Columbia’s arts continue to shine amidfunding cuts.

‘CAMP’ OUT AT THE MOVIES PAGE 9 SIT DOWN, SEGREGATION PAGE 12

TAKE YOUR HISTORY NEAT PAGE 25

Columbia’s arts continue to shine amidfunding cuts.

‘CAMP’ OUT AT THE MOVIES PAGE 9 SIT DOWN, SEGREGATION PAGE 12

TAKE YOUR HISTORY NEAT PAGE 25

When people ask for a fun fact about me, I usually say I’m a painter. As a child, I created landscape nature pieces using both acrylic and oil paints on canvas. They were my own little worlds — little windows that I could look into — and I loved how I felt when I made them. And while I lost the time and the energy to keep creating as I grew up, I started again in college after I moved to Missouri. When I was homesick, missing Washington State’s mountains and evergreens, I would paint the windows that made me feel at home.

It was like a part of me that I couldn’t describe was finally able to speak. If I had feelings that I needed to work through, painting them out always helped me process, helped me connect with myself, helped me connect with others around me.

Art is essential to human survival. It is something that connects people to each other and to the world. But, it is being threatened. After the National Endowment for the Arts canceled at least $27 million in grants nationwide in May, Columbia’s art scene is feeling to feel the impact. (p. 18). Ragtag Film Society, which operates True/False Film Fest, and the “We Always Swing” Jazz Series lost thousands of dollars in current and future funding.

The attack on the arts isn’t surprising,

Over the last year, I’ve seen just how important the arts are to Columbia. From Art in the Park to True/False Film Fest, arts are everywhere in this town. As someone who loves music, I find this arts-centric community fascinating and beautiful. And it hurts to know the arts are facing turmoil. With grant cuts from the National Endowment for the Arts, many arts organizations nationwide have lost funding, including our very own Ragtag Film Society and “We Always Swing” Jazz Series. But the arts have persisted. Through my discussions with these organizations around the city over the past three months (see the story on p. 18), I’ve learned two important things: The community support is resilient, and the arts aren’t going anywhere. Thank goodness. —Tyler White

though. I can’t tell you how many times as a child I said I wanted to be an artist, just to hear people laugh, or say I would never make any money. I’ve seen Vox Magazine referred to as the “soft news outlet” of the Missouri News Network due to our coverage on the arts, culture and entertainment scene in Columbia.

It’s not just the arts that aren’t taken seriously; it’s any bit of coverage about them. And that is something that I hope to address not only in this letter, but to push back on vehemently as the new editor-in-chief of this magazine.

At Vox, our goal is to serve our community through the coverage of the arts as well as the city’s rich history and the different opportunities that exist, digging deep behind the college town exterior. This is seen in our feature about Columbia’s desegregation in the 1960s and the local group that pushed the movement (p. 12). It’s in our coverage of arts, food and nature destinations that are just a couple hours away (p. 27). And that focus on community, such as the Q&A with Columbia Center for Urban Agriculture’s Adam Saunders (p. 8), is the most important part of the work we do — not only at Vox, but in journalism as well.

As editor-in-chief, it is my goal to advocate not only for the work we do here at Vox and its right to exist, but also for the magazine and our community.

Cayli Yanagida Editor-in-Chief

Vox Editor-in-Chief Cayli Yanagida talks with writer Tyler White about his story for the monthly Behind the Issue segment that airs on KBIA.

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF CAYLI YANAGIDA

MANAGING EDITORS AVERI NORRIS, ALLY SCHNIEPP

DEPUTY EDITOR AUSTIN GARZA

DIGITAL MANAGING EDITOR BRIANNA DAVIS

AUDIENCE ENGAGEMENT EDITOR CLAIRE WILLIAMS

ART DIRECTORS RACHEL GOODBEE, VALERIE TISCARENO

PHOTO DIRECTOR AVA KITZI

MULTIMEDIA EDITOR ARABELLA COSGROVE

PODCAST PRODUCER KIANA FERNANDES

ASSOCIATE EDITORS RACHEL GOODBEE, KATIE GRAWITCH, JAZMYNE MARTINEZ, BROOKE RILEY, CHARLIE WARNER, EMMA ZAWACKI

STAFF WRITERS DAVID ALDRICH, SOPHIE AYERS, ALLI BEALMER, GRACE DEEN, ALEX GOLDSTEIN, AUGUSTUS HENDERSON, MARISSA HORN, JASMINE JACKSON, SOPHIE LINDBERG, MATTHEW OSTHOFF, NEALY SIMMS, ACIYA EL TAJOURY, JACKSON WEST, TYLER WHITE

SOCIAL & AUDIENCE EMMA CLARK, ABIGAIL DURKIN, CHLOE IRELAND-KILLDAY, NEALY SIMMS, PARIS SPENCER

DIGITAL PRODUCERS ALLI BEALMER, LUCIANA DE ANDA, JAKE MARSZEWSKI, CLAIRE POWELL

DESIGN ASSISTANT LAUREN JOHNSON

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS MERCY AUSTIN, EMILY EARLY, EMMA HARPER, GRACE ROMINE

CONTRIBUTING PRODUCER ETHAN DAVIS

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR HEATHER ISHERWOOD

DIGITAL DIRECTOR LAURA HECK

WRITING COACHES CARY LITTLEJOHN, JENNIFER ROWE

FOLLOW US

WANT TO BE IN-THE-KNOW?

Sign up to receive Vox ’s weekly newsletter, the “Vox Insider.” We’ll tell you how to fill up your weekend social calendar and keep ahead of the trends. Sign up at voxmagazine.com.

CALENDAR send to vox@missouri.edu or submit via online form at voxmagazine.com

ADVERTISING 882-5714 | CIRCULATION 882-5700 | EDITORIAL 884-6432

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2025 VOLUME 27, ISSUE 7

PUBLISHED BY THE COLUMBIA MISSOURIAN LEE HILLS HALL, COLUMBIA MO 65211

Cover design: Rachel Goodbee

Cover photography: Lily Mantel

05

Joy and community

Meet the people countering hate with heart at Mid-Missouri PrideFest, which celebrates 25 years.

07

Vox Picks

Stomp on grapes, jam out or waltz into 19th century England this fall. 08

Hyping the harvest

Columbia Center for Urban Agriculture co-founder Adam Saunders discusses Columbia’s relationship with gardening.

Whatcha gonna watch?

Go behind the scenes of Tragically Ludicrous and Jordon Kays’ movie picks ahead of its anniversary show.

11

‘B’ there or ‘B’ square

The Biscuits, Beats & Brews are bountiful at this annual music festival at Cooper’s Landing.

Learn about CORE, the group that used nonviolent protests to help end segregation in downtown Columbia.

State of the arts

In light of recent budget cuts, the Columbia art scene demonstrates unity.

+ DRINK

BBQ snob’s guide to Columbia burnt ends

Hunt down these mouth-watering Columbia bites that are worthy of KC barbecue fanatics.

from something old

History and whiskey intertwine in Magnolia’s Whisky & Wine Bar.

Get outta town — but not too far

Put on your explorer hat and adventure within a two-hour distance of Columbia.

Mid-Missouri PrideFest honors its 25th anniversary with a triumphant claim to any detractors: We’re not going anywhere.

BY KATIE GRAWITCH

Since 1999, Mid-Missouri PrideFest has brought queer joy to Columbia. The festival has grown to include booths from local vendors and artisans alongside musicians by day and drag performers by night. In 2022, the festival doubled its surface area, with over 200 vendors sprawling across two city streets.

As the fest approaches its 25th anniversary celebration Oct. 4-5, the Trump administration has made sweeping changes that threaten LGBTQ+ people around the country, emphasizing major cuts to anti-discrimination policies

and targeting the rights of transgender people. Missouri’s former Attorney General Andrew Bailey, who was recently appointed co-deputy director of the FBI, filed emergency rules in 2023 effectively banning gender-affirming care in the state for nearly a month.

During the 2025 legislative session in Missouri, the American Civil Liberties Union was tracking 38 anti-LGBTQ+ bills at the state level, including restrictions to gender-affirming care, barriers to accurate IDs, curriculum restrictions and limits on drag performances in the

Queer history and joy will be central themes of this year’s Mid-Missouri PrideFest. The event started in 1999 and has welcomed thousands of attendees each year, including this couple (above) in 2014, the year before samesex marriage was legalized nationwide.

presence of minors. In addition to antiLGBTQ+ pushback in the state’s legislative branch, Gov. Mike Kehoe issued an executive order in February banning the use of state funds for DEI initiatives. Janet Davis has been the president of Mid-Missouri PrideFest for the last four years. Amid a wave of anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment, she has overseen numerous expansions to the festival, including the addition of a pride parade in 2022. She says the festival isn’t going away anytime soon. “I think it’s important, especially with where we’re sitting at now polit-

ically, that we’re in the prime moment to not make it a negative thing, but to remind people why we’re here,” Davis says.

“Fall into pride” this October

This year’s theme is Fall into Pride, which is meant to encourage Missourians to embrace queer history and community. The festival is welcoming drag queen Optimus Prime back to the Rose Park stage alongside RuPaul’s Drag Race headliners Mistress Isabelle Brooks and India Farrah with local band Find Fiona.

In recent years, the festival has made strides to become “the most inclusive Pride event,” says organizer and past festival president Steven DeVore. He says the festival has incorporated sign language interpreters and offered quiet instrumental music in the early hours of the fest to reduce overstimulation.

Davis says “fall into pride” means festivalgoers can lean on the event as a constant source of queer joy, even — and especially — when the going gets tough. “I’ll do this for free forever if I have to,” Davis says. “We’ve got your back. We’ll have it in my backyard! I don’t care. But it’s not going anywhere.”

Embracing queer history

One of the biggest logistical changes to PrideFest this year is the addition of a history scavenger hunt. It will walk players through notable moments in PrideFest’s past. Davis says she hopes the hunt will encourage more festivalgoers

to consider the history of queer rights in Columbia. “It’ll teach a lot more people about why we’re here, why we’ve been here, how long we’ve been here and (the festival’s) purpose,” she says.

In the eight years since Davis joined the PrideFest team — originally as a photographer — the festival has grown from about 3,000 annual attendees to over 10,000 attendees across two city blocks. PrideFest’s first annual event in 1999 was a small, one-day picnic in Bethel Park with a handful of attendees. The festival moved to Rose Park in 2015 and expanded to two days in 2021.

Of all of her accomplishments as president of PrideFest, Davis says the memory of the festival’s first pride parade in 2022 holds special significance. “I just went to the top of Broadway at the top of the hill and sat on top of a golf cart, and I could see it come up the hill and go all the way down and back around, and I just sobbed,” Davis says. “That moment, I was like, ‘We’re here. This is it. We really are here.’”

DeVore served as committee chair of the festival from 2018 to 2020. He remained co-chair until 2022, when Davis became president. As the person who ushered PrideFest through the pandemic, the expansion to two days and a partnership with (and eventual split from) The Center Project, he says the scavenger hunt honors the many eras of the festival. “Much like Taylor Swift, a trip down our ‘memory lane’ really is a snapshot of our eras,” DeVore says. “Looking back now, I see how truly blessed we are to have a community that embraces us and pours their heart and soul into this event.”

“PrideFest is about our future”

Mid-Missouri PrideFest’s vendors regale festivalgoers with armfuls of merchandise: pride flags, food samples, stickers, glitter, temporary tattoos and one-ofa-kind poems, to name a few. But two of the festival’s most cherished vendors provide something you can’t take with you — they deal in hugs.

Art and Amanda Smith are Millersburg residents who travel to PrideFest every year to give out free mom and dad hugs, high-fives and fist bumps. Amanda Smith was inspired after seeing anoth-

Marking its 25th anniversary amid federal and statelevel threats to LGBTQ+ rights, the festival organizers see this milestone year as a reminder that queer joy and visibility require year-round commitment. This year’s festival is Oct. 4-5 in the North Village Arts District and the streets surrounding Rose Music Hall. Check out modmopride. org for more information.

er couple give out free hugs at a pride celebration in Philadelphia. Since 2018, the Smiths have spent every day of the festival, rain or shine, offering hugs and high-fives to those in need. Art Smith calls it “the best gig in town.”

While Columbia is the home base for PrideFest, it draws LGBTQ+ people from across mid-Missouri. Davis says the festival goes to great lengths to reach rural Missourians to offer them community and acceptance they may not have in their own homes.

The pride parade has become an important part of the festival. Past particiapants include this youth queen (above) in 2023. In 2018, volunteers worked with RuPaul’s Drag Race Star Morgan McMicheals (below).

According to a Trevor Project survey, only 28% of LGBTQ+ youth and 25% of transgender and nonbinary youth in Missouri felt “high support” from their family in 2024. The national survey found that young LGBTQ+ people with access to affirming spaces had lower rates of suicidality compared to youth without affirming spaces. Smith says he and his wife aim to offer a safe space for those without close relationships to their family. “Some people want high-fives or fist bumps, and that’s cool too, but sometimes it’s a long, deep hug and the tears start to flow,” he says. “I’ve twice now had people tell me while I’m hugging them that they’d never gotten a dad hug. I mean, it breaks your heart to hear that.”

DeVore says the mood around this year’s PrideFest has been dampened compared to previous years. Amid a wave of anti-LGBTQ+ legislation, DeVore says the festival’s board members have felt a lack of joy about the state of queer acceptance. However, he says Columbia’s queer community remains a steady beacon of light.

Each month, Vox curates a list of can’t-miss shops, eats, reads and experiences. We find the new, trending or underrated to help you enjoy the best our city has to offer.

local author and Jane Austen aficionado Jane Austen: The Original on its release date, Sept. 30.

The Austen Connection in 2020, a blog and podcast discussing Jane Austen’s novels and how they have influenced our culture. The book explores the moments that led to Austen’s six published novels, Pride and Prejudice and Emma. Saidi, a professor at the Missouri School of Journalism and producer at KBIA, uses her journalistic perspective to delve into the links between old novels and pop culture. “In many ways, when you’re a public radio journalist, you’re a culture journalist,” Saidi says. “You’re paying attention to the forces that are impacting our culture, and Jane Austen is a huge force in our culture.” Book launch event 5:30 p.m. Sept. 30, Skylark Bookshop

JAM OUT to Boldy James, Natural Information Society and Swamp Dogg at the Extended Play II festi val presented by the artist-run record label Dismal Niche Arts. The festival brings unconventional music performances to Columbia, showcasing artists who might not otherwise make it to the city. This year’s lineup ranges from Boldy James’ sharp storytelling to Swamp Dogg’s soulful R&B and the hypnotic instrumentals of Natural Information Society — an eclectic blend you won’t want to miss. Boldy James: 7 p.m. Oct. 17, Rose Music Hall; Natural Information Society: 7 p.m. Oct. 18, Rogers Whitmore Recital Hall; Swamp Dogg: 6 p.m. Oct. 19, Cafe Berlin, $55+, dismalniche.com/extended-play

VIBE to “Jackie Blue” at the Missouri Theatre with The Ozark Mountain Daredevils. After touring continually since the formation of the band in the early 1970s, The Ozark Mountain Daredevils are stopping in Columbia as part of the group’s farewell tour. You can expect emotional and captivating country rock performances in celebration of the past 50 years of creating and performing music. Say one final goodbye to Cosmic Corn Cob and His Amazing Ozark Mountain Daredevils. 7 p.m. Oct. 4, Missouri Theatre, $77-$95, theozarkmountaindaredevils.com/tour

WALTZ back in time to 19th century England at the third and final Bridgerton Ball hosted by Como 411. Inspired by the Netflix series, locals dress up in corset gowns and vintage suits to be this season’s diamond. Tickets start at $89 with VIP packages priced higher. There will be food from Eclipse Catering, live Bridgerton-themed music and dance performances. The evening will end with a dance party hosted by DJ Jonny Fuzion, marking the final year of the Bridgerton Ball before a new theme takes its place. 7-11 p.m. Oct. 10, The Atrium, $89-$800, como411.com/bridgertonball

STOMP on grapes at this year’s Crush Festival in celebration of 40 years of the Les Bourgeois A-Frame Winegarden. Guests can try their hand at grape stomping, enjoy live music from Ty Toomsen & The Twang City Smokers and take part in activities like pumpkin painting and crafts. Whether or not you’re a wine drinker, the festival is a free chance to welcome autumn as cooler days arrive. 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. Sept. 28, Les Bourgeois A-Frame, missouriwine.com/wine-dine/thea-frame

Adam Saunders helped plant the seeds to grow Columbia’s relationship with gardening.

BY KATIE GRAWITCH

As a child, Adam Saunders passed the long, sticky summer days in his neighbor’s garden that stretched across the block. His father and the neighbor worked to harvest plump sweet peas and ripe-to-bursting cherry tomatoes. There, elbow-deep in soil, he first learned that a community reaps what it sows.

When Saunders co-founded the Columbia Center for Urban Agriculture in 2009, his mission was to use gardening to unite the community through hard work and accessible food. Sixteen years later, CCUA manages three community gardens, produces food for nonprofit programs and offers education and apprenticeship opportunities. If you’ve been to the Columbia Farmers Market, then you’re familiar with CCUA’s 10-acre Columbia’s Agriculture Park, which sprawls throughout the Clary-Shy Community Park. The park houses not only the farmers market, but it also hosts CCUA’s production fields, school house, food forest and greenhouses.

Corrina Smith is the executive director of the Columbia Farmers Market and has worked with CCUA for 11 years. “In those initial years, I don’t know if we could have dreamed that we would be where we are today,” Smith says.

The newest addition is a welcome center in partnership with Columbia Parks and Recreation that should open in late spring or early summer 2026. It will include a rentable commercial kitchen, shared tools and event space.

Vox sat down with Saunders to learn about the Community Welcome Center and CCUA’s efforts to improve community food systems.

What will the Community Welcome Center provide that’s different?

This new multipurpose space will help CCUA and the Columbia Farmers Market to level up programming to the community with a big commercial

and teaching kitchen, a resource center, office space and activity hall. These new spaces complement the existing campus well and open some exciting doors for new programming and service outreach.

What has informed your work with kids at the CCUA?

In our earliest days, (CCUA) wanted to create this empty lot downtown into a garden-and-share because the other co-founders and I all had vegetable gar dens growing up, so we had this shared experience. That’s true for a lot of our staff. They had educators in their life, and that’s not as common as you would think. There’s a lot of people who have (the) basic literacy of a garden, that “plants come from seeds and farmers and gardeners are the people who tend them, and I could do that if I wanted to.” That’s a generational change.

Why do you think food systems are so important?

I like to eat. I eat every day. It’s really that simple. I think that’s true for ev erybody. Peo ple feel better when they eat high-quality food and it tastes good. I think that feed back loop is so ob vious and so quick when we eat good food, or when we don’t eat enough food, or when we eat unhealthy food. There’s a lot of people in our society — in Columbia and around the world — who are in crisis for various rea sons: homelessness, poverty, addiction or trauma. They need to eat food every day, too, and they maybe don’t get access

The Columbia Center for Urban Agriculture runs three community gardens. Veterans Urban Farm provides opportunities for veterans. Kilgore’s Community Garden helps feed kids at a nearby day care. Columbia’s Agriculture Park houses the farmers market and other resources.

Adam Saunders is the co-founder of CCUA.

to healthy food. When people struggle with food security at an individual level, with consistent access to healthy food, I think it’s our duty to help them.

What’s something people learn once they start gardening?

You talk to a gardener, they’re going to want to talk about their garden. Whether they’re bank presidents or refugees or people in public housing or everybody

by

Jordon Kays shares his own ludicrous world, one film at a time.

BY JASMINE JACKSON

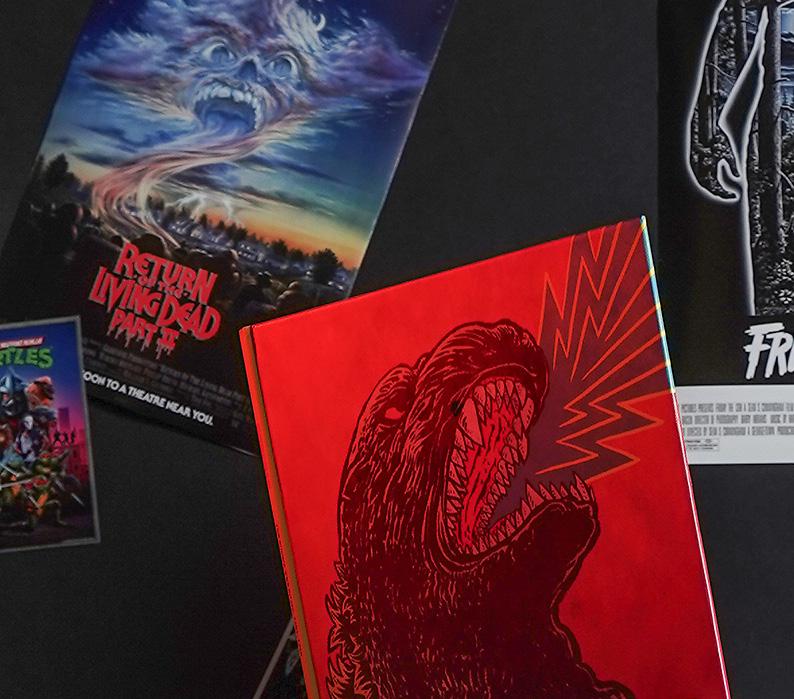

Jordon Kays is no ordinary cinephile. It started with Friday nights at the video rental store in Versailles, Missouri. As a child, Kays would peruse the shelves, going off box art, blurbs and recommendations to find his next watch. He’d rent one, then come back for another. And another. Watch. Rent. Repeat. “I would just rent these random movies that I thought looked cool or looked interesting,” he says. Ghostbusters and horror became immediate favorites.

Cue the collecting

Renting turned into buying, and now, Kays doesn’t need to visit his hometown video store anymore — he practically lives in one. About 600 DVDs line three shelves in Kays’ living room, each shelf with its own purpose. One holds action, comedy and TV shows. Another has horror. And then there are what he jokingly calls “staff picks,” which are movies Kays recommends for friends, such as Landis Merrill. “I have my own movie Rolodex,” Merrill says. “I’ll hand him a couple of words, and then I get to watch something that directly matches what I wanted.”

The collection is more than a builtin movie theater for Kays and his friends. It’s a way to preserve physical media. Many movies have disappeared from streaming services due to licensing, leaving only those with physical copies available to watch. “I want to have these movies, especially when it comes to the

more obscure and weirder stuff that may not come up as often,” Kays says. Kays knows he is due for a fourth shelf soon.

The movies are getting more use since he and Merrill launched Tragically Ludicrous in October last year, a monthly double-feature show that began at the Witches and Wizards Arcade.

Putting on the show

Ten years ago, Kays took his love for horror films to Instagram and Facebook, beginning what he called “Shocktober.” He suggested one horror movie a day for the month of October. “I wanted to do something special for the 10th anniversary,” Kays says. “I really wanted to do a movie show.”

Tragically Ludicrous: Shocktober Live! debuted on Halloween night last year, featuring showings of Nightmare on Elm Street and Dead Alive, alongside a costume contest, trivia and popcorn. The name Tragically Ludicrous is a Simpsons reference — guest star John Waters’ character uses the phrase to explain the word “camp” to Homer. Kays says the joke is one of his favorites and the perfect description for the “campy” movies Tragically Ludicrous shows.

The shows have continued on a regular basis on Friday nights. Kays cohosts the event with friend Ted Zeiter, and between shows, they engage the audience with skits, games and giveaways. “I took the idea of going to the video store, hanging out with friends and bringing over movies,” Kays says. “We’d chill and watch the movies, making fun and talking about it, and I wanted to bring that into an audience.”

Movies always align with the night’s theme, but the overall goal, says Merrill, is weird but not too weird — for now at least. “We don’t (want) to scare people off, but we’re trying to get into the stuff you may not have seen or that you saw when you were a kid,” she says.

In the 10 months since Tragically Ludicrous shows have been held at the arcade, “the weird and the wacky” had left an impression, says Rebekah Mauschbaugh, the former assistant manager of operations and media at The Arcade

Kays puts his movie collection to use during Tragically Ludicrous showings (above right). His memorabilia includes films like Godzilla, Return of the Living Dead 2 and Friday the 13th (above left).

Kays has a collection of at least 600 DVDs. He sees it as a way to preserve physical media.

District. “They’re creating their own kind of niche community,” Mauschbaugh says.

This October, Tragically Ludicrous will continue to expand its community by bringing a show to Hexagon Alley. The show’s films could easily be connected with themed events at Hexagon Alley, writes co-founder Colleen Rieman in an email to Vox. She says she “loves a good collaboration of passion projects.”

For Kays, it all comes back to the movies themselves. “I get to see something I don’t get to see on a normal day, whether it’s fantastical or just a slice of life movie, and I get to pick what those things are.”

Tragically Ludicrous and Kays, along with Zeiter, will return in October at both Hexagon Alley and Witches and Wizards Arcade. At Hexagon Alley, the October film features include To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar and Hedwig and the Angry Inch at 7 p.m. Oct. 3 — the same weekend as Mid-Missouri PrideFest. This year’s Shocktober Live! is set for 7 p.m. Oct. 31 hosted at Witches and Wizards Arcade with the movies Evil Dead 2 and Army of Darkness.

‘B’ there or ‘B’ square

Here are the can’t-miss eats and beats for Biscuits, Beats & Brews.

BY AUGUSTUS HENDERSON

If you’ve been meaning to make it to Biscuits, Beats & Brews, here’s one more reason to add the music festival to your calendar this year. “This is the last opportunity to experience Cooper’s Landing as it was before the announced remodel,” says Colin LaVaute, the festival’s director since it began as Rocheport Oktoberfest in 2016. In spring, the venue’s team announced plans to build a new main building with indoor seating, bathrooms and a renovated parking lot. Demolition and construction are scheduled to begin immediately after the festival.

Since moving to the rustic venue along the Missouri River from Rocheport last year, the free music festival has offered its namesake food, tunes and beer, as well as the Betsy Farris Memorial Run, which honors the late director of the now-defunct Roots N Blues Festival.

Taking place Oct. 3-5, the Biscuits, Beats & Brews music festival features a diverse range of musicians and local eats, giving attendees a chance to refuel while enjoying the picturesque atmosphere at Cooper’s Landing. Here’s everything to know about the festival from B to, well, B.

Music is at the heart of the festival, and this year, the lineup features musical acts from across the Midwest and span a variety of genres and ages. “What we’ve tried to do is create and curate a festival that has the best of what the Midwest has to offer,” LaVaute says.

A prominent returning act at this year’s festival is The Spooklights, a

Photography by Braiden Wade/Archive

collaboration between Pat Kay of The Kay Brothers and Ben Miller of the Ben Miller Band. With roots in southern and central Missouri, The Spooklights play electronic music alongside traditional “Ozark stomp grass,” providing a unique fusion of sound. The eclectic band gets its name from the sightings of paranormal lights near Route 66 in Joplin.

Also playing at this year’s fest are The Burney Sisters, Columbia-raised folk and Americana multi-instrumentalists who have since relocated to Alabama. Drawing inspiration from artists like The Avett Brothers and HAIM, teenage Emma and Bella Burney incorporate themes of self-discovery and resilience into their music for a refreshing take on Americana.

Decadent Nation kicks off the lineup on Friday night with The Spooklights. Olyssa starts Saturday’s music lineup, followed by The Diddy Wah Daddies, The Onions, Adventure Hat, The Stoplight Flyers, Meredith Shaw and The Borrowed Band, Travis Feutz & The Stardust Cowboys, Austin Kolb Band and Noah Earle. LaVa Girls are slated to start Sunday with Violet and the Undercurrents and The Burney Sisters rounding out the bill.

The biscuits and brews

You won’t go hungry at this festival. Biscuits, Beats & Brews partners with

This year’s music lineup ranges from electronic-bluegrass fusion to more folksy guitar acts, like the music Gabriel Scott Meyer brought to the fest in 2023 (above).

Ozark Mountain Biscuit Co. to provide attendees with comfort food. The festival doesn’t just serve biscuit-based eats, though. Roux Pop-Ups will bring Cajun and Creole staples, Endwell Taverna will provide pizza and Italian food and Voodoo Sno will serve thinly shaved New Orleans-style sno-balls.

Did you know that the festival was called Rocheport Oktoberfest and Rocheport Doughnut Fest before becoming Biscuits, Beats & Brews in 2022? Here’s when and where you can find this year’s fest: 5-9 p.m. Oct. 3, noon to 9 p.m. Oct. 4 and noon to 5 p.m. Oct. 5 at Cooper’s Landing,11505 Smith Hatchery Road. Find more info at biscuitsbeatsbrews. com.

Cooper’s Landing will run a full bar with a variety of beers, sodas, cocktails and mixed drinks along with craft beers from local breweries.

The buses and bikes

If you’ve been to Cooper’s Landing before, you know that parking is limited — and dusty. The venue will provide paid parking during the event for $5. The most convenient option for attendees is to use the provided shuttle parking or bike to the festival, says Cooper’s Landing owner Richard King. “We highly encourage people to bike,” he says. To bike, attendees should take the MKT Nature and Fitness Trail to Hindman Junction, then head south on the Katy Trail, which leads right to Cooper’s Landing. The ride is roughly 15 miles from Columbia and provides a scenic view of mid-Missouri’s rolling hills and fall colors.

No matter how you get there, Biscuits, Beats & Brews will serve up comfort food, good tunes and a little slice of home for Columbians.

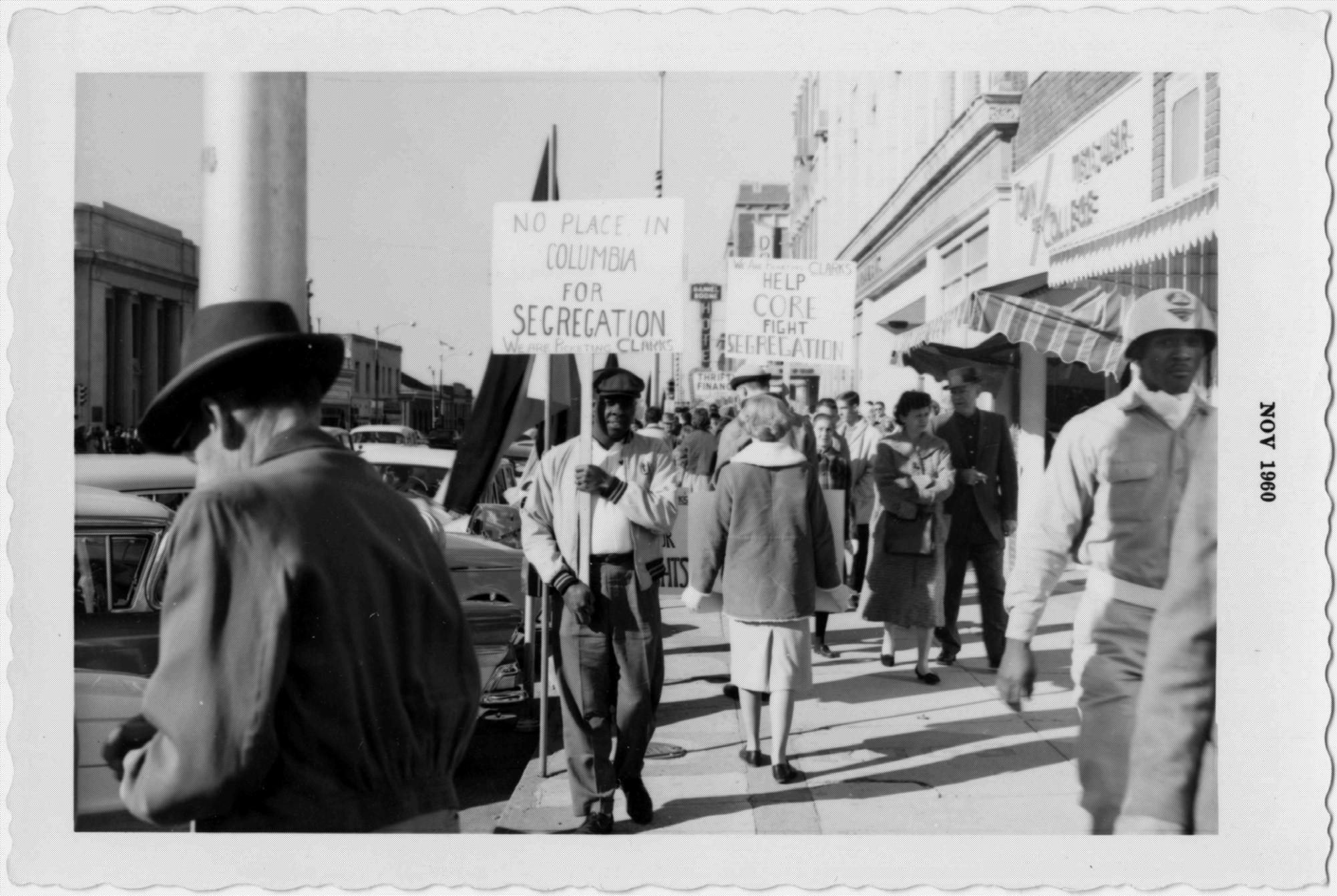

The Congress of Racial Equality utilized nonviolent protests to stand up to racism, violence and segregation in Columbia during the late 1950s and early 1960s. The methodical, determined work of these — mostly student — activists led to dozens of downtown businesses opening to Black customers.

Written

by Mercy Austin

Edited by Ashlynn Couch

Design and illustrations by Valerie Tiscareno

It was a cold, cloudy Saturday when three University of Missouri students and two professors were arrested by Columbia police and charged with trespassing. Their crime?

Conducting a peaceful sit-in at Clark’s Soda Luncheonette, a segregated restaurant on Broadway located where Central Bank is today.

This was Dec. 10, 1960, the same year sit-ins in Greensboro, North Carolina, launched a national movement of nonviolent protests demanding that Black people be given the right to public access. Those arrested at Clark’s were members of the Congress of Racial Equality, or CORE, a national, multiracial civil rights organization with a mostly student-led chapter in Columbia. At the time, over 50 people attended CORE meetings, and the whole city was talking about it.

The group’s activism is a key, but often forgotten chapter in Mizzou’s long history of student protest. CORE was instrumental in ending segregation in downtown Columbia businesses. It also provided impetus for the later creation of the Legion of Black Collegians, the first and still the only Black student government in the country.

Soda counter sit-in

CORE members ran “tests” at segregated establishments, often sending interracial groups in waves to evaluate businesses’ willingness to serve Black customers. Their goal was to use nonviolent methods to convince establishments to open to all.

Fred Clark, the owner of Clark’s Soda Luncheonette, was a leading voice in opposition against CORE. He was known across town as a “rabid segregationalist,” writes scholar Marc Brady Drye, and Clark refused to talk with the group’s members about integration. So did its competitor, Ernie’s Diner on Walnut Street.

Chapter records, now held at the State Historical Society of Missouri, chronicle the moment when the members arrived at the restaurant and asked to be seated.

“We are not going to serve you,” Clark said. John Schopp, a CORE leader and MU astronomy professor replied, “We would like to have service.”

“You can stay or not, but we’re not going to serve you,” Clark said, then left. When he returned, he was accompanied by the police.

The five were taken into custody. A defense fund to help them raised $540.50, which would be the equivalent of $5,800 today. Hearings over the next two months drew packed courtrooms and were consistently front-page stories in the Columbia Missourian and the Columbia Daily Tribune In February 1961, the case was dismissed, and the court determined that peaceful sit-ins did not constitute criminal trespassing under Missouri law.

Clark’s remained closed to Black people, but CORE was now at the forefront of civil rights action in Columbia.

The arrests at the sit-in wouldn’t be the last time CORE members put their livelihoods at risk. As a result of their nonviolent protests, they were harassed by community members and Mizzou officials. The university consistently targeted and shot down efforts CORE made to end segregation.

But that couldn’t stop the movement underway. Waves of collective outrage were sweeping across Columbia. And it was known that the members of CORE would face jail before they accepted the status quo.

A fractured city

Columbia’s chapter of CORE was born out of a city split through its heart.

In the mid-20th century, the area south of Broadway, which housed the university and the center of student life, typically allowed only white clientele. On the north side of the street were the city’s predominantly Black businesses and neighborhoods.

It was a rift with destructive, often violent, implications. Among those particularly isolated were Black students. Most apartments around campus did not lease to them, and many restaurants refused them service. Though MU had nominally desegregated, barriers to housing, employment and public accommodations kept Black enrollment limited.

A few people who lived through that time were

Mizzou admits its first Black student when Lloyd Gaines sues the school for discrimination and the Supreme Court rules in his favor. Gaines disappears three months after the ruling and is never heard from again.

1950

The first Black students arrive on campus after more challenge exclusionary admittance policies. Lucille Bluford, a Black woman, paved the way in 1941, winning a legal battle to be accepted into the journalism program. She never attends the school because Mizzou pauses the program, citing World War II.

CORE members successfully repeal discriminatory policies at Mizzou and in downtown Columbia.

Barbara Papish sets a precedent for First Amendment rights, filing a lawsuit against Mizzou after she is expelled for distributing an explicit political cartoon criticizing the Vietnam War. The Supreme Court rules in her favor.

R E

interviewed in 1993 for the book The African American Experience at the University of Missouri by the Black Alumni Association. The cassette tapes from these interviews are preserved in the university’s archives.

One such tape belonged to Council Smith, a sociology student from Charleston, South Carolina, who was at MU from 1957 to 1962. Through those years, he said he was one of less than a dozen Black students on campus. When Smith first arrived, all the dormitories were full. The school gave him a list of off-campus housing options. “I spent the better part of the day checking the houses around the university, and none of them would rent to me,” he said. “I was able to find housing eventually across town in the Black neighborhood.”

Violence was common for Black students on the south side of town. “If you were south of Broadway, after a while, you may get physically abused,” said George Brooks, who graduated with a master’s degree in education in 1958. He said the “headquarters” of segregation was Booches Restaurant and Pool Hall. “We just stayed away from it. You stayed clear because you knew what was likely to happen if you went in,” he said.

But in Columbia and across the country, activism and community outrage were rising to a boiling point. The end of World War II saw an explosion of veteran enrollment in universities across the country, many of whom became leading voices for social change. The American Veterans Committee and the local NAACP were among the most active in the desegregation fight.

The national Congress of Racial Equality shared those organizations’ focus on nonviolent desegregation, but was unique in its membership of both Black and white activists. The first CORE chapter in Columbia was relatively small and lasted from 1949 to 1954, focusing on desegregating movie theaters, drug stores and lunch counters. It disbanded after the Brown v. Board of Education ruling, believing its work was done. But the city remained an unsafe space for Black students.

As a teenager in Kansas City, Gloria Logsdon organized protests demanding change of segregationist policies at several locations, including Macy’s and Fairyland Amusement Park. She continued to participate in sit-ins at restaurants in Columbia as part of the Congress of Racial Equality.

Gloria and John Logsdon met at Mizzou in 1961. This photo of them on a beach (far right) in Maryland was taken two years before they were married.

In spring 1959, the organization was reborn after a mixed-race group of students boycotted the Tiger Inn, a campus lunch stand across from the men’s dormitory that had a closed-door policy for Black people. That protest launched a series of negotiations with the restaurant, and chapter records show that the Tiger Inn opened to all a year and a half later because of “prolonged and patient negotiations.”

The group filed a request to become a registered campus organization that fall. Although it was approved by the Missouri Students Association, the MU administration denied its acceptance. The dean of students,

Jack Matthews, said the application would be accepted if they allowed only white students to participate. They refused. CORE was a multiracial organization.

Instead of dissolving, it reorganized in 1960 independent from the university and gained national CORE affiliation as one of 24 chapters across the country. Student leaders swung into action and took the helm. The most prominent among them was Gloria Newton.

‘I did what I’d been doing in Kansas City’ By the time Newton became a CORE member

in 1961, she was already a Missouri celebrity.

She was a student from Kansas City who attended community college before moving to Columbia. She got involved in civil rights as a high school senior when a department store turned away one of her teachers. Every Saturday, Newton had picketed outside the store with the NAACP, often for six to eight hours at a time. The department stores eventually conceded and opened to Black customers. Subsequently, the NAACP opened negotiations about hiring Black people, which happened shortly after.

“For the first time in my life, I felt that I could make a difference,” Newton said in a 2014 oral history interview, which is housed at the Smithsonian Museum of African American History.

Newton led a series of successful protests at movie theaters, department stores and restaurants. Her most famous protest was at Fairyland Amusement Park, an attraction in Kansas City that only opened to Black people one day a year. She mobilized the local NAACP and CORE chapters to park cars blocking each of the park’s eight entrances and refused to move until they opened the park to everyone. She and the other demonstrators were arrested and spent the night in jail.

It would be years before Fairyland opened to Black customers, but the sit-in drew national attention. Newton was labeled the “Greatest Sit-In-er of them all” on national television. She was selected as an NAACP youth representative to travel to Washington, D.C., and attended a meeting with Martin Luther King Jr. and President John F. Kennedy. She was 19 years old.

By the time Newton enrolled in MU’s sociology program, she was no stranger to discrimination. Her white roommate refused to live with her, so Newton was evicted and had to sleep on the dorm’s couch for weeks before MU found another accommodation.

According to a report from CORE leader John Logsdon, many Black students were removed from dorms with white roommates and forced

to live in older wooden barracks.

But Newton had a vision that through CORE, the desegregation she’d seen back home could happen in Columbia, too. “I did what I’d been doing in Kansas City,” she told me when we talked, 64 years later. “I went to restaurants that didn’t particularly like having Black people there, and I kept going to those places.” She directed numerous CORE actions against local restaurants and campus dining halls, including leading many of the protests at Clark’s and Ernie’s.

Her activism drew the attention of John Logsdon, a white student from Mehlville who served as the chairman of CORE from 1962 to 1963. “I met Gloria at a CORE meeting,” Logsdon recounted in a 2013 article for the Mizzou Alumni Association’s magazine. “She came in as kind of a celebrity because of her work in Kansas City. I studied at the library a lot, and she had a job there at the circulation desk. I started talking to her there. We were working a lot together at CORE — and if you’re not careful, it becomes a full-time job — so we got to know each other well.”

In their junior year of college, they began dating. At that time, interracial marriage was illegal in Missouri. Newton says when she and

Students win a seven-year legal battle to form a Gay Liberation group on campus SCOTUS upholds a lower court’s decision that the students have a constitutional right to assemble.

The Board of Curators votes to divest its holdings in companies that support apartheid in South Africa This follows protests and students erecting wooden shanties on the quad for a year. The university responds by removing shanties and arresting students, but students continued to rebuild.

UM System President Tim Wolfe and MU Chancellor R. Bowen Loftin resign under pressure from Concerned Student 1950, a student organization that formed in response to a string of racist incidents on Mizzou’s campus.

Logsdon decided to get married, they were approached by the American Civil Liberties Union and asked to be a test case — to sue the state for the unconstitutionality of the marriage ban. They declined, wanting a wedding free of controversy. They went to Washington, D.C., and were married there.

Two years later, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled the ban unconstitutional in Loving v. Virginia, which legalized interracial marriage across the country. The Logsdons were married for 55 years before John died in 2022.

Today, Gloria Logsdon lives with her daughter, Elizabeth Bacon, in Fairfax, Virginia. She and her husband attended King’s “I Have a Dream” speech in D.C. and continued to stay involved in the Civil Rights movement. She worked for New York State for 30 years and spent eight years as the head of the children’s mental health system. She is now living with Alzheimer’s.

I talked to Logsdon and her daughter on FaceTime. While she doesn’t remember a lot, she told me one thing over and over. For all the hardship, violence and discrimination she faced — most people were kind.

From 1961 to 1962, the number of restaurants south of Broadway that served Black people increased from six to 29. Columbia was seeing changes, with CORE leading the charge.

Yet every win and every bit of publicity also drove CORE members further into the mires of controversy and violence. MU administrators attempted to act against John Logsdon for asking teachers to donate to the defense fund. He received hate mail. The house he rented in 1963 was set on fire.

After Schopp’s arrest during the 1960 sitin, he was denied tenure by MU and given a terminal contract with no explanation from the university. The decision prompted outrage across the Physics Department and the wider Columbia community. An editorial by The Maneater published at the time wrote that “Schopp’s decision to take an active part in the

Protesting on Broadway in 1960 (right), local members of the Congress of Racial Equality picketed against the segregation policies of Clark’s Soda Luncheonette. The establishment did not open to Black customers until a city ordinance in 1964 forced it to.

From 1961 to 1962, the number of restaurants south of Broadway that served Black people increased from six to 29. Ernie’s (at left) did not allow Black patrons until 1964. Sit-ins by CORE were instrumental in these changes.

civil rights battle has resulted in publicity which the University undoubtedly would rather not have received.”

Yet the fight raged on, and in June 1964, Columbia passed its public accommodations law. This forced the remaining restaurants, including Clark’s and Ernie’s, to finally offer service to all. It had been a long and brutal fight, but by that time, CORE had already been successful in many of its goals. Around twothirds of the restaurants in Columbia served all patrons, regardless of race. They had won, but not without years of struggle.

After the passing of the public accommodations act, CORE dwindled to a smaller group, whose focus shifted to housing, employment and school integration. Through protests and negotiations, CORE succeeded in pressuring the university to end its segregatory

housing policies. Race was deleted as a category in the dormitory applications, and Black students could finally room with white students without fear of eviction or reassignment.

In 1969, a new civil rights organization formed on campus, this time specifically geared toward Black students and reflecting the national impetus of the Black Power movement. The Legion of Black Collegians carried forward what CORE activists had started.

Columbia establishments are open to all today in large part because of the work of CORE activists. “Columbia CORE’s use of nonviolent action was the most important factor in ending segregation in the public accommodations of Columbia,” writes Drye, whose master’s thesis focused on the organization.

Clark’s has since closed, but Ernie’s is still open in the same place. Gloria Logsdon and her daughter, Elizabeth Bacon, dropped into the restaurant on a visit 10 years ago. Logsdon had spent years of her life picketing outside of the building, and now they let her in without any issue. “It was kind of a full circle moment, going back there,” Bacon says.

CORE’s legacy equates to more than just a memory of a bygone time. It is a battle that has not ended and a movement that is not new. Threading through MU’s history is a series of run-ins between progressive students and conservative administrators, often centering controversy over the right to organize, protest and speak out.

This is just one of the chapters in a continuing story of community activism, driving social change in Columbia.

Story Tyler White

Photography Lily Mantel

Editing Charlie Warner

Design and illustrations Rachel Goodbee

Cuts to federal funding seem indicative of a wider devaluing of the importance of arts and culture. Here in Columbia, the community has responded to such threats with resilience and unity.

t the creative hub affectionately known as Hittsville, Ragtag Cinema is showing the latest films and providing a home for classics and documentaries. On Ninth Street, the “Interpretations VII” exhibition of visual and literary works is on display at the Columbia Art League. At Rogers Whitmore Recital Hall, the group Natural Information Society’s music will soon kick off the “We Always Swing” Jazz Series’ 31st season. And the list of cultural activities could go on and on.

Everything seems to be business as usual. But it’s not. As has been widely reported, on May 2, the Jazz Series and Ragtag learned the organizations’ National Endowment for the Arts grants had been canceled. It was a sucker punch.

I’ve spent the last three months talking with leaders at local arts groups, and one thing is clear: Columbia’s art community is resilient and not going anywhere.

There is city-wide support for the arts, from both the people who curate, promote and execute community-engaging events and those who attend these endeavors. This relationship has helped — and will continue to help — the arts thrive despite new uncertainty around federal funding. Person after person I spoke to mentioned the importance of this relationship to the strength of the local arts community.

Indeed, it has been amazing to see how Columbians have responded to the funding cuts. They’ve opened their wallets to donate to arts groups. They’ve attended events and exhibits. They’ve voiced their support.

For the Jazz Series, its $25,000 NEA grant was meant to fund its 30-year anniversary celebration and concert, which was held April 30 — two days before the money was rescinded. The Jazz Series appealed the decision in an attempt to hold onto some of the funding, but in August, the NEA denied that appeal. “You feel like you were misled,” says Jon Poses, executive director and art director of the Jazz Series. “The project was freaking over, and then we found we’re not getting the money, so there’s not a whole lot you can do.”

To make up for the lost funds, the group held a month-long campaign in June to close the budgetary gap. That raised $14,515. “I have been astounded at the com-

munity’s generosity, I mean, truly astounded,” Poses says. Ragtag Film Society had a similar experience with NEA. For the film society, which is the nonprofit behind Ragtag Cinema and True/False Film Fest, the $30,000 grant was part of its annual budget, and it has received similar grants for over a decade. Unlike the Jazz Series, Ragtag received its 2025 grant but was informed it doesn’t fit the types of projects NEA will fund in the future.

Executive Director Andrea Luque Káram says losing future funding is an intimidating thought. But again, the community stepped up to help. Ragtag’s annual membership numbers have reached an all-time high. “That re-energizes me and my staff,” Káram says. “We’re moving toward the right direction. People want us to be here; need us here.”

Hundreds of arts organizations across the country lost NEA grants in May. Although the NEA hasn’t released numbers, a nationwide community-sourced spreadsheet of lost funds estimates that $27 million in promised funding was revoked.

Emily Edwards, who was the marketing and communications director of Ragtag until September, says these cuts bring uncertainty to future budgets. It raises questions about what programs should be prioritized and what must be cut.

The annual grants helped the organization operate on a day-to-day basis. This funding was dispersed wherever Ragtag needed additional funding, whether it was for the True/False Film Fest or innovating new ideas within the cinema. With this additional cash flow potentially gone, it places a burden on figuring out the next steps for the coming years. In Ragtag’s case, it’s not known if it could receive NEA funding in the future — all that is certain is that it won’t this year.

The challenge of budgeting amid uncertainty is echoed by many organizations throughout the local arts community. Without these grants, even if the money was a small part of a budget, organizations now have to look elsewhere for support and funding. And these impacts don’t just affect the groups that directly receive NEA money.

Trent Rash, The Missouri Symphony’s executive di-

We’re moving toward the right direction. People want us to be here; need us here.

rector, says organizations could see a trickle-down effect. The symphony gets a portion of its funding from the Missouri Arts Council. If the state council loses NEA funding, that would affect the symphony.

The symphony uses arts council grants to connect with the community outside of concerts and series, Rash says. This includes events like Preludes at the Pubs, which foster appreciation for classical music in an interactive way. Cuts to the money that supports these things could mean the loss of community-focused events.

—Andrea Luque Karam, executive director, Ragtag Film Society

But it’s not just the arts. These cuts could find their way into places like the Daniel Boone Regional Library. While NEA grant losses don’t directly affect the library’s day-to-day operations, it might cut deep into other activities the library supports, says Robin Westphal, executive director of Daniel Boone Regional Library. These programs, such as The Creative Age, which is funded in part through a Missouri State Library grant, provide more cultural opportunities for people in Columbia.

“We’re losing the opportunity that we have utilized in the past to pilot some projects, or to do some really innovative things,” Westphal says. “It’s going to be hard for us to justify doing that when we just have enough money to do the things we’re currently doing.”

Though only two local organizations lost NEA funding this year, the cuts could dampen the likelihood that other groups will apply for future grants to support creative innovation.

The impact goes beyond money. The cumulative effect of cuts — along with discussions of further slashing the NEA budget — portrays the arts and cultural experiences as “less than.”

Westphal says the actions at the federal level seem to indicate that art and culture aren’t a priority. That’s why it’s so important that community members show how vital art is to this community, she says.

Kelsey Hammond, executive director of the Columbia Art League, says arts-centric events that foster collaboration and exposure to the arts benefit the entire community. Art helps humans understand the world just as philosophy or science do, she says. Without art, people lose the opportunity to express themselves and share their understanding of the world with others. “Those are the reasons why art has to exist,” she says.

Art also helps people venture beyond their everyday lives, says Enola-Riann White, capital campaign chair of The Missouri Symphony. Art creates a “third place” away from your typical routine. “You can go and just be — and be someone different, learn something new about a different culture or experience something that you’ve never seen before,” White says.

One thing helping through this uncertainty is that the arts community here is both collaborative and supportive.

When art organizations experience a disruption in cash flow, support from community members becomes even more vital. This support can take many forms, including spending time, donating money or being vocal about why these groups matter to you. Here are some ways you can help.

• Peruse the gallery at Columbia Art League, 207 S. Ninth St. Learn about the current exhibit at columbiaartleague.org.

• Visit the “We Always Swing” Jazz Series’ jazz library, 21 N. Tenth St. Find out more at wealwaysswing.org.

• See a film at Ragtag Cinema, 10 Hitt St. Find showings at ragtagcinema.org.

• Spend time at the Daniel Boone Regional Library, 100 W. Broadway. Hours are at dbrl. org.

• Take in a performance by The Missouri Symphony. Check out its schedule at themosy.org.

• Become a Ragtag Film Society member. Learn more at ragtagcinema.org/cinema/ membership.

• Make an annual or recurring contribution to the Jazz Series’ Top It Off donor campaign for the 2025-26 season, wealwaysswing.org/support.

• Attend The Missouri Symphony’s Sips for the Symphony cocktail party, 7-9 p.m. Oct. 17, 106 Orr St.

• Tell your friends and family about all the events taking place in Columbia and invite them to join you; the more people know, the more people support.

From dance companies to art galleries and music venues, White says all the organizations work together to create this vibrant and culturally fluent community. “You have all of these different organizations that you would think are competing against each other, but they’re actually playing really, really well in the sandbox together, and they want to help support each other,” White says.

This arts-focused community is part of what makes Columbia so unique, says Kerry Townsend, incoming executive director of Unbound Book Festival. Art in the Park, True/False, Unbound, Firefly Music Festival, One Read and First Fridays are just some of the city’s abundant cultural opportunities.

Such events invite collaboration and community among artists — whether that’s creating connections around documentary films at True/False or bringing artists together to share their expressions and emotions through works at Art in the Park.

Townsend says the best ways to show support right now are through attendance and donations. By attending events, you can see where funding goes and how im-

portant it is. Even a little bit of money goes a long way for these organizations, she says.

It’s also vital to share stories of how the arts and culture have affected you. The arts leaders I talked to for this story emphasized the importance of the community’s voice. More than ever, people need to be vocal about the arts’ role in their lives and how losing them would negatively affect their communities, Edwards says. “Access to those is what makes a city vibrant and makes a city worth prioritizing living in,” Edwards says.

Fundraising and stretching sparse budgets already are part of what most arts organizations do on a regular basis. Poses says he is grateful for how much the community continues to pitch in. “I never take it for granted,” Poses says. “The person that gives $10 gets the same thank you as the person that gives $5,000. You can’t do one without the other.”

Though the future remains to be seen, what is certain is the need for support in the face of funding challenges. And at Ragtag Cinema, Rogers Whitmore Recital Hall, the Columbia Art League and beyond, Columbians must continue doing everything they can to keep the arts community alive.

Art helps humans understand the world just as philosophy or science do.

—Kelsey Hammond, executive director, Columbia Art League

These once-discarded grill scraps are now a sought-after barbecue staple.

BY KIANA FERNANDES

I’m going to let you in on a little secret: After living in this town for five years, I’d never eaten Columbia barbecue. I usually avoid barbecue joints. The reason? I’m from Kansas City, and I have some self-admitted snobbery toward what constitutes good barbecue.

My favorite dish to get back home is burnt ends, which are a staple of Kansas City-style barbecue. But driving two

Bud’s Classic BBQ serves traditional, fast-selling burnt ends (above) made from the corners of a whole brisket.

hours just for a dish that originated as barbecue scraps is ridiculous. “They were snacks for pit masters, or the little things that somebody would leave on the counter for customers to kind of munch on while they were waiting in line,” says Jonathan Bender, founder of Kansas City’s Museum of BBQ. “They were given away for free at one time.”

Bender says burnt ends hit the

national stage because of a 1972 article by Calvin Trillin in Playboy. The article described the scraps as “burned edges” that were first given away at Arthur Bryant’s, one of the most iconic barbecue restaurants in Kansas City. Demand for the dish skyrocketed. “Pit masters are really enterprising people, and so when people started asking for something, they were more

than happy to sell it,” Bender says. Burnt ends are traditionally made from the tapered corners of a whole brisket. The bite-size dish is identifiable by its smoky, crunchy char that gives way to moist and tender meat. However, demand for burnt ends often exceeds the supply that can be made in this traditional way, since the cut that makes burnt ends is tiny relative to the size of a full brisket.

To account for this, Bender says pit masters have found workarounds to get the same flavor and texture profile but are easier to produce in high quantities. Some pit masters will cube other parts of the brisket to make burnt endalikes, while others will use pork belly. “They’re still super tasty, but I think of them as sort of a less traditional — or more new interpretation of burnt ends,” Bender says.

After learning more about burnt ends — and starting to feel homesick — it was high time that I learned where to find some locally. Here is one Kansas City BBQ snob’s guide to Columbia’s barbecue joints that offer burnt ends:

Como Smoke & Fire has several options to meet any burnt end needs. Traditional brisket and pork belly are both offered in entree and sandwich form. The entree platter comes with your choice of two sides and a slice of toast, while the sandwich comes with one side. Three homemade sauces can be paired with the

burnt ends — Something Sweet, Little Heat and Liquid Gold.

I also have another secret for you: there’s a third burnt end sandwich option, but you’re not going to find it on the menu. For those in the know, co-owner and pit master Matt Hawkins says to order the Cosmo. While I could say what’s in the sandwich, I’d rather let you discover it yourself.

3804 Buttonwood Drive and 4600 Paris Road Burnt ends price: $19.99 entree, $14.99 sandwich Stop in: 11 a.m. to 8 p.m. Monday through Thursday, 11 a.m. to 9 p.m. Friday and Saturday and noon to 7 p.m. Sunday

Contact: 573-447-6785 (Buttonwood Drive) and 573-443-3473 (Paris Road); comosmoke andfire.com

Bud’s Classic BBQ

Bud’s Classic BBQ is another restaurant that has both traditional brisket and pork belly burnt ends. Be forewarned: the brisket sells out fast. Owner Jason Paetzold says this is because Bud’s Classic BBQ is committed to only serving “true” burnt ends. This means they are sliced off the whole brisket just as Trillin described in his article.

The pork belly burnt ends, meanwhile, are twice-smoked and glazed with a sauce that provides subtle heat to the dish. These come in a slightly larger cut than a typical burnt end.

Both the brisket and the pork come with your choice of one side and can be made into sandwiches upon request.

304 S. Ninth St. Burnt ends price: $19.99

Stop in: 11 a.m. to 8 p.m. Monday through Thursday, 11 a.m. to 10 p.m. Friday, 10 a.m. to 10 p.m. Saturday and 10 a.m. to 8 p.m. Sunday

Contact: 573-777-1177; budsclassic.top

Bandana’s Bar-B-Q

Bandana’s Bar-B-Q is a regional chain with more than 25 locations across five states. Although its website primarily advertises the restaurant’s slow smoked pork, beef, chicken and ribs, there are also brisket burnt ends offered. These ends are offered on their own or in sandwich form.

Since burnt ends are essentially brisket scraps, some pit masters substitute traditional burnt ends (above) with pork belly or other parts of the brisket.

Available with the burnt ends are five sauce options, each designed to mimic a different barbecue hub. These sauces are called St. Louis Sweet & Smoky, Chicago Sweet, Memphis Style, Southern Style Original and — for my fellow homesick Kansas Citians — KC Style, which is described as, “a sweet and tangy sauce with a tomato molasses base.”

Bandana’s Bar-B-Q burnt ends come with garlic bread and choice of two sides.

3405 Clark Lane

Burnt ends price: $16.49 lunch, $20.49 dinner

Stop in: 11 a.m. to 9 p.m. daily

Contact: 573-256-2229; bandanasbbq.com

“THEY WERE SNACKS FOR PIT MASTERS, OR THE LITTLE THINGS THAT SOMEBODY WOULD LEAVE ON THE COUNTER FOR CUSTOMERS.”

—Jonathan Bender, BBQ museum founder

by Lily Mantel

Magnolia’s opens a fresh chapter for the historic Niedermeyer Building.

BY EMMA ZAWACKI

Behind four newly planted southern magnolia trees and through doors with dragon handles, you’ll find the retro paradise that is Magnolia’s Whisky & Wine Bar.

Located on the first floor of the historic Niedermeyer Building at Tenth and Cherry streets, the bar is the latest chapter in the building’s resilient story. The Niedermeyer has taken many forms since it was built in 1837 — from a school for women in search of higher education to the funky apartment complex it is today. The building’s current owner, Nakhle Asmar, is a former math professor at the University of Missouri who bought the building in 2013 to save it from destruction.

Knock! Knock!

Magnolia’s opened in June and offers a variety of whiskey, wine, beer and cocktails, ranging from local Logboat

Brewery products to whiskey from Japan and Scotland.

Walking into the bar, you’ll hear the sounds of vinyl records brought in by patrons or ice clanking against a shaker cup as bar manager Riain Oceallachain crafts a Celery Saturn. It’s Magnolia’s take on a classic Saturn — a concoction of gin, lemon juice and passion fruit syrup with celery and cucumber. With 10 years of cocktail experience in St. Louis and Chicago, Oceallachain says he takes pride in his creations.

The bar’s owner, Linda Libert, has been a tenant in the Niedermeyer since 2011, when she moved to Columbia from Connecticut. The bar has been her labor of love for the past seven years. Every inch of Magnolia’s is steeped in character, from the thrifted cabinets Libert found in Fayette and St. Louis to the live-edge bar from Troy, Missouri. “I’m just at the point where you

Looking to join the concert of laughs that spill over from Magnolia’s Whisky & Wine Bar? It’s open 4-11 p.m. Wednesday through Saturday, located at 920 Cherry St. #101.

never thought what was in your head (would) make so many people happy,” Libert says.

Libert says she wanted to fill a void she saw in the Columbia bar scene and offer an upscale whiskey and wine experience.

The bar also opens up the Niedermeyer Building to new visitors. Throughout its history as an apartment complex, the building has attracted people from across the country to stay in its apartments or beckoned people to find a seat on the white wrap-around porch.

And it means the world to people like former resident manager Rita Reed. It’s her old apartment where the new bar is located.

Built in 1837, the exterior of the Niedermeyer Building hasn’t changed much, as shown in these photos from 1907 (below left) and 2025 (below right).

Reed ruled the roost at the apartment complex from 1974 to 1981. During those seven years, she says she has the Niedermeyer to thank for a lot of things: her knowledge of renovation, how to cook pounds and pounds of lobster and even surviving a broken tailbone. The building left its mark on Reed, but she left her mark on it too.

“You know what patina is?” Reed says. “(It’s) the presence of hands that have touched lots of things. And you know, we touched the banister many times, (we’ve) gone to the crazy little

mailboxes a bazillion times.”

But what made the most impact on Reed during her time in the building were the people who lived there. She fondly remembers the audiophile whose 500-plus records threatened to crumble

the building and the woman from San Francisco who wrote a letter declaring the famed Niedermeyer was the only place she wanted to reside.

Being its own savior

For building owner Asmar, its history and what it means to the community are what make it invaluable. And the building was not in its prime when Asmar got his hands on it. The faucets ran dry, the fire escapes were frightening and many of the building’s “characteristics” involved being in a state of disrepair.

Asmar had a plan, though. “It’s good for the building to save itself and sustain itself,” he says. “The only way you can do it is if this becomes an income-generating property worthy (of) the value of the lot.”

By Asmar’s logic, Magnolia’s Whisky & Wine is doing just that: helping the building save itself. It generates revenue, invites more people in and reminds Columbia that the Niedermeyer is loud and proud — helping its legacy live on.

The Niedermeyer is many things, but at its center, it is alive. With an eye-catching exterior, it seems from a different time amid boxy apartment complexes. Listen closely as you enter Magnolia’s doors and you might hear echoes from years gone by.

Explore new arts, eats and nature all within two hours of Columbia.

BY SARAH GOODSON

If there is one thing a lot of us Midwesterners love, it’s a good road trip. Driving can be cheaper and easier — allowing us to stop wherever we want, whenever we want. So, why not get out of Columbia and explore the nearby treasures our home state has to offer?

“I think maybe people have a mindset of what they think of a Midwest state, or what they might think of Missouri,”

says Alicia Wieberg, the communications manager of the Missouri Division of Tourism. “Prepare to be surprised by the unexpected. You can’t come into the state of Missouri and say that you didn’t find something you enjoyed.”

Vox has rounded up a list of can’tmiss stops for nature, culture and good eats (and drinks) from five different locations, all less than two hours from Co-

The Show-Me State provides a wide range of landscapes and activities within easy driving distance of Columbia.

lumbia. Get that travel bug out of your system by visiting these destinations.

HANNIBAL: 1 hour, 43 minutes

Culture: Get spooked by Haunted Hannibal Ghost Tours. Indulge in Hannibal’s rich history at 200 N. Main St. Visit hauntedhannibal.com for dates, times and tickets.

Eats: Fuel yourself at Mark Twain Di-

nette at 400 N. Third St. to fight off the lingering ghosts. Feast on its famous onion rings or homemade root beer.

Nature: Spend the day rolling on the river on the Mark Twain Riverboat with Hannibal River Cruises, 300 Riverfront Drive. Visit marktwainriverboat.com for dates, times and tickets.

HERMANN: 1 hour, 6 minutes

Culture: Experience the historic art by Wine Country Walldogs that show the town’s historic beauty, including the murals of Missouri Valley Ice Cream and the Ewald Bakery. Find a walking tour guide at visithermann.com.

Drinks: Become a wine connoisseur on the Hermann Wine Trail. Enjoy the town’s history and a variety of wine styles at six family-owned wineries. Visit hermannwinetrail.com for dates, hours and tickets.

Nature: To bring out even more of your nature-loving side, Grand Bluffs Conservation Area is located just outside of Hermann in Rhineland. The bluff over-

looks the Mississippi River with the Katy Trail passing south of this area.

JEFFERSON CITY: 35 minutes

Arts: Sing your heart out at Jefferson City’s Capital Region MU Health Care Amphitheater, 360 Service Drive. Tickets can be found online at crmuamphi theater.com.

Eats: The Landing Zone is going to be your kid’s next favorite spot, and honestly, yours too. Located at 500 Airport Road, in the middle of all the airport’s action, watch an airplane take off as you bite into a juicy burger.

Nature: Take a walk on the wild side at the Runge Conservation Nature Center, 330 Commerce Drive. The area has five different hiking trails to help you connect with nature again.

KANSAS CITY: 1 hour, 51 minutes

Arts: Observe 5,000 years of art at The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Find it at 4525 Oak St.

Eats: When you start to get hungry, head

Try visiting all 57 Missouri state parks. Print out a state map to keep track of your activities at each location. Find the list of parks and suggestions at mostateparks.com.

to Q39, 1000 W. 39th St., to see what Kansas City barbecue is all about.

Nature: And don’t miss the Lakeside Nature Center, which has fun for the whole family, including wildlife education programs, hiking trails and picnic pavilions.

Visit at 4701 E. Gregory Blvd.

ST. LOUIS: 1 hour, 54 minutes

Culture: The Old Courthouse at Gateway Arch National Park reopened May 3. It has gone through various changes and renovations to open up new exhibits and allow for more accessibility. The Old Courthouse is located at 11 N. Fourth St. Visit archpark.org for more details.

Eats: After your stop downtown, pop on over to University City’s music-themed restaurant Blueberry Hill. Grab a bite of some classic American food, have a beer and a burger and get tickets to the next show in the Duck Room. Blueberry Hill is located at 6504 Delmar Blvd.

Nature: To round out the day, enjoy scenery in Forest Park’s 190 acres of nature reserves at 5595 Grand Drive.

Your curated guide of what to do in Columbia this month.

BY ACIYA EL TAJOURY AND MATTHEW OSTHOFF

The Boone County Art Show returns to Central Bank’s downtown location for its 66th year. Attendees can view, purchase and vote for their favorite local artwork. A post-show ceremony crowns the fan favorite and a variety of other awards for participating artists. 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Oct. 4; 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. Oct. 5, Central Bank, free, 573-443-8838

Support local artists, artisans and small businesses in this charming market-style shopping experience featuring handcrafted goods, unique gifts and interactive experiences with over 70 vendors and businesses. 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. Oct. 5, Columbia Mall, free, 573-567-0811

What says fall better than seasonal crafts? Indulge in an afternoon of creations for adults at the Columbia Public Library. Participants will make scrapbook paper pumpkins that can serve as a seasonal decorative item. Noon to 4 p.m. Oct. 14, Columbia Public Library, free, 573-443-3161

In this 1987 play written by Stephen Mallatratt, an attorney hires an actor to help him tell the story of an unusual experience from his youth. The original production is notable for having only three actors in its cast. 7:30 p.m. Oct. 16-18 and 23-25, 2 p.m. Oct. 19 and 26, Talking Horse Productions, $20; $18 seniors and students 573-607-1740

Ever wanted to experience a real-life Night at the Museum? Visit the Museum of Art and Archaeology for one-of-a-kind

spooky tours of the museum, tricks and treats. Costumes are encouraged; open to all ages. 4-6 p.m., Oct. 24, Museum of Art and Archaeology, free, 573-882-3591

Columbia Reptile Expo

The Show Me Reptiles Show returns to Columbia, featuring a variety of vendors selling toys, pet supplies and, of course, reptiles. Attendees can view tarantulas, scorpions and pythons along with a variety of other cold-blooded creatures. There will also be animal shows and activities for those not interested in buying. 10 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. Sept. 28-29., Knights of Columbus Hall, $10-$15, 636-358-1281

Get your spook on with Columbia Public Library’s tour of the Columbia Cemetery. Learn about the history of cemeteries,

Saddle up at the CAFNR Showcase at South Farm. The College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources has been opening its farm up to the community since 2006 for this beloved fall event. Past years saw corn mazes, chestnut roasts and, in 2023, (above) cockroach races. Expect familyfriendly fun, food and educational opportunities.10 a.m. to 3 p.m. Oct. 4, South Farm Research Center, free, 573-882-7488

funeral practices and superstitions, all while immersing yourself in the spirit of the spooky season. 5:30 p.m. Oct. 6, Columbia Public Library, free, 573-443-3161

Missouri Chestnut Roast Festival

What’s roasting? Get into the fall spirit with this event hosted by Mizzou’s Center for Agroforestry. It features chestnut samples prepared three ways, hay wagon rides, an agroforestry farmers market and catered lunch provided by Pasta La Fata. 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. Oct. 18, MU Horticulture and Agroforestry, Research Farm, free, 573884-2874

Tommy Dorsey Orchestra

“The Sentimental Gentleman” of the Swing Era captivated audiences from 1935 to 1956 with his presence as a band leader.

Today, the Tommy Dorsey Orchestra keeps that tradition alive with music you’ll want to dance to, plus the occasional romantic ballad. 7 p.m. Oct. 15, Missouri Theatre, $51-$62, 573-882-3781

Kansas City native Tech N9ne will be performing in Columbia. Tech N9ne’s 35-year-long rap career has generated national acclaim, film roles, collaborations with the likes of Kendrick Lamar and millions of listeners across generational lines. He will be joined by Joey Cool, a fellow Kansas City native. 8 p.m. Oct. 16, Rose Music Hall, $45, 573-874-1944

Underground Detroit-based rapper Boldy James will bring his relaxed delivery to Rose Music Hall. Known for his vivid storytelling of street life, Boldy James has collaborated with artists such as Westside Gunn, Ghostface Killah and The Alchemist. 8 p.m. Oct. 17, Rose Music Hall, $28, 573-874-1944

Destin Conrad, a Grammy-nominated songwriter on Kehlani’s Crash for best progressive R&B album, is set to perform at The Blue Note with opener Mack Keane. Conrad released his debut album LOVE ON DIGITAL in April. It highlights modern love through voice notes, time zones and touchscreens. 8 p.m. Oct. 24, The Blue Note, $33-$87, 573-874-1944