Every Matters Acre

New legislationthreatens to destroy some of the most fertile agricultural land in America.

New legislationthreatens to destroy some of the most fertile agricultural land in America.

For Washington farmers, every acre matters. The right amount of sun, perfect type of soil and various microclimates throughout the state make this a haven for farming. In fact, only California grows more crops than we do in Washington. It is a precious and valuable resource for our state. The ability to produce such a variety of local food for Seattle, Spokane, Tacoma, Vancouver and all other areas in the state is a rare privilege. There are more than 60 farmers markets throughout the state, and our grocery store shelves showcase sales on healthy choices year-round. We have more than 35,000 farms that are organic, traditional, urban, rural, big and small. We grow so much food in this state that we have excess after feeding Washington and our neighbors around the U.S. Exporting food to nations across the globe is one of our major economic boosts for the state.

Even with that seemingly abundant food supply, the profit margins for farms throughout the state averages 1-5% and leaves little room for error. This makes every inch of farmable land valuable. What would happen if each farmer lost one acre of land? Or 20? Or 100? As we dive into a new legislative session in Olympia, this is what some legislators seem to be considering.

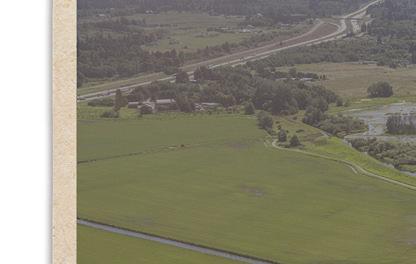

In the name of saving salmon, some officials want to take farmland out of production along the countless wetlands, streams, rivers and canals running throughout Washington’s farm country. Mandatory buffer ideas, like those introduced in the 2022 session, will hurt food production in the state. It will also disproportionately have a negative impact on small, new and low income farmers. For example, in Skagit County, the average farm size is 94 acres. A buffer zone of 200 feet along one mile of canal or river is equal to 24 acres of land – more than 25% of the entire farm. This mandatory law would force many farmers to sell off land, and some would even quit farming altogether. This wouldn’t lead to farm and fish-friendly practices, it would lead to land sold to the highest bidder; in many cases that would be developers. Farmland will then become houses and pavement, not wildlife and fish-friendly fields. And once the farmland is gone, it’s gone for good.

But what these legislators seem to be missing is the answer to a simple question: would it even work? Washington does not have confirmed smolt (baby salmon) count numbers or evidence that current riparian enhancement projects are working. There is little data to prove the fish are benefitting from these projects that are now more than a decade old. And, studies show that ocean warming, overfishing, roadway pollution and urban development are more responsible for salmon decline than managed farmland.

Farmland is a beneficial neighbor to waterways. A field of potatoes, raspberries, or spinach is more fish-friendly than a shopping center, parking lot, or housing development. Farmers use best management practices to mitigate noxious weeds, runoff and pollution. They understand the advantages of good conservation practices, and many protect and restore natural riparian areas on their own land voluntarily. This undoubtedly protects salmon better than the alternative of urban development.

As young and beginning farmers search for land to make their start and urban sprawl continues to invade farmable acreage, it becomes even more evident that there is not enough land available for all who want to produce food. Every acre of farmable land matters. A reduction of any farmable land has a direct impact on the local food supply. Residents in the greater Seattle area would be impacted by a loss of farmland in Skagit County and throughout the state. Mandatory buffers unfairly blame farming and food production for lagging salmon recovery while other, more direct problems with the ecosystem, such as overflowing sewage plants and sprawling urban and industrial development, are not being addressed appropriately. Washington farmers take pride in caring for their land and providing food to their neighbors, and they are helping keep waterways healthy voluntarily. Mandatory buffers of any size will negatively affect the wrong target.

In 2001, Washington adopted WAC 173-503, which already makes the Skagit River watershed one of the most regulated waterways in America,

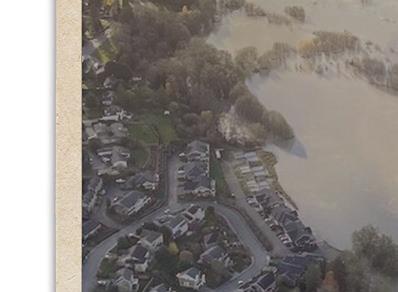

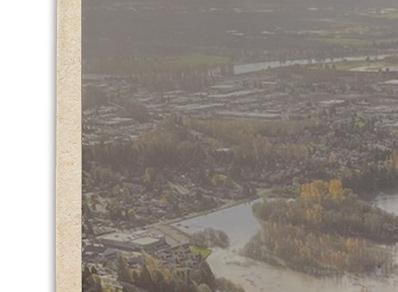

The Skagit River and hundreds of its tributary streams crisscross the Skagit Valley (top), delivering 10 billion gallons of water each day to the Puget Sound. The river is contained by a series of dikes and levees, but the valley is notorious for flooding.

There are more than 1,000 individual farms in the Skagit Valley, and more than 80,000 acres in the Skagit Valley are classified as farmland.

Washington’s Skagit Valley is the Promised Land for Seed Crops

It’s common knowledge that most plants start from seed. A seed is planted, and shortly thereafter a tiny seedling will emerge from the soil, ready to photosynthesize and grow into a mature plant. But, where did that seed come from? Well yes, a plant produced that seed, and there’s a lot that goes into the plant that grew the seed!

The Skagit Valley, located in northwestern Washington, is home to a diverse community of agriculturalists. A variety of crops, ranging from tulips to turnips, flourish in the fertile soils and mild climate of the Skagit Valley.

Dave and Annie Lohman are two of the many growers that call the Skagit Valley home. The Lohman Farm produces seed for vegetable crops including beets, broccoli, cabbage and spinach. They take on the challenge of growing these finicky foods because the Skagit Valley “is one of the few areas in the world where you can successfully grow some of these crops.”

“It just happens to be the most unique climate that everything agrees with,” said Dave. When compared to other vegetable seed-producing areas, the Skagit Valley outyields all others and offers consistency that is hard to come by. Skagit County is known as a significant world contributor, producing approximately 8% of the world’s spinach seed, 25% of the world’s cabbage seed, and 25% of the world’s beet seed.

The Lohmans have been in the seed business for decades. They represent the first step to producing the vegetables we all enjoy. Seed from the Lohman Farm is shipped to California and elsewhere to be planted and grown into vegetables, which, in turn, are sold at grocery stores across the country.

But vegetable seed production is highly technical and often involves complicated rotation intervals —

We have all these factors that make it ideal for growing a lot of crops ... and it would be a tremendous shame if that opportunity goes away.

sometimes stretching beyond a decade. Dave and Annie can’t just rely on the ideal weather to grow their crop for them. An immense amount of planning and management goes into producing a pure seed crop. Depending on the vegetable, the methods used to plant, pollinate and harvest can vary.

For example, Lohman Farm produces spinach, which requires their fields to be spaced properly to avoid cross-pollination from other fields. Annie adds, “They’re wind pollinated, so it’s very important that you don’t accidentally contaminate someone else’s crop on the bee-pollinated crops such as cabbage,” said Annie. Bees can travel up to two miles to collect pollen, so strategic field and hive placement is imperative to ensure successfully pollinated crops.

Strategic planning and communication between farmers make Skagit Valley seed production a success. The Lohmans work with their neighbors to meet the needs of their crops and the many other farmers in the region. Crops must be rotated and isolated to maintain seed purity. Farmers go as far as sharing land to make this cycle work.

As urbanization and industrialization continue to encroach upon the 80,000 acres of agricultural land in the region, opportunities for food production are lost. “If you reduce the amount of available cropland for seed production, you’re losing opportunity,” said An-

nie. Skagit Valley land is precious to agriculture, and farmers like Dave and Annie are working hard to keep it in production. “We have all these factors that make it ideal for growing a lot of crops besides seed crops, and it would be a tremendous shame if that opportunity goes away.”

Many associate Skagit Valley with tulip bulbs –but in 2021, vegetable seed production actually used 4x as many acres as ower and bulb production. There are six vegetable seed companies in Skagit County, most of which market their seeds worldwide.

Skagit Valley seed products include:

Fortunately, progressive agriculturists like Dave and Annie Lohman are focused on continuing their vital work to produce high quality seed products to support the vegetable industry. Next time you are enjoying a beet salad or spinach-artichoke dip, you have farmers like the Lohmans to thank for laying the groundwork.

The spinach seed grown on the Lohman Farm creates a unique challenge. Neighbors strategize together and communicate frequently to isolate their spinach to maintain the seed purity.Arugula

Broccoli

Brussels Sprouts

Cabbage

Cauliflower

Chinese Cabbage

Chinese Kale

Chinese Mustard

Coriander

Fava Beans

Kale

Kohlrabi

Parsley

Parsnip

Pinto Beans

Radish

Red Beans

Rutabaga

Ryegrass

Spinach

Swiss Chard

Table Beet

Tall Fescue

Turnip

KSPS (Spokane)

Mondays at 7:00 pm and Saturdays at 4:30 pm ksps.org/schedule/

KWSU (Pullman)

Fridays at 6:00 pm nwpb.org/tv-schedules/

KTNW (Richland)

Saturdays at 1:00 pm nwpb.org/tv-schedules

KBTC (Seattle/Tacoma)

Saturdays at 6:30 am and 3:00 pm kbtc.org/tv-schedule/

KIMA (Yakima)/KEPR (Pasco)/KLEW (Lewiston)

Saturdays at 5:00 pm kimatv.com/station/schedule / keprtv.com/station/schedule klewtv.com/station/schedule

KIRO (Seattle)

Check local listings kiro7.com

NCW Life Channel (Wenatchee) Check local listings ncwlife.com

RFD-TV

Thursdays at 12:30 pm and Fridays at 9:00 pm (Pacific) rfdtv.com/

*Times/schedules subject to change based upon network schedule. Check station programming to confirm air times.

Total Time: about 1.5 hour • Serves 6

Roast Chicken

1 whole chicken (about 4-6 lbs)

2 bay leaves

1 tbsp salt

2 cloves garlic

Vinaigrette

2 tbsp finely chopped pickled leeks (or substitute pickled onion)

1 tbsp water

1 tbsp sugar

1 tsp minced jalapeño (or substitute other chile pepper)

1/2 clove garlic, minced

1/8 tsp tomato paste

1/4 cup coconut water

2 tbsp fish sauce

1 tbsp rice wine vinegar

2 tsp shallot oil*

Cabbage Salad

8 to 10 cups thinly sliced green cabbage (about half of a large head)

1 cup julienned carrot

3/4 cup very thinly sliced red onion

1/2 cup cilantro leaves

1/4 cup chopped mint leaves

1/4 cup rau ram (Vietnamese coriander) (or substitute cilantro)

Garnish

Fried shallots*

Chopped peanuts

Thinly slivered lime leaf

In a pot large enough to generously hold the chicken, fill halfway with water and add the bay leaves, garlic and salt. Bring to a boil over medium-high heat and gently add the chicken; if there is not enough water to cover the chicken, add a bit more hot water. Cook the chicken for about 45 to 55 minutes; the water should simmer gently, reduce heat to medium when the water returns to a boil. Use a slotted spoon to skim away any scum that rises to the surface. When the chicken is cooked (internal temperature should be 165 degrees F), carefully remove it from the water and let cool. Reserve the broth to strain and save for another use if you like.

While the chicken is cooling, prepare the vinaigrette. In a mini processor or blender, combine the pickled leek, water, sugar, jalapeño, garlic and tomato paste and blend until smooth. If there’s not enough liquid to blend, add 1 to 2 tablespoons of the coconut water. Add the coconut water, fish sauce, vinegar and shallot oil and pulse to blend.

When the chicken has cooled, pull the meat from the bones and shred it, discarding the skin. To assemble the salad, combine the cabbage, carrot, red onion, cilantro, mint and rau ram in a large bowl. Drizzle the dressing over and toss well to mix.Arrange the salad on individual plates, add the shredded chicken (you may have a bit more chicken than needed) and top with fried shallot, peanuts and lime leaf.

*This recipe is adapted from the preparation that you can see on Season 10 Episode 3 at wagrown.com. On the website, you will also see instructions for making the crispy fried shallots and shallot oil used in the recipe.

This light, fresh Vietnamese salad from Ba Bar in Seattle combines crisp cabbage and steamed chicken with peanuts, fried shallots, and a killer nước chấm vinaigrette.

Visit our website and sign up to be entered into a drawing for a $25 gift certificate to the Ba Bar in Seattle!

*Limit one entry per household

About 95% of Washington farms are familyowned and 83% are small farms. 63% of the farms in Washington are less than 50 acres.

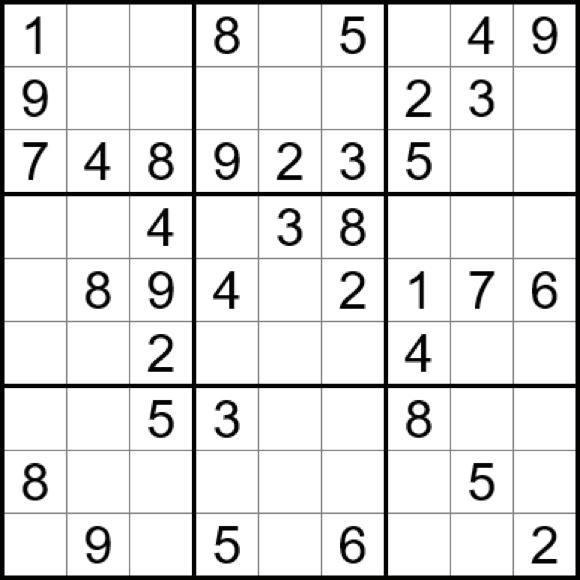

ACROSS

2.You plant them in the soil.

2. You

4.Capable of producing abundant crops.

4. Capable

5.When a river escapes its banks.

5. When

6. A

6.A proposed neutral area around waterways.

DOWN

1.Unit of measuring land.

1. Unit

2. River

2.River that runs from BC to Puget Sound.

3.The best comes from Washington.

3. The

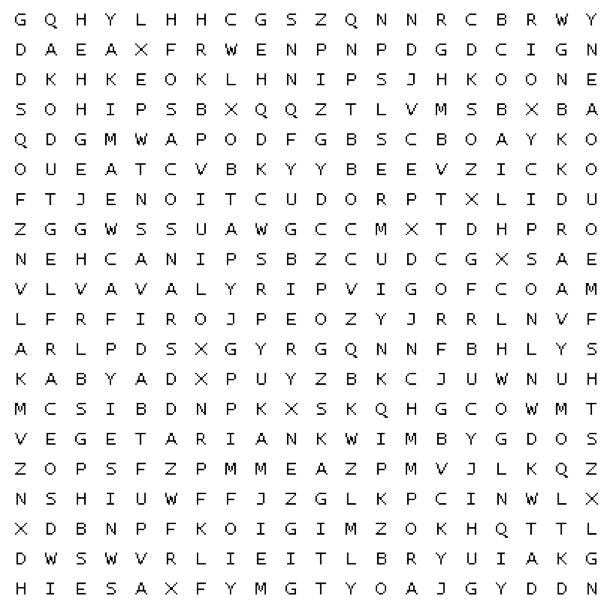

VEGETABLES

VEGETARIAN

As explained in Eater magazine this summer, “Ba Bar is the spot for those who want to have Vietnamese noodles made with grass-fed beef and local duck or chicken.”

Washington Grown visited the University Village location in Seattle this year looking for authentic Vietnamese street food. It seems we were in the right place, because many have dubbed this the best pho in Seattle. Co-owner Eric Banh let us into his kitchen, and his energetic and vivid personality made us feel right at home. Eric and his sister grew up eating street food in Saigon, giving his restaurant a special flavor that comes straight from the heart.

They serve delicious cuisine packed with all sorts of flavors that complement the decor, creating a unique Southeast Asian experience for anyone looking for authentic Vietnamese street food. Banh uses locally grown ingredients to bring Southeast Asian flavors to the Northwest. In his eyes, the fresher the produce, the better.

Few people will look at their salad bowl and consider the immense amount of research, labor and resources that went into growing the various vegetables they are enjoying. It turns out that those veggies have a pretty cool story.

Washington is one of the most agriculturally diverse states in the U.S., bringing commodities like potatoes, berries and flowers to the global market. The Skagit Valley provides the perfect climate for growing these specialty crops. It also allows farmers to take on the challenge of producing something equally as important – seeds.

Sierra Hartney, the senior pathology manager for Sakata Seed America, took us to a cabbage seed field to explain just how important seed production is to the global food systems we all benefit from.

“This is a field that will be harvested for seed, then that seed will be sold to a fresh market

Understanding how certain crops, like this cabbage, are pollinated is imperative to understanding the farming practices of the Skagit Valley.

Seed farmers in the Skagit Valley work as a team each year to put together a complicated puzzle covering thousands of acres.

grower that will then plant it and grow a head of cabbage,” explained Hartney. Sometimes that head of cabbage will be packaged and sent to the grocery store to be sold whole. Other times, it will head to a processing facility to be made into a coleslaw or salad mix.

“One of the real interesting things about the Skagit Valley is that we are growing wind-pollinated crops where the pollen floats through the wind, then we have something like cabbage here that is insect [or] bee-pollinated,” she said.

Plants have adapted over time to find the most suitable method of pollination. Pollination is simply the transfer of pollen from one flower to another, in an attempt to fertilize the ovule and eventually produce seed. How that pollen travels and the anatomy of the flower depends on the crop being produced.

For example, a popular Skagit Valley seed crop like beets is a wind-pollinated crop. The pollen grain is smaller and lighter than those of insect-pollinated crops. This allows the pollen to be easily transported by the wind from one row of beets to the next, successfully fertilizing the beet plants and pushing them to produce seeds. Wind-pollinated plants grow flowers that are typically light in color, lack smell and have reproductive parts (stigma and anthers) that are easily seen outside of the flower to catch pollen as it floats by.

On the other hand, crops like cabbage rely on insect pollination to complete the life cycle. The flowers on insect-pollinated crops are bright in color and often have a strong, sweet smell that is irresistible to bees flying by. The pollen grain is larger and stickier so when an insect does crawl inside, it’s covered in pollen while snacking on the flower’s nectar. That insect then visits another flower nearby, leaving some pollen behind to fertilize

Val and the Washington Grown TV crew visited Sakata Seed America in the Skagit Valley to learn about how vegetable seeds are grown.

the flower and eventually create cabbage seed.

Understanding how certain crops are pollinated is imperative to understanding the farming practices of the Skagit Valley. Crops must be strategically spaced out to prevent cross-contamination. With limited land available and purity of seed being the main goal for seed producers, pinning has become an annual tradition.

“The growers and seed companies pin together. We call it pinning because it’s traditionally a little pushpin in a map saying, ‘My field is here. I’m going to grow this type,’” said Hartney. Dating back to the 1940s, Pinning Day has been an important part of the spring planting season in the Skagit Valley. Taking their knowledge of pollination, the crops they are growing, and a little bit of teamwork, farmers of the Skagit Valley put together the puzzle of seed crops across the region to ensure the success of everyone.

Every acre of Skagit Valley land is being utilized to the best of the farmers’ abilities. Even land that sits idle for a year to allow for proper spacing is valuable. “Here in the Skagit, it’s a valley. We’re hemmed in by the ocean. We’ve got the mountains, so then the acreage is set,” said Hartney. This fact makes the knowledge of farmers, research by scientists, and collaboration of the agricultural community that much more important.

“We grow seeds that go around the world to feed people. We’re feeding people,” she said. “When you go to the store and grab a salad off the shelf, there were farmers and laborers and scientists, all that to get you your bag of salad.”

Jones says, “The whole idea is to prevent any kind of farming activity from negatively affecting our waterways. A lot of farmers are very cognizant of that anyways, but this gives them a framework to help protect these watersheds. Doing so on a voluntary basis is better than anything else and forcing fold to do it.”

What do stewardship practices look like?

Providing a conservation framework to farmers is the first step to achieving environmental goals. Emmett Wild, a senior planner for Skagit County Conservation District, is one of the many conservationists working directly with farmers. Wild assisted a local farmer to implement the use of cover crops on her farm to reduce soil erosion and suppress weed growth.

Farmers across Washington are stewards of the environment. It’s in their best interest to protect our waterways, soils and air. In order to create a clean, productive environment for generations to come, farmers must make responsible and proactive management decisions today. Individuals like CJ Jones and Emmett Wild work hand in hand with farmers in Skagit County to formulate and implement stewardship plans.

What is the Voluntary Stewardship Program?

The Voluntary Stewardship Program provides incentives to farmers to improve their natural resource management practices. CJ Jones, the stewardship program coordinator in Skagit County, and his team encourage farmers to implement conservation practices on their farms. This can range from planting native shrubs along a streambed or using cover crops to keep soil healthy.

“We helped her choose an organic rye vetch mix, which helps to suppress those weeds from germinating,” Wild says. “Cover crops are not always something that you see a real short-term benefit in, especially financially. It’s an added cost at the end of the season. If we can help, through VSP (Voluntary Stewardship Program) or other cost-share programs, cover that seed cost, we can still get a great environmental benefit and a good long-term benefit for the farmer.”

Jones adds, “Farming is very hard work, and a lot of farmers are very devoted to what they do, and are very proud of how they manage the landscape. Being able to provide tools to allow farming to continue to be prosperous in the long term is good. Not only good for the soil, but it’s also good for the environment. It’s good for people [too] ... We help support our local farmers right here in Western Washington. It’s good for everybody.”