2021

2022© WaveArt Collective, WaveArt Fellowship, belong to WaveArtCollective, All Rights Reserved. For Scarbrough, In Scarbrough

The existance of this ORGANIZATION and it’s community initiatives are graciously made possible by a range of PARTNERS, FUNDERS, and SUPPORTERS

Leadership

Partners

WaveArtCollective is a group of ARTISTS, EDUCATORS, ACADEMICS, and MOBILIZERS creating art and educational programming to foster Scarborough’s creative scene.

Over the past decade, marginalized immigrantbased areas of Toronto like Scarborough have seen a renaissance in their public perception and interest, bringing a new light to the diverse culture, food, and arts of these communities. In many ways, it has felt like a sudden wave of attention towards uplifting these ARTISTIC and CULTURAL voices, bringing opportunities that were never available just two decades ago when we were growing up. Thus, WaveArtCollective was conceived to serve as a conduit to drive arts opportunity and infrastructure in Scarborough

Sampreeth Rao CO-FOUNDER Amandeep Sandhu CO-FOUNDER Kevin Ramroop CO-FOUNDER Masooma Ali CURRICULUM, RESEARCH LEAD Kahlil Hernandez CURRICULUM LEAD Raj Mann DIGITAL MEDIA LEAD Natasha Ramoutar CURRICULUM LEAD Deena Nina STRATEGIC GROWTH & DEVELOPMENT LEAD

City of Toronto Scarborough Arts University of Toronto (SCARBOROUGH)

4

The WaveArt Fellowship is an ARTIST residency for emerging creatives between the ages of 17-24 located within the city of Scarborough.

In 2016, The WaveArtCollective established the WaveArt Fellowship, a digital media and arts entrepreneurship program for Scarborough YOUTH. The fellowship has not only been a conduit for each artists’ individual works, but it has also expanded to take on the vital role of curating and disseminating works that are made by the Scarborough community. It has operated in part with the funding and support from the Toronto Arts Council, ArtReach, and the City of Toronto IDENTIFY ‘N IMPACT Grant.

APPLY1 waveartcollective.ca/fellowship

1For more details on the application process and a more detailed overview use the supplied weblink.

5

It goes without saying that the 2021 iteration of the WaveArt Fellowship was a wild one. What’s usually an in-person mentorship for emerging artists from Toronto’s margins became something entirely new during the COVID pandemic. During January to May 2021’s unprecedented lockdown, eight fellows – four photographers and four writers – created a series of artistic works speaking to the theme of The New Normal . This book is a culmination of those works; a document of the spirit of the times and the relentless commitment of emerging artists inequitably well-versed in working on the margins.

Sampreeth Rao

6

Co-Founder, WaveArtCollective

FROM THE CO-FOUNDERS PREFACE

Permission to speak a bit, erm how should mans put it, candidly? Because if it’s one thing we can all agree on, this past two years or whatever bruk off all we back and twist we up a new one that nary could have prepared for. Just as much as we’ve been separated, confined physically, our means of communicating have suffered the same fallow and desolate fortunes - wonky zoom calls that are either roadblocked by wi-fi struggles or obstructed by talking over each other for no reason other than not having the crucial physical cues. Jokes are lost, expressions aren’t expressed. Turning to the written word is no less dreadful; if mans write at all nowadays it’s mainly for these procedural, 500-word-count-limited blurbs like a grant application or this foreword, where I have to compress and compact all the things we have to say as artists plus all the things we don’t have in resources and support to be able to say these things as artists into a simple, professional little paragraph.

But that’s why we started this Collective, and figured out our way into continuing this Fellowship — so that we could preserve the unfiltered, baroque expression that energizes the miraculous group of eight artists that we found almost a year ago. And while the fellowship was mitigated to these tragically imperfect modes of communication – the glitchery video calls and formal(ish) applications and interviews – the work they were able to produce was…

fam I wish you could know how long I had to pause to think about what the right word would be so I don’t have to be too wordy. Like at least four minutes. So just take that in, it’s just beyond words zeen? I just got lost thinking on how multilayered each and every one of the works is — reflecting the times, the spaces, the cultures that we’re all rooted in. And when you have time and space to dig into the roots of these cultures in a meaningful way, the

work also stands for something beyond this global predicament — transcending the culturally and socially stringent boundary divides that look more like beautifully weaved webs in Scarborough. While the fellows were crafting their works, engaging weekly in conversations across literature, art, philosophy, personal affectations, how they all empower and stand vulnerable in their pieces, we found our way together towards cultivating a fellowship in the truest sense of the word: a mutually enriching learning exchange between the Collective and Fellowship participants involved, which is now shared in a mutual exchange with you as you peep through this, our, book.

Over the time of the Fellowship I also started writing a poem, perhaps being repercussively inspired by everyone digging into their roots during this time so boldly and vividly. I started thinking about callaloo a lot, especially after finding a book named “Callaloo Nation: Metaphors of Race and Religious Identity among South Asians in Trinidad”. Callaloo is a stew with roots in West Africa that adapted to the culture and agriculture that each Caribbean island distinctly developed. You can toss in some crab, some coconut milk, and whatever spiced root leaves may be available on your particular island - whether they are of African, Asian, European, North or South American origin, like bhaji (spinach), dasheen (taro), or amaranthserve it just so or on rice, and you have my dad’s favourite meal. Instead of yammering any longer I’ll just share the poem here because I find, just as I’m sure you will too, that the work in this book speaks a much more complicated, intricate truth of the uncertain waves we all traversed together than any old concise cookie cutter set of five hundred words I could have laboured over just to proffer a more traditional foreword.

Co-Founder, WaveArtCollective

Kevin Ramroop

7

FROM THE CO-FOUNDERS FOREWORD

Phantom limbs loom and lime weave wind and wave their way through liminal limbos

Subliminal passages

In the middle of some great divide | (w)hol(e)d

our sum parts to set red seas/suns, with ease they seize sons et filles sans sens, without sinking ships filled with weighted sins Wading Waiting Wailing above the middle sink basin lay Bare red crabs buried in coconut sun shell

Cram up coddled one over one clenching middlefinger gundy with a kind of blued-clawed fluency and Cut-eyes like cutlass, flout and clout those invisibly clean hands with rass Cloud-padded heads bottled in bumba clotted creamy coconut milk moons that bubbled bloody curdled screams to low

boiling point steams and rose up from the bottom of the pan | pon gaea | thalassa | dora | demia | acea

The last of a moment we pondered a sea of one between us | before kala pani called upon we behind closed doors that had not yet never been returned

Before the murky muddering waters left fathers motherless murmuring a fodder muttered in murderous muddarass tongues drowned out amidst the walls of spectral sound

Before we ripened darkest at the heart, like we heard grapes from the middle of the vine concurred in concord to make for the finest of middling-aged wines, songs that spilled of sanguinary saccharine languor and sang when Ares' horns rang bacchanal in consortium through the middle of some divine

8

------------ --------------------- -------------------------- --------------------- ---------------------------------------- -------------------- --------------------- -------------------------------- -------------------------------------------------------------- -------------------------- --------------------- ----------------------------------------- --------------------- -------------------- -------------------------------------------- --------------------- ----------------

--- ------------------------------ ------------------------------------------ --------- -------------------------- --- --------------------------------------------------- --------------FROM THE CO-FOUNDERS

Conquerors' concert | blood stained clods of common ground drawing lines in sand Land body and so(u)(i)l |

(ph)entombed, limned and lined in loam be-reaved rinds reaped and sown by wraithing ravenous royal s(w)in(e)s

Like truffle pigs rooting and roiling about in blind odyssey, high on the hog hot on the trail of ac(i)d(i)c currents

left wafting up in the air, noses incensed by spiced roots of amaranth dasheen yam bhaji callaloo where loveLies-bleeding—

By Kevin Ramroop

9 ------------ --------------------- ----------------------------------------- --------------------- -------------------- --- --------------------------------------------------- ---------------

--- --------------------------------------------------------------------------- -------------------- --------------------- ----------------------------------------- --------------------- -------------------- -------------------------------------------------------------- ----------------------------------------------------- --------- ------------------------------ ------------------------ ------------------------------------------------------------------ -------------------- --------------------- ------------------------------------------------------ ------------------------- ------------------------------------- ----------------------------------------------------- --------- ------------------------------ ------------------------------------------ --------- ----------- -------------------------------------

----------- ------------ --------------------------------------------- --------------------- ----------------------------------------- --------------------- -------------------- -------------------------------------------------------------- ----------------------------------------------------- --------- ------------------------------ -------------------------------- -------------------- --------------------- ----------------------------------------- --------------------- -------------------- -------------------------------------------------------------- ----------------------------------------------------- ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ----------------------------------------------- ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -------------------------------------------------------FROM THE CO-FOUNDERS

CONTENT Theme Photography Fellowship Mitul Shah Noor Gatih Kyle Mopas Alicia Reid Writing Fellowship Anjali Chauhan Luxshie Vimaleswaran Mahdi Chowdhury Tina Guo

PAGE 12 14 16 28 40 52 64 66 76 84 108

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 12

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 13

Kahlil Hernandez FELLOWSHIP MENTOR

Kahlil’s interest in photography began in his early teens when he convinced his mother to buy him a digital camera for his birthday. Humble but lowkey famous, Kali co-leads the PHOTOGRAPHY component of the WaveArt Fellowship, developing the curriculum, leading workshops, and serving as a mentor for the next generation of Scarborough photographers. Khalil is a graduate of the Remix Project, and the DIGITAL PHOTOGRAPHY Program at Durham College

Masooma Ali FELLOWSHIP MENTOR

With her multidisciplinary experience as an academic and creative, Masooma has established her work by centering around PHOTO and FILM. Honing her craft for over a decade, she has previously created work for the Senate of Canada, City of Toronto, publications, artists and several fashion brands. Masooma holds a Master’s of Planning from Ryerson University’s SCHOOL OF URBAN AND REGIONAL PLANNING

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 14

PHOTOGRAPHY FELLOWSHIP OVERVIEW

Mitul Shah

Null Spaces

BIOGRAPHY Mitul Shah is a cityscape & architecture PHOTOGRAPHER from Toronto, Canada, with a focus is on defining the memories of the everchanging metropolitan CITIES. He’s had the pleasure of working with brands such as Shopify, Samsung, Uber, & more. Most notably, his photos are included as default WALLPAPERS on every Google phone.

STATEMENT

For many, the pandemic changed our attitudes and relationships with the places we once frequented. Null Spaces is a documentation of the locations which were once full of life and energy, but are now isolated. The places which formerly brought joy and excitement are unlikely to ever be the same.

Null Spaces uses aerial photography to capture the scale of emptiness through the contrast of large spaces and minimal human subjects. Null Spaces also hides hints of localization to be more relatable to any suburbia.

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 17 PHOTOGRAPHY FELLOWSHIP FELLOW SPOTLIGHT

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 18

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 19 MITUL SHAH NULL SPACES

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 20 MITUL SHAH NULL SPACES

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 21

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 22

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 23

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 24

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 25

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 26 MITUL SHAH NULL SPACES

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 27

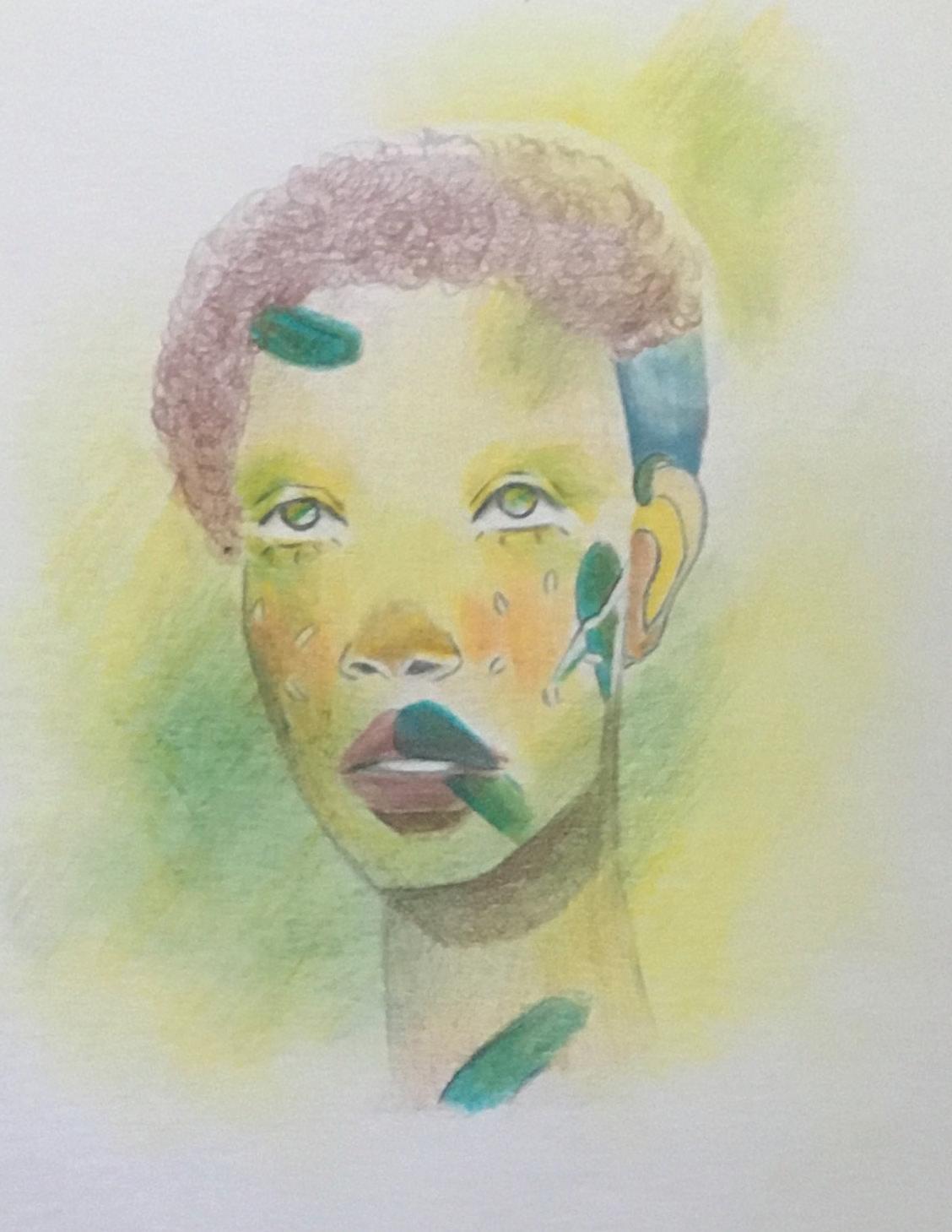

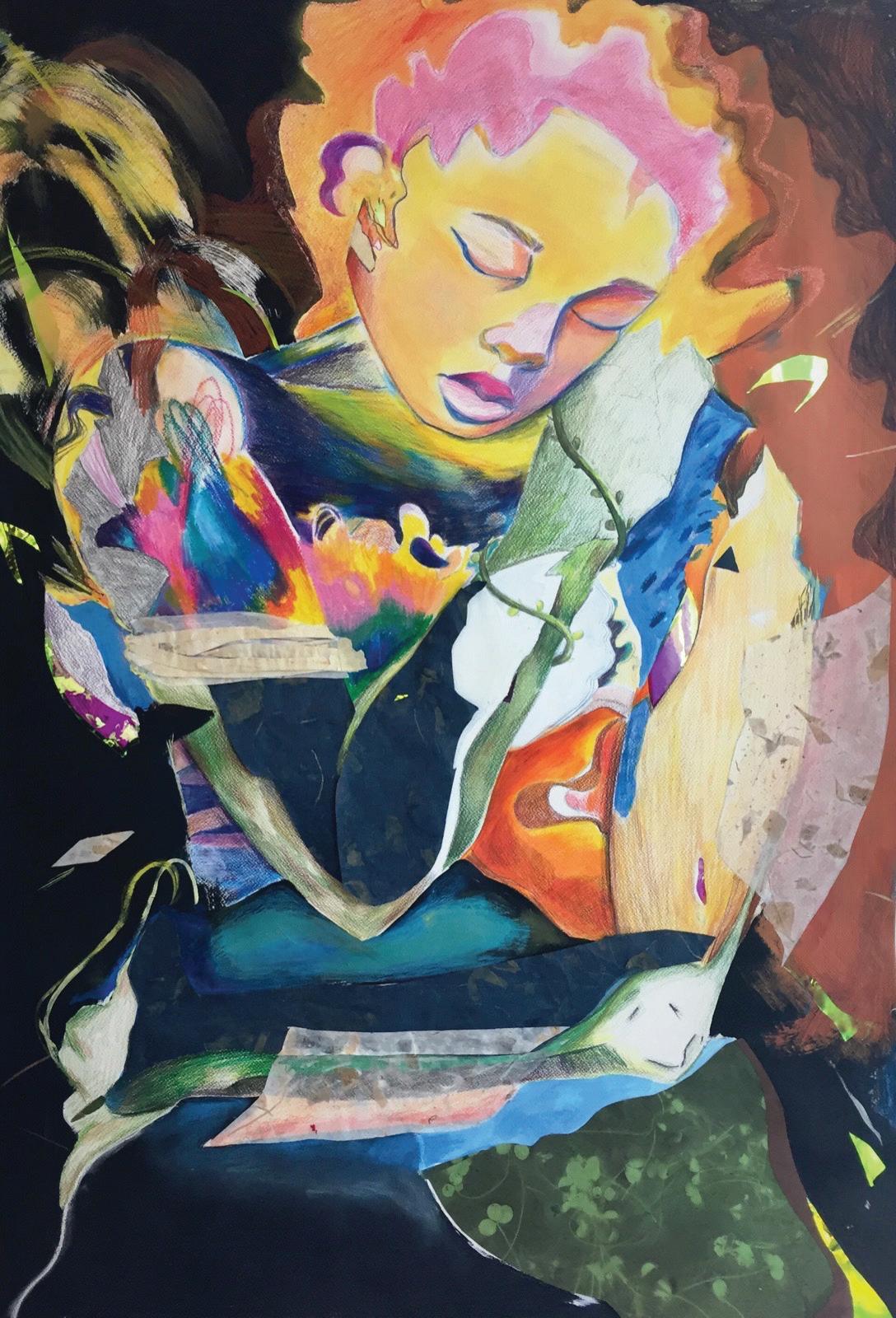

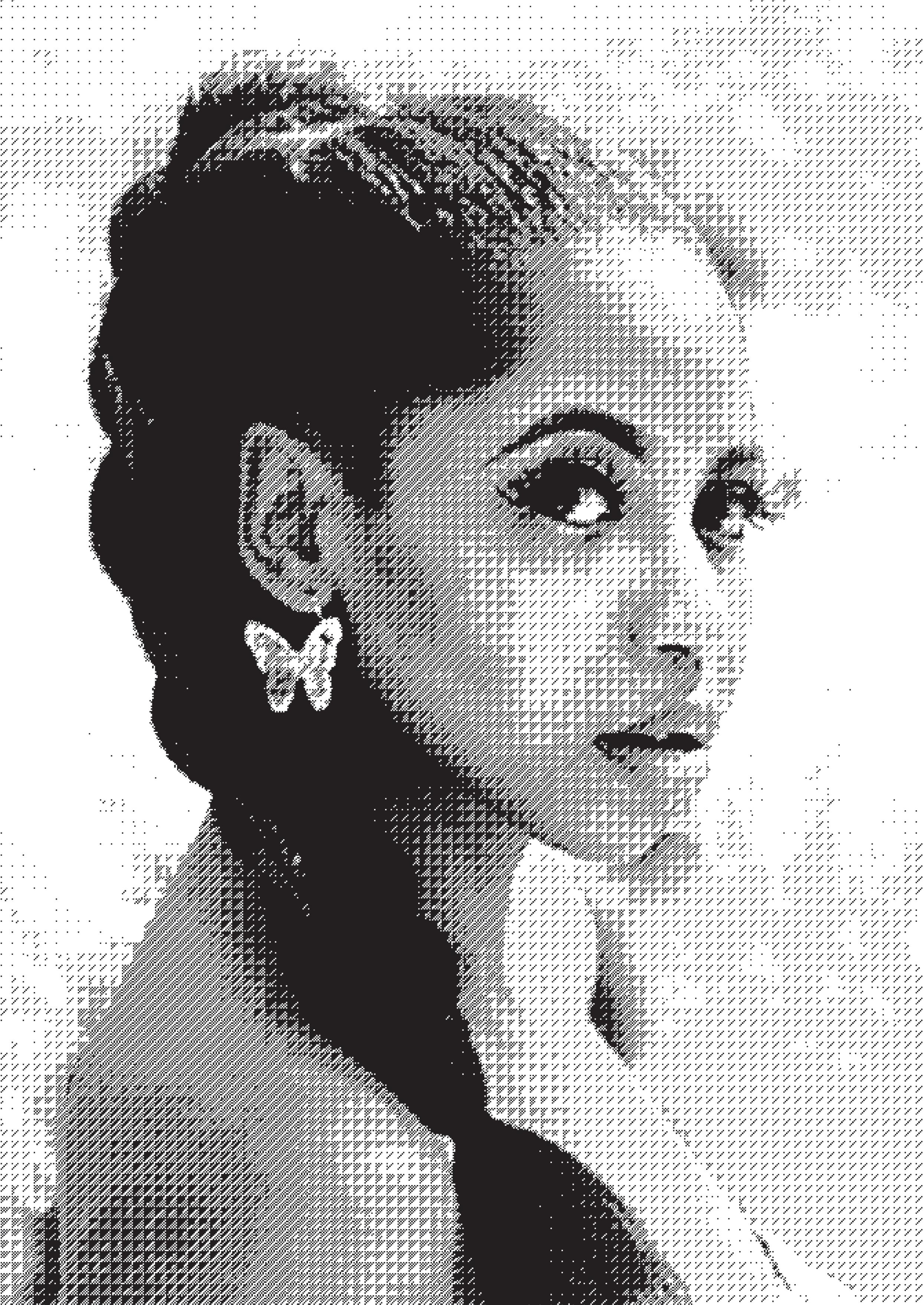

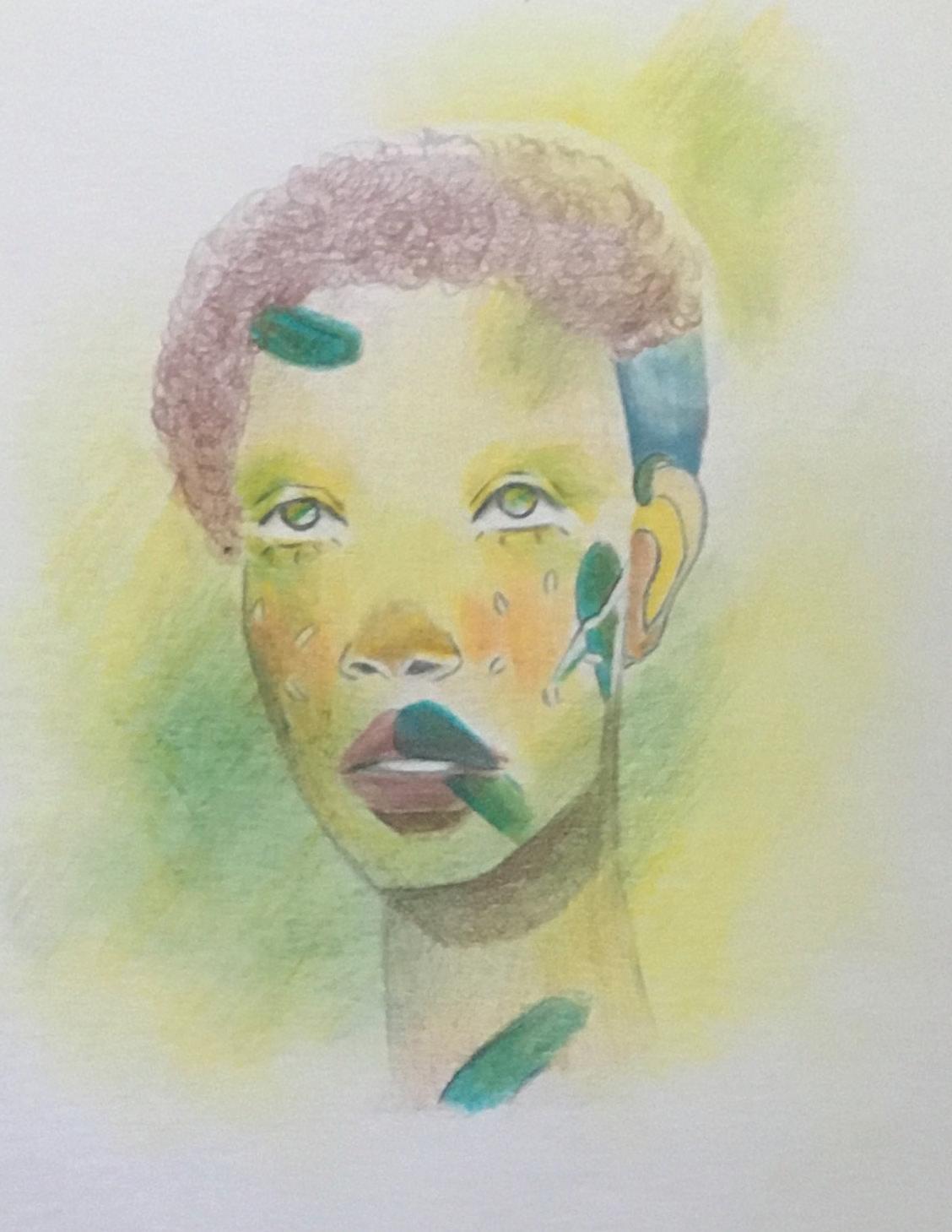

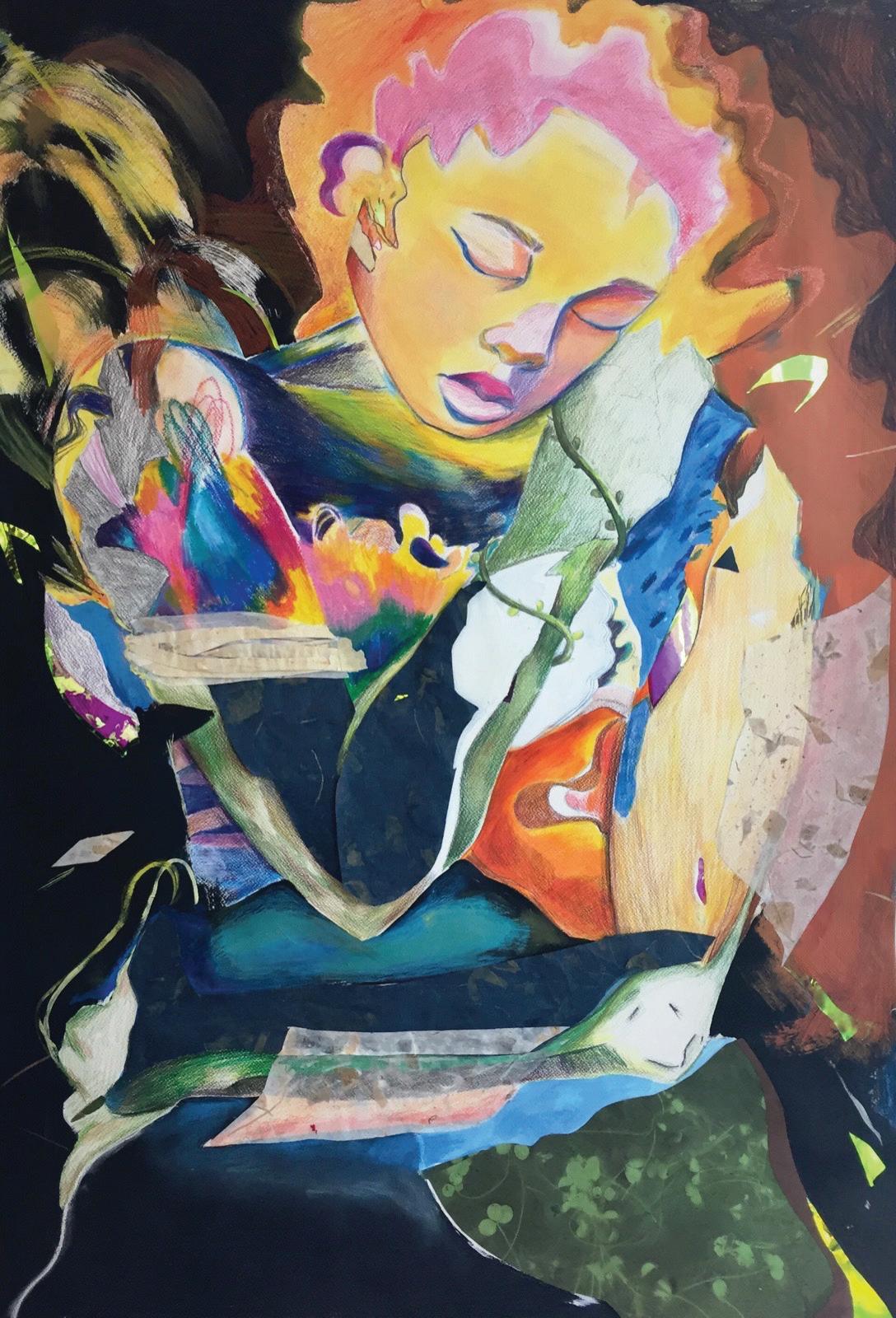

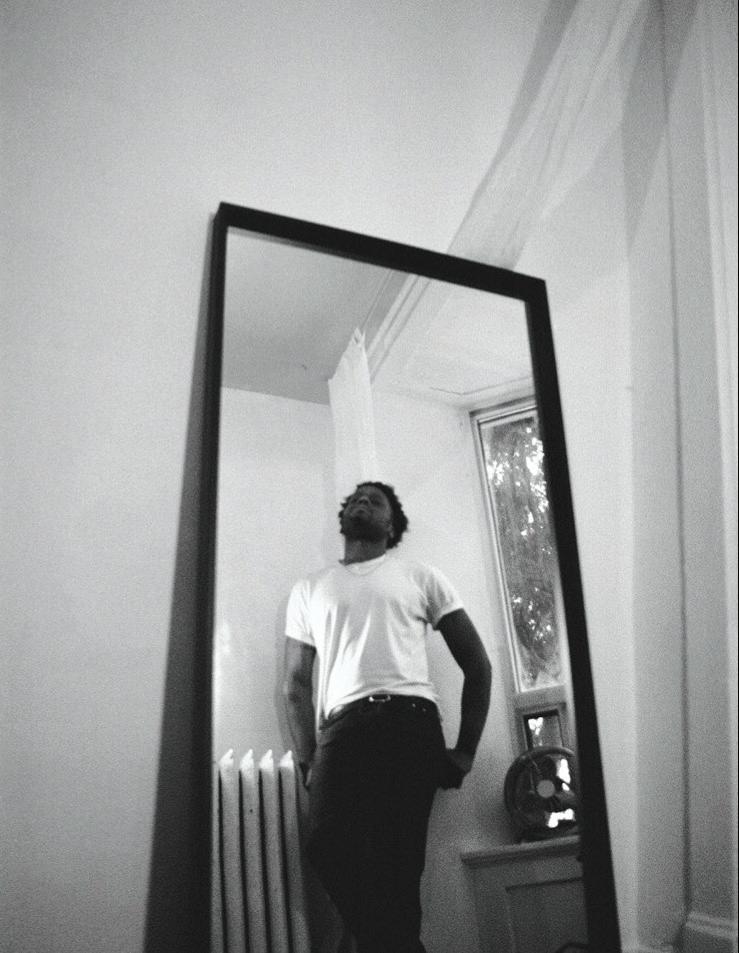

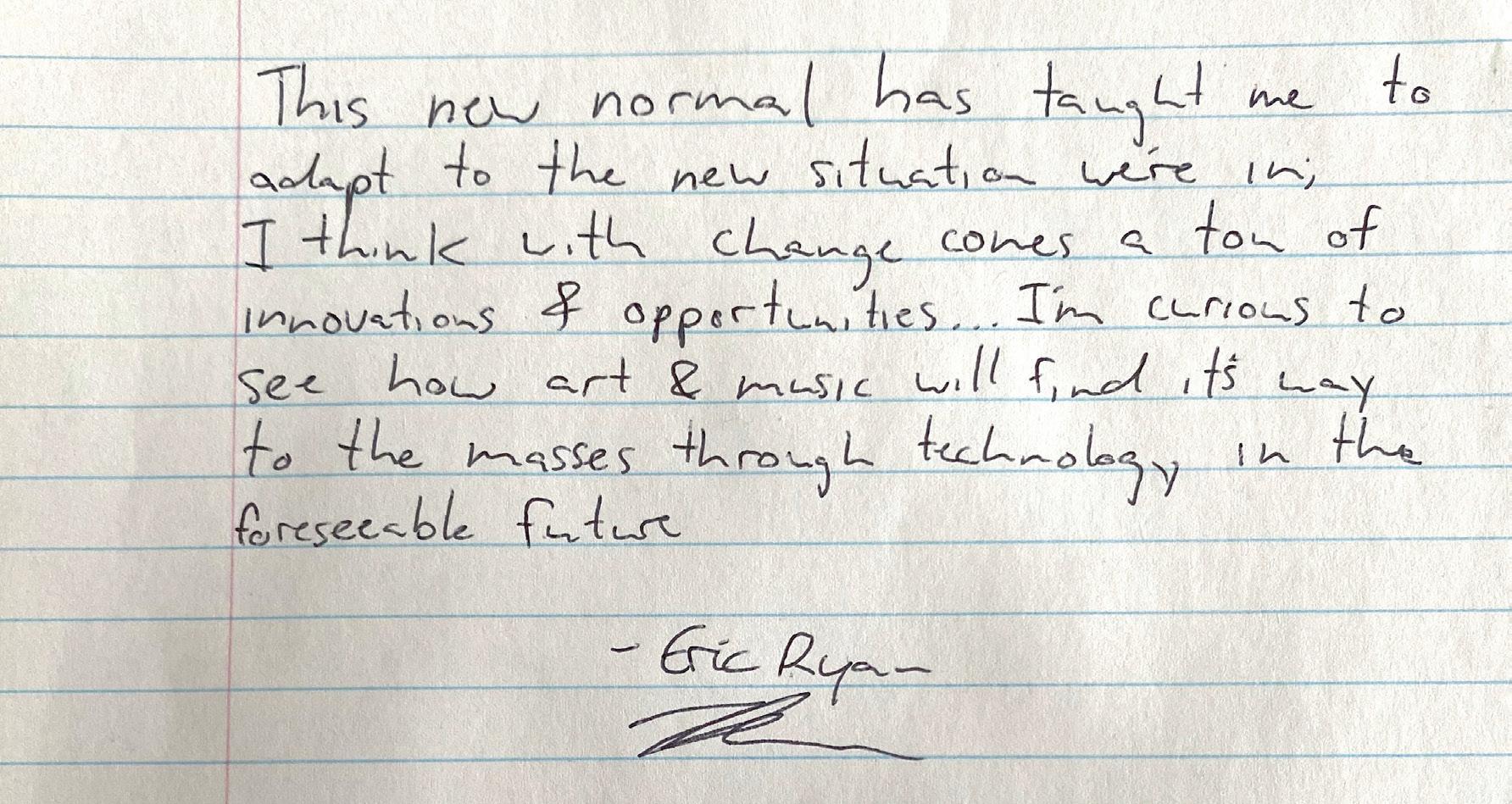

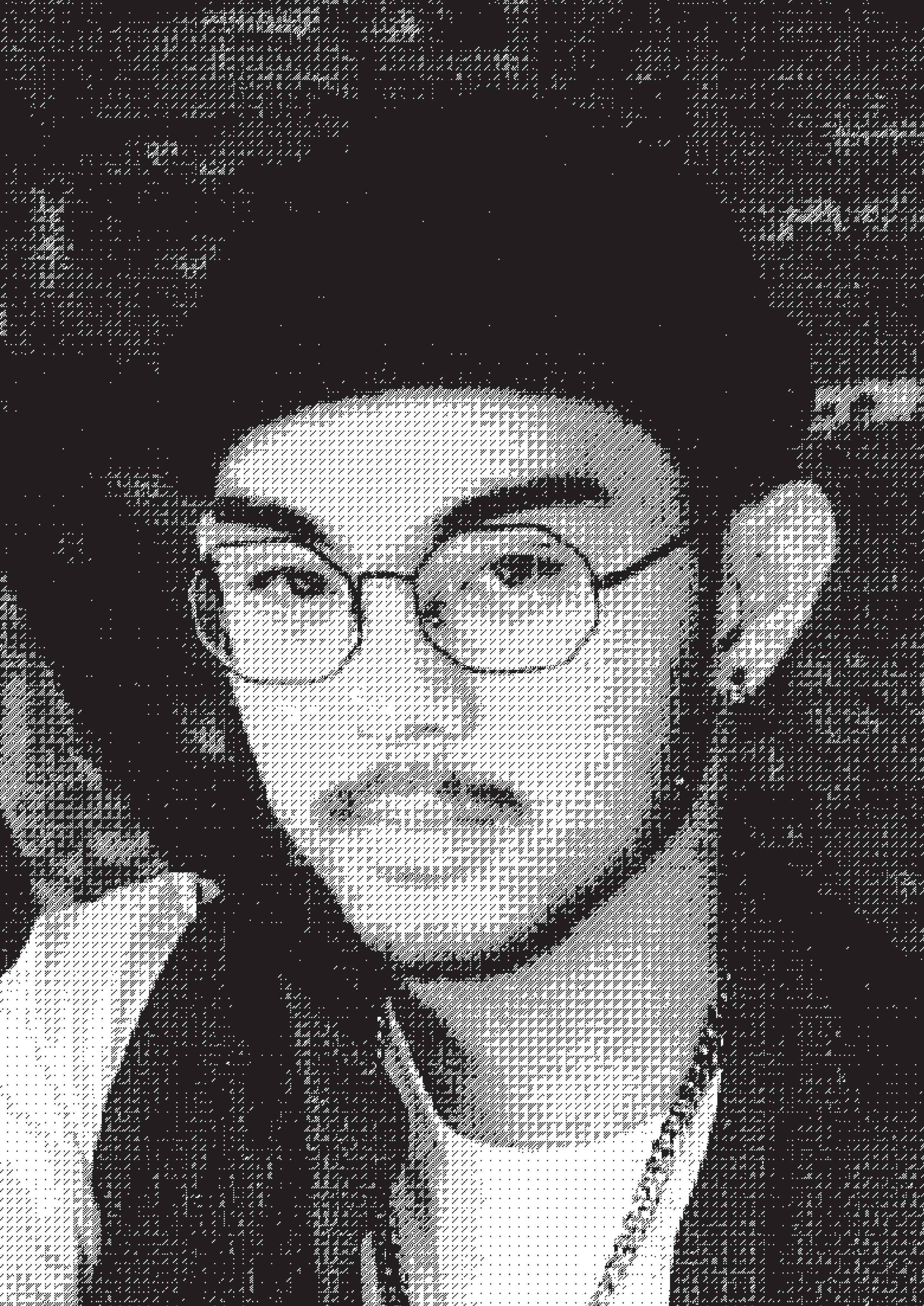

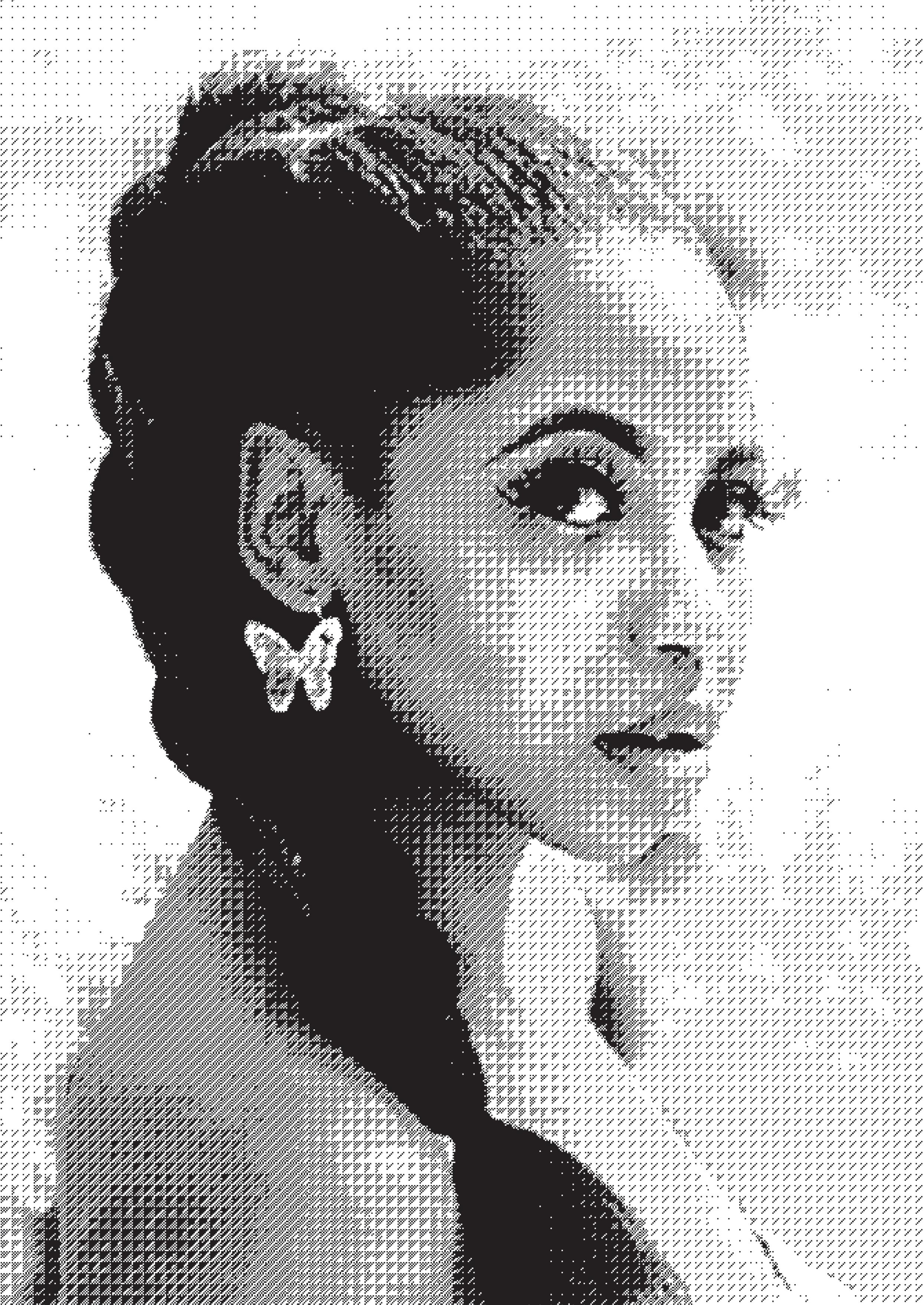

Noor Gatih

Adaptations

BIOGRAPHY Noor Gatih is a Toronto freelance PHOTOGRAPHER and FILMMAKER . Her work focuses on exploring diaspora, duality and human nature. Her experience in the industry ranges from working on album covers to brand shoots, to production design on film sets. Her photographs have been published in Luna Collective and literary mag, Long Con. Through this fellowship, Noor hopes to achieve a body of work that celebrates different artists throughout Toronto and how they’ve managed to overcome COVID-19 restrictions. In the future, she hopes to create more community driven work.

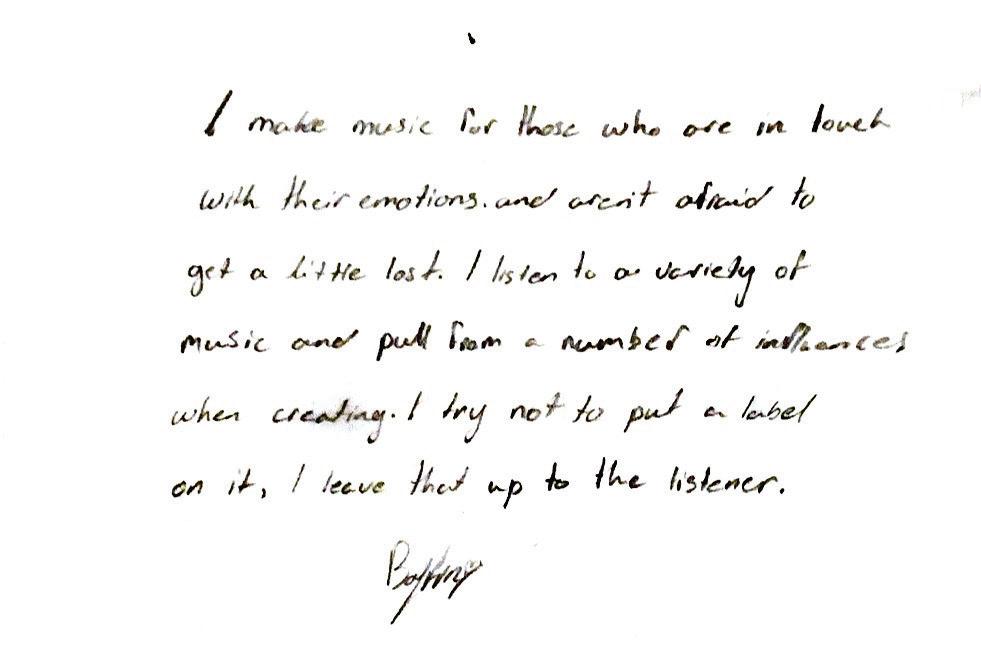

STATEMENT Since March of 2020 the city has undergone a series of closures that has limited artists from accessing resources such as studio space or gallery shows. As we transition to life in isolation many artists around the GTA have had to find creative ways to still be able to work on their art.

Adaptations is a photo-series that explores how creatives are navigating this period of ‘new normal’ and how this pandemic has shifted their creative practice.

Due to the lockdown earlier this year, I also had to shift the way that I conduct my photoshoots by doing virtual shoots via ZOOM or CLOS. This experience led me to the idea of creating a collage from each interview.

Thank you to the Wave team and my mentors, Masooma and Kahlil for helping me bring this project to life and wonderful artists.

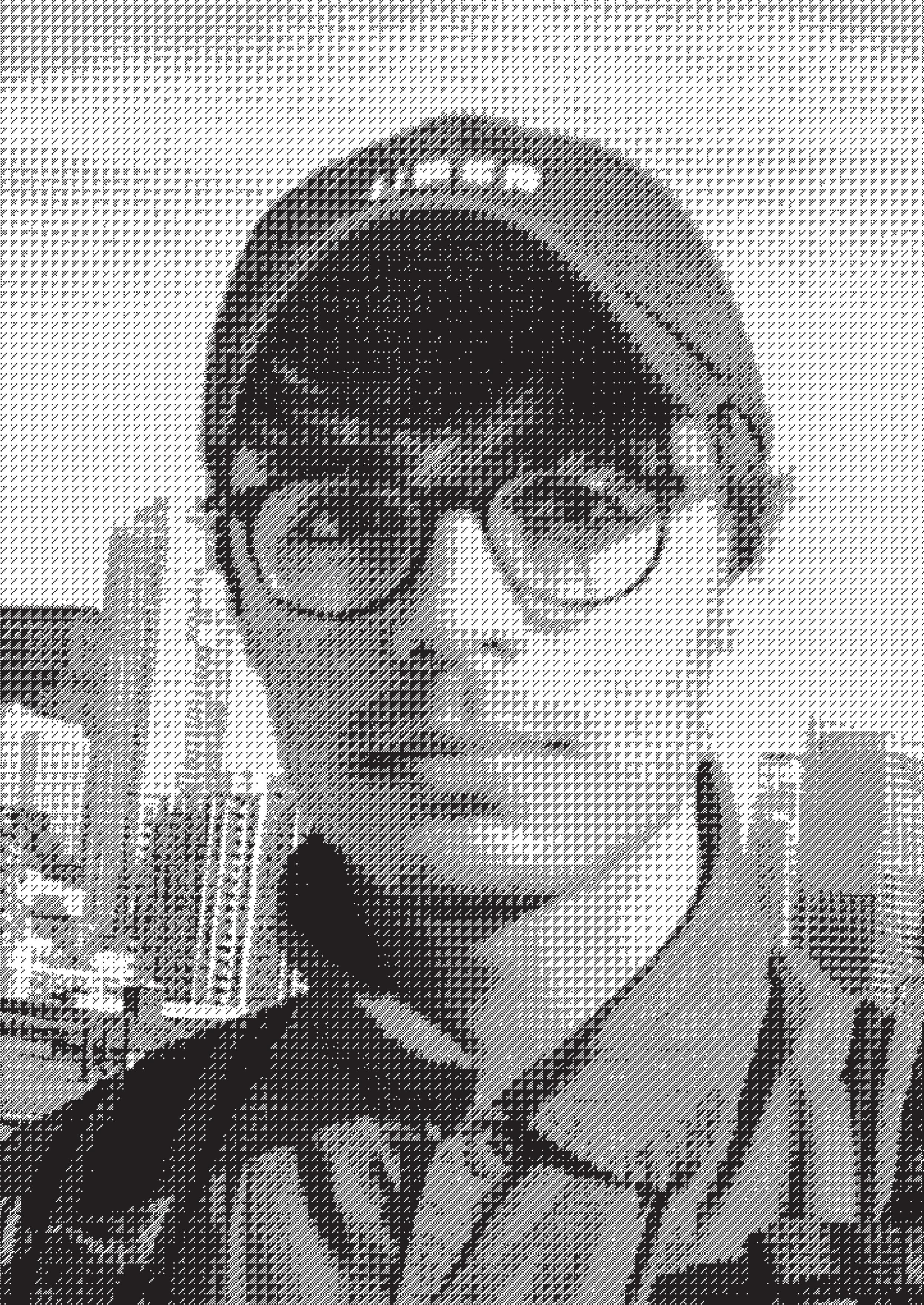

29 PHOTOGRAPHY FELLOWSHIP FELLOW SPOTLIGHT

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 30 NOOR GATIH ADAPTATIONS

Introduction

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 31

32 NOOR GATIH ADAPTATIONS

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 33

Kachely @kachmere

34 NOOR GATIH ADAPTATIONS

Rue @rue.greywal THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 35

36 NOOR GATIH ADAPTATIONS

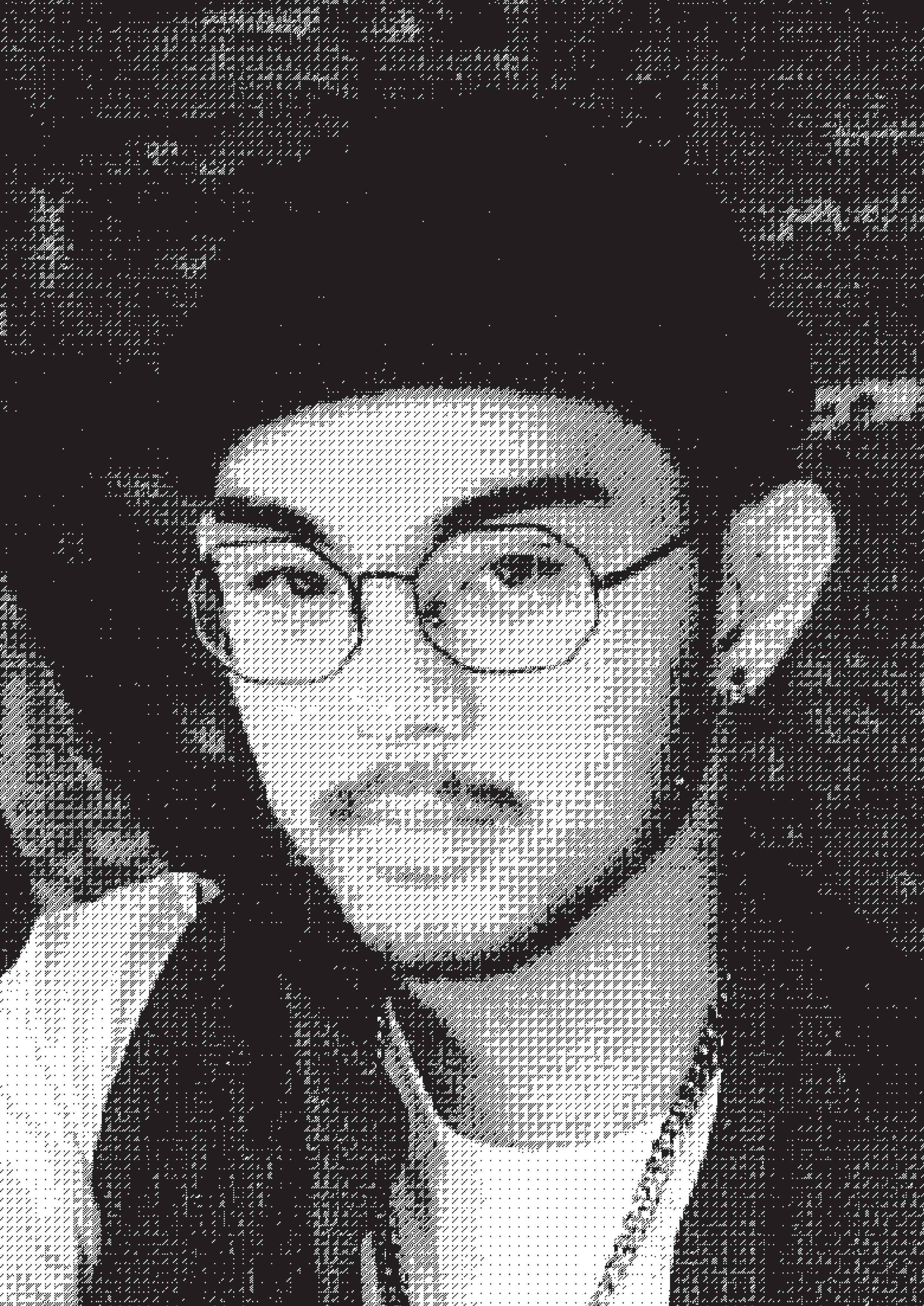

BOYFRN

@boyfrn

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 37

38 NOOR GATIH ADAPTATIONS

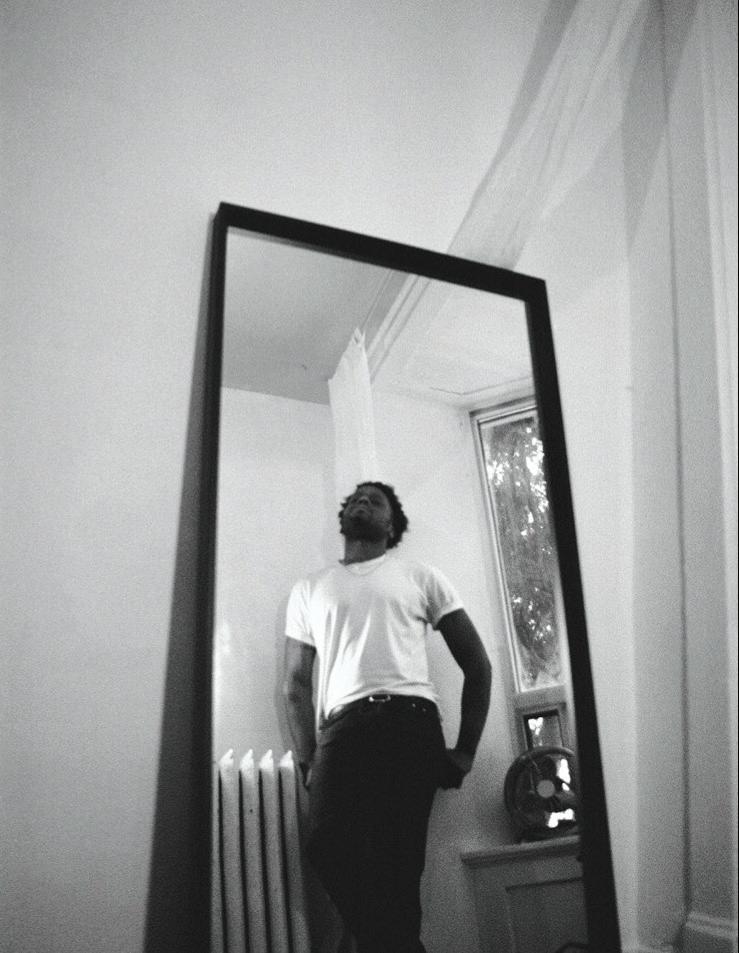

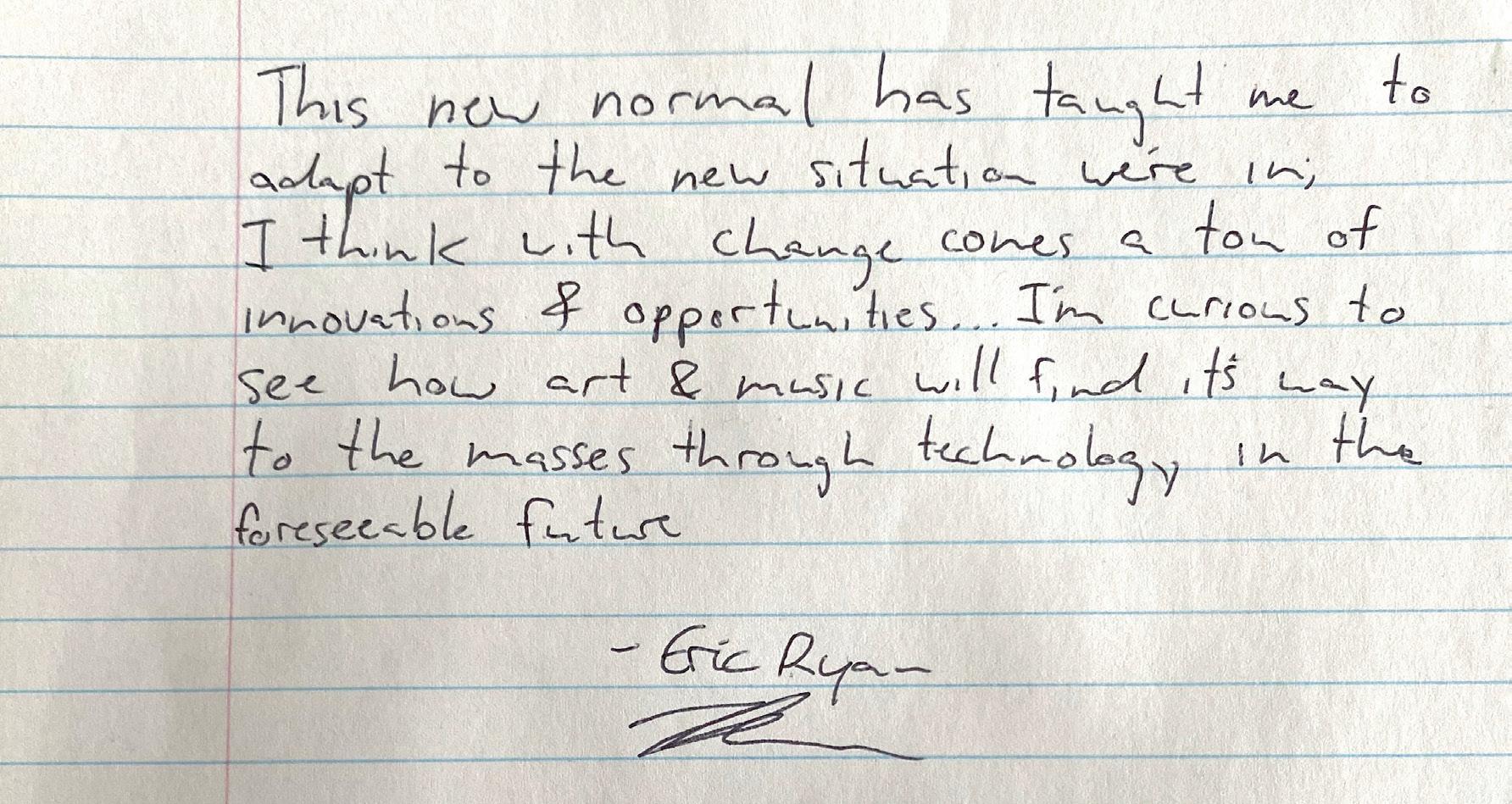

Eric Ryan

@ericryanpascual

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 39

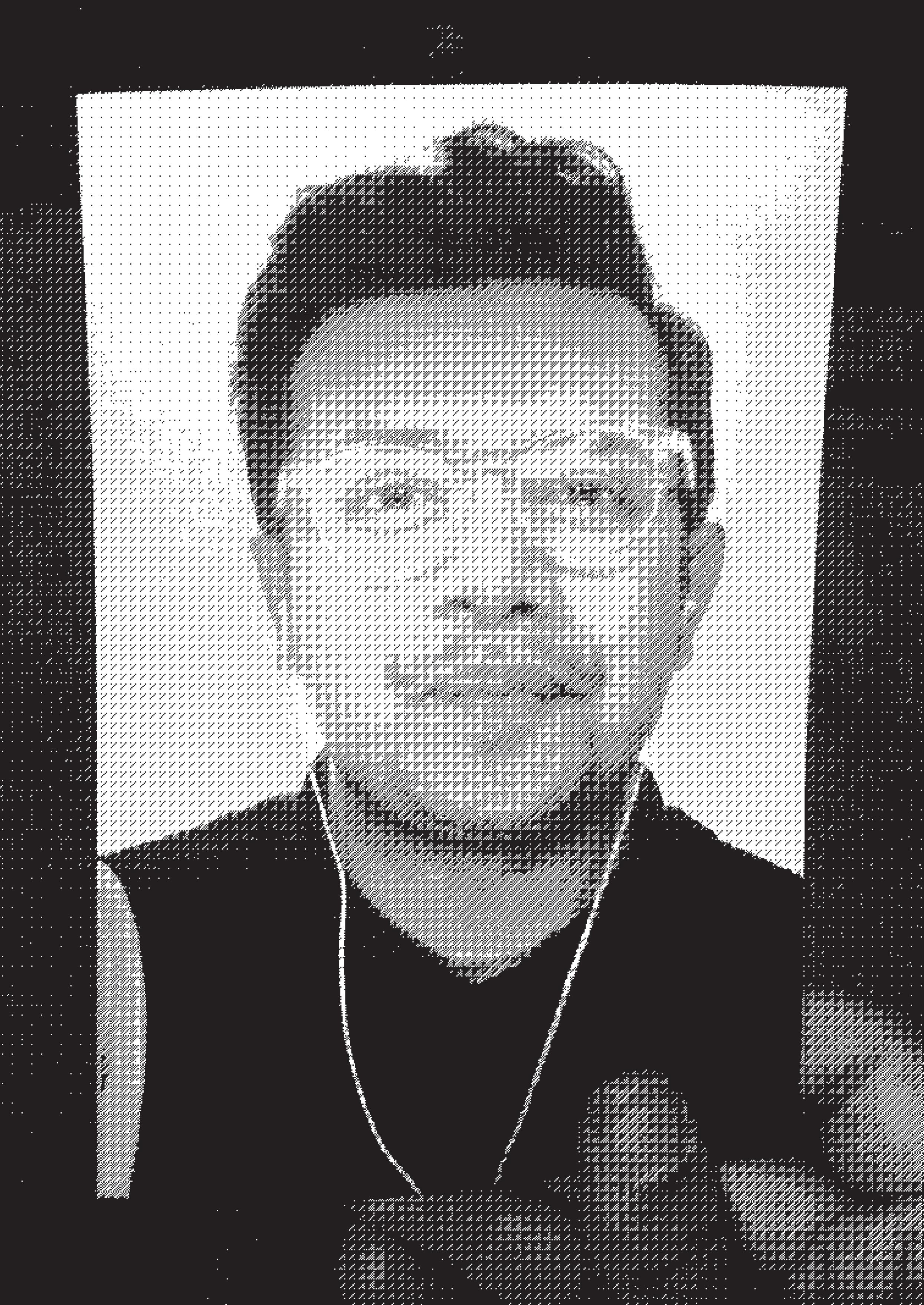

Kyle Mopas

Şōénder

BIOGRAPHY

Born in Toronto but raised in the quiet suburbs of Mississauga, Kyle first started out with visuals by recording his skater friends in the neighbourhood yet was always drawn to exploring the diverse city life. As a PHOTOGRAPHER , he strongly believes in pictures being worth a thousand words. Whether that be describing a subject or a scene, Kyle strives to CAPTURE diverse concepts within different styles and mediums that allows for limitless creative work.

STATEMENT

This project came into fruition when LOCKDOWNS and ISOLATIONS became a new normal for many people around the world.

This series took me into a different perspective, assuming the ones around me simply had a halt on their life due to the COVID-19. With the numerous days inside, the concept of Şōénder invaded my mind. Realizing that this halt on the normal affected people's goals, aspirations, and plans of the future, it made me realize the complexity of life and those around me. Şōénder represents a concept of where you want to go, become, and see, when you are in a state of isolation.

41 PHOTOGRAPHY FELLOWSHIP FELLOW SPOTLIGHT

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 42

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 43 KYLE MOPAS ŞŌÉNDER

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 44 KYLE MOPAS ŞŌÉNDER

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 45

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 46

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 47 KYLE MOPAS ŞŌÉNDER

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 48

KYLE MOPAS ŞŌÉNDER THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 49

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 50 KYLE MOPAS ŞŌÉNDER

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 51

Alicia Reid

Remembering Taste of Lawrence

BIOGRAPHY Alicia Reid is a Jamaican-Canadian Award Winning photographer based in Toronto. In 2020, she was announced as a grand prize winner in the Scarborough NEW VIEW contest. Her work is inspired by Caribbean and Toronto culture as she loves sharing moments that highlight PEOPLE OF COLOUR . Her goal is to make sure there is a positive outlook being shown in the city especially towards people in marginalized communities.

STATEMENT

Remembering Taste of Lawrence is a project dedicated to four local businesses in Scarborough located in the WEXFORD HEIGHTS area. I wanted to highlight and uplift these businesses as they’ve been keeping things afloat during the pandemic to serve and feed the COMMUNITY

Inspired by the annual food festival “Taste of Lawrence”, I wanted to pay tribute knowing that we aren’t able to experience it this year but still bring back that sense of joy and nostalgia there was there. My main goal was to showcase the variety of different DIVERSE FOOD businesses in the area that I feel represent Scarborough and encourage everyone to visit and support them especially during these times of the pandemic.

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 53 PHOTOGRAPHY FELLOWSHIP FELLOW SPOTLIGHT

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 54 ALICIA REID REMEMBERING TASTE OF LAWRENCE

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 55

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 56 ALICIA REID REMEMBERING TASTE OF LAWRENCE

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 57

Captain C Cakes and Ice Cream

2076A LAWRENCE AVE , Scarbrough

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 58

Crown Pastries 2086 LAWRENCE AVE , Scarbrough

ALICIA REID

REMEMBERING TASTE OF LAWRENCE

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 59

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 60 ALICIA REID REMEMBERING TASTE OF LAWRENCE

Sahan Restaurant 2010 LAWRENCE AVE , Scarbrough

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 61

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 62

FV Foods 2085 LAWRENCE AVE , Scarbrough

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 63 ALICIA REID REMEMBERING TASTE OF LAWRENCE

Kevin Ramroop FELLOWSHIP MENTOR

With his experience as an independent MUSICIAN and WRITER , Kevin co-leads the collective’s artistic projects. Utilizing his academic background in English at the University of Toronto and Music Production at Seneca College, Kevin also parlays his technical knowledge and creative instinct to lead the musical and writing component of the Wave Art Fellowship.

Natasha Ramoutar FELLOWSHIP MENTOR

As a journalist, culture writer, and producer, Natasha has covered urban music, television and movies, literature, and popular culture. Natasha was named Scarborough’s Emerging Writer of 2018 by the Ontario Book Publishers Organization. Her work has been included in projects by Diaspora Dialogues, Scarborough Arts, and Nuit Blanche Toronto and has been published in The Unpublished City II, PRISM MAGAZINE , Room MAGAZINE , THIS MAGAZINE and more.

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 64

WRITING FELLOWSHIP OVERVIEW

Anjali Chauhan

interfaces : ɪntəfeɪs

Anjali Chauhan is a from Scarborough's second-generation niche. As a POET she finds inspiration from each facet of her life, highlighting the connections between them through diverse styles of POETRY. Her work has appeared in University of Toronto (UTSC) MARGINS MAGAZINE and featured on Psychological Health Society social channels.

BIOGRAPHY

STATEMENT

interfaces consists of FOUR POEMS about my relationships as they manifest through common COVID activities. These activities represent interfaces, or the points at which I interact with people; some of these are digital and some are not.

1. “Curb”, describes a dynamic conversation between old friends at a curb, without a real outing.

2. “Disconnect” remembers the little things in an inperson friendship as a video call faces tech issues.

3. “Words” discusses family conflict during a game of Scrabble.

4. “Selves” relates myself to the community by contrasting the public and domestic as I go through my Spotify wrapped playlist.

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 67 WRITING FELLOWSHIP FELLOW SPOTLIGHT

interface | ˈɪntəfeɪs | noun

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 68 ANJALI CHAUHAN INTERFACE : INTƏFEIS

A point where two systems, subjects, organizations, etc. meet and interact.

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 69

Disconnect

Do you still [ ] me? There’s interference obscuring the interface between us where your eyes’ capillaries expanded into a film of exhaustion. Now, I trace your saccades along the few pixels as the webcam lens refracts your gaze away, wavelengths from your face propagating without the sinuous clack of your heeled boots, your soft pilling sleeves stretching around my shoulders.

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 70 ANJALI CHAUHAN INTERFACE : INTƏFEIS

and the dear oblivion of campus daze, that blur my varsity sweater’s collar the heated haze over your dark roast,

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 71

Curb

Tired from biking, we settled onto an ellipse of earth as if it uprooted from the middle school field and replanted at the curb of the Chengs’ two-storey home fifteen minutes away. Among our COVID bubble

of seven wafted a lattice of liminal conversations about boys and the stock market that lay over each other like our limbs, unmoving in the August sun which limned our soles. Through the arched path

of the tree’s shadow we traced the peaks and depressions of adolescence; no fumbles for Presto cards interrupted our low-lying space or longstanding interface. Interlaced, we faced the sedans, our bicycles, the bends at the ends of the abandoned road but for now, talked under the oak tree.

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 72 ANJALI CHAUHAN INTERFACE : INTƏFEIS

Words

Crossing vein is vain; when I hesitate to play assert, I choose terse. Lay letters as if I’d lose

a point for each tile, as if I’d lost an argument on how to spell my name. The family game of scrambling for blame, unscrambling me from misdeed, interfaces with the Scrabble dictionary

when my mother thinks pain should be spelled pane and recesses my distress like dust pressed into corners of our bow windows, like each word for “hurt” is a homophone I mean instead. When no u's are left to draw, my q_agmire cantilevers off a blank tile. She descends on it with tea (meaning cha or gossip) and challenges polysemy. A nongo - defense - retreats in my throat.

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 73

It’s only with headphones on that I scroll through Spotify’s memories of wireless fidelity to my selves, wrapped and stashed into an interface with purple house-party neon

grating spates of syllables, hi-hat cracks as brisk as the rap of others’ steps ticking my thoughts along as they sprinted for class. These beats faded with lockdown and I settled into distorted

stagnant time without a buzzing background; DIVINE’s guttural growl says he’d kept his distance since before COVID. Grocery trips are now soundtracked by Hindi boasts of partying, bass

leaving time to regroup. Workin’ out, sleepin’ in, takin’ vitamins. While Bored in the House rolls through the neighborhood like walking trails, I wonder how many others have memorized its lyrics.

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 74 ANJALI CHAUHAN INTERFACE : INTƏFEIS Sel

ves

and a library of album covers. These songs crossfade like selves I’ve shelved each month since March, when I read into rhyming couplets of hip-hop history, when 808s led

inflections of desi electronics, thoughts ticking with the kitchen’s erratic clangs. But, an introvert likes a lack of dialogue; my music lost its lyrics and let me write myself onto silent,

burgeoning out of car speakers, domestic to a country I visit through music videos. The hustle of hip-hop streams into and out with the dishwater, my two-minute commute to the living room

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 75

Luxshie Vimaleswaran

Appa

BIOGRAPHY

Luxshie Vimaleswaran is an experimental WRITER from Scarborough, Ontario. As a second generation immigrant, Luxshie strives to create a cultural context out of her racial individuality through her writing—exploring what it means to be an emerging artist in the TAMIL DIASPORA Her writing is fueled by her insatiable curiosity for investigating parts of herself and her place in the multicultural heartland of Toronto

Appa tells the story of a Tamil father and daughter, who in the thick of a province-wide LOCKDOWN find themselves seated alone with one another at the dining table as they have nowhere else to be. Brought together by a home-cooked meal and their shared anxieties for the future during a global pandemic, an emotional conversation is sparked between the two—an exchange that neither of them are used to. Slightly bewildered, yet comforted by her father’s unforeseen openness towards her, she reflects on the RELATIONSHIP they share and is reminded of the longing she has always had to be close to him.

STATEMENT

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 77 WRITING FELLOWSHIP FELLOW SPOTLIGHT

Appa

April in Rougefield is a cool, genial month. Its early springs are marked by balmy days and sprouting bulbs that splinter lingering blankets of snow with splotches of colour. As always, Mr. Antonio has gotten an early start on his garden; sporting a pair of non-slip clogs and sooty blue coveralls, he floats across the yard with his handy

pruning shears, removing the stale leaves and overgrown stems attempting to wreak havoc in his neat and tidy garden. Appa and I, lunching at our dining table, have the perfect view of Mr. Antonio’s serene garden through our glass patio doors. It had been Mr. Antonio’s idea to have both our yards be separated by a thin chain-link fence rather than large wooden frames like the rest of the neighbourhood. He believed too much seclusion would become lonely, and appa couldn’t find any reason to refuse his friendly proposal—that is, besides the occasional sweet fragrance of Mr. Antonio’s garden finding its way into our home, serving as a poignant reminder of the ghastly state of our own backyard. It was only a matter of weeks before appa began curling his lip at the sickly sweet scent, insisting that we shut our windows. Appa wasn’t always this morose—in fact his job as a taxi driver and his charming personality had made him pretty famous in the locality. He was the neighbourhood’s uncle, who’d take time out of his day to warn the teen boys not to drive recklessly with their newly issued driver’s permits, and who’d help carry in groceries for the spirited old ladies on our block, always shining their cheeky smiles at his well-timed interventions. I at times felt a creeping sense of envy when witnessing the bond he shared with these strangers, perhaps because it was yet another reminder of the shell of a relationship that existed between us. For the most part though, I never let it bother

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 78 LUXSHIE VIMALESWARAN APPA

me that he knew so little about me, like the fact that I spent most of my class-time scribbling prose in the margins of my chem notes, or that on most evenings, I was performing at Whitney’s diner from crumpled sheets of poetry that I’d sneakily tuck into the pockets of my jeans before running out the house. The sort of things that would at best land me in the middle of hour long disputes about “where they went wrong” as amma and appa take turns shifting blame on to one another for their child gone rogue. I realized early on that it was easier the less that appa knew, and it wasn’t hard considering how little we spoke for me to keep it that way. What was difficult, however, was feigning oblivion over the years as I watched appa slowly withdraw from the man I once knew him to be. His social interactions had become curtailed to a degree that worried us all. I noticed the way he began resorting to his afternoon strolls as a means of willfully cloistering himself away. On the days that amma pushes me to join him, we walk side by side, sensitive to the wind and the discombobulated voices from afar, our silences punctuated by appa’s groans as his legs begin to give out beneath him—his rhythm-like-step now replaced by a sluggish walk, no longer looking to strike up conversations with passersbys as he once did. At times, I look over at appa and wonder if there are any words I could say that might make his pain less grievous, but in those moments, I am reminded by the blaring arrows of sunlight bathing our path that appa and I have never known softness between us in the way that we should.

Appa often chooses to dine from the comfort of his recliner while watching live updates of the virus stream on television, but with the recent flood of headlines about a potential third wave, it seemed even the snug warmth of his favourite chair couldn’t help him stomach the constant wave of bad news. I’m surprised when he asks that I join him for lunch. I seat myself across from him at our dining table, tapping my foot nervously against the kitchen tile—the cold-to-touch marble sending involuntary shivers up my spine. I stop when I realize the way my tremors are causing the already uneven table legs to quake against the kitchen floor. I begin mulling over all the possible reasons for him to spring this lunch on me without warning, while appa proceeds to mount sambar on to his silver dish, seemingly indifferent to this impromptu luncheon of ours. Despite having spent the past few months quarantining together, appa and I for the most part have taken to staying out of each other’s way while amma is gone for work, alternating in our use of the tv in the family room, or the occasional small talk when bumping into one another at the refrigerator. I often consider, if it weren’t for our being confined to these four walls, if we’d be speaking at all. Stacking appalams on to my plate, I brace myself for what I imagine will be yet another long, wonderfully life-affirming speech about the many reasons why medicine is the most noble profession in the world—either that, or it’s suddenly dawned on him that he has not yet married off his twenty-four year old daughter, an inevitable epiphany for every Tamil father that I have long suspected would come rearing it’s ugly head. “Have you taken beetroot ma?” appa asks, pulling me out of my thoughts, as he concentrates on transferring a spoonful of the fleshy vegetable onto my plate. “Thank

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 79

you,” I mumble, as I slyly shove it to a corner, keeping it from touching the rest of my food. We slip into a lengthy silence. The kind that is expected, and yet, is charged with an alertness that leaves my mind wrestling with more than just the absence of words. “I.. spoke to periappa” he starts. Great, here it comes. “He says if you’re interested in Michigan, he’d love to have you stay with them until you finish the four years.” More like ten, I nearly scoff. “Thanks appa, i’ll look into it'' I curtly dismiss. After having my manuscript rejected for the third time this month, my hopes of becoming a published author were beginning to feel like an even more distant dream. I’m definitely in no mood for appa’s tangents about med school, though he does seem to possess a natural flair for capitalizing on some of my lowest moments. The patio door stands slightly ajar and through it, the breeze enters the kitchen, caressing my bare face and fiddling with the ends of my hair. “Any, erm.. updates on your book?” he seems hesitant to ask. Appa always finds a way to make himself sound as far removed as possible from any plans of mine that do not involve pursuing medicine. I shake my head no as I look down at my plate, feeling the flush unfurling in my cheeks. Memories from that night a year ago are still fresh in my mind. I recall the way I stood anxiously with my ear pressed against the bedroom door, struggling to hear over my rampant heartbeat. At first it was only amma’s voice that I could make out, muffled by the mass of wood wedged between us. “Just let her do what she loves,” she pleaded, sounding better than when we had rehearsed. I prepared myself for his wrath, taking a step back from the door so that when he decided he could no longer swallow his anger, my ears would not have to pay the price. To my surprise, appa never did yell, but what I heard instead was even more of a fatal blow to our relationship than any tongue lashing could have been. I became aware of two things that night. First, was that in appa’s eyes I was just a deluded young girl, clouded up with daydreams— and second, that something was now lost between us, that I knew I would never find again.

The quiet is not unfamiliar to us. Appa and I have always been accustomed to communing almost wordlessly. In the rare moments that we find ourselves spending alone time together, we welcome silence to sit between us like an old friend, ‘til our thoughts turn into musings—the world around us drowned out by the cacophony in our heads. If that night a year ago changed anything, it was our moments of companionable silence that were now replaced by resounding feelings of unease, discomfiting in the way the truth so often feels. The thick, low hum of stillness pulsates through the kitchen, forcing our attention to the outdoors where the echoes of Mr. Antonio’s daughter’s squeals can be heard as he throws and catches her in mid-air. Appa chuckles ruefully, and for a brief moment, I imagine that he is trying his best to ignore the rising lump in his throat in the same way that I am—for some reason, finding solace in the thought. “Remember those piggy back rides you used to love? Your arms were so tiny that you still had trouble reaching the berries!” he laughs, the sound of his laughter, at once comforting and unfamiliar. I hark back to some of my earliest memories of berry

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 80 LUXSHIE VIMALESWARAN APPA

picking with appa, when I would silently tug on the leg of his trousers, until, as if by instinct, he’d lower himself into a crouch and I'd wrap my small arms around him. “I remember,” I say, my voice small as I look out the window at the state of our berry tree now. Its brittle branches hang loosely over the fence and its vines are covered in powdery mildew, leaving me with only the memory of its full-bodied taste of berries as proof of the tree’s once robust past. I glance at appa, who now, appearing lost in his thoughts, stares sightlessly out the window. For the first time I notice how much his look has changed. The ebb and flow of time had chiseled away at his wizened face. His fully grown pepper-grey beard that he had acquired while being forced into months of unbroken solitude, now hides wrinkles etched into his craggy cheeks. “What is your story about?” he asks suddenly. It feels as though my mind is momentarily paralyzed. I scour my brain, trying to come up with the right words to tell him. Appa stills the rattling table with his non-eating hand, and it is only then that I realize the way my leg has once again began to tremble. “Sorry...” I mumble.

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 81

As a child, I sat on the well worn seats of appa’s taxis on countless occasions. Each trip took me on an unexpected path, as customers, new and old, filled in and out of appa’s cab, bringing with them stories and destinations that I had never before seen or heard. Tales of estranged children, first days on a job, divine interventions and everything in between. In what felt like a confessional on wheels, appa surprisingly never contributed much himself, perhaps because I was there. I guess the whole set up of anonymity between the driver and the passenger and the momentariness of these encounters are what make for the perfect opportunity to reveal one’s deepest intimacies. How strange it is, I used to think, that people find it so much easier to be vulnerable with those they barely know. As I sat in the passenger seat, collecting fares and feigning innocence, appa could tell by my eyes that they were full of mischief from being let in on adult conversations that I had no business listening to. “Remember” he’d tell me, his voice serious. “Your education is all that matters. Don’t get caught up in this rubbish”. According to appa, stories were nothing more than a fruitless distraction from reality, which coloured his opinion on books itself, deeming any fiction but the Harry Potter series to be a waste of time. Little did appa know, those taxi-runs were what would give birth to my undying love for storytelling as I grew older.

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 82 LUXSHIE VIMALESWARAN APPA

“You don’t have to tell me” appa says after a quiet moment. By now I've dug a hole into the mountain of rice on my silver plate, staring intensely at my ensnared reflection. Still not having come up with a coherent response, appa decides to break the ice. “I’m sure it’s great,” he offers, and I look up at him in surprise. Appa’s chair lets out a creak as he steadily rises from his seat, clutching clumsily onto the kitchen table for support. As he makes his way to the sink, the silence stretches between us. There is a subtle difference in air pressure in the room now—somehow lighter than before. I release the breath I hadn’t realized I was holding. Appa returns with a box clasped in both hands and I instantly recognize the crimson-red colour. The packaging of my favourite bakery. The small gesture makes my heart swell with gratitude. “Thank you appa” I say as I reach for the desert inside; an eclair, garnished by the perfect assortment of berries. Appa joins me, and together we sit and indulge in the oblong pastry. We take turns plucking the tiny globes and plopping them into our mouths, savouring the familiar sweetness of each berry, laden with rich purple juice. “You know, I'm proud of you, ma. I know how much your writing means to you.” appa says. For a moment, I am so afraid of being robbed of these words that I pretend I don’t hear him. “You do?” I eventually ask, my voice unable to mask my suspicion. “Ofcourse” he responds. “I knew from the moment I saw that you could remember every seven-letter scrabble word, and not a single row of the periodic table,” he laughs. A feeling I don’t recognize overwhelms me, and I feel my eyes brimming with tears. “Our dreams are what carry us forward. I wish I'd done a little more of that—dreaming, I mean.” I look at appa who now has an emotional look on his face. I welcome spontaneous flashes of memories from my childhood. I remember sitting comfortably in appa’s lap as he’d circle his elbow on my tiny palm, imitating the mixing of a bowl, before he’d run his stubby fingers up my arm, preparing to feed me a pretend ball of pittu. The game would end in my uncontrollable fits of laughter as he’d attack me with his tickles—a moment of vulnerability that appa rarely had. In a sense, it is the first time I am really seeing him again. I had never imagined appa to be someone who had dreams of his own. Perhaps, I had spent too much time confusing his self-betrayal for selfishness. I feel the gentle squeeze of my hand as appa proceeds to make his way to the patio door, sliding it open and stepping out into the afternoon sun. I watch as he picks up a pair of shears, motioning for me to join him, and I do.

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 83

Mahdi Chowdhury

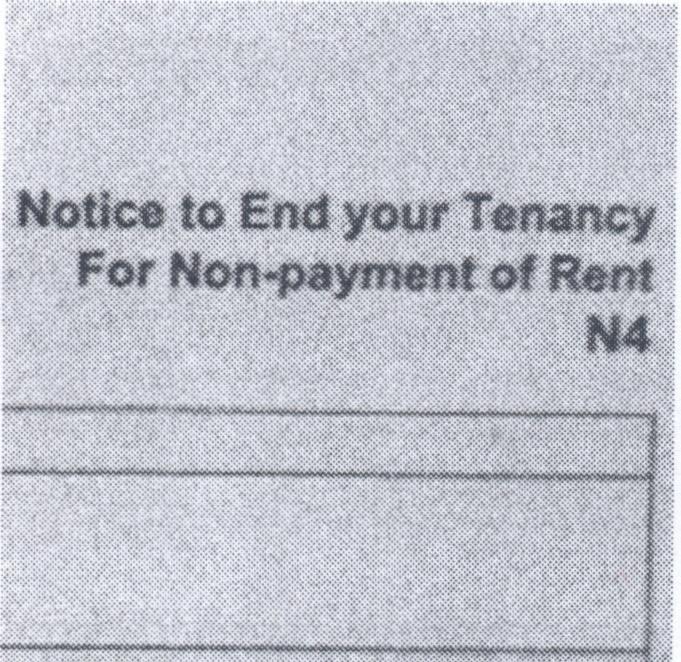

Form N4

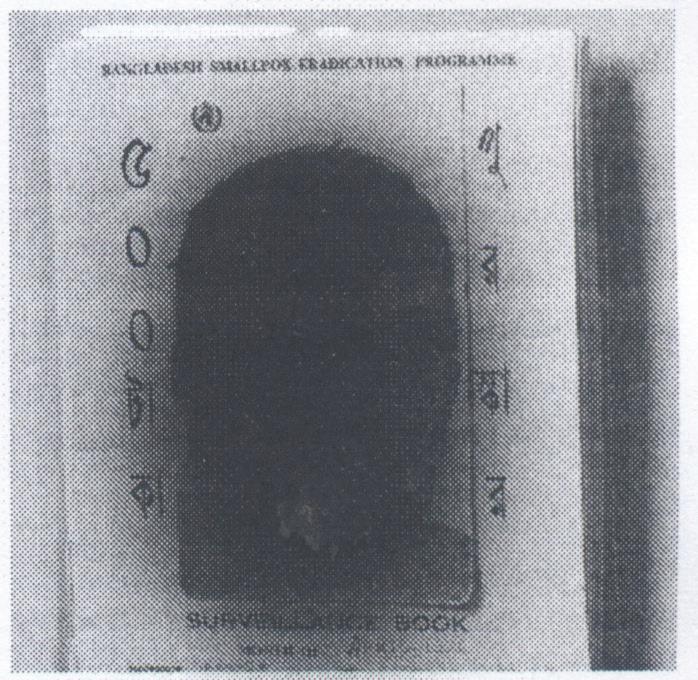

BIOGRAPHY Mahdi Chowdhury is a WRITER , DESIGNER , and historical RESEARCHER based in Scarborough. His work has been exhibited in New York, London, and Dubai and published in Popula, Caméra Stylo, and Himal Southasian. He is presently an Editor-at-Large at the Toynbee Prize Foundation

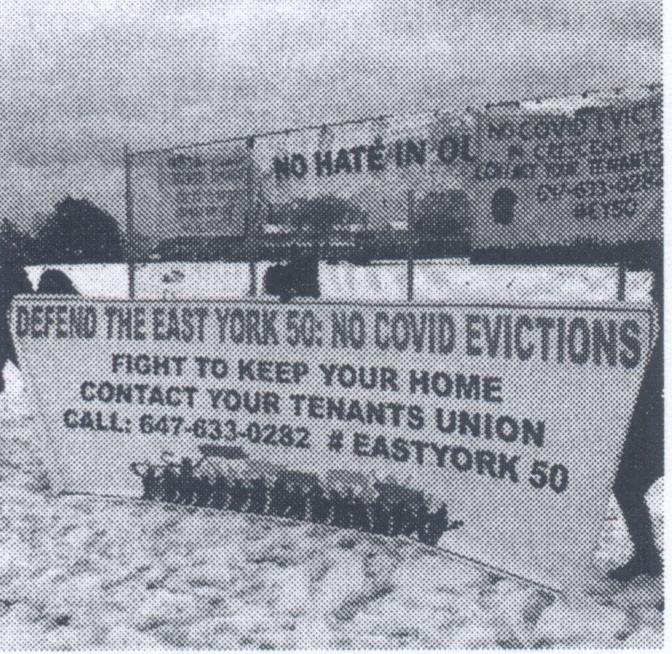

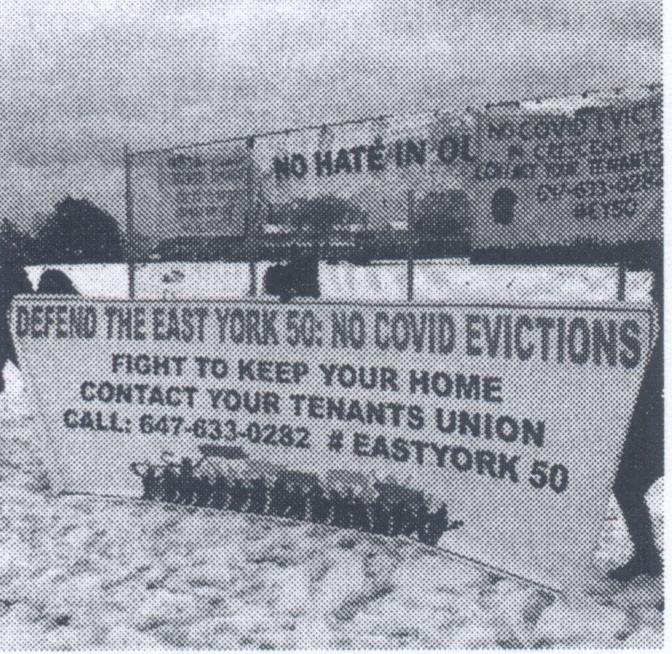

STATEMENT Form N4 is a visual-textual coming-of-age story that takes place across the processing span of an eviction. Set in Crescent Town in the early months of the pandemic, it follows the emotionally intelligent yet stress-filled interiority of its child protagonist, Lubna. Dedicated to the East York 50, “Form N4” explores the entanglements between a family like Lubna’s with the themes of childhood, Bangladeshi DIASPORA , CLASS and community ACTIVISM, and spatial histories of Crescent Town.

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 85 WRITING FELLOWSHIP FELLOW SPOTLIGHT

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 86 MAHDI CHOWDHURY FORM N4

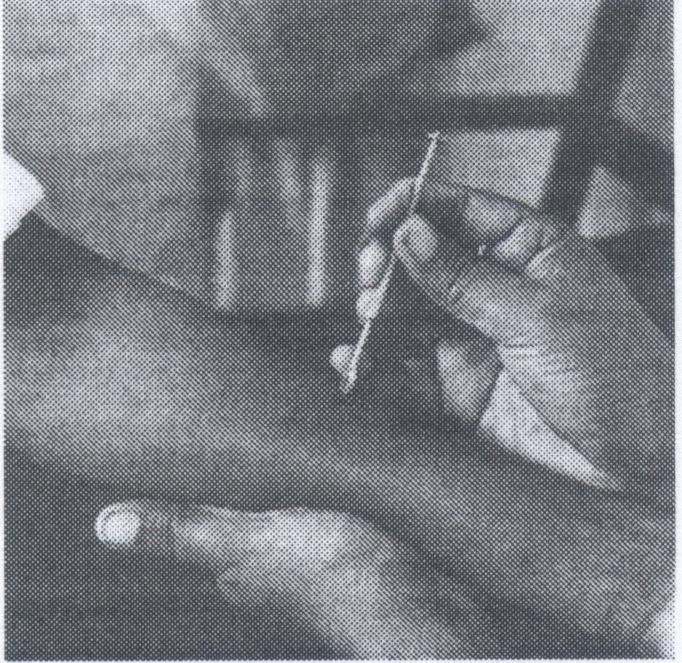

A pale moonlight filled the room. Arm outstretched past the edge of the bed, Lubna could feel the cold air emanating from the floorboard on her fingertips. Her mother slept next to her. Her face was murmuring. Staring into the dark architecture of her mother’s face, Lubna could feel herself dissolving into quietness. Her mother’s face, a night within a night.

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 87

The scars on her mother’s arm caught the light. One was soft and craterous. The other was glassy. It resembled a pond covered with

ice. A foreign doctor vaccinated her mother and her uncles in Comilla. The needle was cold and two-pronged. She was the same age then as Lubna was now. Looking at her mother’s vaccination scars, Lubna could not put her ropy feelings into words. She felt a kind of sadness; mothers were once children too.

The air in the apartment was bruised. Bruised in the way air is after a fight or calamity. Her thirteen birthday was a month away. Adults forget how much children

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 88 MAHDI CHOWDHURY FORM N4

understand. Turning on to her back, Lubna gazes at the constellations hidden in the stucco ceiling. She charts them through drowsy eyes: a cow, a face, an Arabic letter. Dimming her eyes, concentrating and abstracting her vision, she imposes a house. Doing this, Lubna would soon fall asleep.

Crescent Town is a complex of apartment towers between the boundaries of East York and Scarborough. Its towers loom over the city’s Little Bangladesh. Arriving from the old city of Toronto, the Danforth disappears upon itself. The streets become wider and dimmer, fatigued and anonymous.

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 89

Its concrete topography offers signs of the Massey dairy farms that were once here.

The parking lot of Shoppers World chalks the outline of what was once a Ford Factory. The Williams Treaties of 1923 stripped the harvesting rights of First Nations from this exact land. Fishing, hunting, and trapping became prosecutable crimes. In 2018, the Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations acknowledged these treaties forced “mothers and fathers [to be] unable to provide for their families as they had before.”

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 90 MAHDI CHOWDHURY FORM N4

Everyone woke up in time for

lunch. There was still rice in the rice-cooker. There were lentils with mustard seeds and fried steaks of liver. The eviction letter was no longer on the table. A soft dot of oil had soaked into the paper.

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 91

The table was thought to be clean but somehow the letter was stained. Her father’s eyes were dry from the night shift. When he would come home, he would try to be quiet while microwaving his dinner. He was less successful being quiet with his added ritual of taking hot showers before bed. Lubna and her mother would pretend their sleep was not disturbed by his entry home so as to allow him the courtesy he offered them. That cycle, however, had ended. As of that morning, he longer had his job. The turmeric-hued oil, moon-like in its location on the page, added to an ineffable feeling of failure. That this was deserved. That, if we show this letter to someone, they will think we live like animals. The letter was now stored away, out of sight, in a plastic drawer.

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 92 MAHDI CHOWDHURY FORM N4

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 93

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 94 MAHDI CHOWDHURY FORM N4

Lubna rarely saw her father in the daytime and enjoyed using his phone. The fading, cereal-hued sunlight that filled the apartment reminded her of weekends. She would otherwise be in school at this time. A returning melancholy. It felt like their first day in a new country. In their ribs was a tiredness from the airplane, a transitory drowsiness; it felt as if they had become, once more, unfurnished people; uniquely alone; the words from their mouths and the figures of who they were were now meaningless, incomprehensible, pathetic to everyone outside the apartment. She felt this without knowing how to say it.

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 95

Nobody else knew. This was their final month. What savings there were went to his mother. They tested everyone in the dialysis centre for coronavirus and she tested positive. Without delay, she was taken to a new quarantine hospital on the other side of Dhaka. But, she was fine after that.

Faisal Miah called on WhatsApp and told him to have courage. He said the Bangladeshis were leaving Italy but he was staying firm. This is all for nothing,

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 96 MAHDI CHOWDHURY FORM N4

you just have to take a hot shower to make sure the coronavirus does not stick to you, he repeats with orthodoxy. At some point, Lubna’s father stopped listening to the voice on the speaker. Rent, food, dialysis—and then there is no more space even with CERB. Lubna’s mother speaks to Faisal Miah on the phone: the woman from the mosque helped organize a food-drive in the building and, can you believe it, Bengali people were taking charity. When the call ended, Lubna asked if she could use his phone again.

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 97

The next day the burring voices arose from below. “Keep your rent!” Peering down and covering her nose and mouth out of instinct, Lubna’s mother looked at the activists. Lubna joined her mother and the congress of balconies in attendance. Some hung banners of solidarity. Looking nine stories below, Lubna and her mother were, in turn, looked back upon, here and there, as an affirming tableau to the activists who were touched to know for whom they were here on behalf of. But in championing them, in speaking of community, an anxiety later settled in her mother. She was, in a sense, named from outside—she realized herself in the crisis they sought to stop. And then, she felt alone. Her predicament

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 98 MAHDI CHOWDHURY FORM N4

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 99

became a physical reality and the eviction date felt like an object lodged in her throat. “Keep your rent!” A just world demands so bravery from the most vulnerable.

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 100 MAHDI CHOWDHURY FORM N4

Then, a speaker who spoke in meek English asked if she could say some words in Bengali: “John Tory came to Dentonia Park to unveil a Shahid Minar and give his respects to our language struggle—but if we, Bengali people, are being evicted, thrown out of our houses, made to no longer exist here, what is the purpose of this respect? We need to make sure John Tory will allow us to keep a roof over our heads. We fought a war to protect our language, our land, and our people—and now, in the city of Toronto, must fight a similar war for our existence. We must fight for everyone in our Crescent Town community.” And in English once more: “We love ourselves and we love our community.”

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 101

When the family down the hall tested positive, everyone made sure they never missed a meal in quarantine. The comunity activists arranged socially distanced, outdoor activities for children. Holidays like Holi and Eid were celebrated in the foyer. At the same time, the evictions began. A barbaric epithet: “online eviction.” Everything was recorded. Young lawyers sat in to represent the tenants to the Landlord Tenant Board. And yet, the ground they stood on became water. It only took a few minutes

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 102 MAHDI CHOWDHURY FORM N4

Lubna knew her parents tried not to place any burden on her and the ultimate burden was money. Her parents shielded any mention of it. Yet every anxiety that suffused the air was internalized by her—and, at times, the world felt like an elastic band ever-stretching and ever-aching. She felt a stone in her stomach, a stone in her heart. And in the corner of her eye, the soft, sudden glow of the open refrigerator. Her mother rose up beside her and her father entered the room: a birthday cake on the perfect edge of midnight.

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 103

Years later, in the debris of the pandemic, Little Bangladesh continued in motion like warm, static rotations of a vinyl one-ridge maligned. School reopened and the tutoring centre called back to inquire if we were free this summer. On the way, there was a cannabis dispensary where there was once a passport portrait shop.

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 104 MAHDI CHOWDHURY FORM N4

In the basement of the tutoring centre, whose fluorescent tube bulbs hummed like insects, I saw the familiar faces of old students who had grown so tremendously—and yet, so much like nocturnal plants and fungi that took their light from the moon. I still had a few of their papers from years ago marked in thin green ink. I passed them back to them like they were souvenirs. When I came to Lubna’s name, her friend at the corner of the cubicle raised her hand. Her family moved away. “I don’t think they live in Toronto any more.”

“Cholera, typhus, typhoid fever, smallpox and other ravaging dis eases spread their germs in the pestilential air and the poisoned water of these working-class quarters. Here the germs hardly ever die out completely [...] Capitalist rule cannot allow itself the pleasure of generating epidemic diseases among the working class with impunity [...]”

—Friedrich Engels, The Housing Question

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 105

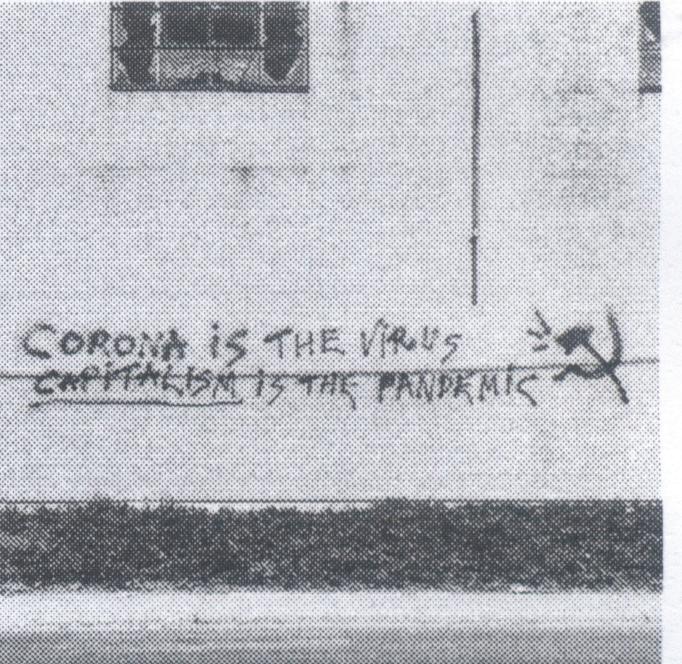

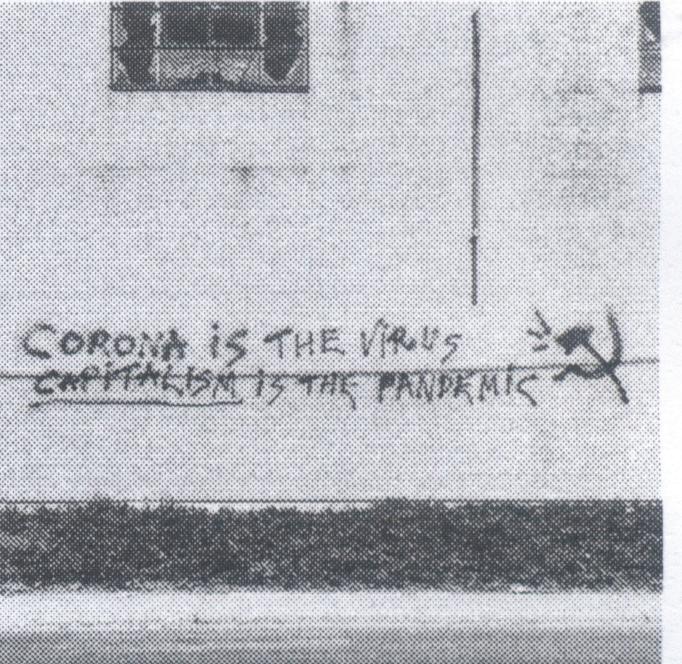

Later that day, I tried to find a friend in a convoluted part of Toronto where there was the unusual presence of film studios. Near the parking lot of a grocery store, dozens of masked people were lined up at night awaiting for the bus to go home. The graffiti on the wall opposing them was writ large:

One could not tell if it was for a movie or not. In the line of commuters, there was an older Bengali man on the phone, commenting on the excessiveness of the line: “It’s like a war.”

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 106 MAHDI CHOWDHURY FORM N4

“COVID IS THE VIRUS, CAPITALISM IS THE PANDEMIC.

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 107

Dedicated to the East York 50 and the struggle for life-needs.

Tina Guo

The Sky in The Well

BIOGRAPHY Tina Guo (they/them) is an artist-writer living between Toronto, Canada and Berlin, Germany. They are fascinated by the humananimal desire to fill and be filled—eating, dwelling, burying, making love—how our bodies can transform into interchanging vessels that carry one another and the environment at large. They have recently shown work at Art Toronto.

The sky lives in the well. The well reflects the sky. The Sky in The Well is a series of nine vignettes told from the interchanging perspectives of a young factory worker and his middle-school niece. Moving through the duration of the pandemic, their story DOCUMENTS an escalation of domestic violence and a gradual shedding of personal boundaries.

STATEMENT

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 109 WRITING FELLOWSHIP FELLOW SPOTLIGHT

The ringmaster bought a monkey that knew how to dance but did not obey his drum. So he began by drumming for a dumb rooster that, of course, just squatted on the ground. Then he picked up a hatchet and slaughtered the rooster. The second time he drummed, the monkey danced without missing a beat. Hence the proverb “kill chicken frighten monkey.”

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 110 TINA GUO THE SKY IN THE WELL

What was he looking for again? It had slipped his mind as soon as he pushed through the revolving door.

He was alone in the aquarium. Before him, a sheet of blue glass stretched from floor to ceiling. A few fish swam on the other side—some red triangular ones and some flat brown ones. He saw rows of teeth when a red fish cracked open its jaw. It swam up to a brown fish. The brown fish stayed so still.

His face was wet. He couldn’t move his body. He couldn’t breathe. He forced his eyes open when he felt another drop. A pair of dark eyes loomed over his face. They were leaking.

“Fuck!”

The eyes backed away. Underneath his palm was the texture of his blanket. There was Niece, sitting on top of him in her purple polka dot pajamas. The white of her eyes glowed behind her hair. She had been crying.

“Are you okay?”

She shook her head. Her face was illuminated by an orange rectangle. Winter nights were always bright. The sky was the color of streetlights reflected by snow. He sat up and they both looked out the window for a while. The children’s playground looked like a small white tent in the white square. A few windows were lit yellow. He didn’t know the time.

The alarm had not rung. “Does your Ma know you’re here? You should’ve woken me up. Why didn’t you wake me up?” Niece thought the question over. Sitting curled up with her knees, she looked like a small child. She was almost taller than him when they stood side by side.

“I thought you would hit me,” she said finally. Her eyes were still outside.

Then there was music. He fumbled around the room until the phone hit the floor from the back pocket of his jeans. The screen showed 4 AM. The blue light hurt his eyes.

“I know you wouldn’t. Not you, you wouldn’t.”

He searched for words but he couldn’t find any, so he got up and draped one of his blankets over her body; a small white tent. She flinched when his hand grazed by her neck.

“I’ve got to get to work. Just stay here today, okay? Let’s talk when I’m back.”

He watched the white tent with the rise and fall of her breathing.

“Try to go back to sleep, okay?”

Niece tucked herself into the covers. Her brown face peeked from where he used to lay. Her eyes followed him until he shut the door.

“Have a good day,” she whispered.

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 111

1

Dark willow leaves brushed over the two halfmoons. She had always loved Ma's face. Hers was a tenderly sculpted, refreshing kind of face—two eyes, a nose, and a mouth exactly like Uncle’s.

In the mirror, a pair of dead-fish eyes watched as she squeezed the pus out of another bump. She wondered if the craters in her skin would deepen to match D.D.’s. Would she too become full of holes like a worn pin cushion? She fantasized about putting the pins into his face, pushing them in until they disappeared completely.

The cut that blended into her lips wasn’t swollen anymore. She opened and closed her mouth until a bead of yellow came out. “Two of the same mold,” said Ma. She wanted to rip her face off.

Sometimes it was a person. Sometimes it was a couple or a group. Sometimes it was a crowd. Whether from a tent, underneath a waterfall, or in a dim plaza, the figures stared back with wooden eyes and bodies in mid-activity. The living room was littered with these paintings. He couldn’t make out the backlit faces on the windowsill at 5 PM but he knew they were watching.

“Careful around those ones, they’re still wet.”

Niece didn’t look up from her blue fingers. She was plucking thin hairs from the brush.

“I left the palette out last night. I know, a tragedy.” By tragedy, she meant Cat.

They were pedestrians in the background of her panorama shots, she explained. She liked how they looked like they weren't supposed to be there, like something else had decided to arrange them like a bunch of cardboard cutouts.

“How was Zoom school today?”

“I put it on mute.”

“You’re going to make your Ma cry with that attitude.”

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 112

2 3 TINA GUO THE SKY IN THE WELL

“That’s why I still bother going. Plus, I think she’s already the saddest anyone can be.”

“You’re really not considering anything besides that academy in Michigan? We’ve got some pretty good high schools here, you know, for art or something else.”

He looked at her, her backlit silhouette sitting cross-legged on the coffee table, working away on the thin easel squeezed between the lamp and the dinner table. Behind her, the window was a large, gray rectangle.

“Your Ma is worried about you.”

“So? I’ve already decided. I won’t be bothering any of you soon.” The easel thudded backward. She kicked it back up with a screech. Maybe he shouldn't have said anything, but he had also made up his mind.

“Anyway, she told me it’s a boarding school. What are you going to do when things go back to normal? Hate to break it to you, but you won’t be able to hide in your dorm all day.”

Frankly, he could not imagine Niece interacting with anyone besides himself, her Ma,

and D.D. She had rarely spoken to the GF and never, under his observation, made an attempt to play with Cat.

“I think I’ll try to make friends,” she looked up. They stared at each other for a while.

Cat stretched lazily on the windowsill. It had managed to occupy the space between two smaller rectangles. Outside, sixteen rows of congruent windows lined the opposite building. From one of them, a shiny brown head poked out and a cigarette butt dropped into the white ground.

“You see that geezer over there?”

Niece pressed her face against the window.

“Yeah, what about him?”

“Looks like one of your paintings. Except the guy lives in a window and he’s not looking anywhere in particular.”

He could already hear what she was about to say, the words she had repeated often since she became obsessed with the academy. He didn’t know what he was talking about; he should just let her be. But she shrugged.

“You might be right.”

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 113

The stench attacked when Uncle opened the front door. She leaped over the yellow patch and the bottle’s remains.

“Hurry up or you’ll catch the stink!”

She gagged. In truth, she was quite unfazed by now. She was no longer sure whether she came here out of necessity. The thought irritated her. For that reason, she never displayed any hesitation when it was time to leave.

The half-moon eyes between the hood and the blue mask were looking at the red numbers above the elevator. All covered up like this, Uncle was like a young Ma in careless clothes, with soft eyes that seemed to be smiling. The young, still intact Ma before she met D.D. He told her if she zoned out hard enough, the light would become alive.

“Not really,” she lied. She did see the red wriggling stars. She looked at them for a long time.

She liked being in the elevator with him, sharing a minute in a space that belonged to no one else. Her first time here had been a different story. It was like a metal box had teleported her right through the edge of her world. No railings, no mirrors, no wallpaper, and no carpet—it was nothing like the elevator in the condo where she and Ma lived.

She could see her condo from his living room window. It was a tall, blue rectangle sandwiched between two other identical ones. He told her those buildings had not been there when he was younger. Instead, there had been a series of low rise warehouses where he would pick up ceramic samples. The capitalists stole his sunset. There was

so much beauty in the world for everybody, Uncle complained. Now three dumb blocks interrupted the horizon. She imagined a tiny Ma in one of them, debating whether to come pick her up.

The elevator dinged. Uncle gave the door a shove and she slid out from underneath his armpit. There was Ma, standing on the driveway. Ma handed her a plastic container full of steamed buns and waited for her to pass it over to him in the lobby. Ma never stepped foot in Uncle’s building. Ma was a germaphobe who always doubled up her masks, wore disposable gloves, and showered as soon as she got home.

“I felt like walking with you,” Ma said, and they walked.

She knew Ma was scared that if she didn’t show up, she would never come home.

“Uncle is a busy man, with a tiring life, and a girlfriend too. You sure you’re not bothering him? Staying so long this time.”

“Then where would I go, Ma?”

They walked in silence for a while. Then Ma felt like she needed to apologize, again. She was worried about him going to the factory. And the GF, working every day at a grocery store. What if they passed the virus to her? What had she been eating? Ma felt bad about what happened. Ma missed her. The January wind cut her face until she tasted metal in her mouth. She missed Ma too, she lied. She didn’t tell Ma she felt safer with Uncle.

Ma’s voice was a fact: “You know this is a special time, we don’t have a choice. D.D. doesn’t have a choice. We have to wait for him. We have to wait for this to end.”

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 114

“Got everything?”

“Yeah.”

4 TINA GUO THE SKY IN THE WELL

She heard something about winter tires. D.D. didn’t change the winter tires. Ma never understood why he never did anything. She could not be more fed up with him. He had ruined her life.

She shut her laptop and tossed it into her backpack. She was about to slip out of the door when Ma caught her.

“I’m sorry this always happens,” said Ma. “It’s okay.”

“Aren’t you supposed to be in class?”

“Not anymore don’t worry see you later,” she managed in one breath.

Times like these always filled her with jittery energy, the kind that would cause an implosion if it wasn’t expelled immediately. She sprinted until she reached Uncle’s building.

The front door was propped open with a cardboard box. People were moving in. Ma told her once the price of housing was low enough, which was only a matter of time, she would buy a house for the two of them—a little one in some nearby town, but the best she could afford. “But don’t say anything to D.D. yet, okay?” So she had kept her mouth shut to speed up the process.

Uncle’s door was unlocked on the eighth floor. Today the place reeked of marijuana. He was indulgent but had made it a rule to stay clean when she was around. She didn’t mind. Anything was better than the sight of D.D. napping on the living room floor, leaking the acrid odor of a middle-aged man.

The bedroom door was half open. A brown body against the white wall. Uncle’s face flushed behind strands of wet hair. A slender hand wrapped around his neck. Red and purple down his chest. He was naked.

“Harder?” It was the GF’s voice. The knuckles paled. Her eyes drifted downwards to the thing between his legs. White lace. His thighs tensed. He let out a sound she had never heard before.

She tiptoed to the bathroom and shut the door as silently as she could. Her heart pounded like a fist against her ribcage. She felt like throwing up. In the mirror, her face was an overripe persimmon. There he was—writhing, defiled, in pain. If the pupil was a hole, would it hurt if she stuck a needle inside? White against tan skin. She wanted to stick a needle inside. She sat on the toilet and masturbated.

She saw him again when she was trying to read the assigned chapters of Hamlet on her corner of the coffee table. He came in a damp t-shirt and bloodshot eyes. The loose white collar draped below his neck. Red.

“Move, let me air this out.” He reached behind her to open the window. She tried not to flinch at the proximity between their flesh. A gust of air rushed in and he let out a loud sneeze.

“Aren’t you too young to be sneezing like that?”

“Like what?”

“Like a greasy old man with no self-respect.” “Thanks.” He picked up one of the sweaters from the couch and pulled it over his head.

“The GF finally got some time off. So we wanted to let loose for a bit.”

He tied up his hair in a lopsided ponytail. Some loose strands were still stuck to his nape.

“Where is she?” She glued her eyes to a tiny illustration of the King’s ghost; he was man-sized and looked pitiable.

“She’s still in the shower.”

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 115

5

He really had no idea.

“Have you had anything to eat yet?”

She shook her head.

“I have leftover pizza from yesterday. It’s not much but it’s something. You want some?” He scratched at the side of his arm until it turned pink.

She nodded. She was glad that he never asked why she showed up anymore. Uncle was like her real mother. Well, two sides of the same coin—one attracted and the other repelled. She remembered playing with two magnetic coins she had gotten from the corner store. On the tabletop, they seemed to perpetually pull, push, and spin around one another.

D.D. was dead. Offed himself, so to speak. The living room had been silent. Underneath the charcoal window was a row of pruned persimmons. D.D. bought them a month ago. They knew better than to touch anything of his.

She saw D.D. standing under the orange streetlight like an ant under a microscope. His brows furrowed as if he was reading something. Once he told her that black baby ants tasted like sesame seeds.

He would walk into oncoming traffic. A hitand-run. Tomorrow morning, she would hover above his body. The pale light would hit his face in a way that would make her think he wasn’t all that bad. Next to him, dead maple leaves would weather into orange confetti.

Then she and Ma would have to sell his sofa bed on Craigslist. They would have to wash the mattress with bleach. Gone with the color of his flesh, his sweat, Ma’s carrot cake between his teeth. The night mode of his cellphone when he decided to go for a walk.

She sobbed into her pillow until she heard keys in the front door. Orange lit up the living room. She got up to use the washroom but she couldn’t piss. On the other side of the hallway, a blanketed cocoon squirmed on the sofa bed. D.D. was back, filthy and alive.

“I thought you went out to kill yourself.” She used her small talk voice and kept her face blank. “Oh yeah? I love myself too much for that,” D.D. said to his phone. The sofa bed made an ugly creak when he turned to his side. Liar!

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 116

6 TINA GUO THE SKY IN THE WELL

He was making a small pile of paper when he noticed the golden rim around the warehouse. The sky was beginning to shed its skin. A newborn sun soon rose into view.

The orange sky was framed and contained like a nicely boxed gift. He picked up his first box, wrapped it, then set it on the conveyor belt. It would descend into a larger cardboard box that would be picked up by the forklift and dropped into the truck in the warehouse. But he had never seen any of that. He imagined tossing a small pebble into a river that rushed to join the ocean. By the time the box arrived at the store, whatever warmth left from his fingers would have evaporated. The box he touched and held and wrapped would be brand new.

He felt like a toad at the bottom of a well as he gazed out into the shapely world. That was a Chinese proverb his sister had taught him. The toad assumed the sky was only as big as the well opening and the ocean was like the well water. It called itself the ruler of the world and bossed the tadpoles and shrimps around. He remembered how he had thought, silly toad! Now he looked forward to seeing the sun

ascend and descend in and out of a gridded rectangle.

He did not know much about his sister growing up other than the fact that they looked alike, and that she was a bright person. She had been a linguistics professor at Shandong University before she became Ma. Once he asked her if she regretted coming to Canada. “My daughter gets to do what she likes here” was what she told him.

Niece wasn’t like her Ma at all. Had she eaten the fried eggs yet? Her breakfast was always cold when she woke up, though she never complained. With her mind in another country, she’ll be gone soon enough.

He thought about the names in the notebook underneath his bed. All thirty-two of them. Would the GF move out after the pandemic? She was tired of working eleven-hour shifts at Loblaws. He didn’t ask if she was tired of him as well. He didn’t know why he picked up Cat from some guy on Kijiji that Friday after work; why he so badly yearned for something to make a sound when he opened the door.

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 117

7

They sat around Ma’s bedroom with the hotpot in the center. Ma had moved it. D.D. was still in the living room. Ma locked her bedroom door and let the oil and spice permeate the air. It was Lunar New Year.

Ma chewed quietly. Uncle asked her to pass the sesame paste and she did. It was like nothing had happened. Ma scooped cabbage, fishballs, and tofu into her bowl until she made a mountain.

“Sorry,” Niece mumbled. Her snot dangled like the glass noodle from her mouth. “But I just couldn’t ignore him. Not after all the things he was saying about you.”

It had been a scene out of a Renaissance painting; more comedic than tragic. There was herself, D.D. against the wall, her nails in his neck, the white of her knuckles, the white of his eyes, the hotpot bubbling on the dining room table, Uncle and Ma looking. She didn’t know how much time passed before Uncle peeled her off. She saw D.D. shielded behind Ma’s body. D.D’s mouth opened and closed but nothing came out. I’ll hit you back for all the times you’ve hit me, She screamed. D.D. was shorter than she had remembered.

“I hate D.D.,” she picked up a fishball and shoved it in her mouth. She was going to use her facial muscles for eating.

“I know,” Ma broke into a smile. She had not smiled in a long time.

“If D.D. were dead we’d be able to buy a house,” she kept chewing because she couldn’t swallow.

No response. They were all sweating buckets. Ma tried to open the window but it was frozen.

“Why do you put up with him? Why didn’t you do anything? I hit D.D. so you wouldn’t have to! I strangled him.” Her hand felt strange. The chopsticks were too heavy.

“Stop that,” Uncle raised his voice. He passed Ma a tissue from the box. Ma wiped at the corner of her eyes and blew her nose.

“I strangled him for you to see,” she swallowed. It hurt the length of her esophagus.

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 118

8 TINA GUO THE SKY IN THE WELL

A blank field. They stood behind her middle school and looked down at the ravine.

“Is it okay to just not show up?”

“I called in. It’s really whatever. I mean, it’s a pandemic job so they get it. Your Ma wouldn’t want me to leave you alone like that.”

Niece nodded. She still didn’t explain what made her show up last night. He shivered at the nightmarish orbs above his face.

“You can talk to me, you know?”

He turned around to find her rolling a snowball several meters into the field so he scooped up some snow and began to roll as well. In another year, the hills would be crowded by children but now they were utterly alone. Like two dots: a colon. What a strange time to be anything.

He stacked his snowball on top of hers when it became the size of his head. Niece pulled a carrot out of her pocket and stuck it in.

“Where did you get that from?”

“Your fridge. I knew where we were going.” Niece took a few steps back, pleased with herself. She reached into the foliage and came out with two dead leaves. She slapped them on. Eyes.

“Wait.” He circled the snowman. “He’s missing something, don’t you think? Maybe another ball for a torso; or like, at least a neck.”

“A neck! What does he need that for?”

“Well.” He pretended to be deep in thought. “The neck is a bridge to the body. It connects the head to the heart, so it's important.”

“You think this thing has a brain and feelings?” She stabbed her foot into the snowman and let out a cry of agony. The snowman collapsed into a white mound.

He watched Niece jump up and down on its remains, her mouth stretched into a wide grin. Sometimes he imagined what it would be like to be a parent, to have a child. Would he become just like his sister? Later he helped her build three new snowmen. Like Ma and him and her, she announced.

“I’ll miss this when you’re in Michigan,” he said.

Sometimes he felt like a seashell waiting for a hermit crab. But the hermit crabs that lived inside him never stayed for long. Each hermit crab would eventually outgrow the hard shell, or they would wander off when they spotted a shinier, bigger one. Then they would leave him right there, empty and waiting, until the next hermit crab came along and carried him off somewhere.

The sky was warm and the snow glowed opal. The pines stretched into dark teeth on the ground. He asked her if she wanted to go home.

THE NEW NORMAL ON THE MARGINS 119

9

For Scarborough, In Scarborough.

120 COLOPHON

Editors

Sampreeth Rao Kevin Ramroop

Design

Shujaat Syed

Mentors

Masooma Ali Kahlil Hernandez Kevin Ramroop Natasha Ramoutar

Fellows

Mitul Shah Noor Gatih

Kyle Mopas Alicia Reid Anjali Chauhan Tina Guo Luxshie Vimaleswaran Mahdi Chowdhury

WaveArtCollective Team

Sampreeth Rao Amandeep Sandhu Kevin Ramroop Kahlil Hernandez Masooma Ali Raj Mann Natasha Ramoutar Deena Nina

Typefaces

Neue Haas Grotesk Times Now

Supporters

Scarborough Arts City of Toronto University of Toronto, Scarborough

Thank you to the Doris McCarthy Gallery's Ann MacDonald, Erin Peck, and Safia Said for supporting the presentation of the fellows' works.

Thank you to Riley McClimond for helping generate design concepts on a very short-notice.

Thank you to our parents who travelled across the sea, and the sky into the unknown so we could make a new home for ourselves.

Website: www.waveartcollective.ca Instagram: @waveartcollective Twitter: @waveartcollective

Printed in Canada by Flash Reproductions

Copyright © 2022 WaveArt Collective

121

WaveArt Collective