Copyright

Omnino

Omnino is a peer-reviewed, scholarly research journal for the undergraduate students and academic community of Valdosta State University. Omnino publishes original research from VSU students in all disciplines, bringing student scholarship to a wider academic audience.

Undergraduates from every discipline are encouraged to submit their work; papers from upper level courses are suggested.

The word “Omnino” is Latin for “altogether.” Omnino stands for the journal’s main mission to bring together all disciplines of academia to form a well-rounded and comprehensive research journal.

ISSN: 2472-3223 (Print), 2472-3231 (Online)

Managing Editors

Sarah D. Burch

Jacquelynn Robinson

Student Editors

Jenna Arnold

Airionna S. Fordham

Karli Icard

Karsyn Long

Brittany McNulty

Ivionna Pettigrew

Lydia Williams

Margie Woodhurst Kersey

Graphic Designer

Katie Holton

Faculty Advisor

Dr. Anne Greenfield

Copyright © 2025 by Valdosta State University

COVID 19 and Mental Health: What are the Key Predictors of the Suicide Rate Before the Pandemic and Then in the Wake of the Pandemic Across the 50 States? 7

By Kaylor Stone

Faculty Mentor: Dr. James LaPlant, Department of Political Science

The Scope and Nature of White-Collar Crime in The United States: A Review of Cases from the FBI’s database on Fraud and Embezzlement 24

By Sabrina Maine

Faculty Mentor: Dr. Rudy Prine, Department of Criminal Justice

Una ventana a la realidad femenina en la literatura hispana / A Window to the Feminine Reality in Hispanic Literature 37

By Meghan Barnett

Faculty Mentor: Dr. Ericka Parra, Department of Modern and Classical Languages

The Beauty Behind Nature’s Masterpiece: The Medicinal Roles and Biogeography of Roses

By Judith-Selah Israel

Faculty Member: Dr. John G. Phillips, Department of Biology

From Brokenness to Wholeness: The Journey of Trauma and Healing

By Jacquelynn Robinson

Faculty Mentor: Dr. Ryan Wander, Department of English

Mitákuye Oyás’iŋ: An Analysis of Native North American Cosmologies and Western Science 65

By Cecilia Grace Kee

Faculty Mentor: Dr. Shelly Yankovskyy, Department of Anthropology

La reafirmación de la Reconquista: El porqué de la humanización de la “Rosa entre las Rosas” en las Cantigas de Santa María 80

By Lauren Mariah

Faculty Mentor: Dr. Grazyna Walczak, Department of Modern and Classical Languages

How to Play a Musical Instrument More Often: A Simple AB Design on Increasing Duration of Ukulele Playing 89

By Eldred B. Jones

Faculty Mentor: Dr. Deborah Briihl, Department of Psychological Science

COVID 19 and Mental Health: What

are the Key Predictors of the Suicide Rate Before the Pandemic and Then in the Wake of the Pandemic Across the 50 States?

By Kaylor Stone

Faculty Mentor: Dr. James LaPlant, Department of Political Science

Article Abstract:

The purpose of this quantitative study is to investigate the key factors contributing to the suicide rate before (2019) and during the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic (2021). This study explores the key predictors of the change in the suicide rate from 2019 to 2021. Nine independent variables were analyzed: population with a bachelor’s degree, population aged 25 to 64, Trump votes by state in 2020, state mental health agency expenditures per capita, percentage unemployed during the pandemic peak, crime rate, gun restrictions, population density, and region. Three dependent variables were studied: the 2019 suicide rate, the 2021 suicide rate, and the rate change. Correlation analysis, scatterplots, box plots, bivariate analysis, and multivariate regression analyses were conducted. Gun restrictions by state were the only statistically significant predictor of the change in suicide rates. Population density was found to be a statistically significant predictor of suicide rates in 2019 and 2021. The percentage of the vote for Trump by state was found to be significant for two of the three dependent variables: the suicide rate per 100,000 people in 2019 (pre-pandemic) and the suicide rate per 100,000 people in 2021 (post-pandemic). Contrary to the hypothesized relationship, state mental health spending per capita is positively associated with the suicide rate in 2019 and 2021. In relation to region, the west demonstrated the highest suicide rates with the lowest in the northeast.

Introduction

The COVID-19 virus originated in late 2019 and rapidly dispersed across the globe by early 2020. Governments worldwide instituted a range of strategies, such as social isolation and lockdowns, to halt the spread of the virus. People across the world braced themselves for a new world. Lockdowns and quarantine procedures caused social isolation, which worsened pre-existing mental health issues and heightened feelings of loneliness. The strain on mental health increased for some due to job loss and financial instability, resulting in a dual crisis of psychological and economic discomfort. The transition to remote learning and the subsequent closure of schools had a profound effect on the mental health of students, parents, and educators equally, as they grappled with the difficulties associated with adjusting to new forms of education. The pandemic has significantly impacted mental health as a result of various factors, such as isolation, uncertainty, fear of illness, economic strain, and routine disruptions. People suffered increased worry, sadness, and stress as they dealt with the pandemic’s hardships. The main question being asked is, what are the key predictors of the suicide rate before the pandemic and then in the wake of the pandemic across the 50 states? Across the nation, expenditures on mental health vary from state to state. Additionally, variations in education levels, population densities, and gun control policies between states may have an impact on mental health and the suicide rate. The nation’s crime rate also exhibits regional variation. Suicide rates before and after the pandemic may vary by region of the country and by the percentage of Trump votes in 2020.

The purpose of this quantitative study is to investigate the key factors of the suicide rate before and during the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Several studies have been conducted to explain the suicide rate prior to the pandemic and to explain some of the effects that the COVID-19 pandemic has had on people across the country. These studies will be explored in the first section of this study. The second section of this study will explore the data and methods of this study. The next section will examine the significant findings of this study. The final section of this study will explain the importance of the findings of this study and will offer guidance for studies to come.

Exploring the Possible Key Predictors of the Suicide Rate Before the Pandemic and in the Wake of the Pandemic

Kathy Katella (2021) notes that in March of 2020 the World Health Organization formally recognized COVID-19 as a pandemic. California became the first U.S. state to mandate a stay-at-home order. As the number of cases increased, hospitals experienced an overwhelming workload, leading to a widespread scarcity of personal protective equipment on a

national scale. Cases began to rapidly increase throughout the United States in April. The nation also began to experience the initial economic repercussions of the pandemic at this time, as an increasing number of states issued stay-at-home orders.

The United States labor market experienced an unprecedented period of volatility amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Employment decreased by 13.6 percent, or 20.5 million people, between March and April 2020; this is the largest one-month decline in employment since 1939. Not only was there a decline in employment, but there was also an increase in job separations. This increase reached an all-time peak of 16.3 million by March 2020, up from 5.7 million in February 2020. It took over a year for this to be reversed and return to pre-pandemic levels (US Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2022). The ongoing pandemic caused a spike in mental health issues in July, as evidenced by widespread job loss, parents balancing work from home and childcare duties, and young adults feeling frustrated by their lack of social opportunities and job isolation (Katella, 2021). Furthermore, economic downturns can lead to an increase in suicidal ideation (Sher, 2020). Mental health professionals began to worry about everyone, even people who were not in high-risk roles, like healthcare workers or people who had survived a serious case of COVID-19. According to data released by the U.S. Census Bureau in May, one-third of the American population reported exhibiting symptoms consistent with clinical anxiety or depression (Katella, 2020).

In the past, economic uncertainty has been associated with an increase in mental health disorders and suicide. Research has found correlations between increases in the unemployment rate and heightened rates of depression, substance use disorders, and suicide. Previous observational studies have found job insecurity and unemployment as significant risk factors for increased depressive disorders. Suicides increased in the United States throughout the Great Depression. Suicide rates peaked during periods of unemployment and recession, specifically in 1921, 1932, and 1938 (Sher, 2020).

Many began to realize, based on the earlier evidence, that the pandemic might affect several vulnerable communities in ways other than health problems. One of these vulnerable communities includes people with mental health issues prior to the pandemic. There have been widespread reports of elevated rates of anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. The implementation of COVID-19 stay-at-home orders has been linked to feelings of social isolation, which has been found to worsen mental health issues and contribute to fatal overdoses (Kohrt, 2022). A health alert network advisory was issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The CDC recognized a substantial increase in drug overdose deaths across the United States. This influx started

in 2019, before the pandemic, and accelerated throughout the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Preliminary data indicated that the number of fatalities attributed to drug overdoses exceeded 81,000 throughout the twelve months ending in May 2020. A concerning acceleration in the number of fatal drug overdoses was identified in the health alert, with the greatest increase occurring between March and May 2020, which can be attributed to the implementation of widespread COVID-19 pandemic mitigation measures. The most significant influence occurred with synthetic opioids, which accounted for a 38.4% surge in fatal overdoses during this time frame (Georgia Department of Public Health, 2023).

In the two decades before the pandemic (1999-2019), an estimated 800,000 fatalities were attributed to suicide, representing a 33 percent surge in the suicide rate throughout that period (Stone, Jones, Mack, 2021). Suicide rates were found to be lower in urban areas, and higher in older populations (Stone, Jones, Mack, 2021). Individuals aged 25 and older who hold a bachelor’s degree or higher have consistently demonstrated lower suicide rates, in contrast to those with only a high school diploma (Phillips and Hempstead, 2017). Employment opportunities are typically greater in urban areas than in rural areas. Likewise, this applies to education. Individuals with advanced degrees typically have greater employment opportunities compared to those with lower levels of education. It was also determined that the highest percentage of suicides involving firearms occurred in 2019 (Stone, Jones, Mack, 2021). Coincidentally, firearm purchases increased during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States (Hicks, Vitro, Johnson, Sherman, Heitzeg, Durbin, & Verona, 2023). States with stricter gun restrictions and lower rates of gun ownership were linked to a decrease in firearm-related suicides in the United States among adults and juveniles (Paul and Coakley, 2023). Furthermore, beginning in the summer of 2020 and continuing through 2021, there was a significant surge in firearm-related violence throughout the country (Hicks, Vitro, Johnson, Sherman, Heitzeg, Durbin, & Verona, 2023). Levels of gun restrictions and violence may also be linked with levels of suicide among states. Finally, presidential elections can have an impact on suicide rates. It has been shown that suicide rates increase following polarizing elections, as was observed in the 2016 election of Donald Trump (Classen, 2010).

Data and Methods

The unit of analysis for this study are the fifty states. There are three dependent variables in this study: the suicide rate per 100,000 people in 2019, the suicide rate per 100,000 people in 2021, and the measure of change of the suicide rate between 2019 and 2021. The data for the 2019 and 2021 suicide rates can be found on the “Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention” website.

There are nine independent variables in this study that have been observed in order to evaluate their effect on the suicide rate before and after the pandemic throughout the fifty states. The percentage of the population with a bachelor’s degree and the percentage of the population aged 25 to 64 can be found on the “Annie E. Casey Foundation Data Center” website. The percentage of Trump votes in 2020 can be found on the “Cable News Network” (CNN) website. The amount of state mental health agency expenditures per capita can be found on the “American Addiction Center’s Rehab” website. The percentage of the population unemployed at the height of the pandemic can be found on the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics website. The crime rate per 100,000 people can be found on the “Statista” website. The level of gun restrictions by state can be found in the “SPSS Statistics Data Set” on States. The regions of the United States can be found on the “Centers for Disease Control and Prevention” website. The population density by state can be found on the “United States Census Bureau” website.

Table 1: Variables, Characteristics, and Sources

E. Casey Foundation Data Center

As stated earlier, the dependent variable is composed of three different measures: the suicide rate per 100,000 people in 2019 (prepandemic), the suicide rate per 100,000 people in 2021 (post-pandemic), and the change rate before (2019) and after (2021) the pandemic. The

suicide rate per 100,000 people in 2019 (pre-pandemic) ranges from 8.00 (New Jersey) to 29.30 (Wyoming), with a mean of 16.3980 and a standard deviation of 4.71989. The suicide rate per 100,000 people in 2021 (postpandemic) ranges from 7.10 (New Jersey) to 32.30 (Wyoming), with a mean of 16.9720 and 5.62933 and a standard deviation of 5.62933. The measure of change in the suicide rate before and after the pandemic ranges from -2.40 and 5.80 with a mean of .5740 and a standard deviation of 1.57140. There were twenty-one states whose suicide rate decreased between 2019 and 2021, and twenty-nine whose suicide rate increased between 2019 and 2021.

The percentage of Trump vote in 2020 ranged from 31 (Vermont) to 70 (Wyoming), with a mean of 50.08 and a standard deviation of 10.325. The amount of state mental health agency expenditures per capita ranged from 36.05 (Florida) to 362.75 (Maine), with a mean of 131.8748 and a standard deviation of 79.75154. The percentage of the population with a bachelor’s degree ranged from 14 (West Virginia) to 28 (Colorado), with a mean of 21.3000 and a standard deviation of 3.30275. The percentage of the population unemployed at the height of the pandemic ranges from 5.20 (Wyoming) to 30.60 (Nevada), with a mean of 13.6460 and a standard deviation of 4.28887. The crime rate per 100,000 people ranges from 1245.28 (New Hampshire) to 3620.15 (New Mexico), with a mean of 2320.4676 and a standard deviation of 631.46325. The population density ranges from 1.30 (Alaska) to 1263.00 (New Jersey), with a mean of 206.5080 and a standard deviation of 274.91651. The percentage of population age 25 to 64 ranges from 63.00 (Vermont) to 71.00 (Alaska) and has a mean of 66.2600 and a standard deviation of 1.79353. Gun restrictions were coded 1-3: (1) more restrictive, (2) moderately restrictive, and (3) less restrictive. Regions were coded 1-4: (1) northeast, (2) midwest, (3) south, and (4) west.

The hypotheses to be tested in this study are as follows:

H1: As the percentage of the vote for Trump increases, the suicide rate will increase.

H2: As the crime rate increases, so will the suicide rate.

H3: As gun restrictions increase, the suicide rate will decrease.

H4: As the amount of state mental health agency expenditures per capita increase, the suicide rate will decrease.

H5: As the percentage of population unemployed at the height of the pandemic increases, the suicide rate will increase.

H6: As the population density decreases, the suicide rate will increase.

H7: As the percentage of the population with a bachelor’s degree increases, the suicide rate will decrease.

H8: As the population percentage age 25 to 64 decreases, the suicide rate will increase.

Findings

After running a correlation analysis, six variables were statistically significant in relation to the 2019 suicide rate. The non-significant variables were the amount of state mental health agency expenditures per capita, and the percentage of the population aged 25 to 64. The significant variables were the percentage of Trump vote in 2020, the percentage of the population with a bachelor’s degree, the percentage of the population unemployed at the height of the pandemic, the crime rate per 100,000 people, the gun restrictions per state, and the population density by state. The Trump vote in 2020 was significant at p<.01 with a correlation coefficient of .529. The percentage of the population with a bachelor’s degree was significant at p<.05 with a correlation coefficient of -.289. The percentage of the population unemployed at the height of the pandemic was significant at p<.05 with a correlation coefficient of -.304. The crime rate per 100,000 people was significant at p<.01 with a correlation coefficient of .372. Gun restrictions were significant at p<.01 with a correlation coefficient of .563. Population density was significant at p<.01 with a correlation coefficient of -.681.

The correlation analysis of the 2021 suicide rate also had six statistically significant variables. The non-significant variables were the amount of state mental health agency expenditures per capita and the percentage of the population age 25 to 64. The significant variables were the percentage of Trump vote in 2020, the percentage of the population with a bachelor’s degree, the percentage of the population unemployed at the height of the pandemic, the crime rate per 100,000 people, the gun restrictions per state, and the population density by state. The percentage of Trump votes in 2020 was significant at p<.01 with a correlation coefficient of .544. The percentage of the population with a bachelor’s degree was significant at p<.05 with a correlation coefficient of -.317. The percentage of the population unemployed at the height of the pandemic was significant at p<.05 with a correlation coefficient of -.295. The crime rate was significant at p<.05 with a correlation coefficient of .347. The gun restrictions were significant at p<.01 with a correlation coefficient of .622. The population density was significant at p<.01 with a correlation coefficient of -.676.

The correlation analysis of the suicide change rate in 2019 and 2021, outlined in Table 2, had three statistically significant variables. The significant variables were the percentage of Trump votes in 2020, gun restrictions per state, and population density by state. All other variables were statistically non-significant. The percentage of Trump votes in 2020 was significant at p<.05 with a correlation coefficient of .361. Gun restrictions per state was significant at p<.01 with a correlation

coefficient of .535. Population density was significant at p<.01 with a correlation coefficient of -.375.

Table 2: Correlation Analysis

Independent Variables

Trump Vote in 2020

Amount of State Mental Health Agency

Rate per 100,000 People in 2019

Rate per 100,000 People in 2021

Measure between 2019 and 2021

of Population Age 25 to 64

per 100,000 People

N=50, *p<.05, **p<.01

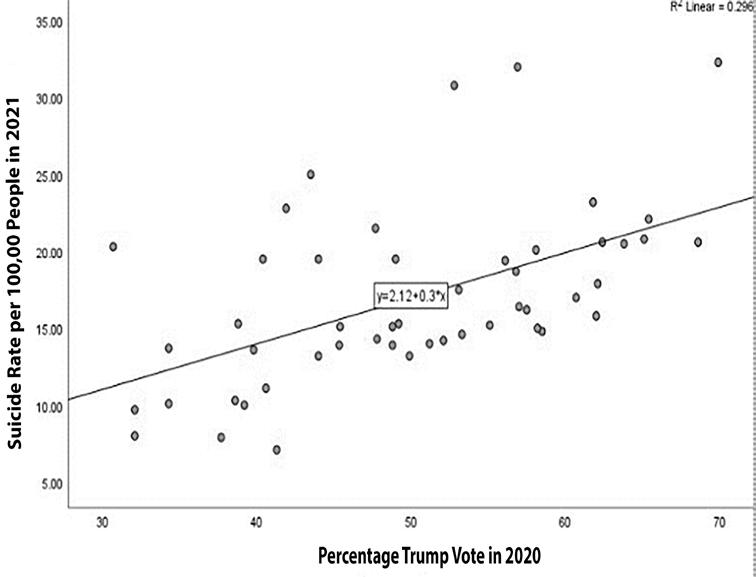

Figure 1 is a bivariate regression analysis that reveals a positive

and statistically significant relationship between the percentage of the vote for Trump in 2020 and the suicide rate per 100,000 in 2021. An r-squared value of 0.296 indicates that the Trump vote in 2020 explains 29.6 percent variance in the dependent variable of the suicide rate per 100,000 people in 2021. The regression line is equal to y=2.12+0.3*x. The y-intercept explains that if there were no votes for Trump, the suicide rate would decrease by 2.12. The slope of the regression line explains that for every percentage point increase in the Trump vote, the suicide rate increases by 0.3.

Figure 1: Scatterplot of the Percent of Trump Vote in 2020 and the Suicide Rate in 2021

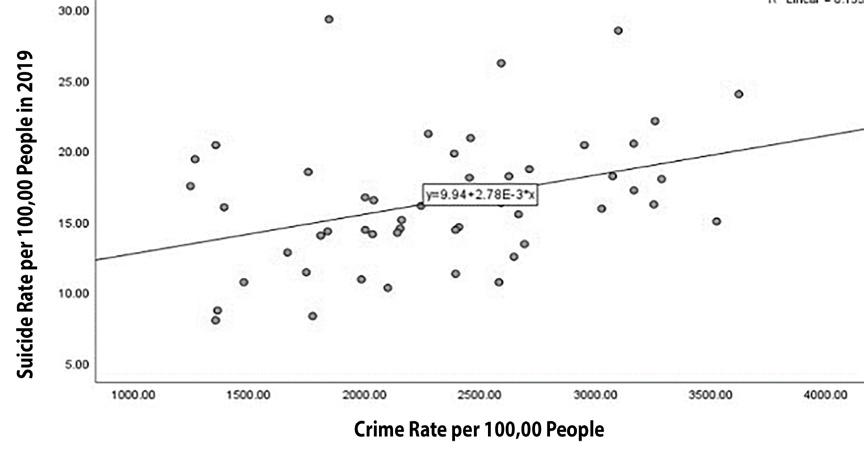

Figure 2 is a bivariate regression analysis that displays a positive relationship between the crime rate per 100,000 people and the suicide rate per 100,000 people in 2019. An r-squared value of 0.139 indicates that the crime rate per 100,000 people explains 13.9 percent variance in the dependent variable of the suicide rate per 100,000 people in 2019. The regression line is equal to y=9.94+2.78E-3*x. The y-intercept explains that if there were no crime, the suicide rate would decrease by 9.94. The slope of the regression line explains that for every point increase in the crime rate, the suicide rate increases .00278.

Figure 2: Scatterplot of the Crime Rate per 100,000 people and the Suicide Rate in 2019

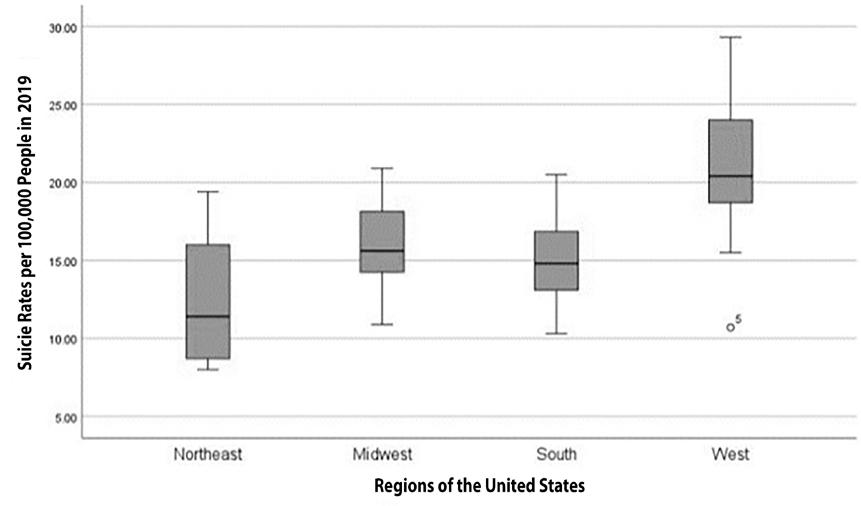

Figure 3 is a boxplot that shows the suicide rate in 2019 by region. The boxplot displays the median values of each region. The northeast has a median of 9, the midwest has a median of 12, the south has a median of 16, and the west has a median of 13. The west is the only region that has an outlier, and it is California, which had a suicide rate of 10.70. The highest suicide rate can be found in the western region. The lowest suicide rate can be found in the northeast. The midwest and the south had similar suicide rates.

Figure 3: Region and the 2019 Suicide Rate

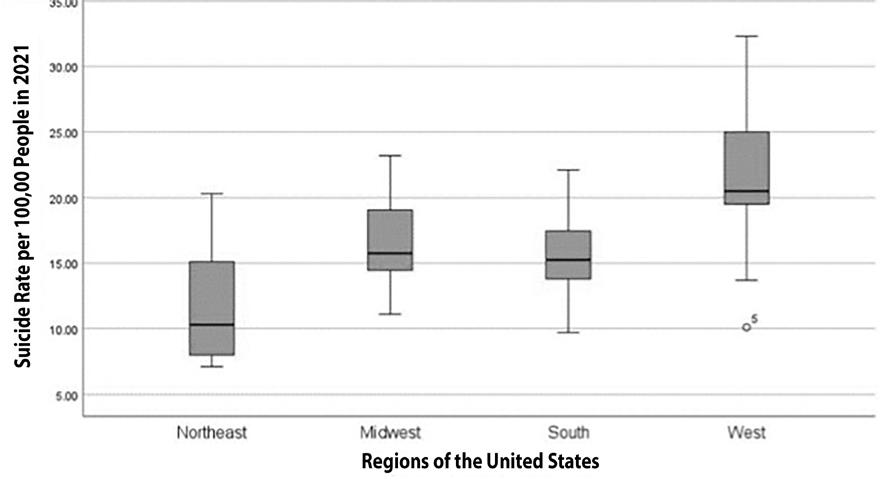

Figure 4 is a boxplot that shows the suicide rate in 2021 by region. The boxplot displays the median values of each region. The northeast has a median of 9, the midwest has a median of 12, the south has a median of 16, and the west has a median of 13. The west is the only region that has an outlier, and it is California, which had a suicide rate of 10.10. The highest suicide rate can be found in the western region. The lowest suicide rate can be found in the northeast. The midwest and the south had similar suicide rates.

Figure 4: Region and the 2021 Suicide Rate

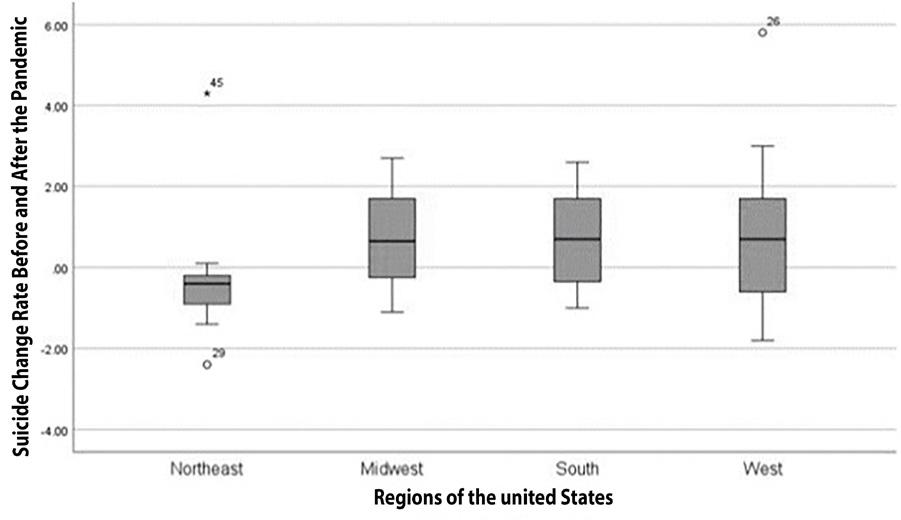

Figure 5 is a boxplot that shows the suicide change rate before and after the pandemic. The boxplot displays the median values of each region. The northeast has a median of 9, the midwest has a median of 12, the south has a median of 16, and the west has a median of 13. The northeast had two outliers, which were New Hampshire and

Vermont. New Hampshire had a change rate of -2.40, while Vermont had a change rate of 4.30. The west also had an outlier, which was Montana. Montana had a change rate of 5.80. The highest suicide change rate can be found in the west. The lowest suicide change rate can be found in the northeast. The midwest and the south had similar suicide change rates.

Figure 5: Region and the Suicide Change Rate

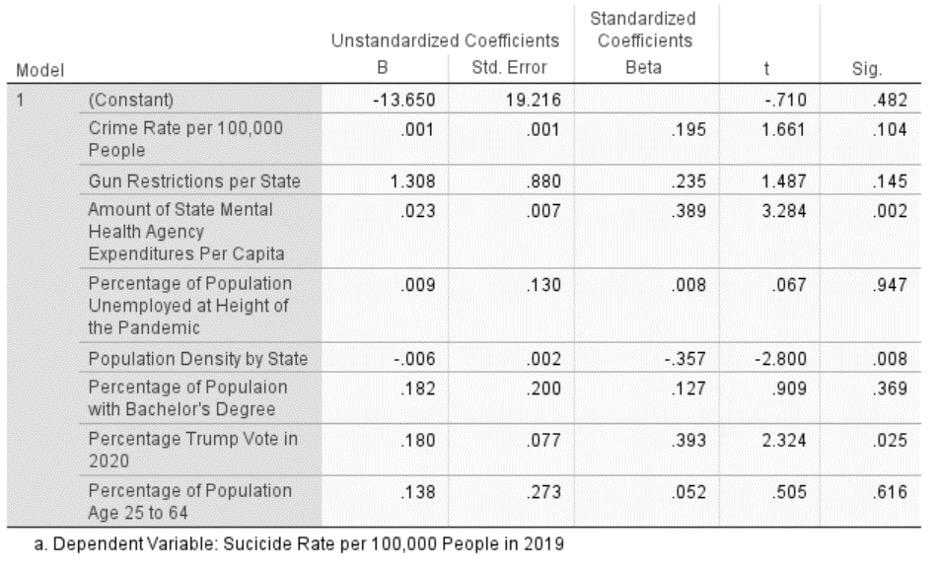

The multivariate regression analysis in Table 3 reveals that independent variables explain 64.3 percent of the variance in the 2019 suicide rate. The multivariate regression analysis also revealed that the crime rate, percentage of the population unemployed, percentage of the population with a bachelor’s degree, gun restrictions, and percentage of the population aged 25 to 64 were not statistically significant. The percentage Trump votes was significant at p<.05. The amount of state mental health agency expenditures per capita and population density was significant at p<.01. As population density decreases, the suicide rate increases. As the amount of state mental health agency expenditure per capita increases, the suicide rate also increases. As the percentage of Trump votes in 2020 increases, the suicide rate also increases.

Table 3: Multiple Regression Analysis 2019 (Pre-Pandemic)

R-squared=.643 N=50 *p<.05, **p<.01

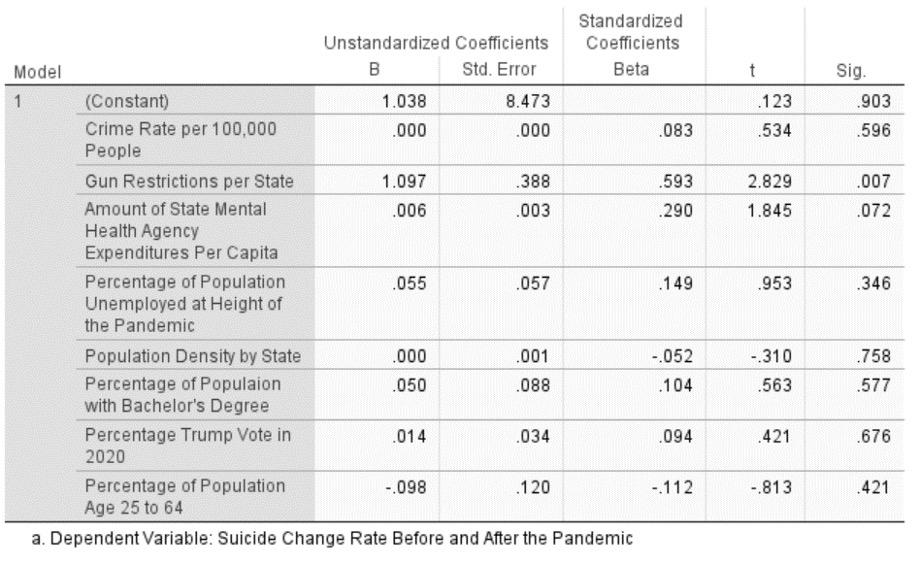

The multivariate regression analysis in Table 4 reveals that the

independent variables explain 67 percent of the variance in the 2021 suicide rate. The multivariate regression analysis also revealed that the crime rate, percentage of the population unemployed, percentage of the population with a bachelor’s degree, percentage of the population aged 25 to 64, and gun restrictions were not statistically significant. The Trump vote was significant at p<.05. The amount of state mental health agency expenditures per capita and population density was significant at p<.01. As population density decreases, the suicide rate increases. As the amount of state mental health agency expenditure per capita increases, the suicide rate increases. As the percentage of Trump votes in 2020 increases, the suicide rate increases.

Table 4: Multiple Regression Analysis 2021 (Post-Pandemic)

R-squared=.67 N=50 *p<.05, **p<.01

The multiple regression analysis in Table 5 reveals that the independent variables explain 37.4 percent of the variance in the suicide change rate before and after the pandemic. Table 5 revealed just one statistically significant variable. As states become less restrictive on guns, the change in the suicide rate increases.

Table 5: Multiple Regression Analysis of the Suicide Rate Change

R-squared=.374 N=50 *p<.05, **p<.01

Conclusion

The results of this study found support for H3 (as the gun restrictions increase, the suicide rate will decrease) in relation to the change in the suicide rates from 2019 to 2021; and H6 (as the population density decreases, the suicide rate will increase) for the suicide rates in 2019 and 2021. A decrease in suicide rates was witnessed as states became more restrictive on gun laws, while an increase in suicide rates was witnessed as the population density decreased. Support for H1 (as the percentage of the vote for Trump increases, the suicide rate will increase) was found in the suicide rate of 2019 and 2020, but not for the change variable of the suicide rate.

This study rejects H4 (as the amount of state mental health agency expenditures per capita increase, the suicide rate will decrease) as the opposite was found. In both the 2019 and 2021 suicide rate, the opposite of the hypothesis was found. This was not as significant in the change variable of the suicide rate.

On the other hand, this study accepts the null hypothesis for H2 (as the crime rate increases, so will the suicide rate), H5 (as the percentage of population unemployed at the height of the pandemic increase, the suicide rate will increase), H7 (as the percentage of the population with a bachelor’s degree increases, the suicide rate will decrease), and H8 (as the population percentage age 25 to 64 decreases, the suicide rate will increase).

The boxplot findings on regions found interesting results for all dependent variables. The west demonstrated the highest median value for each dependent variable, while the northeast had the lowest median on each variable. California stood out in both 2019 and 2021 as a significant outlier for its region.

Significantly, support for H6 (as the population density decreases, the suicide rate will increase) was important for this study. As previously stated, suicide rates have historically been lower in urban areas than in rural areas. Support for H3 (as the gun restrictions increase, the suicide rate will decrease) relates to state policies and gun laws. The results of this study suggest that gun control regulations can reduce suicides rates based upon an analysis of those rates across the American states before and after the pandemic. Even though H1 (as the percentage of the vote for Trump increases, the suicide rate will increase) was not significant in the change variable, it still showed evidence of a relationship between state political culture and the suicide rate in 2019 and 2021. This is extremely intriguing because Republican support tends to be higher among residents of rural areas and in states with less restrictive gun laws. When looking at the results, this is significant since it shows a potential relationship between the variables that were statistically significant in this study.

In future studies, it would be more intriguing to take a qualitative approach and utilize survey research to measure people’s feelings and attitudes during the pandemic. Future research should look into other independent variables such as different age groups, income levels, race, levels of religiosity, rates of therapy visits, and more crime data. Additionally, I would propose that future researchers explore the change variables more extensively across states while incorporating new independent variables. Furthermore, it would be intriguing to investigate particular states such as Wyoming, which has the highest suicide rate in the United States, and California and New Jersey, which have the lowest rates of suicide.

References

American Addiction Centers Editorial Staff. (2023). Mental Health Spending By State Across the US. American Addiction Centers. Retrieved from https://rehabs.com/ explore/mental-health-spending-by-state-across-the-us/ Boor, Myron. “Effects of United States Presidential Elections on Suicide and Other Cases of Death.” American Sociological Review, vol. 46, no. 5, 1981, pp. 616–18. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2094942. Accessed 24 June 2025.

CDC. (2023). Stats of the states. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/ stats_of_the_states.htm

Classen, Timothy J., and Richard A. Dunn. “The Politics of Hope and Despair: The Effect of Presidential Election Outcomes on Suicide Rates.” Social Science Quarterly, vol. 91, no. 3, 2010, pp. 593–612. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42956420.

CNN. (2020). Election Results. Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/election/2020/ results/president

Georgia Department of Public Health. (2023). Understanding the Opioid Epidemic. Retrieved from https://dph.georgia.gov/document/document/cdc-han-00438pdf/ download

Hicks, Vitro, Johnson, Sherman, Heitzeg, Durbin, & Verona. (2023). Who bought a gun during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States? National Institutes of Health. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10464976/

Katella, K. (2021). Our Pandemic Year—A COVID-19 Timeline. Yale Medicine. Retrieved from https://www.yalemedicine.org/news/covid-timeline

Katella, K. (2020). Taking Your ‘Mental Health’ Temperature During COVID-19. Yale Medicine. Retrieved from https://www.yalemedicine.org/news/mental-healthcovid-19

Kohrt, B. (2022). Impact of Social Isolation during the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health, Substance Use, and Homelessness. National Institutes of Health. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9566547/

Paul, J., & Coakley, T. (2023). State Gun Regulations and Reduced Gun Ownership are Associated with Fewer Firearm-Related Suicides Among Both Juveniles and Adults in the USA. ScienceDirect. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/ article/abs/pii/S0022346823000076

Phillips, J., & Hempstead, K. (2017). Differences in U.S. Suicide Rates by Educational Attainment, 2000-2014. PubMed. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih. gov/28756896/

Shaw, M., Dorling D., Davey Smith G. “Mortality and political climate: how suicide rates have risen during periods of Conservative government 1901-2000.” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health (1979-) , Oct., 2002, Vol. 56, No. 10 (Oct., 2002), pp. 723-725 https://www.jstor.org/stable/25569811

Sher, L. (2020). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicide rates. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine. Retrieved from https://academic.oup.com/ qjmed/article/113/10/707/5857612

Statista. (2020). Crime rate in the United States in 2020, by state. Retrieved from https:// www.statista.com/statistics/301549/us-crimes-committed-state/

Stone, D., Jones, C., & Mack, K. (2021). Changes in Suicide Rates — United States, 2018–2019. National Institutes of Health. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. gov/pmc/articles/PMC8344989/

COVID

The Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2023). Data Center. Retrieved from https://datacenter. aecf.org/

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2023). COVID-19 Economic Trends. Retrieved from https://data.bls.gov/apps/covid-dashboard/home.htm

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2022). Labor Market Dynamics during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/blog/2022/labor-market-dynamics-during-the-covid-19-pandemic.htm

U.S. Census Bureau. (2023). Population Density Data. Retrieved from https://www2. census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial/2020/data/apportionment/population-density-data-table.pdf

The Scope and Nature of White-Collar Crime in The United States: A Review of Cases from the FBI’s database

on Fraud and Embezzlement

By Sabrina Maine

Faculty Mentor: Dr. Rudy Prine, Department of Criminal Justice

Article Abstract:

This article explores the concept of white-collar crime, focusing on the emergence and evolution of fraud during the COVID-19 pandemic and the prevalent issue of embezzlement in business settings. White-collar crime, a term coined by Edwin Sutherland in 1939, refers to illegal activities carried out by individuals in positions of power and respectability, typically within the context of their employment. This study analyzes 14 distinct cases, split between COVID-19 relief fraud and embezzlement, highlighting the types of crimes committed, their impacts on businesses and the government, and the legal consequences faced by offenders. Key findings show that wire fraud and contract fraud were the most common forms of white-collar crime identified, often involving small business owners misusing government aid for personal gain. The analysis of embezzlement further emphasizes the role of high-ranking employees in perpetrating financial crimes within their organizations. The article concludes with recommendations for preventing such crimes in the future, including the need for stricter oversight on government relief funds and heightened vigilance in corporate financial management.

Introduction

The term “White-collar Crime” was coined in 1939 by Edwin Sutherland, who introduced the concept as, “crime committed by a person of respectability and high social status in the course of his occupation” (Payne, 2021, p. 2-3). He was calling attention to the fact that crime can be committed by the social elite, not just the lower classes. Today, we recognize a plethora of different types of white-collar crimes as the scope of the crime keeps evolving with technological advances in hacking, phishing, and malware attacks. There are three factors that are needed to qualify a crime as white-collar. First, the context of the crime must be related to one’s employment and the perpetrator should be from an elite social and economic status. Secondly, the person’s occupation must play a central role in the crime. For example, a murder in the workplace does not constitute a white-collar crime. Last, the occupation must be legitimate. Dealing drugs is an illegitimate business, so that example would not count as white-collar crime (Payne, 2021, p. 2-3). To summarize, the person committing the crime must have a legitimate job and they must use their job to break the law.

White-collar crime is seen as an “umbrella” term due to its many sub-groups. For example, both embezzlement and identity theft can be a white-collar crime if it is in the context of the workplace. However, it is hard to tell what counts as a white-collar crime; there is no database that strictly analyzes it. This article will provide a database using a few different cases to demonstrate what constitutes white-collar crimes, the various forms of white-collar crime, and give an accurate picture of the type and frequency of white-collar crime. Then it will discuss how we can learn from these cases, white-collar crime effects, and how we can implement ways to prevent white-collar crimes in the future.

This article began as an assignment from a professor who aimed for us to develop a database on white-collar crimes, which was the topic of the course. Using the FBI database, I discovered that the most frequently reported cases involved COVID-relief fraud and embezzlement. These cases highlighted the diverse range of individuals who engage in fraudulent activities. I chose to focus on these particular cases due to my interest in the topic and the varied profiles of white-collar criminals. The original intent was to include more cases, however, in order to meet the deadlines of the course, a decision was made to stop at 14. This allowed for a sufficient sample size to examine both the similarities and differences in the crimes committed, without overwhelming the scope of the research.

Case Summaries

Fraud via COVID-Relief Programs

Our first set of cases involve fraud related to COVID-19. This is

an important economic issue as noted by Amanda Stapleton, a faculty member of Science in Financial Crime at Utica University. Explaining how the pandemic has affected business fraud, she writes, “In a recent Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE) study, 77% of participants said that fraud has increased since the pandemic started and that they anticipate this tendency to continue” (Stapleton, 2022, p. iii). Since there was an increase in government aid (COVID-19 relief) to Small Business Association (SBA) programs like EDIL (Economic Injury Disaster Loans) and PPP (Paycheck Protection Program), they were abused and defrauded. An estimated total of $25 billion was expected to have been stolen from the government from these programs (Stapleton, 2022). Stapleton elaborates further, “The government assisted 62% of enterprises, comprising roughly $5.2 million in the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans with a combined value of over $525 billion. Due to the unusually high number of recipients and the scant scrutiny of applications, fraudsters could take advantage of the system and get ‘free money’ for their benefit” (Stapleton, 2022, p. 3). In a time when small businesses needed help the most, a portion of them got greedy and took advantage of the system. The combination of easy accessibility to these loans and high number of recipients further shows why such a high amount of crime occurred and money stolen. To elaborate, here are seven examples of wire fraud and/or contract fraud via COVID relief funds to analyze the similarities and differences of the crimes.

Lancaster man sentenced for COVID relief fraud

Our first set of cases involves fraud related to COVID; this is an important issue as noted by the FBI’s website. Two brothers from Lancaster, NY committed bank and wire fraud by filing fraudulent loan applications to a COVID relief fund program. PPP was meant to forgive payroll debt for businesses that could not support their payroll costs post-COVID. Larry Jordan, according to court documents, submitted eight fraudulent PPP applications on behalf of companies he and his brother owned or controlled. These applications stated that the company 5 Stems Inc. (owned by Jordan) had 194 employees and over $200,000 in payroll. In reality, only nine employees were working there and had less than $54,000 in payroll deposited. Some of the money was used for the defendants’ own investments, as well as personal expenses and home improvements. Larry Jordan has been sentenced to 18 months in prison. His brother Curtis Jordan has been convicted and awaits sentencing.

Spokane Dermatologist Indicted for Using Approximately $1.5 Million in COVID-19 Relief Funds to Buy Arizona Home, Sports Cars, and Other Properties

In this case a dermatologist was caught fraudulently obtaining and

using approximately $1.5 million in COVID relief funds to purchase luxury sports cars, buy real estate, and pay off personal debt. When President Biden signed the CARES Act (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security) it provided several programs through which eligible small businesses could request and obtain relief funding intended to mitigate the economic impact of the pandemic for small and local businesses. William Philip Weschler abused the CARES Act when he used a loan from the act that was meant for legitimate business expenses rather than for his personal enrichment. He was indicted by a grand jury for these fraudulent charges.

Lehigh Acres Man Indicted for COVID Relief Fraud

The CARES Act supported an Economic Injury Disaster Loan (EIDL) that could be used to provide economic relief to small businesses postCOVID. This loan could be applied to any normal operating expenses like rent, payroll, utilities, etc. Thakur Sukhdeo faces a maximum penalty of 30 years for fraudulently collecting EIDL revenue for his personal enrichment. His company J.R. Handyman Pro’s LLC was registered to receive $414,000 from EIDL, but the payments went to a luxury car and truck in his name. His indictment led to many counts of wire fraud and illegal monetary transactions.

First Feeding Our Future Defendant Sentenced to 12 Years in Prison

A popular COVID support program called “Feeding Our Future” has reportedly been abused by Mohamed Ismail, the owner and operator of Empire Cuisine and Market LLC. His restaurant participated in creating false documents claiming that they had served a certain number of meals to in-need children and had used their restaurant’s resources to do so. The Feeding Our Future program, created due to the COVID-19 pandemic, would then reimburse the restaurant for serving meals to underserved children. Each of the rosters given to the program by Ismail were fabricated by using fake names. Judge Brasel of the US District court of Minnesota had this to say in court, “The taxpayers in Minnesota are rightfully outraged by the brazenness and the scope of [Ismail’s] crime. The evidence at trial was frankly breathtaking.” Overall, Ismail received $40 million in fraudulent Feeding Our Future funds. This will result in 144 months in prison and half a billion dollars in restitution.

Baltimore woman pleads guilty to COVID fraud

In Baltimore, Maryland, a woman named Nina Williams has pled guilty to wire fraud. Within her crimes she had falsified applications for both PPP COVID-relief loans and EIDL on behalf of Nimiche Inc. and Nimiche Interiors Inc. Both applications were accepted by

the PPP, and the businesses received just over half a million in loans. However, Williams pocketed every cent the government gave her for the businesses into personal-related expenses and not to the company’s payroll. She collaborated with a small team to submit more fraudulent PPP and EIDL loan applications to another bank. In total, she made at least $1.5 million from both loans. She faces a maximum penalty of 20 years in prison and $250,000 in restitution.

Businessman Pleads Guilty to Theft of Pandemic Relief Funds

Jesse Lelievre was the owner and manager of one of these small businesses who applied for the loan. This business was named “Paramount Plumbing & Heating LLC.” To obtain the loan, Lelievre met with the SBA and drafted an agreement to use the loans for the working capital of his business; this can include payroll, rent, utilities, etc. However, he directed funds he applied for into his personal accounts to buy items like a diamond ring and home decor. Due to this misappropriation of COVID-19 relief funds he will end up in prison. The sentence has not yet been announced; however, he has pleaded guilty. On May 17th, 2021, the Attorney General established the COVID-19 Fraud Enforcement Task Force in Massachusetts to enhance efforts to combat and prevent pandemic-related fraud such as this one.

Indianapolis Woman Sentenced to Prison for Submitting Fraudulent COVID-19 Relief Loan Applications

Not only are businesses using COVID-19 relief aid for their personal benefit, but people from the government are helping them do it, with a small fee, of course. Antranette Echols has recently been sentenced to prison for 12 months and a day due to her contributions to COVID-19 relief fraud. Echols worked for the SBA (Small Business Administration) and submitted falsified COVID-19 relief loans on behalf of the business borrowers and was given a fee in exchange for her work. She was ordered to pay $373,690 to several financial firms and the SBA, who were the victims of this fraud upon her conviction. Her sentence had not been given yet, but the highest sentence for wire fraud is anywhere from twenty to twenty-five years. Since she has used her legitimate job to commit an illegal act for personal gain, this qualifies as whitecollar crime.

Fraud embezzlement

Our other set of cases involves embezzled funds. Embezzlement is the act of stealing money from your company by using false financial reporting, lying about assets, and “cooking the books” (Payne, 2021). A research paper written by Ha-yeon Park (et al.) states that “60% of corporations filed for bankruptcy after suffering from embezzlement.” This means many companies are dying due to the rise of embezzlement

even among small businesses. There are many factors at play when discussing why embezzlement happens. A large portion of the fraudsters have a prominent position in their company (Park et al., 2017, p. 376). This is mainly because to get away with the false reporting, falsified checks and deposits, and “cooking the books” you must have access to those financial systems. Only those in higher positions have the opportunity to do such things and hide the evidence.

The fraud triangle is a model that explains the three parts of committing fraud: pressure, opportunity, and rationalization (Crumbley et al., 2021). To summarize, the process of committing fraud includes mental motivation to do so, an opportunity to cheat the system, and justifying the act to suppress guilt before they commit the crime. Other similar fraud models add ego as another main factor and according to research the majority of people who embezzle do use the money for personal gain (Crumbley et al., 2021). This model does a good job of explaining why embezzlement happens. Looking at the data, we can see the fraud triangle unfolding on a lot of the CEO/CFO/business owners and accountants who commit it. The correlation between high-position employees and the rate of embezzlement is furthered in the following seven case summaries.

Former CFO Sentenced to 41 Months in Prison for Embezzling $2 Million

Our second set of cases involves embezzling; this is an important issue as noted by the FBI’s website (2016). Between approximately January 2019 and January 2024, Richard Zellner, the former CFO of a minor company in St. Louis Missouri, had been using his employer’s bank accounts to pay off personal credit card debt. His expensive lifestyle added up quickly by purchasing vacations, travel tickets, gold, and precious metals, so that when the charges would go above $1000 on his credit cards, he would use his position to make his business pay for it. He would cover up his theft by creating fake work orders and bills on the company’s accounting records. Since he was the CFO, he had access to all of the financial statements and had the influence of his position to not get caught. Zellner had spent over $2,000,000 in fraudulent transactions through his business. He pleaded guilty in August 2024 to one count of wire fraud.

Former Chief Executive Officer of Chicago Hospital Added to Federal Indictment Alleging Corruption and Embezzlement

A Chief Executive Officer of Chicago hospitals has recently been alleged to have embezzled money from his hospital. According to the indictment, George Miller had been conspiring with other hospitals to steer vendor contracts to certain medical supply companies in exchange for cash from the vendor companies’ owner Sammer Suhail. Basically,

he was getting a kickback for recommending a certain vendor to smaller companies. Furthermore, the hospital had been issuing payments to those same vendor companies for goods and services that they knew were not being provided. As it turns out many of these vendor companies were created by Suhail and the deposits went directly into his pocket. Suhail had been indicted earlier the same year for embezzlement and money laundering on separate charges. However, Miller continued to work with them to receive his kickbacks for supporting Suhail’s fraud. Suhail paid Miller a share of $19 million in payments that he received from the hospital in return for Miller and Ahmed steering those contracts and business to him. Although there is no conviction yet, the evidence against him is considerable. Currently he is waiting for court.

Former Health Care Manager Sentenced to Prison for Embezzlement Scheme

In the health care field, it is of the utmost importance to focus on the quality of care for your patients; however, Emiliya Radford of Warner Robins, Georgia, decided that one thing was more important: money. She was an office manager of Smith Spinal Care Center (SSCC) and had the responsibility of issuing and signing all the bi-weekly checks, including her own. She had a side business of her own as well, Cyber Pinecone, a marketing company. Without the permission of her employers, she wrote and endorsed Cyber Pinecone for marketing work for around $200,000 and gave herself an unauthorized pay raise. She also used the company’s bank account to buy Apple products shipped directly to her house. The company filed for EIDL loans, the COVID-19 loans to small businesses, and a large portion of those funds ended up in Radford’s pocket. In the end, her embezzlement scheme cost the company $200,000 in losses and they had to shut down indefinitely. Radford will pay $298,000 in restitution and serve 66 months in prison.

Falmouth Woman Pleads Guilty to Embezzling More Than $1.3 Million

In the small town of Falmouth Massachusetts, a bookkeeper at a local flooring company pleaded guilty to embezzling one million dollars from her employer. She would write checks to herself from her employer’s bank account and would hide the evidence by not reporting any of the checks in the financial statements. By excluding the funds she embezzled from tax sheets there was a tax loss of $353,000. Due to her actions, she was indicted with wire fraud and filing false tax returns. She then pled guilty, facing up to 25 years in prison and half a million in fines on her sentence; however, the final sentence has not been reported yet.

Anderson Accountant Sentenced to Over Three Years in Federal Prison for Embezzling Nearly One Million Dollars from his Employer

A resident of Anderson, Indiana, Nathaniel Wills, was employed as an accountant and Director of Administration for a business located in the same state. Wills has pleaded guilty to embezzling from his employer. For six years he worked as an accountant for the firm and had been entrusted to perform business with the utmost ethics. However, using his position, he falsified many inventory logs, listed jobs as “unpaid” to earn double, and transferred money to himself from the company, hiding it in fake invoices. Through 120 transactions he stole just less than one billion dollars from Anderson, which resulted in substantial financial hardships for the company. He worked solo and used the money to pay for his gambling. He has been sentenced to 41 months in prison and ordered to pay $877,507 in restitution.

South

Carolina Woman Pleads Guilty To $1.7 Million Embezzlement Scheme

In this case, Ms. Kristen Turney pleaded guilty to embezzling more than $1.7 million via wire fraud. According to documents from the courthouse in Catawba, South Carolina, Turney defrauded her employer to attain the illegal funds. She had access and control over her company’s financial statements and would write checks to herself from them without authorization or approval. At least 1000 checks were written to her before she was caught. She then tried to cover up her accounting by making false entries into her company’s records and lied to her employers about the missing money. The money she wired herself was used for personal expenses like tuition, vacations, mortgage payments, and many shopping trips. Her sentence is not out but she faces up to 20 years for wire fraud and over a quarter of a million dollars in fines.

Former Takeda Employee Sentenced to Nearly Four Years in Prison for $2.5 Million Embezzlement Scheme

Priya Bhambi, a senior employee from Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited has recently been sentenced for her part in embezzling by her employer. Because she was a senior-level and highly compensated employee, she planned a complex financial fraud scheme to steal thousands more for her personal gain. To do this she created a fake consulting business called “Evoluzione,” incorporated it, and then submitted a statement of work to Takeda stating that “Evoluzione” had done a service for them worth $3.5 million. Then she sent payments for fake invoices made by herself and a co-conspirator. In total, $2.3 million was defrauded from Takeda into the personal hands of Bhambi

and her co-conspirator. This was not the first time Bhambi used sham companies to funnel extra money into her accounts; a previous scheme earned her $300,000 for consulting services never provided. The Acting United States Attorney Joshua Levy had this to say about Bhambi’s sentencing, “The sentence sends two strong messages—first, there are very serious consequences for executives who exploit their positions to line their own pockets and second, for companies who are victims of embezzlement, law enforcement stands ready to do whatever it can to recoup stolen funds and hold individuals accountable for fraud against their employers.” She was sentenced to 46 months in prison with a restitution bill of $2,585,480.

Analysis

Overall, I have covered 14 cases, seven covering COVID-19 relief fraud and the other seven covering embezzlements. In all of these cases, we can see that the fraudsters are using their legitimate jobs to break the law. Therefore, they constitute white-collar crime. The effects of the crimes caused millions of dollars to be stolen from companies and businesses. People have been fired or lost their jobs due to this crime, and the government has been taken advantage of—which can limit how much they will allow for future relief loans and increases in application regulations. According to Occupational Fraud 2024: A Report to the Nations, there are three types of occupational fraud (crime in the workplace) and they are asset misappropriation, corruption, and financial statement fraud. Throughout the COVID Relief fraud and embezzlement cases, we saw a lot of asset misappropriation which refers to the money that was meant to keep the business running but was funneled into the pockets of the employees. 89% of all fraud cases are asset misappropriation cases and they result in a medium rate of $120,000 per case (Warren, 2024). These crimes are similar due to their nature of fraud; however, they are different due to the method of stealing. The COVID-Relief cases received their money from defrauding the government while the embezzlers took it from their own company. The most common white-collar crime was by far wire fraud. Wire fraud was used to transfer funds from every embezzlement case and every small business to their personal accounts for their personal use. Contract fraud was also exceedingly high in the cases I analyzed because they had to forge documents to receive funding, which in turn caused charges for contract fraud. These crimes varied from small to massive scales.

Focusing on the COVID-19 relief case summaries, I have noticed a few trends. Of course, all of them were small businesses because the relief loans were targeted towards the SBA (Small Business Administration). To apply for relief loans, businesses were required to have the owner/manager sign off on it, so, as a result, everyone who

was guilty of fraud had to be the owner/manager or had to commit it with their knowledge (Stapleton, 2022). Almost all of the cases I read involved one person committing wire fraud to his/her account, and in all the cases I reported, the fraudster was the owner/manager. All the funds recorded went to payments for luxury items or personal payments, so this was outright corruption which is defined as “the use of political power or influence in exchange for illegal personal gain” (Payne, 2021). The influence that the owners/managers had on their businesses gave them the ability to corrupt it. There are many ways we can limit government relief loan fraud, but not while also allowing it to be easier for businesses to have access to money. You must pick one or the other. As mentioned before, certain task forces have been formed to monitor relief funds and prevent fraud. These work as both a preventative and detective measure towards white-collar crime.

Gender and/or race did not play much of a part when it comes to COVID-19 fraud, however, almost all of them had to be old enough to be the owner themselves so early 30s-late 50s was the average range. The total amount of money involved in these cases ranged from $200,000 to $40 million. The fines paid by the fraudster would only end up being a fraction of the money they stole, which makes sense because they could not possibly pay all of it back if the government took away all their stolen money and they no longer had a job. When someone was found guilty of a crime, the full time that they could have been sentenced to was never given; this is the same among many white-collar crimes of varying severity. Since white-collar crime is not seen as violent, the fraudster is usually only given 1-4 years instead of the full 20-25 years that the law allows.

Throughout the embezzlement cases I noticed two different trends. Either the embezzler was the CEO/CFO/manager, or the embezzler was the head accountant of the business. According to Ha-Yeon Park (et al), “Of 284 embezzlement cases that occurred between 2005 and 2012, the CEO is involved in 181 cases” (Park et al., 2017, p. 384). To get away with embezzlement you must have access to the money and hide the evidence (Park et al., 2017). Only those with a high enough position could do that, so they are more likely to embezzle than a low-level employee. When the operation is on a larger scale with a bigger business or company, I have found that more than one person would be involved in wire fraud (embezzlement). In contrast, if the business was on a smaller scale, then only one person would be in on the embezzlement. The number of victims varied depending on the company. However, these crimes affected whole corporations and did not target anyone individually. The lowest amount of money stolen from a company via embezzlement was $200,000 and the highest amount was around $19 million. The highest someone can be sentenced to for wire fraud is 20-25 years (depending on state), but the highest sentence given was

49 months (around 4 years). This is still a long time, however, if the crimes are as bad as the state says they are, then given the low sentences, deterrence from the crime is not going to work.

Deterrence theory is “based on the assumption that punishment can stop individuals from offending if it is certain, swift, and severe” (Payne, 2021). This theory should work greatly on white-collar criminals because these people are supposedly rational thinkers who are placed high in society with jobs, homes, and most of the time, families. If they know the punishment for their crime is going to certainly be over 20 years, the rate of crime would likely plummet. Furthermore, when the punishment does not match the crime, in this case punishment is far less than the crime, then it will not do a good job at preventing other people from doing the same thing.

When observing if justice was served in these cases, the criminals were given sufficient punishments for their crimes to an extent. However, the full sentence was never given in these cases, which could downplay the severity of being a white-collar criminal. Some people can rationalize stealing millions of dollars for less than 5 years in prison if it pays for their kids’ tuition and/or gets the family out of debt, but 20-25 years is almost unthinkable. The infamous case of company Enron, which includes major accounting fraud and embezzlement scams, the CEO, Jeffrey Skilling, was sentenced to 24 years following his conviction. This is a perfect example of general deterrence in white-collar crime. General deterrence is used to prevent everyone from committing a crime, while specific deterrence is used to prevent that particular person from committing the crime again. Since Skilling got away with so much and put millions in his pocket, he received a high sentence to be used as a deterrent for others who were doing the same. His case was a breakthrough in the white-collar crime field because it showed that even though these criminals have money, are high in society, and have connections, they can still be fully prosecuted. However, in less public cases, no one seems to be charged with such a high sentence. There are many arguments on whether white-collar crime should be punished up to the 20-year mark. Of course, it should mainly depend on how many people are affected by the crime and how much money is stolen. But many of these cases involved counts of fraud that, since the media did not have their eye on it, did not result in high punishments.

Conclusion

Even though white-collar crime is not a violent crime, it is one of the most dangerous overall. As the blockbuster movie The Big Short, which details the bank fraud of the 2008 recession put it: “When the unemployment rate increases by 1%—40,000 people die.” White collar crime has such a huge influence on society because of the amount of money that is taken. It destroys businesses, families, and as the

2008 recession proves, can lead to thousands of people becoming homeless. It is a crime that needs to be taken more seriously by people and prosecuted like they affected people’s lives not just lost money. “Preventing fraud from occurring in the first place is the most costeffective way to limit fraud losses” (Warren, 2024). Some of the most common ways to implement prevention is to ensure proper auditing is taking place within the company and that separation of duties occurs among those employees with control over the accounting access (Warren, 2024).

The fraud triangle could be used as an indicator for white-collar crime behavior; however, by itself, it cannot prevent white-collar crime, only aid in detecting it. In discussing how to improve the system we have to think about how different white-collar criminals are from traditional criminals and what would work better to cater to their rehabilitation. In a research journal by Dr. Vijaykumar Chowbe, he states the following about the future in fighting white-collar crime (WCC), “. . . despite the fact that most of the proceedings of the WCC have been initiated, executed, and criminal proceedings, the WCC needs a different and more stringent treatment and its affect and impact seriously on the social morality and economic fabric . . . it has been held that while considering bail involving socio-economic offenses, stringent parameters should be applied” (Chowbe, 2024, p. 19). Furthermore, embedding a culture of transparency and accountability among companies can be accomplished by being aware of the fraud triangle and characteristics needed to form a white-collar criminal, applying higher sentences to white-collar criminals for deterrence, and increasing government regulations will prevent white-collar crime from happening.

Citations

Chowbe, Vijaykumar Shrikrushna. (2024, March 16). Redefining the Fight Against White Collar Crime: A Moral and Value-Centric Perspective. Available at SSRN: https:// ssrn.com/abstract=4761381 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4761381

Crumbley, D. L., Fenton, E. D., Smith, G. S., & Heitger, L. E. (2021). Forensic and investigative accounting. Wolters Kluwer. FBI. (2016, May 3). News. FBI. https://www.fbi.gov/investigate/white-collar-crime/news McKay, A. (2015). The Big Short. Paramount Pictures. Payne, B. K. (2021). White-Collar Crime (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc. (US). https:// reader2.yuzu.com/books/9781071833926

Park, H., Lee, A., & Chun, S. (2017). Asset Embezzlement and CEO Characteristics. Google Scholar. http://kmr.kasba.or.kr/xml/25559/25559.pdf

Stapleton, A. (2022). The Financial Fraud Epidemic and How It Has Changed Business Fraud. Utica University ProQuest Dissertations & Theses.

Warren, J. (2024). Occupational fraud 2024: A report to the nations. Association of Certified Fraud Examiners. https://vsu.view.usg.edu/content/enforced1/3228983CO.510.ACCT3100.26514.20254/VSU_eDegree_Course_Content/Module%20 5/2024-Report-to-the-Nations.pdf?isCourseFile=true&ou=3228983

Una ventana a la realidad femenina en la literatura hispana / [A Window to the Feminine

By Meghan Barnett

Reality in Hispanic Literature]

Faculty Mentor: Dr. Ericka Parra, Department of Modern and Classical Languages

Resumen:

Los temas y opiniones sobre la identidad estudiados en la literatura Hispana reflejan las percepciones de la cultura y de la sociedad de cada época. La literatura hispana representa cómo su sociedad y el mundo valoran y experimentan los roles de las mujeres. La autora chilena Isabel Allende, en el cuento “Dos palabras” (1989) se inspira en un cuento chino sobre un guerrero convertido en político que es cautivado por una mujer y sus palabras, revelando cómo las mujeres son representadas a partir de la idealización que ellas experimentan. Entre otros autores y obras hispanas, el drama del chileno Sergio Vodanovic “El delantal blanco” (1956), el cuento del cubano José Martí “La muñeca negra” (1889) y el poema de la mexicana Rosario Castellanos “Kinsey Report” (1975) revelan las percepciones sociales sobre las mujeres en la sociedad a través de los personajes femeninos y los problemas que resultan de los constructos de género. Este ensayo, en español, analizará cómo se idealiza, envilece y cosifica a las mujeres a fin de invitar a los lectores a reflexionar sobre estas representaciones y contribuir al cambio de estas percepciones.

[English Translation: Article Abstract:

The themes and opinions that are present in Hispanic literature reflect the greater perceptions of the culture in which it is written and of society. In this manner, it can be seen that Hispanic literature reflects the perceptions of Hispanic society and the world regarding the value and roles of women. The Chilean author Isabel Allende in the short story “Dos palabras” (1989) tells a tall tale of a warrior turned politician who is captivated by a woman and her words, revealing one view on the role of women, the idealization that they experience. Other Hispanic authors and works, such as the Chilean Sergio Vodanovic drama El delantal blanco (1956), the Cuban José Martí short story “La muñeca negra” (1889) and the Mexican Rosario Castellanos poem “Kinsey report” (1972) reveal other perceptions of women in society and the problems that result from these perceptions. This essay in Spanish will discuss how the ways that women are romanticized, villainized, and objectified are found in the literature of Hispanic society and encourages the reader to participate in changing these perceptions

Barnett

Introducción

La literatura es una ventana. Con solo palabras, un autor puede ofrecer una perspectiva de la experiencia humana de una manera sin igual. Incluso un cuento que parece muy simple puede tener influencia social. Sin embargo, los autores que escriben con una misión o una razón específica tienen aún mayor poder. A través de las obras literarias: poemas, cuentos, novelas, y dramas, los autores transmiten sus perspectivas, sus verdades, y experiencias de vida. Pero sus relatos no terminan aquí: las personas habitan el mismo mundo y están conectadas por una experiencia compartida. De esta manera, expresan aspectos universales de la experiencia humana.

Las historias de una persona en un tiempo y un lugar determinados pueden interconectarse con alguien de otra época y otro lugar completamente distinto. El impacto y la importancia de la literatura no están limitados por su contexto histórico o geográfico; más bien, puede revelar la verdad de su pasado, presente, y futuro a la humanidad. Este es el poder de la literatura. Este poder tiene una relevancia especial respecto a la experiencia femenina. A lo largo de la historia, las mujeres han experimentado opresión, discriminación, y luchas que los hombres no han experimentado. Aunque la sociedad ha progresado, las mujeres siguen viendo reflejadas sus circunstancias en la literatura del pasado. Incluso en aquellas historias en que los autores no intentan apoyar ni cambiar las circunstancias contra la opresión hacia las mujeres, las representaciones de imágenes y personajes femeninos revelan su realidad. De manera intencional o no, la literatura ofrece un panorama de la condición femenina.

Este ensayo examina cómo la literatura hispana revela una tendencia persistente a idealizar, envilecer y cosificar a las mujeres.

A través del análisis del cuento “Dos palabras” de Isabel Allende, del drama El delantal blanco de Sergio Vodanovic, del cuento “La muñeca negra” de José Martí, y del poema “Kinsey Report” y su interconexión con los textos contemporáneos y experiencias reales, este trabajo busca fomentar una reflexión crítica que contribuya a una sociedad más equitativa y justa de la identidad femenina.

Dos palabras

En el cuento “Dos palabras”, escrito en 1989 por la chilena Isabel Allende (1942), narra la historia de Belisa, una mujer que aprende el poder de las palabras y las utiliza para salvarse de circunstancias adversas de la vida y de ser cautivada por un hombre. En la historia, las palabras de Belisa ayudan a un coronel a obtener un puesto en el gobierno y lo llevan a enamorarse de ella. Esta historia de amor muestra a una mujer empoderada, pero también idealizada. Con su habilidad y talento con el lenguaje, Belisa tiene el poder para hacer todo lo que

desea y, también, el cariño del coronel. Ella es representada como una figura dotada con habilidades sobrenaturales y como una amante: objeto de devoción.

Jorge Chavarro discute que, en este cuento, “H[h]ay dos fuentes del poder de Belisa: su belleza física [y el] poder derivado de su racionalidad en el dominio del discurso” (citado en Comfort 58). Con este comentario, el autor provee una perspectiva limitada del personaje de Belisa con características idealizadas más que de identidad completa y realista. Belisa se representa como una mujer idealizada por ser hermosa, inteligente, poderosa, sin espacio para defectos en su carácter porque la imagen de la mujer solo es definida por lo que la sociedad considera valioso. En realidad, la identidad de las mujeres es compleja, con virtudes, defectos y luchas. La idealización impone expectativas imposibles y crea una presión injusta.

¿De dónde viene la idealización? Un ejemplo de la idealización de la mujer sumisa a través del tiempo se encuentra en el cuento de hadas “La Cenicienta”, de los Hermanos Grimm. Según Micael M. Clarke, las palabras finales de la madre de la protagonista le indican que debe ser “piadosa y buena” (“pious and good”; mi trad.; 4). Estos rasgos son analizados como las virtudes más importantes para la madre. Y, Cenicienta los mantiene a pesar del abuso de su madrastra y sus hermanastras (4-5). Mientras la madrastra tiene éxito al mantener este carácter sumiso, la hijastra, al final, es tratada como un triunfo que debe recompensarse con un final feliz. Esta perspectiva resulta problemática para las mujeres por ser una idealización. La imagen de que la mujer ideal es sumisa, tierna y pasiva es una forma de idealización común que no debe reflejar la realidad de las mujeres y debe tener fin.

Desde una experiencia de la realidad, Heyder y Kortzak analizan las percepciones de las mujeres en el medio laboral y muestran cómo los estereotipos idealizados se manifiestan en la vida cotidiana. Las autoras argumentan que, “los estereotipos sobre las mujeres las describen como teniendo menos competencia y más calidez, y los rasgos que señalan la calidez son percibidos de la misma manera como femeninos” (S[s]tereotypes about women describe them as usually low(er) in competence and high(er) in warmth, and traits indicating warmth are correspondingly perceived as feminine, thus reflecting the close relationship between warmth and communion”; mi trad.; (Hyder y Kortzak 2).

Esta perspectiva demuestra que, incluso fuera de la literatura, las mujeres son o deben ser tiernas y cálidas, cualidades que se valoran como “femeninas”. Mientras las mujeres pueden tener estas cualidades, es común que ellas experimenten la vergüenza si son más fuertes y menos delicadas. La idealización limita el desarrollo auténtico de las mujeres y perpetúa la desigualdad. Las mujeres deben ser reconocidas y valoradas por su identidad y fortaleza verdadera en vez de una fantasía

social que les exige ser fáciles o agradables.

El delantal blanco

Por otro lado, las mujeres son envilecidas por la sociedad, según lo muestra la obra del teatro “El delantal blanco”, de Sergio Vodanovic (1926-2001), publicada en 1956. El drama representa cómo una mujer rica y su empleada doméstica deciden intercambiar sus roles. La trabajadora se cambia su ropa y su estilo de vida, mientras la señora usa el delantal blanco de la empleada (Vodanovic 23). En el drama se describe que la mujer rica no es una buena mujer sino una persona influenciada por su contexto social. Los lectores aprenden que la mujer rica fue forzada a una relación que no quería porque los hombres que controlaban su vida no ponían valor en su amor sino en la riqueza material y la clase social. Por lo tanto, utiliza su riqueza y sus modales para sentirse bien sobre sus circunstancias al decir: “¡Ah! Lo crees ¿eh? Pero es mentira. Hay algo que es más importante que la plata: la clase. Eso no se compra” (25). Se destaca que es pretenciosa, y que está atrapada. Aunque la actitud de la señora parece ser de villana, es una víctima del sistema patriarcal. Sus circunstancias son complejas porque ella solo es representada como envilecida mientras la trabajadora la engaña para tomar su lugar.

Carlos Gonzáles Hernández examina el reflejo de la opresión al que la mujer da continuidad en su hijo, “Con respecto al patriarcado, la señora exterioriza en la figura de su hijo pequeño, por cuanto lo inculca, constantemente, que tiene una personalidad dominante, y que, es una tradición familiar poseerla” (citado en Comfort 39). La mujer está acostumbrada a los hombres que tienen más fuerza y voluntad que ella. En el mundo de la mujer rica, los hombres hacen las reglas para las mujeres, y las mujeres deben obedecerlas. Esta perspectiva es muy importante para comprender las circunstancias de una mujer con dinero pero sin poder.

Con la mujer idealizada en los cuentos de hadas, la mujer que juega el papel de la villana es un personaje muy común. Hay ejemplos de las madrastras malas y las brujas que llenan estos cuentos simples y viejos, especialmente, cuando son comparados con los ejemplos de la presencia de los hombres malos. La Cenicienta también puede ejemplificar este tipo de mujer con su carácter limitado. Como presenta Micael M. Clarke, la madrastra de la Cenicienta es un personaje sin rasgos complejos (3-5). La madrastra es la enemiga de su hijastra; su odio sin fundamento sólo la lleva a imponerle trabajos sin valor y a utilizarla a su conveniencia (3-5). El personaje de la mujer villana tanto en los cuentos de hadas, como la madrastra villana son inexplicables. Estas imágenes solo muestran los rasgos negativos típicamente dados a las mujeres, como la envidia, la mezquindad, y la brujería. De este modo, las características débiles son típicamente usadas para los constructos de mujeres villanas en la vida real.

Sobre la tendencia de envilecer a las mujeres en la vida real, Jenny Johnston discute el caso de una mujer que experimentaba abuso sexual por su novio. La mujer lo llevó al tribunal para tener justicia (Johnston). El hombre expuso una narrativa que no era verdadera. La víctima, cuenta que él la presentaba como una villana, dudaba de su salud mental, y todavía preguntaba si estaba sufriendo de un trastorno de personalidad (Johnston). Aunque ella era la víctima del hombre, él trataba de culparla. Estas circunstancias han ocurrido casi en toda la historia; las mujeres experimentan abuso y la sociedad encuentra alguna forma de culpar a la víctima, señalándola como una villana.

La muñeca negra