&Round Towers High Crosses The County Down of A

Field Guide

Peter Harbison

With contributions from Ian Meighan

A Down County MuseuM PublICAtIon

The High Crosses and Round towers of County Down A Field Guide

Peter Harbison

Down survey 2014

All rights reserved. text by Peter Harbison and contributions from Ian Meighan Isbn no. 978-0-9927300-1-7

Designed by April sky Design, newtownards www.aprilsky.co.uk Printed by ??????????

Published by Down County Museum

Front cover images: Donaghmore High Cross and nendrum Round tower. Images inside front cover: Kilbroney High Cross, Drumbo Round tower, Maghera Round tower and Dromore High Cross.

back cover: Downpatrick High Cross (Photograph: tony Corey).

2

Table of Con T en T s

Preface by Margaret Ritchie MP

3

........................................................................

5

........................................................................................................

....................

....................................................................................................

.......

.............................................................................................

...........................................................................................

Downpatrick High Crosses .............................................................................. 32 Drumgooland/Drumadonnell High Crosses ................................................. 42 Maghera Round tower ..................................................................................... 45 Kilbroney High Cross ....................................................................................... 47 Donaghmore High Cross ................................................................................. 52 Dromore High Cross......................................................................................... 60 Drumbo Round tower ..................................................................................... 64 nendrum Round tower ................................................................................... 66 Acknowledgements ........................................................................................... 71 select bibliography ............................................................................................ 71

High Crosses

9 The Granitic High Crosses of County Down by Ian Meighan

19 Round towers

21 The Geology of the Round towers of County Down by Ian Meighan

25 other Monuments

27 The tour

29

Preface

By Margaret Ritchie MP

Ihave known for a long time that County Down, and south Down in particular, is special… a land steeped in history and rich in heritage.

In particular, the story of Christianity in Ireland begins, blossoms, and finds its home in the Downpatrick/lecale area where saint Patrick first arrived in Ireland to begin his astonishing lifelong mission. There is nothing I would recommend more strongly to the visitor to County Down, than to go and walk in the footsteps of st Patrick by visiting the many historic and atmospheric Patrician sites in this area, especially saul Church, Inch Abbey, struell wells and Down Cathedral and graveyard.

I would also highly recommend to visitor and local resident alike, to go to many of the sites detailed in this book because although little remains of the built heritage of Patrick’s time of the 5th century, the wonderful monastic site at nendrum, the High Crosses of the 9th and 10th centuries and the round towers dating from that period onward are the built heritage treasures that remain from our early Christian tradition.

And make no mistake, these are built heritage treasures. not just because they reflect our early Christian history, but also because they are our oldest surviving architecture of any kind.

And they are also very much worth seeing: I mentioned nendrum and Inch especially – the site of the Maghera round tower and old church is beautiful and evocative too. see it on a clear evening when slieve Donard is in full view.

I want to congratulate the author, Peter Harbison, and everyone who has helped to produce this publication, for drawing important historic information together and promoting our heritage assets to the wider public. I am pleased also that the Downpatrick High Cross has its future secure in the shelter afforded by the nearby Down County Museum, and I pay tribute

5

to the excellent archaeological and conservation work in which the Museum is a key player.

I also want to sound a slight note of concern. It is worth noting that of our remaining round towers, none retain their original conical roofs or their height. A few of them are not much more than stumps. There has also been a neglect of our high crosses over the centuries. This is true right across the island and I do believe that Government authorities north and south must commit more resources to preserving our early Christian built heritage assets and their surrounding sites. we have a duty to protect these places for future generations while making them accessible to people in the present. The Museum’s publication serves both of these objectiveshighlighting the condition of the assets while making them accessible and interesting for visitors.

I thoroughly recommend that readers of this book take up the opportunity presented inside, and go on the tour of County Down’s High Crosses and Round towers as outlined.

Visitors who do the tour will be rewarded with an appreciation of some fascinating structures in inspirational locations. locals may also increase their appreciation of the fact that we have inherited great treasures in this area. treasures from our past which are undoubtedly, in some way, part of what we are today.

6

The h igh Crosses and r ound Towers of Coun T y d own: a f ield g uide

[Map 1: County Down, showing symbols for High Crosses and Round towers].

The High Crosses and Round Towers of County Down.

7

8

The high Crosses and round Towers of CounTy down: a field guide

The mouth of the Slaney River, where St Patrick is said to have arrived in County Down in 432 AD.

HIGH CRosses

saint Patrick may well have been the first person to bring a cross to County Down. Certainly, he is the one who is given credit for having been the first Christian missionary in the area, sometime in the fifth century. His biographer, Muirchú, writing some two hundred years after his death, tells us that he landed at Inber Slane, probably on the estuary of the modern river slaney, and converted the local chief, Díchu, who lived ‘where st. Patrick’s barn is now’. After visiting his old master on slemish Mountain in the neighbouring county of Antrim to the north, he returned to County Down, and set about his missionary activity in lecale, the south-eastern part of the county, an area which Muirchú says that he especially favoured. no one knows exactly where st. Patrick’s body lies, but saul – which gets its name from the old Irish word for a barn – has often been claimed as his burial place, rather than Armagh, arguably his most important foundation, which would dearly love to have been able to claim his relics. Downpatrick laid claim to his grave as early as the seventh century, though his name only came to be associated with the place in the twelfth century. The large stone bearing his name to the south of the Cathedral was only placed there just over a century ago without pretending to indicate precisely the saint’s last resting place. sadly, we have neither buildings nor genuine relics that we can reliably link directly with the saint, nor can any known buildings be dated to his lifetime in the fifth century. but what we do have are his writings, particularly his Confessio, which shows him to have been a humble man with a marvellously deep faith in his God, whose Gospel he successfully preached to the Irish. The church which Patrick organised on the ground was probably episcopal, of the kind that he had known in his british homeland during the dying days of the Roman empire. A bishop named Fergus, whose death was recorded in

9

Saul Church, the site of St Patrick’s first barn-church.

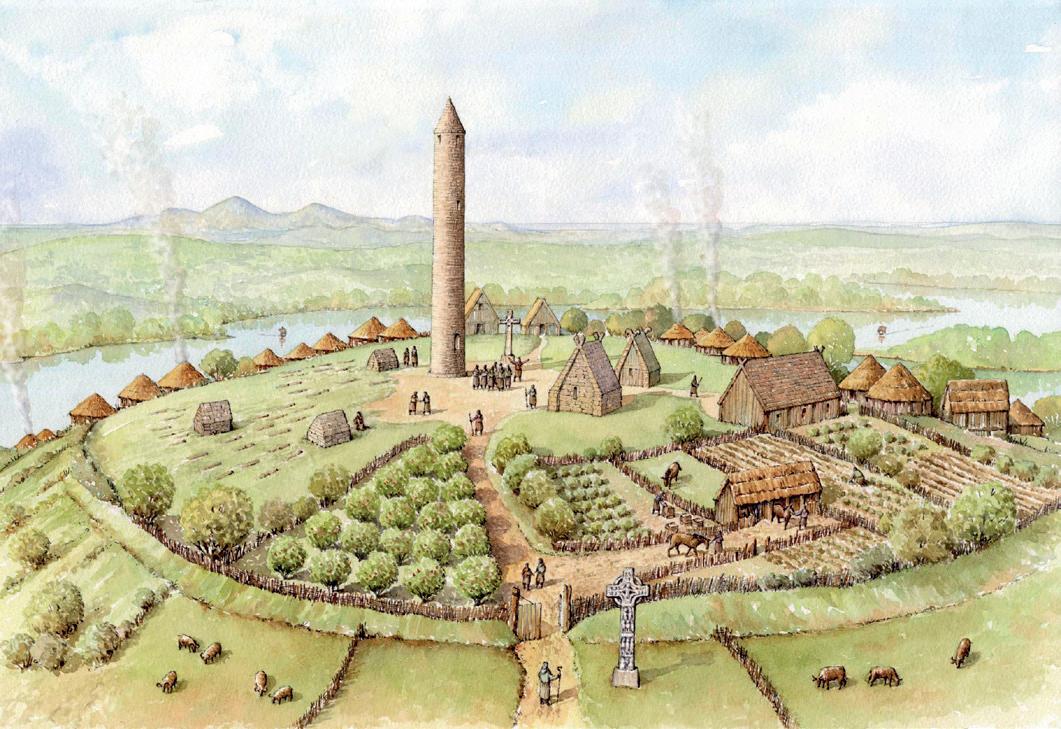

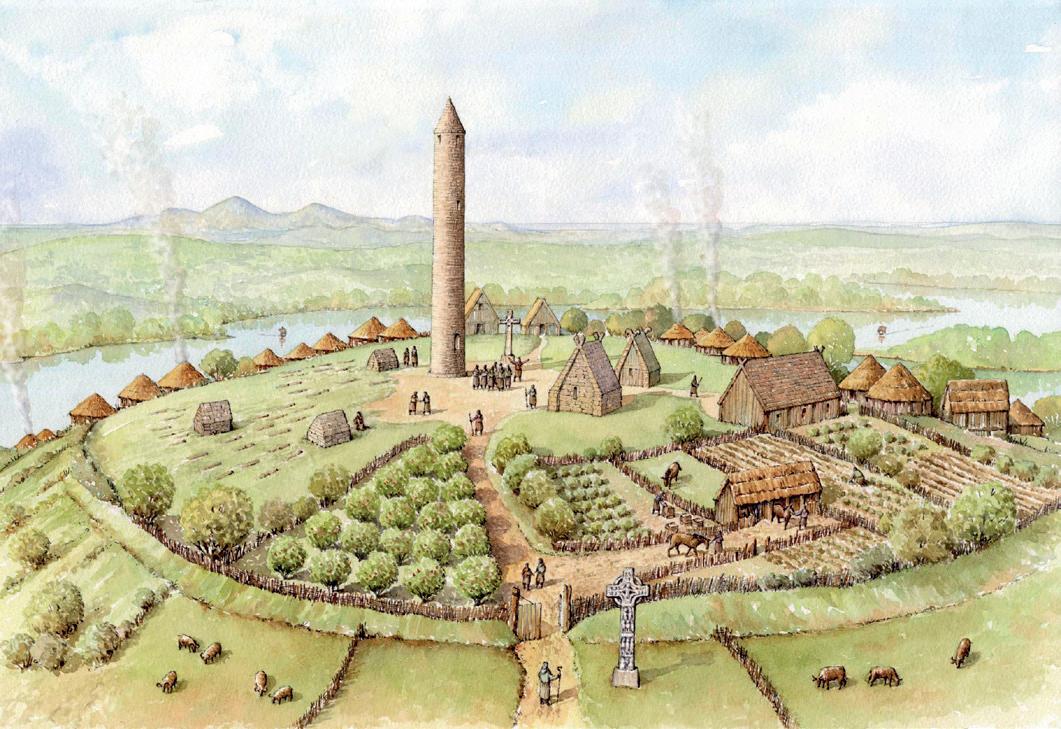

the year 584, would have held a see which the national Apostle would have created in what is now Downpatrick, but which formerly bore the name Dún Leth-glaisse. This suggests that a pagan fortification once three-quarters surrounded by water was peacefully transformed into a Christian bishopric. However, the sixth century is characterised by the rise and spread of monasteries great and small throughout the length and breadth of Ireland. In time they became the main focus of religious and cultural activity, as well as the writing of history by keeping annals telling of events that happened year by year. b ecause of its three roughly concentric walls, the monastery of nendrum on strangford lough is widely taken as the model which shows us how at least some of these early monasteries may have been divided up into three separate areas. A central area was for the church and Round tower, a middle one was for the monks to live and work in, and the outermost one was for crops and garden produce. lawlor’s excavations there in the 1920s brought a number of cross-decorated stones to light, of a kind found in various forms on many other monastic and even non-monastic sites (such as saul) in County Down These small monuments have now, in many cases,

10 The h igh Crosses and r ound Towers of Coun T y d own: a f ield g uide

11 h igh Crosses

The monastery of Nendrum, photographed from the air. (Courtesy of the Northern Ireland Environment Agency)

Artist’s impression of the monastic site of Nendrum in about ? AD. (Courtesy of the Northern Ireland Environment Agency)

been moved into museums for protection – the ulster Museum in b elfast, the Down County Museum in Downpatrick and the newry and Mourne Museum in newry. some of the nendrum examples are displayed in the small Heritage Centre on the site.

For a monastery of its apparent importance, it is surprising that nendrum has produced no High Crosses that we know of – and the same applies equally to Movilla near newtownards. It is one of the chief churches of the ancient ulaid people which – other than a single cross-decorated stone – has very little to show for its former significance in early medieval Ireland. The only monumental remains of one of the most literary and best-documented of all the early Down monasteries, that at bangor near b elfast lough, are an ancient sundial in a local park and the fragment of a cross-shaft two and a half feet high built into the wall of a private chapel on the Clandeboye estate, where a double-strand interlace looks out at us on the only visible side. It is the privilege of Downpatrick to have produced more High Crosses than any other location in the County, doubtless because this was the centre of power of the Dál Fiatach tribe, pre-eminent in south Down in the eighth and ninth centuries. Inscriptions found on crosses in the midland county of offaly have been shown in recent decades to contain the names of kings of Ireland and, although no inscriptions are known from ulster crosses, we should perhaps envisage the possibility of political involvement in the commissioning of stone crosses in the province, particularly in a regal centre like Downpatrick. such a consideration could also apply to the cross at Dromore, now the centre of a diocese but, over a thousand years ago, the capital of the uí echach Cobo who controlled the upland centres of central and western Down, just as the Dál Fiatach were the lords of the more low-lying coastal area of the county stretching from Carlingford to b elfast lough. The locations of other High Crosses in the County are explicable because they have had religious associations for well over a thousand years. Donaghmore, for instance, contains the element Domnach, or sunday in Gaelic, which is undoubtedly one of the oldest Christian place-name elements in Ireland, going out of use in the naming of sacred places as early as the seventh century. Kilbroney is named after st. brónach, whose dates are unknown, but the ninth-century cross described below suggests the existence of a convent there at that time.

12 The h igh Crosses and r ound Towers of Coun T y d own: a f ield g uide

Donaghmore High Cross

More difficult to explain is why Drumgooland (Drumadonnell) and Clonlea have High Crosses, whereas high status monasteries such as Movilla and nendrum do not. we do not even know where the Drumgooland cross originally stood – in Deehommed, Drumgooland or Drumadonnell ? –none of which has any known early connections. The same also applies to Clonlea, not far from newry, where probably two of the three standing crosses are likely to be ancient. yet nothing is known of the history of the site which, however, has served as a graveyard for some considerable time. what unites almost all of the County Down crosses, in contrast to most other areas of the whole island (except for the barrow valley), is the material from which they were carved, namely granite. This is not to say, however, that they were the product of one and the same stone quarry. The noted geologist Ian Meighan, who has kindly examined all of the crosses, and whose detailed geological report is appended to this section, has shown that the granite crosses come from two distinct geographical areas, the Mournes

13 h igh Crosses

and somewhere near newry, though the locations of the actual quarries (if they still survive) have yet to be established. This would imply that none of the crosses was actually erected close to where the stone was quarried but, equally, it means that – with the possible exception of bangor (probably of sandstone) – the stone for the granite crosses need not have been brought more than twenty miles or so from the source of their material. nevertheless, use of the local granite made it more difficult for the sculptors to attain a finesse of modelling in their carvings of the human figure. It was a stone better suited to the carving of geometric patterns and interlace – and less liable to erosion.

High Crosses get their name because that is how they were described by the Annals of the Four Masters in the tenth and eleventh centuries when mentioning one at Clonmacnois. but their origins go back beyond that. we may take it as certain that the stone crosses we see today were preceded by wooden examples which were probably erected as early as the seventh or eighth century in Ireland, at a time when stone crosses were being erected in england. Few of the Irish crosses can be dated as early as that, though one example at toureen Peakaun in tipperary bears lettering akin to that used on the eighth-century Ardagh Chalice, and clearly copies in stone certain techniques used by carpenters in wood.

In Ireland, it was seemingly the ninth century which saw the erection of most of the surviving crosses – except for some (including two at Downpatrick, as we shall see below) which belong to the twelfth. The area around Clonmacnois on the shannon may have been one of the first in Ireland to produce stone crosses (and pillars) with carving in relief and bearing a variety of geometrical ornament. It was not until around 880 that we see the climax of High Cross carving with some of the truly great crosses in the midlands and east of the island, such as those at Monasterboice in County louth. but, at the same time, such scriptural crosses made their mark in ulster, not just in the major examples at Armagh and Arboe, Co. tyrone, but also in County Down at Downpatrick and Donaghmore.

In the absence of inscriptions on the ulster crosses (though these could have been painted on only to fall a prey to the Irish weather in the meantime), we cannot say who it was who set them up – cleric or layman – or who carved them, monk or professional mason. where inscriptions occur on english

14

The h igh Crosses and r ound Towers of Coun T y d own: a f ield g uide

Arboe High Cross.

crosses, they tend to be placed at eye level to facilitate reading by those standing in front of them. The Irish crosses, in contrast, have their inscriptions at the bottom of the shaft, where they could most easily be seen by those praying on their knees in front of the cross. This would suggest that one of the reasons for erecting High Crosses was to provide a focus for people to pray. The crosses with scriptural scenes could be taken as bibles in stone, the varying selection of old and new testament panels carefully chosen to illuminate and explain doctrines of the Church. They were placed in frames on the faces and sides of the cross, almost like a modern comic strip, to provide visual aids for what was probably at the time a largely unlettered and illiterate public. These would almost certainly have been made more attractive by the addition of colouring, not a trace of which, sadly, has managed to survive a thousand years of exposure to the Irish climate. encouraging piety and prayer was, however, probably not the only reason why such crosses were erected. There is no evidence that they functioned as grave memorials as their modern counterparts do, but some may have been put up to commemorate events or people, even if they give us no clue as to who or what was being celebrated or remembered. others may have marked boundaries within or outside ancient monastic enclosures. whatever the reason for their creation may have been, they are one of the great glories of early Christian Ireland. some of them were so important as to make a very noteworthy and unique contribution to the sculpture of europe towards the end of the ninth century, and were worthy to be placed alongside the somewhat earlier book of Kells which could be seen as being something of a monastic miracle.

The Down crosses may generally be divided into two categories – those with, and those without, biblical sculpture. both may be fitted into the ninth century, with the two main biblical crosses – Downpatrick and Donaghmore – being probably towards its end. Those without biblical figures are decorated with geometrical patterns among others which, however, have the disadvantage that they are not easy to date, but are unlikely to be very much earlier or later than the biblical examples. The exceptions among the crosses with figure sculpture are the two small examples built into a wall in the Cathedral in Downpatrick, which are twelfth-century in date. Though their small size scarcely merits their being called High Crosses, they are included here because of their style and ringed head.

16

The h igh Crosses and r ound Towers of Coun T y d own: a f ield g uide

The ring is not an Irish – nor a scottish – invention. The earliest known use of the ring around the junction of arms and shaft of a cross is found on a Coptic textile of the fifth or sixth century now preserved in Minneapolis Institute of Arts in the usA. but, in contrast to the parallel sides of its arms, most Irish crosses (including some in Down) have a circular narrowing on the upper and lower sides of the arms, the first instance of which appears to be on the manuscript known as the Dagulf Psalter now in the national library in Vienna, dating from around 795. The application of this feature to a free-standing cross may, thus, not have taken place much before the reign of Charlemagne on the Continent. Indeed, because of the danger of cracking the stone by boring a hole through its thickness from both sides in order to differentiate the ring from the shaft and arms, as on the Donaghmore cross, it is unlikely that stone was the first material on which the use of a ring on a cross was practised. The ring nevertheless had a practical purpose of preventing the heavy arms from snapping off. In addition to this structural function, the ring surrounding the Christ figure must also have had a symbolic significance which, at least in the case of the scriptural crosses, was probably cosmic, as early Christians would have seen the Crucifixion of Christ as the central, and literally the most crucial, event in the history of the universe. This interpretation seems to have more in its favour than seeing the ring (as some have done) as a Christian version of the laurel wreath draping the heads of Roman emperors as their outward sign of victory, or as a relict of the old pagan sun-symbol, given that Christianity may have been in Ireland for more than four centuries before the ring form was adopted as a popular and recognisable symbol.

17 h igh Crosses

A cross illuminated in the Dagulf Psalter (Cod. 1861, f. 67, courtesy of the Austrian National Library, Vienna).

A ringed cross on a fifth- or sixth-century Coptic textile from Egypt (Artist: unknown, Coptic, 5th-6th century; sanctuary curtain, linen, wool, tapestry weave; Minneapolis Institute of Arts, The Centennial Fund: Aimee Mott Butler Charitable Trust, Mr. and Mrs. John F. Donovan, Estate of Margaret B. Hawks, Eleanor Weld Reid. 83.126).

18

The h igh

Crosses

and r ound Towers of Coun T y d own: a f ield g uide

The Granitic High Crosses of County Down

By Ian Meighan

The granitic High Crosses of County Down utilised material from two very different local sources: the c.412 million years (Ma) newry and younger (56Ma) Mourne Mountains masses. The newry Complex comprises three granodiorite intrusions (extending from slieve Croob through Rathfriland and newry to slieve Gullion), whereas in the Mourne region there are three granite bodies in the eastern centre (G1, G2,G3) with two more (G4,G5) in the western one.

Tertiary Igneous Complexes

Cloghoge granodiorite pluton Newry granodiorite pluton Rathfriland granodiorite pluton Hawick Group Silurian Faults

Newry Igneous Complex

Gala Group

19

10km 0

Newry

Map 2. Simplified geological map of the Newry Igneous Complex (3 granodiorites) and Mourne Mountains (5 granites) Mourne Mountains G1 G2 G3 G4 G5

N Slieve Croob Castlewellan Maghera Newcastle Rathfriland

Slieve Gullion

on the basis of mineralogy/texture, each individual Mourne granite can be identified in the field or on site and, in some cases, even further sub-division can be achieved (e.g. coarse-grained G2). For example the millstones excavated from the tidal mill at nendrum appear to have been taken from an outcrop of fine-grained G2 in the upper reaches of the bloody bridge River in the eastern Mourne Mountains. by contrast, the individual newry intrusions cannot be characterised by eye in this way. nevertheless, it is normally easy to distinguish newry from Mourne granite. on a broader scale, no two Irish granites generally look alike. table 1 pinpoints the main differences between newry and Mourne granites. table 2 presents the granite sourcing of the High Crosses.

In the future it is hoped to achieve more precise sourcing of the High Cross granite types by measuring their trace element concentrations. This will be done non-destructively on-site, using a portable, battery-operated, hand-held X-ray spectrometer. The results may enable exact source localities to be established in some cases.

Table 1 Newry- Mourne granite distinction

Newry Mourne

Newry is granodiorite (white plagioclase feldspar dominant)

Colour

Newry has a higher content of dark- coloured (iron-bearing) minerals, so

Enclaves

Newry can contain dark inclusions (enclaves)

Mourne is granite (pink alkali feldspar dominant)

Mourne appears ‘lighter’(the dark, smoky quartz of some Mourne granites does not feature here as quartz is an iron-free mineral).

Mourne lacks these.

Foliation

Druses

Newry can show a pronounced ‘mineral alignment’ (foliation)

Newry lacks these.

Mourne does not.

Mourne can have irregularlyshaped gas cavities (druses)

20

The h igh Crosses and r ound Towers of Coun T y d own: a f ield g uide

Table 2 Granite High Crosses of County Down

Downpatrick

Kilbroney

Mourne – head/shaft/socket stone (coarse-grained G2 Outer)* and Newry (modern pyramidal section)

Mourne (G5?: socket stone G4)

Donaghmore Newry

Dromore Newry

Drumadonnell Mourne (G2)

Clonlea (3 crosses) Newry and Mourne**

*The replacement High Cross (2014), outside Downpatrick Cathedral is Mourne fine-grained G2 Inner.

** The northern and central crosses are newry granodiorite: the southern one is probably Mourne granite (G2?), whereas its immediate base is newry granodiorite. n.b. The individual components of the High Cross (head, shaft, base) can have different constructional ages.

21 round Towers

RoUnD ToWeRs

along with the High Crosses, Round towers are amongst the most characteristic monuments to have survived on the sites of Ireland’s early monasteries. It comes as no surprise, therefore, that both of these monument types were adopted as symbols with the rise of Celtic nationalism in the mid-nineteenth-century. This phenomenon is witnessed by the number of headstones carved in the shape of ringed crosses, and the Round tower completed in Glasnevin Cemetery in 1869 to house the body of Daniel o’Connell in its crypt. ever since George Petrie published his famous essay on the subject in the Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy in 1845, debate has been raging about the function of these towers. The old Gaelic word for them was cloigtheach, or bell-house, suggesting a connection with bells or with one particular bell, and a potential derivation from the Italian campanile. what has fuelled the controversy is the placing of the doorway ten or more feet above the ground. In the nineteenth century, it was thought that this was to provide a speedy retreat and refuge for the monks from invading Vikings. but the first reference to such a tower in Ireland – the collapse of that at slane in Co. Meath – dates from 950, after the worst devastation of the norsemen had passed, though this by no means excludes the possibility that the towers could have been started a century or so earlier. one possible explanation for the raised entrance is that the tower could have been the monastic treasury containing relics of the founding saint and other valuable relics and manuscripts, which were best kept out of reach of the hands of avid pilgrims by placing them high enough above the ground where these treasures could, if necessary, be seen but not touched. If a bell had been one of the contents, it may have been difficult to ring it outside one of the four windows on the top of the tower because of the difficulty of stretching an

22

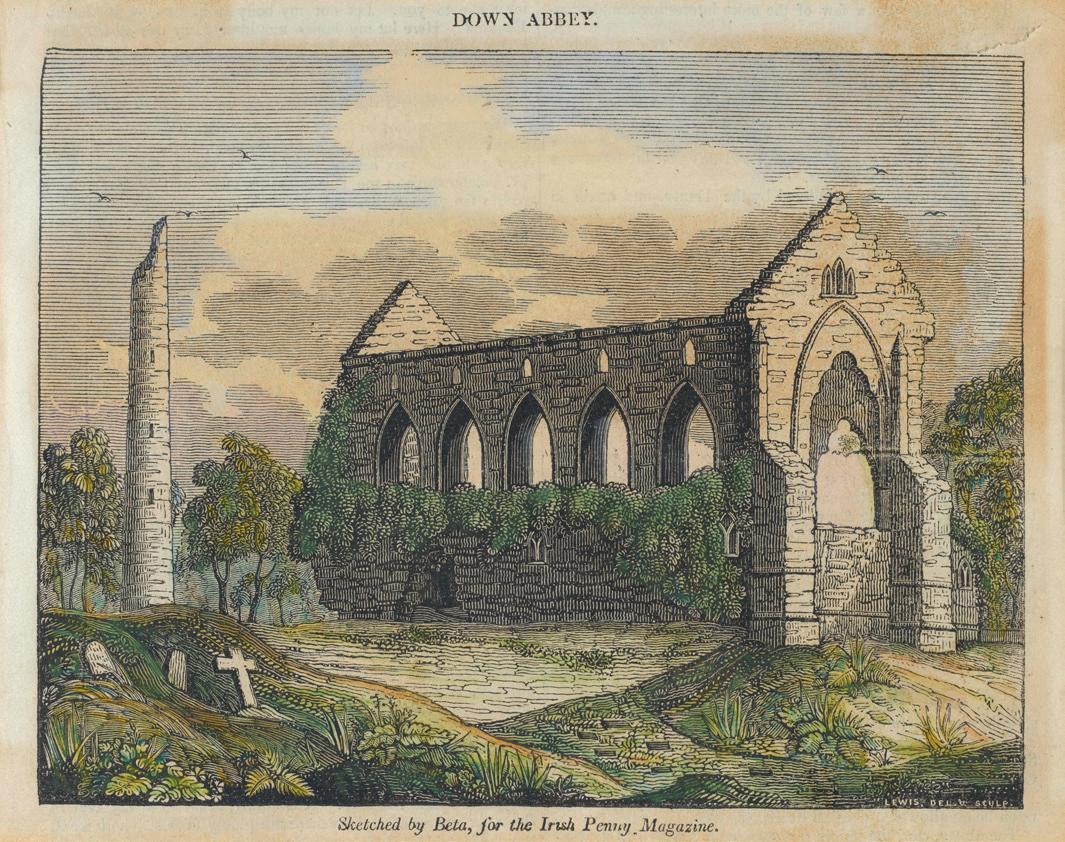

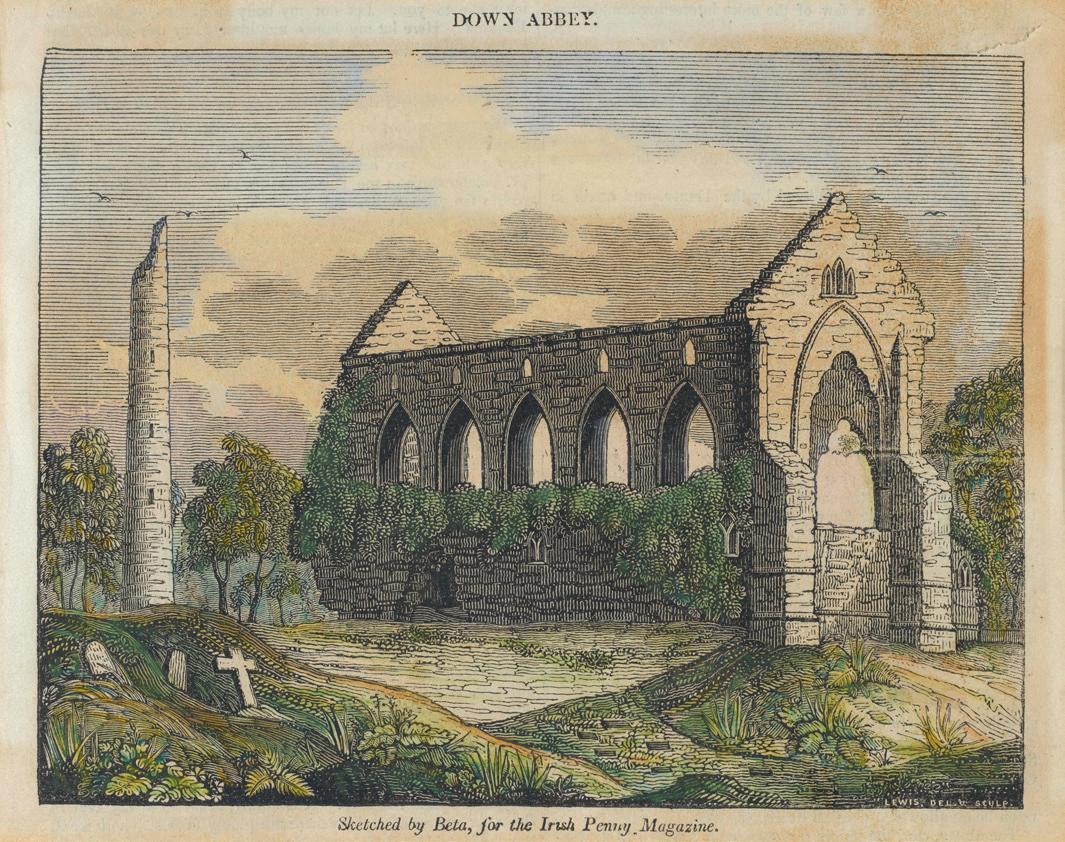

An engraving of Down Cathedral and Round Tower (Down County Museum Collection). arm far enough out to be able to do so – leaving us with the conundrum as to why the ancient Irish called them ‘bell-towers’.

About 65 such towers are known, though only a few retain their original height of anything up to 100 feet or more. b eing so tall, their tops at least must

23 round Towers

The Hill of Down as it may have appeared in about 1000 AD (painting by Philip Armstrong).

have been visible above the trees and scrub of the medieval landscape, so that they could also have functioned as beacons indicating to any travelling monk or lay pilgrim, where their goal lay if they wanted to venerate the relics of the founder of the monastery. sadly, none of the three existing towers in County Down has been retained to their full height. That at nendrum is one of these. Another is at Maghera, some ten miles from Downpatrick. st. Domangard, an episcopal disciple of st. Patrick, who allegedly died in 507, is said to have founded a monastery here in the shadow of slieve Donard, of which, however, the Round tower is the sole surviving monumental remnant. we know of one other Round tower in the County which stood not far from the southwestern corner of Downpatrick cathedral. when it was demolished for safety reasons around 1790, it was preserved to a much greater height than the other three (66 Irish feet = 84 statute feet), even though its conical cap was already missing, which would have added another ten feet to its height. Its major distinguishing feature was that, along with the tower on scattery Island in the shannon estuary, it was the only one to have had its doorway at ground level. why it should have differed in this respect from almost all the other examples must remain a matter of speculation.

igh

ound Towers of Coun T y d own: a f ield g uide 24

The h

Crosses and r

Maghera Round Tower.

The stump of Nendrum Round Tower.

The Geology of the Round Towers of County Down

By Ian Meighan

Irish Round towers still retain an element of mystery regarding their exact number and functions. Geoarchaeologically, however, one can generalise that they tend to have been constructed from locally available (including glacially-transported) rock materials. table 1 provides geological information for the Round towers at nendrum, Drumbo and Maghera.

Interestingly, Nendrum and Drumbo (respectively NE and N of Slieve Croob, Map 2) lack granite outcrops in their immediate vicinity and do not contain this lithology. Both are on Silurian Gala Group bedrock. By contrast, Maghera, situated on (unexposed) Silurian Hawick group bedrock between the Newry and E Mourne granitic bodies (Map 2), has quite abundant Newry granodiorite material. This is in a water-rounded form and undoubtedly reflects initially angular fragments transported by Pleistocene ice which moved from NE to SW in this region. However, Mourne granite fragments would not have been carried northwards by ice to the Maghera area: it is also significant that the spectacular Slidderyford Neolithic Dolmen (portal tomb), just over 2 km E of Maghera, involves only glacially transported Newry granodiorite (3 large fragments) as well as Silurian rock, but no Mourne granite material.

The lithology of these monuments reflects their local Geology, e.g. the proliferation of Lower Palaeozoic (probably Silurian) greywacke sandstones/siltstones. The absence of granite at Nendrum and Drumbo is also noteworthy in this context. The abundance of water-rounded Newry granodiorite boulders at Maghera undoubtedly indicates material which was initially transported by Pleistocene ice as angular fragments derived from the nearby Newry Igneous Complex.

25

nendrum

Lower Palaeozoic greywacke sandstone (+siltstone)

Red sandstone (PermoTriassic) Granite, basalt/ dolerite

Some waterrounded material

Drumbo

Lower Palaeozoic greywacke sandstone

Siltstone (Lower Palaeozoic) quartz-rich sandstone (Carboniferous ?), vein quartz

Granite, dolerite

Very little waterrounded material

Maghera

Lower Palaeozoic siltstone (+greywacke/ slate)

Downpatrick No original material survives in situ

Newry granodiorite (quite abundant), Mourne granite (G2) (rare), microgranites, basalt

Dolerite Water-rounded material present (e.g. Newry granodiorites)

26

The h igh Crosses and r ound Towers of Coun T y d own: a f ield g uide

Round Tower Principal rocks subsidiary rocks absent rocks

nature of rock fragments

Table 3 The Geoarchaeology of County Down Round Towers

oTHeR MonUMenTs

In addition to High Crosses and Round towers, the other significant stone monuments to be preserved on the sites of Down’s early Irish monasteries are, of course, the stone churches. These, however, are comparatively small in size (scarcely reaching a length of more than 26 feet), of which the most typical examples are those at Derry on the Ards Peninsula and st. John’s Point on the coast south of Downpatrick, though at least the foundations of another survive at nendrum. It is noteworthy that only a single stone found at Downpatrick gave proof of the existence of churches in the County built in the Romanesque style typical of the twelfth century in many parts of Ireland. This suggests that the simple stone churches, of the

27

The early eleventh century church at St John’s Point in Lecale.

kind just mentioned, may have continued to be built at least up to the time that st.Malachy introduced his new and larger French-style architecture at bangor around the year 1140. This would fit in well with the comment of a local man who, as reported in st. b ernard of Clairvaux’s life of Malachy, asked the saint ‘why have you thought to introduce this novelty into our regions? we are scots, not Gauls. what is this frivolity? what need was there for a work so superfluous, so proud?’. It may be noted that churches or other buildings on some of the sites associated with st. Patrick in the Downpatrick area – such as Raholp and struell wells – belong at earliest to the later Middle Ages, though one curious stone-roofed ‘shrine’ near the modern church at saul may be somewhat earlier.

The ruins of the medieval church at Raholp, near Saul.

28

The h igh Crosses and r ound Towers of Coun T y d own: a f ield g uide

T H e To UR

our tour of the High Crosses and Round towers of County Down begins and ends in Downpatrick, and follows a clockwise, or ‘sunwise’ route (Ir. deiseal).

you should start your visit at Down County Museum, where the Downpatrick High Cross will be on display from Julyne 2015, after conservation. A replica has been set up at the east end of Down Cathedral, where the original stood between 1897 and 2013.

29

Medieval crosses and other objects on display in Down County Museum’s Down Through Time exhibition in the central Governor’s Residence building.

The Downpatrick High Cross, before its removal to Down County Museum for conservation in 2013.

The Downpatrick High Cross, before its removal to Down County Museum for conservation in 2013.

In the Museum you can see objects from a number of early Christian sites including saul, struell wells, Raholp, nendrum, Maghera, Derry and Dundrum, in addition to the shrine of st Patrick’s Jaw, on loan from st Patrick’s Church, belfast. Afterwards you can see the replica of the High Cross at the, east end of Down Cathedral, st Patrick’s Grave and the Cathedral itself (with the fragments of st Patrick’s Cross inside the entrance, and the socket stone re-used as a font) and st Patrick’s Grave on the Hill of Down.

31 The Tour

DoWnPaTRICK HIGH CRosses

Grid reference: J482444

Geology: G2 Outer Mourne granite; replica G2 Inner Mourne granite (from Thomas’ Mountain Quarry)

dates:

Scripture Cross late 9th/early 10th century; St Patrick’s Cross 9th century; socket stone (now font) 9th/early 10th century; small wall-mounted crosses 12th century

Downpatrick only got the second part of its name in the 1180s when the norman conqueror of the County, John de Courcy, miraculously ‘discovered’ what he claimed were the bones of Ireland’s three national Apostles, Patrick, brigid and Colmcille, and had them presumably displayed in the present Cathedral’s predecessor – even though we know that Colmcille died and was buried in the monastery he founded on the Hebridean island of Iona. Probably as early as the late fifth century, the Hill of Down had been the centre of power of the Dál Fiatach, who provided the ulaid with many of its over-kings. by the second half of the eighth century at latest, it had been transformed into a monastic foundation which it remained in the old Irish fashion until the twelfth century when, in 1111, it became an important episcopal see. Its bishop from 1137 until his death in 1148, was the famous Irish church reformer, st. Malachy, who was also a papal legate. The reforms he spearheaded later brought the b enedictines to Downpatrick in 1183, and it was their church (started in the early thirteenth century and never finished on the grand scale originally designed) that later became the Cathedral church of the diocese.

Along with Donaghmore and one of the Clonlea crosses, the Downpatrick High Cross is the only known bearer of biblical scenes in early medieval Down. now 7 feet 10 inches tall above the base, the cross head, shaft and socket stonebase are made from Mourne granite, according to geologist Ian Meighan (see table 2 aboveAppendix 1).

The cross stood at the east end of Down Cathedral from 1897 until 2013, prior to which it lay in pieces in various locations, having been removed from the foot of english street in 1729, from which it got the name of ‘The

32 The h igh Crosses and r ound Towers of Coun T y d own: a f ield g uide

Market Cross’. Its long exposure to the elements and various moves help to explain its weathered and worn condition, though it may also have suffered somewhat from the hammer of pilgrims or iconoclasts. The Cross was removed to the Museum in the winter of 2013-14 in order to conserve it and place it on display under cover. It was replaced by a replica cross in Mourne granite made by s McConnell and sons of Kilkeel just in time for easter, on 16 April 2014. After a programme of conservation and recording, the original cross takes pride of place in a new gallery in the Museum from the summer of 2015.

The replica High Cross, made by S. McConnell and Sons of Kilkeel, is put in place on 16 April 2014.

33 down PaT ri CK high C rosses

The roll moulding at the corner of the shaft seems to have been deliberately removed on all four corners, as has the decoration on the north side –fortunately leaving intact the interlace on the south side. The abrasion of the figures makes identification extremely difficult, so that what follows is, at least to some extent, informed guesswork based largely, though not entirely, on comparisons with the biblical scenes on other ulster crosses.

Shaft

The bottom of the shaft is missing, having been trimmed off to make a tenon, probably before it was re-erected in 1897. b eginning with the west face, most people would agree that what is visible of the lowest panel is a scene representing Adam and Eve, with the branches of the apple tree arching over their respective heads to fall down (now invisibly) behind their backs. without any framing device or bar (as on the east face), the next panel up may well be Cain and Abel, who are usually shown on ulster crosses as a group of three, the third figure, in this case on the left, presumably representing the lord. other than the heads, the most striking feature here is the upright object behind the figure on the right which could be taken as the club with which Cain killed his brother who, thereby, became the first innocent victim of the old testament.

Above that is what seems to be an figure on asshorseback with large ears, bearing a rider who facesriding towards the left and makes a blessing gesture., whose significance or identity remains obscure Michael King has made a case for this scene representing Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem, though usually Christ faces right rather than left on such depictions.

The upper half of the shaft consists of two scarcely-differentiated panels each with three figures or, in certain lighting conditions, a single tall figure facing right and flanked on both sides by much smaller figures. All is too worn to be able to suggest reliable identifications.

on the east face, the only panel to offer a reasonable likelihood of identification is the tallest one, second from the bottom. In it, we see one figure standing on the right and moving towards the left, a second one possibly facing us in the centre, and on the left a seated figure facing right, above whom is a third standing figure. This may wellis most likely to be The Adoration of the Magi, with the seated Virgin presenting the

34

h igh

Towers of Coun T y d

The

Crosses and r ound

own: a f ield g uide

The west (originally east) face of the Downpatrick High Cross.

Detail of Cain (right) and Abel (centre), with God the Father witnessing Cain’s crime on the left.

now imperceptible Christ child to the Three Kings coming from the east. The other panels below and above the thick horizontal bars (somewhat reminiscent of Arboe) present significant problems of interpretation due to weathering. Michael King interprets the top scene as representing the hermits st Paul and st Antony on the occasion of their meeting and breaking of bread in st Paul’s cave in 346 AD, though this scene is now very worn. Given that the chronological order of scenes on High Cross shafts usually (but not always) goes from bottom to top, one would expect the panel below the bar beneath the Magi to be an Annunciation or a Visitation, or even a John the Baptist scene, but none of these seems likely. one possibility is SS. Paul and Anthony breaking the loaf of bread between them at chin level, with the raven above (at an angle) having brought the full loaf. but, if so, it would be a most unusual for it. Above the thick bar over the Magi are panels of three and two figures respectively which, however, are too worn to attempt any reasonable identification.

36

h igh

and r ound Towers of Coun T y d own: a f ield g uide

The

Crosses

The east (originally west) face of the Downpatrick High Cross.

Head

The head has worn very badly on both faces, but at least on the east face we can make out The Crucifixion, with Christ attended by stephaton and longinus, and also by the thieves on the arms. The west face very probably has a Last Judgment scene, there being enough standing figures visible to support such an identification.

The Crucifixion on the east face of the Downpatrick High Cross.

Other crosses

In the Cathedral porch, there are two cross-fragments which fit together and probably formed the top of the shaft and the crossing of a Mourne granite cross which has an interlace pattern enclosed by two circular mouldings in the centre of the head. It has part of a meander motif on the arm and an indeterminate pattern on the shaft on one face. on the reverse is a sunken circular centre flanked by interlace on the top of the shaft, as well as a rectangular sunken panel on one arm. Another separate fragment also has a rectangular sunken panel on one side, a generous spiral decoration on the other face, and a small tenon, which would have necessitated a mortise hole

38

The h igh Crosses and r ound Towers of Coun T y d own: a f ield g uide

to fit into. These fragments may have been part of st Patrick’s Cross, shown in drawings as standing at st Patrick’s Grave in the 1840s.

A fragment of the cross-head of St Patrick’s Cross, now inside the entrance of Down Cathedral (photograph

Sketch of St Patrick’s Cross in 1840 (Down County Museum Collection; acquired with the assistance of P. Harbison).

39

down PaT ri CK high C rosses

by Bryan Rutledge).

In the Cathedral nave there is a squared baptismal font of Mourne granite with sunken vertical panels which sufficiently resembles that of the base of the Drumgooland/Drumadonnell cross, as Michael King pointed out to me, that it may once have been the base of a cross – perhaps for the scripture Cross or st Patrick’s Cross.

The font in Down Cathedral, made from a socket stone for a High Cross. Close by, on an east-facing crossing-wall, are the remains of two comparatively small crosses of differing sizes bearing figures standing out in high relief as found in crosses particularly in Munster and Connacht in the mid- to late-twelfth century. b oth crosses have an unpierced ring. The larger of the two bears the figure of an ecclesiastic with damaged head, wearing a long grooved garment to the feet, with a cloak of similar fabric over it to below the thigh. In the right hand it holds a crook facing towards its left while, in the right hand, it holds a roughly square-shaped object with what could be taken as two finials on top. This is probably a reliquary, and the figure may well represent st. Patrick holding a relic of himself (not entirely unusual in medieval statuary), the cross commissioned perhaps by John de Courcy, norman conqueror of ulster, after he had – in one of the great PR coups of the Irish Middle Ages - miraculously ‘discovered’ the bones of Ireland’s three national Apostles, Patrick, brigid and Columba (of whom only Patrick may have been buried in the Downpatrick area!). A smaller and less complete cross-head has a smaller figure bearing on the chest or breast

40

The h igh Crosses and r ound Towers of Coun T y d own: a f ield g uide

a square cross-decorated object which could equally have been meant to represent a reliquary – this time perhaps of st. brigid.

Two small crosses placed in the wall of the narthex of Down Cathedral.

Now drive from Downpatrick to Castlewellan, where, in the square, you can see a replica of the Drumadonnell High Cross, located on the left as you drive through the centre of the town.

[Insert map 3 here, showing route between Downpatrick and Castlewellan, also showing locations of Drumgooland and Drumadonnell.]

41 down PaT ri CK high C rosses

DRUMGoolanD/DRUMaDonnell HIGH CRoss

Grid reference (currently in store): J335365

Geology: G2 Mourne granite dates: late 9th/early 10th century

We do not know the original site of the granite cross which stood in the old graveyard at Drumgooland until 1778, after which it was built into the wall of a school at Drumadonnell, about eight miles west-north-west of Castlewellan (J244392). but when the school was sold around 1972, the Department of the environment rescued the cross and brought it to a store in Castlewellan Forest Park where it has remained ever since, though only rarely on view to the public.

b oth base and cross are made of Mourne granite. The former, a massive square block 94cm high, is undecorated except on what we may call its west face where there are three sunken vertical panels. The decoration of the socket-stone is reminiscent of the large Mourne granite block, also probably an early medieval cross-base, converted for use as a font in Down Cathedral. The cross itself is 2.65m high. b oth main faces have an unusually broad, flat moulding which goes from the bottom of the shaft and follows the outline of the cross right up to the capstone, all of which are, remarkably for a cross of its height, carved from a single monolithic piece, though now broken across the shaft. on the ‘east’ face, the narrow decorative panel between the flat mouldings coming in from each side is filled with an interlace pattern which continues through constrictions in the head to above the level of the top of the ring. At the centre of the head, the broad moulding frames an area shaped like a diamond with concave sides. The interlace within it encloses a raised circular moulding embracing a ‘nest’ of eight bosses around a ninth in the centre. This is a feature which helps to link this cross to a whole series of other examples with a wide geographical range stretching from the midlands of Ireland to the Inner Hebrides of scotland. For those admiring the newly-carved cross, this motif must have had some important symbolic

42 The h igh Crosses and r ound Towers of Coun T y d own: a f ield g uide

The Drumadonnell Cross.

The Drumadonnell Cross.

meaning which is now, sadly, lost to us. The ‘west’ face is similar in outline, but the sunken vertical panel of the shaft is divided on this side into four vertical panels, probably all filled with interlace, though only that on the bottom is still sufficiently well preserved to make out its design. In contrast to the ‘east’ face, however, the centre of the head consists of a raised boss which is so worn as to make it impossible to distinguish any ornament on it.

The sides are similar in having a central panel decorated with interlace. This is probably the only cross in Ireland where the shaft decoration continues uninterruptedly up into the underside of the ring and the arm. This is best seen on the south side, where a roll moulding manifests itself on both the outer and inner edges of the raised bands flanking the sunken panels of interlace, and they each bear a continual roll of spirals which, again, continue from the shaft up into the underside of the ring and arm.

The excellent replica of the Drumadonell Cross in Castlewellan, carved by S. McConnell and Sons of Kilkeel.

[Insert map 4 here, showing route between Castlewellan and Maghera.]

For those disappointed at not being able to see the original, it is fortunate that the splendid copy in the centre of Castlewellan, made by s. McConnell and sons of Kilkeel, manages to show the nature of the interlace ornamentation even better than the original!

Now head for Maghera from Castlewellan.

44

The h igh Crosses and r ound Towers of Coun T y d own: a f ield g uide

MaGHeRa RoUnD ToWeR

Grid reference: J372342

Geology (round tower):: mainly siltsone and Newry granite (i.e. granodiorite glacial erratics)

dates: 10th/11th century

The patron of the site is quoted in early historical sources as Domongort mac echdach, who has given his name to the lordly peak of slieve Donard, in the plain beneath which the remains of the ancient monastery stand. The present church reached at the end of a long avenue is probably no earlier than the thirteenth century, but some early Christian cross-decorated stones are known to have been associated with the church surrounds.

The thirteenth-century church in the graveyard at Maghera.

what is unusual here is that the Round tower stands about 250 feet northwest of the medieval church, where one would normally expect it to have been much closer. excavations in 1965 showed burials to the north of the tower, suggesting that there may have been more features close to the tower than meets the eye today. Diggings around the 1840s also uncovered human remains inside the tower. The Round tower, composed of a combination of granite and shale, is – at about 18 feet – the second tallest surviving

45 Maghera round Tower

Round tower in Down (after Drumbo). but it was originally very much taller – an account of 1744 states that its upper part was blown down in one piece in a great storm around 1710, so that it resembled a cannon lying horizontal on the ground. but the disappearance of all its fallen stones makes it impossible to judge how tall the whole was originally. It may well have vied in height with Downpatrick Round tower which, equally, did not survive the end of the eighteenth century intact. Instead of its original doorway, all we see today is a featureless oval gap facing roughly east and placed some five and a half feet off the ground. Though using a different type of stone and with no sign of the outer walls inclining slightly, its internal diameter of 9 feet matches exactly that of the tower at Drumbo, whose founder Mochumma is said to have been a brother of Domongort’s, suggesting the possibility that both Round towers were built by the same mastercraftsmen – at some date unknown around a thousand years ago.

[Insert map 5 here, showing route between Maghera and Kilbroney (via Hilltown)].

46

The h igh Crosses and r ound Towers of Coun T y d own: a f ield g uide

Maghera Round Tower, showing the aperture where the doorway was located.

From Maghera now head towards Kilbroney, near Rostrevor.

KIlbRone Y HIGH CRoss

Grid reference: J188195

Geology: G5(?) Outer Mourne granite; socket stone G4 Outer Mourne granite dates: 9th century

The place-name Kilbroney means the church of brónach, ‘a virgin from Glenn sechis’ but, other than her feast day, April 2nd, we know nothing further about her - when she lived or even where Glenn sechis was. nevertheless, she was obviously much revered in the early Middle Ages because there is a cast bronze bell of around the ninth century which was found in the graveyard in the eighteenth century and is now proudly displayed in the Roman Catholic church farther down the valley in the town of Rostrevor. what was described as the saint’s crozier referred to in a fifteenth-century source, has long disappeared without trace.

The ringless Kilbroney Cross.

K il B roney high C ross

The site of the cross dominates the area of a holy well dedicated, curiously, not to the local, but to the national saint, brigit. The largest monument in the graveyard is a ruined late medieval church which has been restored by the northern Ireland environment Agency. Thirty-six feet to the south of it, the cross stands in a large square base-stone, the date of which is so uncertain that it is not known whether it was made originally for the cross.

The cross itself is 7 feet 7 inches tall, three feet one inch across the arms and only eight inches thick. together with one at Clonlea, it is unusual in having the armpits of the western side recessed to a depth of only just over two inches deep, rather than penetrating the full depth of the cross. The west face is flat, in contrast to the east face which has a rounded surface which bears no ornament. As if to make up for that, the whole of the west face is ornamented with mostly square panels separated on the shaft by horizontal bars, the whole being enclosed within a roll moulding which frames the entire outline of the cross.

The lowest panel on the shaft (a quarter of which is invisible below the level of the base) appears to have t-shaped designs carved in relief, rather similar to those found on the arms. The second and fourth panels from the bottom are too worn to be able to make out anything on them; the third has a fretwork design based on a st. Andrew’s cross, while the fifth bears a meander pattern – like angular spirals emanating from a centre with each element curling itself up at its end. Above this panel is a triangle with a central upright stem separating two smaller triangles (bird-shapes?) which flank the lower armpits. The meander pattern at the centre of the cross-head is similar to that at the top of the shaft – and to that above it on the topmost limb of the cross. b oth arms carry t-shapes – one upright, the other upside down – with their stems almost meeting at the centre.

The Kilbroney cross is almost certainly a copy in stone of a wooden cross, and some of the ornament on the west face may well have been copied from square wood-carved panels. but the t-shapes on the arms and on the panel at the bottom of the shaft are much more likely to have been modelled on metalwork with cloisonné enamel inlays, which could well argue for a ninth-century date for the cross, rather than the more usually proffered eighth-century suggestion. only a few yards west of the cross is a stone carved in the stylised shape

48

h igh

ound Towers of Coun T y d own: a f ield g uide

The

Crosses and r

of a human figure, with a simply delineated head, and the body and arms decorated with the outline of a cross. suggestions for the date of this stone range widely from the seventh to the eighteenth century! Close by is the beautifully-carved Fegan headstone of 1831, a wonderful example of sculpture in slate.

The Kilbroney Face-cross

At nearby Clonlea (nGR J188222), an inaccessible site not recommended for visiting, are three crosses recalling the form of the Kilbroney Cross. nothing is known of the history of this small graveyard in Greenan townland; off the beaten track, it contains three crosses in a row running north-south.

49 K il B roney high C ross

The south cross, identified by Ian Meighan as of Mourne granite, appears to be a modern copy of the shape of the Kilbroney cross. b earing the letters P MC M and the date 1852, the socket stone in which it stands must be almost a thousand years older. It is probably a rough contemporary of the Kilbroney cross with which it shares panels of meander decoration parallel to the long side of the cross on the upper surface of the base, while spirals emanate from the corner of the mortise-hole. The sides of the base are fairly straight, whereas the narrower ones are more rounded.

The decorated socket stone of the south cross at Clonlea.

The central cross, of newry granite, may also be modern, but the northernmost of the three, which also sits in an ancient but undecorated and stepped base, must be old because its east face is divided into a number of roughly square panels which, seen in the right light, can be seen to bear figure sculpture which is too tantalisingly worn to be identifiable. The centre of the cross may possibly have borne a ringed cross in relief, the foot of which may be rounded.

50

The h igh Crosses and r ound Towers of Coun T y d own: a f ield g uide

From Kilbroney now head to newry. This is a good opportunity to visit newry and Mourne Museum in bagenal’s Castle, where local early Christian and medieval finds, including a cross-slab, are on display amongst many other fascinating displays. The Museum occupies part of the site of a medieval Cistercian monastery.

[Insert map 6 here, showing route from Kilbroney to Donaghmore, including newry].

From Newry, head north towards Donaghmore.

51 K il B roney high C ross

The three Clonlea crosses.

DonaGHMoRe HIGH CRoss

Grid reference: J105350

Geology: Newry granite dates: late 9th/early 10th century

Donaghmore’s old Irish name is Domnach Mór Maige Coba (‘of the plain of Coba’) but, although the element Domnach (‘sunday’) indicates a very early stratum of place names in early Ireland, very little is known about the ancient history of this site. However, its probable patron was named erc, and ‘holy bishops’ of Donaghmore find honourable mention in the Litany of Irish Saints of around 800.

nothing remains of the medieval church, which was probably part of the see of Armagh and in the hereditary keepership of the McKerrell family, but it was probably on the same site that the existing church was built in the 19th century. There would appear to have been an earthen enclosure around and beyond the limits of the present churchyard which may have indicated the extent of the ancient monastery, but its traces can no longer be made out satisfactorily. The High Cross is said to stand on the capstone of an extensive underground passage known as a souterrain which was, however, closed down in 1890 – probably at the same time that the parts of two separate crosses were erected one above the other on top of it. It is worth mentioning that the newry and Mourne Museum houses a cross-decorated stone which came from Aughnacavan not very far away.

The main feature here is a High Cross of newry granite (as identified by Ian Meighan). It is, interestingly, the only example in Down to have a pierced ring, and only one of three in the County to bear biblical carvings. There is a reasonable chance that its stepped base is old – as is also the case with a similar one at Clonlea only seven and a half miles away. As with so many of the ulster crosses, it is composed of pieces of two separate crosses –the shaft and the head respectively, the latter of which can be seen from the side to be considerably narrower than the shaft – so that we must envisage that there was a minimum of two crosses on the site originally.

52 The h igh Crosses and r ound Towers of Coun T y d own: a f ield g uide

The east face of the Donaghmore High Cross, showing the Last Judgement on the cross-head.

The east face of the Donaghmore High Cross, showing the Last Judgement on the cross-head.

The west face of the Donaghmore High Cross, showing the Crucifixion on the cross-head.

Shaft

The comparatively narrow angular shaft has a broad collar below, and a narrower one at the top, both being linked at the upright corners by broad roll mouldings. within them there is a further, more slender, moulding framing the sculptures vertically on the east and west faces. on the narrow sides the moulding separates the raised panels of decoration and sculpture horizontally by coming in towards the centre but redoubling back on itself without meeting its fellow on the other side. This ‘split frame’, as it is known, is a feature characteristic of some of the ulster crosses, but also of others in the b oyne Valley and midlands of Ireland, thus showing connections that go far beyond the bounds of its own county.

Most ulster scriptural crosses would have had the east face of the shaft devoted (usually exclusively) to the old testament and the west face to the new. one of the features which make this Donaghmore cross different

55 donagh M ore high C ross

The stepped socket stone of the Donaghmore High Cross.

from the rest is that – in as far as we can recognise the subject-matter of the carvings – both faces bear old testament material, though new testament material may also have been included. Reading from the top downwards on the east face we have three figures with the one in the centre being taller than the other two. This is a feature found in Baptism of Christ scenes, as on the cross in Armagh Cathedral, but this is an unlikely identification here, as there is no sign of the waters of the Jordan beneath. The central figure does, however, seem to hold a book upright in the left hand, suggesting that this may be a new testament scene of Christ flanked possibly by disciples, perhaps akin to the probable Transfiguration scene on the west face of Muiredach’s cross at Monasterboice in the neighbouring county of l outh. beneath these three figures we can see, on the left, David holding up a stick bearing the head of Goliath while, on the right, David holds up a lion which he slew because it took a sheep from his flock. beneath the beast’s hind-quarters a circle with a dot in it can be seen to link up with another similar disc beneath the David figure with the head of Goliath. These probably denote the rock in Horeb (e xodus xvii,6) from which Moses (beneath the lion-holding David ) smote water in the sight of the elders of Israel, who are shown at a small scale beneath the two strands of water gushing out below the linked circles. beneath these are a set of three figures who are stepped up towards the right like the old advertisement for ‘Growing up on Fry’s cocoa’, and beneath them again a further three figures, with that on the right this time being smaller. This lower trio seem to be standing on a set of four heads, leaving us none the wiser as to the identity of the figures on the lower two-thirds of the shaft. on the west face, there is a framed panel of interlace on the bottom collar, above which we find Adam and Eve facing us as the branches of the apple tree tower over them. Above the tree are four fish, to be understood as swimming in the waters on which the angular Noah’s Ark above them floats. Part of the composition is damaged and, above the crack, are two figures, that on the right slightly taller, but who they are is not easy to decipher. At the top of the panel, beneath possibly a bird and a fish, are two figures of approximately equal size, that on the right holding a large sword or club in the right hand. This could be Cain slaying Abel, though on most of the northern crosses featuring this event, three figures are shown.

56

The h igh Crosses and r ound Towers of Coun T y d own: a f ield g uide

The sides of the shaft bear raised panels of interlacing animals with a head at each corner, and only one panel with human figures, neither of which are easily identifiable. That on the bottom of the south side shows a standing figure holding what appears to be a smaller figure upside down (with possible echoes of the possible Simon Magus figure on the arm of the tall Cross at Monasterboice), while that second from the bottom on the north side has a figure on the right holding up a sword (?) at a slight diagonal as if to strike the smaller figure on the left with a circular object above its head.

Head

As mentioned above, the head belongs to a separate cross, carved in lower and less striking relief than the shaft, added to which the surfaces have not withstood well the test of time. The ring seems to have been decorated with interlace ornament, and the curious ‘cylinders’ going through from side to side as found on so many of the Irish ringed crosses are seen here on the inner side of the ring.

Christ is the central figure on both faces. on the east, he is seen standing, apparently holding an object in each hand and flanked by numerous figures extending out to the ends of the arms. This may be taken as a representation of The Last Judgment, so reminiscent of the same panel on Muiredach’s Cross at Monasterboice, on which the stylised composition may well have been based. whether st. Michael is shown weighing souls beneath Christ’s feet, as at Monasterboice, is a moot point, and the identity of the figures above Christ’s head remains unknown.

The Crucifixion occupies pride of place at the centre of the west face. The saviour seems to wear a long colobium, with his (possibly tied) feet appearing below the hem.

Visible beneath his left arm is what may be taken to be longinus with his lance about to pierce Christ’s left side (as on so many of the Irish High Crosses), while the much worn figure under his right arm is presumably stephaton giving the hyssop to Christ, though the details are so worn that it is difficult to make them out. As on a number of other ulster crosses, we have the two thieves shown in a crucified posture, with arms outstretched, each accompanied by a figure on either side. but what is so remarkable on this cross is the presence between the thieves and Christ’s hands of two small

57 donagh M ore high C ross

The two faces of the Donaghmore cross-head. figures, apparently seated, who may be identified as the figures of Oceanus on the left, and Terra on the right, ocean and earth respectively, as found on Muiredach’s Cross at Monasterboice in Co. louth and a few others. Above Christ’s head are what we may take to be angels, with rather long bird-like wings. Above them are two further figures with spirals emanating from their heads and, on top, there are the remains of a sloping roof. on the south side there would appear to be a small figure in the gable of the roof and, beneath it, possibly an interlace with bossed ornament. The end of the south arm

58

h igh

ound Towers of Coun T y d own: a f ield g uide

The

Crosses and r

bears interlace similar to that on the shaft beneath it, suggesting that both head and shaft were carved by the same sculptor – but each belonging to a separate cross. The end of the north arm has a further single figure with the right arm extended, and there is a possible further figure in the gable of the roof of the cross.

both elements of the cross – shaft and head – show a unique concentration of material reflecting both ulster and leinster connections. The links with other ulster crosses are shown by the predilection for old testament material (even to the extent of being found on both faces of the shaft) and, more particularly, the presence of the thieves on the arms of the Crucifixion scene – a feature not found south of the border. The leinster connection is seen particularly in the earth and ocean figures, as found on Muiredach’s Cross at Monasterboice, Co. louth, and probably also at Kells and Clonmacnois. Further links with Monasterboice are the scene of Moses striking the rock in Horeb and the two David figures – slaying the lion and holding up the head of Goliath.

while rooted firmly in the ulster tradition, as seen for instance in the presence of the thieves at the Crucifixion, this is the only cross in County Down which shows such remarkable iconographical links with Monasterboice that we can only suppose that the Donaghmore sculptor was copying in his somewhat intractable granite the more subtle modelling in sandstone seen on the Monasterboice crosses, of which the Donaghmore cross is a rather simplified and stylised version. The head of the Donaghmore cross is the only one among the County Down crosses which has the head pierced - a feature also seen on Muiredach’s cross at Monasterboice. The only difference is that the latter cross has ‘cylinders’ on the armpits of the cross head and not on the inner ring as at Donaghmore.

From Donaghmore, return to the main road from Newry and turn north towards Dromore.

[Insert map 7 here, showing route between Donaghmore and Dromore].

59 donagh M ore high C ross

DRoMoRe HIGH CRoss

Grid reference: J199533

Geology: Newry granite date: late 9th/early 10th century

amonastery was founded at Dromore on the banks of the river lagan probably early in the sixth century by st. Mocholmóg, otherwise known as Colmán. Coarbs (abbots) are recorded occasionally during the ninth and eleventh centuries, providing evidence of continuity in the monastery’s existence during the Viking period. A man named Riagan, who died in 1101, was described in the Annals of Ulster as bishop of Dromore, yet there is no mention of official recognition of Dromore – or Iveagh, uí echach – as the centre of a diocese until the very end of the century, in 1197, after it had, perhaps, been instituted as a diocese at a synod in Dublin five years earlier. b eing one of the poorest of Ireland’s dioceses during the later Middle Ages, it was not treated with the respect it deserved. Its bishops were often absentees (some of them english), one even hailing from as far away as brittany. From even farther afield came a Greek-born bishop, nicholas braua, who, however, did probably reside in the diocese from 1483 to 1499. Art Magennis, a scion of one of the region’s ruling families, accepted royal supremacy in 1550 and, since the seventeenth century, the bishops consecrated for the Dromore Church.

60 The h igh Crosses and r ound Towers of Coun T y d own: a f ield g uide

diocese have been Protestant – the diocese itself having been merged with Down in 1842. of the medieval Cathedral nothing survives, and the earliest parts of the present structure are the south and west walls of the nave, which date from the 1660s, during the time when Jeremy taylor administered the diocese as bishop of Down. He is buried in the Cathedral and, though disputacious on occasions, was known as a proponent of religious toleration. Inside the building is displayed ‘st. Colman’s Pillow’, a stone bearing a cross of early style with forked terminals which was ‘preserved from alienation’ (in lisburn) and returned to its original home in 1919. together with the cross now standing at the edge of the Cathedral grounds, it is the only surviving remnant of the old monastery – the large motte-and-bailey earthwork 400 yards away being a product of early norman occupation shortly before 1200, while the tower house overlooking the Cathedral may be no earlier than the seventeenth century. beside the road adjacent to the lower-lying Cathedral grounds, beside the river lagan, is a tall and once substantial granite cross, consisting now of three fragments which were re-assembled here in 1887. The large base required to steady such a heavy cross has rounded sides, with a roll moulding framing the upper edges, and up and down the corners. The side away from the road is rough at the bottom, suggesting that it was originally below ground level. The fragment of the lower part of the shaft has sides which reduce about an inch in width, a foot above the base – just below the level where the decoration begins – whereas the broad faces are absolutely straight. both sides of the shaft are decorated with rectangular panels of broad interlace divided into two halves by a pair of horizontal mouldings half-way up the sides, with a more marked interior moulding enclosing a recessed rectangular panel of fretwork ornament. The faces of the shaft also appear to have had interlace framing a recessed panel of decoration which is now much worn.

The upper part of the shaft is missing, replaced by a modern section bearing the following inscription in noticeably Irish-style lettering :

The ancient historical cross of Dromore erected and restored after many years of neglect by public subscription to which the b oard of Public

61 dro M ore high C ross

Dromore High Cross.

Dromore High Cross.

works were contributors, under the auspices of the town Commissioners of Dromore, Co. Down A.D. 1887.

The head of the cross has an unpierced and recessed ring, with a large central hemispherical depression, and the underside of the arms and ring are subdivided into three panels, the central one of which bears rather worn interlace. The erosion of the decoration may possibly stem from human wear and tear when the cross-fragments stood – or, more probably, lay –in the Market square for centuries before being re-erected in 1887. It was probably then that damage visible today may have been inflicted – reduction in the size of the north arm and the square holes in both arms, together with the destruction of part of the decoration on the west face of the shaft fragment. The capstone is unashamedly modern.

[Insert map 8 here, showing route between Dromore and Drumbo].

63 dro M ore high C ross

From Dromore, make for the Round Tower at Drumbo.

DRUMbo RoUnD ToWeR

Grid reference: J321651

Geology (round tower): greywacke sandstone, siltstone, quartz-rich sandstone, vein quartz date: 10th/11th century

The Martyrology of Tallaght of around 800 gives two names, lugbe and Cummine, associated with Drumbo, providing us thereby with the best literary evidence we have for the presence of an old Irish monastery here. to support this, we have the survival of a Round tower, but not of the church which would originally have stood near it.

Drumbo Round Tower.

64

h igh Crosses and r ound Towers of Coun T y d own: a f ield g uide

The

The tower stands behind the modern Presbyterian church to a height of about 35 feet, but the evenly-levelled top shows that the uppermost few feet are likely to be the result of a modern restoration. Though the walls are almost four feet thick, they are not particularly well built – their comparatively small silurian stones making the tower bulge noticeably on the north side, where there is a lintelled window near the top. burials down the centuries have raised the level of the earth around the tower, so that its doorway would have been considerably higher than the present five feet separating it from the present ground-level. The upper part of the doorway retains its original upright jambs supporting a flat lintel which has been dressed to conform with the general curve of the tower. The sill of the doorway no longer survives, and recent repairs around the bottom of the door are now outlined with small pieces of quartz. excavations in the interior of the tower in 1841 produced charcoal and bones of animals – but not of humans.

The greatest pleasure in visiting the tower is the great panorama it provides over the lagan Valley, with its sides falling steeply towards the river and providing a splendid distant vista of the city of belfast. At its original height, probably of around 80 feet, the tower would have provided a landmark and beacon for anyone proceeding along the valley floor, and beckoning to visitors – probably including pilgrims – to come to ‘the ridge of the cow’ as the meaning of the place-name implies.

Before returning to Downpatrick, for well-earned refreshments in Denvir’s, Downpatrick’s oldest inn (founded in 1642), head towards Nendrum, to see one of the best-preserved Early Christian monasteries in Ireland, located on the largest island in Strangford Lough.

[Insert map 9 here, showing route between Drumbo and nendrum].

65 dru MB o round Tower

nenDRUM RoUnD ToWeR

Grid reference: J524636

Geology (round tower): greywacke sandstone, red sandstone date: 10th/11th century

It is a long and windy road over island and causeway that leads to the venerable ancient monastery of nendrum, itself on an island named Mahee, but it is worth the detour if for no other reason than to enjoy the peace and the quiet – and the birdsong – beside the shores of strangford lough. but, more importantly, the journey will be rewarded with the sight of some of the most significant remains of an old Irish monastic enclosure anywhere on the island of Ireland, consisting of remains of a church, a Round tower and three roughly concentric stone and earthen walls on a raised hillock overlooking the waters of the lough.

Reconstruction of the first tidal mill of c. 619 AD (painting by Philip Armstrong, courtesy of the Northern Ireland Environment Agency).

The founder of the monastery is normally given as st Mochaoi who is said to have died in the 490s and to whom – according to a much later tradition – st Patrick is said to have given a crozier and gospel book. but neither historical sources nor excavations carried out by H. C. lawlor in the 1920s have shown any evidence of human activity until the seventh

66

h igh Crosses and r ound Towers of Coun T y d own: a f ield g uide

The

century at earliest, when the old Irish annals begin to record the deaths of bishops, abbots and a scribe between the years 639 and 976. Monastic occupation would have continued after that until the time when ulster’s norman conqueror, John de Courcy, established a small b enedictine house on the site after 1177. Its life would have been much shorter than its older counterpart and, by the fifteenth century, the monastery had declined to such an extent that it became little more than a parish church.