DELICIOUS RECIPE INSIDE!

Washington's produce pipeline to Mexico

El Salvador, meet South Seattle

What is the right way to pick an apple?

Exporting wheat and importing coffee beans

magazine

magazine

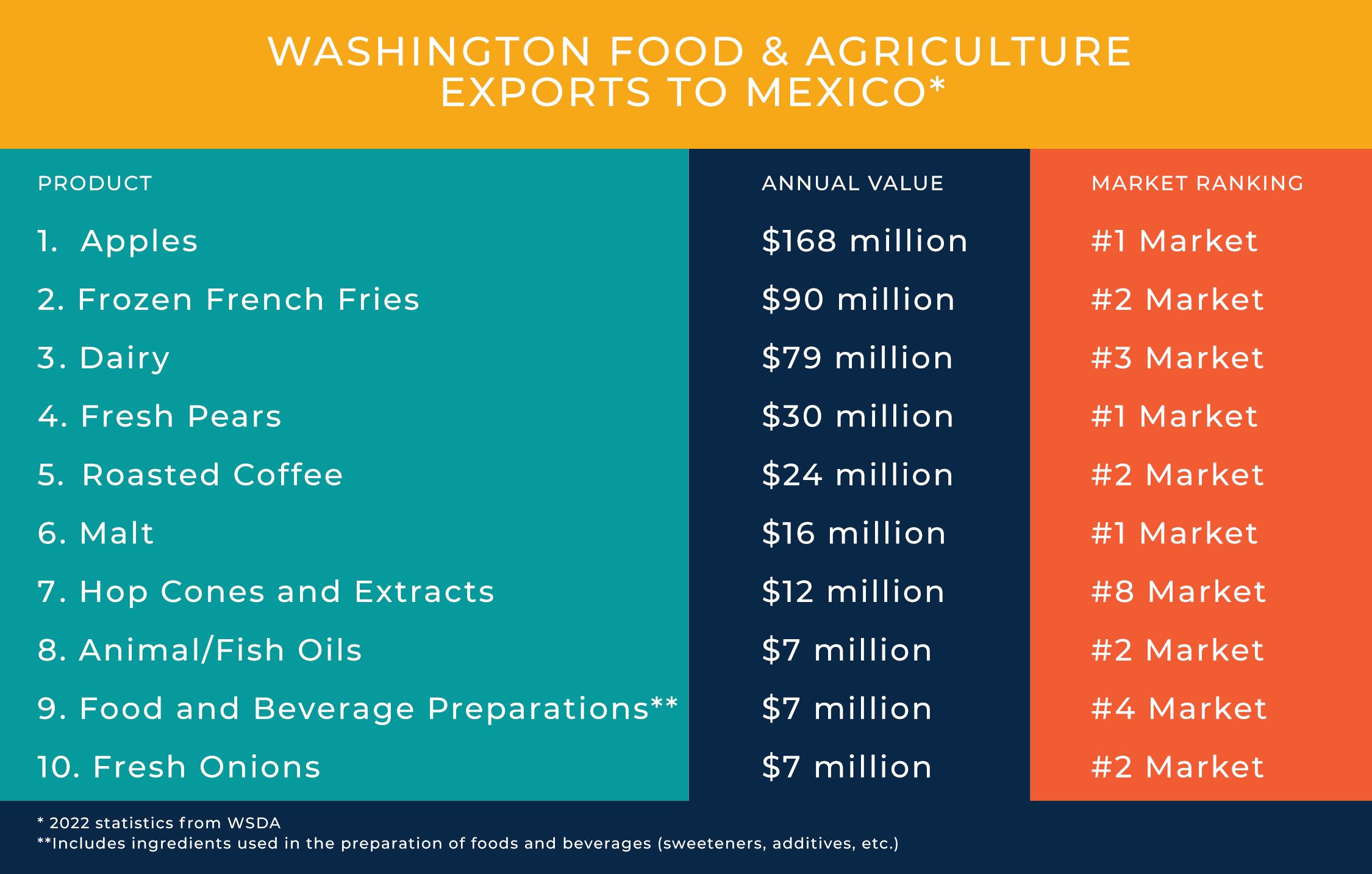

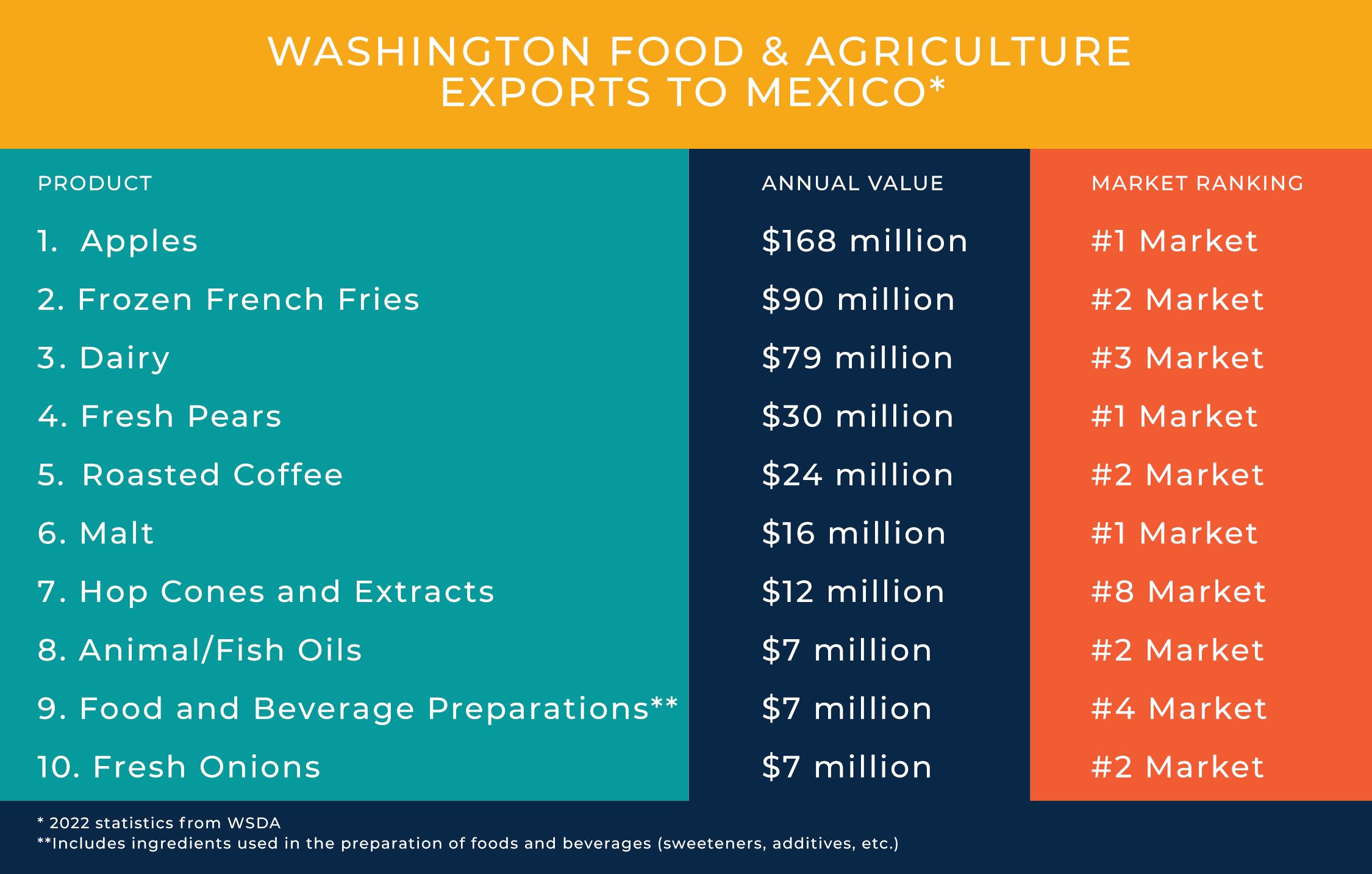

Grocery stores throughout Mexico depend on Washington's natural abundance for their papas, cerveza, manzanas, and more.

IN A BRIGHT, SPACIOUS GROCERY STORE in Mexico City, aisles of locally grown fruits, fresh fish, and dried peppers open up to a familiar sight for Washingtonians: rows of apples, cherries, and pears grown in Washington state. It’s not surprising to find so much Washington produce here, given that Washington is a major exporter of everything from potatoes to hops, but it can be hard to imagine how, exactly, a Golden Delicious apple travels from a Northwest farm to a grocery cart in Mexico City.

First, of course, we start with the farmers. Washington apple farmers export about 30% of their crops worldwide, with a large percentage going to Mexican consumers. Potato farmers export more than 70% of their potatoes, mostly in the form of frozen french fries, and cherry farmers export about 25%.

On a visit to Mexico City, the Washington Grown team headed to the grocery store to see what Washington goodies they could find. Mark Hammer, a potato farmer and member of the Washington Potato Commission, scanned the freezer section and spotted

several bags of frozen french fries made by companies he supplies.

“I feel a little bit at home seeing the product here,” he said. “As a grower, it’s super rewarding to see our product down here in Mexico and see that the popularity of french fries is blowing up across the country.”

Derek Sandison, the director of the Washington State Department of Agriculture (WSDA), added that you’ll find Washington-grown french fries all over the world.

“Chances are if you go into a McDonald's restaurant in Japan, for example,” he said, “the french fry you’re eating is from Washington!”

Washington farmers export their goods through wholesale traders, who source produce from all over the world to import into their country. Ernesto Cardona, the fourth-generation CEO of Austral Trading in Mexico City, said his company imports more than 45 kinds of apples and about 15 varieties of pears from Washington state to Mexico.

WASHINGTON GROWN MAGAZINE MARCH 2024 3

“The fruit from Washington is the best fruit because of the flavor, because you can store it for a while, and because of the varieties,” he said, adding that for pears and apples, “consumption is increasing a lot in Mexico because we’re looking for the best for our bodies and for our health.”

After the produce is imported, it’s unloaded from the trucks into wholesale markets like Mexico City’s Central de Abasto, where retailers source the food they sell in their shops.

Juan Carlos Moreira, the Mexican representative for Washington apples and cherries, looked up at boxes of Golden Delicious apples stacked high at Central de Abasto. He said retailers will buy anywhere from a few boxes to several pallets at a time.

“People come to these warehouses every single day —

imagine that,” he said. “You can have a truckload with apples here in less than a week.”

Since Mexico isn’t a self-sufficient producer of apples, he said, the country needs to import them from places like Washington, whose apples are popular with Mexicans because of the uniform size, beautiful color, and great crunch. “Washington apples are the best match.”

From the wholesale market, the fruit makes its way to grocery store shelves, where customers often cannot wait to get a taste. In the cherry section at the Mexico City store, Moreira said that Mexican customers get especially excited for Washington cherry season.

“Washington cherries have a fantastic explosion of flavor,” he said. “They have a larger size (than other competitors' cherries), and the color is so intense. Since

4 WASHINGTON GROWN MAGAZINE MARCH 2024

(Right) Washington Grown host Kristi Gorenson tours a grocery store in Mexico City with Derek Sandison (center) and Juan Carlos Moreira.

it’s a very seasonal product, we take the circus approach, where we say, ‘The circus is coming! The circus is coming!’ So, ‘Northwest cherries are coming — you will see them in your retail stores very soon!’”

In another aisle of the store, Sandison of the WSDA browsed shelves of locally brewed beer, which he said Mexico exports all around the world.

“They use a lot of Washington hops in the production of the craft brews down here,” Sandison said, adding that 70 to 80% of the hops grown in the U.S. are from Washington state, specifically the Yakima Valley. “Our hops make good beer — and the world knows it.”

Cardona, of Austral Trading, said he loves to visit Washington and see all the advances that are being made in every part of the export process.

“I feel good because I see how the growers and the packers are developing the infrastructure and all the things to increase the quality, the volume,” he said. “It's amazing.”

WASHINGTON GROWN MAGAZINE MARCH 2024 5

ROAM COFFEE

HARRINGTON

6 WASHINGTON GROWN MAGAZINE MARCH 2024

&

beans grains not-so-local

Growing wheat has taught Shelley Quigley everything she needs to know about life – and about roasting coffee.

In a nondescript barn surrounded by wheat fields in Eastern Washington, a fifth-generation wheat farmer is producing more than just grain; Shelley Quigley is roasting high-quality coffee to supply local coffee shops. And though coffee may be synonymous with the Pacific Northwest, in order to get here, the beans have to come from somewhere else.

“That's one of the No. 1 questions I get when I talk about the roastery being on our farm outside Harrington,” says Quigley, owner of Roam Coffee. “People ask, ‘How do you grow the coffee?’ And it's a perfectly reasonable question, but coffee only grows in the equatorial belt between the Tropic of Cancer and Capricorn. So inherently for coffee to get in my cup, it has had to travel, or ‘roam,’ around from all over the world to get here.”

Though the Quigley farmers don’t grow coffee, they know a few things about growing crops. Shelley is a fifth-generation wheat farmer who lives and works on a family farm that has grown wheat and barley for more than 135 years. In

local WASHINGTON GROWN MAGAZINE MARCH 2024 7

addition to her coffee-related work responsibilities, she and her husband also run the familiar farming gamut: planting, tending, and harvesting the crops, as well as keeping the animals alive.

“One of the reasons that I wanted to have the roastery here on the farm was to create that connection between farmers and farming and the finished product — in this case, coffee,” Quigley says, gesturing toward the coffee roaster working behind her. “I wanted to help people recognize that this magical elixir that shows up in our cups was probably grown by a family farmer, probably someone who's been doing it for generations, who cares as much about the quality of that bean as I do about growing high-quality grain.”

Coffee beans are unique from place to place, and they are known for a “terroir” effect more familiar in grapes and wine. They’re affected by soil conditions, climate, elevation, and a myriad of other factors. Just like at family grain farms here in Washington, families in Brazil and Papua New Guinea put a lot of effort into producing a crop that reflects their home. When Quigley places an order for a shipment of beans from Colombia, it’s one farmer buying from another farmer. Ultimately, those farm-to-table connections help us better understand our food — and our coffee.

Quigley’s passion for educating people bubbles right under the surface of every conversation. She eagerly welcomes guests into the roastery for events throughout the year, excitedly explaining the finer details of the roasting process, discussing differences between the beans from Colombia vs. Zambia, and passionately advocating for farmers around the world.

“There are so few people that have a first-person connection with farmers these days,” she says. “But from my standpoint, the people that care the most about the ground are the people that are working it

and have worked it for generations. I have two sons that will be sixth-generation farmers, if they decide to move into farming — and I don't want to ruin it for them.”

Quigley smiles as she thinks about her sixth-generation future farmers.

“I have done a lot of things wrong. If it can be broken, I've broken it. But it’s the same in farming and roasting and running a business — being able to bounce back from unexpected things. I hope my children learn how to do that. We’ve been doing that on this farm for many generations.”

8 WASHINGTON GROWN MAGAZINE MARCH 2024

"Their family came to Red Mountain on a coin flip. But their success here has nothing to do with chance."

Read more at wagrown.com

"Her parents were farmworkers. Now she owns the farm."

Read more at wagrown.com

"We've got a responsibility to take care of it for future generations."

Read more at wagrown.com

Watch the show online or on your local station

KSPS (Spokane)

Mondays at 7:00 pm and Saturdays at 4:30 pm ksps.org/schedule/

KWSU (Pullman)

Fridays at 6:00 pm nwpb.org/tv-schedules/

KTNW (Richland)

Saturdays at 1:00 pm nwpb.org/tv-schedules

KBTC (Seattle/Tacoma)

Saturdays at 6:30 am and 3:00 pm kbtc.org/tv-schedule/

KIMA (Yakima)/KEPR (Pasco)/KLEW (Lewiston)

Saturdays at 5:00 pm kimatv.com/station/schedule / keprtv.com/station/schedule klewtv.com/station/schedule

KIRO (Seattle)

Saturdays at 7:30 am and Mondays at 2:30 pm or livestream Saturdays at 2:30 pm on kiro7.com kiro7.com

NCW Life Channel (Wenatchee)

Check local listings ncwlife.com

RFD-TV

Thursdays at 12:30 pm and Fridays at 9:00 pm (Pacific) rfdtv.com/

*Times/schedules subject to change based upon network schedule. Check station programming to confirm air times.

Find more great stories at wagrown.com

wagrown.com @wagrowntv

What does it take to grow high-quality apples? Washington's apple growers are some of the world's leading experts in that field.

Almost Candy

You might already know that Washington grows more than 30 varieties of apples, and that our rich soil, plentiful water, and ideal growing conditions make the apples delicious, crunchy, and flavorful. Washington farmers export 30% of their apples worldwide, and according to Steve Smith, the director of marketing for Washington Fruit Growers, these apples are “regarded as a premium product all over the world.”

You might not be aware, however, of how many decisions farmers make long before the apples end up in stores, locally or worldwide, including what sizes to grow, how to tell if the apple is ripe, and why color matters (and it’s not because of taste!). Here are some fun facts we learned from Smith as he took us on a tour of a Cosmic Crisp orchard.

How does the apple’s color affect its sales?

According to Smith, shoppers are often drawn to the reddest apples, and those sell the best. Fruit growers refer to them as high-colored apples, and at the end of the day, once shoppers have bought apples off the shelf, the lower-colored, duller apples are generally left over.

Does the same kind of apple sell well everywhere?

It varies by market and country. Some countries like Vietnam prefer a smaller apple, while others like China import larger varieties. “Markets like Mexico, they buy the whole tree: high color, low color, large, small,” says Smith. Fortunately, Washington has plenty of varieties to choose from.

What is the correct way to pick an apple?

“Set your finger right on the top of the stem where it meets the tree,” said Smith, cupping an apple in his hand. “Press and turn it up, and that will pop it right off.”

How do farmers know when an apple is ready to pick?

As apples mature, they convert starch into sugar. Farmers can measure this conversion at different stages, and it will tell them when it’s the perfect time to start harvesting each variety.

How do they measure the sugar conversion?

Farmers do an iodine test on the apples to see how much conversion has happened — and, therefore, how mature the apples are. First, they cut the apples in half. Then they spray them with an iodine solution, which turns the starches black and the sugars white.

Are apples only harvested when they’re mature?

Different varieties are harvested at different points in their sugar conversion; for example, Cosmic Crisp apples are very starchy, and they are harvested before they’re fully mature and kept in storage for a few months after picking, so the starches can continue to convert to sugars. Others, like Fujis, are harvested when they’re more mature.

Why is there a random crabapple tree among the Cosmic Crisp apples?

In general, apples need two different kinds of pollen to fertilize the bud and produce fruit. The purpose of the crabapple tree is to crosspollinate the Cosmic Crisp apples.

10 WASHINGTON GROWN MAGAZINE MARCH 2024

Apples

Complexity: Medium • Time: 60 minutes • Serves: 2-3

Courtesy of the Salvadorean Bakery and Restaurant, this savory, stuffed pupusa recipe is a great way to spice up your weekly taco night! Don't skip the curtido or the homemade salsa – the acid of the lightly pickled vegetables and the heat of the salsa pair so nicely with the warm, cheesy pupusa.

Pupusas ZUCCHINI

Curtido Ingredients

• 1 pound of shredded cabbage

• 2 oz of grated carrots

• 2 oz shredded cabbage

• 2 oz finely chopped white onion

• 1.5 tsp salt

• 1 tsp oregano

• 1 cup apple cider vinegar

• 1 cup water

INGREDIENTS

Pupusa Filling Ingredients

• 3 medium-sized zucchinis, grated

• 1/2 cup finely chopped tomatoes

• 1 tbsp finely chopped onion

• 1 tbsp Lawry's seasoned salt

• 2 oz mozzarella cheese, grated

• 2 oz cotija cheese, grated

Masa Ingredients

• 10 oz of Maseca (masa)

• 2 cups of warm water

Salsa Ingredients

• 1 pound of tomatoes, chopped

• 2 oz of chopped carrots

• 1/4 of an onion, chopped

• 1/4 of a red bell pepper, chopped

• 1/4 of a green bell pepper, chopped

• 2 cloves garlic

• 2 cups water

• 1 tsp oregano

• 2 chile de arbol (optional)

• Salt (to taste)

Curtido Method

Mix the vegetables with the salt and oregano.

Add water to the vinegar, then pour over the vegetables. Mix well.

If possible, let it sit in the refrigerator for 24 hours before serving. Leftover curtido can be refrigerated and kept for up to a week.

Salsa Method

Add all ingredients except oregano to a pot and boil for 10-12 minutes.

Pour ingredients (including water) into the blender and blend for 30 seconds, or until the salsa reaches a smooth consistency.

Pour blended mix back into pot. Add oregano. Bring the mix back to a boil and then remove from heat. Add salt to taste.

Let cool, then serve with pupusas, chips, or other dishes. Leftover salsa can be refrigerated for up to two weeks.

Filling Method

For the pupusa filling, start by mixing the grated zucchini, tomato, onion, and seasoning salt. After mixing well, allow the mix to sit for 10 minutes.

After 10 minutes, squeeze out all the liquid from the mixture using a cheesecloth or fine sieve.

Add the cheeses and mix well.

Pupusa Method

Mix the maseca with the warm water until it stops sticking to the bowl.

Rub your hand with oil so the masa doesn't stick to your hand.

Grab a 2-ounce piece and roll it into a ball.

Press a hole into the ball with three fingers, and put about an ounce of the zucchini filling into the hole.

Crimp the masa closed around the filling. When the filling is completely enclosed, gently flatten the masa.

Preheat a skillet, pan, or grill with a small amount of oil. Cook the pupusa on medium high for 5-10 minutes. Depending on the filling and the temperature of your grill, skillet, or pan, the cooking time may vary. You are looking for a nicely toasted, light brown crispiness on the surface of your pupusa.

Place the cooked pupusa on a plate. Top with 2 ounces of curtido and salsa, and enjoy!

Pair your pupusas with a crisp, refreshing Washington beer, like Bale Breaker's Topcutter IPA, made in Yakima!

THE SALVADOREAN BAKERY WHITE CENTER

meetsisters the ElbringingSalvador Seattle to

Sisters Ana and Aminta have supported each other through it all. Now, their restaurant, serving favorites from their childhood in El Salvador, is a pillar for the Latin American community in Seattle.

The bright and happy building on Roxbury Street, marked with a colorful mural, has been the home of the Salvadorean Bakery and Restaurant for nearly 30 years. Owned and operated by sisters Aminta Elgin and Ana Castro, the restaurant, serving delicious El Salvadorean cuisine and colorful cakes, is a fixture in the city of White Center. The sisters have created a thriving family business in the heart of the community.

Although their business is thriving now, their story didn’t have a happy beginning. Elgin, Castro, and their family faced a crucial turning point when civil war broke out in El Salvador in the late 1970s. The threat

to their livelihoods and lives prompted Castro and her husband to make the difficult decision to leave their homeland. In 1980, they arrived in the United States, and within five years, Castro became a naturalized citizen. Subsequently, she embarked on bringing each family member to Seattle, starting with Elgin.

“Because of the war in El Salvador, we couldn’t even go to school,” said Elgin. “If I had to tell you the story of all the challenges we went through, it would take a long time. We had to get out.”

Balancing day jobs as surgical technicians with

WASHINGTON GROWN MAGAZINE MARCH 2024 15

evening English classes, the sisters, driven by the scarcity of El Salvadorean eateries in the vicinity, reminisced about childhood family recipes. This nostalgia fueled their determination to open a bakery, marking the beginning of their entrepreneurial journey. At the time, theirs was the only Salvadoreanowned food business in Seattle.

“We used to have a bakery in El Salvador,” said Castro. “We worked lots of other jobs to survive, but in the back of my mind was always the bakery.”

When they opened the bakery in White Center in 1996, it gave the Latin American population of South Seattle a place that reminded them of home. There have been lean years and hardships along the way, but they continue to serve the community and share their heritage. The bakery makes dozens of different kinds of pastries, cookies, and sweets, sourced from all over Central America. Their specialty — tres leches cakes

ENTER TO WIN!

Visit our website and sign up to be entered into a drawing for a $25 gift certificate to the Salvadorean Bakery and Restaurant!

*Limit one entry per household

made with guava, oreos, or rum — is in so much demand that they set up a link on their website for customers to preorder. They also serve much more than just pastries and baked goods. The restaurant has a full menu for breakfast, lunch, and dinner — filled with Salvadorean favorites like pupusas, tamales, and classic Salvadorean stews.

“It’s part of my culture,” said one guest when the Washington Grown crew visited the restaurant in Season 11. “I was born in El Salvador, and this place makes the food just like ‘over there.’ It feels like home when you come over here.”

El Salvador is a place of rich heritage and culture, where music, arts, and food combine to create a vibrant and lively place. Much of their music, art, and food centers around religious holidays, so the sisters in White Center offer festive traditional dishes for Holy Week, Day of the Dead, Christmas, and other important holidays.

Sharing that culture has been the sisters’ goal since the very beginning. Elgin and Castro, even as they were achieving their own American Dream, wanted others to join them in celebrating El Salvador.

“We have accomplished bringing the culture of El Salvador to Seattle — through our food,” said Elgin with a smile.

The Washington Grown project is made possible by the Washington State Department of Agriculture and the USDA Specialty Crop Block Grant program, through a partnership with the state's farmers.

Marketing Director

Brandy Tucker

Editor-in-Chief

Kara Rowe

Editor and Art Designer

Jon Schuler

Assistant Editors

Trista Crossley

Elissa Sweet Writers

Jon Schuler

Elissa Sweet

Images

Tomás Guzmán

Jon Schuler

Christopher Voigt

Shutterstock

Washington Grown

Executive Producers

Kara Rowe

David Tanner

Chris Voigt

Producer

Ian Loe

Hosts

Kristi Gorenson

Tomás Guzmán

Val Thomas-Matson