IRIS

WelcometoIris!

Welcome to Iris, the WGGS Classics newsle er. Our aim is to shed a li le light on the ancient world, and on the wide and diverse range of topics we encounter in our study of La n and Classical Civilisa on.

In this issue, we are celebra ng achievements of some of our students who took part in the annual joint Classics essay compe on, held between WGGS and WBGS over the summer holidays. Students in Years 10 and 11 had a choice of 4 essay tles to research and write, with the winners winning a book token each. The overall winner was Henry from WBGS. Maya from WGGS was highly commended, and her excellent essay is featured here. We will share some of the other entries in this issue and the next. Well done to all the par cipants! We hope you enjoy reading their efforts.

Also in this issue, Rachel in Year 12 reviews our recent visit from Dr Antony Makrinos, an Associate Professor in Classics at UCL, who spoke to the Senior Classics Society on Homer in film. Claudia in Year 11 discusses the lives of women in ancient Greece, and several Year 8 and 9 students share their poems inspired by the works of Sappho, a project they worked on last year in Junior Classics Society.

If you would like to contribute to the next edi on of Iris, please email your idea to: h.long@wa ordgirls.herts.sch.uk . We would love for you to be involved and for your voices to be heard!

Ms Long

Do museums have a responsibility to decolonise their exhibi ons? - Maya, Year 11 (Essay Compeon Winner Highly Commended)

Most museums, especially those in Western-European countries which once had significant empires, are home to artefacts that were stolen, raided and taken as ‘spoils of war’ from their colonies. The ‘Scramble for Africa’ (the rapid invasion, conquest, and colonisaon of the African con nent by European powers) meant that many artefacts such as the Benin bronzes, the Asante gold regalia and the Ife Heads were looted from their homes in palaces and official buildings. This le the Bri sh Museum and other museums around the world with massive African exhibi ons which were created as the transatlan c slave trade began in the early 18th century.

Insidethisissue

Do museums have a responsibility to decolonise their exhibi ons? - Maya, Year 11

To what extent did the Greeks and Romans use mythology to explain the real world? - Marley, Year 11

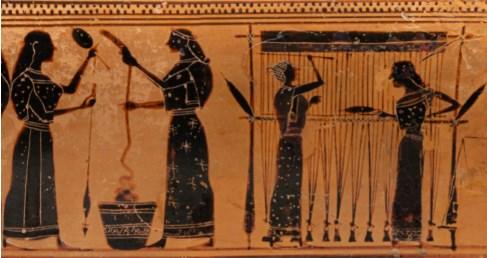

A Woman’s Life in Ancient Greece Claudia, year 11

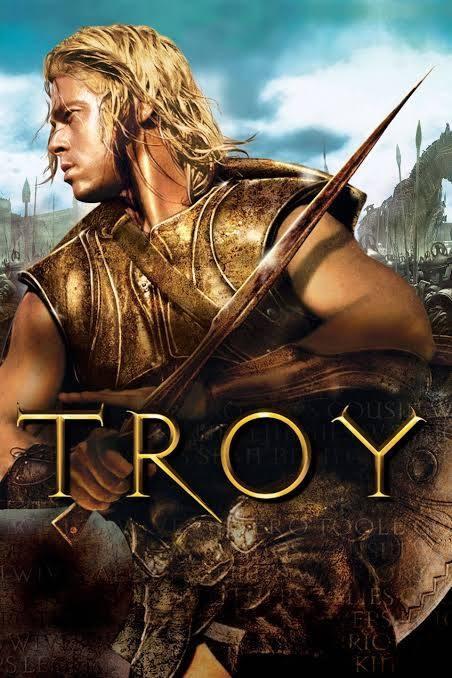

Homer in Film Rachel, Year 12

Junior Classics Society Presents: Sappho inspired poems (Year 8 and 9)

In 1897, a group of Bri sh officials visited Benin tried to depose the Oba (King), although they claimed that they merely wanted to open up trade. The people of Benin had been forewarned of the true inten ons of the Bri sh and Benin soldiers ambushed the group. The Bri sh retaliated, by sending over a thousand soldiers to invade Benin. They burned Edo City, executed men in the streets and looted the Oba’s palace. The Benin Bronzes that were housed in the palace, were taken a er the invasion. The Benin Bronzes are a group of sculptures made of brass and bronze which were created in the 1500s. They are a collec on of commemora ve heads, animal figures, and items of royal regalia now on display in the Bri sh Museum. The occupa on of Benin City saw widespread destruc on and pillage by Bri sh forces. Along with other buildings, the Oba's palace was burned and its shrines looted by Bri sh forces, with thousands of objects of ceremonial and ritual value taken to the UK as official 'spoils of war'. The museum worries that the artefacts, if given to Nigeria would end up in a private collec on belonging to HRM Oba Eware II – this would mean that having the artefacts in Nigeria would not actually benefit the people of Benin City, as they wouldn’t see the artefacts at all. The artefacts would not be exhibited in a public se ng like the Bri sh Museum. I believe that this is a valid reason for keeping such artefacts, as having them in the Bri sh Museum, which is free to enter, means the Benin Bronzes are readily accessible for anyone wan ng to access them for educa on, informa on, or study.

Like the Benin Bronzes the Elgin Marbles are also a collec on of artefacts in which ownership is disputed. The Elgin Marbles, also called the Parthenon sculptures, are a collec on of marble metopes, friezes and pediments from the Parthenon (Temple of Athena) on the Acropolis in Athens. They are now in the Bri sh Museum. Lord Elgin, the Bri sh Ambassador to the O oman Empire in the 19thcentury, pe oned O oman authori es to draw, measure and remove the figures. Between 1801 and 1805, Elgin removed over half of the sculptures from the Parthenon. As the Bri sh government purchased the marbles from Lord Elgin in 1816, and his acquision was deemed legal, the House of Commons refuses to return the sculptures to the Acropolis Museum, as they claim Britain owns them. The museum also believes that returning the marbles could trigger similar demands from other countries, poten ally deple ng further collec ons. This suggests that the Bri sh Museum feels that they don’t have a responsibility to decolonialise their exhibi ons especially if permission was granted to remove the artefacts in the first place. However, did the Greeks of Athens give permission for their sculptures to be moved or was it their colonisers the O omans? And if that permission was given 200 years ago, when the real worth of the sculptures in historical significance and explaining Ancient Greek myth, history and religion wasn’t known, is it right for us to have a legal claim on artefacts that don’t have a significance to our Bri sh history? And unlike the Benin Bronzes there isn’t a possibility of the Parthenon sculptures ending up in a private collec on. The sculptures would be displayed in the Acropolis Museum which has 4.5 million visitors visi ng a year, so although we have more people visi ng the Bri sh Museum (6.4 million) these artefacts would s ll be seen. This would a ract more visitors to the site of the Parthenon, increasing the site in historic importance and a rac on as it would be complete instead of missing fundamental parts of its value to the Ancient Greek religion.

The Bri sh Museum displays only 1% of its vast collec on. Approximately 80,000 objects are on public display at any given me, but the vast majority of the collec on is held in secure storage. If we believe that artefacts would not be seen if we gave them back, well lots of artefacts that we took from other countries are si ng in storage gathering dust. They are unseen and that is because our empire stripped colonies of ar facts and culture under the colonist guise of preserva on. It is important that people in Athens can see the Elgin marbles, that their ancestors might have built, and to see the temple complete where their ancestors once worshipped. That the people from Asante can see the jewellery their people once wore. We should give them back, because we have our own

history: the Celts, the Saxons, the Vikings, the Romans. Our country is rich in its own artefacts, why do we have to steal other peoples? Even if we can’t legally or poli cally give artefacts away, we should set up global tours of artefacts, where objects travel the world visi ng museums and ci es, educa ng millions, showing people their history, otherwise those artefacts sit in dust, 8million of them that only a miniscule percentage of staff at the Bri sh Museum will ever see, let alone the whole world.

Furthermore, as a place holding so many artefacts not all of which are catalogued, several items over the years have been stolen in the Bri sh museum. The museum has announced that up to 2,000 items had gone missing, many of which were stolen from its storerooms and sold on eBay and allegedly by the former curator of Mediterranean art, Peter Higgs. One of the reasons for previously not returning artefacts, is the idea that the Bri sh Museum was the safest place for them, which in itself is a patronizing colonialist mentality, and had the best resources to curate, restore and protect artefacts. But if whole collec ons are going missing, unno ced, as there are too many artefacts to keep track of, are we really giving other countries’ artefacts our duty of care. Wouldn’t they be less likely to be stolen in smaller museums that are less likely to be targeted by art thieves?

The government claims that they cannot repatriate artefacts as giving them way would be breaking‘The Bri sh Museum Act of 1963’ which s pulates that: ‘The Trustees of the Bri sh Museum may sell, exchange’ artefacts if ‘it can be disposed of without detriment to the interests of students: Provided that where an object has become vested in the Trustees by virtue of a gi or bequest’. As many artefacts were part of private collec ons and donated or sold to the Bri sh Museum (therefore gi s) it’s hard for the Museum to find a loophole in this law as it means that they can’t repatriate artefacts as its technically illegal. This is one the Bri sh Museums arguments for not returning artefacts such as the Elgin Marbles, the Benin Bronzes and other disputed collec ons. However, this is an outdated law made when our Empire was beginning to collapse, it was a law made by the powerful to cling on to artefacts as our control slipped.

We are not an Empire anymore; we need to acknowledge that we no longer have the power of an Empire. We need to redress the immorality that enabled our ancestors to strip places of culture, history and iden ty. Without these artefacts, countries are missing the founda ons of their culture and history, which are important influences for modern society.

If the artefacts are in danger of being destroyed or being put in private collec ons, then yes, we have a responsibility topreserve these artefacts and keep them safe for future genera ons. However, even though the Bri sh Museum is a global repository for interna onal artefacts allowing people to see artefacts easily and for free, isn’t it more important that these artefacts lie where they were once made, used and loved – where they belong? We need to change our laws and allows artefacts to travel the world so they can be seen by more than the 6 million people who visit the Bri sh Museum. We have a responsibility to subvert the colonialist powers that not that long ago allowed us to even have a claim to any artefact that was found in our past colonies.

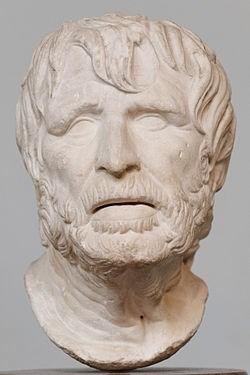

To what extent did Greeks and Romans use mythology to explain the real world? - Marley,

Year 11 (Essay Compe

on entry)

From seasonal changes of weather and environment to rulers and the rise or collapse of their empires Ancient Greeks and Roman’s turned to mythology in order to explain and understand what was happening around them. When modern technology, science and general literacy across popula ons was unobtainable myths weren’t simply stories, but instead key ideologies deeply embedded in the people's culture, religion, and intellectual lives as individuals in these civilisa ons. Before modern science mythologywas the only way people could interpret things like the forces of nature, the complexity of human behaviour, such as the dis nguishment between good and evil deeds, as well as the structure of society and were everyone must fit. For most people today, mythology is symbolic of the Roman and Greek empires but also widely interpreted as fic onal fables of gods and monsters, however for the Greeks and Romans it was something much deeper. Mythology was used by both cultures to explain their world however there were limita ons to this such as philosophical and scien fic ideas. By showing mythology’s role from the origins of the universe to how it influenced history and poli cs today as a society we can understand the las ng impact mythology had during ancient mes and how it may have changed history and the way we see our world today.

Since the beginning of me humans have always been fascinated with the origins of the universe and where we came from. Many theories and stories have been made across me using things like sun and moon cycles to decode the crea on of our solar system, however Greek and Roman mythology takes a different approach using gods and making them into the various parts of the observable sky. For the Greeks the epic poem, Hesiod’s Theogony outlines this. The poem talks about Chaos, the void which can represent space, which gave birth to Gaia, the Earth, as well as Uranus, the Sky, and numerous other dei es that made up the world they could see around them. These stories tried to understand where the Earth came from and what caused the changes of day in addi on to different elements present as how can something understand its home fully if it does not know how it was created.

The Romans, influenced by the Greeks made similar stories however to suit their strong empirical values as a society used an imperial spin on these myths. Ovid’s Metamorphosis begins with the account of how the world was created like Hesiod but highlight's themes of transforma on and order, key themes in Roman ideology.

Both cultures, in this instance, used mythology as a pre-scien fic explana on to the phenomena of space and the solar system. Without any tools of modern astrophysics or astronomy these stories offered structure and meaning to something widely unknown and unpredictable allowing people to feel safer and promote order at a me when no one truly understood what the origins of the universe were, a debated topic even today. Key beliefs in gods like Helios, Apollo and Zeus were used to explain mysteries like the movements of the sun during the day and thunder or lightning during a storm, observable yet unfathomable natural occurrences in the lives of Greeks and Romans. Mythology took these strange concepts and told stories in an accessible way to quell fears in society.

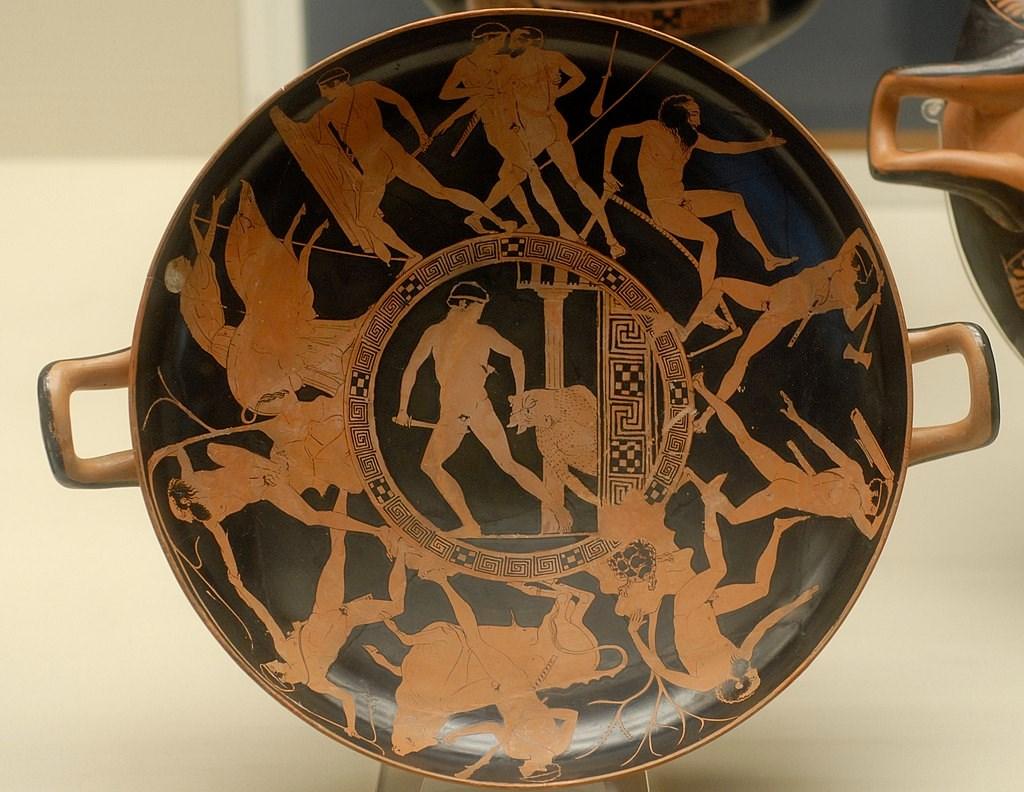

Beyond the origins of the universe mythology was also used to determine immediate aspects of the natural world and the environment on Earth. The Greeks and Romans saw a divine or mythological cause behind everything that they could see from weather pa erns to natural disasters. The change of seasons, a natural ac on which many think nothing of in modern mes but in theera of Greeks and Romans was perplexing. Instead, the occurrence is explained through the myth of Demeter and Persephone. Persephone had an annual descent into the Underworld due to her abduc on by Hades which caused Demeter, goddess of agriculture, to become so depressed at her absence that she physically changed the season with her grief making it winter. However, every me Persephone was released Demeter became so elated that it marked the start of spring a me of renewed fer lity for the crops. The cyclical tale provides a narra ve for the changes of the seasons but also reinforced the importance of agriculture and cropsinto Greek life.

Volcanoes and earthquakes were a ributed to gods being angry or upset with mortals and wan ng to punish them or monsters being imprisoned by gods and the power of the conflict between them causing these events to be set off. The frequent erup ons of Mount Etna, a volcano on the east coast of Sicily were believed to be the result of the evil monster Typhon being trapped beneath the mountain by Zeus. Similarly, Poseidon, god of the sea, was labelled‘earth-shaker’ and blamed for earthquakes. These myths gave an explana on for the frightening and erra c natural forces, even if these myths made li le sense.

Romans integrated natural events into the religious and mythological framework of their culture. They associated events likecomets and eclipses with divine interven ons as well as good or bad omens. These beliefs influenced poli cal and militant decisions, for example before beginning a campaign military leaders would visit oracles such as the Oracle of Zeus at Olympia to ask for guidance and receive favourable omens. This shows how mythology permeated all aspects of public life for Greeks and Romans.

Greek and Roman myths were not only used to decipher the environmental aspects of life but inevitably the ac ons and emo ons of people exploring human nature and moral behaviours. The gods o en embodied human traits- love jealousy, pride and revenge, offering models of how to live a morally correct life. In addi on to this cau onary tales were made to show what happens ifhumans do not do what is being told is morally correct. Mythology was for the people of this me, a mirror of human psychology likemost religions throughout history and in modern mes could be debated to symbolise.

Prominent myths such as the story of Icarus, show this warning system used to frighten humans into doing good much like with the ideologies of heaven and hell in a modern religious context. Icarus a young man, made wings out of feathers and wax to escape the island of Crete. His father warned him to not fly too high to too low, but Icarus did not listen and flew so close to the sun that the wax in his wings melted and caused him to fall into the sea and drown. Icarus’ hubris c nature leads to his downfall which could have connota ons of wan ng too much leads to a great fall, or hell, highligh ng that greed results in punishment. Having an overreaching ambi on or ego leads to an un mely demise as it is not a redeeming quality as humans know it is morally unjust Similarly, the tragedy of Oedipus explored the themes of fate, guilt and iden ty. This creates a controlling narra ve for people that fate and des ny cannot be changed perhaps showing that no human truly has free will- a fear tac c to control the civilians in these empires forcing them to believe that no ma er what ac ons they commit in their lives des ny will always have dominion over them.

Roman myths emphasise being moral and virtuous fi ng what they believed to be a good leader. The story of Romulus and Remus, the founders of Rome give people an inspira onal story of sacrifice, conflict and divine des ny. The Aeneid by Virgil a literary epic reimagines earlier myths and turned the stories into Augustan propaganda emphasising duty as well as the greatness of Rome highligh ng the poten al for mass control simply through stories created like mythology.

In both cultures myths reinforce societal expecta ons and values rewarding heroes for bravery and loyalty whilst those who went against the gods were seen as corrupt going against the natural order that society considered correct and were punished. These stories shaped people being ins lled as early as childhood so that indoctrina on into a society that doesn’t necessarily tell the truth but will be believed to be correct by its people no ma er what can be created perhaps being a key reason why these empires had so much power over so many.

However, Greeks and Romans did not use mythology to only explain the world around them but also the world their ancestors lived in also. Exploring history and the origins of na ons, ci es and customs in addi on to legi mising power was all done through mythology rather than relying on historical records allowing people to claim to be ancestrally linked to heroes or even gods. For the Greeks, the Trojan war was not just a story, but they believed it to be a true historical event. Ci es of people claimed to be descendants of heroes like Heracles and Theseus to legi mise status and have a pres gious public image. Romans did this also sta ng that Aeneas was the progenitor of the Roman people offering a disguise of divine jus fica on for colonisa on over the course of history. Myths about origin exploited cultural dominance over na ons as status and bloodline were considered par cularly important, however also created a sense of who people were des ned to become allowing iden es to be validated or rejected controlling the social hierarchy of the empires.

As me passed progress happened. Transi ons to ra onal thinking and science began from 500 BC onwards. Greek philosophers began offering alterna ve explana ons for natural and social events leading to reason and logic. However surprisingly mythology did not die out but instead was integrated into these new ideologies similarly to how religion and science coexistence and somemes overlap in modern mes.

To conclude, Greek and Roman mythology was far more than a collec on of stories but a comprehensive system through which na ons of people interpreted the world around them from the origins of the universe to human psychology, mythology resonated deeply with the people surrounded by its effects on culture in everyday life. While mythology eventually gave way to philosophical and scien fic ideas it never truly le ancient society and is s ll used in modern mes today inspiring literature, art and many different beliefs. Greeks and Romans used mythology extensively as a controlling mechanism in their society but also a way to create narra ves to help them navigate through a world widely unknown. In doing so they laid the founda on of religion and sciencefor us to use today, a cultural legacy that will never be forgo en.