2016

Sightlines is produced by the Graduate Program in Visual and Critical Studies at California College of the Arts.

Visual and Critical Studies creates an interdisciplinary and culturally diverse framework within which to bring historical, social, and political analysis, as well as formal analysis, to bear on the interpretation of the visual world. VCS trains students to write professionally about the visual arts and visual culture. Students complete coursework followed by the production of a thesis project, leading to the Master of Arts degree.

For more information on the Graduate Program in Visual and Critical Studies at CCA, please contact us:

California College of the Arts 1111 Eighth Street

San Francisco, CA 94107-2247

Tirza True Latimer, Program Chair Mike Rothfeld, Program Manager

cca.edu/academics/graduate/visual-critical-studies viscrit.cca.edu

Acknowledgements Haptic Visuality:

Sienna Freeman Elena Gross Forrest McGarvey Systems,

Veronica Jackson Eden Redmond Tanya Gayer Mailee Hung

Jesus Barraza Ekin Balcioˇglu Bryndis Hafthorsdottir Bios

p. 01 p. 02 p. 03 p. 04 p. 05 p. 06 p. 07 p. 08 p. 09 p. 10 p. 11 p. 12 p. 13

and the

order and

through

“For years now,” New York Times critic Holland Cotter recently observed, “there have been laments about a ‘crisis in criticism.’”1 For some, that “crisis” relates to the art market’s ascendant role in the ascription of value. For others, it has more to do with the advent of the Internet—which has enabled exercises of critical thought more varied and decentralized than at any other time since criticism emerged as a professional vocation roughly two centuries ago. The proliferation of critical platforms and critical perspectives is not, in and of itself, a problem. On the contrary, as the flm critic A.O. Scott has argued, “Criticism, far from sapping the vitality of art, is instead what supplies its lifeblood…not an enemy form which art must be defended, but rather another name—the proper name—for the defense of art itself.”2

1 Holland Cotter, ‘The Contemporaries,’ ‘Painting Now’ and More,”

The New York Times, Sunday Book Review, 25 June 2015. http://www. nytimes.com/2015/06/28/books/review/the-contemporaries-paintingnow-and-more.html?_r=0 (accessed 4/1/16).

2 A.O. Scott, quoted by Daniel Mendelsohn, “A. O. Scott’s ‘Better Living Through Criticism,’” The New York Times, Sunday Book Review, 19 February 2016. http://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/21/books/review/ao-scotts-better-living-through-criticism.html (accessed 4/1/16).

Many of our students have active critical careers. Some Visual & Critical Studies alumni work as editors for art publications, as museum educators, or as content developers for museum websites. They enter and complete PhD programs. They innovate new forms of pedagogy; administer nonprofts; publish reviews, essays and books; make flms; make magazines, make trouble. Together, they prove our institutional motto to be more than a mere slogan: in myriad ways, they “make art that matters.” They support each other and build cultural communities. They found online and analog magazines in which they write about socially signifcant forms that include art, performance, cinema, comics, historical representation, advertising, political propaganda, signage and sign systems, architecture, urbanism, public space, imaging technologies, migrant labor, mapping, DIY culture, traditional crafts, street

altars, GMOs, NGOs, and the for-proft prison system, to name a few representative areas of VCS alumni research over the past decade.

VCS graduates take part in the current crisis in criticism—a positive and necessary crisis. They have acquired the skills and earned the credibility to help shape cultural agendas as they pursue (and/or invent) careers beyond CCA.

The graduating students whose work appears in this year’s volume of Sightlines engage with artworks and artists who, like the authors themselves, think critically about culture and actively take part in projects of world-making. Jesus Barraza introduces Dylan Miner’s project Native Kids Ride Bikes to discuss the creative uses of indigenous traditions for building decolonized communities and value systems. Ekin Balcıoğlu argues that Duncan Campbell’s flm essay It for Others breaks down dichotomous structures (e.g., subject/ object, form/content, self/other) that subtend the colonial logic of museum collections and display. Sienna Freeman flls a critical lacuna in scholarship about the Surrealist Dorothea Tanning by devoting sustained consideration to the artist’s soft sculptures. An online video diary by Erica Scourti provides a point of departure for Tanya Gayer’s interrogation of the taxonomical systems and technologies that mediate our social identity and relations. Elena Gross analyzes the shift in Lorna Simpson’s practice from making photographs to producing serigraphs on felt, and the ensuing transformation of embodied and phenomenological content in Simpson’s art. Bryndis Hafthorsdottir focuses on the work of Ragnar Kjartansson to explore intersections of local tradition and global forces in Icelandic contemporary culture. Mailee Hung places discourses of materiality and disability aesthetics in conversation with Donna Haraway’s cyborg to explore what the prosthetic body has come to emblematize in recent popular culture. Focusing on turn-of-the-twentieth-century

vaudeville performer Aida Overton Walker, Veronica Jackson presents popular theater as a site of feminist contestation and “racial uplift.” Through an analysis of Ken Okiishi’s oeuvre, Forrest McGarvey considers how screen technology now sets the terms not only for virtual but material engagement with the world. Looking at Hobbes Ginsberg’s Tumblr-based compositions, Eden Redmond explores the relevance of the still-life genre in our contemporary consumerist era. These projects came to fruition within the rigorous intellectual community of the Visual & Critical Studies graduate program, itself embedded in CCA’s distinctive art-school environment. Faculty members from diverse programs and departments at CCA, as well as scholars and artists from other institutions and organizations, have contributed to our students’ evolution. The effectiveness of this teamwork attests to the disciplinary diversity and collaborative character of the Visual & Critical Studies enterprise. We are profoundly grateful for these alliances.

Tirza True Latimer, Chair Visual & Critical Studies

Acknowledgments

On behalf of the students and the VCS program, I would like to acknowledge a few of the individuals who helped bring this year’s thesis projects and the Sightlines journal to fruition. Jacqueline Francis and Makeda Best led the way as primary VCS thesis directors. Thesis co-directors Michele Carlson and Frances Richard prepared students for the VCS Symposium and assumed responsibility for the production of Sightlines 2016, respectively.

Markus Thor Andresson, Maria Elena Buszek, Rebekah Edwards, Kit Hammonds, Anne Harris, Peter Krapp, David Krasner, Patricia Lange, Elizabeth Mangini, Julian Myers-Szupinska, Dawn Nafus, Eric E. Olson, Laura Perez, Jordana Moore Saggese, Cherise Smith, Marquard Smith, Tina Takemoto, and Kathy Zarur provided invaluable guidance and critique as internal and external advisors.

This volume of Sightlines benefts from the expert copy-editing of Victoria Gannon and from the design prowess of Megan Lynch.

Finally, I would like to commend Mike Rothfeld, VCS Program Manager, whose professionalism, creativity, executive capacity, and dedication have maintained the vitality of the VCS program and assured the success of its students.

Haptic Visuality: Rethinking surface, physicality, and the visual

In the frst years, I was painting on our side of the mirror—the mirror for me is a door— but I think that I have gone over, to a place where one no longer faces identities at all. 1 –Dorothea Tanning, 1974

If we take the word of American Surrealist painter, sculptor, and writer Dorothea Tanning (1910–2012) that early in her career she was painting on “our side of the mirror,” while in later works she created from a place where identity is unconstrained by specular representation, we can identify a clear division between her early and late approaches to confronting alterity. Her initial approach is contained within paradigms of the imaginary, linked to the symbolic law of language and Modernist ocularcentrism in painting. By contrast, her later method evokes an ambiguous sense of otherness that is fostered in the realm of the abject, beyond the restraints of the refected self-image. Tanning’s nearly thirty works of soft sculpture, created between 1965 and 1982, are emblematic of this pivotal change.2

Although sixteen pieces from this series can be found in museum collections worldwide, Tanning’s cloth objects are largely absent from critical discourse, overlooked or marginalized as avatars for her painted fgural elements. 3 While earlier themes of

1 From Tanning’s 1974 interview with Alain Jouffroy in: Dorothea Tanning (Sweden: Malmö Konsthall, 1993), 57. 2 “Tanning Sculpture List,” PDF provided by the Dorothea Tanning Foundation in an email to the author, October 4, 2015.bodies, boundaries, self-portraiture, and the female muse persist in her soft sculptures, I argue that the latent meanings attached to their construction from textile—a medium generally associated with corporeality and functionality—activate transgressive possibilities that are otherwise limited in her paintings. I propose that Tanning’s soft sculptures break the metaphorical picture plane associated with the Lacanian imaginary, entering into the borderland territory of the abject as defined by psychoanalyst Julia Kristeva. Deviating from the canoni cal ideology of André Breton’s founding version of Surrealism, Tanning’s soft sculptures become experiential forms of matter in bodily terrain, aligning instead with the alternate surrealist platform established by Georges Bataille.4 By focusing on these fundamental shifts, we can see that Tanning’s cloth works demand a revisionist reading, one that establishes them in material terms specific to the abject.

3 Tanning spoke of her soft sculptures as “avatars, threedimensional ones, of the figures in my two-dimensional universe.”

See: Dorothea Tanning, Between Lives: An Artist and Her World (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2004), 282. For other sources that echo this sentiment see: Dorothea Tanning, JeanChristophe Bailly, and Robert C. Morgan, Dorothea Tanning (New York: G. Braziller, 1995), 302; and Anna Lundström, “Bodies and Spaces:

On Dorothea Tanning’s Sculptures,” Journal of Art History 78, no. 3 (2009): 121.

4 Julia Kristeva credits Georges Bataille with providing one of the foundations for her theories on abjection. See: Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, ed. Leon S. Roudiez (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982), 64.

Born from a cultural arena defined by the horrors of World Wars I and II and the profound effects of the industrial revolu tion, Surrealism aimed to disrupt social norms on a global level by tapping into the collective unconscious and unleashing repressed desire.5 Breton’s ideals for Surrealism are characterized as “crystalline and lyrical,” propelled by goals of collective transcendence and utopian hope for intellectual freedom.6 In contrast, Bataille’s path to liberation is charted not in transparency and light but through lowness, as it aims to expose an anti-dialectic experience of otherness beyond the symbolic realm.7 A conceptual split between the mind and body is evident in the relationship between these two ideologies, with Breton finding truth in the majestic, cerebral, or sublime and Bataille locating potency in baseness, physicality, or abjection. Hal Foster suggests that work by Tanning’s husband Max Ernst—the historically more celebrated artist of the couple—typifies Breton’s ide ology, which focuses on exploring the imaginary and unconscious as opposed to the material or corporeal.8 While Tanning’s early paint ings functioned similarly, her later soft sculptures no longer perform these ideals.

5 Matthew Gale, Dada and Surrealism (London: Phaidon, 1997), 6.

6 Michael Richardson, “Introduction,” in Georges Bataille, The Absence of Myth, Writings on Surrealism, trans. and with an introduction by Michael Richardson (New York: Verso, 2006), 5.

7 Bataille, The Absence of Myth, 125.

8 Hal Foster, Compulsive Beauty (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993), 110.

In a 1976 interview, Tanning discusses her material moti vations in the soft sculpture series: “These sculptures represent for me two or three kinds of triumph: The triumph of cloth as a material for high purpose…the triumph of softness over hardness…and the triumph of the artist over his volatile material, in this case living cloth.”9 In her view, “living cloth”—i.e., the cloths or coverings we associate with corporeal experience—is “volatile,” subject to sudden change and unpredictable degradation, like the body itself. In using cloth as a material for a “high purpose,” Tanning recog nizes that, unlike her painted figural elements, her cloth works not only challenge preconceived notions about the rigidity of fine art, but also draw on associations generated by the Modernist positioning of textiles as a “low” art form, historically associated with craft or women’s work, rather than as fine art. We can see that Tanning’s strategic use of materiality in her soft sculptures stands in contrast to Modernist ocularcentrism, which regards the flatness of paint on canvas as the purest and highest form of art.10

9 Monique Levi-Strauss, “Dorothea Tanning: Soft Sculptures,” American Fabrics and Fashions 108 (Fall 1976): 69.

10 Contemporary craft theorist Glenn Adamson explores the binary opposition between the optical and the material with regard to substances and forms embraced or rejected by fine art. He posits that the application and exploitation of craft materials and techniques have been coded as low, other, or not even art, as a result of a Greenbergian privileging of the purely optical. See: Glenn Adamson, Thinking Through Craft (New York: Bloomsbury, 2013), 40–1.

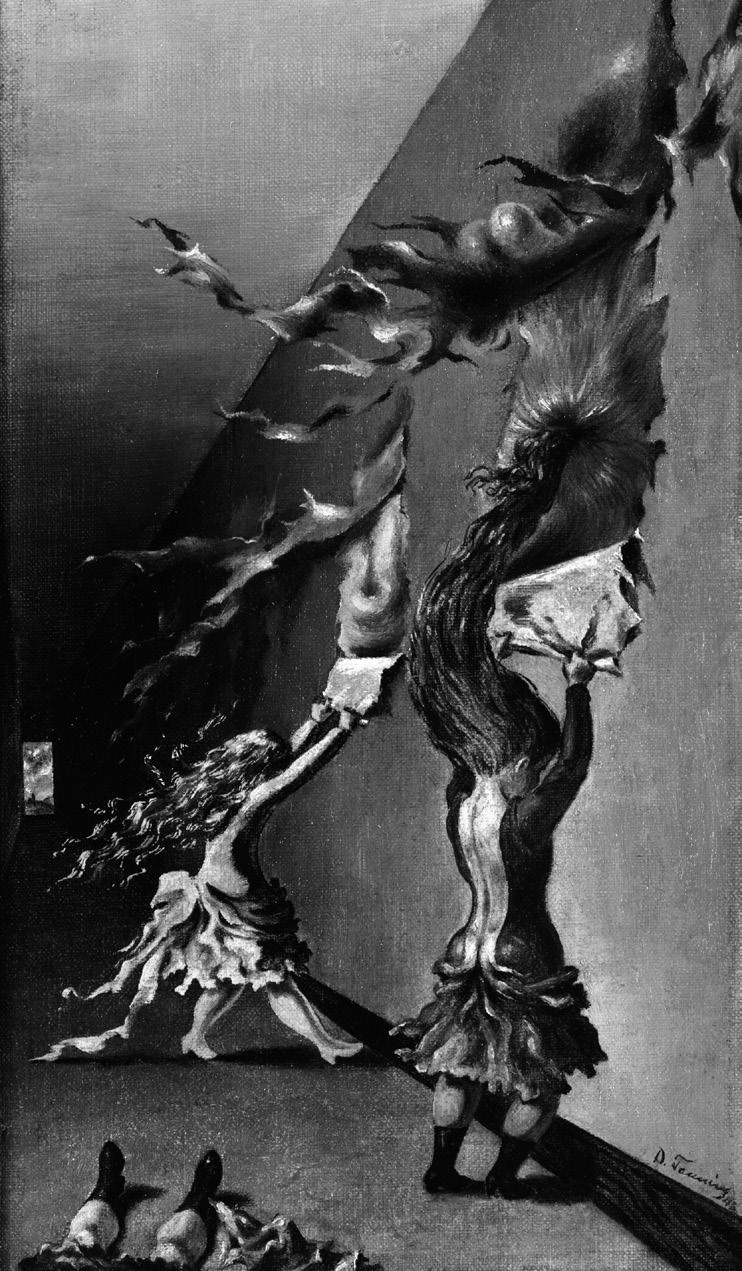

A comparison between Tanning’s 1942 painting Children’s Games (fg. 1) and her multi-part soft sculpture installation Hôtel du Pavot, Chambre 202 (fg. 2), from 1970–73, illustrates the implica tions of Tanning’s late approach. Demure in size at less than a foot tall and half that in width, Children’s Games depicts two wild-haired young girls viciously ripping at the seams of periwinkle wallpaper. This activity takes place in a dimly lit and seemingly endless hall way where a third body lies on the floor, chopped at the waist by the bottom of the picture plane. Two rectangular wounds have been made in the wallpaper, their torn edges exposing strange, sinewy, sagging masses. The room’s papered interior seems to serve as a mask for some muscular entity, alive and writhing as its fragile boundary is compromised. Children’s Games depicts female figures interrupted in action within a fantastic domestic space. However, though the

fig. 1 Dorothea Tanning, Children’s Games, 1942; Oil on canvas, 11 x 7 1/16 in.; Private collection; image courtesy the Dorothea Tanning Foundation, New York, NY.

fig. 2 Dorothea Tanning, Hôtel du Pavot, Chambre 202 (Poppy Hotel, Room 202), 1970–73; fabric, wool, synthetic fur, cardboard, and Ping-Pong balls; 133 7/8 x 122 1/8 x 185 in.; Collection of the Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris; image courtesy the Dorothea Tanning Foundation, New York, NY.

scene is surreal in its representation of a dreamlike narrative, the manner in which it is illustrated allows for a sense of visual famil iarity. Overall, its execution is quite traditional in terms of symbolic realism or Bretonian Surrealism.11 The image is contained within the canvas’s mirrorlike picture plane. Interior structures take on exaggerated but identifiable forms; endless hallways, open doors, and architectural thresholds serve as visual metaphors for transitional spaces of consciousness. The figures are recognizable as young girls, and the structure is believable as a house, regardless of the bizarre transformation that occurs within its boundaries. In Tanning’s soft sculpture, however, this rational legibility falls apart.

In Tanning’s installation Hôtel du Pavot, a series of domestic objects lose control of their proper formal boundaries. Five life-size anthropomorphic forms sheathed in chocolate brown and bubble-gum pink fabric emerge from and meld into the walls and furniture of a Victorian-inspired interior, their skins stitched from textile panels and their bodies stuffed with carded wool. Dismembered parts resembling limbs, backbones, and bellies meld with utilitarian items such as chairs, tables, fireplaces, and wallpaper, their haptic materiality and humanesque forms evoking uncanny connections to our own corporeality. Unlike the figures in Children’s Games, these bodies fuse into the environment that contains them, seemingly leaking from and being absorbed into its furnishings.

Individual works from Tanning’s Hôtel du Pavot, alongside others from her soft sculpture series, have previously been exhibited both as singular objects and as multipart works alternately configured.12 In each setting, viewers have encountered the work in different phenomenological iterations, ranging from traditional pedestal arrangements within a white-walled gallery space to dimly lit and dramatically staged museum displays.13 Hôtel du Pavot, as curated and historicized by the Centre Georges Pompidou in 1977, presents a life-size tableau of objects in which viewers encounter the installation much as they would a diorama at a natural history museum. Yet despite these differences in exhibition style, when viewers encounter Hôtel du Pavot in each of its iterations over time, their individual bodies enter into phenomenological dialogue with Tanning’s uncertain bodies (fg. 3).

12 Works from Hôtel du Pavot, Chambre 202, alongside other pieces from Tanning’s installations, were previously exhibited at Dorothea Tanning: Sculptures, Le Point Cardinal, Paris, May–June 1970, and Dorothea Tanning: Sculpture, Galerie Alexandre Iolas, Milan, February 23–March 18, 1971.

13 Images of alternate iterations and arrangements of works form Hôtel du Pavot, as well as three pieces from Tanning’s soft sculpture series, were viewed during the author’s November 5, 2015 trip to the Dorothea Tanning Foundation, New York, NY.

11 As exemplified by Max Ernst, Roberto Matta, Hans Arp, and others.The split between the imaginary-visual and the materialhaptic that separates Tanning’s early and late work can be further understood through the relationship between the psychological paradigms of Lacan’s mirror stage and Kristeva’s theory of the abject. Recapitulating the relative position of Bataille’s “low” approach to Surrealism, which embraces physical baseness, vis-à-vis Breton’s “high” goals of intellectual ascension, Kristeva’s notion of the abject—as a developmental stage, and as a trope that operates both psychoanalytically and aesthetically—can be understood as the underside of the Lacanian symbolic.14 Developmentally situated before the mirror stage, the abject offers a counterapproach to patriarchal psychoanalytic theory by considering a confrontation between self and other before a child takes up a permanent position in the symbolic order of language.15 Kristeva’s theory accounts for an experience of otherness that is rooted in the Lacanian real, a prelinguistic state in which a child experiences self and world as continuous and whole. Direct access to the real is lost upon entering into the symbolic through the mirror stage, after which a permanent separation between the inside and outside, or body and image, is established. 16 The image of the Ideal-I , located within the imag inary, is thus established, where “the order of surface appearances… are deceptive, observable phenomena which hide underlying structure.”17 However, in Kristeva’s narrative of the abject, a sense of ambiguous otherness persists in the material realm, as fusions and fissures between inside and outside of the body, or self and other, cyclically repeat.18

14 Elizabeth Gross, “The Body of Signification,” in Abjection, Melancholia, and Love: The Work of Julia Kristeva, eds. John Fletcher and Andrew Benjamin (London: Routledge, 1990), 89.

15 Kristeva, Powers of Horror, 4.

16 Dylan Evans, An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis (New York: Routledge, 1996), 114–16.

17 Ibid., 82.

18 Kristeva, Powers of Horror, 64.

Tanning’s use of cloth in her soft sculptures exemplifies the polymorphousness of Kristeva’s theory of the abject. The medium of textile functions between polarities, as it formally and culturally folds together notions of birth and death and experiences of life in between. Cloth serves as cover and container for the mortal body, taking the form of clothing, upholstery, bed sheets, blankets, funeral shrouds, or wedding veils.19 Humans are born naked but wrapped in cloth upon entering the social world. Dead bodies are ritualistically wrapped in cloth during mourning ceremonies or preservation rites such as mummification. Cloth can be used to swaddle or suffocate,

constrain or comfort, celebrate or shame.20 The medium simultaneously joins and separates nature and culture, maintaining a distance and connection between the body or self and the outside world.21

19 Ewa Kuryluk, Veronica and Her Cloth: History, Symbolism, and Structure of a “True” Image (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1991), 179.

20 Elizabeth Hallam and Jenny Hockney, Death, Memory, and Material Culture (Oxford: Berg, 2001), 117.

21 Claire Pajaczkowska, “On Stuff and Nonsense: The Complexity of Cloth,” in Textile: The Journal of Cloth and Culture 3 (May 2005): 233.

The individual elements that construct Tanning’s soft sculptures—each with its fabric skin stretched around a furniturearmature—can be considered broadly as craft forms, defined by contemporary craft theorist Howard Risatti as “containers, cover ings, and supports.”22 Through the lens of prevalent Western cultural ideologies, craft objects have typically been hierarchically catego rized as “feminine” and “low,” the dialectical “other” to fine art. 23 These objects, which include vessels, clothing, and furniture, serve physiological needs, mediating bodily interactions with the world at borderland sites of the body such as the skin and mouth—thresholds for the experience of the abject, per Kristeva.24 Craft objects can thus be read as coded interfaces, metonymic for the boundaries of the body. Because craft objects serve the physiological needs of the body, they are also reminders of our volatile corporeality: liminal and destined to degrade.

22 Howard Risatti, A Theory of Craft: Function and Aesthetic Appreciation (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 32–3.

23 Two sources expand upon this point: Adamson, Thinking Through Craft, 40 (see note 10); and Elissa Auther, String, Felt, Thread: A Hierarchy of Art and Craft in American Art (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010), 62–3.

24 Risatti, A Theory of Craft, 29.

Such considerations become particularly fruitful in light of Tanning’s assertion that her soft sculpture series is “fragile on purpose, bound to decay. Like the human body.” The pieces’ formal and material associations cultivate a disruptive power that is ampli fied by the works’ address to viewers’ bodies.25 Take, for example, Tanning’s Time and Place (fg. 4), one of the individually-titled works that comprise Hôtel du Pavot. The piece figures as a central hearth, like a fireplace with an attached interior chimney vent. The speckled milk-chocolate tweed of Time and Place reveals itself, on closer inspection, to be made up of tiny fibers in blood red, tan, cream, and dark brown. These are colors of both the inside and out-side of the body. From its obtuse midpoint, the base of the sculpture resolves into the shape of a standard hearth. Yet instead of a rectangular opening

fig. 4 Dorothea Tanning, Time and Place, from Hôtel du Pavot, Chambre 202 (Poppy Hotel, Room 202), 1970–73; Wood, tweed, wool, metal, and synthetic fur; 66 1/8 x 47 1/4 x 51 1/4 in.; Collection of the Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris; image courtesy the Dorothea Tanning Foundation, New York, NY.

fig. 5 Dorothea Tanning, Révélation ou la fin du mois (Revelation or the End of the Month), from Hôtel du Pavot, Chambre 202 (Poppy Hotel, Room 202), 1970–73; Upholstered chair, tweed, and wool; 31 1/2 x 47 1/4 x 33 1/2 in.; Collection of the Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris; image courtesy the Dorothea Tanning Foundation, New York, NY.

leading to its interior, a large tumorlike mass bulges from its façade. The extrusion appears trapped in mid-transmutation, stuck within the process of growth or expulsion. Time and Place calls to mind concurrent visions of birth, afterbirth, miscarriage, or pregnancy, states that, like Kristeva’s abject, mark a “borderline phenomenon…blurring yet producing one identity and another.”26 The hearthlike object appears at once active and passive, alive and dead, crawling and sprawling horizontally and vertically, frozen in concurrent states of degradation and transformation.

25 From Tanning’s 1974 interview with Alain Jouffroy, who asks: “Your sculptures—Ouvre-toi, for instance—are fragile on purpose, bound to decay. Like the human body. Are you detached from the notion of ‘duration,’ from the survival of your work?” Tanning’s response: “These sculptures do show such a detachment. They will, in effect, last about as long as a human life—the life of someone ‘delicate.’”

See: Dorothea Tanning (Sweden: Malmö Konsthall, 1993), 59.

26 Gross, “The Body of Signification,” 94.

At nearly six feet tall, Time and Place performs in still motion for the installation’s viewers, who seem to enact the role of the painted protagonists in Tanning’s Children’s Games. As viewers, we no longer peer into a tiny painted scene; we have become active participants in a physical borderland space. The stitched cloth surface of each piece reads as a skin, just as the viewer’s own skin is encased in cloth garments. Eliciting thoughts of our own abject corporeal fusions and divisions, the sculptures evoke the presence of a material “other” that is disturbingly like ourselves.

A close look at Tanning’s 1970–73 soft sculpture Révélation ou la Fin du Mois (Revelation or the End of the Month) (fg. 5), also from Hôtel du Pavot, expands upon these ideas. Révélation is a supple object, its exterior casing machine-sewn from fuzzy brown tweed. Wool batting and a modified parlor chair serve as the body’s internal skeleton, an amalgamation of folds, lumps, orifices, and extremities, like an exaggerated female body trapped within the seating that supports it. Blurring the line between functional furnishing and figure, the object appears at once active and passive, phallic and feminine, erotic and grotesque. Révélation looks as if it is being consumed, digested, and ejected by itself, reinforcing the knowledge that, like Tanning’s cloth bodies, our own bodies will eventually lose their definition and decay.

Even the wallpaper in Hôtel du Pavot serves as a threshold, a physical and metaphorical location for the cycle of fusion and division that constitutes abjection. Since the work’s original installation, the wallpaper has been updated more than once; as with the body or a textile, it is apt to fade, wear, and degrade.27 Various iterations of the wallpaper have ranged from cluttered floral blooms to gridlike filigree. Across these changes, a faded horizontal rectangle has

continually appeared upon the wallpaper’s surface, as if a painting had been removed from the room. Perhaps pointing to Tanning’s shift from painting to soft sculpture—or from the imaginary to the haptic— this faded rectangle lingers as a ghost of her earlier approach to confronting alterity, on our side of the mirror.28

27 Pamela Johnson, Director of the Dorothea Tanning Foundation, in conversation with the author, Photographic Archives, New York, NY, November 5, 2015.

28 Tanning specified that the wallpaper was meant to be “vintage” in the installation. However, there are no records stating whether or not she made an effort to create this effect of a picture frame having been removed when she reinstalled the piece in various iterations. Pamela Johnson, Director of the Dorothea Tanning Foundation, email correspondence with the author, March 22, 2016.

While Hôtel du Pavot and other works from the soft sculpture series can undoubtedly be seen as a continuation of Tanning’s investigations of borders, the figure, and the self, they are more than simply avatars for her painted figures. They are bodies that devour corporeal space, constructed using historically charged, functional materials that share material connections to the bodies of their viewers. As we encounter these objects, our own bodies pulse and move before the stationary scene. The installation stages frozen transitions between the biological and the social, illuminating unfixed positions of the self in a borderland of embodied contradictions. In her soft sculptures, Tanning offers a transgressive address to otherness and selfhood relevant in her historic surrealist context and still fruitful today. The material “other” serves to remind us that, like the world around us, we are made from liminal matter, destined to age, sag, and eventually decay. But in the meantime—while we all exist as subject and object, autonomous but dependent, on the verge of creation and destruction—the space in between is open for growth, revelation, and revolution.

Looking | Reading | Feeling Image | Text | Body

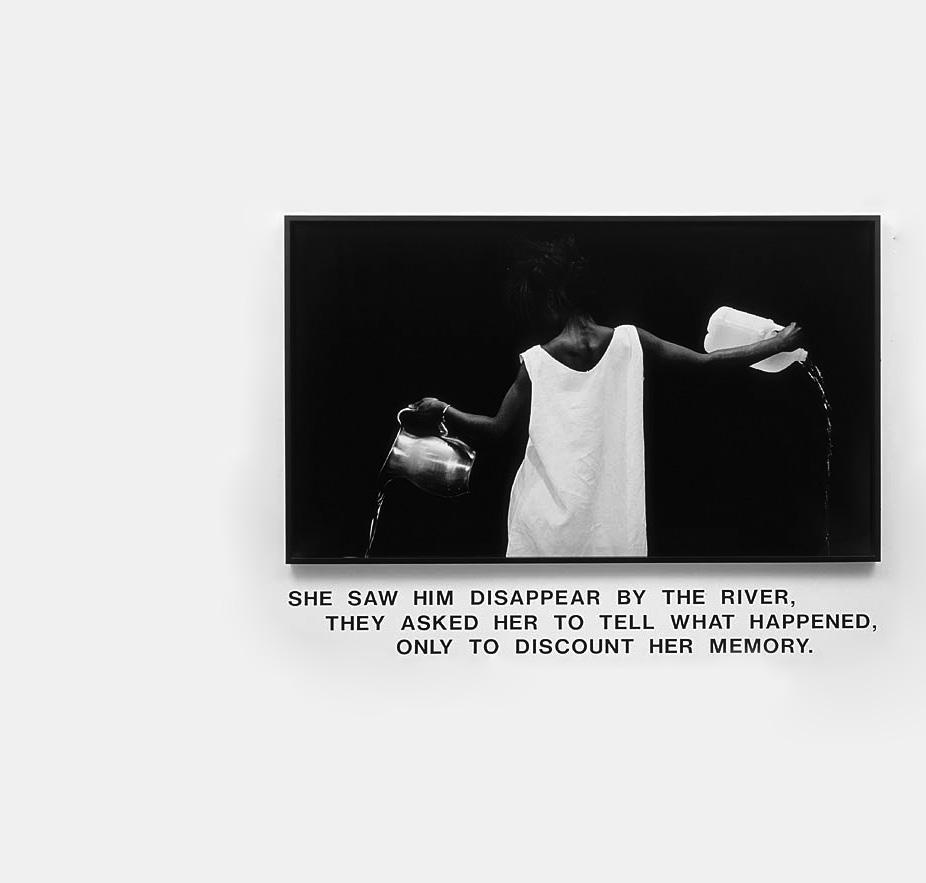

“We all know a classic Lorna Simpson photograph when we see one,” art historian Kellie Jones states at the opening of her 2011 essay on conceptual photographer Lorna Simpson’s nearly three-decade career.1 The statement, not as simple as it appears, leaves its meaning fairly open-ended. Jones follows up with an explication: “…those elegant black female fgures, their backs to us, rejecting any familiarity and yet communicating with us feverishly in accompanying messages located just beyond the borders of the image.” Jones’s casual, almost too casual, opening line is supported by hard descriptive detail. What makes that opening address, the collective “we all” of it, so seductive is also what makes the statement perplexing—and false when left to stand on its own. Jones has subtly invoked an unsettling truth: “we all” come to Simpson’s work with expectations about what we will see—black female bodies, photographed from behind, with strategically placed lines of text. But what if the formula changes? What if one of the variables is substituted for another? If what makes a “classic Lorna Simpson photograph” is its familiarized exchange with the viewer—both a familiarity with Simpson’s signature photographic styles and a presumed familiarity with cultural tropes of race and gender in visual culture—what happens when that weighty exchange dramatically changes form?

1 Kellie Jones, “(Un)Seen and Overheard: Pictures by Lorna Simpson,” in EyeMinded: Living and Writing Contemporary Art (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), 82.In 1994, Simpson began screen-printing photographs onto panels of industrial felt, in a cycle of production I am calling the Felt Period. In these experiments with a new materiality, Simpson also began to change the aesthetic content: her “elegant black female figures” suddenly vanished (fig. 1) . The discomfiting erasure of the figure from these photographs was commented upon at the time by critics and curators well acquainted with the artist’s previous work. In an interview with curator Thelma Golden, for example, Simpson is asked whether her transition away from the black female figure has been symptomatic of exhaustion with talking about identity—specifically race and gender—and its relationship to the body. To this query Simpson responds: “Not really… I am just trying to work through these issues without an image of a figure. My interest in the body remains.”2 In this short exchange, the terms “figure” and “body” are pulled apart from one another and considered separately: the “figure” is what is missing from Simpson’s felt work. The “body” is what remains.

The word “figure” has many meanings. However, within the context of photography, “figure” typically connotes both “an object noticeable only as a shape or form” and “[a] bodily shape or form, especially of a person.”3 Therefore, the “figure” can most usually be understood as a visual depiction of the “body”—a pictorial representation of the physical form of a human being. One necessitates the other, but only in one direction—for the figure to be present, the body has also had to be present at some point; however, the body does not require the figure’s presence to exist. The body can exist on its own, un-pictured. The figure holds significance solely in its flattened and hollow visual depiction. The body, on the other hand, has a phenomenological life—it extends beyond the picture plane and into the physical, experiential world. For Simpson, who until this point in her career had been so easily defined through her depictions of the black female figure, the choice to remove the figure, but simultaneously to insist upon the presence of the body, allows us to privilege who exists within and outside of these marked borders of identity.

Where, then, does the body exist within Simpson’s felt pho tographs when the

removed? The Felt Period shortly follows Simpson’s exchange with Golden, beginning with the 1994 series Wigs (

twenty-one individual black-and-white images of store-bought wigs printed onto white felt panels (fg. 2). The use of

2 Huey Copeland, “‘Bye Bye Black Girl’: Lorna Simpson’s Figurative Retreat,” Jeu de Paume Magazine, May 2013. First published by the College Art Association in Art Journal 64, no. 2 (Summer 2005): 62–77.

felt also signals a dualism: “felt” refers to the photographs’ material surface and, at the same time, invokes the memory of touch or strong emotion. Bodies feel and bodies are felt. Yet, there are no depicted bodies, no human figures, in Wigs (portfolio), only objects meant to stand in metonymically for those figures, meant to invoke the body. Wigs are devices that represent a lack—in this case, a lack of hair— and are being used by Simpson as a part to represent the whole. Next to skin, hair is the biggest signifier of racial difference. Together both hair and skin constitute an “epidermalization” of race.4 This terminology was originally put forth by Martiniquais psycho analyst Frantz Fanon in his book Black Skin, White Masks, in which Fanon recounts being held within the frightened and frightening gaze of a white child on a bus. The term was then redeployed by queer theorist Judith Butler, as a tool of analysis in the 1991 acquit tal of the Los Angeles Police Department officers charged with the brutal public assault, caught on video, of black motorist Rodney King. Butler, using Fanon’s theory to develop the concept of a racial epidermal schema, argued that it was an inherently racist mode of percep tion that allowed for white jurors to read King’s prone and battered body as violent and threatening.5 It is this “epidermal” mode of perception, perpetuated by the visualization of race through the black body, that by the early 1990s had stultified the reception of Simpson’s work, and it is this history in which her black female figures remain caught, making her decision to remove them from the picture plane necessary. Critic Okwui Enwezor describes this predicament in Simpson’s work as “double displacement:”6

The first displacement connects to the question of what it is to be black and female. This frame represents the universal and the particular in her line of enquiry. The second displacement is on the narrower subject of what it means to be African American and American simultaneously.7

4 Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks, trans. Richard Philcox (New York: Grove Press, 2008). Originally published as Peau noire, masques blancs (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1952).

5 Judith Butler, “Endangered/Endangering: Schematic Racism and White Paranoia,” in Reading Rodney King: Reading Urban Uprising, ed. Robert Gooding-Williams (New York: Routledge, 1993), 15–22.

6 Okwui Enwezor, “Repetition and Differentiation: Iconography in Lorna Simpson’s Racial Sublime,” in Lorna Simpson (New York: Abrams and American Federation of Arts, 2006), 114.

7 Ibid.

The figure/body dichotomy established in the exchange with Golden thus exposes a dualism that runs throughout Simpson’s work. The simultaneity of presence and absence is both an affirmation and a negation of identity: black is and black ain’t.8 In Wigs

(portfolio), the store-bought wigs both invoke a cultural fascination with black hair and show us empty, body-less objects that highlight artifice and construction as much as the sublimation of a feminine ideal predicated on whiteness. A second felt series, 9 Props, uses vases blown in black glass as figures—that is, as literal props or stand-ins for unpictured bodies (fg. 3). 9

8 I am borrowing this phrase from late filmmaker Marlon Riggs’s 1994 documentary Black Is…Black Ain’t, which explores the complexities of race, gender, and sexuality and the inability to subsume these identities under one monolithic definition or mode of expression.

9 Limiting the scope of analysis, the Felt Period refers to the years between 1994 and 1998 when the production of works on felt was most significant: Wigs (portfolio) (1994), Wigs II (1994–2006), 9 Props (1995), Public Sex (1995–98), Still (1997).

Later in 1995, however, the Felt Period takes an even more unexpected turn. With the unveiling of the series Public Sex, the figure—the visual depiction of the body—has completely absconded. The individually subtitled photo-text works combine imagery of public and semi-public spaces with cryptic, mostly narrative text panels, all printed on felt and arranged in a grid, which as a whole is roughly life-size. The title heightens the mystery of the empty scenic locations and the subtle eroticism of the text, driving home the “felt” pun with a dark humor. Felt is a dense material made from “natural wool fibre [sic]…stimulated by friction and lubricated by moisture…”10 The process by which the material is created coyly parallels the act of sex.

10 “The History of Felt,” Torb & Reiner Online Shop, accessed December 2015, http://www.torbandreiner.com/felt-history-general.

Compared to Wigs (portfolio) and 9 Props, the absenting of the figure in Public Sex feels more totalizing and extreme. For instance, in The Park (1995), we are presented with a massive, God’seye view of Central Park at night, with the lights of the city framed behind it (fg. 4). Even if one wanted to make out individual figures moving in the dark, it becomes impossible—the vantage point is too high, the ink that renders the trees too dark, the proximity one is allowed to an artwork in a gallery too distant. In this tableau that Simpson has designed, our collective desire to see, and to see clearly, is used against us, as the work invites pondering but denies our gaze anything concrete to latch onto. Denying the figure increases our desire to see it again.11 These voyeuristic—and scopophilic—desires are then mirrored in the narrative of the disembodied subjects in The Park’s paired text panels:

Panel 1: Just unpacked a new shiny silver telescope. And we are up high enough for a really good view of all the buildings and the park. The living room window seems to be the best

fig. 3 Lorna Simpson, Just before the battle, from the series 9 Props, 1995; 3M heat-transferred felt panel in a linen clam-shell box; 14 ½ x 10 ½ in.

fig. 4 Lorna Simpson, The Park, from the series Public Sex, installation view, 1995; Six felt image panels, two felt text panels; Overall: 68 x 67 ½ in.

spot for it. On the sidewalk below a man watches figures from across the path (fg. 5).

Panel 2: It is early evening, the lone sociologist walks through the park, to observe private acts in the men’s public bathrooms. These facilities are men’s and women’s rooms back to back. He focuses on the layout of the men’s room— right to left: basin, urinal, urinal, urinal, stall, stall. He decides to adopt the role of voyeur and look out in order to go unnoticed and noticed at the same time. His research takes several years. He names his subjects A, B, C, X, Y, and O, records their activities for now, and their license plates when applicable for later (fg. 6).

11 Jones, “(Un)Seen and Overheard,” 86.

Though the actions of the subject in each panel—their shameless gazing—remain consistent, the tone and the gravity of their actions change dramatically. Acts that could be described as curious in the first panel would almost definitely be described as invasive and potentially predatory in the second. The invocation of science and research brings to mind how photography has a legacy not only in fine-art making but also in practices closely associated with racially biased modes of quantification, including eugenics and criminalization.

While The Park explores looking, The Bed (1995) considers the counter-perspective of those being looked at. In this diptych, Simpson presents two images of empty beds with white sheets (fg. 6). It is not immediately clear whether these are separate beds in separate rooms or whether they are before-and-after shots of the same bed, the same room. The text panel is equivocal:

Panel: It is late, decided to have a quick nightcap at the hotel having checked in earlier that morning. Hotel security is curious and knocks on the door to inquire as to what’s going on, given our surroundings we suspect that maybe we have broken the “too many dark people in the room” code. More privacy is attained depending on what floor you are on, if you are in the penthouse suite you could be pretty much assured of your privacy, if you were on the 6th or 10th floor there would be a knock on the door (fg. 7) .

The text shifts tonally, as in the panels for The Park, between the sensual and the ominous. Simpson suggests a relationship between surveillance and the missing figures in the image—but were they asked to leave, or were they forced to? The unidentified

fig. 5 Lorna Simpson, The Park, from the series Public Sex, detail of text panel.

fig. 6 Lorna Simpson, The Bed, from the series Public Sex, installation view, 1995; Four felt image panels, one faelt text panel; Overall: 36 x 22 ½ in.

fig. 7 Lorna Simpson, The Bed, from the series Public Sex detail of text panel.

subjects in this diptych are described as “dark people,” and it is this that has apparently prompted the hotel security’s response. The implication being that it is the darkness of the “dark people,” their visible skin color, that has caused the threat. Butler asserts in her essay that the racial epidermal schema “pervades white perception” and “interpret[s] in advance ‘visual evidence.’”12 In the text’s descrip tion, the visual evidence is the couple’s dark skin, suggesting that the black body cannot evade its skin color and, therefore, is forever caught in the racial epidermal paradigm. However, as viewers, we never see the couple, never see their skin, and are never afforded this visual evidence. The black figure—the visualized image of the black body—may be confined within a visual schema of difference, but from our vantage point, the black figure does not exist.

12 Butler, “Endangered/Endangering,” 16.

In Simpson’s felt works, the body is detached from its visual effigy, the figure. But what does this detachment allow Simpson to do? Jones’s essay cites a common misconception that Simpson’s work is specific to the experiences of black womanhood. Because Simpson chooses to work with the black female figure, Jones adds that these works—which implicitly explore the history of racialized violence, trauma, and the aftermath of American slavery—are also often believed to be reflective of the artist’s own experiences as a black woman. The black female figure in Simpson’s photographs has been uncomfortably coupled with Simpson’s black female body.

Art depicting black women can only possibly be about that actual experience; somehow there seems to be no room for wider or “universal” interpretations, no place for “others” to imagine themselves in that picture, in that skin…13

But this is ultimately what The Bed asks us to do—to imagine ourselves in that picture, in that skin. We are asked to feel the white heat of a phantasmic racial gaze as we experience the implied body through our own, suspending, for a moment, the culturally prescriptive contextual information the figure contains in its very outline.

Public Sex problematizes the notion that “we all know a classic Lorna Simpson photograph when we see one.” These works question who all constitutes “we all,” what “knowing” really means, and what marks Lorna Simpson as a photographer and an artist in the midst of this culturally defining moment of the 1990s, the end of twentieth-century art. Removing the figure from the picture plane opens the possibility of broadening the kinds of bodies, the kinds of lived experiences “we all” imagine when we engage with Simpson’s work.

13 Jones, “(Un)Seen and Overheard,” 104.The Allegory of the Screen: Paradox of Representation in Ken Okiishi’s gesture/data (feedback)

Then in every way such prisoners would deem reality to be nothing else than shadows of artifcial objects.

Quite inevitably, he said. –Plato, “Allegory of the Cave”

Being born and held captive in the bowels of a cave, the prisoners in Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave” know nothing of the world outside.1 Behind them, their captors project shadows of puppets by campfre onto the cave’s stone wall, defning the prisoners’ reality through the moving silhouettes (fg. 1). To the prisoners, the shadows in the cave are tangible forms—not representations that point toward other things that are physically absent. Perceived as actual objects, the shadows in Plato’s scenario present a philosophical question about representation—a system of forms that stand in for absent referents, symbolically or cognitively.2 The prisoners’ ability to constitute their reality is dependent on the distinction between physical object and visual image. Yet the conditions of the cave make it impossible for them to understand this very distinction. If a system of representation depends on reference to an absent object in an exterior reality, what happens when the methods of representation fuse the image and its object seamlessly together, collapsing absence and presence, interior and exterior?

1 Plato, Plato: Collected Dialogues, ed. Edith Hamilton and Huntington Cairns, trans. Paul Shorey (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1963), 748, http://www.rowan.edu/open/philosop/ clowney/Aesthetics/scans/Plato/PlatoCave.pdf.

1 Jan Pietersz Saenraedam, after Cornelis Cornelisz van Haarlem, Plato’s Cave, 1604; Engraving on laid paper, 10 ½ x 17 ½ in.; National Gallery of Art, Washington.

Ken Okiishi, gesture/data (feedback), 2015; Oil paint on

.mp4

(color, sound); (left)

in.;

of the artist and Pilar Corrias Gallery.

The convincing power of the “shadows of artificial objects” described by Socrates finds a contemporary parallel in the perceptual assumptions that surround our engagement with screen-based representations. Unlike commercial screen technologies that prioritize user experience, contemporary art practices engage screens beyond their utilitarian functions through material, experiential, and conceptual investigations. In 2015, American artist Ken Okiishi constructed a series of multimedia, screen-based works collectively titled gesture/data (feedback). Okiishi paints on the surface of digital flat-screens that are simultaneously playing a pre-recorded digital video; using the screen as a site of perceptual experimen tation, Okiishi paints in response to the video image that has become the support for his mark-making. The replication of images and mediums displayed on Okiishi’s screens thus instantiates the vast representational possibilities generated through screen-based engagements. Contrasting the gestural painting with the moving video even as they are combined on a stationary digital screen, Okiishi’s work performs technology’s ability to replicate almost anything. This multivalent capability leads us in turn to understand what we view on-screen as undifferentiated from the object it represents, the indexical handmade mark reduced to its virtual corollary. This fusion problematizes Plato’s traditional model of representation, which posits the necessity of an object or concept as existing prior to, and separate from, its depiction. Replicating the visual conflation of object and image found in the cave, the tech nological screen can be positioned as a new site of self-referential representation. Okiishi’s gesture/data (feedback) produces on-screen images that collapse the role of the shadow into its referent; they appear as one and the same, the shadow extended by its representation and reiteration of itself. In doing so, (feedback) reveals a paradox of screen-based imagery in our increasingly electronic and digital visual landscape that calls attention to how it can potentially reshape our conception of visuality.

In one diptych from Okiishi’s gesture/data (feedback) series, two flat-screens have been turned vertically and installed side by side—a small screen on the left and a slightly larger screen on the right (fg. 2). Each screen is physically marked on its glass surface by an accumulation of expressive strokes of paint, spiking horizontally outward from the right of the screen in cadmium red, mint green, and an array of murky grays. On the left screen, the marks’ sense of energy contrasts the digital gradient of a powder-blue background playing beneath it. Re-rendered in video on the right screen, the

2 Anne Freadman, “Representation,” in New Keywords: A Revised Vocabulary of Culture and Society , eds. Tony Bennett, Lawrence Grossberg, Meaghan Morris (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2005), 306–09.entire combination of video and paint from the smaller screen is reproduced, scaled to fit the second screen’s larger size. The same explosive marks that appear as a video background have also been recreated a second time in paint on this screen’s glass surface, mul tiplying the number of marks in the screen’s frame.

This mediated repetition of image and surface conflates the two video-plus-paint compositions in a way that forces us to consider the screen as a specific model of representation that accounts for its own mediation. The two screens mirror one another, constructing a complicated layering of self-referential representations. From left-to-right, the flow of production reads; digital video, paint on screen, digital video of paint, and painted reproduction of digital video, which then folds back into (feedback)’s total diegetic image as a small painted screen with video, then a larger painted screen with video, and finally a diptych. The back-and-forth between these layers and semiotic references centralizes the screen as a key ele ment in the production and reproduction of images.

The commonplace presence of the technological screen is largely responsible for contemporary culture’s widespread privileging of visual representations over somatic experience. The awesome ability that smart devices possess to reproduce images, text, video, real-time feeds, interactive exchanges, sound, and haptic stimulation leaves no question as to why screen-based technology has become the primary format for engaging with such an array of media.3 To media scholar Lev Manovich, the cultural demand to display new forms of media in turn drives the development of screens. He argues that new technologies have been constructed in order for each kind of media to come into being; the canvas served as a surface on which to create images with paint; the computer screen evolved from the technology of radar, and so on, each invention formally connected to those that came before it through their consistent rectilinear shapes.4 Manovich states that technologically produced images are “synthetic,” meaning that their representations of reality exist outside human visual potentiality, due to the capacities of the computerized platform (fg. 3). 5 His approach assumes that screens serve a singular purpose: to define what they depict as a product of the screen, intrinsic to it, rather than as a re-creation of something exterior to the technological device. If the screen exclusively produces synthetic realities, then screen-based represen tations are conflated to the devices themselves, implying a refusal of anything external to their projections.

3 “The New Multi-screen World: Understanding Cross-platform Consumer Behavior,” Google, last modified August 2012, accessed February 6, 2016, http://services.google.com/fh/files/misc/ multiscreenworld_final.pdf.

4 Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001), 99.

3 In another unit from the gesture/data (feedback) series, Okiishi’s use of digitized media emphasizes Manovich’s notion of technological imagery as a “synthetic” reality.

Ken Okiishi, gesture/data (feedback), 2015; Oil paint on flatscreen televisions, feedback, .mp4 files (color, sound); (left) 48 in.: 42

x 24 x 2 in.; (right) 40 in.: 35

x 20

x 2 in.; Courtesy the artist and Pilar Corrias Gallery.

4 Ken Okiishi, gesture/data (feedback), detail, 2015 (see figure 2 for full image).

5 “It is a realistic representation of human vision in the future when it will be augmented by computer graphics and cleansed of noise. It is the vision of a digital grid. Synthetic computergenerated imagery is not an inferior representation of our reality, but a realistic representation of a different reality.” Manovich, Language of New Media, 202; italics original.

The conflation of media and their screens is problematized when a viewer attempts to determine an image’s exterior references. Scholar Jonathan Crary argues that the rapid development of visual technologies in nineteenth-century Europe changed the ways in which people understood vision by introducing machines—such as the zoetrope—that split vision from our bodies, transforming it into something reproducible by incorporeal means. The reproduction of vision via technology creates what Crary refers to as an obedient “observer” who complies with the representational logic facilitated by the technological device. It is up to the observer to distinguish the disembodied, reproduced, technological imagery as an articulation of reality exterior to the body.6 But the machine’s ability to artificially mimic bodily vision through its scientifically produced replications can make it difficult for the observer to differentiate the mechanical representation from human vision.7 If the observer fails to make this distinction, then mechanically—and therefore, technologically—produced vision can become perceptually synony mous with corporeal vision. Expanding on Crary’s argument about nineteenth-century technologies, when the synthetic reproductions of vision are produced within the context of the technological screen and recognized by the observer as interchangeable with corporeal vision, I argue that the resulting misconception—the conflation of synthetic and actual representations on-screen—affects our very concepts of visuality for the twenty-first century.

6 Jonathan Crary, Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996), 26.

7 The distance of technology from everyday understandings grants it a status of “truth” that comes with the logical and procedural processes of science. See: Edward A. Shanken, “Historicizing Art and Technology: Forging a Method of Firing a Canon,” in MediaArtHistories, ed. Oliver Grau (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004), 43–70.

Okiishi’s diptychs do not propose that the technological is an alternative to corporeal vision, but rather frame the screen’s representations as incorporating both forms. This blurring of technologically produced vision and corporeal vision is palpable in the shifting nature of (feedback)’s images. Toward the top of (feedback)’s larger screen, an arc of light purple paint almost breaks the picture plane. Compositionally above it but visually beneath it, a copy of its form in midnight blue is reproduced in video (fg. 4). The dark blue mark is the video recording of the smaller screen’s composition, and the purple mark of paint on the larger screen’s surface was copied from

the video playing in the background. The rendering of the same mark in different materials manifests Crary’s problematic of the observer being able—or not—to distinguish between corporeal/material and synthetic/technological representations. However, by layering the different iterations of the mark in the same space, Okiishi suggests the possibility of reconciling their material separation through a flat tening of visual difference. The relationship between these two forms of representation in (feedback) maintains the distinction between technological and corporeal vision but, by doing so, produces a composite that increases the likelihood of the observer misinterpreting it as undifferentiated. Okiishi’s use of the word “feedback” in the title implies a response, or better yet, a chain-reaction that results from an output being reinserted into a system as an input, creating a looping effect. (feedback)’s combinations are a cumulative endeavor, a palimpsest of loops rather than a substitution of one image for another. To recognize the difference between representations—even as one views them simultaneously—allows Okiishi’s viewer to contemplate a generative model of imagistic production that accounts for both forms—material and digital—fusing as ubiquitous elements of contemporary visual experience.

Through the layers of material pigment, technological device, and digitized video, Okiishi’s diptych produces a new type of vision that marries the moving to the static image—a feat unachievable without technological aid. Cultural studies scholar Vivian Sobchack uses the term “technological vision” to describe this new model of vision that allows us to understand and engage with media in ways that extend beyond the limitations of analog production. Sobchack claims that, as a medium, film is “a subject of its own vision, as well as an object for our vision,” articulating a dual register for moving images that can be extended to the ephemeral quality of devicebased media.8 Within (feedback)’s larger screen, the video footage of the smaller screen becomes the subject of the larger screen’s vision, while remaining an object to the viewer. Turning this duplicity of technological vision onto itself, Okiishi reveals the dual role of the screen as both object and image.

8 “Thus, perceived as the subject of its own vision, as well as an object for our vision, a moving picture is not precisely a thing that (like a photograph) can be easily controlled, contained, or materially possessed—at least, not until the relatively recent advent of electronic culture.” Vivian Sobchack, “The Scene of the Screen,” in Carnal Thoughts: Embodiment and Moving Image Culture (Berkeley: University of California Berkeley Press, 2004), 148–49; italics original.

The interwoven relationship between material and synthetic production that occurs within (feedback)’s frames creates a closed circuit of reference. The new painting created from the digitally reproduced video mirrored on Okiishi’s larger screen inverts the traditional system of representation that refers to a physically absent object.

fig. 5 Some units from the series are not diptychs, concealing the presence of an “original.”

Ken Okiishi, gesture/data (feedback), 2015; Oil paint on flatscreen television, feedback, .mp4 files (color, silent); 42 ³ ₁₀ x 24 ⁴ ₁₀ x 2 in.; Courtesy the artist and Pilar Corrias Gallery.

(feedback) performs an agency of synthetic representation, activating “technological vision” as a model of vision believable enough to generate copies of its own likeness (fg. 5). 9 When the technological screen synthetically reproduces the somatic gesture—the brushstroke— the representational convention of symbolic reference collapses onto itself. Supplanting the singular object for a synthetic visualiza tion problematizes an observer’s relationship to the physical world, implying that the differentiation between fact and fiction is no longer relevant, or even existent. The polarizing model of material versus synthetic representations, corporeal versus technological vision, and the vectors of reference and genesis between them become interchangeable, conflated and enabled by the technological screen. The outcome is an image that refers to the concept of representation by using another iteration of itself as its referent.

9 For more on the art historical practice of copying the techniques of master painters as a means of authenticating originality and its effects on representation, see: Richard Shiff, “Representation, Copying, and the Technique of Originality,” New Literary History 15, no. 2, Interrelation of Interpretation and Creation (Winter 1984): 333–63, accessed November 6, 2015, http://www.jstor.org/stable/468860.

It is here that the paradox of representation circulated through technological screens connects most strongly to Plato’s model of the cave. The technological screen convinces the viewer that its imagery is synonymous with the objects it represents, mimicking the notion of the shadow being both referent and object to the prisoners in the cave. In (feedback), the screen allows the image of paint to be represented twice—the video mirroring the paint of the first screen, mirrored again by the reproduced marks on the second, larger screen. This doubling within the diptych creates a paradox: if the paint is presented as both a physical object and a digital image, then each reproduction simultaneously refers to itself as an absent object and a present image. In this way, when the technologically based (i.e., materially absent) image is considered as the (material) presence of a technological screen, traditional modes of representation begin to fail, unable to accommodate the screen’s fusion of referent and sign.

In order for the traditional model of representation to function, an exterior must always exist. Yet, within the technological screens of (feedback), this necessity is denied. The interaction between referents in (feedback)’s dual screens mirroring each other constructs the exterior of its diegetic space as a technological—and therefore interior—representation of itself.10 (feedback)’s production and reproduction of images on material and digital levels posit that the technological screen functions as a nexus for new production— a “blank canvas” suited for the generation of indexical gestures.11 Thus, to consider the technological screen as an active agent in

contextualizing its displays produces a new model of visuality specific to the fusion of digital and analog mediums that coexist in screen-based representations.

10 Media scholar Alexander Galloway defines the liminal exchange of mediatic forms in a diegetic space as “the interface effect.” This effect involves the contextualization of an image’s logic through a focus on the maintenance of either an interiority or exteriority.

See: Alexander Galloway, The Interface Effect (Cambridge, England: Polity Press, 2013).

11 For more on the use of the term “index” within an art context, see: Rosalind E. Krauss, “Notes on the Index: Part I,” in The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1986), 196–209.

Allowing the technological image to inscribe itself as the foreclosure of an exterior forces us to ask whether we can continue to consider screen-based media as “artificial.”12 Ken Okiishi’s gesture/data (feedback) presents us with an unlikely amalgamation of gesture and data at a cultural moment in which conceptions of representation have been thrown into turmoil. In Plato’s narrative, Socrates speculates as to what would happen if a prisoner were to escape the cave and enter the world outside, beyond previous horizons of perceptual knowledge. The philosopher’s answer, of course, is that the escaped prisoner would choose to return to the comfort of the cave. Our own assumptions about screen-based representations as indistinguishable from traditional models provides us a similar comfort: we are enthralled by the idea that screens passively and innocently mediate rather than actively engage and create. On-screen media are our contemporary shadows, while the cave that obstructs our access to exterior context becomes the screen itself. The soft glow of the screen providing us with endless simulations seems preferable to the harsh light of the sun that illuminates a foreign, exterior world. In the all-encompassing simulation of the screen, the seemingly illogical return to the cave transforms from classic speculation to contemporary reality.

12 This substitution of synthetic representation for a metaphysical “truth” predicated on reality echoes the concerns of cultural theorist Jean Baudrillard as expressed in his 1994 book Simulacra and Simulations. See: Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulations, trans. Sheila Faria Glaser (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1994).

Systems, Interrupted: Disrupting systems of social order and visual representation

Restructuring Respectability, Gender, and Power: Aida Overton Walker Performs Modernity

Veronica JacksonFrom the beginning of her onstage career in 1897 to her death in 1914, Aida Overton Walker was a vaudeville performer engaged in a campaign to restructure and re-present how African Americans, particularly black women in the popular theatre, were perceived by both black and white society. A de facto member of the famous minstrel and vaudeville team known as Williams and Walker (the partnership of Bert Williams and George Walker), Overton Walker was vital to the theatrical performance company’s success. Almost from the beginning, she was their leading lady, principal choreographer, and creative director. Most importantly, Overton Walker was on a mission to execute her articulation of racial uplift while performing her right to choose the theatre as a profession (fg. 1).

This essay’s overarching aim is to examine Overton Walker’s fearless enunciation of the concepts of racial uplift as meditated through a feminist position—in other words, a belief that men and women are equal. During the early twentieth century, African American women were typically limited in their methods of participation for creating positive black images. Patriarchal domination confned black women’s respectable professions to those of schoolteacher, housewife, or domestic. Yet Overton Walker’s restructuring and re-presenting of these perceptions of black women refected her embodied pursuit of the strategy embraced by the educated,

middle-class, African American elite, whose calculated goal was to deliver “respectable” images of black people while also promoting “exemplary behavior by blacks.”1 Extending well beyond the vocations prescribed for black women, Overton Walker’s contribution mani fested through her choreography and dance, comedic and dramatic performances. A reexamination of her oeuvre therefore allows us to consider Overton Walker explicitly as a woman countering the black male elite’s domination over the ideology of racial respectability.

1 Kevin K. Gaines, “Racial Uplift Ideology in the Era of ‘the Negro Problem,’” Freedom’s Story: Teaching African American Literature and History (National Humanities Center), accessed October 7, 2015, http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/tserve/freedom/1865-1917/ essays/racialuplift.htm.

This was a complex time in American society. Racism in the early 1900s worked in tandem with blackface minstrelsy, which presented derogatory and demeaning depictions of African Americans and reinforced white supremacy. Jim Crow laws restricted black people’s economic advancement, while the white hegemonic system made it difficult for blacks to grow businesses, despite an economic boom flourishing all around them. The marketing of a “real” or authen tic blackness emerged in response to this climate, which largely circumscribed entrepreneurship for black people to manual labor or menial positions. In the midst of these restrictions, popular theatre aimed at white and black audiences alike became available to black artists as a market. For the purposes of economic empowerment, black entertainers in the early 1900s established themselves as real or authentic purveyors of African American cultural expression, distinguishing their acts from the imitative techniques of white minstrels. Marketing themselves as performers who possessed the ability to disseminate and define a true black culture was an astute fiscal strategy as well as a political one. The tropes of cultural authenticity embodied in song, dance, and humor were deployed by the Williams and Walker Company in order to define their version of performing “real blackness” on the vaudeville stage. Because white actors were mimicking other white performers lampooning the darky coon, their rendition of blackface minstrelsy was an act of imitation thrice over, a re-creation of an inherited stereotype. In contrast, as performance scholar and cultural historian David Krasner notes, “Williams and Walker [and a few of their peers in the entertainment business] displayed throughout their writings and actions an acute awareness of the ‘real’ as a cultural signifier and marketing tool.”2 Overton Walker “contributed to the creation of a revised American realism…[that] countered hegemonic and racist depictions [of blacks] by exploiting the desire for the real among whites.”3 The Williams and Walker Company’s version of onstage blackness was, more over, subversive. Its coded messages contradicted minstrelsy and

were aimed at and interpreted by black audiences while remaining illegible to white ones. For example: Williams and Walker often downplayed the stereotyped southern coon dialect and accentuated the clever and witty repartee between the main characters—Jim Crow (Williams) and Zip Coon (Walker). Traditional roles called for Jim Crow to be the indolent southern darky and Zip Coon the citi fied northern Negro speaking in malapropisms, but Williams and Walker dispensed with the common lampooning, presenting their double-conscious interpretations instead.

2 David Krasner, “The Real Thing,” in Beyond Blackface: African American and the Creation of American Popular Culture, 1890–1930, ed. W. Fitzhugh Brundage (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2011), 99.

3 Ibid., 101.

This is a paradoxical situation. Real or authentic blackness was offered as an immersive experience that involved the haptic as well as the visual senses. Krasner explains, “The ‘realness’ had to be transferable; in other words, whites not only had to observe ‘real’ blackness, they had to experience it as well. ‘Blackness’ had to be made marketable, a species not only in the showcase window…but something a buyer might sensuously ‘adorn.’”4 Overton Walker and her cohort took advantage of the demand for black realness and made black cultural expression available to their white society patrons at the same time as they were entertaining and delivering the message to their black audiences that minstrelsy could not define them. A central vehicle for this complex exchange was the cakewalk, a dance craze that took hold at the turn of the twentieth century (fg. 2).

4 Ibid., 108–09.

Both black and white Americans were swept up in the cakewalk frenzy; the dance was, as Krasner writes, a way in which the white elite went about “othering, without disrupting white notions of cultural behavior…. Cultural identification with blacks…supplied motivation for whites eager to explore black cultural experiences as an excavation into the exotic world of what they thought was… the inferior, but often fascinating, Other.”5 These whites explored exoticism by sampling a signifier of black culture, the cakewalk, as taught by a black instructor, Overton Walker.

In the early 1900s, a mostly urban white nouveau riche sought to learn the cakewalk as a way to define their up-to-dateness and to escape from tradition. Such definition was important because emerging middle- and upper-class white Americans had

5 David Krasner, “Rewriting the Body: Aida Overton Walker and the Social Formation of Cakewalking,” Theatre Survey 37:2 (November 1996): 79–81.fig. 2 Overton Walker and Walker perform the cakewalk in In Dahomey, 1903. Tatler notice.

fig. 3 Cakewalk composite image (Southern plantation dance and Civil War cotillion), 1861 and 1864.

obtained their social status through money, not birthright.6 Krasner states: “For the new middle and upper classes, wealth was replacing lineage…the ‘formerly exclusive corridors’ of aristocracy by birth were being usurped at the turn of the century by ‘a conglomerate host that has climbed up from the lowlands of mediocrity,’ thereby acquiring social distinction ‘solely through the expenditure of wealth.’”7 The cakewalk was a commodity that could be bought and sold, and learning the cakewalk from the “real” or authentic instruc tor—Overton Walker—became the white elite’s cultural signifier.

6 Krasner, “Rewriting the Body,” 78.

7 Ibid.

Overton Walker brought authenticity to performing and instructing the cakewalk through her knowledge of its African roots and emergence as a dance conducted by enslaved blacks on the plantation. Many myths surround the origin of the cakewalk. Overton Walker biographer Richard Newman presumes that the dance developed “when slaves imitated, exaggerated, and in fact satirically mocked and mimicked formal white cotillions.”8 Dating from eighteenth-century France, cotillions are formal dances usually performed on the occasion of the debutante’s coming out.9 Once again paradoxically, under Overton Walker’s tutelage, the cakewalk exemplified a series of authenticities and imitations realized by a black female performer who, while revamping and bringing her signature grace to the dance in the 1890s, was imitating white minstrels. Such minstrels, through their inclusion of the cakewalk in their finales, were imitating black slaves on the plantation, who themselves were pulling from a West African festival dance while satirically parodying their white master’s formal cotillions (fg. 3). 10 Through the process of instructing the “better classes of white people on both sides of the ocean”11 how to

and thus integrating into white society, Overton Walker proved that a black

could make positive contributions

to if not better than those of respected male professionals.

8 Richard

9

the race,

10

11

Overton Walker was the “real cakewalker.” She branded herself as the authentic person from whom to learn the dance. As a result of her manipulation of the art form, she has been hailed by scholars such as Krasner as contributing to American modernity by transforming the dance from “old fashioned and vulgar to modern and stylish.”12 Overton Walker was the go-to person for the white upper- and middle-class society to learn the cakewalk, and receiving instruction from her was one way for them to demonstrate social status.13 She had either instructed or been invited to entertain some of the most noted people in high society, including British royalty; in 1903, while touring with In Dahomey in London, she privately tutored leading sophisticates in the art of cakewalking.14 She per formed a solo and afterward was granted an audience with King Edward VII, who, famous for his affections for beautiful women, bestowed upon her a diamond brooch.15

12 Krasner, “Rewriting the Body,” 80.

13 Krasner, “The Real Thing,” 109.

14 Jayna Brown, Babylon Girls: Black Women Performers and the Shaping of the Modern (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008), 133.

15 Newman, “‘The Brightest Star,’” 470.

Overton Walker’s performances for and instructions to royalty and the white moneyed class in America exemplify how she used her talents and expertise to bridge the class and cultural divides. On and off the vaudeville stage, she trenchantly applied her performance skills to present a positive public display of her race and her gender. Her work was celebrated by white society, but more importantly, Overton Walker marketed herself as the premier cakewalker while simultaneously inventing an alternative role for black women to embody. She used her performances as tools for promoting herself as well as personifying racial uplift. This is demonstrated in her article in Colored American magazine, directed at the black elite:

It has been my good fortune to entertain and instruct, pri vately, many members of the most select circles—both in this country and abroad—and I can truthfully state that my profession has given me entrée to [white] residences which members of my race in other professions would have a hard task in gaining if ever they did…. The fact of the matter is this, that we come in contact with more white people in a week than other professional colored people meet in a year and more than some meet in a whole decade.16

16 Aida Overton Walker, “Colored Men and Women On the Stage,” 571.

Overton Walker was fully aware of the opportunity her position as a performer afforded her to not only integrate white society, but to remind the black intelligentsia that she had accomplished said task. Despite the black elite’s negative characterizations of the theatre as “unwholesome” and a “threat to racial progress,”17 she emphasized her contribution to racial respectability by stating twice that her pro fession engages with more white people than the other “respected” professions—an engagement that contributed to uplift because it demonstrated African Americans performing “exemplary behavior.”