24

Visual Artists' News Sheet | March – April 2018

Residency

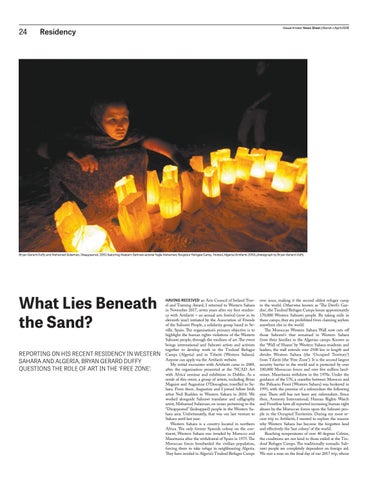

Bryan Gerard Duffy and Mohamed Sulaiman, Disappeared, 2010; featuring Western Sahrawi activist Najla Mohamed, Boujdour Refugee Camp, Tindouf, Algeria (Artifariti 2010); photograph by Bryan Gerard Duffy

What Lies Beneath the Sand? REPORTING ON HIS RECENT RESIDENCY IN WESTERN SAHARA AND ALGERIA, BRYAN GERARD DUFFY QUESTIONS THE ROLE OF ART IN THE ‘FREE ZONE’.

HAVING RECEIVED an Arts Council of Ireland Trav-

el and Training Award, I returned to Western Sahara in November 2017, seven years after my first residency with Artifariti – an annual arts festival (now in its eleventh year) initiated by the Association of Friends of the Sahrawi People, a solidarity group based in Seville, Spain. The organisation’s primary objective is to highlight the human rights violations of the Western Sahrawi people, through the medium of art. The event brings international and Sahrawi artists and activists together to develop work in the Tindouf Refugee Camps (Algeria) and in Tifariti (Western Sahara). Anyone can apply via the Artifariti website. My initial encounter with Artifariti came in 2009, after the organisation presented at the ‘NCAD Art with Africa’ seminar and exhibition in Dublin. As a result of this event, a group of artists, including Brian Maguire and Augustine O’Donoghue, travelled to Sahara. From there, Augustine and I joined fellow Irish artist Neil Rudden in Western Sahara in 2010. We worked alongside Sahrawi translator and calligraphy artist, Mohamed Sulaiman, on issues pertaining to the “Disappeared” (kidnapped) people in the Western Sahara area. Unfortunately, that was our last venture to Sahara until last year. Western Sahara is a country located in northern Africa. The only former Spanish colony on the continent, Western Sahara was invaded by Morocco and Mauritania after the withdrawal of Spain in 1975. The Moroccan forces bombarded the civilian population, forcing them to take refuge in neighbouring Algeria. They have resided in Algeria’s Tindouf Refugee Camps

ever since, making it the second oldest refugee camp in the world. Otherwise known as ‘The Devil’s Garden’, the Tindouf Refugee Camps house approximately 170,000 Western Sahrawi people. By taking exile in these camps, they are prohibited from claiming asylum anywhere else in the world. The Moroccan Western Sahara Wall now cuts off those Sahrawi’s that remained in Western Sahara from their families in the Algerian camps. Known as the ‘Wall of Shame’ by Western Sahara residents and leaders, the wall extends over 2500 km in length and divides Western Sahara (the ‘Occupied Territory’) from Tifariti (the ‘Free Zone’). It is the second largest security barrier in the world and is protected by over 100,000 Moroccan forces and over five million landmines. Mauritania withdrew in the 1970s. Under the guidance of the UN, a ceasefire between Morocco and the Polisario Front (Western Sahara) was brokered in 1991, with the promise of a referendum the following year. There still has not been any referendum. Since then, Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch and Frontline have all reported increasing human right abuses by the Moroccan forces upon the Sahrawi people in the Occupied Territories. During my most recent trip to Artifariti, I wanted to explore the reasons why Western Sahara has become the forgotten land and effectively the ‘last colony’ of the world. Reaching temperatures of over 40 degrees Celsius, the conditions are not kind to those exiled at the Tindouf Refugee Camps. The traditionally nomadic Sahrawi people are completely dependent on foreign aid. We met a man on the final day of our 2017 trip, whose