by Jade Ferguson

In my career as a Photographer, I have always considered Portraiture to be a way of preserving memories. Through capturing the essence of the living human being we are creating a time capsule and proof of life to return to once those people are no longer of the physical world. Creating a means by which to remember, our photographic archives serve to remind us of the lives and lived experiences of those who came before us. Recently making an attempt to draw memory from my personal archive of family photographs I began to reflect on What Little Remains after the experience of living is through and bodies returned to naught but dust. I wondered whether it might be possible to create portraits of those no longer alive, to reincarnate the essence of the subject, posthumously.

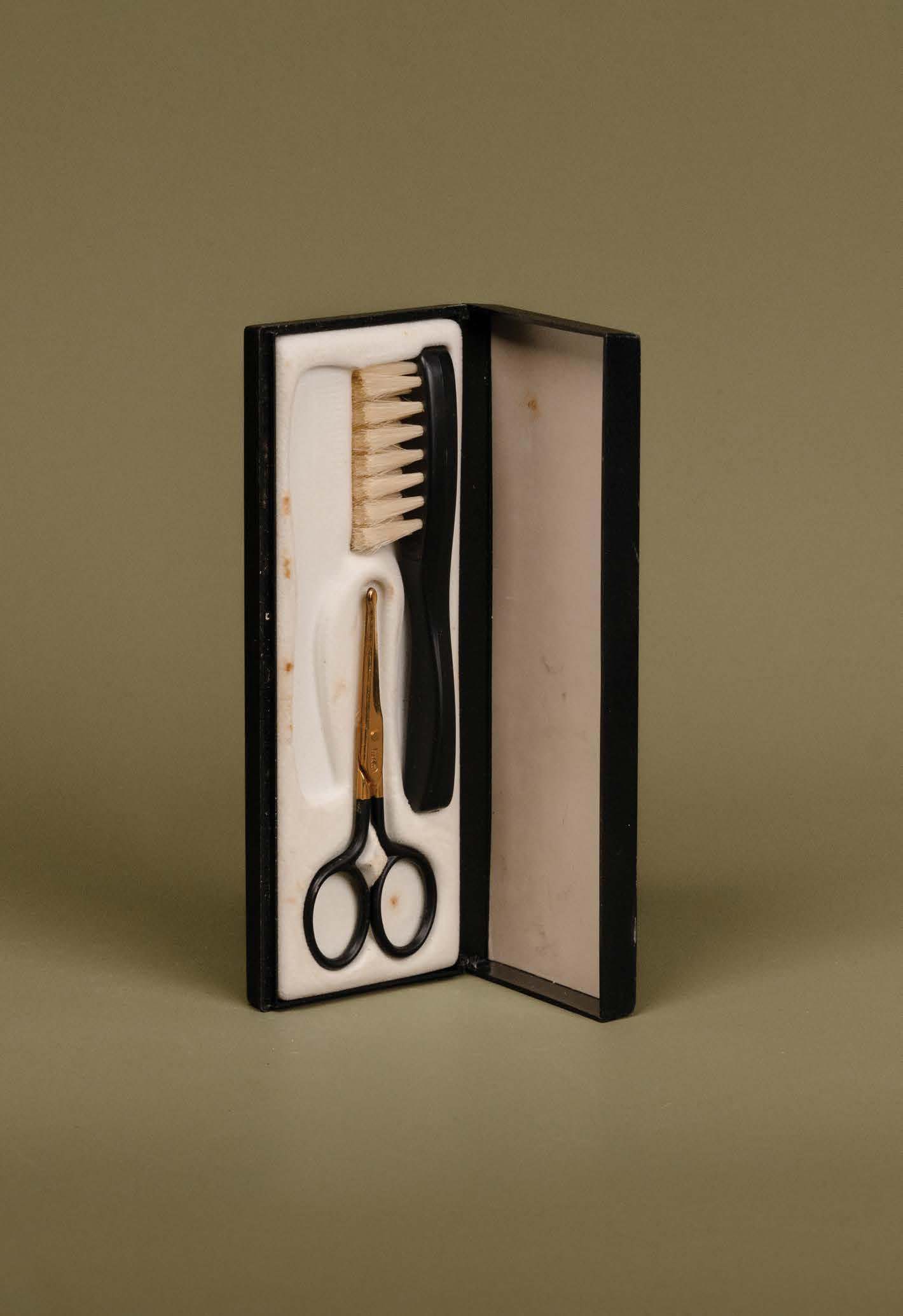

Searching initially for archived family photo albums, I came upon a single small plastic tub of physical belongings once owned by my late Opa. It was in this moment of existentialism that I made the frightening realisation that an entire lived experience could be reduced to this. Each moment of a life lived, every love, every win, every loss, every suffering, every single story, reduced to this: a single plastic tub. But it was what I found within that plastic tub that would inspire and enbolden me to attempt to reimagine Portraiture in a way that would reincarnate the essence and lost stories of my late grandfather. It became urgent to me that intergenerational stories untold and unshared might be otherwise lost if we don’t take the time to preserve them.

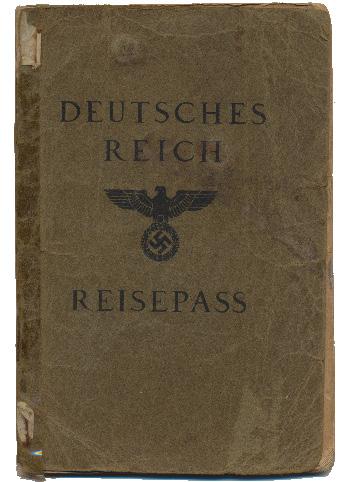

My Opa was known to me as a Photographer, a career in which I had proudly followed and felt a kinship with him over. Generally a stoic, and not always the warmest, my Opa never shared anything particularly personal with me during his lifetime. It was on my curious discovery of his written memoirs and few belongings that I uncovered a story and experience that would haunt him until his last living days. A Jewish man, hailing from German artistocracy and having fled war-torn Germany to New Zealand in the 1940’s with the help of the Rothschild family, my grandfather and great grandparents settled into a new life far removed from the one they had previously known. Householders in every sense of the word, their newly humbled existence became one of working in Barber shops.

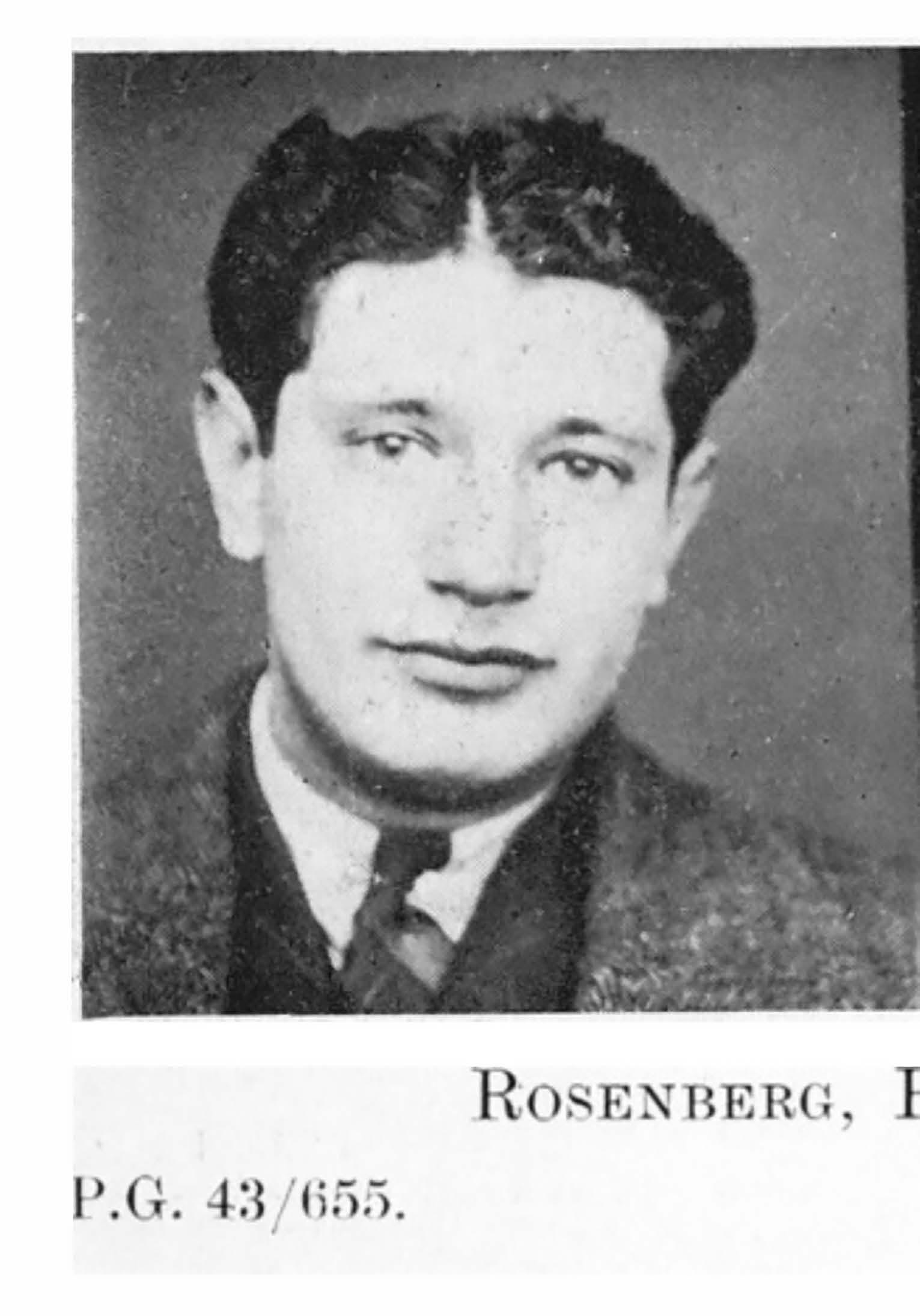

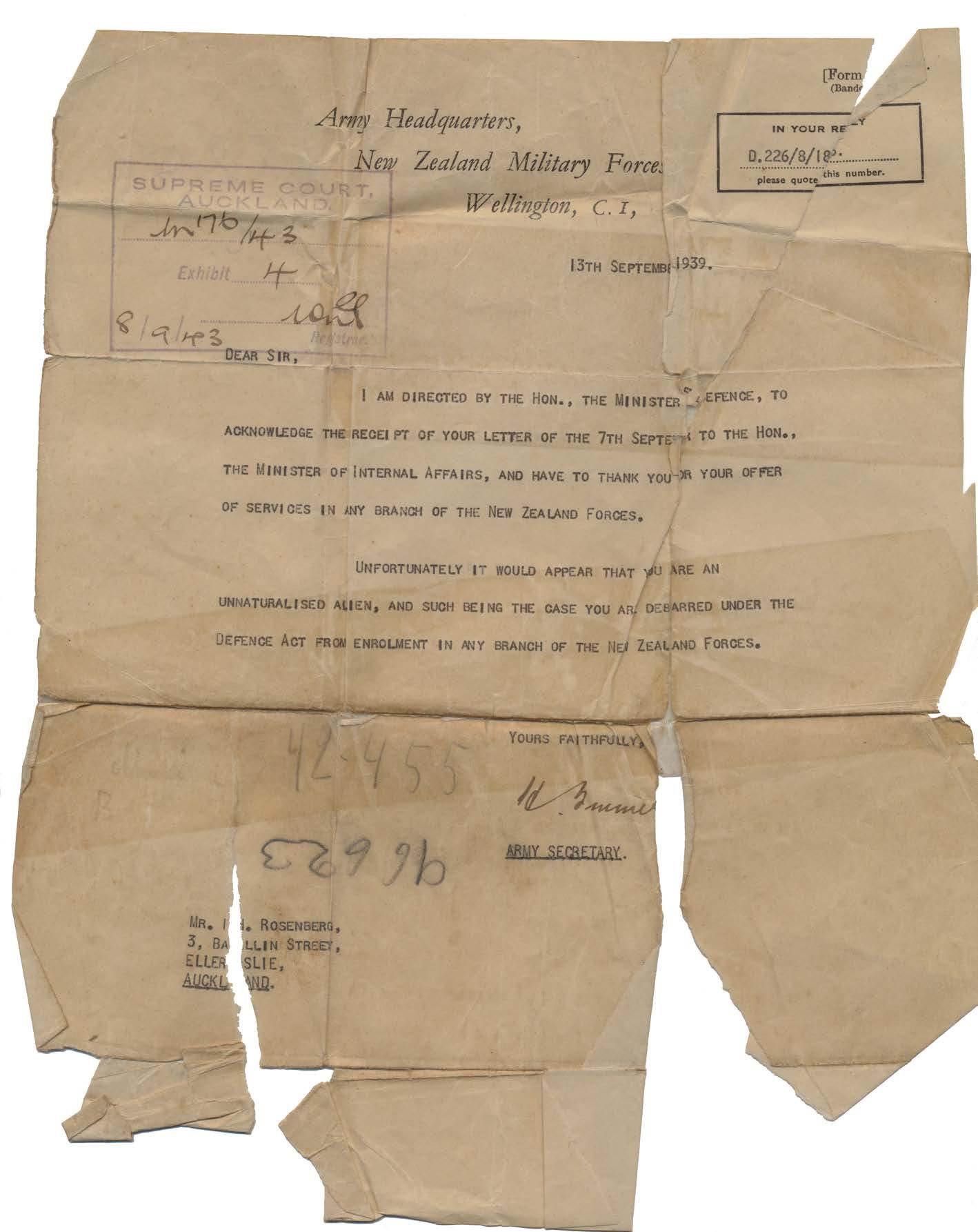

Rifling through the box of What Little Remains, stories of my Grandfathers life revealed themselves to me in broken parts. Translating documents and texts from both German and Hebrew, I was able to piece together a story that to me, was unknown until this day. A story that, though hard to re-tell through photographs and words, must be preserved for future generations. In short, my Opa was wrongfully accused and charged with a crime he did not commit. Serving 6 months in prison for the unlawful ownership of a US Military uniform, he lived nearly all of his life keeping this secret. He spent the late stages of his life in New Zealand, in pursuit of justice defending his good name.

In his words

by Heinz Isidor Rosenberg (aka Harry Rose)

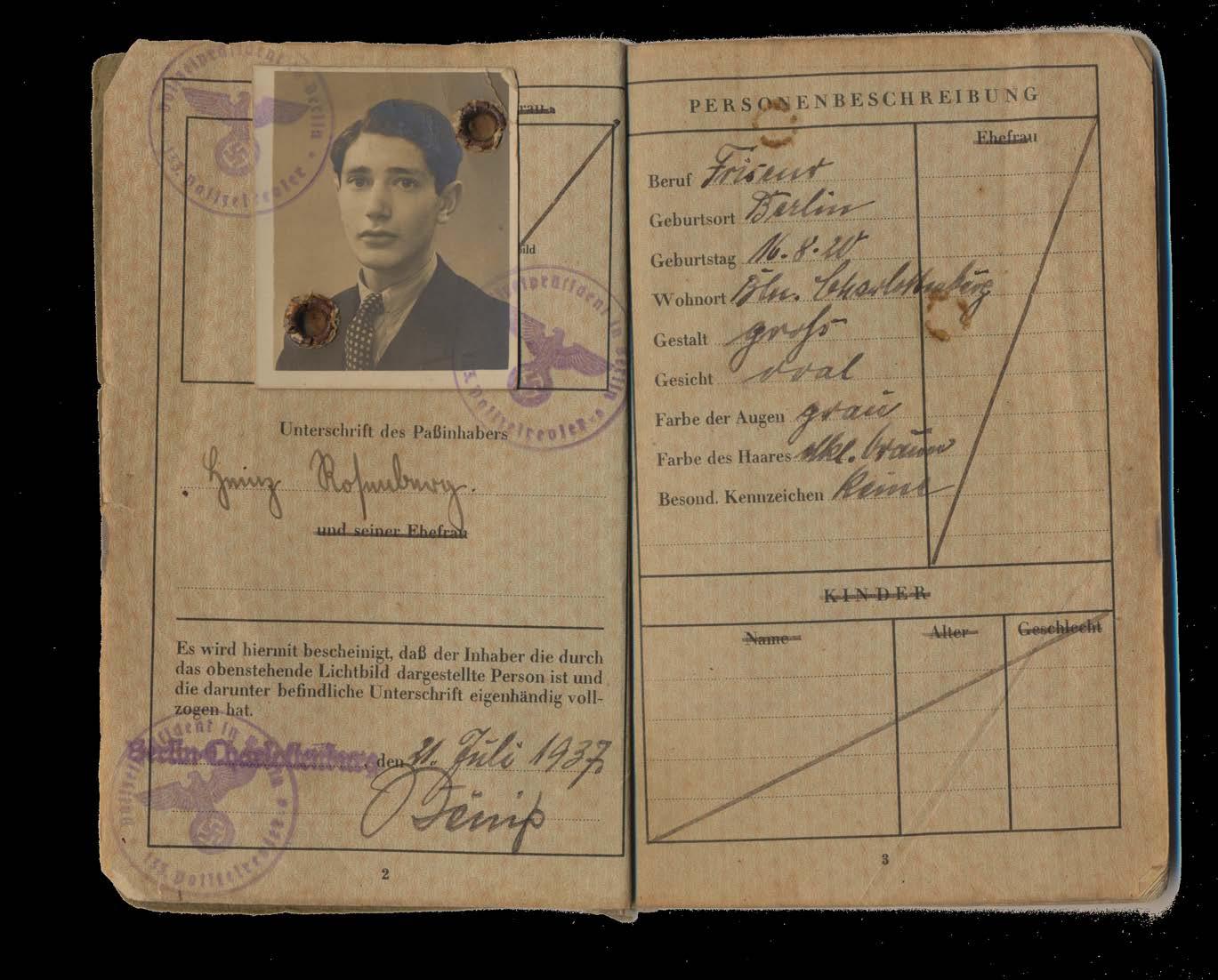

I was born on 16th August, 1920 at 11 minutes past 5 in the morning in Berlin at Alexanderstrasse 13, near the Alexanderplatz. It was a home birth on the top floor of a four storey building. The name given to me was Heinz Isidor Rosenberg. Isidor was my mother’s father’s name. My fathers name was Hermann. There were two separate apartments on the same floor, overlooking the street. The building, which was sizeable, had a backyard. The doctor gave me up for dead as the cord was wrapped around my neck three times and I was black. Fortunately the midwife perservered and bought me back around and here I am to tell my story.

As an only child I was very spoilt. My mother had a nursing sister to assist in looking after me. I had every imaginiable toy and a puppet set at home. Later because of congestion on my chest, the family had to move to Westerland on the Nordsee. I don’t recall how long we were there, maybe a year or two. We returned to Berlin to the same apartment. At the age of 19 I nearly died of blood poisoning. I had pricked myself with a steel nib and did not notice anything wrong initially. I told my mother that I could not practice piano because my arm hurt but she did not believe me. She was horrified to see a red line up my arm two days later and I was hospitalised for about a week after. Doctors cut my arm to relieve the pus. It was worse than having my tonsils removed, in my fathers arms, without anaesthetic.

I attended a state school and then went onto secondary school, skipping a couple of years. I learnt French for three years then started learning English in my fourth year. I failed my first year of English because the quality of English taught was very poor. My parents had visions of me attending Eton and had ordered catalogues. They had the means to do this. My father was a top hairdresser at Damentrost and we had a Ford Opel car. You were not poor if you owned a vehicle at the time.

My father eventually opened his own business in West Berlin under the title of Welstadtfriseur, Julius Rosenberg. My mother, Irma Julia Rosenberg worked there as a receptionist. My mother had three sisters and one brother, Uncle Willie who was a famous dress designer. Willie’s secord wife Norma was very elegant and taught me to smoke. Willie eventually ran off with his mannequin to England. Devastated, Norah commit suicide on his birthday. My father’s sister, Herta whose married name was Schmidt had a Photographic studio in Hannover. No one was aware that she was Jewish.

My parents were not Orthodox, but my father’s parents were very religious. My mother would fast on Yom Kippur and break the fast with roast pork! My father worked on Saturdays. My grandparents undertook my religious education. I celebrated my Bar Mitzvah in the synagogue located in the Fasenenstrasse on the 23rd August, 1933. I had to go to a Jewish school. I was a choir boy at a different synagogue in a choir conducted by the music teacher, Erwin Jospe, at the Jewish school. He played the organ as well as conducting the male choir, composed of men and boys. I was a pet pupil as I was the onyl one from the school in the choir. He called me Heini. I even attended his wedding. he went to the States and died in Israel. At one point my parents sent me to boarding school to teach me a lesson as I was naughty at times but this was short-lived as they missed me too much.

Some time after the Nazi’s came into power, they plastered swastikas over the shop windows. The Nazi’s incarcerated my father in 1935. He had made a remark to a customer, which was overheard. he may have said that Hilter was gay. My mother had torn up a pitcure of Hitler in the lunchroom and the staff, which included two manicurists, felt uncomfortable with it and left. The hairdresser, who was Jewish, stayed on but soon lost clients who didn’t want to have their hair cut by a Jew. When my father was incarcerated, my mother called in a non-Jewish hairdresser, an Austrian who was very good to us and carried on the business which managed to survive. Because he looked Jewish, Mittelechner on Lechner, as we liked to call him,he was beaten up a couple of times. My father was released from prison after 12 months instead of 15 for good behaviour. Not knowing whether the business would survive, I was sent to Hamburg to learn hairdressing from Siegfried Wolf, who was Jewish. I stayed with a Jewish family.

Siegfried Wolf had a seperate room for Orthodox Jews who were not able to shave with a razor. Two double-doors protected the non-Jewish customers from the smell of the mixture I had to make up. The chief ingredients were barium sulphuratum powder and chalk. My hair stank afterwards. I also had to oil the wooden floor and unbeliavably I had to cut the grass with scissors on my hands and knees. Until one day my mother arrived at the shop and said “get your things, we aren’t going back to Berlin, we are going to New Zealand”. My skull cap and tefillin were left under the seat of the Orthodox synagogue in Hamburg.

My parents were enabled to go to New Zealand through the efforts of the Rothschild family from Switzerland. Mrs Rothschild had asked about for a good ladies hairdresser and was recommended to my fathers business. July 31st we caught the train from Charlottenberg and then by ferry and train to London where we slept on the floor of Uncle Willy’s one bedroom flat in Maidavale. I remember the coronoation decorations still being up and catching the train to Southhampton. My fathers grandparents remained in Germany. My Grandfather died of natural causes. My grandmother was 91 when she was collected from an old people’s home and died in a concentration camp I assume in the gas chambers.

We departed on the ‘Largs Bay” on the Aberdeen and Commonwealth line. I was 16 at the time. We sailed past the Rock of Gibraltar and onto Malta where the ship docked. My parents went onshore for the day. We stopped at Portside which was very hot but we did not venture very far in a strange city. It was late afternoon when we arrived there but the shops remained open because of the ship. We departed again about midnight. The next stop was Columbo. Mostly the sea had been like glass but we encountered a severe storm three days out from Columbo. China was smashed to smithereens. Ropes were strung out across the deck for people to hang onto. Most people were too sick to eat.

We continued on to Freemantle and I remember watching the ship leave the port around 2am. Jewish New Year fell while we were sailing between Adelaide and Melbourne. A number of Polish refugees were on board and they had a Torah. I acted as go-between with my school boy English. The ships bursar allowed us to celebrate Rosh

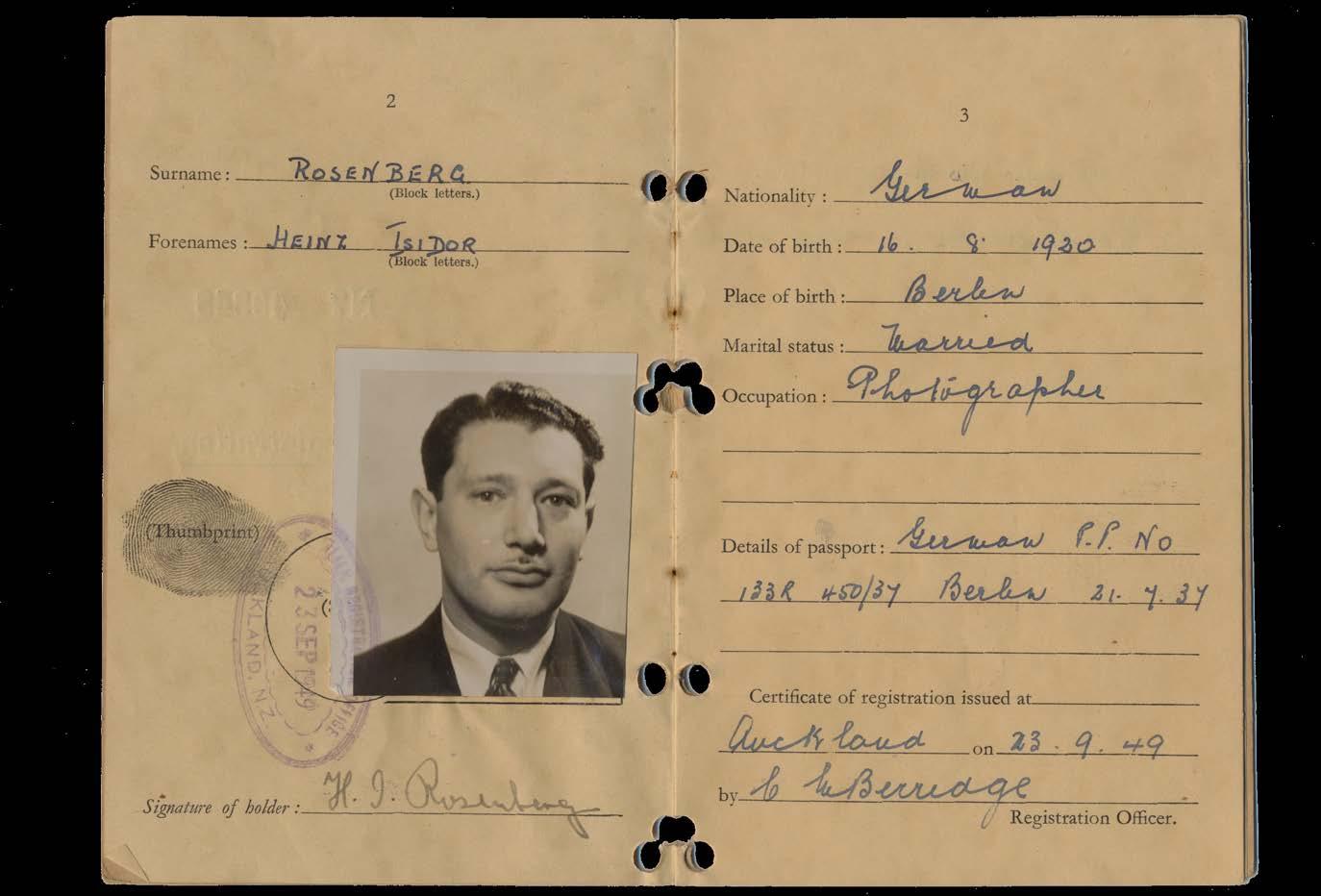

Hashanah in the ships hospital. I did a little hair cutting on board the ship and earned a little money on the side. We spent two nights in Sydney and slept on board. We changed ships and left for Auckland on the ‘Wanganella’. Arriving in Auckland on the morning of Yom Kippur 14th July, we were met by Rabbi Astor. Our first evening in Auckland was on Yom Kippur so we went to the synagogue. To my surprise, one of my former classmates from the Jewish school in Berlin, Gerhardt was in the synagogue. His father Dr Wagener was a dentist. Although we weren’t close in Germany, we became firm friends in New Zealand.

We were taken to a boarding house in City Rd which is still there. My father got a job at a ladies hairdressing salon at Smith and Caughey. He was given the name of Julian Rose by Smith and Caughey, a name which he used throughout his working life. My father had arranged to send out our furniture and hairdressing equipment including mirrors, marble shelves and basins by ship. After it arrived, he found premises to rent in His Majesty’s Arcade and his clients followed him. My father found a barber, William Albert Hounslow in Customs Street West who took me on as an apprentice. I completed the remaining 18 months of my apprenticship there. He was a good boss and friend, but was sadly killed in a motorcycle accident.

After my 18 month apprenticeship I was a fully qualified barber but no one wanted to pay someone younger than 21, the five pound a week to which I was entitled. I did some relieving work in Paeroa and Taumaranui where I was paid full wages. I was in Taumaranui when war was declared. At the time a friend of mine was a street Photographer and was making good money, so he introduced me to his boss. I was happy to leave hairdressing which Iwasn’t enjoying. As Photographers, we didn’t receive wages but 15% commission on photos we sold and we were making about 8 pound a week. I worked as a Photographer for different firms, Reeds and Wisemans before starting my own business.

I had to be shown how to use the camera at Cabaret Photographs, a firm I was introduced to by a boy who was a Jewish refugee. I became involved romantically with the girl behind the desk there. Her name was Patricia Joyce Hayter. Her mother had died and she had inherited her house in Kohimarama. Her father owned the Whakatane Hotel where we had our honeymoon. The marriage was arranged quickly as she was pregnant. My parents and her guardian gave permission because of her age. While I was on honeymoon, I received a call from my mother to say that i had to come back to Auckland and report to the Ellerslie Race Course where the Army was stationed. I was registered with the First Field Company New Zealand Engineers, issue a rifle and uniform and sent home because I had a sore throat. I had to report for sick parade the next day and was told not to come back until I was better. On the fourth day I received a phone call and was told to return my belongings because they had made a mistake in accepting me as I was an unnaturalised alien. I was paid seven pound, 6 shillings for my four days in the army but was faced with being a civillian again. I got a job as a Barber again, but didn’t stay long. My marriage also was short-lived. My teenager wife did not want to keep the baby and so my mother legally adopted her, her name was Anita.

When the American Army divisions arrived in New Zealand, I applied for a job as a barber with the canteen board at the 39th General Hospital in Cornwall Park. It was run by a civillian who was a kiwi. There were three American soldiers who were also barbers in the barbershop which was run by the canteen and we all had the right to purchase anything from the canteen at cheap rates. I still wanted to fight, but I was turned down by the American Army. During my time at the canteen, I acquired some parts of the American Army uniform - a jacket, a cap, a shirt but no trousers. The American soliders were happy to pass on these items to me because I loved to collect memorabilia and have a huge stamp collection. One day I mentioned in passing to a customer that I had parts of the uniform but that I was still loooking for a pair of trousers and shoes to complete it. I didn’t realise at the time that I was speaking with a member of the Military Police. Unfortunately this information was then passed onto the NZ Police. The American army shirt was hanging up when I was arrested. Even the cigarettes I had purchased were confiscated. I was sentenced to six months imprisonment. My lawyer was Robinson. The presiding magistrate gave me cold comfort saying ‘a leopard does not change its spots’. He got to know me later as a Photographer and purchased photos I took at events.

It was catastrophic for me to be imprisioned. I was in a one person cell with a chamber pot which I had to empty each morning and I slept on a straw mattress. I only lasted two days in the quarry at Mt Eden, it was too tough for me. The warden was sympathetic and he allowed me to cut hair for extra tobacco. I learnt to splice matches into four to make them last. I learned to sew there and was told that I was qualified as a Tailor when I put a sewing machine needle through my finger which was extremely painful. I made prisoners uniforms, wardens uniforms and repaired postal bags. I sat next to murderers and hardened criminals who showed no remose. Mario, the librarian was there for life. By and large I kept to myself. One non-Jewish man, an incorrigible safe-breaker was interested in Judaism and was very good to me. He told me about the existence of some scrolls in Israel which were later discovered. The wardens, without exception were very kind, realising that I was not a criminal. My mother visited. The Rabbi came once. He said “Serves you right, Read job” and left. I did. The bible but not much other reading material in the prison. I was let out three weeks early which was unusual for a six months entence. Tears streamed down my face at my release. I could not stop crying.

I opened my own business in the 50’s on the corner of East St and Karangahape Rd. I bought the upstairs premises from the Post Office and created a dark room and studio, Harry Rose and I was considered among the top three Wedding photographers in Auckland at the time. I had three weddings every Saturday in the summer and then the nights might have one or two 21st birthdays. I would be home by midnight most nights. I also did some newspaper photography. I purchased a war surplus radio and the traffic and police were all on the same frequency so I could be there quickly. With the advent of duty free cameras the business became less profitable and I sold it in the 1960’s. I was also ready for a change and opened up a Limousine business which I really enjoyed. I got to know Howard Morrison, Glen Campbell, Charlie Pride, Rita Hayworth among others during my time as a chauffeur.

by Jade Ferguson

As you have just read, my Opa lived both a traumatic and interesting life full of fascinating stories. In finding and reading through his memoirs I discovered that he failed to share though, was the resolution to the story of his incarceration prior to his passing. In November 2004, New Zealand introduced the Criminal Records Clean Slate Act which allows for a criminal record to be hidden from the public if the person is eligible. Unfortunately his case was ineligible at the time for consideration as he had been imprisoned.

Determined to clear his name, my Opa penned a pleading letter to the late Queen Elizabeth II in 2007, to which he received a response referring his case to the NZ Governor General and thereafter a court hearing was presented before the Judge. On hearing his case (which had been significantly covered in news media preceeding the court date) and witnessing the evidence, the presiding Judge made the order that a gross miscarriage of justice had been served. The judge issued an apology and retraction of my Opa’s conviction and criminal record and stated that he had been “proven to be an honourable citizen and your good name has been restored”.

In closing the case, the Judge left my Opa with these words.

Shalom. Go in peace.