THE PRO BONO AWARDS

FITZROY LEGAL SERVICE: THE FIRST SIX MONTHS, 50 YEARS AGO

RECKLESSNESS AND THE CRIMINAL LAW

THE PRO BONO AWARDS

FITZROY LEGAL SERVICE: THE FIRST SIX MONTHS, 50 YEARS AGO

RECKLESSNESS AND THE CRIMINAL LAW

Featuring essays from the Hon Ken Hayne AC KC, Gavin Silbert KC and more

PLUS: All the glitz and glamour of the 2023 Victorian Bar Dinner

If you are one of the many Australian home owners facing the fixed rate cliff this year, it is crucial you prepare now to put yourself in the best position.

As Australia’s only mortgage broking service exclusively for lawyers and barristers, we understand the lending landscape with a specific legal focus and use this expertise to achieve the best solution for you.

Official partner of the Victorian Bar. Members receive $500 cashback at loan settlement.*

(02) 9030 0420

Around Town

2023 Silks Bows Ceremony 10

The generosity of allies: a report 12 from the 2023 Victorian

38 The case for KEN HAYNE

42 The case against GAVIN SILBERT

46 The High Court, faith, and the virtue of charity

DANIEL AGHION AND RABEA KHAN

48 Recklessness and the criminal law NICK GADD

50 Surprised by joy: reflections on life as President of the Court of Appeal

MAREE NORTON AND EMMA POOLE

53 The more things change, the more they stay the same

KRISTINE HANSCOMBE

54 Ranitha Gnanarajah: international woman of courage

MEMBERS OF THE OCTOBER 2018 READERS GROUP

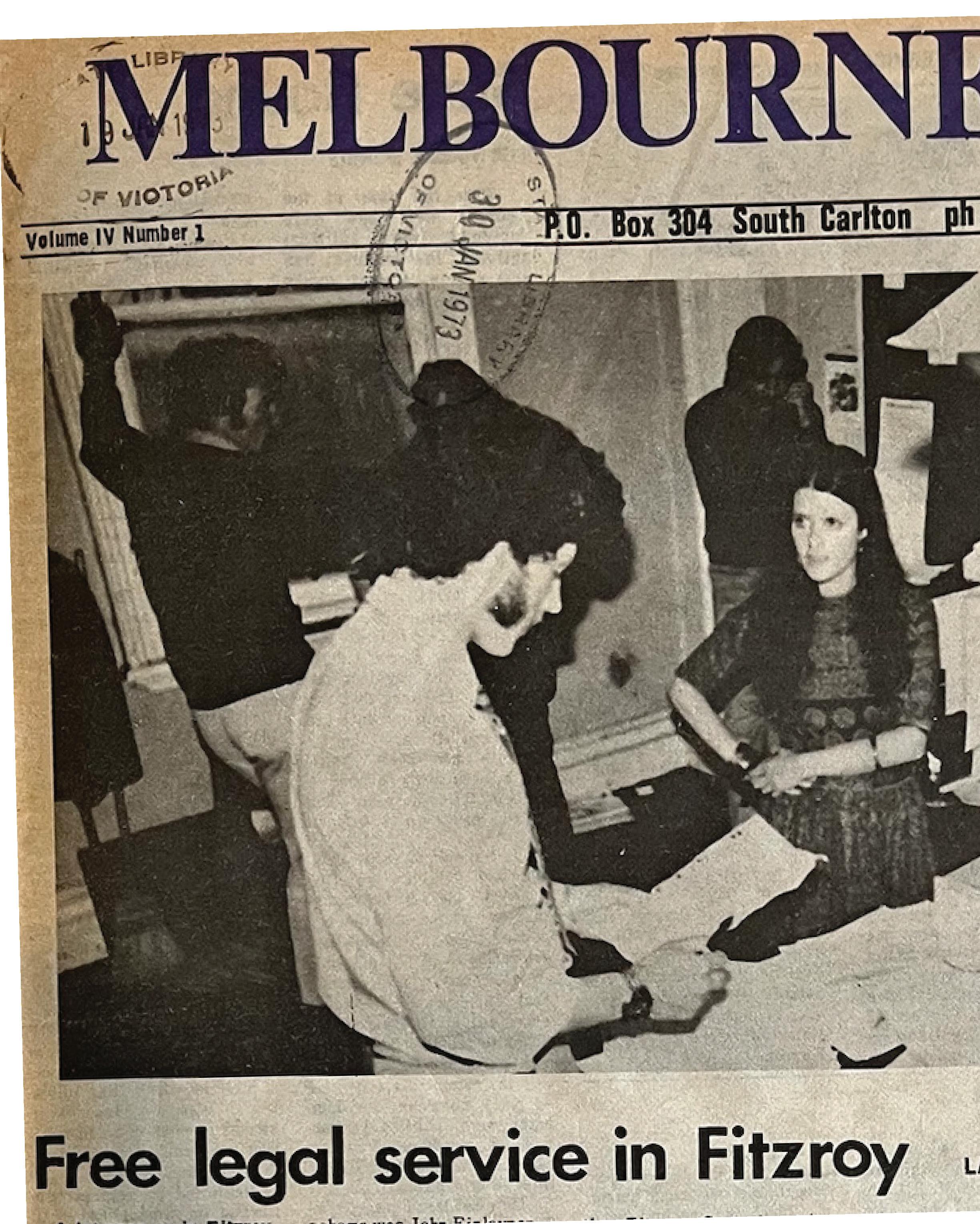

56 Fitzroy Legal Service: the first six months, 50 years ago

BENJAMIN LINDNER

Bar Lore

60 Battel acts

ROBERT LARKINS

Back of the Lift

62 Adjourned Sine Die

64 Silence All Stand

67 Gonged!

67 Vale

Boilerplate

74 A Bit About Words

JULIAN BURNSIDE

76 Language Matters

PETER GRAY

78 Music Review

ED HEEREY

82 Restaurant Review

VBN EDITORS

Editors: Banjo McLachlan, Luke Merrick, Maree Norton, Jesse Rudd VBN Committee: Edward Heerey KC, Stephen Warne, Ashlee Cannon, Harry Forrester, Sandip Mukerjea, Joel Silver, Emma Poole, Alexander Di Stefano, Lara O’Rorke, Michael Wyles

Contributors (in alphabetical order): The Hon Paul Anastassiou KC, Elizabeth Bennett SC, His Honour Judge Brookes, Julian Burnside AO KC, Julie Buxton, Alex Campbell, Ashlee Cannon, Terry Casey KC, Georgina Costello KC, Maureen Daly, Julia Frederico, Felicity Fox, Nick Gadd, Sue Gatford, Janine Gleeson, Timothy Goodwin, the Hon Peter Gray AM, Kris Hanscombe KC, Edward Heerey KC, the Hon Ken Hayne AC KC, Rabea Khan, David KelseySugg, Caroline Paterson, Neil Rattray, Jesse Rudd, Robert Larkins, Elle Nikou Madalin, Carly Marcs, Julian Murphy, Maree Norton, Justin O’Bryan, Emma Poole, James Samargis, Gavin Silbert KC, Anna Svenson, Peter Willis SC, Raini Zambelli

Photography/Images (in alphabetical order): Darcy Campbell for Red Crush Media, Eugene Hyland, Felicity Fox, Haim Kadar for Magnet Me, Irene Dowdy for ID Photography, Neil Prieto, Peter Bongiorno

Publisher: Victorian Bar Inc., Level 5, Owen Dixon Chambers East, 205 William Street Melbourne VIC 3000.

Registration No: A 0034304 S

The publication of Victorian Bar News may be cited as (2023) 173 B.N. Opinions expressed are not necessarily those of the Bar Council or the Victorian Bar or of any person other than the author.

Advertising: All enquiries, including requests for advertising rates, to be sent to: Matthew Reddin, Victorian Bar Inc., Level 5, Owen Dixon Chambers East, 205 William St, Melbourne, VIC 3000. Tel: (03) 9225 7111

Email: matthew.reddin@vicbar.com.au

Illustrations, design and production: Guy Shield – guyshield.com

Printed by: Southern Impact – southernimpact. com.au

Contributions: Victorian Bar News welcomes contributions to vbneditors@vicbar.com.au

As long time readers, first time editors of Victorian Bar News—some with experience on the Bar News committee, some without— we are delighted and a little nervous to take on the legacy of editors who have gone before us. And to do so at an interesting time in the life of our Bar, and our nation.

Unsurprisingly, the calling of a referendum on Indigenous recognition in the Constitution—the 45th referendum since Federation and the first in over 20 years—has sparked strong and divergent views within the Bar. We are a community of professional arguers, after all. By the time this issue is published, we will all have had an opportunity to vote in a poll as to whether or not the Bar should formally support the proposed constitutional amendment. Debate on the appropriateness of doing so has featured in the mainstream media, at times in a way that may have made members on both sides of the debate feel at odds with colleagues, despite close working relationships and friendships.

Within these pages you will find articles exploring and recording debate on the proposed amendment of our Constitution. We begin with a piece prepared by members of the Indigenous Justice Committee, reflecting on the nature of the Constitution generally— as both a “compromise” and a “blueprint for the good life”—and the road that has led Australia to consider this particular constitutional amendment. Next, two prominent

members of our Bar have taken the time to explain the reasons they will be voting “yes”, in the case of the Hon Ken Hayne KC, or “no”, in Gavin Silbert KC’s case.

We don’t pretend that these articles represent the full range of views on the subject, however we hope that they fairly reflect many of the key arguments and considerations on either side of the debate. We ask that you read these pieces in the spirit in which they are intended: as a contribution to an important constitutional debate of our time. The coverage offers each of us an opportunity to gain a better understanding, not only of our own position on the Voice, but also of why some friends and colleagues might cast a different vote on polling day.

This edition of Bar News also celebrates the ways in which we have come together, as colleagues, friends, and as part of our broader community. We feature an article on the Criminal Bar Association conference, at which members mixed gin with discussions on important developments in criminal law, and the need for positive strategies for dealing with vicarious trauma.

International Women’s Day provided an ideal occasion for the unveiling of two new portraits—of the Hon Justices Kenny and McMillan—in the Peter O’Callaghan Portrait Gallery. On 4 May, 48 new barristers joined our ranks; they introduce themselves in our Readers’ Digest piece. Most recently, on 26 May, we came together for a night of chatter and taffeta at the annual Bar Dinner.

As we welcome the appointment of Chief Justice Mortimer to the Federal Court, we also feature a profile on recently retired President of the Court of Appeal, the Hon Chris Maxwell, who again highlights the importance of collaboration and collegiality. And see Carly Marcs’ piece about how a few emails to members of the Bar and Bench helped to raise over $34,000 for Giant Steps, a specialist school for

International Women’s Day provided an ideal occasion for the unveiling of two new portraits—of Justices Kenny and McMillan—in the Peter O’Callaghan Portrait Gallery.

children on the autism spectrum.

As usual, members have been generous in providing diverse and thought-provoking pieces for publication. We encourage you to take the time to read a piece written by Daniel Aghion KC and Rabea Khan about a recent High Court decision in which religious concepts of charity and equity, “tzedakah” and “zakah” featured in Justice Edelman’s consideration of the administrative law concept of legal unreasonableness. And don’t miss Robert Larkins’ piece on the (surprisingly recent) history of trial by battle. Regular contributors, the Hon Peter Gray and Julian Burnside KC, have provided pieces on matters dear to many of us: grammar and (leading and non-leading) questions.

Recognising the vice of all work and no play, Ed Heerey KC’s music review challenges us to listen to some new music this winter, and provides his tips on artists worth checking out. And in a throwback to journalism of days gone by, we eds offer up a review of Marion following a recent “working lunch”

at that fine Fitzroy establishment.

Thanks to all those who have contributed to this issue, including the Committee and Bar Office staff who have worked hard to bring it to you. Thanks in particular to Sharni Doherty, whose assistance has been invaluable. Like us, Sharni and many other members of the team are new to the role. We thank all involved for their patience as we learn the ropes. Special thanks must go to our professional contributors, Guy Shield and Peter Barrett, without whom this publication might well be printed and stapled on a BCL printer, with emojis and pixelated photos featuring heavily on the front and back covers, and unformatted text in between. It takes a village.

PS Readers might note the absence of regular features of Bar News, such as Letters to the Editors and the quotable quotes of Verbatim; unfortunately our inbox has been starved of such content of late. Please do write to us in the coming months if you have feedback on this edition or access to a choice piece of transcript: vbneditors@vicbar.com.au.

SAM HAY

As predicted in the last issue of VBN, since I took on the role of President in November, things have been busy. At times, they have been quite intense. I wanted to take this opportunity to express a few thoughts about our college that have occurred to me over the last six months.

First, we are a group of highly intelligent, articulate and motivated people. As you would expect, there are many different views held at the Bar. Many members hold their views passionately and they are not at all afraid to express them. From a Bar Council perspective, that can be challenging at times, but there is no doubt it should be celebrated. Despite the stereotypes that can easily be called to mind, we are far from a group of homogenous conformists. Whatever may have been the case 50 years ago, there is real diversity of thought amongst our current membership.

Second, those differences of opinion can lead to lots of disagreements. Just as in the community, some of those disagreements run deep. However, despite some people speaking at times in overbroad and apparently uncompromising terms, we always find our point of equilibrium. Some issues take time to resolve, but they do resolve, and we move on to the next thing.

Third, despite the frequency and fervour of some of our debates, there is almost always present a core level of respect between those on opposite sides of an argument. Some members disagree with

the way in which others go about things, or with what has been said or done in the heat of a debate, but in almost all cases that core level of respect for one’s fellow member of counsel remains.

Fourth, we have both formal and informal mechanisms for deescalating disputes amongst our 2,200 practising members. Those mechanisms no doubt exist in most complex organisations. However, to my observation at least, our Bar seems to be particularly adroit at deploying just the right mechanism— and just the right people—to resolve internal tensions. That is no doubt because we are an association of professional problem solvers. Nonetheless, it is worth noting that we seem to be particularly good at maintaining our fundamental unity. Come what may, we hold together.

Fifth, the media and the public seem to be very interested in our

We remain one of the strongest Bars in Australia, and we remain the first choice for practitioners who have talent but limited means who want to come to the Bar and make a go of it.

internal goings on. I suppose that is to be expected given the important role we play in civil society. In light of this reality, to my mind at least, it is always best if we try to resolve our differences internally, out of the media spotlight. In fact, that is almost always how things are resolved. That is not to say that there is never a role for members to engage with the media, particularly on important matters. There is certainly a place for that. There is, however, much to be said for picking up the phone to air differences directly with fellow barristers when the need arises. That approach is much more likely to keep things within bounds and preserve and enhance relationships upon which our college is based.

Finally, when considering all of this, I think it is important to remember that the Victorian Bar is much bigger than any single one of us, or any small group of us. A review of our history reveals that we have weathered many controversies of a variety of different types for over 180 years. We are still together, we remain one of the strongest Bars in Australia, and we remain the first choice for practitioners who have talent but limited means who want to come to the Bar and make a go of it. That is all worth celebrating. And it is worth continuing to do the necessary work to resolve our differences in our idiosyncratic but ultimately very effective way.

Favourite fictional lawyer?

Lionel Hutz, for being a perfectly cromulent lawyer.

Historical case you would like to have argued?

Jarndyce v Jarndyce (or real-life equivalent Jennens v Jennens), for a lifetime of reliable work.

Best piece of advice you learnt in the readers’ course? Submissions should convince the reader through the use of nouns, not adjectives.

Reading with?

Andrew Meagher. Ultimate career goal as a barrister?

Uphold the proper administration of justice, finally stop renting (not necessarily in that order).

Favourite fictional lawyer?

Annalise Keating (How to Get Away with Murder). A fierce and multifaceted character who leaves a lasting impact.

Historical case you would like to have argued?

Al-Kateb v Godwin: no person seeking asylum should be indefinitely detained.

Best piece of advice you learnt in the readers’ course?

Where appropriate, get in and then out quick with your cross-examination.

Reading with?

Shivani Pillai.

Ultimate career goal as a barrister?

At this point, I don’t really have one. I am riding with the waves.

Favourite fictional lawyer?

Hannah Stern from The Split. What a woman. What a show.

Historical case you would like to have argued?

CBA v Amadio (1983). Interesting case particularly given where we are with banking regulation and unconscionable conduct 40 years later.

Best piece of advice you learnt in the readers’ course?

Justice Stynes’ three Ps: Preparation, Perseverance and Personality.

Reading with?

The wonderful

Naomi Hodgson. Ultimate career goal as a barrister?

Fulfilling work alongside great people.

Each edition, we reach out to the latest cohort of readers to get to know them better

Favourite fictional lawyer?

Lizzie Bennet re-cast as an aspiring barrister in Pride and Premeditation (a trashy and delicious read as long as you’re not too precious about Jane Austen).

Historical case you would like to have argued?

I wouldn’t attempt to argue any historical case just yet!

But I would love to have been able to attend some of the famous negligence cases to watch that law being made.

Best piece of advice you learnt in the readers’ course?

Jim Peters’ advice to “stay calm in the tempest of disaster and solve the problem”.

Reading with?

Patrick Over.

Ultimate career goal as a barrister?

To nerd out on the law and then spend school holidays with my family.

Favourite fictional lawyer?

Gomez Addams from The Addams Family. He doesn’t talk about his job.

Historical case you would like to have argued?

The prosecution of The Angry Penguins for the Ern Malley hoax.

Best piece of advice you learnt in the readers’ course?

Always write down your legal argument by hand. Reading with?

Leana Papaelia.

Ultimate career goal as a barrister?

Make the law less incomprehensible to those who need to understand it most.

Favourite fictional lawyer?

Elsbeth Tascione from The Good Wife—strategic, underrated, and funny.

Historical case you would like to have argued?

The Diesel Williams Court of Appeal case—to try and right a historical wrong.

Best piece of advice you learnt in the readers’ course?

Work-life balance is key— barrister code for “try and only work six days a week”.

Reading with?

Tom Smyth.

Ultimate career goal as a barrister?

Do interesting work with interesting people and get paid well for it.

Favourite fictional lawyer?

Betty Anne Waters from Conviction (even though it’s based on a true story…).

Historical case you would like to have argued?

Somerset v Stewart (1772) 98

ER 499: what a precedent to be involved in setting?!

Best piece of advice you learnt in the readers’ course?

That this is the best job we’ll ever have.

Reading with?

Gabi Crafti (I know, I’m very lucky!).

Ultimate career goal as a barrister?

To do what I love and make the world a bit brighter in the process.

Favourite fictional lawyer?

Lieutenant Daniel Kaffee because I love the movie!

[A Few Good Men.]

Historical case you would like to have argued?

Waltons Stores (Interstate)

Ltd v Maher because it was the first case that I read at university which created a sense of curiosity and love of case law.

Best piece of advice you learnt in the readers’ course?

The lows are never as low, and the highs are never as high.

Reading with?

Kane Loxley.

Ultimate career goal as a barrister?

Make it through the first year.

Favourite fictional lawyer?

Jackie Chiles [Seinfeld].

Historical case you would like to have argued?

Marbury v Madison for its unmatched constitutional significance and high stakes political drama.

Best piece of advice you learnt in the readers’ course?

Preparation, preparation, preparation.

Reading with?

Paul Liondas.

Ultimate career goal as a barrister?

Some combination of satisfaction and competence.

Blashki

Favourite fictional lawyer?

Dennis Denuto— it’s the vibe!

Historical case you would like to have argued?

I would have loved to work with my grandfather, Ron Castan, on the Mabo case.

Best piece of advice you learnt in the readers’ course?

Treat everyone with respect and kindness—it’s a small world.

Reading with?

Damien McAloon, a generous and inspiring mentor.

Ultimate career goal as a barrister?

To contribute to the great institution of the Victorian Bar throughout a long and fulfilling career.

Favourite fictional lawyer?

Gerri Kellman [Succession]. Historical case you would like to have argued?

Whatever dispute caused section 8(c) of the Summary Offences Act 1966 (Vic) to be enacted (criminalising the driving of a goat harnessed to a vehicle through a public place).

Best piece of advice you learnt in the readers’ course? Being a witness is far more terrifying than being a barrister (even in a moot).

Reading with?

Andrew de Wijn. Ultimate career goal as a barrister?

To have many leatherbound books and for my chambers to smell of rich mahogany.

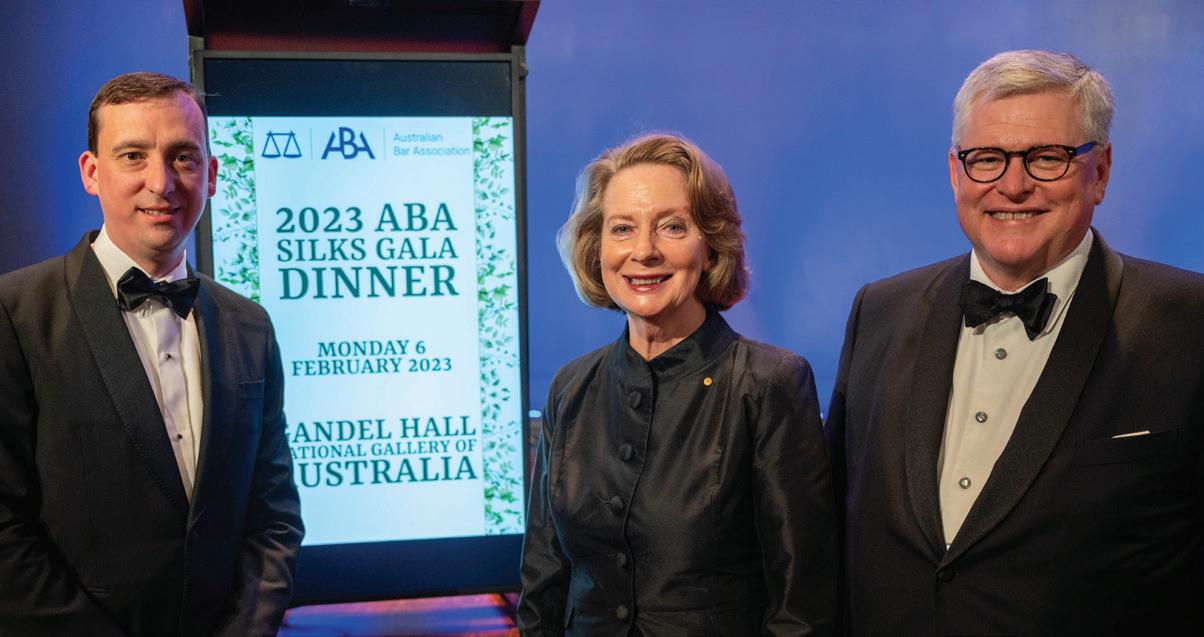

Our newest silks attended the Silks Bows Ceremony at the High Court in Canberra on 6 February 2023. Mark Costello SC gave the keynote address on behalf of the all-new silks and the Hon Chief Justice Kiefel AC addressed the new silks in response.

DAVID KELSEY-SUGG AND ALEXANDER CAMPBELL

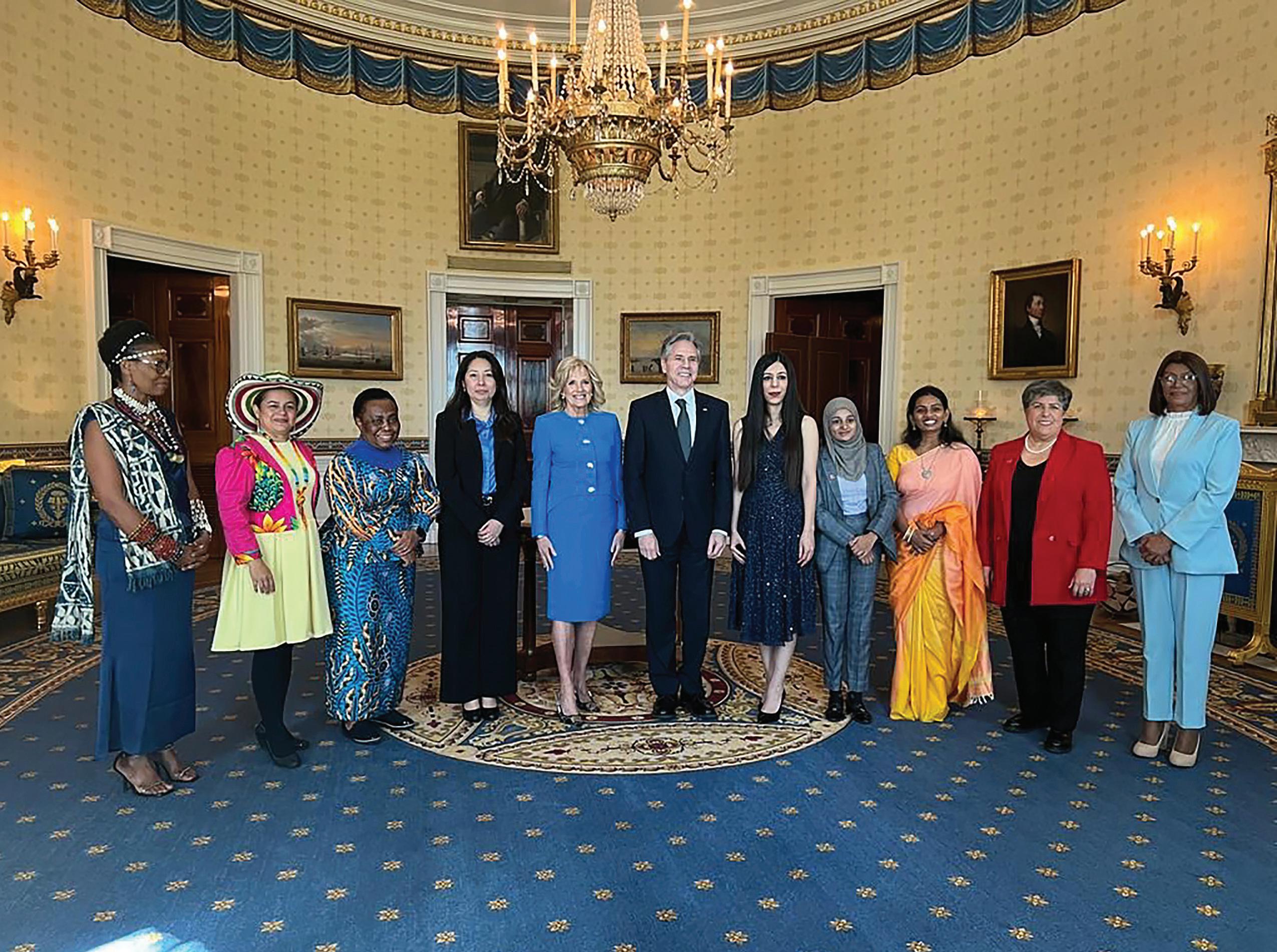

The Bar’s biennial Pro Bono Awards were announced on 21 March 2023 at a very well attended event in the Peter O’Callaghan QC Gallery. Guests and award nominees were met with a warm welcome by the chair of the pro bono committee, Matthew Harvey KC, who singled out for praise the efforts of committee members Chris Lum and Laura Hilly in organising the event. The awards recognise the contribution of members of the Victorian Bar who provide pro bono assistance through the Bar’s Pro Bono Scheme (administered by Justice Connect), the Court Schemes, community involvement and individual commitment.

Justice Kristen Walker of the Court of Appeal gave a well-received speech celebrating the pro bono work performed by members of our Bar. Her Honour highlighted the rewards of pro bono work: the opportunity to help those in need; the chance to broaden one’s skills and knowledge; possible enhancement of a barrister’s reputation and visibility within

the legal community; personal fulfilment and satisfaction; and sometimes a “pleasant and unexpected” income bump. Her Honour also paused to reflect on the challenges that can attend pro bono work, observing:

… many of you will undertake pro bono work for a group of which you are a member: indigenous people, people with disabilities, or the LGBTQI community, for example.

The emotional weight of taking on such work can be much greater than in the context of other work, and the psychological toll can be significant. It is important in such contexts to pay attention to your own wellbeing.

And this is also a reason why it is important that it is not always, or only, the members of such groups who undertake such work. The generosity of allies is significant, and I want to acknowledge everyone here who has undertaken pro bono work in this manner. Thank you.

Among the award presenters were distinguished guests including Justices Gordon and Steward of the High Court, Justice (now Chief Justice) Mortimer of the Federal Court, Chief Justice Alstergren of the Federal Circuit and Family Court, Justice Croucher of the Supreme Court, President of the Victorian Bar, Sam Hay KC, Ron Merkel KC and Uncle Jim Berg. Uncle Jim Berg, an Elder of the Gunditjmara people of South-Western Victoria, presented the eponymous award “for outstanding pro bono advice or advocacy that enhances access to justice for First Nations clients either nationally or in Victoria” to Tim Farhall. Tim has acted in numerous pro bono matters for First Nations clients, including discrimination matters and matters arising out of deaths in custody. He has also advised community legal centres and non-government organisations on issues affecting First Nations people. The depth and breadth of Tim’s pro bono work are impressive.

Ron Merkel KC presented the award named in his honour to Juliet Forsyth SC, for her outstanding work in a lengthy and complex rehearing in the Queensland Land Court, on behalf of a landowner group who objected to the expansion of a coal mine in the Darling Downs. In presenting the award, Ron reminded those in attendance that his master was none other than Neil Forsyth QC, Juliet’s father. With a smile, Ron hinted that some things perhaps were meant to be.

The 2023 Victorian Bar Pro Bono Trophy was awarded to Julian McMahon SC in recognition of his longstanding commitment to pro bono service. Julian’s pro bono record would be known to many. He has acted recently for Australians facing the death penalty overseas and for Fitzroy Legal Service at the coronial inquest into the death in custody of Veronica Nelson, a Gunditjmara, Dja Dja Wurrung, Wiradjuri and Yorta Yorta woman.

Julian’s efforts also ensured rigorous and thorough representation of the Parumpurru Committee of the Yuendumu Community at the coronial inquest into the fatal

shooting of Kumanjayi Walker. It was fitting that the trophy was presented to Julian by 2021 winner Matthew Albert, himself a winner of this year’s Pro Bono Team Excellence Award.

True to form, Julian first thanked and congratulated everybody else. Reflecting on the volume of pro bono work undertaken at the Victorian Bar, he observed, “it makes you feel pleased, if not delighted, to be a member of a Bar that is quietly doing [so much pro bono work] … It’s an honour to be named among so many people who have done such extraordinary things”.

There is a long history of members of the Victorian Bar acting pro bono. All members of our Bar who undertake pro bono work, including those who won or were nominated for an award in 2023, deserve to be congratulated. It is not only litigants who appreciate the assistance of pro bono counsel. To return to the words of Justice Walker, legal representation enhances the quality of the arguments that are put, and this is of great assistance to courts and other decision-makers.

The winners of the 2023 Pro Bono Awards were:

» The Victorian Bar Pro Bono Trophy –Julian McMahon AC SC

» The Daniel Pollak Readers Award –Katharine Brown

» The Ron Castan AM QC Award –Tim Jeffrie

» The Susan Crennan AC KC Award –Alison Umbers

» The Ron Merkel KC Award –Juliet Forsyth SC

» The Public Interest / Justice Innovation Award – Claire Harris KC, Christopher Tran, Colette Mintz and Nicholas Baum

» The Debbie Mortimer SC Award –Gemma Cafarella

» The Uncle Jim Berg Award –Tim Farhall

» The Equality Award – Min Guo

» The Pro Bono Team Excellence Award –Peter Willis SC, Matthew Albert, Angel Aleksov and Evelyn Tadros

Descriptions of the work done by the winners, and a full list of those nominated for the 2023 awards, are available on the Victorian Bar’s website.

CAROLINE PATERSON

On Friday, 17 February 2023, around 220 family law barristers, solicitors, judges and judges’ associates attended the Family Law Bar Association’s 6th annual Flagstaff Bell Barefoot Bowls event. After a day of extreme heat, the Calippos and watermelon slices offered for dessert after the spit roast dinner were an absolute hit. The “Bar and Bench” team had a convincing win to reclaim the Bell from the solicitors. As the sky turned purple and the sun went down, Sam

Marash, partner at Kenna Teasdale Lawyers, presented the Bell to the Bar and Bench captain, Geoff Ambrose.

This event has become the customary way we open our social program each year. It is particularly popular with judges’ associates, who attend as guests of the FLBA—our way to thank them for the hard work they do to support their judges and also the profession, to keep the court lists running smoothly. Next year’s Flagstaff Bell will be held on Friday, 16 February 2024.

RABEA KHAN

On 29 March 2023, the Victorian Bar held its annual Iftar Dinner, co-hosted with the Australian Intercultural Society (AIS).

The dinner is one of the annual events organised by the Equality and Diversity Committee of the Victorian Bar. The holy month of Ramadan is a time when Muslims fast, abstaining from food and water, from sunrise to sunset. An “iftar” is the meal that breaks the fast at the time of the sunset prayer. It was the fourth time the Victorian Bar had held this event in Ramadan with the AIS and it was also the fourth time the event had sold out.

The distinguished guests at the dinner included their Honours Judges Gaynor, Robertson and Tsikaris, President, Sam Hay KC, and the Executive Director of the Australian Intercultural Society, Ahmet Keskin.

The night included a thought-provoking conversation between barrister Yusur Al-Azzawi and Mohammad Chowdhury. Mohammad Chowdhury is the author of the book, Border Crossings: My Journey as a Western Muslim. In line with the themes of the book, Mohammad shared his experience as a Western Muslim in a post-9/11 world and his journey in reconciling the British, Asian, and Muslim sides of his identity.

As is the tradition of an iftar, the conversation was followed by the adhaan (call to prayer) and the breaking of the fast. The dinner was well attended with a diverse array of guests, including members of the judiciary, Victorian Bar members of all seniorities, lawyers, law students and members of the Muslim community. The annual interest in this event highlights both the value of the legal profession reflecting the community it serves and the enthusiasm from our Bar to celebrate its diversity.

Wednesday 8 March 2023 saw the return of the Commercial Bar Association’s annual cocktail party.

Graciously co-hosted by the Chief Justices of the Federal Court of Australia and the Supreme Court of Victoria in the capacious foyer of the Commonwealth Law Courts building, the function coincided with Chief Justice Allsop’s last Melbourne sitting before his retirement, and we were privileged to have him spend the early part of his evening with us.

Over 200 counsel and members of the judiciary, in-house counsel and commercial solicitors as our invited guests celebrated the opportunity to gather once again post-pandemic for a fabulous evening of cocktails and canapés.

The Chief Justices welcomed all attendees and reflected on our practices returning to a new normal following the lifting of lockdowns and returning to court in-person where

possible. Chief Justice Allsop commended CommBar as an institution worthy of emulation in other states. Chief Justice Ferguson celebrated the fact that the profession and the judiciary were once again able to congregate and empathised with the challenges confronted by each of us in dealing with the last few years on both an individual and professional level.

CommBar President Stewart Maiden KC welcomed all attendees and took the opportunity to launch an exciting new initiative for CommBar: an underwritten internship for law students. Work experience is a crucial aspect in preparing a person for legal practice and in introducing them to the job market, and the new program is designed to assist those students whose personal circumstances might prevent them from taking unpaid work.

A great night was had by all, with the consensus being that it is good to be back.

1. Nick Hopkins KC and The Hon Justice O’Bryan 2. The Hon Justice O’Bryan, Premala Thiagarajan, James Gray 3. Sam Hay KC, The Hon Justice Connock, Ian Percy 4. John Tesarsch, Judicial Registrar Bennett, John Heard, Fiona Cameron 5. Rowan Minson, James Waters 6. Chief Justice Ferguson 7. Claire Harris KC, Chief Justice Allsop 8. Mitchell Grady, Sam Rosewarne KC, Hamish Redd 9. Dr Drossos Stamboulakis, Kieran Hickie 10. The Hon Justice Lyons 11. Nik Dragojlovic Raini Zambelli, Andrew Meagher 12. Dion Fahey, Clare Exell, Jillian William, Alexandra Folie 13. Elodie Nadon, Julia Nikolic 14. Chief Justice Allsop 15. The Hon Justice O’Callaghan, Lisetta Stevens 16. Timothy Goodwin, Mark Hosking, Dr Laura Hilly 17. Alison Martyn, Alex Solomon-Bridge, Dion Fahey 18. Paul Hayes KC, Jesse Rudd, Zoe Anderson, Judicial Registrar Bennett 19. Stewart Maiden KC 20. Ian Horak SC, Lara O’Rorke, Amanda Storey

PETER WILLIS

“Close your eyes and imagine a tram journey up Glenferrie Road 50 years ago, full of jostling school students …”. With these words, Peter Jopling KC transported a large gathering of friends and colleagues to the origin stories of the Hon Sue Kenny and the Hon Kate McMillan, who attended schools a few metres apart, became friends at law school, signed the Bar Roll together on the evening of 12 March 1981, and had parallel distinguished careers as members of the Bar and judges.

The occasion was the official unveiling on International Women’s Day, 8 March 2023, of striking portraits of each in the Peter O’Callaghan QC Gallery.

Their Honours’ careers are well rehearsed in the pages of Victorian Bar News and the Bar history. Their remarks in reply to Jopling’s imaginative and fulsome launch are

worth recording. Kate McMillan first recorded her delight at the “wonderful portrait” by Queensland based artist, Jenny Watson, who was present for the launch:

Her commission began at the start of the lockdown. She had to make do with photographs, chats over the phone and one face-to-face meeting.

I felt an immediate connection with her, and I hope she did with me. Her portrait of me is striking, yet subtle— not that many would ever describe me as subtle. Jenny has captured the younger and older me, heading towards what I would describe as my forthcoming blue sky thinking period.

Kate McMillan then recalled her role as Chair of the Bar’s Arts and Collections Committee:

I inherited a lacklustre art committee—there were a few very

good portraits in the collection, with the rest being more average. A stocktake of inventory revealed a collection of about 30 portraits; two were missing—one was subsequently found behind a door in the Bar office, and the second was run to ground somewhere at Melbourne University.

One of my lasting achievements before finishing as Bar Council Chairman was to appoint Peter Jopling as the head of the Arts and Collections Committee. He remained in charge until his retirement last year, that is, from 2006 to 2022. Without Peter’s contribution to the formation and development of the Peter O’Callaghan Gallery, there would be no gallery at all, 60 plus portraits would not exist, and all who walk

through Owen Dixon Chambers would not enjoy the privilege of seeing such a remarkable display, as well as the snapshot of the history and traditions of the Victorian Bar.

Sue Kenny first thanked her portraitist, who painted a work of detail, depth and honesty:

Marie Mansfield’s work speaks for itself. Her kindness, patience, empathy made the sitting a lovely, though humbling, experience.

Justice Kenny, too, then reflected on the gallery and what it displays. She recalled that on signing the Roll, she and Kate McMillan were among just 20 women of 700 members of the Bar.

She noted how the Bar has evolved but is still not as diverse as contemporary Australian society:

Why is this so? The principle of ‘merit’ is often said to be a cornerstone of the Bar … One problem may be the ideal of merit itself. The ideal can be dangerous: it is not always referable to relevant and objective criteria. If the criteria are wrong, the ideal can effect unjust discrimination, which is damaging for the Bar and the administration of justice.

This gallery can, and I think is, playing a crucial role in addressing this problem. Its portraits show that outstanding barristers are diverse, save that they strive to be expert in law, ethical, and actors in the common good.

There are two things I love about the gallery. First, it shows us that not all barristers look the same. Nor do they share the same heritage, life experience or worldview. Second,

the gallery gives us a powerful visual history of how we are evolving. It shows us that diversity makes us stronger.

We are indebted to those with the imagination and dedication to institute and maintain the gallery, and to the Bar for supporting them.

And if Kate and I are rather astonished by what has occurred, we are also very touched.

GEORGINA COSTELLO

Under the joint banners of the Law Council of Australia and the Victorian Bar, solicitors, barristers, tribunal members and judges arrived at the Essoign Club in February 2023 for the opening drinks function of the inaugural Commonwealth Law Conference. The theme of the conference was coherence and connection in federal law, and focused on federal law issues at a time of enormous change and challenge. Attendees flew in from around Australia to make connections with new colleagues and think about common issues across diverse areas of federal law.

With pressing issues in federal law ripe for discussion, conference delegates heard speakers talk about the impending abolition and planned rebirth of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal, the start of a federal anti-corruption commission, the coming referendum on the Voice, potential solutions to the ever-growing backlog of migration cases in the federal courts, and emerging issues in tax, industrial and class action cases.

Bar President Sam Hay KC kicked off the conference opening drinks function with warm remarks to welcome the assembled conference delegates. The balance of the conference continued in

style at the RACV Club in Bourke Street and culminated in a pleasant Friday lunch for all who attended.

A highlight of the conference was the presentation of the inaugural Young Federal Litigator of the Year award to solicitor Rob Andersen by Chief Justice Alstergren of the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia. Mr Andersen is a senior associate in the dispute resolution practice at Ashurst in Canberra. Competition was fierce for the award with nominations received from around Australia. Ultimately, the accomplished Mr Andersen prevailed. His career so far includes successfully defending the Commonwealth against a claim by staffers in Senator Lambie’s office who alleged their employment was terminated in breach of the general protections provisions of the Fair Work Act and work for the National Disability Insurance Agency in appeals to the Federal Court.

Speakers at the conference included the Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus KC, Justices Perry and Murphy from the Federal Court, Justice Nichols from the Supreme Court, Deputy Presidents of the AAT Bernard McCabe and Peter Britten-Jones, plus an abundance of

eminent lawyers including Craig Lenehan SC, the Hon Chris Jessup KC, Ingmar Taylor SC, Kate Eastman SC, Daniel McInerney KC, Valerie Pereira, Andrew Cope, John Emmerig and Professor Mary Crock. The conference was both timely and on trend as conference attendees digested fascinating presentations on class actions, industrial law, appeals, tax cases, migration law and both merits and judicial review between delicious food, coffee and drinks.

Justice Perry’s keynote address focused on the role of artificial intelligence, with her Honour cautioning against the use of chatbots in legal work in a witty and erudite presentation. During the class actions session, Ben Slade and John Emmerig presented current research on the quantum of recoveries of damages and funding costs in class actions. Peter Woulfe, Chair of the LCA’s Federal Dispute Resolution Section, Dr James Popple, Law Council CEO, and LCA president Luke Murphy also gave excellent presentations to the assembled audience.

Thanks go to the Law Council’s Federal Litigation and Dispute Resolution Section and the Victorian Bar for organising and hosting the event which was a sell-out and is hoped to be the first rather than the last time the LCA and the Victorian Bar arrange a conference focused on federal law. With a new Chief Justice of the Federal Court appointed soon after the conference, the stage is set for the next conference to continue the conversations and collegiality in Victoria and around Australia in our federal profession.

With COVID lockdowns far behind us, the Criminal Bar Association (CBA) headed down to the RACV Club, Healesville on 3 March 2023 for its biennial conference. Over 100 barristers, ranging from readers to well-established silks, attended for a weekend of discussion, learning, and golf.

The conference commenced on Friday evening, with a gin masterclass at Four Pillars Distillery. While the CBA hasn’t been able to formally award CPD points for learning the difference between ‘Old Navy’ and Shiraz gin, the night certainly set the tone for a weekend of catching up with old and new colleagues.

The Saturday CPD sessions commenced with learnings and encouragement from the heads of criminal jurisdictions across the Magistrates’, County and Supreme Courts. While the courts are still facing significant backlogs, much is being done behind the scenes to reduce unnecessary delays in the criminal justice system. It’s not just the courts working on implementing new strategies at reducing delays—attendees were also reminded of the importance of respectful and productive resolution methods, both in and out of court. The CBA is in ongoing discussions with the courts, and welcomes feedback from members on any concerns which ought be raised with the relevant jurisdictions.

The relationship between psychology and law has taken on a significant role in sentencing and, increasingly, postsentence detention regimes. We were lucky to ‘test the friendship’ between psychology and law with Dr Joel Godfredson. Courts, and counsel, are reliant on the opinions of psychologists in many aspects of their work, and so we are grateful to Dr Godfredson for this frank and informative session.

While it may have been a while since many attendees had entered a classroom, Justice Beale took us ‘back to basics’ with a hearsay masterclass. Detailed written submissions have taken on a more dominant role in advocacy, and a thorough working knowledge of how best to use the Evidence Act to your advantage is essential in setting the tone for your submissions. The importance of a detailed analysis of legislative regimes was also highlighted on Sunday with Shaun Ginsbourg taking attendees through the extended liability provisions within the Criminal Code

Despite consistent chatter threatening to remove committal proceedings from Victoria, they were certainly not forgotten at the conference. Attendees shared their experiences, with discussion around the room certainly highlighting a range of approaches to committals. It was a tough gig for presenters to be the last in the Saturday afternoon slot, as attendees looked forward to letting their

hair down to the tunes of our very own Jim Shaw’s band, Bridgetown!

The work of the Judicial Commission of Victoria (JCV) has been highlighted in the media recently, and the CBA was lucky to have Amber Harris, formerly of the JCV, and more recently back at the Victorian Bar, to remind attendees of the important role that the JCV plays, and the avenues available to members.

The CBA continues to be acutely aware of the impact that a busy criminal practice can have on its members.

Sunday morning gave attendees a chance to reflect and develop positive strategies for addressing vicarious trauma.

Peter Chadwick KC gave the concluding session for the weekend, presenting a paper on the much debated Human Source Management Bill. Peter’s forceful presentation reminded all attendees of the importance of a barrister’s independence, the strict rules of ethics, and particularly the unique position criminal barristers are often placed in owing to the nature of their practice:

The independence of the Bar is such an integral aspect of a barrister’s professional obligations and the rule of law itself, that a barrister should owe no allegiance to anyone or anything other than to the court and their client in accordance with the Bar rules.

Acting as a registered human source to a law enforcement agency carries with it so serious a risk to a barrister’s independence that counsel is likely to be confronted with major ethical difficulties should he or she become an informant even against individuals who are not clients.

With those sage words ringing in our ears, we concluded a most successful and enjoyable weekend conference. Thanks to all of those who organised, and all who attended.

ANNA SVENSON

On Friday 24 February 2023 Svenson Barristers hosted a very special party at the Arts Centre Melbourne to mark 60 years of List S at the Victorian Bar.

The event brought together current members, alumni and judicial members, as well as current and former staff and solicitor and industry guests. We were delighted to welcome former head clerks, Ken Spurr (now aged 91!) as well as Ross Gordon to the event.

Instead of lengthy speeches, our audience enjoyed a polished video montage of memories and messages from members of our List community, past and present.

The List was established in 1963 by Ken Spurr, when he was in his early 30s.

We have always regarded ourselves as “the friendly List”, and over our rich 60-year history we have valued community, collegiality, success and friendship.

Interwoven into the fabric of List S are the clerking business and staff who support the barristers. Many staff have worked

harmoniously with the List for decades showing incredible dedication, fierce protection and great love and admiration for their barristers. The clerks and team become the career partner to the barristers—cheering them on every step of the way through their very long careers, as they forge their practice at the Bar, from reader to retirement.

Solicitors through the years will have known List S under its various solicitor-facing clerking identities: first as Spurr’s List beginning in 1963, then as Gordon & Jackson Barristers Clerks from 1996 to 2016, and now as Svenson Barristers. The principal clerks become the markers in time, depicting the various eras of the List over the decades.

As the founding clerk of List S, it’s Ken Spurr whose name gives us our identity (“S for Spurr”). Our current Svenson Barrister logo embraces the List S identity, showcasing it in the emblem adjoining the Svenson Barristers text, paying homage to Ken Spurr’s original seal.

Here’s to many more wonderful years for List S!

CARLY MARCS

As a fairly innumerate barrister, preoccupied with matters of criminal law, fundraising has never been in my skillset. But my seven-year-old son, Louis, is fortunate to attend a very special school called Giant Steps, which educates children on the autism spectrum. Being a member of our community school necessarily involves fundraising, because the life-changing trans-disciplinary and individualised program that Giant Steps offers each student is labour and resource intensive. For the first time in the history of Giant Steps in Melbourne, we managed to get a wonderful fundraising event off the ground, literally—a stair climb involving 96 floors and 1,700 steps. Whilst registering for the event and setting up my donation page, I received an email from an address I have come to know and cherish since 2012 when I spent time at the County Court of Victoria as strategic adviser to the much-loved former Chief Judge, Michael Rozenes KC.

The email’s author was Judge Gucciardo of the County Court. Over the past 13 years, Judge Gucciardo has regularly shared his musings on life, love, literature, philosophy, art and all the things that make life rich and meaningful, with his dedicated readership of aptly titled “Ciceronians”. In this forum, Judge Gucciardo shares stories and content from authors and thinkers he admires. The messages are educative (they always feature a bit of Latin that I have to admit putting through google translate), thought provoking and often uplifting. Significantly, in the 13 years of Cicero, Judge Gucciardo has preserved his emails as a special space for pondering the bigger questions. He has never solicited or used his vast database for any other purpose.

Without thinking, I hit reply and shared my newly established fundraising page with Judge Gucciardo:

Long time. I hope this finds you well. Please don’t hesitate to say no if this request is a little too much but I was thinking about your regular email musings (which I thoroughly enjoy) and how broad your reach is. I was wondering how you might feel about sharing my fundraising efforts below?

Judge Gucciardo kindly shared my request with his database, which includes sitting and retired judicial officers. Matt Parnell and Sharon Noorman from Parnell’s Barristers also shared my request with the entire list, and I distributed the link to my own networks at the Bar.

What happened next is a testament to the generosity and collegiality of the Bench and our Bar. Donations rolled in from far and wide. At the time of writing, I have managed to raise over $34,000. I have been humbled and deeply moved by the extraordinary generosity of barristers and judicial officers. I could never have expected such generous donations and messages of support and encouragement.

Life as a special needs parent can be challenging, but sometimes, also uplifting. For every angry stranger glaring at me in the supermarket because my son has touched their pumpkin whilst stimming1, there are barristers and judges supporting him and me and thereby erasing any shame we might sometimes experience.

When we come together as a legal community, we can do amazing things. Words like gratitude and appreciation can’t convey how this has made me and my family feel.

1 A self-stimulatory behaviour.

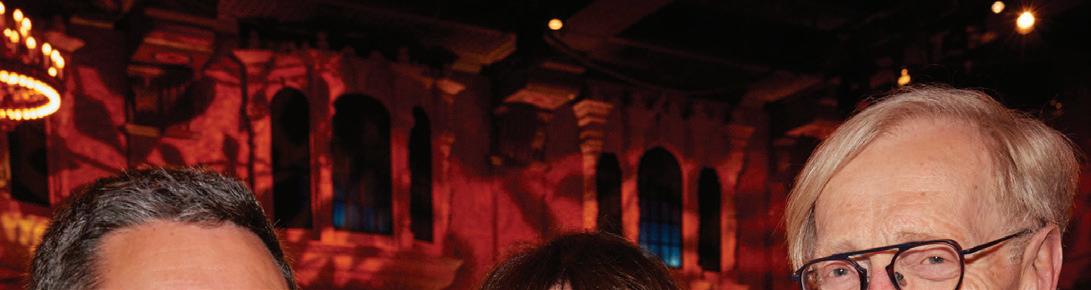

PLAZA BALLROOM, MAY 26 2023

This year’s Bar Dinner was held at the Plaza Ballroom, on a chilly night in late May. Undeterred by strong winds, members of Bar and Bench donned their best for a night of canapes and conviviality.

This year’s event featured pared-back formalities, overseen by MC Elle Nikou Madalin. A welcome by Bar President Sam Hay KC was followed by a thoughtful and amusing speech by the Solicitor-General of Australia— the Bar’s own Dr Stephen Donaghue KC—who was himself welcomed and thanked by Vice-Presidents Georgina Schoff KC and Elizabeth Bennett SC. Ably assisted by his “junior”, ChatGPT, Dr Donaghue KC deftly stitched together musings on the dilemma presented by an invitation to speak at the Bar Dinner and sincere comment on the upcoming referendum, also offering words of support and wisdom to the newest members of our ranks. Threats to embark on an exploration of vehicle usage charges and section 90 of the Constitution came to nothing.

Amusing though the speeches and toasts were, guests also enjoyed the opportunity for extended mingling and catch-ups that the new program offered. And then there was the dancefloor, fuelled by the music of Emmerson Dodge, feat. Georgia Caine and Peter Wallis KC on vocals, Chris Brodrick (guitar/vocals), Andrew McRobert (guitar), Ed Heerey KC (bass), Justin Wheelahan (keyboard), the Hon Justice McNab (saxophone) and Bar News’ very own Peter Barrett on drums. But enough of the details, we know it’s really all about the photos…

1. Adam Awty, Amanda Utt, the Hon Ken Hayne AC KC, Chief Magistrate Justice Hannan 2. Kylie Evans, Jenny Firkin KC, Meg O’Sullivan KC 3. Natalie Campbell, Helen Tiplady 4. Chief Judge Kidd, the Hon Justice Steward, Anthony Howard AM KC 5. Gisela Nip, Michael Thomas, Nicholas Petrie, Yusur Al Azawi 6. Elizabeth Bennett SC, David Shavin KC, Georgina Schoff KC 7. The Hon Jack Rush AO RFD KC, Antony Berger, Dr Michael Rush KC 8. Johannes Angenent, Raph Ajzensztat, Maria Pilipasidis SC, Brendan Johnson, Ian McDonald KC 9. Elle Nikou Madalin 10. The Hon Associate Justice Steffensen, Sam Hay KC, Raini Zambelli

1. Nawaar Hassan, Richard Dalton KC, Shane Lethlean 2. John Karkar KC and The Hon. Gregory Howard Garde AO RFD KC 3 Georgina Schoff KC, Dr Stephen Donaghue KC 4. The Hon Mark Dreyfus KC MP, Sam Hay KC, the Hon Linda Dessau AC CVO 5. Kylie Evans, Lisa Hannon KC, Damien O’Brien KC, Paul Hayes KC 6. Claire Harris KC, Maree Norton 7. Laurence Fudim, Rhiannon Saint, Olivia Callahan, Pinar Tat, Cheryl Richardson, Jade Ryan 8. Amanda Utt, Georgina Costello KC, Georgina Schoff KC, Catherine Boston 9. Rachel Amamoo, Maya Narayan, Edwina Smith, Monika Pekevska, Katherine Brown, the Hon Chief Justice Ferguson 10. Felicity Fox, Hamish McAvaney, Edward Moore 11 David Heaton, Dr Sue McNicol AM KC, the Hon Ken Hayne AC KC

1. James Barber SC, Charles Shaw KC, Joseph Carney, the Hon Justice McNab 2. Jessie Taylor, Rishi Nathwani, Tim Tobin SC, Anastasia Smietanka 3. Fiona McLeod AO SC, Dominic Toomey SC, Gabrielle Bashir SC 4. Susanna Locke, Monika Pekevska, Coroner Paul Lawrie 5. Annabelle Ballard, Shakti Nambiar, Bernice Chen, Tara Hooper, Chris Kaias 6. Premela Thiagarajan, Gabi Crafti, Marita Foley SC 7. Oliver ScoullarGreig, Michelle Button, Lachlan Molesworth, Andrea Skinner 8. Georgia Caine 9. Chris Brodrick, Ed Heerey KC, Peter Wallis KC, Georgia Caine 10. Karina Popova, Merys Williams, Richard Stanley, Kathy Karadimas, Katharine Gladman, Abhi Mukherjee, David Seeman, Raph Ajzensztat, Christine Boyle, Anastasia Smietanka

A Proposed Law: to alter the Constitution to recognise the First Peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice. Do you approve this proposed alteration?

Chapter IX Recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples

129 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice

In recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First Peoples of Australia:

1. There shall be a body, to be called the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice;

2. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice may make representations to the Parliament and the Executive Government of the Commonwealth on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples;

3. The Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws with respect to matters relating to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice, including its composition, functions, powers and procedures.

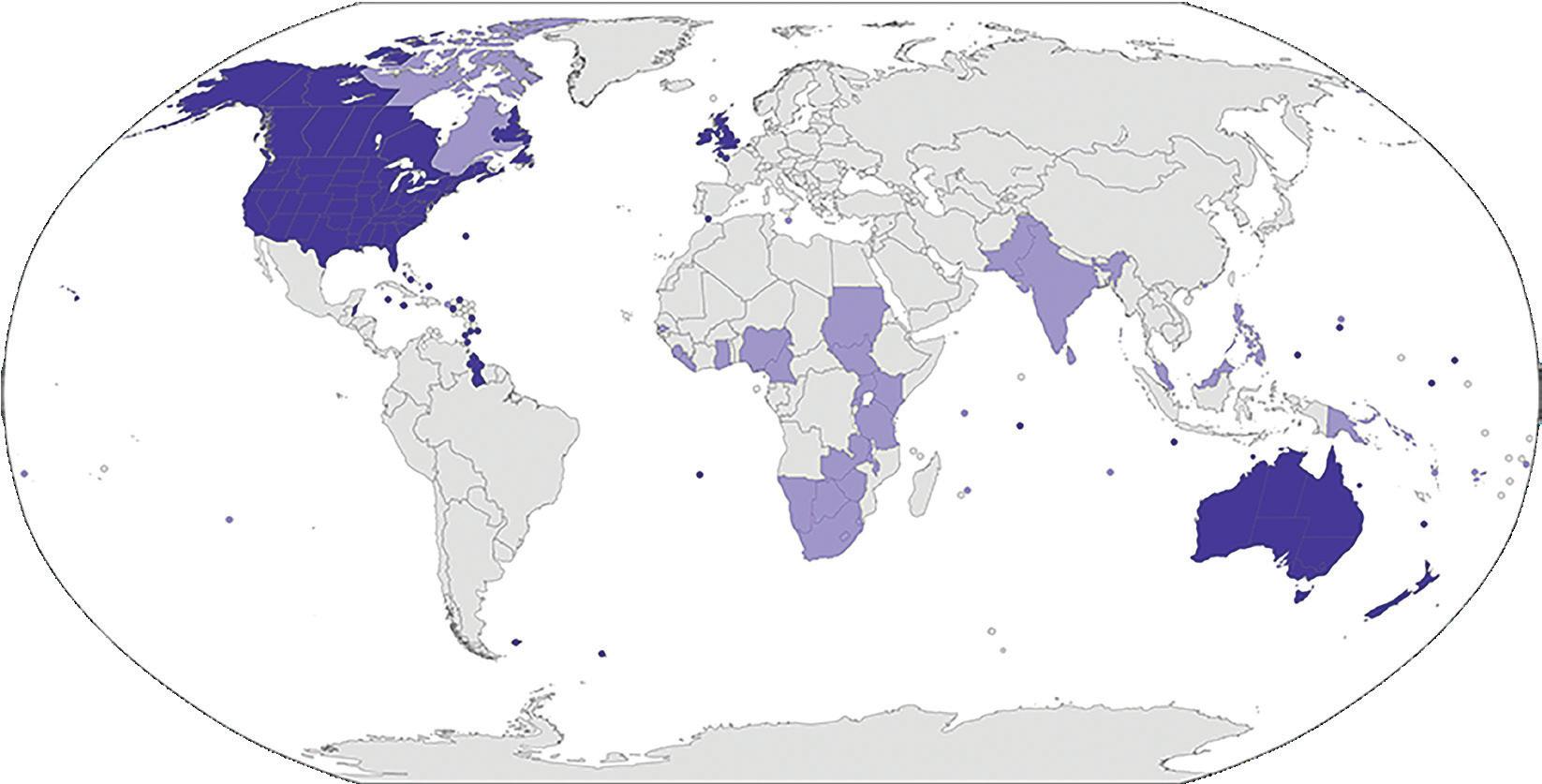

Australia is on the cusp of potentially amending its Constitution for the first time in 50 years to enshrine an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice. We understand that other contributions to this edition of the Bar News are looking in detail at the substance of the proposed amendment. In our contribution, we want to focus on the very idea of constitutional change—what it means for the people of a nation to collectively decide to change their founding document. In doing so we will focus on two ideas—the Constitution as ‘compromise’ and the Constitution as ‘blueprint for the good life’. We hope that our contribution will go some way to responding to the diametrically opposed concerns that the proposed amendment either does too much or too little. Before we do so, however, it is helpful to remember how we got here.

With public debate raging ahead of the upcoming referendum, and in all of the noise and commentary feeding into the daily news cycle, it is easy to forget that this proposal has been in the making for more than one year, or one decade. It is the product of over a century of advocacy by First Nations peoples.

While much of this advocacy is likely undocumented, we do know that as early as 1925 the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association was calling for direct Aboriginal representation in Parliament and the control of Aboriginal affairs under a Board of Management comprised of Aboriginal people. We also know of William Cooper’s petition to King George V in the early 1930s calling for Aboriginal people to have representation in Parliament. And we know of the Aboriginal Progressive Association in 1938 again advocating for an Advisory Board to the federal Department of Aboriginal Affairs, which Board was to be made up of at least half Aboriginal members. Then of course we have the 1967 referendum and the well documented push for the current constitutional change from the early 2010s, through the Uluru statement in 2017 to now.

It is perhaps inevitable that, through this century-long push for constitutional change, there have been compromises, by First Nations peoples and by others. We were reminded that the current proposal is a compromise by Senator Patrick Dodson at a lecture given to the Bar last year. He said, “It’s a very, very generous offer. Some of our people think

this is too little.” The Voice proposal is not everything for everyone. The long process by which the proposal has been conceived, rejected, refined and ultimately put to the people has been the subject of repeated compromises. Those who wanted a non-discrimination clause enacted in the Constitution have had to accept a more modest proposal. Those who wanted only a change to the preamble have had to accept a more ambitious proposal. Not everyone will agree. But that is the point. All constitution-making is compromise. One of the architects of the Australian Constitution wrote of those drafting it: “they were not only guided by a clear practical sense, but were animated by a spirit of reasonable compromise”.1 However the fact that our Constitution is the product of compromise is not its weakness but its strength—and that is true of the currently proposed amendment. It is by the accommodation of different views that we can come together as a nation.

Most importantly, even when it is the product of compromise, constitutionmaking and constitutional change draws the blueprint for the national trajectory. In the words of Martha Minow, former dean of Harvard Law School, a constitution should be “the blueprint for the good life”.2 The presently proposed amendment is no exception. As the Commonwealth Solicitor-General opined in a recently released advice, the “proposed s 129 is not just compatible with the system of

representative and responsible government prescribed by the Constitution, but an enhancement of that system”.3 It is an improvement to our blueprint for the good life. Albeit symbolic in some respects, the amendment also carries with it the hopes of all those that support it that it will tangibly improve the lives of First Peoples—and by doing so improve the whole of Australia. In that sense, the amendment confirms our understanding of our founding document as a reflection of our hopes and beliefs in what our country is and should be and how we, as a country, can live the ‘good life’ that Minow referred to.

1 James Bryce, Studies in History and Jurisprudence, vol 1 (Clarendon Press, 1901) 482.

2 Minow, Martha, Speech to 14th Amendment Class, Harvard Law School (2011).

3 Solicitor-General Advice, SG o. 10 of 2023, [21].

1977 Simultaneous House and Senate elections 1984 Interchange of Commonwealth and State powers

1984 Senate terms

1988 Civil rights and freedoms

Simultaneous House and Senate elections

Retirement age of Federal Judges*

Territory vote in referenda*

Senate casual vacancies*

1988 Local government 1988 Fair elections

1988 Parliamentary terms 1999 Preamble to the Constitution

1999 Establishment of a Republic

Denotes referenda

KEN HAYNE

Later this year we will vote on whether to approve a law “to alter the Constitution to recognise the First Peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice”. Approval requires a double majority—a majority of the electors in a majority of States, and a majority of all the electors voting. The text of the proposed alteration is short and simple. It would form a new chapter in the Constitution (Chapter IX, entitled “Recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island Peoples”) and would comprise a new section—section 129.

The words of section 129, like the Uluru Statement from the Heart, are the product of long, detailed and careful thought and discussion.

Are there reasons to fear the proposal?

My answer is an unequivocal “No”.

I put the question as I do—are there reasons to fear the proposal—because so much of what has been said against it has been an appeal to fear.

The proposed amendment responds to the Uluru Statement from the Heart. All of us should read the Statement. It was the product of long and detailed consultation with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Its opening paragraphs put the proposed amendment in its proper context. They read:

Our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander tribes were the first sovereign Nations of the Australian continent and its adjacent islands and possessed it under our own laws and customs. This our ancestors did, according to the reckoning of our culture, from the Creation, according to the common law from ‘time immemorial’, and according to science more than 60,000 years ago.

This sovereignty is a spiritual notion: the ancestral tie between the land, or ‘mother nature’, and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who were born therefrom, remain attached thereto, and must one day return thither to be united

with our ancestors. This link is the basis of the ownership of the soil, or better, of sovereignty. It has never been ceded or extinguished and co-exists with the sovereignty of the Crown.

How could it be otherwise? That peoples possessed a land for sixty millennia and this sacred link disappears from world history in merely the last two hundred years?

Until the 1967 Referendum, the only references in the Constitution to the Indigenous peoples of this country were references of exclusion. Section 127 (repealed in 1967) said that “In reckoning the numbers of the people of the Commonwealth, or of a State or other part of the Commonwealth, aboriginal natives shall not be counted”. And s 51(xxvi) giving the Parliament legislative power to make laws with respect to “The people of any race… for whom it is deemed necessary to make special laws” was expressly qualified by the phrase “other than the aboriginal race in any State”. This phrase was deleted in 1967.

What is now proposed will recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples as “the First Peoples of Australia”. Thus, the proposed amendment will expressly acknowledge that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples lived in this land long before European settlement.

This recognition and acknowledgement is rooted in the common law of Australia rejecting the doctrine of terra nullius and holding, in Mabo (No 2) v Queensland (1992) 175 CLR 1, that this land was not a “legal desert” when European settlers came in 1778; this land was possessed by peoples who acknowledged and observed their traditional laws and traditional customs. Those laws and customs were not extinguished (and native title interests in land were not extinguished) by the British Crown’s assertion of sovereignty.

Settlers took possession of this land, and extended their occupation

of it, without the consent of the Indigenous inhabitants. As Brennan J rightly said in Mabo, “Their dispossession underwrote the development of the nation”. It is these legal and historical facts that underpin recognition of the First Peoples in our Constitution.

The Constitution is our basic law. It sets out the principles of how our federal system of government works. All Australians “own” the Constitution. If the proposed amendment is made, our Constitution will better reflect that ALL Australians own the Constitution and will better reflect the history of this land. And providing for the Voice looks to the future, not the past.

What then are the fears that have been raised?

Most are fears of unintended consequences. Many are expressed as fear of what the courts or lawyers will do. And as each fear has been shown to be false, a new and different fear has been expressed.

First it was said that the Voice would be a third chamber of the Parliament. It is not. It is a voice TO Parliament. It is not a voice IN Parliament. The text of the amendment shows that the proposition is false.

Then it was said that the Voice could veto government action. It cannot. Nothing in the text of the proposal supports the proposition. The powers of Parliament and the Executive are wholly unaffected by the proposed amendment. Saying the Voice could veto government action is false.

Next it was said, “we need more details”. Details of what?

Clause 3 of the proposal makes clear that it will be the Parliament that decides the details about how the Voice is set up and how its representations are dealt with by the Parliament and the Executive. And this is how it should be. The Constitution sets out principles, not machinery. Machinery can and should change as times change

and it is Parliament that will make and change that machinery, not the referendum. The call for “more details” is disingenuous and irrelevant. It is asking for details of what the Parliament will do in the future.

Then focus shifted to the phrase in clause 2—“representations … on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples”. How wide was the power? Would the Voice be able to make representations about defence policy or monetary policy and so on?

The High Court has often said that legislative powers are not to be given a meaning “narrowed by an apprehension of extreme examples and distorting possibilities”. Some, probably all, of the examples given in questions about the width of the power are extreme examples and distorting possibilities.

There are two practical answers to these particular appeals to fear. First, why would the Voice waste its political and social capital by making representations on matters of the kind described in these questions? The examples being given are cases that will not arise. Second, even if the Voice were to make representations on such matters, what would follow? The ordinary business of government will go on without interruption. Either what is said is persuasive or it is not. If it is persuasive, so be it; if it is not, it will be ignored.

Focussing on the outer limits of the power to make representations is nothing more than a baseless appeal to fear.

It is baseless because the unstated premise for arguments about the breadth of the power to make representations is (and always has been) that the Voice making representations will interfere with the ordinary and efficient working of government. The premise is false.

The power is a power to make representations. The word “representations” and the phrase

If the proposed amendment is made, our Constitution will better reflect that ALL Australians own the Constitution and will better reflect the history of this land.

“may make representations” are carefully chosen. They mean what they say. The proposed provisions impose no obligation on Parliament or the Executive to consult with the Voice. They impose no obligation on Parliament or the Executive to ask for representations. They impose no obligation to adopt or defer to the views expressed.

Could there be litigation about what the Parliament does or does not do in response to a representation by the Voice? No. The courts have always refused to enter into the intramural affairs of Parliament. It will be for Parliament (and ONLY Parliament) to decide how it will respond (if at all) to any representation.

What about representations to the Executive?

It has been said that we should foresee a decade of litigation. I do not agree.

If a court were to hold, that in the exercise of some statutory power, an officer of the Commonwealth (or other executive decision maker) was legally bound to take account of a representation by the Voice and that the decision maker had ignored the representation, a plaintiff with standing may be able to obtain judicial review of the decision. But three points have to be made.

First, Parliament may make laws with respect to matters relating to the Voice, including laws about what are the consequences of the Voice making a representation.

Second, who would have standing to seek judicial review?

Third, if a case for judicial review is made out, the best that the plaintiff can obtain would be an order quashing the decision and requiring the decisionmaker to decide again according to law. The court would not

exercise the power and the Executive, though bound to consider what the Voice had said would still have to reach its own conclusion.

But there is a more fundamental point which we must keep at the forefront of consideration. Any judicial review of Executive decisions would be no more than an ordinary application of the rule of law.

The rule of law defines the society in which we live. As a society we cannot be afraid of the rule of law. We must embrace it fully.

As lawyers we are bound to explain to any who ask us about these matters how the law operates. Adopt, if you will, what Brennan J said in Attorney-General (NSW) v Quin (1990) 170 CLR 1, 35-36: “The duty and jurisdiction of the court to review administrative action do not go beyond the declaration and enforcing of the law which determines the limits and governs the exercise of the repository’s power”.

How can we, why should we, fear the courts enforcing the law determining the limits and governing the exercise of public power?

What we cannot and must not do as lawyers is say, “The courts are coming! Be afraid. Be very afraid”. Yet that is all that those predicting years of litigation are saying.

Finally, it is necessary to deal with a point which only now begins to emerge—the argument of “equality”. It is said that the proposal will give “special rights to indigenous people”; it is “introducing racial distinctions in the Constitution”.

The notion of “equality” that is embraced by this argument is one of “identical” or “undifferentiated” treatment. That has never been the measure of equal treatment under the law. The law treats like cases alike but different cases differently.

The argument of “equality” says: Ignore history and the manifold disadvantages inflicted and entrenched by history and, regardless of disadvantage, treat everyone the same. Likewise, the argument appealing to “race” or “colour” treats 60,000 years or more of occupation of this land as irrelevant while silently invoking the horrors of twentieth century Europe.

No matter how the argument is expressed it is false. We cannot ignore history; we cannot ignore disadvantage or how and why it has come about. Treat everyone the same and you amplify and entrench disadvantage even further.

The proposed amendment takes no right or privilege away from any member of the Australian community. It does not alter in any way the powers of the Parliament or the Executive. It responds to the observed and undeniable fact that for more than 200 years settlers have been telling Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island peoples what is “best” for them. And that simply has not worked. We are still trying to close the gaps. We still see appalling rates of incarceration, family violence and dysfunction, and continuing health issues. We see time and time again what those who made the Uluru Statement said is “the torment of our powerlessness”.

This is why the Uluru Statement said that:

We seek constitutional reforms to empower our people and take a rightful place in our own country.

When we have power over our destiny our children will flourish. They will walk in two worlds and their culture will be a gift to their country.

We call for the establishment of a First Nations Voice enshrined in the Constitution.

We must answer that call. Rejecting it would inflict immeasurable damage on this body politic that would endure for generations.

EXPLORING THE VOICE

GAVIN SILBERT

Later this year, Australians will be asked to vote on a proposal to alter the Constitution to include a new chapter, Chapter IX, entitled "Recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples".

The proposal is to enshrine in the Constitution a body to be known as the Voice, which will have the power to make representations, on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, to those bodies in which the Constitution vests the legislative and executive powers of the Commonwealth: respectively, the Parliament (comprising the Governor-General as the Crown’s representative, the Senate and the House of Representatives) and the Executive Government (comprising the Governor-General, acting on the advice of the Federal Executive Council (the Cabinet)).

Before considering the merits of proposed Chapter IX, it is necessary to consider its apparent scope and implications.

On one view, the power of the Voice to make representations to the legislative and executive organs of the Commonwealth government might be one which is merely exercisable in the abstract, as in the case, for example, of an annual address to each of the Parliament and the Executive Government on how their conduct is or might be affecting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

However, that seems unlikely. It seems unlikely because such a construction would scarcely distinguish the proposed constitutional body from any other person in our society who is free to make representations to either the Parliament or the Executive Government, and so seek to influence the exercise by one or other of those bodies of their respective functions. It also seems unlikely because it would tend to suggest that the provisions of proposed section 129 are to be given little to no operative meaning, at least beyond that which is already implicit in our system of representative democracy, and so would offend that canon of construction which commands that the words employed in a statutory provision are presumed to have meaning and effect, at least where there is an alternative

construction available which would do just that.

The alternative construction is that, by necessary corollary of the power granted to the Voice to make representations in the terms expressed in proposed section 129, the Parliament and the Executive Government will be required, in the exercise of the powers vested in them pursuant to Chapters I and II of the Constitution, to consult with the Voice on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Further, for the provisions of section 129 to have any material effect, and because the Constitution establishes the Parliament and Executive Government for the express purpose of exercising the legislative and executive powers of the Commonwealth, it would appear that such consultation with the Voice must logically occur in advance of the exercise of legislative or executive power.

Moreover, for the same reasons, proposed section 129 must arguably carry with it an implied grant that the Parliament or the Executive Government, as the case may be, will supply such information and relevant materials to the Voice as to the proposed exercise of its powers as will permit the Voice to make informed representations to it on such matters.

Conceptually, therefore, the proposal is to condition the exercise of the Commonwealth’s legislative and executive powers, insofar as they concern matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, with an obligation to consult with and provide relevant materials to the Voice ahead of the exercise of those powers. In so doing, the proposal confers on that group rights that are not available to other Australians. As far as the Constitution

As far as the Constitution is concerned, that is a novel situation; no other body or individual commands such a right or power over the prospective exercise of such sovereign functions.

is concerned, that is a novel situation; no other body or individual commands such a right or power over the prospective exercise of such sovereign functions.

What then is the justification for affording this body with such a right or power? The answer to that question is supplied by the preamble to the proposed provision, in that it is to be conferred “[i]n recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First Peoples of Australia”. That is to say, the right of the Voice to be consulted on any exercise of legislative or executive power concerning matters relating to Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander peoples is to be conferred in recognition of such peoples’ status as the First Peoples of Australia.

The preamble, coupled with the use of the term “representations” in proposed section 129(2), thus gives rise to another implication, which is not necessarily apparent from the express terms of the provision. It is that the Voice must implicitly be constituted by persons appointed to represent the interests of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and, so it would seem, commanding the authority to represent such peoples. Accepting that to be so, the power to make laws with respect to (inter alia) the composition of the Voice under proposed section 129(3), which power itself is expressed as being subject to the Constitution, would appear at least to be limited in this way. Applying by analogy the situation concerning those other constitutional bodies with which the Voice would be concerned, the Parliament and the Executive Government, it is not a stretch to conceive of proposed Chapter IX as mandating that representatives of the Voice be democratically elected

by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples whom the Voice will represent.

Similarly, the power of the Parliament to make laws with respect to the Voice in section 129(3) could not extend to any act which is inconsistent with proposed sections 129(1) and (2), being the sections by which the Voice is to be established and its power to make representations so conferred. Thus, at the risk of stating the obvious, Parliament could not legislate to abolish the Voice or deny it the ability to make representations within the bounds of section 129(2) as ultimately construed.

What then of the role of courts, in which the judicial power of the Commonwealth is vested? They will have the role of determining, in a given controversy, the precise metes and bounds of proposed section 129, and the consequences of a failure by the Parliament or the Executive Government to adhere to that which is held to be guaranteed by proposed Chapter IX of the Constitution, or to the requirements of any legislation validly enacted by Parliament pursuant to the power in proposed section 129(3).

Inevitably, the courts will be called upon to determine the consequences of a failure or alleged failure by the Parliament or the Executive Government to consult with the Voice, or to heed its representations, either in a given case, or because the Parliament seeks to enact legislation purporting to deal with the consequences of such matters.

It is true that the text of proposed Chapter IX, insofar as it confers a power on the Voice to make “representations”, does not readily lend itself to a construction that a failure to heed such representations

It is undemocratic insofar as it imposes a check on the exercise of legislative and executive power which is reserved to a body representing only one group of electors.

would invalidate a particular exercise of legislative or executive power. However, on the construction, advanced above, that proposed Chapter IX conditions the proposed exercise of legislative or executive power, at least on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, with an obligation to consult the Voice ahead of the exercise of any such power, then it would appear to be seriously arguable that such a failure to consult might invalidate a given exercise of legislative or executive power.