Burden

and Expectations of Women in Japan

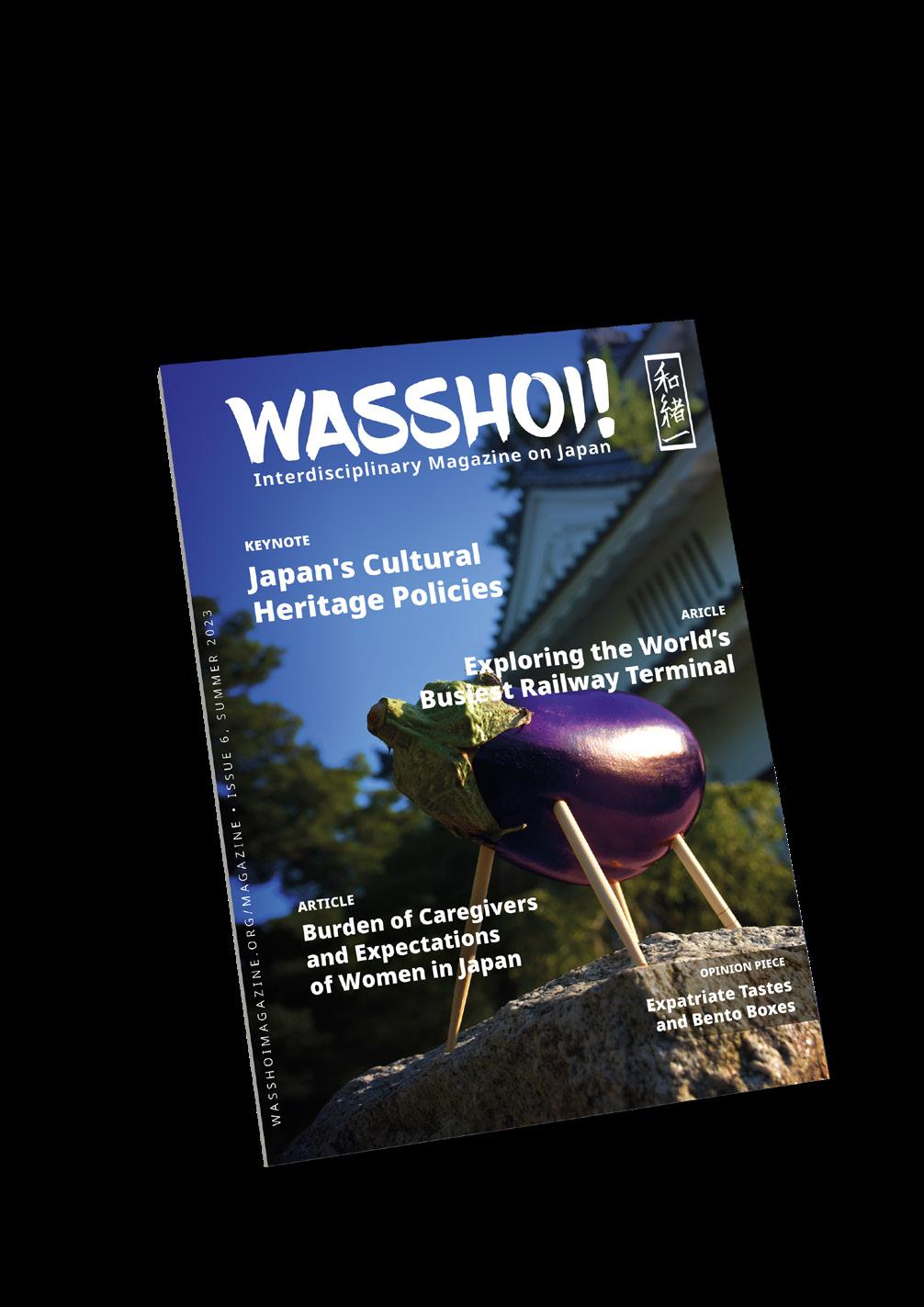

ARICLE WASSHOIMAGAZINE.ORG/MAGAZINE • ISSUE 6, SUMMER 2023

the World’s Busiest Railway Terminal

WASSHOI! Interdisciplinary Magazine on Japan KEYNOTE Japan's Cultural Heritage Policies

Exploring

ARTICLE OPINION PIECE Expatriate Tastes and Bento Boxes

of Caregivers

Obon Festivities and the Aubergine Offering

Marty Borsotti

Japan as a Pioneer in Intangible Heritage Policies

Alice Balle

The Burden of Caregiving and the Historically Rooted Expectations of Women in Japan

Samira Hüsler

Multi-Layered and Hidden Meanings: Hosoda Eishi and the Tales of Ise

Momoka Asano

HISTORY

Kanji: It’s Not That Bad

Dominique Jenkins

FILM

BILINGUAL / REVIEW

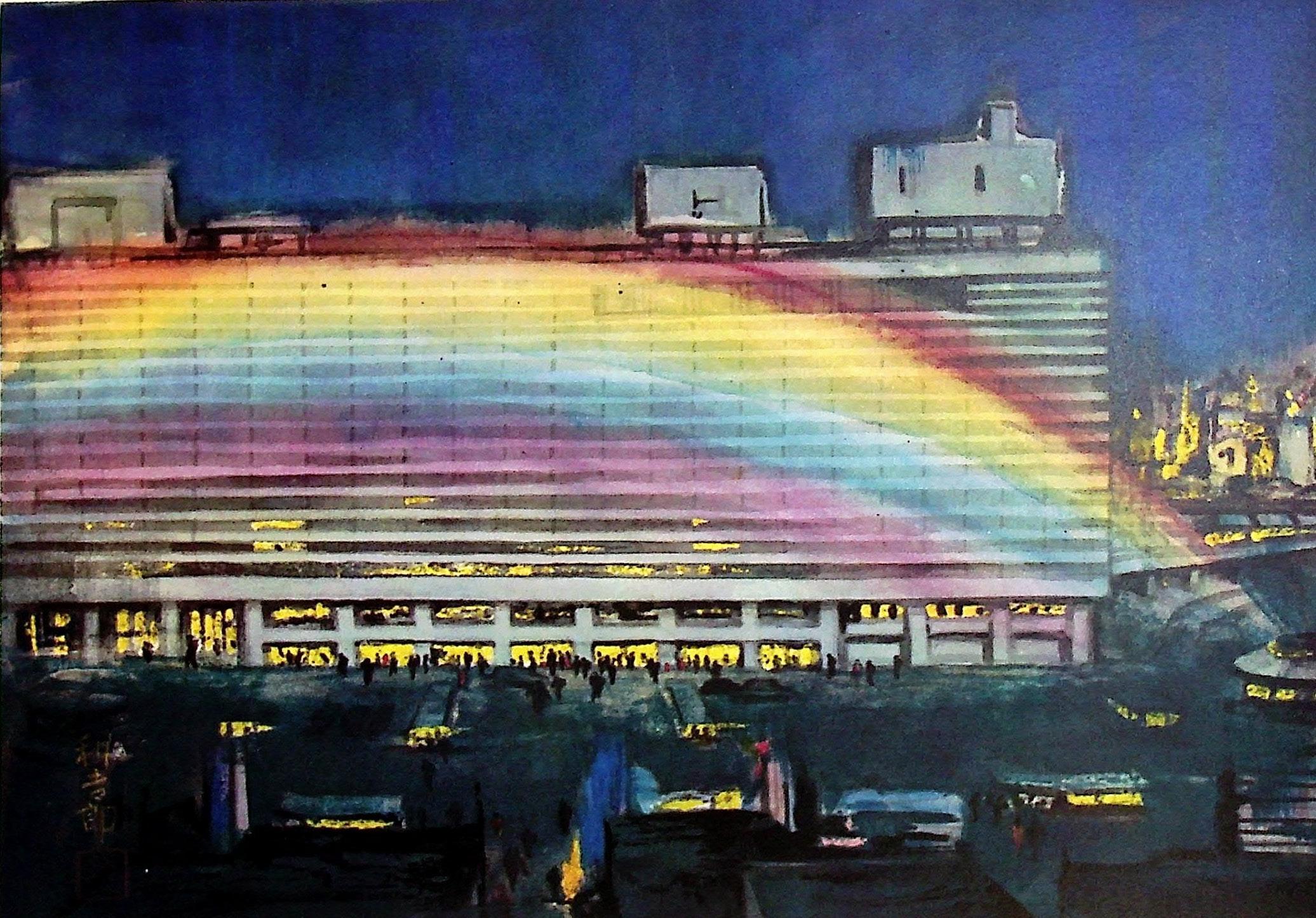

Ricchezza riflessa: Nippon Connection 2023

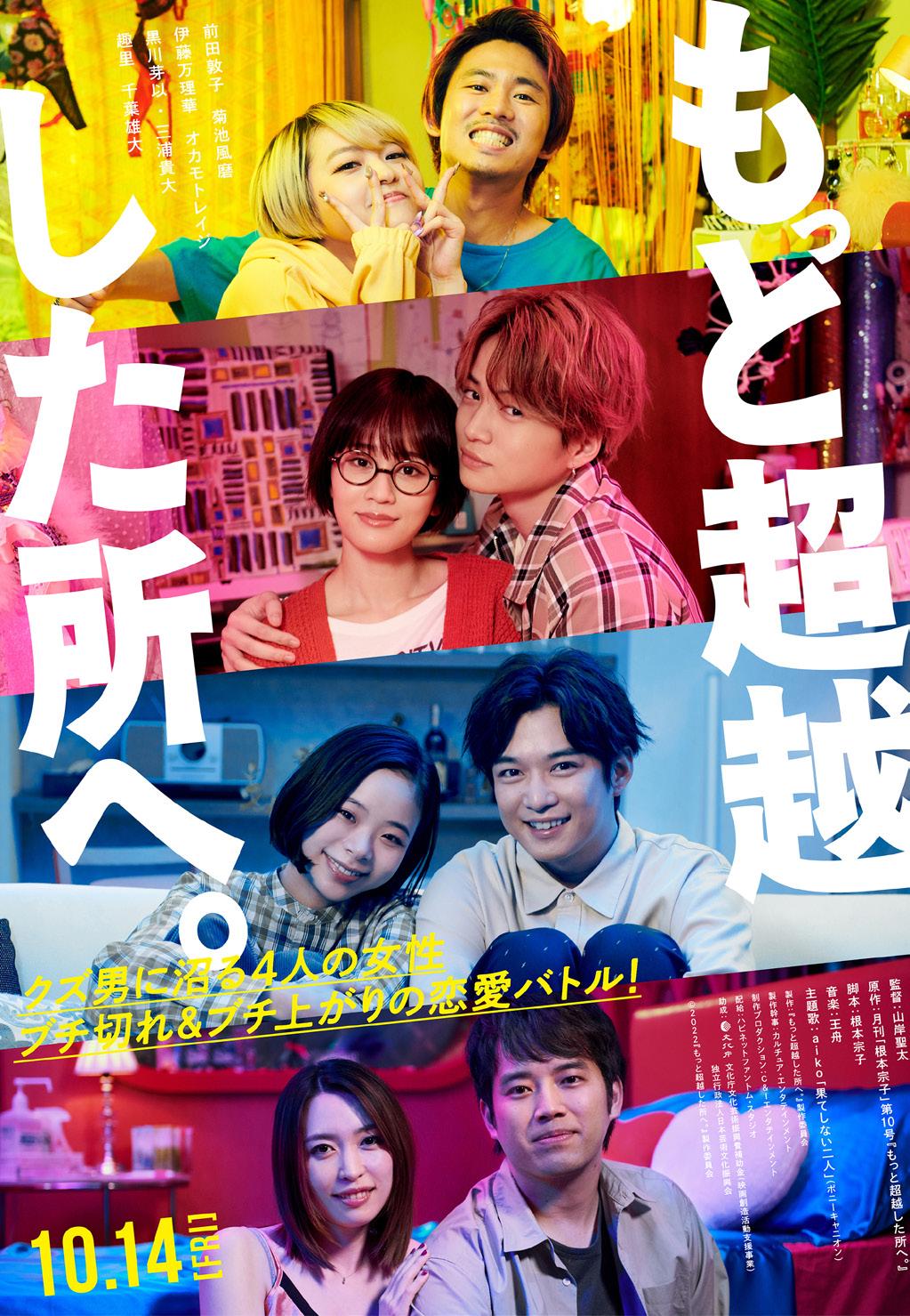

e To the SUPREME!

Mirrored Richness: Nippon Connection 2023

and To the SUPREME!

Christian Esposito in collaboration with Nippon Connection (Transl. Dœlma Goldhorn)

ESSAY TABLE OF CONTENTS 8 6 24 60 38 4 POLITICS ANTHROPOLOGY ARTS EDITORIAL

ARTS / HISTORY / KEYNOTE SOCIOLOGY / HISTORY HISTORY / LITERATURE 48 EDUCATION

Guten Appetit!:

僑居他 鄉 的日本美味

Fengyu Wang

Guten Appetit!:

The Expatriate Tastes of Japan

POPULAR CULTURE / ECONOMICS

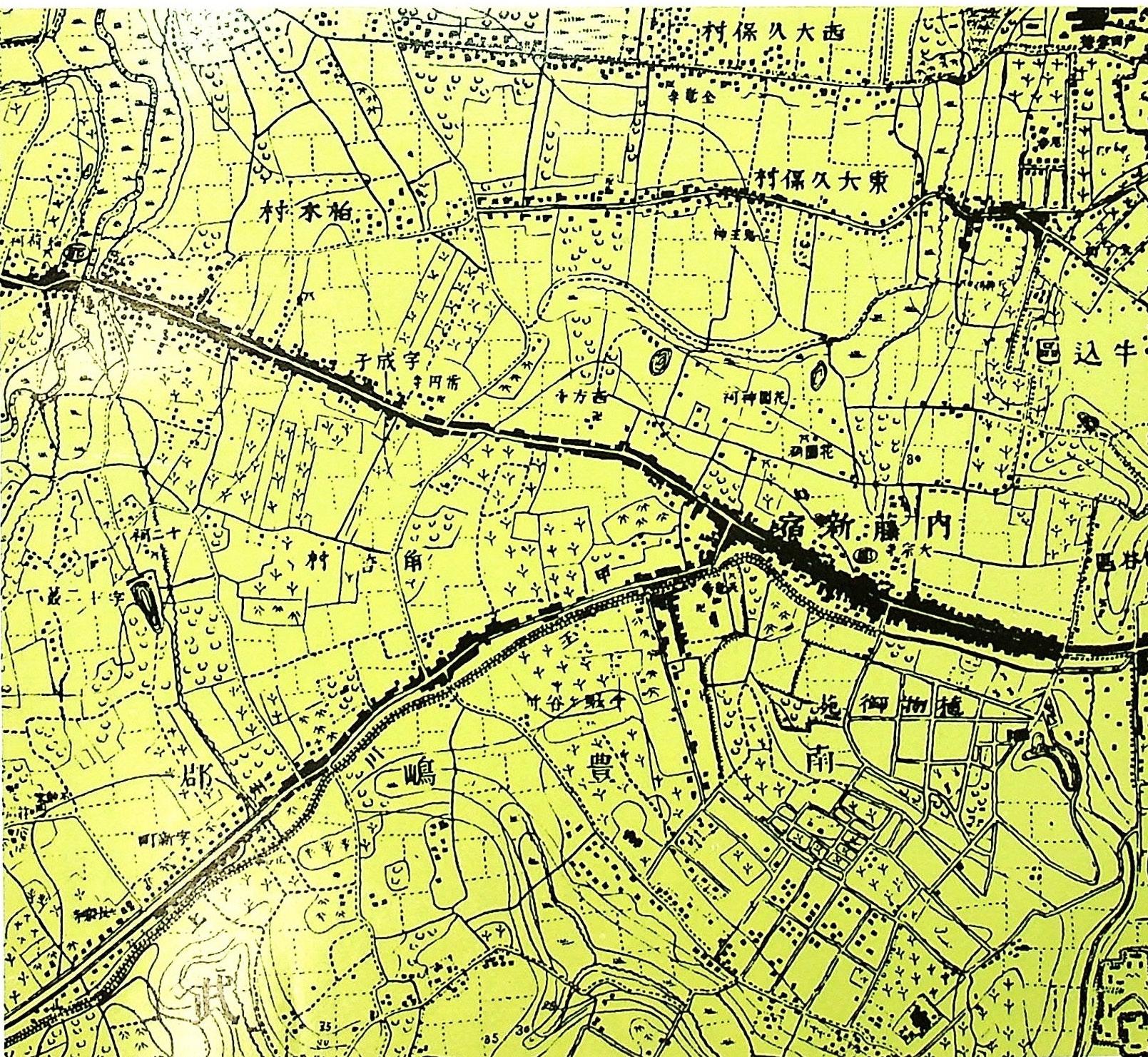

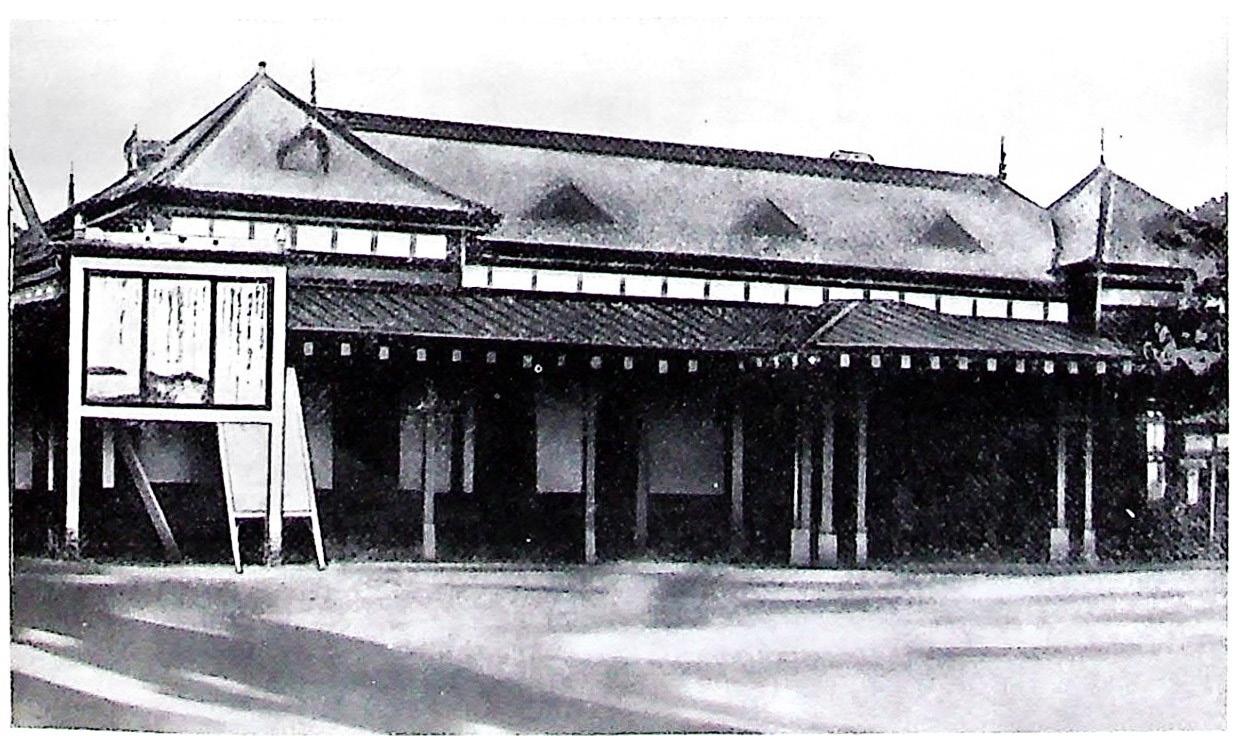

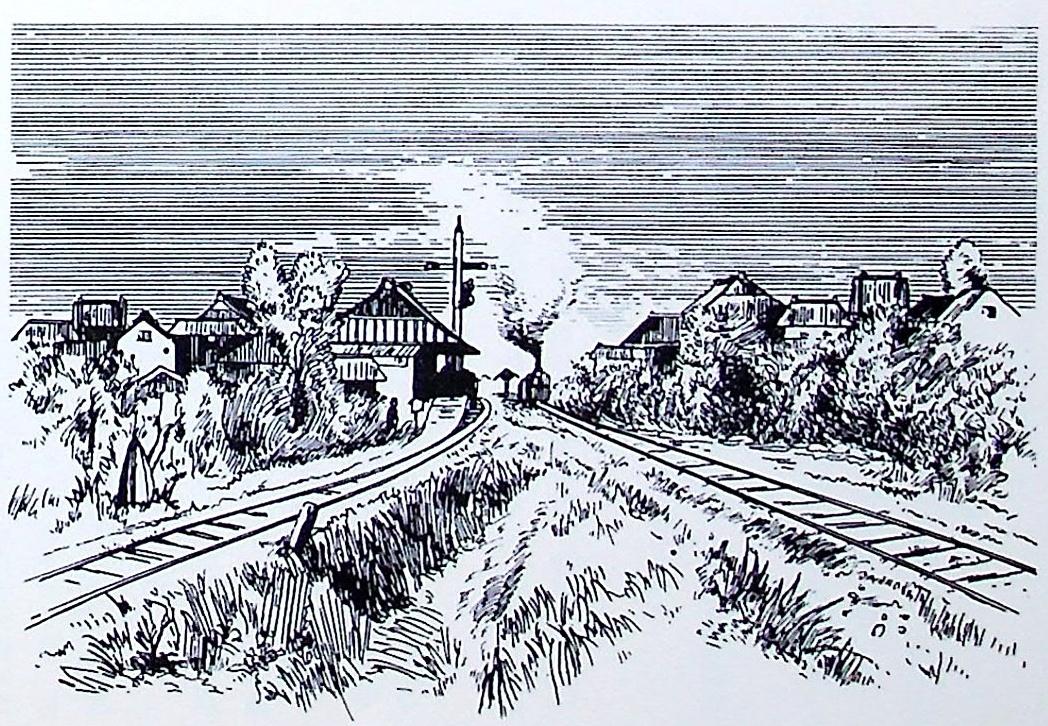

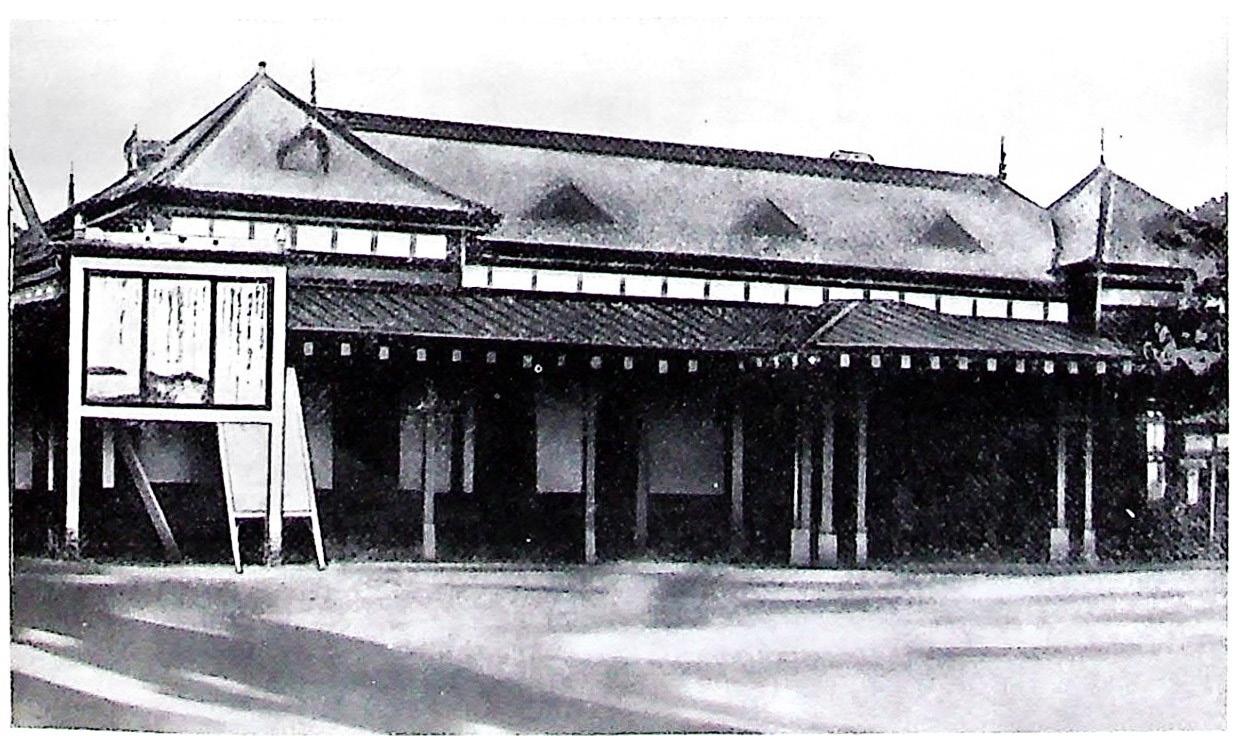

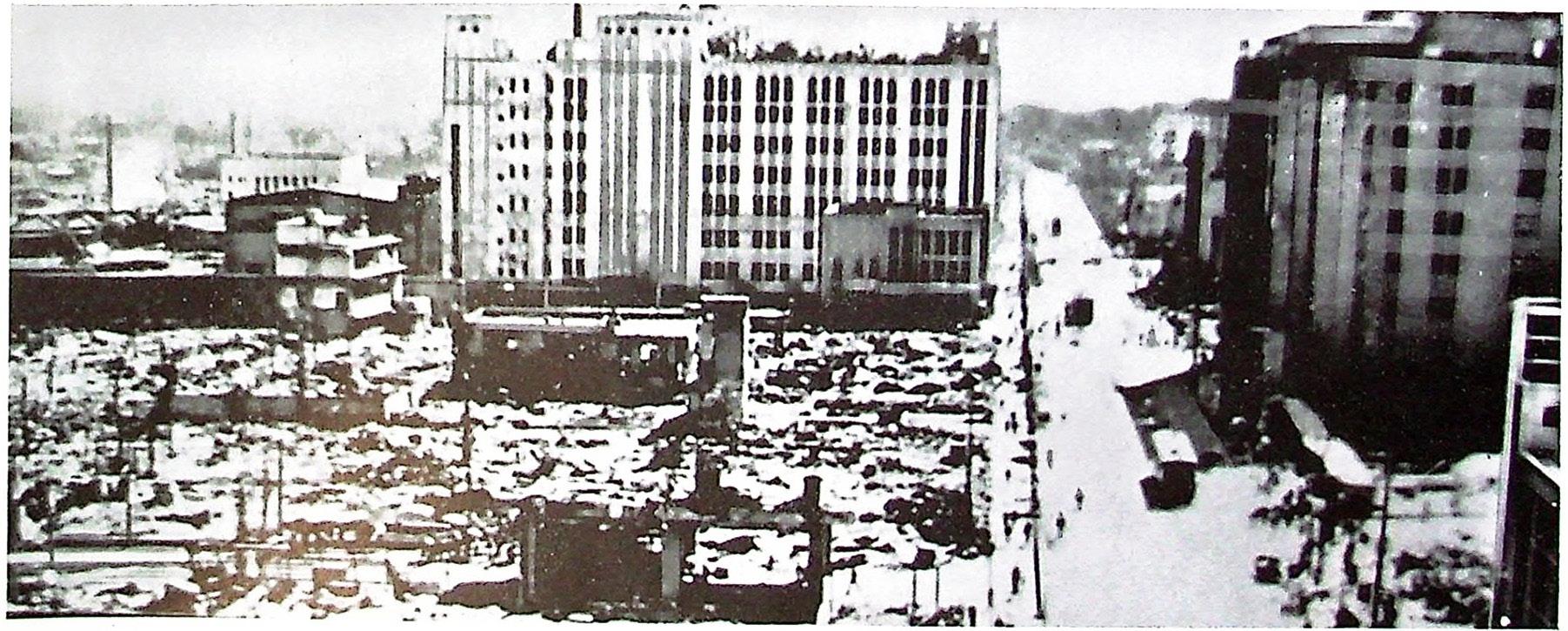

Shinjuku Station: An Historical Guide to the World’s Busiest Railway Terminal

Brian Rogers

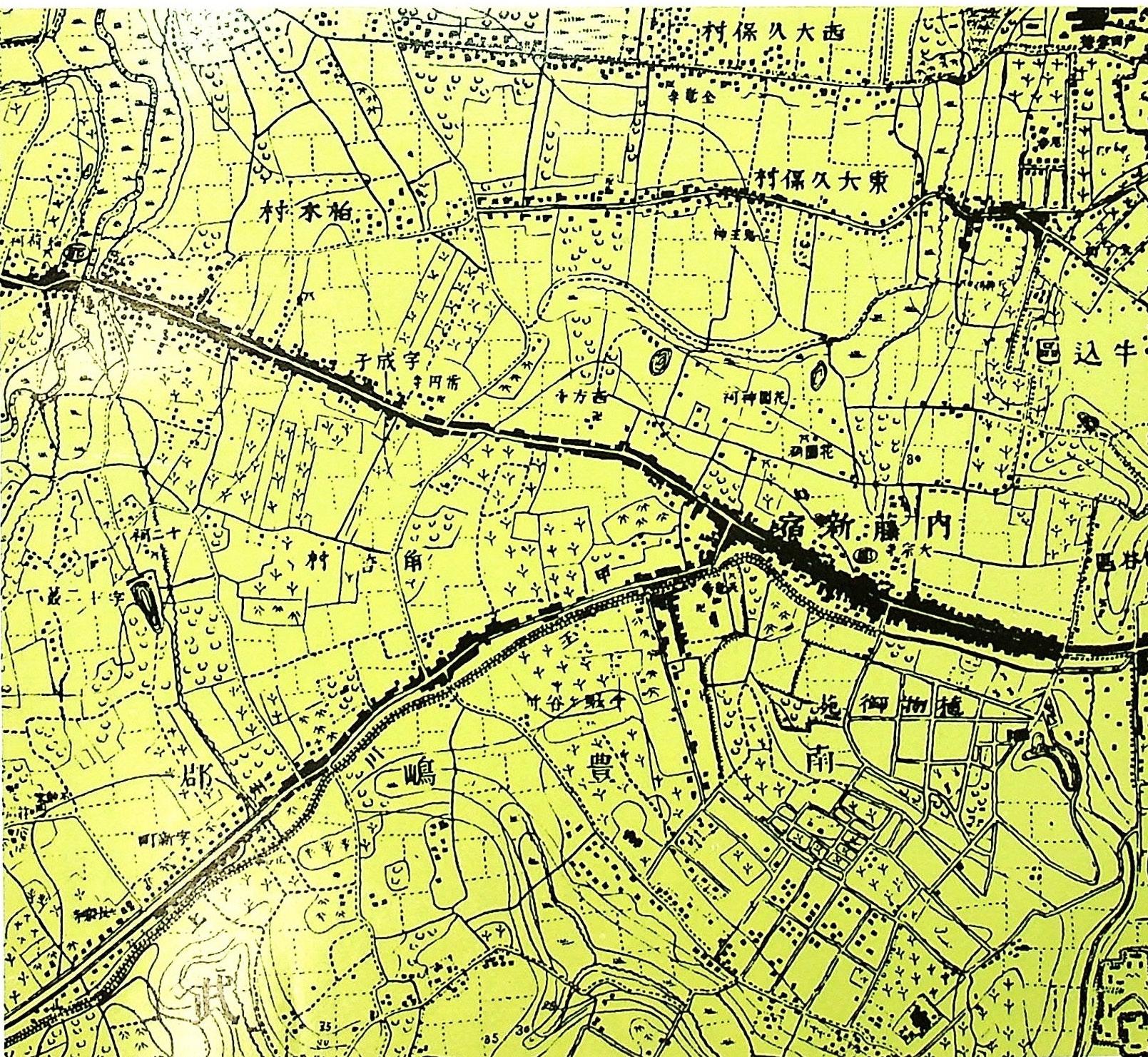

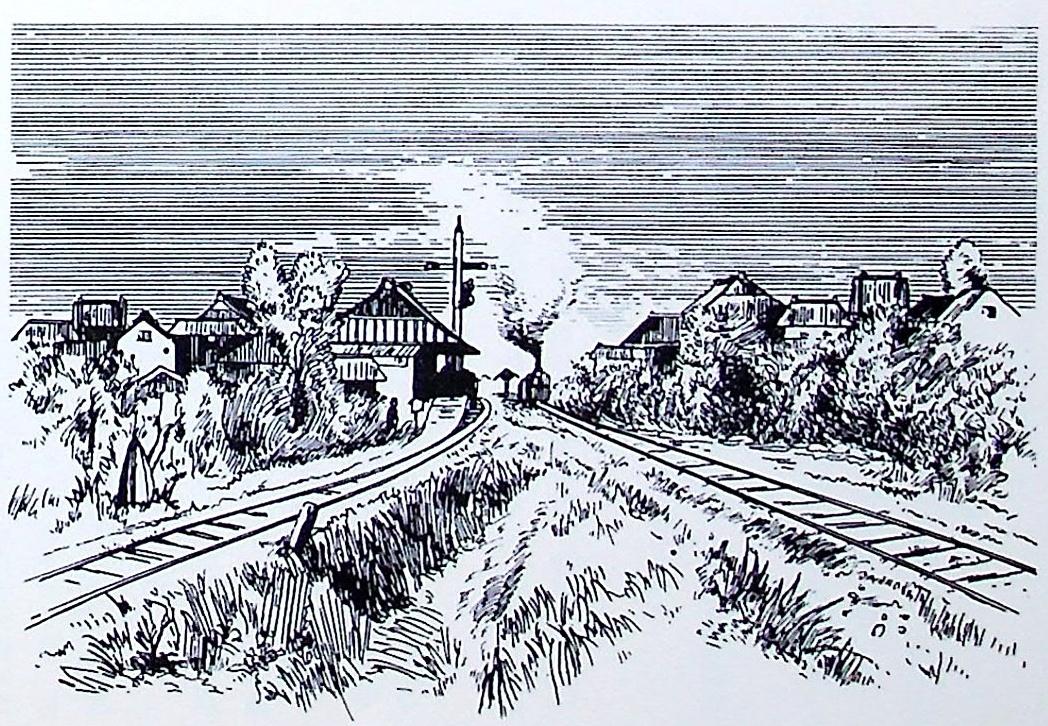

Transportation and the Castle Town in the Mōri Clan Domain Under Toyotomi Hideyoshi – Second Part

Hiroki Nakahara

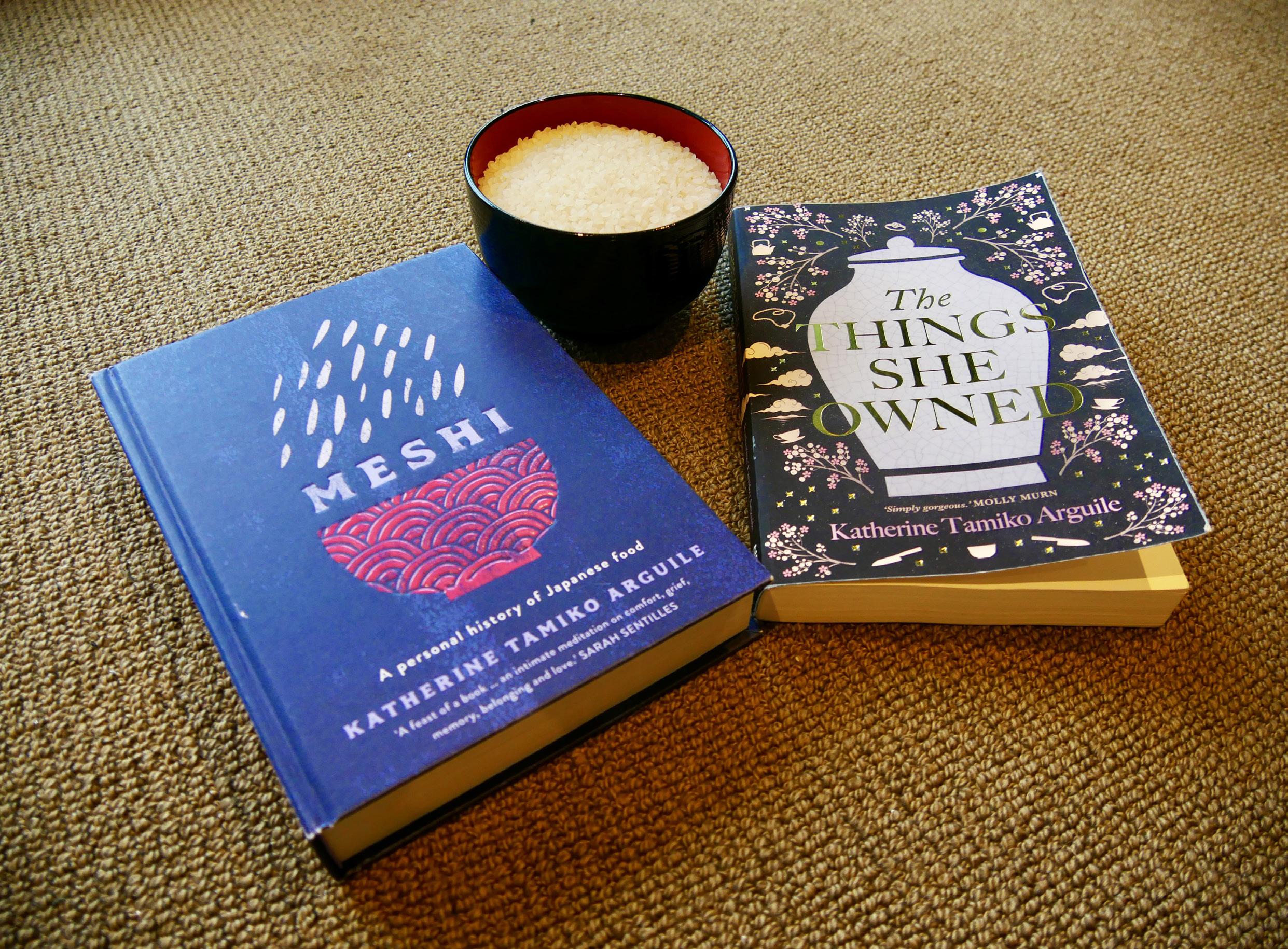

The Things She Owned (2018) and Meshi (2022) by Katherine Tamiko Arguile

Olivia Chollet

Umehara Daigo: The Michael Jordan of Competitive Gaming

Feyyaz Temür

SPORT 70 82 96 108 FOOD CULTURE HISTORY HISTORY LITERATURE

POPULAR CULTURE REVIEW

/ OPINION PIECE 104

BILINGUAL

Konnichiwa dear readers! Summer is here. Three years have passed since we founded Wasshoi! and what a ride it has been. Since our last publication, Japan has finally reopened its borders, but before your departure, allow us to present you the sixth issue of the magazine, which may keep you company during your flights!

The issue opens with a keynote article by Alice Balle, scientific director at the Japanese company Tsunagaru. In her piece she introduces to us the evolution of Japanese laws on cultural heritage and its various categories, with particular attention paid to the Japanese concept of Intangible Heritage. Samira Hüsler takes the baton and continues her series of articles on Japan’s aging society. She will present a brief history of women in Japan and the many social expectations that have burdened them. Following this, Momoka Asano guides

us into the world of ukiyo-e woodblock prints with an article dedicated to the visual representation of the legendary Tales of Ise by the artist Hosoda Eishi (1756‒1829). In a different tone, Dominique Jenkins presents some lesser-known facts about kanji, the Chinese characters through which the Japanese language is written.

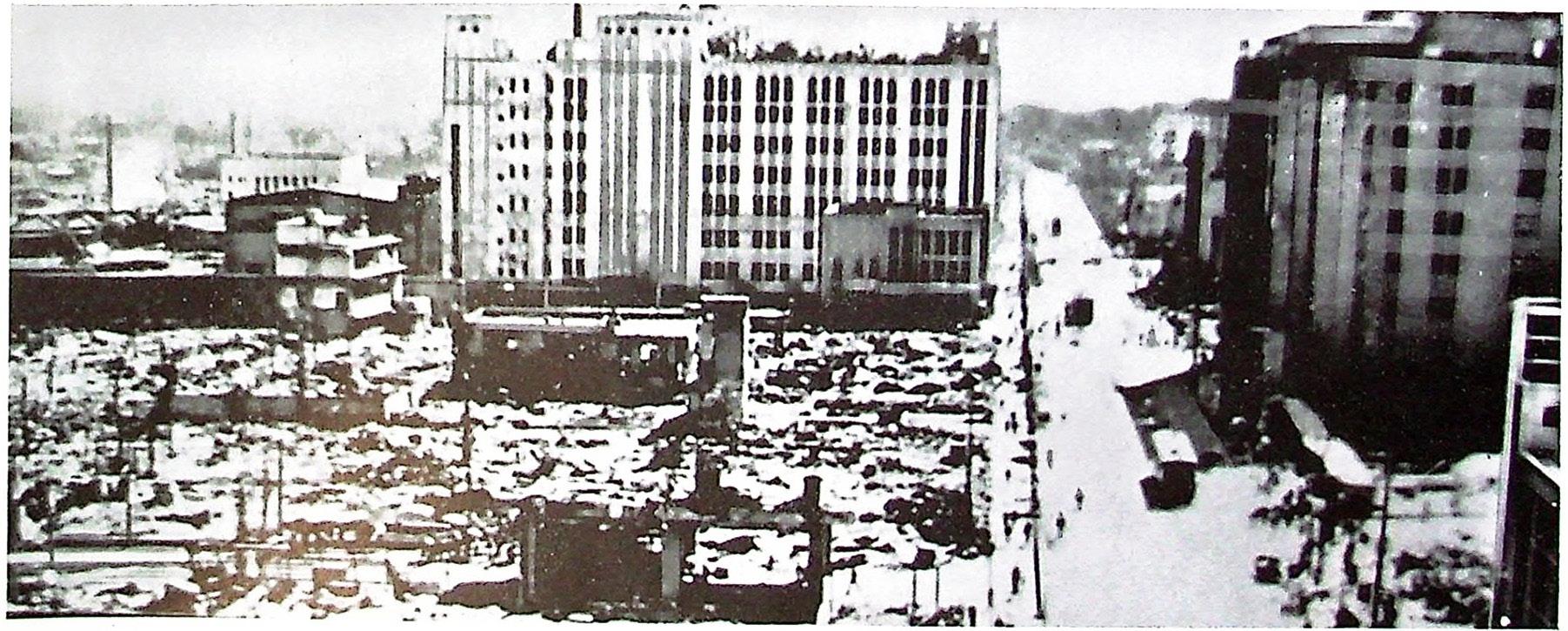

A well-deserved lunch break is offered to us by Fengyu, with an intimate bilingual opinion piece about the delight of eating authentic bento lunch boxes, sold at the Bergheim Campus of Heidelberg University. It is the first time that Wasshoi! has included an article in Chinese! A packed lunch will come in handy for a journey across time, the first stage of which is conducted by Brian Rogers, who leads us through the intricate history of Shinjuku Station. Nakahara Hiroshi will complete our historic tour with the second part

EDITORIAL

4

Aurel Baele, Luigi Zeni, Marty Borsotti

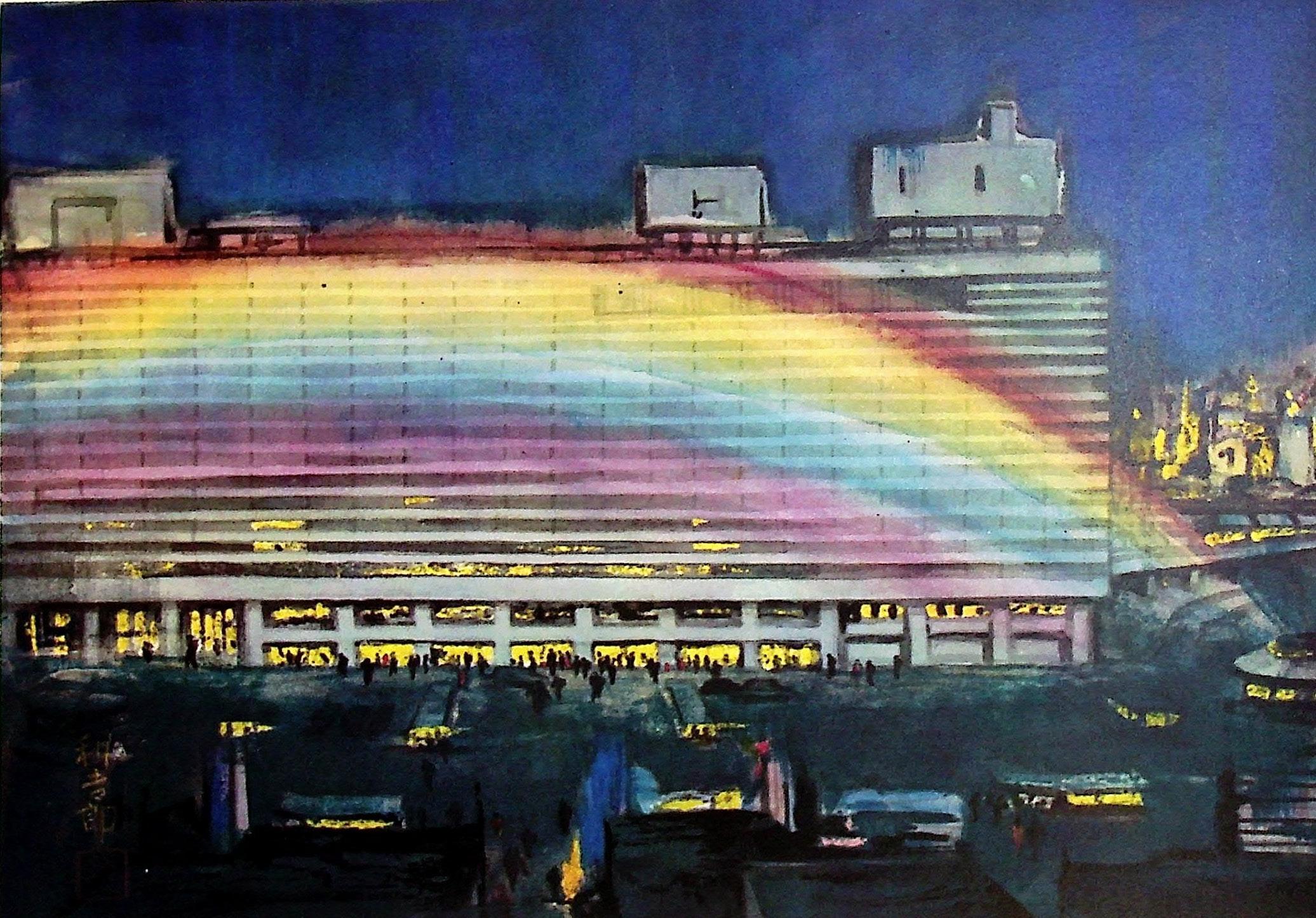

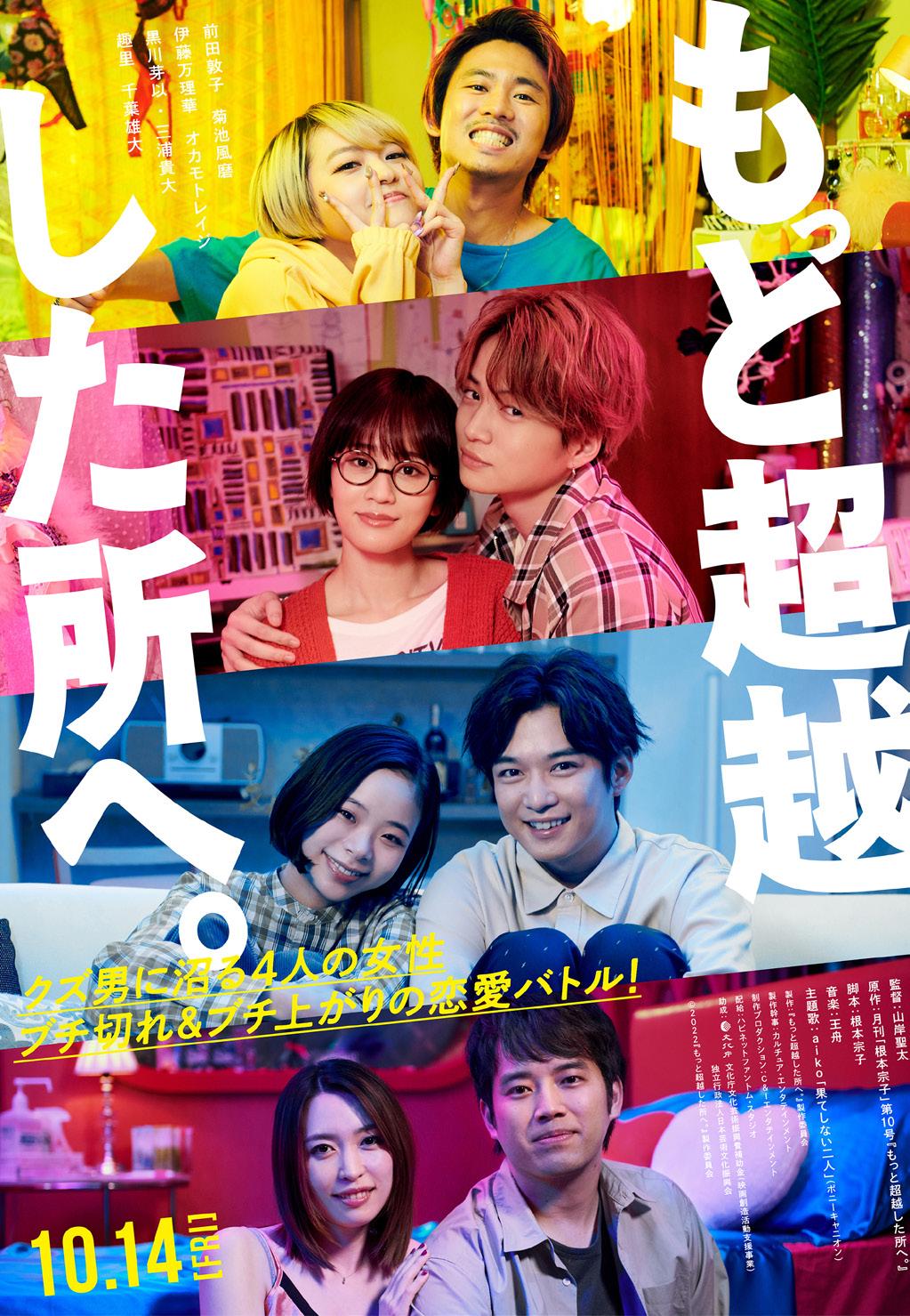

of his article dedicated to the Mōri clan, focusing on the construction of Hiroshima Castle during the late 16 th century. As a conclusion for the issue, Feyyaz Temuer has prepared a piece about the world of competitive fighting games, focusing on the legendary figure of Daigo Umehara; quite a treat for videogame fans. Finally, our reviews have been covered by Olivia Chollet, who delves into the intimate world of author Katherine Tamiko Arguile, and Christian Esposito, who has dedicated a bilingual (Italian-English) review to the Nippon Connection film festival held in Frankfurt in 2023. We have had the honour of collaborating with Nippon Connection since 2021 and we hope you will enjoy reading Christian’s review of To the SUPREME! .

It is quite a line-up for this hot season, which we are celebrating with a new logo dedicated to aubergines, or nasu as they are called in Japanese. At Wasshoi! we are quite fond of this summer fruit, but we did not choose it for its culinary properties (nor for the infamous emoji!). In Japan, August is the month dedicated to the Obon festivities, which involve an important tradition of honouring the deceased. To discover more about the importance of aubergines during Obon please read the essay following this editorial.

Before leaving you to your reading, allow us to tease our next thematic publication, scheduled for Winter 20232024. It will be dedicated to natural disasters in Japan, coinciding with the centenary of the Great Kantō earthquake in 1923. And now, without further ado, let’s start Wasshoi! #6 with the same old drill:

5

Wasshoi! Wasshoi! Wasshoi!

6

OBON FESTIVITIES and the Aubergine Offering

Marty Borsotti

It is said that on the first day of the seventh month of the old Japanese lunisolar calendar 1 the lid covering the entrance to the otherworld opens, releasing in the process the souls of the dead.

On this day, kamabuta tsuitachi ( 釜蓋 朔日 , the first day of the iron lid), hell literally breaks loose, and all sort of spirits rush towards the realm of the living, from harmless and benevolent ancestors to recently departed souls ( aramitama 新霊 , new souls) who are still dangerous for people and thus need to be appeased by their families. Within this spirit mob the most threatening are those who do not have any ties left with the living ( muenbotoke 無縁仏 ) and need similar rituals performed, as they could wreak havoc under the form of hungry ghost-demons ( gaki 餓鬼 ). Such is the beginning of Obon お盆 , the Japanese festivity to honour the deceased, in particular a household’s ancestors, but also to ease the pain of angry souls.

The tradition originated in India at the very inception of Buddhism and has been celebrated in Japan since the 8 th century AC. Nowadays, Obon is Japan’s second most important festivity and features all sort of practices, from the well-known Bon dances ( bon odori 盆 踊り) to visits to one’s family temple to pray for the souls of the dead. The first period of this festivity, called ‘welcoming bon’ ( mukaebon 迎盆 ), for the fami -

lies who had a loss during the previous year begins on the 1 st of August and lasts up to the 13 th of August, the last day available to conduct the preparations to welcome the souls ( shōryō mukae 精霊迎え).

One of the most important preparations during this first half of Obon consists in cleaning the cemeteries, especially by cutting the grass that might have overgrown during the previous rainy month, in order to create a path for the souls to follow ( bon michi tsukuri 盆道作り). This practical task is accompanied by a symbolic practice, offering the dead a cucumber representing a horse and an aubergine representing a cow, who are meant to help cut the grass. The vegetables traditionally have four sticks plunged into them to imitate the legs of the animals. In fact, the horse and the cow ‒ represented by the cucumber and the aubergine ‒are also meant to serve as a mount for the souls in their journeys. They are believed to carry the souls of the ancestors to the realm of the living and back to the underworld during their send-off ( okuri bon 送り盆 ) the last days of Obon, typically between the 15th and 16th of August. 2

2 In the past, Obon used to last a whole month, while in the northern regions of Japan Obon can still be celebrated up to the 20 th of August.

7

1 Corresponding to today’s 1 st of August.

ESSAY

JAPAN AS A PIONEER IN INTANGIBLE HERITAGE POLICIES

Alice Balle 1

This article is a presentation on the flaws which have been progressively protecting intangible heritage, specifically through the concept of national human treasure, and how it was developed into UNESCO protection measures.

What are Cultural Heritage Policies, and why Do they Matter?

In the case of cultural heritage, observing and studying policies may seem like a passive way of consuming technical information, but it is very important to know how a country has evolved through its heritage legislation. Such policies reflect the evolution of national and institutional awareness around cultures, and their Authorised Heritage Discourse (AHD). A review of heritage policies retraces the increasing awareness that cultural goods (tangible or intangible) exist, that they have historical, economic, identity, political, and possibly educational value, and that they

must be actively protected. Therefore, the way in which the various laws have been put in place is particularly relevant because they will highlight different protection needs, the institutional approaches, and different sensitivities of the group. While I cannot explore every detail in the case of Japan, I will present a broad and essential outline as to why Japan has been a pioneer of intangible heritage protection.

1 Alice Balle is a cultural heritage historian specialising in the use of new technologies. With a multidisciplinary profile tending towards anti-disciplinarianism, she conducts research combining hybrid approaches, abstract and concrete thinking, theoretical concepts and empirical data.

9 ARTS / HISTORY / KEYNOTE

POLITICS

What are Cultural Heritage Policies and Why Do They Matter?

In its early phase from 1870 to 1898, Japanese heritage protection was mostly focused on inventory and light repairs, as well as increasing awareness of heritage value. It was during the Meiji Era (1868–1912) that Japan took its first steps towards conservation legislation. Traditionally, most of the cultural properties were protected by aristocratic and samurai families, but feudal Japan ended brutally in 1867, when the Meiji Restoration came to pass. The Meiji Era was also marked by a strong anti-Buddhist movement, which resulted in the dismantling and sale of many traditional buildings, art collections, and precious objects, particularly during the series of events known as Haibutsu Kishaku 廃 仏毀釈 (literally ‘abolish Buddhist icons and destroy Shākyamuni’s teachings’). It was apparently Machida Hisanari ( 町 田久成 ; 1838–1897) who, after a stay in Europe during which he observed heritage protection measures, faced the destruction that marked the beginning

of the Meiji Era, and became aware of the danger of losing part of the national culture. Arriving at the position of senior official in charge of higher education ( daigaku taijo 大学大丞 ), he suggested to the Department of State ( daj ō kan 太政官 ) on the 23 rd May 1871, the establishment of a decree ‘For the protection of antiquities’ (literally decree for the conservation of ‘old objects and old things’, koki kyūbutsu hozon kata , 古 器旧物保存方 ), and a National Museum ( shūkokan 集古館 ).

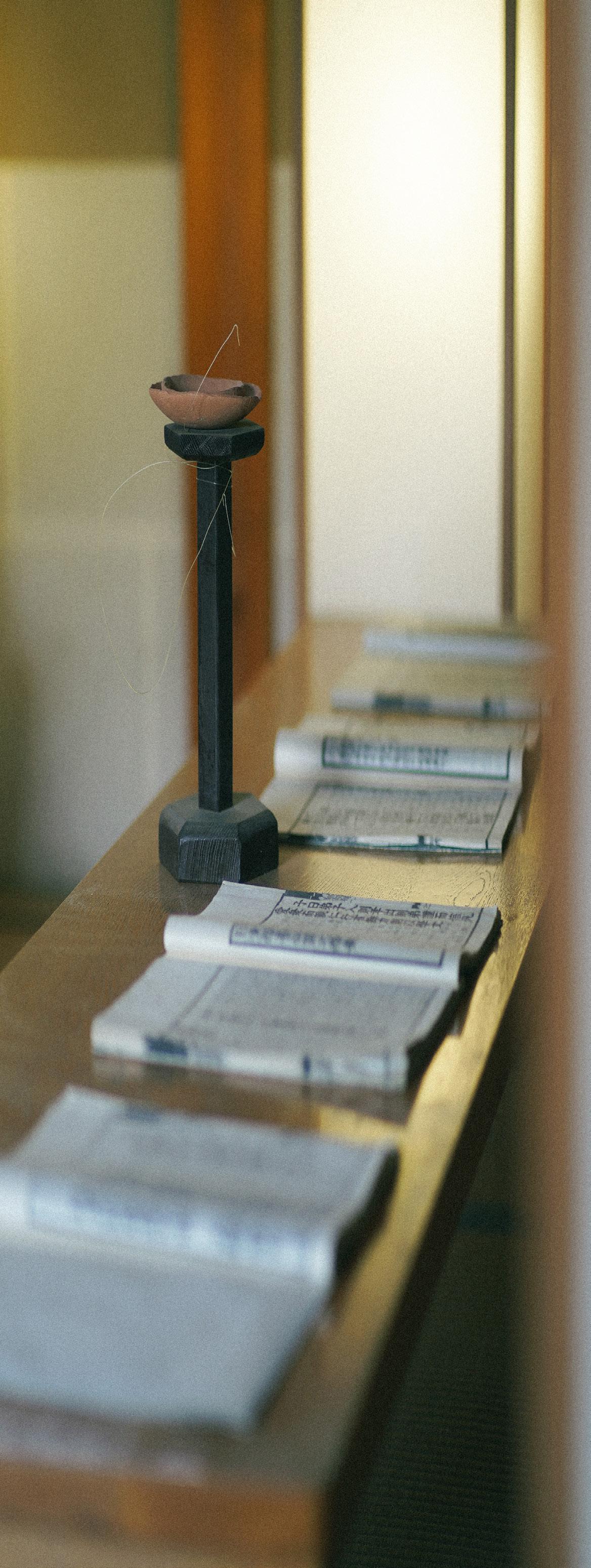

Prefectures, temples, and shrines were required to list their valuable artefacts and remarkable buildings. Funds were then allocated to start various censuses and surveys, leading to repairs and reconstructions (539 shrines and temples in 1894). From 1888 to 1897 a survey was carried out by Okakura Kakuzō ( 岡倉覚三 ; 1863–1913) and Ernest Fenollosa (1853–1908), and around 210,000 objects of artistic or historic merit were evaluated and catalogued.

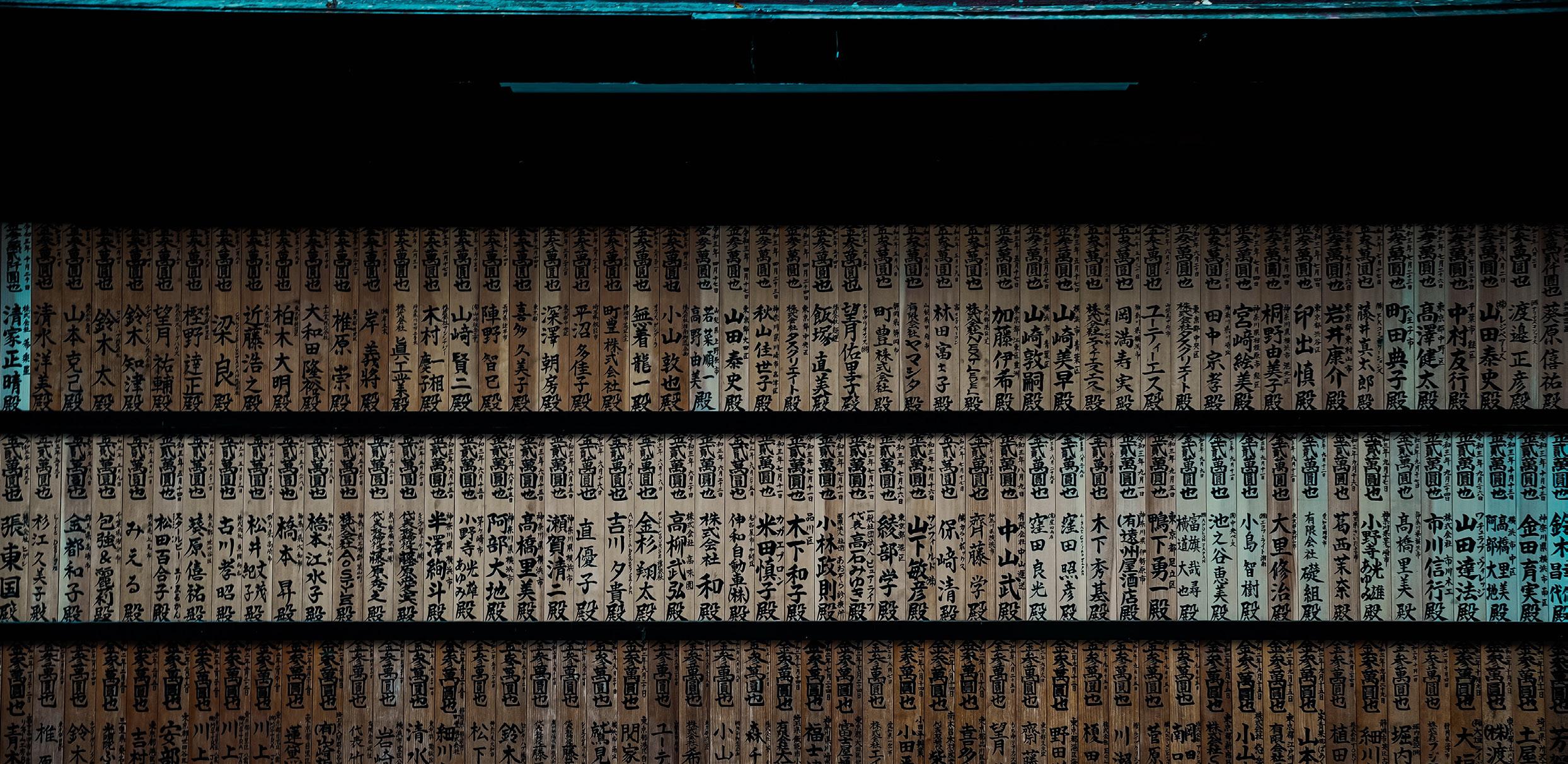

In a second phase, Japan saw its first strong protection and restoration laws, starting with temples and shrines. On the 5 th June in 1897, it led to the promulgation of the ‘Ancient Temples and Shrines Preservation Law’ ( koshaji hozon-ho 古社寺保存法 ) under the guidance of Itō Chūta ( 伊東忠太 ; 1867–1954), targeting the preservation and restoration of Japanese architecture and historic art through financial support. In this text appeared for the first time the term ‘National Treasure’ ( kokuho 国宝 ). In 1898 the ‘Law on Lost and Found Objects’ ( ishitsubutsu-h ō 遺失物法 ) was also enacted, which required official declarations of buried objects that might be of archaeological, artistic, or scientific interest.

11

The third phase broadened the heritage definition to include natural assets and extended the list of buildings considered as potential national treasures. After the adoption in 1911 of a ‘Project for the Conservation of Historical Sites and Natural Monuments’ ( Shiseki oyobi tennen kinenbutsu hozon ni kan suru kengian 史蹟及天然 紀念物保存ニ関スル建 議案 ), the ‘Law for the Conservation of Historical Sites, Places of Scenic Beauty, and Natural Monuments’ ( Shiseki meish ō tennen kinenbutsu hozon-ho 史 蹟名勝天然紀念物保存法 ) was enacted in 1919, giving them the same kind of protection as artwork, architecture, etc. The term ‘national treasure’ ( kokuho 国 宝 ) became more central as the latter law was reformed in 1929 to become the ‘National Treasures Preservation Law’ ( kokuh ō hozon-ho 国宝保存法 ).

This new law, replacing the one of 1897, extended the focus to, for example, teahouses, religious buildings, and castles, allowing for numerous restorations financed by the national budget. Then on the 1 st April in 1933, the Law on the Preservation of Important Works of Art was passed ( jūy ō bijutsuhin hozon-ho 重要美術品保存法 ). While Japan was facing a global depression, this law was aimed at preventing the export of non-protected art objects by offering a simple procedure of designation.

Finally, the fourth phase in 1950 greatly expanded the scope of cultural properties to include intangible heritage or popular knowhow and eased the classification procedure. On the 30 th May 1950, after the Second World War, and particularly after the heavy losses caused by a fire in the main hall of the Hōry ū -ji temple in Nara Prefecture, the ‘Law for the Protection of Cultural Property’ ( bunkazai hogo-h ō 文化財 保護法 ), was passed; it is still in operation today. This law combined those of 1919, 1929, and 1933, allowing the selection of cultural properties, setting restrictions on their alteration, and providing measures for the preservation and utilisation of such properties. It has since undergone numerous amendments, particularly in 1954, 1975, and 2004, which gradually broadened the meaning of the term ‘cultural property’ ( bunkazai 文化財 ). For example, new categories such as ‘cultural landscape’ have been added, and folkloric heritage now includes ‘popular know-how’. The practice of ‘inscription’, which is less restrictive than ‘classification’, has also been introduced. Initially, this law of 1950 was targeting tangible heritage protection with three broad categories. But in 1954, they were reorganised into four categories, with the addition of intangible heritage: Tangible Cultural Properties, Intangible Cultural Properties, Folk Materials, and Monuments. In 1975, the law was extended to protect districts and groups of buildings, but also technical skills, for the conservation of Cultural Properties. Finally, in 2004 ‘Important Cultural Landscapes’ as well as ‘Folk Techniques’ (included in ‘Folk Cultural Properties’ description) were added.

For more details, we invite readers to refer to the article by Inada Takashi ( 稲田孝司 ), which presents in detail the different evolutions of this law.

23 rd of May 1871

5 th of June 1897 1919 1929

The Plan for the Preservation of Ancient Artifacts ( koki ky ū butsu hozonkata 古器旧物保存方 )

The Ancient Temples and Shrines Preservation Law ( koshaji hozon-ho 古社寺保存法 )

Law for the Conservation of Historical Sites, Places of Scenic Beauty and Natural Monuments ( shiseki meish ō tennen kinenbutsu hozon-ho 史蹟名勝天然紀念物保 存法 )

National Treasures Preservation Law ( kokuh ō hozon-ho 国宝保存法 )

1 st of April 1933 30 th of May 1950

Law on the Preservation of Important Works of Art ( jūy ō bijutsuhin hozon-h ō 重要美術品保存法 )

Law for the Protection of Cultural Property ( bunkazai hogo-ho 文化財保護法 )

The Current Cultural Heritage Categories in Japan2

There are currently seven different categories of cultural property recognised under Japanese law.

Tangible Cultural Properties ( y ū kei bunkazai 有形文化財 ) are cultural products with a physical form that possess high historic, artistic, and academic value to Japan, such as structures (buildings), crafts, sculptures, calligraphic works, classical books, palaeography, archaeological artefacts, and historic materials. Fine arts and crafts and structures are considered two separate categories. Cultural properties can then be designated as ‘National Treasures’ ( kokuhō 国宝 ) or ‘Important Cultural Properties’ ( j ū yō bunkazai 重要文化財 ).

By 2016, there were 13,057 Important Cultural Properties (including 1,097 National Treasures) of which 19% were structures.

Intangible Cultural Properties ( mukei bunkazai 無形文化財 ) refers to stage arts, music, craft techniques, and other intangible cultural assets that possess high historic or artistic value for the country. It refers to the art itself as well as the holders of techniques, that is to say, the individuals or groups of individuals who represent the highest mastery of the practices concerned. Special recognition can be offered to some individuals under the title of National Living Treasure. By 2016, there were 112 holders (77 designations) and 27 groups named as Important Intangible Cultural Properties.

2 For more information about the types of cultural properties, see the official website of the Agency of Cultural Affairs (in English), or the presentation of the Law for Protection of Cultural Properties, Article 2.

Folk Cultural Properties are divided between tangible ( mukei minzoku bunkazai 無形民俗文化財 ) and intangible properties ( y ū kei minzoku bunkazai 有形 民俗文化財 ) but are legally recognised as one category. They refer to cultural properties that relate to the role and influence of traditions in the daily life of Japanese people, such as manners and customs; folk performing arts and techniques (food, tools, instruments, clothing, housing, occupation, religious faith, annual events, etc.). By 2016, there were 216 Important Tangible Folk Cultural Properties, and 290 Important Intangible Folk Cultural Properties.

Monuments ( kinenbutsu 記念物 ) are separated into three categories: Historic Sites ( shiseki 史跡 ), Places of Scenic Beauty ( meishō 名勝 ), and Natural Monuments ( tennen kinenbutsu 天然記念物 ). In each of these categories, some items can be designated as ‘special’. Here is a list of examples from the Agency of Cultural Affairs of Japan: Shell mounds, ancient tombs, sites of castle towns, sites of forts or castles, old houses, gardens, bridges, gorges, seashores, mountains, animals, plants, minerals, and geological features of a high scientific value to Japan. By 2016, there were 1,021 Natural Monuments (including 75 Special Natural Monuments), 398 Places of Scenic Beauty (including 36 Special Places of Scenic Beauty), and 1,759 Historic Sites (including 61 Special Historic Sites).

Cultural Landscapes ( bunkateki keikan 文化的景観 ) are described as places ‘formed by the climate of a given region and people's lives or work there, and are indispensable for understanding the livelihood and work of the Japanese people’. Some items can be designated as Important Cultural Landscapes. By 2016, 50 areas were identified as such.

Preservation Districts for Groups of Historic Buildings ( dentōteki kenzōbutsu-gun 伝統的建造物群 ) is a category added in 1975 through an amendment of the original law of 1950. It aims to protect groups of traditional buildings which, together with their environment, form beautiful scenery, such as historic cities, towns, and villages in Japan, including castle towns, post-towns, and towns built around shrines and temples. By 2016, there were 110 Important Preservation Districts for Groups of Traditional Buildings across Japan.

17

The Japanese Sensitivity to Intangible Heritage

In our case, it is more specifically the revisions of 1954 and 1975 to which we wish to draw attention, since these made it possible to integrate the notion and certification of a National Human Treasure ( ningen kokuho 人間国宝 ). This allows the classification and recognition of not simply an object, document or building, but of an individual or group of individuals who are designated by the government as ‘holders of an important intangible cultural heritage’ ( jūy ō mukei bunkazai no hojisha mata wa hoji dantai 重要無形文化財の保持者又は保持団 体 ). Inada Takashi explains 3 : ‘ The aim is not to designate the protection of a cultural property as such, but to ensure the continuation of 'traditional techniques or technical skills' and 'the framework that guarantees their existence' by introducing a designation of 'selected conservation technique'. This characterisation of skills also corresponds to recognition as ‘a person or group holding selected conservation techniques ’ ( sentei hozon gijutsu no hojisha mata wa hozon dantai 選定保存技

術の保持者又は保存団体 ).

Although the term ‘National Treasure’ was not originally intended to be used to value individuals, this practice was quickly adopted, so much so that by 1979 there were already about 75 individuals bearing the title, which was recognised by UNESCO in 2003. It is now limited to crafts and the performing arts and is divided into 16 categories. Today, there are 57 individuals (and 12 groups) with this title in the field of performing arts and 57 individuals (and 13 groups) in the field of crafts.

18

3 Inada Takashi, ‘The Evolution of Heritage Preservation in Japan since 1950 and its Role in Constructing Regional Identities,’ Ebisu no. 52 (2015): 21–46.

In this sense, Japan has been a pioneer in the field of intangible heritage, since they have been using the term from as early as 1950, while UNESCO only officially recognised it in 2003. However, this notion of ‘living national treasures’ is a compelling illustration of how an individual and the know-how they possess can be, in themselves, the bearers of a sense of heritage beyond the object they produce.

Thus, by emphasising the longevity of traditional wisdom, its transmission and its recurring practice, it will not be surprising to see in Japan an act that is often outlawed in Europe: deliberate destruction. Indeed, Europe is almost exclusively focused on the object produced. Therefore, the main objective is precisely to avoid any destruction of heritage objects and materials.

In Japan, although the object produced or the building has a value itself, it is commonly accepted that intentional deconstruction of material products will activate, stimulate, and revitalise the know-how that gave them form. It will make it possible to actively preserve this knowledge, and with it, the memory it bears. This perspective is also part of the Shinto belief about the impermanence of all things, the death and renewal of nature. This destruction is a way of passing building techniques from one generation to the next.

19

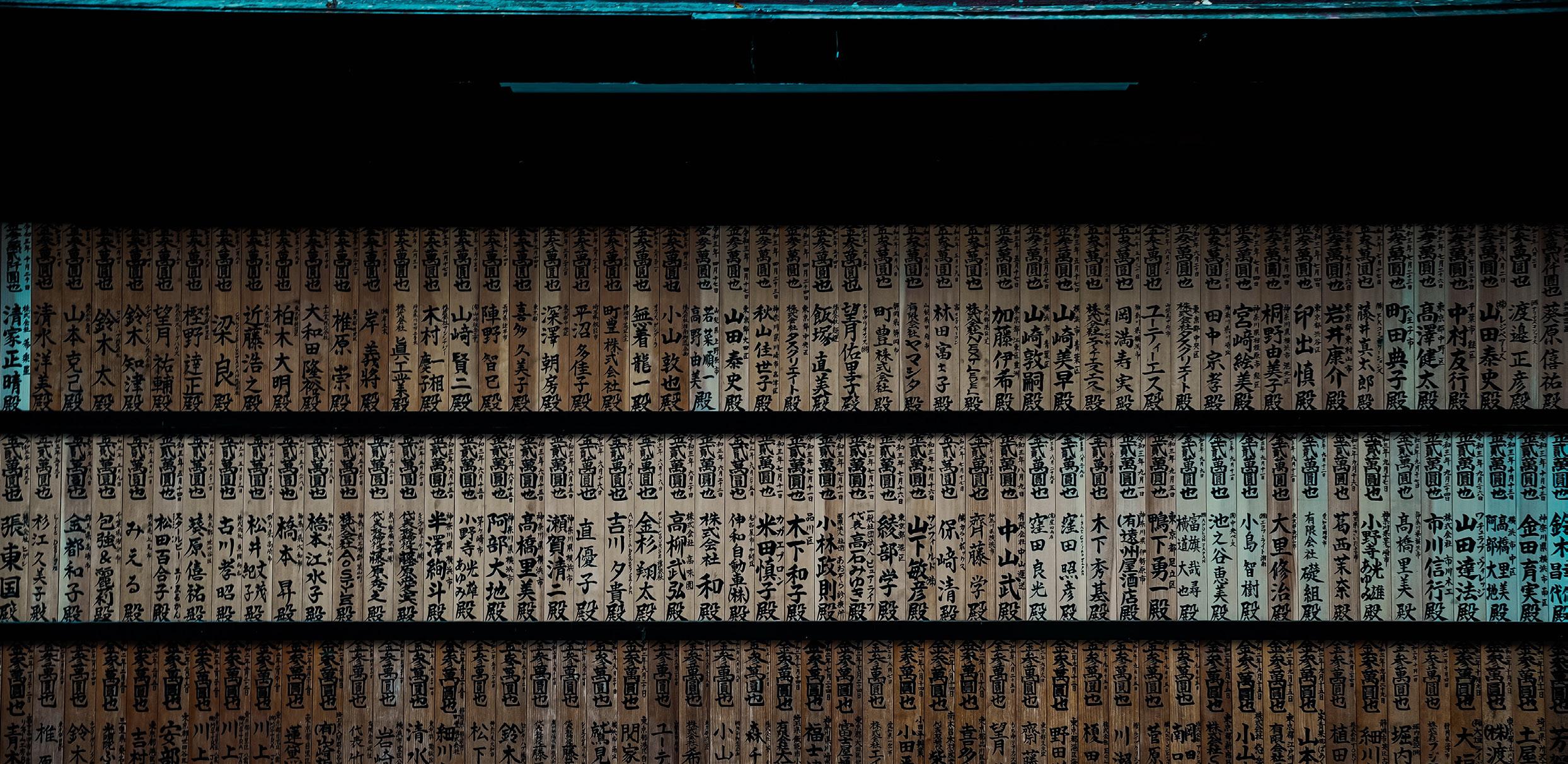

One of the most famous examples of intentional destruction is the Ise Sanctuary ( ise-jingu 伊勢神宮 ) within Ise-Shima National Park, Mie Prefecture.

Since the 7 th century, it has been regularly demolished and then rebuilt according to a specific chronology called shikinen-seng ū 式年遷宮 , which corresponds to every 20 years. In the article ‘Authenticity and Reconstruction of Memory in Japanese Monumental Architecture’, the authors question how the value of authenticity emerges when it comes to a ‘quasi-oral architectural tradition’. As Alain Schnapp puts it, 4 ‘ the Japanese have thus developed a technique of artisanal memory which, in the eyes of a Hellenist, recalls the competition between words and marble: here the cyclically transmitted know-how is supposed to prevent the material corruption of the shrine. In the long run, the gesture of the craftsmen, which is always transmitted, prevails over the most solid of constructions. ’

4 Alain Schnapp, La conquête du passé: aux origines de l’archéologie (Paris: Éditions Carré, 1993), 98.

4 Alain Schnapp, La conquête du passé: aux origines de l’archéologie (Paris: Éditions Carré, 1993), 98.

Here again, we can see how the Western understanding of heritage value, and the processes involved in its recognition, do not always make sense beyond their original purpose.

Whether it is the acquisition of the finished object, the value of its materials, the method of production, its function, or the context of its use, the justification of heritage value is specific to the group of individuals connected to it. Heritage creation is the result of a process, specific to each situation, each place, each era, each society. More than ever, these elements must be, if not fully understood, then at least respected and prioritised. The Western view – that is to say the occidental approach of heritage in terms of value attribution and decision making – is rooted in many of the practices now exported. Therefore, it is necessary to tend towards greater prudence and humility on this matter.

This broadening of the definition of cultural heritage and its subjectivity has occurred over the last few decades. It has changed from an exhaustive description of its content to a more dynamic approach, describing the process through which an asset becomes a piece of heritage. That has also allowed for us to question the concept of authenticity and give it a more subjective definition beyond Western views. Indeed, as stated, what makes an object a heritage asset will depend on the period, the culture, the group of people, and it will answer to deep human needs, such as the search for continuity, or the transfer of identity. Some groups will value the materials, the fabrication techniques, the usage, the owner, or the history of the object.

Therefore, cultural heritage’s definition has had to be reconsidered in order to include intangible assets such as songs, recipes, rituals, or individuals with precious skills. The observation of Japanese laws greatly testifies to their remarkably early awareness regarding the value of intangible assets.

21

22

Suggested Readings

Smith Laurajane. Uses of Heritage , 1 st edition. London: Routledge, 2006.

Fu Yi, Sangkyun Kim, Tiantian Zhou. ‘Staging the ‘Authenticity’ of Intangible Heritage from the Production Perspective: The Case of Craftsmanship Museum Cluster in Hangzhou, China’. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 13, no. 4 (2015): 285–300.

Masatsugu Nishida, Cluzel Jean-Sébastien, Bonin Philippe. ‘Authenticity and reconstruction of memory in Japanese monumental architecture’. Espaces et sociétés 131, no. 4 (2007): 153–170.

Edwards Walter. ‘Japanese Archaeology and Cultural Properties Management: Prewar Ideology and Postwar Legacies.’ In A companion to the anthropology of Japan , ed. Jennifer Ellen Robertson (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2005), 36–49.

Inada Takashi. ‘The Evolution of Heritage Preservation in Japan since 1950 and its Role in Constructing Regional Identities’. Ebisu no. 52 (2015): 21–46.

23

THE BURDEN OF CAREGIVING AND THE HISTORICALLY ROOTED EXPECTATIONS OF WOMEN IN JAPAN

Samira Hüsler

Demographic Challenges of Japan

Japan is facing drastic demographic change due to a simultaneously shrinking and ageing population. The number of adults aged 65 and over is gradually increasing, having already exceeded 25% of the Japanese population by 2016. This phenomenon does not only concern the health care sector or the everyday life of older adults, but also raises socio-economic and gender issues. To provide a good overview of the current situation, this topic is divided into four subchapters. Each chapter will deal with a different social issue or change, starting with the need for caregivers, followed by fundamental changes within care of older adults, the influence on gender roles, and, finally, the rise of alternative approaches in the care sector.

Part 1 – ‘Crisis 2025’: Baby Boomers in need of Caregivers

Part 2 – Between Family and State: Changes in Japan’s Ageing and Elderly Care

Part 3 – The Burden of Caregiving and the Historically Rooted Expectations of Women in Japan

As stated in Parts 1 and 2 of this series, Japan is a super-aged society. The ageing of the population is due to a high life expectancy and rather low migration and birth rates. The development of a declining birth rate is directly connected to the position, role expectations, and opportunities of Japanese women. To provide a deeper explanation, this article will briefly discuss the history of women in Japan and relate it to demographic processes as well as care expectations.

25 SOCIOLOGY / HISTORY

ANTHROPOLOGY

From Amaterasu to Ryōsai Kenbo

A Brief Overview of Women's Social Roles in Japan

To what extent one can define Japan as a patriarchal culture in the Western sense continues to be an intensely discussed topic within social science. However, researchers agree that Japan has evolved from a matrilineal, uxorilocal society to a more patrilineal, virilocal 1 society. Arguably, the inclusion of socalled ie seido (a house society in social anthropological terms) in the civil law (family law) of the dainippon teikoku kenpō (Constitution of the Empire of Greater Japan) in 1889 is directly linked to the spread of patriarchal and hierarchical organisational structures.

However, the family organisations that existed before the constitutional changes are not fully traceable due to a lack of data on the middle and lower classes. Limited data leads to the conclusion that there were regional and socio-economic differences. For example, three-generation households were

common in the Tōhoku region, while two-generation households were more common in Kyūshū and around Chūbu 2 , and nuclear families tended to emerge especially in southern Kyūshū. In terms of social systems, given that in Shintoism the sun goddess Amaterasu (the ancestress of the tennō lineage) is female, that women held significant positions in this religion (e.g., miko , priestesses), are known to have been part of the productive labour force (e.g., own businesses), and were not excluded from political office (e.g., ruling empresses) or succession, it is assumed that there was a tendency toward a matriarchal society. 3

The gradual emergence of patriarchal structures is associated with various social phenomena, including the rise of Buddhism and the establishment of Confucianism (see ritsuryō 4 ).

Notes

1 The terms matrilineality and patrilineality refer to social but also material succession. While matrilineality refers to the passing on/inheritance of social characteristics and property through the female line (mothers to daughters), patrilinerality stands for the passing on through the male line (fathers to sons). The residence rule refers to a couple's residential choice after marriage (based on social norms). Virilocal stands for 'location of the husband' and uxorilocal for 'location of the wife'.

2 Akira Hayami and Satomi Kurosu, ‘Regional Diversity in Demographic and Family Patterns in Preindustrial Japan,’ Journal of Japanese Studies 27, no. 2 (2001): 295-321..

3 Haruko Wakita and Suzanne Gay, ‘Marriage and Property in Premodern Japan from the Perspective of Women's History,’ The Journal of Japanese Studies 10, no. (1984): 73-99.

4 Shanon Sievers, Flower in Salt: The Beginnings of Feminist Consciousness in Modern Japan (Stanford Cal.: Stanford University Press, 1986).

26

Legally, women were pushed out of the public sphere through the Taika Reforms of 645 AD – however, they are not assumed to have had any actual influence on the everyday lives of ordinary Japanese women. Normatively, the cultivation of Confucian values within the warrior caste – approximately 5-7% of the total population – was more significant. Women of this caste were under the guardianship of men (fathers, husbands, sons) and received gender-specific education from the age of seven. 4 Their primary role consisted of being good wives and devoted daughters-inlaw. It was not until the Meiji Restoration and the official introduction of the ie seido that these and similar norms were imported into the lower social strata.

Therefore, one can refer to this as a top-down phenomenon. The ie seido is a social, legal, and economic as well as hierarchical family unit (house society), consisting of relatives and other members of the household. The house society fell under the authority of a male leader, the koshu (head of the family). It was only with the introduction of this system that women tended to move in with their husbands after marriage and become part of their families (see yometori 5 ). As mentioned, the system was based on the paternalistic family system of the former warrior caste.

27

5 Haruko Wakita and David P. Phillips, ‘Women and the Creation of the ‘Ie’ in Japan: An Overview from the Medieval Period to the Present,’ U.S.-Japan Women’s Journal , English Supplement, no. 4 (1993): 83-105.

Hence, under dainippon teikoku kenpō , women lost their individual legal capacity, lost property rights, were disadvantaged in divorce law, and excluded from the right to vote. 6 It can be concluded from the records of the koseki (family register), which was already introduced back in 1872, that the topdown re-organisation of families led, at least officially, toward the homogenisation of family structures. 7

Furthermore, the perception of women expanded from the self-sacrificing daughter-in-law to the good wife and wise mother ‒ ryōsai kenbo . The rediscovery of the mother's role and the educational tasks associated with it is linked to Western and nationalistic influences. The new educational task was seen as a service to the nation. As a result, the mother's role became more socially relevant. At first, this conception of the good wife and wise moth -

er was promoted primarily among the socio-economic upper class. However, during industrialisation, nationalism, and modernisation, and through its introduction into elementary schools in 1911, ryōsai kenbo gained widespread recognition. 8 The intended role of women was thus narrowed to domestic tasks such as housework, child rearing, and care of older relatives.

It can be concluded that the role of Japanese women has changed continuously over the past hundred years. Since the end of the 19 th century, an understanding of women's role in terms of reproduction increased, which emphasised the importance of the wife and mother.

Notes

6 Ingrid Getreur-Kargel, ‘Geschlechterverhältnis und Modernisiering,’ In Getrente Welten, gemeinsame Moderne? , ed. Ilse Lenz and Michiko Mae (Opladen: Leske & Budrich, 1997), 19-58.

7 Reiko Yamato, 'Changing Attitudes towards Elderly Dependence in Postwar Japan,' Current Sociology 54, no. 2 (2006): 273-291.

8 Shizuko Koyama, Ryōsai kenbo: The educational Ideal of ‘good wife, wise mother’ in Modern Japan (Leiden: Brill, 2013).

28

Post-World War II The Sequel to Care Expectations

Japan was democratised after its defeat in World War II. As a result, ie seido was removed from the constitution in 1947 and women's suffrage was fully introduced – this was in part due to the strong U.S. influence and its conception of law (see Ethel Weed and Japanese feminists' leaders). The subsequent economic boom and spread of certain U.S. ideals increased the number of full-time housewives, the so-called sengyō shufu . Expectations regarding caregiving tasks and the family constellation of the pre-war period remained unchanged. One of the first upheavals occurred as a result of changes in the labour market, which were crucial for urbanisation. This led to a shift from the ie seido -related daikazoku (multigenerational family; extended family) to a couple-based family from the 1960s onward. 9

The speed of this societal change varied strongly from region to region. Particularly in rural areas, many families remained organised in the pre-war fashion. Nevertheless, both the distance between relatives and the number of women in paid employment increased gradually across the country. In the context of this development, the shift in employment sectors must be noted; Before the 1960s, most women worked (unpaid) in family or agricultural businesses; between 1960 and 1975, the proportion of women who did not work in agriculture increased by 74%. 10 Nowadays, more than 50% of women older than 15 and 70% of women in their 40s are part of the paid workforce, 11 which indicates a consistent trend.

9 Liping Shi, ‘Continuities and Changes in Parent-child Relationships and Kinship in Postwar Japan:

Examining Bilateral Hypotheses by Analyzing the National Family Survey (NFRJ-S01),’ GEMC Journal 2 (2010): 48-67.

Notes

10 Karen Holden, ‘Changing employment patterns of women.’ Work and lifecourse in Japan , edited by David W. Plath (Albany, N.Y., StateUniversity of New York Press: 1983), 34-46.

11 Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Japan, ‘Annual Report on the Situation of Working Women 2012,’ Accessed December 10, 2022.

29

Despite social change, the understanding of women's roles has undergone little to no adjustment. According to surveys, the ideal woman is still described as a wife and mother and not, for example, a career woman. 8 It is unsurprising that care for older adults is still considered as part of the domestic workspace and therefore still seen as a woman's realm. However, since the proportion of people over 65 was only about 5% until the 1950s, the years devoted to care were short and it was easier to combine the caregiving and other workloads. What has made this care model more difficult is increased life expectancy, demographic change, and a subsequent doubled or even tripled workload for many women. 7

30

Male Labor force participation rate 90% 78% 65% 53% 40% 1973 1978 1983 1988 1993 1998 2003 2008 2013 2018 Female

Fig. 1 Japan; Statistics Bureau of Japan; Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (Japan); 1973 to 2021; 15 years and older.

Interrelation between Gender Roles and Fertility Rate

The previously mentioned constitutional changes of 1947 coincided with the beginning of the first baby boom: dankai sedai (1947–49). The 1948-49 ky ū y ū sei hogo-hō (Eugenic Protection Law) passed and facilitated abortions as well as family planning. At the same time the state promoted sexual education and the education of girls; this improved their chances within the work market, 12 increasing the number of financially independent women. Due to these and other reasons, the average age of marriage for Japanese women increased to 29.3 years and the number of marriages generally decreased. Since marriage and childbearing correlate, the average age for first births also increased to 30.7 years.

As mentioned above, the reproductive role expectations did not change for women, despite their participation in the labour market. 8 In other words, women continued to do household chores and care for children and older relatives, joining the paid workforce on top of that.

To date, women are rarely found in career-oriented professions due to the inherent difficulty of balancing work and family life. However, a wife is also expected to support her husband in his career, which means that the child-rearing and household tasks are largely carried out by her, even if she herself is employed. She must support her husband’s career, which would be jeopardised if he himself took on domestic tasks. Such circumstances explain, among other things, why many Japanese men still do not help with household chores or do so only to a limited extent. In addition, there is a shortage of daycare places for children ‒ although it must be noted that significant improvements have been achieved since 2013 and far fewer children now end up on waiting lists. 13

12 Yuka Suzuki and Kaori Honjo, ‘The Association Between Informal Caregiving and Poor Self-rated Health Among Ever-married Women in Japan: A Nationally Representative Survey,’ Journal of Epidemiology 32, no. 4 (2021):174-179.

13 Statista Research Department, ‘Number of Children Waiting to be Accepted to Day Care Centers in Japan from 2013 to 2022,’ Accessed December 11, 2022.

32

These efforts show that the Japanese government is indeed trying to improve the current situation. Nonetheless, there is still a lack of daycare services, which further hinders women's ability to combine work and family life. According to studies, 14 this favours gender-specific roles even more, and explains the still existing, though declining, M-curve; the M-curve describes the social phenomenon of the sudden exit of women from (paid) labour in their 30s and 40s. This decline is explained by the fact that the average woman in Japan leaves her job either temporarily or in the long-term due to marriage and child rearing. Those women remaining in the workforce at this point are mainly part-time workers. 15

14 Nobuko Nagase and Mary Brinton, ‘The gender division of labor and second births: Labor market institutions and fertility in Japan,’ Demographic Research 36, no. 11 (2017): 339-370.

15 Hiromi Tanaka-Naji, Japanische Frauennetzwerke und Geschlechterpolitik im Zeitalter der Globalisierung (München: Ludicium, 2009).

Therefore, marriage and starting a family continue to be a major obstacle to women's ambitions and career opportunities. These and other factors, such as unstable economic conditions, do not make family formation attractive, resulting in a low fertility rate. The birth rate therefore declined, despite the dankai junia (baby boom junior) around 1970 and stabilised at a rate between 1.3 and 1.4. A rate of 2.1 is required for population maintenance.

33

U.S. Germany Age

90 75 60 45 30 15 0 15-1920-24 30-34 40-44 50-54 60-64 25-29 35-39 45-49 55-59 65-

Japan rounding up its M-graph (in percent) Female labor force participation rate (ILO 2015)

group

Japan July 2007

Japan July 2017

Fig. 1 M-Curve; Female labour force participation (ILO 2015)

The Icing on the Cake: Care for Older Relatives

As explained in Parts 1 and 2 of this series, Japan is undergoing rapid population ageing. Back in 1970, only 7.1% of the population was older than 65 years, but by 2018 the figure had risen to 28.1%. 16 Although government support, such as kaigo hoken (LTCI; longterm care insurance) in 2000, are being introduced steadily, care for the older adults is still expected to be provided at least partially by family members. This dependence on one's own relatives is seen as a remnant of multi-generational families. With the introduction and improvement of the pension system, the financial burden on relatives was lifted, while expectations of physical and social care remained. 17 Expectations merely adjusted according to household structures, resulting in a preference for one's spouse or children as primary caregivers. 18 Today, 58.7% of primary caregivers are cohabiting family members and only 13% are long-term care service providers. The caregiving role is often carried out by middle-aged women (wives or daughters-in-law) between 40 and 60, even if they are (full-

time or partially) employed. 19 By law, caregivers who support a child or other family member are granted 93 days of leave from work. 12 Despite support measures and the introduction of kaigo hoken , more and more employees are quitting or changing jobs because of caregiving responsibilities – according to the Japan Cabinet Office report of 2018, resignations due to caregiving increased from 47,800 in 2006 to 85,800 in 2016. 19 According to Saeko et al. (2020), there is an elevated chance of leaving work for caregiving reasons if caregiving duties are performed for five or more hours per week. This tendency can again be observed especially among full-time employed women due to the incompatibility of career and care. Particularly among women in fulltime employment, caring for older relatives is associated with existential fears about one's own career and retirement finances. 19

Notes

16 Japan Cabinet Office. Korei shakai hakusho [Annual Report on the Aging Society] (2019), Accessed December 9, 2022.

17Anne Aronsson, ‘Professional Women and Elder Care in Contemporary Japan: Anxiety and the Move Toward Technocare,” Anthropology & Aging 43, no. 1 (2022): 17-34.

18 Kathryn Elliott and Ruth Campbell, ‘Changing Ideas about Family Care for the Elderly in Japan,’ Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology 8, no. 2 (1993): 119–135.

19 Saeko Kikuzawa and Ryotaro Uemura, ‘Parental Caregiving and Employment among Midlife Women in Japan,’ Res Aging 43, no. 2 (2021): 107-118.

34

Moreover, caring for one’s parents is increasingly overlapping with childcare. In Japan, the number of people providing dual care was estimated around 253,000 caregivers (168,000 women and 85,000 men) in 2016. 17 Since even one informal caregiver arrangement harbours health risks (physical and psychological), this risk rises even more when there is a doubled or tripled workload (work, childcare, and care for older adults). It is interesting to note that, according to Suzuki et al., a higher socio-economic background does not reduce the burden on caregivers.

The Triple Burden on Women Must Ease

For centuries, Japanese families were organised in heterogeneous ways. With the official introduction of the ie seido in 1889, the Meiji constitution tended to standardise family organisation and spread patrilineal, virilocal multigenerational families, or ‘house societies’. Ie seido was a social, legal, and economic hierarchical household entity consisting of an extended family and other non-related members of the household.

The system, which was influenced by Confucianism, was imported by the warrior caste into the other social classes (a top-down phenomenon). Through its dissemination, the concept of the woman as a good wife and devoted daughter-in-law, which was extended through modernisation and nationalism to the role of the wise mother, was also able to spread. Today, the archetype of the good wife and wise mother, ryōsai kenbo , survives, even if the wording has changed. As a result, domestic work such as caring for children and older relatives still falls within the scope of women's responsibilities. Although women are now strongly represented

within the productive labour market, these gender-specific role perceptions have not diminished accordingly. On top of that, Japan faces daycare shortages, and men's willingness to contribute to housework has remained low. Precisely these factors highlight the fact that it is more difficult for women to balance family and career and that starting a family is therefore not necessarily considered attractive ‒ as illustrated by the low birth rate (1.3).

In addition to child-rearing responsibilities and paid employment, women over the age of 40 are also more likely to be in a caregiving role for an older relative. Not even the introduction of government support has been able to marginally mitigate the expectation on women when it comes to older care, resulting in women largely becoming primary caregivers for older relatives. Due to demographic change, caregiving responsibilities for children and older relatives are increasingly colliding. This strain can have far-reaching health consequences.

36

Despite government efforts and successful improvements (e.g., greater daycare availability and the pension system), the current situation is neither bearable in the long term nor conducive in terms of birth rate. As societies age, industrialised countries will have to rely on non-gender-specific work models. Care responsibilities need to be socially renegotiated without undermining women's opportunities and ambition.

Suggested Readings

Takamae, Eiji. The Allied Occupation of Japan . London: Continuum Intl Pub Group, 2003.

Saeko, Kikuzawa and Ryotaro Uemura. “Parental Caregiving and Employment among Midlife Women in Japan,” Sage Journals 43, no. 2 (2021): 107-118.

Shinozaki, Kaori, Iha, Kazue and Tomoaki Tabata. “Shigoto ikuji kaigo no san-sha-kan no wāku famirī konfurikuto ni [Work-family conflicts between work, childcare, and caregiving],” Transactions of the Academic Association for Organizational Science 4, no. 1 (2015): 194-199.

37

38

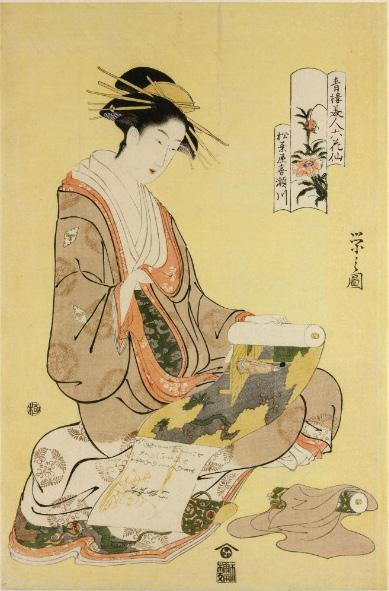

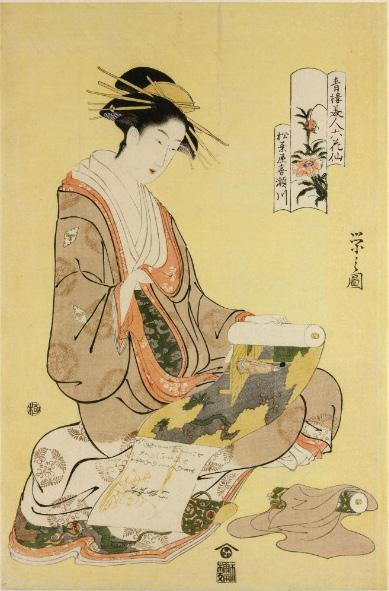

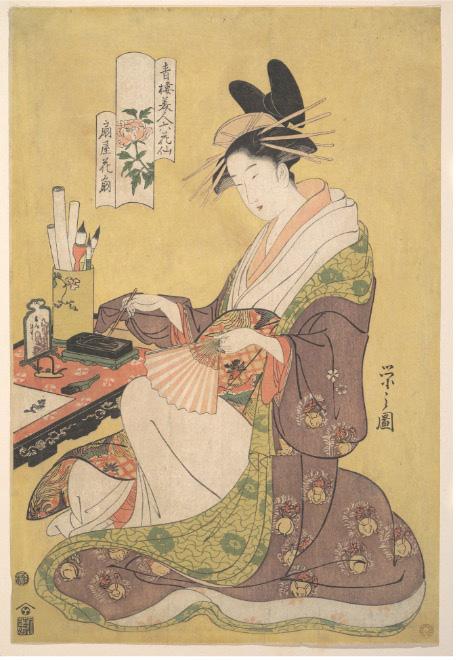

Fig. 1 Hosoda Eishi, Seirō Bijin Rokkasen: Matsubaya Kisegawa (Six Blossoming Masters of Beauty in Yoshiwara: The Courtesan Kisegawa of the Matsuba House; 青楼 美人六花仙 松葉屋喜瀬川 ), Mid 1790s. Woodblock print, ink and color on paper.

MULTI-LAYERED AND HIDDEN MEANINGS

Hosoda Eishi and the Tales of Ise

Momoka Asano

Tales of Ise in the Edo Period

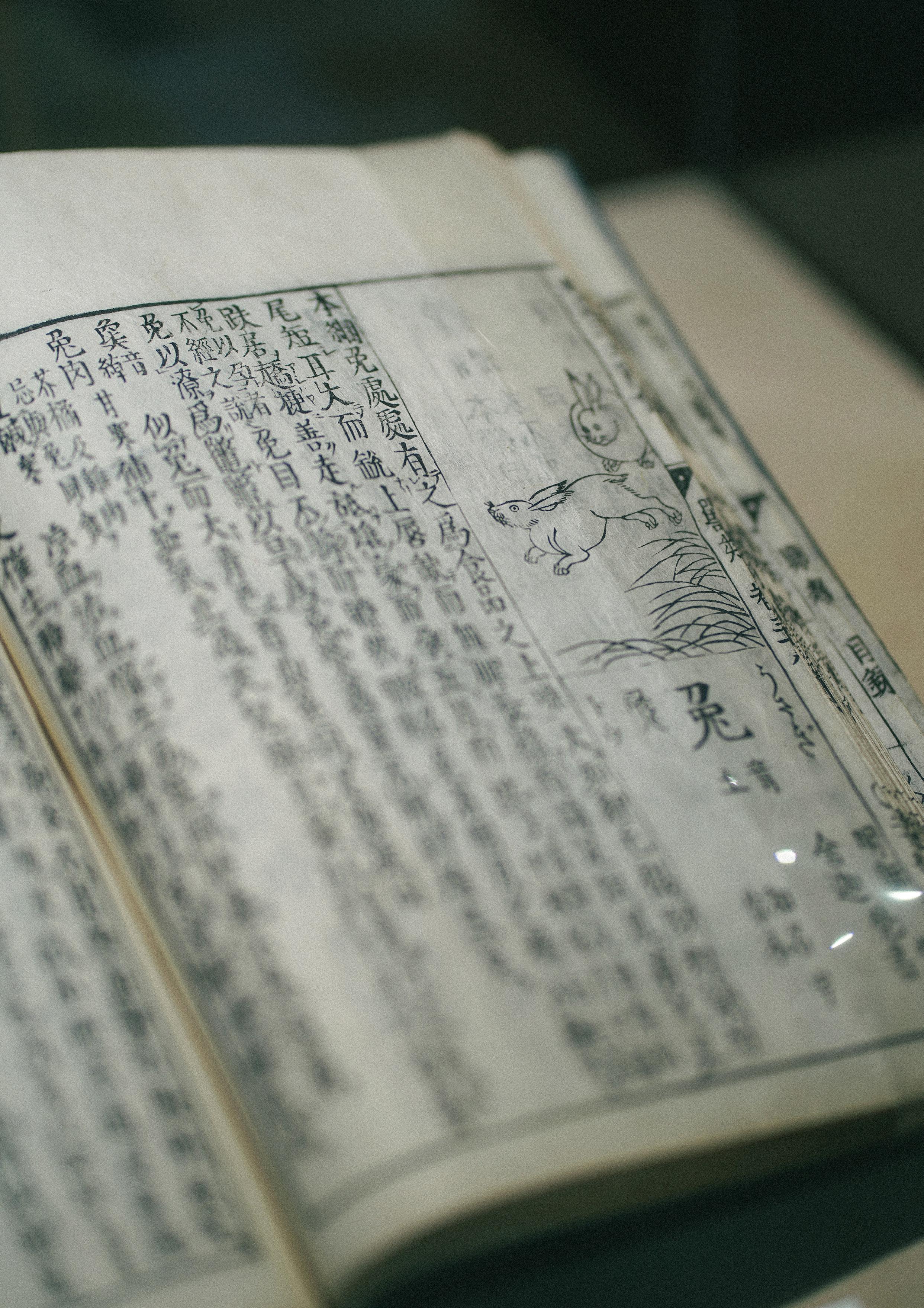

The Ise Monogatari ( 伊勢物語 ), or Tales of Ise , a collection of Japanese waka poems and stories from the Heian period (794–1185), appears in Japanese art history in different mediums and at various times. The Edo period is one of the times that Tales of Ise flourished the most in art history, not only in picture scrolls but in woodblock prints (called ukiyo-e), paintings, folding scrolls, and crafts. Hosoda Eishi ( 細田栄之 ), or Chōbunsai Eishi ( 鳥文斎栄之 ), created artwork with images from Tales of Ise . This paper focuses particularly on two works which depict courtesans in the Edo period reading or engaging with Tales of Ise: Seirō Bijin Rokkasen: Matsubaya Kisegawa ( 青楼美人六花仙 松葉屋喜瀬 川 ; Six Blossoming Masters of Beauty in Yoshiwara: The Courtesan Kisegawa of the Matsuba House) and Yume Miru Bijin ( 夢みる美人 ; Young Woman Dreaming of The Ise Stories). This paper also focuses on the woodblock print Seirō Bijin Rokkasen and analyses how visual representations of the Tales of Ise in other works of art function and contribute to different interpretations.

Throughout Japanese art history, Tales of Ise has been depicted and reimagined not only in picture books such as Ise Monogatari Emaki ( 伊勢物語絵巻 ), but also in motifs for works such as ‘Irises at Eight Bridges’ on folding screens by Ogata Kōrin (Fig. 2). The Ise stories became especially popular among

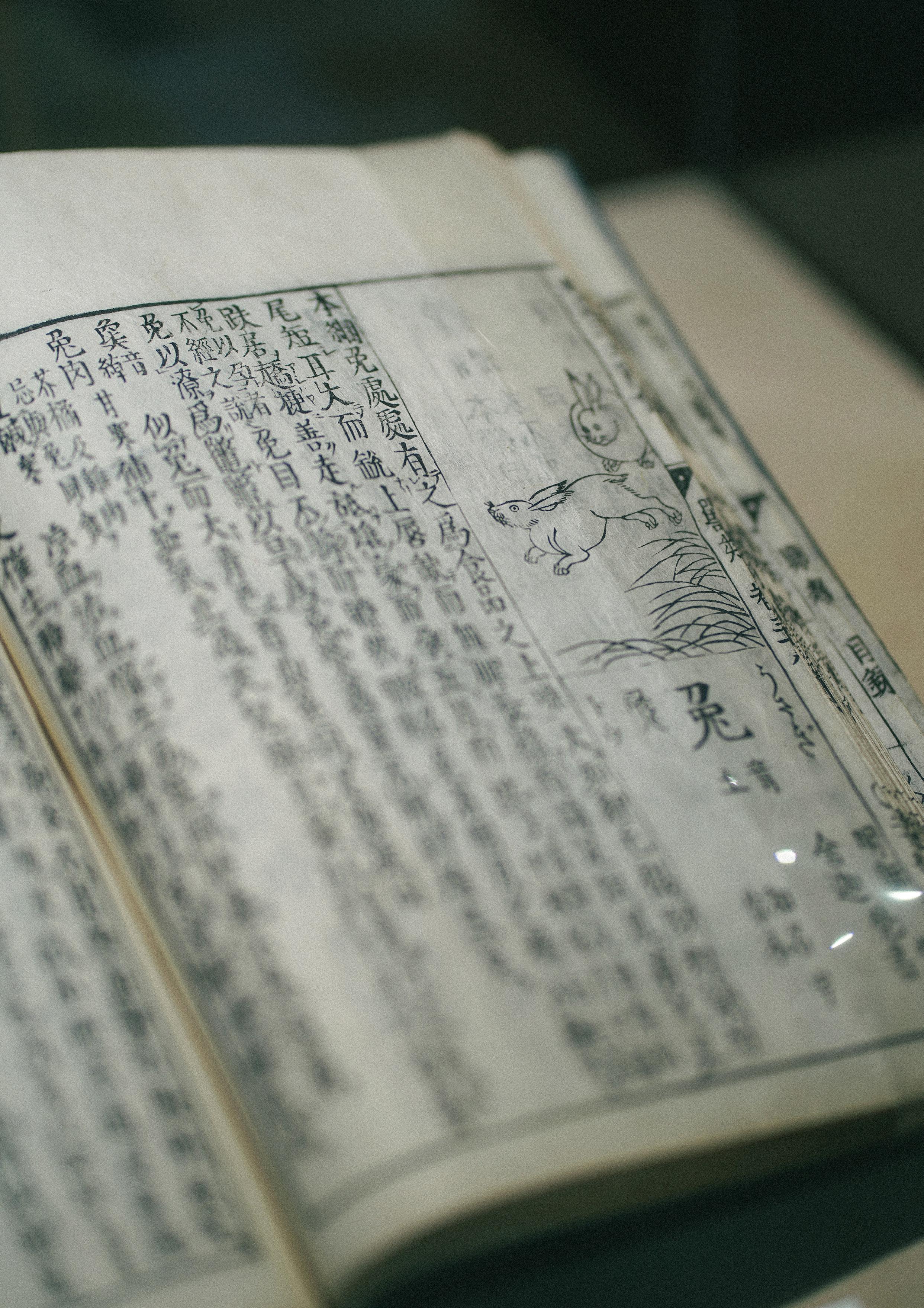

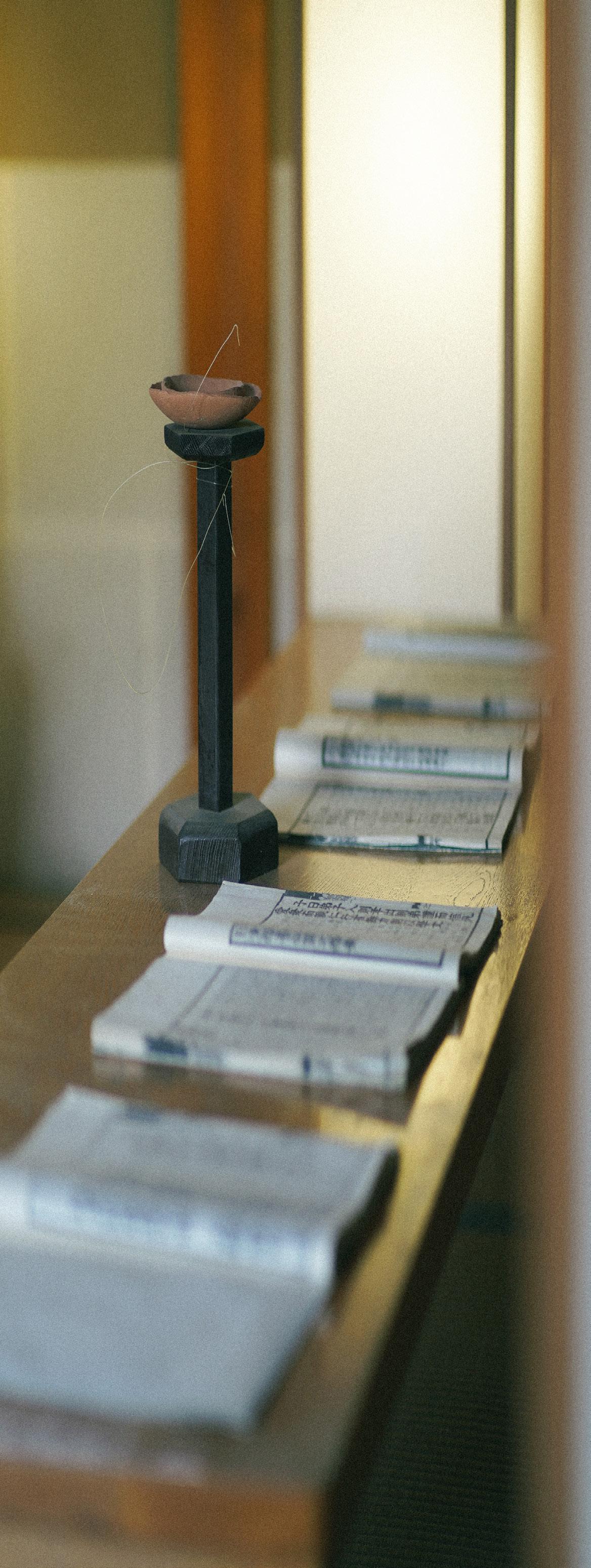

non-aristocratic society during the Edo period, thanks to the emergence of commercial publishers. As Peter Kornicki explains, The Tale of Genji and Tales of Ise came into the public domain in the 17 th century due to ‘the availability of copies and the publication of commentaries facilitating private reading.’

1 In 1608, Tales of Ise was published in letterpress printing books with pictures known as Saga Bon ( 嵯峨本 ), and after the mid-17 th century, many printing books that followed Saga Bon were circulated to broader audiences. These illustrated books helped immensely in expanding the readership, and can be seen in many published parodies such as Nise Monogatari ( 偽物語 ; The Tale of Fake ).

1 Peter F. Kornicki, ‘Unsuitable Books for Women? ’Genji Monogatari’ and‘Ise Monogatari’ in Late Seventeenth-Century Japan,’ Monumenta Nipponica 60, No. 2 (2005): 147-193.

39 HISTORY / LITERATURE

ARTS

Why, however, did Tales of Ise become so popular in the Edo period despite the many other classics available at the time? First, being a collection of short stories, rather than one long narrative, Tales of Ise is accessible and easy to read. Each short story gives a different impression and image to readers, such as the faithful wife in Kawachigoe ( 河内越 ) and escaping lovers in Akutagawa ( 芥川 ). Secondly, the Ise stories have a unique storytelling style, in which the main character is only referred to as Otoko ( 男 ; a man), although he is widely assumed to be Ariwara no Narihira ( 在原 業平 ). This method of storytelling, with its easy and accessible patterns of love, enables readers to project their own experiences and desires. Tales of Ise gives many figures of women in different situations relating to love. As these stories came to prevail in literature, plays, crafts, and paintings, the concepts that Tales of Ise carried started alienating themselves from the actual story, becoming secondary and semiotic.

Before analysing the artwork, this section briefly describes the artist, Hosoda Eishi, and his life. Although many ukiyo-e artists had the status of Chōnin ( 町人 ), or townspeople who were usually merchants and artisans in Edo society, Eishi was born into the samurai class. He studied under Kanō Michinobu ( 狩野 典信 ) and served the tenth Shogun Ieharu in his youth, but quit his apprenticeship after three years to study ukiyo-e. Eishi retired from service at the Shogunate, gave the inheritance to his son at the beginning of Kansei era, and started to flourish as both a painter and a ukiyo-e artist. He was distinctive since he had trained in painting before studying ukiyo-e printing, which was rare among ukiyo-e artists. His background and status as a samurai also made his work peculiar. When describing Eishi’s work, especially of women, many scholars use the term ‘elegance’ (in Japanese, jōhin) . The fact that he depicted only highclass courtesans in place of lower-status prostitutes, as well as his delicate and elegant touch, demonstrates that he always pursued his ideal image of women with intelligence and elegance. The women in Eishi’s work are beautiful and idealised, reflecting the standards of the wealthy and the intellectuals of the era. Eishi’s status as a samurai and his views on the ideal woman play an important part in analysing his works.

40

2 Joshua S. Mostow and Royall Tyler, trans., The Ise Stories , (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2010), 22.

Fig. 2 Ogata Kōrin, Irises at Yatsuhashi (Eight Bridges; Yatsuhashi-zu byōbu 八橋図屏風 ), after 1709. Pair of six-panel folding screens; ink and color on gold leaf on paper, 179.1 x 371.5 cm.

Seirō Bijin Rokkasen: Matsubaya Kisegawa

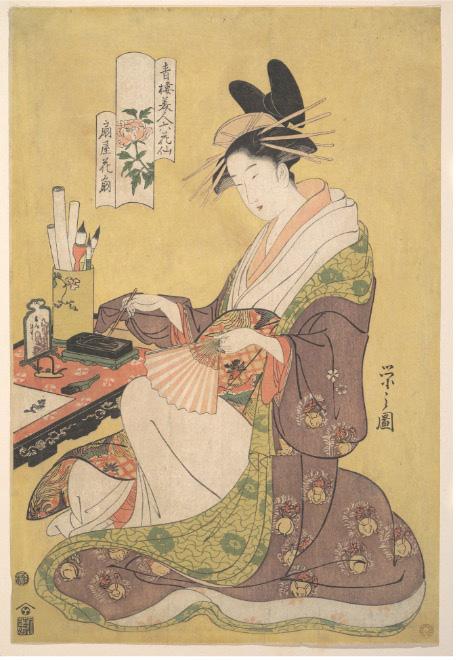

Seirō Bijin Rokkasen: Matsubaya Kisegawa is a ukiyo-e print created by Hosoda Eishi in the 1790s. (Fig. 1) This is a part of the series Seirō Bijin Rokkasen where Eishi depicted six courtesans who were famous at that time. This series shows high-ranking courtesans sitting inside and doing intellectual activities, such as reading, writing, or enjoying incense. For instance, Seirō Bijin Rokkasen: Ōgiya Hana ōgi ( 青楼美人六花仙 松葉屋喜瀬川 扇屋花扇 ) is another print in the series depicting Hana ōgi in the Ōgiya house. (Fig. 3) Hana ōgi is shown with luxurious writing equipment such as paper, brushes, and an inkstone case. She holds a brush and seems to be writing something. This could indicate that she had talent in calligraphy or poetry, or at least that she was educated, as high-ranking courtesans were expected to be. Hanaōgi wears layers of colourful and unique kimonos, such as uchikake ( 打掛 ), a long outer garment, adorned with rabbits. The writing desk and the brush holder are also decorative and lavish. These elaborate elements signify her high status as a courtesan. Other prints from the series similarly display courtesans as intelligent and elegant with embellishing garments, equipment, and books.

41

Fig. 3 Hosoda Eishi, Seirō Bijin Rokkasen: Ōgiya Hana ōgi (Six Blossoming Masters of Beauty in Yoshiwara: The Courtesan Hana ōgi of the Ōgiya House; 青楼美人六花仙 扇屋花扇 ), 1794. Woodblock print, ink and color on paper, 37 × 25.1 cm.

The courtesan Kisegawa in the Matsuba house is shown in this series to be reading the scrolls of Tales of Ise

Her outfit and the scrolls show her high status. Her hairstyle is called Shimada ( 島田 ) and is styled with more than ten kōgai ( 笄 ) and a comb, which adds to her prestige as a high-class courtesan. She wears an uchikake in a bicolour of beige and white fabric with a white pattern called hanagata matsu mon ( 花形松紋 ), in which pine leaves create the shape of a flower. She wears the uchikake on top of a kosode ( 小袖 ),

a short-sleeved kimono of pink fabric with a flower pattern, and several layers of white nagajuban ( 長襦袢 ), an undergarment of kimono. Her obi is green with a cloud pattern. The many layers of kimono, which was a trend in the late Edo period among high-ranking courtesans, make her look flamboyant.

The scroll which Kisegawa is reading is the fourth episode of Tales of Ise , commonly known as Nishi no tsui ( 西 の対 ; West Wing). The writings on the scroll are as follows:

Tales of Ise. Once upon a time, in the West Wing of the Palace of the Empress Dowager at the East of the fifth street,

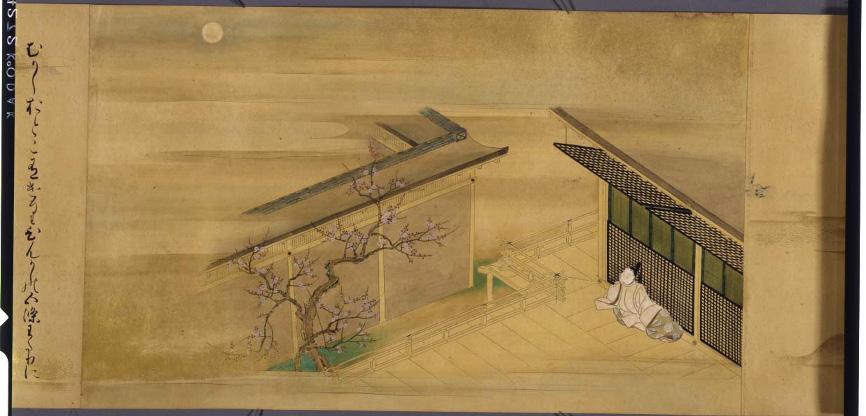

It shows the title Ise Monogatari ( Tales of Ise ), and then the opening text from the fourth chapter. One can also identify the chapter by the depiction typically used for Nishi no tsui . It is about a past love which still haunts the main character. Otoko, the man, has had a relationship with a woman of noble birth, who was living in the west wing of the palace of the empress dowager; however, the woman suddenly disappears, moving to a place ‘where one cannot usually go,’ indicating that she married an emperor. A year later, in the spring, when plum trees blossom, the man goes to the west wing and reads a poem:

月やあらぬ 春やむかしの 春 やあらぬ わが身ひとつは もと の身にして

Is this not the moon, this spring not as in those days springtime used to be— while I alone linger on, just what I have always been 2

42

伊勢物語 昔ひんかしの五条におほきさいの宮おはしましける西のたいに

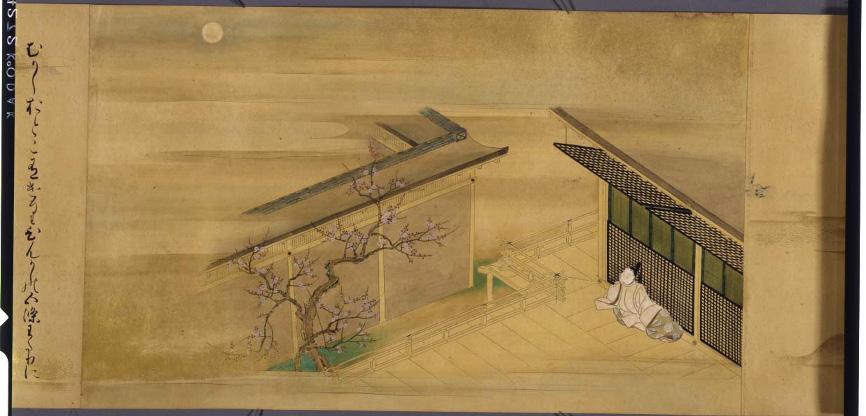

He grieves his past love by looking at a plum tree blooming and the moon. Paintings of this episode usually show a man doing just this from a veranda. (Fig. 4) The picture scroll within the print also has the image with this composition. The scroll of the Ise stories in the print is illustrated lavishly; the picture of the West Wing is decorated with gold clouds; silver paint is used to underlay the painting; the paper for text in the scrolls is decorated with autumn flowers in gold paint; and these de -

tailed depictions bring out the elegant taste, and show the courtesan as if she is the daughter of a samurai family. By examining the qualities of her clothes and scrolls, it is obvious that the print depicts a high-class courtesan who has access to lavish works of literature and has the knowledge to read and enjoy them.

43

Fig. 4 Sumiyoshi Jokei. Ise Monogatari emaki (The picture scrolls of the Tale of Ise , 伊勢物語絵巻 ), 17 th century. Scroll.

Kisegawa gazes at the scroll in her left hand. Her head is tilted toward it, while the left side of her kimono drapes over her right hand, giving viewers the impression that she is relaxed and engrossed in the story. The viewers’ eyes first go to her face, and then down to the scroll, especially the man, who looks toward the plum tree and the moon. Through the eye of intellectuals at that time, one could identify the composition of the west wing scene immediately, as well as the poem of the moon and the spring by Ariwara no Narihira. It gives the impression of loneliness, longing, and waiting. The art historian Nakamachi suggests that the image of the west wing describes the courtesan’s feelings, namely, ‘thinking about her lover and losing herself in thought’ or ‘soaking in the sadness of her lover’s absence.’ 3 One could also assume that the courtesan is projecting herself onto the woman about whom the man in the scroll is thinking. The woman in the fourth episode is suggested to have become the emperor’s wife and lives in a place where ‘usual people’ cannot go. The courtesan imposes the image of the Imperial Palace onto Yoshiwara

as an inescapable place. This image of a man on the veranda became symbolic in the Edo period, not only as this composition appeared in the scrolls but also as artists in the period recreated the composition. When Eishi produced the woodblock print, intellectuals were able to understand the meaning of the composition immediately. Although Eishi gave more hints to viewers by showing the title and the opening text of the fourth episode, the image was more powerful and immediately perceivable by the eyes. The picture of the man on the veranda with a plum tree becomes the secondary image in this print and works semiotically to create another layer of meaning in the artwork, namely, the loneliness and longing of the courtesan.

44

3 Nakamachi, ‘Ukiyo-e ga kioku shita ‘Ise Monogatari-e,’’173.

This is one possible reading of this print, for the knowledgeable, intellectual audience. Now I move on to consider the audience of a lower status in the same society, since this is a ukiyo-e print and was accessible to the broader consumer. Analysing the composition of this print, even if one does not know the story of Tales of Ise , the eye goes to the face of Kisagawa, and down to the back of the male figure. The visual structure of the courtesan looking at the back of a man evokes the concept of a woman’s unrequited love for him, although the position is the opposite in the story of the west wing. Kisegawa gazes at a man in the scroll, the man looks beyond the work, and the viewers gaze at the courtesan. I argue that the composition of the gaze from the courtesan to the man still satisfies viewers with less knowledge of Tales of Ise . Whether viewers had the knowledge of the west wing from Tales of Ise or not, this print satisfied the desires of the consumers, as Eishi intended. First, Eishi succeeded in creating his ideal image of the courtesan with intelligence and elegance by both creating a visually exquisite look and by using Tales of Ise . Chino Kaori argues that Tales of Ise was written from the perspective of men in Kyoto during the Heian period; later, in the Edo period, it conveyed these values and presented them to viewers as something that still existed in their own time. 4

By using the Ise stories in the print, Eishi not only created the idealised image of intelligent courtesans but also accorded to them a place within Japan’s cultural and traditional history, from the Heian period on, demonstrating the legitimacy of the courtesan as a cultural and traditional woman. At the same time, Tales of Ise is a collection of love stories that presents different images of love and women in love. The art historian Okuhira Shunroku argues that brothels were the place where people consumed love as a game, and Tales of Ise was promoted broadly as a collection of patterns for love. 5 It was a perfect tool to indicate love associated with the courtesans. Secondly, even if one does not understand the actual story of the west wing, the composition of the work, in which the courtesan longs for a man, would still satisfy the audience. The luxurious scrolls in the print would also inspire admiration from viewers of lower status since they did not have access to such scrolls. The important thing, however, is that this artwork expressed men’s desire for the courtesan to be in love with them, and not the actual desire that courtesans possessed. The archetypes of the courtesan longing for a man like that of the west wing, and the courtesan grieving her loneliness, as is evoked by the secondary image, were both created by the male artist for a male audience.

45

4 Chino, ‘Ise-Monogatari no Kaiga.’

5 Okuhira, ‘Nokusaki no bijin,’ 681.

The Image of Tales of Ise as Reinforcing Tradition and Culture

Having analysed Seirō Bijin Rokkasen: Matsubaya Kitagawa , this study has identified three implications regarding the use of the secondary image of Tales of Ise in artworks by Hosoda Eishi. First, the secondary image of the Ise stories helped create an intellectual, traditional, and cultural image of courtesans. Eishi designed and created his ideal image of high-ranking women in pleasure quarters who were beautiful, refined, and smart. His creation of such an image was done, on one hand, by painting flamboyant kimonos, lavish equipment or books, and by portraying prostitutes’ faces in an elegant way. On the other hand, Eishi effectively used Tales of Ise and other equipment such as incense or calligraphy sets to signify their intelligence, as was required of high-ranking courtesans. Scholarship has pointed out that works of art depicting The Tale of Genji in the Muromachi period were created for men and were especially propagated by samurai to demonstrate their political power, in which the artwork of Genji was a means to show

their refinement and understanding of cultural traditions and to come closer to being a conqueror of traditional Japanese culture. Someya Miho pointed out the adoption of traditional iconography of Genji by Eishi, in which he used the traditional iconography of The Tale of Genji in his work F ū ry ū Yatsushi Genji , thanks to his experience in studying under the Kanō school. 6

Tales of Ise was also utilised as a tool to represent a person as traditional and culturally highbrow. The allusion to established Ise iconography in art was one way to create associations with Heian-period courtly elegance for Edo-period audiences. It is possible that Eishi's status as a samurai influenced his decision to feature Tales of Ise to indicate intelligence in his art. Secondly, images of the Ise stories in the Edo period became secondary and semiotic by numerous re-creations in paintings and prints, and such images were used to add layers of meaning to the work. Eishi placed the image of the west wing in Seirō Bijin Rokkasen: Matsubaya Kisega -

6 Someya Miho 染谷美穂 , “Ukiyo-e shi Chōbunsai Eishi no Bijinga: Kojinteki Yōshiki no Keisei to Dokusō teki Hyogen no Mosaku” 浮世絵師・鳥文斎栄 之の美人画 個人様式の形成と独創的表

現の模索 [The Ukiyo-e Artist Chobunsai Eishi's Bijin-ga (Beauty Prints) : The Establishment of His Individual Style and An Exploration of His Creative Expression], Bijutsushi 美術史 [Art History] 65(1), (October 2015) 112.

46

wa to imply the courtesan’s longing and desire, as Otoko in the fourth episode of the Ise recalls his lover who supposedly married the emperor. Third, these images were produced to fulfil the desires of men, especially the intellectual customers of Eishi. Much of Eishi’s artwork required a profound knowledge of the classics, and these were most likely created for men of intellect and culture who enjoyed high-ranking pleasure quarters. Placing the image of classics

such as Tales of Ise projects the desire of men for courtesans to lament their fate in the brothels, to dream about their lover and escape, while the men themselves confined real courtesans to the pleasure quarter. Hosoda Eishi employed the secondary image of the Ise to construct his ideal woman and to give layered meaning that transcended the desires of his intellectual customers and audience.

Suggested Readings

Chino, Kaori 千野香織 . ‘Ise-Monogatari no Kaiga—Dentou to Bunka wo Yobiyoseru Sōchi’『伊勢物語』の絵画 —「伝統」と「文化」を呼び寄せる装置 [The Paintings of The Tale of Ise: A Machine to Bring in ‘Tradition’ and ‘Culture’]. In Chino Kaori Chosaku Shu 千野香織著作集 [Collections of Writing by Chino Kaori]. 961-980. Tokyo: Brucke, 2010.

Clark, Timothy. ‘Mitate-e: Some Thoughts, and a Summary of Recent Writings.’ Impressions , no 19. (1997): 6-27

Mostow, Joshua S., and Royall Tyler, trans. The Ise Stories: Ise Monogatari . Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2010.

Okuhira, Shunroku 奥平俊六 . ‘Ensaki no Bijin: Kanbun Bizin-zu no Ichi Sugata Katachi wo Megutte’ 縁先の美人 : 寛文美人図の一姿型をめぐって[The Beauty at Veranda: Concerning a Figure of The Kanbun Master’s Portrait of Beauty]. In Nihon Kaigashi no Kenkyū 日本絵画史の研究 [Research on History of Japanese Paintings], edited by Yamane Yū zo 山根有三 , 647-690. Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan, 1989.

Someya Miho 染谷美穂 , ‘Ukiyo-e shi Chōbunsai Eishi no Bijinga: Kojinteki Yōshiki no Keisei to Dokusō teki Hyogen no Mosaku’ 浮世絵師・鳥文斎栄之の美人画 個人様式 の形 成と独創的表現の模索 [The Ukiyo-e Artist Chobunsai Eishi's Bijin-ga (Beauty Prints): The Establishment of His Individual Style and An Exploration of His Creative Expression], Bijutsushi 美術史 [Art History] no. 65(1), (October 2015): 96-116.

47

It's Not That Bad

Dominique Jenkins

So, you’ve decided to study Japanese and have just discovered that there are three writing systems. Great! You breeze through hiragana and katakana, but then you get to kanji. Kanji has been ‒ and will most likely continue to be ‒ one of the main challenges for Japanese learners. However, if you are reading this article, then you are either struggling to learn kanji and want to get better at it, or you’re a weirdo like me who enjoys torturing yourself and are actively seeking to know more about them. Either way, this article should hopefully answer some of your pressing questions about kanji, why they are so strange at times, and how you can learn them more effectively. By the end, you should realise that learning kanji is actually not that bad.

Brief History

Kanji haven’t always looked the way they do now, nor did they originate from Japan. Their use can be traced way back to ancient China, namely the Shang Dynasty (1600–1046 BCE). When the ancient Chinese wanted to communicate with the gods, they would poke a metal rod on the underside of a turtle's shell, apply a heat source, and then a scribe would record the cracks that appeared, along with the accompanying result. These cracks were said to be the answers to the topic of divination at that time; as well as messages from the gods. The characters that appear in these records are known as ‘oracle bone script’ ( kōkotsu moji , 甲骨文字 ).

In the following Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE), people discovered that the symbol-marked shells used throughout the Shang Dynasty could be used to cre -

ate a writing system through which they could communicate. The Zhou people thereafter took the oracle bone script and developed it further. Through this whole process of kanji development in the Shang and Zhou, we see the creation of many ‘ideograms’ ( hyōi moji 表意 文字 ), which are characters that symbolise an idea, thing, or concept without indicating how it is pronounced. However, since there wasn’t any standard for how the characters should be written, people would write them in a variety of ways, causing quite a bit of confusion.

49 HISTORY KANJI

EDUCATION

After the Zhou Dynasty, there was a time of turmoil known as the Warring States period. This was swiftly followed by the Qin Dynasty (221–206 BCE) after the state of Qin conquered all of its rivals, thus unifying China. With this unification came the standardisation of the written scripts created during the Zhou Dynasty. This is where we start to see characters that resemble those currently used, but they had more strokes and were slightly wavier. This script, developed during the Qin Dynasty, is called ‘small seal script’ ( shōten 小篆 ).

From this point on, the characters went through many iterations, where simplified and modified types of script were developed in order to increase writing speed and precision. Around the end of the 4 th century CE and into the 5th century CE, those characters were brought over to Japan via the Korean peninsula. However, they didn’t come to Japan all at once; there was a steady flow of kanji from the 4 th century up until the Edo period (1603–1867).

We will get more into this later, but first, have you noticed that some kanji have more than one Chinese reading ( on’yomi , 音読み )? This is because over the many years that Japan and China interacted with one another, as the Chinese dynasties changed, the readings of certain kanji changed too. For example, if you look up the kanji 明 in the dictionary, you will see that it has three different on’yomi, namely, メイ ( mei ), ミ ョウ ( myou ) and ミン ( min ). Each of these three readings were introduced to the Japanese language at different times in history. The reason for this simply comes down to differences in when they were brought to Japan, and by whom. The history of kanji runs deep, and we have just barely scratched the surface. Nevertheless, I hope that you now have a better understanding of how kanji came to be as we know them today.

50

However, kanji also have another, more mythical, origin story! As the legend goes, they were created by a single man named Sōketsu (Ch. Cangjie 蒼頡 2667–2596 BCE) who was said to have had four eyes and was purported to be the official historian of the Yellow Emperor. Since he was blessed with four eyes, he had amazing observation skills

and was able to tell the differences between animals solely from their footprints. He realised that he could record the shapes of the footprints in order to share his knowledge with the people, and thus kanji was born. It is said that when he created kanji, grain fell from the heavens and demons wept all night long.

The Absolute State of Kanji Ateji , Jukujikun , and Gikun

Kanji, to put it simply, are immense. There are actually over 50,000 kanji in total, but in reality, you only need to know 2136 kanji to survive in Japan. 1 These 2136 kanji are known as the ‘daily use kanji ( jōyō kanji 常用漢字 )’. Each kanji has its own distinct meaning, with most having a Chinese reading ( on’yomi ) and a Japanese reading ( kun’yomi ), and some even having multiple of each. However, there is no need to know all the readings for every kanji, as some are used less often than others.

Kanji usually make sense. As long as you know the readings of a kanji, you can understand it without any problem; but things are not always so simple. For the most part, if you know the readings of a kanji, nine times out of ten you can guess how it is read when it is paired up with another one that you know. However, if you have been studying kanji for any amount of time, you may have noticed something strange about some of the words you have come across.

For example, 大人

The readings for the two characters 大 and 人 are:

大:ダイ2 ( dai ), タイ ( tai ), おお ( ō ), おおきい ( ōkii ), おおいに ( ōini )

人:ジン ( jin ), ニン ( nin ), ひと ( hito ), り ( ri ), と ( to )

However, 大人 is pronounced おとな (otona), which means adult. Another common example is 今日 , which means today:

今:コン ( kon ), キン ( kin ), いま ( ima )

日:二チ ( nichi ), ジツ ( jitsu ), ひ ( hi ), か ( ka ), び ( bi )

But it is pronounced きょう( kyо̄ ) 3 .

As you can see, knowing the readings of the individual kanji does not guarantee being able to guess the reading of a word. A few more examples would be:

風邪 ( kaze , common cold), 竹刀 ( shinai , bamboo sword), 時雨 ( shigure , rain shower in late autumn), and 相撲 ( sumо̄ , sumo).

1 Although you only need the 2136 kanji to survive/ read a newspaper in Japan, there are times when you will come across kanji outside of that list, so just be aware! Also, Additionally, you don’t necessarily need to know all 2136 kanji. Knowing just half of them those would suffice; you might struggle a bit, but you’ll survive.

52

You also have words like:

亜米利加 ( amerika , America),

夜露死苦 ( yoroshiku , best regards; please treat me favourably),

滅茶苦茶 ( mechakucha , really; absurd).

These types of words are known as ateji ( 当て字 ) and they are words that do not abide by the original meaning, or reading, of a kanji. You can break down ateji into two categories:

① words that prioritise the kanji’s reading ( ON-yomi ), and

② words that prioritise the kanji’s meaning.

The first are your standard ateji , whilst the second are known as jukujikun ( 熟字訓 ). These are the ones that ignore the original readings of the kanji in favour of the meanings. For the previously mentioned 大人 ( otona ), you have the kanji for ‘big’ and ‘person’ brought together, despite their readings, to represent a word that already existed in Japanese – otona – because it just makes sense. 今日 ( kyо̄ ) is a combination of the kanji for ‘now’ and ’day’, and so you get ‘today’. These are the ones that you will

get wrong without fail if you do not already know the readings beforehand, so they can be quite tricky. However, don’t you find them fascinating? It does make life as a Japanese language learner that much harder when you spend so much time memorising the readings of various kanji only to find out that there are words that completely ignore them, but you can just think of them as slight irregularities. We have plenty of those in English, especially when it comes to pronunciation and spelling.

2 In the Japanese language, the way to recognise the difference between an on'yomi and kun'yomi is that on'yomi readings are written in katakana, whereas kun'yomi readings are written in hiragana.

3 今日 ( kyо̄ ) can also be read as こ んにち ( konnichi ), which is what you would expect if you were going by normal kanji reading rules. However the meaning changes. Konnichi has the meaning of ‘recently’ or ‘these days.’

Some examples of jukujikun ( 熟字訓 ) include:

神楽 ( kagura , ancient Shinto music and dancing),

田舎 ( inaka , countryside),

可愛い ( kawaii , cute),

案山子 ( kakashi , scarecrow),

雑魚 ( zako , small fry, a nobody).

53

The last thing I would like to mention are gikun ( 義訓 ). They are very similar to jukujikun ( 熟字訓 ) but are used in a much wider context. Sometimes considered to be errors when used, they are typically seen in manga, poetry, songs, and various other mediums. Usually, the author or songwriter will add their own reading –typically in the form of furigana (phonetic aids) – to a word (kanji) that isn’t far away from its original meaning and also makes sense in the context of the sentence. For example,

Kanji Original Reading

せいめい (seimei)

ふうん (fuun)

運命 , which is pronounced unmei and quite often read as sadame. Both unmei and sadame mean the same thing (fate; destiny) but sadame is usually written with this kanji 定め . Thus, they took the reading of another word/kanji that has a similar meaning and stuck it on 運命 If you like going to karaoke, you will notice as you sing Japanese songs that above 運命 they have the reading さだ め ( sadame ). It would look a little something like this:

Gikun Reading Original Meaning Gikun Meaning Usage

いのち (inochi)

ハードラック (hādorakku)

Misfortune, bad luck

ジョジョーその血の運 命 (さだめ ) 〜

One of the openings from the anime JoJo’s Bizzare Adventure

事故る奴は不運(ハー ドラック)と踊(ダンス) っちゃまったんだよ

This is a line from the manga ‘疾風伝 説 特攻の拓’

ぎゅうにゅう (gyūnyū)

ミルク (miruku)

でんのうくう

かん (dennо̄ kūkan)

サイバースペ ース

(saibā supeisu)

牛乳食パン専門店 み るく Milk

Shops that specialise in milk and bread

Networking terminology

54

生命 不運 牛乳 電脳

空間

Life

Milk

Life

Milk

Cyberspace

Hard luck, misfortune

Cyberspace

Kanji Original Reading

Gikun Reading Original Meaning

There are a lot of kanji and you can learn to read all of them without any issue with a bit of hard work and dedication. However, you have these ateji (当 て字 ), jukujikun ( 熟字訓 ), and gikun ( 義訓 ) that you will just have to memorise as you come across them. There are quite a few, but definitely not enough to warrant panicking over. You just have to take it one kanji at a time.

55

チョウ、こえる

さむい