renowned as a centre for the breeding of Parthenaise cattle, a distinctive breed especially valued for production of “Charente-Poitou” butter and for the quality of the beef they provided. The Estate regularly won awards at the Concours Agricole Generale de Paris.

As well as family members, the 1876 census recorded nine living-in servants. This would have been in addition to the garden and agricultural staff who would have lived away from the main house.

Dominique’s son, Edgard de Montjou, had a long and distinguished life in public service. As well as serving 58 years as Mayor of Marcay (1884-1942), he served several spells as a CentreRight deputy for Vienne at the Conseil Generale of the Third Republic, serving from 1902 to 1906 then in an unbroken period from 1910 to 1932. He died in 1942, a Chevalier de La Legion D’Honneur. His wife, Anne, died in the same year. The association with the de Montjou family ended with the death of Edgard’s daughter-in-law, and after a couple of short term owners the property passed to the Segeron family in 1969.

7. THE ABBEY AT BONNEVAUX

We have no visual images of the Abbey dating from the monastic years. And only a small proportion of the medieval buildings are now standing in a form that give us a clear picture of what the Medieval Abbey looked like.

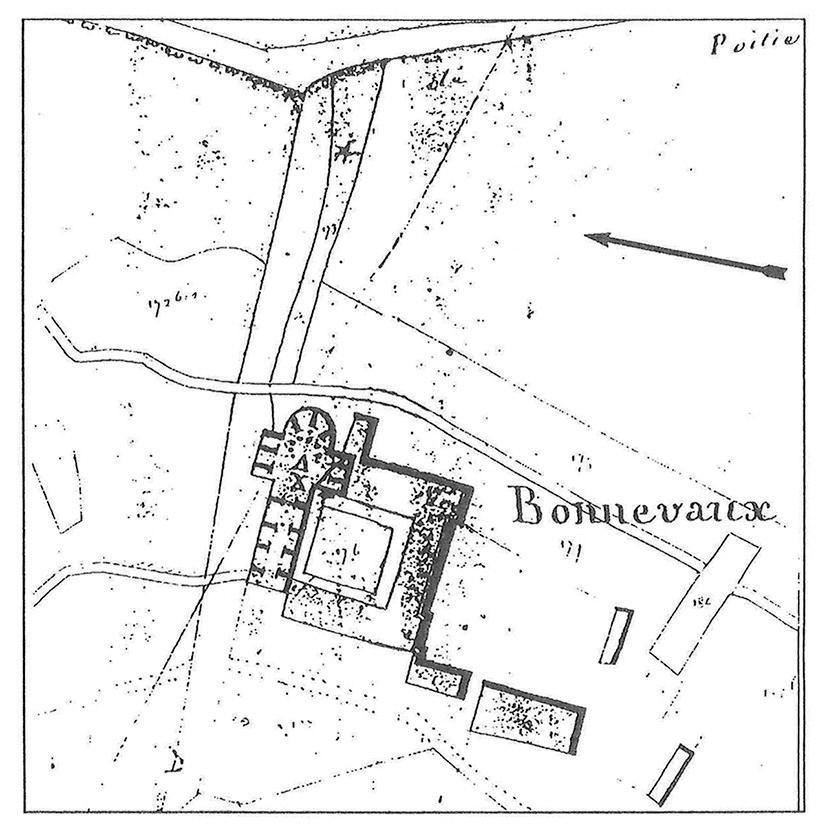

The most reliable visual source of information on the disposition of the buildings of the Abbey is the Cadastral Plan of 1824. Established as part of Napoleon’s codification of government, the French cadastral maps were drawn up to depict and identify property ownership for tax purposes. They are still published annually in each municipality. While they do not purport to be detailed plans of building and estates they do give some viual image of the footprint of buildings.

The 1824 Plan gives us a helpful overview of the footprint of the Abbey before the radical rebuilding of the mid-Nineteenth Century took place.

The current chateau was built over the remains of the main monastic building and the Abbey Church was demolished. Much of the stone of the medieval building was re-used and a number of internal features of the original building were incorporated into the new building including:

Plan of the Abbey at Bonnevaux, 1824

- A well opening up into the current refectory in the West Wing

- The huge fireplace located on the ground floor of the East Wing may carry some echoes of the calefactorium of the original Abbey

- The maze of storerooms and ovens at the end of the East Wing

- The stone spiral staircase in the West Wing where the eroded steps give witness to the footsteps of so many silent witnesses across the years called to worship at the various hours of the day and night.

More obvious than any of these is the preservation of the one gallery of the medieval cloister. As well as serving as the setting for many monastic activities, the cloister was the main link between the main building and the Church. In the re-building of the 1850s what would have been the southern walk of the cloister was retained and incorporated into the northern façade of the chateau.

It is estimated that the cloister measured 35 square meters and that the internal walks were four metres wide. The surviving

walk provides an architectural feast to the observer – being an amalgamation of the original Twelfth Century arches and stonework, topped by a Fifteenth Century vaulted ceiling and standing on a tiled Nineteenth Century floor. The Monastic Church would have stood at the northern end of the cloister. It is said to have been very similar in structure to the contemporaneous churches built at Fontaine-leComte and Le Pin Beruges.

The Duputies report that, in his work ‘The Old Frescoes of The Churches of Poitou’, the historian Longuemard recorded “The regularly oriented church had only one nave … Two transept arms with lateral chapels and cupolas on the crossing of the transepts with the nave were visible on the side of the semi-circular apse. On the south side, at the height of the corresponding transept arm, rose the sacristy which communicated directly with the nave.”

The Church was 58 metres long by 10 metres wide with the transepts measuring 28 metres. The Sacristy which was converted into a Chapel and is still in place and used in meditation sessions, measures eleven metres by 5 ½ metres and would appear to comprise the original walls combined with Fourteenth Century vaulting.

The Nineteenth Century renovations also saw the creation of a dominating Stable Block also built using stones from the original Abbey and the demolished Church. Other outbuildings on the higher ground of the Estate may have stood as part of the Abbey’s working environment. If we bring together what we can see in the surviving buildings at Bonnevaux with our understanding of how the medieval Monastery worked we can see the most important building on site was the Abbey Church. It was the site of the communion of the monk and divine. As an Abbey Church in an isolated location the Church at Bonnevaux would have been austere and simple. The highly decorative décor of the Cluniac Monasteries had given way to an ascetic architecture devoid of liturgical excesses.

The Church would have been separated into very distinct

enclosed sections. The 1824 Plan seems to show that there was a significant barrier across the nave – perhaps a stone screen. This would have served to separate the choir monks from the lay brothers who would only have had access to the west end of the church. There was no provision for nor any expectation of participation from the local lay community.

It is likely that there would have been a night stair from the South transept – over the east walk of the cloister leading to the monk’s sleeping quarters. The cloister would have been the centre of daily life of the community. In the Southern walk, up against the north wall of the church, would have been the collation seat where the Abbot would have led readings from the approved literature. Off the eastern walk would have stood the Chapterhouse where the daily reading of a chapter from the Rule of Benedict would have taken place and where the business meetings of the community would have taken place. The lay brothers did not participate in these occasions but the non-glazed openings would have allowed them to hear what was going on.

The monks’ living areas would have been at the eastern end of the main building. In the high medieval period the monks would have slept in their habits on straw-filled mattresses in one common room- the dormitory. It was only at the end of the early Middle Ages – perhaps the Fifteenth Century or later that the notion of individual cells came to prevail.

The refectory and kitchen would have been off the northern walk while the lay brother quarters were at the western end of the buildings.

There are some outbuildings showing in the 1824 Plan but without further information it is not possible to identify if these represented the infirmary or perhaps specialist workshops if the brothers at Bonnevaux specialised in specific agricultural or craft activities as some monks in other locations did.

The Daily Life of The Medieval Monk

Before the widespread use of clocks the lives of all Medieval peoples were given routine and shape by the rising and setting of th sun. The life of the monk was dictated by the season of the year and the movements of the sun no less than was the life of the peasant working the land.

There was a notion of the ‘horarium’, a pattern of activities and worship defined by the hour of the day, but if there was no reliable way for the individual members of the community to know the exact time there would have been local variations in the observance of the offices.

St Benedict identified seven canonical hours of lauds (dawn), prime (sunrise), terce (mid-morning), sext (Midday), none (mid-afternoon), vespers (sunset) compline (retiring) and night time observance of vigil.

The Rule made provision for inevitable differences between summer observance and winter observance.

In both seasons matins were expected to be observed in the middle of the night (probably about 1.30 am) but after that the differences in the seasons dictated the shape of observance.

In summer the pattern might be as follows:

3.00 am – Lauds

4.00 am – Prime which might be followed by Chapter and Mass

9.00 am – Terce

11.00 am – Sext

Lunch

3.00 pm – Nones

6.00 pm – Vespers

Collation

7.30 pm – Compline

8.00 pm - Retiring

Whereas in Winter the patterns might allow a further rest after Matins then:

7.00 am – Lauds

Mass

8.00 am – Prime

9.30 am – Chapter followed by Terce

11.00am – Sext

2.00 pm – Nones

Lunch

3.30 pm – Vespers

Collation

4.00 pm Compline

4.30 pm – Retiring

Given the commitment that the day should be devoted to worship, reading and labour there was clearly little time for work tasks in the winter period. Given that the standard monastic community would have comprised probably twelve religious, it can be seen how crucial the lay brothers (who were only expected to attend two religious offices during the day) were in performance of the tasks required for a community to function.

It should also be noted that in the strict observation of Benedict’s Rule the members of the community were not expected to eat meat, to drink alcohol or to indulge in bodily comforts like baths.

It was a demanding regime and the distinguished English historian of monasticism, Dom David Knowles speculates that it was the decline in strict observance after the intense period of expansion of the Twelfth Century that saw the slow decline in the monastic life – rather than working the fields themselves the communities became landlords dependant on the rents of their tenants, they became richer and observance of stricter regimes weakened, the system of commendatory appointments led to weakened leadership within the communities.

We do not have the information that allows to pinpoint these shifts in the life of the community at Bonnevaux but it is clear that the communities of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries had little of determination and discipline of the pioneers of the earlier centuries.

1. WCCM AT BONNEVAUX

The Abbey at Bonnevaux is the international meditation and retreat centre of The World Community for Christian Meditation (WCCM).

The revival of meditation and contemplative practice within the Christian communities has been a significant feature of the last half century. There has been a number of inspirational figures and teachers who have developed an understanding of the power of meditation, demonstrated how it can enhance spiritual practice within Christian worship and can enable common ground to be found with adherents of many world faiths.

The inspiration behind the development of WCCM is to be found in the simple, but profound, teachings of John Main OSB (1926 -1982)

This is not the place to recount how John Main’s ministry and teachings, supported and developed by Father Laurence Freeman, his pupil, friend and successor, have inspired Christians across the world. These matters are well documented in publications and resources available from WCCM.

It is sufficient for the moment to understand that fewer than ten years after Father John’s death, Christian Meditation was being practised across the world and a structure for supporting this expansion was needed.