Our

Rogues, Sinners and Saints

Afrikaner,

Afrikaner,

Copyright © 2024 by James Green

All rights reserved.

No portion of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher or author except as permitted by Australian copyright law.

This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information regarding the subject matter covered. It is sold with the understanding that neither the author nor the publisher is engaged in rendering legal, investment, accounting or other professional services.

While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties concerning the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and expressly disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation.

You should consult with a professional when appropriate. Neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, personal, or other damages.

Edited by Dedrie Green and Callum Scott; Fatal Impact Productions.

2nd Edition 2025.

Book Cover: Charles Collier Michell. Boers; Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boers

This book is lovingly dedicated to all the Afrikaners, Indigenous People and Enslaved People we are connected to in our family trees, especially the cherished living members of the Green and Beukes families.

May you embark on this journey through our shared history, experiencing both the joy and the heartache I encountered along the way. As you explore the distant and immediate past, I hope you discover echoes of our common ancestors within yourselves, perhaps even recognising threads of their spirit in your own life.

You may indeed share strands of DNA that bind us together across generations!

My mother and father met in January 1946 at the traffic lights in front of the Johannesburg City Hall. They were married a week later, and I was born in November 1946. By the time I was eleven, four more siblings had joined our family.

To support the Green family, my father worked on mining projects, moving from one small town to another, while my mother was busy raising the rapidly growing family.

The mining and industrial towns were lively and filled with activity, surrounded by the untouched veld. We grew to love the pristine African environment right at our doorstep. In those days, living on the right side of the Apartheid ‘colour bar’, the towns and rural areas were safe we had the freedom to roam and explore the veld without restriction.

My father had a captivating charm when he was sober, but his struggles with PTSD from the war led him to rely on alcohol. When he was drunk, he became violent; the family suffered because of this. In those days, such violence was all too often brushed aside and hidden from view. Although it was a challenging dynamic, it encouraged us to seek understanding and find healthier ways to cope with adversity.

My father struggled with something else; he lacked education and had grown up in an impoverished environment. His mantra was, ‘I needed to get out of there and make something of my life’. This rubbed off on us.

He put tremendous pressure on his sons to excel academically his daughters were exempt from this pressure! My mother, on the other hand, was a loving and gentle soul who encouraged us to write good essays for school and shared the most captivating stories with us. My siblings and I have a vivid imagination and write well, which may be attributed to my mother’s influence.

Education in our Apartheid community was authoritarian and conservative. We had excellent teachers in all subjects except history, where we were inundated with the National Party government's biased perspective on 'white' history. My parents, who supported the Nationalist Party, were never overtly racist.

Thanks to a mining company, I was able to attend university on a bursary, where I studied Chemical Engineering and eventually earned a PhD. This paved the way for an academic career, followed by a corporate career in synthetic fuels during the thriving South African economy of the 1960s and 1970s.

My wife, Dedrie, qualified and worked as a Speech Therapist in South Africa, then as a Mathematics and Physics Teacher after obtaining an Honours Degree in Physics while raising our two children, Peter and Hilda.

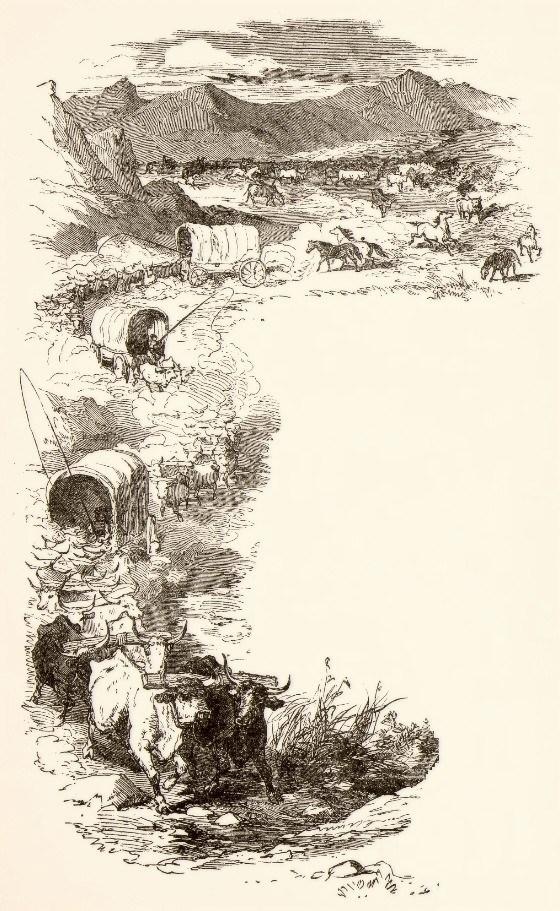

In 1987, we took a significant leap and emigrated to Australia, concerned about becoming second-class citizens in the emerging ‘Rainbow Nation1.’ We never looked back and have enjoyed living in the ‘Lucky Country.’ My wife, Dedrie, had a fulfilling teaching career in Australia, while I worked for an oil and gas company. Later, we teamed up to start a risk management company, assisting companies in lowering their risks in the chemical, oil, and gas industries.

COVID-19 turned life upside down, leaving me feeling trapped at home in Melbourne, Victoria. In the midst of it all, my only escape was my computer and long discussions with my wife, Dedrie, and our Chihuahua. This downtime gave me an opportunity for reflection, encouraging me to dig into our South African family history and uncover the captivating, yet complex narrative of our past.

As I gathered the compelling stories of our ancestors, I discovered deeply moving tales of resilience and reinvention. They spoke of courageous individuals desperate for safety, daring adventurers propelled by their ambitions, and those who confronted danger with unwavering strength. Each narrative reflects the extraordinary circumstances that led individuals to make remarkable, yet often regrettable, choices to survive.

These narratives include our own family story, that of the Green family family members that we knew and loved and who had difficult and tragic lives. Our descendants may thank us for passing on these stories, as well as the stories about our struggles in the days of Apartheid.

We have not concealed our own Green family stories of family violence, violence and mental health issues, painful as they are in the retelling; neither have we hidden our stories of suffering in the explosive racial environment in the Apartheid state.

I believe that sharing these experiences can help the reader connect with us; don’t we all have such stories to tell? Telling our own stories of violence and abuse is as necessary for healing as are the stories told by the Aboriginal and Indigenous Peoples around the globe.

Throughout my research, I immersed myself in the rich tapestry of our ancestral history. I discovered a varied cast of characters: some were rogues and renegades, while others wielded considerable influence as 'movers and shakers,' and a few became symbols of resistance, even martyrs. That is the reason for the title of this book: ‘Rogues, Sinners and Saints Our Afrikaner, Indigenous and Slave Ancestors.’

This collection of stories was inspired by the extensive historical records found in South African and Dutch genealogical archives. My research skills proved valuable in this shift of focus from technical to historical and genealogical literature.

Genealogical programs such as 'My Heritage,' 'Geni,' and 'Family Search' provided a wealth of information and helped me build many branches of our family tree. I verified most branches against birth, marriage, and death certificates available in the databases.

I used various resources for my research, including books about our ancestors who migrated to the Cape from the seventeenth century onward, as well as postgraduate theses from several universities in South Africa and the Netherlands. Additionally, I consulted newspaper archives that documented some of my ancestors' crimes and political involvements. The stories are primarily organised chronologically, starting from 1600, with referenced materials cited throughout the book.

As you explore these accounts, it may be necessary to overlook and occasionally forgive the embellishments inherent in reconstructing our ancestors' lives. Deciphering ancient records, often mere fragments found on weathered parchment, demands creative interpretation. Nevertheless, a captivating narrative remains enjoyable, even if embellished for the sake of enduring empathy, enjoyment and entertainment.

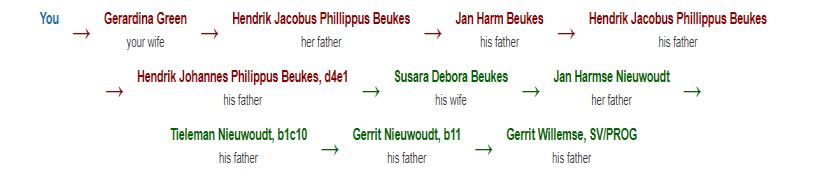

Each ancestor belongs to a specific branch of either Dedrie's (my wife's) or my family tree. Like most Afrikaners, we are somehow related through the family trees. I am distantly related to Dedrie as well, through the Beukes family trees. Dedrie’s Dutch family tree intersects with her South African one in the late 19th Century. There are many fascinating rogues, sinners, and saints in her Dutch ancestors that I could have included, but I have limited it to a few with whom I had immediate access.

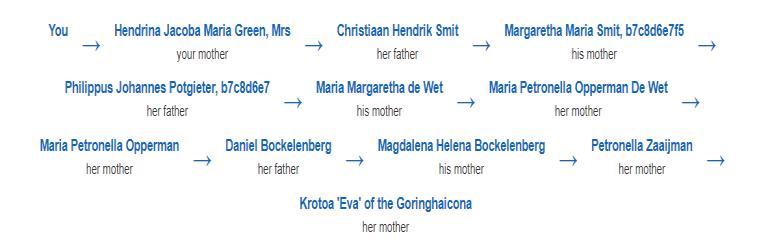

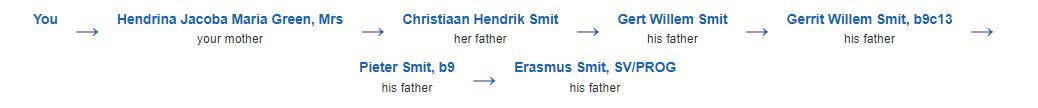

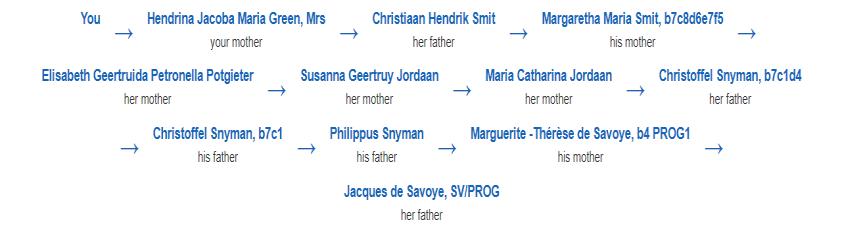

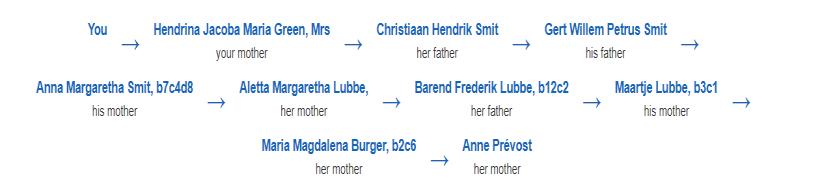

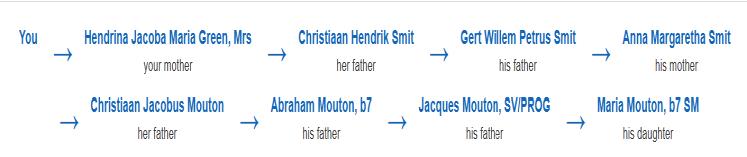

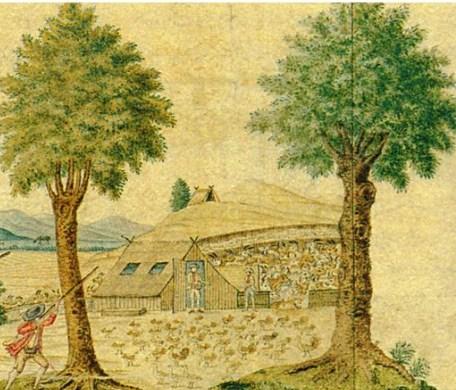

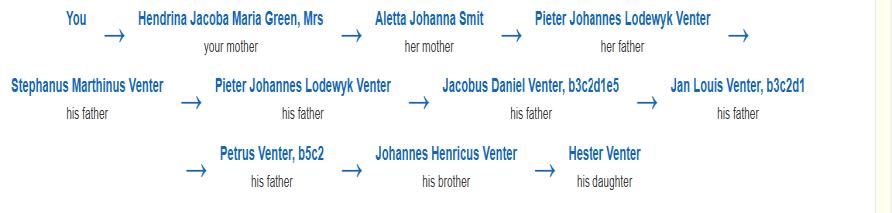

At the end of each story, I have included the branch of the family tree, taken directly from the Geni.com database. An example of such a branch is given below.

The research into our ancestors gave me a different perspective on the history that our teachers and historians taught us. During our impressionable years, we were brainwashed and indoctrinated by our family, relatives, the church, academics and politicians, into believing that we ‘whites’ were the ‘Herrenvolk' a master race, superior to the Indigenes and African tribes.

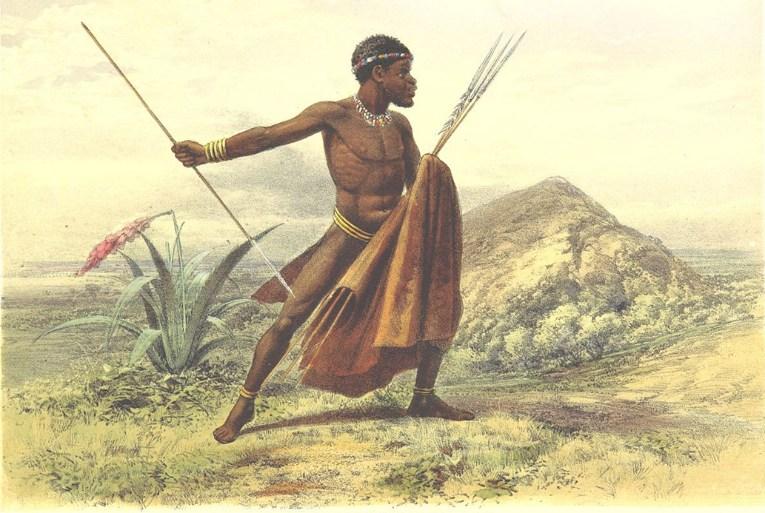

Those were the days of ‘grand Apartheid.’ We were led to believe that the Indigenes were savages, merely a step above the baboons that roamed the veld but were able to learn simple concepts and needed to be brought into the Christian fold. We also were led to believe that the African tribes were primitive pastoralists, bad farmers, and fierce warriors, very superstitious and believed in witchcraft.

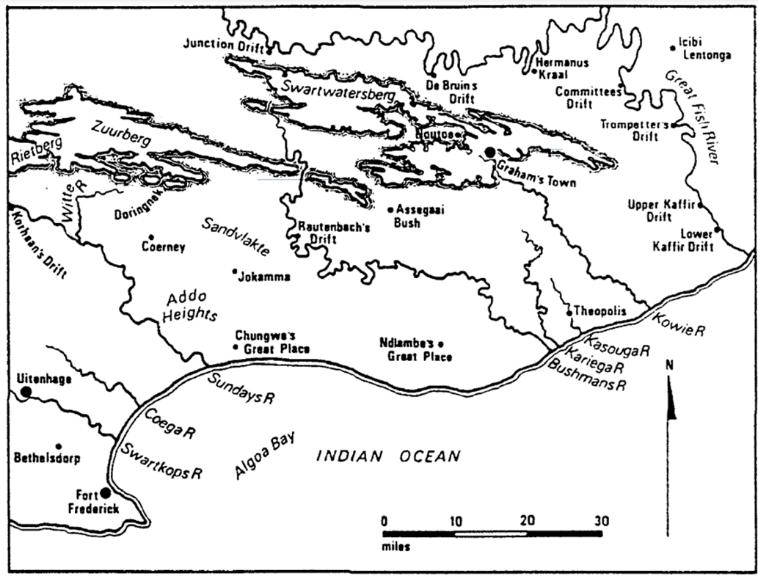

The information collected in our research verified that our forebears were constantly at war with the Indigenous communities and pastoral African tribes, all vying for the same land and resources. The information also revealed the complex cultural and social dynamics at play between the communities.

The stories in this book have given us a new historical perspective. The Indigenous people and African tribes had a richness to their culture and wisdom far greater than what we believed. Their land and environmental management practices were far superior to those of the colonisers.

It’s a sobering thought that many of our ancestors were also slave owners and that some of the slaves were our very own ancestors. It also dawned on me as my research progressed that I was an Aboriginal person, in the Australian sense of the word. In Australia, a trace of Aboriginal DNA qualifies one as Aboriginal.

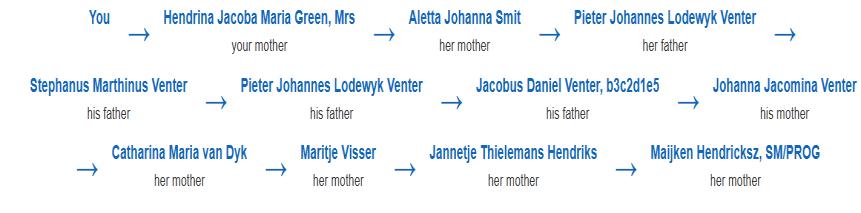

I have added figures throughout the text for illustration purposes. The references that appear throughout may slow the reader down, but they are necessary to confirm the veracity of the stories. These references are found in the Bibliography.

Dutch, Afrikaans and other foreign language terms and derogatory terms are italicised. Most of these terms are explained in the Bibliography and References Section, Page. 281. Where italicised terms are not explained in the Bibliography and References section, they are explained in the text. Some of the italicised Afrikaans terms appear in most English language dictionaries as well. Zulu, Xhosa and Ndebele names and terms are italicised. Many terms that were previously considered acceptable during the Apartheid era have evolved into language that reflects contemporary social and political values. Ship names and the Afrikaans or Dutch names of farms are italicised.

The Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie–or VOC2) played an enormous role in the lives of our first ancestors who arrived at the Cape.

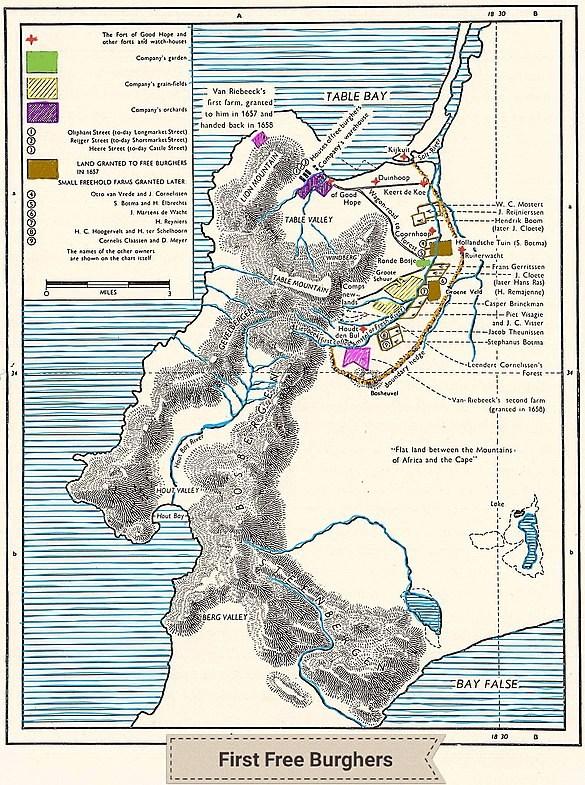

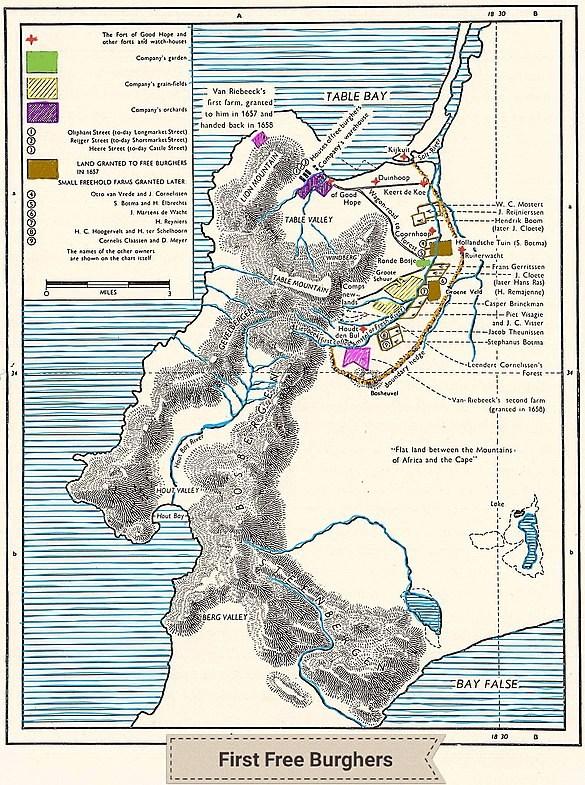

The VOC established a refreshment station at the Cape in 1652 for several reasons. The Cape provided a strategic halfway point for VOC ships travelling between the Netherlands and the East Indies, allowing for rest, refuelling, and replenishment of supplies. The station served as a crucial source of fresh water, vegetables, and meat for VOC ships, enabling them to resupply and continue their long voyages.

The VOC was my ancestors' curse! But, without the VOC, I would have no stories to tell. Also, there could be no story without slavery3 . Like many families around the world whose ancestors owned slaves, we see our ancestors as slaves themselves, who were chained to the dictates of a morally corrupt power. Some of those slaves were our ancestors! I have uncovered stories about our early slave family member, Groote Catrijn and a slave employed by my ancestor Gerrit Smit September van Bugis.

Then, there is the story of the VOC's relationships with the Indigenous Khoekhoen4 people, particularly Eva van Meerhof a servant of the founder of the refreshment station, Jan van Riebeeck, and employed by the VOC as an interpreter. I am sure that there are more stories to be uncovered about the San5 and Khoekhoen people in our family trees!

Founded in 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands, the VOC emerged as the pioneer of modern corporations and a global juggernaut with unprecedented power. Operating beyond the confines of legality, it waged wars, imprisoned dissenters, and administered gruesome forms of torture and execution (Figure 1 below).

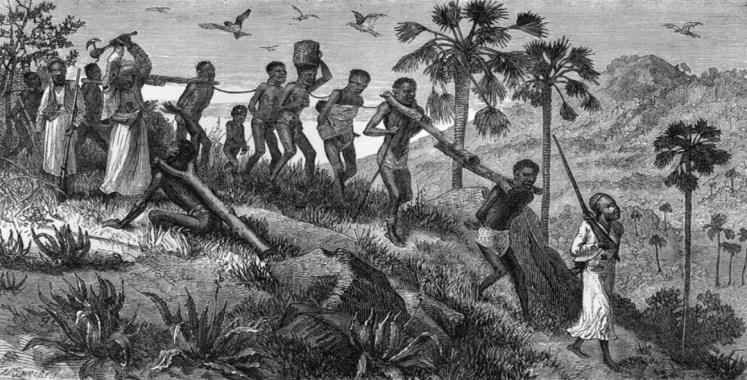

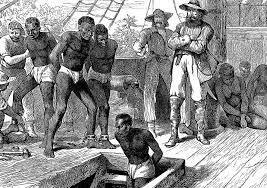

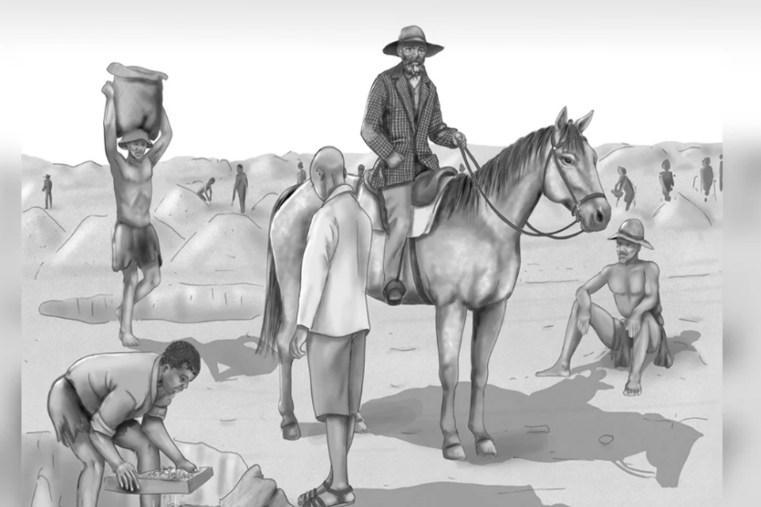

Beyond its mercantile exploits, the VOC delved into the abhorrent trade of human lives. Enslaved people became commodities, trafficked across continents for profit. Viewing themselves as superior beings, the VOC's

controllers ruthlessly exploited this human misery to amass wealth and resources. To them, enslaved people were mere spoils of war, traded in markets scattered across the globe to meet the insatiable demand for labour (Figure 2 below).

Not only that, they sent large numbers of slaves to keep their new refreshment station alive7. These hapless people built the colony with blood, sweat and tears some were our first ancestors.

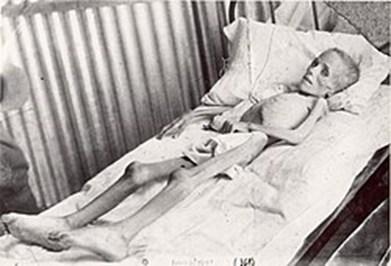

The brutality of slavery under the VOC knew no bounds. Enslaved individuals toiled under the lash, enduring unimaginable suffering in their quest for survival. Punishments for minor transgressions were severe, with whippings and forced labour on Robben Island being commonplace.

Such harsh measures were aimed at deterring rebellion and maintaining control, with the VOC sparing no cruelty to uphold its authority.

In rural areas, slaves faced the harshest treatment. Forced to toil in wheat fields and vineyards, they endured relentless beatings and backbreaking labour, often to the point of exhaustion and death. Those who survived the incessant punishment were cast aside in their old age to become shepherds. They broke them in body and spirit and reduced their lives to remnants of their former selves.

The VOC emerges as the quintessential antagonist in these narratives, shaping the destinies of my ancestors with its insatiable greed and brutality. Yet, amidst the darkness, it also inadvertently gave rise to heroes and martyrs, individuals who stood defiant against its tyranny. Thus, while the VOC looms large as one of history's most malevolent forces, it also serves as a testament to the resilience and courage of those who dared to resist its oppression.

Many South Africans, particularly Afrikaners, may find it both surprising and unsettling to discover that some of their earliest ancestors were, in fact, slaves. This revelation can evoke a range of emotions, as it challenges longstanding perceptions of identity and heritage. During the Apartheid era, such lineage would have tragically influenced social classification, labelling individuals as ‘Non-white’ or ‘Coloured.’ It's a poignant reminder of the complex and often painful history that shapes our understanding of who we are today.

It came as a surprise to me that Groote Catrijn9 , my ninth great-grandmother, is a slave ancestor who entered the world in 1631 in Bengal, near the bustling city of Chennai, India.

Her origins remain shrouded in mystery. She may have been born into slavery or later captured and enslaved by the Dutch. Some speculate she hailed from a lower-caste Indian family, while others suggest her family may have been prisoners of war. Regardless, historical documents reveal that the VOC transported Groote Catrijn from Pullicat to Batavia in 1645 alongside 2117 other enslaved individuals. Batavia, once the grand hub of VOC operations in Asia, is now present-day Jakarta, Indonesia.

In Batavia, Groote Catrijn found companionship with Claes van Malabar, another enslaved individual under the ownership of the VOC's stablemaster at Fort Rijswijck.

Despite the laws prohibiting such unions, Groote Catrijn and Claes lived together as a de facto husband and wife.

Tragedy struck on the afternoon of October 8, 1656.

A seemingly innocuous dispute over a meal escalated into a violent altercation that resulted in Groote Catrijn fatally injuring Claes. Groote Catrijn had arrived at the stable in the fort's garden with a pot of cooked chicken and pork for them to share, a meal that Claes had requested. However, Claes ‘politely’ informed her that he had already eaten and was not hungry. Groote Catrijn, who had a short temper, became agitated. She grabbed him, shook him, and called him a ‘stupid motherfucker.’

The fight escalated.

An enraged Claes fought back and threw her to the ground. She feared that he would rape her, which had happened often. In a blind fury, Groote Catrijn turned her body around and rolled away before he could fall on top of her. She managed to grab hold of a heavy, sharp piece of cobblestone. In an instant, the robust woman hurled the stone, aiming at his testicles.

The stone hit him with considerable force, just above the pubic area. The sharpened end penetrated his bladder, sending a stream of blood and urine onto the floor. Claes, bleeding profusely, lay writhing on the floor.

People rushed outside to stop the fight. Groote Catrijn shaking and shaken up was arrested on the spot, and they

took the injured Claes into the infirmary. Four days later, on the night of October 12, 1656, Claes died.

Arrested and charged with murder, Groote Catrijn faced a grim fate. The VOC Council of Justice, meticulous in its record-keeping, documented her sensational trial. Yet, amidst the looming spectre of execution by strangulation, a glimmer of hope emerged. Groote Catrijn exercised her right to appeal, ultimately leading to a remarkable turn of events.

On November 18, 1656, Governor-General Joan Maetsuyker reviewed her case and granted her a pardon. The reasons for this clemency remain a matter of speculation, but it spared Groote Catrijn from the gallows. Instead, she received a sentence of exile to the Cape of Good Hope, where she would spend the remainder of her days as a company-owned enslaved individual.

Thus began Groote Catrijn's new chapter at the Cape, where she became the first recorded female slave convict. Despite the hardships she faced, she displayed remarkable resilience, serving as a washerwoman for several commanders and their families within the confines of the fort.

Yet, her story took another unexpected turn with the arrival of Hans Christoffel Snijman, my ninth greatgrandfather, a soldier stationed at the Cape. Hans's duties included being a sentry at the Fort De Goede Hoop, the forerunner of the Cape Town Castle. Like Hans, I, too, experienced the monotony of sentry duty at the Cape Town Castle during my military service in South Africa. Hans

would leave his post to find some entertainment. He would sneak out every night and go to Groote Catrijn's living quarters. This behaviour did not go undetected!

Hans's clandestine rendezvous with Groote Catrijn led to his downfall, resulting in a conviction for fornication and subsequent banishment to Robben Island. Tragically, he perished there, leaving Groote Catrijn to raise their child, Christoffel Snijman, my ancestor. Despite facing further scrutiny and trials, Groote Catrijn found solace in the pardon of Governor-General Joan Maetsuycker, allowing her to rebuild her life and eventually marry a freed slave, Anthonij Jansz van Bengale.

Yet, fate dealt a cruel blow, claiming the lives of Groote Catrijn and her family in a series of tragic events between December 1682 and February 1683. Amidst the devastation, Christoffel Snijman emerged as the sole survivor, later marrying a European Huguenot woman, Margot de Savoye, my ninth great-grandmother from Ghent, Belgium. Thus, through triumph and tragedy, Groote Catrijn's legacy endures, woven into the fabric of my ancestry.

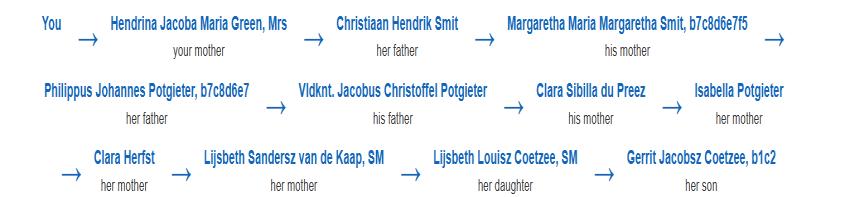

Our relationship with Groote Catrijn10 .

‘Eva’

Many South Africans, particularly Afrikaners, may also find it both surprising and unsettling to discover that some of their earliest ancestors were, in fact, Indigenes. This revelation can evoke a range of emotions, as it challenges longstanding perceptions of identity and heritage. During the Apartheid era, such lineage would have tragically influenced social classification, labelling individuals as ‘Nonwhite’ or ‘Coloured.’ It's a poignant reminder of the complex and often painful history that shapes our understanding of who we are today.

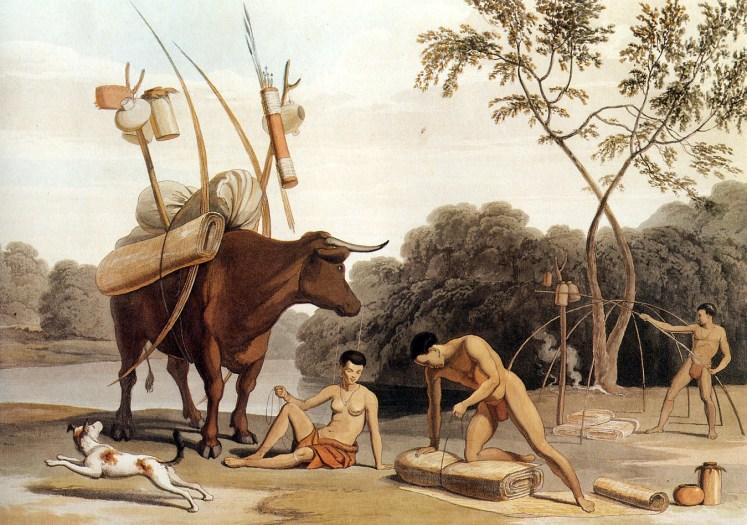

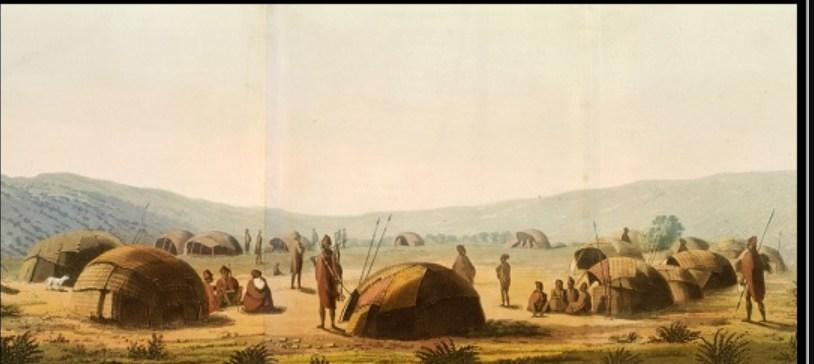

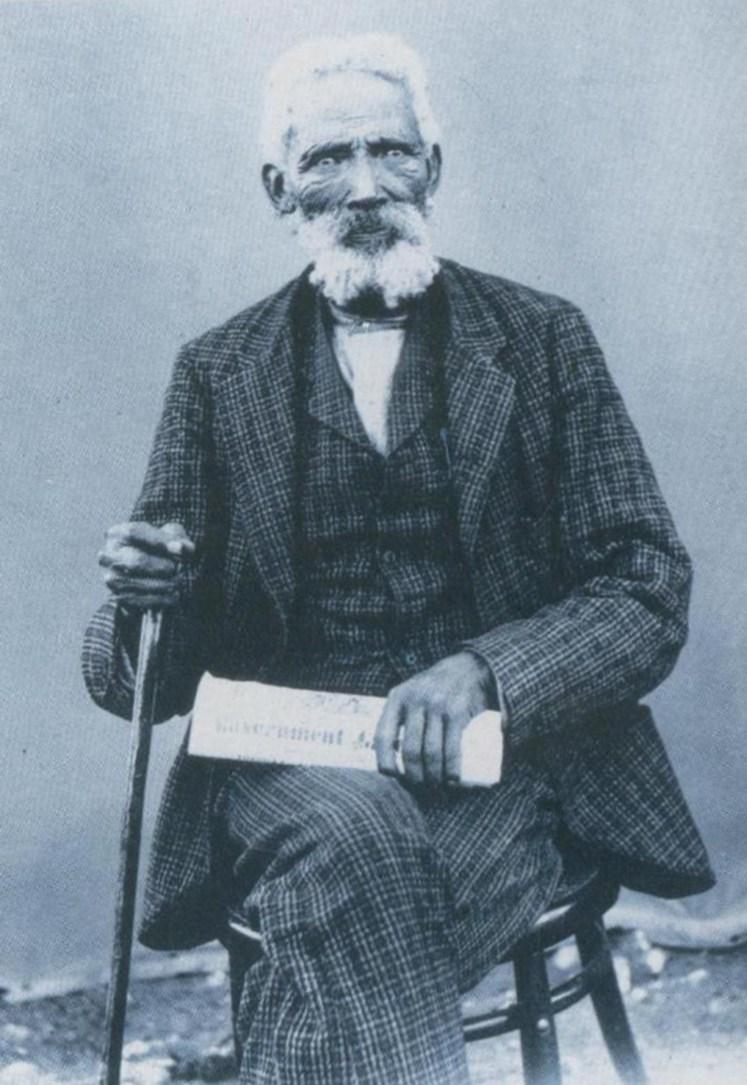

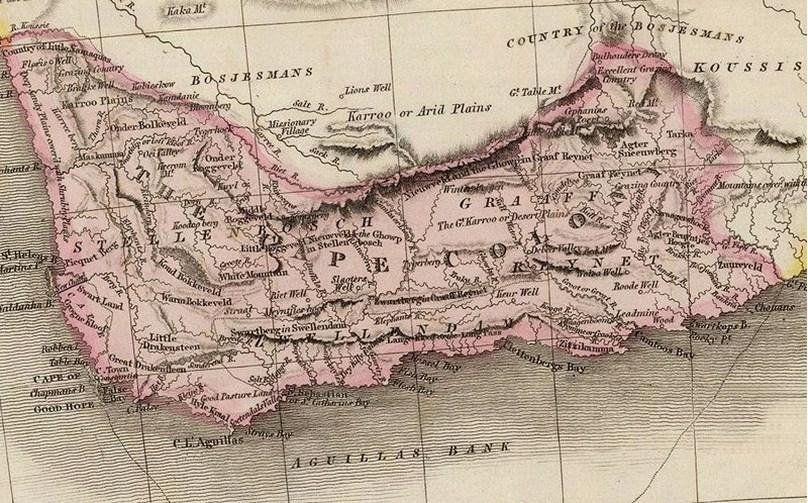

Krotoa11 (Figure 3 below), one of my ninth greatgrandmothers, affectionately known as ‘Eva’ among the early settlers at the Cape, holds a special place in our family tree as one of our Indigene ancestors. She hailed from the Khoekhoe or Hottentot12 people.

Figure 3: Krotoa13 - 'Eva.’

Krotoa was born into the Strandloper (also known as the Goringhaicona) clan, made up of wanderers from other clans (Goringhaiqua, Gorachoqua, Cochoqua) who settled at the Camissa River mouth in Table Bay to trade with passing ships under the leadership of her uncle Herrie. She also enjoyed a special relationship with the clan that her sister married into – the Cochoqua.

Yet, the story of Eva is a complex one, being retold by ‘Rainbow Nation’ historians. Although she is widely recognised as part of the Khoekhoe community, early descriptions of these people, taught in our history classes in the Apartheid era, placed her in the intriguing category of

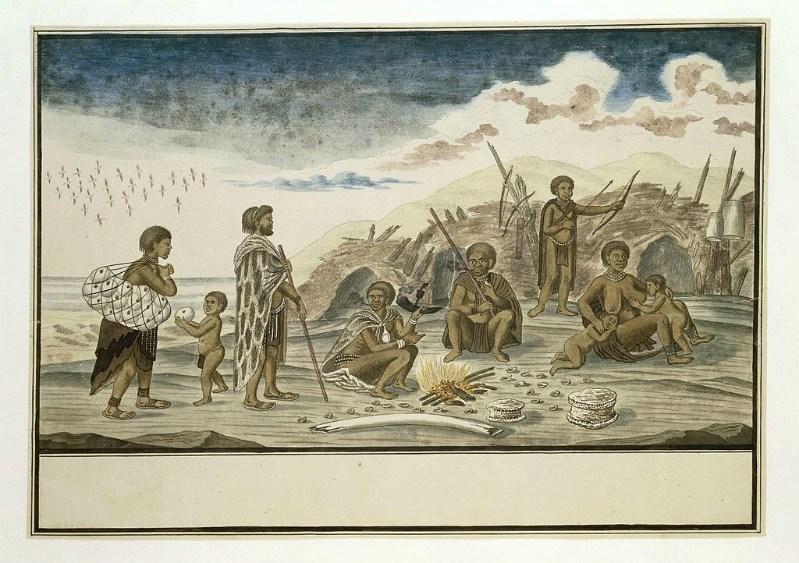

the so-called Strandloper ‘savages’. The first VOC Commander, Jan van Riebeeck called them wretched, miserable Calibans14 naming them the ‘Watermen’. They supposedly had no cattle and lived on mussels, roots, and herbs dug out of the ground.

The ‘Rainbow Nation’ historians unveil another narrative about Eva, her family, and the Strandlopers. This story has also changed my view of my ancestry and my identity as an Afrikaner bearing an English name. I, too, am ‘Coloured.’ I, too, have Strandloper blood; it comes up in my DNA! With ancestries being revealed by historians and genealogists nowadays, many ‘White’ Afrikaners would have to become comfortable with being labelled ‘Coloured.’

But Eva was far from being an ordinary Strandloper. She emerged as a latter-day celebrity known for her association with Jan van Riebeeck, the first VOC Commander of the Cape. Her name graced the pages of VOC journals and diaries as early as 1652, making her one of the most extensively documented women in early South African history. Notably, she was the first woman to be mentioned by her Khoekhoen tribal name in the early European records of the Cape Town settlement she was ‘Krotoa’.

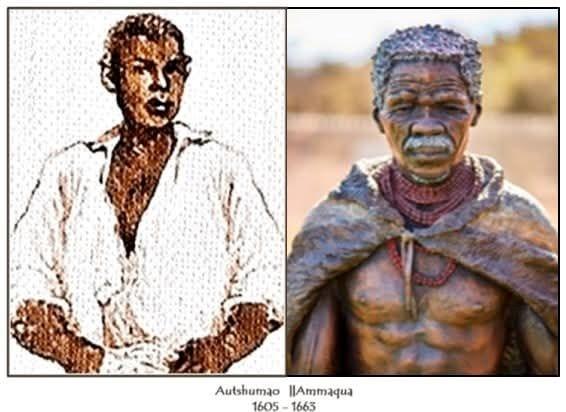

To truly grasp the depth of Eva's story, we must journey back to her uncle, Herrie Autshumao15 , of the Strandlopers clan, who lived on the shores of Table Bay, near the present-day Cape Town Castle also my 11th great-uncle. ‘Herrie’s’ story is equally fascinating.

But what did we know about these early ancestors?

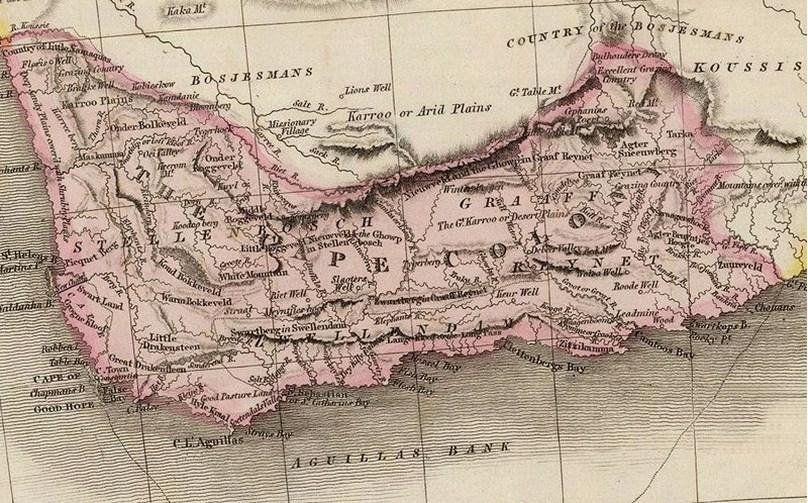

I attended Wynberg Boys' High School, located on land that was once home to the Khoekhoen. There, I had the privilege of learning history from an outstanding teacher who navigated the history syllabus mandated by the Department of Education in the Cape Province. Our textbook was full of the exploits of the Europeans and the spice trade but presented the Cape as a largely uncharted territory before the arrival of Jan van Riebeeck. It was inhabited by the Khoekhoen pastoralists, Strandlopers, and Black pastoralists in the interior.

Unfortunately, these groups were labelled as 'savages', pre-medieval beings Herrie’s Strandlopers were placed at the bottom of the hierarchy. Although our teacher in the 1960s offered a differing perspective, he told us to adhere closely to the textbook to ensure we passed the exam.

Before van Riebeeck arrived, surprisingly, many ships16 rounded the Cape of Good Hope in the era before the VOC established the refreshment station in 1652. We weren’t taught that. We knew our European history well, that, in the 17th century, the East Indies was a vibrant marketplace, where English, French, and Dutch VOC ships ventured across the seas to trade silver, gold and manufactured goods for spices. The VOC dominated this trade, with Batavia now modern-day Jakarta serving as its hub.

In Batavia, the air was rich with the aromas of pepper, nutmeg, and cloves, alongside textiles, tea, coffee, and ceramics. This dynamic city was the heart of a vast trading

network that connected Asia, stimulated cultural exchange and an era of exploration that would shape the world.

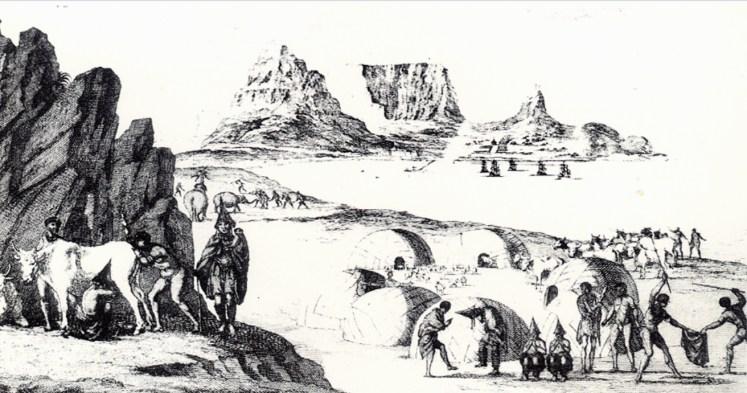

We now know that Herrie played a major part in the early development of the port of Cape Town. Contrary to our history textbooks, Cape Town was a bustling port long before van Riebeeck's arrival. Patric Tariq Mellet17 , with Melissa Steyn, tell us that the Strandlopers and other Khoekhoen people contributed substantially to establishing the port. So, Jan van Riebeeck was not the hero figure stepping into a land filled with awe-struck savages (Figure 5 below). The Khoekhoen and Strandlopers were not childlike, primitive beings speaking in rapid clicks, that were close to the sounds that animals and birds make.

Herrie’s role was truly remarkable. He was a key player in the port's growth.

In the early 17th century, the waters around the Cape were a hub of maritime activity, with Dutch ships stopping frequently. English ships also began to arrive in increasing numbers, with their presence growing significantly between 1610 and 1620.

With this surge, the English began to seriously consider colonisation, recognising the untapped potential of this halfway point around the Cape. Rather than simply pursuing colonisation, at which they were good at, they chose to invest in the local port infrastructure and establish a cooperative relationship with Herrie and the Strandlopers.

Herrie, a young man in 1630, frequented the harbour in Table Bay with his clan members. They would see ships18 entering Table Bay (Figure 4 below) and move to the shore to meet the people19 leaving the ship at the docks or arriving on shore by boat. He would stand out, waving, welcoming, with a huge smile on his face. He made friends with all and sundry, particularly the English and caught the eye of those managing stevedoring and chandlering operations.

5: Savages ‘Herrie’ Autshumao, Jan van Riebeeck and Watermans20 .

The friendship grew until the English decided to develop a stronger relationship with Herrie and his 60-strong Goringhaicona (Strandlopers). The Strandlopers, who had by that time settled on the banks of the Camissa river (a river that now runs under the city) and beach, were to remain there until the arrival of Jan van Riebeeck some 20 years later.

The Cape in Herrie’s day was vibrant and bustling. Picture two to three ships arriving monthly in Table Bay, their crews flooding ashore for stays ranging from a few days to over a week. European visitors speaking diverse languages and goods were a common sight, challenging the notion of a land filled with savages, barely more advanced than the wild animals that inhabited the peninsula, the seashore, and the slopes of Table Mountain. When he returned from Vietnam, Jan van Riebeeck’s entire fleet spent weeks in Table Bay in

a port that had the amenities and facilities to accommodate the visitors from the ships.

Patric Tariq Mellet21, a Cape Town-born heritage activist, provides a fascinating insight into the importance of the port before the arrival of Jan van Riebeeck Herrie’s stamping ground:

Each European power seemed to have had their own trusted man who performed a range of tasks, including keeping mail and passing it on to other ships. Ships had even developed a gun-signal protocol for summoning their hired hands.

But let’s stop and look at some of the dynamics of the Dutch and other European shipping of this magnitude. Let’s also look at the probable impact on the Khoena and then lets also keep in mind the improbability of the cock ‘n bull history that has been handed down to us over the years, with the collaboration of our academic institutions.

There are detailed records from that time that show how competitive the Europeans were and the dominance of the VOC. The ships underwent design changes to make journeys safer and to increase the size and types of cargo carried to South and Southeast Asia. There were many economic losses and deaths on the ships. This led to improvements in shipbuilding technology and the development of stopping points, which transitioned from basic refreshment posts to ship repair facilities.

The primary purpose of the shipping was to transport company officials and large numbers of troops to support the wars in South and Southeast Asia. The Dutch were engaged in conflicts against the English, Portuguese, and Muslim Sultanates, necessitating the reinforcement of their factories and significant bases in India, Sri Lanka, and Batavia.

Factories lined the Indian and Bengal Coasts, extending from Myanmar to Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, Malaysia, Taiwan, Japan, and Indonesia. The Dutch East India Company, with state powers granted by the Dutch States General, relied on thousands of troops who required time ashore at strategic stops. Long voyages often led to illness, grumpiness, and conflicts among soldiers and officials. By 1615, it was certain that troops had already taken shore leave at the Cape of Good Hope.

The English first tried to set up a trading colony at Table Bay using freed convicts and local cooperation, even bringing Chief Xhore to London. That early settlement failed, but Xhore then became an important trade facilitator for several European powers, though he refused to work for the Dutch and was killed by them. To replace him, the English supported Harry (Herrie), taking him to Jakarta for orientation and then helping him become the main trader for ships passing the Cape, first on Robben Island and later near the Camissa River.

So, Herrie and his co-workers were not the docile savages (Figure 6 below) with a few sheep and cattle to trade for a few trinkets and a bit of cloth.

In 1630, he journeyed to Banten (Bantam) in Java with the English, where he picked up English, French, and Dutch. He also gained experience in chandlering helping supply ships and their crews with provisions and equipment and stevedoring loading and unloading cargo from ships.

But ‘Herrie’ also saw how badly the VOC treated the locals!

Herrie was highly skilled as a trader and port master. The many ships arriving regularly at the Cape required excellent management skills and good facilities. Apart from trading activities, the ships often needed repairs. There were workshops with the necessary equipment to repair the ships, often severely damaged in the storms that frequent the Cape.

Large numbers of soldiers and officials needed accommodation and entertainment on shore all managed by Herrie. People needed care; sickness was rife, and sick people were often left behind, cared for by the Strandlopers.

The shrewd and astute ‘Commander22’, as he became known, was also a good linguist and politician who played off the English against their enemies, the VOC. He also served as a good buffer between the European traders and the Khoekhoen23 along the west coast and the interior, who had large herds of thousands of cattle and sheep.

We can only imagine what the scene on the docks was like for ships24 arriving. Herrie dressed in European clothes (Figure 8 below) would boldly step out to meet the ships’ crew. ‘The Governor’, mentioned in English, French and VOC letters and diaries, would be accompanied by the

Strandlopers with bleating sheep, lowing cattle, colourful baskets brimming with fresh fruit and vegetables, and barrels gleaming with clear water would be carted to the ships.

‘Herrie’, ever the charismatic chandler, would have moved seamlessly between English, French or Dutch and the melodic clicks of the Strandloper language.

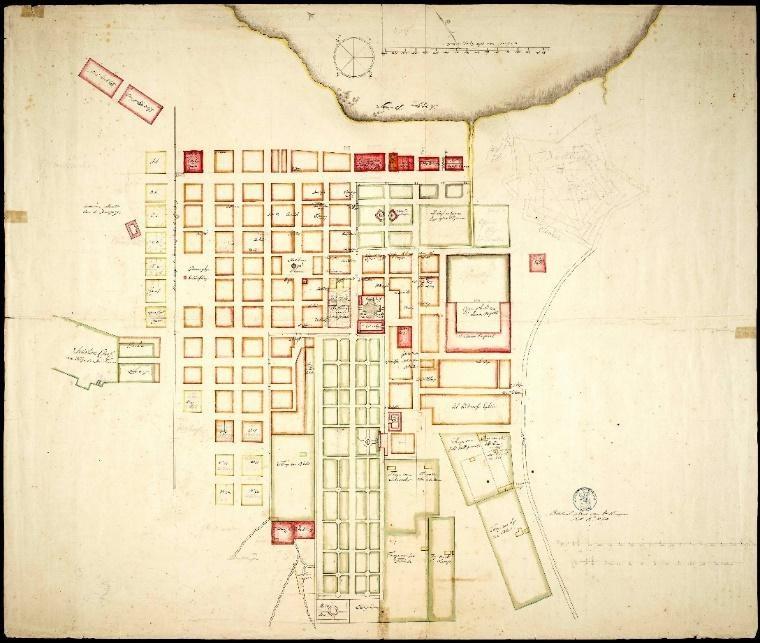

On the 7th of April 1652, Jan van Riebeeck landed at the Cape. The VOC, authorised by the Dutch States General, established the permanent settlement and took over the administration of services and the natural resources of the port.

Upon arrival, his initial tasks included establishing a fort the ‘Fort de Goede Hoop’, improving the harbour

facilities, planting crops like cereals, fruits, and vegetables, and obtaining livestock from the Khoekhoen people.

The first people that Van Riebeeck met would have been Herrie and the Strandlopers. Painter Charles Bell,25 over two hundred years later (Figure 5 above), imagined that that first meeting was between civilised Europeans and a bunch of savages. This is also what we believed, told by our historians and teachers. We thought that the Strandlopers were slightly more advanced than the baboons who frequented Table Mountain.

Herrie was immediately demoted no longer the ‘Commander.’ Van Riebeeck put his stamp on all proceedings from henceforth, but he still used and manipulated Herrie as translator and go-between the VOC and the Khoekhoen clans. Unlike the British, the VOC had a cunning policy in their dealings with the Indigenes, probably learned in Batavia. Van Riebeeck’s approach was, as noted in his diary, ‘First to creep and then to go…to win their favour…and to draw them to us.’

Van Riebeeck’s diary mentions the giving of ‘treats’ many times presents of tobacco, a ‘bellyful of rice,’ and ‘as much arrack or brandy as they could drink.’ There was no goodwill in this matter. Here is a typical extract that explains the VOC approach:

Gave them some tobacco. More bread, rice, and arrack should be at hand, as they draw the natives towards us, who continually say that the English gave them whole bags of bread, much tobacco, and whole cans filled with arrack and wine we ought, therefore, to be better provided to outdo the English if we wish to draw the natives towards us, otherwise

not an animal will be had, which may, if natives are humoured, cost so little that we could afford to add to the price some bread, tobacco, wine, or arrack." When we remember that the price given per head for cattle was ordinarily two copper plates, and for sheep "as much tobacco and wire as the sheep is long with the tail.

‘Herrie’, said Van Riebeeck:

Likes the English better than he does us a characteristic of most natives who have tried both being always full of them no doubt he has persuaded the natives to keep their cattle back until the arrival of the English, as he seems to know pretty exactly when their fleet will be here from India.’

Herrie, though, refused to be the submissive Khoekhoen that Van Riebeeck wanted. Like Van Riebeeck, he was also a cunning businessman feathering his nest. He did not easily give up his position as the ‘Commander’ at the port people still listened to him, liked him, and they missed the daily parties down at the docks.

Herrie wanted to be the sole go-between the VOC and all the Khoekhoen clans in the Cape Peninsula and, indeed, right up the west coast. However, he was thwarted by Van Riebeeck, who had studied tribal politics in the region, knew who was jealous of whom, and which clans and tribes hated each other. Van Riebeeck discovered that they mostly disliked each other. He got to know all the tribes with the following picturesque names:

The Saldanhars’ (Saldanha being the Portuguese captain who had given his name to this region in the 1500s); the Gorachouquas (the tobacco thieves); the Chainouquas; the Hesaquas; the regular Dagga-

makers (marijuana-makers) of the Hamcumquar; the Namaquas, and many more.

He realised that the Khoekhoen would do almost anything to get hold of tobacco, copper, and arrack brandy. He cleverly used their greed and their hatred of each other to serve the interests of the VOC. He had several good Khoekhoe spies in the fort to do his dirty work.

The VOC became increasingly suspicious of Herrie and tried to outsmart him by banishing him to Robben Island from time to time and bringing him back again when they needed him. But his wealth continued to increase, and they could not determine how he continued to line his pockets at their expense.

Van Riebeck’s distrust showed in his diary: ‘Herrie was also in the fort pretending that he had urged the natives now here (in the fort) to bring cattle; we pretended we believed him.’ The VOC finally decided to cut him out of their dealings with the other Khoekhoen clans completely and started to build up their local herd of cattle and sheep.

The VOC had to guard the cattle and sheep pens day and night. The Khoekhoen were masters of deception. Both parties were. They played games with one another while they raided each other’s herds of cattle and flocks of sheep. This was to become a familiar theme in South African history ‘We’ll steal your stuff if you steal ours.’

In the year 1653, tension reached a boiling point on a tranquil Sunday morning, the sun shining down on the fort,

as VOC officials sat listening to a sermon. Outside the tranquil walls, a shocking scene unfolded. A herd of fortytwo cattle prized milch-cows and sturdy draught oxen were peacefully grazing under the care of a young herd-boy. Suddenly, chaos erupted! The ‘Watermen’ swooped in. They ruthlessly murdered the boy, stealing silently away with the cattle. The refreshment station had been struggling; the herd of cattle had been their hope for survival.

A rumour started to spread that Herrie was the brain behind the chaos. It was said that just as the sermon reached its climax, he pulled a disappearing act worthy of a magician, leaving everyone scratching their heads. Soldiers were dispatched to chase after the nimble ‘Watermen’ (Strandlopers). They trudged through the heavy sand of the Cape Flats, huffing and puffing, while the ‘Watermen’ and their cattle made a graceful exit over the hills, laughing all the way to the horizon.

It was an awful blow to van Riebeeck. ‘We have lost the pantaloons being unbreeched’, he says in his diary and by the “Watermen” too, whom we had kindly treated. Besides, we have been cruelly deceived in our interpreter Herrie, whom we had always maintained as the chief of the lot, who had always dined at our table as a friend of the house, and been dressed in Dutch clothes.’

On one occasion, about five or six years after arrival, Van Riebeeck was looking for certain cattle thieves. They decided to get Herrie on the job: Van Riebeeck’s diary states with duplicity: ‘Herrie will therefore be brought over from the island and employed for the purpose, but well secured.

Golden promises as big as mountains will be made to him, but none will be held binding.’

Herrie helped them find the perpetrators. They welcomed him back into the This was typical of the commander’s political morality. Herrie must have helped them because somehow, he was welcomed back into the settlement. But Herrie must have been involved in the thievery, because Van Riebeeck wrote, ‘When they freed him, he was trembling like a lapdog owing to his bad conscience.’

But Herrie was always suspected of being the key person behind the raid on the VOC herd in 1653. They were just waiting to garner sufficient evidence to corner him. In 1658, they resurrected the 5-year-old cold case against him. He was tried in a summary kangaroo court and sentenced to life imprisonment on Robben Island that took Herrie from hero status to zero. They confiscated his wealth. The VOC had had enough. They made plans to insulate the settlement from Khoekhoen thievery. That was probably the start of Apartheid in South Africa.

Just before the arrival of Van Riebeeck, Eva came onto the scene. Herrie was riding the crest of the wave at the port. This bustling, animated world became Eva's playground and classroom. From an early age, she followed her uncle like an inquisitive shadow, asking question after question that exasperated Herrie. Whether aboard ships or interpreting for traders, Eva had an uncanny knack for blurting out the right answers before Herrie could! But Herrie adored his pintsized assistant, who was always one step ahead even if that

step occasionally landed them in amusing misunderstandings.

Eva had a remarkable aptitude for languages, coupled with a keen intellect and sharp wit it was a family thing. Her education unfolded at what could be termed 'Docks University,' with Herrie serving as her esteemed professor and the thousands of sailors and VOC employees frequenting Table Bay as her language tutors. It was an immersive on-the-job training experience unlike any other.

Just before van Riebeeck’s arrival, as Cape Town thrummed with life, young Eva became a luminous presence on the docks, a linguistic prodigy who left the port workers and traders in awe. She shadowed Herrie, seamlessly helping him as an interpreter.

Eva’s aptitude for languages was nothing short of genius. She was Fluent in Dutch and Portuguese and had a working knowledge of English, French and Danish. Yet, her brilliance extended beyond European tongues. Thanks to her clan’s extensive trading networks with inland communities, she also acquired a deep understanding of various Khoekhoen dialects and picked up African languages when the slave ships started to arrive at the docks.

When Van Riebeeck arrived, it all changed. Herrie was no longer considered the ‘Governor’, yet the little precocious ten-year-old still helped with communication on the docks. Then the smallpox arrived. The port looked like a field hospital; the sick and dying were everywhere.

After the epidemic, Eva found herself as a housemaid in the van Riebeeck household within the fort. Here, she quickly proved her worth to the governor and the VOC managers and became known as the 'Oroǀõas' (Ward-girl) by the Khoekhoen clans. Soon, her command of languages elevated her to the role of van Riebeek's official interpreter.

Figure 9: Eva's People.

But Eva was more than just the interpreter. Eva was also the resident diplomat extraordinaire half linguist, half gobetween. She made herself indispensable to the VOC. For six remarkable years, she was the VOC's chief interpreter and negotiator, bridging the two unlike worlds with amazing skill.

She was first mentioned in van Riebeeck's diary in October 1657, where he noted, ‘The commander spent the day conversing with the Saldanhars, using a girl named Eva,

aged 15 or 16. She has served the commander's wife since the beginning and is mastering Dutch.’

On March 28, 1658, the VOC ship, the Amersfoort, arrived in Table Bay, burdened not with goods but with the profound weight of human suffering. Aboard were 174 souls shackled together; they were torn from their homes and families, shackled by cruelty and despair. The ship had intercepted a rogue slave vessel, capturing half of its human cargo a mosaic of voices speaking Portuguese and African languages like Umbundu, Kimbundu, and Kikongose. This linguistic diversity was another barrier, isolating them further in their misery, as the foreign shores of Table Bay offered a grim promise of backbreaking toil. This was the start of the slave trade to South Africa.

Eva accompanied VOC personnel on board to help with communication. As she watched the poor individuals disembark, the cries of the women filled the air, their wails resonating with a profound sadness. I believe it would have pierced her heart. She would have observed the grimaces etched on the faces of the men, their silent suffering evident as they were harshly prodded by the guards (Figure 10 below).

At that time, Eva was leading a double life. The friendly relationship between van Riebeeck and Eva began to slowly wear thin as he discovered that 'something was rotten in the Fort de Goede Hoop.’ He grew suspicious of her when he observed her conversing in whispered tones with Doman, a Khoekhoe Clan Chief temporarily living in the fort.

Doman had taken over from Herrie as one of the two interpreters employed by Van Riebeeck the other being Eva. Although Van Riebeeck’s diary said that Doman ‘ seems to be well-disposed towards us’ and ‘is serving the Hon. Company better than anybody else up to the present at any rate’ Van Riebeeck started to have grounds to suspect Doman.

Rijckloff van Goens, Van Riebeeck’s trusted advisor on defence and strategy, orchestrated a pivotal journey for Doman in April 1657, taking him to the bustling Dutch trading posts in Java. This was no casual expedition; its purpose was to immerse Doman in the commercial mechanics of the VOC.

However, the true impact of this voyage was far more profound. In Java, Doman bore witness to the harsh reality of Dutch imperial dominance local Bantamese communities, once free and proud, were now subdued under VOC rule. These scenes of resistance and subjugation had an impact on Doman, reshaping his perception of the VOC not as benign traders, but as a looming threat to the Khoekhoe way of life. His loyalty to the VOC changed.

Doman would be the leader in the first Khoekhoen uprising against the VOC. Eva was his trusted informant within the fort.

What sort of a game was Eva playing at the fort? She was such a manipulator Van Riebeeck was like ‘putty’ in her hands! Eva, with her sharp intellect and cunning, turned his flaws to her advantage. As a go-between the VOC and the

Khoekhoen commercially and politically, she danced a delicate line, adeptly concealing her daring, while pretending to be naive. When cornered, she wielded tears like a weapon, a poignant performance that often left van Riebeeck too exasperated to punish her. All he did was shout and curse her, leaving her unscathed and victorious.

Amid the pervasive corruption festering within the VOC, van Riebeeck himself was a rogue and as corrupt as those under his command. The culture of moonlighting where individuals indulged in shadowy, often illicit pursuits alongside their official roles was rampant throughout the VOC world. Punishments for those flouting company policy ranged from brutal floggings to torturous forced labour, even death if caught too many times. Van Riebeeck had narrowly escaped such disgrace in his prior post. He had salvaged his reputation through rigorous counselling and retraining and had to face VOC's ‘Performance Reviews’ much more frequently.

10: Dreadful Cargo26 .

Van Riebeeck followed VOC trading policy and practices rigorously, but was probably moonlighting, and was never caught; Eva was his key contact and go-between with the Khoekhoen. She was a key spokesperson for both parties in the initial vigorous trade with the VOC, exchanging livestock for iron and copper goods, tobacco, and beads. When this trade relationship deteriorated as the VOC took land from the Khoekhoen and wanted more livestock than the Khoekhoen were willing to provide, Eva was there to help negotiations.

She had to smooth ruffled feathers when rumours arose among the Khoekhoen that the VOC were intent on exploiting them and taking their land, as they had done in other parts of the VOC-dominated world.

Whose side was Eva on?

Van Riebeeck's diary entry, dated June 21, 1658, reveals his growing apprehension about Eva and her close

association with Doman—also, where did her allegiance lie? As the days passed, van Riebeeck's trust in the Khoekhoen dwindled rapidly. In one entry, he describes a complaint lodged by a man named Jan Reijnierssen, who reported that his male and female slaves had absconded overnight, taking with them blankets, clothing, rice, tobacco, and other provisions. Van Riebeeck turned to Doman, asking whether he knew the runaway slaves' whereabouts and whether the Khoekhoen would help to find them.

The verdict remains uncertain, but some online sleuthing suggests that Doman may have nonchalantly shrugged his shoulders, uttering, 'I don't know.' Such a response would likely have infuriated the egotistical commander. As fate would have it, Eva happened to be nearby, seemingly always within earshot of any significant commotion within the fort. The Commander may have thundered, 'Are our slaves not being harboured by the moerkneuker (motherfucker) Hottentots (Khoekhoen)!'

Eva, displaying remarkable composure, responded, 'Is this your opinion, Mr Commandant?' 'Yes!' he bellowed. She then continued in flawless Dutch, 'I'll tell you straight, Commander, Doman cannot be trusted. He divulged everything you said in your chambers the day before yesterday to the Hottentots. When I admonished him for it, he retorted, 'I am a Hottentot, not a Dutchman, but you, Eva, seek favour with the commander.' Now, my intuition tells me that the Fat Captain of the Kaapmans tribe is harbouring the slaves. '

Enraged, the commander demanded, 'What does the captain intend to do with those slaves?' Eva calmly responded, 'He plans to present them to the Cochoquas, another tribe, to maintain their alliance. The Cochoquas, in turn, will pass the slaves to the Hancumquas, a distant tribe.' The Hancumquas are known for cultivating the soil to grow dagga (cannabis), a dried herb highly valued by the Hottentots, who chew it for intoxication. Hence, they require slave labour to tend to their fields.'

Doman, possessing a shrewdness akin to Eva's, seized this opportunity to withdraw from the fort discreetly. His disdain for the Dutch had been festering, particularly since his travels to Batavia, where he had seen firsthand their ruthless treatment of the locals.

Tensions between the Khoekhoen and the settlers intensified. With Doman squarely in the VOC's sights, the Khoekhoen faced imminent eviction from their grazing lands, which they had frequented for centuries. Then, the conflict escalated!

In 1659, the European settler farmers voiced their concerns over escalating cattle theft, prompting an urgent council meeting with Jan van Riebeeck. Rumours swirled that Doman had allegedly incited the Gorachouquas (the tobacco thieves) to seize more cattle during rainy weather, exploiting the settlers' inability to use their flintlock muskets due to wet fuses.

In response, VOC reinforcements arrived, leading to further skirmishes. Despite the relentless efforts of the Khoekhoe, they proved no match for the formidable VOC

muskets (Figure 11 below). The conflict persisted for another year until all parties collectively realised that a ceasefire and truce were imperative. Just to be sure, the VOC built a fence to keep the Khoekhoen out (Figure 12 below).

During the war, Doman sustained severe injuries, while Eva unexpectedly reappeared in van Riebeeck's diary in January 1661. Van Riebeeck notes that Eva, the interpreter, returned to live in his house, abandoning her traditional skins and readopting the Dutch way of dressing. This suggests that she may have aligned herself with her people during the cattle conflict but resumed her services as an interpreter once hostilities ceased.

Van Riebeeck had a soft spot for Eva. Some historians suggest that there may have been some relationship between the little Strandloper and the commander. Van Riebeeck observed that Eva appeared to ‘grow weary of her people again.’ He graciously allowed her to return to the fort to resume her role as translator and go-between, saying, ‘to get better service from her.’ He concludes in a conciliatory tone, noting, 'She seems to have become so accustomed to the Dutch diet and lifestyle that she will likely never fully relinquish it.'

Eva's life dramatically turned in 1662 when van Riebeeck departed from the Cape, replaced by Commander Wagenaer. Eva was baptised and married a versatile Danish surgeon, who also practised as a barber Pieter van Meerhof my 9th great-grandfather. Pieter's skills were in high demand in the hazardous shipping and construction environment, where he often performed amputations, cut hair and trimmed beards.

Commander Wagenaer noted that Eva’s union was ‘The first marriage contracted here according to Christian usage with a native.’ The VOC allowed marriages between Europeans, Khoekhoen and freed slaves in those early days. A year later, Eva and Pieter van Meerhof and their two children went to live on Robben Island, where he was appointed superintendent and ‘pest controller’. Surprisingly, surgeon Pieter’s job was as a VOC pest control supervisor; he probably fell out with the administration. His job was to get rid of snakes, spiders and similar creatures.

But Eva was a complex person, full of contradictions. She emerged as a figure of fascination and controversy as she got older, revered by some and condemned by others. Her story laces together admiration and scorn, painting a vivid picture of a tragic life.

During Eva’s stay on Robben Island in 1673, a Dutch visitor to the Cape, Willem ten Rhijne, described her as a remarkable individual, 'a masterpiece of nature.' He noted her embrace of Christianity, her fluency in multiple languages, and her extensive knowledge of the Holy Scriptures. He commended her skill in various womanly crafts and highlighted her marriage to one of the company's surgeons.

However, Wagenaer offered a differing view in his 1671 diary entry. He described Eva as spiralling into selfdestruction, describing her as 'drinking herself to death' and condemning her for 'vile unchastity.'

The exact timeline of Eva's descent into alcoholism remains unclear. However, it's known that she was heavily

pregnant upon her arrival at Robben Island, and, according to various accounts, she was often drunk. During this chaotic period, there was serious family violence; Pieter reportedly beat Eva when she was drunk.

On one occasion, Pieter sought the help of a surgeon from the mainland after severely beating and injuring Eva. He claimed she had fallen off a chair and struck her head on a wall, resulting in a three-day coma with a fractured skull. The attending surgeon wrote that ‘such injuries are not typically associated with a simple fall from a chair.’

Pieter had many strings to his bow! He was deeply involved in the slave trade, voyaging to Madagascar to barter for slaves, then returning and engaging in sex in sex on arrival with an inebriated Eva. During his absence, another child was born, expanding their family.

Tragically, Pieter met his demise during one of his slaving expeditions in Madagascar.

Eva's brief marriage to Pieter, lasting only three tumultuous years, set the stage for a dramatic turn in her life. After Pieter's tragic demise, the VOC allowed Eva to leave the isolation of Robben Island and return to the mainland. But the world she returned to was far removed from the one she had once known a fractured, prejudice-laden society where she was no longer under the protective wing of the VOC. Now, Eva was left to confront these harsh realities on her own, navigating a landscape that had grown increasingly hostile and unwelcoming.

With 'illegitimate' children in tow, Eva faced rejection from the European elite, who now dominated the social hierarchy. She also had to find her place among the manumitted Blacks and transient lower classes, predominantly men. Despite these challenges, Eva found solace in her drinking companions and sexual partners.

Eva likely battled depression, increasingly relying on alcohol self-medicating a habit ingrained since her early years. She eventually spiralled into a life of crime, finding herself on the wrong side of the law. Her descent into darkness continued until the church intervened, removing her children from her care. Mansell Upham27 recounts how the church council accused Eva of drunkenness and engaging in animalistic behaviour at night, reverting to her 'native habits.'

In 1669, under the cover of night, VOC police, called by the church council, forcibly seized her three children while they were asleep. She heard them coming and fled from her dwelling, disappearing into the night. The police sealed her dwelling to prevent her from entering. Cornelius de Cretzir, the fiscal (chief law officer), then ordered her arrest. On February 10, 1669, Eva was apprehended and thrown into the ‘black hole’ dungeon at the Castle of Good Hope, which had replaced De Fort de Goede Hoop.

From then on, Eva became an outcast, shunned by the society that once celebrated her. On March 26, 1669, the fiscal banished her, without trial, to Robben Island, where she remained until her death on July 29, 1674. VOC records finally vilified her as a ‘deceitful whore and a vixen.’ Upon her demise, the VOC Commander's Journal described her

'irregular life,' stating that she finally found peace through death.

Schapera28 , in 1933, quotes Eva’s epitaph:

Hence, in order not to be accused of tolerating her adulterous and debauched life, she had at various times been relegated to Robben Island, where, though she could obtain no drink, she abandoned herself to immorality. Pretended reformation induced the Authorities many times to call her back to the Cape, but as soon as she returned, she like the dogs, always returned to her own vomit, so that finally she quenched the fire of her sensuality by death ... affording a manifest example that nature, however closely and firmly muzzled by imprinted principles, nevertheless at its own time triumphing over all precepts, again rushes back to its inborn qualities.

Eva's children, Pieternella van Meerhof and Salomon van Meerhof, were sent to Mauritius in 1677.

Eva may have passed some of her genes all the way down to us.

In our own ‘white’ family, descendants of Eva, we had a remarkably resilient aunt whose intelligence and good humour shone despite the hardships she faced. She endured abuse as a child, grappled with serious domestic violence in her marriage, and struggled with the weight of alcoholism. On unannounced visits, we occasionally encountered her in bed, in a drunken state with an equally drunken man. They were having sex while we made tea in the kitchen! Reminds me a bit of Eva!

We were led to believe in Apartheid South Africa that most Indigenes were inherently stupid, incipient drunkards and sexually promiscuous. Fortunately, such racial stereotyping and profiling are ever so slowly disappearing in South African communities, and also in our Australian communities.

Eva would be OK today! Our relationship with Eva:

Many of my ancestors were slave owners. September van Bugis was one of my fourth great-grandfather, Oupa30 Erasmus Smit's slaves. The ‘Rainbow Nation’ recognises September van Bugis as one of their heroes in the struggle for freedom.

The record of ownership can be found in the Cape Slave Muster Rolls31 . My relationship to Erasmus Smit is given in the Genie.10 Database.

September would have faced the harshest treatment as Erasmus’s slave. He would have been forced to toil on the Smit family’s farm, enduring relentless beatings. He would have had to work to the point of exhaustion and close to death on many occasions. He was eventually sold as an old and broken man, becoming a shepherd.

But September was more than a slave. He was also a spiritual leader amongst the slaves; one of the few who could read and write accidentally caught up in a dreadful murder that occurred in Cape Town in 1760.

In that year, a group of runaway enslaved men, led by Fortuin, camped on Table Mountain near the Cape Peninsula, close to Cape Town. Fortuin had fled from his

injured master, Cornelis Verwey, following a violent altercation that had occurred six months earlier. This clash had left both men with wounds, both physical and emotional. Fearing the wrath of the VOC and the looming threat of torture and execution, Fortuin sought refuge in the shadows, facing a path filled with peril and uncertainty.

As Fortuin journeyed toward freedom, his charisma and resilience attracted a diverse group of fellow fugitives, each carrying the weight of their own struggles and pain. Together, they had a deep bond rooted in their shared experiences of suffering and oppression. This connection became a protective shield for them, offering moments of solace and support against the harsh realities of their world.

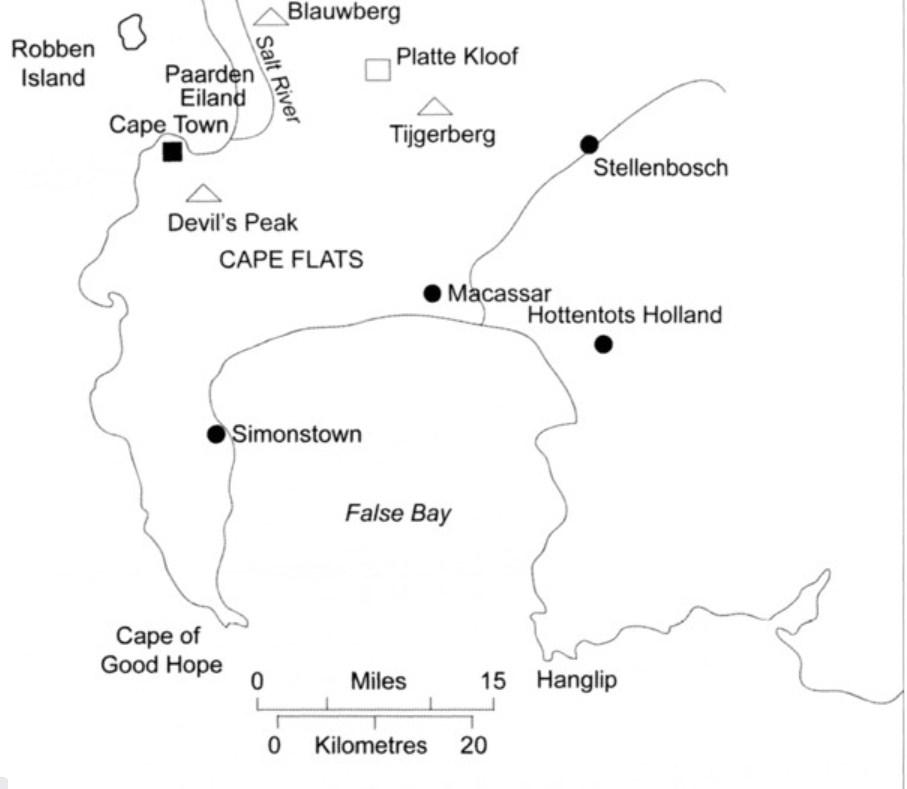

As they journeyed towards the sanctuary of Hangklip (Figure 4 below), nestled along False Bay, the ragtag band knew their path was perilous. To navigate the dangers ahead, they sought the means to defend themselves. Their gaze fell upon the affluent abode of one Michiel Smuts (Figure 13 Below). In the heart of Cape Town, Smuts, a figure of local influence and prosperity, resided amidst the trappings of VOC privilege. As a VOC bookkeeper and former commissioner, Smut's wealth and connections made him the perfect target for their desperate plan.

Nestled within the verdant embrace of Cape Town Gardens, the Smuts' residence stood as a testament to the spoils of exploitation and corruption. Within its luxurious confines, Michiel Smuts, alongside his wife Susanna de Cock and their two children, revelled in the comforts provided by

their ill-gotten gains extracted through the toil of enslaved labourers.

Fortuin and his band of renegades forged a pact with Alexander, one of Smuts' slaves. Guided by Alexander's insider knowledge, the gang plotted their daring intrusion; they were ready to change the lives of the Smuts household forever.

Before Fortuin and his gang descended on the Smuts's house, Alexander threatened the other slaves at the house with death if they were to alert Smuts or raise the alarm. A servant was tasked with letting the gang into the house after dark.

And they did.

Amidst the splendour of their decorated chamber, Mr Smuts and his wife Susanna lounged in the luxurious house. Adorned walls boasted no less than twenty-five paintings, while glistening silver and gold ornaments whispered tales of lavish indulgence all fruits of a global conspiracy woven by the VOC and its cohorts.

In an explosion of violence, the serenity of their luxury was shattered. Fortuin and his cohorts descended upon the unsuspecting couple, filled with hate and seeking revenge and weapons. Despite Smuts' desperate resistance, he stabbed a member of the gang clean through his hand; a swift blow from Fortuin sent him crashing to the ground, dazed and vulnerable. Once on the ground, Fortuin deftly slit Smuts's throat.

With ruthless efficiency, the gang silenced Susanna's cries for help, their hands staining crimson as they carried out their grim task. Even the innocent slumber of the Smuts' children offered no refuge from their brutality as the gang's blades moved swiftly to extinguish their young lives.

In the aftermath of their bloody rampage, the once serene abode bore witness to a scene of unspeakable horror, a grim tableau that reverberated through the corridors of power, striking fear into the hearts of the VOC oppressors who ruled with impunity.

Fortuin and his gang took off with three flintlock pistols, some gunpowder and shot, clothes, silver cutlery, jewellery, and food for the long road ahead.

Fleeing northward, the fugitives sought refuge amidst the shifting sands of the 'Cape Flats'. Their journey led them to Plattekloof (Figure 14 Below, nestled at the western edge of the Tygerberg, where they hoped to find medical assistance for the injured member of their party. They knew that Fortuin's brother, September, a well-known healer, resided there. They knew that he would help them and possibly hide them. He was a slave freed by Erasmus Smit.

Arriving under cover of darkness, their hopes were somewhat dashed by a sobering reality. September, worn down by the relentless toil of enslavement and the cruel lash of oppression, languished in poor health. Like so many of his brethren, his body bore the scars of servitude, his spirit tested by the unyielding cruelty of his masters.

Yet, despite his suffering, September welcomed his brother and their comrades with open arms, his voice a beacon of warmth amidst the shadows of despair. In their Buginese tongue, he greeted his kin, his words carrying the weight of shared struggle and resilience.

With practised hands and a healer's touch, September tended to the wounded hand. Amidst the darkness of their plight, his gentle ministrations offered a glimmer of hope, a reminder that even in the darkest of times, the light of compassion still shines bright.

September's reputation had preceded him in the region as a skilled healer and sage counsellor, revered by both slaves and free alike. His wisdom and compassion transcended the bounds of his enslavement, earning him a place of honour among those who sought solace and guidance in those terrible times. In an era where education was a rare privilege, September's ability to read and write set him apart, granting him elevated status among his kinsfolk.

With the wound tended and spirits uplifted, Fortuin and his companions embarked once more on their quest for freedom, courageous again and with newfound determination. Their journey towards Hangklip promised freedom.

Yet, fate's capricious hand intervened once more as they encountered slave woodcutters in the waning light of dusk. Hunger gnawing at their bellies, the gang's demands for sustenance were met with reluctant compliance from the weary woodcutters. Amidst shared rations and the warming

glow of brandy, tales of hardship and defiance flowed freely, binding them together.

The woodcutters extended a wary invitation for Fortuin and his band to spend the night. Yet, as the potent brew of brandy lulled the weary travellers into a stupor, treachery stirred in the shadows.

Under the cloak of darkness, one of the woodcutters slunk away, hastening to the nearby camp of the VOC commandos. With a heart filled with betrayal and thoughts of a good reward, he divulged the whereabouts of the sleeping fugitives, weaving a tale of deceit that would seal their fate.

Assured of the reward awaiting him, the woodcutter vanished into the night, his conscience drowned by the promise of a brighter future. As the first light of dawn broke upon the horizon, the thunderous gallop of hooves heralded the arrival of the VOC commando unit, and they unleashed their wrath upon the unsuspecting camp.

Caught unawares and in the grip of slumber, Fortuin and his comrades stood no chance against the merciless onslaught of their assailants. Bound and battered, they were dragged into the heart of the encampment, their cries drowned by the crack of sjamboks and the stench of betrayal that hung heavy in the air.

With fervour, the soldiers unleashed a barrage of sjambok32 lashes upon the hapless fugitives, their blows fuelled by a thirst for confession. They singled out the weakest among

them, branding his flesh until his cries echoed in surrender. Under the spectre of unbearable torture, he confessed to the murder of the Smuts family, his words a damning chorus that sealed their fate.

With their guilt laid bare, the soldiers dispensed swift retribution, executing the condemned with chilling efficiency. One by one, they fell beneath the cold gaze of their executioners, payback for the blood spilled in the halls of the Smuts' residence. Yet, amid the carnage, Fortuin and a lone comrade were spared the final embrace of death, reserved for further interrogation within the grim confines of the Cape Town Castle, a place of no hope.

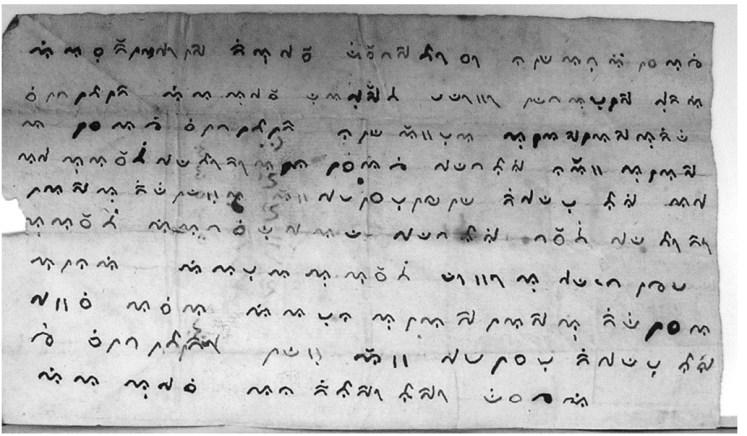

Meanwhile, a detachment of the commando unit set forth to apprehend September at Plattekloof farm, driven by suspicions of his alleged role in orchestrating a rebellion that had been simmering for some time. Unbeknownst to the fugitives, September's shadow loomed large in the eyes of the VOC, his very existence a threat to their fragile order. Upon his arrest, their fears were seemingly confirmed as they uncovered damning evidence in the form of the ‘Upas Stellenbosch Letter’ (Figure 15 below). This document would seal September's fate.

The supposed damning contents of the letter laid bare the atrocities perpetrated by the VOC towards the slaves. The letter also pleads with September to lead the Bugis people out of their suffering. Upas meant a spiritual leader; the VOC interpreted this as the leader of an impending rebellion! With this pretext in hand, they swiftly arrested him

on charges of murder and treason, whisking him away to the dreaded confines of the ‘Castle’ for interrogation.

Despite September's protestations of innocence, his pleas fell on deaf ears. The Council of Justice, swayed by the ‘damning’ evidence of the letter, condemned both Fortuin and September to a gruesome fate. Bound to the torture rack, they endured unspeakable agony as red-hot pincers seared their flesh, each torturous moment one step closer to death.

In a merciful twist of fate, Fortuin was granted the solace of a swift death blow, while September faced a far crueller fate. Bound to the torture rack, his body wracked with pain; he endured the agonising ordeal of having his bones systematically broken, from his head to his feet. Yet, amidst the torment, September remained resolute, his silent defiance a testament to his unyielding spirit.

Historical records show that September did not utter a single cry of pain. His dying words were, 'There is no god but Allah, and Muhammad is His Messenger.'

These final words, a solemn declaration of faith, have echoed through the annals of history, a poignant reminder of his unwavering devotion. Many, many years later, in the wake of his martyrdom, the Cape Town City Council erected a shrine in his honour, commemorating September van Bugis a martyr and spiritual leader. This is supported by the testimony of scholars like Shaykh Seraj Hendricks, meaning September's legacy endures as a beacon of hope and

resilience in the Hall of Heroes within the heart of the modern ‘Rainbow Nation’ .

Figure 14: September's residence.

Figure 15: The Stellenbosch letter34 .

The Cape Town City Council has erected a shrine (Figure 16 below) next to a shooting range on Philip Kgosana Drive

(De Waal Drive) in Cape Town to remember September the martyr – the very same September van Bugis.

The late historian36 Achmat Davids, in his unpublished manuscript Slaves, Sheikhs, Sultans, and Saints, supports Shaykh Hendricks' argument that the man known as 'September van Bugis' is the mysterious saint buried on Devil's Peak, known to his followers as Shaykh Abdal Qadir' (Figure 17 below).

So, Erasmus's enslaved person, September, is now recognised as a martyr and spiritual leader in the 'Hall of Heroes' by the modern ‘Rainbow Nation’ .

The Huguenots were quite the characters in our Afrikaner family histories! These French Protestants of the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition were welcomed with open arms at the VOC refreshment station. Not only did they bring some skills and know-how, but they also brought with them women, in very short supply at that time.

As the years passed, their influence blossomed. By the twentieth century, South Africa was shaped by an array of prominent business, political, and social leaders who bore French surnames names that were often perceived as more prestigious than their Dutch, German, or English counterparts! It wasn't until later in my life that I stumbled upon a fascinating revelation: our family has a deep-rooted connection to the very first Huguenots who arrived at the VOC refreshment station.

The story of the Huguenots is one of resilience and struggle amid religious turmoil. As they sought to practice their Protestant faith in France and Wallonia (southern Belgium), their growing influence sparked fierce opposition from the Catholic majority, igniting the intense French Wars of Religion from 1562 to 1598. These years were marked by battles, betrayals, and a desperate fight for survival.

The conflict finally subsided with the signing of the Edict of Nantes, a remarkable agreement that granted the Huguenots certain freedoms and rights. It was a moment of

hope, allowing them to practice their beliefs openly. However, this hope was short-lived. In 1685, King Louis XIV often referred to as the Sun King cast a dark shadow over the Huguenots by revoking the edict. He boldly proclaimed, “One faith, one law, and one king,” ushering in a period of dreadful persecution that drove many Huguenots to flee their homeland in search of safety and freedom.

Their journey was marked by courage, as they sought refuge in foreign lands, carrying with them their faith and a determination to survive against all odds. The legacy of the Huguenots is a testament to the enduring human spirit in the face of adversity, reminding us of the struggles for religious freedom that resonate through history.

Many Huguenots converted to Catholicism or fled. Those fleeing had a torrid time, indeed.

My 7th great-grandfather, Jean Prieur Du Plessis, was born in Poitiers, Poitou-Charentes, France, in 1638 and arrived at the Cape from Europe in 1685.

He was a renowned and skilled surgeon.

Jean Prieur had staunch Calvinist beliefs. He refused to convert to Catholicism. He found himself in a dire predicament: abandon his faith and freedom or endure a gruesome fate, possibly death at the stake. He witnessed his home and the local church engulfed in flames while some of his neighbours suffered at the stake, their screams silenced forever by the flames, but never to be forgotten.

But Jean Prieur was resilient and independent and sought to seek refuge in a land where he could worship freely, in a society where he would be accepted and treated justly. Daily, his friends and neighbours fled to the borders of France and the seaports, escaping the persecution of Catholics. Huguenots fled clandestinely, disguising themselves as beggars, travelling merchants, gypsies, soldiers, and shepherds, while women dressed as men, dyeing their faces to avoid detection.

Jean Prieur remained hidden in Poitiers for three years amidst heightened surveillance and danger. Soldiers guarded every exit while informants eagerly turned in fugitives for rewards. Witnessing the capture of friends and family, he lived in constant fear, venturing out only under cover of darkness to evade hostility and persecution.

During the mass exodus of Huguenots from Europe, over 400,000 sought refuge in Switzerland, Germany, England, America, and the Cape of Good Hope. Eventually, Jean Prieur secured passage on a ship to St. Thomas in what is now the US Virgin Islands, captained by a sympathiser.

In St. Thomas, Jean Prieur married another Huguenot, my seventh great-grandmother, Marie (Madeleine) Mentanteau, in June 1687. They then sailed to Amsterdam and joined the Waalse (Walloon) Church, finding sanctuary in a Calvinist haven.

On January 8, 1688, Jean Prieur gladly swore allegiance to the VOC in Middelburg, Zeeland, eager to start anew as a Vryburgher38 at the Cape. He and Marie set sail on the Oosterland for the Cape, welcomed by the VOC in Table Bay. Medical professionals were scarce in Stellenbosch and Drakenstein, making Jean Prieur's skills highly sought after.

Many prominent families boast of having a link to Jean Prieur10 .

Step back in time to the bustling streets of Ghent in the late 17th century, where my 9th great-grandfather, Jacques, was making waves as a successful merchant and entrepreneur. In 1688, driven by ambition and a spirit of adventure, Jacques set sail for the distant shores of the Cape. There, in the magnificent Drakenstein area, he embarked on an exciting new venture establishing a vineyard that would become legendary.

This vineyard, known as De Savoye Farm, would grow to be a cornerstone of the region's wine heritage and is now celebrated as Vrede and Lust Wine Farms in the picturesque Franschhoek valley. Jacques's legacy continues to flourish, as the vines he planted years ago still yield exquisite wines enjoyed by many.

Three Nortier brothers, Daniel, Jacob, and Jean, came out on the same ship as Jean Prieur in 1688 on the ship the Oosterland. Daniel was Dedrie's seventh great-grandfather! On the day they landed, Jacques was out on the jetty looking for farm workers. There, on the jetty, he offered both Daniel and Jacob a job. They were skilled farmers and had also worked as carpenters rare commodities at the Cape.

Despite his success, Jacques was an abrasive man. He was deeply religious, but often fought with anyone over the most trivial matters, except on Sundays, when he became quiet and contemplative, as was expected of a good Christian. In Flanders, he welcomed Huguenot pastors into his home, where they held home services, but going out to church became too hazardous. During those services, the records

say, he sang psalms so loudly during the day that neighbours complained! Rumours had it that he even picked a fight with the local Catholic vigilantes (particularly Jesuits) who bore a grudge against him, even threatening his life.

His wife, Christine du Pont, my ninth great-grandmother, tragically passed away in Belgium during childbirth, a fate not uncommon in those times. Jacques remarried and then departed for the Cape, bringing all his children with him. He came as a refugee and with business plans!

But Jacques did not leave his touchy ways behind. In Franschhoek, he clashed with various figures, including the governor, Willem Adriaan van der Stel. It must have been a serious clash, because the next thing, he ended up in the dungeon in the Cape Town Castle to calm him down. Immediately, upon his release, he found himself embroiled in a bitter feud with Reverend Pierre Simmond, a conflict that is still talked about to this day.

It all began with a rumour circulating in Stellenbosch and Drakenstein, claiming that Jacques, the new businessman at the Cape, was a bankrupt, fleeing his creditors in Belgium and seeking refuge from them at the Cape. This hurt him and tarnished his image deeply, leaving him in a combative mood, spoiling for a fight with anyone who just as much raised an eyebrow.