TRON: ARES - FUTURE VISION

Welcome to the Fall 2025 issue of VFX Voice!

Thank you for being a part of the global VFX Voice community. Our cover story ventures inside the highly sophisticated program, Ares, at the centerpoint of sci-fi action film Tron: Ares. We go behind the scenes of the twin brothers-fueled horror film Sinners, trending otherworldly streamers Star Trek: Strange New Worlds and Alien: Earth, and immersive gaming hit Star Wars Outlaws. We delve into trends around AI, VFX and advertising, amplify the latest content-generating tools for music videos, celebrate the artistry of matte painters and highlight the expanding alliance between virtual production and VFX.

VFX Voice goes up close and personal with profiles on MPC Paris leader Béatrice Bauwens and Mission: Impossible VFX Producer Robin Saxen. We get immersive with advances in VR-based mental health therapies with USC’s Dr. “Skip” Rizzo, showcase the state of VFX in Ireland in our special report, go down under with our VES Section spotlight on VES Australia, and much more.

Dive in and meet the innovators and risk-takers who push the boundaries of what’s possible and advance the field of visual effects.

Cheers!

Kim Davidson, Chair, VES Board of Directors

Nancy Ward, VES Executive Director

P.S. You can continue to catch exclusive stories between issues only available at VFXVoice.com. You can also get VFX Voice and VES updates by following us on X at @VFXSociety.

FEATURES

8 MUSIC VIDEO: CONTENT TSUNAMI

AI, VP and smartphones multiply options for frontline creatives.

14 VFX TRENDS: AI, VFX & ADVERTISING

AI, VFX software advances reshape short-form creation.

20 COVER: TRON: ARES

Bringing the Grid into the real world – with believability.

28 PROFILE: BÉATRICE BAUWENS

MPC Paris leader is a passionate promoter of French VFX.

32 TV/STREAMING: STAR TREK: STRANGE NEW WORLDS

Expanding the unexplored cosmos with virtual production.

38 UNSUNG HEROES: MATTE PAINTERS

Honoring traditional artistry while staying agile with new tech.

44 PROFILE: ROBIN SAXEN

Mission: Impossible VFX producer links efficiency and creativity.

50 SPECIAL FOCUS: IRELAND

Incentives and innovation signal a bright green future for VFX.

56 VIRTUAL PRODUCTION: WELCOMING THE SHIFT

The growing integration of VP into the traditional VFX pipeline.

62 FILM: SINNERS

A new approach was developed to achieve the twinning effects.

68 HEALTH & WELLNESS: VR & MENTAL HEALTH

Dr. “Skip” Rizzo on innovations in the field of VR-based therapy.

72 TV/STREAMING: ALIEN: EARTH

New alien creatures join the Xenomorph wreaking havoc on TV.

82 VIDEO GAMES: STAR WARS OUTLAWS

Massive Entertainment utilized VFX to create an immersive event.

DEPARTMENTS

2 EXECUTIVE NOTE

90 THE VES HANDBOOK

92 VES SECTION SPOTLIGHT – AUSTRALIA

94 VES NEWS

96 FINAL FRAME – THE SECRET OF IRELAND

ON THE COVER: Light-emitting vehicles, weapons and suits are part of the visual language for Tron: Ares (Image courtesy of Disney Enterprises)

VFXVOICE

Visit us online at vfxvoice.com

PUBLISHER

Jim McCullaugh publisher@vfxvoice.com

EDITOR

Ed Ochs editor@vfxvoice.com

CREATIVE

Alpanian Design Group alan@alpanian.com

ADVERTISING

Arlene Hansen arlene.hansen@vfxvoice.com

SUPERVISOR

Ross Auerbach

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Gemma Creagh

Naomi Goldman

Trevor Hogg

Chris McGowan

ADVISORY COMMITTEE

David Bloom

Andrew Bly

Rob Bredow

Mike Chambers, VES

Lisa Cooke, VES

Neil Corbould, VES

Irena Cronin

Kim Davidson

Paul Debevec, VES

Debbie Denise

Karen Dufilho

Paul Franklin

Barbara Ford Grant

David Johnson, VES

Jim Morris, VES

Dennis Muren, ASC, VES

Sam Nicholson, ASC

Lori H. Schwartz

Eric Roth

Tom Atkin, Founder

Allen Battino, VES Logo Design

VISUAL EFFECTS SOCIETY

Nancy Ward, Executive Director

VES BOARD OF DIRECTORS

OFFICERS

Kim Davidson, Chair

Susan O’Neal, 1st Vice Chair

David Tanaka, VES, 2nd Vice Chair

Rita Cahill, Secretary

Jeffrey A. Okun, VES, Treasurer

DIRECTORS

Neishaw Ali, Fatima Anes, Laura Barbera

Alan Boucek, Kathryn Brillhart, Mike Chambers, VES

Emma Clifton Perry, Rose Duignan

Dave Gouge, Kay Hoddy, Thomas Knop, VES

Brooke Lyndon-Stanford, Quentin Martin

Julie McDonald, Karen Murphy

Janet Muswell Hamilton VES, Maggie Oh

Robin Prybil, Lopsie Schwartz

David Valentin, Sean Varney, Bill Villarreal

Sam Winkler, Philipp Wolf, Susan Zwerman, VES

ALTERNATES

Fred Chapman, Dayne Cowan, Aladino Debert, John Decker, William Mesa, Ariele Podreider Lenzi

Visual Effects Society

5805 Sepulveda Blvd., Suite 620 Sherman Oaks, CA 91411 Phone: (818) 981-7861 vesglobal.org

VES STAFF

Elvia Gonzalez, Associate Director

Jim Sullivan, Director of Operations

Ben Schneider, Director of Membership Services

Charles Mesa, Media & Content Manager

Eric Bass, MarCom Manager

Ross Auerbach, Program Manager

Colleen Kelly, Office Manager

Mark Mulkerron, Administrative Assistant

Shannon Cassidy, Global Manager

Adrienne Morse, Operations Coordinator

P.J. Schumacher, Controller

Naomi Goldman, Public Relations

MUSIC VIDEOS AND VFX KEEP IN TUNE WITH EACH OTHER AND THE TIMES

By TREVOR HOGG

coordinated the

OPPOSITE TOP AND MIDDLE: Bluescreen was utilized for the aerial balloon shots in the music video for “Contact” featuring Wiz Khalifa and Tyga. (Images courtesy of Frender)

OPPOSITE BOTTOM: Door G makes use of a 56-foot-wide by 14-foot-tall virtual production wall in their studio located in East Providence, Rhode Island. (Photo courtesy of Door G)

Seen as a breeding ground for celebrated filmmakers such as David Fincher, Spike Jonze and the Daniels (Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert), music videos no longer require millions of dollars from a record company to produce or a major television network to reach the masses. The media landscape continues to evolve with the emergence of virtual production, AI and Unreal Engine, as well as what is considered to be acceptable cinematically. Whether an actual renaissance is taking place is open to debate, as “Take On Me” by a-ha, “Sledgehammer” by Peter Gabriel and “Thriller” by Michael Jackson remain hallmarks of innovation despite the ease of access to technology and distribution that exists nowadays for independent-minded content creators and musicians.

Constructing a 56-foot-wide by 14-foot-tall virtual production wall in East Providence, Rhode Island for commercials, movies and music videos is Door G, a studio that also does real-world shoots, makes use of AI-enhanced workflows and handles post-production. “Independent artists can put their work out on YouTube and social media, and get attention that way,” states Jenna Rezendes, Executive Producer at Door G. “People may not have heard the song but have seen the video. The visual is important.” One has to be agnostic when it comes to methodology and technology. She says, “We can work with clients or directors and come up with a plan that suits their creative. Does it make sense to do it virtually or lean into some AI to help create some backgrounds? All of these methods can be combined to create the best product. There are numerous tools accessible to a lot of different people. People are making music videos on their own using iPhones and putting them on TikTok. It’s a matter of how the approach fits the end result you’re looking for, within your budget.”

TOP: Ingenuity Studios provided and

visual effects work for the music video for “My Universe” by Coldplay + BTS, with contributions from AMGI, BUF, Rodeo VFX and Territory Studio. (Image courtesy of Ingenuity Studios)

AI will become a standardized tool. “It allows you to be more iterative in the creative development phase. You can churn through ideas and not feel like you’re wasting a lot of valuable time,” remarks Joe Torino, Creative Director at Door G. “AI is a quick pressure test of ideas versus spending weeks building things out only to realize it’s not going to work. Like any other new technological development, AI will become a choice of the creator and the person who is buying the creative. Do they want something that is AI or human-created or a combination of both? It will become clear in the future what’s what, and people will have a choice to make what they want to invest in.”

Unreal Engine is another important tool. “Unreal Engine allows you to create worlds from scratch, but, that said, it still requires a lot of processing power not so widely available yet,” Torino states. “We did a music video that was this post-apocalyptic world entirely created in Unreal Engine. This is something you would struggle to do as video plates. This allowed them, on a reasonable budget, to create this world that otherwise would have been impossible.” Content is not being created for the long term. “Things are more disposable,” Torino believes. “If you do a music video that is innovative and creative, you get a chance to have a moment, but I don’t know how long that moment will last. You can make a great music video with one filmmaker and artist, and that probably wasn’t the case in the 1960s, 1990s and early 2000s,” Torino states. “The biggest factor for change is through AI. Soon, you will be able to make an entire music video using AI. We’re probably six months to a year out from someone who can recreate the aesthetic of the music videos for ‘Take On Me’ or ‘Sledgehammer’ with a few clicks and some dollars to spend on AI video rendering platforms. It will

be polarizing like everything else, but polarization ultimately gets eyeballs, so people are going to do that.”

Leveraging his experience as a visual effects producer, Max Colt established Los Angeles-based Frender, which has worked on award-winning music videos for the likes of Harry Styles, Marc Anthony, Thomas Rhett and Nicki Minaj. “For me, it’s the music, the camera operator, the idea and a bunch of tools to play with,” observes Colt. “Right now, we work with AI technology because, for the past three years, it has become a trend. It’s also easy to jump into the industry because you can shoot a music video on an iPhone like Beyoncé – it’s simple to create content, but it’s not easy to create good content. I’ve been in this industry for 15 years and have done 500 or 600 music videos. I am still doing them because I personally like music as well as the freedom, and getting to work with the creatives and musicians.” Virtual production cannot be treated in the same way as a greenscreen shoot. Colt notes, “You need to approve everything before the shoot, and if you want to change something, it’s hard but still possible. This is a new tool, and for a big production like a movie, it’s time and cost-effective. For a music video, virtual production is okay; maybe in the next five years it will become cheaper than shooting regular greenscreen.”

“You can shoot a nice story without any post,” Colt observes. “It is a trend to create nonexistent things and visual effects help you to do that. You can produce some cool stuff with After Effects. But for simulations you need to use Nuke or Houdini. If you aesthetically understand the difference, you can play with these tools. Music videos are a great platform to play with new tools. Movies are a risky business, and no one spends a lot of money on new stuff.”

In America, music videos, commercials and films are treated as different industries. Colt remarks, “Sometimes it’s hard to change industries. If you start on music videos, it’s hard to jump onto big movies. Europe is more flexible. However, music videos are the best platform to start your career, understand the process and see the

TOP TWO: From Normani & 6LACKS’ “Waves” music video. Software and technology have become readily available along with tutorials via YouTube, which means that record labels and artists no longer have to hire major visual effects companies for their music videos. (Images courtesy of Frender)

BOTTOM: Diljit Dosanjh’s music video of his song “Luna” from the album MoonChild Era. Music videos provide the opportunity to experiment with new tools. (Image courtesy of Frender)

final result.” Projects vary in scope when it comes to enjoyment, he adds. “Some projects I love and have a lot of stories. Others are copy-and-paste projects. Just like being a visual effects artist, sometimes it’s technical work such as clean-ups, while other times it’s creative, like producing nonexistent things. It really depends.”

Ingenuity Studios was established to create visual effects for music videos, which continue to be part of a corporate portfolio that has expanded into television and feature films. Noteworthy collaborations have been with musicians such as Shawn Mendes, Selena Gomez, Taylor Swift, Billie Eilish and BTS. “Music videos have been the leading example on how viewing and creation habits have changed as well as the purpose of these things,” observes David Lebensfeld, President & VFX Supervisor for Ghost VFX and Ingenuity Studios. “Starting with the MTV era, music videos at their core were promotion to sell albums and took on a larger role in society when they became a place where creative people could go and stretch their legs and do stuff that wasn’t possible in other mediums. Record labels were willing to pay for it because it actually coincided with how music gets promoted. Certainly, more recently, TikTok and Instagram, probably more than YouTube, are where music gets promoted. On a production scale, you approach it differently for TikTok than you do for the MTV era because you would have $2 million to $3 million videos, whereas now it’s about viral trends, which are completely different in how those things get exposed and become popular.”

“Music videos are more divorced from cinema than they were in the A Hard Day’s Night or MTV era where you would have the same people making those things,” Lebensfeld remarks. “Now it’s more about capturing the moment and zeitgeist quicker, dirtier and less polished but maybe equally as clever. For that, you don’t need a six-week timeline and a $1 million budget to make a music video. The other benefit, particularly around the economics of record labels, is they used to put together a plan where you would

TOP: Boston-based independent artist Llynks filmed a music video for her song “Don’t Deserve” in Door G’s East Providence, Rhode Island studio. (Photo courtesy of Door G)

BOTTOM TWO: Frender produced the music video for Coldplay’s “Up&Up”. (Images courtesy of Frender)

come out with a big artist’s album and say, ‘These are the three singles that we’re going to put a bunch of money behind and promote.’ That’s when music video production would begin. It was before the albums came out. Over time, even in the MTV era, the record labels started waiting and seeing what hit in order to better deploy their capital to promote the album. With this current trend, it’s even more so, where they’ll make a music video for something they had no idea was going to be a hit, go with the moment and be able to produce something and put it on TikTok, or let the audience make it user-generated and incentivize that; that is the best use of their capital to promote an album.” Some things will continue to stand out. “But the way that content is created and consumed is going to be more about reaching niche, localized audiences versus making something big and expensive for everybody.”

Music videos themselves are not revenue generators. “AI, Unreal Engine and cellphone cameras – these tools that allow you to make content or user-generated content at a larger scale for a lot less money is where this is heading and arguably is already,” Lebensfeld observes. “The biggest piece of technology that is changing the way that music videos get made isn’t actually production related. It’s social media and the technologies behind that, which will continue to evolve with AI or hardware that gets better, easier or more ubiquitous. If you start having people wearing AR glasses all day long, then you’re going to need content for that. It’s not going to be about how technology is changing what gets produced. It’s more about how technology is changing how things get produced [for YouTube, TikTok and Instagram] and the need for content. Arguably, right now, video cameras in your phone are a big piece of the production puzzle, and will become more popular as people consume more content on the go, in a virtual environment or at a Fortnite concert. The AI piece allows for a lazier production process, so you could have somebody generating prompts of something they think is funny and setting it to a Lady Gaga song, and that’s what everybody finds hilarious and ends up blowing up a single.”

TOP AND MIDDLE: Frender collaborated with Chris Brown and Nicki Minaj on the music video for “Wobble Up.” (Images courtesy of Frender)

BOTTOM: Door G has an agnostic attitude towards methodologies and technologies as there is not one solution for everything. (Photo courtesy of Door G)

NEW TECH AND VFX ADVANCES SPARK COMMERCIALS AND SHORT-FORM

By CHRIS McGOWAN

It’s not just advances in traditional VFX software that are transforming advertising, it’s the rise of emerging technologies like generative AI that is reshaping the approach to short-form content creation, according to Piotr Karwas, VFX Supervisor at Digital Domain. “From early stages like storyboarding, concept art and previs, to sometimes even contributing to the final image, this hybrid method of blending generative AI with classic VFX techniques marks an entirely new chapter in effects production,” Karwas states. “Real-time rendering with game engine technology is becoming an increasingly integral part of our VFX workflow. It plays a particularly significant role in previsualization and motion capture, enhancing both speed and creative flexibility.”

Karwas notes, “Digital Domain has a remarkable history of producing high-impact visual effects for advertising and shortform content, consistently pushing the limits of what is achievable in the medium. Since its founding, the studio has delivered cinematic quality and compelling storytelling in commercials, collaborating with some of the industry’s most visionary directors, including David Fincher, Mark Romanek, Michael Bay and Joe Pytka.”

“Whether it’s crafting hyper-real environments, photoreal digital humans or seamless compositing for global campaigns, Digital Domain has played a pivotal role in redefining audience expectations for brand storytelling,” Karwas says. From Super

TOP: Daredevil, Colossus and other Marvel characters in the Electric Theatre Coke commercial bridged high-end visual effects and classic comic book art. (Image courtesy of Coca-Cola and Marvel Comics)

OPPOSITE TOP: Rodeo FX crafted 3D billboards in Times Square and Piccadilly Circus to advertise the survival-horror video game The Callisto Protocol (Image courtesy of Rodeo FX and Striking Distance Studios)

Bowl commercials to global product launches, he comments, “the studio’s ability to combine cutting-edge visual effects with engaging narratives has made it a preferred partner for major brands aiming to make a bold and immersive statement in a competitive advertising landscape.”

“Visual effects and advanced digital technologies are transforming how brands engage with audiences,” adds Karwas. This includes the growth of interactive and immersive advertising. He explains, “Digital Domain is at the forefront of this change, utilizing its innovative digital human technology to create experiences that go beyond traditional media. A powerful example is The March 360, a real-time virtual reality experience that not only tells a story but also places viewers inside a pivotal moment in history. By authentically recreating the 1963 March on Washington and digitally resurrecting Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to deliver his ‘I Have a Dream’ speech, Digital Domain has shown how VFX can produce emotionally resonant and immersive content that is both historically significant and technologically innovative. This goes beyond mere advertising; it is experiential storytelling that blurs the line between reality and digital creation, engaging audiences on a deeply human level.”

Electric Theatre Collective demonstrated cutting-edge visual effects in “Coca-Cola – The Heroes,” for which it won the Outstanding VFX in a Commercial prize at the 2025 VES Awards,

as well as the best “Lighting & Compositing” award. Directed by Antoine Bardou-Jacquet, the project merged two iconic brands: Coca-Cola and Marvel. The visual effects and animation were integral to the storytelling. “From the outset, the campaign needed three things: carefully designed interpretations of key Marvel characters, CG development and animation of those characters, and vibrant color grading,” says Ryan Knowles, Electric Theatre Collective Creative Director.

“After some early engagement where we created some test animations for Antoine and the agency, GUT [Buenos Aires], we were brought in as a key creative partner for the campaign,” comments Greg McKneally, CG VFX Supervisor at Electric Theatre. “The brief for this project was to bring illustrated and sculpted Marvel heroes to life, seamlessly embedding them in the real world of a comic shop. We needed to tell a dramatic story while retaining a unique look for each character based on the medium they originated from: comic book, t-shirt or collectible.” McKneally notes, “With dynamic camera work and physical interactions, we decided the base of each character needed to be CGI. To maintain authenticity, we used traditional 2D animators, illustrators and painters throughout the process, adding hand-made elements into scenes. This approach allowed us to bridge the worlds of comic book art and high-end CGI, allowing for complex scenes in the physical world of the set, with a hand-crafted 2D feel.”

TOP TO BOTTOM: For the “Malaria Must Die” TV spot campaign, Digital Domain utilized Charlatan technology to age David Beckham nearly 30 years to deliver a powerful speech and message. (Image courtesy of “Malaria Must Die” campaign and Digital Domain)

Rodeo FX has delivered visual effects for commercials for many notable clients, including McDonald’s. (Images courtesy of Rodeo FX and McDonald’s)

Electric Theatre brought Juggernaut and other Marvel superheroes to life in the real world of a comic-book shop, and Marvel together with Coca-Cola. (Image courtesy of Coca-Cola and Marvel Comics)

McKneally continues, “Our primary software pipeline involves Maya for modeling, rigging and animation; Houdini for shading, scene assembly, lighting, FX simulation and rendering; and Nuke for compositing. Houdini, and a number of different custom tools built within it for the project, formed the backbone of the creation of the stylized character, including Paintify 2.0, which allowed us to create Daredevil as a moving water-color and pencil illustration.”

To achieve the look of Black Widow as a 2D illustrated character moving in three dimensions, Electric Theatre worked with a traditional comic book concept artist to develop a set of consistent illustrations. Knowles explains, “These were used as a guide for the development of the CG character, and we also trained a bespoke machine learning model on this original concept art. This machine learning model was used to process and filter some of the CG renders of the character. It was a key ingredient in the recipe of the final look of Black Widow, which was crafted in compositing.”

“Simple real-time rendering was used extensively in the previs phase of the project, during which we carefully mapped out each camera move and blocked out the animation for the scenes in Maya,” McKneally says. “We were able to rough out the placement of the lights and key shadow elements, as well as the characters themselves. To create the unique shading style of Juggernaut, we built a custom shading system which generated the shadows as geometry in the scene, meaning that the artists working in Houdini had a real-time preview that was very close to the final look of the character.”

“The biggest challenge in this project was that each character required a different technical and creative approach,” McKneally says. “For example, while Colossus is a resin maquette and could use a more conventional CG approach, Juggernaut is inspired by 1980-1990s comics. He is a 3D animated character, but has a limited color palette and uses a bespoke shading system, hatch line geometry, mid-tone shadow mattes which reveal classic printed half-tone shading, and hand-painted 2D animated expressions. All of this was composited together with mis-printing filters, bleed, grain and irregular line work to achieve the final look.” McKneally adds, “Meanwhile, Captain America and the comic book city features custom toon shaded CG, hand-painted buildings carefully recreated and textured in CGI, hand-painted skies, a custom linework system, 2D FX animation and crowd simulations.”

Daredevil was one of the most complex challenges. “His entire look is an evolving water-color painting with pencil details,” Knowles comments. “The paint strokes that define his form had to feel 2D but still react in a realistic way to the lighting of the environment he was moving through. This was achieved in a combination of 3D lighting and an evolution of our bespoke 3D paint system in Houdini – originally developed on ‘Coca-Cola Masterpiece’ –and then assembled and finessed in the hands of the compositors.” According to McKneally, “3D animation and compositing tools are progressing at a rapid rate. This, combined with the incredible pace of development for machine learning tools, means that the tech landscape for visual effects in advertising is evolving at speed. At Electric, we have created a workflow that allows artists to harness the latest developments in image generation, animation, rendering

and compositing, staying nimble and flexible enough to swap new tools into our workflow as the technical or creative demands evolve. We’re finding many projects now benefit from a bespoke combination of traditional and emerging tools.”

Knowles observes, “One of the biggest challenges we have seen comes from rapid AI image generation. Polished images generated by all parties – agencies, clients, directors – which help to sell a concept or idea, but risk shortcutting the creative development. It’s a high level of finish in a very short time, but can often lack the nuance, depth and personality that multiple iterations in a traditional concept art development process can achieve. We strive to strike a balance.” Knowles adds, “To bring this nuance back into the fold, our creative team uses a mix of traditional design and animation workflows to iterate ideas and then engage custom machine learning workflows to add polish and variation. This allows for rounded creative development with the high level of ‘finish’ now expected by agencies, directors and clients. As machine learning image and video generation becomes more and more available – and quality improves – having the ability to guide the artistry that underlies the final image becomes even more valuable for creating original, breathtaking work,” McKneally explains.

“As an end-to-end production house, VFX is at the heart of what Alongside does,” says Glen Taylor, Founder of Alongside Global. “VFX is central to our efforts in the advertising industry, and this trend isn’t slowing down. We use it all the time to drive storytelling, realism and creative innovation. From compositing and CG to AI-enhanced workflows, VFX helps shape our final output across our projects. We just created a new website for the healthcare company Calcium, where we built an asset in 3D. VFX spans mediums.”

The pace of change is intense in VFX software and tech and greatly affects advertising. “New tools are released every day –face swaps, language transcription and translation, and AI scene building, to name a few,” Taylor says. “Unreal Engine is already transforming how we work. It allows for live client feedback, instant changes and scalable outputs from AR and VR to social and film. Once we hit photorealism in real-time, it will become the core production tool.” He adds, “The challenge is knowing what to use and when. We’re experimenting constantly, especially with AI-generated content that’s licensing-safe and creatively sound. The goal isn’t to replace creativity – it’s to move faster and smarter.”

Rodeo FX has delivered visual effects for many advertising clients, including McDonald’s, Nissan, Red Bull and Tiffany & Co. Ryan Stasyshyn, VFX Supervisor and head of the Toronto office for Rodeo FX, remarks, “Content creation has become remarkably accessible, especially with the integration of AI. Simultaneously, our clients are increasingly seeking greater levels of collaboration throughout the creative process.” Real-time rendering is coming into play in production and VFX for advertising. “That said, I think it’s worth noting that real-time has a number of hurdles that need to be addressed before it becomes the mainstay of the industry. In regard to real-time rendering to output final frames in a traditional VFX approach, I believe the industry is at that point and,

Rodeo FX Ads & Experiences helped create the immersive event Stranger Things: The Experience, working with Netflix, Fever, Mycotoo and Liminal Space. (Image courtesy of Rodeo FX and Netflix)

Rodeo FX worked on visual effects for Tiffany & Co. as part of the global “About Love” brand campaign. (Image courtesy of Rodeo FX and Tiffany & Co.)

TOP TO BOTTOM: Deadpool enjoys popcorn and a Coke in the comic-book shop created by Electric Theatre. (Image courtesy of Coca-Cola and Marvel)

TOP: The Electric Theatre ad, uniting 2D and 3D animation with live-action in a comic-book shop, won VES awards given in 2025 for Outstanding VFX in a Commercial and Outstanding Lighting and Compositing in a Commercial. (Image courtesy of Coca-Cola and Marvel)

BOTTOM: The TIME magazine cover image of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was created using a historically accurate 3D rendering of King drawn from “The March,” a virtual reality experience that depicts the 1963 March on Washington. (Image courtesy of Digital Domain, Hank Willis Thomas and the Martin Luther King Jr. Estate)

depending on the studio, is either there or going to be there shortly. As real-time rendering pertains to virtual production, I think its use has shown real promise but also a large barrier, with education of the users being the biggest hurdle. The technology is there, and the talent in the industry can certainly support it. I think we may have done ourselves a disservice by overhyping it a little too much out of the gate and sometimes setting unrealistic expectations.”

Erik Gagnon, VFX Supervisor and Flame artist for Rodeo FX, says, “Rodeo FX’s work in advertising is decisively oriented toward the future through the proactive integration of artificial intelligence into our creative process. This approach enables us to provide our clients with a highly personalized and innovative partnership, elevating their original concepts into stunning visuals and unique storytelling experiences. Advancements in VFX tools and technologies are profoundly transforming our approach to advertising. Today, we focus less on isolated software and more on comprehensive ecosystems of specialized tools, allowing us to push creative boundaries. These developments make our production pipelines more adaptive and supports artists in becoming increasingly versatile and agile.”

Gagnon continues, “We are witnessing the rise of interactive and immersive advertising powered by VFX. Rodeo FX has crafted visually compelling experiences, such as 3D billboards in iconic locations like Times Square and Piccadilly Circus for The Callisto Protocol. Additionally, during the Cannes Film Festival, Rodeo FX Ads & Experiences created an ingenious activation for Stranger Things, captivating attendees and sparking their imaginations. The synergy between VFX, advertising, and experiential marketing represents an ideal combination to genuinely bring brands to life. By integrating cutting-edge visual effects into interactive environments, we engage audiences more deeply, stimulating their senses and creating memorable brand connections. This powerful blend not only elevates brand awareness but also ensures impactful and lasting impressions.”

Franck Lambertz, VFX Supervisor and head of Rodeo FX’s Paris office, sees AI-powered image and video generation as “an exciting new playground.” He notes, “While the technology is still developing and can be unstable, we see it as another valuable tool in our creative arsenal. It still requires passion and expertise to avoid clichés and elevate the final result. Our roles may become less technical and more focused on creative leadership.” Lambertz continues, “Increasingly, clients arrive with well-developed reference decks. Thanks to tools like Midjourney, some directors have already visualized their concepts. This makes the creative process more efficient and enables us to work together more effectively to finalize the vision.” Lambertz adds, “Sometimes, clients challenge us with real-time projects. Depending on the brief, we assemble the right pipeline and talent to deliver top-tier visuals. Recently, we completed a VR experience for a live event in Paris – our first time producing a 7K, 60fps stereoscopic render, fully synchronized with fan and lighting effects. Watching the team immerse themselves in the experience with VR headsets and exchange feedback was a memorable moment.” Concludes Karwas, “Advertising is rapidly entering a new era. The integration of generative technologies and VFX is unlocking entirely new possibilities for connecting with audiences, enabling brands to engage and interact with customers in ways that were previously unimaginable.”

PROGRAMMING THE REAL-WORLD INTO TRON: ARES

By TREVOR HOGG

As much as Tron was prescient in regards to the technological and societal impact of computers, the growing debate over the application and ramification of artificial intelligence has worked itself into the video game-inspired universe conceived by Steven Lisberger with the release of Tron: Ares. Whereas Tron and Tron: Legacy essentially took place within the digital realm, the third installment, directed by Joachim Rønning, goes beyond the motherboard as an advanced AI program known as Ares (Jared Leto) embarks on a dangerous mission in the real world.

“The core of our film is this contrast between the Real World and Grid World, which has been established within the first two Tron films,” notes VFX Supervisor David Seager. “The big challenge for us was, how do you bring the Grid into the real world in a believable fashion? There is a lot of embellishment that could be made when you’re inside the Grid because you can say, ‘This is inside of the computer, so Grid things can happen.’ But if you did some of those exact same things in the photography you shot in the real world, it would begin to break the illusion. Joachim Rønning drove it from the start by embracing, ‘What does a Light Cycle look like in the real world? How does it behave?’ There were all of these different things we had to embrace and answer for ourselves to find a language that first and foremost supports the story, but, also, the more believable the visual is, the more people are going to buy into the story.”

Images courtesy of Disney Enterprises.

TOP: Practical Light Cycles were built with LED light strips, which allowed for scenes in the real world to have the proper reflections and refractions.

OPPOSITE TOP: Director Joachim Rønning talks to Jared Leto about his vision for the Tron franchise. (Photo: Leah Gallo)

OPPOSITE BOTTOM: Light Ribbons surpass lightsabers in complexity.

Light-emitting vehicles, weapons and suits are part of the visual language for Tron. “With the majority of our film being in the real world, we embraced shooting as much as possible in the real world,” Seager states. “The Light Cycles are the best example of that. You can sit there and go, ‘You want to shoot in the real world. Then go with a camera, shoot an empty road and imagine what’s happening.’ Or, what we decided to do, which is to say, ‘We’re going to have proxy bikes that represent Light Cycles.’ Our entire team worked together to find these electric Harley-Davidson bikes that

were modified to have the same wheelbase of a Light Cycle and had the stunt team driving through the streets doing the action. I find you get that added reality of the real physics of the bike having to change lanes, pulling in front of a car and the camera car following. The speed is different, so the camera operator has to correct and keep his eye on the camera. All these million decisions go together to make a shot that looks like a motorcycle driving down a street. Then, our job is to go back, and over the top of that proxy we put our Light Cycle. We worked with the lighting department and

put a bunch of LED bricks on bikes to have them emit light. Even the stunt riders’ safety suits had light lines. Our hope there is you might get some happy accidents. The fact that we had a real bike reflecting where it needed to reflect and casting that light where it needed to go was a guide. Were there times when we wanted to deviate from that motion? Absolutely! However, the number of wins we have far outweighed those times we had to go in there and paint some light out.”

Among over 2,000 visual effects shots produced by primary

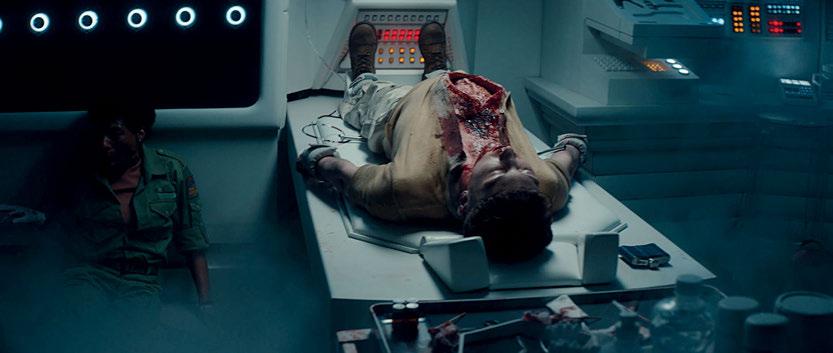

vendor ILM, as well as Distillery VFX, Image Engine, GMUNK, Lola VFX and Opsis, is the signature action sequence where a pursuing police car gets sliced in half by a Light Ribbon generated by a Light Cycle. “You see what they filmed practically and notice what you need to do,” remarks Vincent Papaix, VFX Supervisor at ILM. “There is postvis happening. We need to make it look photoreal, and for the way we see a Light Ribbon, it’s in its name. It’s light and Ribbon, so we make it an indestructible piece of glass emitting energy that can cut things. The special effects team had a precut police car, pulled it with two wires and then separated it. What we enhanced in CG was the Light Ribbon, but also the sparks, the piece of the engine falling down, dust and smoke. We also had to have a tight match to the police car because of all the interactive light and reflections that go in there. We could have done full CG, however, because of my compositing background, I am a big fan of trying to preserve the photography. It was meticulous work from the 3D and 2D departments to blend the plate and CG that was going on top to make it seamless.”

Appearing in the sky is the Recognizer. “What we did in order to make the Recognizer believable in the real world was to add a lot of details, like screws and an engine that was referenced from a rocket ship,” Papaix states. “It’s still the design of Tron, but with the technology of our real world to make sure this can fly in a believable way.” A larger issue was the environmental integration. “We used

TOP: Ares utilizes 3D printing technology to enter the real world.

BOTTOM: Complicating the Light Ribbons is the history of where they were previously included in shots.

Burrard Street, one of the biggest avenues in Vancouver, but when we put the Recognizer in the scene, it would be in-between buildings when it’s supposed to move through the street. That’s because in the story the Recognizer is chasing a character, so it needs to be not just over the city but be able to go through the city. In order to do this, sometimes we had to widen the street, which was quite a challenge.” Vancouver is known for rain. Papaix says, “All of our photography work had wet ground, and wet means it reflects a lot. On set, they put a lot of LED tubes where the action was supposed to be. Most of the time it worked great. We built an entire Vancouver in CG and had a couple of blocks at the ground level that were a photoreal full CG asset. We put in the effort to have a CG replica of the real photography, so we were able to render our CG version of the city to patch things as needed or integrate things because the action got moved.”

Animators had to act like cinematographers. “At the end of the third act, there is a dogfight between some Tron Light Jets and a F-35, and besides animating the vehicles, we also animated all of the cameras,” states Mike Beaulieu, Animation Supervisor at ILM. “We looked at aerial footage of different films or documentaries, and made a list of what kinds of lenses we usually use when we’re shooting stuff like that. It also gets creative because our director has a sensibility for what kind of lenses he prefers and what types of shots he likes to have. We can make adjustments there. We

TOP: A dramatic aerial dogfight takes place between Light Jets and a F-35.

BOTTOM: The big challenge was how to bring the Grid into the real world in a believable fashion.

TOP: Principal photography took place in Vancouver with the majority of the scenes shot at night.

BOTTOM: Joachim Rønning has a conversation with Greta Lee while surrounded by a massive and dramatic practical red set constructed for scenes that take place within the Dillinger Grid. (Photo: Leah Gallo)

would animate everything in 3D space first and then we would go in with an eye of, ‘How would we film all of this stuff?’ We would cover it with different camera angles and see what angles looked most interesting, which ones tell the story the best and still have an energy to it without getting too flat; 200mm to 400mm lenses tend to flatten everything, so to have a sense of traveling through 3D space with lenses like that is tricky. You can have a jet flying at you going 300 miles per hour, but with a 400mm lens, when you’re that far away, it doesn’t look like it’s changing that much. We had to get creative by covering it with a 100mm lens so we can actually read some of that travel of the jet flying around.”

A new Identity Disc is introduced. “You get to read a little bit more of the animation of the triangle disc that Ares has as it’s flying through the air,” Beaulieu remarks. “Because of its shape, you don’t always register the revolutions that the circular disc is doing as it’s getting thrown. The triangular disc also had these little blades that come out on the ends, which adds to the silhouette. We had conversations about how the triangular discs should move and behave. Do they behave as you would expect in the computer program where they go on a perfectly straight line and hit things and rebound, like Captain America’s shield where it deflects off surfaces? Or do we play it more [as if] they have to arc like a frisbee or boomerang? We ended up falling into a realm where we did a bit of both. Whatever felt best for the shot. If it needed to be something fast and have a big impact then something that was straight would feel better. But in the wider shots we had to put an arc on some of the discs to differentiate them. There is a sequence when we have these ENCOM soldiers flooding the plaza and they’re throwing discs. There are 15, 20 or 35 discs flying around in the shot, so to make them all read, we had to vary what they were doing. Some of them are flying straight and others are on a bit of an arc.”

Light Ribbons surpass lightsabers in complexity. “There’s something that nobody realizes, which is the history of Light Ribbons is tricky,” notes Jhon Alvarado, Animation Supervisor at ILM. “Basically, for every shot, you have to animate Light Ribbons four shots before it.” Performances had to be altered because of the Light Ribbons. “If you play that shot a little longer, they’ll be going straight through a Light Ribbon. We had to change the motion to make them get past it. There are happy accidents that come about where an actor leans over a tiny bit, and there’s nothing there to tell her to do that, but it works perfectly with her getting out of the way of the Light Ribbons. Then Jeff [Capogreco, VFX Supervisor] adds a reflection of the Light Ribbons reflecting on the environment and face, and all of a sudden you go, ‘Those Light Ribbons were there the whole time. How did they do that?’” The Light Ribbons had to be produced quickly and efficiently. Alvarado says, “At the beginning it was a hard, slow process to get the Light Ribbons generated, so we took a lot of technology and worked with our pipeline and R&D to determine how we get this in Maya so the animators are able to generate Light Ribbons in real-time or quickly whenever there is a change. For example, if we have to do 300 or 500 frames of history, we don’t want to be there waiting for half an hour as the Ribbons generate. We want to see it straightaway. There was a lot of work that was done to accommodate for these changes that happen in the filmmaking process.”

TOP TO BOTTOM: Light Ribbons had to be adjusted to suit the performance of the actors.

Over 2,000 visual effects shots were produced by ILM, Distillery VFX, Image Engine, GMUNK, Lola VFX and Opsis.

The special effects team led by Cameron Waldbauer created a practical police car that could be split in half, while the Light Ribbon was inserted later in post-production.

Ares originates in the Dillinger Grid, which has a red color palette and resembles an industrial wasteland. “The environment itself is loosely interpreted as a giant motherboard surrounded by voxelated water,” states Jeff Capogreco, VFX Supervisor at ILM. “There is a whole sequence where Ares and Eve are riding a Skimmer, a floating motorcycle that causes the water to create a giant rooster tail of bioluminescence and water spray. We did this whole deep dive of finding a bunch of clips of rooster tails shot at different times of day and angles, and we had the shading folks go in and light it, match it and validate it. Once we had that in the can, we started to interject what we were going to be doing. The other neat thing is, as you’re going along the water you start to realize that the water is actually a bunch of grids. Imagine you’re in fairly calm water where every 20-by-20 meters, there is a red border that outlines an area. One neat component is, as the Skimmer passes through these gates, it charges the rooster tail. You get these bursts of beautiful bioluminescence energy that illuminates the environment. We wanted to give it a visual feast.”

“Another department that we collaborated with was environments because you can imagine the Dillinger Grid being huge,” Alvarado remarks. “The Skimmer is traveling 150 miles an hour. We had to find ways for us to change and add things in animation that environments then used to Tron-ify the world and still feel in that environment. Another thing that we [addressed] was how do we create life in this Dillinger Grid? We have people and objects flying, and to go to every shot in animation and add that to this huge world would have been time-consuming. I spent time working with the environments artists to create a Dillinger Grid library of life. Then, environments procedurally put it within this grid, and we see it in shot. If something calls out in the shot then we can go in and change it. But most of the time we were like, ‘That’s enough.’ Things like that allow us to use the departments, collaboration and technology to help us get the best out of it rather than brute force our way into it all the time.”

When it comes to figuring out how Ares makes the transition from the Grid World into the Real World, a current technology was utilized. “They didn’t want that sharp contrast, like computer and real,” Capogreco reveals. “You can imagine these conversations. There was at least a year’s worth of R&D and trying to figure out, how do you bring a program into the real world? We leveraged the idea of 3D printing technology. What you will see are things that are born out of Jig. If you know anything about 3D printing, you get these pieces that support the model inside, and what you will see visually are lasers effectively creating these structures, and inside the structures are printed human beings or programs or vehicles that are then born into the real world. It’s beautiful. Lots of deep contrast, sparks and lasers. It’s science fiction at its best.”

It is not always about being revolutionary. Capogreco observes, “It’s finding ways to get the most out of what we have as opposed to reinventing something. With present-day computer technology, we’re not having to rewrite renderings. We’ve got Pixar’s RenderMan, which is phenomenal. It’s more about how can we maximize for performances as well as working with Jhon and animation to make sure we’re obeying physics – and not changing things too quickly or doing things that are going to make simulations go off the rails. It has been a great process on this show.”

BÉATRICE BAUWENS: A CHAMPION FOR GROWING FRENCH VFX

By OLIVER WEBB

Béatrice Bauwens was born and raised in Tourcoing near Lille in the North of France where her parents were teachers. “I studied first at Lille University of Science and Technology,” Bauwens begins. “At that time, I wanted to be a sound engineer, and I always loved science. Music was also in my background. Back then, there were very few places offering a dedicated education in the subject [of sound engineering]. I studied electronics, then with a specialization in Image and Sound at Université de Bretagne Occidentale in Brittany, and the world of images opened up to me. I discovered editing and computer graphics. I had a few courses in POV-Ray, Autodesk 3ds Max and coding during those university years. My career as a sound engineer ended there, as I was discovering these new fields with images and collaborative projects. Then I took a last Masters year in production back in the north of France at Université Polytechnique Hauts-de-France in Valenciennes.”

Bauwens’ first break came during her studies where a documentary project required generating a car in CGI, with the compositing directly done in the editorial software Media 100. “It was really a self-discovery with no real teaching about the art at all, and that’s it,” Bauwens says. “When I began working, my first experience was as a technician/production assistant for a documentary producer, more on the edit side. VFX was not something that was of interest. I was involved with the editorial and tape dubbing. Then, I moved to Mikros Animation in 2002, and it’s really where I discovered the ‘real’ visual effects. I was a technical assistant in the CGI department of Mikros; CGI to video transfer, rendering watching, digital archiving, IO and linking with editorial. I have never been a graphist, but I’ve always worked with them side by side.” The visual effects part of Mikros for film and episodic changed its name in 2020.

“After technical years in Mikros,” Bauwens continues, “I moved to the production department as VFX coordinator, then VFX producer. Those roles are very project-oriented.” Bauwens served as Visual Effects Producer on the 2012 film Rust and Bone, “an amazing experience with Cédric Fayolle, who was the VFX Supervisor and my colleague at the time. I was a VFX producer for Mikros then. It was a very challenging project, working for the first time for such a talented filmmaker, Jacques Audiard. It involved a lot of shots, the Cannes deadline, a diversity of techniques – 3D, 2D fix and practical – and the liberty with camera movement that was given to the director. Creatively, one challenging part was the animation of Marion Cotillard’s prosthesis when she arrives at the nightclub. The way she walks is telling something about her mindset, and the way to animate the prosthesis that was replacing her real legs needed to express that. Unfortunately, the film didn’t get the Palme d’Or at Cannes, but we were nominated for the VES Award for Outstanding Supporting Visual Effects in a Feature Motion Picture. We didn’t win, but it was quite an experience being in Los Angeles for our work on a feature film.”

OPPOSITE TOP AND BOTTOM: MPC Paris was the primary vendor, led by Bauwens, for multi-Academy Award-nominated Emilia Pérez, directed by Jacques Audiard. (Top photo: Shanna Besson. Images courtesy of Netflix)

In 2022, Mikros merged with MPC and Bauwens became Head of Studio for MPC Paris. In February, the Technicolor Group collapsed, sinking MPC – but not everywhere. “Depending on our location, the outcome is very different,” Bauwens remarks. In April, New York-based TransPerfect, a leading global provider of language and AI solutions for business, acquired France-based MPC and The

Images courtesy of Béatrice Bauwens, except where noted.

TOP: Béatrice Bauwens, Head of Studio, MPC Paris. (Image courtesy of PIDS-Enghien)

“It’s true that the French film industry may look a little bit shy about the use of VFX. However, it’s definitely changing. Some very ambitious projects in terms of VFX were recently made. … The ongoing evolution of the tools allows new possibilities to be offered to the filmmaker and producer, pushing the limits of our craft again. At the end of the day, it is about how to make the trick help the story.”

—Béatrice Bauwens, Head of Studio, MPC Paris

Mill. Beuwens continues in her leadership role at MPC Paris and joins the senior management team of TransPerfect Media. “I’m still in charge of MPC’s activities in France – post and VFX – and in Belgium,” Bauwens states. “The MPC banner is still used for our operations in France.”

When it comes to MPC selecting projects, Bauwens explains it’s mostly the other way around; it comes down to which projects select MPC. “Especially in Paris, thanks to our history with the French cinema, there is definitely not one type of project that we are working on. The diversity of our projects reflects this. For example, we’ve been involved with Justine Triet’s Anatomy of a Fall, which is definitely not highly intensive with VFX, and Under Paris, directed by Xavier Gens. It’s really often a question of trust –trust that MPC will bring its expertise and solutions to help deliver the project to its ultimate goal: telling a story.”

When it comes to choosing a favorite VFX shot from her career, Bauwens doesn’t single one out in particular. “One thing I know that is unique to VFX is, per show, there is always one shot that is a

TOP AND MIDDLE: Bauwens is proud of being a part of The Last Duel (2021) as Head of Visual Effects for Mikros VFX. (Images courtesy of 20th Century Studios)

BOTTOM: MPC Paris was honored with the 2025 César & Techniques Innovation prize at the César Academy in France in January. (Image courtesy of César Academy)

challenge; it may not be the most difficult one, but it will last until the end, bringing a specific difficulty, and you know when delivered, the rest of the shots are going to go well. It’s the shot that you may remember the name, like ‘070_020’, for years. And when you see the movie at the end, it goes so fast. All the work, all the worries for shots that last only a few seconds. I guess it is very specific to our VFX world where days, even months can be spent with one open shot. It’s such a different experience than being on set where, at the end of the day, you know you have filmed.”

One project, however, that Bauwens is particularly proud of is Ridley Scott’s The Last Duel. “Ridley Scott was a big step,” Bauwens acknowledges. “I wasn’t directly on the film. The VFX Producer was Kristina Prilukova. I was Head of Studio and this film would determine our future in Paris in the international landscape. Part of the work was done in MPC Montreal, and in Paris we did environments, FX and crowd work. It was one of the very first projects that triggered the 40% tax rebate bonus in France by having more than €2m of VFX in Paris. We weren’t allowed to fail. Working with Ridley Scott for our team in France was like a life goal. I think about Christophe ‘Tchook’ Courgeau, the wonderful [MPC] Head of Environment in Paris, building the Notre-Dame Cathedral in the Middle Ages for the one director who inspired him to work in this industry and visual effects. As a team in the studio, we were very proud of being part of the movie.”

Bauwens also serves as Co-Chair of France VFX. “France VFX is a trade association with 24 companies in France that are related to VFX. I co-chair this organization with Olivier Emery [Founder, CEO and VFX Producer at Trimaran]. France VFX aims to support and promote the French VFX industry. The diversity of the group that constitutes France VFX represents the diversity of our industry in France. Through this association, we can better defend

“[W]hen you see the movie at the end, it goes so fast. All the work, all the worries for shots that last a few seconds. I guess it is very specific to our VFX world where days, even months can be spent with one open shot. It’s such a different experience than being on set where, at the end of the day, you know you have filmed.”

—Béatrice Bauwens, Head of Studio, MPC Paris

the interests of the industry at national and international levels. It also allows us to promote our savoir faire to other industry associations that represent DOPs and producers. It shows that there is a strong ecosystem for VFX in France.”

Bauwens is optimistic about the future of visual effects in the French film industry. “It’s true that the French film industry may look a little bit shy about the use of VFX. However, it’s definitely changing. Some very ambitious projects in terms of VFX were recently made. Le Comte de Monte-Cristo is one good example; it was received by audiences with great success. There is also an interesting evolution of the ‘film de genre’ with films like The Substance and The Animal Kingdom [Le règne animal] where the visual effects make the story possible. The ongoing evolution of the tools allows new possibilities to be offered to the filmmaker and producer, pushing the limits of our craft again. At the end of the day, it is about how to make the trick help the story.”

Concludes Bauwens, “Georges Méliès was one of the first pioneers of visual effects. There are many factors in the French film environment that are beneficial to reinventing our craft again – the schools, the intermittent social status for artists, the ecosystem of companies that have existed for a long time and the new ones, too. France is now more a part of the global industry. These are all positive signs for the future of VFX in France.”

BOTTOM: Bauwens, left, is Co-President of France VFX, an association of French VFX vendors, and a passionate spokesperson for the benefits of utilizing French VFX in international as well as local productions.

TOP: Bauwens served as Visual Effects Producer on Rust and Bone (2012), directed by Jacques Audiard. (Photo: Roger Arpajou. (Image courtesy of Why Not Productions and Sony Pictures Classics)

GOING BEYOND WHAT WAS DONE BEFORE FOR STAR TREK: STRANGE NEW WORLDS S3

By TREVOR HOGG

Captain Christopher Pike helmed the USS Enterprise in the original pilot for Star Trek, but NBC rejected it, resulting in the name change to Captain James T. Kirk, who went beyond the realm of television and film to become a pop icon. Despite being replaced, Pike did not become a footnote but appeared in an episode of the original series and on the big screen over half a century later. Things went into hyperdrive for the Starfleet officer when a guest appearance on Star Trek: Discovery paved the way for him to reclaim leading man status with the production of Star Trek: Strange New Worlds, which revolves around his galactic expeditions on behalf of the United Federation of Planets. The third season, consisting of 10 episodes, does not shy away from exploring different genres with an irreverent wit and expanding the scope of the unexplored cosmos by utilizing virtual production.

Images courtesy of CBS Studios, Inc.

TOP: Starfleet Captain Christopher Pike (Anson Mount) views the outcome of his space battle against the Gorn from the bridge of the Enterprise

OPPOSITE TOP TO BOTTOM: Virtual production was utilized to expand the scope of the practical sets constructed for the Gorn hive environment. Practical pods were constructed with actors placed inside.

“There is a variety of different stories and approaches to things in Star Trek: Strange New Worlds,” states Jason Zimmerman, Supervising Executive & Lead Visual Effects Supervisor on the show. “They’re not afraid to try out different ideas and tell a variety of stories. It’s always cool because when you read the scripts, you may not have the bigger picture of things, and when you finish the season, you look back and go, ‘That worked great.’” The goal was to capture the spirit that Gene Roddenberry infused into his innovative space western that aired during the late 1960s. “This show is taking those classic moments and themes of the original series and bringing them into the present,” remarks Brian Tatosky, Visual Effects Supervisor. “The original series had different tones to episodes, like more serious or lighthearted. What Strange New Worlds has done is push that even farther to where we have genre

episodes within our episodes. Visual effects is about supporting those scripts. If it’s a funny episode, we need to make sure that our stuff fits. If it’s a scary episode, the sets and effects have to be as scary as possible.”

Virtual production has become a significant component of world-building. “The main difference for us on this show and on the shows where we do virtual production is we’re building something for the day we shoot,” Zimmerman states. “We’re not prepping for something that we know is coming in post. It requires more urgency and interaction with the different departments to make sure we’re aligning with what they’re planning. If you’re talking about something like an Engineering set, a lot of that is practical in terms of what they’re interacting with. The graphics, to [First Assistant Art Director: Motion Graphics] Timothy Peel and his team’s credit, are mostly practical, so we’re not planning for a lot of monitor comps later on. The most successful assets have always been those that start something practically and iterate it into a virtual asset. In that way, you’re able to hide the effect. No one knows where it starts and ends. Some of those assets are organic in nature, like the Gorn hive, which was a virtual production asset, and yet we had practical pods. They could sit in the foreground, which pushed everything away in depth and made it feel like it was all one piece, as opposed to something like Engineering, which is all hard surfaces but requires interactive lighting. It’s interesting because each one is different and custom to the story.”

Not every alien encounter is friendly. “Luckily, through our tenure on Star Trek, we have done a few space battles,” Zimmerman notes. “We have learned a lot about what to do and

To create an impression that the interior of the ancient prison was influenced by quantum physics, a constantly moving virtual background was created that goes off into the infinite distance.

not to do along the way. Fortunately, in Episode 301 with the Gorn, we have Chris Fisher directing, who has been with us since the start. He’s our EP and PD [Producing Director]. Chris loves to storyboard and interact with everybody. It’s about the prep. It’s different from a virtual production where everybody is working towards a common thing, although there was some virtual production playback hidden in those sequences. Primarily, it’s about the choreography of things and establishing a geography. We start to previs the minute we get his boards. We might even be doing previs while he’s beginning to shoot. If something comes up on set where we go, ‘They’re looking more this way,’ we can adjust our animation to match. What Chris plans typically holds, and that’s helpful for us because we’re not scrambling to try a new direction or change something in post.” There is an offshoot component associated with virtual environments. “Before even the storyboards, they can be mulling around in the creative process,” Tatosky remarks. “We can show them potential shots and layouts of where things need to go in a sequence if characters need to get from Set A to Set B. When shooting begins, they have a better idea of how the pieces fit together from day one, which means fewer shots and retakes.”

Among the threats that Pike and his crew encounter are Klingon zombies. “There are a few things in visual effects that you want to play with, and zombies are at the top of the list,” Zimmerman laughs. “Other than the shots that are obvious visual effects, which we’re either keeping out or in with a containment field or bursting into particles, all the zombies you see are special effects makeup. It was done on a virtual production asset, when they’re on top of that plateau where the shuttle lands. We had our moments where we got to play in the sandbox. You would log into QTAKE to see what they were doing on set on the day, and they were on a different planet with zombies. There was nothing we had to do later for that. The table was set for us.” The Gorns had practical and digital versions. “There was a guy in a [mocap] suit, as well as CG, for

TOP TO BOTTOM: Practical Gorns interacted with the cast while digital ones were produced for moments where they defy physics, like crawling on walls.

The exterior shots of the Enterprise in outer space were fully CG.

when they’re hanging upside down on the ceiling,” Zimmerman explains. “I’m sure the actors are so much happier having something that is live in the scene to interact with. It helps us in terms of our lighting and textures to have them all marry together. We might add a blink or some drool, but there is a nice division of labor between what we do practically and digitally that helps to sell the creatures in their environment. When you see somebody being held up by a practical Gorn, it feels so much more visceral and real. We like working that way.”

First appearing in Star Trek: The Animated Series and transitioning to live-action with Star Trek: The Next Generation, the Holodeck has a near disastrous test run that nearly kills its user and cripples the Enterprise. “The fun part is figuring out how thick you want the yellow lines to be on the Holodeck because it has changed over the show’s seasons even in Star Trek: The Next Generation,” Tatosky notes. “Then looking at the original effects of the transitions into Holodeck sets in TNG and going, ‘We want to honor that, but there has been enough time that we should upgrade these things a little bit and make them more visually complex because the viewer of today expects more than essentially a cross dissolve, which was what a lot of these effects were.’ I loved the scripting of it all, including why they’re using the Holodeck and what happens as a result. It fits into the Universe, and they get to tell a funny story with a lot of neat twists and turns that the audience will enjoy.”

Among the new environments visited by the Enterprise is an ancient prison that uses quantum physics to entrap a malevolent life force that resembles glowing fireflies. “The background was meant to move and feel infinite in the space,” Zimmerman states. “That was a virtual production asset, so it’s a perfect example of something that we started designing the minute we knew it was an idea. There are technical challenges because you’re creating a massive environment that has to move. We have to make sure

TOP TO BOTTOM: Star Trek: Strange New Worlds provided the opportunity for Starfleet Captain Christopher Pike to take center stage after the character was replaced by Captain James T. Kirk in the original series.

Storm Studios was responsible for the digital set extension of the decommissioned research facility, which resulted in the Klingon zombies.

Christina Chong as La’an, Darius Zadeh as Metron and Melissa Navia as Ortegas in Episode 309.

that it performs well on the wall. You have to make sure that it is lit properly because it has this bright backlighting, but it’s also supposed to be this moody, mysterious space as well. It was a fun one to construct because of the scope, and in our world, where we build so much in the future, this was meant to feel more ancient but still part of the Star Trek Universe.” The imprisoned life force is in a container that explodes like a flash grenade and scorches the eye sockets of a medical officer. “It’s supposed to be a horrifying moment,” Tatosky notes. “We’re not an R-rated film, but we still have to emphasize how awful it is.” Prosthetic makeup was an important component of the effect. “Blending with what was done practically was helpful to us,” Zimmerman remarks. “It saves you some wide shots and allows you to see what the light is doing near the eye. When the head turns a certain direction and it starts to fill with light, you can see that cavity more clearly.”

The 10 episodes feature between 2,000 and 2,500 visual effects shots by Ghost VFX, Storm VFX, Crafty Apes, Pixomondo, Zoic Studios, AB VFX, Cause and FX and an in-house team. “Nowadays, it’s hard to technically count because where does the work on the virtual environment and wall fit?” Tatosky observes. “Those would have been visual effects shots, but now they can point the camera almost anywhere once the environment is finished and get essentially beautiful visual effects shots in camera. It has upped the count of visual effects but in a completely different way.” Solar flares have a significant role to play in thwarting the Gorn. “I have to give credit to one of our DPs, Glen Keenan,” Zimmerman states. “I’ve probably known Glen for 15 years, and what’s fun with him is he understands visual effects, the camera and how things will end

TOP: Most of the Engineering set was practical to capture the proper interaction with cast members such as Martin Quinn as Scotty.

BOTTOM: The mantra for Star Trek: Strange New Worlds was to capture as much as possible in-camera, which meant producing visual effects elements such as motion graphics ahead of time for principal photography.

up in post so well. I lean into having good cinematography and DPs. If our work doesn’t match the lighting or if it’s not bright enough or too bright, all of those things are going to result in something that the viewer is going to catch. It’s an educated audience we have in Star Trek, and above and beyond that, in television in general. They know if it’s good visual effects or not. Having good cinematography and lighting to start with sets us on a path that is so much better than if you’re trying to fix something.”

“It’s important to give credit to Alex Wood, our Production Supervisor,” Zimmerman observes. “He’s our boots on the ground in Toronto and has been since Season 1 of Star Trek: Discovery. Alex has a great rapport with the different departments and helps us to walk through all of the meetings, shot listing, and interacting with directors in addition to Brian and me. Alex has built such a relationship with special effects and stunts that they know what we’re thinking, and we get what they’re thinking. Most of the time, we are in the ballpark when we start, in terms of the expectation for how somebody will approach something.” Another unsung hero is the in-house visual effects team. “I’m not sure we would be here without the in-house team,” Zimmerman admits. “They’re like the Navy SEALs of visual effects. Our team involves comp and CG, and has grown not only in the number of shots but also in the scope of what they’re able to take on now, finishing shots and beautiful CG things that we probably didn’t have the capacity to take on early on. They also help us with look development and setting the tone for things. When we go to the vendor, we’re not saying, ‘R&D something for us.’ We’re saying, ‘Here’s the new script and the idea. This is it in a shot. Take that and roll it into 25 shots.’”

Season 3 was about refining the virtual environment process. “We knew there was interest in doing more with that, to go to new places that we haven’t seen before, to go to more complex places that we’ve seen before and to push the wall to as close to failure as possible but still working so we can get the most detail, animation and lights in there,” Tatosky states. “We want to do better and be more creative than the season before, and do less of the fixing of the mistakes by thinking ahead.” There is no shortage of complex shots. “Just in Episode 301 alone, there are some massively long fly-throughs of the Gorn cruiser coming from outside into space, flying down essentially into the set,” Tatosky notes. “That is a mammoth undertaking to make that all feel nice and to get the lighting, speed and feeling of it all right.”

The production process has become a well-oiled machine due to the cross-pollination of filmmaking talent associated with the various Star Trek series. “Everybody is bringing that collective years of experience to the table every day,” Zimmerman remarks. “In a lot of ways, I don’t think there is anything anyone is going to come up with that will scare anybody because someone is going to go, ‘Remember when we did this?’” There is a broad range of visual effects work. “We’ve always got our Enterprise shots, which never get old,” Zimmerman reflects. “That being said, it’s nice to explore the virtual production and scope of the worlds we’re building, and the creatures have been satisfying. We always get there, and it always works out in a good way. It’s not like we just get it done. It’s always something we’re proud of by the end of the season.”

TOP TO

The design challenge for the ancient prison was to emphasize a sense of history rather than futurism while still fitting within the Star Trek Universe.

Prosthetic makeup and visual effects were combined to create believable scorched eye sockets.

Motion graphics are a major on-set component are produced by Timothy Peel.

BOTTOM:

NEW TOOLS KEEP EXPANDING THE CANVAS FOR TODAY’S MATTE PAINTERS

By CHRIS McGOWAN

Matte painting for movies has been around since Norman Dawn’s 1907 documentary Missions of California. Since then, innumerable films have utilized the technique to provide background sets and settings – works such as Ben-Hur, King Kong, The Wizard of Oz, Citizen Kane, Mary Poppins and Raiders of the Lost Ark are just a few spectacular examples. Originally consisting of painting on glass, matte painting began the big shift to DMP (digital matte painting) with 1985’s Young Sherlock Holmes and other films in the 1980s and ’90s, with DMP ruling the 21st century.

Matte painting is still widely used but has evolved. “It’s now often integrated into the 3D workflow – used for paint-overs, environment extensions or background plates. Fully 2D or 2.5D matte paintings are becoming rarer, but they remain a cost-effective solution when applied strategically,” states Charles-Henri Vidaud, Head of Environments at Milk VFX.

TOP: Raynault Founder Mathieu Raynault worked on matte painting for Matrix Revolutions. (Image courtesy of Warner Bros.)

OPPOSITE TOP TO BOTTOM: ILM’s Timothy Mueller worked with VFX Art Director Yanick Dusseault to create the desert planet Jakku in Star Wars: The Force Awakens (Image courtesy of ILM and Lucasfilm Ltd.)

Milk VFX’s Charles-Henri Vidaud created the matte painting of the planet Morag for Avengers: Endgame for Cinesite. (Image courtesy of Marvel Studios and Walt Disney Studios)

Frameless Creative teamed with Cinesite and its partner company TRIXTER to create a permanent immersive art exhibition in London. The many artworks include this painting by renowned 18th-century Venetian painter Canaletto, known for his iconic views of the Grand Canal in Venice. (Image courtesy of Antonio Pagano, Cinesite and Frameless Creative)

Vidaud reflects, “I started in the industry 25 years ago doing storyboards, so transitioning into matte painting was a natural next step. It allowed me to combine composition, lighting and storytelling on a broader canvas. One of the most iconic matte paintings I created was for Avengers: Endgame while at Cinesite – the shot where the Benatar spaceship lands on planet Morag. That environment was originally designed by MPC for Guardians of the Galaxy, but I had to recreate it from scratch to fit a different time of day and camera angle. It was both technically demanding and creatively rewarding. Other highlights include Black Widow and Assassin’s Creed.”

“Matte painting remains a vital and evolving art form in the film, television and gaming industries,” remarks Timothy Mueller, Senior Generalist Artist at ILM. “While traditional painting skills continue to provide the foundation – mastering composition, lighting, perspective and storytelling – today’s matte painters must also be proficient with cutting-edge digital tools and workflows.” Mueller adds, “Despite rapid technological progress, the core challenge stays the same: crafting believable worlds that support the narrative and evoke emotion. Matte painters are storytellers, visual architects who help transport audiences to places both fantastical and grounded in reality.”

Like many in the field, Mueller began with a foundation in traditional art. “That path eventually led me to the world of visual effects, which had long fascinated me, especially the groundbreaking work of the artists and technicians behind George Lucas’s original Star Wars films. My first film credit as a matte painter came on the Mark Wahlberg football movie Invincible, where I worked at Matte World Digital alongside the Academy Awardwinning visual effects supervisor and author of The Invisible Art, Craig Barron, VES, and senior art director Chris Evans.” Currently, being part of ILM provides Mueller with “the opportunity to work on a wide variety of high-quality projects in the visual effects industry. One of the highlights of my career was working on my first Star Wars film, The Force Awakens, where I helped bring J.J. Abrams’ unique vision of the Star Wars Universe to life. Collaborating closely with VFX Art Director Yanick Dusseault, we created distant worlds across the galaxy, from the desert planet