AVATAR: FIRE AND ASH

Welcome to the Winter 2026 issue of VFX Voice!

Happy New Year to VES members and VFX Voice readers worldwide! We look forward to bringing you an exciting year of insightful, in-depth features focused on the art and craft of visual effects for entertainment and beyond.

In our Winter cover story on Avatar: Fire and Ash, writer-director James Cameron describes the dramatic evolution of Avatar’s lead characters and the possible future of the franchise with AI. In addition to Fire and Ash, we also spotlight the artistry behind likely contenders for Best Visual Effects at the upcoming 98th Academy Awards, as leading VFX supervisors recount the highlights that defined their work.

Elsewhere in this issue, director Guillermo del Toro explains the role VFX plays in his gritty Frankenstein, Shakespeare’s Hamlet is reimagined through the lens of Mamoru Hosoda’s animated Scarlet, and we profile ILM Digital Artist Paige Warner and Epic Games Co-Founder/CEO Tim Sweeney, the visionary driving Unreal Engine and the ongoing VP revolution.

To anchor our State of the Industry 2026 coverage, we turn to VFX professionals for a diversity of views on the outlook going forward. We also examine how smaller studios adapt to shifting markets, and we continue to chronicle AI’s impact on every corner of the global industry. Then, in Tech & Tools, we unpack the ultimate VFX supervisor’s location survival kit.

Finally, as a special bonus to VES members around the globe who share a common passion for photography, we are delighted to present “A World’s-Eye View,” a unique showcase of original photography by VES members, as selected by a VES panel. Enjoy!

Cheers!

Kim

Davidson, Chair, VES Board of Directors

Nancy

Ward, VES Executive Director

P.S. You can continue to catch exclusive stories between issues only available at VFXVoice.com. You can also get VFX Voice and VES updates by following us on X at @VFXSociety and on Instagram @vfx_society.

FEATURES

8 THE VFX OSCAR: PREVIEW

Meet the contenders for this year’s top prize for the best in effects.

36 VFX TRENDS: SMALLER STUDIOS

How smaller companies diversify to navigate constant change.

46 PHOTOGRAPHERS SHOWCASE: WORLD’S-EYE VIEW

A curated gallery of original photographs by VES members.

56 FILM: FRANKENSTEIN

Birthing the Creature for Guillermo del Toro’s artistic reimagination.

62 PROFILE: TIM SWEENEY

Epic Games Founder/CEO on the convergence of film and games.

68 COVER: AVATAR: FIRE AND ASH

James Cameron sharpens focus on characters, creativity, detail.

76 PROFILE: PAIGE WARNER

ILM Digital Artist bridges the gap between technology and artistry.

82 INDUSTRY: OUTLOOK ‘26

The VFX industry surges forward while searching for consistency.

88 VFX TRENDS: MAN, MACHINE & ART

Training AI to enhance the artist experience and creative control.

94 FILM: SCARLET

Oscar-nominated anime director Mamoru Hosoda adapts Hamlet

100 TECH & TOOLS: VFX SURVIVAL KIT

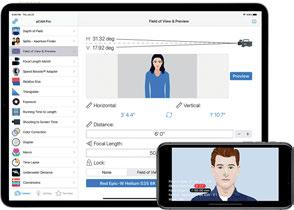

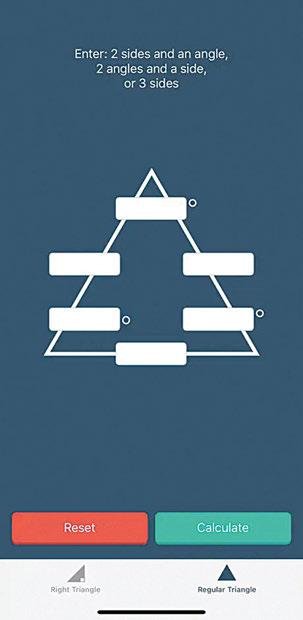

iPad, iPhone apps fill many roles, yet old-school essentials endure.

DEPARTMENTS

2 EXECUTIVE NOTE

106 VES NEWS

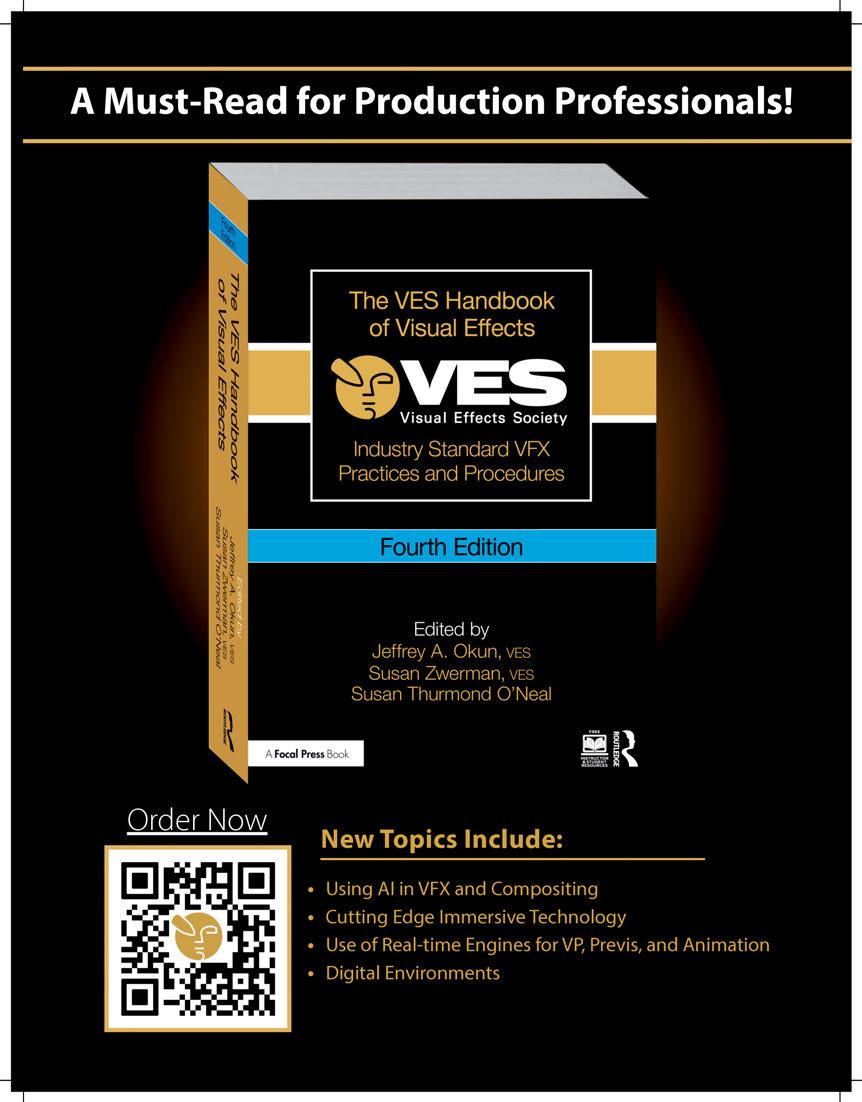

109 THE VES HANDBOOK

110 VES SECTION SPOTLIGHT – GERMANY

112 FINAL FRAME – AVATAR’S VFX LEGACY

ON THE COVER: Oona Chaplin as the intense leader of the Ash People in Avatar: Fire and Ash. The goal for the Ash People was to create a striking visual difference, both in their culture and landscape. (Image courtesy of 20th Century Studios)

VFXVOICE

Visit us online at vfxvoice.com

PUBLISHER

Jim McCullaugh publisher@vfxvoice.com

EDITOR

Ed Ochs editor@vfxvoice.com

CREATIVE

Alpanian Design Group alan@alpanian.com

ADVERTISING

Arlene Hansen arlene.hansen@vfxvoice.com

SUPERVISOR

Ross Auerbach

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Trevor Hogg

Chris McGowan

Barbara Robertson

ADVISORY COMMITTEE

David Bloom

Andrew Bly

Rob Bredow

Mike Chambers, VES

Lisa Cooke, VES

Neil Corbould, VES

Irena Cronin

Kim Davidson

Paul Debevec, VES

Debbie Denise

Karen Dufilho

Paul Franklin

Barbara Ford Grant

David Johnson, VES

Jim Morris, VES

Dennis Muren, ASC, VES

Sam Nicholson, ASC

Lori H. Schwartz

Eric Roth

Tom Atkin, Founder

Allen Battino, VES Logo Design

VISUAL EFFECTS SOCIETY

Nancy Ward, Executive Director

VES BOARD OF DIRECTORS

OFFICERS

Kim Davidson, Chair

Susan O’Neal, 1st Vice Chair

David Tanaka, VES, 2nd Vice Chair

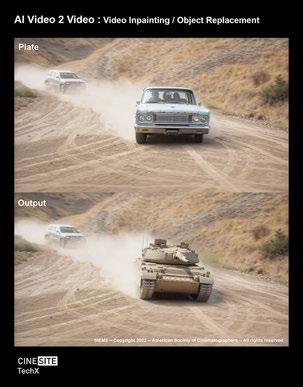

Rita Cahill, Secretary

Jeffrey A. Okun, VES, Treasurer

DIRECTORS

Neishaw Ali, Fatima Anes, Laura Barbera

Alan Boucek, Kathryn Brillhart, Mike Chambers, VES

Emma Clifton Perry, Rose Duignan

Dave Gouge, Kay Hoddy, Thomas Knop, VES

Brooke Lyndon-Stanford, Quentin Martin

Julie McDonald, Karen Murphy

Janet Muswell Hamilton, VES, Maggie Oh

Robin Prybil, Lopsie Schwartz

David Valentin, Sean Varney, Bill Villarreal

Sam Winkler, Philipp Wolf, Susan Zwerman, VES

ALTERNATES

Fred Chapman, Dayne Cowan, Aladino Debert, John Decker, William Mesa, Ariele Podreider Lenzi

Visual Effects Society

5000 Van Nuys Blvd. Suite 310

Sherman Oaks, CA 91403

Phone: (818) 981-7861 vesglobal.org

VES STAFF

Elvia Gonzalez, Associate Director

Jim Sullivan, Director of Operations

Ben Schneider, Director of Membership Services

Charles Mesa, Media & Content Manager

Eric Bass, MarCom Manager

Ross Auerbach, Program Manager

Colleen Kelly, Office Manager

Mark Mulkerron, Administrative Assistant

Shannon Cassidy, Global Manager

Adrienne Morse, Operations Coordinator

P.J. Schumacher, Controller

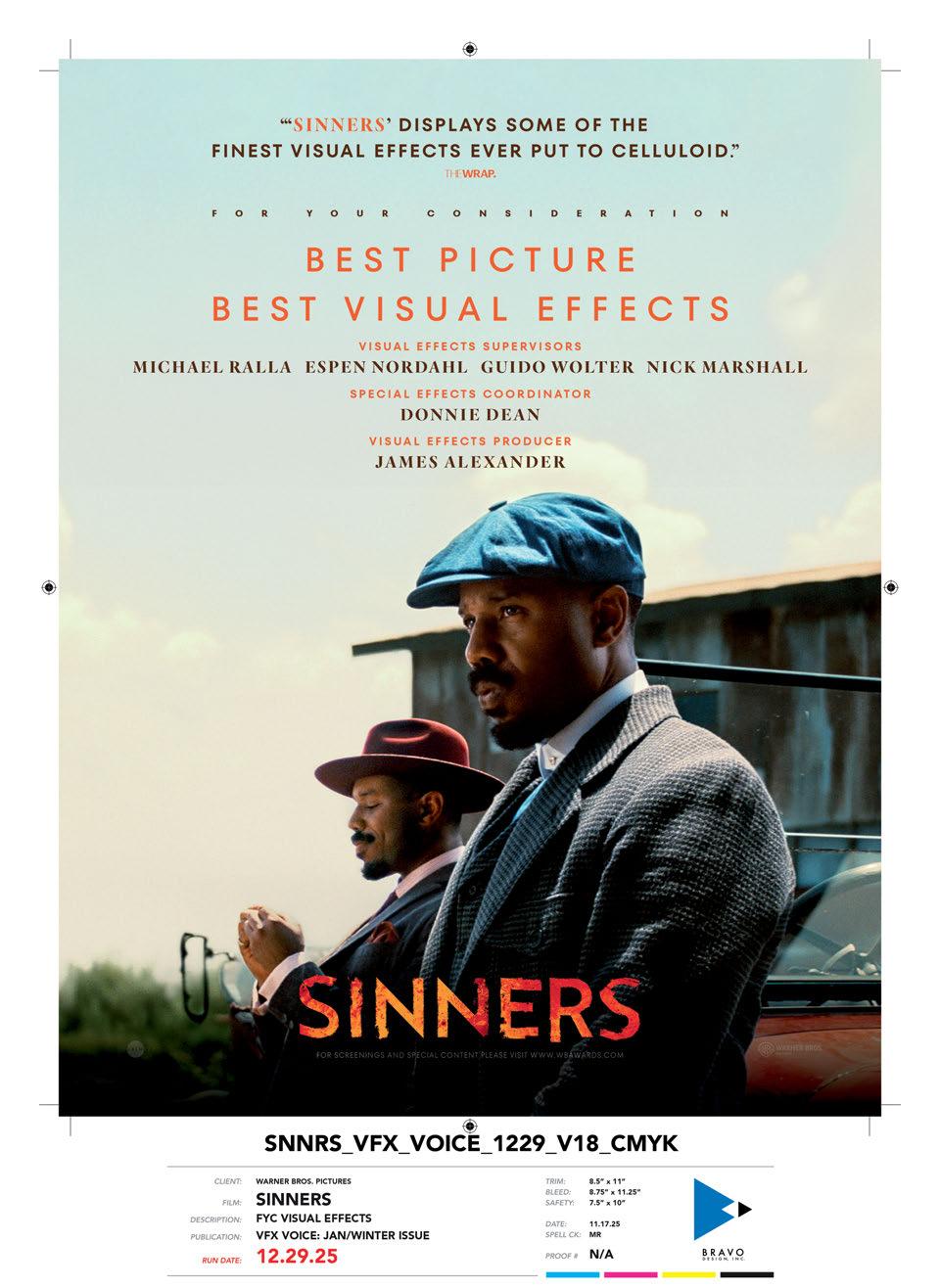

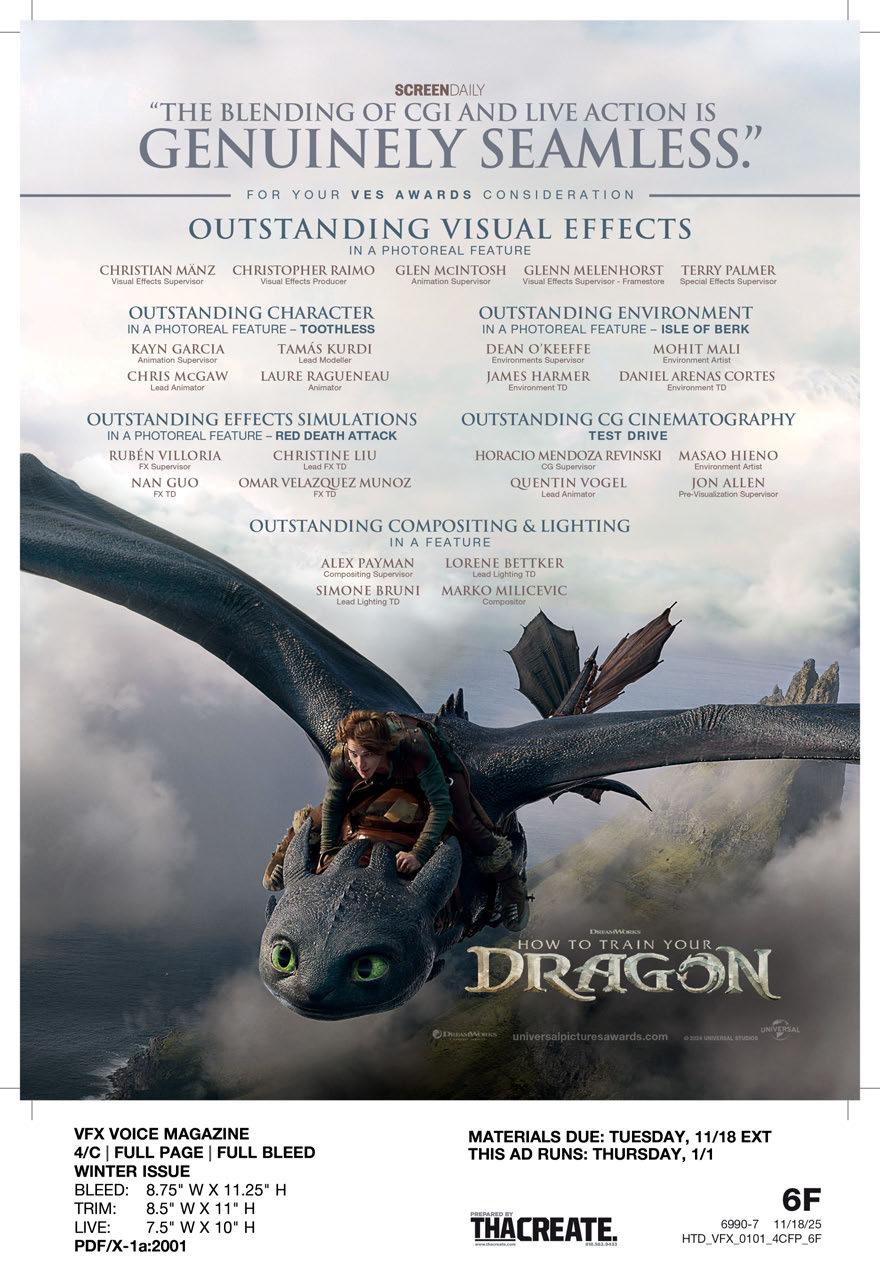

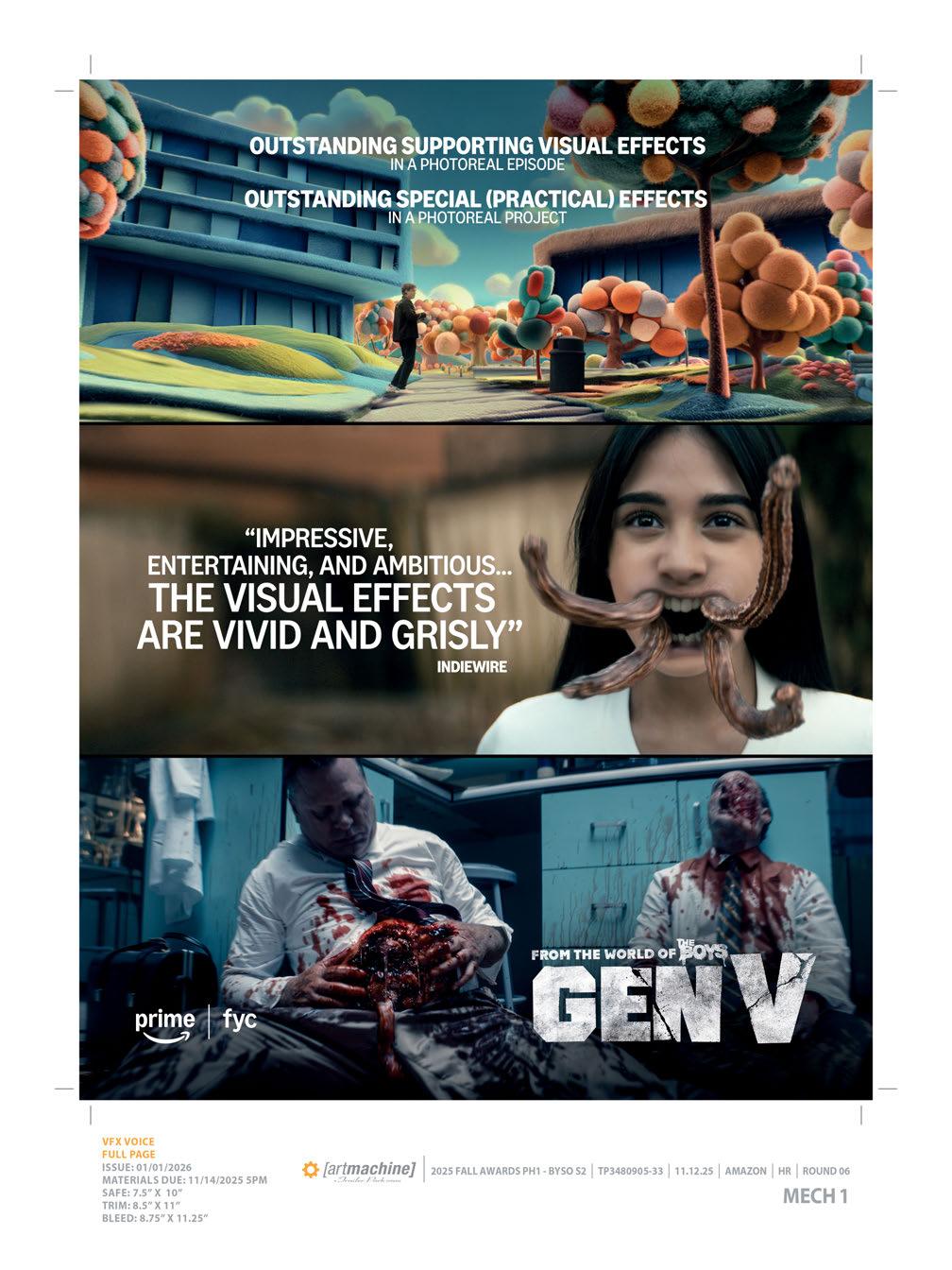

2026 OSCAR CONTENDERS BLEND THE STORYTELLING POWERS OF PRACTICAL AND DIGITAL EFFECTS

By BARBARA ROBERTSON

This year’s Best Visual Effects Oscar contenders display a full range of visual effects from invisible effects supporting dramatic stunts and action to full-blown fantasies with a few superheroes and anti-superheroes in between. Visual effects artists created all four elements for these films – dirty, earthy effects; creatures, characters and vehicles flying through the air; fire and its aftermath; and amazing water effects. VFX also supported an immersive, unflinching reality for a documentary-style film; immersive, fanciful, beautiful other worlds with talking animals, realistic animals and unusual characters; a love story or two tucked into a spectacle; a thriller; and inside a fable, a warning for our times.

Director James Gunn wanted to create a new version of Superman, not a sequel or prequel, one that was closer to the spirit of the comic books. (Image courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures)

OPPOSITE TOP TO BOTTOM: For Avatar: Fire and Ash, more emphasis was placed on artistry than technical breakthroughs. (Image courtesy of 20th Century Studios)

Everything in Tron: Ares has a light line component to it. Most characters wear round discs rimmed with light on their backs. Light trims all the suits and discs. (Image courtesy of Disney Enterprises)

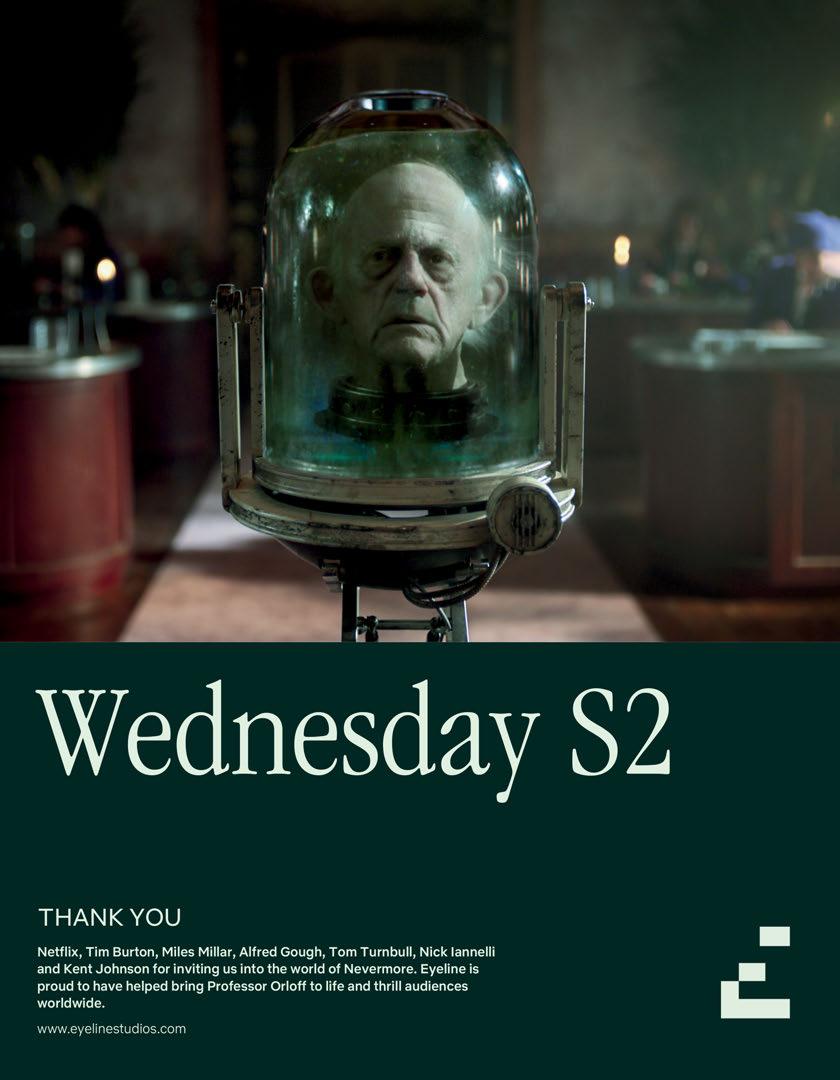

The visual effects in Warfare are entirely invisible, which contributed to the film’s authenticity. Cinesite served as the sole vendor on Warfare and was responsible for approximately 200 visual effects shots. (Image courtesy of DNA Films, A24 and Cinesite)

Many of the films have an extra challenge: to go one better than before. Wicked: For Good is a sequel to last year’s Best Visual Effects Oscar nominee and Mission: Impossible – The Final Reckoning is a sequel from the year before. There are also sequels for other previous award winners: Superman won a Special Achievement Award for visual effects in 1978; The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1998) and Superman Returns (2006) received Oscar nominations. Three previous Oscar winners launched sequels last year: Avatar, Avatar: The Way of Water and Jurassic Park, as did the Oscar-nominated Tron

Only two highlighted films are not sequels: Warfare and Thunderbolts*, although Thunderbolts* is part of a continuing Marvel Universe story. Here, leading VFX supervisors delve into stand-out scenes that elevated eight possible 2026 Oscar contenders. Strong contenders for Oscar recognition not profiled here include Mickey 17, The Fantastic Four: First Steps and The Running Man, among others.

TOP:

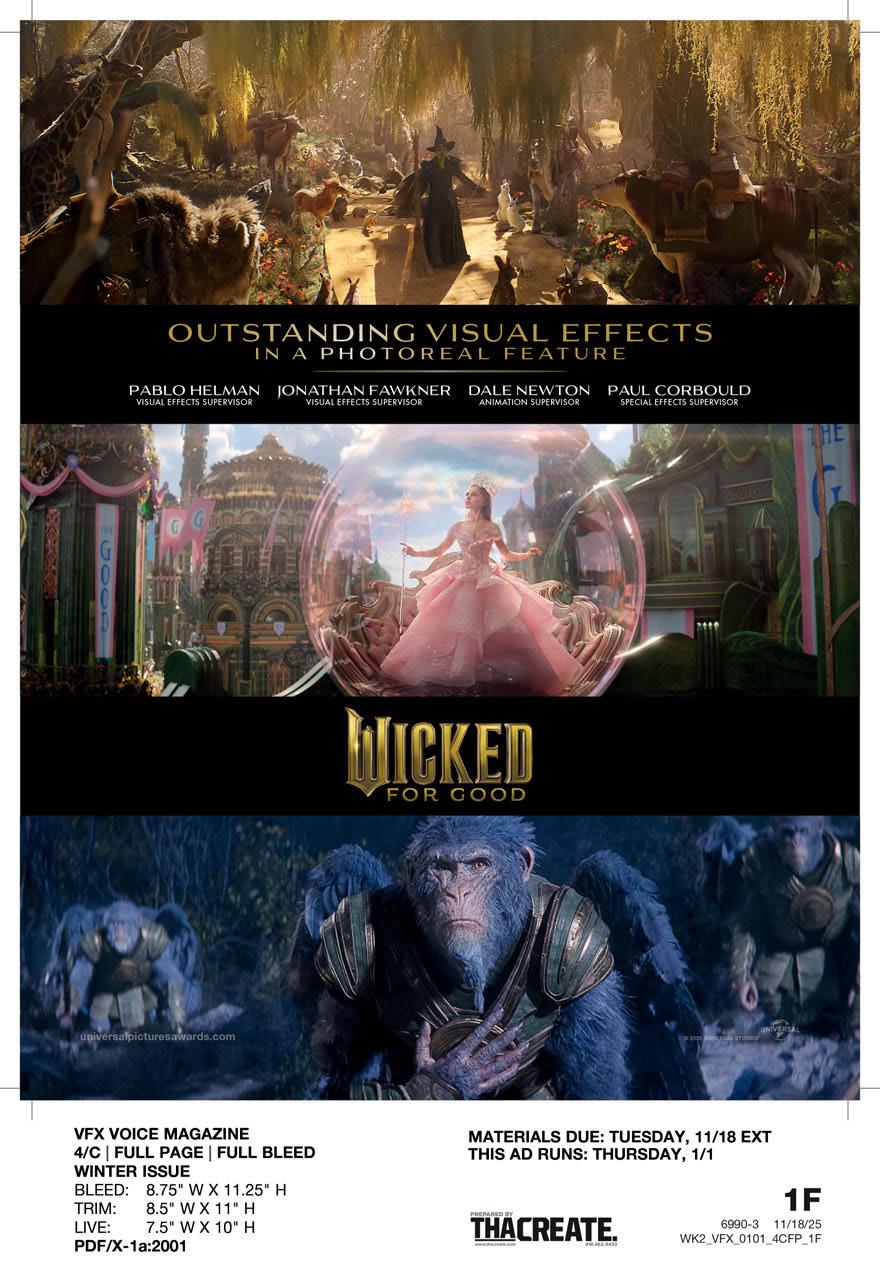

WICKED: FOR GOOD

Industrial Light & Magic’s Pablo Helman, Production Visual Effects Supervisor for Wicked: For Good, earned an Oscar nomination last year for Wicked, which was filled with complex sets, characters, action sequences and animals enhanced with visual effects. According to Helman, that was just the beginning.

“Before, we had an intimate story full of choices,” Helman says. “Now, it opens up to show the consequences of those choices within the universe of Oz. We shot as much in-camera as possible and still have around 2,000 visual effects shots. But the scope is a lot bigger. This film has everything – special effects, practical sets and visual effects all working together. We see Oz with banners all over the territory. We have butterflies, a huge monkey feast, a grown-up lion, train shots, new Emerald City angles, the Tin Man and Scarecrow transformations, crowds, girls flying on a broom among the stars, rig removal, environment replacement, a mirrored environment, a tornado, hundreds of animals…” Animals with feathers and fur, talking animals, animals that interact with actors, hundreds of animals in set pieces and an animal stampede.

As in the first film, the Wizard is out to get the animals. “We listen to the animals’ thoughts when they’re imprisoned; to what happened to them,” Helman says. “We developed new techniques for them and adopted a different sensibility when it came to animation. Action films typically let the cuts control the pacing and viewer focus. But for this film, thanks to Jon M. Chu [director] and Myron Kerstein [Editor], we were able to take the time we needed to get characters to articulate thoughts.”

Animators used keyframe and motion capture tools. Volume

capture for shots within big practical sets helped the VFX team handle crowds of extras. ILM, Framestore, Outpost, Rising Sun, Bot, Foy, Opsis and an in-house VFX team provided the visual effects.

One of the most challenging sequences is when Glinda (Ariana Grande) sings in a room with mirrors. “We had to figure out how to move the cameras in and out of the set, which is basically a two-bedroom apartment, during the three-minute sequence,” Helman explains. “We had to show both sides, Glinda and her reflection. We had to move the walls out, move the camera to turn around, and simultaneously put the set back in. Multiple passes were shot without motion control. Sometimes, we used mirrors. Sometimes, they were reference that we replaced with other views. It was very easy to get confused, and we didn’t have much leeway. It was all tied to a song, so we had to cut on cues. It took a lot of smart visual effects.”

The crew used Unreal Engine to interact and iterate with production design, to look at first passes, to conceptualize, and previs and postvis the intricate shots in the film. For example, in another sequence, Elphaba (Cynthia Erivo) flees on her broom through a forest to escape the Wizard’s monkeys. The crew used a combination of plates shot in England and CG. But it’s more than a chase scene. “She escapes without hurting anyone,” Helman says. “That’s part of the character arc for the monkeys. In this movie, they switch sides.”

Wicked: For Good has a message about illusion that was important to Helman. Glinda’s bubble is not real. The Wizard is not real. “And he lies a lot,” Helman adds. “One thing I like about this film is the incredible message about deception. And hope. Elphaba

TOP: In the Grid in Tron: Ares, digital Ares can walk on walls. When Ares moves into the real world, he obeys real-world physics. (Image courtesy of Disney Enterprises)

BOTTOM: Avatar: Fire and Ash introduces a new clan, the Ash people, and a new antagonist, Varang, leader of the Ash, providing an opportunity for the studio to further refine its animation techniques. (Image courtesy of 20th Century Studios)

BOTTOM: Contributing to the integration of the vault fight was the burning paper found throughout the environment in Thunderbolts*. The live-action blazes from Backdraft served as reference. (Image courtesy of Digital Domain and Marvel Studios)

tries to persuade the animals not to leave. But they take a stand; they decide to exit Oz. That’s married to the theme of deception and what we can do about it. It’s such a metaphor for the time we’re living in. It’s very difficult to go through this movie and not get emotional about it.”

WARFARE

Warfare, an unflinching story about an ambush during the 2006 Battle of Ramadi in Iraq, has been described as the most realistic war movie ever made. Former U.S. Navy SEAL Ray Mendoza’s first-hand experience during the Iraq war grounded directors Mendoza and Alex Garland’s depiction. The film embeds audiences in Mendoza’s fighting unit as the harrowing tale unfolds in real time. While critics have praised the writers, directors and cast, few mention the visual effects. “The effects weren’t talked about at all,” says Cinesite’s Production Visual Effects Supervisor Simon Stanley-Clamp. “They are entirely invisible.” In addition to Cinesite’s skilled VFX artists, Stanley-Clamp attributes that invisibility and the accolades to authenticity. “Ray [Mendoza] was there,” he notes. “He knew exactly what something should look like.”

Cinematographer David J. Thompson shot the film using hand-held cameras, cameras on tripods and, Stanley-Clamp says, a small amount of camera car work. “We did have a crane coming down into the street for the ‘show of force,’ but that was the only time we used a kit like that,” he says. The action takes place largely within one house in a neighborhood, and what the trapped SEALs could see outside – or the camera could show. In addition to a set for the house, the production crew built eight partial houses to extend the set pieces. These buildings worked

TOP: Warfare is an unflinchingly realistic story about an ambush during the 2006 Battle of Ramadi in Iraq. The visual effects crew added the muzzle flashes, tracer fire hits and smoke, with authenticity foremost. (Image courtesy of DNA Films, A24 and Cinesite)

for specific angles with minimal digital set extension. Freestanding bluescreens and two huge fixed bluescreens were also moved into place. Later, visual effects artists rotoscoped, extended the backgrounds, added air conditioning units, water towers, detritus and other elements to create the look of a real neighborhood.

“For city builds, we scattered geometry based on LiDAR of the sets,” Stanley-Clamp says. Although the big IED special effects explosion needed no exaggeration, the crew spent two days shooting other practical explosions and muzzle flashes for reference. During filming, the actors wore weighted ruck-sacks and used accurately weighted practical guns. “We shot 10,000 rounds of blanks in a day during the height of the battle sequence, and we had a lot of on-set smoke,” Stanley-Camp says. In post, the visual effects crew added the muzzle flashes, tracer fire hits and more smoke, again with authenticity foremost. “Ray [Mendoza] knows how tracer fire works, that it doesn’t go off with every bang,” Stanley-Camp says. “The muzzle flashes were in keeping with the hardware being used. In the final piece, we almost doubled the density of smoke. There’s a point where there’s so much smoke that two guys could be standing next to each other and not know it.”

Cinesite artists created simulated smoke based on reference from the practical explosions, added captured elements and blended it all into the live-action smoke.

Cinesite artists created jets flying over for the ‘show of force’ sequence, following Mendoza’s specific direction. To show overhead footage of combatants moving in the neighborhood, the crew used a drone flying 200 feet high and shot extras walking on a bluescreen laid out to match the street layout. “Initially, we were going to animate digital extras,” Stanley-Clamp says. “But Alex [Garland]

TOP: Thunderbolts*’ VFX team worked with production and special effects to do as many effects practically as possible, even when a CG solution seemed easier. Motion blur was a key component of creating the ‘ghost effect.’

(Image courtesy of Digital Domain and Marvel Studios)

BOTTOM: Wicked: For Good has special effects, practical sets and visual effects all working together.

(Photo: Giles Keyte. Courtesy of Universal Pictures)

TOP: Filmmakers shot as much in-camera as possible, yet there were still around 2,000 visual effects shots in Wicked: For Good (Image courtesy of Universal Pictures)

BOTTOM: In Mission: Impossible – Final Reckoning, Tom Cruise’s character, Ethan Hunt, navigates moving torpedoes while inside a partially flooded, rotating submarine, a giant gimbaled submersible built by special effects. (Image courtesy of Paramount Pictures)

said no. People would know they were CG. And he was right. Even with 20-pixel-high people, your brain can tell.”

Warfare could not have been made without visual effects. “The set would never have been big enough,” Stanley-Clamp says. “The explosions would probably have been okay, but they would have had to re-shoot many things. The bullets wouldn’t have landed in the right places. They wouldn’t have been allowed to fly the jets over in a ‘show of force.’ The visual effects supported the storyline throughout. He adds, “This isn’t a 3,000-shot show; the discipline was different. We had such a tight budget to work with and did not spend more than we were allowed. But what is there is so nicely crafted. I’ve never been on such a strong, collaborative team.”

TRON: ARES

At the end of the 2010 film Tron: Legacy, Sam Flynn escapes the Grid with Quorra, an isomorphic algorithm, a unique form of AI, and this digital character experiences her first sunrise in the real world. Neither Sam nor Quorra is listed in Tron: Ares, but the Grid has made the leap into the real world in the form of a highly sophisticated program named Ares, who has been sent on a dangerous mission. In other words, the game has entered our world – a world very much like Vancouver, where the film was shot.

“From day one, from the top down, everyone agreed to anchor the film in the real world,” said Production Visual Effects Supervisor David Seager, who works in ILM’s Vancouver studio. For example: “Our big Light Cycle chase in Vancouver in the middle of the night was with real stunt bikes.” The practical Light Cycle, though, was not powered; it was towed through the streets, with a stunt performer on the back, and later supplemented with CG. “The sequence is a mix and match with CG, but these are real streets, real cars,” Seager says. “We put Ares into that. If we cut to an all-CG shot, it’s hard to see the difference.”

In addition to filming in the real world, real-world sets helped

MIDDLE AND BOTTOM: The all-digital creatures in Jurassic World: Rebirth demanded even more attention to detail to ensure realism. ILM wouldn’t produce a piece of dinosaur animation without finding a specific live-action reference of real animals in that situation. (Image courtesy of Universal Pictures)

anchor the Grid’s digital world; there are multiple grids where digital characters and algorithms compete in games and disc wars. “In the Grid worlds, first we tried to match Legacy, then tried to plus it up,” Seager says. “Our Production Designer, Darren Gilford, was the Production Designer on Legacy. We carried that look into this film. Everything has a light line component to it.” As before, most characters wear round discs rimmed with light on their backs. Ares wears a triangular disc. Light trims all the suits and discs. “All the actors and stunt players had suits with LEDs built into them,” Seager says. “The suits were practical, made at Weta Workshop. Pit crews could race in to fix wiring, but in a small percentage of cases, when it would take too long, we’d fix it in CG.”

Light rims elements throughout the Grid: blue in ENCOM, the company that believes in users; red in the authoritarian Dillinger Grid. Ares, the Master Control Program of the Dillinger grid, is lit with red.

“Tron: Legacy has a shiny, wet look, and it felt like the middle of the night,” Seager says. “We have that in the Dillinger Grid. To make the Grids seem more violent, we literally put a grid that looks like a cage in the sky – blue in ENCOM, red in Dillinger.” In the digital world, as characters get hit, they break into CG voxel cubes that look like body parts. In the real world, Ares crumbles into digital dust. In the Grid, digital Ares can walk on walls; when Ares moves into the real world, he obeys real-world physics.

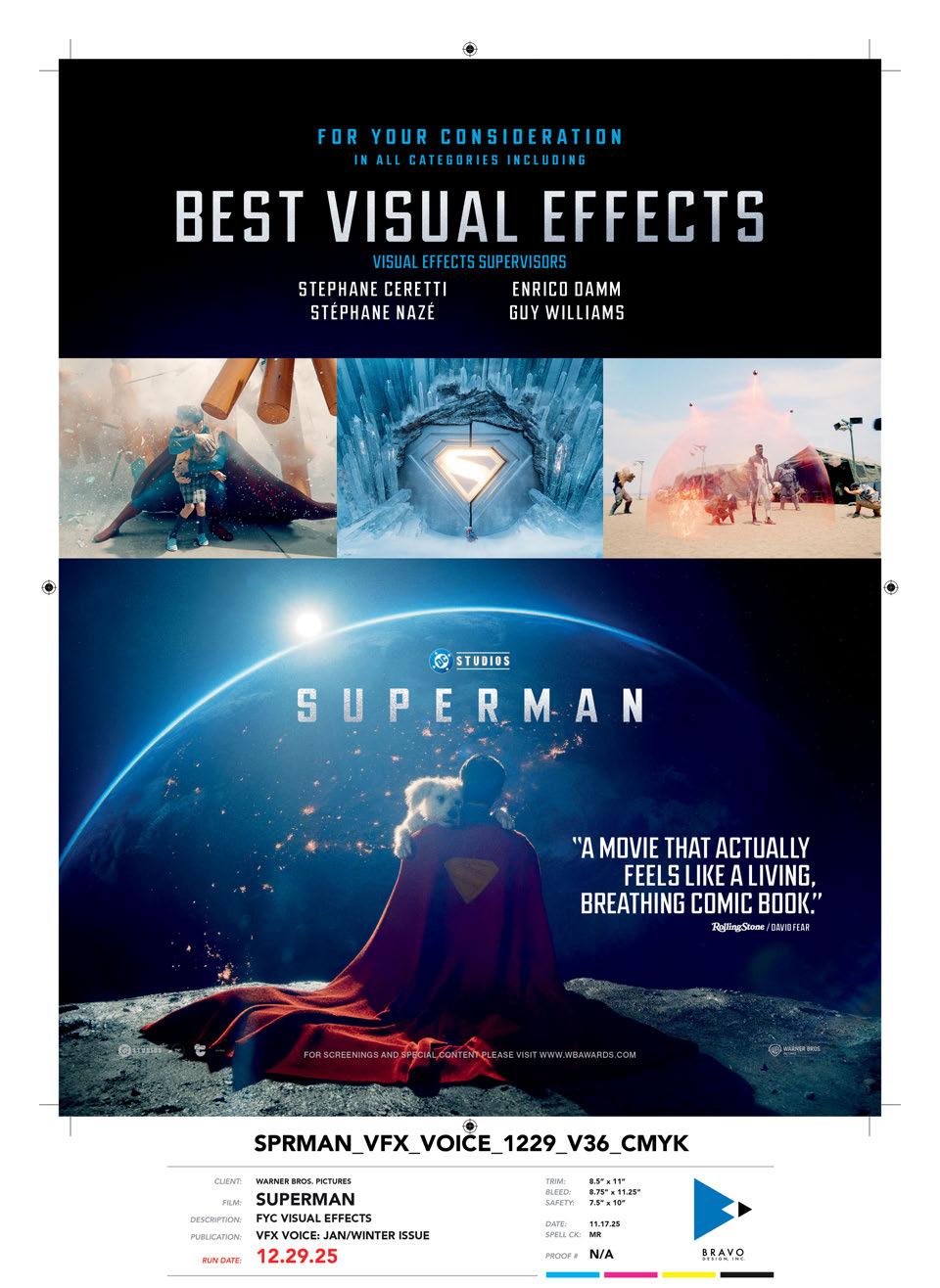

SUPERMAN

For Stephane Ceretti, Overall Visual Effects Supervisor, there

TOP: Mission: Impossible – Final Reckoning has 4,000 VFX shots, and as in previous MI films, actor Tom Cruise anchored everything, pushing the action, driving innovation. (Image courtesy of Paramount Pictures)

TOP TO BOTTOM: Director Gareth Edwards’s preference for shooting long, continuous action pieces wasn’t conducive to animatronics, so for the first time in Jurassic franchise history, the dinosaurs in Jurassic World: Rebirth were entirely CG. (Image courtesy of ILM and Universal Pictures)

Superman’s all-CG dog, Krypto, is based on director James Gunn’s dog, Ozu. Framestore artists created Krypto from Ozu and gave him a cape. (Image courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures)

The crew on Wicked: For Good used Unreal Engine to interact and iterate with production design, to look at first passes, conceptualize, and previs and postvis the intricate shots. (Image courtesy of Universal Pictures)

was as much work in the latest Superman as any visual effects supervisor might wish for. There’s Superman himself, lifting up entire buildings with one hand to rescue a passer-by, flying to the snowy, cold Fortress of Solitude to visit his holographic parents, battling the Kaiju, saving a baby from a flood in a Pocket Universe, having a moment with Lois while the Justice League battles a jellyfish outside the window. And that’s far from all. There’s much destruction. Buildings collapse. A giant chasm rifts through a city. There’s a river of matter. A portal to another world. A prison. Lois in a bubble. And a dog, a not very well-behaved dog, that likes to jump on people. Superman’s dog, Krypto, is always CG. “[Director James Gunn] gave us videos and pictures of his dog Ozu, a fastmoving dog with one ear that sticks up much of the time,” Ceretti says. “Framestore artists created our Krypto, gave him a cape, and replaced Ozu in one of James’ videos. When we showed it to him, he said, ‘That’s my dog. It’s not my dog. But it’s my dog.’”

In terms of other visual effects, there were three main environments. Framestore artists mastered the Fortress of Solitude sequences filmed in Svalbard, Norway, including the giant ice shards that forcefully emerge from the snow, and the robots and holographic parents inside. Legacy supplied the robots on set, some of which were later replaced in CG, particularly for the fight scenes. The holograms were another matter. “They needed to be visible from many different angles in the same shot,” Ceretti says. “Twelve takes with 12 camera moves. It would be too complicated to use five different motion control rigs shooting at the same time. I didn’t want to go full CG because we would have close-ups. So, I started looking around.” He found IR (Infinite-Realities), a U.K.-based company that does spatial capture, rendering real-time images 3D Gaussian splats, fuzzy, semi-transparent blobs, rather than sharp-edged geometry, to provide view-dependent rendering with reflections that move naturally with the view. “They filmed our actors with hundreds of cameras then gave us the data,” Ceretti says. “We could see the actors from every angle in beautiful detail

TOP: The entrance of the Fortress of Solitude consists of 6,000 crystals refracting light, making it a challenging asset to render for Superman. (Image courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures)

BOTTOM: Filmmakers almost doubled the density of smoke in the final cut of Warfare. Cinesite artists created simulated smoke based on reference from the practical explosions, added captured elements, and blended it all into the live-action smoke. (Image courtesy of DNA Films, A24 and Cinesite)

with reflections, do close-ups of the faces and wide shots. It was exactly what we needed.”

For the Metropolis environments, ILM artists handled sequences set early in the show, the final battles in the sky at the end, and all the digital destruction as buildings fall like dominoes into a rift. “The rift and the simulation of the buildings collapsing and reforming at the end was really tricky,” Ceretti says. The production crew filmed those sequences in Cleveland. But, to set the Metropolis stage, the ILM artists built a 3D city based on photos of New York City, integrated with pieces of Cleveland, using Production Designer Beth Mickle’s style guide. “We tried to avoid bluescreens as much as we could,” Ceretti says. “We wanted to base everything on real photography as much as possible. So, we created backdrops in pre-production that we could use as translights for views outside the Luther tower.”

For a tender moment between Superman and Lois, ILM used views of Metropolis outside the apartment window on a volume stage to project a fight between the Justice Gang and a jellyfish on an LED screen. “We used that as a light source for the scene,” Ceretti says. “They could feel what was going on outside, and we could frame it with the camera. It was the perfect way to do it.”

Weta FX managed sequences with the Justice Gang taking charge of the travel to, from and inside the weird Pocket Universe. Production Designer Beth Mickle helped Ceretti envision the otherworldly River Pi in the Pocket Universe. “When I read the script, I saw that James [Gunn] wrote next to the River of Pi, ‘I don’t quite know what that looks like,’” Ceretti says. “We suggested basing it on numbers, and Beth came up with the idea that

TOP TO BOTTOM: A second new Na’vi clan, the Windtraders (Tlalim), is introduced in Avatar: Fire and Ash along with their flying machines, Medusoids, unique Pandoran creatures, and giant floating jelly-fish-like airships that support woven structures propelled by harnessed stingraylike creatures called Windrays. (Image courtesy of 20th Century Studios)

On a practical level, the ‘return to basics’ VFX techniques used in making Thunderbolts* meant ditching bluescreens for set extensions to achieve a more natural tone – without using LED volumes. (Image courtesy of Digital Domain and Marvel Studios)

One of the most challenging sequences for visual effects in Wicked: For Good is when Glinda (Ariana Grande) sings in a room with mirrors, and both sides of the mirror – Glinda and her reflection – had to be shown. And it was all tied to a song, so the sequence had to be cut on cues. (Image courtesy of Universal Pictures)

differently sized cubes, each size representing a unit, would create the river flow.” On set, the special effects team filled a tank with small buoyant, translucent, deodorant plastic balls that Superman actor David Corenswet could try to “swim” through. Later, Weta FX artists rotoscoped the actor out, replaced the balls with digital cubes and added the interaction. They kept Corenswet’s face but sometimes replaced his body with a digital double to successfully jostle the digital cubes.

“We constantly moved between CG characters and actors in this film,” Ceretti says. “To suggest speed, we’d add wind to the hair and sometimes have to replace hair, and make the cape flap at the right speed to feel the wind. But I really tried to have the actors be physically there. As always, it’s a combination of real stuff, CG, digital doubles, and going from one to the other and back and forth all the time.”

THUNDERBOLTS*

“This film is the opposite of everything I’ve been asked to do in the last 10 or 15 years,” says Jake Morrison, Overall Visual Effects Supervisor on Thunderbolts*, whose 35 film credits include other Marvel films. “Most of the visual effects I do are about spectacle, world-building, planets and aliens,” he says. “Jake Schreier, the director of Thunderbolts*, had the exact opposite brief. He wanted it to feel as organic as possible, grounded, real.”

Thunderbolts*’ unconventional and at times dysfunctional team of antihero characters resonated with critics who hailed the Marvel Studios’ film as a “return to basics.” “Basics” reflects the approach taken for many visual effects techniques. For example, on a practical level, it meant ditching bluescreens for set extensions to achieve a more natural tone – and doing without LED volumes. “Any time we couldn’t afford to do a set extension, I asked the art department to build a plug in the right color for what will be in the movie,” Morrison says. “It took a minute for the team to understand, but it had an incredible ripple effect. You’d look at a monitor live on set and see a finished shot even though there would be set extensions later. It felt like a movie. The amazing thing was that we didn’t have to change skin tones and reflectance. I would say the set extension work was more real because it was additive, not subtractive.”

In that same vein, rather than filming in an LED volume, Morrison used a translight on set for a view out the penthouse in Stark Tower, which in this film has 270 degrees of glass windows wrapping it, a shiny marble floor and a shiny ceiling. “A team from ILM shot immensely high-detail stills of the MetLife building in New York to create an impressive panorama that we printed on a vinyl backing 180 feet long,” Morrison says. “With a huge light array behind the vinyl, the photometrics were correct. One of the guys walked on set and wobbled with vertigo.” Visual effects artists replaced the translight imagery in post, adding areas hidden by the actors standing in front of the vinyl when necessary. “But every reflection in the room was exactly right,” Morrison says. “It’s the same idea as an LED volume, but the color space differs. There’s nothing like the flexibility you get with LED volumes, but there’s something that feels genuinely organic when you backlight

TOP: For the biplane sequence at the end of Mission: Impossible – Final Reckoning, where Tom Cruise hangs onto the wing of a biplane while it performs aerobatics, a pilot in a green suit was flying the plane, with Cruise holding on. The VFX teams later removed the pilot and safety rigging. (Image courtesy of Paramount Pictures)

BOTTOM: Fewer than 10% of the shots in the final Essex boat sequence in Jurassic World: Rebirth feature any real ocean water. With few exceptions, entire sequences were filmed on dry land in Malta. (Image courtesy of ILM and Universal Pictures)

photography at the right exposure.”

Throughout the shoot, Morrison worked with production and special effects to have them do as many effects practically as possible, even when a CG solution might have seemed easier. Offering CG as a safety net in case the practical effects didn’t work helped convince them. “I was able to give Jake [Schreier] shots of the lab sequence, and he couldn’t tell which were plates and which were CG,” Morrison says. “You can only do that if you commit production to build it for real. Then, you can scan that and have it as reference, and you can do stuff with it. We can shake it. Every glass vial rattling and falling, the ceiling cracking, all looks real because we pushed for it to be real. It all becomes subjective if you don’t have that reference on a per-frame basis.”

For a driving sequence, he convinced the crew to take a “’50s” approach rather than work in air-conditioned bliss in an LED volume. Instead, they filmed in the Utah heat. “Everyone knows there’s a crutch,” Morrison says. “It’s easier to change the LED walls. But something old school brings a level of reality.” For motorbike work in that sequence, rather than painting the stunt biker’s large safety helmet blue or green to replace it with CG later, Morrison had the helmet painted the color of the actor’s skin and glued a wig on it. “People on the show thought I was kinda nuts,” Morrison says. “It looked so funny, we didn’t have a dry eye in the house. But we shrank down the oversized helmet and hair by 25% and had an in-camera shot. Just because you could go all CG doesn’t mean you should. You should use VFX for things that need it, not for things that could be practical.”

Even when characters in the film transform into a void, Morrison looked for practical possibilities. “Jake and Kevin [Producer Kevin Feige] would challenge me with ‘How would you do this character if you didn’t have CG?’” Morrison says. “We came up with three types of voiding, each of which could have been done with traditional techniques.” For one, they used what Morrison calls a simple effect that is difficult to pull off: They shot actor Lewis Pullman, rotoscoped his silhouette, zeroed it back until it looked like a hole in the negative, then had each frame show just enough detail to be scary. For the second, they projected shadows out from a character as if it were a light source, using aerial plates shot in New York. For the third, they zapped characters out of the frame and splatted their shadows onto the ground in the direction from which they’ve been zapped. “The effect we created is very old school visually, but we used all modern techniques. It’s really good to be put in a box sometimes,” he adds. “It’s an exercise in restraint. Sometimes, the playground is a little bit too big. Being able to unleash that creativity is fun. If people like the work we did, it’s because we tried so hard for you not to notice it.”

MISSION: IMPOSSIBLE – THE FINAL RECKONING

Visual Effects Supervisor Alex Wuttke received a Best Visual Effects Oscar nomination and numerous other awards in 2024 for Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One. The effects in this year’s follow-up film, Mission: Impossible – The Final Reckoning, could provide the same accolades. Production Visual Effects Supervisor Wuttke, who is based in ILM’s London studio,

says, “We were successful last time. So, we took what worked and extended it. We wanted to take it to the next level.” This film has 4,000 VFX shots, and as in previous MI films, actor Tom Cruise anchored everything. “He pushed himself,” Wuttke says. “We’re his enablers. His desire to up the ante drives the rest of us to be innovative.”

Two big sequences illustrate the tight interplay between special effects and visual effects: the submarine and biplane sequences. For both, the crews looked for ways to help Cruise perform the scenes realistically. For example, Cruise’s character, Ethan Hunt, must navigate around moving torpedoes while inside a partially flooded, rotating submarine. Special effects built a giant gimbaled submersible that Cruise drove inside in a deep dive tank. The Third Floor’s previs team mapped out the action. The actions and the range of motion dictated the rig that was built. All the water inside the submarine is real. “There were so many moving parts,” Wuttke says. “We had to drop torpedoes around Tom’s performance. Sometimes that was not possible within the chaos of Tom being inside a washing machine. We knew we would need repeat passes.” When it wasn’t safe practically, CG torpedoes hit with the right impact, and water simulations sold those shots. Even when the action was real, the water, filtered for health and safety, needed digital enhancements. CG particulate, bubbles and so forth added reality, scale and scope.

“One of my favorite sequences is the biplane sequence at the end that we shot in Africa,” Wuttke says. In this sequence, Cruise hangs onto the wing of a biplane while it performs aerobatics. “It was so complicated working out how we would execute those sequences, “Wuttke says, “but it was hugely rewarding. The visual effects work is seamless, and Tom was astonishing. We would have a pilot in a green suit flying the plane, and Tom would be holding on.” The VFX teams removed the pilot and the safety rigging. They also replaced backgrounds for pick-up shots – gimbal work filmed in the U.K. – with the African environment.

Several VFX studios worked on the film, including Bolt, Rodeo FX, Lola, MPC and ILM. “Our chief partner was ILM. They were amazing,” Wuttke says. “Jeff Sutherland, Visual Effects Supervisor, was incredible. Their Arctic work with the blizzard was phenomenal. We were worried about the sequence when Hunt confronts the entity, but we were very pleased with the CG work created jointly by ILM and MPC. Hats off to Kirstin Hall, who picked up MPC’s work and finished it at another house without missing a beat.”

Framestore artists mastered the Fortress of Solitude sequences for Superman filmed in Svalbard, Norway, including the giant ice shards that forcefully emerge from the snow, and the robots and holographic parents inside. (Image courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures)

To boost realism and add fidelity to the creature simulations for Jurassic World: Rebirth, a new procedural deformer applied high-resolution dynamic skin-wrinkling on muscle and fatty tissue simulations, removing previous limitations of 3D meshes. (Image courtesy of ILM and Universal Pictures)

“We’ve talked about the big sequences, but we had close to 4,000 shots,” Wuttke adds. “A lot of work might not be noticed. We amassed a huge amount of material.”

JURASSIC WORLD: REBIRTH

ILM’s David Vickery, Production Visual Effects Supervisor on Jurassic World: Rebirth, received two VES Award nominations for 2023’s Jurassic World: Dominion Rebirth was more challenging. “This film presented us with so many new technical and creative challenges that it’s hard to compare from a complexity standpoint to any film I’ve worked on before,” he says. From pocket-sized

TOP TO BOTTOM: Lo’ak, narrator of Avatar: Fire and Ash, surfing his “spirit brother,” the whale-like Tulkun Payakun. The third film dives deep into tulkun culture. (Image courtesy of 20th Century Studios)

TOP TO BOTTOM: The Light Cycle chase in Tron: Ares took place in Vancouver in the middle of the night with stunt bikes towed through the streets with a stunt performer on the back, and later supplemented with CG. (Image courtesy of Disney Enterprises)

Payakan’s role is elevated from his initial appearance in Avatar: The Way of Water to a major “soldier” in the Na’vi and human alliance against the RDA. (Image courtesy of 20th Century Studios)

Cinesite artists created jets flying over for the ‘show of force’ sequence in Warfare. The fighter jet in the sequences was entirely CG. (Image courtesy of DNA Films, A24 and Cinesite)

dinosaurs to T. rex, Mosasaur, Spinosaur, Mutadon, Titanosaur, Quetzalcoatlus dinosaurs and more. Water in rapids, water in open ocean, water on dinosaurs, boats in water, dinosaurs in water, people in water, white water, waves, splashes. Capuchin monkeys. Inflatable raft. Digital limbs. Jungles. Titanosaur plains. Filming in wildly remote locations. All within a short production schedule – 14 months from the first meetings with director Gareth Edwards to final delivery.

ILM’s work on the dinosaurs was an example of its ability to deliver the director’s vision. Edwards’s shooting preference – long, continuous action pieces – isn’t conducive to animatronics. “For the first time, we didn’t match the performance of practical animatronics,” Vickery says. “Gareth wanted our dinosaurs to be entirely digital and behave like real animals, not just turn up on screen, hit a mark and roar. We all agreed never to produce a piece of dinosaur animation without finding specific live-action reference of real animals in that situation. Our animators at ILM stuck to this plan and it worked beautifully.” Then, given concept approval for the dinosaurs, artists used the new tools to manipulate the creatures’ soft tissue – skin folds, neck fat, cartilage and so forth. To boost realism and add fidelity to the creature simulations, a new procedural deformer that puts high-resolution dynamic skin-wrinkling on muscle and fatty tissue simulations, removing the previous limitations of 3D meshes. The output, a per-frame point cloud with normal-based displacement information, could be read back into look development files.

“We worked on any part of the creature that wouldn’t have been preserved in the fossil records,” Vickery says. “Things that could give our dinosaurs unique personalities, yet wouldn’t contradict current scientific understanding. The new tools gave us an incredible level of detail in our creature simulations and brought a physical presence and level of realism to the dinosaurs that the franchise hadn’t seen yet.” That same level of realism and the opportunity to create new tools extended to the CG water. “There was a huge focus on realism for all the water in Rebirth,” Vickery says. “It was our main concern from the start and one of our biggest technical and creative challenges.” CG Supervisor Miguel Perez Senent, working with Lead Digital Artist Stian Halvorsen, developed a broad suite of tools, including a new end-to-end water effects pipeline based on a wrapper around Houdini’s FLIP solver with custom additions for efficiency and realism. Low-res sims defined the overall behavior of a body of water and guided higher resolution FLIP sims to enhance details where collisions and interactions took place. A mesh-based emission from the resulting water surface provided fidelity in secondary splashes from areas churned up in the main simulation.

“The biggest innovation was a new whitewater solver that handled the complex behavior of splashes,” Vickery says. “The details in these simulations are second to none. You can see whitewater runoff on the dinosaurs fall back down and trigger tertiary splashes when hitting the water surface.” Fewer than 10% of the shots in the final Essex boat sequence feature any real ocean water, and with few exceptions, entire sequences were filmed on dry land in Malta. ILM artists extended the partial build of the boat, created

TO

(Image courtesy of ILM and Universal Pictures)

Animals articulate their thoughts in Wicked: For Good, and the audience hears their experiences, raising the level of empathy. (Image courtesy of Universal Pictures)

Sparks were treated as 3D assets, which allowed them to be better integrated into shots as interactive light for Thunderbolts* (Image courtesy of Digital Domain and Marvel Studios)

the ocean surface, simulated the boat engines, the whitewater, the wake, crashing bow waves, sea spray, mist, and integrated the Mosasaur and Spinosaur dinosaurs within all that.

“I pushed production to shoot on a real boat at sea, but noise from the boat’s diesel engines made recording sound impossible. In the end, with consistent light on the boat and cast a priority, they used a water tank alongside the ocean in Malta for most of the shots. SFX Supervisor Neil Corbould, VES covered the real Essex with IMU’s (internal measurement units) and recorded how it performed in varying ocean conditions. Then, that data drove a partial replica of the Essex he built and put on a gimbal. “We never filled the Essex tank with water because that made the shooting prohibitively slow,” Vickery says. Similarly, the T. rex rapids were largely CG. “It’s a flawlessly executed, fully CG environment based on rocky rivers we found around the world,” Vickery says. “We replaced everything shot in-camera, except a small section of rocks that the cast grab onto at the end. The inflatable raft is CG. There was complex ground and foliage interaction with the T. rex; shots above and below the water surface, and beautifully choreographed T. rex animation.”

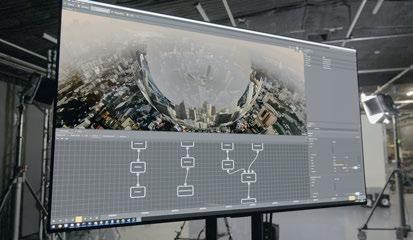

Another invention, a custom VCam system, allowed Edwards and Vickery to shoot real-time previs using Gaussian splats of their remote Thailand locations. Vickery and VFX Producer Carlos Ciudad shot 360-degree footage using an Insta360 camera during tech scouts. Proof Inc. created Gaussian splats from the footage, and Production Designer James Clyne built virtual replicas of the sets inside the Gaussian splats. Then, Proof used Unreal Engine to build a virtual camera with the 35mm anamorphic lens package for the splat scenes and motion capture of stand-ins that allowed Vickery and Edwards to block out and direct action sequences.

ILM handled most of the work on Rebirth’s 1,515 VFX shots with an assist from Important Looking Pirates and Midas. Proof did previs and postvis.

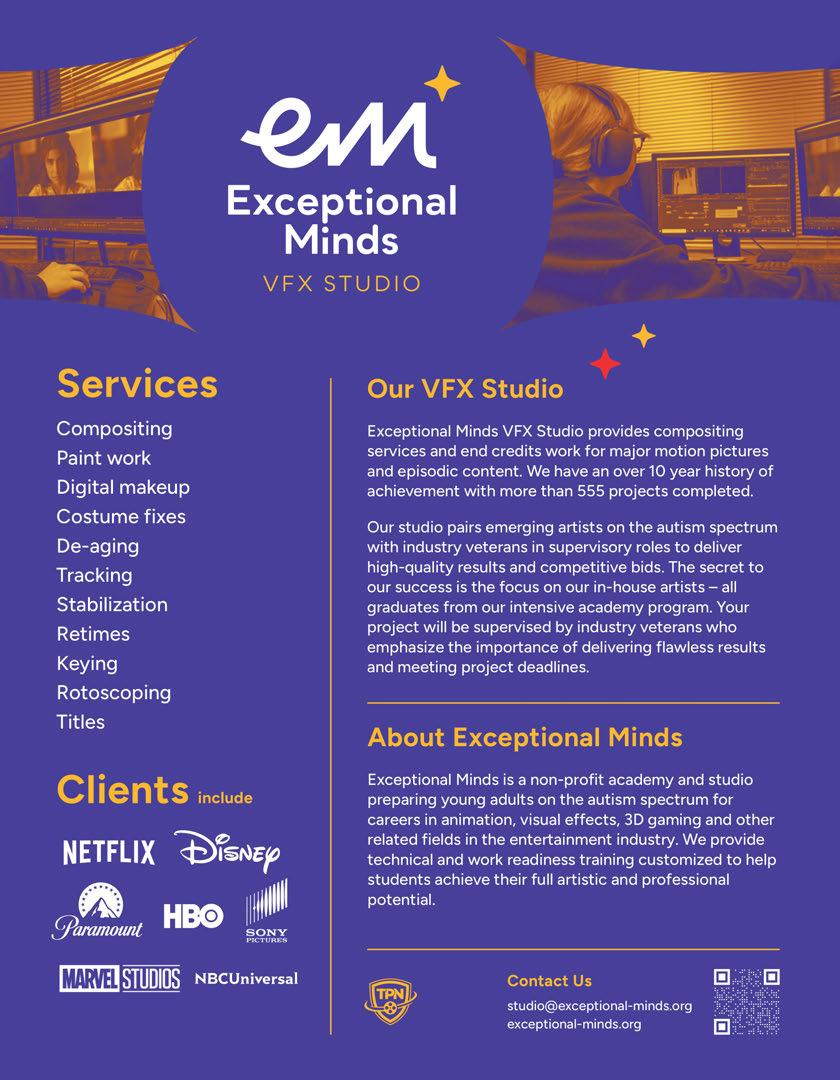

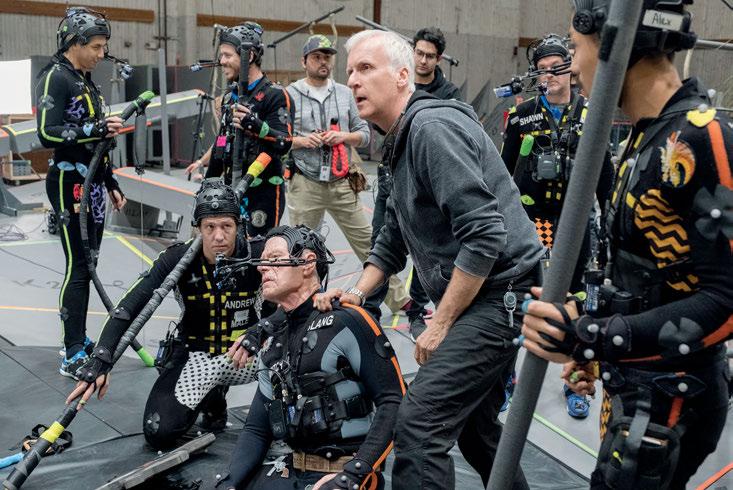

AVATAR: FIRE AND ASH

Much has been written about the groundbreaking, award-winning visual effects and production techniques used to help craft James Cameron’s Avatar (2009) and Avatar: The Way of Water (2022). Indeed, both films earned Best Visual Effects Oscars for the supervisors working on the films, giving Senior Visual Effects Supervisor Joe Letteri, VES of Weta FX his fourth and fifth Oscars. Expect to hear about new groundbreaking tools and techniques for the latest film, Avatar: Fire and Ash, but this time, more emphasis is on artistry than technical breakthroughs.

“This film is a lot more about the creativity,” Letteri says, “about getting to work with the tools we’ve built. We’re not trying to guess how to do something with three months to go. We’ve front-loaded most of the R&D.” He adds, “A lot of times you build the tools, make the movie, then you’re done. You don’t get to go back and say, ‘Gee, I wish I knew then what I know now.’ This film gave us the chance to do that because the films are back-to-back. We look at the second and third films as one continuous run.” For example, much of the live-action motion capture for characters in Fire and Ash was accomplished at the same time as capture for the second

TOP

BOTTOM: ILM handled most of the work on Jurassic World: Rebirth’s 1,515 VFX shots with assists from Important Looking Pirates and Midas. Proof Inc. did previs and postvis.

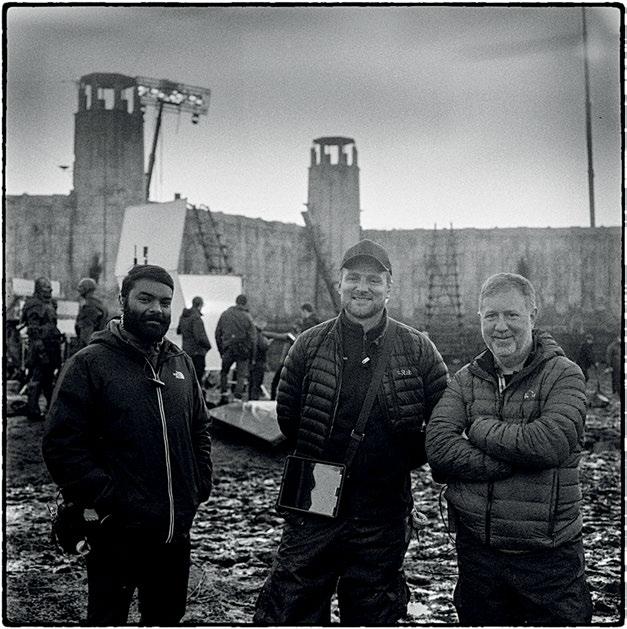

TOP TO BOTTOM: Unfolding in real time, Warfare was shot over a period of 28 days at Bovingdon Airfield in Hertfordshire, U.K. (Image courtesy of DNA Films, A24 and Cinesite)

Since Avatar: The Way of Water, animators have been able to manipulate faces with a neural-network-based system, giving characters’ faces an extra level of realism, unified by underlying motion capture. (Image courtesy of 20th Century Studios)

As complicated as it was to work out the execution of the biplane sequences in Mission: Impossible – Final Reckoning, the visual effects work was seamless, driven by Cruise’s desire to the push stunts to the limit. (Image courtesy of Paramount Pictures)

Avatar, using techniques pioneered on the first film. “We didn’t shoot anything new since the last film,” Letteri says. However, Fire and Ash introduces a new clan, the Ash people, and a new antagonist, Varang, leader of the Ash people. They, particularly she, provided an opportunity for the studio to further refine its animation techniques. “We have a great new set of characters,” Letteri says. “They allowed all kinds of new emotional paths. Varang [Oona Chaplin] is a bit of a show-off; I really enjoyed scenes with her.”

On prior films, animators used a FACS system with blend-shaped models. Since Way of Water, they have been able to manipulate faces with a new neural-network-based system. “We wanted the face to respond in a plausible way, given different inputs,” Letteri says. “Before, animators would move one part of the face, then move another, and kind of ratchet all the pieces together to make it work. The capture underneath helps unify it, but they have to fine-tune that last level of realism. With the neural network, pulling on one side of the face will affect he other side of the face because the network spans throughout the face. They get a complementary action. The left eyelid might move if they move the right corner of the mouth. It gives the animators an extra level of complexity. It took getting used to because it’s different, but it’s how a face behaves. Once the animators became comfortable with the system, it gave them more time to be creative. The system was easier to work with.”

As for the fire of Fire and Ash, Letteri says, “We’ve done fire before, but not as much as we had on this film. So that was a big focus. Simulations are hard to do, but we do them the old-fashioned way – simulating everything together so the forces are coupled, but breaking layers for rendering to incorporate pieces of geometry. As for the rest, the focus was, ‘We know how to do this. How can we make it better?’”

In addition to the Ash People (Mangkwan), a second new Na’vi clan, the Windtraders (Tlalim), is introduced for the first time –along with their flying machines. Windtraders fly using Medusoids, unique Pandoran creatures, and giant floating jelly-fish-like airships that support woven structures propelled by harnessed stingray-like creatures called Windrays. “The Medusoids were in Jim’s [Cameron] original treatment, and I was bummed when he cut them from the first film,” Letteri says. “But here they are. They’re pretty spectacular. Everything is connected to everything else. We captured parts of it, so we had to anchor that to our craft floating through the air. It was great to work out all the details and set it flying. Jim shoots in native 3D, so when you look at it in stereo, you’ll really be up in the air with these giant, essentially gas-filled creatures. It’s very three-dimensional.”

The crew also began refining their proprietary renderer, Manuka. “We used a neural network for denoising on the second film and realized that was okay, but we lost too much information,” Letteri says. “It really belongs inside the renderer, not after the render. So, we started moving those pieces into Manuka, and it’s starting to pay off. There will be more improvements to come.”

Letteri observes, “This film is all about the characters and the people behind them. One of the secrets of this business is that with all the computers and automation, there’s still a fair amount of handwork that goes into these films. A lot of work by artists is the key to it, which is great because what else would we be doing?”

WHAT IT TAKES FOR SMALLER VFX STUDIOS TO SURVIVE – AND THRIVE

By TREVOR HOGG

Juggernauts like DNEG and Framestore are not impervious to the volatility of the visual effects marketplace, as demonstrated by the dissolution of Technicolor, while mainstays like ILM, Scanline VFX, Pixomondo and Sony Pictures Imageworks have become the property of streamers and Hollywood studios. Despite the perpetual financial uncertainty, there is one constant fact that remains, which is that digital augmentation has become a fundamental part of filmmaking and the ambitions of each new generation of cinematic talent keep pushing the boundaries of technology to achieve their growing creative ambitions. So, how do the smaller visual effects companies find prosperity within this environment where budgets and schedules are getting tighter and more demanding? The answer is not singular but as multifaceted as crafting a believable photoreal CG image.

TOP: Being involved in different industries causes a cross-pollination of ideas and techniques for the Territory Group, which contributed effects to Atlas (2024). (Image courtesy of Territory Group and Netflix)

OPPOSITE TOP TO BOTTOM: Tippett Studio has become part of Phantom Media Group, which includes Phantom Digital Effects, Milk VFX and Lola Post. (Image courtesy of Tippett Studio, Disney+ and Lucasfilm Ltd.)

One of the great joys for Tippett Studio is being tasked with creating monsters, as it did for Star Wars: Skeleton Crew. (Image courtesy of Tippett Studio, Disney+ and Lucasfilm Ltd.)

Tippett Studio, which worked on Star Wars: Skeleton Crew, believes visual effects are an ever-evolving blend of technology and artistry. (Image courtesy of Tippett Studio, Disney+ and Lucasfilm Ltd.)

BUF has been around for 40 years with the main facility located in Paris and a second one established 10 years ago in Montreal; their specialty has remained the same, which is conceptualizing specific designs for film and television productions. “They always come to us saying, ‘We want something we’ve never seen before,’” states Olivier Cauwet, VFX Supervisor at BUF. “When we were working on American and Luc Besson movies, we had 300 employees; it was too much and changed the spirit of BUF. We wanted to have fewer artists, so now we’re around 140, which allows us to preserve our philosophy and the spirit of how we work. We’re not growing too much because with the [current] market, it’s dangerous to go too fast because you can lose everything.” Project demands have greatly increased. Cauwet says, “My first movie was as an artist on Fight Club, and we did 11 shots in six months. Now we’re doing more than 500 shots in three months. There’s a huge gap, and the technology accounts a lot for that. We are working on proprietary software, so we’re not using Nuke or Maya. We have an

R&D department which releases software every three months for us. The tools are much more efficient now, especially for tracking and rotoscoping. This allows us more time to be creative with shots. When I manage a team, I only have generalists with me, and they’re working on all the shots, doing matchmoving, rotoscoping, modeling, texturing, lighting, compositing and rendering. Generalists are more personally involved in the process, which means they understand the sequence and story. They’re not only doing a task, but also their shots.”

Commercials are the core business for London-based Freefolk, which subsequently established a film and episodic department. “There are certain companies that specialize in one area or another, but we decided to have feet in both camps,” remarks Paul Wright, COO at Freefolk. “Commercials work in a far looser fashion, not necessarily requiring the dedicated tech pipeline that film or episodic requires. We developed a pipeline to go with film and episodic that has effectively been adopted company wide.” Diversification is critical. Wright notes, “You have to cast your net wider today than you might have needed to a long time ago. At the same time, you have to manage the delivery of all those and maintain the quality level that you would like to be able to deliver.” The visual effects industry has changed. “I remember when the industry was hardware-led and you couldn’t get your hands on the kit,” notes Meg Guidon, Executive Producer, Film & Episodic at Freefolk. “Things have broadened out tremendously, as well as what younger artists can offer. You need to be open to the talent that comes through your door, and we’ve got this expanding network of people we enjoy working with. If we see that they have a talent for motion graphics, our response isn’t, ‘We don’t really do motion graphics.’ We take it on and do it now.”

Headquartered in Culver City, California, Wylie Co. specializes

“When I manage a team, I only have generalists with me, and they’re working on all the shots, doing matchmoving, rotoscoping, modeling, texturing, lighting, compositing and rendering. Generalists are more personally involved in the process, which means they understand the sequence and story. They’re not only doing a task, but their shots.”

—Olivier Cauwet. VFX Supervisor, BUF

in previs, postvis and visual effects for film and episodic. “Visual effects are so nuanced and complicated, but you’re still serving the subjective thing,” states Jake Maymudes, CEO & COO at Wylie Co. “You try to make it to order and hand it to the client. Then they can say, ‘It’s too blue or dark or light, change the animation.’ A lot of times, the company has to incur the costs of this very subjective thing they’re selling. It’s complicated and hard. In 2024, we lost money for the first time in 10 years, but this year we’re making money.” The actors’ strike had a substantial impact. Maymudes remarks, “It was a real hit to the industry. It’s still finding its feet. It was a big reset in the content. As far as visual effects is concerned, it could have been the combination of after the strike and Marvel at the same time realizing they made too [many films] because their slate has come way down.” AI and machine learning have become significant disrupters. “If you really dig in, the outcome could be, you film an entire feature film on an iPhone or something really small and run it through an AI post process to give it that epic Hollywood look and feel.” There is no desire to focus on one aspect of visual effects. Maymudes says, “I’ve never thought that specializing was a good idea. which is why we do everything, even though we’re small. Even with the emergence of AI, my personal opinion is, specializing isn’t a good business model, because ultimately, you’re going to have competition that is going to do it just as good as you, and it’s going to be negligent. If you’re a working group of artists who are capable of doing great work in a variety of different ways, that’s what you should sell. Do it all. We use machine learning and AI in all sorts of ways. If you go in and specialize in machine learning face replacements or deepfakes, or even AI deepfakes, there could be a startup that you haven’t heard of yet that pops up

TOP AND BOTTOM: Over the past 40 years, BUF has specialized in specific designs for film and television productions such as 3 Body Problem. (Images courtesy of BUF and Netflix)

next week and does that in a click of a button, essentially making your whole process obsolete.”

Straddling the world of visual effects and industrial design is the Territory Group, which originated in London. “We had that moment where everyone wasn’t looking for a new design studio, visual effects shop or digital agency,” recalls David Sheldon-Hicks, Founder of Territory Group. “We picked off niches in individual areas because we needed to find a way to thread between that, so it was the new things that were coming through. There were lots of freelancers working on on-set graphics. However, at the time, there were few small shops dedicated to on-set graphics that were doing it at scale with a robust structure behind them. Then, was anyone taking on-set graphics and applying it into post? There were post houses doing it, but I don’t know if they came from a design background.” Different industries cross-pollinate one another. Sheldon-Hicks says, “User interfaces and holograms in film feel connected to what’s happening in the automotive industry. Because we’ve been working in computer games, actually longer than films, games love to look at the film world and understand how they do what they do and then apply it in their own domain. Equally, the technology knowledge that we got from working in game engine for the last 15 years, not only has it been interesting in terms of virtual production, but also in terms of all the in-car experiences now built out in Unity or Unreal Engine; this is because they give you that next level of three-dimensional data and imagery that is real-time, that can be codified and powered through LiDAR scans or volumetric sensors. There’s this opportunity to use technologies from other fields and bring them across to other industries. We really enjoy that.”

TOP: PFX contributed effects to Locked (2025). PFX believes in building a solid studio in each country, which has been achieved mostly through the acquisition of local companies. (Image courtesy of PFX and Paramount Pictures)

BOTTOM : Spanning Central Europe is PFX, a full-service post-production studio that started off as a boutique studio in Prague and currently works on major studio projects such as Napoleon. (Image courtesy of PFX and Apple TV).

Global creative studio Tendril, based in Toronto, uses design, animation and technology to produce innovative stories and branding. “Nothing that I’ve done in the past 20 years would I ever have anticipated or stepped toward intentionally,” notes Chris Bahry, Co-Founder and CCO of Tendril. “Either you run toward the work or the work runs toward you. On the side of our building, it says ‘Pure Signal,’ and we had a muralist do it typographically as a mural. It’s part of this phrase, ‘Put out a pure signal so the right people can find you.’ That’s our mantra: If you’re putting out the right signal in the form of the work you’re putting out, it’s going to attract the people you want to work with and probably the kinds of work you’re seeking to do.” The work falls on the boutique end of the spectrum. “Sometimes we have projects that are bigger and require a larger team, but they are tiny compared to the ones you have in a large visual effects facility. I’ve always thought of Tendril being akin to ILM’s Rebel [Mac] Unit led by John Knoll. They wanted an agile process based around artists who were generalists and could take a shot from a concept, then design, develop, light and render it, and take it across the finish line. Whereas, in a scalable pipeline, normally it gets into a specialist workflow where it’s like an assembly line. Sometimes, certain problems are hard to solve in a linear, scaled-up specialist pipeline like that because it’s built to do particular things. The way Tendril is built is to be able to adapt and solve unique problems at a much faster cadence. Our project cycles tend to be about eight weeks, or we’ll sometimes only have two weeks to figure out something.”

Spanning Central Europe is PFX, a full-service post-production studio that started as a boutique studio in Prague. “In the beginning, we were an enthusiastic group of guys who wanted to be part of the industry and work on a nice movie,” recalls Lukas Keclik, Producer and Partner at PFX. “Little by little, through hard work, investing all of our money and using every contact, we experienced an evolution.” Subsidies are a driving force as to where the work gets sent, leading to additional PFX facilities being

TOP TWO: BUF, which led effects for Eiffel (2021), does not believe in growing too much or too fast, as it undermines the spirit and philosophy of the company based in Paris and Montreal. (Images courtesy of BUF)

BOTTOM TWO: Visual effects can be deeply nuanced and complicated but still subjective in nature, which Wylie Co. has to keep in mind when dealing with clients like director David Fincher for The Killer (2023). (Images courtesy Wylie Co. and Netflix)

TOP TO BOTTOM: Dune: Prophecy benefited from the knowledge gained in graphic design by the Territory Group. (Image courtesy of Territory Group and HBO)

Holograms have become a specialty of the Territory Group, as seen in Dune: Part Two (Image courtesy of Territory Group and Warner Bros. Pictures)

Tendril believes in using design, animation and technology to produce innovative branding and stories such as American Gods (2017). (Image courtesy of Tendril and STARZ)

Tendril believes that putting out good work will attract interesting collaborators and intriguing projects. (Image courtesy of Tendril)

established in Slovakia, Poland, Germany, Austria and Italy. “A couple of years back, we realized that the company wasn’t small anymore, but not big enough. We started to feel this pressure of subsidies becoming more important. We had 150 people, so it wasn’t a boutique studio anymore, while the subsidies in the Czech Republic were not competitive enough. However, we didn’t want to be a big corporate studio. Based on our experiences and where we felt the industry was heading, the decision was made to be in multiple locations, ideally connected with one pipeline. We didn’t want to do a business model of having a headquarters and establishing satellite studios. We want to build a solid studio with a local presence and a supervisor in each branch with a production team. The first country was Slovakia, which offered a subsidy of 33%, and we built a studio from scratch. It took a year to establish a team and integrate them, which took too much time away from us having contact with our clients and team. Then we decided it would probably be better to go the acquisition route.”

Originating in Gothenburg and establishing an operation in Los Angeles, Haymaker VFX is an independent visual effects company that does films, episodic and commercials. “Everything in the industry is relationship-based and those relationships drive the type of work,” observes Leslie Sorrentino, Executive Producer at Haymaker VFX. “You’re seeing agencies pulling editorial and coloring in-house, but not heavy CG. Like animation, you’ve got a bandwidth of clients wanting more of this heavy lifting. Hence, the new Superman. We don’t want to see everything with the kitchen sink in it, but there are set extensions and period pieces. Also, we are the house of record for Polestar in Europe; that relationship gives me a lot of service stuff I can do, like putting cars in environments. On general visual effects marketing and what we’re doing, size does matter, and we have to grow exponentially. It is also compounded by the fact that you’ve seen the contraction of DNEG and closing of Technicolor. We started out doing Season 2 of Warrior Nun, working in conjunction with MCS Canada; that drove us more into the streaming services, which is where the business is at the moment.”

The streamers are going through a readjustment period in regard to demand for content. Sorrentino remarks, “The streaming services oversaturated the market in order to position themselves and, because of that, the content level became ridiculous. There is a cost we paid for that. I firmly believe that there will be winners and losers of the streaming environment. But there will still be fresh content with streamers developing things like Fallout, which was a gaming thing to begin with, or these other series that you’re seeing, like This Is Us. Those are going to continue to grow and be a force in our environment to provide work, but nowhere near the level where it expanded initially. It was much too overblown. Hence the contraction now. That will still be a prominent source of revenue and work. Sports advertising will continue to grow, and experiential verticals are going to be an important part of visual effects growth integrated with AI.”

Embracing AI and machine learning is Toronto-based MARZ, which developed Vanity AI to process large volumes of high-end 2D aging, de-aging, cosmetic and prosthetic fixes, as well as

TOP TO BOTTOM: PFX worked on Winning Time. Being a midsize visual effects company is problematic: PFX was neither small nor big enough to survive, so the decision was made to expand. (Image courtesy of PFX and HBO)

MARZ has worked on shows such as The Studio and has embraced technology as a means to level the playing field. (Image courtesy of MARZ and Apple TV)

Straddling the worlds of visual effects and industrial design is the Territory Group, which provides everything from user interfaces for cars and movies such as Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania (2023). (Image courtesy of Territory Group and Marvel Studios)

The work for Tendril falls on the boutique end of the spectrum. (Image courtesy of Tendril)

LipDub AI, a realistic AI lip sync video generator. “It’s a niche-to-win strategy,” states Jonathan Bronfman, CEO at MARZ. “It’s still difficult, but going out there right now as any run-of-the-mill visual effects provider, you’re using the same tech and pool of artists; there’s no differentiation. It’s not a compelling pitch to a given project to say, ‘We’re MARZ and do great visual effects. We will give you a good price.’ Everyone is saying that. What I’m finding is that the productions are finding more comfort going with the bigger shops. A lot of these shops are owned by studios: Pixomondo and Sony, Scanline VFX and Netflix, ILM and Disney. Those studios are incentivized to keep their own companies fed before feeding other companies. Historically, we were going after big shows like Marvel. The shows would typically go to ILM or Wētā FX, and ask, ‘How much can you take on?’ MARZ was a great alternative to deliver not the final sequence of an Avengers movie but a fight sequence within it. Now those big shops are taking all the work with no spillover.” Technology is the means to level the playing field. Bronfman states, “We’ve placed ourselves in the arena of AI and machine learning. Not only are we developing proprietary machine learning tools, but we’re also wrapping around some open-source projects. Some people resent that, because they think it’s taking away jobs. It’s not taking away jobs but opening up new jobs and opportunities that otherwise wouldn’t exist. But even more important is the differentiation. We have to, otherwise what’s our competitive edge?”

Originally centered around stop motion animation, Tippett Studio has gained a reputation for creating digital creatures. “Visual effects is an ever-evolving blend of technology and artistry,” notes Christina Wise, Vice President Business Development at Tippett Studio. “At Tippett, we stay at the forefront of innovation. We combine legacy techniques like stop-motion animation with cutting-edge tools, including AI, to push creative boundaries while meeting production demands. Expanding our clientele starts with the strength of our work and the legacy behind it. While relationships are key in this industry, we often hear from first-time clients drawn in by their admiration for Phil Tippett’s work and the reputation we’ve built over decades. People might not know the Tippett name right away, but chances are, they’ve grown up watching our work.”

Tippett Studio has become part of Phantom Media Group, which also includes PhantomFX, Spectre Post, Milk VFX and Lola Post. “As part of PMG, we think of ourselves as a new chain of interdependent studios, backed by the appeal of tax incentives and a global presence. Our outreach strategy combines inbound interest with traditional efforts: some clients find us, others we actively pursue. We’re especially seeing momentum from legacy and fan-driven projects, as well as a new wave of younger creators who are passionate about stop motion and anime aesthetics.” Diversification is paramount. Wise notes, “Tippett’s expansive footprint in China includes high-profile fly rides and immersive park content, which continue to perform strongly. Most recently, Jurassic World: The Exhibition opened in Bangkok, showcasing once again how audiences are eager for in-person, experiential storytelling. This type of project not only helps offset industry downswings but also aligns with the growing demand for physical, emotionally engaging experiences beyond the screen.”

WORLD’S-EYE VIEW

VES Members are artists with an eye for composition, beauty and light and shadow, both within the field of visual effects and as fine artists. The World’s-Eye View celebrates the creative spirit that unites our community by sharing original photographs created by our members and showcasing their unique views and personal approaches to the art and craft of photography. A panel of VES members reviewed and selected these 20 photos to share with the world. One image at a time, we invite you to see the world through the eyes of our global community. The full gallery of photographs can be found at the VES Flickr page: http://bit.ly/47Atvl0

Artist: Nitesh Nagda

VES Section: Bay Area

“In the middle of one of the world’s oldest rainforest in Khao Sok where the silhouettes tell the history.”

Silhouettes

“

“I love surrealism and the unpredictability of underwater photography. In contrast to this industry where everything is scheduled and has a goal, sometimes I do explorational photography with only the intent to create.”

Dream Artist: Antelmo Villarreal VES Section: Oregon

Solitary Artist: Ajit Menon VES Section: New York

This is a lovely solitary tree against a massive dune at sunset in Sossusvlei, Namibia.”

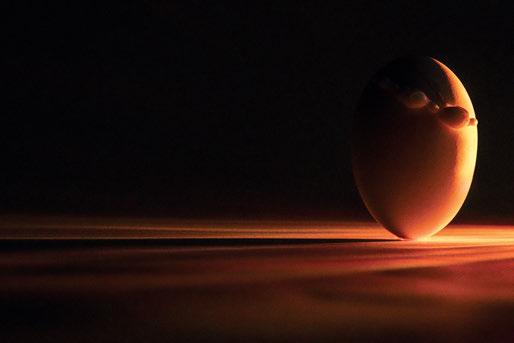

“This was challenge with the study of taking a photo of an egg. This one broke when boiled. I glue-mounted it and used smaller lights and crystals to create an abstract space-like environment. My goal was to take an egg as far away from being just an egg as possible. Because none of us are normal or just eggs.”

Broken Egg

Artist: Stephan Fleet VES Section: Los Angeles

Zabriskie Point DVNP

Artist: Zsolt Krajcsik VES Section: Los Angeles

“Wintertime in Death Valley National Park.”

“At eight, I found a camera on a beach, igniting my passion for photography, which led to my career as a VFX supervisor. This passion shapes my VFX process, from planning to finalization, aiming for photographic authenticity. Unlike my controlled VFX work, my photography involves minimal editing, capturing raw, unfiltered moments. My images invite viewers to pause and see the ordinary anew.”

“During filming of All That Is Left of You, in the old town of Rhodes, actors waiting for the call to action.”

The Wait Artist: Bastian Hopfgarten VES Section: Germany

The Gravity of Dreams Artist: Stephane Pivron VES Section: France

“The

multi-hued

mid-morning.”

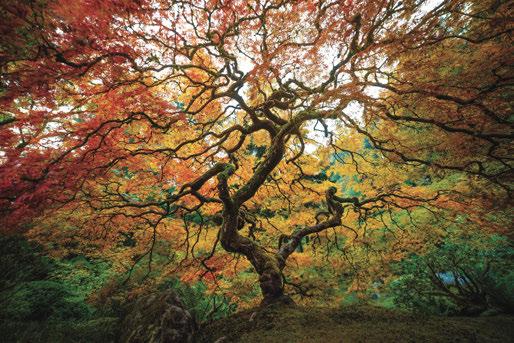

The Tree Artist: Anthony Barcelo VES Section: Oregon

famous

Japanese Maple taken at the Portland Japanese Garden

Silent Figures Under Pont des Arts Artist: Stephane Pivron VES Section: France

“Stolen moment from a Joseph Kolinski perfume shoot, captured at night under the Pont des Arts in Paris, shot with a Sony A7R and a Sony 50mm F1.2GM.”

Claustral Canyon

Artist: Marty Blumen

VES Section: Australia

“A lone canyoneer stands poised on a mossy boulder, dwarfed by towering walls draped in ferns and mist. In the stillness of the canyon, the scale of the world reveals itself: wild, ancient and humbling.”

Ethereal Drift

Artist: Timothy Zhao

VES Section: Vancouver

“As a VFX artist, I am constantly drawn to the subtle power of light, rhythm and natural form. I use B+W to strip away distraction, inviting the viewer to pause, breathe, and witness the quiet beauty that often drifts unnoticed beneath the surface.”

Red-Eye Tree Frog

Artist: Zsolt Krajcsik

VES Section: Los Angeles “A night photo in Costa Rica rainforest.”

Untitled

Artist: Alberto Loseno Ros

VES Section: Los Angeles N/A

“These two caught my eye between takes/setups a couple hours out of Budapest in a museum village. Hungarian is an interesting language and impossible to understand for an American, but fun to listen to.”

The Conversation

Artist: David Stern VES Section: Los Angeles

ELREM Artist: Chris Hönninger VES Section: Germany “Playing with mirrors.”

“I’m fascinated with the ephemeral, transient nature and light interaction with these megastructures of water vapor.”

“A

Aurora Borealis Over Lake MacDonald

Artist: Jason Patnode VES Section: At-Large

“The northern lights broke out over Lake MacDonald in Glacier National Park in one of the most stunning displays I have seen. This panoramic pic is comprised of five separate images.”

Los Angeles

Artist: Chris Schnitzer VES Section: Los Angeles

dramatic and rarely seen view of the City of Angels.”

Cloudscape Artist: Jason Key VES Section: Atlanta

City of Colors

Artist: Sam Javanrouh

VES Section: Toronto

“I wanted to capture the vibrant colors of Toronto in the fall. This is a panoramic blend of nine photos taken in downtown Toronto, using a drone.”

Beach Home

Artist: Evan Pontoriero

VES Section: Bay Area

“Climbing down the Jenner escarpment to find a beachcomber’s home.”

VES would like to thank our jury members: Chair: Jeffrey A. Okun, VES, Jurors: Adam Brewer, Rita Cahill, Toni Pace Carstensen, VES, Nicolas Casanova, Dao Champagne, Ian Dawson, Jason Dowdeswell, Tim Enstice, Urs Franzen, Brian Gaffney, Shiva Gupta, Dennis Hoffman, Robert House, Isaac Kerlow, David Legault, Suzanne Lezotte, Lance Lones, Josselin Mahot, Ray McMillan, VES, Chad Nixon, Christy Page, Jason Quintana, Erasmo Romero III, Daniel Rosen, Afonso Salcedo, Timothy Sassoon, Xristos Sfetsios, Russ Sueyoshi, Ahmed Turki, Sukhpal Singh Vasdev, Gautami Vegiraju, Robert van de Vries, Kate Xagoraris, Timothy Zhao.

GIVING FRANKENSTEIN THE SPARK OF LIFE

By TREVOR HOGG

Images courtesy of Netflix.

Frankenstein has long been a passion project for Guillermo del Toro, which is not surprising as he has mastered the art of creating a beautiful, grotesque Gothic aesthetic and has a deep fascination with monsters. Thus, he was the perfect choice to adapt Mary Shelley’s story, in which a scientist obsessed with defying death attempts to turn a creature assembled from various human body parts into a living being.

“[Monster stories] are excellent parables about the human condition,” states Guillermo del Toro, Producer, Writer and Director. “They tackle things that can be discussed without absolutes, so they have a symbolic power. You don’t have to talk about a middle-class father who is hard on his son wanting to be a rock ‘n’ roll star. You can actually talk about a father creating his son, and the son basically being crucified for the sins of the father. It is metaphorical and real at the same time; that’s what is fantastic.”

The creature determines the cinematic environment. “It’s like visually creating a terrarium. In terms of tone, you need to create a movie that allows the creature to feel real, not like visual effects, makeup, a combination of both or an actor wearing silicon prosthetics. The design of Frankenstein is more operatic, theatrical, and pushed so that the creature can exist there. You design the creature around the body and bone structure of the performer because it’s a character, not a monster.”

The iconic creation scene offers something different from previous film and television adaptations. “What you have almost never seen before is the actual anatomical putting together of the Creature,” del Toro remarks. “That is pretty goddamn new because most people just skip through it. You just see the Creature receiving the electricity. I wanted to shoot it as a joyous moment.

TOP: Victor Frankenstein (Oscar Isaac) visits the aftermath of a battle with a shopping list of body parts.

OPPOSITE TOP: Guillermo del Toro discusses a scene with Oscar Isaac behind an anatomically detailed and realist rendition of a human body. (Photo: Ken Woroner)